During human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) infection, the frequency of cells harboring an integrated copy of viral cDNA, the proviral load (PVL), is the main risk factor for progression of HTLV-1-associated diseases. Accurate quantification of provirus by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) is a powerful diagnostic tool with emerging uses for monitoring viral expression.

KEYWORDS: HTLV-1, induced sputum, peripheral blood, proviral load, T cells, ddPCR

ABSTRACT

During human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) infection, the frequency of cells harboring an integrated copy of viral cDNA, the proviral load (PVL), is the main risk factor for progression of HTLV-1-associated diseases. Accurate quantification of provirus by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) is a powerful diagnostic tool with emerging uses for monitoring viral expression. Current ddPCR techniques quantify HTLV-1 PVL in terms of whole genomic cellular material, while the main targets of HTLV-1 infection are CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Our understanding of HTLV-1 proliferation and the amount of viral burden present in different compartments is limited. Recently a sensitive ddPCR assay was applied to quantifying T cells by measuring loss of germ line T-cell receptor genes as method of distinguishing non-T-cell from recombined T-cell DNA. In this study, we demonstrated and validated novel applications of the duplex ddPCR assay to quantify T cells from various sources of human genomic DNA (gDNA) extracted from frozen material (peripheral blood mononuclear cells [PBMCs], bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and induced sputum) from a cohort of remote Indigenous Australians and then compared the T-cell measurements by ddPCR to the prevailing standard method of flow cytometry. The HTLV-1 subtype c (HTLV-1c) PVL was then calculated in terms of extracted T-cell gDNA from various compartments. Because HTLV-1c preferentially infects CD4+ T cells, and the amount of viral burden correlates with HTLV-1c disease pathogenesis, application of this ddPCR assay to accurately measure HTLV-1c-infected T cells can be of greater importance for clinical diagnostics and prognostics as well as monitoring therapeutic applications.

INTRODUCTION

Globally, human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is estimated to infect around 20 million people, who mostly reside in areas of high endemicity, such as southwestern Japan, the Caribbean, South America, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Mashhad district of Iran (1). Recently, it was confirmed that a very high prevalence of HTLV-1 subtype c (HTLV-1c) infection occurs among Aboriginal adults in Central Australia, where prevalence rates exceed 40% in some remote communities (2). HTLV-1 is a lymphoproliferative and ultimately oncogenic retrovirus that primarily infects CD4+ T cells (3) and is the causative agent of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL), HTLV-1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) (4, 5), and various other immune-mediated disorders (6–10). In remote Australia, HTLV-1 infections are most significantly associated with bronchiectasis and multiple bloodstream bacterial infections (2, 11, 12). The HTLV-1 viral DNA burden is measured as the proviral load (PVL), which is the proportion of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) carrying an integrated copy of the HTLV-1 viral DNA. PVL correlates with the risk of disease development (13–17); however, levels of provirus can vary greatly between individuals, which complicates the prognostic use of this biomarker. Absolute quantification of the HTLV-1 PVL by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) is a sensitive diagnostic tool with emerging applications for monitoring viral expression (18).

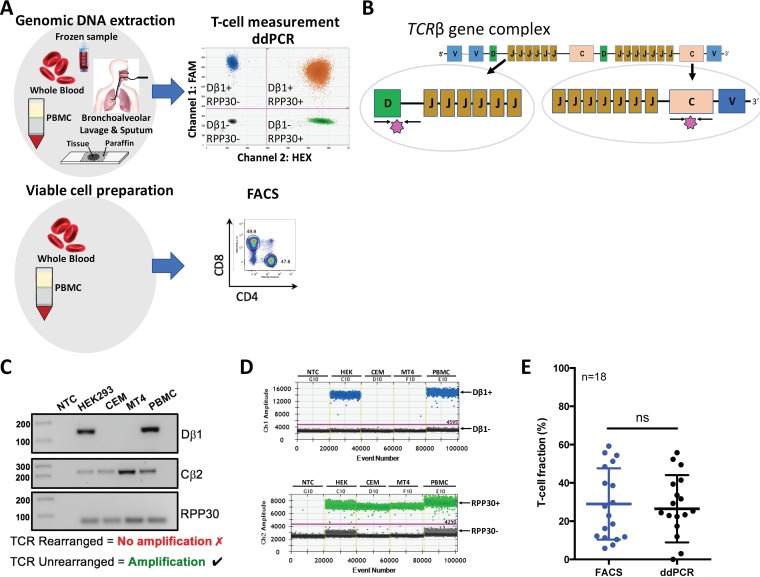

T cells, the main target for HTLV-1 infection, are distinguished by the presence of a unique cell surface markers, such as CD3, CD4, and CD8, and their receptor for antigen, termed the T-cell receptor (TCR) (19) (Fig. 1). Most TCRs are composed of an alpha (α) and a beta chain (β) heterodimer, while a small proportion of T cells that lacks TCRαβ chains expresses an alternative T-cell receptor, TCRγδ, with gamma and delta chains. The majority of T cells undergo rearrangement of their TCRαβ through somatic rearrangement of multiple variable (V), diversity (D), and joining (J) gene segments at the DNA level (20). V(D)J recombination occurs in developing lymphocytes during the early stages of T-cell maturation (21). The first recombination event to occur is between one D and one J gene segment in the beta chain of the TCR. This process could result in joining of the Dβ1 gene segment to any one of the six Jβ1 segments or of the Dβ2 gene segment to any one of the six Jβ2 segments. D-J recombination is followed by the joining of one Vβ segment from an upstream region of the newly formed D-J complex, resulting in a rearranged V(D)J gene segment (20, 22). All other gene segments between V and D segments are eventually deleted from the cell’s genome as a T-cell receptor excision circle (TREC) (23, 24). The V(D)J transcript generated will incorporate the constant (C) region, resulting in a Vβ-Dβ-Jβ-Cβ gene segment. Processing of the primary RNA adds a poly(A) tail after the Cβ and removes unwanted sequence between the V(D)J segment and the constant gene segment (25). The levels of the different functional T cells and proportions of their individual subtypes circulating in blood can vary significantly.

FIG 1.

Validation of T-cell measurement by targeting the unrearranged T-cell receptor in comparison to flow cytometry. (A) Study design and sample composition. Extracted genomic DNA from frozen blood, PBMCs, and bronchoalveolar lavage and sputum samples obtained from a remote Indigenous Australian HTLV-1c cohort was used to measure T cells by a generic single duplex ddPCR assay. Viable cellular material isolated in whole blood and PBMCs from the same HTLV-1c cohort was used to measure T cells by the gold standard method of flow cytometry. (B) Schematic depiction of T-cell receptor β (TCRβ) loci and the oligonucleotides (black arrows) and probes (pink star) used for detecting non-T cells (diversity [Dβ1]-joining [Jβ1]) and all cells (constant region 2 [Cβ2]). (C) Validation of oligonucleotide specificity for detecting TCRβ rearrangement. Only cells that have not undergone TCR rearrangement present intact Dβ1-Jβ1 primer-binding regions and will result in a 143-bp amplicon (designated Dβ1). The Cβ2 primers resulted in a 218-bp amplicon since this region remains intact at the DNA level during V(D)J recombination. The RPP30 primers resulted in a 62-bp amplicon of all samples containing human gDNA. NTC, nontemplate control. (D) A one-dimensional (1-D) ddPCR profile on Ch1 demonstrates the Dβ1 primer specificity to amplify samples containing non-T cells or cells that have not undergone V(D)J recombination (HEK and PBMC) (Dβ1+, blue droplets; Dβ1−, black droplets); the Ch2 1-D profile targets the ubiquitous housekeeping gene, RPP30 (RPP30+, green droplets; RPP30−, black droplets), which allows absolute quantification of total cells. Amplitude threshold is represented with a pink line. (E) Comparison of T-cell quantification by FACS to that by ddPCR. Determined T-cell fractions of 18 healthy PBMC donors are plotted jointly for direct comparison of the two quantification methods. Bars indicate mean values with SDs (FACS, 29 ± 18.6; ddPCR, 26 ± 17.6) (Wilcoxon matched-pairs test, P = 0.6705; ns, nonsignificant).

Recently, a novel single duplex ddPCR assay was developed and validated for quantifying T cells by measuring the loss of germ line T-cell receptor loci, which resulted in accurate measurement of the T-cell population compared with the gold standard method of flow cytometry (26). The dynamic range of this technique makes certain that even low proportions of T cells are accurately detected. In contrast to other techniques (flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry, and real-time quantitative PCR), the digital design of ddPCR offers direct quantification and requires small amounts of DNA derived from fresh, frozen, or fixed samples. This is particularly advantageous in a remote community setting where large distances and poor access to resources make it difficult to maintain cell viability of clinical samples, which often vary considerably in quantity and quality. Here we describe a novel application of the recently introduced duplex ddPCR assay to quantify T cells from various sources of human genomic DNA (gDNA) extracted from frozen material such as blood/PBMCs and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and sputum samples obtained ethically from a remote Indigenous Australian HTLV-1 cohort.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primary cells.

Whole-blood samples from HTLV-1c patients were collected from adult subjects (age ≥ 18 years) who were recruited >48 h after admission to Alice Springs Hospital, Northern Territory, central Australia, between 21 January 2012 and 8 November 2016. With ethics approval and patient consent in the primary language, frozen specimens consisting of 29 peripheral blood, 6 induced sputum, and 3 bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples from the remote Indigenous Australian cohort were sent to The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity at The University of Melbourne. Also, 14 healthy subjects from similar background were included as negative controls. gDNA was extracted using a GenElute blood genomic DNA kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to manufacturer’s instructions and eluted in EB buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) or RNA-free water. To ensure efficient gDNA extraction from sputum and BAL fluid, samples were supplemented with carrier DNA and treated for 3 h at 55°C with lysis buffer and proteinase K (200 μg). The purity of the isolated DNA A260/A280 ratio was measured by UV spectrophotometry (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, CA).

HTLV-1 serologic and molecular studies.

HTLV-1 serostatus was based on the detection of specific anti-HTLV-1 antibodies in serum by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (Murex HTLVI+II; DiaSorin, Saluggia, Italy) and the Serodia HTLV-1 particle agglutination assay (Fujirebio, Tokyo, Japan) performed by the National Serological Reference Laboratory, Melbourne, Australia.

ddPCR limit of detection of HTLV-1c gag and tax.

To evaluate the dynamic range and accuracy of quantifying HTLV-1 gene regions by ddPCR, a 1:5 serial dilution of plasmids containing HTLV-1c viral targets (pCRII-HTLV1c-gag and pCRII-HTLV1c-tax) were used to determine the lower and upper limit of detection (LoD). The standard curve was performed in duplicate as independent experiments, resulting in partitioning of approximately 40,000 droplets. Where the data points stray from linearity represents the lower and upper LoD.

ddPCR limit of detection of non-T cells.

To evaluate the dynamic range and accuracy of quantifying T cells by ddPCR, a 1:5 serial dilution of gDNA isolated from non-T cells (HEK 293T) and T cells (CEM) (each at 6 × 106/ml) was used to determine the lower and upper LoD in measuring the number of unrearranged TCRβ gene regions. CEM T cells were added to each well to maintain normalized levels of gDNA throughout the assay. The intact TCRβ gene region spanning across the Dβ1 and Jβ1 region was measured in duplicate for each sample on 3 separate occasions.

ddPCR HTLV-1 PVL measurements.

To quantify the PVL accurately, primers (900 nM) and 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-conjugated hydrolysis probes (250 nM) specific to a conserved HTLV-1c gag or tax gene were developed (Table 1). Probes targeting the provirus were labeled with FAM (Applied Biosystems), whereas the probe directed at reference gene RPP30 (RNase P/MRP subunit P30, dHsaCPE5038241; Bio-Rad) was labeled with 6-carboxy-2,4,4,5,7,7-hexachlorofluorescein (HEX). All primers and probes were designed for ddPCR and cross-checked with binding sites against the human genome to ensure target specificity of the generated primer pairs (Primer-BLAST; NCBI). A temperature optimization gradient ddPCR assay was performed to determine the optimal annealing temperature of primers targeting HTLV-1 gag and tax (data not shown). ddPCR was performed using ddPCR Supermix for probes (no dUTP; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) in 22 μl with 50 to 100 ng of gDNA. Following droplet generation (15,000 to 18,000, on average) using a QX-200 droplet generator, droplets were transferred to a 96-well plate (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY), heat sealed with pierceable sealing foil sheets (Thermo Fisher Scientific, West Palm Beach, FL), and amplified using a C1000 Touch thermocycler (Bio-Rad) with a 105°C heated lid. Cycle parameters were as follows: enzymatic activation for 10 min at 95°C; 40 cycles of denaturation for 30 s at 94°C and annealing and extension for 1 min at 58°C, enzymatic deactivation for 10 min at 98°C, and infinite hold at 10°C. All cycling steps utilized a ramp rate of 2°C/s. Droplets were analyzed with a QX200 droplet reader (Bio-Rad) using a two-channel setting to detect FAM and HEX. The positive droplets were designated based on the no-template controls (NTC) and fluorescence-minus-one (FMO) controls (HTLV-1− RPP30+, HTLV-1+ RPP30−, and HTLV-1+ RPP30+) using gDNA extracted from healthy donors, HTLV-1c tax plasmid (pcRII-tax), and MT4 gDNA, which were included in each run. While our primers are specific for HTLV-1c, they work efficiently in detecting HTLV-1a from the MT4 cell line (18).

TABLE 1.

Details for primers and probes used for ddPCR quantification of HTLV-1c and T cellsa

| Oligonucleotide | Strand | Sequence (5′→3′) | Annealing temp (°C) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primers for ddPCR for HTLV-1c and RPP30 primers | ||||

| 3083 | + | CAAATGAAGGACCTACAGGC | 58 | Production of HTLV-1c gag fragment |

| 3084 | − | TATCTAGCTGCTGGTGATGG | 61 | Production of HTLV-1c gag fragment |

| 3085 | + | TCCAGGCCTTATTTGGACAT | 59 | Production of HTLV1c tax fragment |

| 3086 | − | CGTGTGAGAGTAGGACTGAG | 59 | Production of HTLV1c tax fragment |

| Probes for ddPCR for HTLV-1c and RPP30 | ||||

| 3321c | + | FAM-ACCATCCGGCTTGCAGT-MGBNFQb | 58 | Detection of HTLV-1c gag |

| 3318c | − | FAM-CATGATTTCCGGGCCTTGC-MGBNFQ | 61 | Detection of HTLV-1c tax |

| Primers for ddPCR for TCRβ gene region | ||||

| 3095 | + | TGTACAAAGCTGTAACATTGTGGGGAC | 61 | Amplification of TCRβ exon 1 of diverse region 1 |

| 3096 | − | AACCAAATTGCATTAAGACCTGTGACC | 60 | Amplification of TCRβ upstream intron of joining region 1 |

| 3157 | + | TCCGGTAAGTGAGTCTCTCC | 55 | Detection of TCRβ constant region 2 |

| 3158 | − | ATACAAGGTGGCCTTCCCTA | 55 | Detection of TCRβ constant region 2 |

| Probes for ddPCR for TCRβ gene region | ||||

| 3191c | + | ACAATGATTCAACTCTACGGGAAACC | 59 | Detection of TCRβ exon 1 of diverse region 1 |

| 3159c | − | CGTGAGGGAGGCCAGAGCCACCTG | 68 | Detection of TCRβ constant region 2 |

Working concentration (WC), 20 μM.

MGBNFQ, minor groove binding nonfluorescent quencher.

TaqMan probe.

ddPCR T-cell measurements.

Methods to quantify T cells accurately using the duplex ddPCR assays have been previously described by Zoutman et al. (26). However, different primers and probes were utilized in this study (Table 1). Probes directed at the intact TCRβ gene region, which represents a cell that has not undergone V(D)J recombination and spanning across 143 bp of the Dβ1-Jβ1 region, were labeled with FAM, whereas probes directed at the internal reference gene RPP30 were labeled with HEX to quantify the total number of cells (Table 1). Additional primers and probes were specifically designed to span 218 bp of the TCRβ constant region 2 (Cβ2) and used as a positive control (Table 1). The final concentrations of each primer and probe used in the ddPCR were 900 nM and 250 nM, respectively. A temperature optimization gradient assay was performed to determine the optimal annealing temperature of primers targeting TCRβ gene regions (data not shown). ddPCR was performed as previously described, but the cycle parameters were as follows: enzymatic activation for 10 min at 95°C; 50 cycles of denaturation for 30 s at 94°C, annealing, and extension for 1 min at 60°C; enzymatic deactivation for 10 min at 98°C, and infinite hold at 10°C.

ddPCR HTLV-1 PVL data analysis.

QuantaSoft software version 1.7.4 (Bio-Rad) was used to quantify and normalize the copies per microliter of each target per well. To address the HTLV-1-infected samples, which might be at or below the LoD, calculation of proviral copy number was normalized to the lower LoD of the PVL assay (65 copies per 106 cells). Amplitude fluorescence thresholds were manually determined according to the negative controls (nontemplate control and DNA from healthy PBMCs), which had been included in each run. Droplet positivity was measured by fluorescence intensity above a minimum amplitude threshold. All samples were run in duplicate, and the HTLV-1 PVL was determined as the mean of the two measurements. The HTLV-1 PVL per genome was calculated based on the concentration of HTLV-1 target gene, either gag or tax, and expressed as proviral copies per microliter, and divided by the copies of RPP30 diploid genome. The quotient is then multiplied by a chosen unit of cells designated 1 × 106 cells.

| (1) |

ddPCR T-cell data analysis.

Quantification and normalization of number of T cells have been previously described (26). Briefly, to address the HTLV-1c-infected samples, which might be at or below the LoD, calculation of the number of T cells in each sample was normalized to the lower LoD of the unrearranged T-cell receptor (UTCR) assay (98 copies per 106 T cells). All samples were run in duplicate to quantify the absolute mean number of intact Dβ/Jβ regions, or non-T cells, which represents a cell that has not undergone V(D)J recombination. As previously described by Zoutman et al., the total number of non-T cells is quantified absolutely by ddPCR and then subtracted from the total number of cells to arrive at the total T-cell fraction. From this, the HTLV-1c PVL per T cell was calculated based on the corresponding HTLV-1 PVL per genome values targeting gag or tax and defined as the HTLV-1 proviral copies per 106 T cells. The contribution of T cells to the PVL is calculated in the following manner by dividing the HTLV-1 PVL per genome by the copy number of T cells:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Flow cytometry.

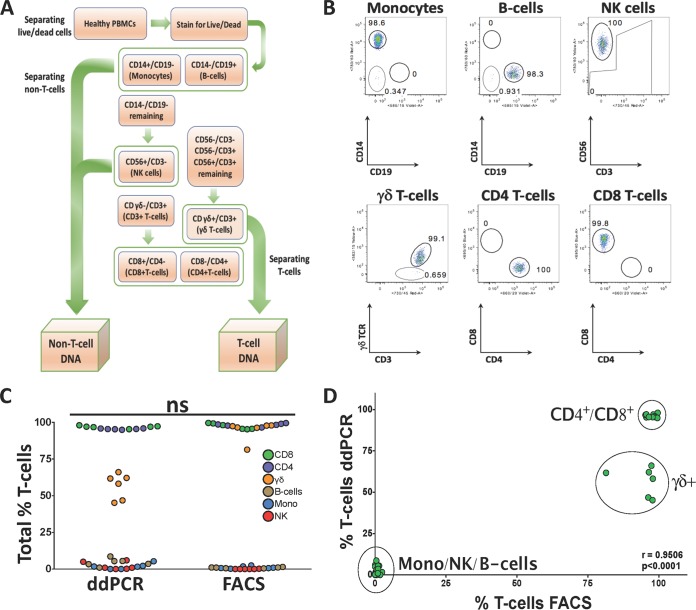

Flow cytometry was performed on frozen PBMCs isolated from buffy coats (Australian Red Cross Blood Service, West Melbourne, Australia). Cryopreserved cells were rapidly thawed at 37°C and added dropwise to thawing media containing fresh complete RPMI (RPMI 1640 medium [Gibco Invitrogen Cell Culture, Grand Island, NY]) with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Bovogen Biologicals, East Keilor, VIC, Australia), 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 μM minimum essential medium (MEM) with nonessential amino acids, and 5 mM HEPES buffer (all from Gibco), 55 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA), 100 U/ml of penicillin and 100 U/ml of streptomycin (both from Gibco), and benzonase (50U/ml) (Novagen, ED Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA). Cells were then centrifuged at room temperature for 6 min at 500 × g, counted and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then stained with LIVE/DEAD aqua (Molecular Probes for Life Technologies) to exclude potential autofluorescence from dead cells. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and stained with a combination of anti-CD3 Alexa Fluor 700 (UCHT1), anti-CD4 BV650 (SK3), anti-CD8 peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)-Cy5.5 (SK1), anti-CD14 allophycocyanin (APC)-H7 (MΦP9), anti-CD56 phycoerythrin (PE)-Cy7 (NCAM16.2), anti-TCRγδ-1 PE (11F2), and anti-CD19 BV711 (SJ25C1) (all from BD Biosciences) (PBS with 0.1% bovine serum albumin; Gibco for Life Technologies). After washing twice with sort buffer, cells were resuspended and passed through a 70-μm sieve and acquired by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS; BD FACS Aria Fusion, BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA) to isolate live populations of non-T cells (natural killer [NK] cells, B cells, and monocytes), T cells (CD8+, CD4+, and γδ+). The flow gating strategy to sort non-T-cell and T-cell populations was as follows: live non-T-cell populations of B cells (CD19+ CD14−), monocytes (CD14+ CD19−), and NK cells (CD14− CD19− CD56+ CD3−) and then live T-cell populations of γδ+ T cells (CD14− CD19− CD3+ TCRγδ+), CD4+ T cells (CD14− CD19− CD3+ TCRγδ− CD4+), and CD8+ T cells (CD14− CD19− CD3+ TCRγδ− CD8+) (Fig. 2A). After sorting the samples into respective populations, a purity check for each population was performed. Gates were carefully chosen to reduce the selection of unspecific cellular populations (Fig. 2B). Data were analyzed with FlowJo version 9.7.6 (Tree Star) software.

FIG 2.

Comparison of T-cell quantifications between ddPCR and flow cytometry in sorted cellular populations. (A) Flowchart of FACS sorting strategy. PBMC samples from 6 healthy donors were sorted into non-T-cell (NK cells, monocytes, and B cells) and T-cell populations (CD8+, CD4+, and γδ), followed by DNA extraction. (B) Purity checks of the various sorted cellular populations. (C) Total fraction of T cells measured in each sorted population from healthy donors by ddPCR and FACS. The distributions of measured cell subsets were very similar, which did not result in a significant difference between the ddPCR and FACS assays (P = 0.7559, Mann-Whitney test). (D) Correlation of ddPCR- and FACS-measured T cells in sorted populations of T cells and non-T cells from healthy donors resulted in a positive correlation (P < 0.0001; r = 0.9506).

Statistical analysis.

GraphPad Prism version 6 softward (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical analysis. To evaluate linear association in the fraction of T cells measured between ddPCR and flow cytometry, linear regression and standard Pearson r tests were performed. T-cell quantification data from healthy and HTLV-1c-infected cohort samples were depicted as dot plots and tested for differences in median counts by Kruskal-Wallis testing with a confidence interval of 95%. The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare unpaired samples, and paired t test was used to compare paired specimens (blood, BAL fluid, and sputum). A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Quantification of T cells by measuring the unrearranged T-cell receptor DNA.

During early stages of T-cell maturation, rearrangements of Dβ1-Jβ1 intergenic sequences occur at both alleles, resulting in deletion of these sequences in nearly all peripheral T cells (21). In contrast, TCRβ constant region 2 (Cβ2) remains intact during V(D)J recombination. By measuring the loss of these specific TCRβ loci by ddPCR and normalizing against a stable reference gene, such as the RPP30 gene, enables a quantification of the number of T cells in a clinical sample. On this basis, we designed a set of primer-probes that target the intact TCRβ gene region spanning across 143 bp of the Dβ1 exon and Jβ1 intron (Fig. 1B). An additional primer-probe set were specifically designed to span 218 bp of the Cβ2 region and used as a positive control (Table 1). We validated our chosen Dβ1-Jβ1 target sequence for the detection of cells that had not undergone the V(D)J recombination and thus were not capable of functioning as T cells using several different cell sources with various T-cell compositions. As expected, only cells that had not undergone T-cell rearrangement, such as HEK293T cells and a subset of PBMCs comprising macrophages, monocytes, and NK and B cells with intact primer binding regions, resulted in a specific Dβ1-Jβ1 amplification (Fig. 1C). On the other hand, T-cell lines MT4 and CEM, which had clonally rearranged TCR genes, failed to amplify the deleted TCR segment. All samples resulted in Cβ2 amplification since this region remains intact during V(D)J recombination. Similarly, the results of a multiplexed ddPCR confirmed that the amplification with Dβ/Jβ (CH1 and FAM) is restricted to samples containing non-T cells that have not undergone V(D)J recombination, while the RPP30 reference gene (CH2 and HEX) was detected for all samples (Fig. 1D).

We validated this novel ddPCR assay against the gold standard flow cytometry method for T-cell measurement using CD3+ surface staining by comparing the ddPCR and the FACS determinations of the T-cell fraction from 18 healthy donor PBMC samples with various levels of circulating T cells (Fig. 1E). No significant differences (P = 0.6705, Wilcoxon matched-pairs test) in the frequency of CD3+ T cell fractions were detected between FACS (29.0% ± 18.6%) and ddPCR (26.5% ± 17.6%), confirming the specificity and accuracy in detecting unrearranged TCRβ and thus T cells.

High accuracy and dynamic range of detecting unrearranged T-cell receptor DNA by ddPCR technology.

To evaluate the dynamic range of our unrearranged T-cell receptor (UTCR) assay, DNA isolated from non-T cells (HEK293T) was serially diluted into T-cell DNA (CEM cells) and evaluated by ddPCR with 4 replicates per sample. A comparison between the observed with the expected number of copies provided an estimation of the assay accuracy. The slope for the observed UTCR copy number (x: 0.808 ± 0.01) was significantly close to the expected UTCR copy number (y: 1.00 ± 0.0) (Fig. S1) (R = 0.9913, P < 0.0001). The dynamic range of ddPCR from 1.56 to 105 UTCR copies per well ensures sensitive and accurate detection of UTCR DNA, as indicated by the small 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The ddPCR lower and upper limits of detection (LoD) for the UTCR assay were determined at 97.9 and 2 × 105 copies per 106 cells, respectively.

Comparison of T-cell quantifications in sorted cellular populations between ddPCR and flow cytometry resulted in positive correlation.

To further validate the assay utilized to calculate the T-cell population in gDNA of frozen samples, we compared measurements of FACS-sorted cell populations by flow cytometry and ddPCR. To perform this, we obtained PBMCs from healthy donors (n = 6) and isolated various T-cell subsets (CD8+, CD4+, and γδ+) and non-T-cell subsets (natural killer [NK] cells, monocytes, and B cells) by cell sorting based on expression of lineage-specific phenotypic markers as depicted in Fig. 2A. The purity checks resulted in ≥90% purity in most sorted populations, which reflects the overall homogeneity in each sorted group (Table 1). Two of the sorted healthy PBMC samples resulted in lower purity of γδ+ T-cell populations, number 5 (55.2%) and number 6 (65.1%), reflecting possible downregulation of the γδ TCR or photobleaching during the sorting process. Lower purity was also noted in two of the sorted monocyte populations, number 3 (78.5%) and number 6 (77.7%), which could be attributed in part to the adherent nature of these larger cells, which can result in adhesion to smaller cells despite attempts to gate out doublet cells. The percentage of T cells measured by ddPCR in the T-cell populations was equivalent to the one determined by flow cytometry (Fig. 2C) (not significant [ns], P = 0.7559, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test), which supports the functionality and the sensitivity of the UTCR assay to specifically detect and quantify T-cell populations. Moreover, the sorted non-T-cell population resulted in 0.0% to 8.6% total T cells, matching the percentage of purity observed by FACS (Table 1), which demonstrates the ability of the UTCR assay to accurately detect unrearranged TCRβ chain (Fig. 2D) (P < 0.0001, r = 0.9506, Pearson r test) and thus the sorting efficiency and purity of T cells from gDNA. The proportion of γδ+ T cells determined by FACS was 55.2% to 97%, while the ddPCR results ranged from 46.8% to 66% (Table 2). The 30% discrepancy between the flow cytometry and UTCR assay suggests that not all γδ+ T cells have fully rearranged TCRβ alleles.

TABLE 2.

Purity check of FACS-sorted cell populations and percent T cells measured by ddPCR

| Cell type | % purity of FACS-sorted population | % T cells in ddPCR measure | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T cell | PBMC1 | PBMC2 | PBMC3 | PBMC4 | PBMC5 | PBMC6 | PBMC1 | PBMC2 | PBMC3 | PBMC4 | PBMC5 | PBMC6 |

| CD8+ | 98.7 | 97.2 | 95.8 | 92.8 | 93.2 | 91.3 | 97.3 | 97.0 | 98.0 | 95.3 | 96.7 | 97.1 |

| CD4+ | 98.4 | 97.0 | 98.2 | 92.6 | 97.6 | 94.6 | 95.9 | 95.8 | 95.3 | 94.9 | 95.4 | 95.5 |

| γδ+ | 97.0 | 94.5 | 89.6 | 91.5 | 55.2 | 65.1 | 62.1 | 61.7 | 46.8 | 58.2 | 66.0 | 45.2 |

| Non-T cell | ||||||||||||

| NK cell | 99.5 | 99.9 | 99.0 | 95.1 | 94.4 | 95.3 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 5.9 | 4.9 | 0.2 |

| Monocyte | 92.9 | 89.5 | 78.5 | 93.9 | 92.5 | 77.7 | 1.6 | 5.3 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 0.0 |

| B cell | 96.4 | 92.1 | 90.9 | 97.7 | 94.0 | 94.7 | 3.3 | 5.5 | 8.6 | 5.4 | 3.5 | 1.0 |

Application of the UTCR assay in a remote Indigenous Australian HTLV-1c cohort.

We next examined the ability of the UTCR assay to quantify T cells from various sources of HTLV-1 patient samples. To do this, we obtained frozen samples consisting of peripheral blood (n = 29), induced sputum (n = 6), and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid (n = 3) from the Alice Springs Hospital-based Indigenous Australian HTLV-1 cohort, as well as blood samples from healthy donors of similar background (n = 14). Participant characteristics and results are summarized in Table S1 and Table S2. The collection dates of the samples ranged from 21 January 2012 to 8 November 2016. The overall distribution of samples by gender was 22 males (57.9%) and 14 females (36.8%), with 2 unknown samples. The average age at time of sample collection was not significantly different between males (46.4 ± 2.9 years) and females (48.6 ± 2.3 years) (P = 0.2718, unpaired t test).

Given that HTLV-1 preferentially infects CD4+ T cells, we hypothesized that the HTLV-1 PVL per T cells would be higher in comparison with the PVL per genome since the latter includes all potential cellular targets of HTLV-1 infection and thus would dilute the PVL measurement. Collectively, the 38 samples resulted in a significant difference between the HTLV-1c PVL per genome and PVL per T-cell assays (Fig. 3A) (P < 0.0001, two-tailed paired t test), which indicates that the HTLV-1 PVL per T-cell assay quantifies a specific HTLV-1-targeted cellular population that could be relevant to the assessment of increased risk of HTLV-1 disease progression.

FIG 3.

Relative distribution of HTLV-1c PVL measured in peripheral blood and various exudates from a remote Indigenous Australian cohort. HTLV-1c PVL per genome and PVL per T cell were measured in HTLV-1c-infected (+ve) peripheral blood (red), induced sputum (green), and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL; blue) samples from remote Indigenous Australian cohort participants. PBMCs from healthy indigenous volunteers (−ve) were used as a negative control (open black circles). Box mid-line represents median value with interquartile range. Three subjects, represented by triangles, squares, and diamonds, donated both blood and sputum samples. Isolated gDNA from one BAL and one sputum sample was insufficient for PVL per T-cell assay. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Next we investigated whether the HTLV-1 PVL was consistent between these sources of infected blood and various inflammatory exudates (Fig. 3B). The median and interquartile range (IQR) for HTLV-1c PVL per genome and PVL per T cell in peripheral blood were 5.6 × 103 copies (IQR, 1.8 × 103, 1.0 × 104) (per 106 cells) and 6.7 × 104 copies (IQR, 2.4 × 104, 1.2 × 105) (per 106 T cells), respectively. The median and IQR for HTLV-1c PVL per genome and PVL per T cell in BAL fluid were 1.3 × 105 copies (IQR, 1.2 × 103, 1.4 × 105) (per 106 cells) and 1.2 × 106 copies (IQR, 1.0 × 106, 1.3 × 106) (per 106 T cells) and 754.0 copies (IQR, 64.8, 6.1 × 103) (per 106 cells) and 2.3 × 104 copies (IQR, 97.8, 5.0 × 104) (per 106 T cells), respectively, in the induced sputum.

We observed a significantly higher mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of HTLV-1c PVL per genome in blood (1.1 × 104 ± 3.1 × 103 copies per 106 cells) than in induced sputum (2.4 × 103 ± 1.3 × 103 copies per 106 cells; P = 0.0388, unpaired t test). We also observed a significantly higher mean ± SEM HTLV-1c PVL per T cell in blood (9.4 × 104 ± 1.7 × 104 copies per 106 T cells) than in induced sputum (2.0 × 104 ± 1.7 × 104 copies per 106 T cells; P = 0.0133, unpaired t test). Overall, the mean PVL per genome and PVL per T cell in blood were approximately 4 and 5 times greater than in sputum, respectively.

We also observed that the mean ± SEM HTLV-1c PVL per genome was higher in BAL fluid (9.0 × 104 ± 4.5 × 104 copies per 106 cells) than in blood samples, although this result was not significant. However, the mean ± SEM HTLV-1c PVL per T cell in BAL fluid (1.2 × 106 ± 1.6 × 105 copies per 106 T cells) was significantly higher than that of blood samples (P = 0.0043, unpaired t test). The mean PVL per genome and PVL per T cell in BAL samples were approximately 9 and 13 times higher than blood, respectively.

Finally, we observed that the mean ± SEM HTLV-1c PVL per genome and PVL per T cell in induced sputum (2.4 × 103 ± 1.3 × 103 copies per 106 cells and 2.0 × 104 ± 1.7 × 104 copies per 106 T cells, respectively) were lower than that of BAL samples, although neither result reached statistical significance. The PVL per genome and PVL per T cell in BAL samples were 38 and 57 times higher than in induced sputum samples, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have shown that quantitative PCR (qPCR) and ddPCR are both capable of distinguishing clinically significant differences in T-cell proportions and perform similarly to FACS (27). However, ddPCR technology results in a high-throughput digital PCR with several advantages over qPCR (28, 29). Unlike qPCR, ddPCR provides an absolute count of target copies independent of an extrapolation from a standard curve, which greatly reduces variability between assays and difficulty in measuring PVL, particularly from samples with low numbers of cells (30, 31). Direct measurement of target DNA is optimal for viral load analysis, and when combined with the massive sample partitioning afforded by ddPCR, a greater precision and reliability can be achieved (32).

We have demonstrated and validated a novel application of the ddPCR assay to accurately measure T cells in HTLV-1-infected peripheral blood and inflammatory exudates. Specifically, we provided evidence from a remote Indigenous Australian HTLV-1c cohort that the viral burden expressed as the proportion of target T cells varies between compartments. Collectively, we found a significant difference between HTLV-1 PVL per genome and PVL per T cell, indicating that the HTLV-1 PVL per T-cell assay quantifies a specific HTLV-1-targeted cellular population that could be relevant to the assessment of increased risk of HTLV-1 disease progression. A higher HTLV-1 proviral burden resides in cells extracted from BAL samples than from peripheral blood. Given that most T cells infected in vivo harbor a single provirus, the high PVL per deduced number of T cells in BAL samples suggests that almost 100% of T cells are infected by HTLV-1. Alternatively, it could also suggest that HTLV-1c has infected into macrophages, B cells, or other non-T cells of the respiratory tract in the bronchiectasis patients from whom BAL fluid was sampled. Either of these interpretations may address the pathogenesis of HTLV-1c-associated bronchopulmonary disease. Previous studies have shown that the lymphocyte composition of BAL fluid from HTLV-1-associated bronchiectasis ranges from 2% to 30%, whereas BAL fluid from HTLV-1-associated HAM ranges from 21% to 72%, with myeloid cells making up the bulk of the remainder (33). The BAL samples used in this study were obtained for microbial analysis and were not examined by microscopy for cellularity before they were frozen in a manner that lysed cells. Any future BAL sampling from this patient population should include an ethical collection of viable cells for flow cytometric sorting of pure T-cell, B-cell, and myeloid cell populations to examine the cellular source of the HTLV-1 provirus in the inflammatory exudate associated with bronchiectasis during an HTLV-1 infection (34). It is probable that measurement of HTLV-1 PVL in specific compartments, such as the lungs, may be a superior indicator for progression of HTLV-1c-associated lymphoproliferative respiratory diseases such as bronchiectasis (11).

Given the difficulty in collecting clinical material from a remote community setting, there are several limitations in this study, such as the limited number of subjects who provided pulmonary secretions. Further work is necessary to confirm our findings in larger studies in central Australia. It is also critical to compare PVLs from different compartments in the same individual given that wide variability in peripheral blood PVLs exists between individuals, which could complicate comparisons between groups and the use of PVL as a prognostic tool. In addition, low cell numbers are more likely to explain why we measured such low PVLs in the induced sputum. The ranges of cells and T cells for sputum samples were 264.5 to 640.5 and 13.0 to 74.5, respectively. While the sputum cell numbers were low compared to those in BAL samples, the BAL fluid was only collected during procedures under the setting of intensive care, making BAL samples unsuitable for monitoring of HTLV-1 involvement in lung disease. Given that most T cells infected in vivo harbor a single provirus, the high PVL per T cells in BAL samples suggests nearly 100% HTLV-1 infectivity, which may address the pathology of the infection. Unfortunately, the samples we have used to measure HTLV-1c PVL are all gDNA derived from frozen blood or BAL samples, which means that they are no longer viable and unsuitable for single-cell sorting. Future experiments, such as PCR on isolated T cells, are needed to confirm these findings. A further limitation results from the lack of clinical history of these subjects. Without this information, potential complications, such as pulmonary disease or infective exacerbation during sample collection, could influence our results.

In conclusion, our data support the application of the ddPCR assay to count T cells from DNA specimens from various compartments, and this assay has potential clinical and diagnostic applications in the sharply focused longitudinal monitoring of HTLV-1 PVL and risk assessment of HTLV-1-associated inflammatory diseases. Furthermore, this assay has translational applications in the validation of cell purity following isolation of CD4+, CD8+, and γδ+ T cells, as well as B cells, NK cells, and monocytes. In order to fully explore the applications of this UTCR assay, it will be essential to conduct larger HTLV-1 case-controlled studies and experimentally address how the viral burden in specific compartments correlates with HTLV-1-associated disease pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We sincerely thank all the remote Indigenous Australian community members who participated in this study. We also thank members of the scientific community who generously shared reagents critical to this work. We acknowledge Kim Wilson of the National Reference Laboratory of Melbourne, Australia, and gratefully acknowledge the support of the Pathology Department at Alice Springs Hospital. We also thank the DMI Flow Facility staff for their advice and generous assistance during the sorting experiments.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Central Australian Human Research Ethics Committee. All patients were informed in first language and gave written informed consent in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (HREC-14-249). The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study relates to Indigenous Australians and cannot be accessed without appropriate ethics approval from the Central Australian Human Research Ethics Committee for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data (cahrec@flinders.edu.au).

We declare that we have no competing interests.

This study was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) program grant number 1052979 to D.P. and program grant number 1071916 to K.K. K.K. is a NHMRC Senior Research Level B Fellow (1102792), and B.C. is a NHMRC Peter Doherty Fellow.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01063-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gessain A, Cassar O. 2012. Epidemiological aspects and world distribution of HTLV-1 Infection. Front Microbiol 3:388. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Einsiedel LJ, Pham H, Woodman RJ, Pepperill C, Taylor KA. 2016. The prevalence and clinical associations of HTLV-1 infection in a remote Indigenous community. Med J Aust 205:305–309. doi: 10.5694/mja16.00285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verdonck K, Gonzalez E, Van Dooren S, Vandamme AM, Vanham G, Gotuzzo E. 2007. Human T-lymphotropic virus 1: recent knowledge about an ancient infection. Lancet Infect Dis 7:266–281. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poiesz BJ, Ruscetti FW, Gazdar AF, Bunn PA, Minna JD, Gallo RC. 1980. Detection and isolation of type C retrovirus particles from fresh and cultured lymphocytes of a patient with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 77:7415–7419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gessain A, Barin F, Vernant JC, Gout O, Maurs L, Calender A, de Thé G. 1985. Antibodies to human T-lymphotropic virus type-I in patients with tropical spastic paraparesis. Lancet ii:407–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamoi K, Mochizuki M. 2012. HTLV-1 uveitis. Front Microbiol 3:270. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eguchi K, Matsuoka N, Ida H, Nakashima M, Sakai M, Sakito S, Kawakami A, Terada K, Shimada H, Kawabe Y. 1992. Primary Sjogren’s syndrome with antibodies to HTLV-I: clinical and laboratory features. Ann Rheum Dis 51:769–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishioka K, Maruyama I, Sato K, Kitajima I, Nakajima Y, Osame M. 1989. Chronic inflammatory arthropathy associated with HTLV-I. Lancet i:441. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90038-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan OS, Rodgers-Johnson P, Mora C, Char G. 1989. HTLV-1 and polymyositis in Jamaica. Lancet ii:1184–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakagawa M, Izumo S, Ijichi S, Kubota H, Arimura K, Kawabata M, Osame M. 1995. HTLV-I-associated myelopathy: analysis of 213 patients based on clinical features and laboratory findings. J Neurovirol 1:50–61. doi: 10.3109/13550289509111010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Einsiedel L, Cossar O, Goeman E, Spelman T, Au V, Hatami S, Joseph S, Gessain A. 2014. High HTLV-1 subtype C proviral loads are associated with bronchiectasis in Indigenous Australians: results of a case-control study. Open Forum Infect Dis 1(1):ofu023. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofu023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Einsiedel L, Cassar O, Spelman T, Joseph S, Gessain A. 2016. Higher HTLV-1c proviral loads are associated with blood stream infections in an Indigenous Australian population. J Clin Virol 78:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furtado MDSBS, Andrade RG, Romanelli LCF, Ribeiro MA, Ribas JG, Torres EB, Barbosa-Stancioli EF, Proietti ABDFC, Martins ML. 2012. Monitoring the HTLV-1 proviral load in the peripheral blood of asymptomatic carriers and patients with HTLV-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis from a Brazilian cohort: ROC curve analysis to establish the threshold for risk disease. J Med Virol 84:664–671. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuzaki T, Nakagawa M, Nagai M, Usuku K, Higuchi I, Arimura K, Kubota H, Izumo S, Akiba S, Osame M. 2001. HTLV-I proviral load correlates with progression of motor disability in HAM/TSP: analysis of 239 HAM/TSP patients including 64 patients followed up for 10 years. J Neurovirol 7:228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamano Y, Nagai M, Brennan M, Mora CA, Soldan SS, Tomaru U, Takenouchi N, Izumo S, Osame M, Jacobson S. 2002. Correlation of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) mRNA with proviral DNA load, virus-specific CD8(+) T cells, and disease severity in HTLV-1-associated myelopathy (HAM/TSP). Blood 99:88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwanaga M, Watanabe T, Utsunomiya A, Okayama A, Uchimaru K, Koh KR, Ogata M, Kikuchi H, Sagara Y, Uozumi K, Mochizuki M, Tsukasaki K, Saburi Y, Yamamura M, Tanaka J, Moriuchi Y, Hino S, Kamihira S, Yamaguchi K, Joint Study on Predisposing Factors of ATL Development investigators. 2010. Human T-cell leukemia virus type I (HTLV-1) proviral load and disease progression in asymptomatic HTLV-1 carriers: a nationwide prospective study in Japan. Blood 116:1211–1219. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-257410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagai M, Usuku K, Matsumoto W, Kodama D, Takenouchi N, Moritoyo T, Hashiguchi S, Ichinose M, Bangham CR, Izumo S, Osame M. 1998. Analysis of HTLV-I proviral load in 202 HAM/TSP patients and 243 asymptomatic HTLV-I carriers: high proviral load strongly predisposes to HAM/TSP. J Neurovirol 4:586–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunetto GS, Massoud R, Leibovitch EC, Caruso B, Johnson K, Ohayon J, Fenton K, Cortese I, Jacobson S. 2014. Digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) for the precise quantification of human T-lymphotropic virus 1 proviral loads in peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid of HAM/TSP patients and identification of viral mutations. J Neurovirol 20:341–351. doi: 10.1007/s13365-014-0249-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zinkernagel RM, Doherty PC. 1974. Restriction of in vitro T cell-mediated cytotoxicity in lymphocytic choriomeningitis within a syngeneic or semiallogeneic system. Nature 248:701–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tonegawa S. 1983. Somatic generation of antibody diversity. Nature 302:575–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dik WA, Pike-Overzet K, Weerkamp F, de Ridder D, de Haas EF, Baert MR, van der Spek P, Koster EE, Reinders MJ, van Dongen JJ, Langerak AW, Staal FJ. 2005. New insights on human T cell development by quantitative T cell receptor gene rearrangement studies and gene expression profiling. J Exp Med 201:1715–1723. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hesslein DG, Schatz DG. 2001. Factors and forces controlling V(D)J recombination. Adv Immunol 78:169–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livak F, Schatz DG. 1996. T-cell receptor alpha locus V(D)J recombination by-products are abundant in thymocytes and mature T cells. Mol Cell Biol 16:609–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breit TM, Verschuren MC, Wolvers-Tettero IL, Van Gastel-Mol EJ, Hählen K, van Dongen JJ. 1997. Human T cell leukemias with continuous V(D)J recombinase activity for TCR-delta gene deletion. J Immunol 159:4341–4349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldsby RA, Goldsby RA. 2003. Immunology, 5th ed WH Freeman, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zoutman WH, Nell RJ, Versluis M, van Steenderen D, Lalai RN, Out-Luiting JJ, de Lange MJ, Vermeer MH, Langerak AW, van der Velden PA. 2017. Accurate quantification of T cells by measuring loss of germline T-cell receptor loci with generic single duplex droplet digital PCR assays. J Mol Diagn 19:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiencke JK, Bracci PM, Hsuang G, Zheng S, Hansen H, Wrensch MR, Rice T, Eliot M, Kelsey KT. 2014. A comparison of DNA methylation specific droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) and real time qPCR with flow cytometry in characterizing human T cells in peripheral blood. Epigenetics 9:1360–1365. doi: 10.4161/15592294.2014.967589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayden RT, Gu Z, Ingersoll J, Abdul-Ali D, Shi L, Pounds S, Caliendo AM. 2013. Comparison of droplet digital PCR to real-time PCR for quantitative detection of cytomegalovirus. J Clin Microbiol 51:540–546. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02620-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strain MC, Lada SM, Luong T, Rought SE, Gianella S, Terry VH, Spina CA, Woelk CH, Richman DD. 2013. Highly precise measurement of HIV DNA by droplet digital PCR. PLoS One 8:e55943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hindson BJ, Ness KD, Masquelier DA, Belgrader P, Heredia NJ, Makarewicz AJ, Bright IJ, Lucero MY, Hiddessen AL, Legler TC, Kitano TK, Hodel MR, Petersen JF, Wyatt PW, Steenblock ER, Shah PH, Bousse LJ, Troup CB, Mellen JC, Wittmann DK, Erndt NG, Cauley TH, Koehler RT, So AP, Dube S, Rose KA, Montesclaros L, Wang S, Stumbo DP, Hodges SP, Romine S, Milanovich FP, White HE, Regan JF, Karlin-Neumann GA, Hindson CM, Saxonov S, Colston BW. 2011. High-throughput droplet digital PCR system for absolute quantitation of DNA copy number. Anal Chem 83:8604–8610. doi: 10.1021/ac202028g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee TH, Chafets DM, Busch MP, Murphy EL. 2004. Quantitation of HTLV-I and II proviral load using real-time quantitative PCR with SYBR Green chemistry. J Clin Virol 31:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinheiro LB, Coleman VA, Hindson CM, Herrmann J, Hindson BJ, Bhat S, Emslie KR. 2012. Evaluation of a droplet digital polymerase chain reaction format for DNA copy number quantification. Anal Chem 84:1003–1011. doi: 10.1021/ac202578x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mori S, Mizoguchi A, Kawabata M, Fukunaga H, Usuku K, Maruyama I, Osame M. 2005. Bronchoalveolar lymphocytosis correlates with human T lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I) proviral DNA load in HTLV-I carriers. Thorax 60:138–143. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.021667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyer KC, Raghu G, Baughman RP, Brown KK, Costabel U, Du Bois RM, Drent M, Haslam PL, Kim DS, Nagai S, Rottoli P, Saltini C, Selman M, Strange C, Wood B, American Thoracic Society Committee on BAL in Interstitial Lung Disease. 2012. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: the clinical utility of bronchoalveolar lavage cellular analysis in interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 185:1004–1014. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201202-0320ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.