Abstract

Background:

Individuals with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) demonstrate persistent alterations in walking gait characteristics that contribute to poor long-term outcomes. Higher kinesiophobia, or fear of movement/re-injury, may result in the avoidance of movements that increase loading on the ACLR limb.

Research Question:

Determine the association between kinesiophobia and walking gait characteristics in physically active individuals with ACLR.

Methods:

We enrolled thirty participants with a history of unilateral ACLR (49.35±27.29 months following ACLR) into this cross-sectional study. We used the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK-11) to measure kinesiophobia. We collected walking gait characteristics during a 60-second walking trial, which included gait speed, peak vertical ground reaction force (vGRF), instantaneous vGRF loading rate, peak internal knee extension moment (KEM), and knee flexion excursion. We calculated lower extremity kinetic and kinematic measures on the ACLR limb, and limb symmetry indices between ACLR and contralateral limbs (LSI= [ACLR/contralateral]*100). We used linear regression models to determine the association between TSK-11 score and each walking gait characteristic. We determined the change in R2 (ΔR2) when adding TSK-11 scores into the linear regression model after accounting for demographic covariates (sex, Tegner activity score, graft type, time since reconstruction, history of concomitant meniscal procedure).

Results:

We did not find a significant association between kinesiophobia and self-selected gait speed (ΔR2 0.038, P=0.319). Kinesiophobia demonstrated weak, non-significant associations with kinetic and kinematic outcomes on the ACLR limb and all LSI outcomes (ΔR2 range = 0.001 to 0.098).

Significance:

These data do not support that kinesiophobia is a critical factor contributing to walking gait characteristics in physically active individuals with ACLR.

Keywords: ground reaction force, knee extension moment, knee flexion excursion, limb symmetry index, Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

INTRODUCTION

Individuals with an anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) demonstrate persistent alterations in walking gait characteristics even after completing traditional rehabilitation.1,2 Evidence suggests that walking speed,3,4 alterations in kinetics and kinematics on the ACLR limb,5,6 and inter-limb asymmetries in these outcomes may contribute to poor long-term outcomes following ACLR.7,8 Slower walking speed,3,4 less peak vertical ground reaction force (vGRF),6 and lower vGRF loading rate5 on the ACLR limb during walking associate with deleterious metabolic and compositional joint tissue outcomes hypothesized to contribute to the development of post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis. Individuals with an ACLR that demonstrate greater inter-limb asymmetries during walking, specifically those related to lower peak internal knee extension moments (KEM) and knee flexion on the ACLR limb compared to the contralateral limb, are less likely to pass return-to-sport criteria compared to those with smaller inter-limb asymmetries.7 Identifying factors that associate with persistent alterations in walking gait characteristics may inform the development of novel therapeutic intervention strategies that improve long-term outcomes following ACLR.

Kinesiophobia, or pain-related fear of movement, is a psychological construct that associates with poor short-term outcomes that are frequently documented at the completion of rehabilitation following ACLR.9-12 Increased pain and the sequelae of physical impairments that occur following ACL injury and ACLR may contribute to fear-based avoidance of certain movements in order to reduce the loading applied to the ACLR limb. Consequently, higher levels of kinesiophobia, assessed using the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK-11), are associated with an inability to return to pre-injury levels of physical activity.9-12 Individuals with ACLR who demonstrate higher levels of kinesiophobia likely alter the magnitude and frequency of physical activity to reduce loading on their ACLR limb, yet it remains unknown if kinesiophobia associates with walking gait characteristics that contribute to knee specific loading. If individuals with higher levels of kinesiophobia alter their walking gait characteristics to reduce loading on the ACLR limb, these alterations may contribute to the development of posttraumatic knee osteoarthritis following ACLR. Current rehabilitation strategies do not address psychological impairments following ACLR,9,12 and the management of kinesiophobia for the purpose of optimizing movement profiles following injury may be a novel therapeutic option for improving long-term outcomes following ACLR.

The purpose of this study was to determine the associations between kinesiophobia and walking gait characteristics in physically active individuals with ACLR. Specifically, we separately determined the associations between kinesiophobia and 1) self-selected walking speed, 2) ACLR limb biomechanical outcomes (peak vGRF, instantaneous vGRF loading rate, peak KEM and knee flexion excursion, and 3) limb symmetry indices (LSI) of these biomechanical outcomes (peak vGRF LSI, instantaneous vGRF loading rate LSI, peak KEM LSI and knee flexion excursion LSI). We hypothesized that greater kinesiophobia is associated with unfavorable walking gait characteristics that may contribute to the development of post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis, including slower walking speed, less peak vGRF, vGRF loading rate, peak KEM and knee flexion excursion on the ACLR limb, and lower LSI outcomes in individuals with ACLR.

METHODS

Design

The outcomes assessed in this study were collected during the baseline testing session of a larger trial evaluating lower extremity biomechanical outcomes and blood biomarkers over 4-weeks’ time in individuals with ACLR (NCT03035994). First, participants completed the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK-11) to measure pain-related fear of movement. Next, participants completed a 60-second walking gait assessment on a force-instrumented treadmill to analyze lower extremity biomechanical outcomes of interest (explained in detail below). The university’s Institutional Review Board approved all methods and all participants provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Participants

We enrolled 30 individuals from the university community between 18-35 years of age who underwent a primary, unilateral ACLR using either a patellar tendon or hamstring autograft at least 6 months prior to study enrollment (Table 1). All participants had completed their post-operative rehabilitation and had clearance from their orthopaedic physician to participate in unrestricted physical activity. All participants engaged in at least 30 continuous minutes of physical activity three times per week. We excluded individuals: 1) with a history of musculoskeletal injury to either leg (e.g. ankle sprain, muscle strain) within 6 months prior to participation in the study, 2) with a history of lower extremity surgery other than ACLR, 3) with a history of knee osteoarthritis or current symptoms related to knee osteoarthritis (e.g. pain, swelling, stiffness), 4) who were currently pregnant or planning to become pregnant while enrolled in the study, 5) with a history of cardiovascular restrictions that limited the participant’s ability to participate in any physical activity. Based on previously published data13 we assumed a moderate association (r = 0.518) between each walking gait characteristic and kinesiophobia, which we determined from a previous study evaluating the association between kinesiophobia and trunk kinematics during walking gait in individuals with lateral compartment osteoarthritis following ACLR that governed our sample size of 30 participants (G*Power Statistical Power Analysis Software v3.114).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Sex | |

| Male | 9 (30%) |

| Female | 21 (70%) |

| Age (years) | 20.43±2.91 |

| Height (cm) | 172.70±10.81 |

| Mass (kg) | 73.16±16.10 |

| BMI | 24.52±4.35 |

| Time since Surgery (months) | 49.35±27.29 |

| Graft Type | |

| Hamstring | 16 (53%) |

| Patellar Tendon | 14 (47%) |

| History of Concomitant Meniscal Surgery | |

| Yes | 13 (43%) |

| No | 17 (57%) |

| Pre-Injury Tegner | 8.87±0.76 |

| Current Tegner | 7.47±1.33 |

| Change in Tegner | −1.40±1.35 |

| IKDC | 86.49±9.50 |

| TSK-11 | 21.87±3.29 |

| Gait Speed (m/s) | 1.29±0.12 |

| ACLR Limb Outcomes | |

| Peak vGRF | 1.11±0.06 |

| Instantaneous vGRF loading rate | 132.92±30.74 |

| Peak KEM | −0.05±0.01 |

| Knee Flexion Excursion | 13.49±2.75 |

| LSI Outcomes | |

| Peak vGRF LSI | 98.73±2.62 |

| Instantaneous vGRF loading rate LSI | 99.34±7.40 |

| Peak KEM LSI | 90.37±15.92 |

| Knee Flexion Excursion LSI | 89.56±16.50 |

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and N (%) for categorical variables; BMI = body mass index; IKDC = International Knee Documentation Committee; TSK-11 = Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia; vGRF = ground reaction force; KEM = knee extension moment

Data Elements

Participant Demographics

Participants self-reported age, sex, ACLR graft type, history of concomitant meniscal injury or surgery, and the date of ACLR. We used the subjective portion of the International Knee Documentation Form and the Tegner activity scale to assess self-reported function and level of physical activity, respectively. We measured height and weight in the laboratory prior to testing.

Assessment of Kinesiophobia

We used the shortened version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK-11) to measure pain-related fear of movement/ reinjury, which served as our independent outcome measure of kinesiophobia.15 The TSK-11 is a validated measure of kinesiophobia in individuals with ACLR.16 Response items on the TSK-11 are scored from 1 to 4, and are related to activity avoidance (e.g. I’m afraid I might injury myself if I exercise) and somatic sensations (e.g. Pain always means I have injured my body).9,17 Possible scores on the TSK-11 range from 11 to 44, with higher scores indicating greater pain-related fear of movement/reinjury.15

Lower Extremity Biomechanics

In order to determine self-selected walking speed, participants completed 5 over-ground walking trials and were cued to walk at a comfortable pace through two sets of infrared timing gates as they would “comfortably walk down the sidewalk” (Brower TC-Gate; Brower Timing Systems, Draper, Utah).5,6 We used each participant’s self-selected walking speed to set the speed of the treadmill during the collection of our lower extremity biomechanical outcomes. Participants walked on the treadmill for 5 minutes prior to collection of lower extremity biomechanical outcomes to allow for acclimation to treadmill walking.

We collected kinematics and kinetics during a 60-second trial with a 14-camera motion capture system (Motion Analysis Corporation, Santa Rose, CA) and a dual-belt, force-sensing treadmill (Bertec, Columbus, OH) with two 152 × 50.8 cm force plates (Model S020008). We sampled kinematic data at 100 Hz, and filtered the kinematic data using a 4th order low-pass Butterworth filter with a cut-off frequency of 6 Hz. We sampled kinetic data at 1000 Hz, and filtered the kinetic data using a 4th order low-pass Butterworth filter with a cut-off frequency of 100 Hz. We outfitted participants with 15 anatomical retro-reflective markers on the lower extremities (1st metatarsal, 5th metatarsal, calcaneus, lateral malleolus, lateral epicondyle, anterior superior iliac spine, posterior superior iliac spine, and 2nd sacral vertebrae) with 14 additional tracking markers bilaterally affixed using rigid clusters to the thighs and shanks. A static trial was collected with an additional 4 markers (bilateral medial malleolus, medial epicondyle) to determine knee and ankle joint centers. We calculated hip joint centers from a leg circumduction task.18

We used the static trial and functional hip joint centers to scale a seven segment, 18 degree-of-freedom model of the pelvis and left and right lower extremities.19 We used filtered marker and force data to estimate sagittal plane knee angle (flexion [+]) and internal sagittal plane knee moment (extension [-]) using previously described inverse dynamics calculations.20 We identified kinetic and kinematic outcomes during the first 50% of the stance phase of gait, which we determined as the interval from initial contact (vGRF ≥ 20N) to toe-off (vGRF ≤ 20N) and stride-averaged across the 60-second trial using custom MATLAB routines (Mathworks, Inc, Natick, MA). We calculated instantaneous vGRF loading rate as the first derivative of the force-time curve.5,6 We converted the body mass of each participant to Newtons (N) to normalize peak vGRF (xBW) and instantaneous vGRF loading rate (xBW/seconds). We normalized peak KEM to the product of bodyweight and height (xBW*meters). We calculated knee flexion excursion from sagittal plane knee angle at initial contact to peak knee flexion angle. We calculated limb symmetry indices (LSI = [ACLR limb / contralateral limb] * 100) for each of the lower extremity biomechanical outcomes to determine the magnitude of asymmetry between limbs.

Statistical Analysis

We evaluated walking gait characteristics and TSK-11 scores for statistical outliers, defined as > 3 standard deviations from the mean, using stem and leaf plots. We excluded statistical outliers in a pairwise manner so that a participant was only excluded for that specific analysis; thereby, preserving statistical power for the other analyses. We used separate univariable linear regression models to determine the unique association between TSK-11 score and each walking gait characteristic after accounting for demographic covariates (sex, current Tegner level, graft type, time since reconstruction, history of concomitant meniscal procedure). We also controlled for gait speed in each regression analysis for an ACLR limb or LSI kinetic or kinematic outcome as gait speed influences lower extremity biomechanical outcomes.21 Covariates were first entered into the regression model, followed by TSK-11 score. We determined the change in R2 (ΔR2) and standardized Beta coefficient (β) that TSK-11 score contributed to each walking gait characteristic after accounting for covariates. We completed separate analyses for walking speed, and peak vGRF, vGRF loading rate, knee flexion excursion and peak KEM on the ACLR limb and LSI between limbs. We interpreted associations from the TSK-11 Beta Coefficient as weak (≤ 0.49), moderate (0.5 to 0.69) and strong (≥ 0.7). Significance was set a priori at P ≤ 0.006 for all analyses to account for multiple comparisons (P = 0.05 / 9 comparisons = 0.006). We performed all analyses using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (SPSS, Version 21, IBM Corp., Somers, NY).

RESULTS

We did not identify statistical outliers for any of the main outcome measures, and participant demographics are reported in Table 1. Results for overall regression models are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Regression Results

| Regression Model | Predictor Variables | R | R2 | ΔR2 | ΔR2 P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gait Speed | |||||

| 1 | Covariates | 0.294 | 0.086 | 0.086 | 0.806 |

| 2 | TSK-11 | 0.351 | 0.123 | 0.037 | 0.338 |

| ACLR Limb Outcomes | |||||

| vGRF | |||||

| 1 | Covariates | 0.611 | 0.373 | 0.373 | 0.071 |

| 2 | TSK-11 | 0.686 | 0.47 | 0.098 | 0.057 |

| Instantaneous vGRF Loading Rate | |||||

| 1 | Covariates | 0.604 | 0.365 | 0.365 | 0.08 |

| 2 | TSK-11 | 0.618 | 0.382 | 0.017 | 0.445 |

| Peak KEM | |||||

| 1 | Covariates | 0.513 | 0.263 | 0.263 | 0.269 |

| 2 | TSK-11 | 0.522 | 0.272 | 0.009 | 0.608 |

| Knee Flexion Excursion | |||||

| 1 | Covariates | 0.529 | 0.280 | 0.280 | 0.225 |

| 2 | TSK-11 | 0.529 | 0.280 | <0.001 | 0.961 |

| LSI Outcomes | |||||

| vGRF LSI | |||||

| 1 | Covariates | 0.459 | 0.211 | 0.211 | 0.435 |

| 2 | TSK-11 | 0.485 | 0.235 | 0.024 | 0.415 |

|

Instantaneous vGRF Loading Rate LSI | |||||

| 1 | Covariates | 0.565 | 0.319 | 0.319 | 0.145 |

| 2 | TSK-11 | 0.567 | 0.321 | 0.003 | 0.771 |

| Peak KEM LSI | |||||

| 1 | Covariates | 0.602 | 0.363 | 0.363 | 0.082 |

| 2 | TSK-11 | 0.609 | 0.371 | 0.008 | 0.602 |

| Knee Flexion Excursion LSI | |||||

| 1 | Covariates | 0.399 | 0.159 | 0.159 | 0.634 |

| 2 | TSK-11 | 0.400 | 0.160 | 0.001 | 0.872 |

TSK-11 = Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia; vGRF = ground reaction force; KEM = knee extension moment; ΔR2 =change in R2; Covariates included = sex, Tenger, time since ACLR, graft type, history of concomitant meniscal surgery, gait speed.

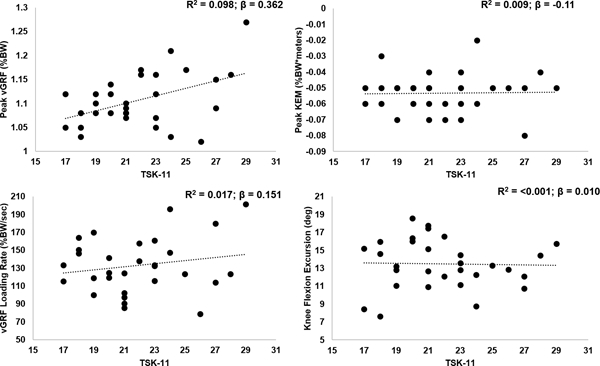

We did not find a significant association between TSK-11 and self-selected walking speed (R2 = 0.037; β = 0.217; P = 0.338; Figure 1) after accounting for covariates. There was a notable albeit weak association between TSK-11 scores and peak vGRF (R2 = 0.098; β = 0.362; P = 0.057; Figure 2). We did not find significant associations between TSK-11 scores with instantaneous vGRF loading rate (R2 = 0.017; β = 0.151; P = 0.445), peak KEM (R2 = 0.009; β = −0.11; P = 0.608), nor knee flexion excursion (R2 = <0.001; β = 0.010; P = 0.961; Figure 2) on the ACLR limb. Similarly, we did not find significant associations between TSK-11 scores with peak vGRF LSI (R2 = 0.024; β = 0.180; P = 0.415), instantaneous vGRF loading rate LSI (R2 = 0.003; β = 0.060; P = 0.771), peak KEM LSI (R2 = 0.008; β = 0.104; P = 0.602), nor knee flexion excursion LSI (R2 = 0.001; β = −0.037; P = 0.872; Figure 3).

Figure 1. Association between Kinesiophobia and Walking Speed.

Gait speed was calculated as meters/second (m/s) and kinesiophobia was assessed via the shortened version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK-11); R2 = coefficient of determination; β = Beta coefficient.

Figure 2. Associations between Kinesiophobia and Gait Characteristics on the ACLR Limb.

Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK-11); R2 = coefficient of determination; β = Beta coefficient; vGRF = vertical ground reaction force; BW = body weight; KEM = knee extension moment; deg = degrees.

Figure 3. Associations between Kinesiophobia and Limb Symmetry Indices.

Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK-11); R2 = coefficient of determination; β = Beta coefficient; LSI = limb symmetry index; vGRF = vertical ground reaction force; KEM = knee extension moment.

DISCUSSION

Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find the association between kinesiophobia with walking gait characteristics to be statistically significant in our cohort of physically active individuals with an ACLR. Specifically, kinesiophobia did not associate with self-selected gait speed nor with peak vGRF, vGRF loading rate, peak KEM, or knee flexion excursion on the ACLR limb. Further, kinesiophobia did not associate with the magnitude of inter-limb asymmetry, quantified as LSI, neither for peak vGRF, vGRF loading rate, peak KEM, nor knee flexion excursion. These results suggest that kinesiophobia was not associated with walking gait characteristics considered relevant to deleterious metabolic and compositional joint tissue outcomes linked to post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis in physically active individuals with ACLR. We interpret these outcomes to suggest that fear of movement or re-injury may not be a critical factor contributing to chronic aberrant walking gait characteristics in individuals with ACLR who are physically active.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the association between kinesiophobia and walking gait characteristics in individuals with ACLR. While kinesiophobia appears to be lower at 12 weeks following ACLR,9 the mean and variability of the TSK-11 score of 21.87±3.29 from our cohort is similar to the mean and variability reported in a previous study12 assessing the associations between kinesiophobia with pain, knee function, and return to physical activity status at 6 and 12 months following ACLR. Therefore, our group did not demonstrate lesser kinesiophobia than would be expected in individuals with ACLR. Additionally, our kinetics and kinematics are similar to previous studies reporting these outcomes in individuals with ACLR.6,22-25 Previous work has demonstrated that additional sagittal plane kinematics during walking gait, beyond the outcomes we assessed in our study, are associated with knee pain and kinesiophobia in individuals with lateral tibiofemoral compartment post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis following ACLR.13 Specifically, individuals with higher kinesiophobia demonstrate greater peak trunk flexion during the stance phase of walking compared to those with lower kinesiophobia.13 The lack of association between kinesiophobia and walking gait characteristics in our study may be due to the duration of time since ACLR and lack of osteoarthritis in our cohort of participants with ACLR. Participants in our cohort were on average 4 years post-ACLR (47.83±26.97 months following ACLR), whereas the cohort of individuals enrolled in the study by Hart and colleagues13 were on average 12 years post-ACLR. Individuals with ACLR who develop lateral tibiofemoral knee osteoarthritis may demonstrated greater pain, which may relate to the higher levels of kineshiophobia in the Hart el al. cohort compared to the cohort of participants included our current study.13

Previous evidence suggests that kinesiophobia influences the magnitude of physical activity that individuals with ACLR elect to participate in within 6-12 months following ACLR.10,12 Ardern et al26 demonstrated that fear of re-injury was the most commonly cited reason for an individual not returning to preinjury levels of sports participation. It is likely that individuals with higher levels of kinesiophobia choose to reduce their exposure to activities that may increase the risk for re-injury, thereby reducing their overall type, magnitude, and frequency of physical activity they participate in.12 In our study, participants were able to self-select their gait speed during the assessment of lower extremity kinetics and kinematics. Our participants likely chose a walking speed, and therefore adopted subsequent lower extremity biomechanical patterns, in which they were most comfortable walking on the treadmill. While the walking speed of our participants is comparable to previous work,5 it differs from other studies reporting gait speed in individuals with ACLR.24 Future studies are needed to determine the associations between walking speed and kinesiophobia in individuals with ACLR who demonstrate various self-selected walking speeds. It is possible that a more physically demanding task would have revealed a more prominent association between joint biomechanics and measures of kinesiophobia. Individuals with ACLR who report higher levels of kinesiophobia at the time of return to physical activity following ACLR (approximately 6 months following ACLR) demonstrate greater asymmetries during single-leg hopping performance than those reporting lower levels of kinesiophobia.9,27 Fear of movement or re-injury has been suggested to be a factor contributing to the adoption of a biomechanical strategy that reduces loading on the ACLR limb when completing discrete, non-repetitive tasks such as single-leg hopping.

Alternatively, differences in the neuronal networks of neurons responsible for governing repetitive, cyclical movements such as walking and non-repetitive movements such as single leg hopping, may have resulted in the null association between kinesiophobia and walking gait characteristics. Steady-state gait is thought to be organized by subcortical networks of neurons responsible for controlling cyclical movements without strong contributions from higher brain centers.28 Therefore, kinesiophobia, a phenomenon that is likely developed by higher brain centers, may be more likely to influence voluntary movements that are organized and executed by cortical neuronal networks. It has been proposed that psychosocial impairments should be addressed during traditional rehabilitation following ACLR,9,12 however the results from our current study suggest that reducing kinesiophobia may not necessarily associate with changes in walking gait characteristics in physically active individuals an average of 4 years following ACLR. Future investigation is warranted to determine if kinesiophobia is associated with kinetic and kinematic outcomes during functional tasks such as jump-landing, which may increase the risk of secondary injury,29 and if reducing kinesiophobia improved kinetic and kinematic outcomes during functional tasks.

The results of our study suggest kinesiophobia does not influence walking gait biomechanics or walking speed in individuals with an ACLR. However, there are limitations to our study that should be considered to better inform future research. Our cohort of individuals with ACLR were on average, fairly symmetrical in our biomechanical LSI outcomes (Table 1). It is possible that kinesiophobia may have a greater influence on inter-limb asymmetries during walking within 6-12 months after ACLR, when inter-limb asymmetries may be greater,5 and when kinesiophobia has been associated with physical activity level. Additionally, the type and duration of post-operative rehabilitation may influence kinesiophobia levels,28 and this should be investigated in future studies. Although our study was thoughtfully designed with an a priori power analysis, our relatively small sample size prohibits the generalization of our results to the greater population of individuals with ACLR. While our study is only generalizable to patients with a TSK-11 score between 17-29, future large scale studies may seek to separately evaluate the association between walking characteristics and kinesiophobia in specific cohorts of individuals with high, moderate, and low levels of kinesiophobia. Additionally, future studies are needed to determine the associations between walking characteristics and kinesiophobia at early time points following ACLR when patients are first attempting to walk without assistive devices. Our participants were required to participate in physical activity at least 3 times per week, and reported participating in relatively high levels of physical activity (mean Tegner = 7.47±1.33). It is important to note, however, that the cohort of individuals with ACLR enrolled into our study did not achieve their pre-injury level of physical activity (mean change in Tegner = −1.40±1.35; Table 1). Future research may seek to determine how changes in physical activity over time may influence the association between kinesiophobia and walking gait characteristics. It remains unknown how our results would translate to the larger population of individuals with ACLR, particularly those opting not to engage in high levels of physical activity. While our sample size was relatively small, the magnitudes of the associations between the TSK-11 score and the gait outcomes that we measured suggest that we would need between 101 and 1073 participants to demonstrate statistically significant associations. Therefore, we do not expect our interpretation is the result of a Type II error, as the associations are all low (Table 2) and would not be practically relevant even if similarly demonstrated in a much larger sample of participants.

In conclusion, we did not find a significant association between the level of kinesiophobia and gait speed, peak vGRF, instantaneous vGRF loading rate, peak KEM nor knee flexion excursion on the ACLR limb or the magnitude of inter-limb asymmetry for these same biomechanical variables compared to the uninjured limb. Therefore, implementing therapeutic interventions that reduce kinesiophobia may not be beneficial for correcting walking gait characteristics that are considered relevant to deleterious metabolic and compositional joint tissue outcomes linked to posttraumatic knee osteoarthritis in physically active individuals with ACLR. Future research is needed to determine additional factors that may influence walking gait characteristics in individuals with an ACLR, and if kinesiophobia associates with more dynamic and/or cortically driven functional movements following ACLR.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Research reported in this manuscript was supported in full by the Junior Faculty Development Award from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT:

None of the authors report any conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hart HF, Culvenor AG, Collins NJ, Ackland DC, Cowan SM, Machotka Z, et al. Knee kinematics and joint moments during gait following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(10):597–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall M, Stevermer CA, Gillette JC. 2012. Gait analysis post anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: knee osteoarthritis perspective. Gait Posture 36(1):56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfeiffer S, Harkey MS, Stanley LE, Blackburn JT, Padua DA, Spang JT, et al. Associations between Slower Walking Speed and T1rho Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Femoral Cartilage following Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017; November [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pietrosimone B, Blackburn JT, Harkey MS, Luc BA, Hackney AC, Padua DA, et al. Walking Speed As a Potential Indicator of Cartilage Breakdown Following Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68:793–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pietrosimone B, Loeser RF, Blackburn JT, Padua DA, Harkey MS, Stanley LE, et al. Biochemical markers of cartilage metabolism are associated with walking biomechanics 6-months following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.J Orthop Res. 2017;35(10):2288–2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pietrosimone B, Blackburn JT, Harkey MS, Luc BA, Hackney AC, Padua DA, et al. Greater Mechanical Loading During Walking Is Associated With Less Collagen Turnover in Individuals With Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. AM J Sports Med. 2016;44:425–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Stasi SL, Logerstedt D, Gardinier ES, Snyder-Mackler L. Gait patterns differ between ACL-reconstructed athletes who pass return-to-sport criteria and those who fail. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:1310–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardinier ES, Di Stasi S, Manal K, Buchanan TS, Snyder-Mackler L. Knee contact force asymmetries in patients who failed return-to-sport readiness criteria 6 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:2917–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chmielewski TL, Zeppieri G, Lentz TA, Tillman SM, Moser MW, Indelicato PA, et al. Longitudinal changes in psychosocial factors and their association with knee pain and function after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Physical Therapy. 2011;91:1355–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kvist J, Ek A, Sporrstedt K, Good L. Fear of re-injury: a hindrance for returning to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Atrhosc. 2005;13:393–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lentz TA, Tillman SM, Indelicato PA, Moser MW, George SZ, Chmielewski TL. Factors associated with function after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Sports Health. 2009;1:47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lentz TA, Zeppieri G Jr, George SZ, Tillman SM, Moser MW, Farmer KW, et al. Comparison of physical impairment, functional, and psychosocial measures based on fear of reinjury/lack of confidence and return-to-sport status after ACL reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:345–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hart HF, Collins NJ, Ackland DC, Cowan SM, Crossley KM. Gait Characteristics of People With Lateral Knee OA After ACL Reconstruction. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(1):2406–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woby SR, Roach NK, Urmston M, Watson PJ. Psychometric properties of the TSK-11: a shortened version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia. Pain. 2005;117:137–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.George SZ, Lentz TA, Zeppieri G, Lee D, Chmielewski TL. Analysis of shortened versions of the tampa scale for kinesiophobia and pain catastrophizing scale for patients after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin J Pain. 2012;28:73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roelofs J, Goubert L, Peters ML, Vlaeyen JW, Crombez G. The Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia: further examination of psychometric properties in patients with chronic low back pain and fibromyalgia. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piazza SJ, Okita N, Cavanagh PR. Accuracy of the functional method of hip joint center location: effects of limited motion and varied implementation. J Biomech. 2001;34:967–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnold EM, Ward SR, Lieber RL, Delp SL. A model of the lower limb for analysis of human movement. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38:269–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silder A, Heiderscheit B, Thelen DG. Active and passive contributions to joint kinetics during walking in older adults. J Biomech. 2008;41:1520–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeni JA Jr, Higginson JS. Differences in gait parameters between healthy subjects and persons with moderate and severe knee osteoarthritis: a result of altered walking speed? Clin Biomech. 2009;24:372–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asaeda M, Deie M, Fujita N, Kono Y, Terai C, Kuwahara W, et al. Gender differences in the restoration of knee joint biomechanics during gait after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee. 2017;24:280–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luc-Harkey BA, Harkey MS, Stanley LE, Blackburn JT, Padua DA, Pietrosimone B. Sagittal plane kinematics predict kinetics during walking gait in individuals with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Biomech. 2016;39:9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milandri G, Posthumus M, Small TJ, et al. Kinematic and kinetic gait deviations in males long after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Biomech. 2017; 49:78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfeiffer SJ, Blackburn JT, Luc-Harkey B, et al. Peak knee biomechanics and limb symmetry following unilateral anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Associations of walking gait and jump-landing outcomes. Clin Biomech. 2018; 53:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Webster KE. Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis including aspects of physical functioning and contextual factors. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:1543–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tengman E, Brax Olofsson L, Nilsson KG, Tegner Y, Lundgren L, Hager CK. Anterior cruciate ligament injury after more than 20 years: I. Physical activity level and knee function. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24:e491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ivanenko YP, Poppele RE, Lacquaniti F. Motor control programs and walking. Neuroscientist. 2006;12:339–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paterno MV, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Rauh MJ, Myer GD, Huang B, et al. Biomechanical measures during landing and postural stability predict second anterior cruciate ligament injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and return to sport. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1968–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]