Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DHA-PQ) is under study for intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy (IPTp), but it may accelerate selection for drug resistance. Understanding the relationships between piperaquine concentration, prevention of parasitemia, and selection for decreased drug sensitivity can inform control policies and optimization of DHA-PQ dosing.

KEYWORDS: PK/PD modeling, antimalarial resistance, dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine, intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy

ABSTRACT

Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DHA-PQ) is under study for intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy (IPTp), but it may accelerate selection for drug resistance. Understanding the relationships between piperaquine concentration, prevention of parasitemia, and selection for decreased drug sensitivity can inform control policies and optimization of DHA-PQ dosing. Piperaquine concentrations, measures of parasitemia, and Plasmodium falciparum genotypes associated with decreased aminoquinoline sensitivity in Africa (pfmdr1 86Y, pfcrt 76T) were obtained from pregnant Ugandan women randomized to IPTp with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) or DHA-PQ. Joint pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic models described relationships between piperaquine concentration and the probability of genotypes of interest using nonlinear mixed effects modeling. An increase in the piperaquine plasma concentration was associated with a log-linear decrease in risk of parasitemia. Our models predicted that higher median piperaquine concentrations would be required to provide 99% protection against mutant infections than against wild-type infections (pfmdr1: N86, 9.6 ng/ml; 86Y, 19.6 ng/ml; pfcrt: K76, 6.5 ng/ml; 76T, 19.6 ng/ml). Comparing monthly, weekly, and daily dosing, daily low-dose DHA-PQ was predicted to result in the fewest infections and the fewest mutant infections per 1,000 pregnancies (predicted mutant infections for pfmdr1 86Y: SP monthly, 607; DHA-PQ monthly, 198; DHA-PQ daily, 1; for pfcrt 76T: SP monthly, 1,564; DHA-PQ monthly, 283; DHA-PQ daily, 1). Our models predict that higher piperaquine concentrations are needed to prevent infections with the pfmdr1/pfcrt mutant compared to those with wild-type parasites and that, despite selection for mutants by DHA-PQ, the overall burden of mutant infections is lower for IPTp with DHA-PQ than for IPTp with SP. (This study has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under identifier NCT02282293.)

INTRODUCTION

Plasmodium falciparum infection during pregnancy, especially during a first pregnancy, places infants at risk for the complications of placental malaria, including intrauterine growth retardation, preterm birth, low birth weight, and death (1). The World Health Organization recommends that pregnant women at risk for malaria in Africa use a long-lasting-insecticide-treated bed net and receive at least three doses of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) as intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy (IPTp) (2). However, in much of Africa, including east Africa, the protective efficacy of SP as chemoprevention for pregnant women and children is inadequate (3–5). Compared to three doses of SP during pregnancy, a monthly course of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DHA-PQ), an artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) administered once daily for 3 days, dramatically reduced the prevalence of maternal parasitemia and placental malaria in Uganda and Kenya (5, 6). Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling studies found that plasma piperaquine (PQ) concentrations are excellent predictors of DHA-PQ protective efficacy and that maintaining higher PQ concentrations in the target population, such as with lower dose weekly or daily DHA-PQ, predicts maximal protective efficacy (7–10).

The long half-life of PQ makes DHA-PQ an ideal choice for malaria chemoprevention, but antimalarials with the longest half-lives may be at the greatest risk for resistance selection (11). Although true resistance to DHA-PQ, as observed in southeast Asia (12, 13), has not been confirmed in Africa (14–16), P. falciparum infections that emerge following DHA-PQ treatment have had, compared to that of parasites not under drug selection, increased prevalence of mutant genotypes in the putative drug transporters pfmdr1 (86Y) and pfcrt (76T) (14, 16, 17). These mutations are associated with decreased sensitivity to chloroquine and amodiaquine, two aminoquinolines related to piperaquine (14), and these results raise the concern that using DHA-PQ for chemoprevention may provide only a short-term benefit, with eventual loss of efficacy due to the accelerated development of resistance.

We are interested in optimizing DHA-PQ dosing during IPTp to maximize protective efficacy, minimize toxicity, and limit selection for less-drug-sensitive parasites. In this analysis, we used clinical, pharmacokinetic, and molecular data from a trial of pregnant women who were randomized to receive DHA-PQ or SP as IPTp to develop PK/PD models which quantified relationships between PQ exposure, parasitemia, and genetic markers associated with decreased drug sensitivity. We then used the concentration-effect relationships to predict how modifications to DHA-PQ dosing would impact the burden of P. falciparum infection, including the risk of infection with parasites with decreased drug sensitivity.

RESULTS

Study cohort and data collection.

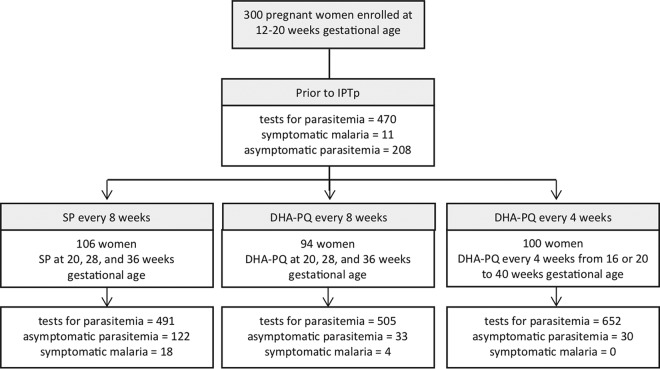

The data were from a randomized controlled trial, in which 300 pregnant women were randomized to one of three IPTp regimens: SP every 8 weeks beginning at gestational week 20, DHA-PQ every 8 weeks beginning at gestational week 20, or DHA-PQ every 4 weeks beginning at gestational week 16 or 20 as previously described (Fig. 1, Table 1) (5). The clinical characteristics were similar between the three study arms (Table 1). Participants returned monthly for routine visits and for any acute illness. At routine visits or when malaria was suspected, an evaluation included a capillary or venous blood draw for the determination of plasma PQ concentration and parasite detection. If the woman was parasitemic, the parasite was genotyped as pfmdr1 86 and pfcrt 76 (16). A subset of 30 women underwent intensive PQ sampling. A total of 652 venous and 558 capillary PQ concentrations were obtained (Table 1; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Genotyping for the single nucleotide polymorphisms at pfmdr1 N86Y and pfcrt K76T was successful for >84% of episodes of parasitemia in the SP arm and for >93% in the DHA-PQ arms. Prevalences of mutant genotypes were higher in the DHA-PQ arms than in the SP arm (pfmdr1 86Y: SP, 27%; DHA-PQ, 65%; pfcrt 76T: SP, 82%; DHA-PQ, 87%), as previously reported (Table 1) (16).

FIG 1.

Trial profile. Study subjects were tested for P. falciparum parasitemia monthly and when they presented for unscheduled visits due to a febrile illness.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of study participants

| Characteristic | SP every 8 wks (N = 106) | DHA-PQ every 8 wks (N = 94) | DHA-PQ every 4 wks (N = 100) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (mean [SD]) | 21 (3.6) | 22 (4.3) | 23 (4.0) |

| Gravidity (n [%]) | |||

| 1 | 42 (40) | 33 (35) | 36 (36) |

| 2 | 32 (30) | 28 (30) | 28 (28) |

| ≥3 | 32 (30) | 33 (35) | 36 (36) |

| Gestational age (wks) at first study drug treatment (%) | |||

| 16 | 68 | ||

| 20 | 106 | 94 | 32 |

| No. of PQ concn observations | |||

| Venous | 300 | 352 | |

| Capillary | 278 | 280 | |

| Visits after participant received indoor residual spraying of insecticide (n) | 101 | 101 | 153 |

| First episodes of parasitemia after each administration of study drug (n)a | 140 | 37 | 30 |

| Genotypes (n [%]) | |||

| pfmdr1 N86Y genotype available | 117 (84) | 37 (100) | 28 (93) |

| pfmdr1 86Y | 32 (27) | 18 (49) | 24 (86) |

| pfcrt K76T genotype available | 122 (87) | 37 (100) | 28 (93) |

| pfcrt 76T | 92 (82) | 31 (84) | 26 (93) |

Artemeter-lumefantrine (AL) was used to treat malaria during the study. To avoid consideration of the effects of AL on repeated observations of the same parasites, parasitemia detected after treatment with AL and before subsequent receipt of DHA-PQ or parasites detected repeatedly without interval receipt of DHA-PQ were excluded.

PK/PD model building.

Simultaneous continuous categorical PK/PD models were developed using a mixed-effects logistic regression approach. Models were evaluated by using an objective function value (OFV), with a decrease in OFV (ΔOFV) of −3.84 considered a significant improvement if one parameter was added to the model, and by a visual predictive check (see Fig. S2). Two types of simultaneous PK/PD models were developed for the analysis. PK/PD parasitemia models predicted the risk of parasitemia. PK/PD resistance models predicted the risk of a mutant infection at pfmdr1 86 or pfcrt 76 when parasitemia was detected.

A two-compartment model for PQ was used to predict plasma concentrations, as previously described (8). For the PK/PD parasitemia model for women who received DHA-PQ, a negative log-linear relationship provided an adequate fit for the association between plasma PQ concentration and risk of parasitemia (ΔOFV −230) (Fig. S2B). Being primigravida was associated with a significant 26.6% increased risk of parasitemia prior to IPTp compared to that for multigravida participants (ΔOFV −24). However, after the initiation of DHA-PQ, gravidity was not a significant predictor of parasitemia in the model. Significant covariates after the initiation of IPTp included being in the second or third trimester and household receipt of indoor residual spraying of insecticide (IRS). Compared to the second trimester, the third trimester was associated with a 19.0% reduction in risk of parasitemia while receiving IPTp (ΔOFV −41). Finally, receipt of IRS, which in the clinical trial only occurred after the start of chemoprevention, was associated with complete protection from parasitemia, eliminating the concentration effect of PQ when present (ΔOFV −36) (Table 2). The additional covariates tested included body mass index (BMI) at enrollment, change in BMI compared to that at enrollment, and the presence of a dry season, and these were not significantly associated with the risk of parasitemia for women who received DHA-PQ. Gravidity, trimester, and BMI were also tested as covariates on the relationship between PQ and risk of parasitemia; these did not significantly improve the PK/PD parasitemia model for DHA-PQ. The final model for the probability of parasitemia is described in equation 1, where P is the probability of parasitemia, B is the baseline risk of parasitemia, sl is the slope of the concentration-dependent change in probability, [PQ] is the PQ concentration in nanograms per microliter, θ represents covariates that were estimated in the model, and ε and η indicate residual error.

| (1) |

TABLE 2.

Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model parameters

| Parameter | Parameter estimate |

Between-subject variability |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | RSEa (%) | CVb (%) | RSE (%) | |

| SP PD model | ||||

| Baseline logit | −0.441 | 39 | 115 | 14 |

| Primigravida baseline logitc | 0.511 | 78 | ||

| Indoor residual spraying | −0.72 | 60 | ||

| Dry season | −1.13 | 28 | ||

| DHA-PQ PK/PD model for parasitemia | ||||

| Baseline logit | −0.508 | 72 | 73 | 17 |

| Primigravida baseline logitc | 0.582 | 64 | ||

| Slope of concentration-dependent effect (ml/ng) | −0.204 | 16 | ||

| Indoor residual spraying | −10 fixed | |||

| Third trimester | −1.45 | 45 | ||

| DHA-PQ PK/PD model for pfmdr1 N86Y | ||||

| Baseline logit | −1.16 | 11 | 3.8 | 53 |

| Slope of concentration-dependent effect | 0.317 | 21 | ||

| DHA-PQ PK/PD for pfcrt K76T | ||||

| Baseline logit | 1.06 | 11 | 2.2 | 22 |

| Slope of concentration-dependent effect | 0.218 | 22 | ||

RSE, relative standard error.

CV, coefficient of variation.

Baseline logit used for all gravidities after start of IPTp, as gravidity was not a significant predictor of parasitemia after the start of chemoprevention.

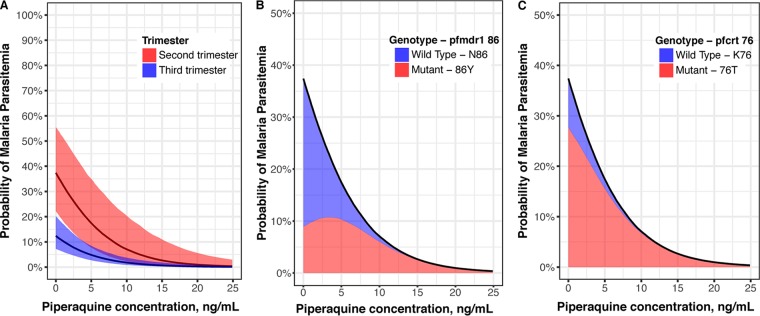

For women who were not exposed to IRS, even low PQ concentrations were associated with a decreased risk of parasitemia compared to that at baseline, and PQ was a predictor of parasitemia risk regardless of the trimester (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

(A) Predicted probability of parasitemia with increasing piperaquine concentration in the absence of indoor residual spraying of insecticide for women receiving DHA-PQ stratified by trimester. The solid lines show the median probabilities and shading encompasses probabilities for 95% of the population. The median probability of parasitemia while receiving SP as IPTp was 39%. Contributions of mutant and wild-type genotypes to overall parasitemia probability during the second trimester for pfmdr1 86 (B) and pfcrt 76 (C). The black lines represent the median probabilities of all parasitemia, and shaded areas indicate the proportions of the probabilities attributed to wild-type and mutant parasites. Results for the third trimester are shown in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material.

For SP, pharmacokinetic data were not available, and a PD model for parasitemia was developed. In a stepwise manner, binary covariates were added to the baseline probability of parasitemia for the SP PD parasitemia model as seen in equation 2, where P is the probability of parasitemia, B is the baseline risk of parasitemia, θ represents covariates that were estimated in the model, and ε and η indicate residual error.

| (2) |

Similar to that for DHA-PQ, being primigravida significantly increased the risk of parasitemia prior to IPTp by 23.3% (ΔOFV −8.0). Receipt of IRS was associated with a reduced risk of parasitemia (32.7%, ΔOFV −27) (Table 2). In addition, for the SP arm, the dry season was independently associated with a decreased risk of parasitemia (24.4%, ΔOFV −17). After adjusting for significant covariates, the model did not support the addition of an SP effect (added as time varying, treatment arm effect, or binary covariate). In addition, enrollment BMI, change in BMI, and trimester were not associated with significant changes in risk of parasitemia.

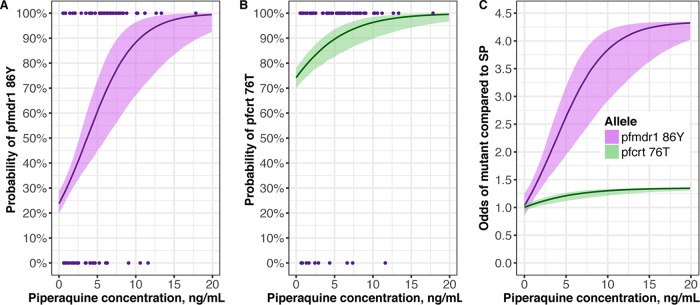

PK/PD resistance models were then developed to estimate the probability of a mutant infection with pfmdr1 N86Y or pfcrt K76T. A log-linear relationship between PQ concentration and the probability of a mutant infection provided the best fit for both pfmdr1 86Y (ΔOFV −11) and pfcrt 76T (ΔOFV −9.6) (Fig. S2C and D). Increasing PQ concentrations were associated with increasing probabilities of a mutant infection at both loci (Fig. 3). As expected, there was no significant relationship between IPTp with SP and detection of a mutant pfmdr1 86Y or pfcrt 76T allele. Compared to that in the SP group, the odds of detecting pfmdr1 86Y increased with increasing PQ concentration, with a maximum median odds of 4.3 occurring at 17.9 ng/ml PQ (Fig. 3C). In the setting of a high baseline risk of pfcrt 76T, PQ exposure was associated with a slight increase in the odds of detecting a mutant compared to that in the SP arm, peaking at a maximum median odds of 1.3 at 10.1 ng/ml PQ (Fig. 3C).

FIG 3.

Predicted probability of detecting mutant pfmdr1 86Y (A) or pfcrt 76T (B) parasites with increasing piperaquine concentrations for women receiving DHA-PQ with parasitemia. Points are the raw data, showing isolates with mutant (100%) or wild-type (0%) genotypes. (C) Odds of detecting mutant genotypes in the DHA-PQ treatment arms compared to that in the SP arm. The solid lines are the median probabilities or increased odds of detecting a mutant parasite during an episode of parasitemia, and the shading encompasses the probability or increased odds of detecting a mutant parasite for 95% of the population.

Derivation of PQ concentration targets.

The PQ concentrations required to prevent 99% of parasitemia episodes varied by trimester. Women in the second trimester were predicted to require 19.6 ng/ml PQ (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.2 to 31.6 ng/ml) to achieve 99% protection from parasitemia, while in the third trimester 12.8 ng/ml (95% CI, 9.2 to 19.2 ng/ml) was required.

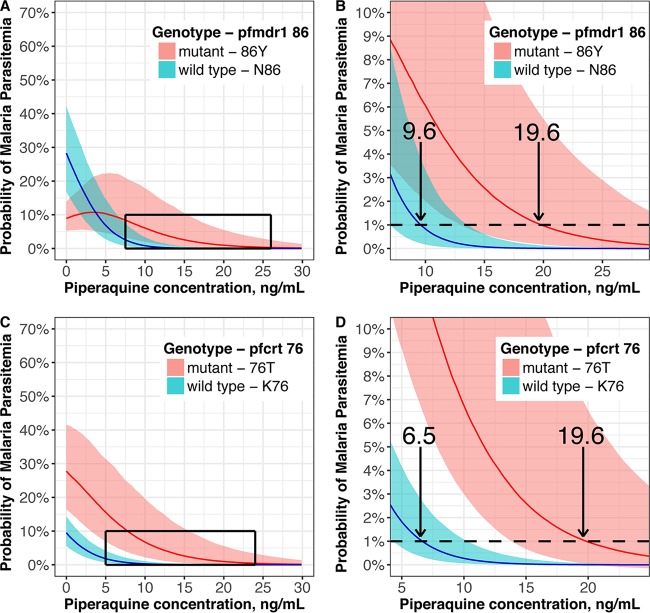

The PQ concentrations required to prevent 99% of parasitemia episodes stratified by wild-type and mutant genotypes were derived from a joint model of the final PK/PD models for predicting parasitemia and genotype. Since women in the second trimester were predicted to require the highest PQ concentrations for protection (see Table S1), this population was used to estimate the target protective concentrations, as shown in Fig. 4. For pfmdr1 86, an increased risk of mutant parasites was predicted compared to that at baseline at subprotective plasma concentrations of PQ, peaking at 3.3 ng/ml (Fig. 2). PQ concentrations required to prevent 99% of parasitemia episodes were predicted to be higher for parasites with mutant pfmdr1 86Y (19.6 ng/ml [95% CI, 12.9 to 32.2]) than with wild-type pfmdr1 N86 (9.6 ng/ml [7.0 to 12.4]) and for mutant pfcrt 76T (19.6 ng/ml [13.1 to 32.2]) than for wild-type pfcrt K76 (6.5 ng/ml [4.1 to 9.3]) (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Association between piperaquine concentration and probability of wild-type or mutant genotype among women in the second trimester receiving DHA-PQ. Probabilities of detecting pfmdr1 86 (A) or pfcrt 76 (B) genotypes are shown, with closer visualization of the curves enclosed in boxes shown for pfmdr1 86 (C) and pfcrt 76 (D). Arrows indicate the median concentrations (ng/ml) providing 99% protection against parasitemia. Lines indicate the median probabilities, and the shading indicates the probability of detecting mutant parasites for 95% of the population.

Simulations to predict the optimal DHA-PQ dosing schedule.

Simulations were conducted of 1,000 women who received SP every 8 weeks or DHA-PQ monthly, weekly, or daily using the joint PK/PD models to estimate the percentage of time above protective concentrations during pregnancy and the predicted number of mutant pfmdr1 86Y and pfcrt 76T infections for each regimen (Table 3, Fig. 5). All simulations assumed no exposure to IRS or seasonal variation. Both the number of parasitemia episodes and the number of mutant parasitemia episodes were predicted to be lower with any of the considered DHA-PQ regimens than with SP. Low-dose (320 mg PQ) daily DHA-PQ was predicted to result in the lowest median number of infections and mutant infections, with an estimated reduction in mutant infections >99%.

TABLE 3.

Predicted number of mutant infections after starting chemoprevention per 1,000 pregnancies by dosing regimena

| Piperaquine dose | No. of infections per 1,000 pregnancies (95% CI) |

pfmdr1 86Y mutant infections |

pfcrt 76T mutant infections |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (95% CI) | Ratio (DHA-PQ/SP) | P value | No. (95% CI) | Ratio (DHA-PQ/SP) | P value | ||

| 0 mg (SP) | 2066 (1988–2162) | 607 (570–650) | 1564 (1495–1564) | ||||

| 2,880 mg monthly | 317 (280–358) | 198 (165–232) | 0.32 | <0.001 | 283 (248–315) | 0.18 | <0.001 |

| 960 mg weekly | 105 (85–122) | 87 (71.0–104) | 0.14 | <0.001 | 99 (80.4–115) | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| 160 mg daily | 8.0 (4.0–14.0) | 8.0 (3.5–13.5) | 0.01 | <0.001 | 8.0 (4.0–14.0) | 0.005 | <0.001 |

| 320 mg daily | 1.0 (1.0–2.1) | 1.0 (0.96–2.1) | 0.002 | <0.001 | 1 (1.0–2.1) | 0.001 | <0.001 |

Estimated based on monthly surveillance for parasitemia in the absence of indoor residual spraying of insecticide or seasonal variation in transmission.

FIG 5.

(A) Predicted percentage of time above piperaquine concentrations protective against 99% of parasitemia episodes during pregnancy by DHA-PQ regimen. Boxes indicate the interquartile ranges and error bars represent 95% of the population. (B) Predicted numbers of new episodes of parasitemia (gray bars) and episodes of parasitemia with a mutant infection at pfmdr1 86 (red) and pfcrt 76 (blue) during pregnancy for each chemoprevention regimen. Monthly, weekly, and daily indicate DHA-PQ regimens.

DISCUSSION

A monthly treatment course of DHA-PQ markedly reduced the burden of parasitemia during pregnancy in Uganda and Kenya, but there is concern that IPTp with DHA-PQ will accelerate selection for drug resistance. With simultaneous PK/PD modeling, we used PQ concentrations and clinical covariates to predict the probability of detecting malaria parasitemia and the probability of detecting parasites with relevant genotypes associated with drug resistance in women receiving DHA-PQ or SP as IPTp in Uganda. Higher concentrations of PQ were needed to reduce the probability of mutant than of wild-type infections at pfmdr1 86 and pfcrt 76, but these concentrations were achievable with practical DHA-PQ dosing regimens, including a novel low-dose daily regimen that should minimize toxicity concerns (8, 18). Despite selection for mutants by DHA-PQ, the overall burden of mutant infections was predicted to be lower for IPTp with DHA-PQ than with SP. Thus, a low daily dose of DHA-PQ for chemoprevention during pregnancy is predicted to maximize protective efficacy, with limited burden of mutant parasites with decreased aminoquinoline sensitivity, and to decrease the risk of cardiotoxicity compared to that with monthly dosing (8, 18).

In our model, we were unable to predict a malaria protective benefit attributable to IPTp with SP after controlling for covariates. P. falciparum polymorphisms associated with antifolate resistance were at high prevalence at the study site (16), and there was a high burden of parasitemia and malarial illness in the SP arm of the study (5). Considering protective efficacy, monthly DHA-PQ was effective for adult males in Thailand (19) and was superior to SP for pregnant women in Uganda and Kenya (5, 6) and for children in Uganda (20). But, as with SP, might regular use of DHA-PQ for IPTp increase the burden of parasites that are no longer inhibited by the regimen? Importantly, in this setting, it does not appear to be the case, as the overall reduction in episodes of parasitemia is predicted to lead to a lower burden of infections with mutant parasites with DHA-PQ as IPTp.

The risk of selecting for P. falciparum with decreased susceptibility to antimalarials will be dependent on the prevalence of these mutants in the circulating parasite population, as selection appears to be due primarily to the amplification of existing clones, rather than de novo selection of new mutants (11). Since our trial was conducted, there have been significant increases in the prevalence of wild-type infections at pfmdr1 86 and pfcrt 76 in the region, likely selected by the use of artemether-lumefantrine (AL) to treat malaria in Uganda (14, 21). An additional wild-type polymorphism, pfmdr1 D1246, also increased in prevalence with AL pressure (14, 21). A haplotype analysis found that mutant pfmdr1 1246Y may be required to select for pfmdr1 86Y under PQ pressure, further reducing the risk of selecting for pfmdr1 86Y under DHA-PQ pressure with current circulating parasites (22). In this setting, a recent Ugandan treatment efficacy study found that, in contrast to results from earlier studies, DHA-PQ did not select for pfmdr1 and pfcrt mutations in recurrent infections (23). Considering our modeling results for this population, it is unlikely that IPTp with DHA-PQ will increase the burden of mutant parasites with decreased sensitivity to the regimen in Uganda. However, risks of resistance selection could change over time based on ACT usage or other factors. Longitudinal surveillance of drug resistance markers and reevaluation of PK/PD models will remain important as we consider using DHA-PQ for IPTp.

Our analysis identified important covariates which modified the risk of parasitemia among women receiving DHA-PQ chemoprevention, including gravidity in the pre-IPTp period and trimester and IRS during IPTp. Remarkably, the combination of monthly DHA-PQ and receipt of IRS eliminated the risk of parasitemia. The benefits of IRS were not as large for the SP arm, likely due to persistent parasitemia despite treatment with SP (3). Recent studies from Uganda found that receipt of IRS is associated with improvements in birth outcomes (24). Taken together, the available results suggest enormous potential for the joint use of highly effective intermittent preventive treatment and IRS for the control and potential elimination of malaria.

Our study had some limitations. First, parasitemia was assessed at 28-day intervals. We could not determine the exact time when an individual became parasitemic and thus the exact concentration required to prevent parasitemia. However, monthly PQ concentrations offered a practical sampling strategy with good predictive power in our models. Second, PK data were not available to assist in detecting a concentration-effect relationship between SP and the prevention of malaria. We found that, after controlling for covariates which are associated with reduced risk of malaria infection, a model without an SP effect predicted the data adequately. The absence of a protective benefit for SP was further supported by a placebo-controlled chemoprevention trial in Uganda that did not demonstrate a significant protective effect of SP in children (4). Third, treatment failure due to DHA-PQ resistance and associated genetic markers has not been identified in Africa and thus could not be used in this analysis. The markers associated with DHA-PQ resistance in Southeast Asia (pfkelch, plasmepsin2 copy number, and exo-E415G [13, 25, 26]) were assessed for this population and were either not present or, in the case of plasmepsin2 copy number, only present in a minority of isolates (16). Pfmdr1 86Y and pfcrt 76T have been consistently associated with PQ exposure in Uganda (17, 27, 28) and have recently been associated with a modest increase in ex vivo 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) for PQ (14). As a result, these markers of antimalarial sensitivity were the most relevant for this population.

By taking a PK/PD modeling approach, we found that higher PQ concentrations are needed to prevent mutant malaria infections than to prevent wild-type malaria infections, but that safe and achievable PQ concentrations can provide >99% protection from parasitemia. In addition, a low-dose daily DHA-PQ regimen was predicted to maximally reduce parasitemia. Our findings support the use of DHA-PQ for chemoprevention and the optimization of DHA-PQ dosing to maximize protective efficacy while minimizing toxicity and potential selection of drug resistance. Future clinical trials of DHA-PQ as chemoprevention during pregnancy should consider alternative dosing strategies, including low-dose daily DHA-PQ.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

Pregnant women were enrolled in the clinical trial that provided samples for our analyses in Tororo, Uganda, from June through October 2014 (5). Eligible women were ≥16 years of age, HIV uninfected, and pregnant at 12 to 20 weeks gestation. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The study protocol was approved by the Makerere University School of Biomedical Sciences Research and Ethics Committee, the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, and the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research. The clinical trial registration number is NCT02282293.

Study design and randomization.

After enrollment, women randomized to SP (1,500 mg sulfadoxine/75 mg pyrimethamine) every 8 weeks or DHA-PQ (120 mg DHA/960 mg PQ daily for 3 days) every 8 weeks began chemoprevention at 20 weeks gestational age, and those randomized to DHA-PQ every 4 weeks began chemoprevention at either 16 or 20 weeks gestational age. The administration of the first dose of DHA-PQ was observed in the clinic, and the remaining two doses were taken at home. At enrollment, study participants received a long-lasting-insecticide-treated bed net, underwent a physical exam, had height and weight determination, and had blood collected. All women attended routine visits at 4-week intervals and were asked to return to the clinic for all of their medical needs. The date of IRS in the household was collected for each subject (24).

Pharmacokinetic sampling.

Women randomized to receive DHA-PQ underwent sparse venous (gestational weeks 20, 28, and 36) and capillary (gestational weeks 24, 32, and 40) sampling to determine plasma PQ concentrations (8). Sparse PQ concentrations were determined either 28 days after receiving the drug in the 4-week DHA-PQ arm or every 28 days and every 56 days after receiving the drug in the 8-week DHA-PQ arm (8). Venous or capillary specimens were also collected at the time of any malaria diagnosis. A subset of individuals were enrolled in an intensive PK substudy. For this study, as previously reported (29), venous plasma samples were obtained predose and at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h postdose, and capillary plasma samples were collected at 24 h and at 4, 7, 14, and 21 days postdose. PQ base concentrations were determined using high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) (30). Modification and partial validation of the original method for PQ quantitation was performed to cover a concentration range of 0.50 to 1,000 ng/ml, with a coefficient of variation <10% for quality control samples (30).

P. falciparum detection and genotyping.

A blood spot was collected and stored on filter paper at all routine visits and if malaria was diagnosed at an unscheduled visit. DNA was extracted from dried blood spots using Chelex-100 and tested for the presence of P. falciparum DNA by loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) for all microscopy negative samples, as previously described (5, 31). Genotyping for pfmdr1 N86Y and pfcrt K76T was conducted using a ligase detection reaction-fluorescent microsphere assay as previously described (28, 32). Isolates were classified as mutant for either pure mutant or mixed mutant and wild-type genotypes.

PK/PD models.

To estimate the concentration effect relationship between PQ PK and probability of parasitemia and between PQ PK and the probability of detecting particular alleles at the loci of interest, simultaneous PK/PD models were developed using nonlinear mixed-effects modeling and LAPLACE methods (33). All available PQ concentration data above the limit of quantitation were used in the development of a two-compartment PQ PK model, as previously described (8). The population PQ PK model was then used as part of a simultaneous continuous categorical PK/PD model with logit transformation to determine the probability of parasitemia or a mutant genotype. To avoid repeated sampling of persistent circulating parasites, testing for parasitemia was censored after the first episode of parasitemia identified following each administration of study drug. Model appropriateness was evaluated by a likelihood ratio test, inspection of the diagnostic plots, and internal model validation techniques, including visual and numerical predictive checks.

We first developed a simultaneous continuous categorical PK/PD parasitemia model to predict the probability of parasitemia among women who received DHA-PQ. Dose response, linear, and maximum effect (Emax) models were tested for the relationship between PQ concentration and the probability of parasitemia. Gravidity, trimester (defined as <28 weeks for the second trimester and ≥28 weeks for the third trimester), enrollment BMI, change in BMI compared to that at enrollment, dry season (defined as December to February), and receipt of IRS were then tested as covariates in the model. We then developed a PD model for the probability of parasitemia for women who received SP. We estimated that SP had a 28-day effect based on prior modeling studies (34). The same covariates were tested for SP as for DHA-PQ.

PK/PD resistance models were developed to estimate the relationship between PQ concentration and parasite genotype at pfmdr1 N86Y or pfcrt K76T, also using simultaneous PK/PD modeling with logit transformation. All PQ PK data and available genotype data from episodes of parasitemia were used to develop models to predict sequences at the pmfdr1 N86Y and pfcrt K76T alleles when parasitemia was detected. Baseline, dose response, linear, and Emax relationships between PQ concentration and genotype were tested for those who received DHA-PQ. Since PK data were not available for SP, a PD resistance model was used to evaluate a study arm effect of SP chemoprevention on selection for mutant infections compared to the prechemoprevention baseline.

The final PK/PD-parasitemia models, with epidemiologic covariates, and PK/PD resistance models for PQ were utilized sequentially, and the concentration of PQ needed to prevent parasitemia with mutant or wild-type infections at each locus was defined as the median value needed to provide 99% protection against parasitemia. One hundred simulations of 1,000 pregnancies were conducted using the final PK/PD models to determine the median number of parasitemia episodes and mutant parasitemia episodes with 95% confidence intervals for 1,000 pregnancies. Dosing strategies were selected to maximize protective efficacy. Simulated regimens included monthly dosing (2,880 mg PQ and 360 mg DHA divided into three consecutive daily oral doses), once weekly dosing (960 mg PQ and 120 mg DHA), and two once daily dosing options (160 mg PQ with 20 mg DHA and 320 mg PQ with 40 mg DHA). All statistical analyses were conducted in R (version 3.3.2) and STATA (version 14.2).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the women who participated in the study, the dedicated study staff, practitioners at the Tororo District Hospital, members of the Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration, and members of the UCSF Drug Research Unit.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI117001-02, R01 A10750-45, T32 GM007546-41, and P01 HD059454). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and interpretation, or decision to submit this work for publication.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01393-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Desai M, ter Kuile FO, Nosten F, McGready R, Asamoa K, Brabin B, Newman RD. 2007. Epidemiology and burden of malaria in pregnancy. Lancet Infect Dis 7:93–104. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70021-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. 2012. Updated WHO policy recommendation: intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy using sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP). WHO, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desai M, Gutman J, Taylor SM, Wiegand RE, Khairallah C, Kayentao K, Ouma P, Coulibaly SO, Kalilani L, Mace KE, Arinaitwe E, Mathanga DP, Doumbo O, Otieno K, Edgar D, Chaluluka E, Kamuliwo M, Ades V, Skarbinski J, Shi YP, Magnussen P, Meshnick S, Ter Kuile FO. 2016. Impact of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine resistance on effectiveness of intermittent preventive therapy for malaria in pregnancy at clearing infections and preventing low birth weight. Clin Infect Dis 62:323–333. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bigira V, Kapisi J, Clark TD, Kinara S, Mwangwa F, Muhindo MK, Osterbauer B, Aweeka FT, Huang L, Achan J, Havlir DV, Rosenthal PJ, Kamya MR, Dorsey G. 2014. Protective efficacy and safety of three antimalarial regimens for the prevention of malaria in young Ugandan children: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 11:e1001689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kakuru A, Jagannathan P, Muhindo MK, Natureeba P, Awori P, Nakalembe M, Opira B, Olwoch P, Ategeka J, Nayebare P, Clark TD, Feeney ME, Charlebois ED, Rizzuto G, Muehlenbachs A, Havlir DV, Kamya MR, Dorsey G. 2016. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for the prevention of malaria in pregnancy. N Engl J Med 374:928–939. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desai M, Gutman J, L'Lanziva A, Otieno K, Juma E, Kariuki S, Ouma P, Were V, Laserson K, Katana A, Williamson J, ter Kuile FO. 2015. Intermittent screening and treatment or intermittent preventive treatment with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine versus intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for the control of malaria during pregnancy in western Kenya: an open-label, three-group, randomised controlled superiority trial. Lancet 386:2507–2519. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00310-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Permala J, Tarning J, Nosten F, White NJ, Karlsson MO, Bergstrand M. 2017. Prediction of improved antimalarial chemoprevention with weekly dosing of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02491-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02491-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savic RM, Jagannathan P, Kajubi R, Huang L, Zhang N, Were M, Kakuru A, Muhindo MK, Mwebaza N, Wallender E, Clark TD, Opira B, Kamya M, Havlir DV, Rosenthal PJ, Dorsey G, Aweeka FT. 2018. Intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in pregnancy: optimization of target concentrations of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine. Clin Infect Dis 67:1079–1088. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sambol NC, Tappero JW, Arinaitwe E, Parikh S. 2016. Rethinking dosing regimen selection of piperaquine for malaria chemoprevention: a simulation study. PLoS One 11:e0154623. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergstrand M, Nosten F, Lwin KM, Karlsson MO, White NJ, Tarning J. 2014. Characterization of an in vivo concentration-effect relationship for piperaquine in malaria chemoprevention. Sci Transl Med 6:260ra147. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stepniewska K, White NJ. 2008. Pharmacokinetic determinants of the window of selection for antimalarial drug resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:1589–1596. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00903-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amaratunga C, Lim P, Suon S, Sreng S, Mao S, Sopha C, Sam B, Dek D, Try V, Amato R, Blessborn D, Song L, Tullo GS, Fay MP, Anderson JM, Tarning J, Fairhurst RM. 2016. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: a multisite prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 16:357–365. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00487-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spring MD, Lin JT, Manning JE, Vanachayangkul P, Somethy S, Bun R, Se Y, Chann S, Ittiverakul M, Sia-Ngam P, Kuntawunginn W, Arsanok M, Buathong N, Chaorattanakawee S, Gosi P, Ta-Aksorn W, Chanarat N, Sundrakes S, Kong N, Heng TK, Nou S, Teja-Isavadharm P, Pichyangkul S, Phann ST, Balasubramanian S, Juliano JJ, Meshnick SR, Chour CM, Prom S, Lanteri CA, Lon C, Saunders DL. 2015. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine failure associated with a triple mutant including kelch13 C580Y in Cambodia: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 15:683–691. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasmussen SA, Ceja FG, Conrad MD, Tumwebaze PK, Byaruhanga O, Katairo T, Nsobya SL, Rosenthal PJ, Cooper RA. 2017. Changing antimalarial drug sensitivities in Uganda. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01516-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01516-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ménard D, Khim N, Beghain J, Adegnika AA, Shafiul-Alam M, Amodu O, Rahim-Awab G, Barnadas C, Berry A, Boum Y, Bustos MD, Cao J, Chen J-H, Collet L, Cui L, Thakur G-D, Dieye A, Djallé D, Dorkenoo MA, Eboumbou-Moukoko CE, Espino F-E-CJ, Fandeur T, Ferreira-da-Cruz M-F, Fola AA, Fuehrer H-P, Hassan AM, Herrera S, Hongvanthong B, Houzé S, Ibrahim ML, Jahirul-Karim M, Jiang L, Kano S, Ali-Khan W, Khanthavong M, Kremsner PG, Lacerda M, Leang R, Leelawong M, Li M, Lin K, Mazarati J-B, Ménard S, Morlais I, Muhindo-Mavoko H, Musset L, Na-Bangchang K, Nambozi M, Niaré K, Noedl H, et al. 2016. A worldwide map of Plasmodium falciparum K13-propeller polymorphisms. N Engl J Med 374:2453–2464. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conrad MD, Mota D, Foster M, Tukwasibwe S, Legac J, Tumwebaze P, Whalen M, Kakuru A, Nayebare P, Wallender E, Havlir DV, Jagannathan P, Huang L, Aweeka F, Kamya MR, Dorsey G, Rosenthal PJ. 2017. Impact of intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy on Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance-mediating polymorphisms in Uganda. J Infect Dis 216:1008–1017. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tumwebaze P, Conrad MD, Walakira A, LeClair N, Byaruhanga O, Nakazibwe C, Kozak B, Bloome J, Okiring J, Kakuru A, Bigira V, Kapisi J, Legac J, Gut J, Cooper RA, Kamya MR, Havlir DV, Dorsey G, Greenhouse B, Nsobya SL, Rosenthal PJ. 2015. Impact of antimalarial treatment and chemoprevention on the drug sensitivity of malaria parasites isolated from Ugandan children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:3018–3030. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05141-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallender E, Vucicevic K, Jagannathan P, Huang L, Natureeba P, Kakuru A, Muhindo M, Nakalembe M, Havlir D, Kamya M, Aweeka F, Dorsey G, Rosenthal PJ, Savic RM. 2018. Predicting optimal dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine regimens to prevent malaria during pregnancy for human immunodeficiency virus-infected women receiving efavirenz. J Infect Dis 217:964–972. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lwin KM, Phyo AP, Tarning J, Hanpithakpong W, Ashley EA, Lee SJ, Cheah P, Singhasivanon P, White NJ, Lindegardh N, Nosten F. 2012. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of monthly versus bimonthly dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine chemoprevention in adults at high risk of malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:1571–1577. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05877-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nankabirwa JI, Wandera B, Amuge P, Kiwanuka N, Dorsey G, Rosenthal PJ, Brooker SJ, Staedke SG, Kamya MR. 2014. Impact of intermittent preventive treatment with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine on malaria in Ugandan schoolchildren: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 58:1404–1412. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tumwebaze P, Tukwasibwe S, Taylor A, Conrad M, Ruhamyankaka E, Asua V, Walakira A, Nankabirwa J, Yeka A, Staedke SG, Greenhouse B, Nsobya SL, Kamya MR, Dorsey G, Rosenthal PJ. 2017. Changing antimalarial drug resistance patterns identified by surveillance at three sites in Uganda. J Infect Dis 215:631–635. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor AR, Flegg JA, Holmes CC, Guerin PJ, Sibley CH, Conrad MD, Dorsey G, Rosenthal PJ. 2017. Artemether-lumefantrine and dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine exert inverse selective pressure on Plasmodium falciparum drug sensitivity-associated haplotypes in Uganda. Open Forum Infect Dis 4:ofw229. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeka A, Wallender E, Mulebeke R, Kibuuka A, Kigozi R, Bosco A, Kyambadde P, Opigo J, Kalyesubula S, Senzoga J, Vinden J, Conrad M, Rosenthal PJ. 12 November 2018. Comparative efficacy of artemether-lumefantrine and dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria in Ugandan children. J Infect Dis. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muhindo MK, Kakuru A, Natureeba P, Awori P, Olwoch P, Ategeka J, Nayebare P, Clark TD, Muehlenbachs A, Roh M, Mpeka B, Greenhouse B, Havlir DV, Kamya MR, Dorsey G, Jagannathan P. 2016. Reductions in malaria in pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes following indoor residual spraying of insecticide in Uganda. Malar J 15:437. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1489-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amato R, Lim P, Miotto O, Amaratunga C, Dek D, Pearson RD, Almagro-Garcia J, Neal AT, Sreng S, Suon S, Drury E, Jyothi D, Stalker J, Kwiatkowski DP, Fairhurst RM. 2017. Genetic markers associated with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine failure in Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: a genotype-phenotype association study. Lancet Infect Dis 17:164–173. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30409-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Witkowski B, Duru V, Khim N, Ross LS, Saintpierre B, Beghain J, Chy S, Kim S, Ke S, Kloeung N, Eam R, Khean C, Ken M, Loch K, Bouillon A, Domergue A, Ma L, Bouchier C, Leang R, Huy R, Nuel G, Barale J-C, Legrand E, Ringwald P, Fidock DA, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Ariey F, Ménard D. 2017. A surrogate marker of piperaquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria: a phenotype-genotype association study. Lancet Infect Dis 17:174–183. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30415-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nankabirwa JI, Conrad MD, Legac J, Tukwasibwe S, Tumwebaze P, Wandera B, Brooker SJ, Staedke SG, Kamya MR, Nsobya SL, Dorsey G, Rosenthal PJ. 2016. Intermittent preventive treatment with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine in Ugandan schoolchildren selects for Plasmodium falciparum transporter polymorphisms that modify drug sensitivity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:5649–5654. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00920-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conrad MD, LeClair N, Arinaitwe E, Wanzira H, Kakuru A, Bigira V, Muhindo M, Kamya MR, Tappero JW, Greenhouse B, Dorsey G, Rosenthal PJ. 2014. Comparative impacts over 5 years of artemisinin-based combination therapies on Plasmodium falciparum polymorphisms that modulate drug sensitivity in Ugandan children. J Infect Dis 210:344–353. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kajubi R, Huang L, Jagannathan P, Chamankhah N, Were M, Ruel T, Koss CA, Kakuru A, Mwebaza N, Kamya M, Havlir D, Dorsey G, Rosenthal PJ, Aweeka FT. 2017. Antiretroviral therapy with efavirenz accentuates pregnancy-associated reduction of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine exposure during malaria chemoprevention. Clin Pharmacol Ther 102:520–528. doi: 10.1002/cpt.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kjellin LL, Dorsey G, Rosenthal PJ, Aweeka F, Huang L. 2014. Determination of the antimalarial drug piperaquine in small volume pediatric plasma samples by LC-MS/MS. Bioanalysis 6:3081–3089. doi: 10.4155/bio.14.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hopkins H, Gonzalez IJ, Polley SD, Angutoko P, Ategeka J, Asiimwe C, Agaba B, Kyabayinze DJ, Sutherland CJ, Perkins MD, Bell D. 2013. Highly sensitive detection of malaria parasitemia in a malaria-endemic setting: performance of a new loop-mediated isothermal amplification kit in a remote clinic in Uganda. J Infect Dis 208:645–652. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LeClair NP, Conrad MD, Baliraine FN, Nsanzabana C, Nsobya SL, Rosenthal PJ. 2013. Optimization of a ligase detection reaction-fluorescent microsphere assay for characterization of resistance-mediating polymorphisms in African samples of Plasmodium falciparum. J Clin Microbiol 51:2564–2570. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00904-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonate PL, Steimer J-L. 2006. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling and simulation. Springer Science+Business Media, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Kock M, Tarning J, Workman L, Nyunt MM, Adam I, Barnes KI, Denti P. 2017. Pharmacokinetics of sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine for intermittent preventive treatment of malaria during pregnancy and after delivery. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 6:430–438. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.