Abstract

Objectives:

To describe acupuncture and chiropractic use among chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMP) patients at a health maintenance organization, and explore issues of benefit design and electronic medical record (EMR) capture.

Study Design:

Cross sectional survey

Methods:

Kaiser Permanente members meeting EMR diagnostic criteria for CMP were invited to participate. The survey included questions about self-identified presence of CMP, use of acupuncture and chiropractic care, use of ancillary self-care modalities, and communication with conventional medicine practitioners. Analysis of survey data was supplemented with retrospective review of EMR utilization data.

Results:

Of 6068 survey respondents, 32% reported acupuncture use, 47% reported chiropractic use, 21% used both, and 42% used neither. For 25% of patients using acupuncture and 43% of those using chiropractic, utilization was undetected by the EMR. Thirty-five percent of acupuncture users and 42% of chiropractic users did not discuss this care with their HMO clinicians. Among chiropractic users, those accessing care out of plan were older (p <.01), were more likely to use long term opioids (p=.03)), and had more pain diagnoses (p=.01) than those accessing care via clinician referral or self-referral. For acupuncture, those using the clinician referral mechanism exhibited these same characteristics.

Conclusions:

A majority of participants had used acupuncture, chiropractic care, or both. While benefit structure may materially influence utilization patterns, many patients with CMP use acupuncture and chiropractic care without regard to their insurance coverage. A substantial percentage of acupuncture and chiropractic use thus occurs beyond detection of EMR systems, and many patients do not report such care to their HMO clinicians.

Keywords: Acupuncture, Chiropractic, Electronic Medical Record, Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain

Precis:

Most chronic musculoskeletal pain patients use acupuncture or chiropractic care, however a substantial percentage of this utilization is not captured by the electronic medical record.

Background

Acupuncture and chiropractic care are popular among patients, especially those who suffer from chronic musculoskeletal pain.[1] Caring for this population has become an increasingly important and visible challenge for the health care system. Pharmaceuticals are commonly used for managing pain, yet the use of such agents on a chronic basis is of questionable efficacy, and can be associated with high costs and significant adverse effects.[2,3] For example, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can cause gastrointestinal toxicity or renal failure, while use of narcotic analgesics can be associated with somnolence, constipation, addiction, diversion of medications, and other problems.

Though many health insurers cover acupuncture and chiropractic care for pain management, such coverage is often limited in scope, and integration of acupuncture and chiropractic care with conventional practice may be piecemeal, or non-existent.[4–7,7–10] Health insurance providers may allow patients to self-refer for acupuncture and chiropractic care, or may require patients to first obtain referral from a primary care physician. Which mechanism may be optimal in terms of patient satisfaction, inter-clinician communication, and clinical outcomes, has not been explored.

Ultimately, better integration may require a more robust evidence base toward identifying the optimal clinical context for acupuncture and chiropractic use. In developing such an evidence base, attention is turning to analyses of data from clinical and administrative electronic medical records to enhance both conventional and innovative study designs.[11] Electronic medical records potentially contain useful information on large numbers of patients that is already being collected in the context of routine care delivery. It is unclear, however, to what extent such electronic databases contain information about acupuncture and chiropractic utilization that is accurate or complete.

We recently surveyed chronic musculoskeletal pain patients in a large Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) to ascertain to what extent electronic medical records are capturing acupuncture and chiropractic utilization among its membership. In particular, we address the following questions:

Description of acupuncture and chiropractic use: What is the prevalence of self-reported acupuncture and chiropractic use among chronic musculoskeletal patients at the HMO? Which types of patients use acupuncture? Chiropractic care? What are the perceived barriers to such use? How often do acupuncture and chiropractic users communicate such use to their HMO clinicians?

Medical record capture: To what extent is acupuncture and chiropractic utilization captured by the HMO’s electronic medical record (EMR)?

Utilization and benefit coverage: How if at all do patients who access acupuncture and chiropractic through various mechanisms differ from one another?

Methods

Setting and coverage policies

Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW) is a group model HMO serving approximately 500,000 members in Oregon and Washington. KPNW members can be referred by an HMO clinician for acupuncture and chiropractic care based upon locally developed evidence-based referral guidelines.[12,13] In brief, for chiropractic care, referrals are approved for acute non-radicular back or neck pain. Acupuncture referrals can be approved for most chronic pain conditions. Acupuncture and chiropractic care are provided by clinicians affiliated with Complementary Health Plans (CHP), a network of credentialed acupuncturists and chiropractors with which KPNW contracts. CHP acupuncturists and chiropractors bill KPNW directly for services provided under this mechanism. We describe this mechanism for accessing care as “clinician referral.”

In addition, many KPNW members or their employers have purchased a self-referral insurance rider which allows patients to directly access a CHP acupuncturist or chiropractor for any indication, up to annual utilization limits. Payment for these benefits is made on a capitated basis from KPNW to CHP, and acupuncture and chiropractic clinicians thus bill CHP for office visits and services provided. Approximately a third of KPNW patients reside in Southwest Washington, where some coverage of acupuncture and chiropractic services is mandated by the state, while the remainder live in Oregon where there is no such mandate. All KPNW Washington members have a self-referral benefit for chiropractic, paid for on a capitated basis. We describe this mechanism for accessing care as“self-referral.”

KPNW infrastructure includes a comprehensive EMR used for all patient encounters. This EMR allows for tracking of patient demographics, diagnoses, referrals, billing, and utilization. We are thus able to capture acupuncture and chiropractic services billed and received through the “clinician referral” mechanism electronically with the KPNW EMR. For this analysis we accessed EMR data for the years 2009–2011.

CHP also maintains an electronic database tracking visits, diagnoses, and procedures for “self-referral” patients. Electronic data from the CHP database were available for this analysis for the year 2011.

Participants

We developed a comprehensive ICD9 code list to identify patients whose pattern of clinical diagnoses in their EMR was consistent with chronic musculoskeletal pain[14]. The sample was operationally defined as including KPNW members at least 18 years old at the time of their first medical visit with a pain-related diagnoses, with ≥ 3 outpatient (emergency department, ambulatory visit, email or telephone) encounters evident in the EMR spanning at least 180 days but no more than 18 months. We required appropriate diagnostic codes indicating:

-

■

Three occurrences of musculoskeletal pain diagnoses, OR

-

■

First diagnosis of musculoskeletal pain and two subsequent diagnoses of nonspecific chronic pain, OR

-

■

First diagnosis of musculoskeletal pain with one additional musculoskeletal pain diagnosis and one nonspecific chronic pain

These eligibility criteria are described in more detail elsewhere[14].

Survey Methods

Patients meeting the criteria for chronic musculoskeletal pain described above between 2009 and 2011 were invited to complete a survey online or by mail. The invitation emphasized a broad interest in identifying treatment and self-care activities to manage persistent pain, framed as “we want to know what works for you.” The survey included questions related to self-identified presence of chronic pain, self reported use of acupuncture and chiropractic care, use of ancillary self-care modalities (yoga, tai chi/qigong, supplements, massage, meditation, physical activity, diet, other), and communication with conventional medicine practitioners about acupuncture and chiropractic use. Where patients indicated, through survey response, that they had utilized acupuncture or chiropractic care without using their HMO insurance, we designated such access to care as “out of plan.”

Prior to survey implementation, we pretested the survey with five patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain identified from participants in a psycho-educational program for pain patients offered through the KPNW pain clinic. From this group, we selected for interview patients who, upon completing the draft survey, either had self-identified using out-of-plan CAM services or whose response patterns evidenced confusion regarding survey questions. The goal of the interviews was to obtain patient feedback regarding important points missed and to tailor wording to enhance acceptability and avoid ambiguity.

Members meeting chronic musculoskeletal pain criteria were contacted by mail with a post card inviting them to log on to a web site to complete the survey online. The initial online response rate to the post card was 4% (N=1731). After 2 weeks, those who did not respond were contacted by email (N=4885), or were sent a paper copy of the survey by U.S. mail (N=34,211). Finally, ten percent of non-responders were called and invited to complete the survey by phone, selected based upon the date they had been mailed the survey. Ultimately, approximately 5% of the surveys were completed by phone while 18% were completed online, and 77% by mailed paper survey response.

Analysis

Chi-Square tests were used for comparisons on categorical variables. ANOVA was used for continuous variables. As our purpose was to generate, rather than test, hypotheses, we did not correct for multiple comparisons.

Results

Description of acupuncture and chiropractic use

Of 49,426 patients invited to participate, 8264 (16.7%) participants responded. Of these, 6068 (73.4%) self reported chronic musculoskeletal pain and are the focus of this manuscript. These 6068 participants were predominantly Caucasian (94%) and female (71%), with a mean age of 61 (SD 13). Thirty-two percent reported acupuncture use for pain, while 47% reported chiropractic use for pain. The number reporting both acupuncture and chiropractic use was 21%. Forty two percent of respondents used neither acupuncture nor chiropractic care.

The four usage groups differed significantly in age and gender (Table 1). In addition, the percentage of participants self-reporting back pain, neck pain, muscle pain, headache, fibromyalgia, or abdominal/pelvic pain was highest in the group using both acupuncture and chiropractic.

Table 1.

Participant demographics and reported pain diagnoses

| Total sample |

Respondents | Used Chiro Only |

Used Acu Only |

Used both | No Acu/chiro use |

p-value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=8264 | N=6068 | n=1579 | n=677 | n=1278 | n=2534 | N=6068 | |

| Female (%) | 69 | 71 | 68 | 75 | 76 | 68 | <.0001 |

| Age (mean/sd) | 61 ± 14 | 61 ± 13 | 59 ± 13 | 61 ± 14 | 58 ± 13 | 64 ± 13 | <.0001 |

| Caucasian (%) | 93 | 94 | 95 | 94 | 94 | 94 | 0.6374 |

| Self-reported diagnoses from survey (%) | |||||||

| Back | 64 | 75 | 62 | 76 | 51 | <.0001 | |

| Joint pain | 57 | 57 | 56 | 57 | 57 | 0.9719 | |

| Arthritis | 54 | 54 | 56 | 49 | 56 | 0.0018 | |

| Extremity | 56 | 55 | 57 | 56 | 56 | 0.6739 | |

| Neck | 38 | 47 | 36 | 53 | 26 | <.0001 | |

| Muscle | 31 | 32 | 31 | 41 | 25 | <.0001 | |

| Headache | 23 | 26 | 22 | 33 | 15 | <.0001 | |

| Fibromyalgia | 15 | 16 | 17 | 22 | 11 | <.0001 | |

| Abdomen/pelvis | 10 | 12 | 9 | 13 | 9 | <.0001 | |

| Other | 10 | 9 | 13 | 11 | 9 | 0.0190 | |

two-tailed p-value for comparing four usage groups based on 1-way ANOVA (continuous data) or Pearson chi-square test (proportions)

Barriers

Among the 4113 individuals who reported never having used acupuncture services, the most commonly cited reasons were: never considered doing so, cost, and didn’t know a reputable provider (Table 2). Among the 3211 individuals who reported never having used chiropractic services, the most commonly cited reasons were: never considered, didn’t think it would help, and cost.

Table 2.

Reasons for not seeking acupuncture or chiropractic services.

| Never used acupuncture (n=4113) |

Never used chiropractic (n=3211) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prev (%) | 95% CI | Prev (%) | 95% CI | |

| Cost | 28 | 26.3, 29.0 | 17 | 15.3, 17.9 |

| Don’t know reputable provider | 18 | 17.1, 19.4 | 10 | 8.6, 10.6 |

| Discomfort with or fear of the procedure | 8 | 7.4, 9.1 | 15 | 13.9, 16.4 |

| Safety concerns | 5 | 4.2, 5.5 | 14 | 12.7, 15.1 |

| Don’t think it will help | 13 | 11.7, 13.8 | 23 | 21.3, 24.2 |

| Never considered | 45 | 43.3, 46.4 | 31 | 29.1, 32.3 |

Communication

Of those using only acupuncture, 35% did not discuss their acupuncture use with their primary care provider, while 42% of those using only chiropractic services did not discuss their chiropractic use (Table 3). However, most of these individuals indicated that they would do so if asked about such use.

Table 3.

Patterns of reporting acupuncture and chiropractic to provider

| N=2200 | Used only Acu (n=668)1 |

Used only Chiro (n=1532)1 |

|---|---|---|

| Prev (%) | Prev (%) | |

| No, I would never do this | 1 | 2 |

| No, but would tell if asked | 34 | 40 |

| Shared some info | 27 | 25 |

| Shared everything | 30 | 26 |

| Other | 7 | 7 |

Excludes those missing responses to the question (Acu only, n=9; Chiro only, n=47)

Two-tailed p-value = 0.048 based on Pearson Chi-square

Medical record capture

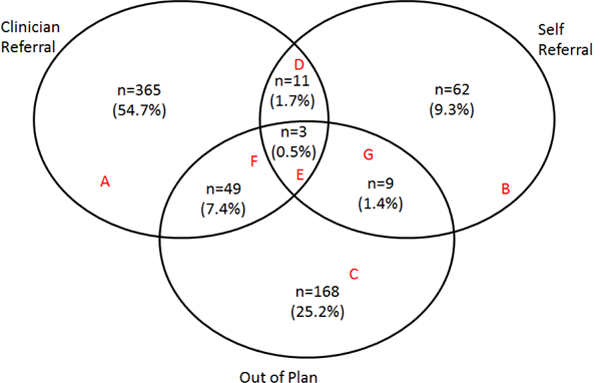

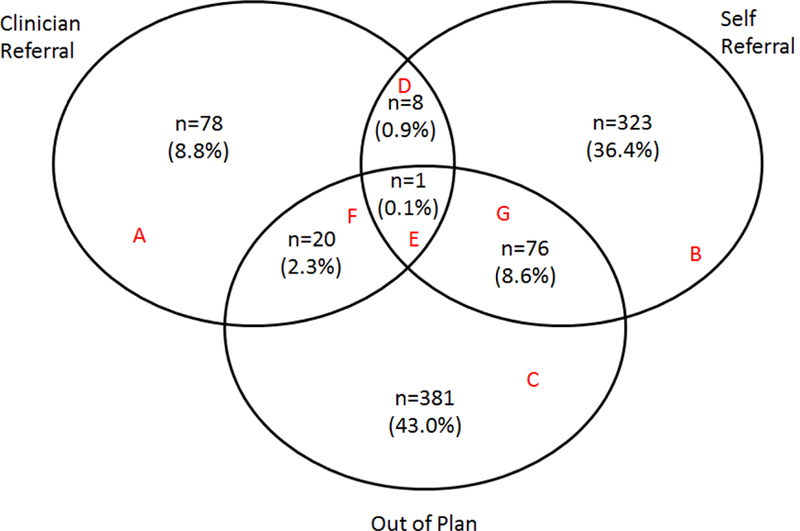

Figures 1 and 2 describe the distribution of utilization for acupuncture and chiropractic across different referral mechanisms for the year 2011.

Figure 1.

Acupuncture Use in 2011(N=667): Those who resoponded to the survey, met our definition for chronic musculoskeletal pain at the time of the survey, and self reported chronic pain on the survey

Figure 2.

Chiropractic Use in 2011(N=887): Those who responed to the survey, met our definition for chronic musculoskeletal pain at the time of the survey, and self reported chronic pain on the survey

For acupuncture, data were captured for 667 patients. Of these, 168 (25%) utilized acupuncture entirely out of plan, and were not captured by the EMR. Overall, 229 (34%) users of acupuncture utilized at least some acupuncture out of plan. Over half (55%) of patients using acupuncture in 2011 did so entirely based upon clinician referral, while 9% of patients used acupuncture entirely based upon a self referral benefit. Of 428 patients who used a clinician referral, 52 (12%) supplemented their health plan benefit with additional out of plan utilization.

For chiropractic, data were captured for 887 patients. Of these, 381 (43%) utilized chiropractic entirely out of plan, and thus not captured by the EMR. Overall, 478 (54%) of participants used at least some chiropractic out of plan. 323 patients (36%) used chiropractic based solely upon self referral benefit coverage, while only 78 patients (9%) used chiropractic based solely upon clinician referral. Of 408 patients who used chiropractic in 2011 using a self referral benefit, 77 (19%) supplemented their self referral health plan benefit with additional out of plan utilization.

Thus for acupuncture, most utilization was based upon clinician referral. In contrast, for chiropractic, relatively little utilization was based upon clinician referral, with the great majority of patients accessing care out of plan, through self-referral, or both.

Utilization and benefit coverage

For this set of analyses, data are included for the subset of patients indicating 2011 utilization. “Out of plan only “ describes participants in Area C of the Venn Diagrams(Figures 1 and 2). “Clinician referral” describes participants in areas A + F of the Venn Diagrams; those who used the clinician referral mechanism for at least some of their care. “Self-referral” describes participants in areas B + G of the Venn Diagrams; those who used the self -referral mechanism for at least some of their care. The small number of patients in areas D and E were dropped.

There were no differences among the three groups (out of plan only, clinician referral, self-referral) with respect to gender, ethnicity, or smoking status. For chiropractic, there was a tendency for those accessing care out of plan to be older (mean 58 years SD 13, p <.01), to use long term opioids (16%, p=.03)), and to have more pain diagnoses (mean 4.2, SD 2.1, p=.01). For acupuncture, there was a tendency for those using clinician referral mechanism to exhibit these same characteristics (mean age 59 SD 13, p<.01; long term opioid use 21%, p=.02; mean number of pain diagnoses 4.0, SD 2.1, p=.01). Acupuncture patients receiving clinician referral care were also less educated compared to those using self-referral or out of plan care (high school/GED or less 20%, some college 44%, college graduate or more 36%, p<.01).

For chiropractic users, the most commonly used additional CAM modality was massage (55% for out of plan only, 57 % for clinician referral, 53% for self-referral). However there were no significant differences the among the 3 utilization groups with respect to self-reported use of any of the additional CAM modalities, including massage, yoga, tai chi/qigong, supplements, massage, meditation, physical activity, diet, or other. For acupuncture users, the most commonly used additional CAM modality was also massage (52% for out of plan only, 46 % for clinician referral, 56% for self-referral). Acupuncture users accessing care through self-referral were more likely than clinician referral or out of plan users to report use of dietary (23%, p =.02) or other (24%, p=.03) modalities.

Participants accessing acupuncture via clinician referral were significantly more likely than those accessing acupuncture via self-referral or out of plan only to self-report pain in the back (73%, p=.01), muscles (41%, p=.03), or pain due to arthritis (54%, p<.01). For chiropractic care, those obtaining care out of plan only were significantly more likely to report extremity pain (59%, p=.02).

Discussion

The use of acupuncture and chiropractic care among HMO chronic pain patients responding to our survey was substantial. Those using neither acupuncture nor chiropractic care (42%) were in the minority. The data also suggest that a substantial percentage of acupuncture and chiropractic use in not documented by the EMR, and/or not reported by patients to their HMO clinicians.

While investigators may use clinical and administrative databases to enhance study design, results suggest that EMR data fail to detect a substantial percentage of acupuncture and chiropractic utilization, even in an integrated delivery system with allowable referrals to acupuncture and chiropractic care as well as a state of the art EMR. Any EMR based analysis of acupuncture and chiropractic use would require additional survey or other data collection to capture the full spectrum of care.

Clinicians should assume that a substantial percentage of their patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain are receiving acupuncture and chiropractic care. For both acupuncture and chiropractic users, the most commonly endorsed answer to the question, “Did you share information about acupuncture/chiropractic use w/ your HMO clinician?” was “No, but would tell if asked.” The finding serves to emphasize the importance of clinicians’ raising this topic in routine encounters with chronic pain patients. Engaging the patient in a discussion about acupuncture and chiropractic use can provide information for optimizing care. Such discussions can reinforce a patient’s self-management efforts and potentially provide insight as to the types of patients who may be, or should be, using acupuncture and/or chiropractic services. Clinicians should also consider direct communication with acupuncturists and chiropractors about patients they are co-managing. This may allow better coordination of care and potentially improve outcomes.

Our data suggest that, to a substantial extent, insurance benefits influence who uses acupuncture and chiropractic care, and under what circumstances. For acupuncture, the majority of utilization was based upon clinician referral. In contrast, for chiropractic care, relatively little utilization was based upon clinician referral, with the great majority of patients accessing care out of plan (with no insurance coverage), through self-referral, or both. Chiropractic care may be commonly used for chronic pain by patients, but at KPNW medical necessity criteria limit clinician referrals for chiropractic care to acute pain. In addition, Washington patients all have a self-referral insurance rider for chiropractic care, but not for acupuncture. This renders it easier for Washington members to access chiropractic, in contrast to acupuncture, by self-referral. At the same time, patients seeking chiropractic care may be dissuaded from using HMO benefits when the per-visit fee for obtaining chiropractic out of plan is only marginally higher than their HMO co-pay.

For chiropractic, there is a tendency for “out of plan only” users to be older, to use long term opioids, and to have more pain diagnoses. For acupuncture, there is a tendency for those using the clinician referral mechanism to exhibit these same characteristics. This is consistent with the acupuncture referral guidelines, which allow for care only in the setting of chronic, as opposed to acute, pain. Chiropractic benefits for self-referral are limited in dollar amount allowed, and for clinician referral are constrained by referral guidelines allowing only use for acute pain. Those who desire ongoing maintenance treatments will of necessity go out of plan.

The substantial percentage of participants indicating out of plan use suggests that many chronic pain patients are determined to use acupuncture and chiropractic care, regardless of their insurance coverage. In this context, and in the face of the high prevalence of acupuncture and chiropractic use, policy makers may need to consider better ways of covering and integrating acupuncture and chiropractic care into conventional delivery systems.[15,16] Many chronic pain patients may consider acupuncture and chiropractic coverage important when selecting a health insurance plan. In addition, better acupuncture and chiropractic integration could offer potential opportunities for improved management algorithms and more efficient utilization of resources.[17,18] The potential for acupuncture and chiropractic care to serve as non-invasive alternatives to pharmacologic and procedural interventions, or as tools to facilitate the reduction of chronic pharmacotherapy, would seem to warrant further investigation. [19,20]

Study strengths include a large sample size, as well as the availability of a comprehensive EMR. There exist multiple pathways to acupuncture and chiropractic care within the HMO, which we were able to electronically track and compare. We in addition were able to supplement EMR data with survey data to gain a more complete picture of overall acupuncture and chiropractic utilization. Study limitations include a relatively low survey response rate. We did not attempt to contact non-responders to determine possible reasons for this. Additionally, survey responders may not be well representative of the broader group of patients who suffer from chronic pain. Comparing survey responders who self-endorsed chronic pain versus non responders, using EMR demographic and diagnostic data (6 comparisons), we found that responders were more likely to be female or Caucasian and were less likely to smoke, and more likely to have had an acupuncture referral (p for all <.01). It is likewise unclear to what extent any findings or conclusions may be applicable to other health care venues beyond an HMO setting, or beyond KPNW.

Conclusions

In our analyses, a majority of HMO participants with chronic musculoskeletal pain have used acupuncture, chiropractic care, or both. While benefit structure may materially influence utilization patterns, many patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain use acupuncture and chiropractic care without regard to their insurance coverage. A substantial percentage of acupuncture and chiropractic use thus occurs beyond detection of EMR systems, and many patients do not report their acupuncture and chiropractic utilization to their HMO clinicians.

Take away points:

A majority of HMO participants with chronic musculoskeletal pain had used acupuncture, chiropractic care, or both.

While benefit structure may materially influence utilization patterns, many patients with chronic pain use acupuncture and chiropractic care without regard to their insurance coverage.

A substantial percentage of acupuncture and chiropractic use occurs beyond detection of EMR systems, and many patients do not report their acupuncture and chiropractic utilization to their HMO clinicians.

Better acupuncture and chiropractic integration could offer potential opportunities for improved management algorithms and more efficient utilization of resources.

Acknowledgments

The project was supported by a grant (R01 AT005896) from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

This is the pre-publication version of a manuscript that has been accepted for publication in The American Journal of Managed Care® (AJMC®). This version does not include post-acceptance editing and formatting. The editors and publisher of AJMC® are not responsible for the content or presentation of the prepublication version of the manuscript or any version that a third party derives from it. Readers who wish to access the definitive published version of this manuscript and any ancillary material related to it (eg, correspondence, corrections, editorials, etc) should go to www.ajmc.com or to the print issue in which the article appears. Those who cite this manuscript should cite the published version, as it is the official version of record.

Contributor Information

Charles Elder, Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research.

Lynn DeBar, Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research.

Cheryl Ritenbaugh, University of Arizona.

William Vollmer, Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research.

Richard A. Deyo, Oregon Health and Science University.

John Dickerson, Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research.

Lindsay Kindler, Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research.

Reference List

- 1.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL: Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report 2008, 1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beebe FA, Barkin RL, Barkin S: A clinical and pharmacologic review of skeletal muscle relaxants for musculoskeletal conditions. American Journal of Therapeutics 12(2):151–71, 2005, -April. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Von Korff M, Kolodny A, Deyo RA, Chou R: Long-term opioid therapy reconsidered. Annals of Internal Medicine 2011, 155: 325–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell IR, Caspi O, Schwartz GE, Grant KL, Gaudet TW, Rychener D et al. : Integrative medicine and systemic outcomes research: issues in the emergence of a new model for primary health care. Arch Intern Med 2002, 162: 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nahin RL, Pontzer CH, Chesney MA: Racing toward the integration of complementary and alternative medicine: a marathon or a sprint? Health Aff (Millwood ) 2005, 24: 991–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaptchuk TJ, Miller FG: Viewpoint: what is the best and most ethical model for the relationship between mainstream and alternative medicine: opposition, integration, or pluralism? Academic Medicine 2005, 80: 286–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leckridge B: The future of complementary and alternative medicine--models of integration. [Review] [8 refs]. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine 2004, 10: 413–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCaffrey AM, Pugh GF, O’Connor BB: Understanding patient preference for integrative medical care: results from patient focus groups. J Gen Intern Med 2007, 22: 1500–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caspi O, Sechrest L, Pitluk HC, Marshall CL, Bell IR, Nichter M: On the definition of complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine: societal mega-stereotypes vs. the patients’ perspectives. [Review] [48 refs] Alternative Therapies in Health & Medicine, 2003. 9: 58–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ben-Arye E, Frenkel M, Klein A, Scharf M: Attitudes toward integration of complementary and alternative medicine in primary care: perspectives of patients, physicians and complementary practitioners Patient Educ Couns 2008, 70: 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Witt CM, Huang WJ, Lao L, Bm B: Which research is needed to support clinical decision-making on integrative medicine?- Can comparative effectiveness research close the gap?. [Review]. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine 2012, 18: 723–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, Lewith G, MacPherson H, Foster NE et al. : Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis. Archives of Internal Medicine 2012, 172: 1444–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bronfort G, Haas M, Evans R, Leininger B, Triano J: Effectiveness of Manual Therapies: the UK Evidence Report. Chiropractic and Osteopathy 2010, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeBar LL, Elder C, Ritenbaugh C, Aickin M, Deyo R, Meenan R et al. : Acupuncture and chiropractic care for chronic pain in an integrated health plan: a mixed methods study. BMC Complementary & Alternative Medicine 2011, 11: 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Templeman K, Robinson A: Integrative medicine models in contemporary primary health care. [Review]. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 2011, 19: 84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldman E: Practical strategies for implementing integrative medicine in a primary care setting. Journal of Medical Practice Management 2008, 24: 97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teets RY, Dahmer S, Scott E: Integrative medicine approach to chronic pain. [Review] [88 refs]. Primary Care; Clinics in Office Practice 2010, 37: 407–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kligler B, Homel P, Harrison LB, Levenson HD, Kenney JB, Merrell W: Cost savings in inpatient oncology through an integrative medicine approach. American Journal of Managed Care 2011, 17: 779–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elder C, Ritenbaugh C, Aickin M, Hammerschlag R, Dworkin S, Mist S et al. : Reductions in pain medication use associated with traditional Chinese medicine for chronic pain. Permanente Journal 2012, 16: 18–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sundberg T, Petzold M, Wandell P, Ryden A, Falkenberg T: Exploring integrative medicine for back and neck pain - a pragmatic randomised clinical pilot trial. BMC Complementary & Alternative Medicine 2009, 9: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]