Abstract

Background and aims: Clinical learning placements provide a real-world context where nursing students can acquire clinical skills and the attitudes that are the hallmark of the nursing profession. Nonetheless, nursing students often report dissatisfaction with their clinical placements. The aim of this study was to test a model of the relationship between student’s perceived respect, role uncertainty, staff support, and satisfaction with clinical practice. Method: A cross-sectional, descriptive survey was completed by 278 second- and third-year undergraduate nursing students. Specifically, we tested the moderating role of supportive staff and the mediating role of role uncertainty. Results: We found that lack of respect was positively related to role uncertainty, and this relationship was moderated by supportive staff, especially at lower levels. Also, role uncertainty was a mediator of the relationship between lack of respect and internship satisfaction; lack of respect increased role uncertainty, which in turn was related to minor satisfaction with clinical practice. Conclusion: This study explored the experience of nursing students during their clinical learning placements. Unhealthy placement environments, characterized by lack of respect, trust, and support increase nursing students’ psychosocial risks, thus reducing their satisfaction with their clinical placements. Due to the current global nursing shortage, our results may have important implications for graduate recruitment, retention of young nurses, and professional progression.

Keywords: clinical learning, nursing, respect, social relationships, student satisfaction

Introduction

The quality of clinical nursing education is strongly linked to the quality of the clinical experience within the university curricula (1). Clinical internship provides a real-world environment in which students can safely translate theoretical nursing knowledge into practical nursing care, while simultaneously developing the attitudes and skills that are essential to the profession (2, 3). Moreover, the acquisition of clinical knowledge empowers the professional-in-training to familiarize themselves with a specific area in which their nursing training has occurred (4).

Therefore, both clinical practice and learning experiences are linked to the students’ satisfaction with their placements (5, 6). Nonetheless, the literature suggests that the clinical environment within nursing education is frequently unsatisfying and may negatively influence students’ learning experiences (7), generating stress and anxiety (8-13). The clinical learning environment literature indicates that students (a) often feel ostracized, as though they are not members of the team, (b) that they lack support and constructive feedback, (c) and that they are scared of making errors that might impact the patients’ health (14-16). Furthermore, nursing students play a double role as both student and apprentice. This exposes them to compounding psychosocial risks (14). While a moderate amount of stress (i.e., eustress) might increase students’ motivation (17), the stresses on nursing students during their clinical training and practice needs to be better accounted for and managed, especially in light of the global nurse shortage.

A positive clinical learning environment fosters student progression and retention within the nursing education program, thus facilitating their learning and acquisition of their identity as a nurse (7, 18). Researchers found that the most important factors influencing satisfaction with clinical learning were: (i) exposure to hostile placement environments, (ii) good cooperation with other staff in the clinical ward, and (iii) considering student nurses in the interaction network as younger (i.e., future) colleagues (18-22). Other authors have shown that good interpersonal relationships among staff and nursing students, as well as mutual respect and support, are crucial for building positive learning contexts (23-25). Smedley (26) showed that nurturing positive relationships with clinical teaching staff was central in creating an ideal clinical setting for nursing students.

In addition, a positive clinical environment enables the development of both a concept of the professional role and professional identity of nursing students, thus reducing role uncertainty. Moreover, satisfaction with clinical learning experience is linked to the degree to which nursing students define, negotiate, and develop their role in the clinical environment. On the one hand, nursing students expect to be thought of as nursing students, not as aides in the clinical environment (27). On the other hand, nursing staff invariably consider students to be sometimes workers and at other times learners (28). Consequently, this disparity exposes students to a heightened risk for the development of role stress, particularly role uncertainty. Rudman and Gustavsson (29) suggest that the dualism inherent in being simultaneously a student and healthcare professional exposes nursing students to role uncertainty and role conflict (30-32). Accordingly, role ambiguity occurs when nursing students have unclear responsibilities and receive unclear information with regard the behavior expected of them in the student role (33, 34). Role conflict occurs when nursing students receive inconsistent and incompatible messages about their job obligations from two or more people (33). In general, role stress is the result of the discrepancy between a person’s perceptions of the defining features of their role (i.e., as nursing students) and their achievement in performing their specific role (35). In this sense, incongruence between perceived role expectations and role achievement generates role stress.

Bradbury-Jones et al. (36) argue that bullying and horizontal violence are characteristic of the culture of nursing, and that nursing students are not immune from the risks associated with this culture (37-39). In their study they found that nursing students experienced limited learning opportunities, a reduced sense of belonging, and lack of respect during their clinical placements (36). This finding is consistent with those of Castledine (40) who suggested that there is “much negativity and lack of respect for students when they enter clinical placements” (p. 1222). According to Yearwood and Riley (41), a supporting clinical environment is fundamental for enhancing students’ growth and development. Conversely, an unsupportive clinical environment exposes students to psychosocial risks, demotivation, and dissatisfaction. Recently, Onuoha, Prescott, and Daniel (42) found that being supported by registered nurses, receiving guidance, supervision and caring attitudes were important for the development of nursing students into confident and capable practitioners. Therefore, a clinical environment characterized by supportive nursing staff is crucial for empowering student learning in practice (43). Furthermore, an important resource for students is the establishment of a supportive climate between themselves and the nursing staff while on placement, especially other registered nurses and their tutor(s). Essentially, greater levels of social support during clinical practice are protective against placement stress. There is a wealth of evidence from the work stress literature to support the argument that a supportive environment is a fundamental job resource for promoting healthy workplaces (44). The buffering role of job resources is consistent with the Demand–Control Model (45) and the Effort–Reward Imbalance Model (46). Bakker, Demerouti, and Verbeke (46) assert that job resources, such as a supportive work environment, “has been proposed as a potential buffer against job stress” (p. 89). Therefore, the presence of a buffering variable can decrease the impact of organizational stressors on individual perceptions and cognitions, “moderate responses that follow the appraisal process, or reduce the health-damaging consequences of such responses” (47, 48).

Study aim

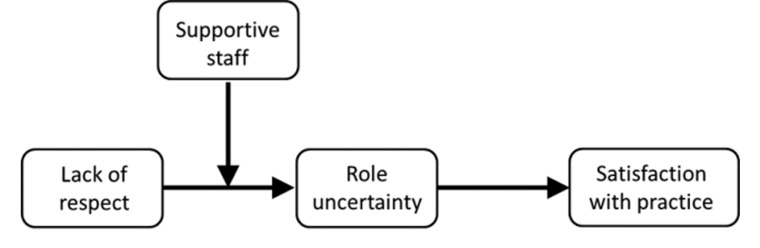

The aim of this study was twofold: (1) to test if role ambiguity mediates the relationship between lack of respect and satisfaction and (2) if the mediating effect of role ambiguity will be moderated by staff support, such that the mediated relationship will be stronger when students receive low staff support. Figure 1 depicts moderated mediation model proposed in the present study.

Figure 1.

Relationship between the study variables

Methods

Design and participants

A descriptive and cross-sectional analysis was carried out through an online self-reported questionnaire. A total of 278 second- and third-year undergraduate students enrolled at the Nursing Sciences course from one Italian University were involved in the study. First-year nursing students were not included in the study because they did not still start their internship yet.

Ethical consideration

The potential participants for this research were recruited through personal contacts of the authors. All participants received written information about the aims of the research and gave their verbal informed consent. Participation was voluntary, there was no adverse consequence of declining or withdrawing from participation, and confidentiality was protected since responses were kept anonymous. Participants received no incentive for their involvement.

Instrument

The questionnaire included a socio-demographic section and a set of validated scales from international literature. For the measures for which an Italian validation was not available, the translation-back-translation procedure (49) was performed. All the used scales included items that were rated using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Role uncertainty. Four items for the role ambiguity subscale and three items for role conflict from Rizzo et al. (33)’s scale were adapted for the study aim. Sample items were “I understood which were my responsibility as an intern” and “I worked on superfluous and unnecessary things”, respectively.

Lack of respect. It was measured by using three items adapted from the Reward Component Esteem Scale by Siegrist (46). A sample item was “In my ward nurses did not have an adequate respect of interns”.

Supportive staff. It was measured using items generated ad hoc for this study. A sample item was “In the ward, students were taken into great consideration”.

Satisfaction with clinical practice. We used three items adapted from Cortese (50). A sample item was “Globally, I feel satisfied with my internship experience”.

Data analysis strategy

All the analyses were carried out by using IBM SPSS 21. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with the maximum likelihood method of estimation was used for examining the structure of the measures, factor loadings and intercorrelations.

According to Kline (51), the following fit indices were used: Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). To indicate a good fit of the model, the TLI and CFI critical values should be ≥ .90, and RMSEA ≤.08 (51).

Moderated mediation analyses were executed on the Hayes’s (52) PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 7). We employed 10,000 bootstrap re-samples with bias-corrected and bias-accelerated 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Variables were centered before constructing the interaction terms to minimize multicollinearity. We plotted the moderation graph by dividing into two groups by one standard deviation below and one standard deviation above the mean.

Results

A total of 300 nursing students enrolled at the nursing sciences course from one Italian University were involved. Among these, 278 completed the questionnaire (response rate=92.7%). Regarding gender characteristics, 47.5% were males. The average age (53%) ranged from 20 to 23 years old. Means, standard deviations and correlations between variables are presented in Table 1. The Cronbach’s Alpha values for the measures are presented in the table, as well.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviation and correlations between study variables

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Role Uncertainty | 2.60 | 0.74 | (.77) | |||

| 2. Lack of Respect | 3.27 | 1.11 | -.19** | (.80) | ||

| 3. Supportive staff | 2.60 | 1.00 | -.60** | .36** | (.81) | |

| 4. Satisfaction with clinical practice | 3.50 | 0.85 | -.53** | .31** | .67** | (.78) |

Note. p<0.01. Cronbach’s Alpha values for each variable are reported in parenthesis

Factor structure analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was carried out to test the measurement model with four factors. The four-factor structure was compared with a one-factor model to assess the distinctiveness of the study variables. The results showed a good model fit (χ2 (df=97)=226.9, CFI=0.92, TLI=0.91, RMSEA=0.07). All the indicators loaded significantly on their reference constructs (p<0.001). The four-factor structure also improved significantly (p<.001) over the one-factor structure (χ2 (df=103)=600.3; CFI=0.714; TLI=0.66; RMSEA=0.13). The four-factor model was supported. Reliability analysis of measures showed good internal consistency (inter-item correlation in the same scale ranged from 0.70 to 0.91).

Moderated mediation analysis

In this analysis, we tested if the strength of the effect of lack of respect on satisfaction through role ambiguity depends on the level of staff support. Results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Regression analysis results

| Predictor | Role uncertainty | Satisfaction with practice | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| Lack of respect | .05 | .04 | .16** | .06 |

| Supportive staff | -.44** | -.04 | ||

| Lack of respect * Supportive staff | -.10** | .03 | ||

| Role uncertainty | -.56** | .06 | ||

| R2adj | .38 | .33 | ||

Note. p<0.01. B=Beta coefficient, SE=Standard error

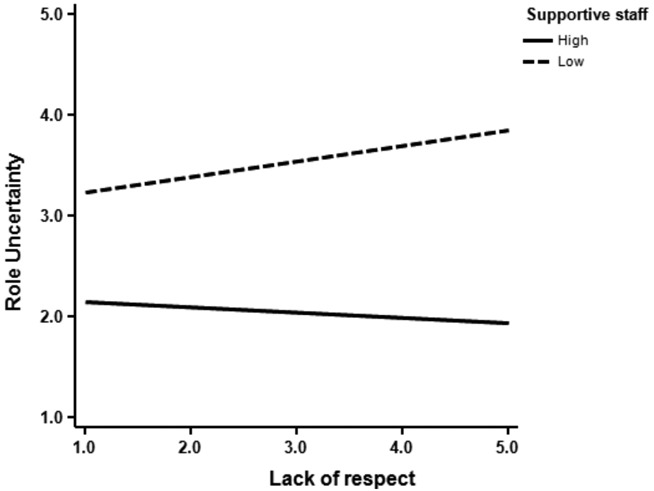

To test our hypothesis, the first condition was that the path between the independent variable (lack of respect) to the mediator (role uncertainty) should be moderated (supportive staff) (53). As seen in Table 2, the interaction between lack of respect and supportive staff was statistically significant (β=-0.10, p<0.01). The nature of the interaction was explored by calculating simple slopes at ±1 standard deviation of the moderator (Figure 2). The results showed that the lack of respect was related to role uncertainty for students with low levels of supportive staff (β=0.15, SE=0.06, p<0.01) but it was not significant for students with high levels of supportive staff (β=-0.05, SE=0.04, ns). The explained variance for the moderation model was 38%.

Figure 2.

Interaction between lack of respect and supportive staff predicting role uncertainty. The x- and y- axes reflect the Likert scale points of the measures

Next, we tested the conditional (moderated) indirect effect of lack of respect on satisfaction with clinical practice through the mediator (role uncertainty) at different levels of the moderator (supportive staff) (54). The estimates and bias-corrected bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals for the conditional indirect effects are presented in Table 3. The conditional indirect effect of lack of respect on satisfaction with clinical practice was significant when supportive staff was low (-1 SD): indirect effect=-0.09, SE=0.03, 95% CI [-.16, -.02]. The direct effect of lack of respect on satisfaction with clinical practice after controlling for role uncertainty (M), supportive staff (W) and the interaction M*W remained significant: direct effect=0.16, SE=0.04, pa<0.01

Table 3.

Conditional indirect effect of lack of respect on satisfaction with clinical practice at ±1 standard deviation of supportive staff

| Level of supportive staff | Satisfaction with clinical practice | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | 95% CI | |

| 1 SD | -0.09 | 0.03 | [-.16,-.02] |

| +1 SD | 0.03 | 0.02 | [-.01, .07] |

Note. 10,000 bootstrapped samples, B=Beta coefficient, SE=Standard error, 95% CI=Confidence Intervals. Boldface coefficients denote significance

Discussion

Building healthy and empowering work environments that attract and retain young nurses in the profession is essential for supporting the future of the nursing workforce, which is especially crucial in light of the aging workforce (55). The nursing literature contains a wealth of evidence attesting to how new graduate nurses report high levels of stress and burnout (56), which is harmful for workers’ health and well-being. Therefore, building positive clinical environments can potentially provide a more ideal professional development opportunity. Clearly, having positive attitudes to clinical learning is a prerequisite for continuing university studies and for fortifying the professional identity of future nurses.

Our study aimed to examine how work-related risk factors, such as a lack of respect and role uncertainty, impacts students’ satisfaction with their clinical learning experience. Additionally, we investigated how support from other nursing staff represents an important resource with the potential to mitigate the effect of these stressors on students’ well-being. Consequently, understanding and reducing the risk factors associated with nursing clinical practice has the potential to protect future nurses from occupational stress. Our results support that a clinical environment characterized by a lack respect for nursing students as a people is negatively linked to satisfaction with clinical learning (57-59). These findings are congruent with other international studies that highlight how respect (or the lack of it) for students is linked with student difficulties in overcoming the transition from university-based education to work-based practice (60-62). Furthermore, our study revealed that clinical environments characterized by a paucity of respect for students resulted in student role uncertainty subsequent and reduced satisfaction with clinical practice. Several studies have investigated the association between satisfaction with clinical learning experiences and student role uncertainty. In one such study, Wu and Norman (32) demonstrated how ambiguity in what students are required to do during their clinical placements acts as a source of role uncertainty. Therefore, our findings suggest that when students perceive being respected by placement staff (especially other nurses and tutors), this reduced students’ perceptions of role ambiguity, which in turn was linked to greater satisfaction with clinical practice.

Finally, as an extension of previous research, we found support for the buffering effect of supportive staff. Specifically, our results suggest that only when the clinical environment is characterized by a lack of supportive staff, that the impact of a lack of respect increased the perception of role uncertainty among nursing students, which in turn reduced their satisfaction with clinical practice. These findings are consistent with those of other studies highlighting the role of social supports in dealing with stressful environments (63).

Conclusions

While this study might make a valuable contribute to the growing body of knowledge pertaining to the well-being of nursing students, the study has several limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional nature of this study precluded the identification of causal relationships between variables. Secondly, respondents completed the questionnaires online. Online questionnaires do not provide any controls; as such, there is a potential for bias in terms of compliance and with the completion of questionnaires. Some questionnaires did not collect socio-demographic data, thus making difficult to identify the characteristics of respondents who did failed to complete some sections. Thirdly, we used a self-administered questionnaire, which suggests a risk for social desirability bias influencing students’ responses (64). Future studies should look to integrate perception data with objective data, such as performance assessment and/or measurements by nurse tutors. Finally, the study was performed in one university in Italy. Consequently, we were not able to compare the results against students from other universities, thus limiting the generalizability of the results. However, this study could be seen as a pilot, with future investigations designed to overcome the limitations of the current investigation.

The results of this study should be carefully considered against a backdrop of the current worldwide shortage of nurses (65, 66). According to Pearcey and Elliott (67), the success of nursing programs is strongly linked to the effectiveness of the clinical experience. Our findings support the argument that contemporary nursing education programs face a number of challenges. Some of these challenges may invariably prove stressful for students. Therefore, universities and hospitals should aim to deepen their collaboration, and look to investigate and understand the factors that facilitate effective learning in the clinical environment. Having a clearer and shared understanding of the role of the student nurse, in terms of duties and activities during clinical placements, would certainly provide a starting point in the establishment of a healthier learning environment.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the nursing students who participated in this study.

References

- 1.Perli S, Brugnolli A. Italian nursing students perception of their clinical learning environment as measured with the CLEI tool. Nurs Educ Today. 2009;29:886–890. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newton JM, Jolly BC, Ockerby CM, Cross WM. Clinical Learning Environment Inventory: factor analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:1371–1481. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Mara L, McDonald J, Gillespie M, Brown H, Miles L. Challenging clinical learning environments: Experiences of undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ Pract. 2014;14(2):208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Happel B. The importance of clinical experience for mental health nursing – part 1: undergraduate nursing students’ attitudes, preparedness and satisfaction. Int J Ment Health Nu. 2008;17:326–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards H, Smith S, Courtney M, Finlayson K, Chapman H. The impact of clinical placement location on nursing students’ competence and preparedness for practice. Nurs Educ Today. 2004;24:248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bos E, Alinaghizadeh H, Saarikoski M, Kaila P. Factors associated with student learning processes in primary health care units: A questionnaire study. Nurs Educ Today. 2015;35(1):170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levett-Jones T, Lathlean J. Belongingness: a prerequisite for nursing students’ clinical learning. Nurs Educ Pract. 2008;8:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlson S, Kotze WJ, van Rooyen D. Accompaniment needs of first year nursing students in the clinical learning environment. Curationis. 2003;26(2):30–39. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v26i2.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook LJ. Inviting teaching behaviors of clinical faculty and nursing students’ anxiety. J Nurs Educ. 2005;44:156–161. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20050401-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliott M. The clinical environment: A source of stress for undergraduate nurses. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2002;20(1):34–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayden-Miles M. Humor in clinical nursing education. J Nurs Educ. 2002;41:420–424. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20020901-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharif F, Masoumi S. A qualitative study of nursing student experiences of clinical practice. BMC Nurs. 2005;4:6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-4-6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shipton SP. The process of seeking stress-care: Coping as experienced by senior baccalaureate nursing students in response to appraised clinical stress. J Nurs Educ. 2002;41:243–256. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20020601-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Prato D, Bankert E, Grust P, Joseph J. Transforming nursing education: a review of stressors and strategies that support students’ professional socialization. J Adv Med Educ Practice. 2011;2:109–116. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S18359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahat G. Stress and coping: junior baccalaureate nursing students in clinical settings. Nurs Forum. 1998;33:11–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.1998.tb00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck D, Srivaska R. Perceived level and sources of stress in baccalaureate nursing students. J Nurs Educ. 1991;30:127–133. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19910301-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibbons C, Dempster M, Moutray M. Stress and eustress in nursing students. J Adv Nurs. 2007;61:282–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chesser-Smyth PA. The lived experiences of general student nurses on their first clinical placement: a phenomenological study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2005;5:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eick SA. A systematic review of placement-related attrition in nurse education. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(10):1299–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henderson A, Heel A, Twentyman M, Lloyd B. Pre-test and post-test evaluation of students’ perceptions of a collaborative clinical education model on the learning environment. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2006;23(4):8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papp I, Markkanen M, von Bonsdorff M. Clinical environment as a learning environment: student nurses’ perceptions concerning clinical learning experiences. Nurs Educ Today. 2003;23:262–268. doi: 10.1016/s0260-6917(02)00185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papastavrou E, Dimitriadou M, Tsangari H, Andreou C. Nursing students’ satisfaction of the clinical learning environment: a research study. BMC Nurs. 2016;15(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s12912-016-0164-4. doi:10.1186/s12912-016-0164-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunn SV, Hansford B. Undergraduate nursing students’ perceptions of their clinical learning environment. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25(6):1299–1306. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.19970251299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ralph E, Walker K, Wimmer R. Practicum and clinical experiences: postpracticum students’ views. J Nurs Educ. 2009;48(8):434–440. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20090518-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan DSK. Combining qualitative and quantitative methods in assessing hospital learning environments. Int J Nurs Stud. 2001;38:447–459. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(00)00082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smedley A. Improving learning in the clinical nursing environment: perceptions of senior Australian bachelor of nursing students. J Res Nurs. 2009;15(1):75–88. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atack L, Comacu M, Kenny R, LaBelle N, Miller D. Student and staff relationships in a clinical practice model: impact on learning. J Nurs Educ. 2000;39(9):387–392. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20001201-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polifroni EC, Packard SA, Shah HS, MacAvoy S. Activities and interactions of baccalaureate nursing students in clinical practica. J Prof Nurs. 1995;11(3):161–169. doi: 10.1016/s8755-7223(95)80115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudman A, Gustavsson JP. Burnout during nursing education predicts lower occupational preparedness and future clinical performance: a longitudinal study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(8):988–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melia KM. Student nurses’ construction of occupational socialisation. Sociol Health Illn. 1984;6(2):132–151. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep10778231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Messersmith A. Unpublished PhD thesis. Kansas: University of Kansas; 2008. Becoming a nurse: The role of communication in professional socialization. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu L, Norman IJ. An investigation of job satisfaction, organizational commitment and role conflict and ambiguity in a sample of Chinese undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2006;26(4):304–314. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rizzo J, House R, Lirtzman S. Role conflict and ambiguity in complex organizations. Admin Sci Quart. 1970;15:150–163. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Portoghese I, Galletta M, Sardu C, Mereu A, Contu P, Campagna M. Community of practice in healthcare: An investigation on nursing students’ perceived respect. Nurse Educ Pract 14. 2014;4:417–421. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lambert VA, Lambert CE. Literature review of role stress/strain on nurses: an international perspective. Nurs Health Sci. 2001;3(3):161–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2018.2001.00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradbury-jones C, Sambrook S, Irvine F. The meaning of empowerment for nursing students: A critical incident study. J Adv Nurs. 2007;59:342–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stevens S. Nursing workforce retention: challenging a bullying culture. Health Affair. 2002;21:189–193. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKenna B, Smith N, Poole S, Coverdale J. Horizontal violence: experiences of nurses in their first year of practice. J Adv Nurs. 2003;42:90–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Randle J. Bullying in the nursing profession. J Adv Nurs. 2003;43:395–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castledine G. Students must be treated better in clinical areas. Brit J Nurs. 2002;11:12–22. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2002.11.18.10570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yearwood E, Riley JB. Curriculum infusion to promote nursing student well-being. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(6):1356–1364. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Onuoha PC, Prescott Carter K, Daniel E. Factors associated with nursing students’ level of satisfaction during their clinical experiences at a major Caribbean hospital. Asian J Sci Technolog. 2016;7(5):2944–2954. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kevin J. Problems in the supervision and assessment of student nurses: can clinical placement be improved? Contemp Nurse. 2006;22:36–45. doi: 10.5172/conu.2006.22.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schaufeli WB, Taris TW. A critical review of the job demands-resources model: implications for improving work and health. In: GF Bauer, O Hämmig, Bridging occupational, organizational and public health: a transdisciplinary approach. Dordrecht: Springer Science Business Media, 2014: 43-68. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karasek R. Demand/Control Model: A social, emotional, and physiological approach to stress risk and acrive behaviour development. In JM Stellman (Ed.), Encyclopaedia of occupational health and safety. Geneva: International Labour Office; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psych. 1996;1:27–41. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.1.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kahn RL, Byosiere PB. Stress in organizations. In Dunnette MD, Hugh LM (eds.). Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Palo Alto, CA:Consulting Psychologists Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Demerouti E, Bakker AB. The job demands-resources model: Challenges for future research. SA J Ind Psychol. 2011;37(2):01–09. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1970;1:185–216. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cortese CG. Prima standardizzazione del Questionario per la Soddisfazione per il lavoro (QSO) [[First standardization of Job Satisfation Questionnaire (JSQ)]]. Risorsa Uomo. 2001;8:331–349. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modelling. 2nd edn) New York: The Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behav Res. 2007;42(1):185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Laschinger HKS, Fida R. New nurses burnout and workplace wellbeing: The influence of authentic leadership and psychological capital. Burn Res. 2014;1:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cho J, Laschinger HKS, Wong C. Workplace empowerment, work engagement and organizational commitment of new graduate nurses. Nurs Leadersh. 2006;19:43–60. doi: 10.12927/cjnl.2006.18368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Löfmark A, Wikblad K. Facilitating and obstructing factors for development of learning in clinical practice: a student perspective. J Adv Nurs. 2001;34(1):43–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.3411739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nolan CA. Learning on clinical placement: the experience of six Australian student nurses. Nurse Educ Today. 1998;18(8):622–629. doi: 10.1016/s0260-6917(98)80059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jokelainen M, Turunen H, Tossavainen K, Jamookeeah D, Coco K. A systematic review of mentoring nursing students in clinical placements. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:2854–2867. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seabrook MA. Clinical students’ initial reports of the educational climate in a single medical school. Med Educ. 2004;38(6):659–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seabrook M. Intimidation in medical education: Students’ and teachers’ perspectives. Stud Higher Educ. 2004;29:59–74. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gillespie M, McFetridge B. Nurse education–the role of the nurse teacher. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15(5):639–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schwarzer R, Knoll N. Functional roles of social support within the stress and coping process: A theoretical and empirical overview. Int J Psychol. 2007;42(4):243–252. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Podsakoff PM, Organ DW. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J Manage. 1986;12:531–544. [Google Scholar]

- 65.World Health Organization. The world health report – working together for health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aluttis C, Bishaw T, Frank MW. The workforce for health in a globalized context – global shortages and international migration. Glob Health Action. 2014;7 doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.23611. doi:10.3402/gha.v7.23611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pearcy PA, Elliot BE. Student impressions of clinical nursing. Nurs Educ Today. 2004;24:382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]