Abstract

Background: Negative interactions among nurses are well recognized and reported in scientific literature, even because the issues may have major consequences on professional and private lives of the victims. The aim of this paper is to detect specifically the prevalence of workplace incivility (WI), lateral violence (LV) and bullying among nurses. Furthermore, it addresses the potential related factors and their impact on the psychological and professional spheres of the victims.Methods: A review of the literature was performed through the research of papers on three databases: Medline, CINAHL, and Embase.Results: Seventy-nine original papers were included. WI has a range between 67.5% and 90.4% (if WI among peers, above 75%). LV has a prevalence ranging from 1% to 87.4%, while bullying prevalence varies between 2.4% and 81%. Physical and mental sequelae can affect up to 75% of the victims. The 10% of bullied nurses develop Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms. Bullying is a predictive factor for burnout (β=0.37 p<0.001) and shows a negative correlation with job efficiency (r=-0 322, p<0.01). Victims of bullying recorded absenteeism 1.5 times higher in comparison to non-victimized peers (95% CI: 1.3-1.7). 78.5% of bullied nurses with length of service lower than 5 years has resigned to move to other jobs.Conclusions: There is lack of evidence about policies and programmes to eradicate workplace incivility, lateral violence and bullying among nurses. Prevention of these matters should start from spreading information inside continue educational settings and university nursing courses.

Keywords: workplace incivility, lateral violence, bullying, nurses, prevalence, review

Background

Currently, negative relationships among nurses are an issue well-recognized worldwide and reported by the literature, even because this phenomenon can determine negative consequences for the professional and private lives of the victims.

A review performed by Spector et al. in 2014 (1), showed that on a total sample of 151307 nurses, derived from 136 studies, the 36.4% was exposed to physical violence (PV) and the 67.2% to the non-physical one (NPV). In Europe, there was an exposure of the 35% to PV and 59.5 % to NPV, the latest being usually perpetrated by other nurses or physicians (1).

In view of this evidence, this work focused on the three main forms with which dysfunctional interactions among nurses can occur: lateral violence, bullying and workplace incivility.

Lateral violence is as a subset of the global concept of ‘workplace violence’ (2), as well as bullying.

Since clear definitions and classifications of these antisocial behaviours at workplace are still lacking and sometimes debatable, epidemiologic comparisons between these issues can be problematic.

The most common manifestation of lateral violence is the psychological harassment resulting in hostility, as opposed to physical aggression.

These harassments include: verbal abuses, threats, humiliations, intimidations, criticism, innuendo, social and professional exclusion, discouragement, disinterest, and denied access to information (3).

Vice versa bullying has been described as an enduring offensive and insulting behaviour worsened by an intimidating, malicious, and insulting pattern (4).

This specific type of harassment amounts to power-abuse, while the victims experience feelings of humiliation, menace, vulnerability and distress (4).

A further distinction between bullying and lateral violence refers to their frequency of occurrence. Lateral violence can be isolated and sporadic while bullying is displayed when the negative acts are repeated weekly or more often, for six or more months (5).

In literature, many labels have been used to define workplace’s bullying. In Europe, the most common term for bullying is ‘mobbing’ (6).

The antecedents of these workplace’s deviant behaviours are related with a professional incivility attitude, described as deterioration in the workplace relationships among peers. For example: to leave a paper jammed printer unfixed, withholding important information, unauthorised use of victims’ personal items and, social exclusion.

Workplace incivility differs from (physical or verbal) workplace violence for its ambiguity in the intent to damage the victim (7). Therefore, workplace violence is displayed as soon as the intent of negative behaviours becomes clearly to harm the person (7).

The aim of this review is to highlight the extent of workplace incivility, lateral violence and bullying among nurses. Moreover, their related factors and the theoretical basis of their genesis are showed.

Methods

We performed a review of the available literature according to the following PECO: Population-Exposure-Comparison-Outcome.

‘Population’ is related to the nurse professional category. ‘Exposure’ is defined as experiencing incivility, lateral violence and, bullying. ‘Comparison’ is the act to evaluate the exposed and non-exposed subjects. ‘Outcome’ represents the negative collateral effects in private and professional lives of the targets.

Three different biomedical databases were investigated: Medline, CINAHL and Embase.

The keywords used for the research of papers were: “incivility”, “nursing”, “hostility”, “bullying”, “mobbing”, “lateral”, “horizontal”, “violence”.

The inclusion criteria settled for the research were: English-Italian language and human being subjects. None limitation of time was applied.

Google Search (provided by Google©) was also used in the process of gathering information, as an adjunct to the three databases explored (8).

The exclusion criteria were: studies on workplace violence against students and inside the academic settings, qualitative research studies, and all the secondary literature.

After the preliminary removal of double records and non-pertinent abstracts, we retrieved all the full-text articles matching the inclusion criteria (quantitative research studies, original mixed methods studies, systematic reviews and meta-analysis).

After the screening, seventy-nine original papers were selected.

Results

Workplace incivility: prevalence and related factors

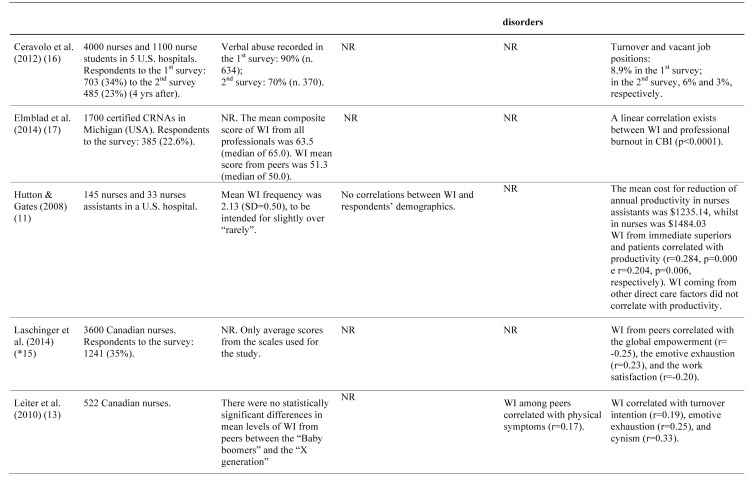

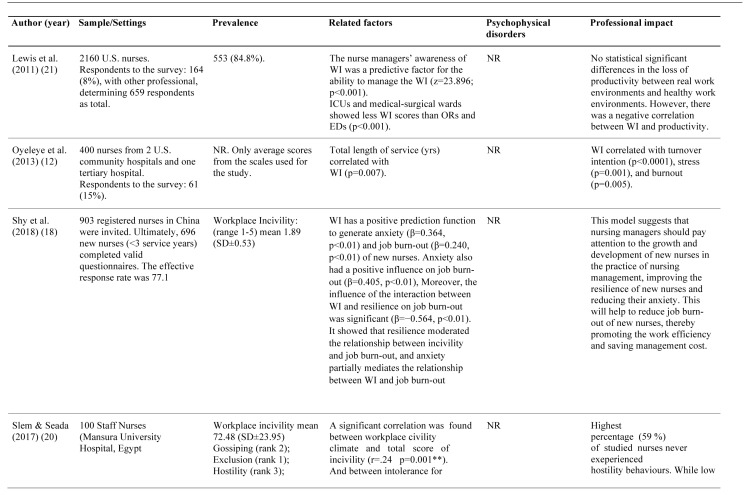

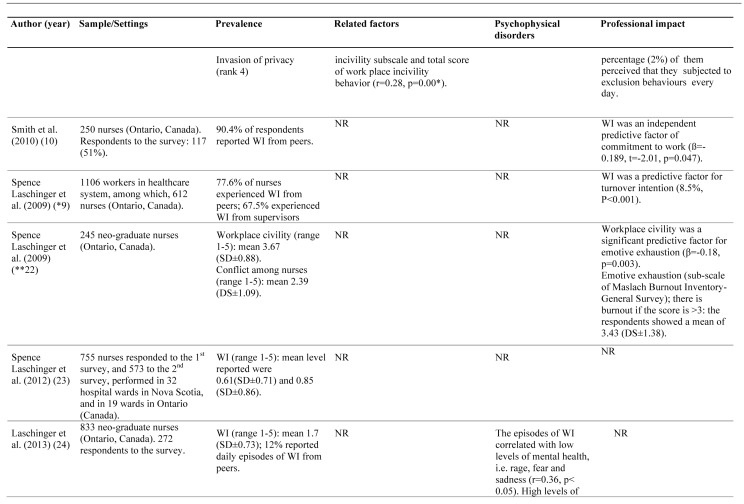

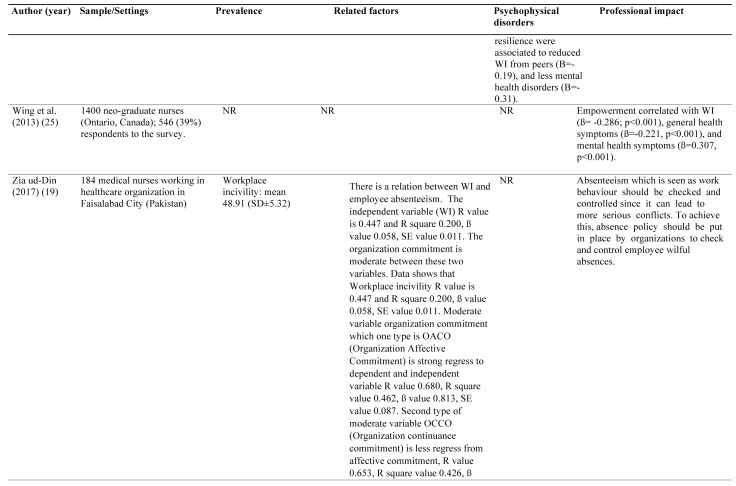

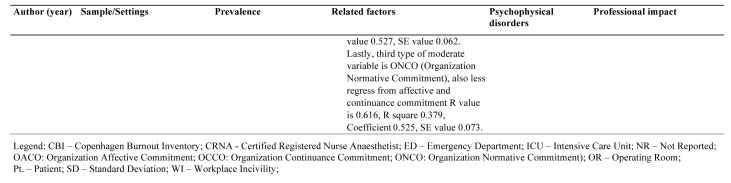

The number of papers focused on workplace incivility among nurses was 16 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Workplace incivility among nurses. Prevalence and consequences

Most of these original studies have been carried out in Canada and a minority in the USA.

Workplace incivility point prevalence and period prevalence are seldom investigated within the studies. Published studies mainly reported average values of specific scores as the Workplace Incivility Scale tool.

However, when reported, the overall percentage of workplace incivility still remains remarkable: between 67.5% (9), and 90.4% (10). Furthermore, workplace incivility among peers, account for values higher than 75% (9, 10).

According to the available data, there are no correlations of workplace incivility with specific demographic features (11), except for the total years of nursing job’s experience (p=0.007) as reported by Oyeleye et al. (12).

Concerning emotional and physical side effects, there is a weak correlation between workplace incivility among peers and physical symptoms (13).

Laschinger et al., highlighted how a strong resilience attitude was related with less presence of incivility among colleagues (B=-0.19), and less symptoms of mental discomfort (B=-0.31) (14).

Workplace incivility have a significative correlation with professional burnout (p<0.0001) (17), emotional exhaustion (r=0.25), cynicism (r=0.33) (12)and poor job’s satisfaction (r=-0.20) (15).

Several studies also related workplace incivility with the request of turnover (8.9%) (16)and turnover intentions (9, 12, 13), and with nurses’ job commitment, especially if the workplace incivility arose from patients or superiors (11).

Shi el al. (18) found that workplace incivility was positively related to anxiety (r=0.371, p<0.01) and job burn-out (r=0.238, p<0.01). On the contrary, workplace incivility was negatively related to resilience (r=−0.191, p<0.01) and has a positive prediction function to generate anxiety (β=0.364, p<0.01, M2) and job burn-out (β=0.240, p<0.01, M5) of new nurses. The resilience moderated the relationship between workplace incivility and job burn-out.

Zia-ud-Din Arif & Shabbir (19) found a significant relationship between workplace incivility and employee absenteeism (β=0.058, SE value 0.011), but with varying degrees to the facts of employee absenteeism. Among absenteeism, withdrawal behaviours was found to be the most prevalent practice of nurses as response to incivility. Organization commitment was negatively correlated with employee absenteeism and workplace incivility. The relationship was found to be negative between organization commitment and workplace incivility.

Slem & Seada (20) revealed a statistical significant negative correlation between workplace civility climate and total score of incivility behaviour while there was no significant correlation between group norms and workplace incivility behaviours among staff nurses. Findings suggest that perceived workplace civility climate can play a role in the incidence of incivility behaviours among staff nurses, while group norms for civility is not a predictor of occurrence of incivility behaviours.

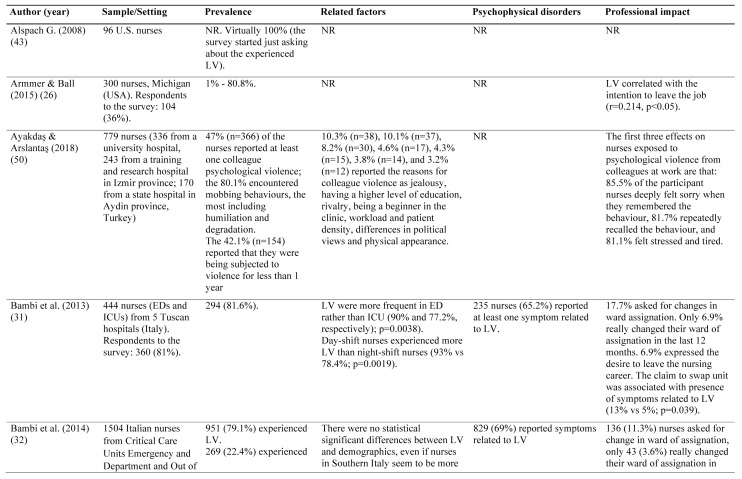

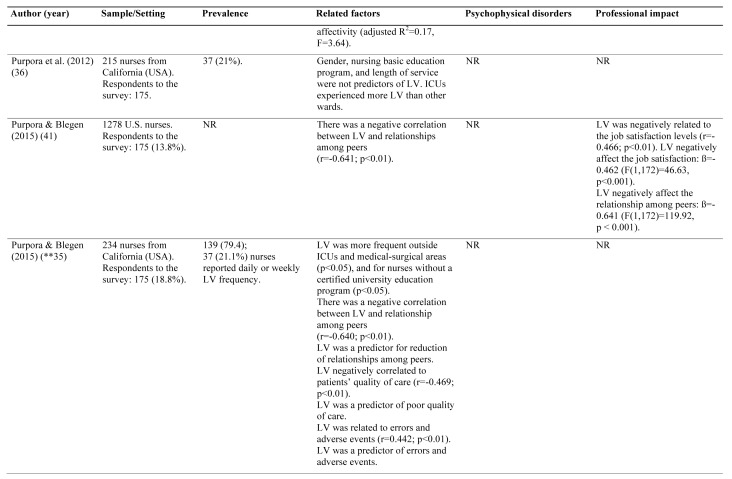

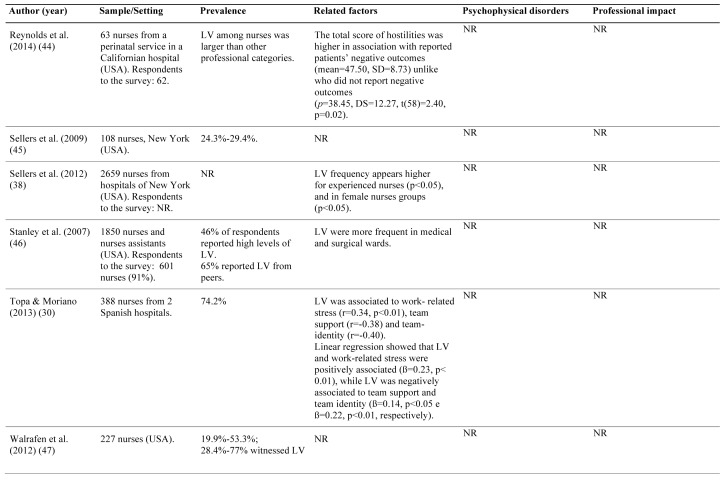

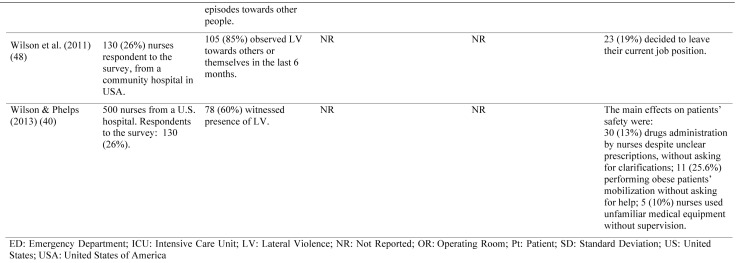

Lateral violence: prevalence and related factors

The number of papers on lateral violence matching the inclusion criteria was 25. This topic, compared to the previous one, seems to be more globally widespread than just the Northern America area. In fact, there is a greater variability in its prevalence, according to the studies reported (Table 2).

Table 2.

Lateral violence among nurses. Prevalence and consequences

The prevalence range is wide: from the 1% of Armmer & Ball (26), up to 87.4% described by Dunn on a population of operating room (OR) nurses (both from USA) (27). The European area shows a lower range of lateral violence (1.3%-5.3%), as recorded by the NEXT study (28).

Similar findings were reported from Italy, by Magnavita et al., showing a 9.9% of non-physical aggressions from colleagues (29).

Some exceptions were represented by a Spanish study (74.2%) (30)and two recent Italian surveys performed in Emergency and Intensive Care Unit (ICU) settings, showing values of 81.6% (31) and 79.1% (32), respectively.

Morrison et al. (49), in Jamaica, found that exposure to lateral violence was reported by 96% of participants, and 3/4 rated the exposure as moderate to severe. Lateral violence created a hostile environment, and the behaviours in response to lateral violence among nurses included professional disengagement, retaliation, avoidance and intent to resign, as indicated by half of the nurses surveyed. The Nurse Managers were the main perpetrators of lateral violence (63%). The pervasiveness of lateral violence among the nurses studied indicates the need to implement appropriate workplace violence policies.

Ayakdaş & Arslantaş (50), in Turkey, found that 47% (n=366) of nurses had suffered lateral violence and the 80.1% encountered mobbing behaviors, including humiliation and degradation. The reasons for colleague violence reported were: for the 10.3% the jealousy, for the 10.1% to have higher level of education, for the 8.2% the rivalry, for the 4.6% to be a beginner in the clinic, for the 4.3% the workload and the patient density, for the 3.8% the differences in political views, and for 3.2% the physical appearance.

Identification of specific services or units at high-risk of lateral violence can be difficult due to the broad variability inside the explored settings, confirming that lateral violence is firstly a “cultural problem” in nursing profession (33).

According to the NEXT study, intensive care units and operating rooms were the most affected areas by lateral violence (7.4%), followed by the elderly care units (7.0%) (28). In addition, an Italian survey showed the ORs as the most exposed environments to lateral violence (32).

As opposed, data collected in South Africa have identified obstetrics wards as the most affected service (40%) (34).

Finally, a survey from Purpora & Beglen (2015) pointed out that ICUs and surgical wards were the most affected by lateral violence (35).

Overall, gender, age, seniority and nursing education are not related factors of lateral violence among nurses in clinical settings (27, 31, 32, 36, 37).

The only exception is from the study of Sellers et al. (38). The authors have shown higher lateral violence rates among the senior versus junior nurses (p<0.05), as well as female versus male (p<0.05) (38).

Nurses working with daily shift are the most affected by lateral violence (28, 31).

Natural tendency for selfishness (β=0.13) and not yet specified peculiar work environment (β=0.13), both represent antecedents for work related bullying (39).

Nurses involved in lateral violence experience reported psycho-physical consequences on a range from 3.2% (29) to 65.2% (31). The symptoms’ description is summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Mild negative correlations exist between lateral violence and quality of patients care (r=-0.469; p<0.01), plus errors and adverse events (r=0.442; p<0.01) (35).

Authors reported that variable percentages of nurses victimized by lateral violence performed their duties not matching the minimum safety requirements. Some examples are: drugs administration with unclear prescription, lifting patients without support and using medical devices without asking for supervision (40).

Furthermore, there is a significant positive correlation between lateral violence and work-related stress (β=0.23, p< 0.01) (30).

In addition of these data, lateral violence exerts a negative impact on job’s satisfaction (β=-0.462; F (1,172)=46.63, p<0.001) (41).

At last, literature pointed out the link between lateral violence and the intent to quit from nursing career (r=0.214, p<0.05) (26). A range from 11.3% (31)to 30.5% (29) of nurses victimized, decided to resign from their position. From 6.9% (31) up to 34% (3) of the targets even consider quitting the profession.

Nurses that have witnessed lateral violence report and share the experience with other people up to 58% (40) of the episodes (recipients are line managers, peers, friends, relatives...).

On the contrary, a direct facing with the aggressor appears to have a broad range of percentage: from 17.3% (36) to 100% (42).

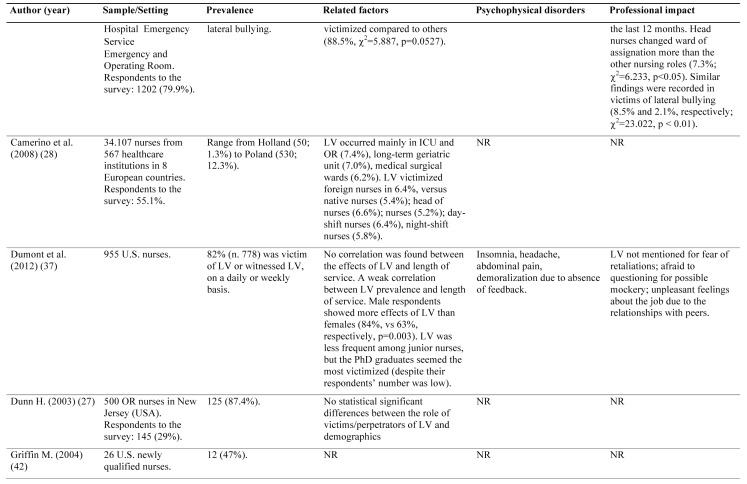

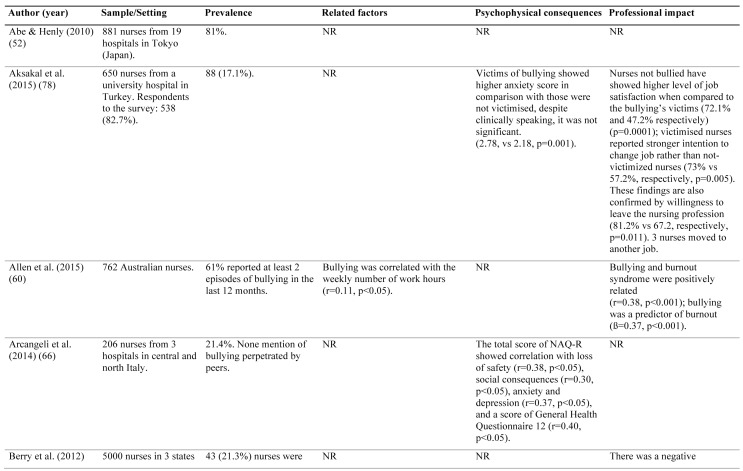

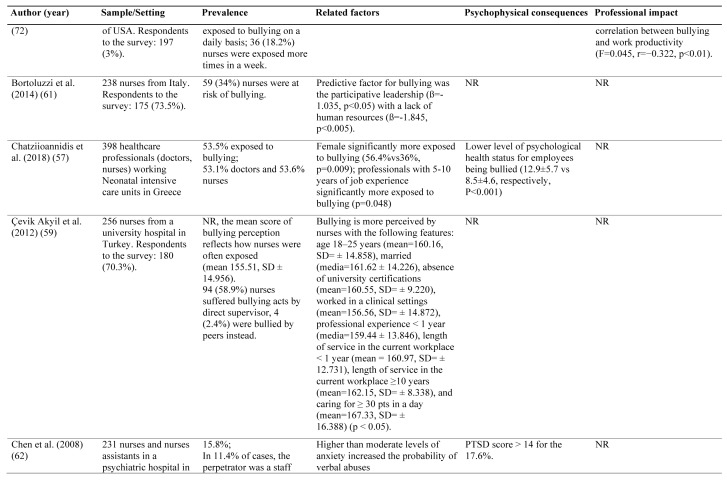

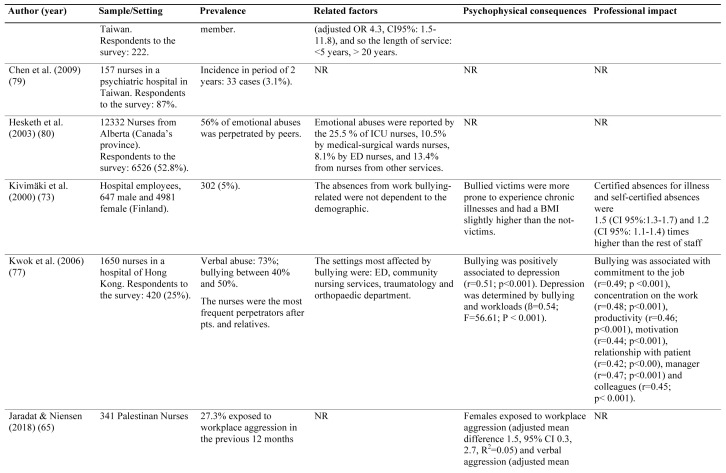

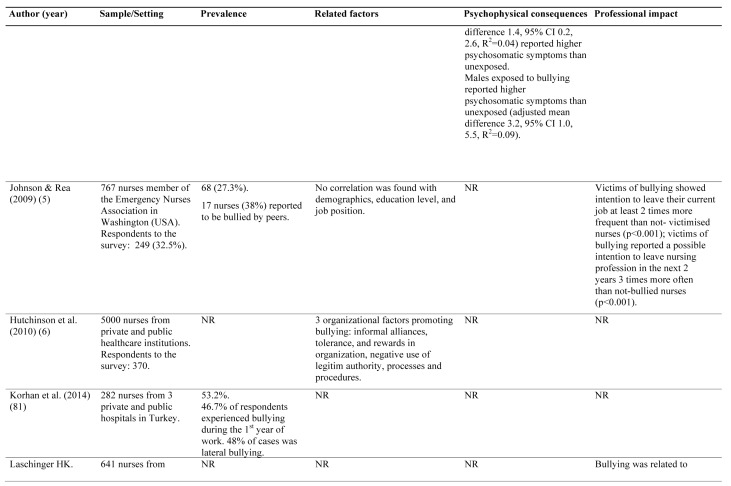

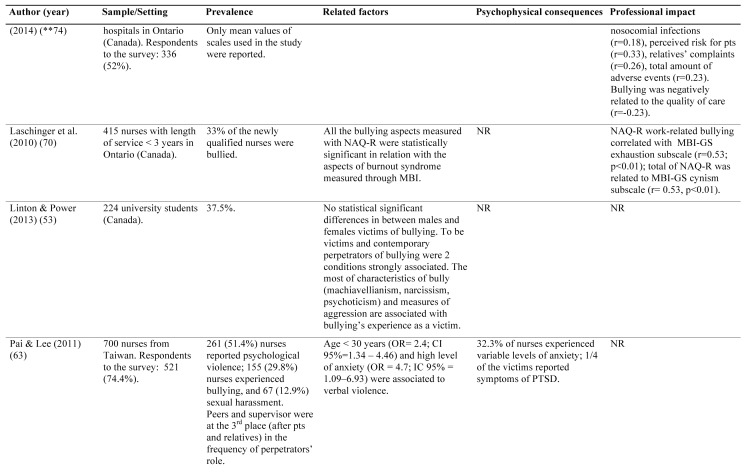

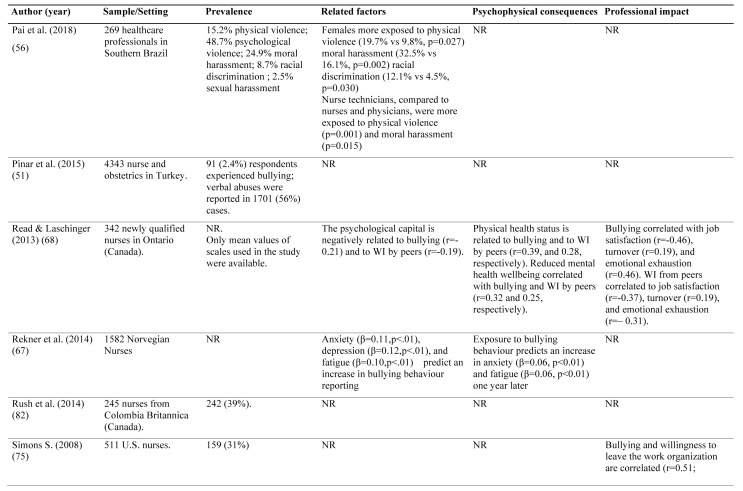

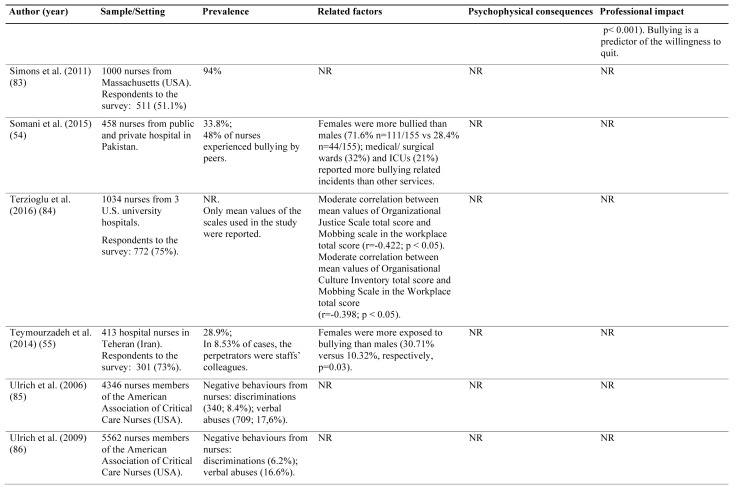

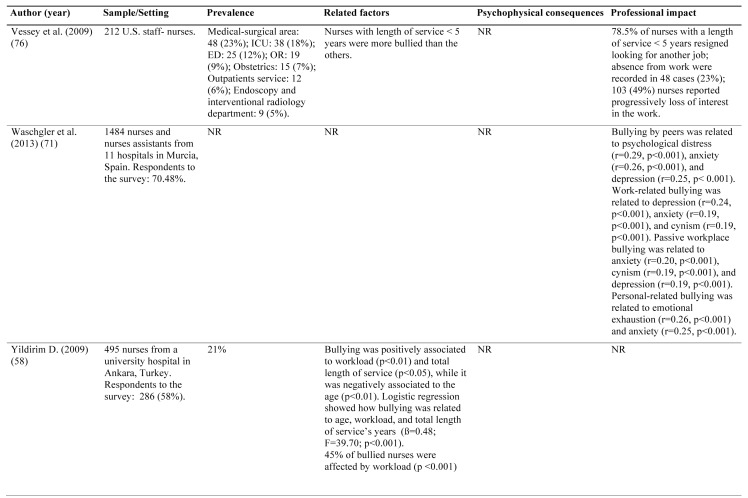

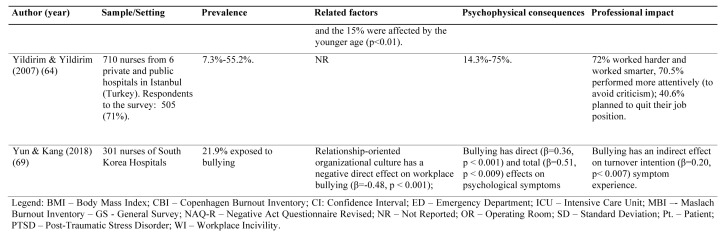

Bullying. Prevalence and related factors

The number of papers focused on bullying among nurses was 38 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Bullying among nurses. Prevalence and consequences

The prevalence reported also for this topic is widely variable, from 2.4% (51) to 81% (52).

Unlike the lateral violence, the variability of prevalence recorded in the studies on bullying, is mainly connected to its operational definition, then to studied settings and instruments used to record this phenomenon.

Bullying (as lateral violence) is not related to specific demographic factors, levels of education and nurses’ job position (5, 53).

Exceptions are given by data retrieved from Pakistan (54) and Iran (55).

Findings have shown that female nurses are significantly more prone to experience abuses, if compared to the male colleagues (56).

In Turkey, Yildirim (58) and Çevik Akyil et al. (59), have identified the younger age as a main risk factor for bullying in nursing profession (58). In a study conducted in Neonatal Intensive Care Units in Greece, the female professionals and those with a job experience ranging from 5 to 10 years were more exposed to bullying (57).

Vessey et al. showed that a length of service of less than five years was a risk factor for bullying (76). A mild positive correlation has been found between bullying and the amount of work hours per week (r=0.11, p<0.05) (60). Moreover, the perception of inclusive leadership or understaffing represent items in the predictive modelling for bullying (61).

Moderate to high levels of anxiety represent a risk factor as well, (adjusted OR 4.3, IC95%: 1.5-11.8) (62). This finding is also upheld by Pai & Lee (OR=4.7; IC 95%=1.09–6.93) (63).

Negative psychophysical outcomes of bullying can affect up to 75% of the victims (64).

Jaradat & Niensen (65) found that female and male nurses exposed to workplace aggression and bullying reported higher mean levels of psychosomatic symptoms than unexposed (respectively adjusted mean difference 1.5, 95% CI 0.3, 2.7, R2=0.05, and adjusted mean difference 3.2, 95% CI 1.0, 5.5, R2=0.09).

The nurses targeted by bullying have shown moderate correlation for loss of confidence (r=0.38, p<0.05), social consequences (r=0.30, p<0.05), depression-anxiety (r=0.37, p<0.05), and a general deterioration of the wellness status in accordance to the General Health Questionnaire 12 (r=0.40, p<0.05) (66).

Also Reknes et al (67), showed through a longitudinal study, that nurses exposed to bullying behaviour at T1 evaluation reported one year later increased symptom of anxiety (β=0.06, p<.01) and fatigue (β=0.06, p<.01) even when controlling for age, gender, night work, job demands. This study also remarked the presence of a vicious cycle causing nurses with higher anxiety (β=0.11, p<.01), depression (β=0.12, p<.01), and fatigue (β=.10, p<.01) at T1 evaluation, to report more bullying behaviour.

Chen et al., reported levels of symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) even higher than 14 in 17.6%, recognizing that 10% of that sample unfortunately developed this syndrome (62).

Different authors have found a direct correlation between bullying among peers and physical health status (r=0.39), likewise the mental health status (r=0.32) (68).

In a recent study (69), bullying showed a direct effect on the arise of psychological symptom in nurses (β=0.36, p<.001) and an indirect effect through the reported symptom on turnover intention (β=0.20, p<0.007).

Allen et al. (60) found that bullying is a predictive factor for the burnout syndrome (β=0.37, p<0.001), as also reported by Laschinger et al. (70) and by Waschgler et al. (71). Moreover there is a negative correlation between bullying and work productivity (F=0.045, r=−0.322, p<0.01) (72).

Nevertheless, Kiwimaki et al. (73) showed how targets of bullying usually tend to collect sick absence from the workplace more than the average staff’s trend: 1.5 (IC 95%: 1.3-1.7) times, 1.2 times (IC 95%: 1.1-1.4), respectively.

Laschinger (74). found a negative correlation between bullying and the quality of delivered nursing care delivered (r=-0.23). Findings reported a correlation with hospital-acquired infections (r=0.18), perception of patients’ safety risk (r=0.33), relatives’ complaints (r=0.26), and overall adverse events (r=0.23).

Unsurprising, increasing of bullying experience directly influences the targets’ intention to quit from their job position (r=0.51; p<0.001) (75), also because there is a negative correlation with the job satisfaction (r=-0.46) (68).

A survey performed in Turkey (64). showed a percentage up to 40.6% (in the sample of population investigated) of nurses planning resignation due to bullying. In addition, data from Vessey et al. (76) lead us to a concerning scenario: the 78.5% of nurses with a seniority less than 5 years, left their position for different careers.

Finally, a percentage from 25% (61) to 82% (77), put in practice different countermeasures to cope with the bullying experienced. Strategies were (64): sharing the experience with significant others or other professionals/institutions, reporting the episodes to line managers, and to face directly the bully (67.3%).

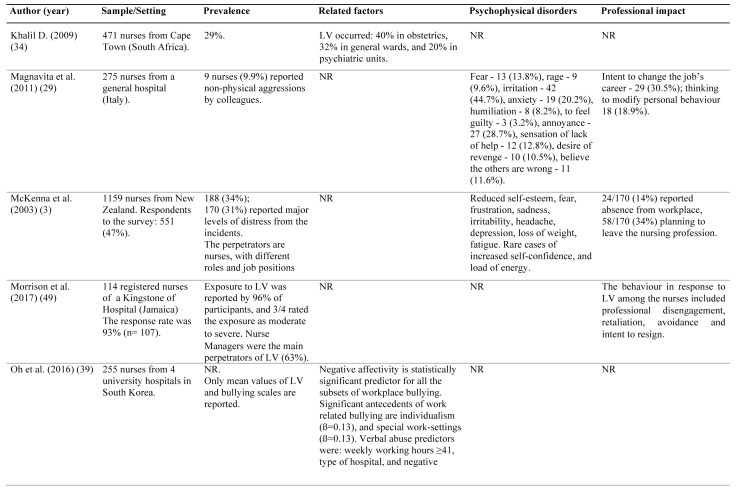

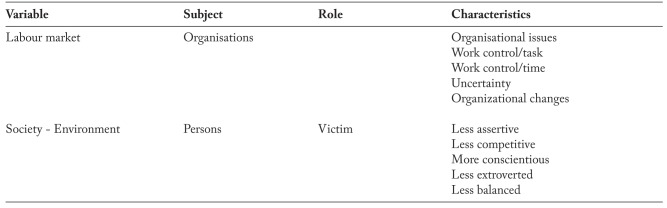

Risk factors

Several authors state that there are two different variables bringing the risk of bullying and negative behaviours in the workplace (Table 4). First is the job market’s fluctuation (local or global), forcing professionals to endlessly careers’ changes. The second is represented by the social environment, where people according to their background and resources are coping-reacting against problems or conflicts (87). This assumption appears to be valid for both, targets and perpetrators.

Table 4.

A quality analysis of incident reports related to working incivility and violence among healthcare professionals has identified two main factors as possible catalysts for their occurrence: behaviour at work and job planning.

The first factor includes unprofessional conducts, arguments about tasks, and disagreement on the nursing care strategy plus disappointment on peers job performance. The second one includes possible conflicts and aggressions due to a failure in the adherence to protocols, right assignation of patients, limited resources, and high levels of nursing workload (89).

Bullying seems to be more expected in clinical environments with high technical skills demands instead of clinical areas where relationships are the predominant nursing activities (76).

In nursing settings, the bullying attitude seems to be a consequence of previous learning of negative behaviours (a sort of ‘imprinting’), a deviant attitude acquired from the professional pack and the existing social environment (90).

Nonetheless, different authors spotted that perpetrators of bullying acts, forcing to conceal themselves a poor self-esteem, lack of social competence, useless leadership plus self-promotion micro-politics, because they are craving career progression (91). Others distinctive features of bullies are their narcissistic personality, a sense for revenge, tyranny plus a bad habit to spread accusation and rage over the people (91).

Often, the abuses instigators are prone to forgive themselves, assuming their misconduct is free of risks or collateral effects (92).

Finally, there is an escalation of bullying frequency in published literature due to a boosted clinical complexity of patients, spending review of budgets (less resources) along with a mounting workforce turnover (91).

Getting into the details, research from the United States of America have shown how the junior staff nurses category, especially the more youth, are at highest risks for bullying. It could be related to their lacking job experience, less confidence in their fresh job role and a scarce awareness of the unspoken rules inside the work environment (when compared to senior staff) (91).

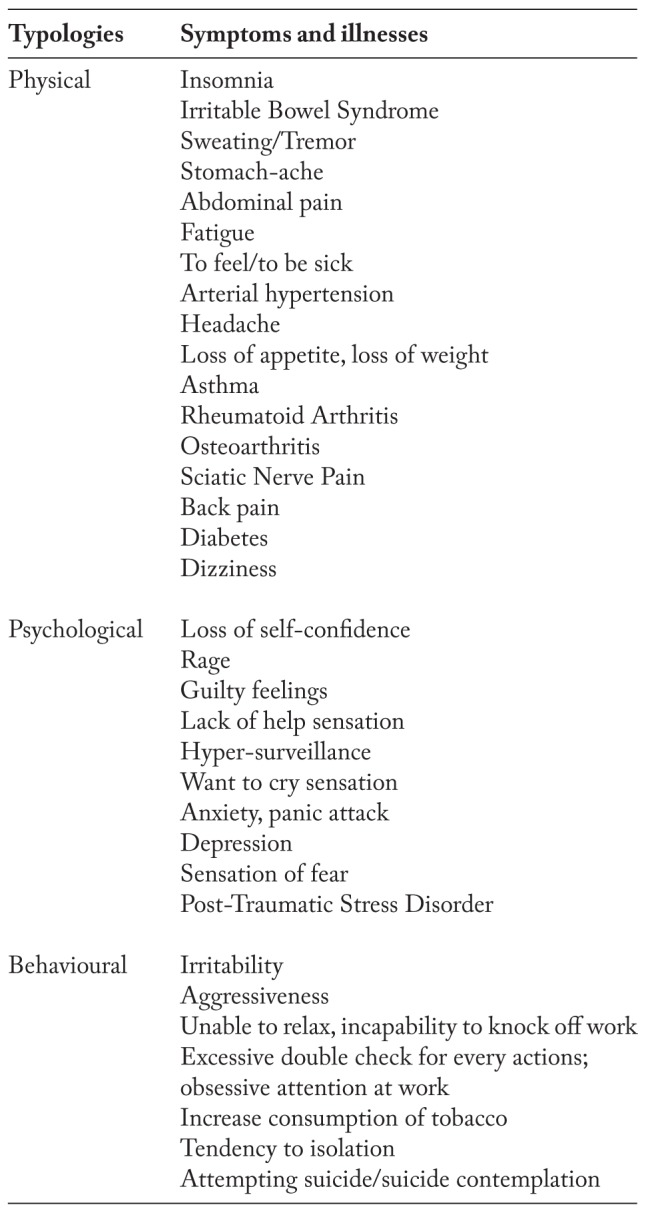

Psychological and physical impact

A systematic review of the literature classified the bullying effects on the victims according to several categories (87):

Decreased self-confidence

High levels of stress

Poor job satisfaction

Overreaction to mental stress

Psychological symptoms

Certified sick leave

Self-certified sick leave

Cardiovascular disease

Psychosomatic disorders

Chronic illness

The values of percentages reported about nurses’ physical and psychological health status, are widely variable (i.e. 12%-75%) (93).

Table 5 summarises the category of symptoms and disorders bullying related, according to the consulted literature.

Conclusions

The scientific literature covers a wide range of prevalence of workplace incivility, lateral violence and bullying in nursing.

Multiple reasons could be the explanation behind so many differences. For example, a workplace context based on various ‘in-groups’, sometimes quite dissimilar within same place or unit. Also the differences in the used measuring tool should be taken in account, because its features may directly influence the detection of lateral violence and bullying episodes and their frequencies as well. Even the operational definitions of these cases are subjects to this methodology’s choice.

A clear exemplification of this issue is the bullying/mobbing definition itself: “at least one negative act, weekly or more often, for six or more months” (95)or, according to other authors, “at least of two typologies of abuses, weekly or more often, for six or more months” (96).

Finally, the complexity in the data collection process retrieved from summarising tables was a challenge, due to the ambiguity of terminology (as already mentioned) plus the heterogeneity of tools employed. To rule out between workplace incivility, lateral violence and bullying-mobbing sometimes was quite difficult.

However, this review showed that workplace incivility, lateral violence and bullying are widespread in the clinical settings of nursing profession, and also that the consequences of lateral violence and bullying can be serious for the victims and the organizations.

Psychophysical symptoms and increasing of nurses’ turnover are the major expressions of these consequences.

Because the emotional and physical impact on victims cannot be neglected and the amount of people having the intention to leave the profession is alarming, the prevention becomes a priority.

So far, the strategies implemented were: get better awareness of the issue between peers and managers, the promotion of educational campaign for prevention, to provide personal resources to handle conflicts and improve communication’s skills, supporting authentic leadership practices and zero-tolerance policy against abuses (97).

Unfortunately, we observe a systematic response from the nursing management not fully supported by scientific evidence, plus the failure of zero-tolerance and informative policies is well recognized (98).

Definitive solutions for this matter, mainly based on the complexity of the humans’ social interaction, are not at fingertips. However, because its nature, a cultural-based response could be a possible approach.

It should start from the nursing academic education (basic and advanced), throughout workplace environments, becoming part of the continued education programs in the arrangement of ‘raising awareness’ dedicated events. At the same time, a call for action to isolate and to contain any workplace incivility or violence should be promoted.

As an adjunct to these interventions, an official stance from the nurse management and leaders would be desirable, in synergy with a systematic monitoring of these phenomena by occupational health departments.

In summary, we found a lack of evidence about policies and programmes to eradicate bullying and lateral violence. Prevention of these phenomena should start from a widespread information inside continue educational events and the university nursing courses.

Key points

- Workplace incivility, lateral violence and bullying are described as a continuum related to their intensity, frequency and presence of intention to harm the target.

- Prevalence of these phenomena in the nursing profession is variable, reaching considerable values (87% for lateral violence, 81% for bullying).

- In terms of emotional and physical impact, negative outcomes can seriously affect the victims (up to 75% of cases). A wide range of physical and psychological symptoms may occur.

- Two main factors were identified as possible catalysts with their occurrence: behaviour at work and job planning.

References

- 1.Spector PE, Zhou ZE, Che XX. Nurse exposure to physical and nonphysical violence, bullying, and sexual harassment: a quantitative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(1):72–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rumsey M, Foley E, Harrigan R on behalf of Royal College of Nursing, Australia. [Access made on 04-10-2011];National Overview of Violence in the Workplace. http://www.smspsts.org/smspsts/papers/australian%20overview.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKenna BG, Smith NA, Poole SJ, Coverdale JH. Horizontal violence: experiences of Registered Nurses in their first year of practice. J Adv Nurs. 2003;42:90–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishmael A, Alemoru B. Harassment, bullying and violence at work: a practical guide to combating employee abuse (employment matters) London: Spiro; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson SL, Rea RE. Workplace bullying: concerns for nurse leaders. J Nurs Adm. 2009;39:84–90. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e318195a5fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hutchinson M, Wilkes L, Jackson D, Vickers MH. Integrating individual, work group and organizational factors: testing a multidimensional model of bullying in the nursing workplace. J Nurs Manag. 2010;18:173–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hutton SA. Workplace incivility: State of the science. J Nurs Adm. 2006;36:22–7. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Il pensiero scientifico editore. [Access made on 18-09-2011];Come usare meglio Google [Scientific publishing. How to use Google better] 7. http://www.pensiero.it/strumenti/pdf/Google_Scheda_7.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spence Laschinger HK, Leiter M, Day A, Gilin D. Workplace empowerment, incivility, and burnout: impact on staff nurse recruitment and retention outcomes. J Nurs Manag. 2009;17:302–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith LM, Andrusyszyn MA, Spence Laschinger HK. Effects of workplace incivility and empowerment on newly-graduated nurses’ organizational commitment. J Nurs Manag. 2010;18:1004–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutton S, Gates D. Workplace incivility and productivity losses among direct care staff. AAOHN J. 2008;56:168–75. doi: 10.3928/08910162-20080401-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oyeleye O, Hanson P, O’Connor N, Dunn D. Relationship of workplace incivility, stress, and burnout on nurses’ turnover intentions and psychological empowerment. J Nurs Adm. 2013;43:536–42. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3182a3e8c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leiter MP, Price SL, Spence Laschinger HK. Generational differences in distress, attitudes and incivility among nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2010;18:970–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laschinger HK, Wong C, Regan S, Young-Ritchie C, Bushell P. Workplace incivility and new graduate nurses’ mental health: the protective role of resiliency. J Nurs Adm. 2013;43:415–21. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31829d61c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laschinger HK, Wong CA, Cummings GG, Grau AL. Resonant leadership and workplace empowerment: the value of positive organizational cultures in reducing workplace incivility. Nurs Econ. 2014;32:5–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ceravolo DJ, Schwartz DG, Foltz-Ramos KM, Castner J. Strengthening communication to overcome lateral violence. J Nurs Manag. 2012;20:599–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elmblad R, Kodjebacheva G, Lebeck L. Workplace incivility affecting CRNAs: a study of prevalence, severity, and consequences with proposed interventions. AANA J. 2014;82:437–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi Y, Guo H, Zhang S, et al. Impact of workplace incivility against new nurses on job burn-out: a cross-sectional study in China. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e02046. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zia-ud-Din M, Arif A, Shabbir M A. The Impact of Workplace Incivility on Employee Absenteeism and Organization Commitment. IJ-ARBSS. 2017;7(5):205–221. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sleem WF, Seada AM. Role of Workplace Civility Climate and Workgroup Norms on Incidence of Incivility Behaviour among Staff Nurses. IJND. 2017;7(06):34–44. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis PS, Malecha A. The impact of workplace incivility on the work environment, manager skill, and productivity. J Nurs Adm. 2011;41:41–7. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3182002a4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spence Laschinger HK, Finegan J, Wilk P. New graduate burnout: the impact of professional practice environment, workplace civility, and empowerment. Nurs Econ. 2009;27:377–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spence Laschinger HK, Leiter MP, Day A, Gilin-Oore D, Mackinnon SP. Building empowering work environments that foster civility and organizational trust: testing an intervention. Nurs Res. 2012;61:316–25. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e318265a58d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laschinger HK, Wong C, Regan S, Young-Ritchie C, Bushell P. Workplace incivility and new graduate nurses’ mental health: the protective role of resiliency. J Nurs Adm. 2013;43:415–21. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31829d61c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wing T, Regan S, Spence Laschinger HK. The influence of empowerment and incivility on the mental health of new graduate nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2013 Nov 28 doi: 10.1111/jonm.12190. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armmer F, Ball C. Perceptions of horizontal violence in staff nurses and intent to leave. Work. 2015;51:91–7. doi: 10.3233/WOR-152015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunn H. Horizontal violence among nurses in the operating room. AORN J. 2003;78:977–88. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)60588-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Camerino D, Estryn-Behar M, Conway PM, van Der Heijden BIJ, Hasselhorn H. Work-related factors and violence among nursing staff in the European NEXT Study: a longitudinal cohort study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45:35–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magnavita N, Heponiemi T. Workplace violence against nursing students and nurses: an Italian experience. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2011;43:203–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Topa G, Moriano JA. Stress and nurses’ horizontal mobbing: moderating effects of group identity and group support. Nurs Outlook. 2013;61:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bambi S, Becattini G, Pronti F, Lumini E, Rasero L. Ostilità laterali nei gruppi infermieristici di area critica. Indagine su cinque presidi ospedalieri della regione Toscana [Lateral hostilities in critical area nursing groups. Survey of five hospitals in the Tuscany region] Assist Inferm Ric. 2013;32:213–22. doi: 10.1702/1381.15359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bambi S, Becattini G, Giusti GD, Mezzetti A, Guazzini A, Lumini E. Lateral hostilities among nurses employed in intensive care units, emergency departments, operating rooms, and emergency medical services. A national survey in Italy. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2014;33:347–54. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Longo J, Sherman RO. Leveling horizontal violence. Nurs Manag. 2007;38:34–37. doi: 10.1097/01.numa.0000262925.77680.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khalil D. Levels of violence among nurses in Cape Town public hospitals. Nurs Forum. 2009;44:207–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2009.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Purpora C, Blegen MA, Stotts NA. Hospital staff registered nurses’ perception of horizontal violence, peer relationships, and the quality and safety of patient care. Work. 2015;51:29–37. doi: 10.3233/WOR-141892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Purpora C, Blegen MA, Stotts NA. Horizontal violence among hospital staff nurses related to oppressed self or oppressed group. J Prof Nurs. 2012;28:306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dumont C, Meisinger S, Whitacre MJ, Corbin G. Nursing 2012 Horizontal violence survey report. Nursing. 2012;42:44–49. doi: 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000408487.95400.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sellers KF, Millenbach L, Ward K, Scribani M. The degree of horizontal violence in RNs practicing in New York State. J Nurs Adm. 2012;42:483–487. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31826a208f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oh H, Uhm DC, Yoon YJ. Factors affecting workplace bullying and lateral violence among clinical nurses in Korea: descriptive study. J Nurs Manag. 2016;24:327–335. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson BL, Phelps C. Horizontal hostility: a threat to patient safety. JONAS Healthc Law Ethics Regul. 2013;15:51–57. doi: 10.1097/NHL.0b013e3182861503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Purpora C, Blegen MA. Job satisfaction and horizontal violence in hospital staff registered nurses: the mediating role of peer relationships. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:2286–94. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Griffin M. Teaching cognitive rehearsal as a shield for lateral violence: an intervention for newly licensed nurses. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2004;35:257–263. doi: 10.3928/0022-0124-20041101-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alspach G. Lateral hostility between critical care nurses: a survey report. Crit Care Nurse. 2008;28:13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reynolds G, Kelly S, Singh-Carlson S. Horizontal hostility and verbal violence between nurses in the perinatal arena of health care. Nurs Manag (Harrow) 2014;20:24–30. doi: 10.7748/nm2014.02.20.9.24.e1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sellers K, Millenbach L, Kovach N, Yingling JK. The prevalence of horizontal violence in New York State registered nurses. J N Y State Nurses Assoc. 2009 Fall-2010 Winter;40:20–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stanley KM, Dulaney P, Martin MM. Nurses ‘eating our young’-it has a name: lateral violence. S C Nurse. 2007;14:17–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walrafen N, Brewer MK, Mulvenon C. Sadly caught up in the moment: an exploration of horizontal violence. Nurs Econ. 2012;30:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson BL, Diedrich A, Phelps CL, Choi M. Bullies at work: the impact of horizontal hostility in the hospital setting and intent to leave. J Nurs Adm. 2011;41:453–458. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3182346e90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morrison MF, Lindo JML, Aiken J, Chin CR. Lateral violence among nurses at a Jamaican hospital: a mixed methods study. IJANS. 2017;6(2):85–91. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ayakdaş D, Arslantaş H. Colleague violence in nursing: A cross-sectional study. J Psy Nurs. 2018;9(1):36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pinar T, Acikel C, Pinar G, Karabulut E, Saygun M, Bariskin E, et al. Workplace violence in the health sector in Turkey: a national study. J Interpers Violence. 2015 Jun 28:pii. doi: 10.1177/0886260515591976. 0886260515591976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abe K, Henly SJ. Bullying (ijime) among Japanese hospital nurses: modeling responses to the revised Negative Acts Questionnaire. Nurs Res. 2010;59:110–118. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181d1a709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Linton DK, Power JL. The personality traits of workplace bullies are often shared by their victims: Is there a dark side to victims? Personality and Individual Differences. 2013;54:738–743. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Somani R, Karmaliani R, McFarlane J, Asad N, Hirani S. Prevalence of bullying/mobbing behaviour among nurses of private and public hospitals in Karachi, Pakistan. International Journal of Nursing Education. 2015;7:235. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Teymourzadeh E, Rashidian A, Arab M, Akbari-Sari A, Hakimzadeh SM. Nurses exposure to workplace violence in a large teaching hospital in Iran. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3:301–305. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pai DD, Sturbelle IC, Santos CD, Tavares JP, Lautert L. Physical and psychological violence in the workplace of healthcare professionals. Texto Contexto-Enferm. 2018;27(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chatziioannidis I, Bascialla FG, Chatzivalsama P, Vouzas F, Mitsiakos G. Prevalence, causes and mental health impact of workplace bullying in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit environment. BMJ open. 2018;8(2):e018766. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yildirim D. Bullying among nurses and its effects. Int Nurs Rev. 2009;56:504–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2009.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Çevik Akyil R, Tan M, Saritaş S, Altuntaş S. Levels of mobbing perception among nurses in Eastern Turkey. Int Nurs Rev. 2012;59(3):402–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2012.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Allen BC, Holland P, Reynolds R. The effect of bullying on burnout in nurses: the moderating role of psychological detachment. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71:381–390. doi: 10.1111/jan.12489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bortoluzzi G, Caporale L, Palese A. Does participative leadership reduce the onset of mobbing risk among nurse working teams? Journal of Nursing Management. 2014;22:643–652. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen WC, Hwu HG, Kung SM, Chiu HJ, Wang JD. Prevalence and determinants of workplace violence of health care workers in a psychiatric hospital in Taiwan. J Occup Health. 2008;50:288–293. doi: 10.1539/joh.l7132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pai HC, Lee S. Risk factors for workplace violence in clinical registered nurses in Taiwan. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1405–1412. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yildirim A, Yildirim D. Mobbing in the workplace by peers and managers: mobbing experienced by nurses working in healthcare facilities in Turkey and its effect on nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:1444–1453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jaradat Y, Nielsen MB, Bast-Pettersen R. Psychosomatic symptoms among Palestinian nurses exposed to workplace aggression. Am J Ind Med. 2018;61(6):533–537. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arcangeli G, Giorgi G, Ferrero C, Mucci N, Cupelli V. Prevalenza del fenomeno mobbing in una popolazione di infermieri di tre aziende ospedaliere italiane [Prevalence of the mobbing phenomenon in a population of nurses of three Italian hospitals] G Ital Med Lav Ergon. 2014;36:181–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reknes I, Pallesen S, Magerøy N, Moen BE, Bjorvatn B, Einarsen S. Exposure to bullying behaviors as a predictor of mental health problems among Norwegian nurses: results from the prospective SUSSH-survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(3):479–487. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Read E, Laschinger HK. Correlates of new graduate nurses’ experiences of workplace mistreatment. J Nurs Adm. 2013;43:221–228. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3182895a90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yun S, Kang J. Influencing factors and consequences of workplace bullying among nurses: a structural equation modeling. Asian Nurs Res. 2018;12(1):26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Laschinger HK, Grau AL, Finegan J, Wilk P. New graduate nurses’ experiences of bullying and burnout in hospital settings. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:2732–2742. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Waschgler K, Ruiz-Hernández JA, Llor-Esteban B, Jiménez-Barbero JA. Vertical and lateral workplace bullying in nursing: development of the hospital aggressive behaviour scale. J Interpers Violence. 2013;28:2389–2412. doi: 10.1177/0886260513479027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Berry PA, Gillespie GL, Gates D, Schafer J. Novice nurse productivity following workplace bullying. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2012;44:80–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01436.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kivimäki M, Elovainio M, Vahtera J. Workplace bullying and sickness absence in hospital staff. Occup Environ Med. 2000;57:656–660. doi: 10.1136/oem.57.10.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Laschinger HK. Impact of workplace mistreatment on patient safety risk and nurse-assessed patient outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2014;44:284–290. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Simons S. Workplace bullying experienced by Massachusetts registered nurses and the relationship to intention to leave the organization. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2008;31:e48–59. doi: 10.1097/01.ANS.0000319571.37373.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vessey JA, Demarco RF, Gaffney DA, Budin WC. Bullying of staff registered nurses in the workplace: a preliminary study for developing personal and organizational strategies for the transformation of hostile to healthy workplace environments. J Prof Nurs. 2009;25:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kwok RP, Law YK, Li KE, Ng YC, Cheung MH, Fung VK, et al. Prevalence of workplace violence against nurses in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2006;12:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aksakal FN, Karaşahin EF, Dikmen AU, Avci E, Ozkan S. Workplace physical violence, verbal violence, and mobbing experienced by nurses at a university hospital. Turk J Med Sci. 2015;45:1360–1368. doi: 10.3906/sag-1405-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen WC, Sun YH, Lan TH, Chiu HJ. Incidence and risk factors of workplace violence on nursing staffs caring for chronic psychiatric patients in Taiwan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:2812–2821. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6112812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hesketh KL, Duncan SM, Estabrooks CA, Reimer MA, Giovannetti P, Hyndman K, et al. Workplace violence in Alberta and British Columbia hospitals. Health Policy. 2003;63:311–321. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(02)00142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Korhan EA, Guler EK, Khorshid L, Eser I. Mobbing experienced by nurses working in hospitals: an example of turkey. International Journal of Caring Sciences. 2014;7:642–651. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rush KL, Adamack M, Gordon J, Janke R. New Graduate transition programs: relationships with access to support and bullying. Contemp Nurse. 2014;48(2):219–228. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2014.11081944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Simons SR, Stark RB, DeMarco RF. A new, four-item instrument to measure workplace bullying. Res Nurs Health. 2011;34:132–140. doi: 10.1002/nur.20422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Terzioglu F, Temel S, Uslu Sahan F. Factors affecting performance and productivity of nurses: professional attitude, organisational justice, organisational culture and mobbing. J Nurs Manag. 2016 Mar 29 doi: 10.1111/jonm.12377. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ulrich BT, Lavandero R, Hart KA, Woods D, Leggett J, Taylor D. Critical care nurses’ work environments: a baseline status report. Crit Care Nurse. 2006;26:46–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ulrich BT, Lavandero R, Hart KA, Woods D, Leggett J, Friedman D, et al. Critical care nurses’ work environments 2008: a follow-up report. Crit Care Nurse. 2009;29:93–102. doi: 10.4037/ccn2009619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Moayed FA, Daraiseh N, Shell R, Salem S. Workplace bullying: a systematic review of risk factors and outcomes. Theor Issues Ergon. 2006;7:311–327. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Royal College of Nursing (RCN) [Access made on 19-08-2011];Dealing with bullying and harassment at work – a guide for RCN members. January 2001, Revised December 2005 http://www.rcn.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/78502/001302.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hamblin LE, Essenmacher L, Upfal MJ, Russell J, Luborsky M, Ager J, et al. Catalysts of worker-to-worker violence and incivility in hospitals. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:2458–2467. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lamontagne C. Intimidation: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2010;45:54–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2009.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vessey JA, De Marco R, Di Fazio R. Bullying, harassment, and horizontal violence in the nursing workforce. The state of the science. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2010;28:133–157. doi: 10.1891/0739-6686.28.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Johnson SL. An ecological model of workplace bullying: a guide for intervention and research. Nurs Forum. 2011;46:55–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2011.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yildirim D, Yildirim A, Timucin A. Mobbing behaviors encountered by nurse teaching staff. Nurs Ethics. 2007;14:447–463. doi: 10.1177/0969733007077879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Edwards SL, O’Connell CF. Exploring bullying: implications for nurse educators. Nurse Educ Pract. 2007;7:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Leymann H. The content and development of mobbing at work. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 1996;5:165–184. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Johnson SL. International perspectives on workplace bullying among nurses: a review. Int Nurs Rev. 2009;56:34–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2008.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Castronovo MA, Pullizzi A, Evans S. Nurse bullying: a review and a proposed solution. Nurs Outlook. 2016;64:208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Coursey JH, Rodriguez RE, Dieckmann LS, Austin PN. Successful implementation of policies addressing lateral violence. AORN J. 2013;97:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]