Abstract

Numerous studies have focused on the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in estrogen receptor positive (ER) breast cancer (BC), as a linear signal transduction pathway and reported its association with worse clinical outcomes. We developed gene signatures that reflect the level of expression of phosphorylated-Serine473-AKT (pAKT) and phosphorylated-Serine2448-mTOR (p-mTOR) separately, capturing their corresponding level of pathway activation. Our analysis revealed that the pAKT pathway activation was associated with luminal A BC while the p-mTOR pathway activation was more associated with luminal B BC (Kruskal–Wallis test p < 10−10). pAKT pathway activation was significantly associated with better outcomes (multivariable HR, 0.79; 95%CI, 0.74–0.85; p = 2.5 × 10−10) and PIK3CA mutations (p = 0.0001) whereas p-mTOR pathway activation showed worse outcomes (multivariable HR,1.1; 95%CI, 1.1–1.2; p = 9.9 × 10−4) and associated with p53 mutations (p = 0.04). in conclusion, our data show that pAKT and p-mTOR pathway activation have differing impact on prognosis and suggest that they are not linearly connected in luminal breast cancers.

Molecular signaling: Two components of same pathway have divergent effects

One of the key signaling pathways involved in regulating cancer cell growth and survival is not linearly connected in luminal breast cancers, as researchers had long assumed. A team led by Amir Sonnenblick from Tel Aviv University, Israel, and Christos Sotiriou from Institut Jules Bordet, Belgium, studied tumors with elevated expression of two different proteins in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. They showed that tumors with activated AKT had distinct gene expression profiles from tumors with activated mTOR. What’s more, patients with AKT activation had better outcomes on average and were more likely to carry mutations in the oncogene PIK3CA, whereas patients with mTOR activation tended to relapse sooner and were more likely to carry mutations in the tumor suppressor p53. The findings suggest that doctors should look closely at PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling activation when personalizing treatment decisions.

Introduction

The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mTOR-signaling pathway mediates key cellular functions, including growth, proliferation, and survival and is frequently involved in carcinogenesis, tumor progression, and metastases.1 Numerous studies have focused on the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in estrogen receptor positive (ER-positive) breast cancer (BC) and have shown that PIK3CA mutations are frequent, that the PI3K/AKT/mTOR-signaling pathway is often dysregulated and that both correlate with worse clinical outcomes.2–4 As a consequence, a large number of drugs targeting the various components of this pathway have been developed.5 Everolimus (an mTOR inhibitor) is currently the only approved drug targeting mTOR based on the results of the BOLERO-2 trial.6

While AKT is activated by phospholipid binding and activation loop phosphorylation at Threonine308 by PDK1 and by phosphorylation within the carboxy terminus at Serine473, mTOR is phosphorylated at Serine2448 via the PI3K-signaling pathway.7 AKT activates the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) which in addition to mTOR contains mLST8, PRAS40, and RAPTOR.8 This activation involves phosphorylation of tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2), which blocks the ability of TSC2 to act as a GTPase-activating protein, thereby allowing accumulation of Rheb-GTP and mTORC1 activation. AKT can also activate mTORC1 by PRAS40 phosphorylation, thereby relieving the PRAS40-mediated inhibition of mTORC1.9

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is usually considered as a linear signal transduction pathway in BC, however in the ER-positive disease, we have previously shown that PIK3CA mutations were associated with relatively low mTORC1 functional output and with good outcomes in patients who received adjuvant tamoxifen monotherapy.4 Therefore, to gain better insight into the relative contribution of each of the signaling pathways which lie downstream to PI3K (namely AKT and mTOR) to BC outcomes, we have developed a novel in silico approach which assessed the activation of each of these signaling pathways separately, by integrating reverse phase protein array (RPPA) and matched gene expression.

Results

pAKT pathway activated and p-mTOR pathway activated ER-positive early BCs are associated with distinct and exclusive gene expression profiles

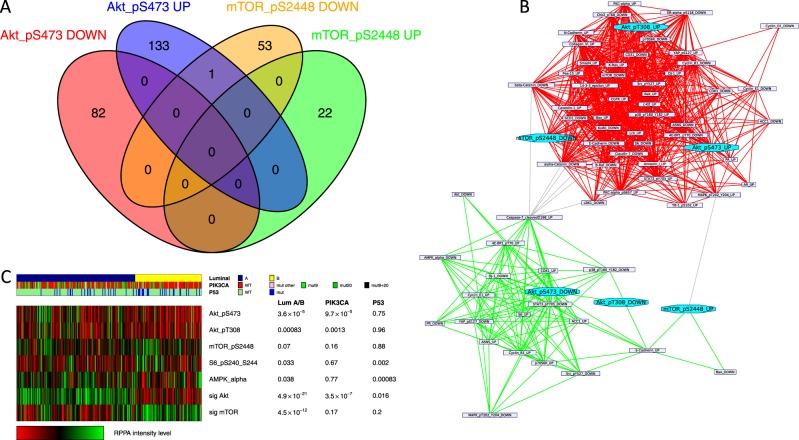

We first derived two distinct signatures whose expression levels could predict AKT and mTOR pathway activation through pAKT and p-mTOR RPPA levels by computing the differentially expressed genes between tumor samples with high and low RPPA levels of pAKT (respectively, activated and inactivated AKT pathway) and p-mTOR proteins (respectively, activated and inactivated mTOR pathway), using ER-positive tumors from the TCGA repository. It is important to note that the two signatures did not share any common genes (Fig. 1a). We next sought to assess their biological and clinical relevance in BC. Firstly, we compared both signatures to the reference classes of the Gene Ontology and the mSigDB signatures repositories using the Broad Institute site.10 This showed that the pAKT signature was significantly enriched in genes up-regulated in less aggressive invasive BC tumors (e.g. grade 1 vs. grade 311; fdr = 2 × 10−27). In contrast, the p-mTOR signature was enriched in genes expressed in mammary stem cells and more aggressive luminal B cancers11,12 (fdr = 2 × 10−7, fdr = 3 × 10−5, respectively). A network clustering analysis using the pAKT and p-mTOR signatures, as well as other RPPA-derived signatures that demonstrated a significant intersection with them, identified two main sub-networks according mainly to their proliferation status, namely pAKT-high/p-mTOR-low and pAKT-low/p-mTOR high characterized with low and high proliferation levels, respectively (Fig. 1b). These observations were confirmed when analyzing the TCGA RPPA dataset (Figs. 1c and S1). AKT pathway was more often activated (elevated pAKT expression) in luminal A cancers whereas mTOR pathway was more often activated (elevated p-mTOR and pS6, an mTOR downstream target), in luminal B subtypes (Figs. 1c and S2). Next, we sought to determine how the pAKT and p-mTOR signatures correlate with other signatures and RPPA markers of the pathway. As shown in Fig. S3, the pAKT signature negatively correlates with downstream effectors of the pathway while the p-mTOR signature positively correlates with them.

Fig. 1.

pAKT and p-mTOR signatures derived from the TCGA. a Venn diagram shows no intersection between the pAKT and p-mTOR gene signatures. b Network representation of the gene signatures. Each node represents the genes up-regulated or down-regulated in the signature. Edges show signatures sharing a significant number of genes. Network clustering shows the tendency of these signatures to cluster together according to their proliferation status. c Integrated analysis of the PIK3CA/pAKT/m-TOR pathway in the TCGA. Luminal breast cancer subtypes differ by pAKT and p-mTOR activity. The panel includes a protein-based (RPPA) proteomic status. Tumors were ordered first by mRNA subtype (luminal A versus B). P values were calculated using the Mann–Whitney test

Altogether, these results demonstrate that the pAKT and p-mTOR pathways, assessed through these RPPA-based gene expression signatures, have exclusive distribution according to luminal molecular subtypes and are not necessarily linearly connected.

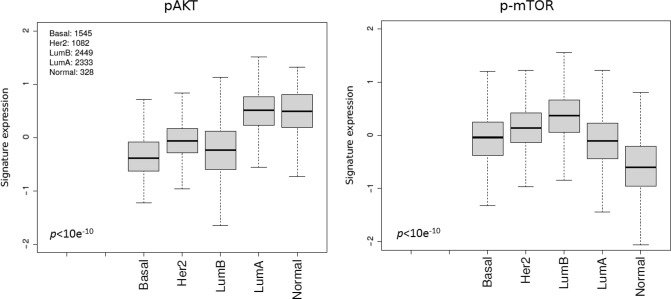

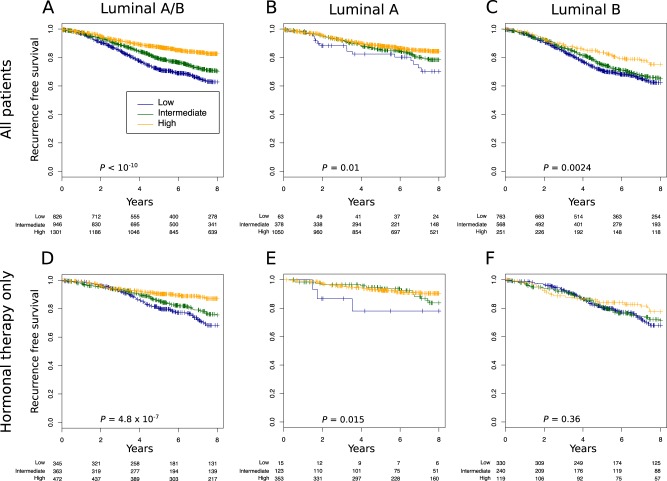

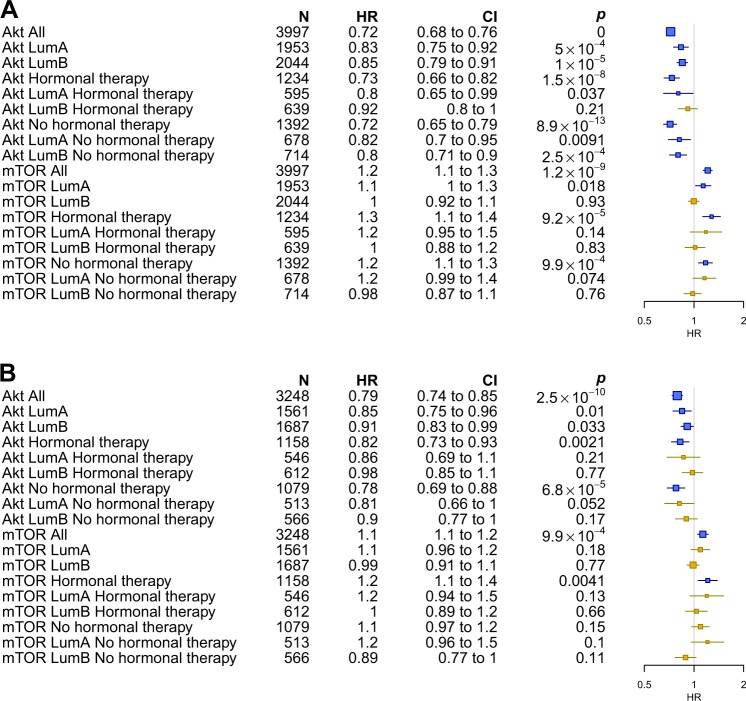

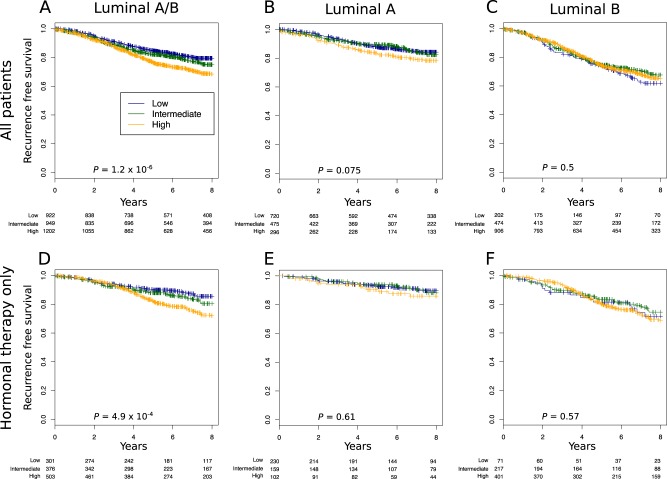

Association of the pAKT and p-mTOR pathway activation with clinical outcome in patients with ER-positive early BC

To ascertain the impact of each pathway on outcomes in ER-positive BC, we applied the pAKT and p-mTOR signatures on a dataset composed of 38 publicly available microarray datasets. We first assessed whether pAKT or p-mTOR pathway activation were associated with any particular luminal subtype. As expected, in the pooled set analysis pAKT pathway activation was significantly associated will luminal A cancers (p < 10−10) whereas p-mTOR pathway activation was associated with luminal B cancers (p < 10−10) (Fig. 2). We next assessed whether pAKT and p-mTOR pathway activation were correlated with outcomes (RFS) in ER-positive patients with relapse data available. As shown in Figs. 3 and 5, pAKT pathway activation was significantly associated with better outcomes in all luminal patients (multivariable HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.74–0.85; p = 2.5 × 10−10). Similar results were obtained with a dataset consisting of patients treated with endocrine therapy only (multivariable HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.73–0.93; p = 0.002). Indeed, patients with pAKT pathway activation had better outcomes irrespective of their specific subtype (luminal A multivariable HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.75–0.96; p = 0.01; luminal B HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.83–0.99; p = 0.033). In contrast, patients with p-mTOR pathway activation had significantly worse outcomes in all luminal patients (multivariable HR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.1–1.2; p = 9.9 × 10−4) and this remained true when tested in the dataset consisting of patients treated with endocrine therapy only (multivariable HR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1–1.4; p = 0.004) (Figs. 4 and 5).

Fig. 2.

pAKT (right) and p-mTOR (left) gene signatures expression in publicly available microarray datasets according to the PAM50 breast cancer subtype. Kruskal–Wallis p-value is shown

Fig. 3.

High pAKT gene signature expression is associated with good prognosis in the luminal subtype. a–f We assessed the prognostic value of tertiles of pAKT gene signature expression in: a all luminal patients treated or not treated (n = 3073), b luminal A (n = 1491), c Luminal B (n = 1582), d all luminal treated with only hormonal therapy (n = 1180), e luminal A treated with only hormonal therapy (n = 491), and f luminal B treated with only hormonal therapy (n = 689). Significance (p-value) of differences in survival between patient groups defined by tertiles of pAKT signature expression is estimated by log-rank test. The analysis presented includes patients with lymph node-negative and lymph node-positive cancers

Fig. 5.

Forest plots showing the hazard ratios of the recurrence free survival of pAKT and p-mTOR gene signatures treated as a continuous variable using Cox univariate a and multivariable analysis b, in the pooled analysis. For multivariate analysis, we considered the following variables: age, tumor size, grade, and nodal status. Signatures with nominal significant effect (p < 0.05) are shown in blue

Fig. 4.

High p-mTOR gene signature expression is associated with bad prognosis in the luminal subtype. a–f We assessed the prognostic value of tertiles of p-mTOR gene signature expression in: a all luminal patients treated or not treated (n = 3073), b luminal A (n = 1491), c Luminal B (n = 1582), d all luminal treated with only hormonal therapy (n = 1180), e luminal A treated with only hormonal therapy (n = 491), and f luminal B treated with only hormonal therapy (n = 689). Significance (p values) of differences in survival between patient groups defined by tertiles of p-mTOR signature expression is estimated by log-rank test. The analysis presented includes patients with lymph node-negative and lymph node-positive cancers

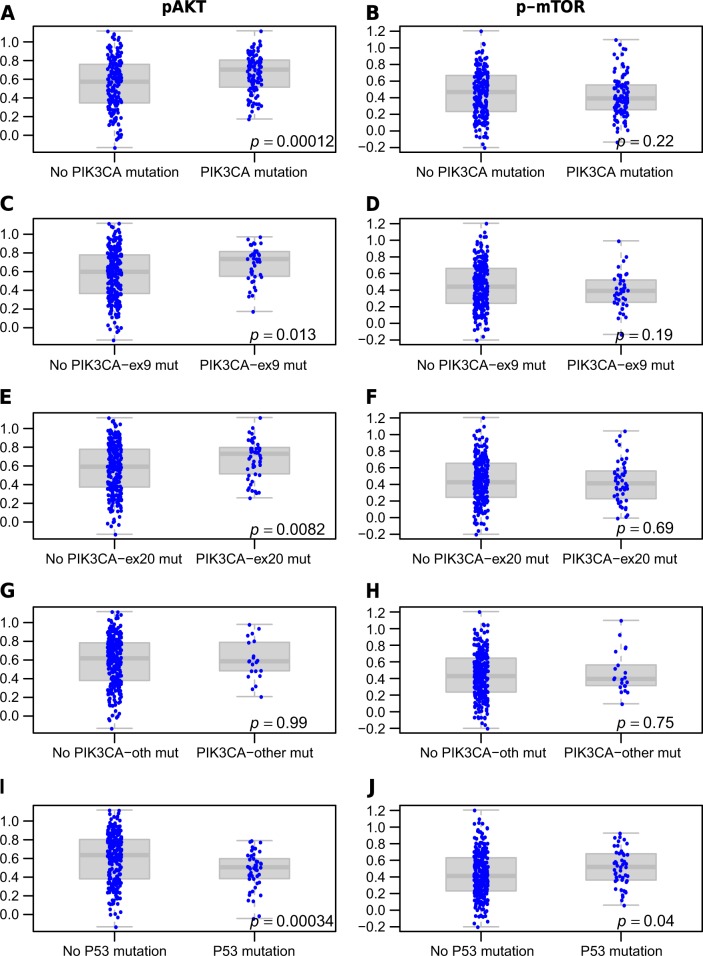

Next, we assessed the association between the PIK3CA and P53 mutation status and pAKT and p-mTOR pathway activation in an independent set, namely the TCGA BC patients with RNA-sequence gene expression data that were not used to design the signatures. While the pAKT signature was associated with PIK3CA mutations (p = 0.0001), the p-mTOR signature was not (p = 0.22) (Fig. 6a, b). The opposite was true for P53 mutations, which were positively correlated with p-mTOR pathway activation (p = 0.04), and negatively correlated with pAKT (p = 0.0003) (Fig. 6i, j). Analysis of the PIK3CA mutations by exon led to similar results (Fig. 6), although mutations outside of exons 9 and 20 seemed less associated with pAKT pathway activation.

Fig. 6.

Expression of pAKT (a, c, e, g, i) and p-mTOR (b–d, f, h, j) gene signatures levels in PIK3CA (all, exon9, exon20 or others) and P53 mutated and wild type samples in an independent RNA sequencing set (n = 309)

Finally, in an effort to identify whether these signatures could predicts response to mTOR inhibitors, we evaluated another data set of neo-adjuvant patients treated with Everolimus.13 Analysis of the correlations between the effectiveness of this treatment and the developed signatures suggests as expected that the pAKT signature is associated with less response to Everolimus (r = 0.45; p = 0.031, Fig. S4).

Overall, our data suggests that pAKT and p-mTOR pathway activation as assessed through the respective signatures, despite being major components of the same overarching pathway (PI3K), have distinctly different impacts on disease biology and consequently on outcomes in early disease.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to better understand the distinct contribution to disease biology and clinical outcomes of signaling through the AKT and mTOR downstream pathways, which typically occur as part of PI3K pathway activation in luminal BCs. We found that pAKT and p-mTOR were differentially expressed according to luminal subtypes, implying different degrees of pathway activation, and that, more importantly, the pathways were not linearly connected. Additionally, we found that pAKT pathway activation was positively associated with PIK3CA mutations whereas the opposite was observed with p-mTOR pathway activation. In contrast, pAKT pathway activation was associated with good clinical outcome despite its known tumorigenic effects. Between 30% and 40% of BCs, especially ER-positive tumors, have mutations in PIK3CA.14 The vast majority of the PIK3CA mutations are missense mutations which are positioned in the helical domain (exon 9, mostly: E545K and E542K) and the kinase domain (exon 20, mostly H1047R) in hotspot clusters.15 These mutations have direct effect on AKT phosphorylation. The effect of PIK3CA mutations/pAKT on prognosis is mixed in early BC.16 We found that exons 9 and 20 mutations in PIK3CA were more associated with pAKT than mutations in other exons.

We previously reported that PIK3CA mutations were associated with improved outcome and low levels of signaling through the mTOR pathway in BC.4,17 Several possible hypotheses were raised regarding the reasons for this. Some data available on PP2A and PML, both known to have an inhibitory effect on both AKT and mTOR,18,19 have suggested that they may be upregulated in PIK3CA-activated tumors. Negative feedback regulation in PI3K-mediated cells through the insulin receptor substrate20 and relatively weak pathway activation in PIK3CA-mutated cancers have also been suggested as possible explanations for low levels of signaling through mTOR in ER-positive BC.

According to our findings only pAKT pathway activation was found to be significantly different between the luminal subtypes (A and B) and PIK3CA wildtype versus mutant, whereas p-mTOR pathway activation was not significant for both. The inconclusive and relative activation of p-mTOR by the mutant PIK3CA may be also attributed to the different roles and activators of mTOR and the fact that mTOR is at the cross section of multiple signaling pathways. Several studies have clearly demonstrated that mTOR is a direct substrate for the AKT kinase and identified Serine2448 as the AKT target site in mTOR.21 However, additional studies have demonstrated that rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTOR function, blocks serum-stimulated Serine2448 phosphorylation of mTOR in an AKT-independent manner and identified S6 kinase as a major effector of mTOR phosphorylation at Serine2448.22 Indeed, our analysis of the TCGA data shows that the S6 kinase (downstream of mTOR) is associated with luminal B and P53 mutations suggesting that while mTOR itself is at the cross section of conflicting pathways its downstream targets are not PIK3CA dependent. In addition, there are alternative kinases that can activate the mTOR pathway independently of AKT, such as RSK which leads to phosphorylation of TSC resulting in increased mTOR signaling and the PDK1–SGK1 axis that can sustain mTOR activity upon AKT suppression.23–25

The primary TCGA report, which investigated all BC subtypes,26 confirmed a high frequency of PIK3CA mutations in luminal BC. Multiple platforms, which examined the relationship between PIK3CA mutation and protein expression, have demonstrated that pAKT and pS6 were not elevated in PIK3CA-mutated luminal cancers; instead, they were highly expressed in basal-like and HER2 subtypes. Our dataset, which is restricted to luminal cancers, demonstrated that pAKT pathway activation is associated with luminal A/PIK3CA mutations and good prognosis, while p-mTOR/pS6 is not, suggesting that the presence of HER2 and basal subtype in the primary analysis of the TCGA masked these observations.

In conclusion our data suggest that the AKT and mTOR pathways are not linearly connected in luminal BCs. pAKT pathway activation is associated with PIK3CA mutations, luminal A and good prognosis, while p-mTOR pathway activation is associated with luminal B, P53 mutations, and bad prognosis. These results may have important clinical implications considering that in low p-mTOR BCs, treatment with mTOR inhibitors, such as everolimus, which is highly toxic, will possibly be of lower value since the pathway is not activated. Additionally, pAKT pathway activation, as measured through our gene signature, can add to presently used outcome prediction tools in both luminal A and luminal B tumors.

Methods

Computation of RPPAs-based signatures

We downloaded clinic-pathological, normalized gene expression and RPPA data from the publicly available TCGA repository using its online bioinformatics tools26 (Fig. S1 flow chart). ER-positive early BCs were analyzed based on the RPPA proteomic levels. 265 samples with available gene expression and RPPA data were considered as luminal (166 Luminal A and 99 Luminal B according to PAM50 computed on the cBioPortal website27). To identify the genes that were differentially expressed between the low and high expression groups, and to find the genes that would optimize the predictive power of our signatures, we used a machine learning approach as previously described.28 After this process, we were left with 69 signatures (Supplementary Data) presenting a relevant AUC for proteomic status prediction. Among others, p-mTOR achieved an AUC of 0.71 (p ~ 10−6) and pAKT an AUC of 0.77 (p ~ 10−11) in both luminal A and B cancers.

Code availability

The expression levels of the signatures in the gene expression datasets were computed as previously described.28 In brief, we evaluated using a nested 10-fold cross validation the maximal Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate and the minimal gene fold change that would optimize the ability of the differentially expressed genes to predict the high/low status of the RPPA in luminal A and B patients together and separately. While the parameters were selected in a 10-fold cross validation, the procedure itself was assessed using a nested cross validation. All analyses were performed using the genefu package of the R (v3.2)/bioconductor (v1.18) statistical suite.

Network analysis and clustering

Network analysis and clustering was performed as previously described.28 The MCL graph clustering algorithm29 was applied. Visualization of the network has been rendered using the yED software.

Gene-expression data and statistical analyses

We analyzed 38 gene expression datasets totaling more than 7000 tumors (detailed in Table 1). To ensure comparability of expression values across multiple data sets, a 0.95 quantile normalization was performed. Differences in expression of pAKT and p-mTOR signatures according to subtype were examined using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Survival outcome data are presented as recurrence free survival (RFS). Survival plots according to the pAKT and p-mTOR signatures tertiles were drawn using the Kaplan–Meier method. Association of the signatures (i.e. pathway activation) with good or bad outcomes were computed using uni-variate or multi-variate Cox regression analyses and data were presented as forest plots. For multivariate analysis, we considered the following variables: age, tumor size, grade, and nodal status. To assess the correlation between the PIK3CA mutation status and AKT and p-mTOR gene pathway activation, as represented by the gene signature scores, we analyzed the TCGA cohort of RNA sequenced data that was not used for the computation of the signatures (309 samples), and for which both mutational and gene expression data were available. Each sample was considered as mutated or not (so a sample with four mutations was considered just like a sample with one mutation). All mutations were taken into account. PIK3CA mutations were also analyzed by specific exons (exons 9, 20, and all others grouped together).

Table 1.

The sources and locations for the 38 gene expression datasets analyzed

| Dataset | No. of patients | Permanent identifier | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| NKI | 337 | 10.1038/415530a | 31, 32 |

| UCSF | 162 | GSE123833 | 33, 34 |

| STNO2 | 122 | GSE4335 | 35 |

| NCI | 99 | 10.1073/pnas.1732912100 | 36 |

| UNC4 | 337 | GSE18229 | 37 |

| CAL | 118 | E-TABM-158 | 38 |

| MDA4 | 129 (65)‡ | GSE123832 | 39, 40 |

| KOO | 88 | GSE123831 | 41 |

| HLP | 53 | E-TABM-543 | 42 |

| EXPO | 353 | GSE2109 | 43 |

| VDX | 344 | GSE2034/GSE5327 | 44, 45 |

| MSK | 99 | GSE2603 | 46 |

| UPP | 251 (190)‡ | GSE3494 | 47 |

| STK | 159 | GSE1456 | 48 |

| UNT | 137 (92)‡ | GSE2990 | 36, 49 |

| DUKE | 171 | GSE3143 | 50 |

| TRANSBIG | 198 | GSE7390 | 51 |

| DUKE2 | 160 | GSE6961 | 52 |

| MAINZ | 200 | GSE11121 | 53 |

| LUND2 | 105 | GSE5325 | 54 |

| LUND | 143 | GSE5325 | 55 |

| FNCLCC | 150 | GSE7017 | 56 |

| EMC2 | 204 | GSE12276 | 57 |

| MUG | 152 | GSE10510 | 58 |

| NCCS | 183 | GSE5364 | 59 |

| MCCC | 75 | GSE19177 | 60 |

| EORTC10994 | 49 | GSE1561 | 61 |

| DFHCC | 115 | GSE19615 | 62 |

| DFHCC2 | 84 (75)‡ | GSE18864 | 63 |

| DFHCC3 | 40 (26)‡ | GSE3744 | 64 |

| DFHCC4 | 129 | GSE5460 | 65 |

| MAQC2 | 230 | GSE20194 | 66 |

| TAM | 345 (242)‡ | GSE6532/GSE9195 | 67 |

| MDA5 | 298 | GSE17705 | 68 |

| VDX3 | 136 | GSE12093 | 69 |

| PNC | 248 | GSE20713 | 70 |

| TCGA | 517 | https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/docs/publications/brca_2012/ | 26 |

| METABRIC | 1643 | EGAS00000000083 | 14 |

‡Duplicated patients were removed from few datasets for the estimation of concordance and prognostic value

Reporting summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Carolyn Straehle for her editorial assistance. A.S. is supported by a Clinical Research Career Development Award from the Israel Cancer Research Fund grants (16-116-CRCDA) and from the Israeli Cancer Research Association (2017-0140). A.S. was an ESMO translational research fellow. C.S. is supported by the Breast Research Cancer Foundation (BCRF).

Author contributions

A.S. conceived of the study and participated in its design and coordination, analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. S.B. analyzed and interpreted the data, performed the statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript. N.P. coordinated the analysis and drafted the manuscript. D.V. carried out the statistical analysis analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. C.S. participated in the study design and coordination, analyzed, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The sources and locations for the 38 gene expression datasets analyzed during the current study are available in Table 1 and the figshare repository 10.6084/m9.figshare.7461776.30

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Amir Sonnenblick, Email: amirsonn@gmail.com.

Christos Sotiriou, Email: christos.sotiriou@bordet.be.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies the paper on the npj Breast Cancer website (10.1038/s41523-019-0102-1).

References

- 1.Hennessy BT, Smith DL, Ram PT, Lu Y, Mills GB. Exploiting the PI3K/AKT pathway for cancer drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:988–1004. doi: 10.1038/nrd1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koboldt DC, et al. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell IG. Mutation of the PIK3CA gene in ovarian and breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7678–7681. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loi S, et al. PIK3CA mutations associated with gene signature of low mTORC1 signaling and better outcomes in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:10208–10213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907011107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dienstmann R, Rodon J, Serra V, Tabernero J. Picking the point of inhibition: a comparative review of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway inhibitors. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014;13:1021–1031. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baselga J, et al. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor–positive advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:520–529. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navé BT, Ouwens M, Withers DJ, Alessi DR, Shepherd PR. Mammalian target of rapamycin is a direct target for protein kinase B: identification of a convergence point for opposing effects of insulin and amino-acid deficiency on protein translation. Biochem. J. 1999;344:427–431. doi: 10.1042/bj3440427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. Defining the role of mTOR in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 2007;129:1261–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sotiriou C, et al. Gene expression profiling in breast cancer: understanding the molecular basis of histologic grade to improve prognosis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2006;98:262–272. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim E, et al. Transcriptome analyses of mouse and human mammary cell subpopulations reveal multiple conserved genes and pathways. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R21. doi: 10.1186/bcr2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabine VS, et al. Gene expression profiling of response to mTOR inhibitor everolimus in pre-operatively treated post-menopausal women with oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010;122:419–428. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0928-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curtis C, et al. The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature. 2012;486:346–352. doi: 10.1038/nature10983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samuels Y, et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304:554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang SX, Polley E, Lipkowitz S. New insights on PI3K/AKT pathway alterations and clinical outcomes in breast cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2016;45:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalinsky K, et al. PIK3CA mutation associates with improved outcome in breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:5049–5059. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trotman LC, et al. Identification of a tumour suppressor network opposing nuclear Akt function. Nature. 2006;441:523–527. doi: 10.1038/nature04809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernardi R, et al. PML inhibits HIF-1alpha translation and neoangiogenesis through repression of mTOR. Nature. 2006;442:779–785. doi: 10.1038/nature05029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paz K, et al. A molecular basis for insulin resistance. Elevated serine/threonine phosphorylation of IRS-1 and IRS-2 inhibits their binding to the juxtamembrane region of the insulin receptor and impairs their ability to undergo insulin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:29911–29918. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sekulić A, et al. A direct linkage between the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-AKT signaling pathway and the mammalian target of rapamycin in mitogen-stimulated and transformed cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiang GG, Abraham RT. Phosphorylation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) at Ser-2448 is mediated by p70S6 kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:25485–25490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501707200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roux PP, Ballif BA, Anjum R, Gygi SP, Blenis J. Tumor-promoting phorbol esters and activated Ras inactivate the tuberous sclerosis tumor suppressor complex via p90 ribosomal S6 kinase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:13489–13494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405659101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castel P, et al. PDK1-SGK1 signaling sustains AKT-independent mTORC1 activation and confers resistance to PI3Kα inhibition. Cancer Cell. 2016;30:229–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma L, Chen Z, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Pandolfi PP. Phosphorylation and functional inactivation of TSC2 by Erk implications for tuberous sclerosis and cancer pathogenesis. Cell. 2005;121:179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao J, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci. Signal. 2013;6:pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sonnenblick A, et al. p-STAT3 in luminal breast cancer: integrated RNA-protein pooled analysis and results from the BIG 2-98 phase III trial. Int. J. Oncol. 2018;52:424–432. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2017.4212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Enright AJ, Van Dongen S, Ouzounis CA. An efficient algorithm for large-scale detection of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1575–1584. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.7.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sylvain, S. B., Sonnenblick, A., & Venet, D. Gene expression data sources for in silico approach to assessing activation of AKT/mTOR signalling pathway signalling pathways ER-positive early BC. figshare. Fileset 10.6084/m9.figshare.7461776 (2018).

- 31.van de Vijver MJ, et al. A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;347:1999–2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van’t Veer LJ, et al. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002;415:530–536. doi: 10.1038/415530a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korkola JE, et al. Identification of a robust gene signature that predicts breast cancer outcome in independent data sets. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korkola JE, et al. Differentiation of lobular versus ductal breast carcinomas by expression microarray analysis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7167–7175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sorlie T, et al. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:8418–8423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932692100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sotiriou C, et al. Breast cancer classification and prognosis based on gene expression profiles from a population-based study. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:10393–10398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1732912100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prat A, et al. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of the claudin-low intrinsic subtype of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R68. doi: 10.1186/bcr2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chin K, et al. Genomic and transcriptional aberrations linked to breast cancer pathophysiologies. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:529–541. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hess KR, et al. Pharmacogenomic predictor of sensitivity to preoperative chemotherapy with paclitaxel and fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide in breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24:4236–4244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.6861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liedtke C, et al. Response to neoadjuvant therapy and long-term survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:1275–1281. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang E, et al. Gene expression predictors of breast cancer outcomes. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2003;361:1590–1596. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Natrajan R, et al. An integrative genomic and transcriptomic analysis reveals molecular pathways and networks regulated by copy number aberrations in basal-like, HER2 and luminal cancers. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010;121:575–589. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0501-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bittner M. (2005) Expression Project for Oncology (expO). www.intgen.org/expo. Accessed 3 Nov 2010.

- 44.Wang Y, et al. Gene-expression profiles to predict distant metastasis of lymph-node-negative primary breast cancer. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2005;365:671–679. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70933-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Minn AJ, et al. Lung metastasis genes couple breast tumor size and metastatic spread. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:6740–6745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701138104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Minn AJ, et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to lung. Nature. 2005;436:518–524. doi: 10.1038/nature03799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller LD, et al. An expression signature for p53 status in human breast cancer predicts mutation status, transcriptional effects, and patient survival. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:13550–13555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506230102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pawitan Y, et al. Gene expression profiling spares early breast cancer patients from adjuvant therapy: derived and validated in two population-based cohorts. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:R953–R964. doi: 10.1186/bcr1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Loi S, et al. Definition of clinically distinct molecular subtypes in estrogen receptor-positive breast carcinomas through genomic grade. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:1239–1246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bild AH, et al. Oncogenic pathway signatures in human cancers as a guide to targeted therapies. Nature. 2006;439:353–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Desmedt C, et al. Strong time dependence of the 76-gene prognostic signature for node-negative breast cancer patients in the TRANSBIG multicenter independent validation series. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13:3207–3214. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bonnefoi H, et al. Validation of gene signatures that predict the response of breast cancer to neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a substudy of the EORTC 10994/BIG 00-01 clinical trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70345-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidt M, et al. The humoral immune system has a key prognostic impact in node-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5405–5413. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saal LH, et al. Poor prognosis in carcinoma is associated with a gene expression signature of aberrant PTEN tumor suppressor pathway activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:7564–7569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702507104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Niméus-Malmström E, et al. Gene expression profiling in primary breast cancer distinguishes patients developing local recurrence after breast-conservation surgery, with or without postoperative radiotherapy. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R34. doi: 10.1186/bcr1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Campone M, et al. Prediction of metastatic relapse in node-positive breast cancer: establishment of a clinicogenomic model after FEC100 adjuvant regimen. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2008;109:491–501. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9673-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bos PD, et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to the brain. Nature. 2009;459:1005–1009. doi: 10.1038/nature08021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Calabrò A, et al. Effects of infiltrating lymphocytes and estrogen receptor on gene expression and prognosis in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009;116:69–77. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu K, et al. A precisely regulated gene expression cassette potently modulates metastasis and survival in multiple solid cancers. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Waddell N, et al. Subtypes of familial breast tumours revealed by expression and copy number profiling. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010;123:661–677. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0653-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Farmer P, et al. Identification of molecular apocrine breast tumours by microarray analysis. Oncogene. 2005;24:4660–4671. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li Q, et al. Minimising immunohistochemical false negative ER classification using a complementary 23 gene expression signature of ER status. PloS ONE. 2010;5:e15031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silver DP, et al. Efficacy of neoadjuvant Cisplatin in triple-negative breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:1145–1153. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Richardson AL, et al. X chromosomal abnormalities in basal-like human breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lu X, et al. Predicting features of breast cancer with gene expression patterns. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2008;108:191–201. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9596-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Popovici V, et al. Effect of training-sample size and classification difficulty on the accuracy of genomic predictors. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R5. doi: 10.1186/bcr2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Loi S, et al. Predicting prognosis using molecular profiling in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer treated with tamoxifen. BMC Genom. 2008;9:239. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Symmans WF, et al. Genomic index of sensitivity to endocrine therapy for breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:4111–4119. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang Y, et al. The 76-gene signature defines high-risk patients that benefit from adjuvant tamoxifen therapy. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009;116:303–309. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0183-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dedeurwaerder S, et al. DNA methylation profiling reveals a predominant immune component in breast cancers. EMBO Mol. Med. 2011;3:726–741. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The sources and locations for the 38 gene expression datasets analyzed during the current study are available in Table 1 and the figshare repository 10.6084/m9.figshare.7461776.30