Abstract

Background

Over 1700 people are diagnosed with laryngeal cancer annually in England. Current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on referral for suspected laryngeal cancer were based on clinical consensus, in the absence of primary care studies.

Aim

To identify and quantify the primary care features of laryngeal cancer.

Design and setting

Matched case–control study of patients aged ≥40 years using data from the UK’s Clinical Practice Research Datalink.

Method

Clinical features of laryngeal cancer with which patients had presented to their GP in the year before diagnosis were identified and their association with cancer was assessed using conditional logistic regression. Positive predictive values (PPVs) for each clinical feature were calculated for the consulting population aged >60 years.

Results

In total, 806 patients diagnosed with laryngeal cancer between 2000 and 2009 were studied, together with 3559 age-, sex-, and practice-matched controls. Ten features were significantly associated with laryngeal cancer: hoarseness odds ratio [OR] 904 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 277 to 2945); sore throat, first attendance OR 6.2 (95% CI = 3.7 to 10); sore throat, re-attendance OR 7.7 (95% CI = 2.6 to 23); dysphagia OR 6.5 (95% CI = 2.7 to 16); otalgia OR 5.0 (95% CI = 1.9 to 13); dyspnoea, re-attendance OR 4.7 (95% CI = 1.9 to 12); mouth symptoms OR 4.7 (95% CI = 1.8 to 12); recurrent chest infection OR 4.5 (95% CI = 2.4 to 8.5); insomnia OR 2.7 (95% CI = 1.3 to 5.6); and raised inflammatory markers OR 2.5 (95% CI = 1.5 to 4.1). All P-values were <0.01. Hoarseness had the highest individual PPV of 2.7%. Symptom combinations currently not included in NICE guidance were sore throat plus either dysphagia, dyspnoea, or otalgia, for which PPVs were >5%.

Conclusion

These results expand current NICE guidance by identifying new symptom combinations that are associated with laryngeal cancer; they may help GPs to select more appropriate patients for referral.

Keywords: cancer, diagnosis, general practice, laryngeal, primary health care

INTRODUCTION

Cancer of the larynx forms part of a group of disparate head and neck (H&N) cancers managed by ear, nose, and throat or oral surgery specialists. In 2016, 1771 people (80% male) were diagnosed with laryngeal cancer in England;1 approximately 65% of male patients survive their disease for ≥5 years.2 The incidence of H&N cancer has increased over the last few decades, rising 31% from the 1993–1995 to 2013–2015 period.3 Tobacco use and exposure, as well as alcohol misuse, are strongly associated with the disease.4,5

Early detection and referral in primary care is crucial to avoid diagnostic delay — one of the main predictors of poor prognosis in laryngeal cancer.6–9 A recent UK study of 28 cancers identified laryngeal cancer as having the fifth-longest primary care interval time (time from diagnosis to referral).10 The lack of specific visible or palpable signs for laryngeal cancer means that GPs must select appropriate patients for referral based on presenting symptoms.

Current guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) suggest urgent referral for suspected laryngeal cancer in patients presenting with persistent unexplained hoarseness or unexplained neck lump.11 However, the lack of primary care evidence meant these recommendations were based on consensus. Secondary care studies have reported hoarseness as the main symptom,8,12,13 but some also report dysphagia,14,15 pain,14,15 neck lump,14,15 wheeze,16 stridor,14 bleeding,14 sore throat,17 otalgia,17 and weight loss.14,15 The varying nature of these symptoms reflects the different anatomical sites of H&N cancers; some of these symptoms may also indicate late presentation of the disease.14 Neck lumps could be indicative of local spread of H&N cancers or other cancers, including lymphoma,18 so patients with neck lumps also are recommended for urgent referral; again this is without contemporary primary care evidence to support the recommendation.11 The only primary care study of laryngeal cancer (excluding other H&N cancers) involved 11 UK practices. In this study clinicians were asked to refer all adults with ≥4 weeks of hoarseness for laryngoscopy: 10 out of 300 (3.3%) individuals were found to have laryngeal cancer (plus two who had bronchial cancer causing a recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy).19

It is unclear which symptoms from the disparate range reported in previous research are associated with laryngeal cancer in primary care. As such, this study aimed to identify and quantify the laryngeal cancer risk for individual and combined clinical features (symptoms, physical signs, and abnormal investigations) of primary care patients.

METHOD

The UK’s Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) contains anonymised patient data from over 600 UK general practices and includes information on symptom reporting, diagnoses, prescriptions, investigations, and referrals. Stringent checks are undertaken to preserve data validation and quality. This study used a matched case–control design of primary care electronic patient records from the CPRD.

How this fits in

The clinical prodrome for laryngeal cancer is unclear. Existing research has focused on investigating symptoms of head and neck cancers collectively. Current guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) suggests considering urgent referral for suspected laryngeal cancer in patients presenting with persistent unexplained hoarseness or unexplained neck lump. Indeed, in this study, hoarseness was the symptom with the highest individual risk of laryngeal cancer, approaching the 3% NICE investigation threshold. Patients reporting combined symptom combinations not identified in current NICE guidance — such as sore throat with dysphagia, with recurrent dyspnoea, or with otalgia — had risk estimates of >5%. These results expand on current cancer guidelines and may improve GPs’ future selection of patients for referral for suspected laryngeal cancer.

Cases and controls

A list of eight laryngeal cancer codes was compiled from the CPRD’s master code library (based on Read codes and available from the authors on request). Cases comprised patients aged ≥40 years diagnosed with laryngeal cancer between January 2000 and December 2009, who had consulted their GP in the previous year. Each case had up to five age-, sex-, and practice-matched controls. The first recorded laryngeal cancer code was considered to be the date of diagnosis (the index date for cases and the matched controls). The following were excluded:

participants who had not consulted in the year before the index date;

cases without controls;

controls with laryngeal cancer; and

controls who had not sought medical care after registration.

Selection of putative clinical variables

Clinical features (symptoms, diseases, and abnormal investigations) linked to laryngeal cancer were identified through literature searches and a study of online patient support groups. The terms ‘cancer of larynx’, ‘laryngeal cancer symptoms’, ‘primary care laryngeal cancer’, and ‘early signs/indications/symptoms of laryngeal cancer’ were searched in EBSCO, Google Scholar, and PubMed.

The CPRD’s code library contains multiple codes associated with individual features; these were collated into feature-specific libraries. Occurrences of clinical features were identified in the year before the index date, with those present in ≥2% of cases being retained.

Occurrences of fractures were used to test for any difference in the rate of recording between cases and controls. Laboratory tests were classified as abnormal if they fell outside of the local laboratory’s normal range. Patients within the normal range were grouped with those who had no test result.

Composite variables

The variables ‘chest infection’, ‘dyspepsia’, ‘mouth symptoms’, and ‘sore throat’ comprised multiple codes:

chest infection contained pleurisy, pneumonia, bronchitis, and lower or upper respiratory tract infections;

dyspepsia included heartburn, indigestion, or reflux;

mouth symptoms comprised sores, ulcers, infection, or oral candidiasis; and

sore throat was made up of pain, tonsillitis, infection, laryngitis, and pharyngitis.

Merging tests together created the following groups:

raised inflammatory markers — contained any elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, plasma viscosity, or C-reactive protein tests;

abnormal liver function tests — comprised any raised value of the hepatic enzymes alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, and bilirubin.

When a feature was found to be significantly associated with laryngeal cancer twice (that is, reported for a second time on a subsequent consultation date), it was referred to as a second attendance. The time frame for counting supplementary symptoms was from 12 months before the cancer diagnosis, up to the date of diagnosis (1 year).

Analysis and statistical methods

Analysis used non-parametric methods as the data were not normally distributed. Testing for associations used univariable and multivariable conditional logistic regression. Variables associated with laryngeal cancer that passed the P-value threshold of ≤0.1 in univariable analysis progressed to multivariable analysis. A final multivariable model was derived from features surviving the previous stages, using a P-value threshold of <0.01. All previous features were checked for inclusion against the final model. Clinically plausible interaction terms were added to the final model and retained if their P-value was also <0.01.

Risk estimates in the form of positive predictive values (PPVs) for single and paired features were calculated for the ≥60 years age group only; this was done using Bayes’ theorem (prior odds of laryngeal cancer multiplied by the likelihood ratio of the feature equals the posterior odds of having laryngeal cancer when having that feature). The age-specific national incidence of laryngeal cancer for 2008 served as the prior odds. PPVs were estimated for consulting patients only; as such, the posterior odds were divided by 0.89, as 342 (11%) of 3072 eligible controls aged ≥60 years were non-consulters. PPVs for those aged <60 years are not shown, as they are based on small numbers.

Power calculation

The study initially involved 813 cases with laryngeal cancer and 4173 controls. In line with previous studies, power calculations were performed instead of sample size calculations;18,20–22 this number provided >95% power (5% two-sided α) to detect a change in a rare variable in 3% of cases and 1% of controls. For a more common variable, the study had >92% power to detect a change in prevalence of 20% in cases and 15% in controls. Data analysis was conducted using Stata (version 15).

RESULTS

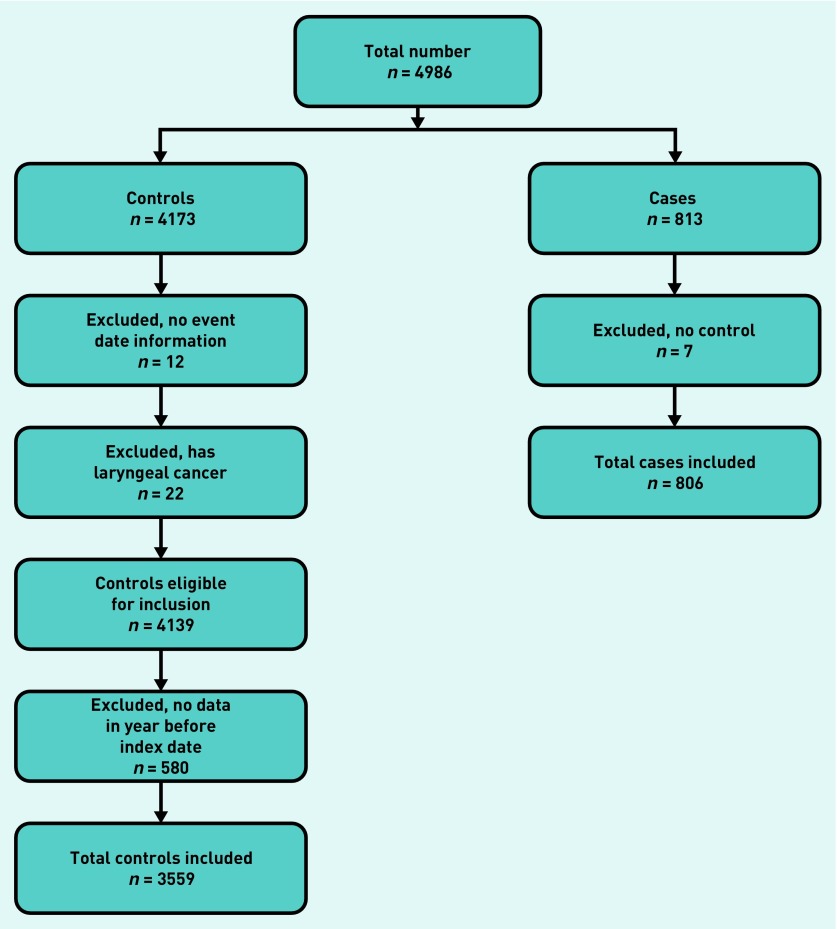

The CPRD provided 4986 patients (813 cases; 4173 controls). Application of the exclusion criteria is shown in Figure 1, leading to a final number of 4365 (806 cases; 3559 controls).

Figure 1.

Application of exclusion criteria.

Patient demographic and consultation details are given in Table 1; patients with laryngeal cancer consulted significantly more frequently than controls in the year before diagnosis (P<0.001, rank sum test).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and consultation rates in the year before diagnosis.

| Cases | Controls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n= 678 | Female, n= 128 | Total, n= 806 | Male, n= 2960 | Female, n= 599 | Total, n= 3559 | |

| Median age, years, at diagnosis (IQR) | 67 (60–74) | 66 (56–78) | 67 (60–75) | 68 (61–75) | 66 (56–77) | 67 (60–75) |

| Median number of consultations (IQR) | 12 (8–19) | 18 (11–27) | 14a(8–20) | 7 (3–13) | 7 (4–14) | 7a (4–13) |

Cases consulted significantly more frequently than controls in the year before diagnosis (P<0.001). IQR = interquartile range.

Clinical features

A total of 34 symptoms and 14 investigations were considered at the start of the study; of these, 10 remained significant in the final model. Their frequencies, univariable likelihood ratios, and multivariable odds ratios (ORs) for the study sample are shown in Table 2. Of the 806 patients, 595 (74%) had at least one of the final-model clinical features from Table 2 recorded in the year before diagnosis. There was no sex interaction but an antagonistic interaction between hoarseness and recurrent chest infection was found (interaction OR 0.026, P<0.005).

Table 2.

Features of laryngeal cancer in patients aged ≥40 years: cases (n = 806) and controls (n = 3559)

| Symptoms | Cases, n (%) | Controls, n (%) | Univariate likelihood ratioa (95% CI) | Multivariate ORb (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hoarseness | 421 (52) | 9 (0.25) | 207 (107 to 398) | 904 (277 to 2945) | <0.001 |

| Sore throat, first attendance | 187 (23) | 81 (2) | 10 (8.0 to 13) | 6.2 (3.7 to 10) | <0.001 |

| Sore throat, second attendance | 84 (10) | 11 (0.3) | 33 (18 to 63) | 7.7 (2.6 to 23) | <0.001 |

| Chest infection, second attendance | 63 (8) | 101 (3) | 2.8 (2.0 to 3.7) | 4.5 (2.4 to 8.5) | <0.001 |

| Dysphagia | 37 (5) | 23 (0.6) | 7.1 (4.3 to 12) | 6.5 (2.7 to 16) | <0.001 |

| Otalgia | 32 (4) | 34 (1) | 4.2 (2.6 to 6.7) | 5.0 (1.9 to 13) | 0.001 |

| Dyspnoea, second attendance | 31 (4) | 53 (1) | 2.6 (1.7 to 4.0) | 4.7 (1.9 to 12) | 0.001 |

| Insomnia | 28 (3) | 59 (2) | 2.1 (1.4 to 3.3) | 2.7 (1.3 to 5.6) | 0.008 |

| Mouth symptoms | 21 (3) | 38 (1) | 2.4 (1.4 to 4.1) | 4.7 (1.8 to 12) | 0.002 |

|

| |||||

| Investigations | |||||

| Raised inflammatory markers | 72 (9) | 155 (4) | 2.1 (1.6 to 2.7) | 2.5 (1.5 to 4.1) | <0.001 |

The univariate likelihood ratio, showing the likelihood of a specific symptom being present in a patient with laryngeal cancer, compared with the likelihood of it being present in a patient without cancer.

Multivariate conditional logistic regression, containing all 10 variables. CI = confidence interval. OR = odds ratio.

There were 191 patients with a code indicating carcinoma in situ. Exclusion of these cases and their controls resulted in three symptoms being less significant in the final model: otalgia (OR 3.0, P = 0.048), insomnia (OR 2.7, P = 0.037), and mouth symptoms (OR 5.1, P = 0.014). The OR for hoarseness increased from 904 to 2314 when those coded as carcinoma in situ were excluded; all other ORs remained largely unchanged.

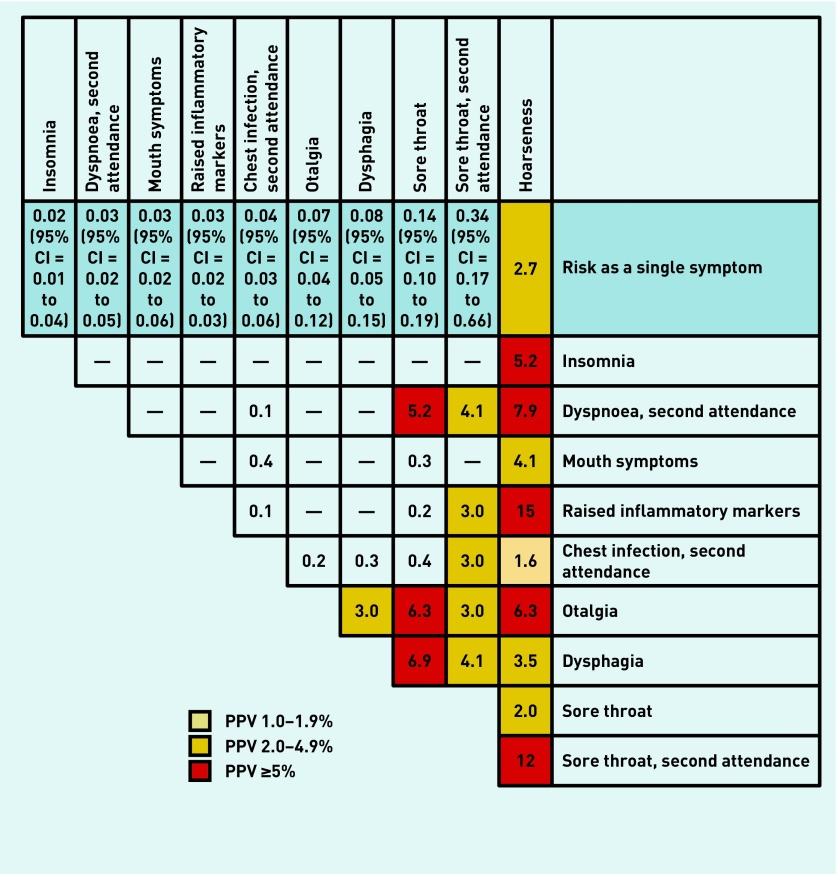

Positive predictive values

The PPVs for single and combined symptoms of laryngeal cancer in patients aged ≥60 years are shown in Figure 2. Hoarseness produced the highest individual risk of laryngeal cancer, with a PPV of 2.7%, thereby approaching NICE’s 3% threshold, at which point an urgent referral is recommended. Reporting more than one symptom in the year before diagnosis raised the risk for certain combinations: hoarseness with raised inflammatory markers (15%), recurrent sore throat (12%), recurrent dyspnoea (7.9%), or otalgia (6.3%). Multiple symptoms that are not currently quoted in NICE guidance also generated PPVs of >3%: sore throat (first and recurrent presentation) with dysphagia (6.9% and 4.1% respectively), otalgia (6.3% and 3%), or recurrent dyspnoea (5.2% and 4.1%). Dysphagia with otalgia produced a PPV of 3%.

Figure 2.

Positive predictive values (%) for laryngeal cancer features in patients aged ≥ 60 years, for single and paired features. Note: PPVs were not calculated if <5 cases had the feature; when <10 patients or controls had the combined features, 95% CIs were omitted. The cells showing the same feature vertically and horizontally represent a second attendance with the same feature.

DISCUSSION

Summary

This study identified the clinical features of laryngeal cancer in primary care and quantified the risk for individual and combined features. Similar to findings in secondary care reports, hoarseness had the highest individual risk of laryngeal cancer, at 2.7%, thereby providing reasonable support for existing NICE recommendations. The risk increases to >3% when hoarseness is supplemented with other symptoms: dysphagia, mouth symptoms, insomnia, otalgia, or recurrent dyspnoea. The highest PPVs are for hoarseness with sore throat (12%) or raised inflammatory markers (15%).

Symptoms such as sore throat produced PPVs of >5% when reported with recurrent dyspnoea, otalgia, or dysphagia. These symptoms do not feature in current NICE guidance and, likewise, their significance as second symptoms (as well as the significance of raised inflammatory markers) is not reflected in NICE guidelines. Unexpectedly, neck lump was not associated with laryngeal cancer.

These results provide new evidence that GPs should consider relevant when ascertaining whether to refer a patient for suspected laryngeal cancer.

Strengths and limitations

This study included more than 800 patients with laryngeal cancer from across the UK, giving ample power and generalisable results. As the CPRD uses primary care data, the results are directly applicable to how future patients should be selected for specialist referral. It is one of the largest medical electronic databases in the world, and its quality, validity, and representativeness has been well documented.23 A further strength is that, through searching online patient forums and existing literature for possible symptoms, it is unlikely that pertinent symptoms were omitted.

The nature of the study meant the researchers were dependent on the quality of GP recording. As multiple codes exist for each symptom, some individual variation in coding across clinicians was to be expected; however, a generic code, such as ‘dyspnoea’, usually accounted for most symptom ‘hits’, with synonyms such as ‘shortness of breath’ very much minority occurrences. One limitation is that some data will have been omitted or written in the free-text section, which is no longer accessible to researchers.24

Patients with laryngeal cancer also consulted more often than controls, so had a greater chance to report symptoms. One study has suggested minor differences between cases and controls in terms of symptom recording.24 For symptoms that are well known to be related to cancer, there is a small bias towards their being recorded in cases when cancer has been diagnosed, thereby slightly elevating measures of association, including PPVs;25 as such, the PPV for hoarseness found in this study may be artefactually slightly too high. Conversely, for symptoms generally not considered to be associated with cancer, the bias is reversed, meaning that PPVs for symptoms considered to be low risk, such as sore throat, may be minor underestimates.25 The protocol used in this study for calculating PPVs is well established.18,20–22

Despite the large size of the study, some symptom combinations were too rare to be studied. In addition, as the data included patients diagnosed with laryngeal cancer between 2000 and 2009, two changes in government policy during that time (NICE’s 2005 Referral Guidelines for Suspected Cancer and the introduction of the Quality and Outcomes Framework in 2004) may have impacted on the number of symptoms investigated. Analysis indicated that a higher percentage of patients with laryngeal cancer diagnosed after June 2005 reported at least one of the clinical features from the authors’ final model, compared with those diagnosed before June 2005 (79% to 69% respectively, χ2 = 10.4, P = 0.001). However, the same increase in symptom recording was seen in controls, meaning that likelihood ratios were, essentially, unchanged.

This study uses data from consulting populations who are, in general, more ill than the general population. As GPs can only select patients for investigation from those who consult, it could be argued that studying the consulting population is, in fact, most relevant for informing clinical practice.

Comparison with existing literature

Patients diagnosed with laryngeal cancer consulted their GP twice as often as controls in the year before diagnosis; this fits with the finding that patients with laryngeal cancer have longer primary care intervals, impacting on timely diagnosis.10 The symptoms of laryngeal cancer reported here may well contribute to this delay as patients and GPs will usually attribute symptoms such as chest infection, sore throat, or hoarseness to benign causes.

The findings presented here support those from secondary care,6,8,9,14,15 with hoarseness being the strongest individual diagnostic risk marker. Hoarseness was also the most common symptom in patients diagnosed with laryngeal cancer — reported by just over half of them — with a PPV approaching the 3% NICE referral threshold. The PPV exceeded 3% for almost all symptom combinations of hoarseness plus a second symptom. The exceptions to this (sore throat and recurrent chest infection) had lower PPVs, supporting the idea of infection causing the hoarseness. However, when hoarseness was combined with a re-attendance for sore throat, the PPV was 12%. Of the remaining symptoms reported in secondary care studies, only dysphagia, otalgia, and sore throat were associated with cancer in the results presented here. The PPVs for these individual symptoms were <0.5%, but rose to ≥3% when combined with hoarseness or sore throat.

Implications for research and practice

Current NICE guidelines suggest referral for hoarseness, although the recommendation is for ‘persistent and unexplained’ hoarseness. Although the authors could not operationalise these terms, the results can help with the clinical management of hoarseness. The PPVs for laryngeal cancer were lower when hoarseness was supplemented by chest infection or a sore throat, reflecting likely infection, but rose considerably when the apparent infection did not resolve. As such, it seems reasonable for clinicians to treat hoarseness supplemented by other features of infection, but to encourage re-attendance should the hoarseness persist. This is normal practice at present, but now has an evidence base. The same principle applies to raised inflammatory markers in combination with hoarseness: expectant management is still appropriate, with repeat blood tests to be arranged if the symptoms persist.

Conversely, the authors found no association between neck lumps and laryngeal cancer; this could reflect the rarity of laryngeal cancer presenting with regional spread. However, unexplained neck masses are high-risk symptoms for lymphoma,11,26 and warrant referral on that basis.

Other symptoms were associated with laryngeal cancer, but were only high risk when other, specific, symptoms were also present; as an example, sore throat when supplemented by otalgia, dysphagia, or recurrent dyspnoea was found to be high risk. Sore throat and otalgia is extremely common in children; in adults, however, it is much less so. The clinician should, at least, consider the possibility of laryngeal cancer if sore throat and otalgia occur together in an adult. Urgent referral for this symptom combination appears excessive as a brief period of watchful waiting would allow infections to settle but, clearly, it does warrant vigilant follow-up. Dysphagia warrants urgent investigation for possible oesophageal cancer;27 if investigation for oesophageal cancer is negative, and dysphagia is supplemented by sore throat, the possibility of laryngeal cancer should be considered.

This study has resulted in an evidence base for the identification of possible laryngeal cancer in primary care patients who are symptomatic. This evidence supports some of the recommendations in current NICE guidance, particularly relating to hoarseness. It refutes the recommendation for neck lumps, though the clinician must still consider lymphoma. It adds some new symptom combinations: sore throat supplemented by otalgia, dyspnoea, or dysphagia. However, selection of patients for investigation is not simply a matter of totting up symptoms and PPVs. Clinical experience — although almost impossible to measure — adds to skilful decision making.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), through the NIHR Policy Research Unit in Cancer Awareness, Screening, and Early Diagnosis and the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research (grant reference number: RP-PG-0608-10045). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care, other government departments, or arm’s-length bodies.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the Independent Scientific Advisory Committee: protocol 09-110.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

William Hamilton was clinical lead on the 2015 revision of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on the investigation of suspected cancer. His contribution to this article is in a personal capacity, and does not represent the view of the guideline development group, or of NICE itself. Molly Parkinson and Elizabeth Shephard have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Office for National Statistics. Cancer registration statistics England. 2018. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/datasets/cancerregistrationstatisticscancerregistrationstatisticsengland (accessed 7 Jan 2018)

- 2.Cancer Research UK One-, five- and ten- year survival for head and neck cancers. 2018. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/head-and-neck-cancers/survival#heading-Zero (accessed 14 Dec 2018)

- 3.Cancer Research UK Head and neck cancers incidence statistics. 2018. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/head-and-neck-cancers/incidence#heading-Four (accessed 14 Dec 2018)

- 4.Cancer Research UK Head and neck cancers mortality. 2018. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/head-and-neck-cancers#heading-One (accessed 14 Dec 2018)

- 5.Decker J, Goldstein JC. Risk factors in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 1982;306(19):1151–1155. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198205133061905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alho OP, Teppo H, Mäntyselkä P, Kantola S. Head and neck cancer in primary care: presenting symptoms and the effect of delayed diagnosis of cancer cases. CMAJ. 2006;174(6):779–784. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coca-Pelaz A, Takes RP, Hutcheson K, et al. Head and neck cancer: a review of the impact of treatment delay on outcome. Adv Ther. 2018;35(2):153–160. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0663-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raitiola H, Pukander J. Symptoms of laryngeal carcinoma and their prognostic significance. Acta Oncol. 2000;39(2):213–216. doi: 10.1080/028418600430798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teppo H, Alho OP. Comorbidity and diagnostic delay in cancer of the larynx, tongue and pharynx. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(8):692–695. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyratzopoulos G, Saunders CL, Abel GA, et al. The relative length of the patient and the primary care interval in patients with 28 common and rarer cancers. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(Suppl 1):S35–S40. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. London: NICE; 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG12 (accessed 14 Dec 2018) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Queenan JA, Gottlieb BH, Feldman-Stewart D, et al. Symptom appraisal, help seeking, and lay consultancy for symptoms of head and neck cancer. Psychooncology. 2018;27(1):286–294. doi: 10.1002/pon.4458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothman KJ, Cann CI, Flanders D, Fried MP. Epidemiology of laryngeal cancer. Epidemiol Rev. 1980;2:195–209. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolan RW, Vaughan CW, Fuleihan N. Symptoms in early head and neck cancer: an inadequate indicator. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;119(5):463–467. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(98)70102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Douglas CM, Ingarfield K, McMahon AD, et al. Presenting symptoms and long-term survival in head and neck cancer. Clin Otolaryngol. 2018;43(3):795–804. doi: 10.1111/coa.13053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehanna H, Paleri V, West CML, Nutting C. Head and neck cancer — part 1: epidemiology, presentation, and prevention. BMJ. 2010;341:c4684. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vokes EE, Weichselbaum RR, Lippman SM, Hong WK. Head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(3):184–194. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301213280306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shephard EA, Neal RD, Rose PW, et al. Quantifying the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in symptomatic primary care patients aged ≥40 years: a large case–control study using electronic records. Br J Gen Pract. 2015. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Hoare TJ, Thomson HG, Proops DW. Detection of laryngeal cancer: the case for early specialist assessment. JR Soc Med. 1993;86(7):390–392. doi: 10.1177/014107689308600707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shephard EA, Hamilton WT. Selection of men for investigation of possible testicular cancer in primary care: a large case–control study using electronic patient records. Br J Gen Pract. 2018. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Shephard EA, Neal RD, Rose P, et al. Quantifying the risk of multiple myeloma from symptoms reported in primary care patients: a large case-control study using electronic records. Br J Gen Pract. 2015. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Stapley S, Peters TJ, Neal RD, et al. The risk of pancreatic cancer in symptomatic patients in primary care: a large case–control study using electronic records. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(12):1940–1944. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herrett E, Gallagher AM, Bhaskaran K, et al. Data resource profile: Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(3):827–836. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Price SJ, Stapley SA, Shephard E, et al. Is omission of free text records a possible source of data loss and bias in Clinical Practice Research Datalink studies? A case–control study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011664. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Price SJ, Stapley SA, Shephard E, et al. Is omission of free text records a possible source of data loss and bias in Clinical Practice Research Datalink studies? A case–control study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011664. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shephard EA, Neal RD, Rose PW, et al. Quantifying the risk of Hodgkin lymphoma in symptomatic primary care patients aged ≥40 years: a case–control study using electronic records. Br J Gen Pract. 2015. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Stapley S, Peters TJ, Neal RD, et al. The risk of oesophago-gastric cancer in symptomatic patients in primary care: a large case-control study using electronic records. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(1):25–31. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]