Multi- and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (M/XDR-TB) has become an increasing threat not only in countries where the TB burden is high but also in affluent regions, due to increased international travel and globalization. Carbapenems are earmarked as potentially active drugs for the treatment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

KEYWORDS: carbapenems, clinical, ertapenem, imipenem, in vitro, in vivo, meropenem, tuberculosis

ABSTRACT

Multi- and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (M/XDR-TB) has become an increasing threat not only in countries where the TB burden is high but also in affluent regions, due to increased international travel and globalization. Carbapenems are earmarked as potentially active drugs for the treatment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. To better understand the potential of carbapenems for the treatment of M/XDR-TB, the aim of this review was to evaluate the literature on currently available in vitro, in vivo, and clinical data on carbapenems in the treatment of M. tuberculosis and to detect knowledge gaps, in order to target future research. In February 2018, a systematic literature search of PubMed and Web of Science was performed. Overall, the results of the studies identified in this review, which used a variety of carbapenem susceptibility tests on clinical and laboratory strains of M. tuberculosis, are consistent. In vitro, the activity of carbapenems against M. tuberculosis is increased when used in combination with clavulanate, a BLaC inhibitor. However, clavulanate is not commercially available alone, and therefore, it is impossible in practice to prescribe carbapenems in combination with clavulanate at this time. Few in vivo studies have been performed, including one prospective, two observational, and seven retrospective clinical studies to assess the effectiveness, safety, and tolerability of three different carbapenems (imipenem, meropenem, and ertapenem). We found no clear evidence at the present time to select one particular carbapenem among the different candidate compounds to design an effective M/XDR-TB regimen. Therefore, more clinical evidence and dose optimization substantiated by hollow-fiber infection studies are needed to support repurposing carbapenems for the treatment of M/XDR-TB.

INTRODUCTION

Treatment of tuberculosis (TB), a disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, has become more challenging with the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR)-TB and extensively drug-resistant (XDR)-TB among previously and newly detected cases (1). M/XDR-TB has become an increasing threat not only in countries where the TB burden is high but also in affluent regions, due to increased international travel and globalization.

MDR-TB is defined as an infectious disease caused by M. tuberculosis that is resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampin. XDR-TB is defined as MDR-TB with additional resistance to at least one of the fluoroquinolones and to at least one of the injectable second-line drugs (amikacin, capreomycin, or kanamycin). New TB drugs, with a novel mechanism of action, include bedaquiline and delamanid, which have recently been approved and included as add-on agents in the World Health Organization guidelines on MDR-TB treatment (2). Unfortunately resistance to these agents has already been detected (3). Exploration of currently available drugs for their potential effect against TB may be an additional source for potential candidates to be used in case of extensive resistance to try to compose a treatment regimen (4, 5).

Beta-lactam antimicrobial drugs are widely used for the treatment of a range of infections. Also, imipenem-cilastatin and meropenem have been listed as add-on drugs in the updated WHO treatment guidelines (6). Carbapenem activity has long been considered to be of limited use, due to rapid hydrolysis of the beta-lactam ring by broad-spectrum mycobacterial class A beta-lactamases (BLaC). The addition of the BLaC inhibitor clavulanate suggests that beta-lactams combined with BLaC inhibitors could be beneficial in the treatment of TB (7). Recent studies suggest that beta-lactams using clavulanate/clavulanic acid show more activity against M. tuberculosis (7–14).

The bacterial activity of beta-lactams is due to the inactivation of bacterial transpeptidases, commonly known as penicillin binding proteins (PBP), which inhibit the biosynthesis of the peptidoglycan layer of the cell wall of bacteria (8, 15). Polymerizations of the peptidoglycan layer in most bacteria are predominantly cross-linked by d,d-transpeptidases (DDT), the enzymes inhibited by beta-lactams (8, 16). In M. tuberculosis, the majority of cross-links in peptidoglycan appear to be formed by the nonclassical l,d-transpeptidases (LDT) (17–23). Several studies revealed the structural basis and the inactivation mechanism of LDT and the active role of carbapenems, providing a basis for the potential use of carbapenems in inhibiting M. tuberculosis (22, 24–27).

Beta-lactams show time-dependent activity, while carbapenems have been shown to have bactericidal activity when the free-drug plasma concentration exceeds the MIC for at least 40% of the time (40% Tfree > MIC) in non-M. tuberculosis bacterial species (28, 29).

Carbapenems are earmarked as potentially active drugs for the treatment of M. tuberculosis. To better understand the potential of carbapenems for the treatment of M/XDR-TB, the aim of this review was to evaluate the literature on currently available in vitro, in vivo, and clinical data on carbapenems in the treatment of M. tuberculosis and to detect knowledge gaps, in order to target future research.

RESULTS

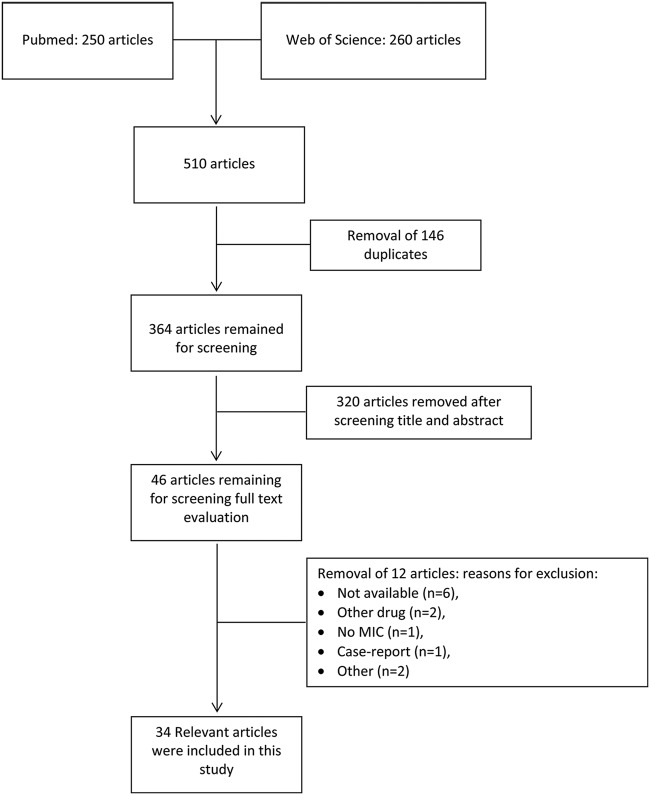

Based on the selection criteria, 250 articles were retrieved in PubMed and 260 in Web of Science. After removal of 146 duplicates, 364 articles remained for screening. After screening of the title and abstract, 46 articles remained for full text evaluation. Reasons for exclusion included the following: not available (n = 6), other drugs (n = 2), no MIC data (n = 1), case report (n = 1), and other (n = 1). After this process, 35 relevant articles were included in this study (Fig. 1). Due to the low number of articles and the high diversity of strains, analytical methods, and study designs, the presence of biochemical instability of the drugs of interest, the short half-life of drugs of interest in mice, and the diversity in MIC determination, we did not have enough data to perform a meta-analysis. The risk of bias of the included studies is shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Studies on clinicaltrials.gov are shown in Table S2.

FIG 1.

Literature selection process flow chart

In vitro studies.

The results of the in vitro studies reporting on carbapenems are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Results of the in vitro studies reporting on carbapenemsa

| First author (reference[s]) | Strain(s) | No. of strains | Method(s) | Carbapenem(s) | β-Lactamase inhibitor(s) |

Value(s) [mg/liter; median (range)] for: |

MBC99 | CFU reduction [log (CFU/ml)] |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbapenem |

Carbapenem with CLV |

||||||||||||

| MIC | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC | MIC50 | MIC90 | ||||||||

| Chambers (30) | H37Ra, H37Rv, clinical isolates |

7 | Bactec TB system | Imipenem | None | (2–4) | |||||||

| Cohen (36) | H37Rv, clinical isolates |

91 | Microplate alamar blue ssay |

Meropenem | Clavulanate | 22 (2–32) | 5.4 (0.5–32) | ||||||

| Cavanaugh (37) | Clinical isolates | 153 | Resazurin microdilution assay |

Meropenem | Clavulanate | (<0.12–>16) | 1 | 8 | |||||

| Deshpande (45) | H37Ra, THP 1 monocytes |

1 | Resazurin microdilution assay, CFU counts |

Faropenem | None | 1 | 2.71 | ||||||

| Dhar (47) | H37Rv, Erdman | 2 | 96-well, flat-bottom, polystyrene microtiter plate |

Faropenem, meropenem, imipenem |

Clavulanate | 1.3, 2.5, 2.5b |

1.3, 0.3, 0.5b | ||||||

| England (38) | H37Rv, macrophages | 1 | CFU counts | Meropenem | Clavulanate | 2 | |||||||

| Forsman (39) | H37Rv, clinical isolates |

69 | Broth microdilution | Meropenem | Clavulanate | (0.125–32) | 1 | ||||||

| Gonzalo (40) | H37Rv, clinical isolates |

28 | 960 MGIT system | Meropenem | Clavulanate | Resistant at 5 mg/liter |

(1.28–2.56) | ||||||

| Gurumurthy (46) | H37Rv | 1 | 96-well plate | Faropenem | None | (5–10) | 20 | 0 | |||||

| Horita (41) | H37Rv, clinical isolates |

42 | Broth microdilution | Meropenem, biapenem, tebipenem |

Clavulanate (avibactamb) | (1–32), (1–32), (0.25–8) |

16, 16, 4 | 32, 32, 8 | (0.063–8), (0.25–8), (0.063–8) |

2, 2, 1 | 4, 4, 1 | ||

| Hugonnet (8) | Erdman, H37Rv, clinical isolates |

15 | Broth microdilution | Imipenem, meropenem | Clavulanate | 0.16 (0.23–1.25) | |||||||

| Kaushik (31) | H37Rv, clinical isolates |

1 | Broth microdilution | Imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem, doripenem, biapenem, faropenem, tebipenem, panipenem |

Clavulanate | (40–80), (5–10),(10–20), (2.5–5), (2.5–5), (2.5–5), (1.25–2.5), >80 |

(20–40), (2.5–5), (5–10), (1.25–2.5), (0.6–1.2), (2.5–5), (0.31–0.62), ND |

ND, 80, ND, 20, 20, 20, 10, ND |

|||||

| Kaushik (49) | H37Rv, strain 115R, strain 124R |

3 | Broth microdilution | Biapenem | None | (2–16) | |||||||

| Sala (42) | 18b cells | 1 | Serial dilutions, CFU counts |

Meropenem | Clavulanate | 2 | |||||||

| Solapure (32) | H37Rv, 18b cells | 1 | Resazurin microdilution assay, CFU counts |

Imipenem, meropenem, faropenem |

Clavulanate | 4, 8, 4 | 0.5, 1, 2 | 4 (5 mg/ml), 2, 4 | |||||

| Srivastava (43) | H37Ra | 1 | Resazurin microdilution assay |

Ertapenem | Clavulanate | 0.6 | 2.38 | ||||||

| Veziris (33) | H37Rv | 1 | Broth microdilution | Imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem |

Clavulanate | 16, 8, 16 | 1, 1, 4 | ||||||

CLV, clavulanate (2.5 mg/liter); MBC99, minimal bactericidal concentration that kills 99% of replication culture (mg/liter); ND, not described.

MICs for carbapenems with avibactam are not shown in this table.

Imipenem.

Susceptibility testing of imipenem against strains H37Rv, H37Ra, and Erdman and clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis using various analytical methods showed a range of MICs of between 2 and 32 mg/liter without clavulanic acid and a range of MICs of between 0.16 and 32 mg/liter with clavulanic acid (8, 30–35). When imipenem was combined with clavulanate, it showed 4- to 16-fold-lower MICs against the M. tuberculosis H37Rv reference strain (8, 31–33).

Meropenem.

Multiple studies reported that meropenem in the presence of clavulanate is active in vitro against clinical and laboratory strains H37Rv and H37Ra of M. tuberculosis, showing MICs of ≤1 mg/liter. In vitro studies reporting susceptibility to meropenem of M. tuberculosis reference strains and clinical isolates showed MICs of between 1 and 32 mg/liter (8, 31–42). Meropenem in combination with clavulanic acid was shown to have MICs of between 0.063 and 32 mg/liter (31–33, 36, 41). Meropenem in combination with clavulanate killed the nonreplicating ss18b strain of M. tuberculosis moderately and was shown to have MICs of 0.125 to 2.56 mg/liter against M. tuberculosis H37Rv strains (8, 32, 33, 38). A decrease of 2 log10 CFU over 6 days was reported in M. tuberculosis-infected murine macrophages (38).

Ertapenem.

In clinical strains of M. tuberculosis, the MIC of ertapenem as a single agent was 16 mg/liter and when combined with clavulanate was 4 mg/liter (31, 33). Another study showed that ertapenem was unstable, degrading faster than the doubling time of M. tuberculosis in the growth medium used, suggesting that previous published MICs of ertapenem are likely to be falsely high (43). In a hollow-fiber model with supplementation of ertapenem in a broth microdilution test, ertapenem showed a MIC of 0.6 ml/liter (44). A 28-day exposure-response hollow-fiber-model TB study tested 8 different doses of ertapenem in combination with clavulanate and identified the ertapenem exposure associated with optimal sterilizing effect for clinical use. Monte Carlo simulation with 10,000 MDR-TB patients identified a susceptibility breakpoint MIC of 2 mg/liter for an intravenous dose of 2 g once a day that achieved or exceeded 40% Tfree > MIC (44).

Faropenem.

Faropenem showed a 4-fold reduction when combined with clavulanic acid (31, 32), resulting in a MIC range of 1 to 5 mg/liter (31, 32, 45–47). In a hollow-fiber model, the optimal target exposure was identified as being associated with optimal efficacy in children with disseminated TB using Monte Carlo simulations; the predicted optimal oral dose was 30 mg/kg of body weight of faropenem-medoximil 3 to 4 times daily. The exposure target for faropenem-medoximil was 60% Tfree > MIC (48).

Other carbapenems.

Other carbapenems, such as doripenem, biapenem, and tebipenem, showed at least a 2-fold reduction in MIC when combined with clavulanic acid (31, 35, 41, 49).

In vivo studies.

The results of the in vivo studies reporting on carbapenems are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Results of the in vivo studies reporting on carbapenemsa

| First author (reference[s]) |

Strain | Type of mice or other animal model |

Mode of infection |

Drug(s) | Dosage(s) | Infection model | Length of treatment |

End point(s) | Organ(s) tested | CFU reduction | Survival rate |

CFU reduction with CLV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chambers (50) | H37Rv | CD-1 female mice | Subcutaneous | Imipenem | 100 mg/kg BID | ND | 28 days | CFU count, survival rate |

Spleen, lungs | 1.8 log | 65% | ND |

| Dhar (47) | H37Rv | Adult C57BL/6J mice | Intratracheal | Faropenem | 500 mg/kg | Acute TB | 8 days | CFU count | Lungs | 10̂5–10̂6 | ND | ND |

| England (38) | H37Rv | C57BL/6 mice; New Zealand White rabbits |

Subcutaneous; intravenous bolus |

Meropenem; meropenem |

300 mg/kg BID; 75 mg/kg, 125 mg/kg |

Chronic stage; ND | 2 wks; ND | CFU count; PK data |

Spleen, lungs; ND |

1 log; ND | ND; ND | 1 log; ND |

| Kaushik (49) | H37Rv | BALB/c mice | Aerosol | Biapenem | 200 mg/kg BID, 300 mg/kg BID |

Late-phase acute TB, rifampin-resistant TB |

8 wks, 4 wks | CFU count | Lungs | 1 log, ND | ND | ND |

| Rullas (51) | H37Rv | TF3157 DHP-I KO mice | Subcutaneous | Meropenem, faropenem |

300 mg/kg TID, 500 mg/kg TID |

Acute TB model | 21 days | CFU count | Lungs | 1.7 log, 2 log | ND, ND | ND, ND |

| Solapure (32) | H37Rv | BALB/c mice | Aerosol | Meropenem | 300 mg/kg TID | Acute and chronic model | 4 wks | CFU count | lungs | None | ND | none |

| Veziris (33)b | H37Rv | Female Swiss mice | Intravenous | Imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem |

100 mg/kg, 100 mg/kg, 100 mg/kg |

Preventive model | 28 days | CFU count, survival rate |

Spleen, lungs | >1.2 log, >1.8 log, >1.7 log |

1 dead, 3 dead, 3 dead |

>0.9 log, >1.4 log, >1.6 log |

CLV, clavulanate (2.5 mg/liter); BID, twice a day, TID, three times a day, ND, not described.

There was a CFU increase in the groups with and without clavulanate compared to the start of the treatment.

Imipenem.

The bacterial burden in imipenem-treated (100 mg/kg twice daily [BID]) CD-1 female mice infected with M. tuberculosis strain H37Rv was reduced by 1.8 log10 in splenic tissue and 1.2 log10 in lung tissue after 28 days, showing an antimycobacterial effect, as well as improved survival, in this mouse model (50). In another study, Swiss mice, infected with M. tuberculosis strain H37Rv, were treated with a subcutaneous administration of 100 mg/kg imipenem in combination with clavulanate once a day to simulate a human-equivalent dose. The CFU count after 28 days of treatment increased compared to the CFU count at start of treatment. There was a significant difference only in the imipenem-clavulanate-treated mice (33).

Meropenem.

It has been reported that 300 mg/kg meropenem BID alone and in combination with 50 mg/kg clavulanate both resulted in significant, though modest reductions in CFU in lung and spleen tissues in C57BL/6 mice (38). Veziris et al. reported increased CFU compared to the counts at the start of the treatment, as well as increases in spleen weights and lung lesions, when meropenem was given to Swiss mice as monotherapy or in combination with clavulanate in a dose of 100 mg/kg (33). Meropenem in a dose of 300 mg/kg in combination with 75 mg/kg clavulanate thrice daily given to BALB/c mice showed marginal reductions in CFU counts in the acute model and no reductions in the chronic model (32). Meropenem, given subcutaneously at 300 mg/kg three times a day, showed a CFU count reduction of 1.7 log in the lungs of TF3157 DHP-1-deficient mice (51).

Ertapenem.

In a murine TB model infected with H37Rv, a dose of 100 mg/kg ertapenem once daily as monotherapy or in combination with clavulanate had neither bactericidal nor bacteriostatic activity in lungs and spleens of TB-infected mice. Spleen weight and lung lesions remained similar to those in the untreated group of mice. There were increases in CFU compared to the counts at the start of the treatment (33).

Other carbapenems.

An oral dose of 500 mg/kg faropenem medoxil, given three times daily, gave a reduction of 2 log CFU in the lungs of TF3157 DHP-1-deficient mice (51). Neither in vivo nor clinical studies for other carbapenems as part of a multidrug regimen against TB were retrieved.

Clinical studies.

The results of the clinical studies reporting on carbapenems are presented in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Results of the human studies reporting on carbapenemsa

| First author (reference[s]) |

Yr of publication |

Country(ies) | Study duration |

Study design | Drug | Dosage(s) | No. of patients |

Pediatric | No. of patients for whom indicated parameter applies/total no. of patients: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sputum smear |

Sputum culture |

Treatment success |

AE | Interruption due to AE |

|||||||||

| Arbex (52) | 2016 | Brazil | 2013–2015 | Observational, retrospective |

Imipenem | 1 g OC | 12 | No | 12/12 | 12/12 | 7/12 | 0/12 | 0/12 |

| Chambers (50) | 2005 | USA | ND | Prospective | Imipenem | 1 g BID | 10 | No | ND | 8/10 | 7/10 | ND | ND |

| De Lorenzo (56) | 2014 | Italy, The Netherlands |

2001–2012 | Observational case-control |

Meropenem | 1 g TID | 37 | No | 28/32 | 31/37 | ND | 5/37 | 2/5 |

| Payen (55) | 2018 | Belgium | 2009–2016 | Retrospective case series |

Meropenem | 2 g TID (then BID) |

18 | No | 16/18 | 16/18 | 15/18 | 0/18 | 0/18 |

| Palmero (57) | 2015 | Argentina | 2012–2013 | Retrospective | Meropenem | 2 g TID (then 1 g TID) |

10 | No | ND | 8/10 | 3/6 | 0/10 | ND |

| Van Rijn (10) | 2016 | The Netherlands | 2010–2013 | Retrospective | Ertapenem | 1 g OC | 18 | Yes | ND | 15/18 | 15/18 | 2/18 | 3/18 |

| Tiberi (59) | 2016 | Italy | 2008–2015 | Retrospective, cohort |

Ertapenem | 1 g OC | 5 | No | 3/5 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| Tiberi (58) | 2016 | Multicenters in 3 countries |

2003–2015 | Observational, retrospective, cohort |

Meropenem | 1 g TID (then 2 g TID) |

96 | No | 55/58 | 55/58 | 55/96 | 6/93 | 8/94 |

| Tiberi (11, 53) | 2016 | Multicenters in 8 countries |

2003–2015 | Observational, retrospective, case-control |

Imipenem | 500 mg QID | 84 | No | 51/64 | 51/64 | 34/57 | 3/56 | 4/55 |

OD, once a day; BID, twice a day; TID, three times a day; QID, four times a day; ND, not described; AE, adverse event(s).

Imipenem.

Ten patients were treated with imipenem in combination with two or more other antimicrobial agents. It was reported that it was likely that 1 g of imipenem (BID) contributed to sputum culture conversion in these patients (50). A prospective study evaluated 1,000 mg/day imipenem-clavulanate once daily in 12 patients, 11 of whom received linezolid-containing regimens. All patients showed sputum and culture conversion within 180 days. No adverse events were reported for imipenem-clavulanate (52). In a large observational study, the clinical outcomes of 84 patients, treated with 500 mg imipenem-clavulanate four times a day, were compared with results from 168 controls. The study showed that imipenem-containing regimens achieved results comparable to those of the imipenem-sparing regimens, while success rates were similar to those in major international MDR-TB cohorts (53).

Meropenem.

A regimen including meropenem-clavulanate given to 18 patients with severe pulmonary XDR-TB led to sputum culture conversion in 15 patients, of whom 10 successfully completed treatment and 5 were considered cured according to WHO guidelines. Long-term safety was not a problem in this study, as no adverse events were reported (54, 55). The first study that evaluated efficacy, safety, and tolerability was a case-control study in 37 patients, who received meropenem-clavulanate as part of a linezolid-based multidrug regimen. This is the first study that showed an added value of meropenem-clavulanate in a multidrug regimen. The meropenem-clavulanate-containing regimen showed a sputum microscopy conversion of 87.5% and a sputum culture conversion of 83.8%, while the meropenem-clavulanate-sparing regimen showed a sputum microscopy conversion of 56.3% and a sputum culture conversion of 62.5% after 90 days of treatment (56). In another study, 10 XDR and pre-XDR female patients were treated with multidrug regimens and received meropenem-clavulanate for 6 months or more. Eight patients achieved sputum conversion after 6 months, while two patients died (57). Pharmacokinetic parameters of 1 g meropenem-clavulanate given intravenously over 5 min showed a serum peak of 112 mg/ml and a concentration of 28.6 mg · h/liter (37). In an observational retrospective cohort study, efficacy and safety were evaluated in 96 patients treated with regimens containing meropenem-clavulanate and compared with the data for 168 controls. Sputum smear and culture conversion rates were found to be similar (58). In an observational study comparing therapeutic contributions, such as sputum smear and culture conversion rates and success rates, of imipenem-clavulanate and meropenem-clavulanate in a background regimen, the results suggested that meropenem-clavulanate can contribute to the efficacy of a regimen in treating M/XDR-TB patients (11).

Ertapenem.

The first report on clinical experience with ertapenem presented data from five patients who were treated with an intravenous injection of 1 g ertapenem once daily in a multidrug regimen. Three of these patients showed sputum smear and culture conversion; four of five patients had a successful treatment outcome. Two patients interrupted treatment due to an adverse event. These adverse events were considered unrelated to the study drug (59). In an observational study, 18 patients were treated with 1 g ertapenem once daily; fifteen of these patients had a successful treatment outcome and were cured. Three patients were lost to follow-up. Three patients stopped ertapenem treatment due to adverse events unrelated to ertapenem. Pharmacokinetic parameters were evaluated in 12 patients, showing a mean peak in plasma of 127.5 (range, 73.9 to 277.9) mg/liter and an area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) of 544.9 (range, 390 to 1,130) mg · h/liter. Based on a MIC of 0.25 mg/ml, 11/12 patients reached or exceeded the target value of 40% Tfree > MIC (10). The pharmacokinetic model composed in this study was shown to adequately predict ertapenem exposure in MDR-TB patients. The Monte Carlo simulation, which had a time restriction of 0 to 6 h, showed that the best-performing limited sampling strategy was at 1 and 5 h after intravenous injection (60). In another pharmacokinetic model study using prospective data from 12 TB patients, it was observed that 2 g ertapenem once daily resulted in more than a dose-proportional increase in AUC compared to the results for 1 g ertapenem once daily. Based on a MIC of 1.0 mg/liter, 11 of 12 patients reached the target value of 40% Tfree > MIC (61).

DISCUSSION

Hugonnet and colleagues first stated that carbapenems have antimycobacterial activity (7). Subsequently, studies addressing the inactivation mechanism of LDT provided the underlying evidence to support the hypothesis of activity of carbapenems against M. tuberculosis (14–27). In spite of this, a series of in vitro studies have been carried out, some of which detected an effect and some of which did not (8, 30–48). Only later was it recognized that these confusing results are probably explained by the chemical instability of carbapenems in culture media at the temperatures typically used in in vitro studies, and many previously published in vitro studies are likely to have reported falsely high MICs (43).

Overall, the results of the studies identified in this review, which used a variety of experimental methods to test clinical and laboratory strains of M. tuberculosis for susceptibility to carbapenems, are consistent. Carbapenems are more active against M. tuberculosis if used in combination with clavulanate, a BLaC inhibitor (8, 30–48). In line with these in vitro studies, the addition of clavulanate improved the survival rate in mice (33). As the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has accepted and qualified the in vitro hollow-fiber-system models as a methodology to define pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) parameters, these modern in vitro studies can be used to avoid the problems associated with the chemical instability of these agents in standard agar-based MIC testing. Thus, hollow-fiber systems have the potential for dose-finding and regimen selection studies on the use of carbapenems in the treatment of TB (62, 63).

Few in vivo studies have been performed due to the short half-life and lower serum concentrations of carbapenems in mice (33).

One prospective, two observational, and seven retrospective clinical studies to assess the effectiveness, safety, and tolerability of three different carbapenems (imipenem, meropenem, and ertapenem) have been performed. Adverse events due to carbapenems were mild, confirming what we know from other infectious diseases but in contrast to other repurposed drugs, such as linezolid (53, 56, 58). To date, only two large retrospective studies with M/XDR-TB patients have been performed with imipenem (84 patients) and meropenem (96 patients) (11). Meropenem-clavulanate was suggested to be more efficient in managing M/XDR-TB (11); however, interpretational limitations were mentioned.

We found no clear evidence to select one particular carbapenem among the different candidate compounds when designing an effective M/XDR-TB regimen. Both economic and clinical factors play a role. Whereas imipenem is the less expensive carbapenem, ertapenem has the potential advantage that it is only given once daily, but while meropenem is believed by some authors to be the most effective in humans, no head-to-head comparison studies have confirmed this to date. Therefore, more clinical evidence and dose optimization substantiated by, for example, hollow-fiber infection studies are needed to support the repurposing of carbapenems for the treatment of M/XDR-TB.

Clinical studies are hampered by the fact that currently no combination of a carbapenem with clavulanate is commercially available. Furthermore, clavulanate is not available alone, so at present it is not practically possible to prescribe a carbapenem with clavulanate. Therefore, amoxicillin-clavulanate is often coadministered along with a carbapenem in cases where the latter is preferred for treatment. Unfortunately, amoxicillin has gastrointestinal side effects, potentially complicating prolonged treatment. Therefore, combined treatment of amoxicillin-clavulanate with a carbapenem is only an option for TB treatment of complicated cases showing multi- or extensive drug resistance (40). However, Gonzalo and Drobniewski (40) reported a potential benefit that MICs drop when amoxicillin is added to a combination of meropenem and clavulanate.

Due to different procedures, analytical methods, and design, the biochemical instability of the drugs of interest, the short half-live of drugs of interest in mice, diversity in MIC determinations, and intolerance, in addition to resistance, it was not possible to perform a meta-analysis. While the observational data are promising, carbapenems can only be recommended in the case of resistance to group A and group B drugs in M/XDR-TB treatment.

The ideal carbapenem would have the antimycobacterial activity of imipenem, the half-life of ertapenem, and the oral bioavailability of tebipenem-pivoxil. Due to increasing resistance observed in XDR-TB isolates (64, 65) and in MDR-TB patients with resistance to an aminoglycoside, carbapenems may be a valuable alternative to the current injectable second-line drugs. Assessment of both intracellular activity and activity against dormant M. tuberculosis bacteria by carbapenems is critical to further explore the potential of these repurposed drugs.

As the rates of successful treatment outcome for M/XDR-TB are still poor, ranging from 25% to 50% (1), improvement of the current treatment is urgently needed. An individual meta-analysis of data from 12,030 individual patients from 50 studies showed a significantly better treatment outcome for patients who received carbapenems than for patients who received other drugs traditionally used for treatment of MDR-TB (66). Since there is a need for new or repurposed drugs for the treatment of M/XDR-TB, phase II/III clinical trials are urgently needed for carbapenems to further evaluate their potential. Long-term safety and activity against M. tuberculosis are supported by observational data and several studies (39, 48, 67). A phase II prospective randomized controlled study evaluating a carbapenem plus a BLaC inhibitor on top of an optimized background regimen versus standard of care would be an appropriate strategy to test the potential benefits of carbapenems for M/XDR-TB treatment.

Conclusion.

Now that the variable results of in vitro studies have been explained and the activity of carbapenems in the presence of a BLaC inhibitor is established, these drugs should be further developed for the treatment of multi- and extensively drug-resistant M. tuberculosis. Ultimately, a well-designed phase II study is needed to substantiate the claimed benefits of carbapenems in patients with drug-resistant TB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PRISMA.

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (68).

Literature search.

In February 2018, a systematic literature search of PubMed and Web of Science, without restrictions with respect to publication date, was conducted using the following key words as MeSh terms: (“Carbapenem” OR “Carbapenems” OR “Imipenem” OR “Meropenem” OR “Ertapenem” OR “Doripenem” OR “Faropenem” OR “Biapenem” OR “Panipenem” OR “Tebipenem”) AND (“Tuberculosis” OR “TB” OR “Mycobacterium tuberculosis”). Studies and abstracts retrieved from both PubMed and Web of Science were pooled and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts of retrieved articles were screened. Reviews, case reports, or studies on species other than M. tuberculosis or studies on drugs other than carbapenems were excluded. Studies were screened for eligibility. If eligible, the full text was read by a researcher (S.P.V.R.). A second researcher (M.A.Z.) independently repeated the article search and selection. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion, or a third researcher was consulted (J.-W.C.A.). Full-text papers were subdivided into three sections: in vitro, in vivo, and clinical data. Full-text papers for in vitro data were eligible for inclusion if an M. tuberculosis strain was studied and MICs were reported. Full-text papers for in vivo data were eligible for inclusion if treatment of M. tuberculosis infections with carbapenems was studied in an animal model and if CFU and/or survival data were reported. Full-text papers for clinical data were eligible for inclusion if pharmacokinetics of carbapenems or safety or response to treatment measured as surrogate end points (sputum conversion) or clinical end points were studied and reported. The references of all articles included were screened by hand. The same systematic search was performed in February 2018 using clinicaltrials.gov to find ongoing studies investigating carbapenems in TB patients.

Data extraction.

A researcher (S.P.V.R.) performed data extraction first by using a structured data collection form. A second researcher (M.A.Z.) verified the data extraction independently. Data were subdivided into three sections: in vitro, in vivo, and clinical data. Variables in the in vitro section included the M. tuberculosis strain, experimental methods, and drug of interest. MIC, MIC with clavulanic acid, minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC), and CFU data were extracted from the included articles. For the in vivo section, the following data were included for retrieval from the included articles: M. tuberculosis strain, type of mice or other animal model, route of infection, drug of interest with or without clavulanic acid, dose and treatment, CFU, and survival rate. For the clinical section, we extracted data from the included articles on type of study population, number of subjects, study design, drug of interest, and dosage. Sputum smear, sputum culture, treatment success, adverse events, and interruption due to adverse events were noted as outcomes. AUC, peak drug concentration (Cmax), half-life (t1/2), volume of distribution (V), and clearance were extracted. The possibility of pooling data from included data was assessed upon presentation of data.

Data quality.

No validated tool for risk-of-bias assessment for in vitro studies, in vivo studies, and pharmacokinetic studies was available. To be able to assess the quality of each study, we verified whether each study reported on key elements required for adequate data interpretation. If studies reported adequately on the key elements, risk of bias was considered to be low. If studies had missing data or if procedures were not clear or not mentioned, risk of bias was considered to be high. The following key elements were identified for in vitro studies: description of laboratory or clinical strains, minimal sample size of >10 strains, >3 concentrations tested per drug, MIC/CFU determined using the proportion method, evaluation of MIC endpoint (MIC50 or MIC90), evaluation of minimal bactericidal concentration that kills 99% of replication culture (MBC99) as an endpoint, and CFU reduction. For in vivo studies, the key elements were description of laboratory or clinical strains, type of mice, route of administration of the drug, dose used, treatment duration, MIC/CFU determined using the proportion method, evaluation of CFU count as an endpoint, and survival rate. For clinical studies, the key elements for human studies were study design, patient population (TB/MDR-TB, HIV coinfection), number of study participants, endpoints tested, defined as sputum smear conversion, sputum culture conversion, or treatment success, and adverse events. The following components were checked for pharmacokinetic studies: sample size, type of patients, type of assay, number of plasma samples drawn per patient, sample handling, use of validated analytical methods, and method of AUC calculation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01489-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2017. Global tuberculosis report 2017. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/gtbr2017_main_text.pdf.

- 2.Falzon D, Schünemann HJ, Harausz E, González-Angulo L, Lienhardt C, Jaramillo E, Weyer K. 2017. World Health Organization treatment guidelines for drug-resistant tuberculosis, 2016 update. Eur Respir J 49:1602308. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02308-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen TVA, Anthony RM, Bañuls AL, Vu DH, Alffenaar JC. 2017. Bedaquiline resistance: its emergence, mechanism and prevention. Clin Infect Dis 66:1625–1630. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alsaad N, Wilffert B, van Altena R, de Lange WC, van der Werf TS, Kosterink JG, Alffenaar JW. 2013. Potential antimicrobial agents for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Eur Respir J 43:884–897. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00113713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Paardt AF, Wilffert B, Akkerman OW, de Lange WC, van Soolingen D, Sinha B, van der Werf TS, Kosterink JG, Alffenaar JW. 2015. Evaluation of macrolides for possible use against multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Eur Respir J 46:444–455. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00147014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. 2016. WHO treatment guidelines for drug-resistant tuberculosis. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.who.int/tb/areas-of-work/drug-resistant-tb/treatment/resources/en/. [PubMed]

- 7.Hugonnet JE, Blanchard JS. 2007. Irreversible inhibition of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis beta-lactamase by clavulanate. Biochemistry 46:11998–12004. doi: 10.1021/bi701506h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hugonnet J-E, Tremblay LW, Boshoff HI, Barry CE III, Blanchard JS. 2009. Meropenem-clavulanate is effective against extensively drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 323:1215–1218. doi: 10.1126/science.1167498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cynamon MH, Palmer GS. 1983. In vitro activity of amoxicillin in combination with clavulanic acid against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 24:429–431. doi: 10.1128/AAC.24.3.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Rijn SP, van Altena R, Akkerman OW, van Soolingen D, van der Laan T, de Lange WCM, Kosterink JGW, van der Werf TS, Alffenaar JWC. 2016. Pharmacokinetics of ertapenem in patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Eur Respir J 47:1229–1234. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01654-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tiberi S, Sotgiu G, D'Ambrosio L, Centis R, Abdo Arbex M, Alarcon Arrascue E, Alffenaar JW, Caminero JA, Gaga M, Gualano G, Skrahina A, Solovic I, Sulis G, Tadolini M, Alarcon Guizado V, De Lorenzo S, Roby Arias AJ, Scardigli A, Akkerman OW, Aleksa A, Artsukevich J, Auchynka V, Bonini EH, Chong Marín FA, Collahuazo López L, de Vries G, Dore S, Kunst H, Matteelli A, Moschos C, Palmieri F, Papavasileiou A, Payen M-C, Piana A, Spanevello A, Vargas Vasquez D, Viggiani P, White V, Zumla A, Migliori GB. 2016. Comparison of effectiveness and safety of imipenem/clavulanate- versus meropenem/clavulanate-containing regiments in the treatment of MDR- and XDR- TB. Eur Respir J 47:1758–1766. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00214-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deshpande D, Srivastava S, Bendet P, Martin KR, Cirrincione KN, Lee PS, Pasipanodya JG, Dheda K, Gumbo T. 2018. Antibacterial and sterilizing effect of benzylpenicillin in tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e02232-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02232-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deshpande D, Srivastava S, Chapagain M, Magombedze G, Martin KR, Cirrincione KN, Lee PS, Koeuth T, Dheda K, Gumbo T. 2017. Ceftazidime-avibactam has potent sterilizing activity against highly drug-resistant tuberculosis. Sci Adv 3:e1701102. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1701102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurz SG, Wolff KA, Hazra S, Bethel CR, Hujer AM, Smith KM, Xu Y, Tremblay LW, Blanchard JS, Nguyen L, Bonomo RA. 2013. Can inhibitor-resistant substitutions in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis beta-lactamase BLaC lead to clavulanate resistance? A biochemical rationale for the use of beta-lactam-beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:6085–6096. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01253-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavollay M, Arthur M, Fourgeaud M, Dubost L, Marie A, Veziris N, Blanot D, Gutmann L, Mainardi JL. 2008. The peptidoglycan of stationary-phase Mycobacterium tuberculosis predominantly contains cross-links generated by L,D-transpeptidation. J Bacteriol 190:4360–4366. doi: 10.1128/JB.00239-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar P, Arora K, Lloyd JR, Lee IY, Nair V, Fischer E, Boshoff HI, Barry CE III.. 2012. Meropenem inhibits D,D-carboxypeptidase activity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 86:367–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brammer Basta LA, Ghosh A, Pan Y, Jakoncic J, Lloyd EP, Townsend CA, Lamichhane G, Bianchet MA. 2015. Loss of functionally and structurally distinct LD-transpeptidase, LDtmt5, compromises cell wall integrity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem 290:25670–25685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.660753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cordillot M, Dubee V, Triboulet S, Dubost L, Marie A, Hugonnet JE, Arthur M, Mainardi JL. 2013. In vitro cross-linking of Mycobacterium tuberculosis peptidoglycan by L,D-transpeptidases and inactivation of these enzymes by carbapenems. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5940–5945. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01663-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubee V, Triboulet S, Mainardi JL, Etheve-Quelquejeu M, Gutmann L, Marie A, Dubost L, Hugonnet JE, Arthur M. 2012. Inactivation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis l,d-transpeptidase LdtMt(1) by carbapenems and cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:4189–4195. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00665-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erdemli SB, Gupta R, Bishai WR, Lamichhane G, Amzel LM, Bianchet MA. 2012. Targeting the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: structure and mechanism of L,D-transpeptidase 2. Structure 20:2103–2115. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar P, Kaushik A, Lloyd E, Li SG, Mattoo R, Ammerman NC, Bell DT, Perryman AL, Zandi TA, Ekins S, Ginell SL, Townsend CA, Freundlich JS, Lamichhane G. 2017. Non-classical transpeptidases yield insight into new antibacterials. Nat Chem Biol 13:54–61. doi: 10.1038/Nchemobio.2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lecoq L, Dubee V, Triboulet S, Bougault C, Hugonnet JE, Arthur M, Simorre JP. 2013. Structure of Enterococcus faecium l,d-transpeptidase acylated by ertapenem provides insight into the inactivation mechanism. ACS Chem Biol 8:1140–1146. doi: 10.1021/cb4001603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Triboulet S, Arthur M, Mainardi JL, Veckerle C, Dubee V, Nguekam-Moumi A, Gutmann L, Rice LB, Hugonnet JE. 2011. Inactivation kinetics of a new target of beta-lactam antibiotics. J Biol Chem 286:22777–22784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.239988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dubée V, Arthur M, Fief H, Triboulet S, Mainardi J-L, Gutmann L, Sollogoub M, Rice LB, Ethève-Quelquejeu M, Hugonnet J-E. 2012. Kinetic analysis of Enterococcus faecium L,D-transpeptidase inactivation of carbapenems. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:3409–3412. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06398-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HS, Kim J, Im HN, Yoon JY, An DR, Yoon HJ, Kim JY, Min HK, Kim SJ, Lee JY, Han BW, Suh SW. 2013. Structural basis for the inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis L,D-transpeptidase by meropenem, a drug effective against extensively drug-resistant strains. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 69:420–431. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912048998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoonmaker MK, Bishai WR, Lamichhane G. 2014. Nonclassical transpeptidases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis alter cell size, morphology, the cytosolic matrix, protein localization, virulence, and resistance to β-lactams. J Bacteriol 196:1394–402. doi: 10.1128/JB.01396-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Triboulet S, Dubée V, Lecoq L, Bougault C, Mainardi JL, Rice LB, Ethève-Quelquejeu M, Gutmann L, Marie A, Dubost L, Hugonnet JE, Simorre JP, Arthur M. 2013. Kinetic features of L,D-transpeptidase inactivation critical for β-lactam antibacterial activity. PLoS One 8:e67831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicolau DP. 2008. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of meropenem. Clin Infect DIS 47(Suppl 1):S32–S40. doi: 10.1086/590064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Craig WA. 2003. Basic pharmacodynamics of antibacterials with clinical applications to the use of beta-lactams, glycopeptides, and linezolid. Infect Dis Clin North Am 17:479–501. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5520(03)00065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chambers HF, Moreau D, Yajko D, Miick C, Wagner C, Hackbarth C, Kocagoz S, Rosenberg E, Hadley WK, Nikaido H. 1995. Can penicillins and other beta-lactam antibiotics be used to treat tuberculosis? Antimicrob Agents Chemother 39:2620–2624. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.12.2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaushik A, Makkar N, Pandey P, Parrish N, Singh U, Lamichhane G. 2015. Carbapenems and rifampicin exhibit synergy against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium abscessus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:6561–6567. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01158-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solapure S, Dinesh N, Shandil R, Ramachandran V, Sharma S, Bhattacharjee D, Ganguly S, Reddy J, Ahuja V, Panduga V, Parab M, Vishwas KG, Kumar N, Balganesh M, Balasubramanian V. 2013. In vitro and in vivo efficacy of β-lactams against replicating and slowly growing/nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:2506–2510. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00023-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Veziris N, Truffot C, Mainardi JL, Jarlier V. 2011. Activity of carbapenems combined with clavulanate against murine tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:2597–2600. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01824-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watt B, Edwards JR, Rayner A, Grindey AJ, Harris G. 1992. In vitro activity of meropenem and imipenem against mycobacteria: development of a daily antibiotic dosing schedule. Tuber Lung Dis 73:134–136. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(92)90145-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang D, Wang Y, Lu J, Pang Y. 2016. In vitro activity of β-lactams in combination with β-lactamase inhibitors against multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:393–399. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01035-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen KA, El-Hay T, Wyres KL, Weissbrod O, Munsamy V, Yanover C, Aharonov R, Shaham O, Conway TC, Goldschmidt Y, Bishai WR, Pym A. 2016. Paradoxical hypersusceptibility of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis to β-lactam antibiotics. EBioMedicine 9:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cavanaugh JS, Jou R, Wu MH, Dalton T, Kurbatova E, Ershova J, Cegielski JP. 2017. Susceptibilities of MDR Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates to unconventional drugs compared with their reported pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamics parameters. J Antimicrob Chemother 72:1678–1687. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.England K, Boshoff HIM, Arora K, Weiner D, Dayao E, Schimel D, Via LE, Barry CE. 2012. Meropenem-clavulanic acid shows activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:3384–3387. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05690-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forsman LD, Giske CG, Bruchfeld J, Schön T, Juréen P, Ängeby K. 2015. Meropenem-clavulanic acid has high in vitro activity against multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:3630–3632. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00171-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gonzalo X, Drobniewski F. 2013. Is there a place for beta-lactams in the treatment of multidrug-resistant/extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis? Synergy between meropenem and amoxicillin/clavulanate. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:366–369. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horita Y, Maeda S, Kazumi Y, Doi N. 2014. In vitro susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates to an oral carbapenem alone or in combination with β-lactamase inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:7010–7014. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03539-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sala C, Dhar N, Hartkoorn RC, Zhang M, Ha YA, Schneider P, Cole ST. 2010. Simple model for testing drugs against nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:4150–4158. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00821-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Srivastava S, van Rijn SP, Wessels AMA, Alffenaar JWC, Gumbo T. 2016. Susceptibility testing of antibiotics that degrade faster than the doubling time of slow-growing mycobacteria: ertapenem sterilizing effect of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:3193–3195. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02924-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Rijn SP, Srivastava S, Wessels MA, van Soolingen D, Alffenaar JW, Gumbo T. 2017. The sterilizing effect of ertapenem-clavulanate in a hollow fiber model of tuberculosis and implications on clinical dosing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02039-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02039-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deshpande D, Srivastava S, Nuermberger E, Pasipanodya JG, Swaminathan S, Gumbo T. 2016. A faropenem, linezolid, and moxifloxacin regimen for both drug-susceptible and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in children: FLAME Path on the Milky Way. Clin Infect Dis 63:S95–S101. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gurumurthy M, Verma R, Naftalin CM, Hee KH, Lu Q, Tan KH, Issac S, Lin W, Tan A, Seng K, Lee LS, Paton N. 2017. Activity of faropenem with and without rifampicin against Mycobacterium tuberculosis: evaluation in a whole-blood bactericidal activity trial. J Antimicrob Chemother 72:2012–2019. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dhar N, Dubee V, Ballell L, Cuinet G, Hugonnet JE, Signorino-Gelo F, Barros D, Arthur M, McKinney JD. 2015. Rapid cytolysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by faropenem, an orally bioavailable beta-lactam antibiotic. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:1308–1319. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03461-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Srivastava S, Deshpande D, Pasipanodya J, Nuermberger E, Swaminathan S, Gumbo T. 2016. Optimal clinical doses of faropenem, linezolid, and moxifloxacin in children with disseminated tuberculosis: Goldilocks. Clin Infect Dis 63:S102–S109. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaushik A, Ammerman AC, Tasneen R, Story-Roller E, Dooley KE, Dorman SE, Nuermberger EL, Lamichhane G. 2017. In vitro and in vivo activity of biapenem against drug-susceptible and rifampicin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Antimicrob Chemother 72:2320–2325. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chambers HF, Turner J, Schecter GF, Kawamura M, Hopewell PC. 2005. Imipenem for treatment of tuberculosis in mice and humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:2816–2821. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.7.2816-2821.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rullas J, Dhar N, Mckinney JD, Garcia-Pérez A, Lelievre J, Diacon AH, Hugonnet JE, Arthur M, Angulo-Barturen I, Barro-Aguirre D, Ballell L. 2015. Combinations of β-lactam antibiotics currently in clinical trials are efficacious in a DHP-I-deficient mouse model of tuberculosis infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:4997–4999. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01063-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arbex MA, Bonini EH, Kawakame Pirolla G, D’Ambrosio L, Centis R, Migliori GB. 2016. Effectiveness and safety of imipenem/clavulanate and linezolid to treat multidrug and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis at a referral hospital in Brazil. Rev Port Pneumol 22:337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.rppnen.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tiberi S, Sotgiu G, D’Ambrosio L, Centis R, Arbex MA, Arrascue EA, Alffenaar JW, Caminero JA, Gaga M, Gualano G, Skrahina A, Solovic A, Sulis G, Tadolini M, Guizado VA, De Lorenzo S, Arias AJR, Scardigli A, Akkerman OW, Aleksa A, Artsukevich J, Avchinko V, Bonini EH, Marín FAC, Collahuazo López L, de Vries G, Dore S, Kunst H, Matteelli A, Moschos C, Palmiere F, Papavasileiou A, Payen MC, Piana A, Spanevelo A, Vasquez DV, Viggiani P, White V, Zumla A, Migliori GB. 2016. Effectiveness and safety of imipenem/clavulanate added to an optimized background regimen (OBR) versus OBR control regimens in the treatment of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 62:1188–1190. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Payen MC, De Wit S, Martin C, Sergysels R, Muylle I, Van Laethem Y, Clumeck N. 2012. Clinical use of the meropenem-clavulanate combination for extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuber Lung Dis 16:558–560. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Payen MC, Muylle I, Vandenberg O, Mathys V, Delforge M, van den Wijngaert S, Clumeck N, De Wit S. 2018. Meropenem-clavulanate for drug-resistant tuberculosis: a follow-up of relapse-free cases. Int J Tuber Lung Dis 22:34–39. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.17.0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.De Lorenzo S, Alffenaar JW, Sotgiu G, Centis R, D'Ambrosio L, Tiberi S, Bolhuis MS, van Altena R, Viggiani P, Piana A, Spanevello A, Migliori GB. 2013. Efficacy and safety of meropenem-clavulanate added to linezolid-containing regimens in the treatment of MDR-/XDR-TB. Eur Respir J 41:1386–1392. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00124312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Palmero D, González Montaner P, Cufré M, García A, Vescovo M, Poggi S. 2014. First series of patients with XDR and pre-XDR TB treated with regimens that included meropenem-clavulanate in Argentina. Arch Bronconeumol 51:e49–e52. doi: 10.1016/j.arbr.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tiberi S, Payen M-C, Sotgiu G, D'Ambrosio L, Alarcon Guizado V, Alffenaar JW, Abdo Arbex M, Caminero JA, Centis R, De Lorenzo S, Gaga M, Gualano G, Roby Arias AJ, Scardigli A, Skrahina A, Solovic I, Sulis G, Tadolini M, Akkerman OW, Alarcon Arrascue E, Aleska A, Avchinko V, Bonini EH, Chong Marín FA, Collahuazo López L, de Vries G, Dore S, Kunst H, Matteelli A, Moschos C, Palmieri F, Papavasileiou A, Spanevello A, Vargas Vasquez D, Viggiani P, White V, Zumla A, Migliori GB. 2016. Effectiveness and safety of meropenem/clavulanate-containing regimens in the treatment of MDR- and XDR-TB. Eur Respir J 47:1235–1243. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02146-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tiberi S, D'Ambrosio L, De Lorenzo S, Viggiani P, Centis R, Sotgiu G, Alffenaar JWC, Migliori GB. 2016. Ertapenem in the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: first clinical experience. Eur Respir J 47:333–336. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01278-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Rijn SP, Zuur MA, van Altena R, Akkerman OW, Proost JH, de Lange WCM, Kerstjens HAM, Touw DJ, van der Werf TS, Kosterink JGW, Alffenaar JWC. 2017. Pharmacokinetic modeling and limited sampling strategies based on healthy volunteers for monitoring of ertapenem in patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01783-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01783-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zuur M, Ghimire S, Bolhuis MS, Wessels AMA, van Altena R, de Lange WCM, Kosterink JGW, Touw DJ, van der Werf TS, Akkerman OW, Alffenaar JWC. 2018. The pharmacokinetics of 2000 mg Ertapenem in tuberculosis patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e02250-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02250-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cavaleri M, Manolis E. 2015. Hollow fiber system for tuberculosis: the European Medicines Agency experience. Clin Infect Dis 61(Suppl 1):S1–S4. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.European Medicines Agency. 2016. Qualification opinion; in-vitro hollow fiber system model of tuberculosis (HSF-TB). EMA/CHMP/SAWP/47290/2015. European Medicines Agency, London, United Kingdom.

- 64.Drusano GL, Sgambati N, Eichas A, Brown DL, Kulawy R, Louie A. 2010. The combination of rifampin plus moxifloxacin is synergistic for suppression of resistance but antagonistic for cell kill of Mycobacterium tuberculosis as determined in a hollow-fiber infection model. mBio 1:e00139-10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00139-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gumbo T, Louie A, Deziel MR, Parsons LM, Salfinger M, Drusano GL. 2004. Selection of a moxifloxacin dose that suppresses drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, by use of an in vitro pharmacodynamic infection model and mathematical modeling. J Infect Dis 190:1642–1651. doi: 10.1086/424849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ahmad Khan F, Salim MAH, Du Cros P, Casas EC, Kharmraev A, Sikhondze W, Benedetti A, Bastos M, Lan Z, Jaramillo E, Falzon D, Menzies D. 2017. Effectiveness and safety of standardised shorter regimens for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: individual patient data and aggregate data meta-analyses. Eur Respir J 50:1700061. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00061-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Magis-Escurra C, Anthony RM, van der Zanden AGM, van Soolingen D, Alffenaar J-WC. 2018. Pound foolish and penny wise—when will dosing of rifampicin be optimised? Lancet Resp Med 6:e11–e12. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.