Abstract

Background and aim of the work: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) is an interstitial lung disease, which progressively leads to severe disability and death. The average survival expectancy, ranges from 3 to 5 years from diagnosis, and the available medicines do not lead to healing. The progression of IPF lead to a decline in forced vital capacity (FVC), dyspnea, cough, continuous sleep interruptions, resulting in increased fatigue and deteriorating quality of life (QOL), progressive limitation of daily life activities and social life, with repercussions on psychological and emotional well-being, aggravated by anxiety, loss of sense of self-confidence and depression. The aim of the study was to evaluate how the support groups influence the psychological well-being of people with IPF and their family members. Methods: A pre-post test pilot study with a single group was conducted in a university hospital in Northern Italy, a centre for diagnosis and treatment of IPF. A support group was conducted by a nurse and entirely dedicated to people with IPF and their family members. Eighteen participants were enrolled in the support group. To measure the changes in psychological well-being was chosen the Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWBI), which was administered at the time of enrolment to the group and after six months of attendance. Results: Even if the effect is not statistically significant, the paired t-test showed that the participation in a support group conducted by a nurse, could increase psychological well-being in all of its dimensions: anxiety, depression, positivity, self-control, overall health, and vitality. Conclusions: Despite the null association, the increase of psychological well-being, closely related to the quality of life, indicates the need to further studies. In the absence of effective pharmacological treatments for healing, the support groups represent an opportunity for the wellbeing of the IPF patients and their caregivers.

Keywords: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, support groups, quality of life, psychological well-being

Background

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) is a rare disease of unknown etiology, that damages the interstitial tissue of the lungs. It affects more often men than women, older than 65 years of age. The average survival is ~ 3-5 years from the time of diagnosis (1, 2).

Until a few years ago, the treatment was limited to oxygen therapy, respiratory physiotherapy, palliative care and, in a small number of cases, lung transplantation (1, 3). In 2011, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved the pirfenidone, an antifibrotic drug with anti-inflammatory properties, for the treatment of adult patients with IPF with a favorable cost-benefit profile (4). In 2015, the EMA approved also the nintedanib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (5).

The IPF progresses insidiously, with a decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) for untreated subjects, ranging from 150 to 200 ml per year (6). Patients present progressive dyspnea, often accompanied by cough; this involves continuous sleep interruptions, resulting in increased fatigue, with progressive limitation of daily life activities and social life, with repercussions on psychological and emotional well-being, aggravated by anxiety and loss of sense of self-confidence (7-13). Approximately, 25% of patients reported symptoms of depression (7).

The effects of the disease have repercussions also on the caregivers (14-18). Providing support to family members of patients with IPF, has proven to have beneficial effects; for example, family members who attended IPF management programs conducted by a nurse, together with their loved ones suffering from IPF, reported a significant decrease in stress levels and an increase in adaptive coping strategies, compared to those who didn’t follow this type of program (19).

Qualitative studies have shown that participation in support groups, it makes the patients feel less isolated, and improve the perception of their condition. Studies also found it is useful to talk to other people with the same condition. In general, people with IPF and their family members, express the need for greater support, as well as receiving information and education to manage the disease (12-19).

Support for people with IPF and their caregivers is also recommended by the guidelines, including the latest given by NICE, which provide for specialist nurses to supply information and support throughout the course of the disease (20).

Support groups have the function of educating and supporting, and should be considered a true form of non-pharmacological therapy. The benefits of support groups have been known already since the eighties. A review of the literature by Ganster & Victor in 1988 (21), demostrates a relationship between lack of psychological support and suicide, depression and anxiety. People who receive good support in the presence of stressful and challenging situations, have a better adaptation, both physically and psychologically. Good levels of psychological and social support provide a greater chance of survival in the event of illness (22).

Subjects with disabling chronic conditions, together with their family members, are among the categories of people who benefit most from support groups. The effectiveness of a support group is based on the ability to reduce isolation through contact and interaction with others, on the opportunity of intimate conversations that permit the expression of emotions and discussions, on the ability to change perceptions and lead to a more balanced and positive view of the participants’ status, and finally on the opportunity to improve adaptive coping strategies, also through learning from the experience of others (22).

In a qualitative study, respondents were interviewed about the needs of people with IPF, and they expressed the need to have informations and support (12).

IPF is often accompanied by a deterioration in the quality of life, due to a progression of symptomatology, resulting in worsening of the emotional state (8, 23); for this reason IPF represents a potential field for the application of support groups, even though the effectiveness of this intervention has not been sufficiently investigated (17). Nowadays there is a greater focus on the quality of life in IPF patients (24) and over the last several years, support groups for patients with IPF have expanded (25).

Support groups can decrease anxiety and depression, are helpful in educating patients and family caregivers, and can improve wellbeing (26). In oncology, support groups have shown their merits in improving the quality of life of the patients (27, 28). There is a greater focus also on the quality of life in IPF patients (24) and, over the last several years, the support groups for patients with IPF have expanded (25). Neverless, only few studies have looked at the effect of support groups on the quality of life of IPF patients and family caregivers (19, 29), and the effectiveness of this intervention has not been sufficiently investigated (17).

Aim

The aim of the study was to evaluate the benefits of a support group led by a nurse, for patients affected by IPF and their family members, to improve the psychological well-being, in its six dimensions: vitality, self-control, positivity, general health, depressed mood and anxiety.

Method

Participants

A convenience sample of 18 people (IPF patients and their relatives) was enrolled, between January and June 2015, at a Centre for Rare Lung Diseases of a university hospital in the north of Italy. Inclusion criteria for patients included a confirmed diagnosis of IPF according to international guidelines. Patients of all levels of disease and their family members (wives, husbands, sons and daughters) were included, as the purpose of the study was to evaluate for the first time the effectiveness of a support group in a heterogeneous sample of patients with IPF and their relatives. All participants gave consent to participate in the study and for the publication of the data in anonymous form.

A single group pre-post study was conducted to investigate the psychological well-being before and after attending the support group for six months. Meetings were held once a month, for two hours, in a classroom of the University Hospital, seat of the Centre for Rare Lung Diseases and were conducted by a nurse.

The group had the purpose of creating a support network and a setting to share experiences, to receive comfort from people able to understand the impact of this disease on people’s lives and, at the same time, to offer each participant the opportunity to help others. In a climate of mutual respect, where privacy was guaranteed, participants shared ideas and experiences and learned from each other, self care strategies.

In addition to this, the support group had a role of stimulating pharmaceutical companies, research groups, health and governmental organizations, through spokespeople for the needs of this category of sick people (30). The group has also been involved in awareness-raising and knowledge-based initiatives on this rare disease, towards the general population, the physician and other healthcare professionals.

The presence of an expert nurse in the pathology and its management, ensured the correctness and actuality of information shared by the group, integrating and updating the information already held by the participants.

Instrument

A variety of tools are used to assess the impact of IPF on well-being and quality of life, however there is a paucity of specific well-validated tools and a lack of consensus on which tools to use for care and research (31, 32).

The chosen tool was a self-compiled qustionnaire, the PGWBI (Psychological General Well-Being Index), which was given to the participants, at the time of enrollment and again after six months of attendance. The PGWBI is a 22-item, multiple-choice questionnaire, with high internal consistency, reliability and validity, that has been used in previous studies related to quality of life. The PGWBI provides scores for anxiety (5 item), depression (3 item), positivity (4 item), self control (3 item), general health (3 item) and vitaliy (4 item).

The scale ranges from 0 to 5 in a Likert scale, and a synthetic index that ranges from 0 (most negative affective experience) to 110 (most positive affective experience) (33).

For this study the validated Italian version was used (34).

Data analysis

Statistical analyses of aggregate data, referring to patients and family members, were performed using the Stata software program, ver. 14 (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). The paired t-test was assessed to determine whether the mean score of the six dimensions of PGWBI, were different at the beginning and at the end of the study. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All results are presented as mean and standard deviation, unless otherwise specified.

Results

The mean age of the 18 subjects was 66.5 years old (DS 10.93) and most were women (55%). The patients were 10 (55%), and the caregivers were 8 (45%).

Table 1 shows the results by item; as it can be see, the average scores show an increase between pre and post-treatment in each item, even if statistical significance has not been achieved in any item.

Table 1.

Pre and post mean difference in each item of the Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWBI) (Dupuy, 1984)

| N = 18 | Mean (SD) pre |

Mean (SD) post |

Post-pre difference (95%CI) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | ||||

| 1. During the past month, how have you been feeling in general? | 2.61 (0.92) | 2.78 (1.00) | 0.17 (-0.41 – 0.74) | 0.547 |

| 2. During the past month, how often were you bothered by any illness, bodily disorder, aches or pain? | 2.78 (1.44) | 3.33 (1.24) | 0.56 (-0.43 – 1.54) | 0.250 |

| 3. During the past month, did you feel depressed? | 3.61 (1.46) | 4.28 (0.57) | 0.67 (-0.08 – 1.41) | 0.076 |

| 4. During the past month, have you been in firm control of your behavior, thoughts, emotions or feelings? | 3.22 (1.70) | 3.56 (0.98) | 0.33 (-0.48 – 1.15) | 0.402 |

| 5. During the past month, have you been bothered by nervousness or your “nerves”? | 3.94 (0.80) | 4.28 (0.57) | 0.33 (-0.08 – 0.75) | 0.111 |

| 6. During the past month, how much energy pop, or vitality did you have or feel? | 2.83 (1.25) | 3.22 (0.81) | 0.39 (-0.23 – 1.01) | 0.202 |

| 7. During the past month, I felt downhearted and blue. | 3.44 (1.10) | 3.50 (0.62) | 0.06 (-0.34 – 0.45) | 0.773 |

| 8. During the past month, were you generally tense-or did you feel any tension? | 2.83 (1.10) | 3.28 (0.75) | 0.44 (-0.13 – 1.02) | 0.119 |

| 9. During the past month, how happy, satisfied, or pleased have you been with your personal life? | 2.22 (1.35) | 2.44 (0.86) | 0.22 (-0.43 – 0.87) | 0.481 |

| 10. During the past month, did you feel healthy enough to carry out the things you like to do or had to do? | 3.17 (1.42) | 3.67 (0.91) | 0.50 (-0.25 – 1.25) | 0.177 |

| 11. During the past month, have you felt so sad discouraged, hopeless, or had so many problems that you wondered if any things was worthwhile? | 3.89 (1.49) | 4.50 (0.62) | 0.61 (-0.10 – 1.32) | 0.086 |

| 12. During the past month, I woke up feeling fresh and rested. | 2.94 (1.43) | 3.17 (1.29) | 0.23 (-1.15 – 0.69) | 0.615 |

| 13. During the past month, have you been concerned, worried, or had any fears about your health? | 3.17 (1.10) | 3.56 (0.70) | 0.39 (-0.32 – 1.10) | 0.261 |

| 14. During the past month, have you had any reason to wonder if you were losing your mind, or losing control over the way you act, talk, think, feel or of your memory? | 3.44 (1.65) | 3.72 (1.49) | 0.28 (-0.61 – 1.16) | 0.516 |

| 15. During the past month, my daily life was full of things that were interesting to me. | 2.94 (1.35) | 3.22 (1.06) | 0.28 (-0.23 – 0.78) | 0.263 |

| 16. During the past month, did you feel active, vigorous, or dull, sluggish? | 2.61 (1.20) | 2.72 (1.13) | 0.11 (-0.70 – 0.89) | 0.767 |

| 17. During the past month, have you been anxious, worried, or upset? | 3.89 (0.90) | 4.11 (0.58) | 0.22 (-0.28 – 0.72) | 0.361 |

| 18. During the past month, I was emotionally stable and sure of myself. | 3.11 (1.41) | 3.50 (1.10) | 0.39 (-0.15 – 0.93) | 0.149 |

| 19. During the past month, did you feel relaxed, at ease or high strung, tight, or keyed-up? | 2.78 (1.26) | 3.39 (0.85) | 0.61 (-0.24 – 1.47) | 0.150 |

| 20. During the past month, I felt cheerful, lighthearted. | 2.72 (1.18) | 3.00 (0.97) | 0.28 (-0.33 – 0.89) | 0.350 |

| 21. During the past month, I felt tired, worn out, used up, or exhausted. | 2.94 (1.43) | 3.44 (1.04) | 0.50 (-0.12 – 1.12) | 0.108 |

| 22. During the past month, have you been under or felt you were under any strain, stress, or pressure? | 3.17 (1.47) | 3.50 (1.10) | 0.33 (-0.68 – 1.34) | 0.495 |

Range of scores: from 0 to 5 on a Likert scale - High scores indicate positive wellbeing

Table 2 shows the results for each dimension. Scores are constructed so that they have low values in the worst state of well-being and high values in the best state of well-being.

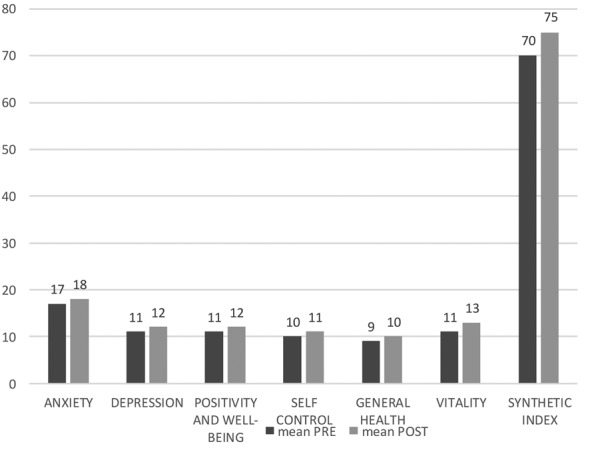

All dimensions have increased in average scores, despite a null association between the pre and the post-intervention test (anxiety, p=0.156; depression, p=0.212; positivity, p=0.262; self control, p=0.753; general health, p=0.403; vitality, p=0.082 and synthetic index, p=0.166). The biggest increase in average score has occured in the dimension of anxiety (post-pre difference 1.67, 95%CI -0.70 – 4.03), while the minor increase has occured in the dimension of self control (post-pre difference 0.28, 95%CI -1.56 – 2.11).

Figures 1 graphically show post-intervention variations related to the six dimensions and the synthetic index.

Figure 1.

Post-intervention variations related to the PGWBI six dimensions and synthetic index

Table 2.

Pre and post mean difference related to the six dimensions and the synthetic index of the Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWBI) (Dupuy, 1984)

| N = 18 | Mean (SD) pre |

Mean (SD) post |

Post-pre difference (95%CI) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | ||||

| Anxiety 0-25* | 16.72 (4.14) | 18.39 (2.70) | 1.67 (-0.70 – 4.03) | 0.156 |

| Depression 0-15* | 11.17 (3.57) | 12.17 (1.42) | 1.00 (-0.63 – 2.63) | 0.212 |

| Positivity and well-being 0-20* | 10.61 (3.94) | 11.56 (3.01) | 0.94 (-0.77 – 2.66) | 0.262 |

| Self control 0-15* | 10.22 (3.61) | 10.50 (2.71) | 0.28 (-1.56 – 2.11) | 0.753 |

| General health 0-15* | 9.28 (3.75) | 10.11 (2.25) | 0.83 (-1.22 – 2.88) | 0.403 |

| Vitality 0-20* | 11.11 (4.40) | 12.67 (3.33) | 1.56 (-0.22 – 3.33) | 0.082 |

| Synthetic index 0-110* | 68.94 (21.50) | 75.39 (11.56) | 6.44 (-2.96 – 15.85) | 0.166 |

Range of scores: high scores indicate positive wellbeing

Discussion and conclusions

The availability of the two pharmacological treatments has changed the course of the disease (4, 5). Unfortunately, neither of these drugs cures IPF or completely arrests disease progression, and lung transplantation remains the only curative treatment for the small minority of patients who are eligible for this major intervention. In addition neither antifibrotic drug has convincingly demonstrated a positive effect on quality of life (25).

Because of the progressive nature of IPF and the absence of an effective medical therapy, it is essential to incorporate non pharmacological interventions into the treatment of IPF and the goals of managing IPF should include improving the quality of life (35).

Education and self-management are essential components to treating a patient with IPF. Specifically, by educating patients about IPF and the disease progression, it allows patients to set realistic goals, make meaningful choices, remain in control of their care, enjoy a higher quality of life, and prepare for the future. IPF support groups are excellent places for patients to learn about their disease as well as symptom management, though it is important that the facilitators and staff tailor the program to the IPF patient (36). The support group is also highly functional as it groups patients with similar experiences and concerns and enables them to provide emotional and moral support for one another (35). Support groups also provide an excellent opportunity for family involvement in the care of a person with IPF. Support groups in particular encourage the family planning the effective ways for providing care to the patient (37).

The specialist nurses are identified by the NICE guidelines as the central figures to provide information and support to patients and caregivers through the course of the illness (20). Also the patients identify the nurses as adequate and trusted figures to play this role (12). The specialist nurses can play an important role in managing symptoms like depression and anxiety; in fact, when they are closely involved in the patients’ disease path, it is easy for patients to talk to the nurse about their concerns and problems (26).

The PGWBI (Psychological General Well-Being Index) investigates six underdimensions of psychological well-being, which directly affects the quality of life: anxiety, depression, positivity, self control, general health and vitality. The PGWBI has proved to be appropriate in investigating the perception of the psychological well-being of patients and caregivers, to assessing the quality of life in IPF patients. In addition, the PGWBI is an appropriate tool for the purpose of the study, which it investigated the impact of the support groups on the psychological well-being and the quality of life associated with it.

The findings of this six months prospective pre-post study, show an increase in each dimension of the PGWBI scale. Even if the null hypothesis is accepted, the results suggest interesting direction for future research.

This pilot study has several limitations. First of all, the sample size of the study population is small; for this reason, aggregate data for patients and relatives have been used. Because the IPF is a rare condition, future researches require international and multicentre studies.

Second, the adoption of a properly matched control arm and randomisation would be needed to determine the real efficacy of the support groups. A larger randomised and multicentred study would allow a proper stratification of patients in order to seek how this intervention can impact different stages of severity in specific conditions. The advantage of exploring the effect of the support groups in people belonging to different cultural and social settings would also add significant strength to the results.

Despite the limitations, the study represents a step in the search for the effectiveness of support groups. In the absence of effective pharmacological treatments for healing, the support groups do not expose participants to risks or collateral effects, and they represent an opportunity for the wellbeing of the IPF patients and their caregivers.

References

- 1.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:788–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King TE, Jr, Pardo A, Selman M. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet. 2011;378:1949–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adamali HI, Anwar MS, Russell AM, Egan JJ. Non-pharmacological treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Curr Respir Care Rep. 2012;1:208–15. [Google Scholar]

- 4.King TE, Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2083–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richeldi L, Bois RM, Raghu G, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2071–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez FJ, Safrin S, Weycker D, et al. The clinical course of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:963–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-12_part_1-200506210-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vries J, Kessels BLJ, Drent M. Quality of life of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:954–61. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17509540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swigris JJ, Kuschner WG, Jacobs SS, Wilson SR, Gould MK. Health-related quality of life in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a systematic review. Thorax. 2005;60:588–94. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.035220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swigris JJ, Stewart AL, Wilson SR, Gould MK. Patients’ perspectives on how idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis affects the quality of their lives. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:61. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnan V, McCormack MC, Mathai SC, et al. Sleep quality and health-related quality of life in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2008;134:693–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mermigkis C, Stagaki E, Amfilochiou A, et al. Sleep quality and associated daytime consequences in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Med Princ Pract. 2009;18:10–5. doi: 10.1159/000163039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoenheit G, Becattelli I, Cohen AH. Linving with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an in-depth qualitative survey of European patients. Chron Respir Dis. 2011;8:225–31. doi: 10.1177/1479972311416382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giot C, Maronati M, Becattelli I, Schoenheit G. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: an EU patient perspective survey. Curr Respir Med Rev. 2013;9:112–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belkin A, Albright K, Swigris JJ. A qualitative study of informal caregivers’ perspectives on the effects of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2014;1:e000007. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2013-000007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duck A, Spencer LG, Bailey S, Leonard C, Ormes J, Caress AL. Perceptions, experiences and needs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71:1055–65. doi: 10.1111/jan.12587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sampson C, Gill BH, Harrison NK, Nelson A, Byrne A. The care needs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and their carers (CaNoPy): results of a qualitative study. BMC Pulm Med. 2015;15:155. doi: 10.1186/s12890-015-0145-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell AM, Swigris JJ. What’s it like to live with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? Ask the experts. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:1324–6. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00109-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Overgaard D, Kaldan G, Marsaa K, Nielsen TL, Shaker SB, Egerod I. The lived experience with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a qualitative study. Eur Respir J. 2016;4:1472–80. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01566-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindell KO, Olshansky E, Song MK, et al. Impact of a disease-management program on symptom burden and health-related quality of life in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and their care partners. Heart Lung. 2010;39:304–13. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Diagnosis and management of suspected idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. 2013. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/14183/64119/64119.pdf. [PubMed]

- 21.Ganster DC, Victor B. The impact of social support on mental and physical health. Br J Med Psychol. 1988;61:17–36. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1988.tb02763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nichols K, Jankinson J. Leading a support group. A practical guide. New York: Open University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryerson CJ, Berkeley L, Carrieri-Kohlman VL, Pantilat SZ, Landefeld CS, Collard HR. Depression and functional status are strongly associated with dyspnea in interstitial lung desease. Chest. 2011;139:609–16. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belkin A, Swigris JJ. Health-related quality of life in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: where are we now? Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19:474–9. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328363f479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manen MJ, Geelhoed JJ, Tak NC, Wijsenbeek MS. Optimizing quality of life in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2017;11:157–69. doi: 10.1177/1753465816686743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danoff SK, Schonhoft EH. Role of support measures and palliative care. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19:480–4. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328363f4cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Risendal BC, Dwyer A, Seidel RW, et al. Meeting the challenge of cancer survivorship in public health: results from the evaluation of the chronic disease self-management program for cancer survivors. Front Public Health. 2014;2:214. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dockham B, Schafenacker A, Yoon H, et al. Implementation of a psychoeducational program for cacer surviveros and famil caregivers at a cancer support community affiliate: a pilot effectiveness study. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39:169–80. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manen MJG, Spijker A, Tak N, et al. Patient and Partner “Empowerment” Program in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (PPEPP): improving quality of life in patients and their partners. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. 2016;109:S46. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonella F, Wijsenbeek M, Molina-Molina M, et al. European IPF Patient Charter: unmet needs and call to action for healthcare policymakers. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:597–606. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01204-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olson AL, Brown KK, Swigris JJ. Understanding and optimizing health-related quality of life and physical functional capacity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Patient Relat Outocome Meas. 2016;7:29–35. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S74857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wijsenbeek M, Manen M, Bonella F. New insights on patient-reported outcome measures in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: only promises? Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2016;22:434–41. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dupuy H. The Psychological General Well-Being (PGWB) Index. In: Wenger N, Mattson M, Furberg C, Elinson J. Assessment of quality of life in clinical trials of cardiovascular therapies. New York: Le Jacq Publishing, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research, Milan. [Quality of Life and Health State. Assessment tools]Qualità della vita e stato di salute. Strumenti di valutazione. 2005 Available from: http://crc.marionegri.it/qdv/index.php?page=pgwbi . [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spagnolo P, Tonelli R, Cocconcelli E, Stefani A, Richeldi L. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnostic pitfalls and therapeutic challenges. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2012;7:42. doi: 10.1186/2049-6958-7-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee JS, McLaughlin S, Collard HR. Comprehensive care of the patient with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2011;17:348–54. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328349721b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Egan JJ. Follow-up and non-pharmacological management of the idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patient. Eur Respir Rev. 2011;20:114–17. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00001811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]