Abstract

Articular cartilage repair is still a challenge. To date evidence is insufficient to support a treatment over the others. Inflammatory conditions in the joint hamper the application of tissue engineering during chronic joint diseases. Most of the Matrix Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (MACI) cases reported in literature do not deal with rheumatoid knees and do not have a long clinical-histologic follow-up. We report about a 46-year old woman who suffered of a painful focal Outerbridge 4th degree chondral lesion in the medial femoral condyle of her left rheumatoid knee. The tissue defect was filled by a Cartilage Regeneration System (CaReS®) based on a type I collagen matrix seeded by autologous in vitro expanded chondrocytes. The patient was followed up to ten years clinically and by MRI, and finally treated with a Total Knee Replacement for the increasing arthritis. Histologically, the explanted MACI tissue showed an increased cellularity with an extracellular matrix rich of collagen and glycosaminoglicanes even though the overall architecture was different from the normal cartilage pattern. The case reported suggests that the main goal of treatment for chondropathy is the long lasting control of symptoms, while permanent restoration of normal anatomy is still impossible. Mesenchymal stem cells, that develop into joint tissues, show immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory qualities, in vitro and in vivo, indicating a potential role for tissue engineering approaches in the treatment of rheumatic diseases. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: MACI, reumatoid, knee, tissue engineering, autologous condrocyte implant, cartilage, regenerative medicine

Introduction

Cartilage defects of the knee are often debilitating and predispose to osteoarthritis (1). Hyaline cartilage regeneration is still a challenge.

In a recent Cochrane Review (1) insufficient evidence was found to compare allograft transplantation, drilling, mosaicplasty, abrasion arthroplasty and microfracture interventions for treating isolated cartilage defects of the knee in adults. Treatment failure, with recurrence of symptoms, occurred with any procedure and osteoarthritis may develop (1, 2).

In the 2010 Cochrane Systematic Review (2) dealing specifically with “Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (ACI) for full thickness articular cartilage defects of the knee”, three trials compared ACI versus mosaicplasty. One reported statistically significant results in favour of ACI at one year in terms of ‘good’ or ‘excellent’ functional results. Conversely, another trial found significant improvement for the mosaicplasty group when assessed using one functional scoring system at two years, but no statistically significant differences based on two other scoring systems. The third trial found no difference between ACI and mosaicplasty, at an average follow up of 10 months after the surgery. In the same review there was no statistically significant difference in functional outcomes at two years in a single trial comparing ACI with microfractures nor in the functional results at 18 months of a single trial comparing characterised chondrocyte implantation versus microfractures. However, the results at 36 months for this trial seemed to indicate better functional results for characterised chondrocyte implantation compared with those for microfractures. The trial comparing Matrix-guided ACI (MACI) versus microfractures found significantly better results for functional outcomes at two year follow-up in the MACI group (2).

Diseases such as degenerative or rheumatoid arthritis are accompanied by joint destruction. Tissue engineering technologies like ACI, MACI, or in situ recruitment of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells are usually applied to treat focal cartilage defects in non-inflammatory joint deseases. Inflammatory conditions in the joint hamper the application of tissue engineering since most likely, cartilage formation is impaired with degradation of the newly formed tissue (3).

Most of the MACI cases reported in literature do not deal with rheumatoid knees and do not have a long follow-up with a clinical and histologic evaluation.

Case Report

We report about a case of a 46-year old woman who suffered of a painful focal Outerbridge 4th degree chondral lesion in the weight bearing zone of her left medial femoral condyle (Fig. 1). She had a moderate valgus and stable knee and therefore an invasive surgical procedure, such as an osteotomy or a prosthetic replacement, was not indicated. The full thickness cartilage defect measured 15 x 23 mm with a surface area of 3,45cm2 (Fig. 1, 2a).

Figure 1.

Pre-MACI MRI showing the chondral defect of the medial femoral condyle: a) coronal, b) sagittal

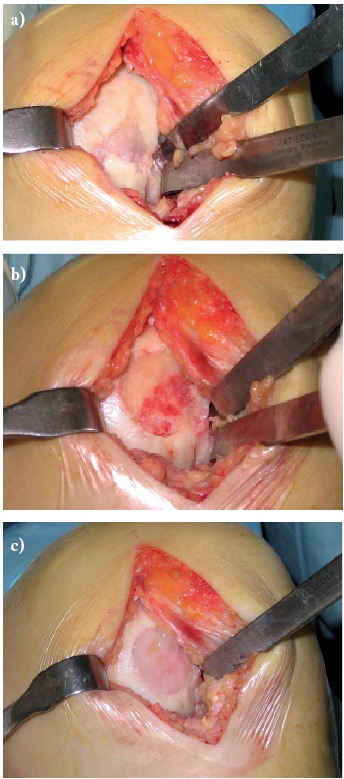

Figure 2.

Intraoperative pictures: a) chondral defect of the medial femoral condyle, b) defect after abrasion, c) MACI grafting

In 2006 the tissue defect was filled by implanting an autologous in vitro expanded chondral graft processed with the CaReS® (Cartilage Regeneration System) a technology relying on a type I collagen scaffold seeded by autologous in vitro expanded chondrocytes (Ars Arthro Biotechnologie GmbH, Magnesistr. 1, A-3500 Krems, Austria) (Fig. 2), harvested 4 weeks before from the same knee.

After surgical treatment, weight bearing was not allowed for six weeks, while ROM was started immediately; partial weight bearing assisted by crutches was maintained until three months after surgery.

A few days after the implant procedure the patient claimed a painful and swollen knee probably due to an acute arthro-synovitis which was resolved by a cycle of systemic steroid.

Ten months post-operatively MRI (Fig. 3) showed the osteochondral defect volume fullfilled by the graft.

Figure 3.

One year after MACI grafting follow up MRI: a) coronal, b) sagittal

Since 2009 seronegative Reumatoid Arthritis was diagnosed and treated by methotrexate; moreover, hypothyroidism was treated by L-tiroxina and hyperparathyroidism treated with D3 vitamin.

5 years follow up MRI (Fig. 4) still showed the newly formed tissue in site, but degenerative joint changes were also evident.

Figure 4.

Five years after MACI grafting follow up MRI: a) coronal, b) sagittal SE, c) sagittal STIR

After that initial acute episode, the patient referred a good level of Quality of Life for 8 years. During the last years she underwent repeated intra-articular injections of high molecular weight hyaluronic acid to control symptoms.

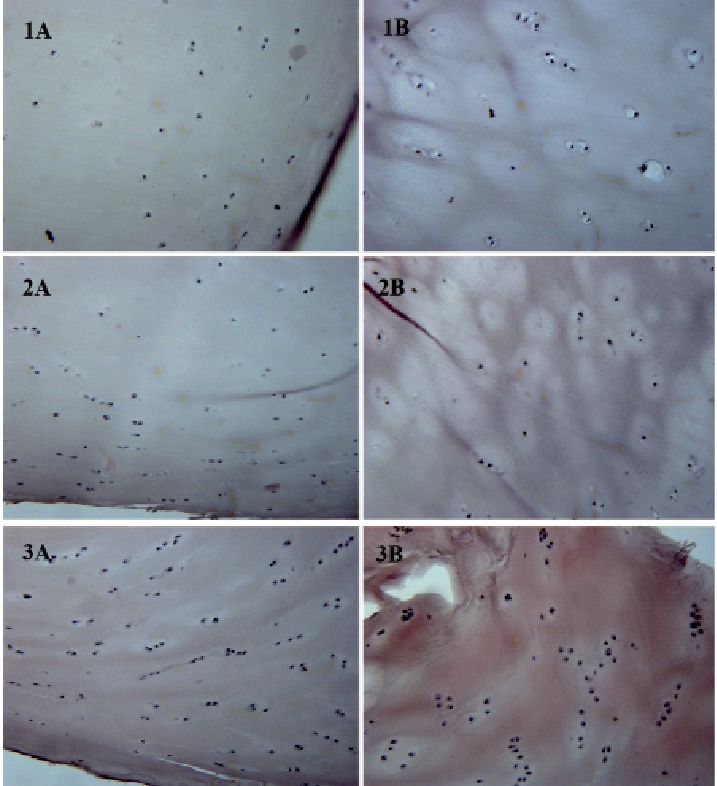

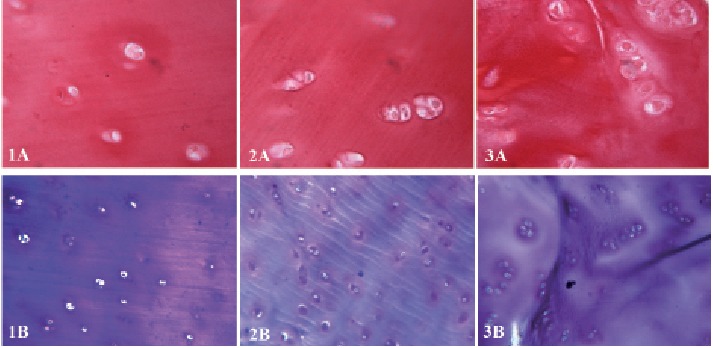

In October 2016 (ten years after chondro-auto-transplantation and at the age of 56 years) the knee was continuously painful, limiting the patient in the Activities of Daily Living. The weight bearing radiographic exam (Fig. 5) showed deformation of the medial femoral condyle with partial preservation of the articular rim. A Total Knee Replacement was eventually performed. The macroscopic anatomo-pathological aspect of the medial femoral condyle (Fig. 6) showed a degenerated surface with a depressed area of 3 cm maximum diameter. The explanted osteochondral tissues of the femoral condyle were processed for histologic examination by Hematossilin/Eosine (HE) (Fig. 7), Sirius colorant for collagen and Blue Toluidine colorant for GlycosAminoGlicanes (GAG) (Fig. 8). In the histologic images at optic microscope (Fig. 7–8), the ACI central zone, in comparison with the peripheral zone, showed an increased cellularity with an extracellular matrix rich of collagen and GAG, but the overall architecture was not reproducing the normal hyalin cartilage.

Figure 5.

Tele-Xray of weight bearing Lower Limbs 10 years post MACI grafting

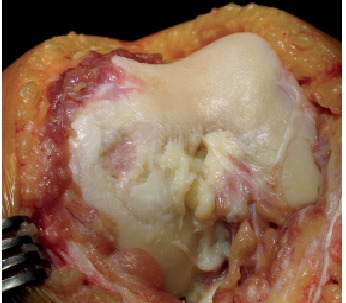

Figure 6.

Intraoperative picture 10 years post MACI grafting, at the moment of Total Knee Replacement

Figure 7.

Hematossilin/Eosine Histology: A) periferic zone, B) central zone. Zone 1) far from MACI, zone 2) intermediate, zone 3) MACI

Figure 8.

Sirius (colorant for collagen) & Blue Toluidine (colorant for GAG) Histology. A) periferic zone; B) central zone. Zone 1) far from MACI, zone 2) intermediate, zone 3) MACI

Discussion

Structural damage to articular cartilage represents a problem for many people worldwide and repairing techniques through cartilage tissue engineering showed promising results in clinical pilot studies. The choice of appropriate cell types is still a critical issue (4, 5). The use of autologous chondrocytes as terminally differentiated cells is limited because of their low proliferation potential, which decreases with age (4, 6), whereas culturing undifferentiated stem cells is more promising because of their higher proliferation capability together with their differentiation potential (4, 7). The ACI technique requires a two step surgical procedure (8), which is not as comfortable as the one step technique of the autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSC) transplantation. Surgical techniques relying on bone marrow stimulation (e.g. drilling, microfracture) are cheaper and simpler, but lead to fibrocartilage formation, which fills the defect but has poor mechanical properties not capable of resisting cyclic loading and shearing forces for a long time at least for larger defects (9, 10).

However, there is still insufficient evidence to draw conclusions on the advantages of ACI for treating full thickness articular cartilage defects in the knee, and further randomised controlled trials with long-term functional outcomes are required (2).

The case reported suggests that the main goal of ACI for chondral defects is the long lasting control of symptoms, in order to preserve joint function and a good Quality of Life.

Permanent restoration of normal anatomy cannot be achieved by simple repair of the defect, but relies on several factors that need to be addressed in future studies.

MSC have the potential to regenerate articular cartilage. Moreover they show in vitro and in vivo immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory qualities indicating a transplant-protecting activity. Therefore, these cells might play an important role for future tissue engineering approaches for the treatment of rheumatic diseases (3).

References

- 1.Gracitelli GC, Moraes VY, Franciozi CES, Luzo MV, Belloti JC. Surgical interventions (microfracture, drilling, mosaicplasty, and allograft transplantation) for treating isolated cartilage defects of the knee in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016;(Issue 9) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010675.pub2. Art. No.: CD010675. DOI: 10.1002/14651858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vasiliadis HS, Wasiak J. Autologous chondrocyte implantation for full thickness articular cartilage defects of the knee. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010;(Issue 10) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003323.pub3. Art.No.: CD003323. DOI: 10.1002/14651858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ringe J, Sittinger M. Tissue engineering in the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(1):211. doi: 10.1186/ar2572. doi: 10.1186/ar2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosetti M, Boccafoschi F, Leigheb M, Bianchi AE, Cannas M. Chondrogenic induction of human mesenchymal stem cells using combined growth factors for cartilage tissue engineering. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. 2012 Mar;6(3):205–213. doi: 10.1002/term.416. doi: 10.1002/term.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunziker EB. Articular cartilage repair: basic science and clinical progress. A review of the current status and prospects. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2002;10:432–463. doi: 10.1053/joca.2002.0801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dozin B, Malpeli M, Camardella L, et al. Response of young, aged and osteoarthritic human articular chondrocytes to inflammatory cytokines: molecular and cellular aspects. Matrix Biol. 2002;21:449–459. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(02)00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL. Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature. 2002;418:41–49. doi: 10.1038/nature00870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ronga M, Grassi FA, Bulgheroni P. Arthroscopic autologous chondrocyte implantation for the treatment of a chondral defect in the tibial plateau of the knee. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(1):79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ronga M, Grassi FA, Manelli A, Bulgheroni P. Tissue engineering techniques for the treatment of a complex knee injury. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(5):576.e1–576.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brittberg M, Peterson L, Sjogren-Jansson E, Tallheden T, Lindahl A. Articular cartilage engineering with autologous chondrocyte transplantation. A review of recent developments. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:109–115. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200300003-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]