The emergence of cell therapy programs in large academic centers has led to an increasing demand for clinical laboratories to assist with product sterility testing. Automated blood culture systems have shown promise as alternatives to the manual USP<71> compendial method, but current published data are limited by small organism test sets, particularly for molds.

KEYWORDS: Bactec, BacT/Alert, bacteria, blood culture systems, fungi, product, sterility testing, USP, molds

ABSTRACT

The emergence of cell therapy programs in large academic centers has led to an increasing demand for clinical laboratories to assist with product sterility testing. Automated blood culture systems have shown promise as alternatives to the manual USP<71> compendial method, but current published data are limited by small organism test sets, particularly for molds. In 2015, failure of the Bactec FX system to detect mold contamination in two products prompted us to evaluate three test systems (compendial USP<71>, Bactec FX, and BacT/Alert Dual-T) over seven different culture combinations, using 118 challenge organisms representative of the NIH current good manufacturing practice (cGMP) environment. At <96 h and <144 h for bacterial and fungal detection, respectively, the compendial USP<71> method significantly outperformed the Bactec FX system (84.7% versus 64.4%; P = 0.0006) but not the BacT/Alert system at 32.5°C (78.8%; P = 0.3116). Extended incubation to 360 h with terminal visual inspection improved sensitivity, without a significant difference between compendial USP<71> and BacT/Alert testing (95.7% versus 89.0%; P = 0.0860); both systems were better than the Bactec FX system (71.2%; P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0003, respectively). The Bactec FX and BacT/Alert systems performed equivalently for 30 isolates derived from clinical bloodstream infections, confirming system optimization for clinical organisms rather than environmental contaminants. Paired Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) plates were always positive for fungi within the acceptable time frame. This study shows that the Bactec FX system is suboptimal for product sterility testing, and it provides strong data to support the use of BacT/Alert testing at 32.5°C paired with a supplemental SDA plate as an acceptable alternative to the compendial USP<71> method for product sterility testing.

INTRODUCTION

Cellular therapy, gene therapy, and immunotherapy, together known as biopharmaceuticals, are increasingly important forms of treatment for previously incurable diseases, including various types of cancer and immunological diseases. Cell therapies are fast becoming the norm at academic centers, with many investigational new drugs in the clinical trial pipeline. Recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved two chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapies for the treatment of certain types of leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (1–3). Approval of such therapies is predicted to have a significant impact on hospital care systems and patient survival.

As part of current good manufacturing practice (cGMP), culture-based methods remain the gold standard to ensure the sterility of cell products prior to patient infusion, as regulated by the FDA (4), the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) (5), and the European Pharmacopoeia (6). USP chapter <71> (USP<71>) (5) remains the most common method used for product sterility testing in the biopharmaceutical industry in the United States. In this method, portions of in-process and/or final release product (with the inoculation volume being based on the batch size of the product, as defined in USP<71>) are inoculated into portions of tryptic soy broth (TSB) and fluid thioglyocollate (Thiol) broth and incubated at 20 to 25°C and 30 to 35°C, respectively, for 14 days (defined as <360 h in this study, to account for culture reads at any time point on day 14). Broths are manually inspected for turbidity during the incubation period and at its conclusion. A common observation schedule used in industry includes days 3, 7, and 14, but this can vary between laboratories. Per USP<71>, any broth turbidity triggers subculture into secondary TSB and/or Thiol broth, and then both the original and subculture broths are incubated for at least another 4 days prior to culture reporting, organism workup, and identification. Because USP<71> was originally designed for the testing of sterile soluble pharmaceuticals, rather than cellular biopharmaceuticals, culture interpretation is often difficult, subjective, and confounded by the natural turbidity of products with high cell densities. Another important component of USP<71> is test system qualification using 6 defined organisms (Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 9027, Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633, Clostridium sporogenes ATCC 19404, Candida albicans ATCC 10231, and Aspergillus brasiliensis ATCC 16404), whereby growth must be detected in <96 h and <144 h for bacteria and fungi, respectively. Test system qualification in the absence and presence of product is defined as growth promotion qualification and suitability testing, respectively. Growth promotion qualification and product suitability testing are equally important, and both are required to meet cGMP regulations. Growth promotion testing is performed to ensure that the test medium is capable of supporting the growth of the 6 organisms defined in USP<71>, by day 3 for bacteria (defined as <96 h for this study) and by day 5 for fungi (defined as <144 h for this study), and is performed on each lot and/or new shipment. Suitability testing is required to demonstrate that the product does not interfere with the detection of low-level viable organisms and is performed on all new products and whenever changes are made to the manufacturing process or product formulation.

Routine blood culture systems such as Bactec (Becton, Dickinson), BacT/Alert (bioMérieux), and VersaTREK (Trek Diagnostics) have been used in lieu of the compendial USP<71> method in some clinical laboratories (7–12), but a major limitation of those studies has been small study sets focusing mostly on the 6 organisms defined in USP<71>, which do not represent the flora of most cGMP environments or the common contaminants of biopharmaceutical products (13–15). Importantly, automated blood culture systems have always posed a particular challenge for mold detection, as illustrated in routine clinical practice, where lysis centrifugation in an isolator tube followed by culture on solid medium is often recommended over automated blood culture bottle systems for the detection of filamentous fungi from blood (16–19). Mold removal in cleanroom environments via routine disinfectants is also difficult, requiring extended surface contact times and cleaning efficacy studies to demonstrate loss of viability (20–23).

In 2015, mold contamination of two different products that failed to be detected by the Bactec system although visible fungus balls were observed in the growth medium encouraged us to reevaluate the sterility testing system used in our laboratory (24–27). Here, we present a comprehensive performance comparison of the compendial USP<71> method, the Bactec FX system, and the BacT/Alert Dual-T system, assessed over seven different culture combinations and challenged with 118 organisms that represent flora from the NIH cGMP environment and from previous positive products.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial and fungal isolates.

A total of 118 isolates (77 bacteria, 8 yeasts, and 33 molds), representing 93 organisms from the NIH cGMP environment, 3 organisms from previously contaminated products, and 22 reference strains from the American Type Culture Collection were evaluated (Table 1; also see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

TABLE 1.

Organisms obtained from the NIH cGMP environment and contaminated products

| Gram-negative bacteria | Gram-positive bacteria | Molds | Yeasts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acidovorax spp. | Actinomyces spp. | Alternaria spp. | Candida glabrata |

| Acinetobacter baumannii complex | Aerococcus spp. | Arthrinium spp. | Candida parapsilosis |

| Brevundimonas spp. | Agromyces spp. | Aspergillus fumigatus | Cryptococcus spp. |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Arthrobacter spp. | Aspergillus glaucus group | Rhodotorula minuta |

| Methylobacterium spp. | Bacillus cereus | Aspergillus niger | Rhodotorula mucilaginosa |

| Moraxella spp. | Bacillus megaterium | Aspergillus sydowii | Sporobolomyces spp. |

| Neisseria spp. | Bacillus spp. | Aspergillus versicolor | |

| Novosphingobium spp. | Bacillus subtilis | Basidiobolus spp. | |

| Pantoea spp. | Brachybacterium spp. | Byssomerulius corium | |

| Pseudomonas luteola | Brevibacterium spp. | Chaetomium spp. | |

| Pseudomonas oryzihabitans | Cellulomonas spp. | Cladosporium spp. | |

| Psychrobacter spp. | Corynebacterium spp. | Coprinellus spp. | |

| Rhizobium spp. | Dermacoccus spp. | Curvularia spp. | |

| Roseomonas spp. | Janibacter spp. | Epicoccum spp. | |

| Sphingomonas spp. | Kocuria spp. | Exserohilum rostratum | |

| Xenophilus spp. | Kytococcus spp. | Hamigera spp. | |

| Microbacterium spp. | Hypocrea spp. | ||

| Micrococcus luteus | Lecythophora spp. | ||

| Micrococcus spp. | Myrmecridium spp. | ||

| Nocardiopsis spp. | Neosartorya spp. | ||

| Paenibacillus spp. | Nigrospora spp. | ||

| Rhodococcus equi | Paecilomyces lilacinus | ||

| Rothia spp. | Paracamarosporium spp. | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | Penicillium spp. | ||

| Staphylococcus capitis | Pithomyces spp. | ||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | Rhizopus spp. | ||

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus | |||

| Staphylococcus hominis | |||

| Staphylococcus lugdunensis | |||

| Staphylococcus pasteuri | |||

| Staphylococcus pettenkoferi | |||

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus | |||

| Staphylococcus warneri | |||

| Streptococcus mitis group | |||

| Streptococcus salivarius | |||

| Streptomyces spp. | |||

| Tsukamurella spp. | |||

| Williamsia spp. |

Culture methods.

For each organism, 10 bottles were inoculated with <100 CFU (suspended in phosphate-buffered saline) to allow for analysis of seven different culture combinations across the three test systems (Fig. 1). Briefly, two sets of TSB and Thiol broth cultures were inoculated to allow for evaluation of three different incubation combinations, as follows: (i) compendial USP<71> method with TSB at 20 to 25°C and Thiol broth at 30 to 35°C; (ii) both TSB and Thiol broth at 20 to 25°C; and, (iii) both TSB and Thiol broth at 30 to 35°C. The same distribution of bottles was applied to the BacT/Alert Dual-T system, which contained 22.5°C and 32.5°C incubation chambers; two sets of aerobic (iFA plus) and anaerobic (iFN plus) bottles were inoculated and incubated following the three combinations described above. Finally, one set of Bactec aerobic and anaerobic plus bottles was inoculated and incubated at 35°C on the Bactec FX system (single temperature module only). All 10 bottles, regardless of culture combination, were incubated until growth was detected, up to 360 h. TSB and Thiol broth cultures were inspected daily by eye, at approximately the same time each day. BacT/Alert Dual-T and Bactec bottles were monitored for growth every 10 min via colorimetric analysis and fluorometric analysis, respectively. Visual inspection of the BacT/Alert Dual-T and Bactec bottles was performed at the end of the 14-day incubation period (defined as 360 h in this study) if growth had not already been automatically detected by the instrument. For each organism set, <100 CFU bioburden was verified by plating 2 drops (100 µl) of suspension onto sheep blood agar (SBA) or Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA), in duplicate. SBA plates were incubated at 30 to 35°C for up to 96 h, while SDA plates were incubated at 20 to 25°C for up to 144 h.

FIG 1.

Inoculation of test systems. Less than 100 CFU of organisms isolated from the NIH cGMP environment and/or contaminated products, or reference strains, was inoculated into each bottle. Cultures were incubated until positive or up to 360 h. Three incubation temperature combinations were used for the manual method and the BacT/Alert system. The Bactec system supported 35°C incubation only.

Acceptance criteria.

All positive bottles were confirmed by Gram stain morphology. Negative bottles were subcultured onto 5% sheep’s blood agar or SDA, as appropriate, and incubated for 48 to 144 h at 35°C or 25°C, respectively. Following USP<71> criteria, growth promotion was considered acceptable if growth was detected within 3 days of incubation (defined as <96 h for this study) for bacteria or within 5 days of incubation (defined as <144 h for this study) for fungi (5, 6). Inoculated bottles were incubated for up to 360 h, as defined by USP<71> for routine sterility testing, to determine whether growth of certain organisms required extended incubation. In time-to-positivity (TTP) analyses, culture positivity for USP<71> cultures detected on day 1, 2, or 3 was defined as 24, 48, or 72 h, respectively.

Statistical analysis.

Qualitative comparison of the seven different culture combinations across the three test systems was determined by the chi-squared test (https://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/contingency1). The Student’s paired t test (https://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/ttest1) was used for TTP comparisons for isolates detected within 360 h.

RESULTS

Growth promotion of challenge set.

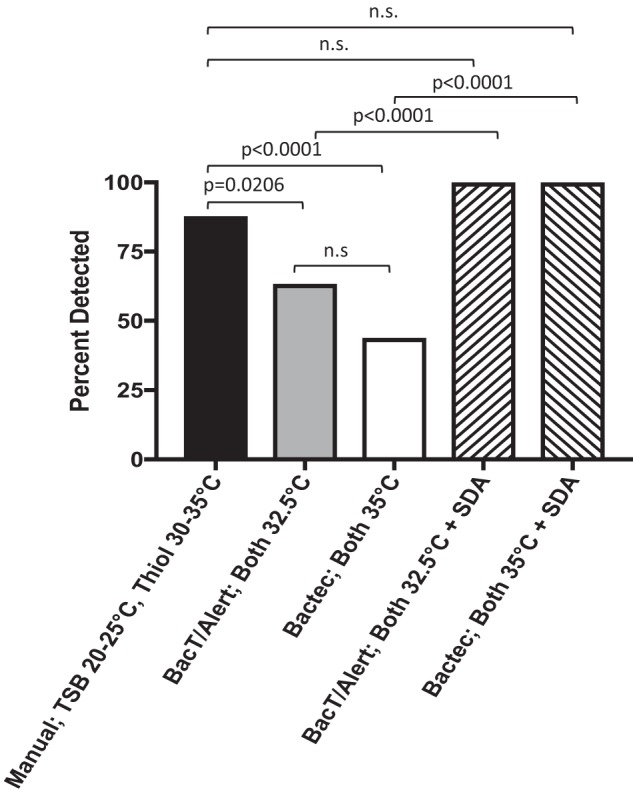

Performance of the seven different culture combinations across the manual method, the BacT/Alert Dual-T system, and the Bactec FX system is summarized in Table 2; significance values are presented in Tables S2 and S3. The compendial USP<71> method performed best, detecting 100 organisms (84.7%) within the acceptably defined time frame and significantly outperforming all other test conditions except the BacT/Alert system with both bottles incubated at 32.5°C (78.8%) (Table 2 and Table S2). Results of the compendial USP<71> method improved to 95.8% (n = 113) when culture incubation was extended to 360 h. Of the four automated blood culture system options, the BacT/Alert with both aerobic and anaerobic bottles at 32.5°C performed best (n = 93 [78.8%]) within the acceptably defined time frame, which was significantly better than the Bactec system (n = 76 [64.4%]; P = 0.0209). Extended incubation with terminal visual inspection improved performance of the BacT/Alert 32.5°C incubation to 89.0% (n = 105), significantly outperforming the Bactec FX system (n = 84 [71.2%]; P = 0.0011) (Table 2 and Table S3). All control plates performed as expected, including growth of all fungi within 144 h on the SDA plate. When data from the BacT/Alert and supplemental SDA plates were combined, the detection of fungi significantly increased from 63.4% (BacT/Alert alone at 32.5°C) to 100.0%, which was better than the compendial USP<71> method (95.8%) (Fig. 2). Similarly, performance of the Bactec FX system paired with SDA plates significantly improved fungal detection from 43.9% (Bactec alone) to 100% (Fig. 2).

TABLE 2.

Positive detection of isolates within acceptable time frames and at 360 h

| System and temperature | Positive detection (%)a

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive bacteria (n = 52) |

Gram-negative bacteria (n = 25) |

Fungi (n = 41) |

Total (n = 118) |

|||||

| Acceptable time frame | <360 h | Acceptable time frame | <360 h | Acceptable time frame | <360 hb | Acceptable time frame | <360 hb | |

| Manual method | ||||||||

| Both at 30–35°C | 92.3 | 98.1 | 72.0 | 80.0 | 36.6 | 39.0 | 68.6 | 73.7 |

| Both at 20–25°C | 69.2 | 96.2 | 56.0 | 92.0 | 85.4 | 87.8 | 72.0 | 92.4 |

| TSB at 20–25°C and Thiol broth at 30–35°Cc | 86.5 | 100 | 76.0 | 96.0 | 87.8 | 90.2 | 84.7 | 95.8 |

| BacT/Alert | ||||||||

| Both at 32.5°C | 94.2 | 98.1 | 72.0 | 88.0 | 63.4 | 70.7 (78.0) | 78.8 | 86.4 (89.0) |

| Both at 22.5°C | 48.1 | 80.8 | 60.0 | 80.0 | 56.1 | 80.5 (87.8) | 53.4 | 80.5 (83.1) |

| Aerobic at 22.5°C and anaerobic at 32.5°C | 65.4 | 94.2 | 68.0 | 88.0 | 58.5 | 80.5 (87.8) | 63.6 | 88.1 (90.7) |

| Bactec, both at 35°C | 76.9 | 82.7 | 72.0 | 72.0 | 43.9 | 46.3 (56.1) | 64.4 | 67.8 (71.2) |

| SDA plates at 20–25°C | NAd | NA | NA | NA | 100 | 100 | NA | NA |

An acceptable time frame was defined as detection in <96 h for bacteria and <144 h for fungi.

Values for visual inspection of bottles from the automated systems are included in parentheses.

The compendial USP<71> method consists of TSB incubated at 20 to 25°C and Thiol broth incubated at 30 to 35°C.

NA, not applicable (SDA plates were set up only for fungal isolates).

FIG 2.

Detection of 41 fungal isolates at <144 h by the compendial USP<71> manual method, the automated BacT/Alert system, and the automated Bactec system, with or without SDA plates. Increased detection of fungal isolates with the BacT/Alert system was achieved with the addition of SDA plates. BacT/Alert and Bactec system data are presented as automatic detection only, without terminal visual inspection. n.s., not significant.

The compendial USP<71> method failed to grow 5 organisms within the 360-h incubation period; all had inocula of <30 CFU (Table S1). An additional 13 isolates were detected by the compendial USP<71> method within 360 h but outside the acceptable time frame of <96 h or <144 h for bacteria or fungi, respectively. Of those isolates, 5 had low inocula (<30 CFU). Notably, Prevotella melaninogenica, Penicillium spp., and Sporobolomyces spp. failed to grow in all seven of the test systems despite growth on the control plates. Another 2 isolates, Paracamarosporium spp. and Nigrospora spp., failed to grow with the compendial USP<71> method but were detected by the BacT/Alert system at 32.5°C.

Time to positivity.

Rates of detection of bacteria within the acceptable 96-h time frame varied from 51.9% to 87.0% across the seven systems (Table 3). Nearly maximum detection for each of the systems occurred within 192 h. Additional detection of fungi beyond 144 h was rare with the manual methods, but up to one-half of the fungal isolates required longer incubation in the automated systems. Importantly, some fungal isolates were detected in the BacT/Alert (n = 3) and Bactec (n = 4) bottles only by manual inspection after 360 h of incubation (Table 3). TTP values were compared for 56 isolates that were positive across all seven testing combinations (Fig. 3A), as well as for 75 isolates that were positive in compendial USP<71>, BacT/Alert 32.5°C, and Bactec 35°C testing (Fig. 3B). The BacT/Alert Dual-T system with incubation at 32.5°C provided the shortest overall TTP of 34 h and was fastest for all organism categories except anaerobes (40 h). The average TTP for the compendial USP<71> method was 50 h, which was significantly longer than the values for BacT/Alert 32.5°C (P < 0.0001) and Bactec 35°C (P = 0.0149) testing. While use of the 22.5°C module in the BacT/Alert system improved mold detection, the overall TTP was 2-fold longer than that determined with both bottles incubated at 32.5°C on the same system (Fig. 3A). For the 75 isolates detected by the compendial USP<71> method, BacT/Alert 32.5°C testing, and Bactec 35°C testing, the automated systems were 23% faster than the compendial USP<71> method overall (40 to 41 h versus 53 h; BacT/Alert, P = 0.0006; Bactec, P = 0.0012) (Fig. 3B). In an effort to remove potential bias due to continuous monitoring by the automated systems versus once-a-day readings for the USP<71> method, isolates positive by BacT/Alert 32.5°C testing (n = 9) and Bactec testing (n = 3) between 72 and 96 h were excluded in a separate analysis; statistical significance between the automated systems and the manual USP<71> method was retained (Table S1).

TABLE 3.

Detection of isolates (cumulative) by time period

| Time to detection | Detection of isolates (%)a

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual method |

BacT/Alert |

Bactec, both at 35°C | |||||

| Both at 30–35°C | Both at 20–25°C | A at 22.5°C and N at 32.5°C | Both at 32.5°C | Both at 22.5°C | A at 22.5°C and N at 32.5°C | ||

| Bacteria (n = 77) | |||||||

| <96 h | 58.7 | 64.9 | 83.1 | 87.0 | 51.9 | 66.2 | 75.3 |

| <192 h | 92.2 | 89.6 | 98.7 | 92.2 | 75.3 | 84.4 | 79.2 |

| <288 h | 92.2 | 94.8 | 98.7 | 93.5 | 79.2 | 92.2 | 79.2 |

| <360 h | 92.2 | 94.8 | 98.7 | 94.8 | 80.5 | 92.2 | 79.2 |

| Not detected | 7.8 | 5.2 | 1.3 | 5.2 | 19.5 | 7.8 | 20.8 |

| Fungi (n = 41) | |||||||

| <144 h | 36.6 | 85.3 | 87.8 | 63.4 | 56.1 | 58.5 | 43.9 |

| <264 h | 36.6 | 85.3 | 87.8 | 70.7 | 78.0 | 78.0 | 46.3 |

| <360 h | 39.0 | 87.8 | 90.2 | 70.7 | 80.5 | 80.5 | 46.3 |

| 360 h with terminal visual check | 39.0 | 87.8 | 90.2 | 78.0 | 87.8 | 87.8 | 56.1 |

| Not detected | 61.0 | 12.2 | 9.8 | 22.0 | 12.2 | 12.2 | 43.9 |

| <144 h (with SDA plates) | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

A, aerobic bottle or TSB; N, anaerobic bottle or Thiol broth.

FIG 3.

Overall TTP of organisms with the manual method, the BacT/Alert system, and the Bactec FX system. (A) Fifty-six isolates detected within 360 h with all seven temperature and system combinations. (B) Seventy-five isolates detected within 360 h with compendial USP<71>, BacT/Alert 32.5°C, and Bactec 35°C testing. TTP values were determined from the first bottle in the set to be positive. Error bars represent the standard errors of the mean.

Bactec versus BacT/Alert for clinical isolates.

Poor performance of the Bactec system caused some concern, because this instrument is used for routine clinical blood cultures in our hospital. An additional targeted analysis of 30 clinically relevant isolates (13 organisms) associated with bloodstream infections was performed using Bactec and BacT/Alert 32.5°C testing (Table S4). Here, the automated systems performed equally well, detecting 26 of the 30 isolates within the acceptably defined time frame. Neither system was able to detect Haemophilus influenzae or Cutibacterium acnes. As expected, addition of 5 ml of fresh human blood to the bottles allowed detection of 2/2 isolates of H. influenzae by both systems within 96 h. The Bactec system detected both isolates of C. acnes, at 280 and 290 h, while the BacT/Alert system detected only 1 of 2 isolates, at 270 h.

Reproducibility assessment.

To ensure performance reproducibility, the 6 organisms defined in USP<71> were compared across all test systems by three independent users. All 18 replicates passed growth promotion in the three combinations of TSB and Thiol broth bottles (Table S5). All bacteria demonstrated acceptable performance with the automated systems, but 1 replicate of C. albicans failed to grow within 144 h with the Bactec system, and all replicates of A. brasiliensis failed in two of the BacT/Alert testing combinations, even with visual checks of the bottles at 144 h. Results obtained with control colony count plates, including growth of C. albicans and A. brasiliensis on SDA plates within 144 h, were acceptable.

DISCUSSION

This study provides the most comprehensive evaluation to date of the USP<71>, BacT/Alert, and Bactec systems for the detection of 118 common cGMP environmental and biopharmaceutical contaminants and highlights important limitations of automated blood culture systems that must be considered if these platforms are used for product sterility testing. Our findings differ significantly from those of previous studies, which have shown equivalent or better performance of the automated blood culture systems, compared with the compendial USP<71> method (7–12, 15, 28). The reason for this contrast is likely due to our analysis of a much larger and more diverse array of challenge organisms relevant to the cGMP environment. Here, our challenge of the systems beyond the 6 USP<71> organisms demonstrated significantly better performance of the compendial USP<71> direct inoculation method (84.7%), compared with the automated Bactec system (64.4%; P = 0.0006), within the defined acceptable time frame. No statistically significant difference was observed between the compendial USP<71> direct inoculation method and automated BacT/Alert 32.5°C detection (78.8%; P = 0.3116) (Table 2; also see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Extended incubation up to 360 h (per routine USP<71> sterility testing requirements) paired with terminal visual inspection demonstrated statistically equivalent performance for compendial USP<71> (95.8%), BacT/Alert 32.5°C (89.0%), and BacT/Alert 22.5°C/32.5°C (90.7%) testing (Table 2 and Table S3).

Poor performance of the Bactec system was surprising, and our data contrast significantly with previously published reports, including one from our own laboratory in 2004 (8). The larger challenge set of organisms studied here, with a heavy focus on molds in response to the two failed detection events in our laboratory in 2015 (24–27) and the lack of available test system performance data for molds in the published literature, likely contributed to this difference. Equivalent performance of the BacT/Alert and Bactec systems for clinical organisms was reassuring, suggesting that broth formularies and standardized detection algorithms built into the instruments are suitable for routine clinical detection of bloodstream infections (Table S4). We show here, however, that the Bactec and BacT/Alert systems alone are suboptimal for the detection of environmental organisms within the defined acceptable growth promotion time frame. As expected, mold detection presented the most difficult challenge for the automated blood culture systems. In clinical practice, this poor sensitivity is circumvented by recommendations to use a fungal isolator culture if fungemia is suspected. Along these lines, culture of the primary product onto SDA plates to supplement blood culture bottles may be useful to enhance mold detection.

Immediately following the two false-negative fungal Bactec events in 2015 (24–27), an SDA plate was added to all product sterility tests performed in our laboratory. In this study, we demonstrated that all SDA control plates grew mold within the acceptable 144-h time frame, compared with only 43.9% and 63.4% of automatically detected mold-positive Bactec and BacT/Alert bottles, respectively, thus strongly supporting the requirement for a supplemental SDA fungal culture to increase detection of fungi if automated blood culture systems are used for product sterility testing.

Nonetheless, automated blood culture systems offer many advantages over the compendial USP<71> method by providing shorter TTP, due to continuous growth monitoring (Fig. 3) (29). This factor is important for cell therapies, as the product has a short shelf life and is likely to have already been infused into the patient based on preliminary negative in-process culture results and direct Gram staining of the final release product (30). In addition to being closed systems in which the product is generally inoculated into the bottles by manufacturing personnel in an environmentally controlled cGMP facility, colorimetric and fluorometric measurements applied in automated blood culture systems offer objective assessments and advantages over the manual compendial USP<71> method, for which culture interpretation can sometimes be difficult and confounded by the turbid nature of cell products. Subculture of the turbid broth, as required by USP<71>, can increase the risk of introducing laboratory contaminants, especially if appropriate processing and environmental controls are not in place. These processing and environmental controls are not the norm in routine clinical microbiology laboratories, which often do not have dedicated spaces and monitoring systems required to meet the cGMP ISO classifications for product sterility testing (5, 21, 30–32); thus, automated systems may be especially helpful for such laboratories. Calling a biological product contaminated (due to either true product contamination or culture of a laboratory contaminant) requires immediate decisions about patient management, as well as safety and regulatory reporting. Patient status is weighed heavily with clinical risks and benefits when deciding whether the contaminated product is to be discarded or infused as-risk (25). Because automated blood culture systems are common in all clinical microbiology laboratories (thereby facilitating product transport logistics and faster result availability), it is likely that clinical microbiology laboratories may be increasingly approached to assist with product sterility testing to support the expanding field of biopharmaceuticals and investigational new drugs in academic medical centers.

Although the compendial USP<71> method outperformed all other test systems in this study, it is not without its limitations. Small inocula (<30 CFU) may explain why 5 organisms failed to grow with the compendial USP<71> method; theoretically, however, 1 CFU should be sufficient for culture. Abela et al. recently associated false-negative BacT/Alert platelet cultures contaminated with S. aureus with low organism burdens even though subcultures of the bottles were positive (33). Our study shows that no system is perfect and clinical judgement and risk-benefit analyses must be considered regardless of which test system is applied. Furthermore, while we demonstrated that the deficiencies of automated blood culture systems to detect fungi were successfully circumvented by the addition of solid SDA plates following routine clinical microbiology practices (16–19), this process increases the risk of introducing laboratory contaminants. Implementation of appropriate processing and environmental controls can minimize the potential for product contamination during product handling. While absolute sensitivity is more important than TTP in sterility testing, rapid detection does have a role in guiding clinical management. A limitation of our study was that the TTP for the USP<71> method was measured in days and then converted to hours, rather than being measured in hours directly, which would have permitted a stricter correlation with the continuous monitoring of automated blood culture systems.

In summary, our study shows that the BacT/Alert system with both aerobic and anaerobic bottles incubated at 32.5°C, paired with an SDA plate, is an acceptable alternative to the compendial USP<71> method for product sterility testing (100.0% versus 95.8%). Based on our findings, we will be switching our routine product sterility testing practice from the current Bactec system to the paired BacT/Alert 32.5°C platform and SDA plate. In addition, all BacT/Alert bottles will be manually inspected, at the end of the 360-h incubation, for the presence of mold that might not have been detected by the instrument. Employing this practice should ensure that workflow efficiency is maintained in a high-volume laboratory while removing the manual, subjective, and confounding factors of deciphering cell product turbidity that would be present if the compendial USP<71> method were applied. In contrast to previously published work, our study highlights the major limitations of automated blood culture systems, which must be taken into careful consideration by biopharmaceutical production facilities when they are choosing their approach to sterility testing.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely our responsibility and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01548-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 30 August 2017. FDA approval brings first gene therapy to the United States. https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm574058.htm.

- 2.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 18 October 2017. FDA approves CAR-T cell therapy to treat adults with certain types of large B-cell lymphoma. https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm581216.htm.

- 3.Ledford H. 2017. Engineered cell therapy for cancer gets thumbs up from FDA advisers. Nature 547:547. doi: 10.1038/nature.2017.22304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Code of Federal Regulations. 2012. Title 21. Food and drugs. Chapter I. Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. Subchapter F. Biologics. Part 610 General biological products standards. 21 CFR 610 U.S. Government Publishing Office, Washington, DC: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=610. [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Pharmacopeia. 2018. USP<71>Sterility tests, p 5984–5991. In 2018 United States Pharmacopeia and National Formulary. USP 41-NF 36 U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Council of Europe. 2018. Chapter 2.6.1. Sterility In European Pharmacopoeia, 9th ed. Revised 1 April 2018 Council of Europe, Strasbourg, France. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khuu HM, Patel N, Carter CS, Murray PR, Read EJ. 2006. Sterility testing of cell therapy products: parallel comparison of automated methods with a CFR‐compliant method. Transfusion 46:2071–2082. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khuu HM, Stock F, McGann M, Carter CS, Atkins JW, Murray PR, Read EJ. 2004. Comparison of automated culture systems with a CFR/USP-compliant method for sterility testing of cell-therapy products. Cytotherapy 6:183–195. doi: 10.1080/14653240410005997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lysák D, Holubová M, Bergerová T, Vávrová M, Cangemi GC, Ciccocioppo R, Kruzliak P, Jindra P. 2016. Validation of shortened 2-day sterility testing of mesenchymal stem cell-based therapeutic preparation on an automated culture system. Cell Tissue Bank 17:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10561-015-9522-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramirez ‐Arcos S, Kou Y, Yang L, Perkins H, Taha M, Halpenny M, Elmoazzen H. 2015. Validation of sterility testing of cord blood: challenges and results. Transfusion 55:1985–1992. doi: 10.1111/trf.13050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akel S, Lorenz J, Regan D. 2013. Sterility testing of minimally manipulated cord blood products: validation of growth‐based automated culture systems. Transfusion 53:3251–3261. doi: 10.1111/trf.12229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mastronardi C, Yang L, Halpenny M, Toye B, Ramírez‐Arcos S. 2012. Evaluation of the sterility testing process of hematopoietic stem cells at Canadian Blood Services. Transfusion 52:1778–1784. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Almeida ID, Schmalfuss T, Röhsig LM, Zubaran Goldani L. 2012. Autologous transplant: microbial contamination of hematopoietic stem cell products. Braz J Infect Dis 16:345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gain P, Thuret G, Chiquet C, Vautrin A-C, Carricajo A, Acquart S, Maugery J, Aubert G. 2001. Use of a pair of blood culture bottles for sterility testing of corneal organ culture media. Br J Ophthalmol 85:1158. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.10.1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murray L, McGowan N, Fleming J, Bailey L. 2014. Use of the BacT/Alert system for rapid detection of microbial contamination in a pilot study using pancreatic islet cell products. J Clin Microbiol 52:3769–3771. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00447-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnes PD, Marr KA. 2007. Risks, diagnosis and outcomes of invasive fungal infections in haematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Br J Haematol 139:519–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kontoyiannis DP, Sumoza D, Tarrand J, Bodey GP, Storey R, Raad II. 2000. Significance of aspergillemia in patients with cancer: a 10-year study. Clin Infect Dis 31:188–189. doi: 10.1086/313918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kozel TR, Wickes B. 2014. Fungal diagnostics. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 4:a019299. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perfect JR. 2013. Fungal diagnosis: how do we do it and can we do better? Curr Med Res Opin 29:3–11. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.761134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Code of Federal Regulations. 2018. Title 21. Food and drugs. Chapter I. Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. Subchapter C. Drugs: general. Part 211. Current good manufacturing practice for finished pharmaceuticals. 21 CFR 211 U.S. Government Publishing Office, Washington, DC: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=211. [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2004. Guidance for industry: sterile drug products produced by aseptic processing: current good manufacturing practice. Food and Drug Administration, Rockville, MD: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/ucm070342.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parenteral Drug Association. 2015. Technical report no. 70: fundamentals of cleaning and disinfection programs for aseptic manufacturing facilities. Parenteral Drug Association, Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Pharmacopeia. 2018. USP<1072>Disinfectants and antiseptics, p 1212–1217. In 2018 United States Pharmacopeia and National Formulary. USP 41-NF 36 U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gandhi TK. 2016. Safety lessons from the NIH Clinical Center. N Engl J Med 375:1705–1707. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1609208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panch SR, Bikkani T, Vargas V, Procter J, Atkins JW, Guptill V, Frank KM, Lau AF, Stroncek DF. 2018. Prospective evaluation of a practical guideline for managing positive sterility test results in cell therapy products. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reardon S. 5 June 2015. Contamination shuts down NIH pharmacy centre. Nat News doi: 10.1038/nature.2015.17703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 29 July 2016. Letter FEI 3011547221. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/EnforcementActivitiesbyFDA/WarningLettersandNoticeofViolationLetterstoPharmaceuticalCompanies/UCM514731.pdf.

- 28.Hocquet D, Sauget M, Roussel S, Malugani C, Pouthier F, Morel P, Gbaguidi-Haore H, Bertrand X, Grenouillet F. 2014. Validation of an automated blood culture system for sterility testing of cell therapy products. Cytotherapy 16:692–698. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parveen S, Kaur S, David SAW, Kenney JL, McCormick WM, Gupta RK. 2011. Evaluation of growth based rapid microbiological methods for sterility testing of vaccines and other biological products. Vaccine 29:8012–8023. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2008. Guidance for industry: CGMP for phase 1 investigational drugs. Food and Drug Administration, Rockville, MD: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm070273.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31.International Organization for Standardization. 2015. Cleanrooms and associated controlled environments, part 1: classification of air cleanliness by particle concentration. ISO 14644-1:2015(E) International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. Pharmacopeia. 2018. USP<1116>Microbiology best laboratory practices, p 7325–7331. In 2018 United States Pharmacopeia and National Formulary. USP 41-NF 36 U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abela MA, Fenning S, Maguire KA, Morris KG. 2018. Bacterial contamination of platelet components not detected by BacT/ALERT. Transfus Med 28:65–70. doi: 10.1111/tme.12458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.