Abstract

CD97 shows a strong relationship with metastasis and poor clinical outcome in various tumors, including ovarian cancer. The expression of CD97 in metastatic ovarian cancer cells was higher than that in primary ovarian cancer cells. Mature miRNAs are frequently de-regulated in cancer and incorporated into a specific mRNA, leading to post-transcriptional silencing. In this study, we investigated whether the miR-503-5p targeting of the CD97 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) contributes to ovarian cancer metastasis as well as the underlying mechanism regulating cancer progression. In LPS-stimulated or paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells, stimulation with recombinant human CD55 (rhCD55) of CD97 in ovarian cancer cells activated NF-κB-dependent miR-503-5p down-regulation and the JAK2/STAT3 pathway, consequently promoting the migratory and invasive capacity. Furthermore, restoration of miR-503-5p by transfection with mimics or NF-κB inhibitor efficiently blocked CD97 expression and the downstream JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Target inhibition of JAK with siRNA also impaired colony formation and metastasis of LPS-stimulated and paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells. Taken together, these results suggest that high CD97 expression, which is controlled through the NF-κB/miR-503-5p signaling pathway, plays an important role in the invasive activity of metastatic and drug-resistant ovarian cancer cells by activating the JAK2/STAT3 pathway.

Abbreviations: JAK2, Janus-activated kinase 2; STAT3, Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; LPS, Lipopolysaccharide; rhCD55, Recombinant human CD55; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; MMP, Matrix metalloproteinase 2

Introduction

CD97, which is generally up-regulated on the surfaces of activated lymphocytes, is a member of the epidermal growth factor (EGF)-seven transmembrane family [1], [2]. CD97 is also highly expressed in gastric, esophageal, and pancreatic cancer [3]. Although the relevance between the levels of CD97 and the clinical outcome of the patients is still controversial [3], CD97 expression has been implicated in tumor aggressiveness and lymph node metastasis due to interactions with the extracellular matrix and integrin α5β1 [4]. In addition, elevated expression of CD97 and its ligand CD55 at the invasion front is correlated with tumor recurrence and metastasis in colorectal cancer [5]. CD97 is highly associated with poor progression-free survival [6] and expressed at higher levels in recurrent post-chemotherapy ovarian tumors compared to primary tumors [7]. However, the induction and contribution of CD95/CD55 in ovarian cancer metastasis after chemotherapy remain unknown.

The activation of Janus-activated kinase 2(JAK2)/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) delivers the effects of variable growth factors and cytokines (IL-6, GSF-G, and EGF) [8], [9]. Furthermore, the JAK2/STAT3 pathway is constitutively active in many tumors, including ovarian cancer [9], [10]. In high-grade serous ovarian cancer cell lines (OVCA433 and SKOV3), stimulation with EGF or IL-6 results in the promotion of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and peritoneal spread through the activation of JAK2/STAT3 and downstream targets [11]. However, whether CD97-mediated signaling in ovarian cancer cells facilitates the JAK2/STAT3 pathway for EMT processes remains elusive.

MicroRNAs (miRs) is a small non-coding RNA family that regulates the expression of hundreds of coding genes, which modulate several cellular pathways, including proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, and migration [12]. Binding to the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of specific mRNAs results in blocking translation and mRNA degradation [12], [13]. Although the precise biological functions of miRNAs are not yet fully understood, the dysregulation of miRs has been observed in various human cancers [14]. Down-regulation of miR-126 induces the overexpression of CD97 in breast cancer cells, leading to the promotion of migratory and invasive activity [15]. Although a number of microRNAs derived from exosome of gastric cancer cells are involved in the induction of CD97 and metastasis [42], the effect of microRNA on CD97 expression and related signaling pathway in ovarian cancer have not been fully investigated. The level of miR-503 is down-regulated by gonadotropin stimulation in follicular developmental stage but up-regulated before ovulation [17], [18]. However, the level of miR-503 is up-regulated in aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1)-positive chemoresistant ovarian cancer cells [19]. Based on these results, the precise roles of miR-503 may be changed in a cell type-dependent manner or developmental stage, and putative targets of miR-503 remain controversial in drug-resistant ovarian cancer.

Initial chemotherapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin against ovarian cancer eventually fails in more than 80% of patients due to the development of resistance to these drugs [20]. Stimulation with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of epithelial ovarian cancer induces proliferation and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines through the activation of MyD88-NF-κB signaling pathway [21]. Despite the structural discrepancy between paclitaxel and LPS, binding LPS, as paclitaxel, to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on ovarian cancer cells subsequently promotes the development of chemoresistance and induction of metastasis [22], [23]. TLR and microRNA are also usually associated with promotion of cancer progression via the activation of JAK-STAT3 pathway [24]. However, little is known about the connection miR-503-5p with CD97 expression in LPS-stimulated or paclitaxel resistant ovarian cancer cells.

Based on the results of a search using microarray with LPS-activated ovarian cancer cells, we firstly identified a variety of microRNAs up-regulated or down-regulated in LPS-exposed ovarian cancer compared to non-stimulated ovarian cancer cells. In addition, we investigated whether up-regulated CD97 plays a critical role in metastasis of ovarian cancer and examined the association between CD97 and the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway in LPS-stimulated or paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells in this study. We also studied the regulatory effect of miR-503 on CD97 expression to control ovarian cancer metastasis.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and Chemicals

The human ovarian cancer cell lines CaOV3, SKOV3, OVCAR3, and OV90 were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). The CaOV3 and OV90 cells were maintained in DMEM medium (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (RMBIO, Missoula, MT, USA), penicillin, streptomycin, and glutamine at 37 °C in 5% CO2. The SKOV3 cells were maintained in McCoy's 5A medium (Corning Incorporated) supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin, streptomycin, and glutamine at 37 °C in 5% CO2. All purchased cells were authenticated by the supplier by short tandem repeat profiling. Paclitaxel-resistant sublines (CaOV3/PTX-R and SKOV3/PTX-R) were established from the parent cell lines, CaOV3 and SKOV3, respectively, by continuous exposure of the cells to a stepwise escalating concentration of PTX, ranging between 2.5 and 50 nM of PTX over 6 months. The authentication of all cell lines used in this study had confirmed using Short Tandem Repeat (STR) DNA profiling analysis according to the ANSI Standard (ASN-0002) by the ATCC Standards Development Organization (SDO). LPS (TLR4 ligand) and paclitaxel were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Recombinant CD55 was obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Bay 11–7082 (NF-κB inhibitor) was obtained from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA).

MicroRNA Microarray Assay

Total RNA from LPS-treated SKOV3 was isolated using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, CA, USA). RNA purity and integrity were evaluated by ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Wilmington, USA), Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The Affymetrix Genechip miRNA 4.0 array process was executed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 1000 ng RNA samples were labeled with the FlashTag™ Biotin RNA Labeling Kit (Genisphere, Hatfield, PA, USA). The labeled RNA was quantified, fractionated and hybridized to the miRNA microarray according to the standard procedures provided by the manufacture. The labeled RNA was heated to 99 °C for 5 minutes and then to 45 °C for 5 minutes. RNA-array hybridization was performed with agitation at 60 rotations per minute for 16 hours at 48 °C on an Affymetrix® 450 Fluidics Station. The chips were washed and stained using a Genechip Fluidics Station 450 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The chips were then scanned with an Affymetrix GCS 3000 canner (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Signal values were computed using the Affymetrix® GeneChip™ Command Console software (AGCC). Extracted array data were filtered by probes annotated species. The comparative analysis between test sample and control sample was carried out using fold-change. All Statistical test and visualization of differentially expressed genes was conducted using R statistical language v. 3.1.2.

Small Interfering RNA (siRNA) Transfection

Experimentally verified human CD97-, human JAK2-small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplex, negative control-siRNA, miR-503 mimic, mimic control, miR-503-5p inhibitor, and inhibitor control were obtained from Bioneer (Daejeon, Republic of Korea). Cells were seeded at a concentration of 1 × 105 per well in a 6-well plate and grown overnight. Cells were subsequently transfected with 200 nM of siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were used for further experiments at 48 h after transfection.

Migration and Invasion Assay

The transendothelial migration of colon cancer cells was detected using the CytoSelectTM tumor transendothelial migration assay kit (Cell Biolabs, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The relative fluorescence units (RFU) of the migrated cells were measured by a microplate reader. The invasion assay was performed using the CultreCoat 96-well Medium BME Cell Invasion Assay Kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Invaded cells were stained with calcein-AM and quantified using a microplate reader.

Soft agar Colony-Forming Assay

Culture anchorage-independent growth was analyzed by performing colony-forming assays in soft agar. Cells (1 × 104) were suspended in 1 ml of complete medium containing 0.3% agar and plated over a layer of 0.6% agar in complete medium. Cells were incubated at 37 °C for 2 weeks, and then colonies were stained with 300 μl of methylthiazole tetrazolium (MTT, Sigma-Aldrich). Colonies with a diameter greater than 0.5 mm were counted under a microscope.

MiRNA Detection Using Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA using the Mir-XTM miRNA First-Strand Synthesis Kit (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). The miRNA levels were quantitated using an ABI7300 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and SYBR Green Master Mix Kit (Takara, Tokyo, Japan) with a miRNA-specific 5′primer (has-miR-503-5p; CTG CAG AAC TGT TCC CGC TGC) and the mRQ 3’primer supplied with the Kit for all miRNAs. The U6-specific primer set supplied with the Kit was used as an internal control for miRNA. The relative mRNA quantification was calculated using the arithmetic formula 2-△△Cq, where △Cq is the difference between the threshold cycle of a given target cDNA and an endogenous reference cDNA.

Immunoblotting

Cells were washed in PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer (Elpis Biotech, Daejeon, Korea) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Protein phosphorylation states were preserved through the addition of phosphatase inhibitors (Cocktail II, Sigma-Aldrich) to NP-40 buffer. Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The proteins (10 μg/sample) were resolved through SDS-PAGE and subsequently transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk prior to Western blot analysis. Chemiluminescence was detected using an ECL kit (Advansta Corp., Menlo Park, CA, USA) and the Amersham Imager 600 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, UK). Primary antibodies against the following proteins were used: phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705), STAT3, β-actin, MMP2, MMP9, PARP, p105/p50, p100/p52, p65, and Rel-B (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA); phospho-JAK2 (Tyr221) and JAK2 (Bioss, Woburn, MA, USA); CD55 (Biorbyt, Woburn, MA, USA); β-tubulin (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA); and E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Snail, and CD97 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Detection of NF-κB Translocation by Fractionation

Cytosol and nuclear cellular fractions were prepared using the Nuclear/Cytosol Fractionation Kit (BioVision, Mountain View, CA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, cells (2 × 106) were harvested and suspended in 200 μl of cytosol extraction buffer A. After incubation on ice for 10 min, cytosol extraction buffer B was added to the cell suspension, followed by incubation on ice for 1 min. Subsequently, the supernatants were obtained by centrifugation and designated as cytosolic fractions. The pellets were re-suspended in 100 μl of nuclear extraction buffer mix and designated nuclear fractions. For certain experiments, the cells were treated with the NF-κB inhibitor Bay11–7082 (5 μM).

Measurement of NF-κB Activity by NF-κB DNA-Binding ELISA

To quantify the DNA-binding activity of NF-κB, the NF-κB p50/p65 Transcription Factor Assay Kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, nuclear extracts were transferred to a 96-well plate coated with a specific ds DNA sequence containing the NF-κB response element. NF-κB proteins bound to the target sequence were detected with a primary antibody and a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm as a relative measure of protein-bound NF-κB. All fractions were stored at −80 °C until further use.

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as the means ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way analysis of variance. A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The CD97-Related Signaling Pathway Regulates the Metastasis of LPS-Stimulated Ovarian Cancer Cells

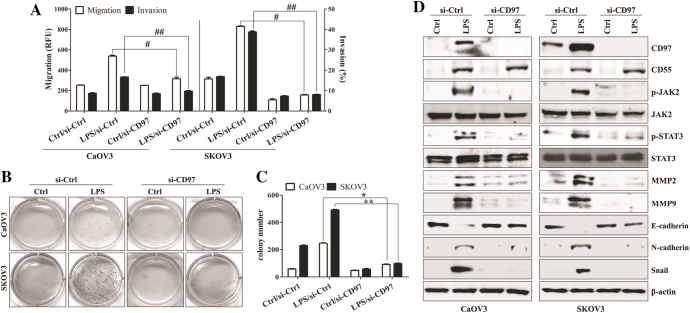

Among four different ovarian cancer cell lines (OVCAR3, CaOV3, SKOV3, and OV90), CD97 expression was only detected at the mRNA level in the intracellular compartments of OV90 and SKOV3 cells under non-stimulated conditions (Supplemental Fig. 1A and 1B). Despite bacterial LPS or paclitaxel activates similar signaling pathway [22], Exposure to paclitaxel induced the apoptosis of paclitaxel-sensitive CaOV3 and SKOV3 [22]. From these reason, we stimulated ovarian cancer cells with LPS for enhancing the CD97 expression and defining the role of CD97. The levels of CD97 and mesenchymal markers were enhanced and identified on the surfaces of LPS-treated CaOV3 and SKOV3 cells (Supplemental Fig. 1C-1F). LPS-stimulated ovarian cancer cells promoted the secretion of metastasis-related cytokines (Supplemental Fig. 1G). Additionally the down-regulation of CD97 significantly inhibited the migratory and invasive activity of SKOV3 and OV90 cells (Supplemental Fig. 1H-1I) and LPS-exposed CaOV3 and SKOV3 cells (Figure 1A). According to the expression of CD97 and clinicopathological features [25], we selected CaOV3 cells as a representative model of primary tumor and SKOV3 cells as an in vitro model for metastatic ovarian cancer cells. In colony formation assay, the cell growth of LPS-stimulated cancer cells was significantly inhibited in CD97-knockdown ovarian cancer cells compared to that of the cells transfected control siRNA (Figure 1, B and C). Gene silencing of CD97 with siRNA efficiently prevented the up-regulation of CD97, phosphorylation of JAK2/STAT3, expression of matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2) and MMP9, and induction of mesenchymal markers in LPS-stimulated SKOV3 cells (Figure 1D). LPS treatment induced the expression of CD55, whereas CD97 targeting had no effect on the expression of CD55 in ovarian cancer cells (Figure 1D). These results suggest that CD97 expression plays an important role in the activation of the metastasis-related signaling pathway in ovarian cancer cells.

Figure 1.

Knockdown of CD97 in LPS-stimulated ovarian cancer cells leads to decreased invasion and down-regulation of JAK2, STAT3, and MMP2/9. Cells (1.5 × 105/well) were seeded onto 6-well plates and grown overnight. Cells were transfected with siRNA against CD97 or control for 36 h and then treated with TLR4 agonist LPS (500 ng/ml) for 24 h. (A) The migratory activity and invasiveness of cells were detected by the tumor transendothelial migration assay kit and the BME cell invasion assay kit, respectively, as described in the Materials and Methods. #, P < .01. ##, P < .01. (B) Colony-forming assay. Cells were cultivated for 2 weeks in a 6-well plate with soft agar. After 2 weeks, the cells were stained with MTT solution. Colonies were counted after reaching at least 0.5 mm in diameter. (C) The graph shows the quantitative analysis of the colony-forming assay. *, P < .005. **, P < .005. Each value represents the mean ± SD of the three determinations. (D) Total cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. β-actin was used as a loading control. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

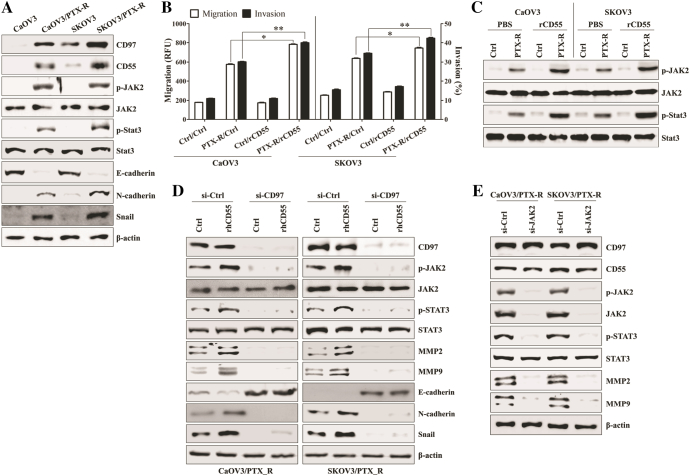

CD97/CD55 Interaction Stimulates JAK2/STAT3-Mediated Metastasis of LPS-Stimulated Ovarian Cancer Cells

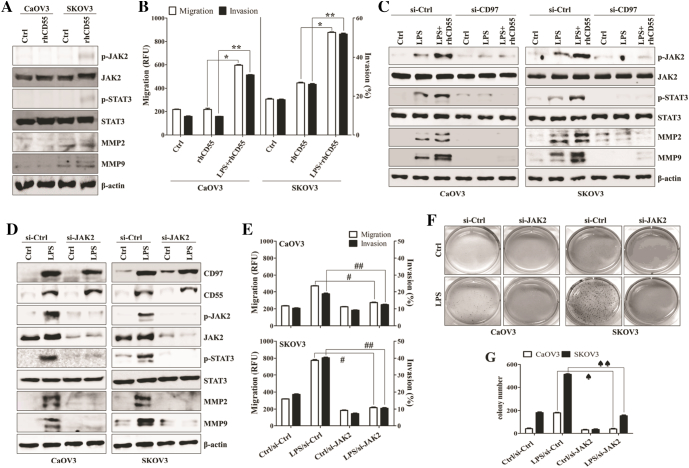

We next investigated whether the interaction between enhanced CD97 and its ligand CD55 induces the activation of JAK2/STAT3 signaling and the related migratory or invasive activity of ovarian cancer cells. Although the direct stimulation of CD97 with recombinant human CD55 (rhCD55) induced the weak activation of JAK2, STAT3, MMP2, and MMP9 in the absence of LPS (Figure 2A), co-stimulation with rhCD55 and LPS significantly provoked the migration and invasion capacity of ovarian cancer cells (Figure 2B). However, the targeted inhibition of CD97 attenuated the induction of phosphorylated JAK2 and STAT3 as well as expression of MMP2 and MMP9 by stimulation with rhCD55 (Figure 2C). Knockdown of JAK2 resulted in blocking the activation of STAT3, MMP2, and MMP9 in LPS-treated ovarian cancer cells (Figure 2D). In addition, silencing JAK via siRNA profoundly blocked the metastatic activity (Figure 2E) and colony formation (Figure 2, F and G) of LPS-activated ovarian cancer cells. These results suggest that the CD97/CD55-mediated JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway enhances the metastasis of LPS-stimulated ovarian cancer cells.

Figure 2.

CD97/CD55 interaction induces JAK2/STAT3-mediated metastasis of LPS-stimulated ovarian cancer cells. (A) Cells (1.5 × 105/well) were cultured with recombinant human CD55 (1 μg/ml) for 24 h. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (B) Cells (1.5 × 105/well) were cultured with recombinant human CD55 (1 μg/ml) and LPS (500 ng/ml) for 24 h. The migratory activity and invasiveness of cells were detected by the tumor transendothelial migration assay kit and the BME cell invasion assay kit, respectively, as described in the Materials and Methods. *, P < .01. **, P < .01. (C) Cells (1.5 × 105/well) were seeded onto 6-well plates and grown overnight. Cells were transfected with siRNA against CD97 or control for 36 h and then treated with recombinant human CD55 (1 μg/ml) and LPS (500 ng/ml) for 24 h. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (D-G) Cells (1.5 × 105/well) were seeded onto 6-well plates and grown overnight. Cells were transfected with siRNA against JAK2 or control for 36 h and then treated with LPS (500 ng/ml) for 24 h. (D) Total cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. β-actin was used as a loading control. (E) The migratory activity and invasiveness of cells were detected by the tumor transendothelial migration assay kit and the BME cell invasion assay kit, respectively, as described in the Materials and Methods. #, P < .01. ##, P < .01. (F) Colony-forming assay. Cells were cultivated for 2 weeks in a 6-well plate with soft agar. After 2 weeks, the cells were stained with MTT solution. Colonies were counted after reaching at least 0.5 mm in diameter. (G) The graph shows the quantitative analysis of the colony-forming assay. ♠, P < .005. ♠♠, P < .005. Each value represents the mean ± SD of the three determinations. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

The NF-κB-Mediated miR-503-5p Down-Regulation Enhances the CD97-Induced Metastasis of LPS-Stimulated Ovarian Cancer Cells

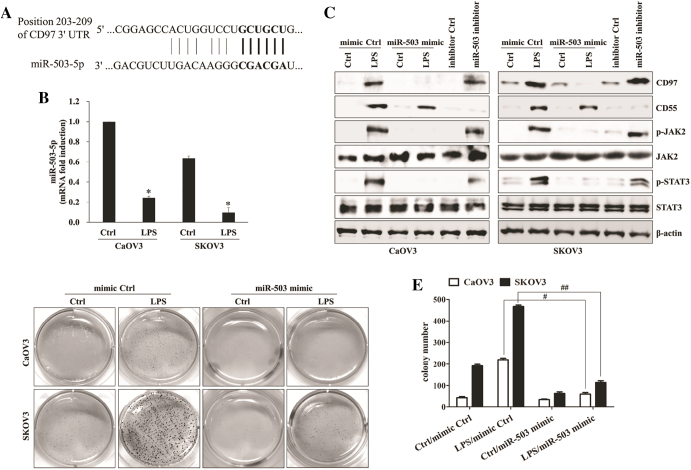

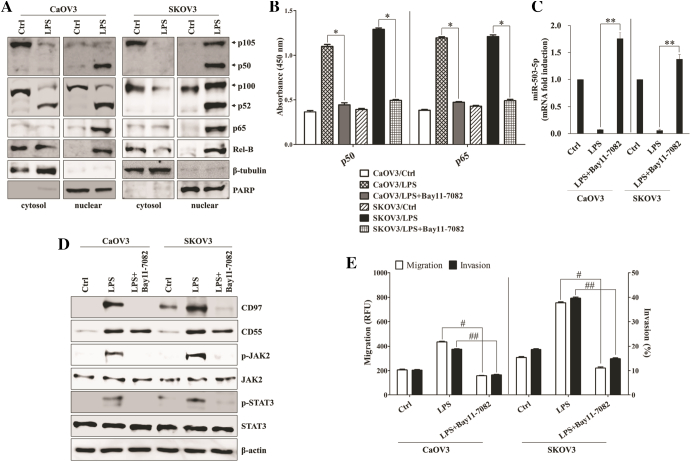

To determine whether dysregulated microRNAs (miRs) were relevant to expression of CD97 in LPS-treated or paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer, we first compared the microRNA profiles of LPS-stimulated SKOV3 with non-treated SKOV3 through the analysis of microarray assay. The level of miR-503-5p was down-regulated in response to the stimulation of LPS in SKOV3 (Supplemental Table 1). We next investigated whether miR-503 regulates the expression of CD97 and related signaling pathway in LPS-stimulated ovarian cancer cells. The binding of miR-503-5p to the target site in 3´-UTR of CD97 was detected by sequence analysis (Figure 3A). Furthermore, down-regulation of miR-503-5p expression in LPS-activated ovarian cancer cells was identified by real-time quantitative PCR analysis (Figure 3B). After checking transfection efficiency of miR-503-5p mimic and miR-503-5p inhibitor (Supplemental Fig. 2A), the miR-503-5p synthetic mimic or miR-503-5p inhibitor was transfected into ovarian cancer cells. Targeted inhibition with miR-503-5p inhibitor significantly increased the growth and colony formation (Supplemental Fig. 2B and 2C), up-regulated CD97 expression (Figure 3C), enhanced JAK2/STAT3 phosphorylation (Figure 3C), and increased the migratory capacity (Supplemental Fig. 2D) of ovarian cancer cells in the absence of LPS treatment. Additionally, transfection of miR-503-5p mimic into LPS-activated ovarian cancer cells inhibited the expression of CD97 and phosphorylated JAK2/STAT3 proteins (Figure 3C), blocked colony-forming activity (Figure 3, D and E) and metastatic activity (Supplemental Fig. 2D), and reduced the production of metastasis-related cytokines (Supplemental Fig. 2E). In addition, treatment of epithelial cells with LPS reduced the expression of miR-503 through activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway [26]. Next, we explored the role of the NF-κB pathway for the regulation of miR-503 and CD97 expression in LPS-stimulated ovarian cancer cells. Treatment of ovarian cancer cells with LPS resulted in the activation of key components p50, p52, p65, and Rel-B of NF-κB as well as nuclear translocation in nuclear fractions (Figure 4A). NF-κB inhibitor (Bay-11-7082) not only attenuated NF-κB activation through both canonical (p50) and non-canonical (p65) pathways (Figure 4B) but also prevented the down-regulation the level of miR-503-5p in LPS-treated ovarian cancer cells (Figure 4C). Furthermore, Bay-11-7082 prevented the expression of CD97 and phosphorylated JAK2/STAT3 (Figure 4D) as well as the migration and invasion activity of LPS-activated ovarian cancer cells (Figure 4E). These results suggest that the LPS-mediated NF-κB pathway regulates the miR-503-5p-associated CD97 expression and ovarian cancer cell metastasis.

Figure 3.

miR-503-5p binds directly to the 3’UTRs of CD97 and LPS-induced miR-503-5p down-regulation enhances invasion. (A) A schematic of the putative miR-503-5p binding sites on CD97 3′-UTR. (B) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qPCR) was performed to determine the relative expression of miR-503-5p in LPS-treated ovarian cancer cells. *, P < .05. (C-E) Cells (1.5 × 105/well) were seeded onto 6-well plates and grown overnight. Cells were transfected with miR-503-5p mimic or mimic control for 36 h and then treated with LPS (500 ng/ml) for 24 h. Some cells were transfected with miR-503-5p inhibitor or inhibitor control for 48 h. (C) Total cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. β-actin was used as a loading control. (D) Colony-forming assay. Cells were cultivated for 2 weeks in a 6-well plate with soft agar. After 2 weeks, the cells were stained with MTT solution. Colonies were counted after reaching at least 0.5 mm in diameter. (E) The graph shows the quantitative analysis of the colony-forming assay. #, P < .01. ##, P < .01. Each value represents the mean ± SD of the three determinations. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 4.

NF-κB-mediated miR-503-5p down-regulation increases the CD97-induced JAK2/STAT3 expression and invasion. (A) Cells (1.5 × 105/well) were cultured with LPS (500 ng/ml) for 24 h. Cytosolic extracts or nuclear extracts were analyzed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. A nuclear marker, PARP, and cytosol marker, β-tubulin, were used to verify the purity of each fraction. Fractionation was performed as described in the Materials and Methods. (B-E) Cells (1.5 × 105/well) were pretreated with Bay 11–7082 (5 μM) for 1 h and then treated with LPS (500 ng/ml) for 24 h. (B) ELISA measured NF-κB DNA-binding activity in nuclear extracts. Transcription factor NF-κB p50 combo and p65 combo (in Kit) served as positive controls for NF-κB activity. ELISA results are expressed as relative absorbance. *, P < .01. Data represent the mean ± SD of the three independent experiments. (C) QPCR was performed to determine the relative expression of miR-503-5p in LPS and Bay 11–7082 (5 μM)-treated ovarian cancer cells. **, P < .05. (D) Total cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. β-actin was used as a loading control. (E) The migratory activity and invasiveness of cells were detected by the tumor transendothelial migration assay kit and the BME cell invasion assay kit, respectively, as described in the Materials and Methods. #, P < .005. ##, P < .005. Each value represents the mean ± SD of the three determinations. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

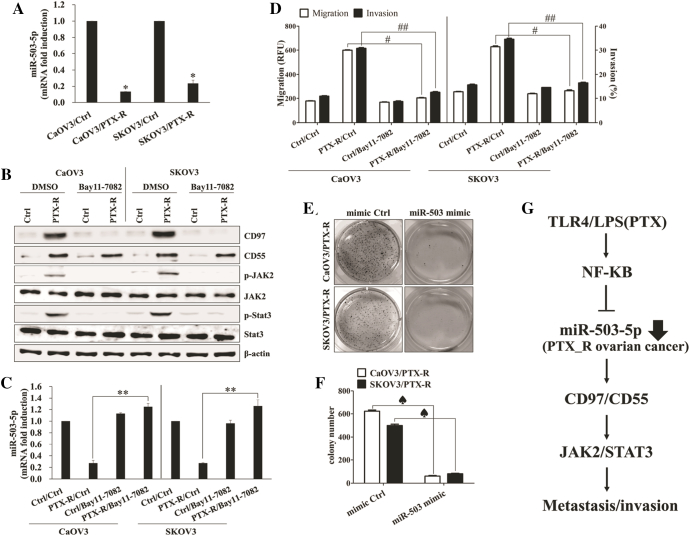

The Level of miR-503-5p Modulates CD97-Mediated Metastasis of Paclitaxel-Resistant Ovarian Cancer Cells

Recurrent ovarian cancer after standard chemotherapy with paclitaxel plus platinum becomes resistant to these chemotherapeutic agents [27]. Since the development of resistance to paclitaxel in human ovarian cancer occurs through a mechanism involving the TLR4 [21], [22], we next investigated whether the CD97 expression and related pathway involve cancer metastasis in paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells. Paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells not only enhanced the expression of CD97/CD55 and related signaling pathways (Supplemental Fig. 3A and Figure 5A) but also increased the expression of mesenchymal markers and migratory activity (Figure 5, A and B) in the absence of LPS stimulation. Stimulation with rhCD55 amplified the activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway (Figure 5C) as well as migration capacity (Figure 5B) and promoted the secretion of metastasis-related cytokines in paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells (Supplemental Fig. 3B). The down-regulation of CD97 using siRNA transfection prevented the activation of JAK/STAT3 and MMP2/9 and blocked the expression of mesenchymal markers by stimulation with rhCD55 (Figure 5D). Furthermore, the targeted inhibition of JAK2 reduced the activation of STAT3, MMP2 and MMP9 (Figure 5E). The constitutively activated NF-κB pathway (Supplemental Fig. 3C) led to suppression of miR-503-5p (Figure 6A), resulting in the enhancing CD97 expression (Figure 6B) and activating the JAK2/STAT3 (Figure 6B) pathway in paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells. Additionally, treatment with the NF-κB inhibitor of paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells prevented JAK2/STAT3 phosphorylation (Figure 6B), down-regulated CD97 expression (Figure 6B), and reversed miR-503-5p expression (Figure 6C), resulting in the inhibition of migratory or invasive activity (Figure 6D) and the reduction of metastasis-related cytokines production (Supplemental Fig. 4A). In addition, transfection with the miR-503-5p mimic profoundly attenuated the colony-forming activity of paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells (Figure 6, E and F) as well as the production of metastasis-associated cytokines (Supplemental Fig. 4B). These results suggest that NF-κB-mediated miR-503-5p suppression plays a critical role in CD97 expression and the related JAK2/STAT3 pathway for enhancing the metastasis of paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells.

Figure 5.

CD97/CD55 interaction elicits JAK2/STAT3-mediated metastasis of paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells. (A) Total lysates of PTX-sensitive or PTX-resistant cells were collected and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (B, C) Cells (1.5 × 105/well) were cultured with recombinant human CD55 (1 μg/ml) for 24 h. (B) The migratory activity and invasiveness of cells were detected by the tumor transendothelial migration assay kit and the BME cell invasion assay kit, respectively, as described in the Materials and Methods. *, P < .005. **, P < .005. Each value represents the mean ± SD of the three determinations. (C) Total cell lysates were collected and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (D) Cells (1.5 × 105/well) were seeded onto 6-well plates and grown overnight. Cells were transfected with siRNA against JAK2 or control for 48 h. Total cell lysates were collected and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. β-actin was used as a loading control. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 6.

The level of miR-503-5p modulates CD97-mediated metastasis of paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells. (A) qPCR was performed to determine the relative expression of miR-503-5p in PTX-sensitive or PTX-resistant ovarian cancer cells. *, P < .05. (B-D) Cells (1.5 × 105/well) were treated with Bay 11–7082 (5 μM) for 1 h, washed out, and then cultured for 24 h. (B) Total cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. β-actin was used as a loading control. (C) the levels of miR-503-5p in PTX-sensitive or PTX-resistant ovarian cancer cells were measured using qPCR. **, P < .05. (D) The migratory activity and invasiveness of cells were detected by the tumor transendothelial migration assay kit and the BME cell invasion assay kit, respectively, as described in the Materials and Methods. #, P < .005. ##, P < .005. (E, F) Cells (1.5 × 105/well) were seeded onto 6-well plates and grown overnight. Cells were transfected with miR-503-5p mimic or mimic control for 48 h. (E) Colony-forming assay. Cells were cultivated for 2 weeks in a 6-well plate with soft agar. After 2 weeks, cells were stained with MTT solution. Colonies were counted after reaching at least 0.5 mm in diameter. (F) The graph shows the quantitative analysis of the colony-forming assay. ♠, P < .01. Each value represents the mean ± SD of the three determinations. The results are representative of three independent experiments. (G) Schematic diagram of the intracellular signaling pathway in TLR4 agonist-treated human ovarian cancer cells. TLR4 stimulation triggers NF-κB activation in ovarian cancer cells. Subsequent suppression of miR-503-5p results in the increase of CD97 and CD55 expression. The interaction of CD97 and CD55 leads to JAK2/STAT3-mediated invasion in LPS-treated ovarian cancer cells. Our findings suggest that ovarian cancer cells exposure to LPS plays an important role in cancer metastasis through the modulation of miR-503-5p and the regulation of CD97/CD55.

Discussion

The extracellular N-terminus containing EGF-like structural domains of CD97 binds to its ligand CD55 (Decay-accelerating-factor, DAF), which affects cancer invasion and metastasis [28], [29]. Since up-regulation of CD97 on activated lymphocyte contributes the interaction with components of the extracellular matrix [1], [2], CD97 overexpression is closely related with promoting the effect of tumor growth and migration through the activation of proteolytic activity of tumor cells [30]. Following chemotherapy with paclitaxel, recurrent ovarian high-grade serous cancer cells also express higher levels of several proteins, including CD97 [7]. However, the activation of intracellular downstream signaling by the CD97-CD55 interaction is yet unclear and no studies have reported which mechanism regulates the expression and role of CD97 in drug-resistant ovarian cancer cells. The expression of CD97 was only detected in metastatic ovarian cancer cells (SKOV3 and OV90) without LPS stimulation. LPS-exposed or paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells induce CD97 expression through NF-κB-mediated miR-503-5p down-regulation. CD97 binding to its ligand CD55 triggers the JAK2/STAT3 pathway to enhance metastasis of ovarian cancer cells. These results suggest that the level of CD97 and miR-503-5p not only is a new diagnostic or therapeutic target for ovarian cancer but also might be a critical marker for determining the possibility of ovarian cancer metastasis (Figure 6G).

MicroRNAs, small noncoding RNAs, show various expression patterns and influence a diverse set of genes post-transcriptionally expressed in numerous developmental and physiological processes [31], [32]. Each type of cell utilizes and uniquely changes the mRNA sequences in a cell-type-dependent manner. For mRNAs that should not be expressed in a particular cell type, miRNAs reduce protein production to negligible levels [32]. Increased miR-503, which is located at human chromosome Xq26.3, delays the cell cycle in the G1 phase through targeting CCNE1 encoding the G1/S-specific cyclin-E1 and cdc25A encoding the cell division cycle 25 homolog [33]. MiR-503 down-regulates the expression of Fibroblast growth factor-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor A, resulting in the inhibition of tumor angiogenesis and growth [34]. The expression of miR-503 inhibits the migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro [35]. In addition, the down-regulation of miR-503 is associated with poor clinical outcome and inversely associated with the level of carcinoembryonic antigen in gastric cancer [36]. Whereas, miR-503 overexpression is identified in ALDH1-positive chemoresistant ovarian cancer cells [19], ALDH1(+) ovarian cancer cells comprise 0.4–4.0% of primary cancer cells [19]. Furthermore, the role of miR-503 and its targeting genes in paclitaxel-resistant cancer cell is unknown. Additionally modulating the mechanism of miR-503 expression to affect the metastasis of ovarian cancer should be investigated. The level of miR-503-5p in OV90 is lower compared with CaOV3 cells, even in the absence of LPS stimulation. LPS-stimulated OV90 cells showed more colony-forming activity than LPS-exposed CaOV3 cells. Chemoresistant ovarian cancer cells reduced the expression miR-503-5p to promote metastasis through the up-regulation of CD97 expression, resulting in the activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway. Furthermore, transfection of the miR-503-5p mimic prevented the up-regulation of CD97 in this study. These results suggest that the level of CD97 expression is positively correlated with ovarian cancer metastasis, and the reverse relationship between CD97 and miR-503-5p might be applied to determine the effect of chemotherapy and prognosis through the detection of the levels of CD97 and miR-503-5p, respectively.

TLR4 stimulation by LPS activates JAK2/STAT3 signaling for producing inflammatory cytokines in microglia cells [37]. The constitutively activated STAT3 plays a critical role in uncontrolled cellular proliferation, promotion of angiogenesis, and resistance to apoptosis in various cancers, including ovarian cancer [38], [39]. The treatment of ovarian cancer cells with paclitaxel also leads to the activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway [40]. JAK2 inhibitor therapy efficiently prevents the proliferation and migratory activity of CD24-positive ovarian cancer stem cells under in vitro and in vivo conditions [41]. High CD97 expression also leads to elevated proliferation and the invasion of tumor cells through the up-regulation of phosphorylated mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) [16]. However, the relevance between CD97 and JAK2/STAT3 expression in LPS-stimulated or paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells has not been investigated. Although CD97 expressed on metastatic ovarian cancer cells promoted the invasion of cancer cells after treatment with rhCD55 through the slightly activation of JAK2/STAT3, binding rhCD55 to elevated CD97 in LPS-stimulated or chemoresistant ovarian cancer cells markedly triggered the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway to induce metastasis. These results suggest that the enhanced CD97-mediated JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway also plays a more important role in paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells and CD97 and the underlying pathways could be promising targets to prevent and treat metastatic ovarian cancer.

Conclusions

In this study, we firstly discovered the novel mechanism of miR-503-5p to induce metastasis in chemoresistant ovarian cancer cells. Our study also provides experimental information on the relationship between CD97 expression and miR-503-5p as well as the downstream JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway in paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer cells. These results also suggest that comparing the expression of CD97 in tumors with circulating miR-503-5p levels could reflect the tumor condition and possibility of metastasis and serve as a potential indicator of prognosis in ovarian cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Science and ICT, MIST) (NRF-2018R1C1B6002381) and Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2018R1D1A1B07040382).

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neo.2018.12.005.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Eichler W, Hamann J, Aust G. Expression characteristics of the human CD97 antigen. Tissue Antigens. 1997;50:429–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1997.tb02897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yona S, Lin HH, Siu WO, Gordon S, Stacey M. Adhesion-GPCRs: emerging roles for novel receptors. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:491–500. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aust G, Steinert M, Schütz A, Boltze C, Wahlbuhl M, Hamann J, Wobus M. CD97, but not its closely related EGF-TM7 family member EMR2, is expressed on gastric, pancreatic, and esophageal carcinomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;118:699–707. doi: 10.1309/A6AB-VF3F-7M88-C0EJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Safaee M, Clark AJ, Ivan ME, Oh MC, Bloch O, Sun MZ, Oh T, Parsa AT. CD97 is a multifunctional leukocyte receptor with distinct roles in human cancers. Int J Oncol. 2013;43:1343–1350. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han SL, Xu C, Wu XL, Li JL, Liu Z, Zeng QQ. The impact of expressions of CD97 and its ligand CD55 at the invasion front on prognosis of rectal adenocarcinoma. Int J Color Dis. 2010;25:695–702. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-0926-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang PY, Liao YP, Wang HC, Chen YC, Huang RL, Wang YC, Yuan CC, Lai HC. An epigenetic signature of adhesion molecules predicts poor prognosis of ovarian cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8:53432–53449. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jinawath N, Vasoontara C, Jinawath A, Fang X, Zhao K, Yap KL, Guo T, Lee CS, Wang W, Balgley BM. Oncoproteomic analysis reveals co-upregulation of RELA and STAT5 in carboplatin resistant ovarian carcinoma. PLoS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X, Crowe PJ, Goldstein D, Yang JL. STAT3 inhibition, a novel approach to enhancing targeted therapy in human cancers. Int J Oncol. 2012;41:1181–1191. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abubaker K, Luwor RB, Zhu H, McNally O, Quinn MA, Burns CJ, Thompson EW, Findlay JK, Ahmed N. Inhibition of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway in ovarian cancer results in the loss of cancer stem cell-like characteristics and a reduced tumor burden. BMC Cancer. 2014;6(14):317. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen DG, Mercado-Uribe I, Yang G, Bast RC, Jr., Amin HM, Lai R, Liu J. The role of constitutively active signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 in ovarian tumorigenesis and prognosis. Cancer. 2006;107:2730–2740. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colomiere M, Ward AC, Riley C, Trenerry MK, Cameron-Smith D, Findlay J, Ackland L, Ahmed N. Cross talk of signals between EGFR and IL-6R through JAK2/STAT3 mediate epithelial-mesenchymal transition in ovarian carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:134–144. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ. Oncomirs - microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:259–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:857–866. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Croce CM. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:704–714. doi: 10.1038/nrg2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu YY, Sweredoski MJ, Huss D, Lansford R, Hess S, Tirrell DA. Prometastatic GPCR CD97 is a direct target of tumor suppressor microRNA-126. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:334–338. doi: 10.1021/cb400704n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li C, Liu DR, Li GG, Wang HH, Li XW, Zhang W, Wu YL, Chen L. CD97 promotes gastric cancer cell proliferation and invasion through exosome-mediated MAPK signaling pathway. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:6215–6228. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i20.6215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Fang Y, Liu Y, Yang X. MicroRNAs in ovarian function and disorders. J Ovarian Res. 2015 Aug;8(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s13048-015-0162-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lei L, Jin S, Gonzalez G, Behringer RR, Woodruff TK. The regulatory role of Dicer in folliculogenesis in mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010 Feb 5;315(1–2):63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park YT, Jeong JY, Lee MJ, Kim KI, Kim TH, Kwon YD, Lee C, Kim OJ, An HJ. MicroRNAs overexpressed in ovarian ALDH1-positive cells are associated with chemoresistance. J Ovarian Res. 2013;6:18. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-6-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hennessy BT, Coleman RL, Markman M. Ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2009;374:1371–1382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61338-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly MG, Alvero AB, Chen R, Silasi DA, Abrahams VM, Chan S, Visintin I, Rutherford T, Mor G. TLR-4 signaling promotes tumor growth and paclitaxel chemoresistance in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3859–3868. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szajnik M, Szczepanski MJ, Czystowska M, Elishaev E, Mandapathil M, Nowak-Markwitz E, Spaczynski M, Whiteside TL. TLR4 signaling induced by lipopolysaccharide or paclitaxel regulates tumor survival and chemoresistance in ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2009;28:4353–4363. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park GB, Chung YH, Kim D. Induction of galectin-1 by TLR-dependent PI3K activation enhances epithelial-mesenchymal transition of metastatic ovarian cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2017;37:3137–3145. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu H, Lee H, Herrmann A, Buettner R, Jove R. Revisiting STAT3 signalling in cancer: new and unexpected biological functions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014 Nov;14(11):736–746. doi: 10.1038/nrc3818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beaufort CM, Helmijr JC, Piskorz AM, Hoogstraat M, Ruigrok-Ritstier K, Besselink N, Murtaza M, van IJcken WF, Heine AA, Smid M. Ovarian cancer cell line panel (OCCP): clinical importance of in vitro morphological subtypes. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou R, Gong AY, Chen D, Miller RE, Eischeid AN, Chen XM. Histone deacetylases and NF-kB signaling coordinate expression of CX3CL1 in epithelial cells in response to microbial challenge by suppressing miR-424 and miR-503. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar S, Mahdi H, Bryant C, Shah JP, Garg G, Munkarah A. Clinical trials and progress with paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. Int J Women's Health. 2010;2:411–427. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S7012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meng ZW, Liu MC, Hong HJ, Du Q, Chen YL. Expression and prognostic value of soluble CD97 and its ligand CD55 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2017;39 doi: 10.1177/1010428317694319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wobus M, Vogel B, Schmücking E, Hamann J, Aust G. N-glycosylation of CD97 within the EGF domains is crucial for epitope accessibility in normal and malignant cells as well as CD55 ligand binding. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:815–822. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galle J, Sittig D, Hanisch I, Wobus M, Wandel E, Loeffler M, Aust G. Individual cell-based models of tumor-environment interactions: Multiple effects of CD97 on tumor invasion. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1802–1811. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plaisance-Bonstaff K, Renne R. Viral miRNAs. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;721:43–66. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-037-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caporali A, Meloni M, Völlenkle C, Bonci D, Sala-Newby GB, Addis R, Spinetti G, Losa S, Masson R, Baker AH. Deregulation of microRNA-503 contributes to diabetes mellitus-induced impairment of endothelial function and reparative angiogenesis after limb ischemia. Circulation. 2011;123:282–291. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.952325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou B, Ma R, Si W, Li S, Xu Y, Tu X, Wang Q. MicroRNA-503 targets FGF2 and VEGFA and inhibits tumor angiogenesis and growth. Cancer Lett. 2013;333:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou J, Wang W. Analysis of microRNA expression profiling identifies microRNA-503 regulates metastatic function in hepatocellular cancer cell. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:278–283. doi: 10.1002/jso.21941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu D, Cao G, Huang Z, Jin K, Hu H, Yu J, Zeng Y. Decreased miR-503 expression in gastric cancer is inversely correlated with serum carcinoembryonic antigen and acts as a potential prognostic and diagnostic biomarker. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;10:129–135. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S114303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang X, Dong H, Zhang S, Lu S, Sun J, Qian Y. Enhancement of LPS-induced microglial inflammation response via TLR4 under high glucose conditions. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;35:1571–1581. doi: 10.1159/000373972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sansone P, Bromberg J. Targeting the interleukin-6/Jak/stat pathway in human malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1005–1014. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.8907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abubaker K, Luwor RB, Escalona R, McNally O, Quinn MA, Thompson EW, Findlay JK, Ahmed N. Targeted Disruption of the JAK2/STAT3 Pathway in Combination with Systemic Administration of Paclitaxel Inhibits the Priming of Ovarian Cancer Stem Cells Leading to a Reduced Tumor Burden. Front Oncol. 2014;4:75. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmed N, Abubaker K, Findlay J, Quinn M. Epithelial mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell-like phenotypes facilitate chemoresistance in recurrent ovarian cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2010;10:268–278. doi: 10.2174/156800910791190175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burgos-Ojeda D, Wu R, McLean K, Chen YC, Talpaz M, Yoon E, Cho KR, Buckanovich RJ. CD24+ Ovarian Cancer Cells Are Enriched for Cancer-Initiating Cells and Dependent on JAK2 Signaling for Growth and Metastasis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:1717–1727. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material