SUMMARY

Type III CRISPR-Cas systems provide robust immunity against foreign RNA/DNA by sequence-specific RNase and target RNA-activated sequence-nonspecific DNase/RNase activities. We report on cryo-EM structures of Thermococcus onnurineus CsmcrRNA binary, CsmcrRNA-target RNA and CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag ternary complexes in the 3.1 Å range. The topological features of the crRNA 5’-repeat tag explains the 5’-ruler mechanism for defining target cleavage sites, with accessibility of positions −2 to −5 within the 5’-repeat serving as sensors for avoidance of autoimmunity. The Csm3 thumb elements introduce periodic kinks in the crRNA-target RNA duplex, facilitating cleavage of the target RNA with 6-nt periodicity. Key Glu residues within a loop segment of CsmcrRNA adopt a proposed autoinhibitory conformation, suggestive of DNase activity regulation. These structural findings complemented by mutational studies of key intermolecular contacts provide insights into CsmcrRNA complex assembly, mechanisms underlying RNA targeting and site-specific periodic cleavage, regulation of DNase cleavage activity and autoimmunity suppression.

Graphical Abstract

In Brief

cryo-EM structures of type III-A CsmcrRNA in the absence/presence of target RNA define the role of the 5’-repeat tag and kinks in positioning of 6-nt periodic RNA cleavage sites, the contribution of a Glu-rich loop to DNase activity regulation and pairing capacity at −2 to −5 within 5’-repeat dictating autoimmunity.

INTRODUCTION

CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats)-Cas (CRISPR-associated genes) systems are RNA-based adaptive immune systems employed by prokaryotes against invading nucleic acids from bacteriophages and plasmids (Barrangou et al., 2007; Marraffini, 2015; Marraffini and Sontheimer, 2008; van der Oost et al., 2014). This immunity is acquired by integrating short spacer sequences derived from foreign genomes into the host CRISPR locus. The CRISPR loci are transcribed and processed into short CRISPR-derived RNAs (crRNAs) that contain a spacer typically flanked by parts of the repeats. The precursor crRNAs are next processed into mature crRNAs, which assemble with Cas proteins to form crRNA-effector complexes responsible for the cleavage-mediated degradation of invading genetic elements. Based on the composition of crRNA-effector complexes, they are broadly divided into two classes (Koonin et al., 2017; Makarova et al., 2015; Makarova et al., 2017a, b), with class 1 systems (including types I, III and IV) composed of multi-subunit effector complexes, whereas Class 2 systems (including type II, V and VI) comprise single-subunit protein effectors.

One type of Class 1 CRISPR-Cas system, known as type III CRIPSPR-Cas locus (Makarova et al., 2015; Pyenson and Marraffini, 2017; Tamulaitis et al., 2017), is the most diverse and might be central to all CRISPR-Cas systems since the Cas10-like signature protein of type III systems is believed to be the ancestral Cas effector module (Mohanraju et al., 2016). The type III family was divided into III-A (Csm complex including subunits Cas10, Csm2 to Csm5 and crRNA) and III-B (Cmr complex including subunits Cas10, Cmr2 to Cmr6 and crRNA) (Makarova et al., 2015).

Differing from type I effector complexes that target double-stranded DNA and recruit a trans-acting Cas3 nuclease-helicase to degrade both strands of the double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) (Sinkunas et al., 2011; Westra et al., 2012), type III complexes target both RNA and single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) based on its own intrinsic and distinct RNA and DNA nuclease activities (Samai et al., 2015; Tamulaitis et al., 2017). Type III complexes rely on either the Csm (type III-A) or Cmr (type III-B) effector complexes to cleave target RNA that is complementary to crRNA into 6-nt nucleotide lengths using the catalytic activity of their Csm3/Cmr4 domains. In addition, target RNA binding allows the effector complex to cleave single-stranded DNA in a transcriptional-coupled process using the nuclease activity of the HD module of their Csm1/Cmr2 domains (Elmore et al., 2016; Estrella et al., 2016; Kazlauskiene et al., 2016; Samai et al., 2015).

Further, in contrast to type I CRISPR-Cas systems that rely on short (2–4 nt) protospacer-adjacent motifs (PAMs) to distinguish self from non-self (Mojica et al., 2009; Westra et al., 2013), type III systems were proposed to utilize base-pairing potential between elements of the 5’-repeat sequence (8-nt nucleotides) flanking the RNA spacer of crRNA (also called 5’-repeat tag) and 3’-flanking sequences of target RNA (here sequence complementary to 5’-repeat tag is called anti-tag) for discriminating self from non-self (Kazlauskiene et al., 2016; Marraffini and Sontheimer, 2010; Pyenson et al., 2017).

However, despite these differences between type I and type III systems, the majority of available high-resolution structural information on Class 1 effector complexes has been restricted to type I systems (Chowdhury et al., 2017; Guo et al., 2017; Hayes et al., 2016; Jackson et al., 2014; Mulepati et al., 2014; Xiao et al., 2018; Xiao et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2014). The high-resolution structural view for type III systems is limited to the 2.1 Å crystal structure of the Cmr1-deficient chimeric type III-B CmrcrRNA bound to ssDNA (Osawa et al., 2015). Cryo-EM studies have also been reported on CmrcrRNA complexes in the absence and presence of target RNA at 4.1 and 4.4 Å resolution respectively (Taylor et al., 2015). By contrast, cryo-EM studies on type III-A Csm complexes to date are limited to ~20 Å negative-stain EM structures (Park et al., 2017; Rouillon et al., 2013; Staals et al., 2014). Hence, a high-resolution understanding for Csm complex assembly, RNA and DNA targeting and cleavage is still lacking at this time.

Here, we have determined cryo-EM structures of hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus onnurineus CsmcrRNA binary, as well as CsmcrRNA-target RNA (without anti-tag sequence), and CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag (with anti-tag sequence) ternary complexes at an average resolution of 3.0 Å, 3.1 Å and 3.1 Å, respectively. The structures explain how the five proteins of the Csm complex (Cas10-henceforth labeled Csm1, together with Csm2 to Csm5) are assembled with crRNA into an intertwined helical topology, provides insights into how the topology of the 5’-repeat tag is important for avoidance of autoimmunity, and how an autoinhibitory loop controls target RNA-mediated DNase cleavage activity by the HD domain, thereby providing insights into RNA targeting and RNA/DNA cleaving mechanisms.

RESULTS

Assembly of CsmcrRNA Complexes

The T. onnurineus Csm1-Csm4 subcomplex, Csm2, Csm3 and Csm5 in the Csm CRISPR-Cas locus (Figure 1A) were respectively expressed in E. coli and assembled with crRNA in vitro at a molar ratio of 1: 1.5: 4: 1.5: 1.3 based on a previous protocol (Park et al., 2017). Formation of a homogeneous complex containing all bound Csm subunits as monitored by gel filtration only occurred in the presence of crRNA, with an additional peak observed for excess Csm2, Csm3 and Csm5 subunits (Figures S1A, S1B and S1C). The CsmcrRNA-target RNA and CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag ternary complexes were generated by adding a target RNA without (Figure S1D) and with anti-tag sequence (Figure S1E) following the same procedure as for the binary complex. Given that previously reported Csm complexes from other species contain more copies of Csm2 and Csm3 (Rouillon et al., 2013; Staals et al., 2014), we further assembled the complex by mixing Csm1-Csm4 subcomplex, Csm2, Csm3 and Csm5 at a ratio of 1: 5: 6: 1.5: 1.3 (Figure S2B). The gel filtration profile, SDS-PAGE analysis and RNA cleavage pattern (Figures S2C and S2D) showed that the stoichiometry of the complex was the same in both reconstitutions. Based on the size of the cleavage bands, we positioned the 6-nt cleavage intervals at four positions as shown schematically in Figure S2E. The ssDNA cleavage assays also showed that both reconstitutions are functional with comparable activities (Figure S2F).

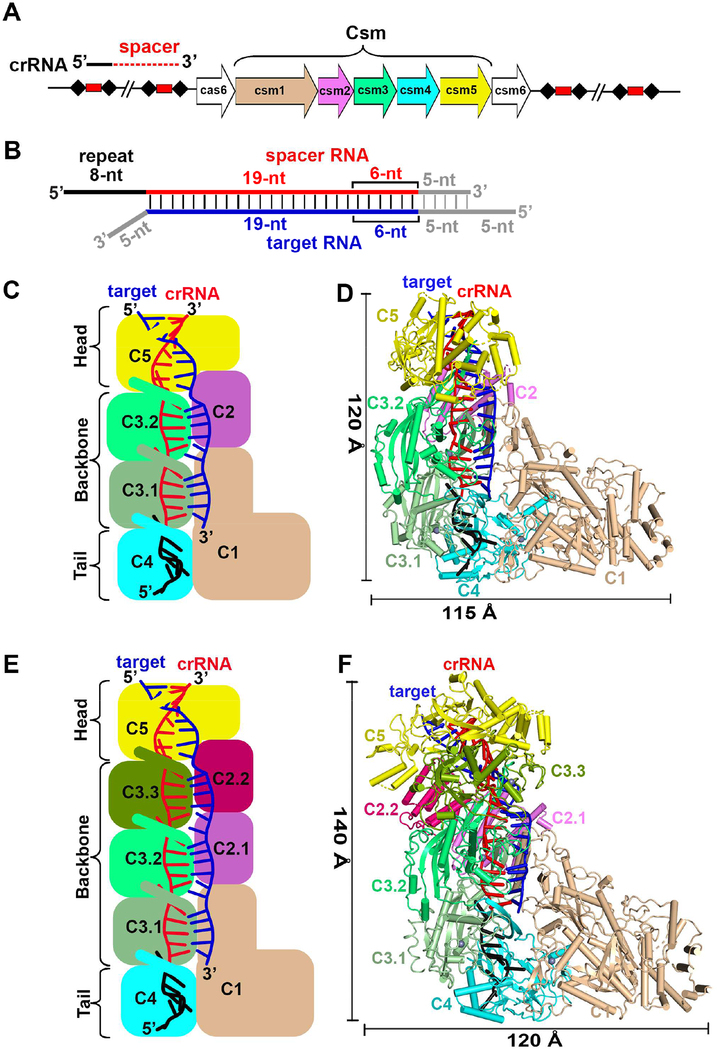

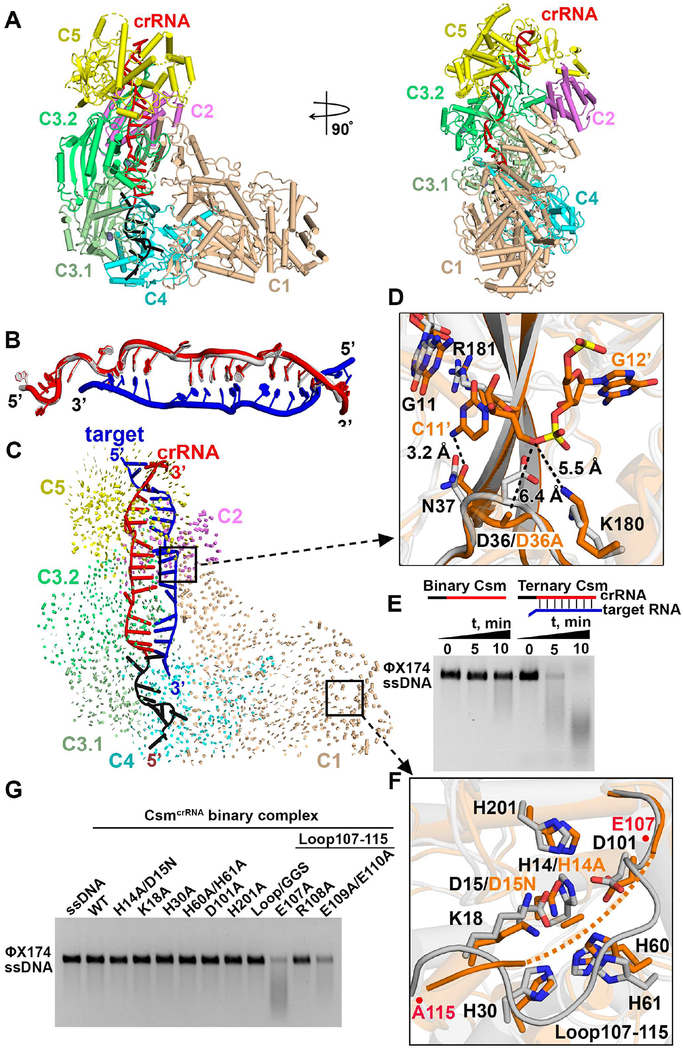

Figure 1. Structure of CsmcrRNA-Target RNA Ternary Complex.

(A) The type III-A CRISPR-mediated immune system in T. onnurineus consists of seven cas genes flanked by two CRISPR loci. The CRISPR loci are composed of nucleotide repeats (black diamonds) separated by nucleotide phage- or plasmid-derived spacer sequences (red cylinders).

(B) Schematic representation of pairing between crRNA and target RNA. Segments that can be traced in the 1122334151 complex are in color, while disordered segments are in grey. Complex with stoichiometry 1122334151 covers an extra 6-nt duplex than its 1121324151 counterpart.

(C and D) Schematic (C) and ribbon (D) representation of 3.1 Å cryo-EM structure of CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complex composed of Csm subunits with stoichiometry 1121324151.

(E and F) Schematic (E) and ribbon (F) presentation of 3.6 Å cryo-EM structure of CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complex composed of Csm subunits with stoichiometry 1122334151.

See also Figures S1–S4 and Table 1.

Topology of CsmcrRNA-Target RNA Ternary Complexes

Our cryo-EM studies on CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complexes containing a 38-nt crRNA and 40-nt target RNA were undertaken on a D36A mutant in the catalytic Csm3 subunit so as to prevent target RNA cleavage (Park et al., 2017). Structural analysis (Figure S3) resulted in classification into two complexes, one with the stoichiometry 1121324151 (one Csm2 and two Csm3) at 3.1 Å (Figure 1C, D) and a second with the stoichiometry 1122334151 (two Csm2 and three Csm3) at 3.6 Å (Figure 1E, F).

We focus first on the presentation of the higher resolution 3.1 Å structure of the Csm ternary complex composed of Csm subunits with stoichiometry 1121324151 and a 27-nt traceable segment of the 38-nt crRNA and the 19-nt traceable segment of a 40-nt target RNA (Figures 1B–D and S4A–B). The overall topology of the ternary complex is composed of two structural filaments that adopt an intertwined helical shape. Two copies of Csm3 labeled C3.1 and C3.2 together with one copy of Csm4 and parts of Csm5 form the major helical filament, while Csm1, Csm2 and parts of Csm5 form the minor helical filament. The two filaments are connected mainly by Csm5 in the head segment and by interactions between Csm1 and Csm4 in the tail segment (Figures 1C and 1D). The crRNA is an indispensable component of the complex to tether all the subunits together, making direct contacts with all four subunits in the major filament (Figures 1D).

A conserved Asp-Gly-Arg interaction pattern was observed between C3.2 and C5, as well as between C3.1 and C3.2 (Figure S4D, inserts), thereby contributing to tethering adjacent subunits together in the major filament, consistent with previous reports that showed that mutation of the conserved Asp145 (for Csm3) shortens the crRNA length in vivo (Hatoum-Aslan et al., 2013; Tamulaitis et al., 2014), indicating fewer tethered subunits in the major filament for this mutation.

We next present the lower resolution 3.6 Å structure of the Csm ternary complex composed of Csm subunits with stoichiometry 1122334151 and a 33-nt traceable segment of the 38-nt crRNA and the 25-nt traceable segment of a 40-nt target RNA (Figures 1B, 1E, and 1F). This second ternary complex reveals that one extra copy each of Csm3 and Csm2 covers an additional 6-nt crRNA-target RNA duplex (compare Figures1C, D with 1E, F).

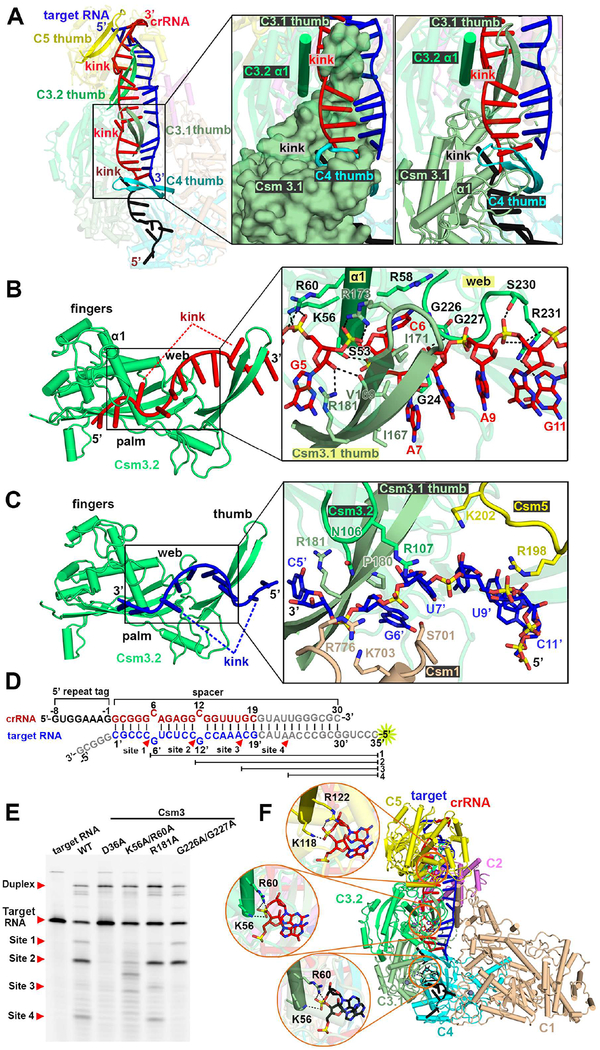

‘5+1’ Repeat Pattern of Bound crRNA-Target RNA Duplex

The periodic ‘5+1’ repeat segment is positioned for interaction with three different protein subunits, where 5 consecutive base pairs are followed by a 1 base pair gap, whereby two unpaired nucleotides on partner strands loop out in opposite directions following insertion by the thumb motifs of either Csm3 or Csm4, resulting in periodic kink sites (Figure 2A, inserts), similar to what has been observed in type I CRISPR-Cas systems (Guo et al., 2017; Mulepati et al., 2014). Starting from the 5’-end of the crRNA, the first kink is associated with the thumb of Csm4, followed by kinks associated with the thumbs of Csm3.1 and Csm3.2, with no kink associated with the thumb of Csm5 (Figure 2A). The structure of each ‘5+1’ repeat is superposable with a root mean square deviation (rmsd) of ~0.33 Å over 251 atoms, but the duplex covered by Csm5 is significantly different from the duplexes covered by Csm3.1 and Csm3.2 (Figure S5B). The number of periodic ‘5+1’ patterns is equal to that of interacting Csm3 subunits lining the backbone.

Figure 2. ‘5+1’ Repeat Pattern of crRNA-Target RNA Duplex in Ternary Complex.

(A) The thumbs of Csm4 and Csm3 subunits kink the crRNA-target RNA duplex every 6th nucleotide, with no kink associated with the thumb of Csm5. The inserts show that the 6th nucleotide segment is stabilized by three different subunits.

(B) The specific interactions between crRNA (nucleotide G5 to G11 in red) and Csm3 are labeled.

(C) The potential interactions between target RNA (nucleotide C5’ to C11’ in blue) and protein residues within a 4 Å distance.

(D) Potential cleavage sites and generated fragments are mapped on the target RNA sequence.

(E) Cleavage of target RNA by Csm3 mutants in the context of the CsmcrRNA-ternary RNA complex.

(F) The conserved Arg-Lys interaction network in different subunits and crRNA.

See also Figures S2 and S5.

Intermolecular Contacts within ‘5+1’ Repeat Patterns

The positioning of the crRNA (in red) and target RNA (in blue) within the Csm3.2 fold in the ternary complex is shown in Figures 2B and 2C, respectively. A series of interactions are observed between crRNA and several conserved residues in the first α-helix (α1) of the palm (S53, K56, R58, R60), together with the web (G226, G227 and R231), and the thumb (I167, I171, R173 and R181) elements (Figures 2B and S5A).

We have undertaken cleavage assays on wild-type and selective dual mutants of the CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complex, with cleavage monitored using 5’-FAM-labeled target RNAs. The four cleavage sites are labeled product 1, 2, 3 and 4 as shown schematically in Figure 2D. Experimentally, for the wild-type complex, the major cleavage occurs at site 2 following 15 min incubation, which correlates well with the major species having a 1121324151 stoichiometry (Figure S3A). Cleavage is almost lost for the K56/R60 to Ala dual mutant, but there is no effect on cleavage of G226/G227 to Ala dual mutant and R181A mutant (Figure 2E). We observe a common binding pattern between Csm3.1/3.2 K56/R60 and Csm5 K118/R122 residues with crRNA (Figure 2F), revealing that key conserved residues on the α1 helix appear to be critical for alignment of the crRNA to achieve its RNA targeting activity. In agreement, published mutations in Cmr4 of the chimeric Cmr complex (corresponding to K56 and R60 in Csm3) abolish target RNA cleavage activities (Osawa et al., 2015). The absence of base-specific contacts between protein residues and bases of the crRNA within the ‘5+1’ repeat accounts for the lack of sequence specificity for spacer sequence recognition.

The crRNA-target RNA pairing follows the ‘5+1’ rule but there are fewer intermolecular contacts involving the target RNA (Figure 2C, insert) relative to the crRNA (Figure 2B, insert) in the ternary complex. Such a target RNA binding pattern might facilitate release of the 6-nt segments following cleavage, thereby initiating a switch in the HD domain of Csm1 into the inactive state in order to protect against uncontrolled target RNA-activated DNase activity that would be toxic to the cell (Kazlauskiene et al., 2016).

Looped out bases associated with the ‘5+1’ repeat are positioned in pockets lined by hydrophobic stacking interactions for both crRNA (Figure S5C) and target RNA strands (Figure S5D).

Assembly of crRNA 5’-Repeat Tag

Nucleotides in the 5’-tag of crRNA, numbered −8 to −1 according to convention (Figure 3A), interact with Csm4 and Csm3.1, forming an ‘S’ shaped topology (Figure 3B). The structure of Csm4 resembles that of Csm3, namely consisting of a palm, web and thumb domains (Figures 3B and S4C). This 8-nt 5’-repeat tag has been proposed to sense the base-pairing potential with 3’-flanking sequence of the target RNA.

Figure 3. Assembly of the 5’-Repeat Tag.

(A) Schematic drawing for the sequences of crRNA and target RNA, related to Figure 1B.

(B) Recognition of the S-shaped 5’-repeat tag by Csm4 and Csm3.1. Arrows pointed towards inserts provide detailed interactions.

(C) The −2 to −5 nt stack is sandwiched by three different subunits, but exposed to solvent.

(D and E) Impact of crRNA (D) and Csm protein (E) mutants on target RNA cleavage in the context of the CsmcrRNA-ternary RNA complex.

See also Figure S5.

In our structure of the ternary complex, not all the positions in the 5’-tag are available for base-pairing (Figure 3B). The −1G nucleotide is kinked by the thumb of Csm4 (sequence alignment of Csm4 from different species is shown in Figure S5E), with this kink separating the 5’-tag and 3’-spacer sequences. The generation of this kinked nucleotide is reminiscent of how the Csm3 thumb achieves kinks within the spacer RNA duplex segment. The Csm4 thumb provides similar residues (L134, R136, I143, Y144) to kink −1G and stabilize flanking −2A and 1G (Figure 3B, right insert).

In addition to −1G, the first three nucleotides (−8G, −7U and −6G) are splayed apart through interactions with the α1 helix of the palm and two thumb-like domains. A set of conserved protein residues (A27, G234 and H269) are responsible for stacking with RNA bases via van der Waals contacts (Figures 3B, left insert and S5E). In addition, there are sequence specific contacts between nucleotide bases (−8G, −7U and −6G) and residues in Csm4 (Figure 3B, left insert). A triple substitution at the −8 to −6 position by replacement of the purine-pyrimidine-purine GUG element by CAC resulted in a shift in cleavage by 1-nt (Figure 3D), which may reflect insertion of purine-pyrimidine-purine ACG rather CAC into the pockets. By contrast, single base substitutions −8G to C, −7U to A and −6G to C showed cleavage propensity comparable to wild-type in vitro (Figure 3E). The 5’-OH group of nucleotide −8G is anchored by the main-chain amide of Y271 (Figure 3B, left insert), but replacement of the 5’-OH by a phosphate results in cleavage activity comparable to wild type (Figure 3D).

Intriguingly, nucleotides at positions −2 to −5 form a stacked alignment adopting a pseudo A-form configuration (Figure 2A). The conserved residues Y144 and W235 in Csm4 stack with nucleotides −2A and −5G via van der Waals contacts, respectively (Figure 3B, middle insert), thereby bracketing the stacked −2 to −5 segment. Nevertheless, the cleavage propensity of Y144A and W235A mutants were comparable to wild-type (Figure 3E). The α1 helix of the palm of Csm3.1 and the web of Csm4 form extensive polar contacts with the RNA backbone only, leaving the Watson-Crick edges of the bases exposed to solvent (Figures 3B, middle insert and 3C). Replacement of −5 to −1 residues GAAAG, the first four of which are directed outwards and available for pairing, by CUUUC, exhibited a cleavage pattern comparable to wild-type, as expected, on cleavage propensity (Figure 3D). This binding mode suggests that there are no specific nucleotide requirements at these positions, consistent with previous reports that mutation of any of the nucleotides at position −2 to −5 does not affect S. epidermidis Type III-A CRISPR-Cas immunity in vivo (Hatoum-Aslan et al., 2011). These observations show that the 3’-flanking sequence of target RNA can pair with these four positions of the 5’-tag (position −2 to −5), providing a mechanism for distinguishing between self and non-self target RNA. Consistently, three studies have demonstrated that only complementarity to these four nucleotides (positions −2 to −5) is sufficient to suppress DNA degradation (Kazlauskiene et al., 2016; Marraffini and Sontheimer, 2010; Pyenson et al., 2017).

Collectively, our structural data are consistent with the kink at position −1 serving as a start site for the measurement of cleavage sites within the spacer region of crRNA, with the nucleotides at positions −8 to −6 playing an important role in the alignment of crRNA, while those at positions −5 to −2 serving as a sensor to avoid autoimmunity.

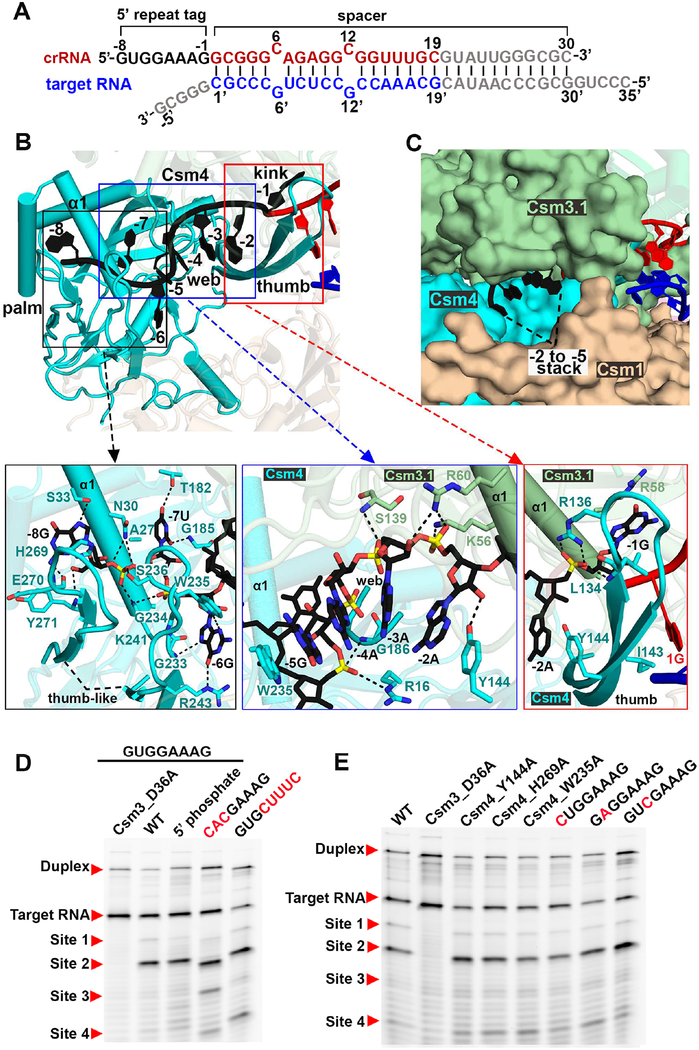

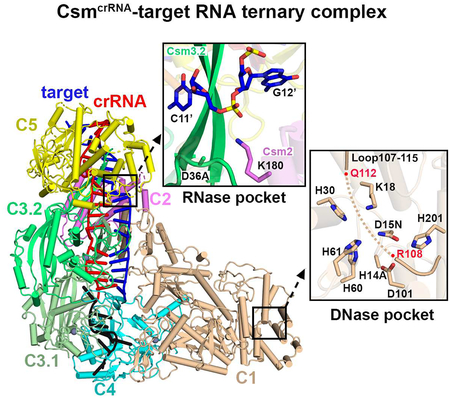

RNase Catalytic Pocket Within Csm3 Subunits

Individual scissile phosphates in the target RNA strand are positioned at the juxtaposition of three subunits, as shown by the positioning of Csm1, Csm3.1 and Csm3.2 for cleavage at the 5’−6’ step (dashed black circle, Figure 4A, left insert). The highly conserved indispensable D36 residue of Csm3 is located right under the scissile bond with a distance of ~6.4 Å as measured from Cβ of Asp (mutated to Ala to avoid cleavage of target RNA in our Csm3 construct) to the non-bridging P-O3’ phosphate oxygen (Figure 4A, right insert). This distance appears to be reasonable given that the ribonuclease activity of the Csm complex is divalent cation dependent (Park et al., 2017), with the potential for a hydrated divalent cation to be positioned between the Asp side chain and the P-O3’ phosphate oxygen. The periodic positioning of D36 residues on Csm3.1 and Csm3.2 subunits leads to the cleavage of the phosphate backbone between nucleotides 5’ and 6’, and between 11’ and 12’ of the target RNA.

Figure 4. RNase and DNase Catalytic Pockets.

(A) The critical catalytic residue Asp36 present in the periodic arrangements. The insert on the left shows the binding surface of the first periodic duplex. The insert on the right presents interactions that might contribute to RNase activity.

(B) Formation of the well-positioned catalytic loop upon crRNA binding.

(C) Impact of RNase cleavage pocket Csm protein mutants on target RNA cleavage in the context of the CsmcrRNA-ternary RNA complex.

(D) Structural presentation of DNase catalytic pockets in the Csm1 HD domain. His14 and Asp15 were respectively mutated into Ala and Asn. Main chain of loop (107–115) is shown in a ribbon representation with residues R108-Q112 disordered.

(E) Target RNA-activated DNase cleavage by wild-type and complexes containing Csm1 mutants in the context of the CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complexes. Loop/GGS mutant indicates that residues 107–115 were replaced by a GGS linker. ΦX174 virion ssDNA was used as substrate.

See also Figures S5 and S6.

The position of D36 within the catalytic loop is critical for its catalytic activity. The catalytic loop and thumb are disordered in the structure of Methanocaldococcus jannaschii Csm3 in the absence of crRNA (Numata et al., 2015), but both become ordered in our structures of Csm3 in the CsmcrRNA binary (see below) and CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary (in green, Figure 4B) complexes. Importantly, binding of crRNA stretches out the Csm3 thumb, resulting in the catalytic loop packing against the thumb, with the two elements mutually stabilizing each other through main chain hydrogen bond formation (Figure 4B, insert). Cleavage assays indicate that while cleavage is lost for the D36A and D36N mutants, the cleavage propensity for the H22A and K41A mutants are similar to wild-type (Figure 4C). Nevertheless, our structure stresses the importance of the correct alignment of the catalytic loop via main chain hydrogen bond formation for the ribonuclease activity of the Csm complex.

Together, binding of crRNA stretches the Csm3 thumb, thereby positioning the catalytic loop in the correct orientation for RNA cleavage, while the crRNA-guided effector complex detects and binds to the complementary target RNA, subsequently cutting it into 6-nt fragments that are released into solution.

DNase Catalytic Pocket within Csm1 Subunit

The DNase catalytic pocket is located in the Csm1 HD domain (Figure 4D, insert), with two of its catalytic residues mutated (D15N and H14A) in the ternary complex in anticipation of eventually generating complexes in the presence of non-cleaved ssDNA. It should be noted that a nearby loop (Csm1 HD domain residues 107–115) is not well traceable with residues 108–112 totally disordered in the absence of bound ssDNA in these complexes (Figure S6B, top panel). Our DNA cleavage assays indicate that wild-type CsmcrRNA is able to cleave ssDNA mediated by target RNA binding (Figure 4E), while mutation of the conserved residues H14/D15, K18, H60/H61 and D101 into alanine within the DNase catalytic pocket (Figures 4D, insert, and S6A) abolished ssDNA cleavage activities under the same conditions (Figure 4E). Notably, replacement of the loop residues (107–115) by a shortened GGS linker, or even single mutation of conserved R108 into alanine abolished the ssDNA cleavage activity, establishing the critical role of this loop, and specifically R108, for ssDNA cleavage.

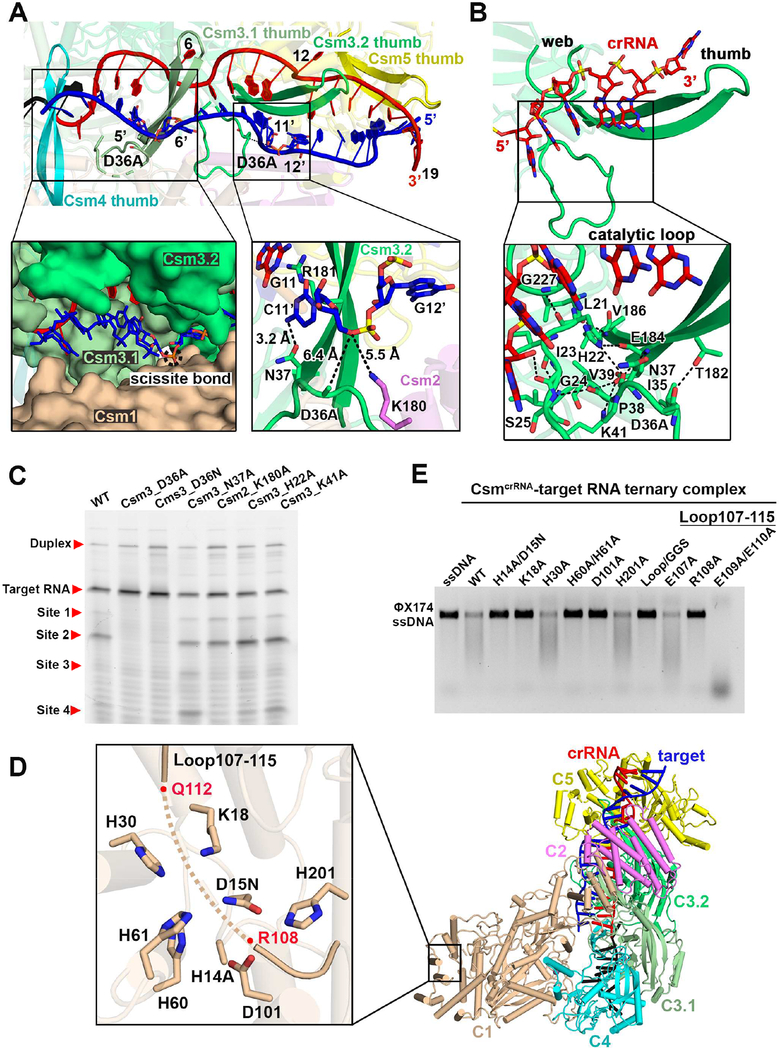

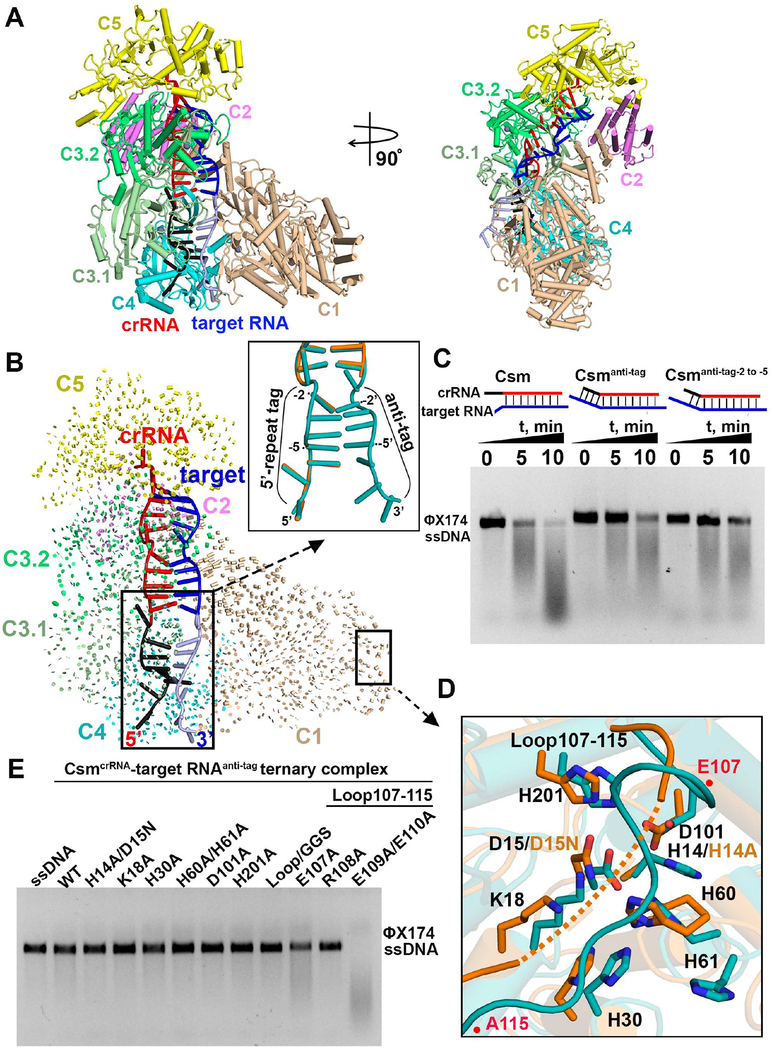

Topology of CsmcrRNA Binary Complex

The 3.0 Å resolution structure of CsmcrRNA binary complex is composed of Csm subunits with stoichiometry 1121324151 and a 25-nt traceable segment of a 38-nt crRNA (Figures 5A and S6C–E). crRNA binding tethers all the subunits of Csm complex together (Figures S1B and S1C). These subunits assemble in an intertwined helical shape on crRNA binding to form the CsmcrRNA binary complex (Figure 5A) in a manner similar to that observed on CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complex formation (Figure 1D).

Figure 5. Minimal Conformational Changes in CsmcrRNA upon Target RNA Binding.

(A) Top and side views for cryo-EM structure of CsmcrRNA binary complex.

(B) Superposition of crRNA in the binary complex (in silver) and crRNA-target RNA duplex (in red) in the ternary complex.

(C) Structure comparison between CsmcrRNA binary complex and CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complex based on alignment of the Csm4 subunit. Vector length correlates with the domain movement scale.

(D) Structural comparison of the catalytic residues in the RNase catalytic pocket of CsmcrRNA binary complex (in silver) and CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complexes (in orange). His14 and Asp15 were respectively mutated into Ala and Asn in CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complexes, respectively.

(E) ssDNA cleavage by CsmcrRNA binary complex and CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complexes.

(F) The slight movement of the catalytic residues in DNase catalytic pocket on transition from CsmcrRNA binary complex (in silver) to CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complexes (in orange).

(G) ssDNA cleavage by wild type and complexes containing Csm1 mutants in the context of the CsmcrRNA binary complexes.

See also Figures S6, S7 and Table 1.

Conformational Changes in Csm Thumb Elements on Binary Complex Formation with crRNA

To explore how the Csm complex assembles without and with crRNA prior to target RNA binding, we determined the crystal structure of T. onnurineus Csm1-Csm4 subcomplex at 2.9 Å resolution. The superposition of structures of free and crRNA-bound states for both Csm1-Csm4 (Figure S7A) and Csm3 (Figure S7B) establish that upon crRNA binding, the thumbs of Csm3 and Csm4 which are disordered in the free state, stretch out and are observable on binding crRNA (Figures S7A, top insert and S7B, insert). In addition, we also observe a shift in an Asn residue (position 38 in M. jannaschii Csm3 and position 37 in T. onnurineus Csm3) in the catalytic loop on comparing Csm3 in the free state with that in the bound state reflecting a conformational transition (Figure S7B, insert), thus emphasizing the importance of crRNA binding for the right positioning of the catalytic loop.

Minimal Conformational Changes in CsmcrRNA on Ternary Complex Formation with Bound Target RNA

The CsmcrRNA binary and CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complexes superpose with an rmsd of 0.661 Å. The crRNA in the ternary complex (in red, Figure 5B) essentially superposes with its counterpart in the binary complex (in silver, Figure 5B). This result for the type III-A Csm complex, which contains intrinsic Csm3 catalytic subunits, contrasts with a pronounced conformational change in the crRNA on ternary complex formation in the type I-F Csy complex (Guo et al., 2017), which requires a trans-acting catalytic Cas3 nuclease-helicase for target DNA cleavage.

We only observe small conformational transitions of the protein subunits on ternary complex formation in the Csm complex, reflecting slight opening up the target RNA binding channel in both directions on ternary complex formation (Figure 5C). This may reflect the limited number of intermolecular contacts involving the target RNA that are restricted to residues on the thumb that are responsible for stacking with the bases of target RNA at the cleavage site (Figures 4A, right insert and S5D) and a few basic residues involved in sequence-nonspecific interactions with the kinked region of target RNA (Figure 2C, insert).

RNA Catalytic Pocket on Ternary Complex Formation

The RNA catalytic pocket of Csm3.2 in the binary complex containing intact D36 (in silver, Figure 5D) and ternary complex containing D36A mutant (in orange, Figure 5D) show small differences with a slight movement of catalytic residue 36 towards the cleavable phosphate between 11’ and 12’ on the target RNA. It appears that the RNA catalytic pocket may be essentially preformed with only minor conformational changes accompanying target RNA complex formation.

Release of an Autoinhibitory DNase Catalytic Pocket on Ternary Complex Formation

Our biochemical results demonstrated that the CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complex is DNase active whereas the DNase activity is repressed in CsmcrRNA binary complex (Figures 5E and S7C). The ssDNA catalytic pocket of Csm1 in the binary complex containing intact H14 and D15 (in silver, Figure 5F) and the ternary complex containing H14A and D15N mutants (in orange, Figure 5F) shows minimal differences. It should be noted that the main chain of the nearby loop (Csm1 HD domain residues 107–115) is traceable in the binary complex (Figure S6B, middle panel) relative to the ternary complex (Figures S6B, top panel), suggesting that the loop may be locked in the binary complex. Importantly, mutations of acidic residues E107 and E109/E110 in this loop turn on the nuclease activities even in absence of target RNA (Figure 5G), indicating that these acidic residues play a key role in inhibiting DNase activity in the binary complex, suggestive of this loop potentially adopting an autoinhibitory conformation.

Structural Comparison between CsmcrRNA-target RNA and CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag ternary complexes

To investigate how the base pairing between crRNA 5’-handle sequence and the anti-tag sequence in target RNA is responsible for self versus non-self discrimination, we solved the cryo-EM structure of CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag ternary complex at 3.1 Å resolution (Figures 6A and S6F–H). The overall structure adopts a similar architecture to the CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complex, with an rmsd of 0.752 Å (Figure 6B). The crRNA-target RNA duplex in the CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag complex (in teal, Figure 6B, insert) essentially superposes with its counterpart in the CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complex (in orange, Figure 6B, insert), with extra density corresponding to the anti-tag sequence. Only nucleotides at position −2’ to −5’ in the anti-tag region base-pair with the nucleotides at position −2 to −5 in the 5’-tag of crRNA, with few interactions observed with protein residues (Figure S7D). As anticipated, binding of target RNA with anti-tag sequence inhibited but did not abolish DNase activity of the wild-type protein (Figures 6C, left and middle panel and S7C), with base-pairing only at position −2 to −5 in the 5’-tag of crRNA sufficient for inhibition of ssDNA cleavage (Figures 6C, right panel and S7C), with this result correlating well with previous functional studies (Kazlauskiene et al., 2016; Marraffini and Sontheimer, 2010). Superposition of ssDNA catalytic pocket of Csm1 in the CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag complex containing intact H14 and D15 (in teal, Figure 6D) and CsmcrRNA-target RNA complex containing H14A and D15N mutants (in orange, Figure 6D) also show minimal differences between states but with a locked loop on the top of the catalytic pocket in the CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag complex (Figures 6D and S6B, bottom panel) similar to those observed for CsmcrRNA binary complex (Figure 5F). Similarly, mutation of acidic residues E107, E109/E110 on the loop activates ssDNA cleavage activities in the CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag complex (Figure 6E), suggesting that the acidic residues also play an essential role in inhibition of ssDNA cleavage in the CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag complex.

Figure 6. Minimal Conformational Changes upon Binding of anti-tag to 5’-tag in Csm Ternary Complex.

(A) Top and side views of cryo-EM structure of CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag ternary complex.

(B) Structural comparison between CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag and CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complexes based on alignment of the Csm4 subunit. Vector length correlates with the domain movement scale. Insert shows superposition of crRNA-target RNA duplex in CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag (in teal) and CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complex (in orange).

(C) ssDNA cleavage by ternary CsmcrRNA-target RNA, CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag and CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag −2 to −5 containing anti-tag sequence only at position −2 to −5.

(D) Superposition of the catalytic residues in the DNase catalytic pocket between CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag (in teal) and CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary (in orange) complexes. His14 and Asp15 were respectively mutated into Ala and Asn in CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complexes, respectively.

(E) ssDNA cleavage following 5 min incubation by the wild type and complexes containing Csm1 mutants in the context of the CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag complexes.

See also Figures S6, S7 and Table 1.

DISCUSSION

Our findings provide (1) the molecular basis for Csm assembly mediated by bound crRNA and associated subunit stoichiometry, (2) identify the role of the crRNA 5’-repeat tag in defining the 5’-ruler mechanism for defining target cleavage sites, (3) define periodic kinks in the crRNA-target RNA duplex facilitating cleavage of the target RNA with 6-nt periodicity, (4) identify key Glu residues within a loop segment of CsmcrRNA that adopt a proposed autoinhibitory conformation thereby suggestive of regulation of the DNase activity of the HD domain, (5) define the role of a key Arg within the same loop segment in catalyzing target RNA-mediated cleavage of ssDNA by the HD domain and (6) provide insights into self versus non-self recognition in a type III-A CRISPR-Cas system based on accessibility of positions −2 to −5 within the 5’-repeat serving as sensors for avoidance of autoimmunity.

Stoichiometry and Cleavage Pattern of the T. onnurineus Csm Ternary Complex

The major sizing column Csm peak corresponding to the T. onnurineus ternary complex (Figure S1D) contained complexes defined by our cryo-EM studies with stoichiometries 1121324151 (one Csm2 and two Csm3) (Figures 1C and 1D) and 1122334151 (two Csm2 and three Csm3) (Figures 1E and 1F), which should give cleavage patterns marked site 2 and 3, respectively. We observe strong cleavage corresponding to site 2 but not to site 3 (Figures S2C and S2D). We do not have a definitive explanation for this distinct pattern that shows minimal cleavage at site 3, but perhaps this could reflect a larger proportion of 1121324151 over 1122334151, in some sense reflecting the ratio of complexes observed in the 3D cryo-EM classification (Figure S3A). Notably, both the protein and RNA components can be overlaid for the lower half of the 1121324151, and 1122334151 Csm complexes (Figures S7E and S7F), as do the RNase (Figure S7G) and DNase (Figure S7H) binding pockets between the two complexes. In addition, previous reports show that base-pairing for the lower half of the complex between the crRNA and target RNA, but not the upper half, is most important for activation of ssDNA cleavage activities both in vivo (Pyenson et al., 2017) and in vitro (Kazlauskiene et al., 2016). Thus, we propose that both stoichiometric 1121324151 and 1122334151 Csm complexes should be functional for RNA and DNA cleavage.

A related distribution of stoichiometries has also been observed in previous Streptococcus thermophilus type III-A CRISPR-Cas system (Tamulaitis et al., 2014) and cryo-EM based structural studies of type III-B Cmr complexes (Taylor et al., 2015). Previous in vivo studies also show that different mature crRNAs with 6-nt difference are present in Staphylococcus epidermidis type III CRISPR-Csm system (Hatoum-Aslan et al., 2011) and Pyrococcus furiosus type III CRISPR-Cmr system (Hale et al., 2008), suggesting different stoichiometries might also exist in the same species in vivo.

It should be pointed out that diverse stoichiometries are anticipated amongst different species in type III-A systems, given the various dimensions of published Csm negative-stain EM structures in different species (Park et al., 2017; Rouillon et al., 2013; Staals et al., 2014).

5’-Ruler Mechanism Dictates Positioning of Target RNA Cleavage Sites

The precursor crRNA is first transcribed from the CRISPR array and further processed by the Cas6 endoribonuclease into the intermediate crRNA (Carte et al., 2008). Once the intermediate crRNA is loaded into the Csm complex, the thumbs of Csm3 and Csm4 will be stretched out and segment the spacer region of crRNA at 6-nt nucleotide intervals (Figures 5A, S7A and S7B), resulting in the catalytic loop packing against the thumb, thereby positioning the catalytic residue D36 for targeting the scissile bond (Figures 4A and 4B).

The specific assembly mode of 8-nt 5’-tag by Csm4 should account for the 5’ ruler mechanism, as the kinked −1G nucleotide separates the 5’-tag and 3’-spacer sequences (Figure 3B). This 6-nt length difference might be correlated with different number of Csm3 subunits assembled in the complex, given that each Csm3 subunit segments 6-nt crRNA (Figure 2). Csm5 covers the head of the complex and is associated with the 3’-end of crRNA where the trimming process occurs during crRNA maturation, thereby correlating well with previous reports that Csm5 is required for crRNA maturation (Hatoum-Aslan et al., 2011).

Periodic Cleavage of Target RNA at 6-nt Intervals

Type III systems cleave target RNA at 6-nt intervals but not target DNA paired with the crRNA. This can be explained from previous studies on the chimeric Cmr ternary complex where cleavage at the splayed apart scissile step was shown to require a 2’-OH, which following activation targets the adjacent phosphate resulting in cleavage of the P-O5’ bond, and formation of a cyclic 2’,3’-phosphate at the 3’-end and a 5’-OH at the 5’ end (Osawa et al., 2015). The catalytic pocket within the Csm3 subunit for target RNA cleavage is shown in Figure 4A (right insert). It is unclear what general base activates the 2’-OH, but D36 (mutated to Ala in our structure) is likely positioned to act as a general acid, potentially involving divalent cation-mediated stabilization of the developing negative charge on the O5’ atom following cleavage. Consistent with the importance of D36 to catalysis (Figure 4A, right insert), Ala or Asn mutants of this residue result in loss of target RNA cleavage (Figure 4C).

Autoimmunity Suppression

The base-pairing potential between the 8-nt 5’-repeat tag of crRNA and 3’ flanking sequence of target RNA, rather than PAM recognition, is believed to be responsible for discriminating self from non-self in type III CRISPR-Cas systems (Elmore et al., 2016; Estrella et al., 2016; Kazlauskiene et al., 2016; Marraffini and Sontheimer, 2010; Pyenson et al., 2017). In our structure of the Csm ternary complex, only four nucleotide bases at positions −2 to −5 in the 5’-repeat tag are exposed to solvent, and have the potential to base pair with the target RNA (Figures 3B and 3C), whereas others are flipped out and buried by the effector complex. Notably, base-pairing was only observed at positions −2 to −5 in our structure of the CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag ternary complex (Figure 6B, insert), explaining previous results that pairing restricted to positions −2 to −5 between the 5’-repeat tag and 3’-flanking sequence of target RNA (pairing complementarity observed for self but absent for non-self) contribute to type III-A CRISPR-Cas autoimmunity suppression (Kazlauskiene et al., 2016; Marraffini and Sontheimer, 2010; Pyenson et al., 2017). Our in vitro ssDNA cleavage results also show that target RNA containing the anti-tag sequence, or only containing base-pairing at position −2 to −5, suppresses the DNase activities of the complex (Figure 6C).

Formation and Release of the Proposed Autoinhibitory Conformation of the DNase pocket

We focus on a loop segment (107–115) positioned in the vicinity of the DNase cleavage pocket within the Csm1 subunit that is partially disordered in the various Csm complexes reported in this study. We have performed structure-based mutational analysis, and demonstrated that this loop (107–115) contributes to switching on/off of the ssDNase activity of the Csm1 subunit of the type III-A Csm CRISPR system. Mutation of acidic residues (single E107 and dual E109/E110 mutants) within this loop to alanine activates ssDNA activity in both the CsmcrRNA binary complex (Figure 5G) and the CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag ternary complex (Figure 6E), indicating the critical role of these acidic Glu residues in inhibition of ssDNase activity. We anticipate that these Glu residues within loop (107–115) could play an autoinhibitory role, thereby locking the loop in a rigid conformation in the CsmcrRNA binary (Figure S6B, middle panel) and CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag ternary (Figure S6B, bottom panel) complexes, presumably by preventing access of ssDNA to the DNase catalytic pocket. By contrast, we propose that this conformational lock is released in the CsmcrRNA-target RNA complex (Figure S6B, top panel), allowing access to ssDNA for binding in the catalytic pocket, potentially allowing the DNA phosphates of ssDNA to occupy the position of the released Glu residues in the autoinhibitory conformation. Notably, ssDNase activity was abolished either following replacement of the entire loop (107–115) by a GGS linker, or more importantly following replacement of a single amino acid R108 by alanine (Figure 4E). This implies that both the alignment/flexibility of the loop, and specifically R108 within it, plays a major role in DNase cleavage activity. These structural observations correlate well with a recent report, that the Csm1 subunit responsible for ssDNA cleavage is locked in a static configuration in S. epidermidis DNase-inactive Csm-target RNAanti-tag ternary complex, but displays rapid conformational fluctuations in DNase-active CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complex (Wang et al., 2018).

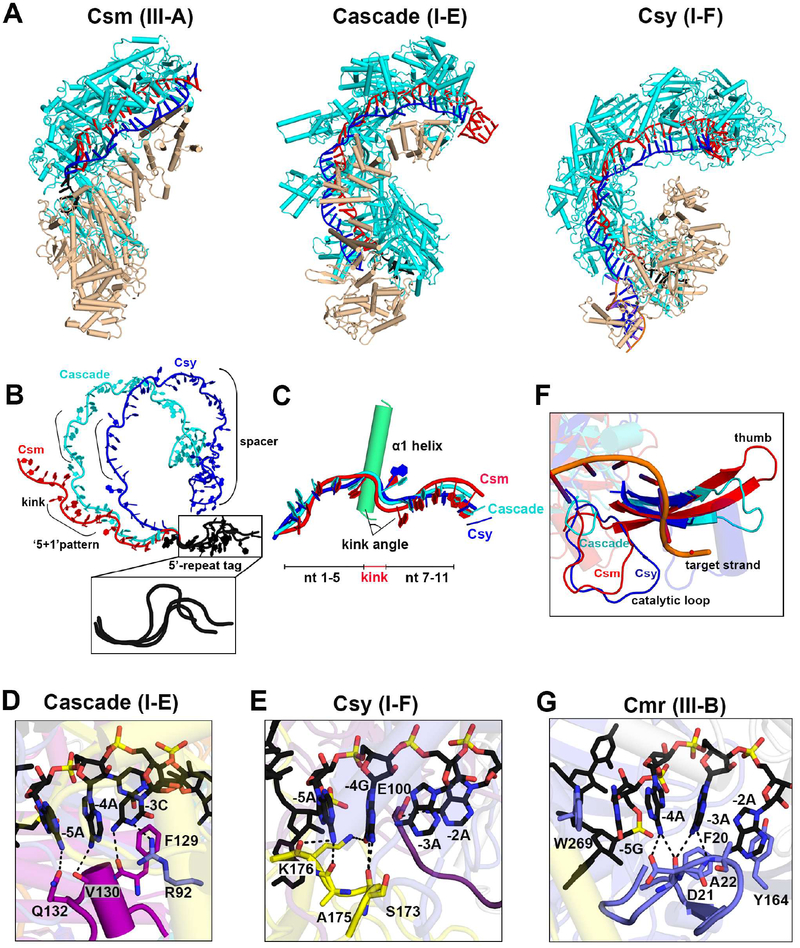

Comparison of type III-A with type I-E and I-F CRISPR Complexes

The overall architecture of the type III-A Csm complexes consist of two structural filaments, with features more similar to the architecture of type I-E Cascade complexes than to type 1-F Csy complexes, given that the latter lacks the small filament (Figure 7A). The sugar-phosphate backbones of crRNA from Csm (type III-A), Cascade (type I-E) and Csy (type I-F) complexes share a conserved ‘5+1’ repeat pattern (Figure 7B). The specific interactions between the crRNA phosphate backbone and Cas7-like proteins in different multi-subunit CRISPR systems kink the crRNA to different angular extents (Figure 7C), which in turn correspond with large-scale structural differences in overall crRNAs alignment and resulting helical pitch of the Cas7 backbone (Figure 7B). Despite the different kink angles and lengths of spacer segments, these multi-subunit CRISPR systems share a conserved ‘S’ shaped fold of the of 8-nt 5’-repeat tag (Figure 7B, insert) adjacent to the spacer segment. For type III-A system, nucleotide bases at position −2 to −5 in the 5’-tag responsible for discriminating self and non-self are fully exposed to the solvent and ready to sense the target, just like their spacer segment counterparts (Figure 3B, middle insert). By contrast, the corresponding bases of the 5’-tag are occluded by their own amino acid residues in Type I-E and Type I-F systems (Figures 7D and 7E), which instead rely on PAM sequences rather than the 5’-tag to avoid autoimmunity. Besides these differences, type III effector complexes rely on their own intrinsic nuclease activity to degrade target RNAs. Thus, the catalytic loop of type III-A Cas7-like protein Csm3 is critical for its RNase activities. Structurally equivalent loops also exist in type I Cas7-like proteins (Figure 7F), but lack the ability to degrade dsDNA targets, which are instead cut by recruiting a trans-acting helical-nuclease Cas3 (Sinkunas et al., 2011; Westra et al., 2012).

Figure 7. Structural Comparisons between Type III and Type I Effector Complexes.

(A) Overall architecture of type III-A (Csm), I-E (Cascade, PDB: 4QYZ), and I-F (Csy, PDB: 6B44) ternary complexes. The major filaments, minor filaments, crRNA and target RNA are colored in cyan, wheat, red and blue, respectively.

(B) The observed different pitches of bound crRNA in different CRISPR systems.

(C) Superposition of nucleotides (nt) 1–5 of the crRNA from each CRISPR system.

(D, E and G) Base-specific interactions between amino acids and the stacked bases of the 5’-tag in the type I-E Cascade (D), type I-F Csy (E) and type III-B chimeric Cmr (PDB: 3X1L) (G) complex.

(F) Structural comparisons of the catalytic loop in Csm complex (in red) with structurally related loops in Cascade (in cyan) and Csy (in blue) complexes. The target strand is from the Csm ternary complex.

Comparison with Structures of Type III-B Cmr Complexes

Our cryo-EM based structures of type III-A CsmcrRNA binary (3.0 Å), CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary (3.1 Å) and CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag ternary (3.1 Å) complexes have yielded insights regarding assembly, target RNA recognition, periodic RNA cleavage, autoinhibition and release of the DNase catalytic pocket, and autoimmunity suppression that complement insights obtained from a X-ray study (2.1 Å) of Cmr1-deficient chimeric type III-B CmrcrRNA bound to ssDNA (Osawa et al., 2015) and a cryo-EM based structures of type III-B CmrcrRNA binary (4.1 Å) and CmrcrRNA-target RNA ternary (4.4 Å) complexes (Taylor et al., 2015).

Our contribution represents a significant advance given the limitation of the X-ray structure, despite its high resolution, in that it lacked the Cmr2 HD domain responsible for ssDNA cleavage, that it required a chimeric mixture of Cmr subunits from different species and that the crRNA was bound to target DNA rather target RNA (Osawa et al., 2015). Importantly, all the nucleotide bases in the 5’ tag, which should also be responsible for potential base pairing with the 3’-flanking sequence of target RNA in the Cmr complex (Elmore et al., 2016), are blocked by amino acids (Figure 7G).

Our higher resolution cryo-EM Csm structures allowed structural characterization in greater detail of bound protein and RNA and precisely defined alignments and intermolecular contacts and catalytic pocket architectures necessary for a detailed mechanistic understanding of function.

STAR*METHODS

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for reagents could be directed to, and will be fulfilled by Lead Contact Dinshaw Patel (pateld@mskcc.org)

METHODS DETAILS

Protein Expression and Purification

Proteins were expressed and purified as described previously (Park et al., 2017) with some modifications. The full-length Thermococcus onnurineus csm genes, csm1, csm2, csm3, csm4, csm5 were synthesized and cloned into different expression vectors. csm1 and csm4 were subcloned into pRSF-Duet-1 vector (Novagen), in which csm1 was attached with N-terminal His6 tag. csm2 and csm3 were cloned into a modified pRSF-Duet-1 vector (Novagen), in which they were attached with N-terminal His6-SUMO tag following an ubiquitin-like protease (ULP1), respectively. csm5 was cloned into pCDF-Duet-1, in which csm5 was attached with C-terminal His10 tag. Csm1-Csm4 subcomplex, Csm2, Csm3 and Csm5 recombinant proteins were overexpressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) strain by induction with 0.25 mM isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (GoldBio) at 16°C for 20 hr. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 20 mM imidazole, 7 mM β-mercaptoethanol).

The harvested cells that produced Csm1-Csm4 subcompelx were then lysed by the EmulsiFlex-C3 homogenizer (Avestin) and centrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 30 min in a JA-20 fixed angle rotor (Avanti J-E series centrifuge, Beckman Coulter). The supernatant was applied to 5 mL HisTrap Fast flow column (GE Healthcare). The protein was eluted with lysis buffer supplemented with 500 mM imidazole after washing the column with 10 column volumes of lysis buffer and 2 column volumes of lysis buffer supplemented with 40 mM imidazole. The elution fractions were further dialyzed against buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 7mM β-mercaptoethanol), respectively, and applied on 5 mL HiTrap Q Fast flow column (GE Healthcare). Proteins were eluted by a linear gradient from 100 mM to 1 M NaCl in 20 column volumes, and then concentrated in 10 kDa molecular mass cut-off concentrators (Amicon) before further purification over a Superdex 200 increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated in buffer B (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 2 mM DTT).

The recombinant Csm5 was purified by the similar method as above, with a slight difference. The elution from Ni-NTA column were dialyzed against buffer A and loaded on HiTrap Heparin HP column (GE Healthcare). Proteins were eluted by a linear gradient from 100 mM to 1 M NaCl in 20 column volumes, and further purified over a Superdex 200 increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated in buffer B.

The recombinant Csm2 was purified by the similar method as that for Csm1-Csm4 subcomplex purification. Elution fractions of Csm2 with His6-SUMO tag from Ni-NTA column were further dialyzed against buffer A overnight at 4°C by adding ULP1 during dialysis to remove His6-SUMO tag. The tag was separated by reloading the samples on Ni-NTA column, with the flow through loaded on 5 mL HiTrap Heparin HP column (GE Healthcare). The protein was eluted by a linear gradient from 100 mM to 1 M NaCl in 20 column volumes, and further purified over a Superdex 200 increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated in buffer B.

The recombinant Csm3 was purified by the similar method as that for Csm2 purification, with a slight modification. After dialysis against buffer A with addition of ULP1 to remove His6-SUMO tag. Flow through fractions of Csm3 without His6-SUMO tag from Ni-NTA column were loaded on 5 mL HiTrap Q Fast flow column (GE Healthcare). The protein was eluted by a linear gradient from 100 mM to 1 M NaCl in 20 column volumes, and further purified over a Superdex 200 increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated in buffer B.

All mutants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis, and purified by the same methods as above.

In Vitro Assembly of CsmcrRNA Binary, CsmcrRNA-Target RNA and CsmcrRNA-Target RNAanti-tag Ternary Complexes

crRNAs were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. Based on previous proposed Csm1121334151 stoichiometry (Park et al., 2017), purified Csm1-Csm4 heterodimer, Csm2, Csm3, Csm5 and crRNA were mixed at a molar ration of 1: 1.5: 4: 1.5: 1.3 and then incubate at 60°C for 20 min. The complex was further purified by gel filtration chromatography on a Superdex 200 increase 10/300 GL column pre-equilibrated in buffer B. Fractions contain the CsmcrRNA complex were pooled and reloaded on Superdex 200 increase 10/300 GL pre-equilibrated in buffer C (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 250 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT). We also assembled Csm1-Csm4 heterodimer, Csm2, Csm3, Csm5 and crRNA by mixing at a molar ration of 1: 5: 6: 1.5: 1.3 following the same method as described above.

To assemble CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complex, we mutated Asp36 of Csm3 into alanine to avoid target RNA cleavage. To prevent target RNA-activated non-specific DNase activities, His14 and Asp15 of Csm1 were mutated into Ala and Asn, respectively. Purified Csm1H14A/D15N-Csm4 heterodimer, Csm2, Csm3D36A, Csm5 and crRNA were mixed at a molar ration of 1: 1.5: 4: 1.5: 1.3 and then incubate at 60°C for 20 min. Then the target RNA was added into the mixer at a molar ratio of 1.5: 1. After incubation at 60°C for 20 min, the mixture was loaded on a Superdex 200 increase 10/300 GL column pre-equilibrated in buffer B. Fractions contain the CsmcrRNA-target RNA complex were pooled and reloaded on Superdex 200 increase 10/300 GL pre-equilibrated in buffer C.

CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternaryanti-tag complex was assembled by the same method as that for CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complex. we only mutated Asp36 of Csm3 into alanine to avoid target RNA cleavage, and used apoform Csm1 in this complex.

All mutants were assembled by similar methods as above.

Cryo-EM Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition

3.0 μl of ~0.5 mg/ml purified CsmcrRNA binary, CsmcrRNA-target RNA and CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag ternary complexes were applied onto glow-discharged UltrAuFoil 300 mesh R1.2/1.3 grids (Quantifoil), respectively. Grids were blotted for 2s at ~100% humidity and flash frozen in liquid ethane using an FEI Vitrobot Mark IV. Images were collected on FEI Titan Krios electron microscope operated at an acceleration voltage of 300 kV with a Gatan K2 Summit detector with a 1.089 Å pixel size and 8.0 electrons per pixel per second. The defocus range was set from −0.8 μm to 2.5 μm. Dose-fractionated images were recorded with a per-frame exposure time of 200 ms and a dose of ~1.349 electrons per Å2 per frame. Total accumulated dose was ~54 electrons per Å2.

Image Processing

For the CsmcrRNA-target RNA dataset, motion correction was performed with MotionCor2 (Zheng et al., 2017). Contrast transfer function parameters were estimated by Ctffind4 (Rohou and Grigorieff, 2015). All other steps of image processing were performed by RELION 2.1 (Scheres, 2012). Templates for automated particle selection were generated from 2D-averages of ~2,000 manually picked particles. Automated particle selection resulted in 755,189 particles from 1,697 images. After two rounds of 2D classification, a total of 558,984 particles were selected for 3D classification using the initial model generated by RELION as reference. Particles corresponding to the best class with the highest-resolution features were selected and subjected to the second round of 3D classification. Two of 3D classes with good secondary structural features and the corresponding 109,902 particles were polished using RELION particle polishing, yielding an electron microscopy map with stoichiometry 1121324151 with a resolution of 3.1 Å after 3D auto-refinement (Figure S3). Another Class and corresponding 19,111 particles were also polished and refined to get an electron microscopy map with stoichiometry 1122334151 with a resolution of 3.8 Å (Figure S3). The resolution was improved further to 3.6 Å by focused classification together with following 3D refinement and particle polishing.

The dataset for CsmcrRNA binary complex was processed by the same procedure as above. Briefly, 628,985 particles were autopicked from 1,455 images, 129,536 particles were selected for the final 3D reconstruction after two rounds of 2D and 3D classification, resulting in a CsmcrRNA binary complex map with an overall resolution of 3.0 Å (Figures S6C and S6D).

The dataset for CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag ternary complex was processed by the same procedure as outlined above. Briefly, 757,313 particles were autopicked from 1,346 images, 57,170 particles were selected for the final 3D reconstruction after two rounds of 2D and 3D classification, resulting in a CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag ternary complex map with an overall resolution of 3.1 Å (Figures S6E and S6F).

All resolutions were estimated using RELION ‘post-processing’ by applying a soft mask around the protein density and the Fourier shell correlation (FSC) = 0.143 criterion. Local resolution estimates were calculated from two half data maps using ResMap (Kucukelbir et al., 2014). Further details related to data processing and refinement are summarized in Table 1 and Figures S3 and S6.

Table 1.

| Csm1121324151crRNA | Csm1121324151crRNA- target RNA | Csm1122334151crRNA- target RNA | Csm1121324151crRNA- target RNAanti-tag | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection and processing | ||||

| Magnification | 22,500 | 22,500 | 22,500 | 22,500 |

| Voltage (kV) | 300 kV | 300 kV | 300 kV | 300 kV |

| Electron exposure (e−/ Å2) | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 |

| Defocus rang (μm) | −0.8 to −2.5 | −0.8 to −2.5 | −0.8 to −2.5 | −0.8 to −2.5 |

| Pixel size (Å) | 1.089 | 1.089 | 1.089 | 1.089 |

| Initial particles (no.) | 628,985 | 558,984 | 558,984 | 757,313 |

| Final particles (no.) | 129,536 | 109,902 | 30,431 | 57,170 |

| Map resolution (Å) | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.6 | 3.1 |

| FSC threshold | 0.143 | 0.143 | 0.143 | 0.143 |

| Map sharpening B factor (Å2) | −85.50 | −89.63 | −103.21 | −64.40 |

| Refinement | ||||

| Model resolution (Å) | 3.23 | 3.23 | 3.67 | 3.21 |

| FSC threshold | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Model composition | ||||

| Protein residues | 2,083 | 2,161 | 2,529 | 2,115 |

| Nonhydrogen atoms | 16,723 | 17,672 | 20,875 | 17,164 |

| B factors (Å2) | ||||

| Protein | 58.6 | 58.0 | 49.5 | 94.5 |

| Ligand | 64.6 | 74.4 | 42.9 | 100.4 |

| Metal | 72.7 | 64.8 | 36.4 | 109.9 |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.011 | 0.014 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.077 | 1.122 | 1.290 | 1.203 |

| Validation | ||||

| MolProbity score | 1.64 | 1.72 | 2.49 | 1.79 |

| Clashscore | 4.14 | 7.01 | 7.13 | 5.55 |

| Poor rotamers (%) | 0.55 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.61 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||||

| Favored (%) | 93.04 | 92.56 | 91.98 | 92.11 |

| Allowed (%) | 6.96 | 7.44 | 8.02 | 7.89 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Atomic Model Building and Refinement

For the CsmcrRNA-RNA ternary complex, the initial models of Csm1, Csm3 and Csm4 were generated by docking the crystal structure of T. onnurineus Csm1 (PDB: 4UW2), homologous M. jannaschii Csm3 and Csm4 (MjCsm3-Csm4, PDB: 4QTS) into the cryo-EM density map using UCSF Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004), respectively. Models for Csm2 and Csm5 were first generated by SWISS-MODEL online server. Then all docked models were manually rebuilt in COOT (Emsley et al., 2010) to fit the density map. Other parts of the complex were built based on the bulky side chains to register the sequence. Residues in parts of Csm2 and Csm5 were modeled as poly-alanines due to the poor side-chain densities, densities for residues 134–169 in Csm5 is not sufficient to define their sequence order confidently.

For the CsmcrRNA binary, CsmcrRNA-target RNA with stoichiometry 1122334151 and CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag ternary complex, the structure of CsmcrRNA-target RNA ternary complex was docked into the cryo-EM density map using UCSF Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004) and then manually rebuilt in COOT (Emsley et al., 2010). Densities for Csm5 in the CsmcrRNA-target RNA with stoichiometry 1122334151 are not well traceable, through the existing EM density allow us to fit the atomic model of Csm5 into this position at the head of the complex. Also, densities for both Csm2 and Csm5 in the CsmcrRNA-target RNAanti-tag are not well defined. Based on the existing EM density, we docked the respective atomic models into the map. All models were refined against summed maps using phenix.real_space_refine (Adams et al., 2010) by applying geometric and secondary structure restraints. All figures were prepared by PyMol (http://www.pymol.org) or Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004). The statistics for data collection and model refinement are shown in Table 1.

Crystallization, Data Collection, and Structure Determination

Crystals of Csm1-Csm4 subcomplex were grown at 20°C using hanging-drop vapor diffusion by mixing 1 μl protein solution with 1 μl reservoir solution containing 0.1 M phosphate-citrate pH 4.2, 5% PEG3000, 25% 1,2-propanediol, and 10% glycerol. Data were collected at 100 K at the Advanced Photo Source (APS) at the Argonne National Laboratory and processed by HKL suite (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997). Structure was solved by the molecular replacement method using PHENIX. The refinement was performed with REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al., 1997) and COOT (Emsley et al., 2010). The statistics of the diffraction data are summarized in Table S1. All structure figures were prepared with PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org/).

RNA Cleavage Assay

In vitro RNA cleavage assay was performed by incubating 50 nM CsmcrRNA complex and 50 nM 5’-FAM labeled target RNA in 50 μL reaction buffer composed of 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MnCl2 and 3% glycerol at 55°C for 15 min, unless stated otherwise. Reactions were stopped by adding 2 × formamide loading buffer (90% formamide, 0.025% bromophenol blue, 0.025% xylene cyanol, 0.025% SDS, 5 mM DTT) followed by heating at 95°C for 5 min. Samples were analyzed on 15% polyacrylamide denaturing 8 M Urea gel and visualized by Typhoon 9500 scanner.

ΦX174 Virion ssDNA Cleavage Assay

The reactions were performed by mixing 5 nM ΦX174 Virion ssDNA and 200 nM CsmcrRNA complex with or without 5 nM of various target RNAs in reaction buffer (30 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl, 100 mM NaCl and 3% glycerol) supplemented with 5 mM MnCl2 at 55°C for 5 min, unless stated otherwise. Reaction were quenched by adding 2 × loading buffer (4 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 0.01% bromophenol blue, 0.01% xylene cyanol FF, 20% glycerol, 20 mM EDTA), followed by incubation for 5 min at 95°C. The samples were separated on a 1% agarose gel, stained with GelRed (Biotium) for visualization.

90-nt ssDNA Cleavage Assay

The CsmcrRNA complex (10 nM) was mixed with or without various RNA substrates (10 nM) in reaction buffer (30 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl, 100 mM NaCl and 3% glycerol). Radiolabeled ssDNA substrate was then added to a final concentration of 100 nM. The reaction was initiated with 5 mM MnCl2 and incubated at 55°C for 20 minutes. The reaction was then quenched with 2 × formamide buffer and heated to 95°C for 10 minutes. Samples were separated on a 12% Tris/Borate/EDTA gel with 7 M Urea and visualized by phosphorimaging.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

In vitro cleavage experiments were repeated at least three times, and representative results were shown.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession number PDB: 6MUU (Csm1121324151crRNA), PDB: 6MUR (Csm1121324151crRNA-target RNA ternary complex), PDB: 6MUS (Csm1122334151crRNA-target RNA ternary complex), PDB: 6MUT (Csm1121324151crRNA-target RNAanti-tag ternary complex), and PDB: 6MUA (Csm1-Csm4 subcomplex). The cryo-EM density maps have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank under accession number EMDB: 9256 (Csm1121324151crRNA), PDB: 9253 (Csm1121324151crRNA-target RNA ternary complex), EMDB: 9254 (Csm1122334151crRNA-target RNA ternary complex), and EMDB: 9255 (Csm1121324151crRNA-target RNAanti-tag ternary complex

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Ruler mechanism based on 5’-repeat tag dictates positioning of RNA cleavage sites

Kinks in crRNA-target RNA duplex identify periodic RNA cleavage at 6-nt intervals

Pairing potential with positions −2 to −5 within the 5’-repeat regulate autoimmunity

A Glu-rich loop adopts an autoinhibitory conformation regulating DNase activity

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

N.J. and D.J.P. thank Hui Yang, Richard K. Hite and Michael Jason De La Cruz for advice and discussion on cryo-EM aspects of the research. Cryo-EM data sets were collected on 300 kV Titan KRIOS instruments with direct electron detectors at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and the Simons Electron Microscopy Center at the New York Structural Biology Center. X-ray diffraction studies were based upon research conducted at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines, which are funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences from the National Institutes of Health (P30 GM124165). The Pilatus 6M detector on 24-ID-C beam line is funded by a NIH-ORIP HEI grant (S10 RR029205). The latter supported by grants from the Simons Foundation (349247), NYSTAR and NIGMS GM103310, with additional support from the Agourin Institute (F00316) and NIH S10 Od019994–01. This research was supported by funds from the Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center grant, by Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Core Grant (P30CA008748) and from the Office of the President, SUSTech to D.J.P.. C.Y.M. is supported by an NIH NRSA postdoctoral fellowship (1F32GM128271–01). L.A.M. was supported by a Burroughs Wellcome Fund PATH Award, NIH Director’s Pioneer Award (DP1GM128184) and an HHMI-Simons Faculty Scholar Award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

L.A.M. is a cofounder and Scientific Advisory Board member of Intellia Therapeutics and Eligo Biosciences; all of which develop CRISPR-based technologies.

REFERENCES

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. (2010). PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography 66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrangou R, Fremaux C, Deveau H, Richards M, Boyaval P, Moineau S, Romero DA, and Horvath P (2007). CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science 315, 1709–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carte J, Wang R, Li H, Terns RM, and Terns MP (2008). Cas6 is an endoribonuclease that generates guide RNAs for invader defense in prokaryotes. Genes & development 22, 3489–3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S, Carter J, Rollins MF, Golden SM, Jackson RN, Hoffmann C, Nosaka L, Bondy-Denomy J, Maxwell KL, Davidson AR, et al. (2017). Structure Reveals Mechanisms of Viral Suppressors that Intercept a CRISPR RNA-Guided Surveillance Complex. Cell 169, 47–57 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore JR, Sheppard NF, Ramia N, Deighan T, Li H, Terns RM, and Terns MP (2016). Bipartite recognition of target RNAs activates DNA cleavage by the Type III-B CRISPR-Cas system. Genes & development 30, 447–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, and Cowtan K (2010). Features and development of Coot. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrella MA, Kuo FT, and Bailey S (2016). RNA-activated DNA cleavage by the Type III-B CRISPR-Cas effector complex. Genes & development 30, 460–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo TW, Bartesaghi A, Yang H, Falconieri V, Rao P, Merk A, Eng ET, Raczkowski AM, Fox T, Earl LA, et al. (2017). Cryo-EM Structures Reveal Mechanism and Inhibition of DNA Targeting by a CRISPR-Cas Surveillance Complex. Cell 171, 414–426 e412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale C, Kleppe K, Terns RM, and Terns MP (2008). Prokaryotic silencing (psi)RNAs in Pyrococcus furiosus. Rna 14, 2572–2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatoum-Aslan A, Maniv I, and Marraffini LA (2011). Mature clustered, regularly interspaced, short palindromic repeats RNA (crRNA) length is measured by a ruler mechanism anchored at the precursor processing site. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108, 21218–21222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatoum-Aslan A, Samai P, Maniv I, Jiang W, and Marraffini LA (2013). A ruler protein in a complex for antiviral defense determines the length of small interfering CRISPR RNAs. The Journal of biological chemistry 288, 27888–27897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes RP, Xiao Y, Ding F, van Erp PB, Rajashankar K, Bailey S, Wiedenheft B, and Ke A (2016). Structural basis for promiscuous PAM recognition in type I-E Cascade from E. coli. Nature 530, 499–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RN, Golden SM, van Erp PB, Carter J, Westra ER, Brouns SJ, van der Oost J, Terwilliger TC, Read RJ, and Wiedenheft B (2014). Structural biology. Crystal structure of the CRISPR RNA-guided surveillance complex from Escherichia coli. Science 345, 1473–1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazlauskiene M, Tamulaitis G, Kostiuk G, Venclovas C, and Siksnys V (2016). Spatiotemporal Control of Type III-A CRISPR-Cas Immunity: Coupling DNA Degradation with the Target RNA Recognition. Molecular cell 62, 295–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin EV, Makarova KS, and Zhang F (2017). Diversity, classification and evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems. Current opinion in microbiology 37, 67–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucukelbir A, Sigworth FJ, and Tagare HD (2014). Quantifying the local resolution of cryo-EM density maps. Nature methods 11, 63–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Alkhnbashi OS, Costa F, Shah SA, Saunders SJ, Barrangou R, Brouns SJ, Charpentier E, Haft DH, et al. (2015). An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems. Nature reviews Microbiology 13, 722–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova KS, Zhang F, and Koonin EV (2017a). SnapShot: Class 1 CRISPR-Cas Systems. Cell 168, 946–946 e941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova KS, Zhang F, and Koonin EV (2017b). SnapShot: Class 2 CRISPR-Cas Systems. Cell 168, 328–328 e321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marraffini LA (2015). CRISPR-Cas immunity in prokaryotes. Nature 526, 55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marraffini LA, and Sontheimer EJ (2008). CRISPR interference limits horizontal gene transfer in staphylococci by targeting DNA. Science 322, 1843–1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marraffini LA, and Sontheimer EJ (2010). Self versus non-self discrimination during CRISPR RNA-directed immunity. Nature 463, 568–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanraju P, Makarova KS, Zetsche B, Zhang F, Koonin EV, and van der Oost J (2016). Diverse evolutionary roots and mechanistic variations of the CRISPR-Cas systems. Science 353, aad5147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojica FJ, Diez-Villasenor C, Garcia-Martinez J, and Almendros C (2009). Short motif sequences determine the targets of the prokaryotic CRISPR defence system. Microbiology 155, 733–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulepati S, Heroux A, and Bailey S (2014). Structural biology. Crystal structure of a CRISPR RNA-guided surveillance complex bound to a ssDNA target. Science 345, 1479–1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, and Dodson EJ (1997). Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography 53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numata T, Inanaga H, Sato C, and Osawa T (2015). Crystal structure of the Csm3-Csm4 subcomplex in the type III-A CRISPR-Cas interference complex. Journal of molecular biology 427, 259–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osawa T, Inanaga H, Sato C, and Numata T (2015). Crystal structure of the CRISPR-Cas RNA silencing Cmr complex bound to a target analog. Molecular cell 58, 418–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, and Minor W (1997). Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods in enzymology 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KH, An Y, Jung TY, Baek IY, Noh H, Ahn WC, Hebert H, Song JJ, Kim JH, Oh BH, et al. (2017). RNA activation-independent DNA targeting of the Type III CRISPR-Cas system by a Csm complex. EMBO reports 18, 826–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, and Ferrin TE (2004). UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25, 1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyenson NC, Gayvert K, Varble A, Elemento O, and Marraffini LA (2017). Broad Targeting Specificity during Bacterial Type III CRISPR-Cas Immunity Constrains Viral Escape. Cell host & microbe 22, 343–353 e343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyenson NC, and Marraffini LA (2017). Type III CRISPR-Cas systems: when DNA cleavage just isn’t enough. Current opinion in microbiology 37, 150–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohou A, and Grigorieff N (2015). CTFFIND4: Fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J Struct Biol 192, 216–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouillon C, Zhou M, Zhang J, Politis A, Beilsten-Edmands V, Cannone G, Graham S, Robinson CV, Spagnolo L, and White MF (2013). Structure of the CRISPR interference complex CSM reveals key similarities with cascade. Molecular cell 52, 124–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samai P, Pyenson N, Jiang W, Goldberg GW, Hatoum-Aslan A, and Marraffini LA (2015). Co-transcriptional DNA and RNA Cleavage during Type III CRISPR-Cas Immunity. Cell 161, 1164–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres SH (2012). RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J Struct Biol 180, 519–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkunas T, Gasiunas G, Fremaux C, Barrangou R, Horvath P, and Siksnys V (2011). Cas3 is a single-stranded DNA nuclease and ATP-dependent helicase in the CRISPR/Cas immune system. The EMBO journal 30, 1335–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staals RH, Zhu Y, Taylor DW, Kornfeld JE, Sharma K, Barendregt A, Koehorst JJ, Vlot M, Neupane N, Varossieau K, et al. (2014). RNA targeting by the type III-A CRISPR-Cas Csm complex of Thermus thermophilus. Molecular cell 56, 518–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamulaitis G, Kazlauskiene M, Manakova E, Venclovas C, Nwokeoji AO, Dickman MJ, Horvath P, and Siksnys V (2014). Programmable RNA shredding by the type III-A CRISPR-Cas system of Streptococcus thermophilus. Molecular cell 56, 506–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamulaitis G, Venclovas C, and Siksnys V (2017). Type III CRISPR-Cas Immunity: Major Differences Brushed Aside. Trends in microbiology 25, 49–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DW, Zhu Y, Staals RH, Kornfeld JE, Shinkai A, van der Oost J, Nogales E, and Doudna JA (2015). Structural biology. Structures of the CRISPR-Cmr complex reveal mode of RNA target positioning. Science 348, 581–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Oost J, Westra ER, Jackson RN, and Wiedenheft B (2014). Unravelling the structural and mechanistic basis of CRISPR-Cas systems. Nature reviews Microbiology 12, 479–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Mo CY, Wasserman MR, Rostøl JT, Marraffini LA, Liu S (2018) Dynamics of Cas10 Govern Discrimination between Self and Nonself in Type III CRISPR-Cas Immunity. Preprint at bioRxiv 10.1101/369744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra ER, Semenova E, Datsenko KA, Jackson RN, Wiedenheft B, Severinov K, and Brouns SJ (2013). Type I-E CRISPR-cas systems discriminate target from non-target DNA through base pairing-independent PAM recognition. PLoS Genet 9, e1003742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra ER, van Erp PB, Kunne T, Wong SP, Staals RH, Seegers CL, Bollen S, Jore MM, Semenova E, Severinov K, et al. (2012). CRISPR immunity relies on the consecutive binding and degradation of negatively supercoiled invader DNA by Cascade and Cas3. Molecular cell 46, 595–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Luo M, Dolan AE, Liao M, and Ke A (2018). Structure basis for RNA-guided DNA degradation by Cascade and Cas3. Science 361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Luo M, Hayes RP, Kim J, Ng S, Ding F, Liao M, and Ke A (2017). Structure Basis for Directional R-loop Formation and Substrate Handover Mechanisms in Type I CRISPR-Cas System. Cell 170, 48–60 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Sheng G, Wang J, Wang M, Bunkoczi G, Gong W, Wei Z, and Wang Y (2014). Crystal structure of the RNA-guided immune surveillance Cascade complex in Escherichia coli. Nature 515, 147–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng SQ, Palovcak E, Armache JP, Verba KA, Cheng Y, and Agard DA (2017). MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nature methods 14, 331–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement