Abstract

Background and aim of the work: Procedural pain during Peripheral Venous Catheterization (PVC) is a significant issue for patients. Reducing procedure-induced pain improves the quality of care and reduces patient discomfort. We aimed to compare a non-pharmacological technique (distraction) to anaesthetic cream (EMLA) for the reduction of procedural pain during PVC, in patients undergoing Computerized Tomography (CT) or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) with contrast. Methods: This is a Prospective, Randomized Controlled Trial. The study was carried out during the month of October 2015. A total of 72 patients undergoing PVC were randomly assigned to the experimental group (distraction technique, n=36) or control group (EMLA, n=36). After PVC, pain was evaluated by means of the numeric pain-rating scale (NRS). Pain perception was compared by means of Mann-Whitney Test. Results: The average pain in the distraction group was 0.69 (SD±1.26), with a median value of 0. The average pain in the EMLA group was 1.86 (SD±1.73), with a median value of 2. The study showed a significant improvement from the distraction technique (U=347, p<.001, r=.42) with respect to the local anaesthetic in reducing pain perception. Conclusions/Implication for practice: Distraction is more effective than local anaesthetic in reducing of pain-perception during PVC insertion. This study is one of few comparing the distraction technique to an anaesthetic. It confirms that the practitioner-patient relationship is an important point in nursing assistance, allowing the establishment of trust with the patient and increasing compliance during the treatment process.

Keywords: distraction, fear, peripheral venous catheter, procedural pain perception, local anaesthetic

Background and aim of the work

Procedural pain is a clinical manifestation of intense episodic pain following a therapeutic intervention. This consists of transient exacerbations reaching an intensity peak within a few minutes, against the background of a persistent pain manifestation (1, 2). In everyday clinical practice, many procedures are carried out that cause pain for the patient (3). During any procedure including the use of needles, besides pain reduction, it is fundamental to control fear and stress (4). Fear is the response to a perceived threat that is consciously recognized as a danger (5) and varies along a continuum from “none” or “very little” to a serious fear of needles (6).

A potential risk for patients during painful procedure could be vasovagal response. A vasovagal response consists of the establishment of bradycardia and arterial hypotension, presenting as vertigo, shock, syncope, tonic-clonic seizures, increase in pain sensations, excessive sweating and nausea (4, 7). For this reason, techniques were created for the rapid management of stress and fear (8). Many intervention possibilities, pharmacological or otherwise, decrease pain. Many can concretely help a patient to face and solve their own fear of pain. These techniques can be utilized with adults and can be carried out autonomously or in teams by nursing personnel (9).

Lynn (10) and Goodspeed & Lee (11), highlight the necessity, both for the nurses and for the patient, of adequate room during venepuncture. Adequate room allows space for the patient to lie down during the procedure, can reduce the risk of a vasovagal reaction, and allows for recovery time after the procedure. A peaceful space, where there is no feeling of oppression, would very much help the patient to face the situation with lower anxiety and fear. In addition, such a setting would favour establishing good nurse-patient communication, conducive to creating a positive trust relationship and fear reduction.

In order to reduce perceived pain, some pharmacological techniques are used. In a study carried out by Burke et al. (12), lidocaine 8.4% administered subcutaneously as local anaesthetic, before the introduction of a Peripheral Venous Catheter (PVC), resulted in more effective perceived pain relief than placebo. A systematic review carried out by Eidelman et al., found that the effects of a topically applied mix of lidocaine and prilocaine (Eutectic Mixture of Local Anaesthetics, EMLA) are superimposable with the subcutaneous application of lidocaine (13). The study also stated that using EMLA is preferred since it is less invasive. EMLA is indicated for superficial analgesia of skin in concurrence with superficial surgical interventions, insertion of peripheral venous catheters and for superficial analgesia of genital mucosa (14). In Italy, EMLA is primarily utilized in paediatrics to reduce pain associated with needle insertion. Its’ application is an intervention that can be carried out by the parents or health care professional. Its’ effect is actuated by means of a reversible block of conduction along the nerve fibre paths; the numbing effect extends for some hours after application (14).

As far as non-pharmacological techniques to reduce pain, the pain-free technique is utilized to carry out subcutaneous and intramuscular injections (11). A novel solution described in the literature involves the combination of cold, vibration and distraction. The medical device used for this is called “Buzzy bee” (15). The device is shaped like a bumblebee, vibrates and contains an ice pack. The device is placed a short distance upstream of the venepuncture site, is turned on for the duration of the procedure, and manages to block nervous pain transmission, providing significant relief to the patient.

The Mindful Moist mouth technique maintains that, in order to reduce the bothersome sensation of a dry mouth caused by stress, it is sufficient to chew gum or squeeze the tip of the tongue, thus stimulating saliva production. Another solution is the use of stress balls as a distraction device. However, these devices primarily function to set up adequate breathing, since in times of anxiety and fear, breathing tends to become tachypneic.

The “Three-step progressive muscle relaxation training” behavioural technique is based on the approach of readdressing a person’s attention, trying to let the muscles relax in three areas of the body: feet, knees and hands. Another technique that has the same objective of focusing attention away from the procedure is visualization. The most utilized method is that of geographic visualization, whereby the person is invited to mentally visualize a real or imaginary place that suggests a feeling of calm, tranquillity and safety (16).

Among the non-pharmacological techniques, distraction has been shown to be simple and of immediate application, while requiring no prior training (16,17). Distraction is not a passive strategy oriented to amuse the patient, but it is a way to focus their attention on an alternative stimulus, which allows for the modification of the patients’ sensorial perception. By concentrating on something other than pain, the patient can distance himself from anxiety and fear. Any distraction should be appropriate to the patient’s age and, wherever possible, reflect their interests and preferences (18).

While commonly utilized in paediatrics, such distraction techniques have grown in importance even among adults. This is demonstrated by several studies carried out internationally over the last few years (16, 17, 19-22). The distraction techniques described in the literature are physical exercise, concentration and mental exercise. Various studies have investigated such techniques in paediatrics. MacLaren & Cohen confirm the efficacy of non-pharmacological techniques for the treatment of paediatric-neonatal pain (18). The reduction of anxiety and fear associated with pain, use of appropriate tools, and involvement of parental figures in symptom management are essential therapeutic elements that must always be integrated with medication strategies.

The aim of this study is to compare the effectiveness of non-pharmacological techniques (distraction) to pharmacological anaesthetic cream (EMLA) for reduction of procedural pain resulting from the insertion of a peripheral venous catheter in adult patients undergoing Computerized Tomography (CT) or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) with contrast.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a monocentric, randomized, open-Label, clinical trial. For trial management, data elaboration and presentation, the CONSORT guidelines for reporting of randomized parallel groups trials were followed (23).

Primary Outcome

Evaluating the reduction of pain perception when inserting a PVC in participants undergoing NMR and CT with contrast, possibly achieved by means of the distraction technique.

Secondary Outcome

Evaluating the correlation between fear and pain when positioning the PVC, in participants undergoing NMR and CT with contrast.

Participants

The participants involved in the study were people undergoing NMR and CT with contrast, not admitted to hospital and accessing the Complex Operating Unit of Radio-Diagnostics of the Teaching Hospital Luigi Sacco in Milan.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The selection of the participants followed specific inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria:

People aged 18 or over.

Capacity to sign the informed consent in compliance with good clinical practices and current national laws.

Outpatients and day patients.

Exclusion criteria:

People with cognitive impairment.

People unable to read and understand Italian.

Hypersensitivity to the active ingredients or any excipients in EMLA.

Congenital or idiopathic methemoglobinemia (contraindication to EMLA use).

Sample Size

Based on the results of a prior study (17), the hypothesis was derived that patients treated by means of the distraction technique would have an average pain score of 1.5±1.2 as compared to patients without distraction but with EMLA, for which an average pain score of 3.3±2.0 was hypothesized. With an Alpha level of 5% and a power of 90%, it was necessary to analyse 27 people per group. Considering the possibility of participant drop-out, the sample size was increased by 30%, thus bringing the total number to 72.

Recruitment

The study was carried out during the month of October 2015. All participants were recruited by one author (BI), who also collected all data. In the waiting room of the Radiology Operating Unit, the author explained the study aims, as well as the two main interventions characterizing it and collected written informed consent. Once consent was obtained, the patient was randomly assigned to a treatment group as detailed below. Participant recruitment and PVC insertion occurred in separate rooms.

Randomization

Randomization was carried out by means of the blocks method, with blocks of 6. The randomization list was maintained in closed opaque envelopes. Envelopes were opened by the practitioner who performed the PVC after the participant had been declared suitable and informed consent was received. The randomization list was created online by means of specific software (https://www.sealedenvelope.com/simple-randomiser/v1/lists). The person who collected the data (BI) was blind to the randomization and therefore did not know its content.

Location

The Radiology Division of the Hospital where the study was carried out supplies over 150 types of different radiological services. Specific competencies are present in diagnostic characterization of diffuse infiltrating pulmonary diseases, mammary pathology, pathology of AIDS, newborn’s congenital dysplasia, chronic Inflammatory bowel disease and treatment of hepatic primitive tumours by TACE (Trans Arterial Chemo Embolization). The site was chosen due to the number of users accessing the radio-diagnostic services and making use of contrast, which clearly requires PVC insertion. These participants were outpatients.

Procedure

Experimental intervention

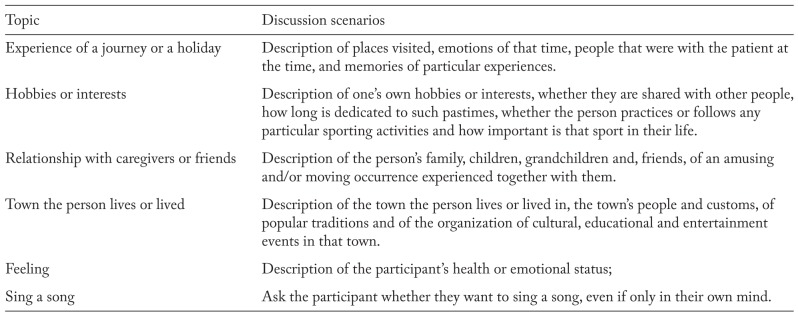

The distraction technique consisted of formulating simple questions on different subjects (Table 1), with the possibility to give a free and articulated answer, thus distracting the participant from the invasive procedure in progress.

Table 1.

Example of distraction topics utilized (Andrews & Shaw, 2010)

A guideline that the person tasked with collecting the data would have to follow was formalized in order to formulate questions. At the end of the procedure, the nurse asked the person to grade, in accordance with the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), the pain perceived during the procedure.

Control intervention

Control intervention consists of the application of EMLA cream, which is the most frequently recommended medicinal analgesic during venepuncture (24). Participants were randomised into the control group. The cream was applied by means of a pressure dressing for 15 minutes at the venepuncture site, in compliance with the therapeutic indications of the local anaesthetic (25). Carrying out the rest of the procedure corresponded with the current procedures mandated in the operating unit where the study was carried out.

Instruments

Procedural pain was evaluated by means of the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS). This measure was carried out immediately after the PVC insertion (12). Post-consent and prior to PVC, the patient was evaluated with respect to venepuncture fear by means of the Visual Analogue Fear Scale (VAFS)(26,27). All data collection cards were guarded by the authors in a room accessible only to them.

Data Analysys

The data were collected in an Excel worksheet and described as numbers and percentages if qualitative, and by mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range (where appropriate), if quantitative. Normal distribution for continuous variables was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The continuous variables in the two groups were compared by means of Student’s t-test if normally distributed; categorical variables were compared instead using Pearson’s chi-square test. In case of non-normal distribution, the comparisons between the two groups were carried out by means of the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. The correlation was evaluated between fear level and pain level in the two groups, by determining Spearman’s Rho coefficient. For all statistical analyses, a significance threshold was considered as p value<0.05. Data analysis was carried out in accordance with intention to treat. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS® version 21.0 (Chicago, IL, USA) (28).

Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Teaching Hospital Luigi Sacco in Milan (Protocol no. 0019382 of 27 July 2015). Written Informed Consent was obtained from all patients included in the study, before their registration and group assignment. The study was conducted in compliance with the Helsinki declaration and with the current Italian legislation on privacy (29).

Results

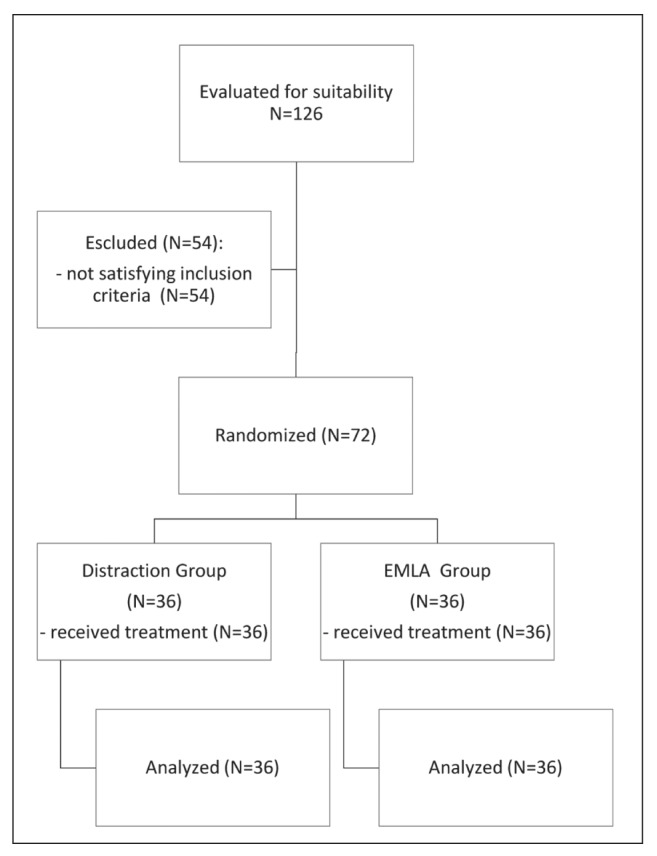

The sample was composed of 72 participants conforming to the inclusion criteria, chosen from 126 evaluated subjects. There were no dropouts from either group (Figure 1) and each patient was analysed in the assigned group, by means intention to treat analysis.

Figure 1.

Randomization Flow Chart (Consort, 2010)

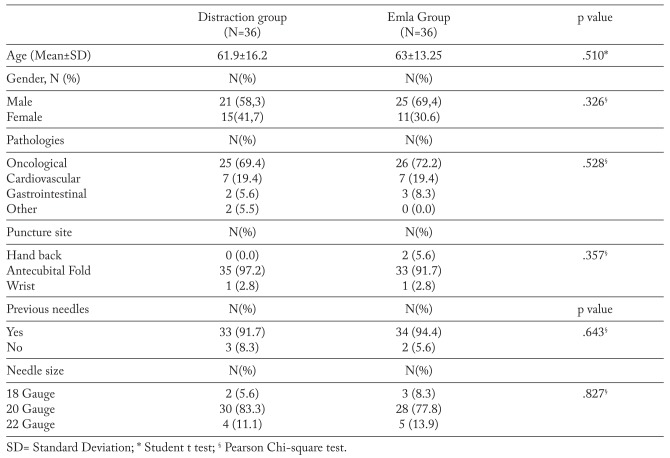

The average age of the distraction group was 61.9±16.2 years and 63.0±13.25 years in the EMLA group. Data analyses indicated the presence of 46 males and 26 females. 21 males (58.3%) and 15 females (41.7%) were assigned to the treated group, 25 males (69.4%) and 11 females (30.6%) to the control group. The majority of the people suffered from oncological pathologies. In addition, seven people were recognized as suffering from cardiovascular illnesses (19.4%) for both sub-samples, two from gastrointestinal pathologies (5.6%) in the treatment group and three (8.3%) in the EMLA group and finally, two people (5.5%) in the treatment group suffered from other pathologies. The most frequent venepuncture site was the antecubital area (basilic or median veins), where 68 PVC (94%) were positioned. Two PVC (3%) were inserted in the dorsal metacarpal veins and as many in the wrist area (cephalic vein).

In the treatment group the antecubital fold was chosen as the puncture site in 35 cases (97.2%), while the wrist was used only once (2.8%). In the EMLA group: the elbow fold was chosen in 33 assisted people (91.7%), the back of the hand in two cases (5.6%) and the wrist in just one case (2.8%). The venepuncture site displayed no significant difference between the two groups (p=-.357).

The majority of subjects in both groups had previously had needles inserted (91.7% in the treatment group and 94.4% in the control group). This result was not significantly different between the two groups (p=.643), neither was the gauge of the needle used (p=.827).The two populations were superimposable for the main defining characteristics at the beginning of the study (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients included, venepuncture site and needle size

Before inserting the peripheral venous catheter, participants were asked to rate their own fear level regarding the PVC insertion using the VAFS. The maximum fear level was 10 and the minimum 0. Statistical analysis showed no significant difference in fear level between the two groups (Distraction Group: Median=1, First Quartile=0; Third quartile=5, IQR=5; EMLA Group Median=0, First Quartile=0; Third quartile=2, IQR=2; U=532, p=0.156, r=.17).

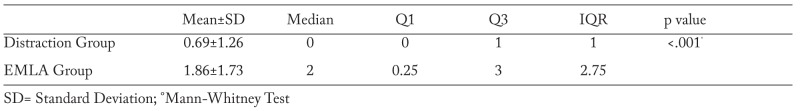

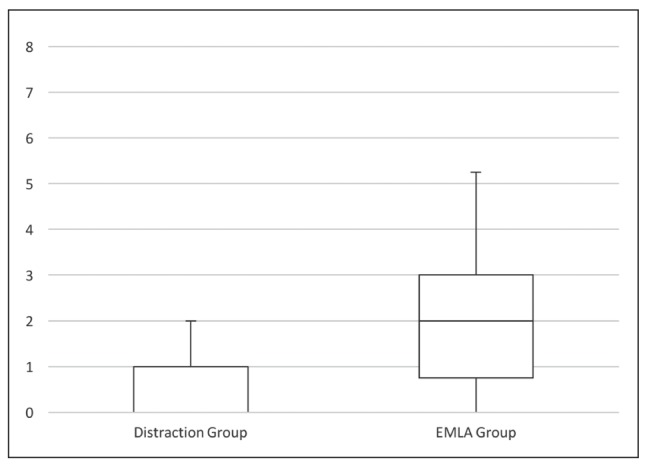

After PVC insertion, pain was measured by means of the NRS. Values for the distraction group ranged between 0 and 2 with a median of 0 In comparison the EMLA group range was wider, 0-5.25 with a median of 2 (U=347, p<.001, r=.42) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pain level after venepuncture

Thus, the distraction technique resulted in a significant improvement in reducing procedural pain in comparison to the control, as showed also in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Pain perception in the two groups (Numeric Rating Scale=0 to 10)

We found a moderate, but significant correlation between fear and pain, with an rs (72)=.247 (p=.037). As observed previously, fear levels were uniform between the two groups. Therefore, participants’ fear from previous experiences did not influence pain perception during PVC insertion.

Discussion

Despite the lack of directly comparable studies, the present study is relatable to Mutti, et al. who investigated the decrease of procedural pain by means of the distraction technique, without a specific intervention as control (17). Results from the primary objective suggest that the distraction technique is not only more functional and non-invasive, but also cheaper, since its cost is zero. Furthermore, the technique has no side effects, as a medication might, and can be utilized with any patient. Distraction is a powerful non-pharmacological technique that is simple and immediately applicable and requires no special training (16, 17). As stated in the background, by concentrating on something other than pain, the patient can distance himself from anxiety and fear. This should also influence physiological reaction to fear and anxiety, reducing breath and heart rate and preventing vasovagal response. The open questions used to distract the patient’s attention away from pain further serve the development of a positive relationship between nurse and patient (16, 17). Such a relationship can become essential in the patient’s compliance with a specified treatment plan. It has been shown previously that the practitioner-patient relationship is pivotal in the treatment process (16, 17). Here we show that the distraction group median was 0 on the NRS scale and the EMLA group had a median of two (U=347, p<.001, r=.42). These findings support those previously published and highlight the superiority of the distraction technique to either no-treatment or pharmacological treatment. Consistent with WHO Guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of persistent pain in children suffering from serious pathologies (30), this study confirms that acting on the multi-factorial dimensions of pain (emotional, behavioural and cognitive), can influence a patients’ pain perception. Studies by Lotto & Alberio (7) and by Zengin, et al. (4), state that there is a correlation between fear and increased perception of pain sensations. The perceived fear level varies depending on the environment and of the procedure being carried out (4). The current study was carried out in an outpatient treatment setting, while the Zengin, et al. (4) study was conducted in the operating room. As argued by Zengin, et al. (4), the fear level shown by a person about to undergo a surgical intervention is higher than that of a person undergoing a less invasive procedure in an outpatient care context. This may explain the different correlation between fear and pain found in the two studies. Zengin, et al. (4), observed a strong correlation between the two phenomena, while we observed only a weak correlation between the two (rs(72)=.247; p=.037).

The present study has some limitations that should be considered. Firstly, it is monocentric and involved outpatients. Secondly, since it is an open-label study, a possible detection bias should be considered. Finally, we didn’t evaluate if the effectiveness of the intervention varies because of the questions provided. The results therefore, should be considered in light of these aspects that could reduce their external validity. Despite these limitations, the distraction technique showed a promising effectiveness in the reduction of pain during PVC insertion.

Conclusions

Standard approaches to the reduction of procedural pain perception in adults vary widely depending on the individual practitioner. Due to the ease of application, our study suggests that the distraction technique can be employed anywhere painful procedures are enacted. The distraction technique in the present study was more effective than a pharmacological intervention in decreasing procedural pain during the insertion of a peripheral venous catheter.

Future research

Considering the results of the present study, it is interesting to evaluate the application to other pain-inducing interventions, such as: venous or arterial blood sampling, insertion of urinary catheter, mobilization, dressing change. It would also be useful in future, to compare among themselves different types of distraction, in order to evaluate the possible existence of different degrees of effectiveness among them, or to verify their efficacy in relation to the type of population on which they are used. In regard to the correlation between needle fear and pain, there are few studies comparing these phenomena in different environments, such as outpatient care, home care, hospital admission or operating theatre. In view of the scarcity observed in the literature, this could be a starting point for future research.

Relevance for clinical practice

This study confirms the practitioner-patient relationship is an important point in nursing assistance, allowing the establishment of trust with the patient and increasing compliance during the treatment process. The present study is one of few comparing the distraction technique to an anaesthetic (31); therefore it constitutes a starting point for further investigations with the benefit of being inexpensive and applicable to all. Finally, this study confirms that patients reporting fear of needles have, at some time in the past, been subjected to a painful experience, without adequate intervention on the part of health professionals. Therefore, we believe that, by using appropriate techniques to decrease perceived pain, it will be possible to prevent the development of future phobias, in addition to reducing the distress experienced in the course of the procedure.

References

- 1.Smith H. A comprehensive review of rapid-onset opioids for breakthrough pain. CNS Drugs. 2012;26:509–35. doi: 10.2165/11630580-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Testa A, Bonetti C, Berretoni R, di Filippantonio S, Orsini P, Marinangeli F. Il dolore procedurale [Procedural pain] Pain Nursing Magazine Italian Online Journal. 2014 Available from: http://www.painnursing.it/comunicazione-breve/il-dolore-procedurale . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lang EV, Tan G, Amihai I, Jensen MJ. Analyzing acute procedural pain in clinical trials. Pain. 2014;155:1365–73. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zengin S, Kabul S, Al B, Sarcan S, Dogan M, Yildirim C. Effects of music therapy on pain and anxiety in patients undergoing port catheter placement procedure. Complement Ther Med. 2013;21:16–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carpenito LJ. Manuale tascabile delle diagnosi infermieristiche [Pocket manual of Nursing Techniques] Milan: Casa Editrice Ambrosiana; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taddio A, McMurtry CM, Shah V, et al. Methodology for Knowledge Synthesis of the Management of Vaccination Pain and Needle Fear. Clin J Pain. 2015;31(10 Suppl):S12–9. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lotto G, Alberio M. Tecniche e approcci assistenziali per ridurre l’ansia e la fobia degli aghi nelle persone adulte [Techniques and assistance approaches to reduce anxiety and needle-phobia in adults] L’Infermiere [Nurse] 2014;3:4–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackereth P, Hackman E, Tomlinson L, Manifold J, Orrett L. “Needle with ease”: rapid stress management techniques. Br J Nurs. 2012;21:S18–22. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2012.21.Sup14.S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birnie KA, Noel M, Parker JA, et al. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Distraction and Hypnosis for Needle-Related Pain and Distress in Children and Adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014;39:783–808. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynn K. Needle phobics: stuck on not getting stuck. MLO Med Lab Obs. 2010;42:46–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodspeed RB, Lee BY. What if. . .a patient is highly fearful of needles? J Ambul Care Manage; 2011;34:203–4. doi: 10.1097/01.JAC.0000396249.28483.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke SD, Vercler SJ, Bye R, Desmond PC, Rees YW. Local Anesthesia Before IV Catheterization. Am J Nurs. 2011;111:40–5. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000394291.40330.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eidelman A, Weiss JM, Lau J, Carr DB. Topical Anesthetics for Dermal Instrumentation: A Systematic Review of Randomized, Controlled Trials. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:344–51. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meiri N, Ankri A, Hamad-Saied M, Konopnicki M, Pillar G. The effect of medical clowning on reducing pain, crying, and anxiety in children aged 2-10 years old undergoing venous blood drawing - a randomized controlled study. Eur J Pediatr. 2016;175:373–9. doi: 10.1007/s00431-015-2652-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canbulat N, Ayhan F, Inal S. Effectiveness of external cold and vibration for procedural pain relief during peripheral intravenous cannulation in pediatric patients. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16:33–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrews GJ, Shaw D. “So we started talking about a beach in Barbados”: Visualization practices and needle phobia. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:1804–10. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mutti LB, Provenzano M, Monzani R. La distrazione per ridurre la percezione del dolore procedurale [Distraction to reduce procedural pain perception]. [Bachelor dissertation] 2014 Available from: Database University of Milan, A.A. 2013/14. [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacLaren J, Cohen LL. A Comparison of Distraction Strategies for Venipuncture Distress in Children. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30:387–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karunaratne M. Neuro-linguistic programming and application in treatment of phobias. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2010;16:203–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox AC, Fallowfield LJ. After going through chemotherapy I can’t see another needle. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11:43–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2006.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Umezawa S, Higurashi T, Uchiyama S, et al. Visual distraction alone for the improvement of colonoscopy-related pain and satisfaction. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4707–14. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i15.4707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharar SR, Alamdari A, Hoffer C, Hoffman HG, Jensen MP, Patterson DR. Circumplex Model of Affect: A Measure of Pleasure and Arousal During Virtual Reality Distraction Analgesia. Games Health J. 2016;5:197–202. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2015.0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 2010;8:18. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weise KL, Nahata MC. EMLA for Painful Procedures in Infants. J Pediatr Health Care. 2005;19:42–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith M, Holder P, Leonard K. Efficacy of A Five-minute Application Of EMLA Cream For The Management Of Pain Associated With Intravenous Cannulation. The Internet Journal of Anesthesiology. 2001;6:1–6. Available from: https://print.ispub.com/api/0/ispub-article/8569 . [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zanoli G. Visual analogue scale (VAS): istruzioni per l’uso. [Visual analogue scale (VAS): instructions for use ] 2005 Available from: http://www.globeweb.org/newsletter/guide_1.html . [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kettwich SC, Sibbitt WL Jr, Brandt JR, Johnson CR, Wong CS, Bankhurst AD. Needle phobia and stress-reducing medical devices in pediatric and adult chemotherapy patients. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2007;24:20–8. doi: 10.1177/1043454206296023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polit D, Beck CT. Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 10th edition. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Decreto Legislativo [Legislative Decree] 30 June 2003 no. 196. Code regarding the protection of personal data. [2003, July 29]. Gazzetta Ufficiale [Official Journal] No. 184. [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of persisting pain in children with medical illnesses. 2012 Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44540/1/9789241548120_Guidelines.pdf . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen LL, Blount RL, Cohen RJ, Schaen ER, Zaff JF. Comparative study of distraction versus topical anesthesia for pediatric pain management during immunizations. Health Psychol. 1999;18:591–8. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]