Abstract

Background and aim of the work: Negative health effects have been associated with the changes in lifestyles in relation with the low income of population. Consequently, in our study we investigated the frequency changes of alcohol and smoke consumption, physical activity, and quality of life in families of Marche Region in Central Italy. Methods: In the period 2016-2017, an anonymous questionnaire has been distributed to junior highschool students of Camerino, Fabriano, and Civitanova Marche of Marche Region. The Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA), was used to assess subjective quality of life. Results: Data obtained in this research were used to analyze lifestyle changes, specifically those involving alcohol consumption, smoking, and physical activity, and to assess perceived general quality of life. In all categories of population, an increase of frequency in alcohol consumption was observed. On the contrary, for the tobacco smoke we observed a reduction in particular in the parents category. The MANSA mean value was 4.5 with a Standard Deviation of 1.3. Conclusions: As underlighted, also, by results of the MANSA test we can hypothesize a reduction in the family income produces a change of lifestyles. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: economic downturn, alcohol, smoke, physical activity, quality of life

Introduction

The economic crisis started in Europe at the end of 2007 with differences in many countries.

Negative health effects have been associated with this event, and a number of studies have focused on a possible association between the economic downturn and the consequences of the changes in lifestyles, have been conducted (1).

A part of literature have expressed concern that the consequences of the job losses could be responsible for the depression states and, in addiction, for problems associated with the use of alcohol and smoking, as a response to stress (2). A 2009 study reported that an over 3% increase in unemployment had effect on suicides at ages younger than 65 years and deaths from alcohol abuse (2).

These factors can have a severe effect not only on public health but also on societal welfare (3-7). It should be remembered that incorrect lifestyles are also considered related to the development of serious diseases, such as diseases of the circulatory system, metabolic diseases, which play an important role among the main causes of death in the population and that entail significant costs for the Public Health (8). Youth unemployment is an important consequence of the economic downturn, and is also cause of psychophysical health problems and increased smoking and alcohol consumption. Moreover, recent studies have found that the effect of youth unemployment on mental health remains in adulthood, independent of later unemployment experiences.

Understanding the real relationship between economic crises and adoption of less healthy lifestyles is complex because of differences in national unemployment rates (9). In fact, studies on the impact of economic crises on alcohol and tobacco consumption have produced quite varied results. Two different effects were associated with the economic downturn: one study reported increases in the prevalence of drinking and/or smoking, while another observed a dampening effect on the these behaviors, perhaps due to increased prices and decreased purchasing power (10, 11).

In this context, we surveyed parents of middle school students in an area of the Marche Region in central Italy that has been particularly hard hit by the economic crisis. Previous studies, useful for a comparative analysis of the trend pre-crisis, were conducted among high school and university students in the Marche Region, to analyze their knowledge about and use of legal or illegal substances. The results indicated that high school students regularly smoke and consume alcohol (12, 13). Other studies conducted in the same region found that 36.4% of high school students surveyed that use alcohol, tobacco and antidepressant (14), and 28.2% of university students surveyed smoked, and consumed alcohol regularly (several times a week or more often) (15).

The aims of the present study were a) to investigate the effect of the economic downturn on lifestyle, in terms of changes in smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity, and b) to explore the effects on the psychological profile of respondents and to assess subjective quality of life.

Methods

The research was conducted in the period 2016-2017 using an anonymous questionnaire consisting of five sections: “Social and anagraphic data”, “Change of lifestyle “ (physical activity, consumption of alcohol, smoking, consumption of drugs and the need to undergo medical examinations), “Change in eating habits” (regarding the amount of food products bought, the type of stores and the general variation of purchases observed with the increase of prices), “Details of consumption” (changes in consumption of specific categories of foods) (16, 17), “The quality of life of the subjects” (the level of satisfaction with one’s personal life) (18, 19). The questionnaire, prepared and distributed by the School of Pharmacy, Camerino University, was first validated by administering it to a sample of people representative of different socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds.

The level of satisfaction with one’s personal life was evaluated using the MANSA scale (Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life), an instrument that affords a fairly quick way to assess satisfaction with quality of life as a whole and also in terms of different life domains. SQOL (Subjective Quality Of Life) is the mean score of 12 satisfaction ratings. Each item is rated on a Likert type scale ranging from 1 (lowest satisfaction) to 7 (highest satisfaction) with 4 as a neutral middle point (20). We chose the MANSA scale because our group had observed its usefulness in a previous study conducted to evaluate the quality of life of the residents of post-earthquake housing in L’Aquila, central Italy (21, 22).

In the present study, a questionnaire was distributed in middle schools of Camerino, Fabriano, and Civitanova Marche in the Marche Region, cities in the geographical area served by the University of Camerino and characterized by different socio-economic and cultural backgrounds. The middle schools were chosen randomly and the questionnaire was given to the students, with the request that they ask one of their parents to fill it out.

Questionnaire answers were stored and processed using Microsoft Excel sheets, and statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 20 (SPSS Inc).

Results

Data from the 880 people who responded to the questionnaire were used to analyze lifestyle changes, specifically those involving alcohol consumption, smoking, and physical activity, and to assess perceived general quality of life. A total of 1860 questionnaires were distributed and 1091 were returned (58.7%), but about 10% of these were blank or completed incorrectly (192 blank, 19 invalid because of obvious tampering with the paper or loss of anonymity). Thus the study analyzed 880 correctly completed questionnaires, 47.3% of the total number of those distributed.

The sample included 310 males (35.2%) and 570 females (64.8%) whose average age ranged from 41 to 50 (57.2%); 52.5% of sample has a high school qualification.

Lifestyles: alcohol consumption, smoking and physical activity

As regards the habitual consumption of alcohol, 626 (70 %) subjects responded that they do not consume alcohol habitually, while 231 (27 %) indicated that they do. Analysis of the data showed a relevant trend in alcohol consumption.

In addition,answering the question “Which family member usually drinks alcohol?” 231 (26.3%) subjects indicated parent 1, 626 (71.1%) indicated parent 2, while only 1 subject (0.1%) indicated that the children drink alcohol.

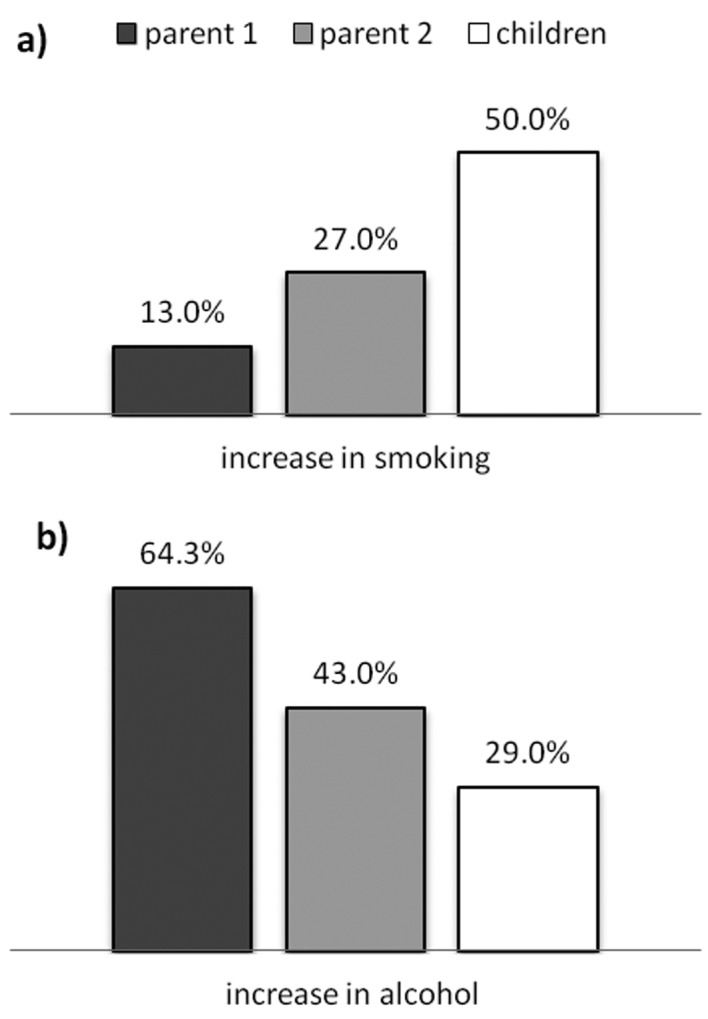

In particular, analyzing the change of frequency in alcohol consumption, an increase in all categories was observed. Even if the higher percentages were recorded for both parents, the 29% in alcohol consumption frequency by children is very severe (Fig. 1 a).

Figure 1.

a) increase in smoking and b) increase in the frequency of alcohol consumption

As for smoking habits, 297 subjects (34%) answered that someone in the family smokes. When asked, “Which member of the family smokes?”, 605 people (68.8 %) did not answer,187 (21.2%) indicated the parent 1, 70 (8.0%) indicated the parent 2, while only 18 (2%) indicated the children.

The “parents” category had a smaller increase in smoking than in drinking alcoholic beverages; instead, in the children category, the data pre-crisis and post-crisis appear to be unvaried (Fig. 1b).

Analyzing all groups of smokers about the reduction, parent 1 had an 87.0% reduction in smoking,parent 2 had a 73.1% reduction, and children had a 50.0% reduction, confirming the previously trend.

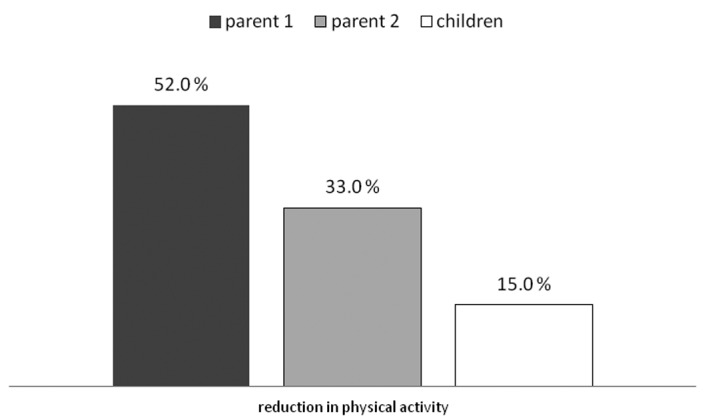

In addition, we investigated how the economic crisis changed the physical activity in our sample.When asked, “Do any family members do regular physical activity?”, 524 subjects (59%) responded yes, 342 (39%) said no and only 14 (2%) did not respond.

When asked “Which family member regularly does physical activity?”, 382 (43.4%) people did not answer, 252 (28.6 %) indicated the parent 1, while only 177 (20.2 %) reported that the children engage in physical activity.

Furthermore, decreased frequency of physical activity was reported for all categories, in particular for the parent category (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Reduction in physical activity

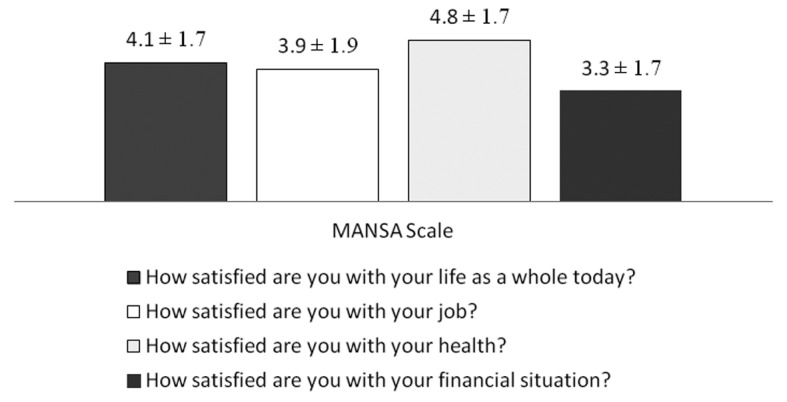

Quality of life

In order to understand the psychological status underlying changed habits of life, people were asked to provide information about their satisfaction in various fields, such as work, finances, health, etc. Respondents in this study rated their satisfaction with their quality of life at the neutral middle point, as seen in the MANSA mean value of 4.5±SD 1.3.

Prompted by the question “How satisfied are you with your current financial situation?” 94% of respondents indicated dissatisfaction (Fig. 3). The answers about job satisfaction confirm and reinforce those about finances: 80% of the sample indicated a level of satisfaction tending to dissatisfaction (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Quality of Life MANSA Scale Results

To analyze these results, we eliminated data from Camerino, where a large part of the population holds government jobs, and has not been as severely impacted by the economic downturn as those in the more industrial cities of Fabriano and, to a lesser degree, Civitanova Marche. Fabriano has suffered the closure of factories central to the economy of the city, with consequent closure of smaller businesses that served the factories, and the city’s economy has been severely harmed. In contrast, Civitanova Marche, a coastal city popular for its beaches and small businesses, has fared better during the general economic downturn, with less severe consequences. The average MANSA score for Fabriano was 3, while that for Civitanova Marche was 4. This difference, even if statistically not significant, might indicate a higher level of dissatisfaction in Fabriano than in Civitanova Marche.

Discussion and Conclusions

This paper shows some lifestyle changes trigged by the economic downturn in our Region, and indicates a need for a broader and deeper investigation of this phenomenon. In particular, comparing parents and children, we found behavior differences for every lifestyle aspect examined. Analyzing the problem of less healthy lifestyles and particularly the increased frequency of alcohol consumption and smoking and the decreased frequency of physical activity, we can point to definite changes in habits in the post-crisis period.

The results on alcohol use are very interesting, is the result about the alcohol use. Increased alcohol consumption was reported in both parents and children, in line with data reported in the literature (2).

It may be possible that the combination of youth unemployment and adult unemployment in the same household may lead to increased alcohol consumption by both categories.

The effects of the economic downturn can cause anxiety, stress, and depression, with the subsequent loss of social status and relationships (23). Two related psychological theories view increased levels of alcohol consumption and the incidence of alcohol-related health problems as crises-triggered consequences. The “stress-response-dampening theory” posits that people consume more alcohol to reduce the intensity of their response to anxiety and stress, and suffer a higher incidence of alcohol-related health problems (24, 26).

It is known that substance abuse can also lead to death, and this has been observed in some researches that have also highlighted the use of alcohol and other substances of abuse in people subjected to stress (27).

The “self-medication theory” suggests that during an economic recession, high levels of alcohol consumption can lead to the development of dependency in certain people (28, 29).

Regarding smoking habits, a clear reduction has been recorded, which certainly is a boon for the health of the smokers. However, this reduction may not represent a long-term personal choice for a healthier lifestyle, but may be due to the inability to afford tobacco products. Other studies reported that during a period of economic crisis, the high price of cigarettes may deter some people from starting to smoke, or may cause others to give up smoking, and this may be interpreted to show that an economic crisis may lead to improvements in health (30-32).

The MANSA results indicate a population characterized by a lack of fulfillment, with respect to the current economic situation. The data on the level of satisfaction regarding finances and work confirm the pressure triggered by the economic downturn on the population of questionnaire respondents. This pressure emerges in the comparison between the results for the Fabriano area and the Civitanova Marche area, in reference to the different levels of economic recession. Considering previous epidemiological surveys, showing that 30.0% of youth reported alcohol consumption in the pre-crisis period, the 29.0% increase recorded in our study becomes very interesting, especially in relation to possible health problems linked to the onset of severe pathologies. In contrast, the percentage of young people who smoke (38.0%) has remained unvaried in the post-crisis period, compared to that reported in previous studies (33-35). The observation that the percentage of young smokers has not increased could be interpreted as a positive outcome. On the other hand, this stabilization of an unhealthy lifestyle choice could also be viewed as a risk for the population.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. The Financial Crisis and Global Health: Background Paper for WHO High Level Consultation. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stuckler D. Basu S. Suhrcke M. Coutts A. McKee M. The public health effect of economic crises and alternative policy responses in Europe: an empirical analysis. Lancet. 2009;374:315–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Goeij MC. Suhrcke M. Toffolutti V. van de Mheen D. Schoenmakers TM. Kunst AE. How economic crises affect alcohol consumption and alcohol-related health problems: a realist systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2015;131:131–46. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Signorelli C. Capolongo S. Buffoli M. Capasso L. Faggioli A. Moscato U. Oberti I. Petronio MG. D’Alessandro D. Italian Society of Hygiene (SItI) recommendation for a healthy, safe and sustainable housing. Epidem Prev. 2016;40(3-4):265–270. doi: 10.19191/EP16.3-4.P265.094. doi: 10.19191/EP16.3-4.P265.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spacilova L. Petrelli F. Grappasonni I. Scuri S. Health care system in the Czech Republic. Annali di igiene: medicina preventiva e di comunità. 2007;19(6):573–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Signorelli C. Odone A. Gozzini A. Petrelli F. Tirani M. Zangrandi A. Zoni R. Florindo N. The missed constitutional reform and its possible impact on the sustainability of the italian national health service. Acta Biomed. 2017;88(1):91–94. doi: 10.23750/abm.v88i1.6408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siracusa M. Grappasonni I. Petrelli F. The pharmaceutical care and the rejected constitutional reform: what might have been and what is. Acta Biomed. 2017;88(3):352–59. doi: 10.23750/abm.v%vi%i.6376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ricci G. Pirillo I. Tomassoni D. Sirignano A. Grappasonni I. Metabolic syndrome, hypertension, and nervous system injury: Epidemiological correlates. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2017;39(1):8–16. doi: 10.1080/10641963.2016.1210629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thern E. De Munter J. Hemmingsson T. Rasmussen F. Long-term effects of jouth unemployment on mental health: does an economic crisis make a difference? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71:344–49. doi: 10.1136/jech-2016-208012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmad S. Franz GA. Raising taxes to reduce smoking prevalences in the US. Public Health. 2008;122:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buggink JW. de Goeij MC. Otten F. Kunst AE. Changes between pre-crisis and crisis period in socioeconomic inequalities in health and stimulant use in Netherlands. European Journal of Public health. 2016;26(5):772–77. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckw016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kračmarová L. Klusoňová H. Petrelli F. Grappasonni I. Tobacco, alcohol and illegal substances: Experiences and attitudes among Italian university students. Revista da Associacao Medica Brasileira. 2011;57(5):523–28. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302011000500009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrelli F. Pellegrini MG. Grappasonni I. Cocchioni M. Young people and smoking knowledge and habits of middle and high school students. Igiene Moderna. 2000;113(5):425–37. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spáčilová L. Klusoňová H. Petrelli F. Signorelli C. Visnovsky P. Grappasonni I. Substance use and knowledge among Italian high school students. Biomedical Papers. 2009;153(2):163–68. doi: 10.5507/bp.2009.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spáčilová L. Málková E. Hajská M. Klusoňová H. Grappasonni I. Petrelli F. Višňovský P. Epidemiology of addictive substances: Comparison of Czech and Italian university students’ experiencies. Chemicke Listy. 2007;101(14):147–50. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grappasonni I. Marconi D. Mazzucchi F. Petrelli F. Scuri S. Amenta F. Survey on food hygiene knowledge on board ships. International maritime health. 2013;64(3):160–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grappasonni I. Petrelli F. Scuri S. Mahdi SS. Sibilio F. Amenta F. Knowledge and attitudes on food hygiene among food services staff on board ships. Ann Ig. 2018;30(2):162–67. doi: 10.7416/ai.2018.2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scuri S. Tesauro M. Petrelli F. Peroni A. Kracmarova L. Grappasonni I. Consequences in changed food choices and food-related lifestyle decisions. Ann Ig. 2018;30:173–79. doi: 10.7416/ai.2018.2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grappasonni I. Petrelli F. Klusoňová H. Kračmarová L. Level of understanding of medical terms among italian students. Ceska a Slovenska farmacie : casopis Ceske farmaceuticke spolecnosti a Slovenske farmaceuticke spolecnosti. 2016;65(6):216–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Priebe S. Huxley P. Knight S. Evans S. Application and results of the Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA) Int J Psychiatry. 1999;45:7–12. doi: 10.1177/002076409904500102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grappasonni I. Petrelli F. Traini E. Grifantini G. Mari M. Signorelli C. Psychological symptoms and quality of life among the population of L’Aquila’s “new towns” after the 2009 earthquake. Epidemiology Biostatistics and Public Health Volume. 2017;14(2):116901–13. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Priebe S. Grappasonni I. Mari M. Dewey M. Petrelli F. Costa A. Posttraumatic stress disorder six months after an earthquake. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2009;44(5):393–97. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0441-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wahlbeck K. McDaid D. Actions to alleviate the mental health impact of the economic crisis. World Psychiatry. 2012;11:139–45. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2012.tb00114.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sayette M. A. Does drinking reduce stress? Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23(4):250–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sher KJ. Bartholow B.D. Peuser K. Erickson D.J. Wood M.D. Stress response-dampening effects of alcohol: attention as a mediator and moderator. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116(2):362–77. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sher KJ. Levenson R.W. Risk for alcoholism and individual differences in the stress-response-dampening effect of alcohol. J Abnorm Psychol. 1982;91(5):350–67. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.91.5.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grappasonni I. Petrelli F. Amenta F. Deaths on board ships assisted by the Centro Internazionale Radio Medico in the last 25 years. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2012 Jul;10(4):186–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bolton JM. Robinson J. Sareen J. Self-medication of mood disorders with alcohol and drugs in the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Affect Disord. 2009;115(3):367–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):231–44. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Catalano R. Bellows B. Commentary: If economic expansion threatens public health, should epidemiologists recommend recession? International Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;34:1212–13. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sajjad Ahmada. Gregor A. Franzb. Raising taxes to reduce smoking prevalence in the US: A simulation of the anticipated health and economic impacts. Public Health. 2008;122:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tangcharoensathien V. Harnvoravongchai P. Pitayarangsarit S. Kasemsup V. Health impacts of rapid economic changes in Thailand. Social Science & Medicin. 2000;51:789–807. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cocchioni M. Grappasonni I. Petrelli F. Troiani P. Pellegrini MG. Consumption, attitudes and knowledge on compared alcoholic beverages among high school and university students. Annali di Igiene: medicina preventiva e di comunità. 1997;9(1):89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petrelli F. Grappasonni I. Bernardini C. Nacciarriti L. Cocchioni M. Knowledge and consumption of psychoactive substances in middle-school, high-school and university students. Igiene Moderna. 1998;109(2):207–21. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grappasonni I. Petrelli F. Nacciarriti L. Cocchioni M. Young people and drug: distress or new style? Epidemiological survey among an Italian student population. Annali di Igiene: medicina preventiva e di comunità. 2003;15(6):1027–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]