Alternative splicing of Drosophila Dscam2 is regulated by cell type–specific expression of the RNA binding protein Muscleblind.

Abstract

Alternative splicing increases the proteome diversity crucial for establishing the complex circuitry between trillions of neurons. To provide individual cells with different repertoires of protein isoforms, however, this process must be regulated. Previously, we found that the mutually exclusive alternative splicing of Drosophila Dscam2 produces two isoforms (A and B) with unique binding properties. This splicing event is cell type specific, and the transmembrane proteins that it generates are crucial for the development of axons, dendrites, and synapses. Here, we show that Muscleblind (Mbl) controls Dscam2 alternative splicing. Mbl represses isoform A and promotes the selection of isoform B. Mbl mutants exhibit phenotypes also observed in flies engineered to express a single Dscam2 isoform. Consistent with this, mbl expression is cell type specific and correlates with the splicing of isoform B. Our study demonstrates how the regulated expression of a splicing factor is sufficient to provide neurons with unique protein isoforms crucial for development.

INTRODUCTION

Alternative splicing occurs in approximately 95% of human genes and generates proteome diversity much needed for brain wiring (1, 2). Specifying neuronal connections through alternative splicing would require regulated expression of isoforms with unique functions in different cell types to carry out distinct processes. Although there are some examples of neuronal cell type–specific isoform expression (3–8), the mechanisms underlying these deterministic splicing events and their functional consequences remain understudied. This is due, in part, to the technical difficulties of assessing and manipulating isoform expression in vivo and at the single-cell level. Another obstacle is that most splicing regulators are proposed to be ubiquitously expressed (9). For example, the broadly expressed SR and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins typically have opposing activities, and the prevalence of splice site usage is thought to be controlled by their relative abundances within the cell (10). Although there are many examples where splicing regulators are expressed in a tissue-specific manner (11–16), until recently, reports of cell type–specific expression have been less frequent (17, 18).

In insects, Dscam2 is a cell recognition molecule that mediates self- and cell type–specific avoidance (tiling) (19–21). Mutually exclusive alternative splicing of exon 10A or 10B produces two isoforms with biochemically unique extracellular domains that are regulated both spatially and temporally (19, 21). Previously, we demonstrated that cell type–specific alternative splicing of Drosophila Dscam2 is crucial for the proper development of axon terminal size, dendrite morphology, and synaptic numbers in the fly visual system (4, 22, 23). Although these studies showed that disrupting cell-specific Dscam2 alternative splicing has functional consequences, what regulates this process remained unclear. Here, we conducted an RNA interference (RNAi) screen and identified muscleblind (mbl) as a regulator of Dscam2 alternative splicing. Loss-of-function (LOF) and overexpression (OE) studies suggest that Mbl acts both as a splicing repressor of Dscam2 exon 10A and as an activator of exon 10B (hereafter Dscam2.10A and Dscam2.10B). Consistent with this finding, mbl expression is cell type specific and correlates with the expression of Dscam2.10B. Hypomorphic mbl mutants exhibit visual system phenotypes that are similar to those observed in flies engineered to express one isoform in all Dscam2-positive cells (single-isoform strains). Similarly, driving mbl in mushroom body (MB) neurons that normally select isoform A induces the expression of isoform B and generates a single-isoform phenotype. Although the mbl gene is itself alternatively spliced, we found that selection of Dscam2.10B does not require a specific Mbl isoform and that human MBNL1 can also regulate Dscam2 alternative splicing. Our study provides compelling genetic evidence that the regulated expression of a highly conserved RNA binding protein, Mbl, is sufficient for the selection of Dscam2.10B and that disrupting this mechanism for cell-specific protein expression leads to developmental defects in neurons.

RESULTS

An RNAi screen identifies mbl as a repressor of Dscam2 exon 10A selection

We reasoned that the neuronal cell type–specific alternative splicing of Dscam2 is likely regulated by RNA binding proteins and that we could identify these regulators by knocking them down in a genetic background containing an isoform reporter. In photoreceptors (R cells) of third-instar larvae, Dscam2.10B is selected, whereas the splicing of Dscam2.10A is repressed (4, 24). Given that quantifying a reduction in Dscam2.10B isoform reporter levels is challenging compared to detecting the appearance of Dscam2.10A in cells where it is not normally expressed, we performed a screen for repressors of isoform A in R cells.

To knock down RNA binding proteins, the glass multimer reporter (GMR)-GAL4 was used to drive RNAi transgenes selectively in R cells. Our genetic background included UAS-Dcr-2 to increase RNAi efficiency and GMR-GFP to mark the photoreceptors independent of the Gal4/UAS system (25). Last, a Dscam2.10A-LexA reporter driving LexAOp-myristolated tdTomato (hereafter Dscam2.10A>tdTom; Fig. 1A) was used to visualize isoform A expression (24). As expected, Dscam2.10B>tdTom was detected in R cell projections in the lamina plexus as well as in their cell bodies in the eye disc, whereas Dscam2.10A>tdTom was not (Fig. 1, C and D). OE of Dcr-2 in R cells did not perturb the repression of Dscam2.10A (Fig. 1O). We knocked down ~160 genes using ~250 RNAi lines (Fig. 1B and table S1) and identified two independent RNAi lines targeting mbl that caused aberrant expression of Dscam2.10A in R cells where it is normally absent (Fig. 1, F and O). The penetrance increased when animals were reared at a more optimal Gal4 temperature of 29°C (Fig. 1O) (26).

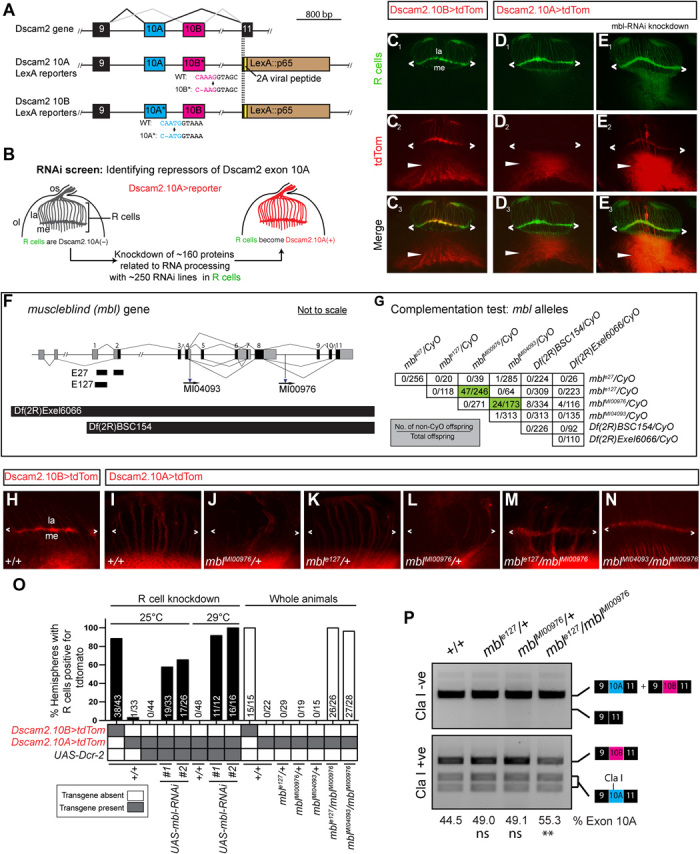

Fig. 1. Drosophila mbl is required for the repression of Dscam2 exon 10A in R cells.

(A) Schematic showing the region of Dscam2 exon 10 that undergoes mutually exclusive alternative splicing and the LexA isoform-specific reporter lines. Frameshift mutations in the exon not reported are shown. WT, wild-type. (B) Schematic RNAi screen design for identifying repressors of Dscam2 exon 10A selection. R cells normally select exon 10B and repress exon 10A. We knocked down RNA binding proteins in R cells while monitoring 10A expression. os, optic stalk; ol, optic lobe; la, lamina; me, medulla. (C to E) Dscam2 exon 10A is derepressed in R cells when mbl is knocked down. (C1 to C3) Dscam2.10B control. R cells (green) normally select exon 10B (red). R cell terminals can be observed in the lamina plexus (angle brackets). Dscam2.10B is also expressed in the developing optic lobe (arrowheads). (D1 to D3) Dscam2.10A is not expressed in R cells (green) but is expressed in the developing optic lobe (arrowheads). (E1 to E3) RNAi lines targeting mbl in R cells result in the aberrant expression of Dscam2.10A in R cells. (F) Schematic of the mbl gene showing the location of two small deletions (E27 and E127), two MiMIC insertions (MI04093 and MI00976), and two deficiencies [Df(2R)Exel6066 and Df(2R)BSC154] used in this study. Noncoding exons are in gray, and coding exons are black. (G) Complementation test of mbl LOF alleles. Numbers in the table represent the number of non-CyO offspring over the total. Most transheterozygote combinations were lethal with the exception of mblMI00976/mble27 and mblMI00976/mblMI04093 (green). (H to N) Mbl transheterozygotes express Dscam2.10A in R cells. (H) Dscam2.10B control showing expression in the lamina plexus (angle brackets). (I) Dscam2.10A control showing no expression of this isoform in R cells. (J to L) Heterozygous animals for mbl LOF alleles are comparable to control. (M and N) Two different mbl transheterozygote combinations exhibit derepression of Dscam2.10A in R cells. (O) Quantification of Dscam2.10>tdTom expression in third-instar R cells with various mbl manipulations, including RNAi knockdown (black bars) and whole-animal transheterozygotes (white bars). Y axis represents the number of optic lobes, with R cells positive for tdTom over total quantified as a percentage. On the x axis, the presence of a transgene is indicated with a gray box, and the temperature at which the crosses were reared (25° or 29°C) is indicated on the top. (P) Dscam2 exon 10A inclusion is increased in mbl transheterozygotes. Top: Semiquantitative RT-PCR from different genotypes indicated. Primers amplified the variable region that includes exon 10. A smaller product that would result from exon 10 skipping is not observed. Bottom: Exon 10A–specific cleavage with restriction enzyme Cla I shows an increase in exon 10A inclusion in mbl transheterozygotes. The percentage of exon 10A inclusion was calculated by dividing 10A by 10A+10B bands following restriction digest. The mean of exon 10A inclusion is shown at the bottom of each lane. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) test with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to compare the exon 10A inclusion. ns, P > 0.05; **P < 0.01. See also figs. S1 and S2.

Mbl family proteins have evolutionarily conserved tandem CCCH zinc-finger domains through which they bind pre-mRNA. Vertebrate Mbl family members are involved in tissue-specific splicing and have been implicated in myotonic dystrophy (27). Formerly known as mindmelt, Drosophila mbl was first identified in a second chromosome P-element genetic screen for embryonic defects in the peripheral nervous system (28). Mbl produces multiple isoforms through alternative splicing (29, 30), and its function has been most extensively characterized in fly muscles, where both hypomorphic mutations and sequestration of the protein by repeated CUG sequences within an mRNA lead to muscle defects (31). To validate the RNAi phenotype, we tested Dscam2.10A>tdTom expression in mbl LOF mutants. Because mbl LOF results in lethality, we first conducted complementation tests on six mbl mutant alleles to identify viable hypomorphic combinations. These included two alleles created previously via imprecise P-element excision (mble127 and mble27), two MiMIC (Minos Mediated Integration Cassette) splicing traps (mblMI00976 and mblMI04093), and two second chromosome deficiencies [Df(2R)BSC154 and Df(2R)Exel6066] (Fig. 1, F and G). Consistent with previous reports, the complementation tests confirmed that the majority of the alleles were lethal over one another (Fig. 1G) (28). However, we identified two mbl transheterozygous combinations that were partially viable and crossed these into a Dscam2.10A>tdTom reporter background. Both mble127/mblMI00976 and mblMI04093/mblMI00976 animals presented aberrant Dscam2.10A expression in R cells when compared to heterozygous and wild-type controls (Fig. 1, H to O). Mbl mutant mosaic clones also exhibited aberrant Dscam2.10A>tdTom expression in R cells (fig. S1, A to F). The weakest allele, mblM00976, which removes only a proportion of the mbl isoforms, was the only exception (fig. S1, E and F).

One alternative explanation of how Dscam2.10A>tdTom expression could get switched on in mbl mutants is through exon 10 skipping. Removing both alternative exons simultaneously does not result in a frameshift mutation, and because the Gal4 in our reporters is inserted directly downstream of the variable exons (in exon 11), it would still be expressed. To test this possibility, we amplified Dscam2 sequences between exons 9 and 11 in mble127/mblMI00976 transheterozygous animals using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). In both control and mbl LOF mutants, we detected RT-PCR products [~690 base pairs (bp)] that corresponded to the inclusion of exon 10 (A or B) and failed to detect products (~390 bp) that would result from exon 10 skipping (Fig. 1P). This suggested that Mbl is not involved in the splicing fidelity of Dscam2.10 but rather in the selective mutual exclusion of its two isoforms. To assess whether the ratios of the two isoforms were changing in the mbl hypomorphic mutants, we cut the exon 10 RT-PCR products with the Cla I restriction enzyme that only recognizes exon 10A. Densitometric analysis then allowed us to semiquantitatively compare the relative levels of both isoforms. There was a ~25% increase in the level of exon 10A inclusion in mble127/mblMI00976 animals compared to controls (Fig. 1P). Similarly, quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) of the mble127/mblMI00976 animals showed a ~1.25- and ~0.78-fold change in exon 10A and 10B inclusion, respectively, when compared to controls. Both results are consistent with the derepression that we observed in our 10A reporter lines. To determine whether Mbl was specifically regulating Dscam2 exon 10 mutually exclusive splicing, we assessed other Dscam2 alternative splicing events. These included an alternative 5′ splice site selection of Dscam2 exon 19 and the alternative last exon selection of exon 20 (fig. S2A). The expression of these different isoforms was unchanged in mbl hypomorphic mutants (fig. S2B). Together, our results indicate that Mbl is an essential splicing factor that specifically represses Dscam2.10A.

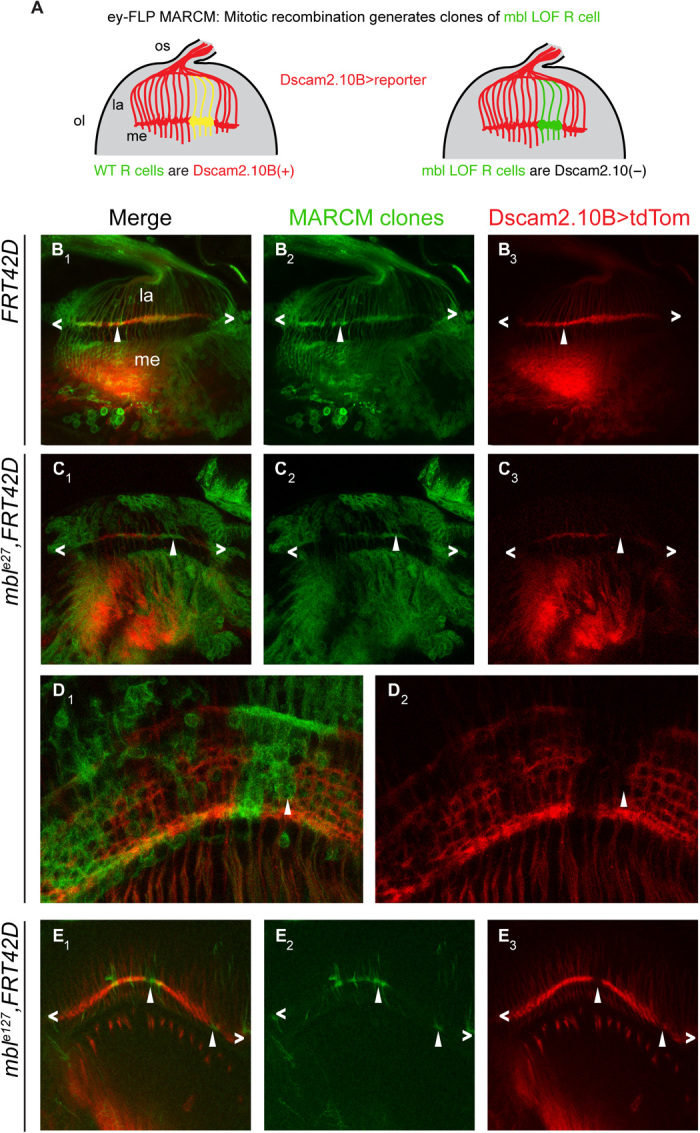

Mbl is necessary for the selection of Dscam2 exon 10B

Because Dscam2 exon 10 isoforms are mutually exclusively spliced, we predicted that selection of exon 10A would lead to the loss of exon 10B selection. To test this, we conducted mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) (32) to analyze Dscam2.10B expression in mbl mutant clones. In late third-instar brains, clones homozygous [green fluorescent protein (GFP) positive] for mble127 and mble27 exhibited a marked reduction in Dscam2.10B>tdTom expression in R cell axons projecting to the lamina plexus compared to controls (Fig. 2, B, C, and E). The absence of Dscam2.10B>tdTom in mbl mutant clones was more notable during pupal stages (Fig. 2D), suggesting that perdurance of Mbl could explain the residual signal observed in third-instar animals. These results reveal that mbl is cell-autonomously required for the selection of Dscam2.10B.

Fig. 2. Drosophila mbl is necessary for the selection of Dscam2 exon 10B in R cells.

(A) Schematic of our predicted mbl MARCM results using ey-FLP. Wild-type R cell clones will be GFP(+) and Dscam2.10B>tdTom(+) (yellow), whereas mbl mutant clones will be Dscam2.10B>tdTom(−) (green). (B1 to B3) Control MARCM clones (green) in third-instar R cells (angle brackets) are positive for Dscam2.10B>tdTom (arrowheads). (C1 to C3) In mble27 clones, Dscam2.10B labeling in the lamina plexus is discontinuous, and its absence correlates with the loss of mbl (arrowheads). (D1 and D2) Mbl MARCM clones from midpupal optic lobes lack Dscam2.10B>tdTom. (E1 to E3) A different allele (mble127) exhibits a similar phenotype in third-instar brains.

Mbl expression is cell type specific and correlates with Dscam2.10B selection

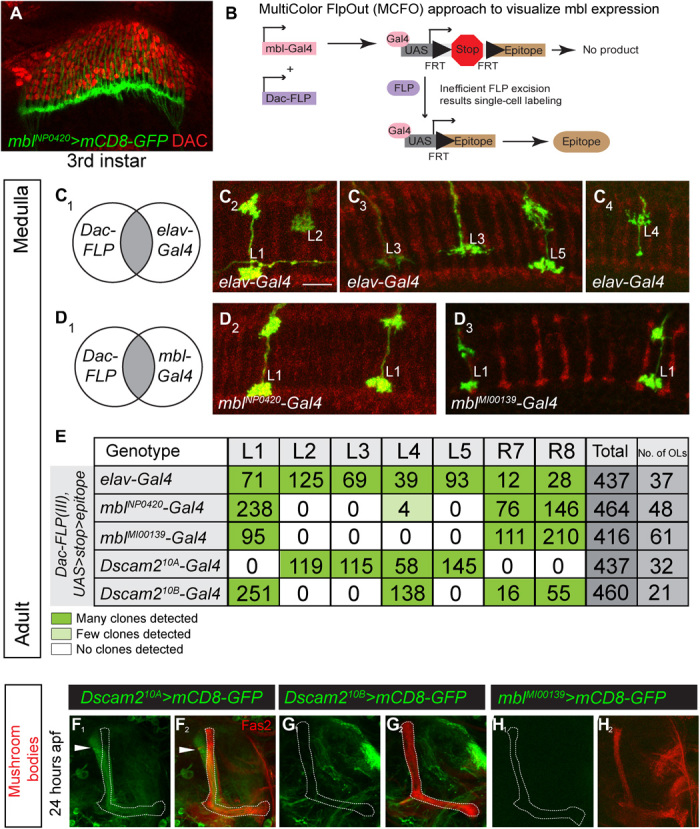

Previous studies have reported that mbl is expressed in third-instar eye discs and muscles (31, 33). Because mbl LOF results in both the selection of Dscam2.10A and the loss of Dscam2.10B, we predicted that mbl expression would correlate with the presence of isoform B. To test this, we characterized several mbl reporters (fig. S3A). We analyzed three enhancer trap strains (transcriptional reporters) inserted near the beginning of the mbl gene (mblk01212-LacZ, mblNP1161-Gal4, and mblNP0420-Gal4), as well as a splicing trap line generated by the Trojan-mediated conversion of an mbl MiMIC insertion (fig. S2A, mblMiMIC00139-Gal4) (34). The splicing trap reporter consists of a splice acceptor site and an in-frame T2A-Gal4 sequence inserted in an intron between two coding exons. This Gal4 cassette gets incorporated into mbl mRNA during splicing, and therefore, Gal4 is only present when mbl is translated. Consistent with previous studies, and its role in repressing the production of Dscam2.10A, all four mbl reporters were expressed in the third-instar photoreceptors (Fig. 3A and fig. S3, A to D). We next did a more extensive characterization of mbl expression by driving nuclear localized GFP (GFP.nls) with one transcriptional (mblNP0420-Gal4) and one translational (mblMiMIC00139-Gal4) reporter. In the brain, we found that mbl was expressed predominantly in postmitotic neurons, with some expression detected in glial cells (fig. S3, C to H and J to M). We detected the translational, but not the transcriptional, reporter in third-instar muscles (fig. S3, I and N). The absence of expression is likely due to the insertion of the P-element into a neural-specific enhancer, as previously described (35). To assess the expression of mbl in the five lamina neurons, L1 to L5, all of which express Dscam2 (4, 24), we implemented an intersectional strategy using a UAS>stop>epitope reporter (36) that is dependent on both FLP and Gal4. The FLP source (Dac-FLP) was expressed in lamina neurons and was able to remove the transcriptional stop motif in the reporter transgene. The overlap between mbl-Gal4 and Dac-FLP allowed us to visualize mbl expression in lamina neurons at single-cell resolution (Fig. 3B). As a proof of principle, we first did an intersectional analysis with a pan-neuronal reporter, elav-Gal4 (Fig. 3C1). We detected many clones encompassing various neuronal cell types including the axons of L1 to L5 and R7 and R8 (Fig. 3, C and D). This confirmed that all lamina neurons could be detected using this strategy. Using mbl-Gal4 reporters, we found that L1, R7, and R8, which expresses Dscam2.10B, were the primary neurons labeled. A few L4 cells were also detected, which is consistent with this neuron expressing Dscam2.10B early in development and Dscam2.10A at later stages (24). To confirm this finding, we dissected the expression of mbl in lamina neurons during development. Using the same intersectional strategy, we detected a high number of L4 clones at 48 hours after puparium formation (apf) (30%, n = 10). This was followed by a decline at 60 hours apf (26.7%, n = 30) and 72 hours apf (11.8%, n = 85), reaching the lowest at eclosion (fig. S4, A and B; 1.7%, n = 242). Thus, mbl expression in L4 neurons mirrors the expression of Dscam2.10B. Consistent with this, L2, L3, and L5 were all detected using the intersectional strategy with Dscam2.10A-Gal4 but were not labeled using mbl-Gal4 (Fig. 3E). Our intersectional mbl expression data are further strengthened by an independent RNA-sequencing study of isolated lamina neurons during development, where mbl is detected at high levels in L1, R7, and R8 neurons (~5- to 100-fold more than L2 to L5) (37). Together, these results show that mbl expression correlates with the cell type–specific alternative splicing of Dscam2.10B. This suggests that the presence or absence of mbl can determine the selection of the Dscam2.10 isoform in a cell.

Fig. 3. Mbl is expressed in a cell-specific manner that correlates with Dscam2.10B.

(A) An mbl-Gal4 reporter (green) is expressed in third-instar R cells but not in lamina neuron precursor cells labeled with an antibody against Dacshund (DAC; red). (B) Schematic of MultiColor FlpOut (MCFO) approach to characterize mbl reporter expression in lamina neurons at adult stages. The UAS FlpOut construct produces an epitope-tagged version of a nonfluorescent GFP [smGFP (36)]. (C1 to C4) All lamina neurons can be detected using an MCFO strategy with a pan-neuronal reporter (elav-Gal4). Lamina neurons were identified on the basis of their unique axon morphologies. (D1 to D4) An intersectional strategy using mbl-Gal4 primarily labels L1 lamina neurons. (E) Quantification of lamina neurons and R7 and R8 neurons observed using the intersectional strategy. Dark green and light green boxes represent high and low numbers of labeled neurons, respectively. (F to H) Mbl is not expressed in MB neurons that express Dscam2.10A at 24 hours apf. (F1 and F2) Dscam2.10A is expressed in α′β′ MB neurons that are not labeled by Fas2. Fas2 labels the αβ and γ subsets of MB neurons. (G and H) Neither Dscam2.10B (G1 and G2) nor mbl (H1 and H2) is detected in MB neurons. See also figs. S3 and S4.

Ectopic expression of multiple mbl isoforms is sufficient to promote the selection of Dscam2 exon 10B

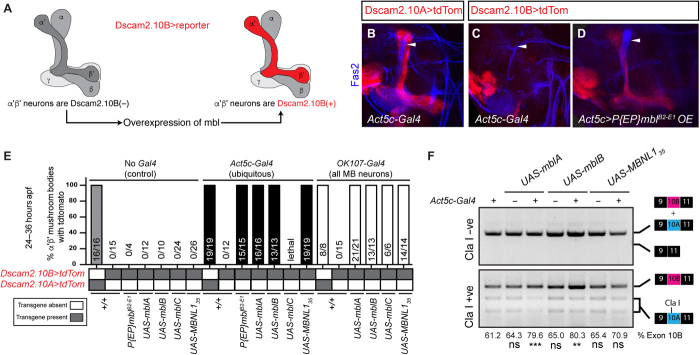

Because cells that select Dscam2.10B express mbl and cells that select Dscam2.10A lack mbl, we wondered whether it was sufficient to promote exon 10B selection in Dscam2.10A-positive cells. To test this, we ectopically expressed mbl with a ubiquitous driver (Act5c-Gal4) and monitored isoform B expression using Dscam2.10B>tdTom. We focused on the MB, as this tissue expresses isoform A specifically in α′β′ neurons at 24 hours apf where mbl is not detected (Figs. 3, G and H, 4, A to C). Consistent with our prediction, ectopic expression of mbl using an enhancer trap containing a UAS insertion at the 5′ end of the gene (Act5c>mblB2-E1) switched on Dscam2.10B in α′β′ MB neurons, where it is normally absent (Fig. 4D). Driving mbl with an MB-specific Gal4 (OK107) gave similar results (Fig. 4E). Although our two Gal4 drivers expressed mbl in all MB neurons, Dscam2.10B was only observed in α′β′ neurons, demonstrating that transcription of Dscam2 is a prerequisite for this splicing modulation. Previous studies have suggested that the mbl gene is capable of generating different isoforms with unique functions depending on their subcellular localization (38). This also includes the production of a highly abundant circular RNA (circRNA) that can sequester the Mbl protein (39, 40). To assess whether Dscam2 exon 10B selection is dependent on a specific alternative variant of Mbl, we overexpressed the complementary DNAs (cDNAs) of fly mbl isoforms [mblA, mblB, and mblC; (29)], as well as an isoform of the human MBNL1 that lacks the linker region optimal for CUG repeat binding [MBNL135; (41)] with either Act5c-Gal4 or OK107-Gal4. These constructs all have the tandem N-terminal CCCH motif that binds to the consensus YCGY motif (29) and lack the ability to produce mbl circRNA (40). In all cases, OE resulted in the misexpression of Dscam2.10B in α′β′ MBs (with the exception of Act5C>mblC, which resulted in lethality; Fig. 4, D and E). Using semiquantitative RT-PCR from the Act5C>mbl flies, we demonstrated that OE of mbl did not lead to exon 10 skipping and that it increased exon 10B selection by 8 to 24% (Fig. 4F), depending on the mbl isoform used. The inability of Mbl to completely inhibit exon 10A selection suggests that other factors or mechanisms may also contribute to cell-specific Dscam2 isoform expression (see Discussion). These results suggest that Mbl protein isoforms are all capable of Dscam2.10B selection and independent of mbl circRNA. The ability of human MBNL1 to promote the selection of exon 10B suggests that the regulatory logic for Dscam2 splicing is likely conserved in other mutually exclusive cassettes in higher organisms. Together, our results show that all mbl isoforms are sufficient to promote Dscam2.10B selection.

Fig. 4. Multiple mbl isoforms promote selection of Dscam2 exon 10B.

(A) Schematic showing that mbl is sufficient to drive Dscam2.10B selection in α′β′ neurons. (B) Control showing that Dscam2.10A (red) is expressed in α′β′ neurons at 24 hours apf. (C) Dscam2.10B is normally repressed in α′β′ neurons. (D) OE of mbl activates Dscam2.10B selection (red) in α′β′ neurons. (E) Quantification of Dscam2.10 expression in α′β′ neurons at 24 to 36 hours apf with and without mbl OE. Control (No Gal4, gray bar), ubiquitous driver (Act5c-Gal4, black bars), and pan-MB neuron driver (OK107-Gal4, white bars). Y axis represents the number of tdTom-positive (+) α′β′ over the total, expressed as a percentage. Ratio of tdTom(+)/total is shown in each bar. (F) Mbl OE increases Dscam2 exon 10B inclusion. Semiquantitative RT-PCR as in Fig. 1. Exon 10A–specific cleavage with restriction enzyme Cla I shows an increase in exon 10B inclusion in mbl OE animals, without exon 10 skipping. The percentage of exon 10B inclusion was calculated by dividing 10B by 10A+10B bands following electrophoresis and densitometry. The mean of exon 10B inclusion is shown at the bottom of each lane. ANOVA test with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to compare the exon 10B inclusion. ns, P > 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Mbl regulates cell type–specific Dscam2 alternative splicing in lamina neurons

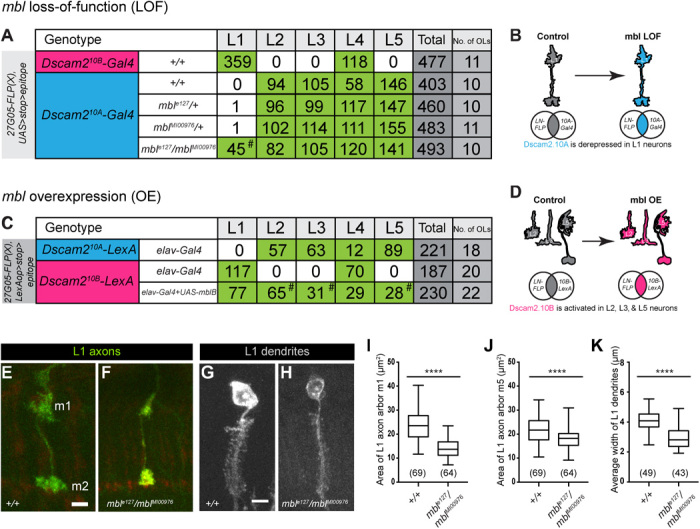

To determine whether the regulatory logic of Dscam2 alternative splicing is consistent in other cell types, we manipulated mbl expression in lamina neurons (L1 to L5). We first asked whether mbl LOF resulted in the derepression of Dscam2.10A in L1 neurons. To do this, we visualized Dscam2 isoform expression in L1 to L5 using an intersectional strategy similar to Fig. 3 but with a different FLP source (27G05-FLP). We detected L1 and L4 neurons when using the Dscam2.10B-Gal4 reporter in a wild-type background, but not L2, L3, or L5. L1 was also not detected when using the Dscam2.10A-Gal4 reporter, where L2 to L5 cells were the primary neurons labeled (Fig. 5A). Consistent with our R cell results, derepression of Dscam2.10A was observed in L1 neurons in mbl transheterozygous animals (mble127/mblMI00976) when compared to the corresponding heterozygous controls (mble127/+ and mblMI00976/+; Fig. 5, A and B). We next asked whether ectopic OE of mbl would result in aberrant Dscam2.10B selection in L2, L3, and L5 neurons where it is usually repressed. For this experiment, the Gal4/UAS system was used to overexpress mbl, and the LexA/LexAop system was used to visualize Dscam2 isoform expression. Using the same intersectional strategy, we found that Dscam2-LexA reporters showed similar patterns to the Dscam2-Gal4 reporters (Fig. 5C). Pan-neuronal OE (elav-Gal4) of mbl caused the aberrant detection of Dscam2.10B in L2, L3,0 and L5 cells that normally select Dscam2.10A (Fig. 5, C and D). Together, our results show that Mbl regulates Dscam2 cell type–specific alternative splicing. The simple presence or absence of mbl is sufficient to determine whether a cell expresses Dscam2.10A or Dscam2.10B.

Fig. 5. Mbl regulates Dscam2 cell type–specific alternative splicing in lamina neurons.

(A) Quantification of lamina neurons L1 to L5 observed using the Dscam2.10B-Gal4 (magenta) or Dscam2.10A-Gal4 (blue) reporters with the intersectional strategy in mbl LOF animals. Green boxes represent a high number of labeled neurons. Dscam2.10A is derepressed in L1 neurons in an mbl LOF background (mblMI00976/mble27, hashtag). (B) Schematic of Dscam2.10A derepression in mbl LOF L1 neurons. (C) Quantification of lamina neurons L1 to L5 observed using the Dscam2.10A-LexA (blue) or Dscam2.10B-LexA (magenta) reporters with the intersectional strategy in animals with pan-neuronal (elav-Gal4) expression of mbl. Green boxes represent high numbers of labeled neurons. Dscam2.10B-LexA was aberrantly detected in L2, L3, and L5 neurons overexpressing mblB (hashtag). (D) Schematic of aberrant Dscam2.10B selection in L2, L3, and L5 neurons overexpressing mbl. (E to K) L1 neurons in mbl LOF animals have reduced axon arbor area and dendritic array width when compared to controls. (E) Representative confocal image of a control L1 axon (green) with arbors at m1 and m5 layers. (F) Representative confocal image of an L1 axon from mbl LOF animals (mblMI00976/mble27). (G) Representative confocal image of a control L1 dendritic array (gray). (H) Representative confocal image of an L1 dendritic array from mbl LOF animals (mblMI00976/mble27). (I) Quantification of an L1 axon m1 arbor area (μm2). (J) Quantification of an L1 axon m5 arbor area (μm2). (K) Quantification of L1 dendritic width (μm). Tukey boxplot format: middle line, median; range bars, min and max; box, 25 to 75% quartiles; and each data point, single cartridge. Numbers in parentheses represent total numbers of L1 neurons quantified. Parametric t test was used to compare mbl LOF L1 axon arbor area with controls. Nonparametric t test was used to compare mbl LOF L1 dendritic width with controls. ****P < 0.0001. Scale bars, 5 μm (E to H).

Manipulation of mbl expression generates phenotypes observed in Dscam2 single-isoform mutants

If Mbl regulates Dscam2 alternative splicing, mbl LOF and OE animals should exhibit similar phenotypes to Dscam2 isoform misexpression. Previously, we showed that flies expressing a single isoform of Dscam2 exhibit a reduction in L1 axon arbor size as well as reduced dendritic width (4, 23). These flies were generated using recombinase-mediated cassette exchange and express a single isoform in all Dscam2-positive cells (4). The reduction in axonal arbors and dendritic widths was proposed to be due to inappropriate interactions between cells that normally express different isoforms. Consistent with these previous studies, we observed a reduction in the area of L1 axon arbors (more prominent in m1 than in m5; Fig. 5, E, F, I, and J) and the width of dendritic arrays (Fig. 5, G, H, and K) in mbl transheterozygous animals (mble127/mblMI00976) when compared to controls. Finally, we observed a phenotype in MB neurons overexpressing mbl, where the β lobe neurons inappropriately crossed the midline (fig. S5, A to C). A similar phenotype was observed in Dscam2A single-isoform mutants. These data demonstrate that MB phenotypes generated in animals overexpressing mbl phenocopy Dscam2 single-isoform mutants. While the origin of this nonautonomous phenotype is not known, it correlates with the misregulation of Dscam2 alternative isoform expression.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identify Mbl as a regulator of Dscam2 alternative splicing. We demonstrate that removing mbl in an mbl-positive cell type results in a switch from Dscam2.10B to Dscam2.10A selection. Ectopic expression of a variety of Mbl protein isoforms in a normally mbl-negative neuronal cell type is sufficient to trigger the selection of Dscam2.10B. Consistent with this, transcriptional reporters demonstrate that mbl is expressed in a cell type–specific manner in multiple cell types, which tightly correlates with Dscam2.10B. Last, both mbl LOF and misexpression lead to phenotypes that are observed in flies that express a single Dscam2 isoform.

Our data demonstrate that mbl is expressed in a cell-specific fashion. In the lamina of the fly visual system, L1 and L2 neurons are developmentally very similar in terms of both morphology and gene expression (37). The difference in mbl expression between these two cells is critical for their development because, when expression of this splicing factor is perturbed, both cells express the same isoform, and inappropriate Dscam2 interactions lead to phenotypes in their axons and dendrites. Although cell-specific mbl expression has been alluded to previously (42–44), our study demonstrates that mbl regulation of Dscam2 alternative splicing has functional consequences. Mbl appears to be regulated at the transcriptional level because the enhancer-trap as well as splicing-trap reporters lack the components crucial for posttranscriptional regulation yet still exhibit cell type–specific expression (Fig. 3). This was unexpected as a recent study showed that mbl encodes numerous alternative isoforms that could be individually posttranscriptionally repressed by different microRNAs, thus bypassing the need for transcriptional control of the gene (45). It will be interesting to explore the in vivo expression patterns of other splicing factors in Drosophila to determine whether cell-specific expression of a subset of splicing factors is a common mechanism for regulating alternative splicing in the brain.

The expression pattern of mbl and its ability to simultaneously repress exon 10A and select exon 10B suggest that this RNA binding protein and its associated cofactors are sufficient to regulate cell type–specific splicing of Dscam2. Dscam2.10A could be the default exon selected when the Mbl complex is absent. In this way, cells that express mbl select Dscam2.10B. Consistent with this, ectopic expression of mbl in mbl-negative cells (L2, L3, L5, and α′β′ neurons) results in the aberrant selection of exon 10B. Our RT-PCR data, however, argue that Dscam2 mutually exclusive alternative splicing may be more complicated than this model. Ubiquitous expression of mbl increased exon B inclusion modestly (up to 24%) as measured by RT-PCR (see Fig. 4F). One might expect a more pronounced shift to isoform B if Mbl were the only regulator/mechanism involved. Further studies, including screens for repressors of exon 10B, will be required to resolve this issue.

The L1 axon and dendrite phenotypes generated through the LOF and ectopic expression of mbl, respectively, demonstrate that this splicing factor regulates aspects of neurodevelopment through cell-specific expression of Dscam2 isoforms. In the lamina, mbl expression in L1, and its absence in L2, permits these neurons to express distinct Dscam2 proteins that cannot recognize each other. Phenotypes arise in these neurons both when they are engineered to express the same isoform (4, 23) and when mbl is misregulated (Fig. 5). These data strongly link the regulation of cell-specific Dscam2 splicing with normal neuron development.

Mbl OE also generates a midline crossing phenotype in MB neurons that is similar to that observed in animals expressing a single isoform. This phenotype is complicated, however, by the observation that Dscam2.10A, but not Dscam2.10B, animals show a statistically significant increase in midline crossing compared to controls (fig. S4). This issue may have to do with innate differences between isoform A and isoform B that are not completely understood. It is possible that isoforms A and B are not identical in terms of signaling because of either differences in homophilic binding or differences in cofactors associated with specific isoforms. Consistent with this notion, we previously reported that Dscam2.10A single-isoform lines produce stronger phenotypes at photoreceptor synapses compared to Dscam2.10B (23).

How does Mbl repress Dscam2.10A and select Dscam2.10B at the level of pre-mRNA? The best-characterized alternative splicing events regulated by human MBNL1 are exon skipping or inclusion events. In general, an exon that contains MBNL1 binding sites upstream or within the coding sequence is subject to skipping, whereas downstream binding sites more often promote inclusion. The mechanisms used by fly Mbl to regulate splicing have not been characterized in detail, but given that human MBNL1 can rescue fly mbl lethality (46) and promote the endogenous expression of Dscam2 exon 10B in MBs, presumably the mechanisms are conserved. A simple explanation for how Mbl regulates Dscam2 mutually exclusive splicing would be that it binds upstream of exon 10A to repress exon inclusion and downstream of exon 10B to promote inclusion. Although there are many potential binding sites for Mbl upstream, downstream, and within the alternative exons, an obvious correlation between location and repression versus inclusion is not observed. In total, there are 63 potential Mbl binding sites (YCGY) within the 5-kb variable region of Dscam2. Identification of the sequences required for regulation by Mbl will therefore require extensive mapping and, ultimately, validation using a technique like CLIP (cross-linking followed by immunoprecipitation) (47) or TRIBE (targets of RNA binding proteins identified by editing) (48).

Together, our results demonstrate that the simple presence or absence of a splicing factor can affect neurodevelopment through the cell-specific selection of distinct isoforms of a cell surface protein. We provide compelling genetic evidence of how Mbl regulates the alternative splicing of Dscam2, and this regulatory logic is likely to extend to cover the splicing events of many other genes crucial for neurodevelopment. Developmental analysis of mbl expression in the cells studied here suggests that it turns on after neurons have obtained their identity (similar to Dscam2) and is therefore well suited for regulating processes such as axon guidance and synapse specification. Identifying these splicing events may provide clues as to how the brain can diversify and regulate its repertoire of proteins to promote neural connectivity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly strains

The following fly strains were used: Dscam2.10A-LexA and Dscam2.10B-LexA (24), UAS-Dcr2 and UAS-mbl-RNAiVDRC28732, LexAop-myr-tdTomato (attP2), UAS-Srp54-RNAiTRiP.HMS03941, CadN-RNAiTRiP.HMS02380 and UAS-mbl-RNAiTRiP.JF03264, UAS-mCD8-GFP (32), FRT42D, mble127 and mble27 (29), mblMI00976 and mblMI04093, Df(2R)BSC154, Df(2R)Exel6066, ey-FLP (Chr.1), GMR-myr-GFP, mblNP0420-Gal4 and mblNP1161-Gal4, mblk01212-LacZ, mblMiMIC00139-Gal4 (H. Bellen Lab), Dac-FLP (Chr.3) (21), UAS>stop>myr::smGdP-V5-THS-UAS>stop>myr::smGdP-cMyc (attP5) (36), Dscam2.10A-Gal4 and Dscam2.10B-Gal4 (4), Act5C-Gal4 (Chr.3, from Y. Hiromi), OK107-Gal4, UAS-mblA, UAS-mblB and UAS-mblC (D. Yamamoto Lab), P{EP}mblB2-E1, UAS-mblA-FLAG, and UAS-MBNL135 (41).

RNAi screening

The RNAi screen line was generated as follows: GMR-Gal4 was recombined with GMR-GFP on the second chromosome. Dscam2.10A-LexA was recombined with LexAop-myr-tdTomato on the third chromosome. These flies were crossed together with UAS-Dcr-2 (X) to make a stable RNAi screen stock. UAS-RNAi lines were obtained from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center and Vienna Drosophila Resource Center. Lethal UAS-RNAi stocks were placed over balancers with developmentally selectable markers. Virgin females were collected from the RNAi screen stock, crossed to UAS-RNAi males, and reared at 25°C. Wandering third-instar larvae were dissected and fixed. We tested between one and three independent RNAi lines per gene. In total, we imaged ~2300 third-instar optic lobes without antibodies using confocal microscopy at 63×. RNAi lines tested are listed in table S1.

Semiquantitative and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Ambion) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Reverse transcription was performed on each RNA sample with random primer mix [semiquantitative; New England Biolabs (NEB)] or Oligo-dT (qRT-PCR; NEB) using 200 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (NEB) and 1 μg of RNA in a 20-μl reaction at 42°C for 1 hour. PCRs were set up with specific primers to analyze alternative splicing of various regions of Dscam2. Where possible, semiquantitative PCR was performed to generate multiple isoforms in a single reaction, and relative levels were compared by electrophoresis followed by densitometry. For qRT-PCR, 1 μl of cDNA was added to a Luna Universal SYBR-Green qPCR Master Mix kit (NEB). Samples were added into a 200-μl 96-well plate and read on a QuantStudio TM 6 Flex Real-Time PCR machine. Rq values were calculated in Excel (Microsoft).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunostaining was conducted as previously described (4). Antibody dilutions used were as follows: mouse mAb24B10 [1:20; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB)], mouse anti-Repo (1:20; DSHB), mouse anti-Dacshund (1:20; DSHB), mouse anti-Fas2 (1:20; DSHB) rat anti–embryonic lethal abnormal vision (ELAV) (1:200), V5-tag:DyLight anti-mouse 550 (1:500; AbD Serotec), V5-tag:DyLight anti-mouse 405 (1:200; AbD Serotec), myc-tag:DyLight anti-mouse 549 (1:200; AbD Serotec), phalloidin/Alexa Fluor 568 (1:200; Molecular Probes), DyLight anti-mouse 647 (1:2000; Jackson Laboratory), and DyLight Cy3 anti-rat (1:2000; Jackson Laboratory).

Image acquisition

Imaging was performed at the School of Biomedical Sciences Imaging Facility. Images were taken on a Leica SP8 laser scanning confocal system with a 63× glycerol NA (numerical aperture) 1.3.

Fly genotypes

Specific genotypes can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank W. Tadros, Y. Chen, L. Zipursky, G. Neely, L. O’Keefe, N. Bonini, A. Nern, and Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center for sharing fly stocks. We thank the Daisuke Yamamoto Lab for constructing the UAS-mbl lines deposited and maintained at the Kyoto Stock Center. We thank S. Walters for technical assistance on the Leica confocal microscopy. We note that G. Shin initially observed Dscam2 isoform expression in the adult MBs. We thank K. Mutemi for thorough characterization of Dscam2 isoform expression in MBs during development and all midline crossing defects in Dscam2 single-isoform mutant animals. We thank W. J. Tan for the heroic feat of triple balancing OK107-Gal4. We also thank members of the Millard, Pecot, Hilliard, and van Swinderen laboratories for their feedback. The RNAi screen was inspired by the works of H. Kuroyanagi. Funding: This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC grant APP1021006). J.S.S.L. was supported by the Australia Postgraduate Award (Research Training Scheme) from the Australian Federal Government and the Lavidis grant in aid. Author contributions: J.S.S.L. designed and performed all experiments. S.S.M. supervised the project. J.S.S.L. and S.S.M. wrote the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/1/eaav1678/DC1

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Mbl LOF results in aberrant Dscam2.10A reporter expression in eye mosaic clones.

Fig. S2. Mbl LOF is associated with increased Dscam2.10A inclusion without affecting other Dscam2 splicing events.

Fig. S3. Mbl is expressed in R cells, neurons, and glia.

Fig. S4. Mbl expression is cell type specific and correlates with Dscam2.10B.

Fig. S5. Neurons overexpressing mbl phenocopy Dscam2 single-isoform mutants.

Table S1. List of tested RNAi lines that did not derepress Dscam2.10A in R cells.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Pan Q., Shai O., Lee L. J., Frey B. J., Blencowe B. J., Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat. Genet. 40, 1413–1415 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang E. T., Sandberg R., Luo S., Khrebtukova I., Zhang L., Mayr C., Kingsmore S. F., Schroth G. P., Burge C. B., Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature 456, 470–476 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iijima T., Iijima Y., Witte H., Scheiffele P., Neuronal cell type-specific alternative splicing is regulated by the KH domain protein SLM1. J. Cell Biol. 204, 331–342 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lah G. J.-e., Li J. S., Millard S. S., Cell-specific alternative splicing of Drosophila Dscam2 is crucial for proper neuronal wiring. Neuron 83, 1376–1388 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomioka M., Naito Y., Kuroyanagi H., Iino Y., Splicing factors control C. elegans behavioural learning in a single neuron by producing DAF-2c receptor. Nat. Commun. 7, 11645 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell T. J., Thaler C., Castiglioni A. J., Helton T. D., Lipscombe D., Cell-specific alternative splicing increases calcium channel current density in the pain pathway. Neuron 41, 127–138 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norris A. D., Gao S., Norris M. L., Ray D., Ramani A. K., Fraser A. G., Morris Q., Hughes T. R., Zhen M., Calarco J. A., A pair of RNA-binding proteins controls networks of splicing events contributing to specialization of neural cell types. Mol. Cell 54, 946–959 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schreiner D., Nguyen T.-M., Russo G., Heber S., Patrignani A., Ahrné E., Scheiffele P., Targeted combinatorial alternative splicing generates brain region-specific repertoires of neurexins. Neuron 84, 386–398 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilsen T. W., Graveley B. R., Expansion of the eukaryotic proteome by alternative splicing. Nature 463, 457–463 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanchette M., Green R. E., MacArthur S., Brooks A. N., Brenner S. E., Eisen M. B., Rio D. C., Genome-wide analysis of alternative pre-mRNA splicing and RNA-binding specificities of the Drosophila hnRNP A/B family members. Mol. Cell 33, 438–449 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Markovtsov V., Nikolic J. M., Goldman J. A., Turck C. W., Chou M.-Y., Black D. L., Cooperative assembly of an hnRNP complex induced by a tissue-specific homolog of polypyrimidine tract binding protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 7463–7479 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Underwood J. G., Boutz P. L., Dougherty J. D., Stoilov P., Black D. L., Homologues of the Caenorhabditis elegans Fox-1 protein are neuronal splicing regulators in mammals. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 10005–10016 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warzecha C. C., Sato T. K., Nabet B., Hogenesch J. B., Carstens R. P., ESRP1 and ESRP2 are epithelial cell-type-specific regulators of FGFR2 splicing. Mol. Cell 33, 591–601 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuroyanagi H., Kobayashi T., Mitani S., Hagiwara M., Transgenic alternative-splicing reporters reveal tissue-specific expression profiles and regulation mechanisms in vivo. Nat. Methods 3, 909–915 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohno G., Hagiwara M., Kuroyanagi H., STAR family RNA-binding protein ASD-2 regulates developmental switching of mutually exclusive alternative splicing in vivo. Genes Dev. 22, 360–374 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calarco J. A., Superina S., O'Hanlon D., Gabut M., Raj B., Pan Q., Skalska U., Clarke L., Gelinas D., van der Kooy D., Zhen M., Ciruna B., Blencowe B. J., Regulation of vertebrate nervous system alternative splicing and development by an SR-related protein. Cell 138, 898–910 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKee A. E., Minet E., Stern C., Riahi S., Stiles C. D., Silver P. A., A genome-wide in situ hybridization map of RNA-binding proteins reveals anatomically restricted expression in the developing mouse brain. BMC Dev. Biol. 5, 14 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Q., Abruzzi K. C., Rosbash M., Rio D. C., Striking circadian neuron diversity and cycling of Drosophila alternative splicing. eLife 7, e35618 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Funada M., Hara H., Sasagawa H., Kitagawa Y., Kadowaki T., A honey bee Dscam family member, AbsCAM, is a brain-specific cell adhesion molecule with the neurite outgrowth activity which influences neuronal wiring during development. Eur. J. Neurosci. 25, 168–180 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Millard S. S., Lu Z., Zipursky S. L., Meinertzhagen I. A., Drosophila dscam proteins regulate postsynaptic specificity at multiple-contact synapses. Neuron 67, 761–768 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Millard S. S., Flanagan J. J., Pappu K. S., Wu W., Zipursky S. L., Dscam2 mediates axonal tiling in the Drosophila visual system. Nature 447, 720–724 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J. S., Shin G. J.-e., Millard S. S., Neuronal cell-type-specific alternative splicing: A mechanism for specifying connections in the brain? Neurogenesis 2, e1122699 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerwin S. K., Li J. S. S., Noakes P. G., Shin G. J.-e., Millard S. S., Regulated alternative splicing of Drosophila Dscam2 is necessary for attaining the appropriate number of photoreceptor synapses. Genetics 208, 717–728 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tadros W., Xu S., Akin O., Yi C. H., Shin G. J.-e., Millard S. S., Zipursky S. L., Dscam proteins direct dendritic targeting through adhesion. Neuron 89, 480–493 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brand A. H., Perrimon N., Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118, 401–415 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mondal K., VijayRaghavan K., Varadarajan R., Design and utility of temperature-sensitive Gal4 mutants for conditional gene expression in Drosophila. Fly 1, 282–286 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pascual M., Vicente M., Monferrer L., Artero R., The Muscleblind family of proteins: An emerging class of regulators of developmentally programmed alternative splicing. Differentiation 74, 65–80 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kania A., Salzberg A., Bhat M., D'Evelyn D., He Y., Kiss I., Bellen H. J., P-element mutations affecting embryonic peripheral nervous system development in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 139, 1663–1678 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Begemann G., Paricio N., Artero R., Kiss I., Pérez-Alonso M., Mlodzik M., muscleblind, a gene required for photoreceptor differentiation in Drosophila, encodes novel nuclear Cys3His-type zinc-finger-containing proteins. Development 124, 4321–4331 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irion U., Drosophila muscleblind codes for proteins with one and two tandem zinc finger motifs. PLOS ONE 7, e34248 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Artero R., Prokop A., Paricio N., Begemann G., Pueyo I., Mlodzik M., Perez-Alonso M., Baylies M. K., The muscleblind gene participates in the organization of Z-bands and epidermal attachments of Drosophila muscles and is regulated by Dmef2. Dev. Biol. 195, 131–143 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee T., Luo L., Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron 22, 451–461 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brouwer J., Nagelkerke D., den Heijer P., Ruiter J. H., Mulder H., Begemann M. J. S., Lie K. I., Analysis of atrial sensed far-field ventricular signals: A reassessment. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 20, 916–922 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diao F., Ironfield H., Luan H., Diao F., Shropshire W. C., Ewer J., Marr E., Potter C. J., Landgraf M., White B. H., Plug-and-play genetic access to Drosophila cell types using exchangeable exon cassettes. Cell Rep. 10, 1410–1421 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bargiela A., Llamusi B., Cerro-Herreros E., Artero R., Two enhancers control transcription of Drosophila muscleblind in the embryonic somatic musculature and in the central nervous system. PLOS ONE 9, e93125 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nern A., Pfeiffer B. D., Rubin G. M., Optimized tools for multicolor stochastic labeling reveal diverse stereotyped cell arrangements in the fly visual system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E2967–E2976 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan L., Zhang K. X., Pecot M. Y., Nagarkar-Jaiswal S., Lee P.-T., Takemura S. Y., McEwen J. M., Nern A., Xu S., Tadros W., Chen Z., Zinn K., Bellen H. J., Morey M., Zipursky S. L., Ig superfamily ligand and receptor pairs expressed in synaptic partners in Drosophila. Cell 163, 1756–1769 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vicente M., Monferrer L., Poulos M. G., Houseley J., Monckton D. G., O'Dell K. M. C., Swanson M. S., Artero R. D., Muscleblind isoforms are functionally distinct and regulate α-actinin splicing. Differentiation 75, 427–440 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Houseley J. M., Garcia-Casado Z., Pascual M., Paricio N., O'Dell K. M. C., Monckton D. G., Artero R. D., Noncanonical RNAs from transcripts of the Drosophila muscleblind gene. J. Hered. 97, 253–260 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ashwal-Fluss R., Meyer M., Pamudurti N. R., Ivanov A., Bartok O., Hanan M., Evantal N., Memczak S., Rajewsky N., Kadener S., circRNA biogenesis competes with pre-mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell 56, 55–66 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li L. B., Yu Z., Teng X., Bonini N. M., RNA toxicity is a component of ataxin-3 degeneration in Drosophila. Nature 453, 1107–1111 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norris A. D., Gracida X., Calarco J. A., CRISPR-mediated genetic interaction profiling identifies RNA binding proteins controlling metazoan fitness. eLife 6, e28129 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Machuca-Tzili L. E., Buxton S., Thorpe A., Timson C. M., Wigmore P., Luther P. K., Brook J. D., Zebrafish deficient for Muscleblind-like 2 exhibit features of myotonic dystrophy. Dis. Model. Mech. 4, 381–392 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang H., Wahlin K. J., McNally M., Irving N. D., Adler R., Developmental regulation of muscleblind-like (MBNL) gene expression in the chicken embryo retina. Dev. Dyn. 237, 286–296 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cerro-Herreros E., Fernandez-Costa J. M., Sabater-Arcis M., Llamusi B., Artero R., Derepressing muscleblind expression by miRNA sponges ameliorates myotonic dystrophy-like phenotypes in Drosophila. Sci. Rep. 6, 36230 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Monferrer L., Artero R., An interspecific functional complementation test in Drosophila for introductory genetics laboratory courses. J. Hered. 97, 67–73 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ule J., Jensen K. B., Ruggiu M., Mele A., Ule A., Darnell R. B., CLIP identifies Nova-regulated RNA networks in the brain. Science 302, 1212–1215 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McMahon A. C., Rahman R., Jin H., Shen J. L., Fieldsend A., Luo W., Rosbash M., TRIBE: Hijacking an RNA-editing enzyme to identify cell-specific targets of RNA-binding proteins. Cell 165, 742–753 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/1/eaav1678/DC1

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Mbl LOF results in aberrant Dscam2.10A reporter expression in eye mosaic clones.

Fig. S2. Mbl LOF is associated with increased Dscam2.10A inclusion without affecting other Dscam2 splicing events.

Fig. S3. Mbl is expressed in R cells, neurons, and glia.

Fig. S4. Mbl expression is cell type specific and correlates with Dscam2.10B.

Fig. S5. Neurons overexpressing mbl phenocopy Dscam2 single-isoform mutants.

Table S1. List of tested RNAi lines that did not derepress Dscam2.10A in R cells.