Highlights

-

•

Denosumab, as an iresorptive agent, has a high cost.

-

•

Zoledronic acid treatment is cheap in giant cell tumor of bone.

-

•

Complete response was much better for denosumab than zoledronic acid.

-

•

Zoledronic acid has hypocalcemia and flu-like symptoms as treatment-emergent adverse effects.

-

•

Overall patient survival for denosumab treatment and zoledronic acid treatment was the same.

Keywords: Antiresorptive, Bone density conservation agents, Denosumab, Giant cell tumor of bone, Zoledronic acid

Abbreviations: GCTB, giant cell tumor of bone; US FDA, the United States Food and Drug Administration; EMA, the European Medicines Agency; RANKL, Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β ligand; CONSORT, Consolidated standards of reporting trials; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, the computed tomography; RECIST, response evaluation criteria in solid tumors; AST test, Aspartate aminotransferase test; ALT test, Alanine aminotransferase test; CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; ANOVA, analysis of variance; n, sample size; N, sample population; EORTC, European organization for research and treatment of cancer

Abstract

Background

Although denosumab has been approved as an antiresorptive agent for giant cell tumor of bone, its efficacy has not been proven.

Objectives

To compare the efficacy and safety of denosumab and zoledronic acid treatment in patients with surgically unsalvageable giant cell tumor of bone.

Methods

A total of 250 patients with surgically unsalvageable giant cell tumor of bone were included in this randomized clinical trial. Patients received either subcutaneous denosumab (DB group; 120 mg per 4 weeks plus an additional 120 mg on days 8 and 15; n = 125) or intravenous zoledronic acid (ZA group; 4 mg per 4 weeks; n = 125) for six cycles. Disease status, clinical benefits, treatment-emergent adverse effects, overall survival, and cost of treatment were evaluated during the follow-up period. Statistical significance was determined using 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Denosumab and zoledronic acid had similar tumor responses (p = 0.18) and clinical benefits (p = 0.476). Disease progression was observed in fewer patients in the DB group (1%) than ZA group (2%). Denosumab caused fatigue (p = 0.0004) and back pain (p < 0.0001), while zoledronic acid caused hypocalcemia (p < 0.0001), flu-like symptoms (p = 0.021), hypotension (p = 0.021), and hypokalemia (p = 0.021). Denosumab treatment was markedly more expensive than zoledronic acid treatment (p < 0.0001). The cost to manage treatment-emergent adverse effects was higher for the ZA group than the DB group (p = 0.0425). Overall survival was the same for both treatments (p = 0.066).

Conclusions

Denosumab is a safe but costly alternative to zoledronic acid for treatment of surgically unsalvageable giant cell tumor of bone.

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Giant cell tumor of bone (GCTB) is a locally aggressive osteolytic lesion [1]. It is a rare, generally benign cancer of limb bones [2] that can cause metastases, especially in the lung [1], [3] as well as significant bone destruction [2]. In most cases, GCTB occurs in the long bones of skeletally mature adolescents and young adults. The occurrence rate is slightly higher in females than in males [1]. The development of GCTB is not clearly understood, and its biological behavior is unpredictable [4].

The available treatment options for GCTB involve surgery (intralesional curettage) followed by bone cement packing and/or bone grafting to compensate for resection and restore limb function, with or without adjuvant therapy [3]. Although surgery is the standard treatment [1], [5], local tumor recurrence rates are high due to the absence of effective adjuvant therapies [2], and surgery alone can lead to the mortality of patients [3]. For patients with unsalvageable GCTB, radiotherapy with serial embolization is also a treatment option, but malignant transformation may occur after radiation [6]. Chemotherapeutic agents and bisphosphonates have also been used in GCTB patients, but show inconsistent results [7]. Chinese traditional medicine, e.g. norcantharidin, has demonstrated significant efficacy in GCTB, but its application and efficacy in clinical practice have not been established [2].

In 2013, the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA), followed by the European Medicines Agency (EMA), approved denosumab as an antiresorptive agent for use in unresectable patients and those with surgically unsalvageable GCTB [1], [8]. Denosumab reduces osteoclast-induced bone destruction by inhibiting the interaction of osteoclasts with receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β ligand (RANKL), a key mediator of osteoclast activity [6]. However, the safety profile of denosumab is unknown [8], its efficacy has not yet been proven, and it causes serious treatment-emergent toxic effects [5], [6]. Long-term effects of denosumab treatment are also not well-established [9], and the cost of treatment is high [10], [11]. Therefore, whether denosumab should be regarded as the ‘gold standard’ treatment for patients with GCTB remains an unanswered question, and more information is required to justify its use.

The objectives of this study were to compare the efficacy, safety, and cost between denosumab and zoledronic acid treatment, in adult patients with surgically unsalvageable GCTB.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Drugs and reagents

Denosumab (XGEVA®) was purchased from Amgen Technology (Dublin, Ireland). Zoledronic acid (Zometa®) was purchased from Novartis Pharma Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Normal saline was purchased from Baxter Healthcare Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Calcium (500 mg) and 25-hydroxyvitamin D (400 IU) tablets were purchased from Glenmark Pharmaceuticals Ltd. (Mumbai, India).

2.2. Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was registered at the Research Registry (www.researchregistry.com; UID No. researchregistry4331, 1 January 2015). The protocol (CMU/CL/12/15 dated 25 December 2014) had been approved by the Cancer Hospital of China Medical University review board. The study had adhered to the law of China, the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki, and Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. Informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legally authorized agents regarding the interventions, radiology and pathology tests, and publication of personal data and images (if any) in all formats (hard and/or electronic), irrespective of time and language.

2.3. Inclusion criteria

Patients with histologically confirmed GCTB (by image-guided or open biopsy), admitted from 2 January 2015 to 1 January 2016, were included in the trial. Adult patients aged ≥18 years, weighing ≥50 kg, and with surgically unsalvageable GCTB (e.g. sacral or spinal GCTB, or multiple lesions including pulmonary metastases), and Karnofsky Performance Status scores ≥50% (11-point scale; 0% = death and 100% = no evidence of disease or symptoms [12]) were included in the study.

2.4. Exclusion criteria

Patients with renal impairment (creatinine clearance rate <30 mL/min), asthma, scheduled surgery, a history of hypersensitivity to denosumab or zoledronic acid, pregnancy, active lactation, or who had been receiving radiotherapy/serial embolization were excluded from the trial. Patients with non-GCTB giant-cell-rich tumors, suspected bone sarcoma, brown cell bone tumor, Paget's disease, secondary malignancy, osteonecrosis, osteomyelitis, or jaw and/or dental problems were excluded from the trial. Patients who did not sign an informed consent form or stopped treatment during the trial were excluded from the final analysis.

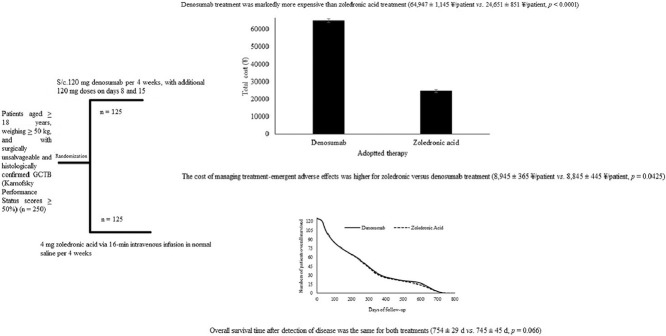

2.5. Design of experiment

A total of 250 patients were subjected to the simple randomization procedure (1:1 ratio). The required sample size was determined, using the online tool OpenEpi 3.01-English ((http://www.openepi.com)), as 125 in each group. The other parameters were set as follows: finite population correction factor (fpc, N), 250; hypothesized percentage frequency of outcome factor, 80 ± 5%; power of randomization, 80%; confidence limits, 5% (α = 0.05); and design effect, 1. The randomization procedure was carried out using opaque envelopes. The physicians participating in the randomization were not involved in any treatment decisions. A CONSORT flow diagram of the study is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of the study. Finite population correction factor (fpc, N), 250; hypothesized percentage frequency of outcome factor, 80 ± 5%; power of randomization, 80%; confidence limits, 5% (α = 0.05); and design effect, 1. GCTB, giant cell tumor of bone. An intention-to-treat analysis method was adopted.

2.6. Interventions

Patients in the DB group received six cycles of denosumab. A cycle was defined as 120 mg denosumab per 4 weeks, with additional 120 mg doses on days 8 and 15, administered subcutaneously in the abdomen, upper thigh, or upper arm [13]. Patients in the ZA group received six cycles of zoledronic acid [14], i.e., 4 mg zoledronic acid via 16-min intravenous infusion in normal saline per 4 weeks [15]. Both groups also received 500 mg calcium [6] with 400 IU 25-hydroxy vitamin D/day, continued as needed by the patient [16]. The interventions comprised six 4-week cycles, where 6 months of denosumab [17] and zoledronic acid [15] have been reported to be sufficient to induce anti-tumor responses.

2.7. Disease status

Every 4 weeks, all patients underwent radiological imaging (X-ray, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT)) [18]; disease status continued to be evaluated for 18 months. All radiological imaging parameters were evaluated by the same radiologist, who had 3 years of experience. Disease status was categorized at the time of enrollment and during the follow-up period, following the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST v1.1) guidelines [19], as either progressive disease (new malignancy appearing), stable disease (presence of targeted lesions), fractional response (decrease of ≥30% in tumor size), or complete response (disappearance of all targeted lesions).

2.8. Clinical benefits

Every 4 weeks, all patients were subjected to a physical examination; any improvements in pain, mobility or functional activity [6] were noted to determine the clinical benefits of the treatment [17]. All physical examination parameters were evaluated by the same physiotherapist, who had 3 years of experience.

2.9. Treatment-emergent adverse events

Adverse events related to medication use were monitored. At the end of each month for 9 months, all patients underwent liver function (ALT, AST, albumin, and bilirubin) and renal function (blood serum creatinine) tests [6], [15]. Other treatment-emergent adverse effects were evaluated over 18 months. All clinical parameters were evaluated by one pathologist, one nephrologist, one hepatologist, one physician, and one hematologist, each of whom had at least 3 years of experience. Events were considered as treatment-emergent adverse events in accordance with Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE, v5.0) [20]. Hospitalization was considered to indicate serious treatment-emergent adverse effects. Overall survival was defined as the period of survival after disease detection [21]. Follow-up to monitor patient survival continued for 2.5 years after the interventions.

2.10. Cost analysis

Cost analysis included the costs of pathology, intervention(s), hospital stay, radiology examination, experts’ fees, and follow-up costs including cost of treating complications and recurrence [11].

2.11. Statistical analysis

InStat (Windows version; GraphPad Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Chi-square tests for independence and one-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) [22] were used for statistical analysis of categorical and continuous data, respectively. Results were considered significant at a 95% confidence level. An intention-to-treat analysis method was adopted.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

Based on cytology, patients with GCTB were categorized into one of three stages (I, II, or III). The other demographic and clinical parameters of the enrolled patients are presented in Table 1, none of which showed a group difference at the time of enrollment (p ≥ 0.01 for all).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and clinical status of the enrolled patients.

| Characteristics | Groups |

Comparison between groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DB | ZA | |||

| Intervention | Denosumab | Zoledronic acid | – | |

| Sample size (Patients enrolled in the study) | 125 | 125 | p-value | |

| Gender | Male | 49 (39) | 53 (42) | 0.7 |

| Female | 76 (61) | 72 (58) | ||

| Age (years) | Minimum | 27 | 25 | 0.068 |

| Maximum | 46 | 44 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 34.15 ± 3.15 | 33.45 ± 2.89 | ||

| Weight (kg) | Minimum | 51 | 52 | 0.062 |

| Maximum | 61 | 61 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 52.45 ± 2.88 | 53.15 ± 3.01 | ||

| aKarnofsky Performance Status | Minimum | 52 | 54 | 0.078 |

| Maximum | 72 | 77 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 61.15 ± 2.18 | 62.01 ± 4.98 | ||

| Location of GCTB lesion | Femur | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 0.99 |

| Tibia | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | ||

| Fibula | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | ||

| Patella | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | ||

| Knee | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | ||

| Ankle | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | ||

| Sacrum | 28 (22) | 27 (21) | ||

| Lung | 29 (24) | 25 (20) | ||

| Pelvic bone | 16 (13) | 17 (13) | ||

| Humerus | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | ||

| Radius | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | ||

| Ulna | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | ||

| Metacarpus | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | ||

| Phalanges | 4 (3) | 3 (2) | ||

| Cervical vertebrae | 3 (2) | 4 (3) | ||

| Thoracic vertebrae | 5 (4) | 7 (6) | ||

| Lumbar vertebrae | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | ||

| Skull | 5 (4) | 11 (9) | ||

| Soft tissues of pelvis | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

| Retroocular soft tissue mass | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

| Retroperitoneum soft tissue mass | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

| Cervical soft tissue | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

| Hyoid bone | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

| Status of GCTB | Primary surgically unsalvageable | 67 (54) | 62 (50) | 0.613 |

| Secondary surgically unsalvageable | 58 (46) | 63 (50) | ||

| Ethnicity | Chinese | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.316 |

| Non-Chinese | 124 (99) | 125 (100) | ||

| bCategory of GCTB | I | 6 (5) | 10 (8) | 0.49 |

| II | 48 (38) | 42 (34) | ||

| III | 71 (57) | 73 (58) | ||

Continuous values are represented as mean ± SD and categorical data as a number (percentage).

GCTB: giant cell tumor of bone.

Chi-square independence tests and repeated measures ANOVA were used to analyze categorical and continuous variables, respectively. p < 0.01 was considered significant.

Pathological, nursing, radiological, and other medical staff (blinded to the groups assignments) with at least 3 years of experience were involved in the evaluation of outcomes.

11-point scale: 0 = death, 10 = no evidence of symptoms or disease.

Based on cytology (the Campanacci system).

3.2. Evaluation parameters at the end of the treatment

Disease status, as per radiological imaging findings, indicated that denosumab and zoledronic acid did not differ in tumor response (p = 0.18) or clinical benefits (p = 0.476) in GCTB patients, although the complete response rate was higher in the DB group than in the ZA group (14 vs. 5, p = 0.002) and disease progression was observed in fewer patients in the DB group (1%) than ZA group (2%, Table 2).

Table 2.

Evaluation parameters at the end of the treatment.

| Parameters | Disease status | Groups |

Comparison between groups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DB | ZA | |||

| Intervention | Denosumab | Zoledronic acid | ||

| Sample size | 125 | 125 | p-value | |

| Clinical benefits | aPain reduction | 38 (30) | 35 (28) | 0.476 |

| Improved mobility | 28 (23) | 22 (18) | ||

| Improved functional activity | 26 (21) | 24 (19) | ||

| Slight or no significant clinical improvement | 33 (26) | 44 (35) | ||

| Disease status | bDisease progression | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0.18 |

| cStable disease | 69 (55) | 73 (58) | ||

| dFractional response | 41 (33) | 45 (36) | ||

| eComplete response | 14 (11)f | 5 (4) | ||

Data are numbers (percentage). Radiological imaging was used for assessing disease status. All radiological imaging parameters were evaluated by the same experienced radiologist.

All physical examination parameters were evaluated by the same experienced physiotherapist.

Chi-square independence tests were used for the statistical analysis. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Evaluation as per RECIST v1.1 guideline.

Visual analogue scale (VAS) score: 0 = no pain, 10 = worst pain imaginable.

New malignancy appeared.

Persistence of targeted lesions.

Decrease of ≥30% in tumor size.

Disappearance of all targeted lesions.

Significant at p = 0.002.

3.3. Treatment-emergent adverse effects

Denosumab and zoledronic acid both induced arthralgia and alopecia. Denosumab caused fatigue (p = 0.0004) and back pain (p < 0.0001). Zoledronic acid caused hypocalcemia (p < 0.0001), flu-like symptoms (p = 0.021), hypotension (p = 0.021), hypokalemia (p = 0.021), and hypophosphatemia which led to hospitalizations. Overall, zoledronic acid was associated with a higher number of serious treatment-emergent adverse events during the follow-up period than did denosumab (Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment-emergent adverse effects during the follow-up period.

| Adverse event | Groups |

Comparison between groups | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DB | ZA | ||

| Intervention | Denosumab | Zoledronic acid | |

| Sample size | 125 | 125 | p-value |

| Arthralgia (joint pain) | 25 (20) | 27 (22) | 0.872 |

| Fatigue | 24 (19)√ | 5 (4) | 0.0004 |

| Headache | 24 (19) | 26 (20) | 0.87 |

| Pain in extremity | 22 (18) | 20 (16) | 0.866 |

| Nausea | 30 (24) | 33 (26) | 0.771 |

| Back pain | 27 (22)√ | 1 (1) | <0.0001 |

| Depression | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0.561 |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | N/A |

| aHypocalcemia | 9 (7) | 45 (36)× | <0.0001 |

| Vomiting | 1 (1) | 5 (4) | 0.215 |

| Constipation | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | N/A |

| Flu-like symptoms | 0 (0) | 7 (6)× | 0.021 |

| Shortness of breath | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0.478 |

| Diarrhea | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | N/A |

| Loss of appetite | 3 (2) | 5 (4) | 0.719 |

| Cough | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.316 |

| Dizziness | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.316 |

| Insomnia | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.316 |

| Abdominal pain | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0.478 |

| Paresthesia | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0.478 |

| Urinary tract infection | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0.478 |

| Alopecia | 5 (4) | 5 (4) | N/A |

| Osteonecrosis of the jaw | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 0.366 |

| bHypophosphatemia | 6 (5) | 13 (10) | 0.152 |

| Weight gain | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.316 |

| cAnemia | 2 (2) | 4 (3) | 0.679 |

| Infections (non-specific) | 5 (4) | 6 (5) | 0.758 |

| Osteomyelitis | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.254 |

| Ostealgia | 0 (0) | 4 (3) | 0.131 |

| Decreased kidney function | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | 0.245 |

| Weight loss | 0 (0) | 5 (4) | 0.071 |

| dHypokalemia | 0 (0) | 7 (6)× | 0.021 |

| Candidiasis | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.316 |

| eHypotension | 0 (0) | 7 (6)× | 0.021 |

| fHypomagnesemia | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.316 |

| Dysphasia | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.316 |

| gFever | 0 (0) | 5 (4) | 0.071 |

All clinical parameters were evaluated by one pathologist, one nephrologist, one hepatologist, one physician, and one hematologist (all with ≥3 years of experience).

N/A: not applicable.

Evaluation as per CTCAEv5.0 guidelines.

Data are represented as numbers (percentage).

Chi-square independence tests were used for the statistical analysis. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Blood serum calcium concentration <2.1 mM/L.

Serum phosphate concentration <2.5 mg/dL (0.81 mM/L).

Hemoglobin level <13.5 g/100 mL for men and <12.0 g/100 mL for women.

Blood serum potassium level <3.5 mM/L.

Blood pressure <90/60 mmHg.

Serum magnesium concentration <1.8 mg/dL (0.70 mM/L).

Body temperature ≥100.4 °F (38 °C) with chills.

Significant denosumab-emergent adverse effects.

Significant zoledronic-acid-emergent adverse effects.

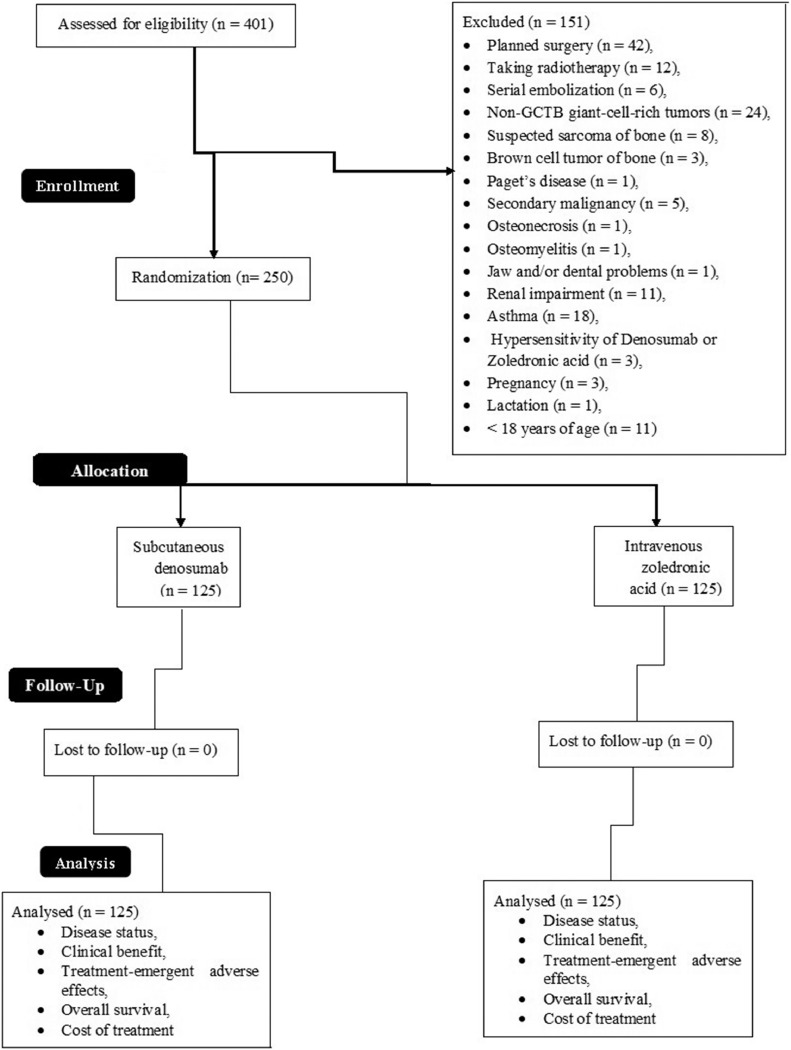

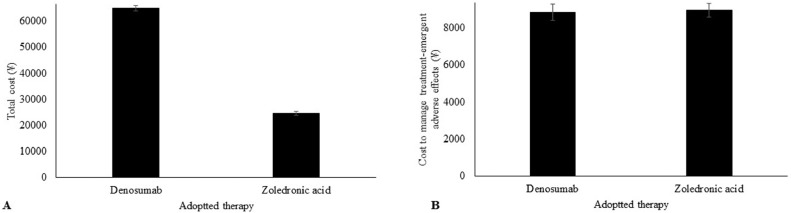

3.4. Cost

Denosumab treatment was markedly more expensive than zoledronic acid treatment (64,947 ± 1145 ¥/patient vs. 24,651 ± 851 ¥/patient, p < 0.0001, Fig. 2A). However, the cost of managing treatment-emergent adverse effects was higher for zoledronic versus denosumab treatment (8945 ± 365 ¥/patient vs. 8845 ± 445 ¥/patient, p = 0.0425, Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Cost analysis of the therapies. (A) Comparison of the total cost between denosumab and zoledronic acid treatment (p < 0.0001). (B) Comparison of cost to manage treatment-emergent adverse effects between denosumab and zoledronic acid (p = 0.0425). p value was derived by one-way repeated measures ANOVA. Costs are in ¥ (7¥ ≈ 1$).

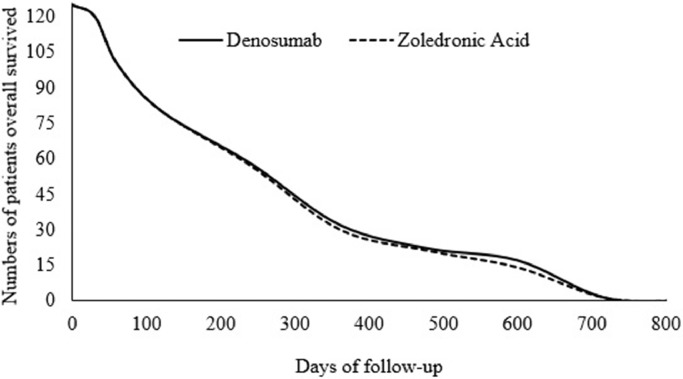

3.5. Survival

Overall survival time after detection of disease was the same for both treatments (754 ± 29 days vs. 745 ± 45 days, p = 0.066, Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the overall survival rate between denosumab and zoledronic acid treatment (p = 0.066 by one-way repeated measures ANOVA). Overall survival was the period of survival after disease detection.

4. Discussion

Tumor progression at the end of the treatment was almost absent in patients with surgically unsalvageable GCTB treated with either denosumab or zoledronic acid (1% for DB group and 2% for ZA group). Denosumab and zoledronic acid both have a bone resorption-inhibiting effect [23]. The results of this study were in line with previous studies [6], [15], [17], [21], [23], [24], [25] but those investigations had some technical issues. For example, the phase II study carried out by Branstetter et al. did not perform statistical analyses or power calculations to show the significance of its results [24], while the case-control study carried out by Tse et al. had small-sized groups (n = 20 and 24) [15]. The phase II study done by Thomas et al. also included a small population (N = 37) and lacked a control group [17]. Therefore, these studies were insufficiently reliable to add significantly to the existing literature. The phase II denosumab study performed by Chawla et al. enrolled patients younger than 18 years [6], even though the safety of denosumab has not been well-established in pediatric patients [13] and the manufacturers do not recommend its use in those aged below 18 years [26]. Therefore, the results of Chawla et al. require further validation. Although the phase III studies carried out by Henry et al. (treatment groups of n = 797 and 800 [21] and n = 890 and 886) [25]) had large sample sizes, no measures were adopted to control for β-errors (false-negative results). Shibuya et al. examined the bone resorption-inhibiting effect of denosumab on giant cell tumor of bone [23], but an in vitro experimental design was used. The present study investigated the use of denosumab and zoledronic acid as antiresorptive agents in patients with surgically unsalvageable GCTB, in an authentic clinical context.

The number of patients in whom all targeted lesions disappeared after six treatment cycles was higher in the DB group than in the ZA group in this study (14 vs. 5, p = 0.002). Denosumab has been shown to reduce tumor size and progression [18], as it binds to RANKL [8], [17], [27], reduces osteoclast-like giant cells, and suppresses osteolysis and proliferative tumor stroma, replacing it with densely woven, differentiated and non-proliferative new bone [6], [24]. Zoledronic acid also has anti-osteoclastic effects, and the ability to protect bone from resorption [7], [15]. The results of the present study indicate that denosumab promotes the deposition of new bone to a greater degree than does zoledronic acid. Additionally, the optimal dosage and duration of zoledronic acid treatment in surgically unsalvageable GCTB remain unclear.

At the end of the treatment, the clinical benefits of both treatments were deemed satisfactory by trained physicians applying systematic assessment criteria. These results were in line with previous studies [6], [7], [15], [24]. However, the group characteristics at baseline differed between groups (e.g., more males in the ZA group, more primary surgically unsalvageable tumors in the DB group). In consideration of these differences, the apparent clinical benefits of both treatments must be interpreted with caution.

Patients treated with zoledronic acid exhibited arthralgia, hypocalcemia, flu-like symptoms, hypophosphatemia, weight loss, hypokalemia, hypotension, and fever. Denosumab induced fatigue, back pain, and arthralgia as treatment-emergent adverse effects. Denosumab treatment has consistently been found to be safe in advanced cancer, in line with the present study [17], [25], [28]. Because of the adverse effects reported here, zoledronic acid treatment was an additional burden for GCTB patients.

During follow-up, the cost to control treatment-emergent toxic effects was higher for patients in the ZA versus DB group, but the total cost of denosumab treatment remained approximately 3-fold higher, as reported elsewhere [10], [11]. Although denosumab showed advantages over zoledronic acid, in socioeconomic terms denosumab is a costly alternative to zoledronic acid for GCTB patients.

Average overall survival time was the same with denosumab and zoledronic acid treatment. These results are in line with previous studies [21], [25]. Patients with solid tumors have shorter lives [21], and as neither denosumab nor zoledronic acid treatment demonstrated superiority in improving overall survival time, the use of one over the other in cases of surgically unsalvageable GCTB requires justification.

The limitations of this study included the relatively short follow-up period to check for local recurrence. As denosumab was given subcutaneously, and zoledronic acid intravenously, patients knew which group they were in and a double-blind design was not feasible. Furthermore, inter- and intra-observer variability were not evaluated, and tumor size reduction in bone was difficult to determine because RECIST criteria apply to soft tissue tumors [6]. Choi response criteria and modified European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) criteria for bone tumors were not applied in this study, because their use would have increased the costs of evaluation.

5. Conclusion

Both the denosumab and zoledronic acid treatments led to marked reductions in giant cell tumor of bone, with relatively manageable adverse effects. As an antiresorptive agent, Denosumab is novel, and more effective and safer—though costlier—than zoledronic acid for treating patients with surgically unsalvageable giant cell tumor of bone. There is a need for further double-blind studies with other antiresorptive agents to improve the overall survival of patients with this type of cancer.

Conflict of interest

Authors have no competing interest regarding results and/or discussion reported in the study.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

Authors are thankful for the medical and non-medical staff of Cancer Hospital of China Medical University, China.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

Authors did not receive financial help from the government, private, or non-profitable sector regarding research.

Authors’ contributions

All authors had read and approved submission for publication. SL contributed to conceptualization and literature review of the study, the draft, and edited the manuscript for intellectual content. PC was project administrator contributed to the conceptualization and literature review of the study. QY contributed to the formal analysis, data curation, and literature review of the study. The authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Footnotes

Level of Evidence: I.

Trial registration: researchregistry4331 dated 1 January 2015 (www.researchregistry.com).

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jbo.2019.100217.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Marinova V.V., Slavchev S.A., Patrikov K.D., Tsenova P.M., Georgiev G.P. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment with denosumab in aggressive giant-cell tumor of bone in the proximal fibula: a case report. Folia Med. 2018;60:637–640. doi: 10.2478/folmed-2018-0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen F., Wang S., Wei Y., Wu J., Huang G., Chen J., Shi J., Xia J. Norcantharidin modulates the miR-30a/Metadherin/AKT signaling axis to suppress proliferation and metastasis of stromal tumor cells in giant cell tumor of bone. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018;103:1092–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.04.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Georgiev G.P., Slavchev S., Dimitrova I.N., Landzhov B. Giant cell tumor of bone: current review of morphological, clinical, radiological, and therapeutic characteristics. J. Clin. Exp. Invest. 2014;5:475–485. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balke M., Hardes J. Denosumab: a breakthrough in treatment of giant-cell tumour of bone? Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:218–219. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balke M. Denosumab treatment of giant cell tumour of bone. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:801–802. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chawla S., Henshaw R., Seeger L., Choy E., Blay J.Y., Ferrari S., Kroep J., Grimer R., Reichardt P., Rutkowski P., Schuetze S., Skubitz K., Staddon A., Thomas D., Qian Y., Jacobs I. Safety and efficacy of denosumab for adults and skeletally mature adolescents with giant cell tumour of bone: interim analysis of an open-label, parallel-group, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:901–918. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70277-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balke M., Campanacci L., Gebert C., Picci P., Gibbons M., Taylor R., Hogendoorn P., Kroep J., Wass J., Athanasou N. Bisphosphonate treatment of aggressive primary, recurrent and metastatic Giant Cell Tumour of Bone. BMC Cancer. 2010;10 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaston C.L., Grimer R.J., Parry M., Stacchiotti S., Dei Tos A.P., Gelderblom H., Ferrari S., Baldi G.G., Jones R.L., Chawla S., Casali P., LeCesne A., Blay J.Y., Dijkstra S.P., Thomas D.M., Rutkowski P. Current status and unanswered questions on the use of Denosumab in giant cell tumor of bone. Clin. Sarcoma Res. 2016;6 doi: 10.1186/s13569-016-0056-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas D.M. The growing problem of benign connective tissue tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:879–880. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie J., Namjoshi M., Wu E.Q., Parikh K., Diener M., Yu A.P., Guo A., Culver K.W. Economic evaluation of denosumab compared with zoledronic acid in hormone-refractory prostate cancer patients with bone metastases. J. Manag. Care Pharm. 2011;17:621–643. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2011.17.8.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koo K., Lam K., Mittmann N., Konski A., Dennis K., Zeng L., Lam H., Chow E. Comparing cost-effectiveness analyses of denosumab versus zoledronic acid for the treatment of bone metastases. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:1785–1791. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1790-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peus D., Newcomb N., Hofer S. Appraisal of the Karnofsky Performance Status and proposal of a simple algorithmic system for its evaluation. BMC Med. Inform Decis. Mak. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amgen Technology (Ireland) Unlimited Company, I. Highlights of prescribing information XGEVA®. https://pi.amgen.com/∼/media/amgen/repositorysites/pi-amgen-com/xgeva/xgeva_pi.pdf. Accessed 1 Jan 2015.

- 14.Beijing Novartis Pharma Co., Ltd., Beijing, China. Highlights of prescribing information for Zometa®. https://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/sites/www.pharma.us.novartis.com/files/zometa.pdf. Accessed 1 Jan 2015.

- 15.Tse L.F., Wong K.C., Kumta S.M., Huang L., Chow T.C., Griffith J.F. Bisphosphonates reduce local recurrence in extremity giant cell tumor of bone: a case-control study. Bone. 2008;42:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Araki K., Ito Y., Takahashi S. Re: Superiority of denosumab to zoledronic acid for prevention of skeletal-related events: a combined analysis of three pivotal, randomised, phase 3 trials. Eur. J. Cancer. 2013;49:2264–2265. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas D., Henshaw R., Skubitz K., Chawla S., Staddon A., Blay J.Y., Roudier M., Smith J., Ye Z., Sohn W., Dansey R., Jun S. Denosumab in patients with giant-cell tumour of bone: an open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:275–280. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engellau J., Seeger L., Grimer R., Henshaw R., Gelderblom H., Choy E., Chawla S., Reichardt P., O'Neal M., Feng A., Jacobs I., Roberts Z.J., Braun A., Bach B.A. Assessment of denosumab treatment effects and imaging response in patients with giant cell tumor of bone. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2018;16 doi: 10.1186/s12957-018-1478-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisenhauer E.A., Therasse P., Bogaerts J., Schwartz L.H., Sargent D., Ford R., Dancey J., Arbuck S., Gwyther S., Mooney M., Rubinstein L., Shankar L., Dodd L., Kaplan R., Lacombe D., Verweij J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur. J. Cancer. 2009;49:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf. Accessed 11 Nov 2018.

- 21.Henry D., Vadhan-Raj S., Hirsh V., von Moos R., Hungria V., Costa L., Woll P.J., Scagliotti G., Smith G., Feng A., Jun S., Dansey R., Yeh H. Delaying skeletal-related events in a randomized phase 3 study of denosumab versus zoledronic acid in patients with advanced cancer: an analysis of data from patients with solid tumors. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:679–687. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashara K.C., Shah K.V. The study of chloramphenicol for ophthalmic formulation. IJSRR. 2018;7:173–181. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shibuya I., Takami M., Miyamoto A., Karakawa A., Dezawa A., Nakamura S., Kamijo R. In vitro study of the effects of Denosumab on giant cell tumor of bone: comparison with zoledronic acid. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s12253-017-0362-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Branstetter D.G., Nelson S.D., Manivel J.C., Blay J.Y., Chawla S., Thomas D.M., Jun S., Jacobs I. Denosumab induces tumor reduction and bone formation in patients with giant-cell tumor of bone. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18:4415–4424. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henry D.H., Costa L., Goldwasser F., Hirsh V., Hungria V., Prausova J., Scagliotti G.V., Sleeboom H., Spencer A., Vadhan-Raj S., von Moos R., Willenbacher W., Woll P.J., Wang J., Jiang Q., Jun S., Dansey R., Yeh H. Randomized, double-blind study of denosumab versus zoledronic acid in the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced cancer (excluding breast and prostate cancer) or multiple myeloma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:1112–1132. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.3304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amgen Europe B.V., the Netherlands. Package leaflet: Information for the user: Prolia® 60 mg solution for injection in pre-filled syringe Denosumab. https://www.prolia.com/about/. Accessed 1 Jan 2015.

- 27.Roux S., Mariette X. RANK and RANKL expression in giant-cell tumour of bone. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:514. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipton A., Fizazi K., Stopeck A.T., Henry D.H., Brown J.E., Yardley D.A., Richardson G.E., Siena S., Maroto P., Clemens M., Bilynskyy B., Charu V., Beuzeboc P., Rader M., Viniegra M., Saad F., Ke C., Braun A., Jun S. Superiority of denosumab to zoledronic acid for prevention of skeletal-related events: a combined analysis of 3 pivotal, randomised, phase 3 trials. Eur. J. Cancer. 2012;48:3082–3092. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.