Several changes are needed to foster the next generation of minority health and health disparities research. The impetus for the changes includes three points: definition of minority health and health disparities, the focus only on social determinants, and the emerging science of health disparities research that will lead to new discoveries.

DEFINITION CONCERNS

Minority health and health disparities are related but different fields of research. Current literature often assumes that “minority health” differences equate to “health disparities” with the same contributing factors.1 Equating minority health and health disparities assumes that all minorities have worse health outcomes than the rest of the population; yet, in some important conditions, some minority groups have better health outcomes than Whites.2 Although minority health has an assumed intention and population identification, health disparities needs to be defined, and the current populations of focus clarified. Health disparities populations are broader than racial and ethnic minorities, and include underserved rural residents, populations with less privileged socioeconomic status, and sexual and gender minorities that confront discrimination and social disadvantage.3 Moreover, there are multiple terms referenced, such as health disparities, health equity, and health injustice, among others. Reference to these distinct definitions with the development of standardized metrics and measures is needed to advance both fields of research. Most current definitions of health disparities conflate the potential causes of the disparities within the definition. These causes often include social and structural determinants, which are examples of etiologic factors of health disparities, not the definition.

BEYOND SOCIAL DETERMINANTS

The current generation of research in health disparities needs to expand beyond social determinants. Studies have shown the association of biological and environmental factors that influence health care and health disparities.4 Although social determinants contribute to poor health and to health disparities, research findings demonstrate that health disparities exist, even without poverty, and with high education and adequate access to care.5 Expanding the potential contributors incorporates current knowledge of biology and environmental systems, as well as sets the platform for real-world setting research that uses complex models for an enhanced understanding of etiologic factors that can be utilized for designing targeted interventions.

THE EMERGING SCIENCE

As academic disciplines or fields of study, minority health and health disparities are nascent without classic textbooks, with selected ad hoc curriculums, incomplete theory development, diffuse journals in multiple disciplines, and conferences with limited support. To advance the next generation of research for improving minority health and reducing health disparities, definitions, measures, contributors, and theories must be demarcated, such that a discipline can be solidified and a diverse biomedical workforce can be propagated.

To achieve this end, the National Institutes of Health through the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities embarked on a yearlong process to reexamine definitions for minority health and health disparities in order to redefine and distinguish the two related fields of scientific focus. These new definitions require a different approach to conducting minority health or health disparities research, which sets the charge for the science visioning workshops. These definitions and results from the visioning process research collectively provide a framework for minority health and health disparities to mature into a fully developed discipline.

Definition of Minority Health Research

Minority health is redefined as “health characteristics and attributes of racial and/or ethnic minority groups (defined by Office of Management and Budget), who are socially disadvantaged due in part by being subject to potential discriminatory acts.” Minority health research examines singularly and in combination the attributes, characteristics, behaviors, biology, and other factors that influence the health outcomes of minority racial and ethnic groups, including within-group or ethnic subpopulations, with the goal of understanding mechanisms and improving health.

Minorities continue to experience social disadvantages seen as contributors to poorer health conditions often because of internalized and external stressors.6 Evidence suggests that African Americans and Latinos perceive a prominent level of discrimination that may even worsen as socioeconomic status improves.7 This heightened perception may partially explain some actual, as well as subjective, health outcomes affected by stressors. Theoretically, the influence of social disadvantage and discrimination can be mitigated and associated stress reduced resulting in improved health and well-being. These constructs provide one justification for why minority populations should be studied, regardless of disparities.

Definition of Health Disparities

The proposed novel definition of health disparity is “a health difference that adversely affects defined disadvantaged populations, based on one or more health outcomes.” The outcomes identified for the new definition are

-

1.

higher incidence or prevalence of disease, including earlier onset or more aggressive progression;

-

2.

premature or excessive mortality from specific conditions;

-

3.

greater global burden of disease, such as disability adjusted life years, as measured by population health metrics;

-

4.

poorer health behaviors and clinical outcomes related to the aforementioned; and

-

5.

worse outcomes on validated self-reported measures that reflect daily functioning or symptoms from specific conditions.

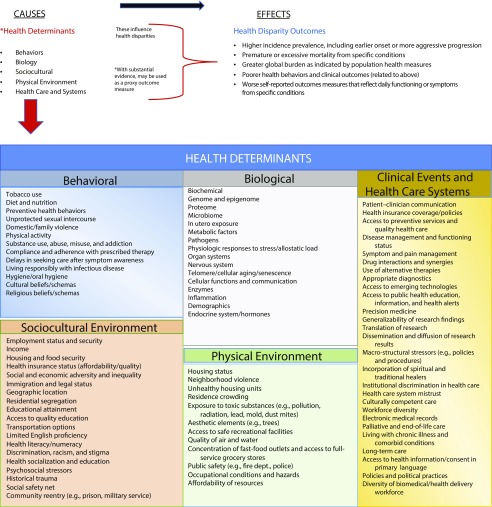

This novel definition seeks to delineate causes from outcomes resulting in a health disparity, which is distinguishable from other existing definitions that often conflate the two. It advocates for an approach including biological, cultural, and environmental determinants that impact a health disparity and—within the context of health care—that is multidisciplinary regarding how knowledge is translated into interventions to reduce health disparities. Figure 1 illustrates health determinants as contributing factors on the adverse health disparity outcomes.

FIGURE 1—

Relationship Between Health Determinants and Health Disparity Outcomes

Mechanisms Leading to Health Disparities

Social determinants, such as poverty and lack of access to care, have been the focus of health disparities research for decades. Today, it is known that health disparities may exist even when minorities have higher socioeconomic status, are highly educated, and have adequate access to care, which suggest that additional factors, such as biology, cultural, and environmental interactions and interpersonal and structural discrimination, may contribute to the disparity.1 Although social determinants continue to be critical components, scientific advances suggest additional health determinants need to be considered in multilevel etiologic analyses to understand the contributors of health disparities. The following health determinants are domains of influence or mechanisms that affect health disparities: behavior and lifestyle, biological factors, sociocultural environment, physical environment, and health care and related systems.

Complex System Analysis

The comprehensiveness of the health determinants advocates for more complex systems analyses reflective of real-world settings in health disparities research. The field must advance to a multilevel and multifactor analytic approach to identify relevant components that can be used to design targeted interventions that may have a more sustainable impact. As a result of the definitions and this more complex approach, measures and metrics need to be determined and standardized, and advanced methodologies need to be used to design and analyze multilevel real-world hypothesis testing of initiatives to improve minority health and reduce health disparities.

CONCLUSIONS

The next generation of research needs to implement these operational definitions to construct research projects to improve minority health and reduce health disparities. Once that premise is determined, more complex models of analyses would be needed to better understand the impact of multiple and interacting health determinants on health disparities. As a deeper understanding of the etiology or mechanisms of minority health and health disparities are known, better and complex interventions may be designed to improve minority health and to reduce or eliminate health disparities more effectively. To launch this next generation of minority health and health disparities research, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities led the science visioning workshops.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), National Institutes of Health (NIH).

National Institutes of Health Defining Working Group Members were key in establishing the novel definitions—Sue Hamman, PhD (National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research); Jane Lockmuller, PhD (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases); Shefa Gordon, PhD (National Eye Institute); William Riley, PhD (Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research); Anne E. Sumner, MD (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases); Marin Allen, PhD (NIH Office of the Director); and Worta McCaskill-Stevens, MD (National Cancer Institute).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors are salaried employees of the NIH. The authors do not have any financial or other competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Daly B, Olopade OI. A perfect storm: how tumor biology, genomics, and health care delivery patterns collide to create a racial survival disparity in breast cancer and proposed interventions for change. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(3):221–238. doi: 10.3322/caac.21271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reitzel LR, Nguyen N, Li N, Xu L, Regan SD, Sturgis EM. Trends in thyroid cancer incidence in Texas from 1995 to 2008 by socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity. Thyroid. 2014;24(3):556–567. doi: 10.1089/thy.2013.0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellemers N, Barreto M. Modern discrimination: how perpetrators and targets interactively perpetuate social disadvantage. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2015;3:142–146. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris JC, Benzinger TLS, Buckles VD et al. Racial differences and similarities in molecular biomarkers for AD. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(7):P560–P561. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newman LA, Griffith KA, Jatoi I, Simon MS, Crowe JP, Colditz GA. Meta-analysis of survival in African American and White American patients with breast cancer: ethnicity compared with socioeconomic status. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(9):1342–1349. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmitt MT, Branscombe NR, Postmes T, Garcia A. The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2014;140(4):921–948. doi: 10.1037/a0035754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colen CG, Ramey DM, Cooksey EC, Williams DR. Racial disparities in health among nonpoor African Americans and Hispanics: the role of acute and chronic discrimination. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]