Abstract

Aging leads to gray and white matter decline but their causation remains unclear. We explored two classes of models of age and dementia risk related brain changes. The first class of models emphasises the importance of gray matter: age and risk-related processes cause neurodegeneration and this causes damage in associated white matter tracts. The second class of models reverses the direction of causation: aging and risk factors cause white matter damage and this leads to gray matter damage. We compared these models with linear mediation analysis and quantitative MRI indices (from diffusion, quantitative magnetization transfer and relaxometry imaging) of tissue properties in two limbic structures implicated in age-related memory decline: the hippocampus and the fornix in 166 asymptomatic individuals (aged 38–71 years). Aging was associated with apparent glia but not neurite density damage in the fornix and the hippocampus. Mediation analysis supported white matter damage causing gray matter decline; controlling for fornix glia damage, the correlations between age and hippocampal damage disappear, but not vice versa. Fornix and hippocampal differences were both associated with reductions in episodic memory performance. These results suggest that fornix white matter glia damage may cause hippocampal gray matter damage during age-dependent limbic decline.

Subject terms: Cognitive ageing, Cognitive neuroscience, Glial biology

Introduction

The world’s population is growing older and increasing numbers of people over the age of 65 will develop cognitive impairment due to late onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD)1. The pathological processes leading to LOAD accumulate over many years2 but prior to disease onset it remains challenging to reliably distinguish them from normal aging processes. Thus, recent recommendations of the Lancet commission3 highlight the importance of midlife prevention studies to gain a better understanding of the impact of aging and dementia risk in asymptomatic individuals.

Aging causes damage to both gray and white matter in the human brain. White matter consists of myelinated and unmyelinated axons and neuroglia cells, i.e., oligodendrocytes, astrocytes and microglia, while gray matter comprises neuronal cell bodies, synapses, dendrites and glia. Neuroglia cells are essential for normal synaptic and neuronal activity as they maintain the brain’s homeostasis, form myelin, protect neurons, and are dynamically remodelled to support brain plasticity4–7.

There are two classes of causal models of aging and LOAD risk: the first class of neurodegenerative models proposes that gray matter neuronal loss precedes white matter glia and axon damage. According to an influential neurodegenerative model, the amyloid cascade hypothesis8,9, aging and LOAD risk factors lead to metabolic changes in the amyloid precursor protein that result in the aggregation of amyloid-β plaques, which trigger pathological events including the formation of neurofibrillary tangles, loss of synapses, neurons and their axons. Immunity-related microglia changes occur in response to increased plaque and tangle burden10–12. The second class of model reverses the direction of causality, stating that the normal aging process in interaction with genetic and lifestyle risk factors of LOAD will cause neuroglia damage, resulting in impaired myelination, reduced microglia-mediated clearance and neuroinflammation, which in turn instigates pathological processes that lead to abnormal metabolism in key proteins and neuronal death13–16. The two classes of models predict opposite patterns of age and risk-related changes in white and gray matter. While in neurodegenerative models, white matter damage follows gray matter neuronal loss, the neuroglia model predicts that white matter neuroglia damage causes gray matter tissue loss.

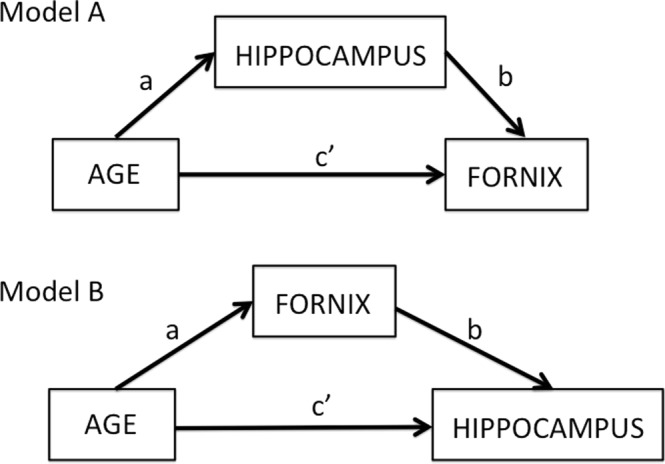

Currently, the nature of age-related white and gray matter tissue changes and the causal direction between them remain unknown. This study therefore investigated the impact of age and risk on quantitative MRI indices of apparent neurite and glia properties and discriminated between the two types of models using linear mediation analysis17–19. More specifically, we investigated the effects of aging and risk factors on tissue properties of two important gray and white matter structures involved in age-related memory decline, the hippocampus20 and the fornix21, in 166 asymptomatic individuals (39–71 years old) (Table 1). We then tested two mediation models displayed in Fig. 1: Model A assessed whether the inclusion of hippocampal variables mediated the direct effect of age on the fornix, whilst Model B tested whether fornix variables mediated age effects on the hippocampus. If full mediation of age effects was observed in Model A but not in Model B, then this would suggest that hippocampal gray matter differences were causing white matter fornix differences, consistent with neurodegenerative models of aging. However, if full mediation occurred in Model B but not Model A, then this would suggest that age-related fornix differences were causing hippocampal gray matter differences, consistent with neuroglia models of aging.

Table 1.

Summary of demographic, genetic and lifestyle risk information of participants.

| Mean (SD) | Participants (n = 166) |

|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 55.8 (8.2) |

| Females | 56% |

| Years of education | 16.5 (3.3) |

| NART | 116.7 (6.7) |

| MMSE | 29.1 (1.0) |

| Rey figure immediate recall | 25.7 (5.5) |

| Rey figure delayed recall | 24.2 (5.8) |

| RAVLT immediate recall | 8.8 (1.9) |

| RAVLT delayed recall | 12.1 (2.3) |

| Positive Family History dementia | 35.1% |

| APOE Genotype % | |

| ε2/ε2 | 0.6% |

| ε2/ε3 | 10.7% |

| ε2/ε4 | 3.6% |

| ε3/ε3 | 48.8% |

| ε3/ε4 | 32.1% |

| ε4/ε4 | 4.2% |

| Abdominal obesity (Waist Hip Ratio) | 61.3% |

| Systolic Hypertension | 28% |

| Smokers | 5.4% |

| Diabetes | 1.8% |

| Statins | 7.2% |

| Alcohol units per week | 7.4 (9.3) |

| Physical activities* | 10.3 (12.1) |

| (Median hours per week) | |

*Based on all non-sedentary activities including walking, house work, gardening.

APOE = Apolipoprotein-E, MMSE = Mini Mental State Exam, NART = National Adult Reading Test, RAVLT = Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

Figure 1.

Overview of two mediation models: Model (A) tests for the indirect effects of hippocampal mediator variables on the direct effect of age on the fornix (path c’). The indirect effect is the product a*b of the correlations between age and hippocampus (path a) and the partial correlation between hippocampus and fornix accounting for age (path b). Model (B) tests the indirect effects of the fornix mediator variables on the direct effect of age on the hippocampus.

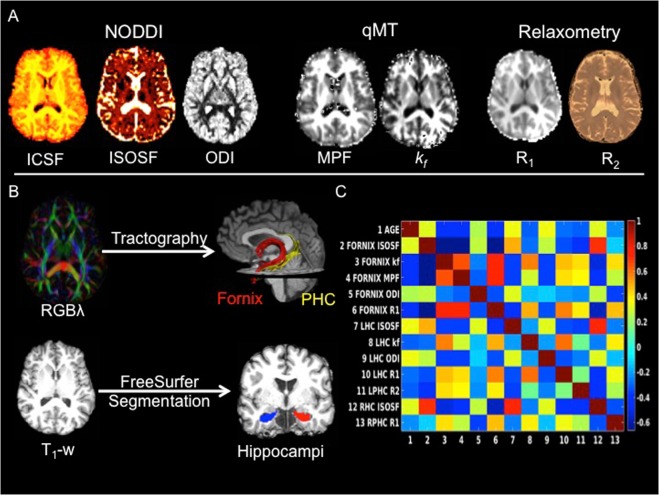

We employed multi-modal quantitative MRI measurements to assess gray and white matter tissue properties in the hippocampus, the fornix, and the parahippocampal cingulum (PHC), as a temporal lobe comparison pathway. Separate estimates of neurite and glia-related microstructural tissue properties were obtained from diffusion neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI)22, quantitative magnetization transfer (qMT)23–30 and relaxometry imaging (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) MRI modalities and maps acquired from dual-shell high angular resolution diffusion imaging (HARDI), quantitative magnetisation transfer (qMT) imaging and from T1 and T2 relaxometry. HARDI data were modelled with neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI), yielding maps of intracellular signal fraction (ICSF), isotropic signal fraction (ISOSF) and orientation dispersion index (ODI). The qMT maps were the macromolecular proton fraction (MPF) and the forward exchange rate kf. Maps from relaxometry were the longitudinal relaxation rate R1 (1/T1) and R2 (1/T2). (B) Mean indices of the metrics were extracted from left and right hippocampi, fornix and parahippocampal cinguli (PHC) tracts. Hippocampi were segmented from T1- weighted images with FreeSurfer version 5.3 and fornix and PHC were reconstructed with damped-Richardson Lucy spherical deconvolution (dRL) based deterministic tractography on colour coded principal direction maps (RGBλ). (C) Cross-correlation matrix between white and gray matter microstructural indices that correlated with age.

NODDI yielded the intracellular signal fraction (ICSF), an index of apparent neurite density, the neurite orientation dispersion index (ODI), and the isotropic signal fraction (ISOSF), an estimate of free water contribution to the diffusion signal. Diffusion MRI metrics are well-known measures of white matter microstructure31–33 and NODDI ICSF and ODI have been proposed to be particularly sensitive to axon density and dispersion34,35. In addition, we used qMT, a technique that allows the quantification of differences in brain macromolecular density, and provides indices with improved white matter glia specificity compared to diffusion MRI27–30. In white matter, magnetization transfer is dominated by myelin36,37, and is sensitive to microglia-mediated inflammation28,38,39. We measured the macromolecular proton fraction (MPF) as an index of white matter neuroglia that will largely reflect its myelin content and the forward exchange rate kf, an index of the rate of the magnetization transfer process27, that has been proposed to reflect metabolic efficiency of mitochondrial function40 (Fig. 2A). Finally, the longitudinal relaxation rates R1 (1/T1) and R2 (1/T2) were obtained as additional estimates of the relative contribution of water, myelin and iron content of gray and white matter tissue41–44 (Fig. 2A).

Mean values of all MRI indices were extracted from the fornix and the PHC tracts, that were reconstructed with deterministic tractography, and from FreeSurfer segmentations of the whole hippocampi45,46 (Fig. 2B). The hippocampal regions included areas of the presubiculum, subiculum, cornu ammonis subfields 1–4, dentate gyrus, hippocampal tail and fissure but excluded cortical regions such as the entorhinal cortex47,48.

To study the relationships between age-related differences in MRI metrics and genetic and lifestyle risk factors of LOAD as well as differences in episodic memory performance, we also acquired the following information (Table 1): Genetic risk was assessed by carriage of the Apolipoprotein-E (APOE) ε4 allele49,50 and separately by a positive family history of a first grade relative with dementia of the Alzheimer’s, Lewy body or vascular type. We predicted more pronounced white matter glia reductions in APOE ε4 compared to ε2 and/or ε3 carriers, as cholesterol transport for myelin repair in the brain has been proposed to be less efficient in ε4 carriers50–53. In addition, we assessed lifestyle-related risk factors associated with the metabolic syndrome, notably central obesity, hypertension, alcohol consumption and sedentary lifestyle54,55 (Table 1). We were particularly interested in the effects of central adiposity, as obesity is globally on the rise, and is associated with chronic inflammation, insulin resistance and vascular problems54,55 as well as with accelerated aging in brain regions that include limbic white matter56,57. Finally, episodic memory performance was assessed with standard neuropsychological tests of verbal and non-verbal recall58,59 (Table 1).

Neuroglia models predict that aging and risk factors will primarily reduce glia sensitive metrics of MPF, kf, R1 and R2 whilst apparent neurite density (ICSF) and dispersion (ODI) should be less affected. In contrast, neurodegenerative models predict impairments in ICSF and ODI with relatively preserved glia-metrics. Age and risk-related increases in ISOSF, reflective of increased free water content in brain tissue, may be expected by both models. Importantly though, neurodegenerative models predict that hippocampal differences will mediate age-related white matter microstructural differences in the fornix (Model A), whilst neuroglia models predict that age-related differences in glia sensitive white matter metrics of the fornix will mediate age-related hippocampal differences (Model B).

Results

Omnibus multivariate regression analysis

Multivariate regression analysis with all hippocampal, fornix and PHC MRI outcome metrics as dependent variables, tested simultaneously for omnibus effects of the following independent variables:

age,

genetic risk: family history of dementia (yes/no), APOE genotype [ε2 (ε2/ε2, ε2/ε3), ε3(ε3/ε3), ε4(ε3/ε4, ε4/ε4)],

lifestyle-related risk: central obesity assessed with the waist hip ratio (WHR), systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP), weekly alcohol consumption and physical activity,

and potentially confounding variables of sex, years of education, and head size assessed with intracranial volume (ICV).

Given the low numbers of diabetics, smokers, and individuals on statins amongst our sample (Table 1), these variables were not included in the analyses. This analysis revealed significant omnibus effects of age [F(35, 96) = 3.0, p = 0.000015; ηp2 = 0.52] and ICV [F(35, 96) = 2.3, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.45].

Post-hoc multivariate covariance analyses, controlling for ICV, then tested for the effects of age on each of the hippocampal, fornix and PHC MRI indices separately. Table 2 summarises the age effects on white and gray matter microstructure. Age affected all fornix indices, except ICSF [F(2, 152) = 1.1, p = 0.35]. There were also significant age effects for left PHC R2, right PHC R1 and for left and right hippocampal ISOSF, left hippocampal R1, kf and ODI (Table 2) (Fig. 3). No age effects were observed for hippocampal ICSF [left: F(2, 152) = 0.2, p = 0.84; right: F(2, 152) = 0.7, p = 0.48] (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Summary of the effects of age on gray and white matter microstructural indices.

| MRI index | F(2,152)-value* | p-value** | Effect size ηp2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fornix | MPF | 11.9 | 0.00002 | 0.14 |

| k f | 10.0 | 0.00009 | 0.12 | |

| R1 | 12.4 | 0.00001 | 0.14 | |

| ISOSF | 8.9 | 0.0002 | 0.11 | |

| ODI | 5.0 | 0.008 | 0.06 | |

| Left PHC | R2 | 7.5 | 0.001 | 0.09 |

| Right PHC | R1 | 4.7 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Left hippocampus | k f | 6.7 | 0.002 | 0.08 |

| R1 | 5.0 | 0.008 | 0.06 | |

| ISOSF | 12.2 | 0.00001 | 0.14 | |

| ODI | 9.8 | 0.0001 | 0.12 | |

| Right hippocampus | ISOSF | 7.5 | 0.001 | 0.09 |

*Controlled for intracranial volume, **5% FDR corrected. ISOSF = isotropic signal fraction, MPF = macromolecular proton fraction, ODI = orientation dispersion index, PHC = parahippocampal cingulum.

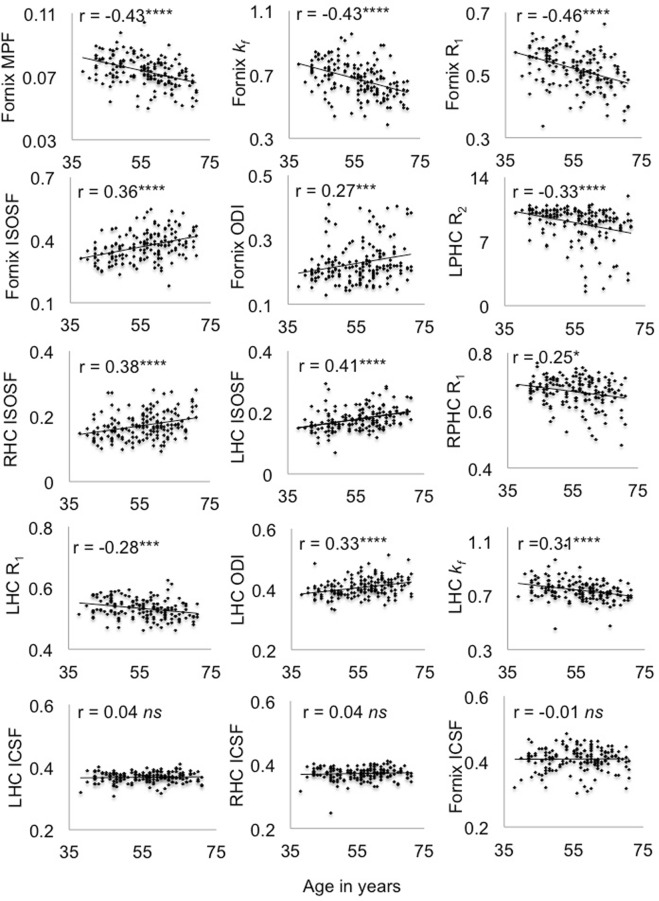

Figure 3.

Plots the correlations and Pearson coefficients (controlled for intracranial volume) between age and white and gray matter microstructural indices. Abbr.: ICSF = intracellular signal fraction, ISOSF = isotropic signal fraction, kf = forward exchange rate, LHC = left hippocampus, LPHC = left parahippocampal cingulum, MPF = macromolecular proton fraction, ODI = orientation dispersion index, R = longitudinal relaxation rate, RHC = right hippocampus, RPHC = right parahippocampal cingulum ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, 5% False Discovery Rate corrected.

Age correlated negatively with fornix MPF, R1, kf, left PHC R2, right PHC R1, left hippocampal kf and R1, and positively with fornix and hippocampal ISOSF and ODI (Fig. 3). No age correlations were present with ICSF in the fornix or the hippocampi and these ‘null’ correlations differed significantly from the smallest age correlations in the fornix (zODI = 2.5, p = 0.01), left hippocampus (zR1 = 2.78, p = 0.005) and right hippocampus (zISOSF = 3.18, p = 0.002) (Fig. 3).

Figure 2C displays the Pearson correlation coefficient matrix between the white and hippocampal gray matter metrics. The same metrics measured in white and gray matter correlated positively with each other with the exception of fornix and left hippocampal ODI (r = −0.12, p = 0.13). MPF, kf, R1 and R2 correlated positively with each other and so did ISOSF and ODI, whilst MPF, kf, R1 and R2 were inversely correlated with ISOSF and ODI.

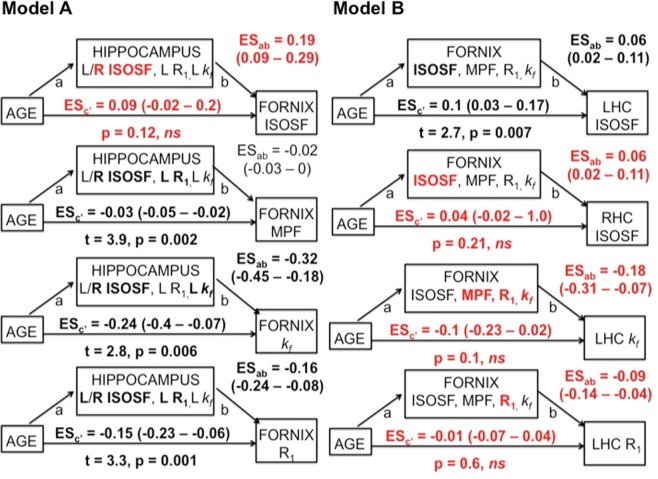

Mediation analyses between hippocampal and fornix metrics

To avoid any bias in the comparison of Model A and Model B, the number of mediator variables, that showed significant age effects and correlated with each other in white and gray matter, was kept constant. Mediator variables in Model A were the left and right hippocampal ISOSF, left hippocampal R1 and left hippocampal kf, and in Model B the four white matter metrics that showed the largest age effects, i.e., fornix ISOSF, MPF, kf, and R1. There were no significant differences between the age effect sizes in the fornix and the hippocampus (rmax:age-fornix R1 versus rmin:age-left hippocampal R1: z = 1.8, p = 0.07).

In Model B, fornix mediator variables fully mediated the age effects on right hippocampal ISOSF, left hippocampal kf and left hippocampal R1 (Fig. 4, highlighted in red) but hippocampal mediators in model A, although showing significant indirect effects on the direct effects of age on fornix R1 and kf, did not remove the age effects on fornix MPF, R1 and kf. A bi-directional relationship was observed between right hippocampal ISOSF and fornix ISOSF, with both variables fully mediating each other’s age effect. Finally, fornix ISOSF contributed but did not fully mediate the correlation between age and left hippocampal ISOSF, and left hippocampal ISOSF only marginally contributed to the age correlation in fornix R1. To summarise, full mediation of age effects on glia metrics was observed in Model B but not in Model A (Fig. 1), such that age-related glia differences in the fornix mediated age differences in the hippocampus but not vice versa.

Figure 4.

Summarises the results of the mediation analyses for Models A and B. 95% confidence intervals of the effect sizes (ES × 10−1) were based on bootstrapping with 5000 replacements. Fornix mediators in Model B had significant indirect effects and fully mediated the direct age effects on right hippocampal (RHC) isotropic signal fraction (ISOSF), left hippocampal (LHC) R1 and kf (highlighted in red). In contrast, hippocampal mediators, although showing significant indirect effects (highlighted in bold), did not fully mediate the direct age effects on fornix MPF, R1 and kf. Right (R) hippocampal ISOSF fully mediated fornix ISOSF and vice versa but fornix mediators did not remove the age effect on left hippocampal ISOSF. Mediator variables that contributed significantly to the regression analyses after 5% FDR correction are highlighted in bold.

Effects of genetic and lifestyle risk factors on age-mediator variables

We further explored whether genetic and lifestyle risk factors had an effect on mediator variables that fully accounted for age effects with hierarchical regression analysis. First age, ICV, sex and years of education were entered into the regression model followed by the stepwise inclusion of all genetic and lifestyle risk variables. Table 3 summarises the results of these regression analyses. Besides age, sex was a significant predictor for differences in fornix and hippocampal ISOSF. WHR contributed significantly to fornix MPF and R1 and alcohol consumption to fornix R1. There were trends (significant at the uncorrected level) for a contribution of family history of dementia and diastolic BP to differences in right hippocampal ISOSF.

Table 3.

Summary of the results of the hierarchical regression models testing for the effects of genetic and lifestyle risk variables on fornix and hippocampus mediator variables.

| Outcome variables | Adjusted R2 | Predictors in final regression model |

|---|---|---|

| Fornix MPF | 0.24 (p < 0.001) | Age (p < 0.001) |

| WHR (p = 0.02) | ||

| Fornix R1 | 0.28 (p < 0.001) | Age (p < 0.001) |

| ICV (p = 0.009) | ||

| Alcohol (p = 0.01) | ||

| WHR (p = 0.018) | ||

| Fornix kf | 0.23 (p < 0.001) | Age (p < 0.001) |

| WHR (p = 0.04) | ||

| Fornix ISOSF | 0.32 (p < 0.001) | Age (p < 0.001) |

| ICV (p = 0.03) | ||

| Sex (p = 0.001) | ||

| Right hippocampal ISOSF | 0.36 (p < 0.001) | Age (p < 0.001) |

| ICV (p = 0.008) | ||

| Sex (p = 0.002) | ||

| Diastolic BP (p = 0.035) | ||

| FH (p = 0.04) |

5% FDR corrected p-values are highlighted in bolds.

Post-hoc comparisons revealed that centrally obese individuals compared with individuals with a normal WHR showed lower MPF [t(160) = 2.8, p = 0.005] and R1 [t(160) = 3.35, p = 0.0009] in the fornix. Men compared with women showed higher ISOSF in the right hippocampus [t(162) = 6.5, p < 0.00001] and in the fornix [t(164) = 6.7, p < 0.00001]. Participants with a positive family history exhibited higher ISOSF in the right hippocampus [t(160) = 2.55, p = 0.012] and there was a positive correlation between diastolic BP and ISOSF in the right hippocampus [r(164) = 0.18, p = 0.02]. However, there was no difference in fornix R1 between individuals that consumed alcohol units above the weekly-recommended limit compared with those within the UK recommended guidelines (p = 0.9).

Correlations between age-mediator variables and episodic memory performance

Inter-individual differences in delayed verbal recall were negatively correlated with differences in fornix ISOSF [r(164) = −0.22, p = 0.005) and differences in right hippocampal ISOSF [r(164) = − 0.2, p = 0.006].

CSF partial volume effects

To test whether age effects on fornix and hippocampal qMT metrics were driven by free water partial volume effects, ISOSF metrics were used as mediator variables. Fornix ISOSF contributed significantly to all regression models (p < 0.0001) but did not remove the direct age effect on fornix MPF (t = −3.88, p = 0.0002), R1 (t = −3.69, p = 0.0003), and kf (t = −3.88, p = 0.0002). Right but not left hippocampal ISOSF contributed significantly to left hippocampal R1 (p = 0.003) and kf (p = 0.03) and removed the direct age effect on left hippocampal R1 (p = 0.05) but not on left hippocampal kf (p = 0.0013).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to discriminate between two classes of causal models of aging with mediation analysis. The neurodegenerative model predicted that age-related hippocampal differences would account for age effects on fornix metrics whilst the neuroglia model predicted that age differences in fornix glia would cause age-differences in the hippocampus. Our results are consistent with the neuroglia model as we found that fornix glia sensitive metrics of MPF, R1 and kf fully mediated the effects of age on hippocampal tissue properties but not vice versa, i.e., hippocampal mediator variables, although demonstrating significant indirect effects, did not remove the age effects on fornix MPF, R1 and kf (Fig. 4). This pattern of results is consistent with a growing body of evidence pointing towards an important role of neuroglia changes in aging and neurodegeneration11,13–15,60–62. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show that fornix white matter glia damage may cause hippocampal gray matter damage during age-dependent limbic decline in the human brain.

Both in the hippocampus and the fornix, we observed age-related increases in ISOSF and ODI and reductions in glia-sensitive metrics from qMT and relaxometry imaging, whilst age had no effects on ICSF. Overall this pattern of results suggests age-dependent i) increases in the free water content of tissue, ii) reductions in glia-sensitive indices, and iii) increases in apparent neurite dispersion in the absence of differences in apparent neurite density.

In white matter, MPF, kf, R1 and R2 are known to be sensitive to myelin, as well as to neuroinflammation and to a lesser degree to iron changes27–30,38,44,63,64. While some effects were observed on R1 and R2 in the PHC, the largest age-dependent reductions in MPF, kf, and R1 were present in the fornix tract. Reductions in these indices in the absence of any effects on ICSF suggest that aging affects glia-sensitive properties of white matter, notably myelin, but not apparent axon density, i.e. not the number and the size of axons. These results provide novel in vivo neuroimaging evidence consistent with neuropathological findings of a reduction of up to 45% of the length of myelinated fibers, rather than a loss of axons per se across the lifespan65–69. Similarly, age-related reductions in fornix myelination and glia changes in the absence of any changes of the fornix cross-sectional area were also observed in non-human primates70. Myelin damage is closely linked to neuroinflammation and qMT metrics are sensitive to both processes71. Thus it may also be possible that the observed differences in MPF and kf reflect age-dependent dystrophic and reactive microglia changes39,72.

Similarly, in hippocampal gray matter we observed age-related reductions of R1 and kf in the absence of differences in ICSF. Age reductions in hippocampal R1 were accounted for by increases in hippocampal ISOSF and may, therefore, primarily reflect increases in the water content of hippocampal tissue. Increases in hippocampal ISOSF are consistent with neuropathological findings of a loss of hippocampal pyramidal cells and dentate gyrus granule cells associated with normal aging73. However, the absence of an effect on hippocampal ICSF suggests that apparent dendritic density was unaffected and increased ISOSF may also be compatible with glia-related changes in gray matter. Furthermore, the observed reductions in hippocampal kf, a marker of the rate of the magnetization transfer between macromolecular and free water pool, may reflect age-dependent metabolic differences. Giulietti et al.40 found kf reductions in the hippocampus, temporal lobe, posterior cingulate and parietal cortex in LOAD, and proposed that these changes may reflect reductions in metabolic mitochondrial activity74. Age-related reductions of hippocampal metabolic activity have also been observed in animal studies75,76 and age-related damage to mitochondria of microglia has been linked to sustained microglia neuroinflammation7.

Currently, a causal link between age-related neuroglia changes and the development of LOAD pathology in the human brain remains speculative. However, white matter disease, characterised by a loss of myelin, oligodendrocytes, axons and reactive astrocyte gliosis77–79 is a known feature of LOAD. Accumulating evidence also suggests that neuroinflammation and a reduction of glia mediated clearance mechanisms contribute to LOAD11,12,80. For instance, reactive microglia were found in the hippocampus of LOAD brains81 and microglia derived ASC protein specks have been shown to cross-seed amyloid-β plaques in transgenic double-mutant APPSwePSEN1dE9 mice82. It is therefore possible that age-related neuroglia changes involving myelin and inflammation pathways may not only occur in response to neuropathology but may even trigger protein abnormalities and synaptic and neuronal loss. Thus, an intriguing interpretation of our results may be that aging is associated with glia changes including loss of myelin in the fornix, which in turn may cause tissue damage in the hippocampus, that might make this region more vulnerable to the development of LOAD pathology81,83. Clearly, future longitudinal prospective studies assessing the predictive value of MRI indices of white matter glia for amyloid and tau burden are needed to test this hypothesis.

We also observed a bi-directional mediation effect between right hippocampal ISOSF and fornix ISOSF, such that both variables fully mediated the age effect on each other. This result is unsurprising and reflects that unspecific tissue loss in the hippocampus is associated with tissue loss in the fornix and the other way around. In contrast, fornix and left hippocampal ODI metrics were not correlated with each other. This finding suggests that ODI indices may capture different microstructural properties and may not be directly comparable in gray and in white matter, potentially due to differences in tissue complexity and organisation.

The question arises how genetic and lifestyle risk factors of LOAD impact on medial temporal tissue properties. Consistent with our hypothesis, centrally obese individuals exhibited reductions in fornix MPF and R1. Obesity-related reductions in MRI metrics of proton density, R1, and R2*, have previously been observed in white matter pathways connecting frontal and limbic regions in young adults84. Obesity has also been associated with accelerated aging of cerebral white matter56 and we previously reported Body Mass Index related increases in mean and axial diffusivities in the fornix57. Although the mechanisms underpinning these changes remain unclear, it may be possible that the observed MRI differences may reflect changes in neuroglia that may be linked with obesity-related systemic inflammation. Consistent with this interpretation, differences in white matter fractional anisotropy in obesity were reported to be associated with inflammation and to a lesser degree with glucose regulation, whilst lower blood pressure and dyslipidemia appeared to have positive effects on white matter microstructure85.

Unexpectedly and in contrast to previous reports52,53,86 we did not observe a main effect of the APOE genotype on hippocampal gray matter or fornix/PHC white matter tissue properties. There is substantial evidence that APOE ε4 carrier status in older individuals (>65 years of age) is related to accelerated atrophy in the hippocampus, increased beta-amyloid burden and to an earlier onset of dementia87,88. However, the effect size of APOE-ε4 genotype on age-related hippocampal atrophy over the adult life course is small (e.g. β = −0.05, p = 0.04 in n = 3749 between 43–69 years of age)89,50,90–93 and the biological mechanisms underpinning these relationships remain poorly understood. The APOE gene is involved in many complex functions, including lipid and amyloid-β metabolism, neuroinflammation and vascular regulation94. It is likely that APOE genotype, rather than exhibiting straightforward main effects, interacts with age and with multiple genetic and lifestyle-related factors. As the effects of APOE genotype were not the main focus of this study, testing for potential interaction effects between APOE genotype and other demographic and risk factors was beyond the scope of this paper.

In contrast to APOE, we observed some contribution of family history of dementia and diastolic blood pressure to hippocampal ISOSF, but these effects did not survive multiple comparison correction. We also found that men compared with women showed larger ISOSF in the right hippocampus and in the fornix. These results are compatible with previous findings, indicating that both family history95 and being male96–99 are associated with accelerated age-related atrophy of cortical and subcortical brain regions, including the hippocampus and the fornix.

Finally, we found evidence that the observed age-dependent decline in limbic structures had some impact on individual differences in episodic memory performance, as individual differences in fornix and hippocampal ISOSF were negatively correlated with differences in delayed verbal recall performance. This finding is consistent with a large body of evidence demonstrating an important role of the hippocampal-fornix axis in mediating age-dependent decline of episodic memory function21.

In conclusion, we provide novel evidence in support of the neuroglia model of aging. We propose that age-related damage to fornix glia, rather than a loss of axons, may cause hippocampal tissue changes associated with reduced metabolism, glia and neuronal loss. These results provide novel insights into the mechanisms underpinning age-dependent decline in limbic structures and suggest that MRI metrics sensitive to neuroglia may potentially provide useful biomarkers of midlife risk of LOAD.

Methods

This study was approved by the Cardiff University Psychology Research Ethics Committee (EC.14.09.09.3843R2). All participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants

Community-dwelling participants between 35 and 75 years of age were recruited from Cardiff University panels and notice boards and via internet and poster advertisements. Exclusion criteria included a history of neurological or psychiatric disease, head injury with loss of consciousness, drug/alcohol dependency, high-risk cardio-embolic source, large-vessel disease, and MRI contraindications. From 211 recruited volunteers, 166 underwent MRI scanning at CUBRIC. Table 1 summarises the demographic, cognitive, and dementia risk information for these 166 participants.

Assessment of genetic and lifestyle related risk factors

Genetic-related risk

Saliva samples were collected with the Oragene-DNA (OG-500) kit (Genotek). APOE genotypes ε2, ε3 and ε4 were determined by TaqMan genotyping of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs7412 and KASP genotyping of SNP rs429358. Genotyping was successful in 165 individuals that underwent an MRI scan (Table 1). Participants also provided information about their family history of dementia, i.e. whether a first-grade relative was affected by LOAD, vascular dementia or Lewy body disease with dementia.

Lifestyle-related risk

Abdominal adiposity was assessed with the waist-hip-ratio (WHR)100. Central obesity was defined as WHR ≥ 0.9 for men and ≥ 0.85 for women. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure was measured with a digital blood pressure monitor (Model UA-631; A&D Medical, Tokyo, Japan). Hypertension was defined as systolic BP ≥ 140 mm Hg. Risk factors of diabetes mellitus, high levels of blood cholesterol, history of smoking and weekly alcohol intake were self-reported. Information about participants’ physical activity over the previous week was collected with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)101. Participants’ intellectual and cognitive functions were assessed with the National Adult Reading Test (NART)102 and the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE)103, episodic memory abilities with the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning test (RAVLT)58,59 and the Rey Complex Figure65, and depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression (PHQ-9)104.

MRI data acquisition

MRI data were acquired on a 3 T MAGNETOM Prisma clinical scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a 32-channels receive-only head coil at CUBRIC.

Anatomical MRI

T1-weighted anatomical images were acquired with a three-dimension (3D) magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo (MP-RAGE) sequence with a 256 × 256 acquisition matrix, TR = 2300 ms, TE = 3.06 ms, TI = 850 ms, flip angle θ = 9°, 176 slices, 1 mm slice thickness, FOV = 256 mm, and acquisition time of ~6 min.

High Angular Resolution Diffusion Imaging (HARDI)

Diffusion data (2 × 2 × 2 mm voxel) were collected with a spin-echo echo-planar dual shell HARDI105 sequence with diffusion encoded along 90 isotropically distributed orientations (30 directions at b-value = 1200 s/mm2 and 60 directions at b-value = 2400 s/mm2) and six non-diffusion weighted scans with dynamic field correction, TR = 9400 ms, TE = 67 ms, 80 slices, 2 mm slice thickness, FOV = 256 × 256 × 160 mm, GRAPPA acceleration factor = 2 and acquisition time of ~15 min.

Quantitative magnetization transfer weighted imaging (qMT)

An optimized 3D MT-weighted gradient recalled-echo sequence106 was used to obtain magnetization transfer-weighted data with TR = 32 ms, TE = 2.46 ms; Gaussian MT pulses, duration t = 12.8 ms; FA = 5°; FOV = 24 cm, and 2.5 × 2.5 × 2.5 mm3 resolution. The following off-resonance irradiation frequencies (Θ) and their corresponding saturation pulse nominal flip angle (ΔSAT) for the 11 MT-weighted images were optimized using Cramer-Rao lower bound optimization: Θ = [1000 Hz, 1000 Hz, 2750 Hz, 2768 Hz, 2790 Hz, 2890 Hz, 1000 Hz, 1000 Hz, 12060 Hz, 47180 Hz, 56360 Hz] and their corresponding ΔSAT = [332°, 333°, 628°, 628°, 628°, 628°, 628°, 628°, 628°, 628°, 332°]. The longitudinal relaxation time, T1, of the system was estimated by acquiring three 3D gradient recalled echo sequence volumes with three different flip angles (θ = 3°, 7°, 15°) using the same acquisition parameters as used in the MT-weighted sequences (TR = 32 ms, TE = 2.46 ms, FOV = 24 cm, 2.5 × 2.5 × 2.5 mm3 resolution). Static magnetic field maps (B0) were collected using two 3D GRE volumes with different echo-times (TE = 4.92 ms and 7.38 ms respectively; TR = 330 ms; FOV = 240 mm; slice thickness 2.5 mm)107.

T2-weighted maps

were acquired with a multi-echo spin echo sequence with five equally spaced echo times (TEs = 13.8 ms – 69 ms), TR = 1600 ms, 19 slices, 5 mm slice thickness, FOV = 240 mm, flip angle θ = 180° and acquisition time of ~6 min.

MRI data processing

The HARDI data were corrected for distortions induced by the diffusion-weighted gradients and artifacts due to head motion with reorientation of the encoding vectors108 in ExploreDTI (Version 4.8.3)109. EPI-induced geometrical distortions were corrected by warping the diffusion-weighted image volumes to down-sampled T1-weighted images with a resolution of 1.5 × 1.5 × 1.5 mm110. After preprocessing, the NODDI model22 was fitted to the dual-shell HARDI data using fast, linear model fitting algorithms of the AMICO framework111. Restricted non-Gaussian diffusion in the intra-axonal space was quantified with ICSF and free isotropic Gaussian diffusion with ISOSF. ODI was modelled with a Watson distribution.

MT-weighted GRE volumes for each participant were co-registered to the MT-volume with the most contrast using a rigid body (6 degrees of freedom) registration to correct for inter-scan motion using Elastix112. The 11 MT-weighted GRE images and T1-maps were modelled by the two-pool Ramani’s pulsed MT approximation113 yielding MPF, kf, and R1 maps. MPF maps were threshholded to an upper intensity limit of 0.3 and kf maps to an upper limit of 3 using the FMRIB’s fslmaths imaging calculator to remove voxels with noise-only data.

A monoexponential decay function was fitted to the T2 images using quimultiecho from the Quantitative Imaging Tools (QUIT) library (http://spinicist.github.io/QUIT). This fitting excluded the first acquired TE due to a non-contained stimulated echo artifact in the first echo of the multi-contrast spin echo Siemens library sequence. R2 was calculated as 1/T2 in second units.

All image modality maps and region of interest masks were spatially aligned to the T1-weighted anatomical volume as reference image with linear affine registration (12 degrees of freedom) using FMRIB’s Linear Image Registration Tool (FLIRT).

Five R2 and four qMT data sets were missing as five participants did not complete the MRI session due to claustrophobia.

Tractography

The RESDORE algorithm114 was applied to identify outliers, followed by whole brain tractography with the damped Richardson-Lucy algorithm (dRL)115 on the 60 direction, b = 2400 s/mm2 HARDI data in single-subject space using in house software114 coded in MATLAB (the MathWorks, Natick, MA). To reconstruct fibre tracts, dRL fibre orientation density functions (fODFs) were estimated at the center of each image voxel. Seed points were positioned at the vertices of a 2 × 2 × 2 mm grid superimposed over the image. The dRL algorithm interpolated local fODF estimates at each seed point and then propagated 0.5 mm along orientations of each fODF lobe above a threshold peak of 0.05. This process was repeated until the minimally subtending peak magnitude fell below 0.05 or the change of direction between successive 0.5 mm steps exceeded an angle of 45°. Tracking was then repeated in the opposite direction from the initial seed point.

The fornix and the PHC were reconstructed with an in-house automated segmentation method based on principal component analysis (PCA) of streamline shape116. This involved the manual reconstruction of a set of tracts from 20 randomly selected datasets, that were then used to train a PCA model of candidate streamline shape and location. The fornix and the PHC tracts were reconstructed by manually applying region of interest (ROI) gates to isolate specific tracts from the whole brain tractography data on colour-coded fiber orientation maps in ExploreDTI following previously published protocols21,57,117,118. The trained PCA shape models were then applied to all datasets: candidate streamlines, i.e. those bridging the gap between estimated end points of the fornix/PHC, were selected from the whole volume tractography and spurious streamlines were excluded by means of a shape comparison with the trained PCA model. All automatic tract reconstructions underwent visual quality control and any remaining spurious fibers that were not consistent with the tract anatomy were removed.

Whole Hippocampal segmentation

Volumetric segmentation of the left and right whole hippocampi from T1- weighted images was performed with the Freesurfer image analysis suite (version 5.3), which is documented online (https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/). Mean intracranial volume fractions (ICV) were extracted for each brain as estimates of individual differences in head sizes. Two datasets had to be excluded from the analysis due to motion artefacts.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted in MATLAB, SPSS version 20119 and the PROCESS computational tool for mediation analysis120. Multiple comparisons were corrected with a False Discovery Rate (FDR) of 5% using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure121. Partial Eta2 (ηp2) and correlation coefficients are reported as indices of effect sizes. Differences in the size of correlation coefficients were tested with the Fisher’s r-to-z transformation122. All reported p-values are two-tailed.

Omnibus multivariate regression analysis was conducted to test for main effects of age, genetic and lifestyle risk factors, sex, education and head size simultaneously on all MRI metrics. Omnibus effects were followed up with post-hoc multivariate covariance analysis testing for effects on individual MRI metrics in all regions of interest while correcting for any confounding variables. The direction of age effects and the relationship between hippocampal and white matter microstructural metrics were investigated with Pearson correlation coefficients.

Linear mediation analysis was then used to test for the indirect effects a*b of hippocampal mediator variables on the direct effects c’ of age on the fornix metrics (Fig. 1, Model A) and for indirect effects a*b of fornix mediator variables on direct age effects c’ on hippocampal differences (Fig. 1, Model B). The significance of indirect and direct effects was assessed with a 95% confidence interval based on bootstrapping with 5000 replacements120.

The impact of genetic and lifestyle risk factors on mediator variables was explored with hierarchical linear regression analyses, and Pearson correlation coefficients between MRI mediator variables and episodic memory measures were calculated to explore brain-cognition relationships.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a Research Fellowship awarded to C.M.-B. from the Alzheimer’s Society and the BRACE Alzheimer’s Charity (grant ref: 208). D.K.J. is supported by a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award (096646/Z/11/Z) and a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award (104943/Z/14/Z). We would like to thank Erika Leonaviciute, Peter Hobden and Sonya Foley-Bozorgzad for their assistance with MRI data acquisition and Rosie Dwyer, Samantha Collins, Abbie Stark, and Emma Blenkinsop for their assistance with the collection and scoring of the behavioral data. We also would like to thank Rhodri Thomas for his assistance with the APOE genotyping of the saliva samples.

Author Contributions

C.M.-B. is the PI of the study and is responsible for the conceptualization, data acquisition and analyses, and drafting of the manuscript. J.P.M. helped with participant recruitment, data acquisition and MRI data processing. R.S. was responsible for the APOE genotyping. F.F. and J.E. implemented the qMT and diffusion MRI protocols and helped with MRI data analyses. R.J.B. was involved in the conceptualisation and advised on statistical data analysis. J.P.A. and D.K.J. provided feedback on the manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

10/17/2019

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Research U. K. Dementia Statistics Hub. https://www.dementiastatistics.org/statistics/prevalence-by-age-in-the-uk (2014).

- 2.Jack CR, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:207–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winblad B, et al. Defeating Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: a priority for European science and society. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:455–532. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Argente-Arizón P, Guerra-Cantera S, Garcia-Segura LM, Argente J, Chowen JA. Glial cells and energy balance. J Mol Endocrinol. 2017;58:R59–R71. doi: 10.1530/JME-16-0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domingues HS, Portugal CC, Socodato R, Relvas JB. Oligodendrocyte, Astrocyte, and Microglia Crosstalk in Myelin Development, Damage, and Repair. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2016;4:71. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2016.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fields RD, et al. Glial Biology in Learning and Cognition. Neuroscientist. 2014;20:426–431. doi: 10.1177/1073858413504465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Bernhardi R, Eugenín-von Bernhardi L, Eugenín J. Microglial cell dysregulation in brain aging and neurodegeneration. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:124. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardy J, Allsop D. Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1991;12:383–388. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90609-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karran E, De Strooper B. The amyloid cascade hypothesis: are we poised for success or failure? J Neurochem. 2016;139(Suppl 2):237–252. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dansokho C, Heneka MT. Neuroinflammatory responses in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2018;125:771–779. doi: 10.1007/s00702-017-1831-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heneka MT, et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:388–405. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarlus H, Heneka MT. Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:3240–3249. doi: 10.1172/JCI90606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartzokis, G. Alzheimer’s disease as homeostatic responses to age-related myelin breakdown. In Neurobiology of Aging 1341–1371 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Angelova, D. & Brown, D. Iron, aging, and neurodegeneration. In Metals 2070–2092 (2015).

- 15.Brown DR. Role of microglia in age-related changes to the nervous system. ScientificWorldJournal. 2009;9:1061–1071. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2009.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braak H, Del Trecidi K. Neuroanatomy and pathology of sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 2015;215:1–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacKinnon DP, Pirlott AG. Statistical approaches for enhancing causal interpretation of the M to Y relation in mediation analysis. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2015;19:30–43. doi: 10.1177/1088868314542878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacKinnon, D. P., Valente, M. J. & Wurpts, I. C. Benchmark validation of statistical models: Application to mediation analysis of imagery and memory. Psychol Methods (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Anblagan D, et al. Coupled changes in hippocampal structure and cognitive ability in later life. Brain Behav. 2018;8:e00838. doi: 10.1002/brb3.838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Metzler-Baddeley C, Jones DK, Belaroussi B, Aggleton JP, O’Sullivan MJ. Frontotemporal connections in episodic memory and aging: a diffusion MRI tractography study. J Neurosci. 2011;31:13236–13245. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2317-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang H, Schneider T, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Alexander DC. NODDI: practical in vivo neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging of the human brain. Neuroimage. 2012;61:1000–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bourbon-Teles, J. et al. Myelin breakdown in human Huntington’s disease: Multi-modal evidence from diffusion MRI and quantitative magnetization transfer. Neuroscience (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Caeyenberghs K, Metzler-Baddeley C, Foley S, Jones DK. Dynamics of the Human Structural Connectome Underlying Working Memory Training. J Neurosci. 2016;36:4056–4066. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1973-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Santis S, Drakesmith M, Bells S, Assaf Y, Jones DK. Why diffusion tensor MRI does well only some of the time: variance and covariance of white matter tissue microstructure attributes in the living human brain. Neuroimage. 2014;89:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiskopf N, et al. Quantitative multi-parameter mapping of R1, PD(*), MT, and R2(*) at 3T: a multi-center validation. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:95. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sled, J. G. Modelling and interpretation of magnetization transfer imaging in the brain. Neuroimage (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Schmierer K, et al. Quantitative magnetization transfer imaging in postmortem multiple sclerosis brain. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26:41–51. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ou X, Sun SW, Liang HF, Song SK, Gochberg DF. Quantitative magnetization transfer measured pool-size ratio reflects optic nerve myelin content in ex vivo mice. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:364–371. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whitaker KJ, et al. Adolescence is associated with genomically patterned consolidation of the hubs of the human brain connectome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:9105–9110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601745113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beaulieu C, Allen PS. Water diffusion in the giant axon of the squid: implications for diffusion-weighted MRI of the nervous system. Magn Reson Med. 1994;32:579–583. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910320506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alexander AL, Lee JE, Lazar M, Field AS. Diffusion tensor imaging of the brain. Neurotherapeutics. 2007;4:316–329. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Basser PJ, Pierpaoli C. Microstructural and physiological features of tissues elucidated by quantitative-diffusion-tensor MRI. J Magn Reson B. 1996;111:209–219. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.By S, Xu J, Box BA, Bagnato FR, Smith SA. Application and evaluation of NODDI in the cervical spinal cord of multiple sclerosis patients. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;15:333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schneider T, et al. Sensitivity of multi-shell NODDI to multiple sclerosis white matter changes: a pilot study. Funct Neurol. 2017;32:97–101. doi: 10.11138/FNeur/2017.32.2.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koenig SH. Cholesterol of myelin is the determinant of gray-white contrast in MRI of brain. Magn Reson Med. 1991;20:285–291. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910200210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ceckler, T., Wolff, S., Yip, V. & Balaban, R. Dynamic and chemical factors affecting water proton relaxation by macromolecules. in Journal of Magnetic Resonance 637–645 (1992).

- 38.Levesque IR, et al. Quantitative magnetization transfer and myelin water imaging of the evolution of acute multiple sclerosis lesions. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:633–640. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serres S, et al. Systemic inflammatory response reactivates immune-mediated lesions in rat brain. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4820–4828. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0406-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giulietti G, et al. Quantitative magnetization transfer provides information complementary to grey matter atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease brains. Neuroimage. 2012;59:1114–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lorio S, et al. Neurobiological origin of spurious brain morphological changes: A quantitative MRI study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016;37:1801–1815. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rooney WD, et al. Magnetic field and tissue dependencies of human brain longitudinal 1H2O relaxation in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:308–318. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Langkammer C, et al. Quantitative MR imaging of brain iron: a postmortem validation study. Radiology. 2010;257:455–462. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alexander AL, et al. Characterization of cerebral white matter properties using quantitative magnetic resonance imaging stains. Brain Connect. 2011;1:423–446. doi: 10.1089/brain.2011.0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fischl B, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33:341–355. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han X, Fischl B. Atlas renormalization for improved brain MR image segmentation across scanner platforms. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2007;26:479–486. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2007.893282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iglesias JE, et al. Bayesian longitudinal segmentation of hippocampal substructures in brain MRI using subject-specific atlases. Neuroimage. 2016;141:542–555. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iglesias JE, et al. A computational atlas of the hippocampal formation using ex vivo, ultra-high resolution MRI: Application to adaptive segmentation of in vivo MRI. Neuroimage. 2015;115:117–137. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Di Battista AM, Heinsinger NM, Rebeck GW. Alzheimer’s Disease Genetic Risk Factor APOE-ε4 Also Affects Normal Brain Function. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2016;13:1200–1207. doi: 10.2174/1567205013666160401115127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reinvang I, Espeseth T, Westlye LT. APOE-related biomarker profiles in non-pathological aging and early phases of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:1322–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hersi, M. et al. Risk factors associated with the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review of the evidence. Neurotoxicology (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Bartzokis George, Lu Po H., Geschwind Daniel H., Tingus Kathleen, Huang Danny, Mendez Mario F., Edwards Nancy, Mintz Jim. Apolipoprotein E Affects Both Myelin Breakdown and Cognition: Implications for Age-Related Trajectories of Decline Into Dementia. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62(12):1380–1387. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Westlye LT, Reinvang I, Rootwelt H, Espeseth T. Effects of APOE on brain white matter microstructure in healthy adults. Neurology. 2012;79:1961–1969. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182735c9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dommermuth R, Ewing K. Metabolic Syndrome: Systems Thinking in Heart Disease. Prim Care. 2018;45:109–129. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ricci G, Pirillo I, Tomassoni D, Sirignano A, Grappasonni I. Metabolic syndrome, hypertension, and nervous system injury: Epidemiological correlates. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2017;39:8–16. doi: 10.1080/10641963.2016.1210629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ronan L, et al. Obesity associated with increased brain age from midlife. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;47:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Metzler-Baddeley C, Baddeley RJ, Jones DK, Aggleton JP, O’Sullivan MJ. Individual differences in fornix microstructure and body mass index. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rey, A. L. examen psychologique dans les cas d’encephalopathie traumatique. In Archives de Psychologie 215–285 (1941).

- 59.Schmidt, M. Rey Auditory and Verbal Learning Test. A handbook. (Western Psychological Association, Los Angeles, 1996).

- 60.Bartzokis, G. Age-related myelin breakdown: a developmental model of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging25, 5–8; author reply 49–62 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Bartzokis G, et al. Brain ferritin iron may influence age- and gender-related risks of neurodegeneration. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:414–423. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Braak H, Del Tredici K. The preclinical phase of the pathological process underlying sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2015;138:2814–2833. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ou X, Sun SW, Liang HF, Song SK, Gochberg DF. The MT pool size ratio and the DTI radial diffusivity may reflect the myelination in shiverer and control mice. NMR Biomed. 2009;22:480–487. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alonso-Ortiz E, Levesque IR, Pike GB. MRI-based myelin water imaging: A technical review. Magn Reson Med. 2015;73:70–81. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tang Y, Nyengaard JR, Pakkenberg B, Gundersen HJ. Age-induced white matter changes in the human brain: a stereological investigation. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:609–615. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pakkenberg B, et al. The normal brain: a new knowledge in different fields. Ugeskr Laeger. 1997;159:723–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pakkenberg B, Gundersen HJ. Neocortical neuron number in humans: effect of sex and age. J Comp Neurol. 1997;384:312–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pakkenberg B, et al. Aging and the human neocortex. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38:95–99. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marner L, Nyengaard JR, Tang Y, Pakkenberg B. Marked loss of myelinated nerve fibers in the human brain with age. J Comp Neurol. 2003;462:144–152. doi: 10.1002/cne.10714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peters A, Sethares C, Moss MB. How the primate fornix is affected by age. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:3962–3980. doi: 10.1002/cne.22434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vavasour IM, Laule C, Li DK, Traboulsee AL, MacKay AL. Is the magnetization transfer ratio a marker for myelin in multiple sclerosis? J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;33:713–718. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Serres S, et al. Comparison of MRI signatures in pattern I and II multiple sclerosis models. NMR Biomed. 2009;22:1014–1024. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Coleman PD, Buell SJ, Magagna L, Flood DG, Curcio CA. Stability of dendrites in cortical barrels of C57BL/6N mice between 4 and 45 months. Neurobiol Aging. 1986;7:101–105. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(86)90147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Louie EA, Gochberg DF, Does MD, Damon BM. Transverse relaxation and magnetization transfer in skeletal muscle: effect of pH. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:560–569. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martin SA, et al. Regional metabolic heterogeneity of the hippocampus is nonuniformly impacted by age and caloric restriction. Aging Cell. 2016;15:100–110. doi: 10.1111/acel.12418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Laßek M, et al. APP Deletion Accounts for Age-Dependent Changes in the Bioenergetic Metabolism and in Hyperphosphorylated CaMKII at Stimulated Hippocampal Presynaptic Active Zones. Front Synaptic Neurosci. 2017;9:1. doi: 10.3389/fnsyn.2017.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brun A, Englund E. A white matter disorder in dementia of the Alzheimer type: a pathoanatomical study. Ann Neurol. 1986;19:253–262. doi: 10.1002/ana.410190306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brun A, Englund E. Brain changes in dementia of Alzheimer’s type relevant to new imaging diagnostic methods. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1986;10:297–308. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(86)90009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Englund E, Brun A. White matter changes in dementia of Alzheimer’s type: the difference in vulnerability between cell compartments. Histopathology. 1990;16:433–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1990.tb01542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Heneka MT. Inflammasome activation and innate immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 2017;27:220–222. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zeineh MM, et al. Activated iron-containing microglia in the human hippocampus identified by magnetic resonance imaging in Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:2483–2500. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Venegas C, et al. Microglia-derived ASC specks cross-seed amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2017;552:355–361. doi: 10.1038/nature25158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Barrientos RM, Kitt MM, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Neuroinflammation in the normal aging hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2015;309:84–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kullmann S, et al. Specific white matter tissue microstructure changes associated with obesity. Neuroimage. 2016;125:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Verstynen TD, et al. Competing physiological pathways link individual differences in weight and abdominal adiposity to white matter microstructure. Neuroimage. 2013;79:129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pievani M, et al. APOE4 is associated with greater atrophy of the hippocampal formation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2011;55:909–919. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.12.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chételat G, Fouquet M. Neuroimaging biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease in asymptomatic APOE4 carriers. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2013;169:729–736. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2013.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fouquet M, Besson FL, Gonneaud J, La Joie R, Chételat G. Imaging brain effects of APOE4 in cognitively normal individuals across the lifespan. Neuropsychol Rev. 2014;24:290–299. doi: 10.1007/s11065-014-9263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rawle MJ, et al. Apolipoprotein-E (Apoe) ε4 and cognitive decline over the adult life course. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8:18. doi: 10.1038/s41398-017-0064-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mahoney-Sanchez L, Belaidi AA, Bush AI, Ayton S. The Complex Role of Apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s Disease: an Overview and Update. J Mol Neurosci. 2016;60:325–335. doi: 10.1007/s12031-016-0839-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Khan W, et al. No differences in hippocampal volume between carriers and non-carriers of the ApoE ε4 and ε2 alleles in young healthy adolescents. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;40:37–43. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dell’Acqua F, et al. Tract Based Spatial Statistic Reveals No Differences in White Matter Microstructural Organization between Carriers and Non-Carriers of the APOE ɛ4 and ɛ2 Alleles in Young Healthy Adolescents. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;47:977–984. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tuminello ER, Han SD. The apolipoprotein e antagonistic pleiotropy hypothesis: review and recommendations. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;2011:726197. doi: 10.4061/2011/726197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liu CC, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:106–118. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ritchie, K. et al. The midlife cognitive profiles of adults at high risk of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease: The PREVENT study. Alzheimers Dement (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 96.Markham JA, McKian KP, Stroup TS, Juraska JM. Sexually dimorphic aging of dendritic morphology in CA1 of hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2005;15:97–103. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gur RC, et al. Gender differences in age effect on brain atrophy measured by magnetic resonance imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2845–2849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pfefferbaum A, et al. Variation in longitudinal trajectories of regional brain volumes of healthy men and women (ages 10 to 85 years) measured with atlas-based parcellation of MRI. Neuroimage. 2013;65:176–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sullivan EV, Rosenbloom M, Serventi KL, Pfefferbaum A. Effects of age and sex on volumes of the thalamus, pons, and cortex. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(03)00044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Organisation, W. H. Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip-Ratio: Report of a WHO expert consultation. (2008).

- 101.Craig CL, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nelson, H. E. The National Adult Reading Test-Revised (NART-R): Test manual. (National Foundation for Educational Research-Nelson., Windsor, UK, 1991).

- 103.Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tuch DS, et al. High angular resolution diffusion imaging reveals intravoxel white matter fiber heterogeneity. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48:577–582. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cercignani M, Alexander DC. Optimal acquisition schemes for in vivo quantitative magnetization transfer MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:803–810. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jezzard P, Balaban RS. Correction for geometric distortion in echo planar images from B0 field variations. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:65–73. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Leemans A, Jones DK. The B-matrix must be rotated when correcting for subject motion in DTI data. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:1336–1349. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Leemans A, Jeurissen B, Sijbers J & DK., J. ExploreDTI: a graphical toolbox for processing, analyzing, and visualizing diffusion MR data. In 17th Annual Meeting of Intl Soc Mag Reson Med 3537 (Hawaii, USA., 2009).

- 110.Irfanoglu MO, Walker L, Sarlls J, Marenco S, Pierpaoli C. Effects of image distortions originating from susceptibility variations and concomitant fields on diffusion MRI tractography results. Neuroimage. 2012;61:275–288. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Daducci A, et al. Accelerated Microstructure Imaging via Convex Optimization (AMICO) from diffusion MRI data. Neuroimage. 2015;105:32–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Klein S, Staring M, Murphy K, Viergever MA, Pluim JP. elastix: a toolbox for intensity-based medical image registration. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2010;29:196–205. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2009.2035616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ramani A, Dalton C, Miller DH, Tofts PS, Barker GJ. Precise estimate of fundamental in-vivo MT parameters in human brain in clinically feasible times. Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;20:721–731. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(02)00598-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Parker, G. Robust processing of diffusion weighted image data. (Unpublished PhD thesis, Cardiff University, 2014).

- 115.Dell’acqua F, et al. A modified damped Richardson-Lucy algorithm to reduce isotropic background effects in spherical deconvolution. Neuroimage. 2010;49:1446–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Parker, G., Rosin, P. & Marshall, D. Automated segmentation of diffusion weigthed MRI tractography. (Presented a the AVA, AVA/BMVA Meeting on Biological and Computer Vision Cambridge, UK, 2012).

- 117.Metzler-Baddeley C, et al. Cingulum Microstructure Predicts Cognitive Control in Older Age and Mild Cognitive Impairment. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:17612–17619. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3299-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Metzler-Baddeley C, et al. Temporal association tracts and the breakdown of episodic memory in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2012;79:2233–2240. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827689e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.IBM. SPSS Statistics, Version 20.0. (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, 2011).

- 120.Hayes, A. F. PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. (2012).

- 121.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Fisher, R. A. Statistical methods for research workers. (Oliver and Boyd, London, 1936).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.