Abstract

Background and aim: In the words of one observer, one of the many effects of the economic downturn has been a “health system shock” marked by reductions in the availability of healthcare resources and increases in the demand for health services. The financial situation influences negatively the low-income family groups, particularly those who normally use the government provided primary prevention services. The goal of this study was to assess the impact of the global recession on the use of medicines and medical investigation recession in different areas of the Marche Region. Methods: An anonymous questionnaire prepared by the National Institute of Statistics, modified and validated by the University of Camerino, has been distributed to junior highschool students of Central Italy to provide a statistically representative sample of families. The questionnaire has been administered in 2016-2017. Results: This article examines the results about healthcare habits, specifically, regarding medicines and medical examinations. Data obtained emphasize a reduction in the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The parents category showed the higher change in medicines use (72.9%). Comparing the data of the Fabriano area with that of the Civitanova Marche area, Fabriano reported a greater reduction in the frequency of taking medicine. Concerning the medical examinations, half of the respondents (62.5%), indicated that they and their family members have regular medical check-up. Conclusions: Respondents who admitted that the economic crisis had reduced their quality of life indicated that the parents were the ones who had experienced the greatest change. This is confirmed by the information on the reduced frequency of medicine use, which affected the parents more than the children, whom they sought to protect and safeguard the most. This reduction was most marked in the Fabriano area. In contrast, in the Civitanova Marche area, with different socioeconomic characteristics, an increase in the use of all the categories of medicines was reported. Concerning visits the situation in the Marche Region appears encouraging. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: economic crisis, medications, medical care, lifestyles, prevention, drugs

Introduction

In the words of one observer, one of the many effects of the economic downturn has been a “health system shock” marked by reductions in the availability of healthcare resources and increases in the demand for health services (1, 2).

Some European countries, such as Italy, have introduced extra charges for some health services previously covered by the National Healthcare System (NHS), and have cut expenditures on healthcare in order to reduce the deficit generated by the economic crisis (3-6).

The financial situation influences negatively the low-income family groups, particularly those who normally use the government provided primary prevention services. Therefore, in forcing governments to reduce the availability of preventive medicine, the economic downturn may have deleterious effects on the health of the population (7).

Some European countries have sought to reduce these effects by improving timely access to services, particularly those for priority groups and specific diagnostic-therapeutic pathways. Other measures include direct purchase of extra visits and tests from private providers by local healthcare units, the activation of central booking centers, the imposition of penalties for patients who do not keep appointments, and demanding that users pay for services prior to accessing care (introduced with the NHS) (8).

Studies have demonstrated a direct relationship between unemployment and attention to one’s state of health. Some scholars have indicated that a steady income serves as a positive proxy for the family and a positive environmental determinant for the health of young people (9, 11).

It is well known that the social distances (income inequality) within a population produce a “gradient effect” on the health of individuals. In fact, in societies characterized by a “steep gradient” of economic inequality, the overall level of health and well-being is lower than that in societies where the differences are less pronounced.

The negative influence of income inequality is much more severe if we consider that the state of health encompasses a wide variety of physical, cognitive, emotional, behavioral, educational, occupational and mental outcomes. Therefore, the economic downturn and unemployment are elements that may increase the “gradient effect” on the health of the population and stop “the development of health”; which describes the trend within a population of all the outcomes related to a good state of health (12, 13).

The economic crisis has affected not only access to healthcare, but also the use of medicines. After the global recession, the World Health Organization (WHO) investigated the impact of the global economic crisis on the pharmaceutical sector. The largest changes, on the medicines consumption, were noted in high income countries and Europe, but no distinction was observed between the decrease in medicines for acute and chronic pathologies (14, 15), nor did any shift from licensed brands to other brands or generic medicines emerge (16). The goal of this study was to assess the impact of the global recession on the use of medicines looking a representative sample of the population in our region. A secondary objective was to investigate which medicines were affected the most and the least by the recession in areas of the Marche Region that have suffered particularly from the economic downturn, and to identify changes that may have occurred in the frequency with which families avail themselves of the services of physicians, pharmacists and dentists.

Methods

In the period 2016-2017, an anonymous questionnaire prepared by the National Institute of Statistics, modified and validated by the University of Camerino, Pharmacy and Health Products School, was distributed in the cities of Camerino, Fabriano, and Civitanova Marche, in the Marche region (Italy), which represent a cross section of regional social, economic and cultural realities. The sample is representative, owing to the fact that since the questionnaire was distributed among students in compulsory schools (lower level secondary school), we were able to reach all types of families, irrespective of their social, economic or cultural status.

The questionnaire validity was tested by administering it to 15 people of different social/economical and cultural status to value the ‘face validity’. The investigators briefly explained the aim of the survey and obtained written consent before each interview. The study was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration. The questionnaire was administered to middle school students to provide a statistically representative sample of families in the geographic area served by the University of Camerino. The questionnaire consisted of five sections: “Social and anagraphic data”, “Change of the style of life” ( physical activity, consumption of alcohol, smoking, consumption of drugs and the use of medicines and visits to family doctors and specialists)“Change in eating habits” (regarding the amount of food products bought, the type of stores and the general variation of purchases observed with the increase of prices), “Details of consumption” (how food consumption changed in relation to specific food categories) (17, 18), “The psychological profile of the subjects” (the level of satisfaction with one’s personal life) (19).

The data were processed using an Excel Workbook (Microsoft Office), and analyzed using SPSS 20 (SPSS Inc); the Chi-square Test (p<0.005) was used to examine possible relationship.

Results

This article examines the results about healthcare habits, specifically, regarding medicines and medical examinations. 880 people answered, corresponding to a 47.3 % of the total number of questionnaires distributed. The sample was composed by 310 males (35.2%) and 570 females (64.8%). The average age ranged from 41 to 50 (57.2%) and 52.5% of sample has a high school qualification.

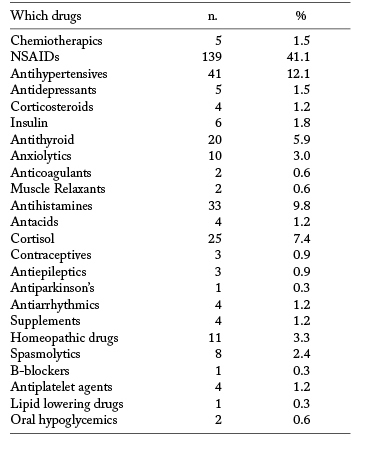

Table 1 summarizes the classes of drugs taken by the respondent and other members of the household (20).

Table 1.

The percentage of household members who take drugs.

The drug category with the most marked reduction was that of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The use of antidepressants and anxiolytics was also reduced, though to a lesser degree (21). Respondents reported that the most significant reductions were for medications prescribed by the family doctor or specialists.

To the question “Has your family’s use of medicines changed?” 152 (17.2%) answered yes, 709 (80.5%) answered no, and 20 (2.3%) did not answer.

Specifically, for 72.9% of parents, their medicine use had changed, while this was the case for only 13.2% of children. Asked “How has your frequency of medicine use changed?”, 47.0% indicated increased frequency, and 20.5% reported reduced frequency. Among those for whom there was an increased frequency of medicine use, 81.7% were parents and 18.3% were children, while among those who had reduced the frequency, 83.9% were parents, and 18.3% were children.

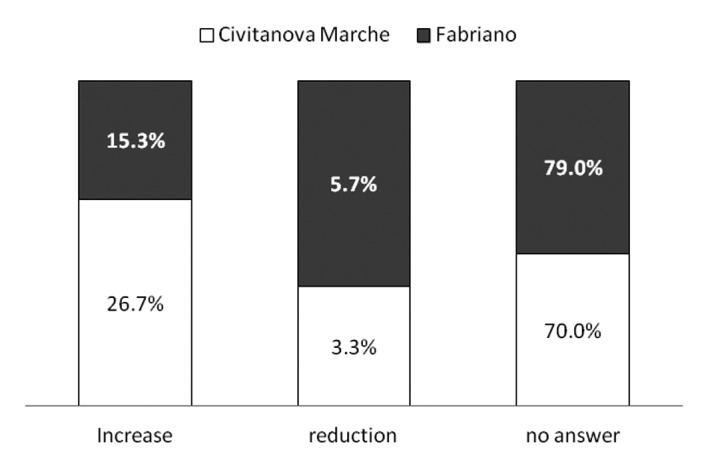

Comparing the data of the Fabriano area with that of the Civitanova Marche area, an increase in the frequency of taking medicine was noted for the Civitanova Marche population. This area was less affected by the economic recession, and its level of industrialization has remained good, as businesses here have proven more successful at adapting to socio-economic changes. Respondents from the Fabriano area, instead, reported a greater reduction in the frequency of taking medicine (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Increased and decreased frequency of taking medicines: Fabriano and Civitanova Marche areas

As can be noted from the figure 1, the great majority of respondents chose not to answer the question about “How frequency consumption in the family changed”, even though they answered the question about the change in medicine use in the post-crisis period.

Almost a half of respondents (39.9%) reported taking a medication recommended by a physician (GP or specialist). In 7.6% of the cases, respondents preferred to ask friends or other family members for advice on medications, rather than consulting a doctor or pharmacist (this percentage was actually 15.4% of the subjects who responded to the question) (p<0.05). It is also dismaying that only 1.0% of respondents asked for advice on medication from a pharmacist, significantly fewer than those who sought advice from a friend or family member (p<0.05). The majority of respondents (51.5%) did not provide an answer to the question.

Over half of the respondents (550 people, 62.5%), indicated that they and their family members have regular medical check-ups. The 79.9% see their family doctor or a specialist with some regularity. Only 341 (38.5%) subjects indicated that they and their family members, visit a dentist periodically. The most frequent reasons for a doctor’s appointment were respiratory diseases (20.0%), cephalea (19.8%), and hypertension (16.0%), anxiety (6.8%) and gastric ulcer (6.5%). .

Discussion

As mentioned above, the sample group was surveyed in order to determine whether the economic crisis had affected how attentive respondents are to their health and that of their family.

It may be that family habits reflect a level of “lifestyle carelessness” that bears on the life of the children. In fact, in particularly critical situations such as those provoked by an economic crisis, youth are the sector of the population most vulnerable to rapid changes in lifestyle that may lead to incorrect lifestyles potentially harmful for their health, such as use of medicines without consultation of a physician or pharmacist (22-25).

In particular, we examined the use of medications, the attention to consultations and appointments with family doctors and specialists. The results regarding medicine usage are more contained then European situation. For example, our respondents indicated a quite low use of psychotropic and anxiolytic drugs, unlike the situation in Spain (26). However, a substantial number of respondents with potential psychiatric disturbances were identified in our survey. This is a worrisome observation, given this phase of an economic crisis in which one’s psychological equilibrium can be put hard to the test.

Concerning the use of medications an incorrect habit has been highlighted: our data show that 15% of subjects who responded to the question about consultation with physicians or pharmacists indicated that they choose pharmaceutical products based on the recommendation of a family member or a friend, not of an expert. This may be due to mistrust of healthcare professionals and a tendency to seek an easier and less expensive solution than the one professionals would advise, which instead sometimes demand expensive or psychologically difficult diagnostic procedures, tests, and treatment regimes.

The category of NSAIDs is the one with the greatest reduction in use. This may be because families that have borne the brunt of the economic crisis may have chosen to reduce widely used drugs that are specific for certain pathologies.

More specifically, respondents who admitted that the economic crisis had reduced their quality of life indicated that the parents were the ones who had experienced the greatest change. This is confirmed by the information on the reduced frequency of medicine use, which affected the parents more than the children, whom they sought to protect and safeguard the most. This reduction was most marked in the Fabriano area. In contrast, in the Civitanova Marche area an important reduction in the use of all the categories of medicines has not been registered. A possible explanation could be given by data on unemployment which can be found on the two websites we consulted. Unsurprisingly, data referring to unemployment in the areas of Fabriano and Civitanova Marche shows youth unemployment figures in Fabriano of over 30%. Employment figures for Fabriano are equal to 36.6%, compared to Civitanova’s at 41.8%.

The same can be said, even though percentages are smaller, for figures relating to women and men; the employment rate for women in the Fabriano area stands at 39.6% compared to 40% in Civitanova Marche; for men, we are looking at 54.6% compared to 58.0% in Civitanova Marche. Furthermore, a comparison of data for youth employment rates and long-term unemployment in the city of Fabriano with figures for the Marche Region, shows a reduction of 4.7% for both values (27). This evidence is reinforced by data recorded by the Job Centre in Fabriano for the period from 2010 to 2016 on the population aged 14 – 65. These data push unemployment rates over 50%, with over 5 thousand jobless in the city of Fabriano alone; an average which is well above the national figure. On the contrary, job centres in Civitanova Marche recorded a 57.1% drop in job seekers starting from 2014 (28).

Our research reveals less alarming data for access to GP and specialist medical appointments, relating to prescriptions for therapies or specialist prescriptions.

Concerning visits to the family doctor or a specialist, working on the assumption that ¼ of those who responded to the question had a medical examination with subsequent prescription of a drug for headache or anxiety, generally speaking, there seems to be a normal level of adherence to the therapy prescribed. This may be deduced from the data on visits to a specialist, and the data on specific categories of medication taken.

Instead, if one considers the situation in countries more gravely affected by the economic crisis, such as Greece, the surveys indicates insufficient compliance or even abeyance when expensive medications are prescribed, such as those for cardiovascular diseases (29).

In Italy, the national healthcare system probably deserves credit for this positive difference (universal health care coverage), because in Greece and the most part of European countries healthcare assistance is provided only on the basis of insurance.

Probably, if the Italian public health system were more similar to the one adopted by Greece, it would have meant a reduction in medicines which must be paid for, as well as in GP and specialist appointments, the cost of which would depend fully on the patient.

In countries where social and health policies are based on the principle of equality, the right to health and a decent household income, the social gap is reduced (30, 31).

References

- 1.Mladovsky P. Srivastava D. Cylus J. Karanikolos M. Tamás Evetovits T. Sarah Thomson. Martin McKee. Economic crisis, health systems and health in Europe: impact and implications for policy. World Health Organization. 2012 ISSN 2077-1584; http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/132050 . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Odone A. Landriscina T. Amerio A. Costa G. The impact of the current economic crisis on mental health in Italy: evidence from two representative national surveys. Eur J Public Health. 2017 Dec 27 doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckx220. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckx220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mladovsky P. Srivastava D. Cylus J, et al. Health policy responses to the financial crisis in Europe. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2012. Policy summary 5. (on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spáčilová L. Petrelli F. Grappasonni I. Scuri S. Health care system in the Czech Republic. Annali di igiene : medicina preventiva e di comunità. 2007;19(6):573–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Signorelli C. Odone A. Gozzini A. Petrelli F. Tirani M. Zangrandi A. Zoni R. Florindo N. The missed constitutional reform and its possible impact on the sustainability of the italian national health service. 2017;88(1):91–94. doi: 10.23750/abm.v88i1.6408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siracusa M. Grappasonni I. Petrelli F. The pharmaceutical care and the rejected constitutional reform: what might have been and what is. Acta Biomed. 2017;88(3):352–59. doi: 10.23750/abm.v%vi%i.6376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gemmill MC. Thomson S. Mossialos E. What impact do prescription drug charges have on effi ciency and equity? Evidence from high income countries. Int J Equity Health. 2008;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maresso A. Mladovsky P. Thomson S. Sagan A. Karanikolos M. Richardson E. Cylus J. Evetovits T. Figueras JM. Kluge H. Copenhagen (Denmark): European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2015. Economic crisis, health systems and health in Europe: Country experience. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Rijn RM. Robroek SJW. Brouwer S. Burdorf A. Influence of poor health on exit from paid employment: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2014;71:295–301. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2013-101591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larson K. Halfon AEN. Family Income Gradients in the Health and Health Care Access of US Children. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14:332–342. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0477-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cocchioni M. Grappasonni I. Petrelli F. Troiani P. Pellegrini MG. Consumption, attitudes and knowledge on compared alcoholic beverages among high school and university students. Ann Ig. 1997;9(1):89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Junek WMD. Developmental Health and the Wealth of Nations: Social, Biological and Educational Dynamics. Can Child Adolesc Psychiatr Rev. 2003 Feb;12(1):26–27. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrelli F. Contratti CM. Tanzi E. Grappasonni I. Vaccine hesitancy, a public health problem. Ann Ig. 2018;30(2):86–103. doi: 10.7416/ai.2018.2200. doi: 10.7416/ai.2018.2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ricci G. Pirillo I. Tomassoni D. Sirignano A. Grappasonni I. Metabolic syndrome, hypertension, and nervous system injury: Epidemiological correlates. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2017;39(1):8–16. doi: 10.1080/10641963.2016.1210629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grappasonni I. Petrelli F. Amenta F. Deaths on board ships assisted by the Centro Internazionale Radio Medico in the last 25 years. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2012;10(4):186–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buysse I.M. Impact of the economic recession on the pharmaceutical sector. Utrecht University, WHO CC for Pharmacoepidemiology& Pharmaceutical Policy Analysis. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grappasonni I. Marconi D. Mazzucchi F. Petrelli F. Scuri S. Amenta F. Survey on food hygiene knowledge on board ships. International maritime health. 2013;64(3):160–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grappasonni I. Petrelli F. Scuri S. Mahdi SS. Sibilio F. Amenta F. Knowledge and attitudes on food hygiene among food services staff on board ships. Ann Ig. 2018;30(2):162–67. doi: 10.7416/ai.2018.2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scuri S. Tesauro M. Petrelli F. Peroni A. Kracmarova I. Grappasonni I. Implications of modified food choices and food-related lifestyles following the economic crisis in the Marche Region of Italy. Ann Ig. 2018;30:173–72. doi: 10.7416/ai.2018.2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grappasonni I. Petrelli F. Klusoňová H. Kračmarová L. Level of understanding of medical terms among italian students. Ceska a Slovenska farmacie: casopis Ceske farmaceutiche spolecnosti a Slovenske farmaceuticke spolecnosti. 2016;(6):216–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mignini F. Sabbatini M. Pascucci C. Petrelli F. Grappasonni I. Vanacore N. Pharmaco-epidemiological description of the population of the Marche Region (central Italy) treated with the antipsychotic drug olanzapine. Ann Ist Super Sanità. 2013;49(1):42–9. doi: 10.4415/ANN_13_01_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grappasonni I. Petrelli F. Nacciarriti L. Cocchioni M. Young people and drug: distress or new style? Epidemiological survey among an Italian student population. Ann Ig. 2003 Nov-Dec;15(6):1027–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spacilova L. Klusonova H. Petrelli F. Signorelli C. Visnovsky P. Grappasonni I. Substance use and knowledge among Italian high school students. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2009;153(2):163–8. doi: 10.5507/bp.2009.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siracusa M. Petrelli F. Trade of food supplement: food or drug supplement? Recenti Prog Med. 2016;107(9):465–71. doi: 10.1701/2354.25224. doi: 10.1701/2354.25224. Prog Med 2016; 107(9):465-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kračmarová L. Klusoňová H. Petrelli F. Grappasonni I. Tobacco, alcohol and illegal substances: experiences and attitudes among Italian university students. Rev Assoc Med Bras 1992. 2011;7(5):523–8. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302011000500009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gili M. Roca M. Basu S. McKee M. Stuckler D. The mental health risks of economic crisis in Spain: evidence from primary care centres, 2006 and 2010. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23:103–8. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. http://ottomilacensus.istat.it/

- 28.Montanini F. Canonico M. Paccassoni C. Goffi G. Massaccesi E. Regione Marche: Osservatorio Regionale Mercato del Lavoro; 2005. Rapporto Annuale 2015. www.istruzioneformazionelavoro.marche.it . [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsiligianni IG. Papadokostakis P. Prokopiadou D. Stefanaki I. Tsakountakis N. Lionis C. Impact of the financial crisis on adherence to treatment of a rural population in Crete, Greece. Qual Prim Care. 2015;22:238–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keating D P. Hertzman C. New York: The Guilford Press; 1999. Developmental health and the wealth of nations: Social, biological, and educational dynamics. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mackenbach J P. Stirbu I. Roskam A J. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(23):68–2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0707519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]