Abstract

Even tough inguinal hernia repair is among the commonest operations in general surgery, the choice for an optimal approach continues to be a controversial topic. Because of the low recurrence rates and low prevalence of complications, tension-free mesh augmented operation has become the standard technique in inguinal hernia surgery, significantly reducing hernia recurrence rates. On the contrary, prevalence of chronic postoperative groin pain (CPGI) i.e. pain beyond a three month-postoperative period still remains significant: as rates of CPGI may range between 15% and 53%, surgical approaches aimed to avoid chronic post-hernioplasty pain have been extensively debated, and the avoidance of CPGI has become one of the primary endpoints of surgical research on inguinal hernia repair). Recently, a sound base of evidence suggested that the entrapment of peripheral nervous fibers innervating part of the structures in the inguinal canal and stemming from ilioinguinal (Th12), iliohypogastric (L1) nerves as well as from the genital branch of the genito-femoral nerve (L1, L2), may eventually elicit CPGI (1-10). Consequently, innovative fixation modalities (e.g. self-gripping meshes, glue fixation, absorbable sutures), and new material types (e.g. large-pored meshes) with self-adhesive sticking or mechanical characteristics, have been developed in order to avoid penetrating fixings such as sutures, clips and tacks. However, some uncertainties still remain about the pros and cons of such meshes in terms of chronic pain, as new, innovative mesh apparently does not significantly reduce the rate of CPGI. Parietex ProGrip® (MedtronicsTM) is a bicomponent mesh comprising of monofilament polyester and a semi re-absorbable polylactic acid gripping system that allows sutureless fixation of prosthetic mesh to the posterior inguinal wall. As ProGrip® does not requires additional fixation, inguinal canal may be closed within minutes after adequate groin dissection, ultimately shortening operating time. In other words, ProGrip® has the potential for significant savings, in terms of surgical and post-operating costs as well (10). The aim of our study is therefore to compare the results of the same technique with two different mesh materials (ProGrip® mesh vs. polyethylene mesh), in terms of operative time, post-operative pain, complications, and recurrence rates. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: inguinal hernia, mesh repair, self-gripping mesh

Introduction

Even tough inguinal hernia repair is among the commonest operations in general surgery (1), the choice for an optimal approach continues to be a controversial topic (2). Because of the low recurrence rates and low prevalence of complications, tension-free mesh augmented operation has become the standard technique in inguinal hernia surgery (2-4), significantly reducing hernia recurrence rates (3, 5). On the contrary, prevalence of chronic postoperative groin pain (CPGI) i.e. pain beyond a three month-postoperative period still remains significant (3): as rates of CPGI may range between 15% and 53%, surgical approaches aimed to avoid chronic post-hernioplasty pain have been extensively debated, and the avoidance of CPGI has become one of the primary endpoints of surgical research on inguinal hernia repair (2, 5, 5). Recently, a sound base of evidence suggested that the entrapment of peripheral nervous fibers innervating part of the structures in the inguinal canal and stemming from ilioinguinal (Th12), iliohypogastric (L1) nerves as well as from the genital branch of the genito-femoral nerve (L1, L2), may eventually elicit CPGI (1-10). Consequently, innovative fixation modalities (e.g. self-gripping meshes, glue fixation, absorbable sutures), and new material types (e.g. large-pored meshes) with self-adhesive sticking or mechanical characteristics, have been developed in order to avoid penetrating fixings such as sutures, clips and tacks (2, 3, 3, 3, 3). However, some uncertainties still remain about the pros and cons of such meshes in terms of chronic pain, as new, innovative mesh apparently does not significantly reduce the rate of CPGI (2, 3). Parietex ProGrip® (MedtronicsTM) is a bicomponent mesh comprising of monofilament polyester and a semi re-absorbable polylactic acid gripping system that allows sutureless fixation of prosthetic mesh to the posterior inguinal wall. As ProGrip® does not requires additional fixation, inguinal canal may be closed within minutes after adequate groin dissection, ultimately shortening operating time. In other words, ProGrip® has the potential for significant savings, in terms of surgical and post-operating costs as well (10).

The aim of our study is therefore to compare the results of the same technique with two different mesh materials (ProGrip® mesh vs. polyethylene mesh), in terms of operative time, post-operative pain, complications, and recurrence rates.

Materials and Methods

This research was conducted as a controlled, unicentric, two-cohort pilot study at the Department of Surgery of the Hospital of Codogno, Local Health Unit of Lodi - Northern Italy between April and June 2014.

Inclusion criteria

All consecutive patients with age between 18 and 80, male or female, were considered eligible for the study. Only patients having a unilateral, primary inguinal hernia were eventually included.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if they had suffered from large inguino-scrotal hernia, bilateral inguinal hernia, recurrent inguinal hernia, incarcerated hernia, irreducible hernia or with significant comorbidities (ASA >2). Patients having a poor understanding of the Italian language were also excluded.

Clinical outcomes

Primary outcomes included: early and late post-operative pain, and complications. Moreover, total number of non-steroidal analgesic used, as well as residual symptoms such as paresthesia, chronic discomfort, and chronic pain were collected at the end of the follow up. Secondary outcomes included the total operative time and the rate recurrence.

Randomization and blinding

Computer generated randomizations were communicated to the surgical team after adequate groin dissection and just before placement of prosthetic mesh.

Ethics

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study after detailed explanation of possible complications of hernia repair. As at the time of the study both prosthetic meshes were in use at the Hospital of Codogno, but no internal or institutional recommendations guiding the choice for the appropriate prosthetic material had been put in place, and individual participants cannot be identified based on the presented material, no preliminary evaluation by the Ethical Committee was reputed necessary.

Operative details

After obtaining informed consent, patients were assessed by anesthetists for fitness of operation. The operations were performed by a single specialist (LP) in hernia surgery. Standardized procedure was utilized: 20 patients approached by standard Lichtenstein procedure as described in literature:

Inguinal incision 1cm above pubic tubercle and horizontal (5-6cm);

Exposure of inguinal canal by opening external oblique aponeurosis;

Dissection and isolation of inguinal cord with nerve-sparing approach;

Identification and management of hernia sac;

Placement and fixation of hernia mesh (15x7.5 cm) with continuous suture to fix it at the inguinal ligament; two absorbable sutures to fix the mesh at the rectus sheath and internal oblique aponeurosis.

Internal ring closure by closing posterior mesh with suture between posterior tails of the mesh and inguinal ligament.

Closure of external oblique aponeurosis in continuous suture over inguinal cord.

Closure of inguinal incision by subcutaneous and cutaneous suture.

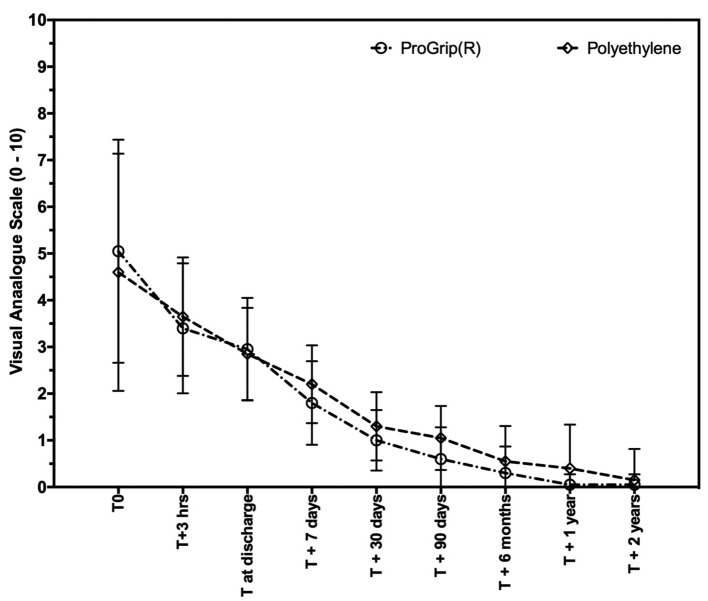

The other 20 patients underwent the same surgical approach but we positioned a Progrip® mesh without any suture, in the same position of the Lichtenstein procedure (Figure 1); the only attention that we used was to secure a necessary overlap to the anatomic structures specially over pubic tubercle.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of Progrip® mesh. As shown, the surface in front of the posterior inguinal wall is characterized by many re-absorbable polylactic acid gripping peduncles that allow sutureless fixation of prosthetic mesh. In the scheme, Progrip® mesh is furtherly elaborated through an incision that allows an easily fixation of the spermatic peduncle

Data collection and follow-up

Patients were assessed in hospital before surgical procedures (i.e. T0), 3 hours after surgery (T+3), at discharge (usually, around 24 hours after surgical procedures), and then followed-up in outpatient clinical T + 7 days, T + 30 days, T + 90 days, T + 6 months, T + 1 year, T + 2 years. More specifically, patients were asked to retrieve whether they complained groin pain assessed as Visual Analogue Scale (0 to 10), discomfort and paresthesia. Moreover, they were asked about the use of non-steroidal analgesic drugs for CGPI and eventually assessed for recurrence and post-surgical complications. Healthcare professionals who performed post-surgical assessment were blinded for the mesh group assigned as treatment.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t test for unpaired data were employed for the comparison of continuous variables, whereas association of dichotomous variables was assessed through Fisher’s exact test because of the reduced number of patients included in the sample. Statistical analysis was performed by using software package SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY). A difference with p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

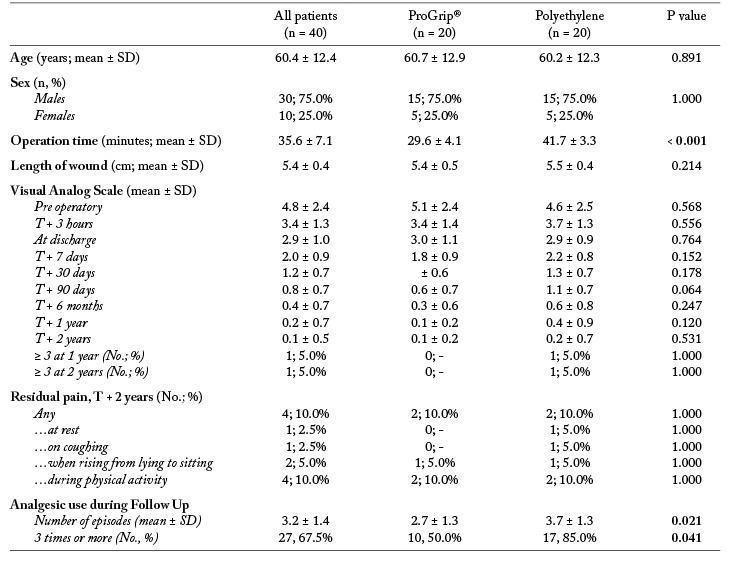

A total of 40 patients (30 males, 10 females) with the diagnosis of a unilateral primary inguinal hernia were enrolled. Of them, 20 were assigned to the ProGrip® group and 20 were assigned to the polyethylene group. The two group were comparable concerning all demographic variables (M:F = 15:5 in both groups; mean age: 60.7 years ± 12.9 vs. 60.2 years ± 12.3 for ProGrip® and polyethylene group, respectively: p = 0.814).

Operation time

The mean duration of the surgical procedures was 35.6 m ± 7.1. Within the ProGrip® group, the mean duration of the surgical procedure was 29.6 m ± 4.1, and resulted significantly shorter than that identified within the polyethylene group (41.7 m ± 3.3; p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 40 patients included in the study

Hospital stay

Median hospital stay for all enrolled patients was equal to 1 day (min 1; max 3). More precisely, patients assigned to the polyethylene group stayed for a mean of 1.6 days ± 1.9, whereas ProGrip® group recorded a mean hospital stay of 1.3 ± 1.6 (p = 0.598).

Surgical issues

Mean length of surgical wound was 5.4 cm ± 0.4, with no significant differences between the two groups (5.4 cm ± 0.5 vs. 5.5 cm ± 0.4 in ProGrip® and polyethylene group, respectively; p = 0.214). None among patients participating to this study suffered any intra-operative and/or early/late surgical complication.

Pain

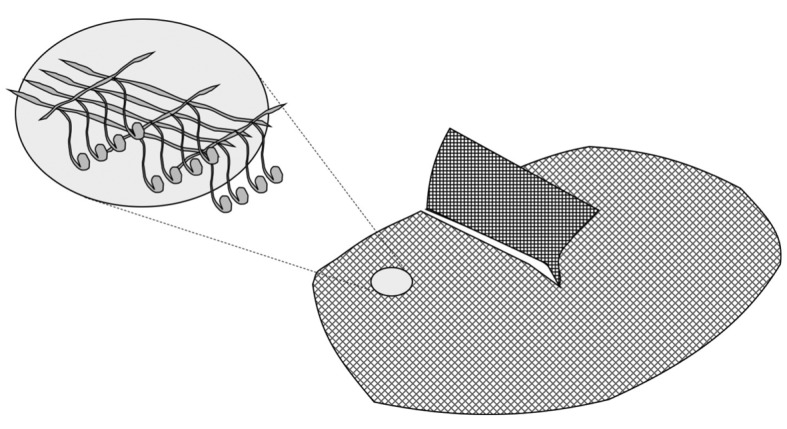

Preoperative pain assessed by the VAS identified a mean of 4.9 ± 2.4, and although mean VAS for ProGrip® group was slightly higher than for polyethylene group, the difference was not statistically significant (5.1 ± 2.4 vs. 4.6 ± 2.5; p = 0.568). As shown in Figure 2, VAS remained somehow greater in ProGrip® than in polyethylene group also on T+3 hours (3.4 ± 1.4 vs. 3.7 ± 1.3; p = 0.556) and on the day of discharge (3.0 ± 1.1 vs. 2.9 ± 0.9; p = 0.764), but the difference was not significantly different between the two groups. On the contrary, since the first re-evaluation after 7 days, the mean VAS score for patients within the ProGrip® group was non significantly lower than that for polyethylene patients, but the difference remained constantly not significant until the end of follow-up.

Figure 2.

Change of the mean VAS score within the two groups over time

Residual pain at the end of follow up was reported by a total of 4 patients (10.0%), and the shares were identical within the two groups (10.0%, p = 1.000). No significant differences were identified among the causes eliciting groin pain between the two groups. Focusing on the patients suffering from moderate-severe pain (VAS ≥ 3), such complaints were referred only by 1 patient among the polyethylene group at both 1 year and 2 years postoperatively, but again the difference was not statically significant (Fisher’s exact test p = 1.000 in both cases).

Eventually, patients within ProGrip® group referred the use of analgesic during follow-up 2.7 ± 1.4 times vs. 3.7 ± 1.3 times in polyethylene group, and similarly the share of patients requiring use of analgesic during the follow-up (dichotomized as < 2 times vs. ≥ 3 times) was higher in polyethylene group than in ProGrip® group (50.0% vs. 85.0%, respectively). In both cases, the difference was statistically significant (p = 0.021, and p = 0.041).

Discussion

Since the tension-free hernioplasty was described in 1989 (12, 13), prosthetic tension free repair changed the history of groin hernia surgery, significantly reducing recurrence rates and allowing a faster recovery, mainly due to a reduced local pain. The impact of the new approach also reflected on sanitary costs, and organization of surgical units. Nowadays most of the centers, indeed, perform groin hernia surgery in outpatient basis. On the other hand, the use of prosthetic material didn’t entail an increased rate of local infection, probably due to a better local and systemic prophylaxis (1-10).

Unfortunately, post-operative pain remains a significant issue (1-10, 12, 13), including both post-operative and late, chronic pain – or CGPI. Whereas management of early post-operative pain usually resides on analgesic, CGPI may ultimately require further assessment and medical or surgical intervention (12, 13). As GPCI may reduce productivity due to discomfort and absenteeism, being also associated with significant medical expenses (14-18, 19), it remains one of the unsolved issues with prosthetic repair.

Available base of evidence suggests that CGPI may found its etiology in peri-operative nerve damage, post-operative fibrosis or mesh-related fibrosis (12). Consequently, every technical improvement aimed to reduce trauma and/or inflammatory involvement of the abdominal wall has the potential to reduce its prevalence.

In the last decades, moving from outstanding results on postoperative recovery achieved in abdominal and bariatric surgery (19-27), laparoscopic (either transabdominal or totally extraperitoneal) approach to groin as well as ventral hernia (22) has been developed in order to minimize the parietal dissection and possibly quicken postoperative recovery, but its use as routine procedure is still source of debates, due to a higher operative risk and costs. To date, standard inguinotomic prosthetic repair remains the cornerstone of groin hernia surgery, except the case of bilateral or recurrent hernias referring to units specialized in laparoscopic surgery (1-10, 12, 13, 20-27).

ProGrip® meshes, similarly to other semi-absorbable materials that incorporate self-fixing properties, are minimally invasive towards abdominal tissues, and have been shown to provide satisfactory repair both in open and laparoscopic (2, 28). However, available reports are somehow tantalizing, as the balance between pros and cons may be doubtful (4, 6, 6, 6). First at all, even though patients within ProGrip® group beneficed of shorter operation time (29.6 m ± 4.1 vs. 41.7 m ± 3.3), and during the follow-up referred a reduced GPCI-driven consumption of analgesic, differences in long-term outcomes have been minimal and not significant. Moreover, no significant differences in terms of complications, rates of relapses, and even of self-assessed pain were identified between the two study groups. As in previous reports, cost-effectiveness of new prosthetic meshes compared with more conventional materials may therefore be questioned (2). However, such analyses are beyond the scope of this study, and further investigations are needed in order to make any final conclusions.

Some limitations of our study have to be addressed. First at all, our study included a reduced number of patients: although inclusion criteria presumptively contributed to minimize confounding factors and more specifically the effects associated with comorbidities, our results may be therefore limitedly generalizable. Moreover, although VAS as a measure of pain and discomfort is extensively used in surgical research, such perceptions are significantly heterogeneous among patients and different ethnicities (29-32). In order to retrieve more objective data, we recalled the episodes of pain requiring analgesic use, but also such approach has been criticized because of a significant recall bias (29, 31). Finally, our data are affected by a relatively short follow up. Although the rate of chronic pain may not decrease significantly by the third postoperative year compared with the 6-mo follow-up (2), other reports suggest that CGPI may be a significant issue even 5 years or more after surgery, and some complications such as testicular atrophy as well as groin hernia recurrence may be more appropriately appreciated only for longer observation periods (10, 33).

Conclusion

Hernia repair with ProGrip® mesh seems to allow for an easier and equally safe surgical procedure, significantly reducing operative times. The possible effect on postoperative pain should be test on large sample size.

References

- 1.Fortelny RH. Petter-Puchner AH. Redl H. May C. Pospischil W. Glaser K. Assessment of pain and quality of life in Lichtenstein hernia repair using a new monofilament PTFE mesh: comparison of suture vs. fibrin-sealant mesh fixation. Front Surg. 2014;1:45. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2014.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nikkolo C. Vaasna T. Murruste M. Suumann J. Kirsimägi Ü. Seepter H, et al. Three-year results of a randomized study comparing self-gripping mesh with sutured mesh in open inguinal hernia repair. J Surg Res. 2017;209:139–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zwaans WAR. Perquin CW. Loos MJA. Roumen RMH. Scheltinga MRM. Mesh Removal and Selective Neurectomy for Persistent Groin Pain Following Lichtenstein Repair. World J Surg. 2017;41:701–12. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3780-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ersoz F. Culcu S. Duzkoylu Y. Bektas H. Sari S. Arikan S, et al. Clinical Study The Comparison of Lichtenstein Procedure with and without Mesh-Fixation for Inguinal Hernia Repair. Surg Res Pract. 2016;2016:8041515. doi: 10.1155/2016/8041515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nikkolo C. Vaasna T. Murruste M. Seepter H. Suumann J. Tein A, et al. Single-center, single-blinded, randomized study of self-gripping versus sutured mesh in open inguinal hernia repair. J Surg Res. 2015;194:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma P. Boyers D. Scott N. Hernández R. Fraser C. Cruickshank M, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of open mesh repairs in adults presenting with a clinically diagnosed primary unilateral inguinal hernia who are operated in an elective setting: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19:1–142. doi: 10.3310/hta19920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stav A. Reytman L. Stav M-Y. Troitsa A. Kirshon M. Alfici R, et al. Transversus Abdominis Plane Versus Ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric Nerve Blocks for Analgesia Following Open Inguinal Herniorrhaphy. Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2016;7(3):e0021–9. doi: 10.5041/RMMJ.10248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lange JFM. Meyer VM. Voropai DA. Keus E. Wijsmuller AR. Ploeg RJ, et al. The role of surgical expertise with regard to chronic postoperative inguinal pain (CPIP) after Lichtenstein correction of inguinal hernia: a systematic review. Hernia. 2016;20:349–56. doi: 10.1007/s10029-016-1483-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Köhler G. Lechner M. Mayer F. Köckerling F. Schrittwieser R. Fortelny RH, et al. Self-Gripping Meshes for Lichtenstein Repair. Do We Need Additional Suture Fixation? World J Surg. 2017;40:298–308. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-3313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan JKM. Yip J. Foo DCC. Lo OSH. Law WL. Randomized trial comparing self gripping semi re-absorbable mesh (PROGRIP) with polypropylene mesh in open inguinal hernioplasty: the 6 years result. Hernia. 2017;21:9–16. doi: 10.1007/s10029-016-1545-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takata H. Matsutani T. Hagiwara N. Ueda J. Arai H. Yokoyama Y, et al. Assessment of the incidence of chronic pain and discomfort after primary inguinal hernia repair. J Surg Res. 2016;206(2):391–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hakeem A. Shanmugam V. Inguinodynia following Lichtenstein tension-free hernia repair: A review. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(14):1791–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i14.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakorafas GH. Halikias I. Nissotakis C. Kotsifopoulos N. Stavrou A. Antonopoulos C, et al. Open tension free repair of inguinal hernias; the Lichtenstein technique. BMC Surgery. 2001;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manzoli L. Sotgiu G. Magnavita N. Durando P. National Working Group on Occupational Hygiene of the Italian Society of Hygiene, Preventive Medicine and Public Health (SIti). Evidence-based approach for continuous improvement of occupational health. Epidemiol Prev. 2015;39:81–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Signorelli C. Riccò M. Odone A. The Italian National Health Service expenditure on workplace prevention and safety (2006-2013): a national-level analysis. Ann Ig. 2016;28:313–8. doi: 10.7416/ai.2016.2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riccò M. Cattani S. Gualerzi G. Signorelli C. Work with visual display units and musculoskeletal disorders: a cross-sectional study. Med Pr. 2016;67:707–19. doi: 10.13075/mp.5893.00471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riccò M. Pezzetti F. Signorelli C. Back and neck pain disability and upper limb symptoms of home healthcare workers: a case-control study from Northern Italy. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2017;30:291–304. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.00629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riccò M. Cattani S. Signorelli C. Personal risk factors for carpal tunnel syndrome in female visual display unit workers. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2016;29:927–36. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.00781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riccò M. Marchesi F. Tartamella F. Rapacchi C. Pattonieri V. Odone A, et al. The impact of bariatric surgery on health outcomes, wellbeing and employment rates: analysis from a prospective cohort study. Ann Ig. 2017;29:440–52. doi: 10.7416/ai.2017.2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohtani H. Tamamori Y. Arimoto Y. Nishiguchi Y. Maeda K. Hirakawa K. A Meta-Analysis of the Short- And Long-Term Results of Randomized Controlled Trials That Compared Laparoscopy-Assisted and Open Colectomy for Colon Cancer. J Cancer. 2012;3:49–57. doi: 10.7150/jca.3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarli L. Rollo A. Cecchini S. Regina G. Sansebastiano G. Marchesi F, et al. Impact of Obesity on Laparoscopic-assisted Left Colectomy in Different Stages of the Learning Curve. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:114–7. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31819f2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marchesi F. Pinna F. Cecchini S. Sarli L. Roncoroni L. Prospective Comparison of Laparoscopic Incisional Ventral Hernia Repair and Chevrel Technique. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:306–10. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31822b09a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marchesi F. Percalli L. Pinna F. Cecchini S. Riccò M. Roncoroni L. Laparoscopic subtotal colectomy with antiperistaltic cecorectal anastomosis: a new step in the treatment of slow-transit constipation. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1528–33. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-2092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marchesi F. Pinna F. Percalli L. Riccò M. Costi R. Pattonieri V, et al. Totally laparoscopic right colectomy: theoretical and practical advantages over the laparo-assisted approach. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2013;23:418–24. doi: 10.1089/lap.2012.0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marchesi F. De Sario G. Reggiani V. Tartamella F. Giammaresi A. Cecchini S, et al. Road Running After Gastric Bypass for Morbid Obesity: Rationale and Results of a New Protocol. Obes Surg. 2015;25:1162–70. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1517-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buchwald H. Avidor Y. Braunwald E. Jensen MD. Pories W. Fahrbach K, et al. Bariatric Surgery. JAMA. 2004;292:1724–37. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Panfilis C. Generali I. Elisabetta D. Marchesi F. Ossola P. Marchesi C. Temperament and one-year outcome of gastric bypass for severe obesity. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:144–8. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varghese J. Sutton P. Kosai N. Evans J. Laparoscopic preperitoneal mesh repair using a novel self-adhesive mesh. J Min Access Surg. 2011;7(3):192–5. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.83514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garimella V. Cellini C. Postoperative Pain Control. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 2013;26:191–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1351138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flaherty SA. Pain measurement tools for clinical practice and research. AANA J. 1996;64:133–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Breivik H. Borchgrevink PC. Allen SM. Rosseland LA. Romundstad L. Hals EK, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:17–24. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCarthy M. Chang C-H. Pickard AS. Giobbie-Hurder A. Price DD. Jonasson O, et al. Visual Analog Scales for Assessing Surgical Pain. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:245–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marchesi F. Rapacchi C. Cecchini S. Sarli L. Tartamella F. Roncoroni L. Late surgical complications of subtotal colectomy with antiperistaltic caeco-rectal anastomosis for slow transit constipation A critical analysis. Ann Ital Chir. 2016;87:31–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]