Abstract

Background:

Although US cigarette smoking rates have steadily declined, the changing nature of nicotine consumption and the popularity of non-combustible nicotine products urges us to revise tobacco prevention strategies. Research on smoking perspectives among Hispanic youth is limited yet crucial for prevention efforts with Hispanics being the largest minority in the U.S.

Objective:

This study sought to understand the experience and perceptions of low-income Hispanic youth regarding tobacco use.

Methods:

Forty-nine adolescents (ages 9 to 19) from El Paso, Texas, participated in five extended focus group discussions about tobacco/nicotine use.

Results:

Adolescents were predominantly exposed to tobacco through relatives, although school and party contexts became more relevant as youth aged. Youth had negative perceptions of tobacco and smokers, but believed their peers often viewed tobacco positively. Youth also saw tobacco use as a functional stress-management strategy, especially within their extended family. Health and family were strong motivators not to smoke.

Conclusions:

Youth maintain several tensions in their views on tobacco. Tobacco use is considered unpleasant and harmful, yet youth perceive their peers to view it as cool. Peer to peer discussion of tobacco experiences and perceptions may help correct these incongruent viewpoints. Adding to this tension is the perception that tobacco is used to manage stress. Given the importance of the home environment for Hispanic youth, tobacco prevention efforts may benefit from engaging family to identify the ways in which tobacco use causes stress.

Keywords: Tobacco, Qualitative research, Perceptions, Prevention, US-Mexico border

Despite declines in smoking rates, tobacco use remains the leading cause of preventable disease and death in the United States (Jamal, King, & Neff, 2016). Electronic and flavored nicotine products, like e-cigarettes and hookahs, pose additional challenges as their novelty and varied flavors are presently attracting youth to initiate tobacco use (Ambrose et al., 2015). Furthermore, morbidity and mortality disparities related to tobacco persist by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status (Henley et al., 2016). Currently, smoking and tobacco prevention efforts, such as mass media campaigns and school-based programs, are largely focused on the harms of tobacco products and regular cigarettes (Riordan, 2017). Given the cost-effectiveness of tobacco prevention efforts and the changing nature of nicotine consumption, tobacco prevention strategies must be revised to reflect the current environment (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). Growing use of non-combustible nicotine products and marketing of new nicotine products further support the need to revise prevention strategies. For tobacco prevention programs to succeed, we need a clear understanding of the focal population’s perceptions of tobacco and nicotine consumption and how these influence their decision to use these products. Thus, in an effort to improve tobacco prevention programs, this study sought to understand attitudes towards tobacco among youth in a predominantly low-income Hispanic community.

Understanding Hispanic attitudes toward tobacco use is important as Hispanics are the largest minority in the United States. (United States Census Bureau, 2017). Research on Hispanic populations has revealed both protective (McCleary-Sills, Villanti, Rosario, Bone, & Stillman, 2010) and harmful (Amrock & Weitzman, 2015) perspectives regarding tobacco use, suggesting that attitudes about tobacco depend on region and environment. Few studies on tobacco attitudes have been conducted among young, U.S.-Mexico border populations. Additionally, most studies have focused on teenagers or young adults and have left out elementary school-aged children. Evidence supports the need to start tobacco prevention programs at an elementary-school age (CDC, 1994). To do that successfully, we must understand how elementary students think about tobacco and how these perceptions differ from middle and high school students. Analysis of teen and pre-teen attitudes towards tobacco in El Paso, Texas is valuable because a large proportion of this population have multiple risk-factors for tobacco-use initiation (i.e. low-income family, parents with low-education, and low academic performance) (City of El Paso Department of Public Health, 2013; Johnston, O’Malley, Miech, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2016).

The design and implementation of tobacco-use prevention programs requires understanding the factors that influence youths’ decisions to initiate use of tobacco and nicotine products. Evidence suggests teens’ perceptions of tobacco influence their decision to begin and continue smoking (Chalela, Velez, & Ramirez, 2007; Kann, McManus, & Harris, 2016). The importance of perceived harms as a construct in several health behavior theories also supports the need to consider youth tobacco attitudes when designing prevention programs (Miles, 2008). High school and middle school students are typically aware of some harms of tobacco use and tend to perceive e-cigarettes as less harmful than regular cigarettes (Barrington-Trimis et al., 2015; Peters, Meshack, & Lin, 2013). Studies exploring young children’s perceptions on tobacco are limited; however, one focus group analysis with elementary-aged children reported that children as young as 10 years old had negative feelings about tobacco, and that they felt they already knew about the harms of smoking (Chen, Kaestle, Estabrooks, & Zoellner, 2013). Although teenagers and children tend to perceive smoking negatively, it is unclear what consequences they perceive as most important.

The environment in which youth are exposed to tobacco is important to consider to ensure that tobacco prevention programs are relevant to youth’s current experiences. Exposure to second-hand smoke typically occurs at home, suggesting that youths’ primary experience with smoking is through a family member (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006). A multi-national study found that 44% of never-smoker adolescents were exposed to second-hand smoke outside the home, highlighting the importance of youth’s social environments for tobacco-use prevention (Veeranki et al., 2015). However, little is known about the specific sites or events where teens and pre-teens are exposed to tobacco use and what emotions these experiences elicit. Understanding the situations where youth may be tempted to try smoking can help tobacco prevention programs be more effective in conveying contextually relevant information.

Tobacco prevention programs need to understand how youth view tobacco and how these views may change as they go from elementary to high school. Although reasons prompting youth to use tobacco, like efforts to seem cool or fit in, are well documented, reasons motivating youth to avoid tobacco have not been thoroughly explored. To provide youth with the education and skills needed to avoid tobacco use, it is important to consider the focal population’s perceived benefits of not using tobacco.

This study sought to understand the experience and perceptions of low-income Hispanic youth (ages 9 to 18) living on the U.S.-Mexico border regarding tobacco and electronic cigarette use. Specific questions this study aimed to answer were: 1) How do youth perceive tobacco and electronic cigarette use, including its popularity and consequences? 2) In what physical environments are youth exposed to tobacco and e-cigs, and what are youth perceptions of their tobacco exposure experiences? 3) How do youth perceive tobacco users motivations to smoke? 4) What reasons to not use tobacco do youth value?

METHODS

Data for this study were collected using two data collection approaches: 1) focus groups and 2) written survey responses. The use of these data collection methods allowed for analysis of both individually and socially constructed data. Before beginning data collection with each group, students were reminded of their rights as study participants and of the importance of honesty in their written and oral answers. Participants responded to close-ended questions on a written survey before each focus group discussion. The survey collected demographic information, self-reported tobacco use (Have you ever tried cigarettes or tobacco, even just one puff?), tobacco use intentions (Do you think you will use any form of tobacco in the next 12 months?) and student’s perception of tobacco use among peers (About how many students in your grade use tobacco?). Items were based on Global Youth Tobacco Survey questions (Global Youth Tobacco Survey Collaborative Group, 2012). For the focus groups, 7 to 14 individuals were gathered and asked about their feelings, perceptions and opinions regarding tobacco use. Students were given the choice to participate in English or Spanish during each focus group. The majority of participants preferred to conduct the hour-long session in English, with some alternating between the two languages. The elementary focus group was conducted almost exclusively in Spanish at the request of the participants. Reasons for not smoking were ranked as an activity to incite discussion among high school and middle school groups. This activity was not conducted among the elementary school group due to time constraints; however, their top reasons for not smoking were obtained through discussion. Focus group discussions were recorded and transcribed, and later analyzed for trends and patterns.

Recruitment

A call for participation was made via flyers to children from different schools in El Paso and to residents of a housing development in El Paso. Research staff explained the participation requirements, study procedures, and incentives to interested youth and parents. The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects approved the study.

Sample

Five focus groups were held at a community center in El Paso, with 49 individuals participating in the study. The teen participants were divided to keep age groups more closely aligned in the level of discussion about tobacco issues: one group was among elementary school age children (n=7; ages 9–11); two of the groups were among middle school age teens and preteens (n=21; ages 11 to 14), and two groups were among high school age teens (n=20; ages 15 to 19). Although there was an attempt to balance the sample by gender, more males than females participated in the study (60% male and 40% female). The participants represented segments of El Paso’s population that are majority Latino. The focus group sample was purposely biased toward individuals who might be deemed “high risk” based on neighborhood and income: at least 90% of student participants (n=43) qualify for free school lunch (only one said they did not qualify; four participants did not know).

Analysis

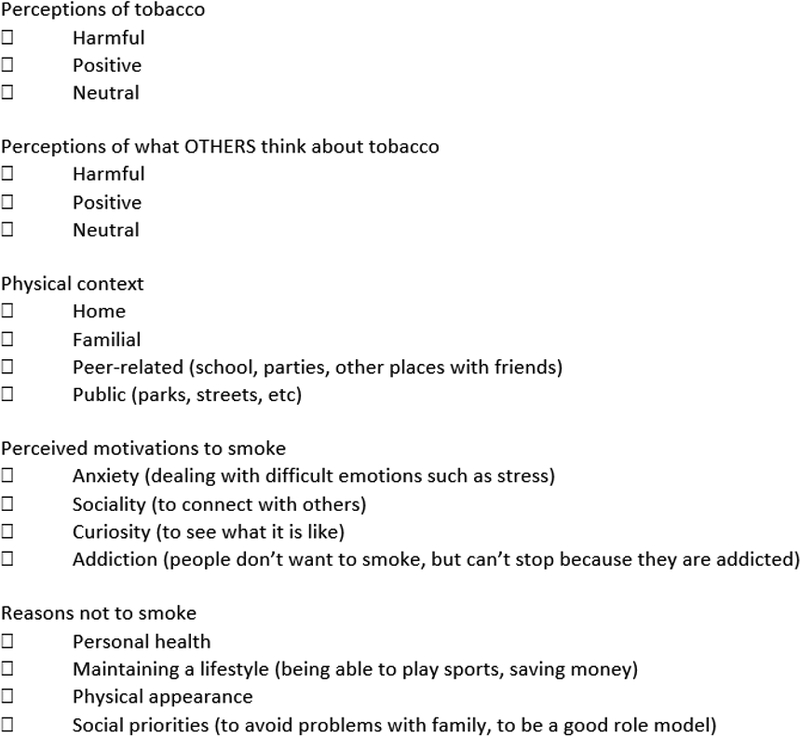

Focus group transcripts and written survey responses were analyzed jointly using descriptive statistics and standard qualitative analysis approaches, in which codes were associated with portions of text, and patterns were identified within and across codes to reflect relationships within the data (Saldana, 2007). A lead coder (MJ) developed codes based on the focus group guide and on the concepts that emerged from the text. Each substantive comment within the focus groups was analyzed within one of four key organizing themes touched on during our discussions: 1) perceptions of cigarettes/tobacco, 2) the physical context of tobacco use 3) perceived motivations to smoke and 4) most salient reasons to not smoke. Within each theme, discrete sections of narrative text were tagged according to emerging subthemes in order to create meaningful analytic groupings. See Figure 1 for list of themes and subthemes. We then discussed findings as a team and where there were divergent views, we discussed until we collectively agreed upon a single interpretation of the data (Bradely, Curry, & Devers, 2007). This process of analysis, reflecting, and discussing the transcripts and statements between the authors enhanced the thoroughness of our analysis (Leung, 2015).

Figure 1: Identified Themes and Subthemes.

RESULTS

1. Perceived popularity and consequences of tobacco use

Based on survey responses, there were large discrepancies between perceived prevalence and actual prevalence of tobacco use (see Table 1). Despite focus group participants’ presence in what are traditionally considered “high risk” groups, participating preteens and teens reported minimal intentions for future use of tobacco in the survey. Nevertheless, survey data indicated older youth perceived increasingly high rates of tobacco use among their peers. Some youth also reported frequent use of e-cigarettes among peers. Although none of the elementary school students viewed smoking as a problem in their grade, 9 (42%) middle school students and 12 (60%) of high school students reported in their survey that some, half, or most of their peers smoke. Focus group responses indicated adolescent participants overwhelmingly felt that cigarettes were harmful to their health. Despite their negative personal perceptions of cigarettes, by middle school age, teens overwhelmingly reported that others saw cigarettes differently: as “cool,” “fun,” “great,” “good,” “the new style,” or even “good for them.” Middle school students reported that most kids nine years old or younger do not think about cigarettes, but when they get to “about 7th grade,” they change their mind in part to feel more mature. For example, middle school students responded to the question “Most kids my age smoke because…” with the following: “They think it is good for them”, “Because their older friends smoke”, “They think they are going to be cooler”, “They want friends”, and “They’ll have more friends and become popular”.

Table 1:

Perceived frequency of tobacco use behavior among peers

| Perceived peer use of tobacco frequency | School group (n=47) | Total (Percentage) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High School | Middle School | Elementary School | |||

| Most | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 (11%) | |

| About half | 5 | 0 | 1 | 6 (13%) | |

| Some | 7 | 6 | 1 | 14 (30%) | |

| Very few | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 (9%) | |

| None of them | 1 | 1 | 5 | 7 (15%) | |

| I don’t know | 1 | 7 | 3 | 11 (23%) | |

| Total | 16 | 19 | 12 | 47 | |

| Number of self-reported tobacco users | 0 | 7 | 1 | 8 (17%) | |

2. Physical environments for exposure to tobacco

Regardless of their age or grade, youth participants had powerful personal narratives about their experiences with tobacco. The nature of the personal narratives shared by preteens and teens varied across grade levels. Family contexts were central to student’s narratives, especially among elementary students. These often included negative feelings associated with their experiences and sensory details indicating what they felt, smelled and saw when family members smoked. The following are some descriptions of their first experiences with tobacco:

“I was at my aunt’s house when they started smoking and it smelled so strongly of cigarettes that I had to go outside.”

“I was seven years old and I could smell the odor. I was in my grandmother’s house. I had to leave because I just couldn’t take it anymore.”

“My sister was with her friends, they were all laughing, they looked like they were drunk.”

When middle school students were first around somebody smoking cigarettes, their comments displayed a developmental period of conflicted feelings about tobacco use—with many negative family associations with tobacco, but also confusion as they began to see peers engage in intermittent tobacco use.

“I was mad, my grandpa smokes and my little brother has asthma because of the smoking. He was smoking in front of him. I did not say anything. He already passed away. About two years ago.”

“I was surprised because [the smokers] were younger. We were at the park and the girls started taking out cigarettes. They were 11 years old, I kind of knew them. I asked them why did you taste them and they said for fun. I did not try [the cigarettes] but they did offer.”

“I was confused, my friend was smoking last year after school I was walking and I saw him smoking.”

The following quotes demonstrate how high school students tended to focus more on peer experiences, stated matter-of-factually, without as many negative associations or confusion.

“There are so many fights, and drugs. Those things and cigarettes [are everywhere]. At home, at school, during all the school day, and after school, home again…nowadays practically everywhere….”

“I was like 13. And was it a group of my friends, of kids my age. [We were] outside of school, before school and they were smoking. And they offered me a cigarette. Feels weird, the first time you taste that.”

“Um, like you just go to a party, like nobody really says ‘do you want a smoke’. Like if you’re at a party and there’s going to be [cigarettes/drugs/alcohol], like nobody’s going to like talk to you, they’re just going to hand it to you.”

“I see people smoke [e-cigarettes] in class.”

3. Perceived Motivations to Use Tobacco

Dealing with emotions was the most commonly cited reason by teens to turn to cigarettes during focus group discussions. Participants across all grade levels mentioned worries, problems, anxiety—related to the stresses of school and home environments—and suggested that teens use tobacco to relax and calm down. In these cases, participants believe tobacco use is functional or serves a purpose (i.e., to put one at ease). This functional association seemed to be acquired in participants’ homes, through observations of family members’ habits or overheard comments (e.g., “Um, my grandma when she’s stressed, she’s always smoking. And she gets mad when she doesn’t have cigarettes. She gets in a bad mood”).

Many teens saw a conflict of emotions playing out, where family smokers wanted to quit, but couldn’t because of their addiction (e.g., “When my grandma smokes she feels mad and sad at the same time. She just doesn’t find an exit. She wants to quit but can’t.” “My dad is addicted to smoke when he’s stressed. It’s an addiction. When he gets mad, he smokes”).

Social reasons for smoking were cited frequently across all grade levels. Those reasons included peer pressure, looking cool, wanting to fit in, or wanting to seem older. The perception is kids smoke to gain acceptance by peers or establish a social identity (e.g., “When a teenager wants to maybe look cool, and try to get friends and just be cool [they smoke]. And they want more attention and [want to] be popular. I don’t necessarily think that, but I’ve seen it happen”).

Participants also reported the role that curiosity plays in the initiation of smoking behaviors (e.g., “Well, of course, there’s curiosity leading to getting experience, right? Seeing how like, oh let’s see how it works. How does it affect me? My body? Yeah, that actually happen”).

In the following comment participants suggested a link between social context or peer pressure and curiosity regarding tobacco.

“Curiosity (is big) because you see your friends doing it, so you want to try it. And then that’s why you start. A whole bunch of people around you are trying it, like anything else, right, that makes you curious.”

4. Reasons Not to Use Tobacco

A healthy life was important across all age groups, but appeared especially important for middle school students or younger. When asked to rank life factors that are important to them during focus group discussions, preteens and teens tended to prioritize their current and future health over social factors such as making friends or fitting in. In fact, making friends, fitting in, and becoming popular did not rank in the top five items for any group (Table 2). The importance of maintaining their health in the future was reiterated in the discussions. When asked for reasons why they wouldn’t smoke, one student responded, “Every year something new comes out and I want to live to see the future and I want to be there.” Adolescents also highlighted undesirable lifestyle changes that would ensue if cigarettes were a part of their lives. The following are some other examples of their responses when asked for reasons why they wouldn’t try tobacco:

Table 2.

Top five reasons to avoid tobacco use, average ratings among high school and middle school groups

| Area | Rank Order of Importance | |

|---|---|---|

| High school | Middle school | |

| Making your parents proud | 1 | |

| Living a long life | 2 | |

| Having a healthy heart | 3 | 1 |

| Having money to spend on things you want | 4 | |

| Having energy and feeling happy | 5 | 3 |

| Strong lungs (running without losing your breath) | 2 | |

| Following the rules and the laws | 4 | |

| Not dying an early, painful death | 5 | |

“To have a healthy life. I know a lot of people that have cancer…my brother…my grandma…).

“Because once you’re addicted, like it’s hard to get out.”

“When I was little I drank got dizzy, I like being in control of myself. Ever since then I want to make sure I feel in control.”

“To be able to skate and stay active.”

“You’d spend most of your money on cigarettes – why would you spend money on something that lasts days…”

These teens’ comments suggest that losing control is one negative aspect of cigarette smoking. Another undesirable lifestyle change identified by high school students was a lack of focus or ability to engage in activities of interest. Specifically, these teens felt that cigarettes would keep them from paying attention in school or from being successful in their pursuit of sports activities. High school students also recognized smoking as an expensive habit. Changes in physical appearance, including the onset of bad breath, or having “ugly teeth and nails” were also of concern. Mostly, tobacco use was associated with a loss of a youthful look (e.g., “I mean, you can see people who smoke look like they’re old. Like their face, like they’re like in their early twenties, but they look like forty…”).

Especially in high school, students highlighted the importance of familial approval in their lives (e.g., “I don’t want to cause problems. I think my family would be angry.” “My mom wants me to have a good job and a career and that is important to me I want to make her proud”). Their comments suggest that parental approval and acceptance is essential to their sense of self, and that they would abstain from smoking cigarettes to avoid problems with their family and make family members proud. High school students wanted to serve as good role models in their families and viewed tobacco use as compromising their position as a role model e.g., “well, really in my life I haven’t been – I haven’t had a role model. Like a good example of a role model. So I want to be that for future generations of my life).

DISCUSSION

This study revealed multiple tensions in youth’s perceptions and experience with tobacco use, which have valuable implications for future anti-tobacco programs targeting Hispanic youth.

First, focus group discussions and the questionnaire revealed a contradiction between youth’s personal tobacco views and experiences, and those they perceive their peers to have. Similar to past studies (Chalela et al., 2007; Rothwell & Lamarque, 2011), youth had negative perceptions of tobacco, but believe their peers to think of tobacco as something positive—particularly “cool’ and “fun.” Although youth’s perceived motivations to smoke included “to be cool” or “to fit in”, when asked for personal reasons why they would not use tobacco, leading a healthy life consistently ranked as more important to these adolescents than making friends or fitting in. Questionnaire results showed that regardless of youth’s own smoking status, adolescents in this focus group series tended to overestimate actual smoking rates among their peers, which in previous research has predicted the initiation of smoking, experimentation, and progression in smoking stage (Flay, 2009; Forrester, Biglan, Severson, & Smolhowski, 2007; Simons-Morton, 2002). It is imperative that tobacco prevention programs address this disconnect between youth’s own tobacco views and how they perceive other youth view tobacco. Peer to peer discussions, where youth share their personal experiences and views on tobacco could effectively highlight ways in which teen’s perceptions about what others are thinking and doing are inaccurate. Another way to address overestimation of smoking rates among youth is to incorporate a social norms marketing campaign into anti-tobacco programs, with the objective of creating a social climate in which students better understand peer disapproval of tobacco use (Dewhirst & Lee, 2011). By credibly presenting information about peer group norms, perceived peer pressure is reduced and individuals are more likely to express preexisting attitudes and beliefs that are health promoting.

Another tension observed in our study was youth’s perception of tobacco having both a functional and a harmful role, especially within their families. The importance of family in Hispanic youth’s perception and experience with tobacco was clear throughout the focus group discussions. Familismo in Hispanic culture encourages frequent gatherings with extended family members (Landale, Oropesa, & Bradatan, 2006), which could explain why most focus group participants had negative accounts of tobacco use through a family member. Despite having strong personal narratives on the adverse effects of tobacco use, smoking was widely perceived as a stress coping strategy among youth. Consistent with past focus groups conducted with adolescents (Watson, Clarkson, & Donovan, 2003), problems, stress and anxiety were frequently cited as reasons to both try tobacco and continue use. Youth face substantial stress in home and school environments, and saw family members using tobacco as a stress management solution. It is critical that tobacco prevention programs address this reason to use. There are certain changes in emerging adulthood, such as losing a job or experiencing a breakup, that have been found to be associated with smoking among Hispanics (Allem, JP et al., 2013). Getting families to talk about some of these stressful situations and healthy ways to cope with them could help youth overcome the temptation to try smoking for stress release (Allem, JP et al., 2016). Another strategy may be to help youth understand the stresses that are actually caused by tobacco use, perhaps by having youth interview family smokers. Tobacco prevention programs may also succeed by helping youth develop their own coping strategies.

Interventions where youth can share with peers their experiences with smoking in family settings may be successful in establishing consensus of the negative impact tobacco has on individuals and families, which was a strong motivation not to smoke among youth in this study. Youth did not report stories of family members using electronic cigarettes, although some youth reported frequent use among their peers. Tobacco prevention programs may need to specifically collect and share stories about electronic cigarettes that discourage use with youth to fill this gap.

Further complicating the above-mentioned contradictions in youth’s tobacco use perceptions is the tension created by their desire to please both their families and their peers. Key reasons to not use tobacco were to make their parents proud and set a good example for younger siblings, which is consistent with past findings among Hispanic youth (Kelly, Comello, & Edwards, 2004). Respeto, honoring parents and elders, is a cultural value that has been found to be important in Hispanic youth’s decision not to engage in substance abuse (Escobedo et al., 2018). At the same time, the importance of peer acceptance in youth risk behaviors is widely documented in literature (Jeon & Goodson, 2015) and was evident in our focus groups as participants across all ages reported “fitting in” as a reason why someone would take up smoking. This tension between pleasing family and peers may explain why some youth in our focus groups reported feelings of confusion when they first witnessed a friend or peer using tobacco. This observed tension between youth’s perceived family and peer expectations further supports the benefit of having tobacco prevention programs work towards reducing peer pressure through the incorporation of teen discussions or sharing of personal narratives.

Since parents and family are important reasons to avoid tobacco use initiation among youth, a successful anti-tobacco program targeting Hispanic populations would likely involve families and the initiation of conversations within families about tobacco use. Some of the powerful personal narratives that could dissuade youth from engaging in tobacco use are accessible through parents, siblings and extended family members. In many cases, these individuals are not talking directly with youth about cigarettes. By extending tobacco prevention programs into the home and facilitating conversations among family, the effects of school-based prevention programs may last longer.

Our study was unique in that it included youth from three school levels (elementary, middle and high school) and this allowed analysis of differences in attitudes across age groups. Another strength was the ability to conduct the focus groups bilingually which facilitated discussions with youth who use both English and Spanish in their daily conversations. One limitation to our study is the small and specific (mostly Hispanic) sample, which restricts the ability to generalize the information gathered to other populations. Other qualitative studies could look for differences in smoking perceptions among youth with different ethnicities. Although the tendency to give socially accepted responses was observed among youth in discussions, this limitation was addressed by the use of the questionnaire to capture individualized information.

CONCLUSION

This study provides several unique insights into the nature of tobacco use among low-income, Hispanic youth that have important implications for tobacco prevention programs. In particular, findings highlight the important role family plays in Hispanic, adolescents’ perceptions of the habit of smoking and their decisions not to begin smoking. Tobacco prevention programs targeting Hispanic youth could benefit from incorporating family into the content and helping youth learn from their family members’ adverse experiences with tobacco use. Programs may succeed by correcting the notion that tobacco is useful for coping with stress by helping youth identify the stresses family members experience because of tobacco use. Another important and consistent observation was the discrepancy between youth’s actual opinions and experiences with tobacco use and those they perceive their peers have. Smoking prevention programs could address this contradiction by encouraging youth to share their personal narratives with one another, thereby 1) reinforcing the negative aspects of the habit, 2) highlighting commonalities in experiences with smokers in their lives, 3) highlighting commonalities in personal motivations not to smoke and 4) de-normalizing the use of tobacco among their generation.

Funding:

Paso del Norte Health Foundation, National Cancer Institute Acknowledgement of support and assistance: This research was supported by a grant from the Paso del Norte Health Foundation (PdNHF). Additionally, preparation of this article was supported, in part, by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) through a Community Networks Program Center grant (U54 CA153505). Findings and recommendations herein are not official statements of the PDNHF or NCI. We are grateful to the many youth who participated in this study. We thank James Weddell for his editorial assistance with the manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest:

The authors report no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Clinical trials registry site and number: NA

References:

- Ambrose BK, Day HR, Rostron B, Conway KP, Borek N, Hyland A, & Villanti AC (2015). Flavored Tobacco Product Use Among US Youth Aged 12–17 Years, 2013–2014. JAMA, 314(17), 1871–1873. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrock SM, & Weitzman M (2015). Adolescents’ perceptions of light and intermittent smoking in the United States. Pediatrics, 135(2), 246–254. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington-Trimis JL, Berhane K, Unger JB, Cruz TB, Huh J, Leventhal AM, … McConnell R (2015). Psychosocial Factors Associated With Adolescent Electronic Cigarette and Cigarette Use. Pediatrics, 136(2), 308–317. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradely EH, Curry LA, & Devers KJ (2007). Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Services Research, 42(4), 1758–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs-2014. Retrieved from Atlanta, Georgia:

- Chalela P, Velez LF, & Ramirez AG (2007). Social Influence and Attitudes and Beliefs associated with Smoking among Border Latino Youth. Journal of School Health, 77(4), 187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y-CY, Kaestle CE, Estabrooks P, & Zoellner J (2013). U.S Children’s Acquisition of Tobacco Media Literacy Skills: A Focus Group Analysis. Journal of Children and Media, 7(4), 409–427. doi: 10.1080/17482798.2012.755633 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- City of El Paso Department of Public Health. (2013). City of El Paso Community Health Assessment Final Report. Retrieved from https://www.elpasotexas.gov/~/media/files/coep/public%20health/community%20health%20assessment%20final%20report.ashx?la=en

- Dewhirst T, & Lee WB (2011). Social Marketing and Tobacco Control The SAGE handbook of social marketing (pp. 391–404). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR (2009). The promise of long-term effectiveness of school-based smoking prevention programs: a critical review of reviews. Tobacco Induced Diseases, 5(1), 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester K, Biglan A, Severson HH, & Smolhowski K (2007). Predictors of smoking onset over two years. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 9(12), 1259–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Youth Tobacco Survey Collaborative Group. (2012). Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS): Core questionnaire with optional questions, Version 1.0. Retrieved from https://nccd.cdc.gov/GTSSDataSurveyResources/Ancillary/Documentation.aspx?SUID=1&DOCT=1

- Henley SJ, Thomas CC, Sharapova SR, Momin B, Massetti GM, Winn GM, … Rishardson LC (2016). Vital Signs: Disparities in Tobacco-Related Cancer Incidence and Mortality —United States, 2004–2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65(44), 1212–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, King BA, & Neff LJ (2016). Current Cigarette Smoking among Adults--United States, 2005–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal WKLY REP, 65, 1205–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon KC, & Goodson P (2015). U.S adolescents’ friendship networks and health risk behaviors: a systematic review of studies using social network analysis and Add Health data. PeerJ, e1052. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2016). 2015 Overview Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Retrieved from http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2015.pdf

- Kann L, McManus T, & Harris WA (2016). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ, 65(SS-6), 1–174. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6506a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly KJ, Comello ML, & Edwards RW (2004). Attitudes of Rural Middle-School Youth Toward Alcohol, Tobacco, Drugs, and Violence The Rural Educator, 25(3), 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Oropesa RS, & Bradatan C (2006). Hispanic Families in the United States: Family Structure and Process in an Era of Family Change In Tienda M & Mitchell F (Eds.), National Research Council (US) Panel on Hispanics in the United States (pp. 5). Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). [Google Scholar]

- Leung L (2015). Validity, reliability, and generalizability in qualitative research. Journal of Family Medicine, 4(3), 324–327. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.161306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleary-Sills JD, Villanti A, Rosario E, Bone L, & Stillman F (2010). Influences on tobacco use among urban Hispanic young adults in Baltimore: findings from a qualitative study. Prog Community Health Partnersh, 4(4), 289–297. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2010.0017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles A (2008). Perceived Severity: General Description and Theoretical Background. Retrieved from https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/research/constructs/perceived_severity.html

- Peters RJ Jr., Meshack A, & Lin MT (2013). The Social Norms and Beliefs of Teenage Male Electronic Cigarette Use. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 12(4), 300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan M (2017). Public Education Campaigns Reduce Tobacco Use. Retrieved from https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/factsheets/0051.pdf

- Rothwell E, & Lamarque J (2011). The use of focus groups to compare tobacco attitudes and behaviors between youth in urban and rural settings. Health Promot Pract, 12(4), 551–560. doi: 10.1177/1524839909349179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldana J (2007). Fundamentals of qualitative research. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG (2002). Prospective analysis of peer and parent influences on smoking initiation among early adolescents. . Prevention Science, 3, 275–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeranki SP, Mamudu HM, Zheng S, John RM, Cao Y, Kioko D, … Ouma AE (2015). Secondhand smoke exposure among never-smoking youth in 168 countries. J Adolesc Health, 56(2), 167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson NA, Clarkson JP, & Donovan RJ (2003). Filthy or Fashionable? Young People’s perceptions of smoking in the media. Health Education Research, 18(5), 554–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]