Abstract

Aims

The aims of this study were to assess the effectiveness of self-efficacy-focused education on health outcomes in persons with diabetes and review the strategies employed in the interventions.

Background

The traditional educational interventions for persons with diabetes were insufficient to achieve the desired outcomes. Self-efficacy-focused education has been used to regulate the blood sugar level, behaviors, and psychosocial indicators for persons with diabetes.

Design

This study is a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

Studies on the effectiveness of self-efficacy-focused education in persons with diabetes were searched in six databases from inception until January 2018. The data were extracted and the quality of literature was assessed independently. Review Manager 5.3 was applied for the meta-analysis. Besides, the findings were summarized for narrative synthesis.

Results

Sixteen trials with 1,745 participants were included in the systematic review and ten trails with 1,308 participants in the meta-analysis. The meta-analysis for A1C, self-efficacy, self-management behaviors, knowledge, and quality of life (QOL) were represented in four, six, six, three, and three studies, respectively. The findings indicated that self-efficacy-focused education would probably reduce A1C, enhance self-efficacy, regulate self-management behaviors, increase knowledge, and improve the QOL for patients with diabetes. Weak quality studies, limited participants, and heterogeneity hindered the results pooled of the other secondary outcomes of fasting blood glucose, 2-hour plasma glucose, weight, weight circumference, body mass index, plasma lipid profile, and other psychological indicators. Goal setting, self-management skills practicing and recording, peer models, demonstration, persuasion by health providers, and positive feedback were the most commonly used strategies in the interventions. However, physiological/emotion arousal strategies were relatively less applied and varied significantly.

Conclusion

Individuals with diabetes may benefit a lot from the self-efficacy-focused education. However, insufficient high-quality studies, short-term follow-up period, relatively deficient physiological/emotion strategies, and incomplete outcome assessments were the drawbacks in most studies. Establishing satisfactory self-efficacy-focused education and better evaluating the effects were required in further studies.

Keywords: self-efficacy, self-management behavior, diabetes mellitus, diabetes education, review

Introduction

Nearly 425 million adults worldwide lived with diabetes in 2017, and it is projected that it will reach 629 million by 2045. Moreover, diabetes may lead to secondary complications, which accounted for 10.7% of the global all-cause mortality among the individuals aged between 20 and 79 years.1 Diabetes education is a cornerstone of the diabetes care. Diabetes management is a complex daily work consisting of adjusting diet, performing exercise, conducting self-monitoring, and taking medicine. The traditional diabetes educational interventions, which merely provided the related knowledge, were inadequate to achieve the expected effects.2,3 Furthermore, the behavior change theories were applied in few studies on diabetes education.4 A variety of research studies manifested that the self-care behaviors of persons with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) were suboptimal.5–9 Besides, poor self-efficacy was considered as an extreme disadvantage of managing diabetes.10

The notion of self-efficacy originated from the social cognitive theory and developed into its related theory.11,12 According to the theory, self-efficacy is the individual’s belief that related to specific behavior in a special setting, which can be modified by four sources of information, including performance accomplishments, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion, and physiological/emotion arousal.11,12 Satisfactory results may be achieved when an educational intervention properly combined the above information. In addition, self-efficacy can regulate human behaviors based on the theory.

Diabetes educational interventions based on the self-efficacy theory were defined as self-efficacy-focused education.13,14 Literature reviews indicated that an educational intervention supported by the related theory may achieve more satisfactory results on reducing blood glucose levels.15,16 As far as we know, there was no literature review interpreting the effects of self-efficacy-focused education in patients with diabetes and the strategies used in the interventions. In addition, self-efficacy educational interventions for patients with diabetes on health outcomes were inconsistent.14,17–20 As a consequence, the objectives of the review were to evaluate the effectiveness of self-efficacy-focused education on health outcomes in patients with diabetes and review the strategies employed in the self-efficacy educational interventions.

Methods

In this review, combined searching with screening the literature, the reporting was based upon PRISMA.21

Eligibility

Types of studies

Studies using experimental designs included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental approaches, or mixed method studies that included RCTs or quasi-experimental designs.

Types of participants

The ages of all the participants were ≥17 years, and all the participants were diagnosed with T2DM or T1DM unless the participants only included T1DM patients.

Types of interventions

The interventions should be developed and implemented based on the principle sources of information proposed by Bandura with detailed descriptions.11,12 Performance accomplishments referred to individuals’ direct experience originated from their own personal practices, which would play a crucial role in the establishment of self-efficacy under specific circumstances. Moreover, vicarious experience was defined as individual’s learning from observing and absorbing the successful behaviors or achievements from others. In addition, verbal persuasion indicated that individuals were convinced to believe that they can accomplish and succeed in a task by providing knowledge, instructions, and advice. Besides, physiological/emotion arousal was regarded as individuals’ psychological state adjustment. The contents of the self-efficacy-focused education for patients with diabetes mainly included education on any of the following aspects: diet adjustment, exercising, foot care, self-monitoring, and medication.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcomes included A1C, diabetes self-efficacy, and diabetes self-management behaviors. Weight control (weight, body mass index [BMI], and weight circumference [WC]), other indicators of blood sugar level (fasting blood glucose [FBG] and 2-hour plasma glucose [2 h-PG]), plasma lipid profile (total cholesterol [TC], low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL-C], high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C], and triglycerides [TG]), and other psychosocial indicators (diabetes knowledge, diabetes distress, depression, and QOL belonged to the secondary outcomes.

Data source and search strategy

Six databases including PubMed, Web of Science, EBSCO, CNKI, Wanfang, and SinoMed were systematically searched for the articles published from inception until January 2018. The terms of “self efficacy,” “self-efficacy,” “efficacy, self,” “diabet*,” and “educat*” were combined for searching. Articles published in English or Chinese language were included. The additional articles were identified through the references of the included studies. The selection of articles were reviewed by two investigators independently. A discussion or an arbitration was arranged when the two investigators were inconsistent with the inclusion of studies.

Extraction and quality appraisal of studies

The study characteristics including study location, design, sample, strategies of intervention, instruments, outcome measures, and so on were extracted. The Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies22 was applied to conduct the quality appraisal. The components of the quality tool included six aspects of bias of selection, research design, confounders in studies, blinding issue, methods of data collection, and withdrawals/dropouts of participants. Each criteria was rated in 3, 2, or 1 point, corresponding to the quality of strong, moderate, or weak, respectively. The overall rating in the study was determined by the total of six-component rating points. To be specific, two or more weak ratings in a study were defined as weak quality, less than four strong ratings and one weak rating as moderate quality, and no weak ratings and at least four strong ratings as strong quality.

Data analysis

In terms of participants, interventions, and outcomes, the indicators of FBG, 2 h-PG, weight, WC, BMI, and plasma lipid profile were presented in a format of a textual summary of findings, while indicators of A1C, self-efficacy, behavior, knowledge, and QOL were pooled for meta-analysis. The mean difference (MD) was calculated when the indicators were measured in the same scale, whereas the standardized mean difference (SMD) was calculated. Chi-squared test was applied to evaluate the heterogeneity, and P<0.10 was considered as heterogeneity. The value I2 quantified the degree of heterogeneity. If I2 was above 50%, a random-effect model was employed, otherwise, a fixed-effect model was used. The sensitivity analysis was conducted by deleting the studies of high risk bias. Besides, Review Manager 5.3 was employed for the meta-analysis.

Results

Study selection and study quality evaluation

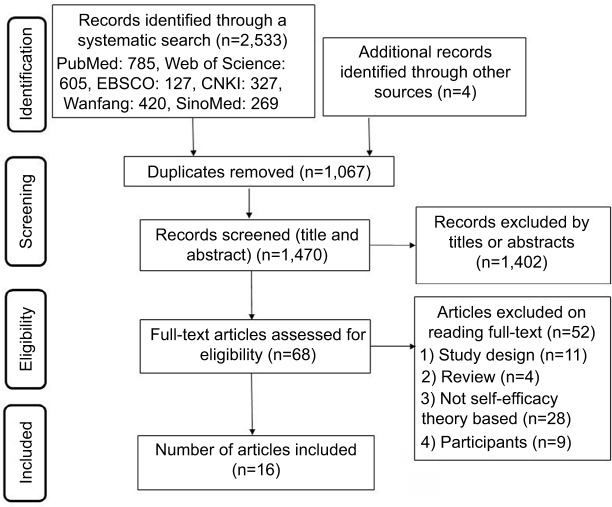

The selecting criteria of self-efficacy-focused education for adults with diabetes are shown in Figure 1. Two thousand five hundred thirty-three abstracts were obtained via the systematic searches, and four additional articles were got through searching the references lists. To sum up, the total number of searched articles was 2,537. After deleting 1,067 duplicate articles and excluding 1,402 studies through reviewing titles and abstracts, there were 68 articles for full-text reading, and 16 studies were finally selected. The other 52 research studies were excluded because of the study population, review format, study design, the use of other theory, or a lack of detailed description regarding how educational interventions were developed and implemented based on the self-efficacy theory. Among the selected 16 studies, 6 were of strong quality, 9 of moderate quality, and 1 of weak quality. The blind outcome assessor or study participants were not reported in the above studies.

Figure 1.

A PRISMA flow diagram describing the study selection criteria.

Characteristics of included studies

Various information including study location, date of publication, sample capacity, and study design is presented in Table 1. Among the 16 included studies, 2 were from Europe, 1 from Turkey, 2 from Thailand, 2 from Malaysia, 3 from Taiwan, and 6 from mainland China. The date of publications ranged from 2006 to 2017 and the sample capacity of studies from 8 to 228. RCT was employed in eight studies and the quasi-experimental design in the others (two pre-post design studies).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author, year, country | Design | Sample I/C | Self-efficacy educational intervention | Outcome indicatorsa | Quality rating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sturt et al23 2006 England | Mixed methods, including pre-post design | 8 | PA: Setting incremental goals to achieve mastery VP: Persuasion by nurses |

Format: 1–1 Duration: 4 months Dose: 20–30 minutes per session per month (4 times) |

①② | Moderate |

| Wattana et al19 2007 Thailand | RCT | 75/72 | PA: Realistic goal setting VE: Patient who succeeded in self-management behavior was selected as a model VP: Persuasion by nurses and group members PhA: Mediation techniques for reducing stress |

Format: Group and class Duration: Not reported Dose: 120 minutes for a class, 90 minutes per group (4 times), 45 minutes per home visit (2 times) |

①⑥ | Moderate |

| Wangberg18 2008 Norway | RCT | 14/15 | VE: Videos of overcoming barriers from peers’ interviewing (peer modeling) VP: Behavior exercises included monitoring and graphic feedback, quizzes with feedback facilitate interactive learning, and knowledge and personal health lectures by videos through the Internet |

Format: Internet Duration: 1 month Dose: Not reported |

②③ | Moderate |

| Shi et al17 2010 China | RCT | 77/80 | PA: Patients’ return-demonstration, and small goal achievement VE: Combining videos of role models with a peer model at the clinic, and researchers’ demonstration VP: Persuasion by researchers |

Format: Group Duration: 1 month Dose: 60–120 minutes per session per group (4 times) |

②③ | Strong |

| Tan et al26 2011 Malaysia | RCT | 82/82 | PA: Practice VE: Discuss self-care, evidence-based studies with patients, and praise the participants’ achievement VP: Explore approaches to overcome self-care deficits based on the patient’s past experience, and identify patient’s barriers and solutions PhA: Identify emotional problems |

Format: 1–1 Duration: 3 months Dose: Not reported |

①③④ | Strong |

| Wu et al14 2011 Taiwan | RCT | 72/73 | PA: Goal setting by sheets VE: Ten minutes DVD viewing, booklet presented stories of diabetes patients, and experience sharing by the role model as peer support VP: Persuasion by nurses |

Format: Group Duration: Not reported Dose: 60 minutes per session per group (4 times), 10 minute DVD viewing, receive booklet, and telephone follow-up |

②③ | Strong |

| Wu et al,32 2011 Taiwan | Quasi-experimental design | 72/73 | PA: Goal setting VE: Ten minutes DVD viewing, booklet presented stories of patients, experience sharing, and peer support VP: Persuasion by nurses |

Format: Group Duration: 4 months Dose: 60 minutes per session per group (4 times), 10 minute DVD viewing, receive booklet, and telephone follow-up |

⑤⑥ | Strong |

| Wu et al25 2013 Taiwan | Quasi-experimental design | 147/81 | PA: Self-goal-setting VE: Ten minutes DVD viewing, diabetes self-care handbook, role model, and peer support VP: Persuasion by nurses, and positive feedback |

Format: Group Duration: 1 month Dose: 60 minutes per session per group (4 times), 10 minute DVD viewing |

①②③⑤ | Strong |

| Cai and Hu24 2016 China | Quasi-experimental design | 29/28 | PA: Progressive goal setting, diet plan making, return-demonstration, repetition, review, and reinforcement VE: Peer modeling, successful examples, demonstration, and role-play VP: Persuasion by researchers and performance feedback PhA: Discuss diabetes concerns, encourage and reward, express empathy and caring, reflective listening, and humor |

Format: Group Duration: 7 weeks Dose: Not reported |

①②③④⑥ | Moderate |

| Biçer and Enç30 2016 Turkey | RCT | 45/45 | PA: Practice VE: Demonstration VP: Persuasion by researchers and education booklet for patients |

Format: 1–1 Duration: Not reported Dose: Not reported |

②③④ | Moderate |

| Wichit et al20 2017 Thailand | RCT | 70/70 | PA: Self-goal setting, design personal action plans, and practice specialized skills (meal planning, physical activities, problem solving, and diabetes-related complications) VE: Models of success to other participants VP: Encourage patients to expand their skills and activities when initiating life-style changes |

Format: Group Duration: 9 weeks Dose: 120 minutes per session per group (3 times) |

①②③④⑥ | Strong |

| Sharoni et al13 2017 Malaysia | Pre-post design | 31 | PA: Small and realistic steps VE: Symbolic modeling by pamphlet, and patients as live models VP: Persuasion by researchers and nurses PhA: Weekly visit by local nurse for emotional support |

Format: Group Duration: 1 month Dose: 30 minutes per seminar (4 times) |

②③④⑥ | Moderate |

| Li et al29 2013 China | Quasi-experimental design | 50/50 | PA: Dietary calorie calculation and recording, and healthy behavior recording VE: Experience sharing, live modeling, and demonstration VP: Persuasion by nurses and simplified diabetes booklet |

Format: Group Duration: 6 weeks Dose: 60 minutes per discussion (6 times), 60 minutes per group (6 times) |

①③ | Weak |

| Zhang et al27 2014 China | Quasi-experimental design | 49/55 | PA: Dietary calorie calculation and recording, and good behavior recording VE: Discussion and live modeling VP: Persuasion by nurses, CD viewing on diabetes-related knowledge, and simplified diabetes booklet |

Format: Group Duration: 6 weeks Dose: 60 minutes per discussion (6 times), 60 minutes per group (6 times) |

①③ | Moderate |

| Zhao et al28 2016 China | Quasi-experimental design | 49/55 | PA: Dietary calorie calculation, dietary, exercise and cessation recording, and healthy behavior recording VE: Discussion, share experience, and live modeling VP: Persuasion by nurses, and simplified diabetes booklet |

Format: A class Duration: 6 weeks Dose: 120 minutes per class per week (6 times) |

①③ | Moderate |

| Mao and Fang,31 2017 China | RCT | 48/48 | PA: Goal setting, behavior contract, evaluation, and feedback regarding behavior; diet and exercise diary; and positive attribution VE: Model demonstration, experience sharing, and “Wechat” communication VP: Persuasion by physiologist and nurse (cognitive intervention and health lecture), and healthy knowledge through the Internet PhA: Relaxing therapy, psychological consulting, and family support |

Format: A class Duration: 8 weeks Dose: 60 minutes per class per week (4 times), 60 minutes per class per week (8 times) |

③⑤ | Moderate |

Notes:

Outcome indicators: ①metabolic controls, ②self-efficacy, ③behavior, ④knowledge, ⑤other psychological indicators, and ⑥quality of life.

Abbreviations: I/C, intervention group/control group; PA, performance accomplishments; PhA, physiological arousal; RCT, randomized controlled trial; VE, vicarious experience; VP, verbal persuasion.

In Table 1, verbal persuasion was used in all studies, performance accomplishments in 15 studies, vicarious experience in 15 studies, and physiological/emotion arousal in 5 studies. Five studies employed four sources of information when developing and implementing the educational interventions. Strategies such as goal-setting were predominately applied for performance accomplishments, followed by practicing diabetes self-management skills, recording behavior, patients’ return-demonstration, making diabetes-related plan, repetition, review and reinforcement, small and realistic steps, behavior contract, evaluation and feedback regarding behavior, and positive attribution. Successful experience provided by a live peer model was primarily applied in vicarious experience, followed by videos, booklets, other elements, such as demonstration and role-play. Verbal persuasion was mainly provided by nurses, followed by researchers, education booklets, group members, and psychologists. Besides, personal heath lectures and other healthy knowledge can be obtained through the Internet. Moreover, performance feedback, encouragement, and the identification of barriers and solutions were also employed in the verbal persuasion. For the physiological/emotion arousal aspects, the studies based on the strategy substantially varied and contained psychological consulting, discussion and identification of concerns, encouragement and reward, empathy and caring, reflective listening, mediation techniques, humor, relaxation therapy, and emotional support by nurses and family members.

Group format and face-to-face delivery were used in most of the studies. The durations of the interventions ranged from 4 to 16 weeks, the number of education modules from 3 to 12, the length of each module from 20 to 120 minutes, and the durations of research from 1 to 6 months. Nine studies measured self-efficacy, 13 studies measured the behavior of participants, 8 studies evaluated both of the above indicators, and 6 studies detected A1C.

Outcomes

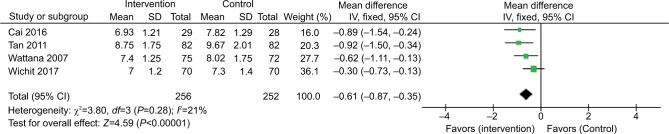

The metabolic controls

The improvement of A1C 3 months post intervention was reported in one study.23 In addition, the changes in A1C between two groups were represented in five studies shown in Table 2, but the follow-up period of one study was only 1 month.19,20,24–26 The overall pooled results (3–6 months) of 508 participants suggested that A1C reduced significantly (MD: −0.62%, 95% CI: −0.92% to −0.33%, P<0.001), with a heterogeneity of I2=21%, which favored the intervention group (Figure 2). A study with high risk bias was deleted for the sensitivity analysis. The results of A1C remained effective (MD: −0.78%, 95% CI: −0.87% to −0.35%, P<0.001), with a heterogeneity of I2=0%. Another study conducted in Taiwan was excluded as well. The outcomes of A1C maintained statistically significant (MD: −0.55%, 95% CI: −0.84% to −0.27%, P<0.001) with a heterogeneity of I2=32%.

Table 2.

Outcomes of included studies

| Study | Metabolic controls | Self-efficacy | Behavior | Knowledge | Other psychological indicators | QOL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sturt et al23 2006 | A1C: + (at 3 months) | Scale: DMSES Result: + (at 3 months) |

None | None | None | None |

| Wattana et al19 2007 | A1C: + (at 6 months) | None | None | None | None | Scale: SF-36 Result: + (at 6 months) |

| Wangberg18 2008 | None | Scale: PCS Result: + (at 1 month) |

Scale: SDSCA Result: + (at 1 month) |

None | None | None |

| Shi et al17 2010 | None | Scale: DMSES Result: + (at 1, 4 months) |

Scale: SDSCA Result: + (at 1, 4 months) |

None | None | None |

| Tan et al26 2011 | A1C: + (at 3 months) Weight: − (at 3 months) |

None | Scale: RDSA Result: none (at 3 months) |

Scale: included in RDSA Result: + (at 3 months) |

None | None |

| Wu et al14 2011 | None | Scale: DMSES Result: + (at 3, 6 months) |

Scale: SDSCA Result: + (at 3, 6 months) |

None | None | None |

| Wu et al32 2011 | None | None | None | None | Scale: CES-D Result: − (at 3, 6 months) |

Scale: SF-12 Result: − (at 3, 6 months) |

| Wu et al25 2013 | A1C: + (at 1 months) Weight: − (at 1 months) WC: − (at 1 months) |

Scale: PTES Result: + (at 1 month) |

Scale: SDSCA Result: + (at 1 month) |

None | Scale: DASS-21 and WHO-5 Result: + (DASS-21), − (WHO-5) (at 1 month) |

None |

| Cai and Hu24 2016 | A1C: + (at 3 months) BMI: + (at 3 months) WC: + (at 3 months) TC, TG, HDL-C and LDL-C:− (at 3 months) |

Scale: DMSES Result: + (at 3 months) |

Scale: SDSCA Result: + (at 3 months) |

Scale: DKQ-24 Result: + (at 3 months) |

None | Scale: SF-36 Result: + (at 3 months) |

| Biçer and Enç30 2016 | None | Scale: DFCSES Result: + (at 1, 3, 6 months) |

Scale: FSCBC Result: + (at 1, 3, 6 months) |

Scale: DFKQ-5 Result: + (at 1, 3, 6 months) |

None | None |

| Wichit et al20 2017 | A1C: − (at 13 weeks) | Scale: DMSES Result: + (at 5, 13 weeks) |

Scale: SDSCA Result: + (at 5, 13 weeks) |

Scale: DKQ-24 Result:+ (at 5, 13 weeks) |

None | Scale: SF-12 Result: − (at 5, 13 weeks) |

| Sharoni et al13 2017 | None | Scale: FCC and a self-made questionnaire Result: + (at 3 months) |

Scale: DFSBS Result: + (at 3 months) |

Scale: Self-made questionnaire Result: + (at 3 months) |

None | Scale: NFUS-QOL Result:+ (at 3 months) |

| Li et al29 2013 | FBG: + (at 3, 6 months) 2 h-PG: + (at 3, 6 months) |

None | Scale: Subscale of SDSCA Result: + (at 3, 6 months) |

None | None | None |

| Zhang et al27 2014 | FBG: + (at 3, 6 months) | None | Scale: Subscale of SDSCA Result: + (at 3, 6 months) |

None | None | None |

| Zhao et al28 2016 | FBG: + (at 3, 6 months) 2 h-PG: + (at 3, 6 months) |

None | Scale: SDSCA Result: + (at 3, 6 months) |

None | None | None |

| Mao and Fang31 2017 | None | None | Scale: SDSCA Result: + (at 2 months) |

None | Scale: DDS Result: + (at 2 months) |

None |

Notes: “+”, Significant post intervention vs baseline/intervention group vs control group. “−”, not significant post intervention vs baseline/intervention group vs control group. None, cannot extract.

Abbreviations: 2 h-PG, 2-hour plasma glucose; BMI, body mass index; CSF-36, 36-item Short-Form health survey; DASS-21, short form version of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale; DDS, Diabetes Distress Scale; DFCSES, Diabetic Foot Care Self-Efficacy Scale; DFKQ-5, Diabetes Foot Knowledge Questionnaire-5; DFSBS, Diabetes Foot Self-care Behavior Scale; DKQ-24, Diabetes-related Knowledge Questions-24; DMSES, Diabetes Management Self-Efficacy Scale; ES-D, Center for Epidemiology studies Short Depression scale; FBG, fasting blood glucose; FCC, Foot Care Confidence scale; FSCBC, Foot Self-Care Behavior Scale; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NFUS-QOL, Neuropathy and Foot Ulcer Specific Quality of Life; PCS, Perceived Competence Scales; PTES, Perceived Therapeutic Efficacy Scale; RDSA, Revised Diabetes Self-Care Activity; SDSCA, Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities; SESD, Self-Efficacy Diabetes Scale; SF-12, Health-related quality of life Short Form-12; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; WC, weight circumstances; WHO-5, Five WHO Well-Being Index.

Figure 2.

Efficacy of self-efficacy education interventions on A1C.

The positive effects on FBG and 2 h-PG in the intervention group vs the control group were identified in three and two research studies, respectively, and these variables were improved at the end of the studies compared with the baseline.27–29 The weight of the patients was assessed in two studies; however, only one of them represented a significant difference between the groups.25,26 WC in the intervention group was found to be well-regulated compared with the control group in two studies.24,25 Among all the included studies, only one study involved in the positive result of BMI and a non-significant result of TC, TG, HDL-C, and LDL-C (Table 2).24

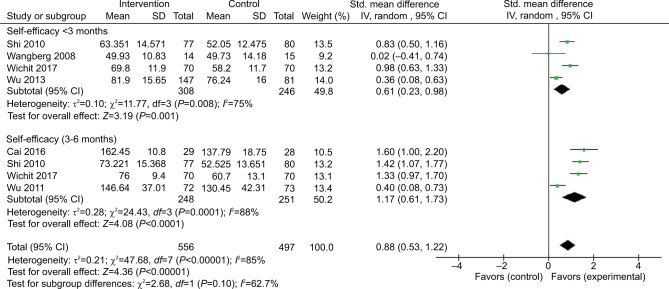

Self-efficacy

A positive impact on self-efficacy post intervention was reported in two studies.13,23 The foot care self-efficacy of the participants was examined and a significant difference was found. Another six studies reported the changes in self-efficacy between the two groups.14,17,18,20,24,25 However, the outcomes of self-efficacy were heterogeneous, namely the total self-efficacy of the participants was measured on different scales, including the Diabetes Management Self-Efficacy Scale (DMSES), the Perceived Competence Scales (PCS), and the Perceived Therapeutic Efficacy Scale (PTES) (Table 2). The pooled results (<3 months) of 554 participants revealed that self-efficacy can be improved significantly (SMD: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.23–0.98, P=0.001), and the results of 3–6 months also represented a positive effect (SMD: 1.17, 95% CI: 0.61–1.73, P<0.001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Efficacy of self-efficacy education interventions on self-efficacy.

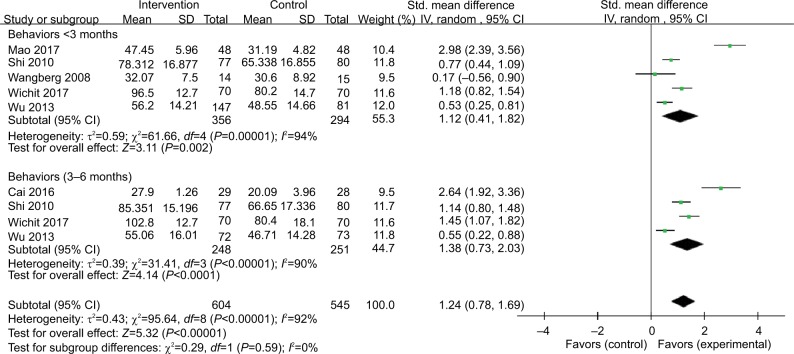

Behaviors

The positive self-management behavior improvements in the intervention group vs the control group were published in eleven studies,14,17,18,20,24,25,27–31 and one study identified a prominent improvement 3 months post intervention.13 Similar to the results of self-efficacy, behavioral outcomes were heterogeneous, most studies employed the scale of Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA) to evaluate the self-management behaviors. The Revised Diabetes Self-Care Activity (RDSA), the Foot Self-Care Behavior Scale (FSCBC), and the Diabetes Foot Self-care Behavior Scale (DFSBS) were employed in one study, respectively. In addition, three studies examined the dietary self-management behaviors using the subscale of SDSCA (Table 2). The pooled results (<3 months) of 707 participants showed that self-management behaviors can be improve greatly (SMD: 1.12, 95% CI: 0.41–1.82, P<0.001), and the results of 3–6 months also revealed a positive effect (SMD: 1.38, 95% CI: 0.73–2.03, P<0.001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Efficacy of self-efficacy education interventions on self-management behaviors.

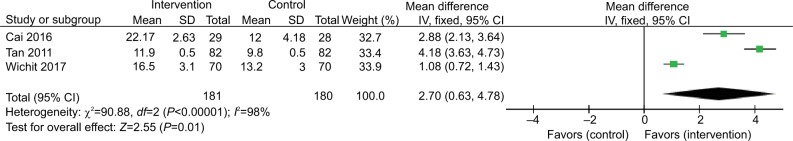

Knowledge and other psychological indicators

The questionnaires employed to assess the outcome of knowledge varied substantially. The RDSA, the Diabetes Foot Knowledge Questionnaire-5 (DFKQ-5), and the Diabetes-related Knowledge Questions-24 (DKQ-24) were used in one, one, and two studies, respectively. While the remaining study employed a self-made questionnaire based on the literatures. Among the included studies, one study indicated the improvement of knowledge post intervention,13 and another study assessed the foot care knowledge.30 The other three studies reported changes in knowledge between the two groups (Table 2).20,24,26 The pooled results (3–6 months) of diabetes knowledge showed a positive effect (SMD: 2.70, 95% CI: 0.63–4.78, P=0.01) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Efficacy of self-efficacy education interventions on knowledge.

For the aspect of other psychological indicators, three studies substantially varied (Table 2). Depression was measured by the Center for Epidemiology studies Short Depression scale (CES-D) in one study, but no remarkable difference between the two groups was found.32 The short form version of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) was used in one study to evaluate the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. The DASS-21 scores in the intervention group after intervention were much lower than that of the scores in the control group. In addition, the Five WHO Well-Being Index (WHO-5) was applied to inquire about the degree of depression during the past 2 weeks; however, the score of WHO-5 was not significant between the two groups.25 In addition, the diabetes distress was assessed by the Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS) in one study, and the findings indicated that the DDS decreased much more in the intervention group than that in the control group.31

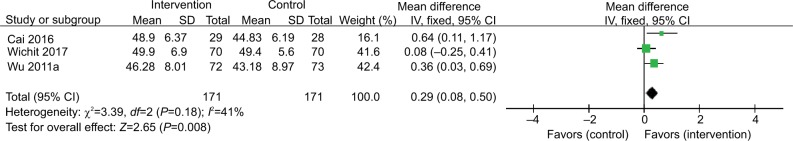

QOL

QOL was estimated in five studies using three instruments, including the 36-item Short-Form health survey (SF-36), the Health-related quality of life Short Form-12 (SF-12), and Neuropathy and Foot Ulcer Specific Quality of Life (NFUS-QOL). Among the five studies, one study used the NFUS-QOL to assess the specific QOL of neuropathy and foot ulcer and reported significant improvements in the physical symptoms of the QOL after 3 months.13 The others reported the changes in QOL between the two groups (Table 2).19,20,24,32 The pooled results (3–6 months) showed a significant improvement in QOL (SMD: 0.29, 95% CI: 0.08–0.50, P=0.008) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Efficacy of self-efficacy education interventions on quality of life.

Discussion

The present systematic review and meta-analysis were based upon 1,745 and 1,308 cases, respectively, which indicated self-efficacy-focused education was beneficial to the patients with diabetes. The self-efficacy-focused education would probably improve blood sugar level, enhance self-efficacy, promote self-management behaviors, increase knowledge, and improve the QOL. Learning strategies of self-efficacy theory including goal setting, self-management skills practicing and recording, peer models, demonstration, persuasion by health providers, and positive feedback were frequently applied in the enhancement of self-efficacy.

The effect of self-efficacy-focused education on blood sugar level in patients with diabetes was statistically positive (A1C reduced 0.61%), which approached a clinically significant level (A1C ≥0.5% was considered clinically significant).33 This is superior than the previous meta-analysis of self-management interventions in T2DM patients with suboptimal blood sugar levels conducted by Li et al (A1C reduced 0.49% in 3–6 months),15 and the other meta-analysis of the self-management education in T2DM patients by Norris et al (A1C decreased nearly 0.26% in 1–3 months and above).34 In addition, the results of A1C by sensitivity analysis were relatively stable. It was mainly because the development and implementation of the interventions were on the basis of self-efficacy theory. Self-efficacy-focused education emphasized on improving self-efficacy of participants with diabetes, and promoting self-management behaviors which were critical for improving blood sugar levels.35 There were predominant promotions of self-efficacy in <3 months and 3–6 months follow-up in the current meta-analysis, and improvements of self-management behaviors were also found. The results were unanimous with the previous reviews of diabetes self-management education36,37 and psychological interventions.38 However, the follow-up durations of the studies were relatively short and high-quality RCT was insufficient; thus, high-quality RCT design with long-term follow-up period should be taken into consideration for the further study. Although all studies were based on self-efficacy theory, only eight studies evaluated both self-efficacy and behaviors. It would be better to measure both self-efficacy and behavioral outcomes and to assess the linkage between them using causal modeling to help explain that self-efficacy was a crux mechanism in achieving behavioral and metabolic improvements.

Knowledge and QOL improved significantly in the current study. Nevertheless, the generalization of the findings should be careful because of the limited studies included. Knowledge provided by traditional education was necessary; however, other factors, for instance, self-efficacy, may be more effective to promote the establishment and maintenance of self-management behaviors. As a consequence, the interventions based on cognitive reframing techniques, which can preferably motivate patients, would produce better results.36,39 QOL was measured by SF-36 and SF-12 which were not specially designed for measuring QOL of persons with diabetes. In general, patients with diabetes often accompanied with other diseases (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, etc); hence, the scores of QOL could be easily affected and disturbed.40 Consequently, a QOL instrument that is specific for patients with diabetes were urgently designed to accurately assess the effects of intervention on QOL.

The outcomes of FBG, 2 h-PG, weight, WC, BMI, plasma lipid profile, and other psychological indicators were expected to be well-analyzed by the meta-analysis, but were failed due to the lack of high-quality studies, limited studies, or heterogeneity. A positive change on the secondary outcomes of FBG and 2 h-PG through comparing the two groups was reported in several studies; however, the quality of one study was considered weak and the number of participants was limited. A meta-analysis manifested that group based self-management education can reduce the level of FBG,37 but there was no strong proof supporting the effect of 2 h-PG. For other secondary outcomes, it was difficult to draw a conclusion on weight, WC, BMI, and plasma lipid profile because of the limited evidence. Likewise, it was quite difficult to determine the effects of self-efficacy-focused education on the other psychological indictors for the huge heterogeneity.

All the included studies were based on the self-efficacy theory, and almost all of them employed the performance accomplishments, vicarious experience, and verbal persuasion when developing and implementing diabetes educational interventions. The researchers of most studies were nurses rather than psychologists, which might be the main reason for the limited usage of physiological/emotion arousal and varied strategies to improve emotion state. Therefore, a multidisciplinary research group that comprised both nursing and psychology disciplines may be much better for developing and delivering the interventions based on self-efficacy theory. Strategies, such as goal setting, directly aroused and affected the motivation of behavior change.12 Moreover, progressive and realistic goal setting step by step would provide a sense of successful experience for the patients. The self-management skills practicing and recording by patients may directly influence their behaviors and strengthened their experiences. The live peer models with mutual characteristics would promote the learning of patients by observing the success of others enhancing self-efficacy. What’s more, peer models may also combine with other media, such as videos and booklets, and it was noted that the experiences and characteristics of the models should be similar to the patients.41 Self-management skills could be mastered through observing the demonstration from educators or group members. Verbal persuasion provided by health providers, mainly by nurses, might be related to the workforce nature of diabetes education, and a review indicated that diabetes education led by nurses could improve the blood glucose levels of patients.42 Positive feedback was the critical means to guide the patients to conduct and persist the self-management behavior.

Limitations

The outcomes may be affected by several limitations. First, most included studies did not employ the RCT designs, which may influence the evidence level of pooled results. Secondly, the sample capacities of most studies were quite limited, and a number of trials had the following biases: blinding, withdrawal, or dropping out. Finally, the duration of the interventions varied greatly, and it was insufficient to determine the long-term effects of the interventions due to short durations of studies.

Conclusion

In this review, relevant data regarding self-efficacy-focused education effects were provided and mutual strategies in the self-efficacy-focused education to enhance self-efficacy, promote behavior change, and achieve optimal blood sugar level were summarized, which facilitated the studies on self-efficacy-focused education for patients with diabetes. In addition, individuals with diabetes mellitus would probably benefit from the self-efficacy-focused education. However, this review indicated that the research designs with high quality were insufficient and there existed several limitations, including short follow-up periods, deficient physiological/emotion arousal strategies, and incomplete outcome assessments. Future studies should emphasize on self-efficacy and employ the frequently used strategies including goal setting, self-management skills practicing and recording, peer models, demonstration, persuasion by health providers, positive feedback, and so on. It is high time to develop and deliver an educational intervention for patients with DM, as well as assess the outcome indicators with a high-quality study design.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.International Diabetes Federation IDF Diabetes Atlas. 8th Edition. 2017. [Accessed August 08, 2018]. [updated 2018]. Available from: https://www.idf.org/our-activities/advocacy-awareness/resources-and-tools/134:idf-diabetes-atlas-8th-edition.html.

- 2.Glasgow RE, Osteen VL. Evaluating diabetes education. Are we measuring the most important outcomes? Diabetes Care. 1992;15(10):1423–1432. doi: 10.2337/diacare.15.10.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lou Q, Wu L, Dai X, Cao M, Ruan Y. Diabetes education in mainland China – a systematic review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(3):336–347. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu P, Xiao X, Wang L, Wang L. Correlation between self-management behaviors and blood glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in community. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2013;38(4):425–431. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-7347.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo XH, Yuan L, Lou QQ. A nationwide survey of diabetes education, self-management and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes in China. Chin Med J. 2012;125(23):4175–4180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wabe NT, Angamo MT, Hussein S. Medication adherence in diabetes mellitus and self management practices among type-2 diabetics in Ethiopia. N Am J Med Sci. 2011;3(9):418–423. doi: 10.4297/najms.2011.3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yusuff KB, Obe O, Joseph BY. Adherence to anti-diabetic drug therapy and self management practices among type-2 diabetics in Nigeria. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30(6):876–883. doi: 10.1007/s11096-008-9243-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Formosa C, Muscat R. Improving diabetes knowledge and self-care practices. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2016;106(5):352–356. doi: 10.7547/15-071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glasgow RE, Toobert DJ, Gillette CD. Psychosocial barriers to diabetes self-Management and quality of life. Diabetes Spectrum. 2001;14(1):33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharoni SKA, Abdul Rahman H, Minhat HS, Shariff Ghazali S, Azman Ong MH. A self-efficacy education programme on foot self-care behaviour among older patients with diabetes in a public long-term care institution, Malaysia: a Quasi-experimental Pilot Study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e014393. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu SF, Lee MC, Liang SY, Lu YY, Wang TJ, Tung HH. Effectiveness of a self-efficacy program for persons with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Nurs Health Sci. 2011;13(3):335–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng L, Sit JW, Choi KC, Chair SY, Li X, He XL. Effectiveness of interactive self-management interventions in individuals with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2017;14(1):65–73. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hampson SE, Skinner TC, Hart J, et al. Behavioral interventions for adolescents with type 1 diabetes: how effective are they? Diabetes Care. 2000;23(9):1416–1422. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.9.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi Q, Ostwald SK, Wang S. Improving glycaemic control self-efficacy and glycaemic control behaviour in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: randomised controlled trial. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(3-4):398–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wangberg SC. An internet-based diabetes self-care intervention tailored to self-efficacy. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(1):170–179. doi: 10.1093/her/cym014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wattana C, Srisuphan W, Pothiban L, Upchurch SL. Effects of a diabetes self-management program on glycemic control, coronary heart disease risk, and quality of life among Thai patients with type 2 diabetes. Nurs Health Sci. 2007;9(2):135–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2007.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wichit N, Mnatzaganian G, Courtney M, Schulz P, Johnson M. Randomized controlled trial of a family-oriented self-management program to improve self-efficacy, glycemic control and quality of life among Thai individuals with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;123:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The PRISMA Group . Transparent Reporting Of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. PRISMA; 2018. [Accessed June 01, 2018]. [updated 2018]: 2018 update. Available from: http://www.prisma-statement.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies method. Resource Details. 2018. [Accessed June 01, 2018]. [updated 2018]. Available from: http://www.nccmt.ca/knowledge-repositories/search/15.

- 23.Sturt J, Whitlock S, Hearnshaw H. Complex intervention development for diabetes self-management. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54(3):293–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai C, Hu J. Effectiveness of a family-based diabetes self-management educational intervention for Chinese adults with type 2 diabetes in Wuhan, China. Diabetes Educ. 2016;42(6):697–711. doi: 10.1177/0145721716674325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu SF, Liang SY, Lee MC, Yu NC, Kao MJ. The efficacy of a self-management programme for people with diabetes, after a special training programme for healthcare workers in Taiwan: a quasi-experimental design. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(17-18):2515–2523. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan MY, Magarey JM, Chee SS, Lee LF, Tan MH. A brief structured education programme enhances self-care practices and improves gly-caemic control in Malaysians with poorly controlled diabetes. Health Educ Res. 2011;26(5):896–907. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang X, An Z, Wang F, Xing F. Effect analysis of the intervention by self-efficacy theory on self-management behavior of rural patients with type-2 diabetes. Mod Prev Med. 2014;41(21):3887–3889, 3900. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao C, Xing F, Li H. Self-efficacy intervention on self-management actions in patients with type 2 diabetes. Med J Chin PAP. 2016;27(9):874–877. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li D, Li D, Xing F, Wang F. Effect of dietary self-management of elderly diabetes using theory of serf-efficacy. J Health Psychol. 2013;21(11):1704–1706. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biçer EK, Enç N. Evaluation of foot care and self-efficacy in patients with diabetes in Turkey: an interventional study. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2016;36(3):334–344. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mao D, Fang F. Practice of self-efficacy intervention for elderly patients with diabetes mellitus. J Nurs Sci. 2017;32(17):25–28. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu SF, Liang SY, Wang TJ, Chen MH, Jian YM, Cheng KC. A self-management intervention to improve quality of life and psychosocial impact for people with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(17-18):2655–2665. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urrechaga E. High-resolution HbA(1c) separation and hemoglobinopathy detection with capillary electrophoresis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;138(3):448–456. doi: 10.1309/AJCPVYW9QZ9EVFXI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, Engelgau MM. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(7):1159–1171. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin K, Park C, Li M, et al. Effects of depression, diabetes distress, diabetes self-efficacy, and diabetes self-management on glycemic control among Chinese population with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;131:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ricci-Cabello I, Ruiz-Pérez I, Rojas-García A, Pastor G, Rodríguez-Barranco M, Gonçalves DC. Characteristics and effectiveness of diabetes self-management educational programs targeted to racial/ethnic minority groups: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. BMC Endocr Disord. 2014;14(1):60. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-14-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steinsbekk A, Rygg LØ, Lisulo M, Rise MB, Fretheim A. Group based diabetes self-management education compared to routine treatment for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:213. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chew BH, Vos RC, Metzendorf M-I, Scholten RJPM, Rutten GEHM, Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group Psychological interventions for diabetes-related distress in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;39(4):D11469. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011469.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ellis SE, Speroff T, Dittus RS, Brown A, Pichert JW, Elasy TA. Diabetes patient education: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52(1):97–105. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Speight J, Reaney MD, Barnard KD. Not all roads lead to Rome – a review of quality of life measurement in adults with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2009;26(4):315–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bandura A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tshiananga JK, Kocher S, Weber C, Erny-Albrecht K, Berndt K, Neeser K. The effect of nurse-led diabetes self-management education on glycosylated hemoglobin and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38(1):108–123. doi: 10.1177/0145721711423978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]