Abstract

Drug abuse remains a serious public health issue, underscoring the need for additional treatment options. Agonists at serotonin (5-HT)2C receptors, particularly lorcaserin, are being considered as pharmacotherapies for abuse of a variety of drugs, including cocaine and opioids. The current study compared the capacity of lorcaserin to attenuate reinstatement of extinguished responding previously maintained by either cocaine or an opioid; this type of procedure is thought to model an important aspect of drug abuse, relapse. Five rhesus monkeys responded under a fixed-ratio schedule for cocaine (0.032 mg/kg/infusion) or remifentanil (0.00032 mg/kg/infusion). Reinstatement of extinguished responding was examined following administration of noncontingent infusions of cocaine (0.32 mg/kg) or heroin (0.0032–0.1 mg/kg) combined with response-contingent presentations of the drug-associated stimuli, or heroin alone without presentation of drug-associated stimuli. When combined with drug-associated stimuli, cocaine and heroin increased extinguished responding. On average, monkeys emitted fewer reinstated responses following 0.32 mg/kg cocaine, as compared with the number of responses emitted when cocaine was available for self-administration or when extinguished responding was reinstated by 0.032 mg/kg heroin. When drug-associated stimuli were not presented, heroin did not increase responding. Lorcaserin dose dependently attenuated reinstated responding, and its potency was similar regardless of whether cocaine or heroin was given before reinstatement sessions. The generality of this effect of lorcaserin across pharmacological classes of abused drugs might make it particularly useful for reducing relapse-related behaviors in polydrug abusers.

Keywords: reinstatement of responding, lorcaserin, cocaine, opioid, monkey

In 2016, an estimated 20.1 million Americans met the criteria for having substance use disorder, with about 30% abusing an illicit drug (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2017). The availability of additional pharmacotherapies could increase the number of people in treatment as well as the number of successful outcomes, particularly for abusers of drugs like cocaine for which there is no currently approved pharmacotherapy. Because many drugs of abuse increase extracellular dopamine, one strategy for treating abuse is to decrease dopamine neurotransmission, and agonists acting at serotonin (5-HT)2C receptors indirectly inhibit dopamine release (Howell & Cunningham, 2015; Manvich, Kimmel, & Howell, 2012). The 5-HT2C receptor agonist lorcaserin (Belviq®) is approved for use in humans and is currently being evaluated for the treatment of drug abuse. Lorcaserin is at least 18-fold more selective for 5-HT2C receptors than for any other 5-HT receptors or monoamine transporters (Thomsen et al., 2008), and its therapeutic effects (e.g., decreases food intake and body weight; Aronne et al., 2014; Chan et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2009, 2010) occur at doses that do not appear to produce adverse effects associated with other 5-HT2 receptors (e.g. heart valve disease, drug abuse; Weissman et al., 2013; Shram et al., 2011). With this profile of effects, lorcaserin has become an attractive option for smoking cessation because it reduces smoking and prevents weight gain that commonly occurs when people quit (Hurt et al., 2017; Shanahan, Rose, Glicklich, Stubbe, & Sanchez-Kam, 2017); these effects were predicted by preclinical studies in which lorcaserin decreased nicotine self-administration and responding for food (Levin et al., 2011; Higgins et al., 2012, 2013).

The utility of lorcaserin for treating abuse of drugs other than nicotine is less clear. When given acutely or repeatedly, lorcaserin attenuates cocaine self-administration (Collins, Gerak, Javors, & France, 2016; Gannon, Sulima, Rice, & Collins, 2017; Gerak, Collins, & France, 2016; Harvey-Lewis, Li, Higgins, & Fletcher, 2016), suggesting that it might be beneficial for treating cocaine abuse; however, this effect alone does not necessarily predict its therapeutic usefulness, and other preclinical results are less promising (for review see Collins, Gerak, & France, 2017). For example, in monkeys choosing between cocaine and food, drugs that decrease choice of cocaine have more favorable outcomes in clinical trials, and lorcaserin, administered acutely or repeatedly, does not reduce cocaine choice (Banks & Negus, 2017) and therefore might not selectively reduce cocaine self-administration, although comparing responding maintained by cocaine to that maintained by food might not be ideal. Because the effects of lorcaserin on responding for cocaine and food are likely mediated by the same receptors (5-HT2C), it is not surprising that there is an overall decrease in response rates rather than a shift in preference for food over cocaine following lorcaserin administration (Banks & Negus, 2017). Importantly, other behaviors, such as locomotor activity, are not altered by the same doses of lorcaserin (Collins et al., 2016), suggesting that the effects of lorcaserin on cocaine-and food-maintained responding are not due to a general disruption in behavior.

Effective treatment of drug abuse involves more than simply reducing ongoing drug taking; a therapeutic should also prevent relapse. Given the prevalence of polydrug abuse in general and the frequency of coabuse of opioids and stimulants in particular (e.g., 80% of patients entering treatment used both opioids and stimulants in the 30 days prior to admission; Lauritzen & Nordfjaern, 2018), the most effective approach would decrease the likelihood of relapse to drugs from multiple pharmacological classes. Lorcaserin should prevent relapse because abused drugs, including cocaine and opioids, can increase extracellular dopamine (Di Chiara & Imperato, 1988; Shaham & Stewart, 1996; Tanda, Pontieri, & Di Chiara, 1997) and lorcaserin decreases dopamine neurotransmission. In preclinical studies, aspects of relapse can be modeled using a procedure in which responding previously maintained by drug is reinstated by noncontingent drug along with presentation of drug-associated stimuli, and under those conditions, lorcaserin attenuates responding reinstated by cocaine (Collins et al., 2016; Gerak et al., 2016). In the current study, a similar reinstatement procedure was used to examine the selectivity of lorcaserin by comparing responding that was reinstated by cocaine to that reinstated by heroin.

Method

Subjects

Three adult male rhesus monkeys (MU, CH, NA) weighed between 8.5 and 12.5 kg and three adult female rhesus monkeys (DAI, DAH, GA) weighed between 7 and 11 kg during these studies; dose-effect curves were generated in four or five of the six monkeys such that the animals that contributed to these data varied across tests. Weights were maintained by primate chow (Harlan Teklad, High Protein Monkey Diet, Madison, WI, USA), fresh fruit, and peanuts that were provided daily after experimental sessions; monkeys were housed individually and had free access to water in the home cage. Five of the six monkeys had participated in studies involving reinstatement of responding maintained by cocaine (e.g. Gerak et al., 2016); the sixth monkey (NA) had a history of responding for food. The colony room was maintained on a 14-h light and 10-h dark cycle. Monkeys were maintained, and all experiments were performed, in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th edition (2011).

Surgery

Catheters were implanted in veins (e.g. jugular or femoral) using methods that have been described previously (Collins et al., 2016; Gerak et al., 2016). Initially, sedation was achieved with 10 mg/kg ketamine (s.c.; Henry Schein, Dublin, OH, USA), after which monkeys were intubated and maintained on 2 l/min oxygen and isoflurane anesthesia (Butler Animal Health Supply, Grand Prairie, TX, USA). Once the polyurethane catheter (SIMS Deltec Inc., St. Paul, MN, USA) was placed in a vein, it was tunneled s.c. to the back and connected to a vascular access port (Access Technologies, Skokie, IL, USA). Penicillin B&G (40,000 IU/kg) and meloxicam (0.1–0.2 mg/kg) were given postoperatively.

Apparatus

Experimental sessions were conducted in ventilated, sound-attenuating chambers that contained custom-built response panels with stimulus lights and two response levers. After monkeys were seated in commercially available chairs (Model R001; Primate Products, Miami, FL, USA), vascular access ports were connected to 30-ml or 60-ml syringes (depending on the size of the monkey) using 20-g Huber-point needles (Access Technologies) and 185-cm extension sets (Abbott Laboratories, Stone Mountain, GA, USA). Syringes were placed in syringe drivers (Razel Scientific Instruments Inc., Stamford, CT, USA) located outside the chamber. A computer using Med-PC IV software (Med Associates Inc., St. Albans, VT, USA) controlled experimental events and recorded data.

Procedure

Each monkey received an s.c. injection of saline or lorcaserin (0.1–1 mg/kg) 15 min before every session and participated in three distinct types of sessions. During baseline self-administration sessions, which lasted 90 min, monkeys responded for drug under a fixed ratio (FR) 30:timeout (TO) 180-sec schedule of reinforcement. The syringe pump was activated at the start of the session to fill the catheter with the solution that would be delivered following completion of each FR. The red light above the active lever was illuminated one minute after the start of the loading infusion and a noncontingent priming infusion was delivered; the dose of this infusion was the same as the dose available for self administration during the session (i.e. 0.032 mg/kg/infusion cocaine or 0.00032 mg/kg/infusion remifentanil) and the infusion duration ranged from 15 to 23 sec, depending on the weight of the monkey. The stimulus associated with drug delivery (red light) was extinguished after 5 sec; once the entire priming infusion was delivered, the green light was illuminated. In the presence of the green light, 30 responses on the active lever resulted in the delivery of drug, a 5-sec presentation of the drug-associated stimulus, and the initiation of a 180-sec timeout, during which the chamber was dark and responses were recorded but had no scheduled consequence. At the end of the timeout, the green light was again illuminated and monkeys could respond for another infusion of drug. The active lever was the left lever for four monkeys and the right lever for two monkeys; responses on the inactive lever were recorded but had no scheduled consequence. Baseline self-administration sessions were conducted until stability criteria were satisfied, defined as ≤20% difference in number of responses across the last three baseline sessions with no increasing or decreasing trend during those sessions.

When these criteria were satisfied, extinction sessions were conducted. Like baseline self-administration sessions, extinction sessions began with activation of the syringe pump, which filled the catheter with saline, and lasted 90 min; responding was recorded, although no drug-associated stimuli were presented and no contingent or noncontingent infusion was delivered at any time during the session. Extinction conditions remained in place until the extinction criterion was satisfied, defined as a decrease in the total number of responses to <10% of the number of drug-reinforced responses that was observed during the previous baseline period. Initially each extinction period also lasted for a minimum of three sessions.

Once the extinction criterion was satisfied, a reinstatement session was conducted. Immediately before the 90-min session, saline, cocaine, or heroin was injected into the vascular access port, and the port was then connected to the syringe located in the syringe pump. Like baseline self-administration sessions, reinstatement sessions began with activation of the pump, which delivered the solution placed in the port before the session and then filled the catheter with saline. Drug-associated stimuli were presented for some reinstatement sessions, which were identical to baseline sessions except that the syringe pump was not activated for the remainder of the 90-min session; these sessions were preceded by delivery of noncontingent saline (i.e. responding induced by stimuli only) or drug (i.e. responding induced by drug and stimuli together). During sessions, the green light was illuminated and monkeys could respond under an FR30 schedule for 5-sec presentation of the red light followed by a 180-sec timeout. Drug-associated stimuli were not presented for other reinstatement sessions, which were identical to extinction sessions; stimulus lights were not presented and the syringe pump was not activated after the delivery of noncontingent heroin at the beginning of the session (i.e. responding induced by heroin only). After a single reinstatement session, baseline self-administration conditions were again introduced (FR30:TO 180-sec) until stability criteria were met.

In a previous study (Gerak et al., 2016), the effects of i.g. administration of lorcaserin on responding reinstated by cocaine was examined using a 7-day reinstatement procedure (3 days of self-administration of 0.032 mg/kg/infusion cocaine, 3 days of extinction, and 1 day of reinstatement). In the current study, the potency of lorcaserin administered s.c. was determined using the same procedure. Once the extinction criterion was satisfied, one reinstatement session was conducted with either saline or a single dose of lorcaserin (0.1–1 mg/kg) given s.c. 15 min before sessions in which 0.32 mg/kg cocaine was given noncontingently at the start of the session and cocaine-associated stimuli were presented throughout the session; the dose of cocaine was selected because it is the smallest dose that maximally increased the number of responses during reinstatement tests (Gerak et al., 2016).

Because responding was remarkably stable across baseline sessions and across extinction sessions, the procedure was changed to reduce the number of days between reinstatement tests. Under these new conditions, the type of session changed as long as stability or extinction criteria were satisfied during a single session. The stability criteria for baseline self-administration and extinction were still based on the mean of the last three baseline sessions, although extinction and reinstatement sessions were conducted in between the baseline sessions used to determine the 3-session mean. Reinstatement tests, which were identical to those described above (i.e., 0.32 mg/kg cocaine given noncontingently at the start of the session and cocaine-associated stimuli presented throughout the session), could be conducted as frequently as every 3 days, although sometimes additional baseline or extinction sessions were needed for monkeys to satisfy the stability criteria. Several experiments were conducted to determine whether this procedural change altered responding. First, stability of responding across reinstatement tests was determined by conducting a minimum of five reinstatement tests, with saline given 15 min before each session; reinstated responding was considered stable when it did not vary by more than 20% of the mean of the last three reinstatement tests. Thereafter, a lorcaserin dose-effect curve was generated and results compared with those obtained using the longer procedure. On separate occasions, saline or a single dose of lorcaserin (0.1–1 mg/kg) was given s.c. 15 min before a reinstatement session in which 0.32 mg/kg cocaine was given noncontingently and cocaine-associated stimuli were presented throughout the session.

The generality of the effects of lorcaserin was examined by comparing responding that was reinstated by cocaine to that reinstated by heroin using the 3-day reinstatement procedure. Sessions were identical to those described above for cocaine with two exceptions: during self-administration sessions, completion of the response requirement resulted in an infusion of 0.00032 mg/kg remifentanil instead of cocaine, and for reinstatement tests, either saline or heroin was given noncontingently at the beginning of the session. Pharmacokinetics were the primary factors in selecting the opioids for each type of session; remifentanil has a very short duration of action so accumulation across a self-administration session is minimal whereas heroin has a longer duration of action and its effects would be expected to last for the entire reinstatement session. Both drugs are agonists at µ opioid receptors and both are readily self-administered by monkeys. Dose-effect curves for heroin were generated under conditions in which responding resulted in presentation of remifentanil-associated stimuli (i.e. responding induced by heroin and stimuli together) as well as when the presentation of these stimuli were omitted (i.e. responding induced by heroin only). Because 0.032 mg/kg was the smallest dose of heroin to reinstate responding for remifentanil-associated stimuli (i.e. number of responses during the reinstatement session was within 20% of the mean number of responses reinforced by remifentanil), this dose of heroin was used to evaluate the effects of lorcaserin (15-min pretreatment with 0.032–1 mg/kg; s.c.) on the reinstatement of responding previously reinforced by remifentanil.

Drugs

Cocaine HCl, remifentanil HCl and heroin HCl were generously provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Supply Program (Bethesda, MD, USA). Lorcaserin HCl was purchased from MedChem Express (Princeton, NJ, USA). All drugs were dissolved in sterile saline. During self-administration sessions, cocaine and remifentanil were self-administered i.v. in a volume of 0.1 ml/kg. Lorcaserin was administered s.c. 15 min before reinstatement sessions in a volume of 0.1 ml/kg, and noncontingent cocaine and heroin were given at the start of reinstatement sessions in a volume that ranged from 0.18–0.5 ml.

Data Analysis

For self-administration and reinstatement sessions, the number of responses that occurred in the presence of the green stimulus lights (i.e., responses that were reinforced by delivery of drug and/or presentation of drug-associated stimuli) are plotted as a function of dose or session. In contrast, when visual stimuli were not presented (i.e., extinction sessions and reinstatement sessions in which the effects of noncontingent heroin alone were determined), data represent the total number of responses on the lever that was previously associated with drug throughout the entire 90-min session. To compare the relative potency and effectiveness of lorcaserin across procedures (7-day vs 3-day), data were analyzed using a two-factor repeated measures ANOVA followed by post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests; only doses of lorcaserin that were studied under both conditions were included in the analysis. One monkey (DAI) was replaced (NA) to examine the effects of lorcaserin on heroin-primed reinstatement; consequently, the relative potency and effectiveness of lorcaserin across drug primes (cocaine vs heroin) were analyzed using two different statistical approaches. For the four monkeys that received lorcaserin with both cocaine and heroin, data following administration of saline or lorcaserin (0.1–1 mg/kg) were analyzed using a two-factor repeated measures ANOVA followed by post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests; only doses of lorcaserin that were studied under both conditions were included in this analysis. In addition, two separate one-factor repeated measures ANOVAs were used to determine whether lorcaserin decreased responding for each drug prime followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests. Responding across the different sessions (e.g., baseline, extinction, reinstatement with remifentanil-associated stimuli alone and in combination with heroin administered noncontingently) was compared using one-factor repeated measures ANOVA with the factor being type of session followed by post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests. For reinstatement sessions during which no stimuli were presented (i.e., heroin alone was administered noncontingently), a separate one-factor repeated measures ANOVA with the factor being type of session was conducted followed by post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests.

Results

Initially, a minimum of three baseline and three extinction sessions was conducted before each reinstatement test. During baseline sessions, 0.032 mg/kg/infusion cocaine was available for self-administration, and the mean number of reinforced responses (± 1 SEM) was 755 ± 39, whereas during the 90-min extinction sessions, the mean number of responses (± 1 SEM) on the active lever was 9.7 ± 5.6 (data not shown). When 0.32 mg/kg cocaine was administered noncontingently prior to sessions in which responding resulted in the presentation of the cocaine-associated stimuli, the mean number of responses (± 1 SEM) was 582 ± 54 (circle above S, figure1). On average, reinstated responses were similar regardless of the number of sessions between reinstatement tests, and the effects of lorcaserin were not altered by the procedural changes with 1 mg/kg lorcaserin significantly decreasing the number of responses under both procedures (compare circles and triangles, figure1). Although both procedures showed a main effect of lorcaserin dose (F[4,16]=22.01; P<0.0001), there was no main effect of number of sessions (F[1,4]=0.10; P=0.77) and no interaction between lorcaserin dose and the number of baseline and extinction sessions that preceded each reinstatement test (F[4,16]=2.25; P=0.11).

Figure 1.

Effects of lorcaserin on the reinstatement of responding previously maintained by cocaine. The mean (± 1 SEM) number of responses were determined across five monkeys (circles, triangles) during reinstatement sessions in which they received a noncontingent injection of 0.32 mg/kg cocaine at the start of the session and presentation of cocaine-associated stimuli throughout the session. Initially, a minimum of three baseline and three extinction sessions were conducted before each reinstatement test (circles), after which the procedure was changed such that a minimum of one baseline and one extinction session was conducted before each reinstatement test (triangles). Two-factor repeated-measures ANOVA were used to detect significant differences across treatments and lorcaserin dose; filled symbols (P<0.05) indicate doses of lorcaserin that significantly decreased restatement of responding compared with the effects of saline. Ordinate: number of responses in 90-min reinstatement sessions. Abscissa: dose (mg/kg) lorcaserin given s.c.

Decreasing the minimum number of baseline and extinction sessions before reinstatement tests did not significantly alter responding. With a few exceptions in monkey DAI, only one session was needed to satisfy the stability criteria during baseline (circles, figure 2) and extinction sessions (squares, figure 2). For three of the five monkeys, responding that was reinstated by noncontingent administration of 0.32 mg/kg cocaine along with presentation of cocaine-associated stimuli was considered stable after the minimum number of five reinstatement sessions, whereas the other two monkeys required six sessions (triangles, figure 2). In monkeys MU and GA, a similar number of responses was emitted during cocaine self-administration and reinstatement sessions although DAI, DAH, and CH emitted fewer responses during reinstatement tests. Given that the minimum number of sessions between reinstatement tests did not impact responding, the remaining studies were conducted using the 3-day reinstatement procedure.

Figure 2.

Number of responses during baseline, extinction, and reinstatement sessions when the minimum number of sessions between reinstatement tests was two. Circles show the number of responses during baseline sessions in which monkeys responded for 0.032 mg/kg/infusion cocaine, squares show the number of responses under extinction conditions, and triangles show the number of responses reinstated by a noncontingent injection of 0.32 mg/kg cocaine given at the beginning of the session and cocaine-associated stimuli presented throughout the session. Data to the left of the vertical line are results obtained using the 7-day procedure and data to the right of the line are results obtained using the 3-day procedure until stability criteria were satisfied. The upper gray bar represents ± 20% of the mean number of responses emitted during baseline sessions and the lower gray line indicates 10% of that mean. Ordinate: number of responses in 90-min sessions. Abscissa: consecutive sessions.

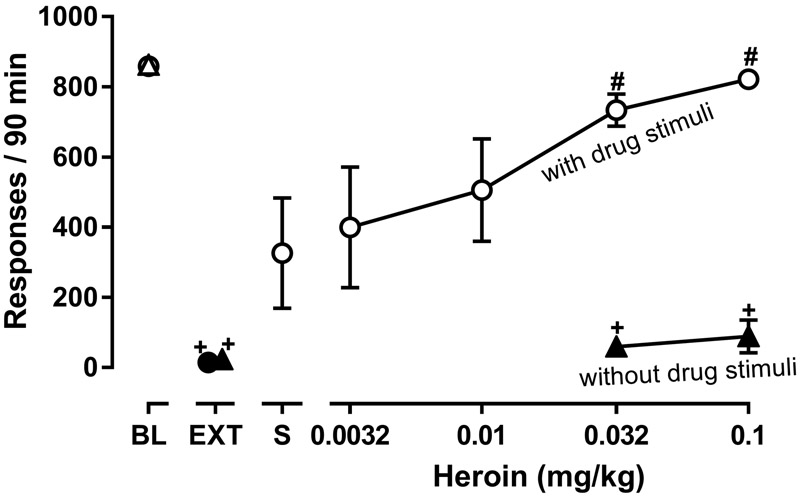

To compare the relative potency and effectiveness of lorcaserin to attenuate responding that was reinstated by drugs from different pharmacological classes, cocaine was replaced by 0.00032 mg/kg/infusion remifentanil during baseline sessions and by heroin during reinstatement sessions. During 90-min baseline sessions in five monkeys, the mean number of responses (± 1 SEM) maintained by remifentanil was 859 ± 12, and under extinction conditions, monkeys emitted 14 ± 7 responses (points above BL and EXT, respectively, figure 3). Reintroduction of the remifentanil-associated stimuli, along with noncontingent administration of saline at the start of the session (i.e. responding induced by drug-associated stimuli only), increased extinguished responding, resulting in 326 ± 158 responses (triangle above S, figure 3). Although all monkeys responded more during these reinstatement sessions, compared with extinction sessions, responding was only modestly increased in three of the five monkeys (i.e. ≤120 responses in a 90-min session; monkeys DAH, CH, NA), whereas responding was similar to baseline self-administration sessions in one monkey (840 responses; monkey MU) and was intermediate in one monkey (547 responses; monkey GA). The type of session significantly impacted responding (F[1.123, 4.49]=14.85; P=0.014); the number of responses emitted during extinction was significantly lower than the number of responses emitted during remifentanil self-administration sessions, although responding during reinstatement sessions (i.e. responding induced by drug-associated stimuli only) was not significantly different from responding during baseline or extinction sessions.. Noncontingent administration of heroin dose dependently reinstated responding only when drug-associated stimuli were also presented. As compared with responding during extinction, responding was significantly increased during reinstatement sessions in which either 0.032 or 0.1 mg/kg heroin was given noncontingently and remifentanil-associated stimuli were presented; in contrast, responding was not altered when the same doses of heroin were given noncontingently without response-contingent presentation of drug-associated stimuli (compare open and filled triangles, figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effects of heroin, given alone (n=4) or with presentation of remifentanil-associated stimuli (n=5), on reinstatement of responding. Left most points show the mean (± 1 SEM) number of responses during baseline sessions in which 0.00032 mg/kg remifentanil was available for self-administration (points above BL) with the mean number of responses emitted during extinction also shown (points above EXT). Reinstatement sessions were preceded by a noncontingent infusion of saline (point above S; responding induced by drug-associated stimuli only) or heroin (0.0032–0.1 mg/kg); responding resulted in the presentation of the remifentanil-associated stimuli during some reinstatement sessions (circles; responding induced by noncontingent drug and presentation of drug-associated stimuli) and not during others (triangles; responding induced by noncontingent drug only). Two separate one-factor repeated-measures ANOVAs were used to detect significant differences in responding across different types of sessions: one analysis detected differences when responding resulted in presentation of drug-associated stimuli during reinstatement sessions (circles) and the other detected differences when drug-associated stimuli were not presented during reinstatement sessions (triangles); + (P<0.05) denotes conditions in which responding was significantly lower than that maintained by 0.00032 mg/kg/infusion remifentanil (BL) and # (P<0.05) denotes conditions in which responding was significantly greater than during extinction (EXT). Filled symbols indicate sessions in which drug-associated stimulus lights were not presented. Ordinate: number of responses in 90-min reinstatement sessions. Abscissa: dose (mg/kg) heroin (i.v.).

The smallest noncontingent dose of heroin that significantly reinstated responding when presented with drug-associated stimuli was used to examine the effects of lorcaserin on heroin-reinstated responding (diamond above S, figure 4). Lorcaserin dose dependently decreased responding during reinstatement tests in which either heroin or cocaine were given noncontingently (figure 4; triangles replotted from figure 1), although the number of reinstated responses was greater after noncontingent administration of heroin, compared with cocaine (points above S, figure 4). There was no significant interaction between lorcaserin dose and noncontingent drug administered before the session (F[3,9]=0.27; P=0.85) as well as no main effect of noncontingent drug (F[1,3]=1.93; P=0.26) in the four monkeys that received noncontingent heroin and cocaine. Lorcaserin significantly decreased responding in five monkeys that received cocaine noncontingently (F[1.36,5.44]=11.81; P=0.01) and in five monkeys that received heroin noncontingently (F[1.98,7.92]=6.53; P=0.02).

Figure 4.

Effects of lorcaserin on the reinstatement of responding previously maintained by cocaine or remifentanil. The mean (± 1 SEM) number of heroin-primed responses were determined across five monkeys during reinstatement sessions in which they received a noncontingent injection of 0.032 mg/kg heroin at the start of the session and presentation of remifentanil-associated stimuli throughout the session (diamonds). Results from cocaine-reinstated responding (triangles) are replotted from figure 1 for comparison. Two separate one-factor repeated measures ANOVAs were used to determine whether lorcaserin decreased responding for each drug prime followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests; filled symbols (P<0.05) indicate doses of lorcaserin that significantly decreased reinstatement of responding, compared with the effects of saline. Ordinate: number of responses in 90-min reinstatement sessions. Abscissa: dose (mg/kg) lorcaserin given s.c.

Discussion

Lorcaserin is under consideration as a treatment for drug abuse. That a single drug might effectively decrease abuse of drugs from different pharmacological classes is thought to be due to role of dopamine in the abuse of drugs and the ability of agonists at 5-HT2C receptors, including lorcaserin, to inhibit indirectly dopamine release. Multiple studies have shown that lorcaserin, given acutely or repeatedly, decreases self-administration of several abused drugs, such as nicotine and cocaine (Banks & Negus, 2017; Collins et al., 2016; Gannon et al., 2017; Gerak et al., 2016; Higgins et al., 2012, 2013; Levin et al., 2011); however, it decreases responding for remifentanil and food nonselectively in a choice procedure, and it does not alter choice of cocaine over food (Banks & Negus, 2017; Panlilio, Secci, Schindler, & Bradberry, 2017). Thus, based on results of preclinical studies, the potential usefulness of lorcaserin for treating drug abuse is somewhat controversial (for review see Collins et al., 2017). While studies in humans will determine the effectiveness of lorcaserin to decrease ongoing drug abuse, preclinical investigation of other aspects of drug abuse would be beneficial. For example, relapse to drug use is one of the biggest problems during treatment, and successful pharmacotherapies would reduce ongoing abuse as well as the likelihood of relapse. Reinstatement procedures are thought to model of some aspects of relapse, and one such procedure was used in the current study to compare the effects of lorcaserin on responding that was reinstated by cocaine to that reinstated by heroin.

Relapse to drug use occurs at high rates and remains a serious impediment to successful treatment. The complexity of this phenomenon makes it difficult to model preclinically, and while no procedure is currently available to model all aspects of relapse, reinstatement procedures are commonly used to model certain features. As with relapse itself, reinstatement procedures can also be complex, and many variations of the reinstatement procedure (de Wit & Stewart, 1981) have been used to examine the effectiveness of potential pharmacotherapeutics to decrease responding reinstated by drug-associated stimuli and/or non-contingent infusions of the drug itself. Thus, the predictive validity of reinstatement procedures for modeling relapse can be limited by the specific conditions used in a study. For example, monkeys in the current study received a noncontingent infusion of heroin or cocaine at the beginning of the reinstatement test. Consequently, this procedure might best predict the likelihood of relapse under conditions in which a patient receives a drug without first making the decision to relapse (e.g., use of an opioid for pain), although having a drug that effectively decreases reinstated responding under the current conditions does not preclude the possibility that the drug would also prevent relapse to repeated and perhaps long-term drug use. In addition, determining predictive validity of reinstatement procedures can be challenging because the most effective pharmacotherapies for reducing the likelihood of relapse are drugs that act at the same receptor as the abused drug to either mimic (e.g. opioid receptor agonists, like methadone) or block its effects (i.e. opioid receptor antagonists, like naltrexone); under these conditions, drug effects and interactions between drugs would be predicted by receptor theory, thereby providing less information about the relationship between reinstatement and relapse. In contrast, reinstatement procedures have some predictive validity when the potential treatment drug acts through a different mechanism than the abuse drug. For example, naltrexone is used to treat alcohol abuse and has been shown to decrease responding reinstated by ethanol as well as stimuli previous associated with ethanol (e.g., Burattini, Gill, Aicardi & Janak, 2006; Le et al., 1999). For the current study, the ability of lorcaserin, a 5-HT2C receptor agonist, to decrease responding reinstated by heroin and cocaine was examined.

Given the prevalence of polydrug abuse, a treatment option that reduces the likelihood of relapse to multiple drugs would be preferable, particularly for individuals who abuse several different drugs. Consequently, the capacity of lorcaserin to attenuate reinstatement of extinguished responding previously maintained by either cocaine or remifentanil was examined in the current study. Before the effects of lorcaserin were studied, responding reinstated by cocaine was compared with that reinstated by heroin. Extinguished responding was significantly increased by noncontingent administration of cocaine or heroin given before sessions in which the drug-associated stimuli were presented contingent upon responding (points above S, figure 4); during these reinstatement tests, the number of responses emitted was similar to the number emitted during cocaine or remifentanil self-administration sessions. Presentation of stimuli alone also increased responding, although the number of responses was not significantly different from that obtained during either self-administration or extinction sessions, likely due to inter-subject variability during reinstatement tests (see triangles, figure 2). Under other experimental conditions, drug-associated stimuli are sufficient to significantly reinstate responding (e.g. in rats; Sutton et al., 2000). In contrast to the variable effectiveness of response-contingent presentation of the drug-associated stimulus alone, noncontingent administration of drug alone was less effective in all monkeys. Neither cocaine nor heroin reinstated responding during sessions when the drug-associated stimuli were omitted (cocaine: Gerak et al., 2016; heroin: triangles, figure 3), suggesting that reinstatement of responding results from an interaction between the direct effects of the noncontingent drug and the stimuli associated with cocaine or remifentanil reinforcement. The number of sessions between reinstatement tests did not alter the magnitude of the reinstatement response by cocaine-associated stimuli alone or by cocaine or heroin when stimuli were presented contingent upon responding. Overall, these data suggest that cocaine and heroin similarly reinstate responding previously maintained by cocaine or remifentanil, respectively.

Lorcaserin attenuated reinstatement of responding previously maintained by either cocaine or remifentanil, although it was more potent at decreasing heroin-reinstated responding, as compared with cocaine-reinstated responding. The current results do not indicate whether the effects of lorcaserin are selective for reinstated responding, as compared with other behavioral and potentially adverse effects; however, comparison of results from two previous studies indicates that, when administered i.g., a 3-fold smaller dose of lorcaserin is needed to decrease cocaine-primed reinstatement, as compared with the dose of lorcaserin needed to decrease responding for food or decrease locomotor activity (Collins et al., 2016; Gerak et al., 2016). These results suggest that the effects of lorcaserin on cocaine-primed reinstatement are not due to a general disruption in behavior. While lorcaserin is more potent at decreasing reinstated responding when it is given s.c. (triangle, figure 4, current study; Gerak et al., 2016), changing the route of administration would not be expected to change the relative potency of lorcaserin to decrease cocaine-reinstated and food-maintained responding. When taken together with results of the current study showing that a smaller dose lorcaserin (s.c.) is needed to attenuate heroin-primed reinstatement, as compared with the dose needed to attenuate cocaine-primed reinstatement (figure 4), these data suggest that the effects of lorcaserin on heroin-primed reinstatement are also not due to a general disruption in behavior. Similarly in rats (Neelakantan et al., 2017), lorcaserin decreased ongoing self-administration of oxycodone as well as responding for presentation of oxycodone-associated stimuli that occurred after extinction of self-administration. Doses of lorcaserin that decreased responding for oxycodone or oxycodone-associated stimuli did not alter spontaneous behavior or responding on a second, inactive lever that was present in the experimental chamber during these sessions, further indicating that lorcaserin can selectively reduce ongoing or reinstated responding for drug. Lorcaserin was also shown to decrease reinstatement of responding for cocaine and nicotine at doses smaller than those needed to decrease food intake or responding for food (Harvey-Lewis et al., 2016; Higgins et al., 2012). Together, these results suggest that lorcaserin might reduce the likelihood of relapse to use of cocaine and heroin, although this effect might only occur at doses that also impact food intake; nevertheless, it might be possible to develop treatment conditions that avoid other effects that would be disruptive to the patient.

In summary, results of the current study show that lorcaserin can decrease reinstatement of extinguished responding that was previously maintained by cocaine or an opioid. The generality of this effect of lorcaserin in reducing responding maintained or reinstated by drugs from different pharmacological classes could be an advantage when treating polydrug abusers. While lorcaserin attenuated reinstated responding at doses smaller than those needed to produce some, potentially adverse, effects (current study; Collins et al., 2016), the therapeutic window for lorcaserin might be small such that some other effects could not be avoided. Nevertheless, the ability of lorcaserin to reduce ongoing self-administration or reinstatement of extinguished responding suggests that more studies might be warranted to determine whether adverse effects limit its clinical usefulness.

Public Significance Statement:

The serotonin2C (5-HT2C) receptor-selective agonist lorcaserin is receiving considerable attention as a possible treatment for abuse of a variety of drugs, including cocaine and opioids. This study showed that lorcaserin is equally potent and effective in decreasing reinstatement of extinguished responding previously maintained by either a stimulant or an opioid. The generality of this effect across different pharmacological classes of abused drugs might be useful in treating polydrug abusers.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health [grant number R01 DA05018] and by the Welch Foundation [Grant AQ-0039]. The funding source had no role other than financial support.

The authors thank Eli Desarno, Steven Garza, Sarah Howard, Jade Juarez, Krissian Martinez, Emily Spolarich and Peter Weed for their technical contributions towards the completion of these studies. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

All authors contributed in a significant way to the manuscript and have read and approved the final manuscript.

The ideas and data presented here have not been disseminated in any form prior to appearing in this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Lisa R Gerak, Department of Pharmacology and the Addiction Research, Treatment & Training Center of Excellence, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, TX.

Gregory T Collins, Department of Pharmacology and the Addiction Research, Treatment & Training Center of Excellence, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, TX; South Texas Veterans Health Care System, San Antonio, TX.

David R. Maguire, Department of Pharmacology and the Addiction Research, Treatment & Training Center of Excellence, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, TX.

Charles P France, Departments of Pharmacology and Psychiatry, and the Addiction Research, Treatment & Training Center of Excellence, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, TX.

References

- Aronne L, Shanahan W, Fain R, Glicklich A, Soliman W, Li Y, & Smith S (2014). Safety and efficacy of lorcaserin: a combined analysis of the BLOOM and BLOSSOM trials. Postgraduate Medicine, 126, 7–18. 10.3810/pgm.2014.10.2817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, & Negus SS (2017). Repeated 7-day treatment with the 5-HT2C agonist lorcaserin or the 5-HT2A antagonist pimavanserin alone or in combination fails to reduce cocaine vs food choice in male rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology, 42, 1082–1092. 10.1038/npp.2016.259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burattini C, Gill ML, Aicardi G, & Janak PH (2006). The ethanol self-administration context as a reinstatement cue: acute effects of naltrexone. Neuroscience 139, 877–887. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan EW, He Y, Chui CSL, Wong AYS, Lau WCY, & Wong ICK (2013). Efficacy and safety of lorcaserin in obese adults: a meta-analysis of 1-year randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and narrative review on short-term RCTs. Obesity Reviews, 14, 383–392. 10.1111/obr.12015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Gerak LR, & France CP (2017). The behavioral pharmacology and therapeutic potential of lorcaserin for substance use disorders. Neuropharmacology 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.12.023 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Gerak LR, Javors MA, & France CP (2016). Lorcaserin reduces the discriminative stimulus and reinforcing effects of cocaine in rhesus monkeys. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 356, 85–95. 10.1124/jpet.115.228833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, & Stewart J (1981). Reinstatement of cocaine-reinforced responding in the rat. Psychopharmacology 75, 134–143. 10.1007/BF00432175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, & Imperato A (1988). Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 85, 5274–5278. 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon BM, Sulima A, Rice KC, & Collins GT (2017). Inhibition of cocaine and 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) self-administration by lorcaserin is mediated by 5-HT2C receptors in rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 364, 359–366. 10.1124/jpet.117.246082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerak LR, Collins GT, & France CP (2016). Effects of lorcaserin on cocaine and methamphetamine self-administration and reinstatement of responding previously maintained by cocaine in rhesus monkeys. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 359, 383–391. 10.1124/jpet.116.236307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey-Lewis C, Li Z, Higgins GA, & Fletcher PJ (2016). The 5-HT2C receptor agonist lorcaserin reduces cocaine self-administration, reinstatement of cocaine-seeking and cocaine induced locomotor activity. Neuropharmacology 101, 237–245. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins GA, Silenieks LB, Lau W, de Lannoy IA, Lee DK, Izhakova J, … Fletcher PJ (2013). Evaluation of chemically diverse 5-HT2C receptor agonists on behaviours motivated by food and nicotine and on side effect profiles. Psychopharmacology 226, 475–490. 10.1007/s00213-012-2919-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins GA, Silenieks LB, Rossman A, Rizos Z, Noble K, Soko AD, & Fletcher PJ (2012). The 5-HT2C receptor agonist lorcaserin reduces nicotine self-administration, discrimination, and reinstatement: relationship to feeding behavior and impulse control. Neuropsychopharmacology 37, 1177–1191. 10.1038/npp.2011.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL, & Cunningham KA (2015). Serotonin 5-HT2 receptor interactions with dopamine function: implications for therapeutics in cocaine use disorder. Pharmacological Reviews 67, 176–197. 10.1124/pr.114.009514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt RT, Croghan IT, Schroeder DR, Hays JT, Choi DS, & Ebbert JO (2017). Combination varenicline and lorcaserin for tobacco dependence treatment and weight gain prevention in overweight and obese smokers: a pilot study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 19, 994–998. 10.1093/ntr/ntw304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauritzen G, & Nordfjaern T (2018). Changes in opiate and stimulant use through 10 years: The role of contextual factors, mental health disorders and psychosocial factors in a prospective SUD treatment cohort study. PLoS ONE, 13, e0190381 10.1371/journal.pone.0190381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Poulos CX, Harding S, Watchus J, Juzytsch W, & Shaham Y (1999). Effects of naltrexone and fluoxetine on alcohol self-administration and reinstatement of alcohol seeking induced by priming injections of alcohol and exposure to stress. Neuropsychopharmacology 21, 435–444. 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00024-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Johnson JE, Slade S, Wells C, Cauley M, Petro A, & Rose JE (2011). Lorcaserin, a 5-HT2C agonist, decreases nicotine self-administration in female rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 338, 890–896. 10.1124/jpet.111.183525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manvich DF, Kimmel HL, & Howell LL (2012). Effects of serotonin 2C receptor agonists on behavioral and neurochemical effects of cocaine in squirrel monkeys. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 341, 424–434. 10.1124/jpet.111.186981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neelakantan H, Holliday ED, Fox RG, Stutz SJ, Comer SD, Haney M, …Cunningham KA (2017). Lorcaserin suppresses oxycodone self-administration and relapse vulnerability in rats. ACS Chemical Neuroscience 8, 1065–1073. 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panlilio LV, Secci ME Schindler CW, & Bradberry CW (2017). Choice between delayed food and immediate opioids in rats: treatment effects and individual differences. Psychopharmacology 234, 3361–3373. 10.1007/s00213-017-4726-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, & Stewart J (1996). Effects of opioid and dopamine receptor antagonists on relapse induced by stress and re-exposure to heroin in rats. Psychopharmacology 125, 385–391. 10.1007/BF02246022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan WR, Rose JE, Glicklich A, Stubbe S, & Sanchez-Kam M (2017). Lorcaserin for smoking cessation and associated weight gain: a randomized 12-week clinical trial. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 19, 944–951. 10.1093/ntr/ntw301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shram MJ, Schoedel KA, Bartlett C, Shazer RL, Anderson CM, & Sellers EM (2011). Evaluation of the abuse potential of lorcaserin, a serotonin 2C (5-HT2C) receptor agonist, in recreational polydrug users. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 89, 683–692. 10.1038/clpt.2011.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SR, Prosser WA, Donahue DJ, Morgan ME, Anderson CM, & Shanahan WR; APD356–004 Study Group. (2009). Lorcaserin (APD356), a selective 5-HT2C agonist, reduces body weight in obese men and women. Obesity, 17, 494–503. 10.1038/oby.2008.537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SR, Weissman NJ, Anderson CM, Sanchez M, Chuang E, Stubbe S, … Shanahan WR; Behavioral Modification and Lorcaserin for Overweight and Obesity Management (BLOOM) Study Group. (2010). Multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of lorcaserin for weight management. New England Journal of Medicine, 363, 245–256. 10.1056/NEJMoa0909809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2017). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 17–5044, NSDUH Series H-52). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MA, Karanian DA, & Self DW (2000). Factors that determine a propensity for cocaine-seeking behavior during abstinence in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology, 22, 626–641. 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00160-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G, Pontieri FE, & Di Chiara G (1997). Cannabinoid and heroin activation of mesolimbic dopamine transmission by a common µ1 opioid receptor mechanism. Science, 276, 2048–2050. 10.1126/science.276.5321.2048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen WJ, Grottick AJ, Menzaghi F, Reyes-Saldana H, Espitia S, Yuskin D, …Behan D (2008). Lorcaserin, a novel selective human 5-hydroxytryptamine2C agonist: in vitro and in vivo pharmacological characterization. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 325, 577–587. 10.1124/jpet.107.133348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman NJ, Sanchez M, Koch GG, Smith SR, Shanahan WR, & Anderson CM (2013). Echocardiographic assessment of cardiac valvular regurgitation with lorcaserin from analysis of 3 phase 3 clinical trials. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging, 6, 560–567. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.000128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]