Abstract

Objectives

Physicians can help patients quit smoking using the 5 As of smoking cessation. This study aimed to (1) identify the proportion of known smokers that receive smoking cessation services in the course of routine clinical practice; (2) describe demographic and comorbidity characteristics of patients receiving the 5 As in these systems; and (3) evaluate differences in performance of the 5 As across health systems, gender, and age categories.

Study Design

Electronic medical records of 200 current smokers from 6 unique health systems (N = 1200) were randomly selected from 2006 to 2010. Primary care encounter progress notes were hand coded for occurrences of the 5 As.

Methods

Bivariate comparisons of delivery of the 3 smoking-cessation services by site, gender, and age category were analyzed using χ2 tests.

Results

About 50% of smokers were advised to quit smoking, 39% were assessed for their readiness to quit, and 54% received some type of assistance to help them quit smoking. Only 2% had a documented plan for follow-up regarding their quitting efforts (arrange). Significant differences were found among sites for documentation of receiving the 5 As and between age groups receiving assistance with quitting. There was no statistically significant difference between genders in receipt of the 5 As.

Conclusions

Documentation of adherence to the 5 As varied by site and some demographics. Adjustments to protocols for addressing cessation and readiness to quit may be warranted. Health systems could apply the methodology described in this paper to assess their own performance, and then use that as a basis to guide improvement initiatives.

Tobacco use remains the leading cause of preventable death in the United States, and yet nearly 46 million people currently smoke cigarettes.1-3 Primary care physicians can greatly facilitate smoking cessation among their patients, and this effort can be a cost-saving clinical preventive service.4-6 Well-accepted, evidence-based guidelines for delivering tobacco-cessation treatments in the primary care setting have been shown to be effective and are recommended as standard care.7-13 Physicians are encouraged to help patients quit by implementing the 5 As of smoking cessation, which include (1) asking all patients about their smoking status; (2) providing personalized advice to quit; (3) assessing smokers’ readiness to quit; (4) assisting motivated patients in their quit attempts, and (5) arranging follow-up contacts for those receiving assistance to quit.

Despite these recommendations and the fact that almost 70% of smokers are interested in quitting,14 the overall proportion of patients who receive counseling remains low15 and there is substantial variation in the use of the 5 As framework across clinical practices and demographic groups.7,14,16,17 Provision of the first 2 As (ask and advise) has been steadily increasing,8,18 but delivery of assess, assist, and arrange has been inconsistent.7,8,10,12,15,19 The rate of cessation help is often lower for Hispanic patients than for non-Hispanic whites; and younger smokers are less likely to receive cessation assistance compared with older smokers.20

Little is known about adherence to the 5 As since the 2008 publication of updated recommendations on treating tobacco use and dependence.7,8,10,12,19 Prior studies assessing provision of the 5 As have generally relied on patient questionnaires, or data collection was limited to specific coded fields within patient medical records.8-10,12,19 Additionally, prior work in assessing the 5 As has been done within a single health system, limiting feasibility of extending findings to other health systems.

This paper extends previous work by leveraging comprehensive medical record data, including coded data fields (eg, diagnosis codes), progress notes, and patient educational materials about smoking, which were handed out to the patient during a visit to assess implementation of the 5 As. A random sample of 200 smokers from each of 6 different health systems across the United States was used. The data reported here were generated by a manual chart review process involving the Comparative Effectiveness Research Hub (CER Hub), a network of asthma and smoking cessation researchers from each of the 6 health systems used for this study (www.cerhub.org).21 Smoking cessation activities based on the 5 As were implemented within the 6 health systems that collectively make up the CER Hub.

The study aims are 3-fold: (1) identify the proportion of known smokers that receive smoking cessation services in the course of routine clinical practice; (2) describe demographic and comorbidity characteristics of smokers receiving smoking cessation services in these systems; (3) evaluate differences in performance of the 5 As across health systems, and also across gender and age categories. Health systems could benefit from an analysis of the 5 As, using patient records to assess their own performance and to guide future smoking cessation initiatives.

METHODS

Setting

Data were collected from 6 health systems, representing unique demographic and geographic populations. The 6 sites constitute a convenience sample of medium-sized healthcare organizations. While this group cannot be seen as a representative sample for the United States, this group does have some geographic diversity, and represents a fairly diverse patient population in terms of race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Each health system also has a distinctive technology infrastructure and electronic medical record (EMR) system. The Institutional Review Board at each health system approved the study protocol. Descriptions of participating health systems are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of Participating Health Systems

| Site | Health System Type | Location | Number of Patients Served | Race/Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baylor Health Care System | Nonprofit, integrated non–health maintenance organization | Texas | 450,000 | 71% white 17% African American 15% Hispanic 6% other race 6% unknown |

| OCHIN, Inc | Nonprofit collaborative network of public and private Federally Qualified Health Centers and other community health centers | Oregon | 335,000 | 74% white 35% Hispanic 4% African American 4% Asian/Pacific Islander 1% Alaska Native/Native American 17% other race |

| VA Puget Sound Health Care System | Federal, integrated healthcare delivery organization | Washington | 70,000 | 80% white 7% African American 3% other race 10% unknown race |

| Kaiser Permanente Hawaii | Nonprofit, group-model health maintenance organization | Hawaii | 223,000 | 40% Asian 30% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander 28% white 2% other race |

| Kaiser Permanente Northwest | Nonprofit, group-model health maintenance organization | Oregon, Washington | 460,000 | 87% white 6% Hispanic 5% Asian American 3% African American 1% Native American 4% other race |

| Kaiser Permanente Southeast | Nonprofit, group-model health maintenance organization | Georgia | 260,000 | 40% white 40% African American 5% other race |

Participant Sample

The medical records of 200 current smokers in each of the 6 selected health systems were randomly selected for this study (N = 1200). Inclusion criteria included patients 12 years and older who were identified as (1) a current smoker at any point during the years 2006 to 2010, regardless of “quitting” events and (2) having at least 1 primary care visit in each of the 5 study years. We classified patients as “current smokers” if (1) they received any of the following International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes related to tobacco-use disorders: 305.1, 649.01, 649.02, 649.03, 649.04, or 989.84, at any primary care visit or (2) had an update to their social history indicating “current smoker” during the study period. Smoking-related comorbidities during the observation period were also documented for each participant, and ethnicity and race information was extracted from each patient’s medical record.

Coding of the 5 As

A single primary-care encounter from each of the 1200 medical records, as described above, was hand coded for documentation of the 5 As. An “encounter” included all data linked to the encounter (eg, vital signs, reasons for visit, medications and procedures ordered, diagnoses) as well as progress notes and patient education materials printed out for the patient. Encounter records were formatted as XML computer language files according to a schema conforming to Health Level Seven International’s (HL7’s) Clinical Document Architecture (CDA) standard.22,23 These records were de-identified and uploaded onto a secure Web server, where they were accessed by project staff using a Web-based application called Manual Coder that is part of the CER Hub. Users of Manual Coder sequence through encounter records in a data set and have the ability to highlight text elements representative of the study measures (in this instance, components of the 5 As) and then select the code appropriate to the highlighted text from a list. The applied codes, as well as the highlighted content from the encounter record, can be extracted from the database for analysis of either site-specific or aggregate data.

Coding staff from each site were trained on using Manual Coder for coding the 5 As by webinar conferencing during a 3-week period. Following this training, staff were provided written instructions along with a pilot set of 10 encounter records to code using Manual Coder. Results were tabulated and reviewed in a subsequent webinar session during which discrepancies and errors in coding were discussed. Once consensus was established on the pilot records, 1 to 2 project staff at each site coded the data set from their respective health system (N = 200 records each). During the course of the coding process, questions about specific data elements were communicated to the lead investigator. Responses from the investigator were used to update the written instructions, and communicated in real time by e-mail and in a weekly meeting for project staff. The coding process at all project sites was completed in 1 month. The completed codings were reviewed by the lead trainer, who checked for and adjudicated discrepancies with the coding instructions. Mapping of the 5 As coding definitions from the medical record encounter, as documented by a healthcare provider, is displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

5 As Coding Definitions

| Description in Progress Notes | |

|---|---|

| Ask | Includes any aspect of the encounter which addresses smoking. This includes diagnosis codes applied to the visit, smoking status update to the patient’s social history, or mentions of tobacco use or prevention in the text notes. |

| Advise | Includes generic statements advising the patient to quit. This is typically indicated by imperative, directive statements by clinician. |

| Assess | Includes statements reflecting a patient’s readiness to quit, usually indicated by phrases that invoke the patient’s current intent, motivation, or effort at quitting. |

| Assist | Includes statements addressing commitment to a method to achieve quitting with reference to ordering, planning, or provision of information relating to smoking cessation medications or nicotine replacement therapies; by a notation ordering, planning, or provision of information related to outside cessation help; indication of aspects of counseling to quit smoking including in-office discussion of barriers, triggers, strategies, etc, related to quitting. |

| Arrange | Includes statements documenting specific plans for follow-up with a patient’s effort to quit. |

Comorbidities were assessed using groups of ICD-9-CM codes recorded at primary care encounters during the observation period. The categories of codes used for this analysis included cancer (all types except skin cancer), cardiovascular disease (CVD), asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, hypertension, and stroke.

Analysis

Available data allowed for bivariate (contingency table) comparisons of delivery of smoking cessation services by site, gender, and age category (12-24, 25-49, and 50+ years) using χ2 tests. All P values are 2-sided with significance defined at the .05 level.

RESULTS

Demographic and Comorbidity Characteristics of Smokers

Demographics of participants are displayed in Table 3. Fifty-six percent (56%) of smokers in the combined sample were male and 53% were 50 years and older. Sixty-three percent (63%) of the sample had a recorded race, with white representing the largest racial group (40%). The comorbidities with the highest reported rates were hypertension (21%) and diabetes (8%).

Table 3.

Study Population Demographics

| Site A N = 200 |

Site B N = 200 |

Site C N = 200 |

Site D N = 200 |

Site E N = 200 |

Site F N = 200 |

Total N = 1200 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 52% | 33% | 52% | 93% | 53% | 55% | 56% |

| Female | 49% | 68% | 49% | 8% | 47% | 46% | 44% |

| Age | |||||||

| 12-24 y | 9% | 0% | 3% | 2% | 10% | 12% | 6% |

| 25-49 y | 49% | 18% | 44% | 26% | 60% | 54% | 42% |

| 50+ y | 43% | 83% | 54% | 72% | 31% | 34% | 53% |

| Racea | |||||||

| White | 2% | 82% | 15% | 73% | 45% | 25% | 40% |

| African American | 2% | 9% | 2% | 12% | 4% | 20% | 8% |

| Asian | 1% | 4% | 27% | 2% | 1% | 1% | 6% |

| American Indian | 29% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 1% | 0% | 5% |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0% | 0% | 23% | 2% | 0% | 0% | 4% |

| Unknown/otherb | 67% | 5% | 34% | 13% | 50% | 55% | 37% |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic | 3% | 3% | 7% | 1% | 7% | 1% | 4% |

| Non-Hispanic | 32% | 68% | 94% | 84% | 63% | 0% | 56% |

| Unknown | 65% | 30% | 0% | 15% | 30% | 99% | 40% |

| Comorbidity | |||||||

| Cancer | 0% | 1% | 1% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 3% |

| CVD | 0% | 0% | 5% | 2% | 0% | 0% | 1% |

| Asthma | 5% | 7% | 9% | 2% | 3% | 8% | 5% |

| COPD | 6% | 1% | 2% | 14% | 0% | 1% | 4% |

| Diabetes | 9% | 6% | 14% | 11% | 1% | 9% | 8% |

| Hypertension | 13% | 9% | 28% | 38% | 7% | 33% | 21% |

| Stroke | 0% | 1% | 0% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 1% |

CVD indicates cardiovascular disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

may include more than 1 race.

unknown race includes cases where race is not reported or another category of race is listed.

The gender distribution among the 6 health systems was approximately even except for site B, where 68% of smokers were female, and site D, where 93% of smokers were male. Smokers aged 12 to 24 years were the least represented across all sites (only 6% of the sample). Sites B, C, and D had a larger proportion of smokers belonging to the 50 years and older group. Patient race varied considerably between the 6 health systems, representing the local populations at each site.

Proportion of Smokers Receiving the 5 As

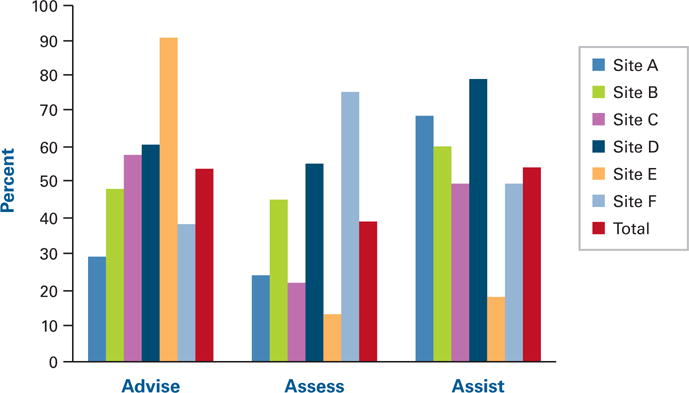

Given that this sample was selected based on smoking status, 100% of smokers within the sample were asked about their smoking status (ask). Just over half were advised to quit smoking by their physician. Approximately 40% of smokers were assessed for their readiness to quit smoking, and 54% of patients received assistance to help them quit smoking in the form of counseling, medication, or referral to smoking cessation programs. Only 2% had a documented plan for follow-up regarding their quitting efforts (arrange). Because of this low rate, we did not include arrange in additional analyses. Figure 1 displays the frequency of the implementation of advise, assess, and assist by site.

Figure 1. Documentation of Advise, Assess, and Assist by Sitea.

aSignificant differences found between sites for each A at P <.001.

The proportion of smokers receiving advice to quit smoking, assessment of readiness to quit smoking, and assistance with quitting varied significantly across the 6 health systems (P <.001; see Figure 1), ranging from 29% to 91% for advice, 13% to 76% for assess, and 18% to 79% for assist.

Site Differences in Rates of the 5 As by Gender, Age, Race, and Comorbidities

In the combined sample, delivery of advise, assess, and assist did not vary significantly between males and females (55% vs 54%, 39% vs 39%, and 54% vs 55%, respectively). The proportion of females that received advice ranged from 33% at sites A and F to 96% at site E, while the proportion of males ranged from 25% at site A to 76% at site E. All sites except for site B provided assess to a higher proportion of female smokers (ranging from 23%-78%). Assist was provided to a higher proportion of females for all sites except for site E (ranging from 17%-100%).

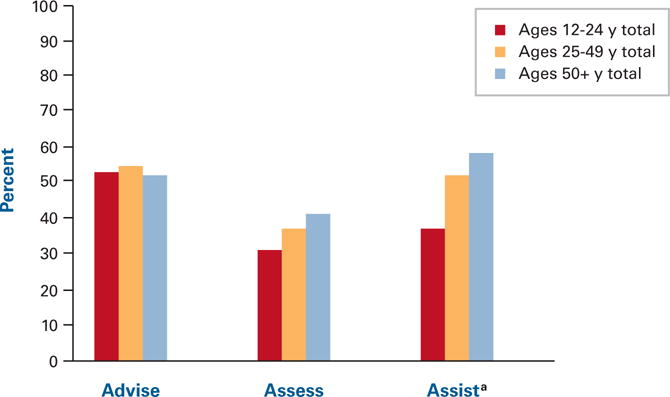

The delivery of advise and assess did not vary significantly across age groups. However, delivery of assist did vary quite a bit across age groups: 37% in the group aged 12 to 24 years, 52% in the group aged 25 to 49 years, and 58% in the 50 years and older group (P = .001, Figure 2). The proportion of smokers aged 25 to 49 years that received advice ranged from 27% at site A to 79% at site E. Assess was provided the least to smokers in all age groups at site E (under 20%) and the most to smokers at site F (over 65%). Smokers aged 25 to 49 years received assist ranging from 13% at site E to 77% at site D, and smokers 50 years and older ranged 31% at site E to 81% at site D.

Figure 2. Documentation of Advise, Assess, and Assist by Age.

aSignificant differences between age groups for receiving assist at P <.001.

Except for site C, whites received the most help with quitting smoking. Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander and American Indian populations typically received less help with quitting smoking.

The proportion of smokers with a smoking-related comorbidity that received advise ranged from 33% with stroke to 67% that had a reported CVD. Smokers with COPD (sites A, B, E, and F) and asthma (sites C and D) were most likely to be advised to quit smoking. A higher proportion of smokers with COPD and asthma received assess, except for sites A (CVD) and F (stroke).

DISCUSSION

This analysis examined the provision of the 5 As of smoking cessation in a population of known smokers from 6 diverse health systems, using data in patient medical records. A unique feature of this study is its use of details in the medical record (eg, history of present illness, or assessment and plan portions of the encounter note) to identify differences in smokers who received the 5 As, based on demographic and health-system characteristics, in contrast to a majority of past studies that used coded data only. Additionally, this study extended prior research to include 6 different healthcare delivery systems, thereby adding to the literature by increasing the scope of identifying the 5 As and the generalizability of results.

In accord with other studies, our results indicated that advise occurred most frequently, and that assist and arrange occurred less often.7,15,18,24 Our design of including only those with at least an ask, based on a coded ICD-9-CM visit diagnosis or tobacco history, allows for the interpretation that these data on smoking-related counseling represent an upper bound on rates of smokers that received assistance in quitting. It may be that most smokers were asked about their smoking status, but no action was taken by their physician to provide next steps in assessing readiness or offering assistance. Additionally, assist is a useful indicator only when a smoker has an interest in quitting. Therefore, the rates of documenting assist may be dependent on whether the smoker expresses a readiness to quit and may not be a true estimation of provider assistance. Other barriers to implementing the 5 As include provider time constraints, limited administrative support, case management issues, provider and patient situational differences, and a lack of resources to support cessation efforts.25

The low frequency of arrange seen in this study is consistent with previous studies.7,10,12 It is possible that follow-up for smoking cessation was done at subsequent visits, without a notation being made in the medical record. Nonetheless, the results highlight a need for additional follow-up support for smokers, possibly through a systems-based strategy, such as adding smoking as a prompted vital sign within the EMR.26

Documentation of the evaluated 3 As (advise, assist, assess) varied between health systems.7,14,16,17 Some sites performed advise more often, while others performed assist at higher rates. These findings indicate that there may be variables that come into play when analyzing the usage of the 5 As by health systems, such as differing policies for addressing smoking, physician training in the 5 As, or a physician’s lack of understanding of the patient’s health plan coverage for tobacco treatment services.27 Variability may also be explained by the fact that health systems have incentives to provide the 5 As to patients who smoke, such as accounting for performance quality measures and managing costs associated with smoking.11,18,28 The differing rates of documentation of advise, assist, and assess point to the need for an integrated approach by physicians and support staff to help patients quit smoking through the use of effective strategies and interventions.12

Unlike past studies, we did not find a gender difference for receiving the 5 As with combined data from all health systems.10,12,29,30 However, smokers used in this sample, and the visits from which data are drawn, represent a high likelihood of receiving and documenting the delivery of the 5 As. For example, at site D, 93% of patients who received the 5 As were male.

It has been suggested that older smokers may receive help with smoking cessation more often than younger smokers.12 Our data support these findings. For example, when all health systems were combined, we did not find a difference between age groups for receiving advise or assess. However, only 37% of smokers aged 12 to 24 years received assist, while 52% of smokers aged 25 to 49 years, and 58% of smokers 50 years and older, received cessation assistance. Patients and providers may have different knowledge, attitudes, or beliefs about who should be receiving help.31 Additionally, older smokers often have more interest in quitting, while younger smokers may encounter increased social pressures to smoke and be less motivated to quit.14,32 Nonetheless, the gap in services offered to patients of different ages indicate that specific health systems may need to tailor protocols for addressing readiness to quit according to age group.

Racial and ethnic disparities in smoking cessation counseling have also been observed previously, and health systems should be aware of their diverse populations so that they may offer efficacious, culturally tailored smoking interventions.3,31,33 The disparities observed in this study raise some questions, like whether disparities are due to differences in opportunities to receive healthcare, or due to biases within a health system or among providers. Future research to answer these questions will help to inform system policies and measures.

Results from this study indicate that not all smokers with a smoking-related comorbidity are receiving cessation help at every visit, and this variation differs among health systems. Past research into this area is scarce, but we hypothesize that ICD-9-CM coding practices for certain health conditions within the EMR at different sites may account for some of these discrepancies. Future research might examine how comorbid conditions affect both completeness of data captured and intensity of a patient’s exposure to the health systems, resulting in differing opportunities to receive the 5 As. Management of chronic conditions might lead to more frequent contact with staff that have different standards for capturing and coding encounters (such as pharmacists or medical assistants).

Study Limitations

Generalizability of these findings may be limited by the selection of the participating health systems. All of the participating sites have adopted strong tobacco treatment guidelines and provide multiple types of smoking cessation treatment for their patients. Second, visits included in the analysis were selected specifically because they indicated a current smoking status (ask), increasing the likelihood of evidence of the other 5 As. Third, our analyses have been limited to information in the patient’s medical records, which may not comprise a complete summary of a visit, and record content may be influenced by possible incentives for treating tobacco use at a particular site, or they may contain additional sources of error. However, documentation of patient treatment is considered standard care, and we believe the free text medical notes are representative of a patient visit. Fourth, ICD-9-CM codes were used to identify smoking status and diagnosis, and are not necessarily an indication of treatment or representative of smokers as a whole. We assumed in this study that smoking status was detected based on the healthcare provider behavior rather than volunteered information from the patient. Fifth, we used a single patient visit as documentation of smoking intervention. There is a possibility of variability among patients with regard to changes in smoking status or interventions for smoking. Lastly, we recognize that physicians are aware of the 5 As and the need to address smoking with their patients, but also that physicians may not input all cessation-related information in the patient’s health record. Because this study is limited to what information is in the EMR, and represents an upper bound on rates of smokers, our data may represent a modest underreporting of smoking cessation interventions by physicians.

CONCLUSION

Findings add to the literature by assessing the 5 As at a health-systems level. Coded and free-text data indicate that the documentation of the implementation of the 5 As guideline for tobacco cessation varied considerably across health systems. We found that adherence to advise, assess, and assist varied according to site, patient age, and comorbidity. Adjustments to protocols for addressing smoking cessation and readiness to quit may be warranted. Our findings are generalizable to various health systems. Health systems could apply the methodology described in this paper to assess their own performance and guide improvement initiatives.

Take-Away Points.

Health systems could benefit from an analysis of the 5 As, using patient records to assess their own performance and to guide future smoking cessation initiatives.

-

■

Results could help with the training of healthcare providers to apply the 5 As of smoking cessation framework to all patients.

-

■

Smoking cessation initiatives and policies for a healthcare organization could be generated around findings.

-

■

Health systems could benefit from an analysis of patient demographics and use those to help with smoking cessation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Christine Nelson, Elisa Priest, and Ashley Collinsworth for their helpful contributions.

Source of Funding: The CER Hub project (www.cerhub.org) is funded by grant R01HS019828 (Hazlehurst, PI) from the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Authorship Information: Concept and design (RJW, ALM, LIS, SRB, AEW, VJS); acquisition of data (ALM, JEP); analysis and interpretation of data (RJW, ALM, MAM, LIS, JEP, VJS); drafting of the manuscript (RJW, ALM, MAM, SRB, VJS); critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (RJW, ALM, LIS, SRB, AEW, JEP, VJS); statistical analysis (MAM); provision of study materials or patients (RJW, ALM); administrative, technical, or logistic support (RJW, VJS).

Author Disclosures: The authors report no relationship or financial interest with any entity that would pose a conflict of interest with the subject matter of this article.

Contributor Information

Rebecca J. Williams, University of Hawaii, Manoa.

Andrew L. Masica, Baylor Health Care System, Institute for Health Care Research and Improvement, Dallas, TX.

Mary Ann McBurnie, Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research Northwest, Portland, OR.

Leif I. Solberg, HealthPartners Research Foundation, Minneapolis, MN.

Steffani R. Bailey, Oregon Health and Science University, Department of Family Medicine, Portland, OR.

Brian Hazlehurst, Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research Northwest, Portland, OR.

Stephen E. Kurtz, Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research Northwest, Portland, OR.

Andrew E. Williams, Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research Northwest, Portland, OR.

Jon E. Puro, Our Community Health Information Network, Portland, OR.

Victor J. Stevens, Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research Northwest, Portland, OR.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults and trends in smoking cessation – United States, 2008. MMWR. 2009;58(44):1227–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults – United States, 2007. MMWR. 2008;57(45):1221–1226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogt TM, Lichtenstein E, Ary D, et al. Integrating tobacco intervention into a health maintenance organization: the TRACC program. Health Educ Res. 1989;4(1):125–135. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maciosek MV, Coffield AB, Edwards NM, et al. Priorities among effective clinical preventive services: results of a systematic review and analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(1):52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solberg LI, Maciosek MV, Edwards NM, Khanchandani HS, Goodman MJ. Repeated tobacco-use screening and intervention in clinical practice: health impact and cost effectiveness. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(1):62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update: Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollis JF, Bills R, Whitlock E, Stevens VJ, Mullooly J, Lichtenstein E. Implementing tobacco interventions in the real world of managed care. Tob Control. 2000;9(suppl 1):I18–I24. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.suppl_1.i18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lancaster T, Stead L, Silagy C, Sowden A. Effectiveness of interventions to help people stop smoking: findings from the Cochrane Library. BMJ. 2000;321(7257):355–358. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7257.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quinn VP, Steven VJ, Hollis JF, et al. Tobacco-cessation services and patient satisfaction in nine nonprofit HMOs. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(2):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz DA, Muehlenbruch DR, Brown RL, Fiore MC, Baker TB. AHRQ Smoking Cessation Guideline Study Group Effectiveness of implementing the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality smoking cessation clinical practice guideline: a randomized, controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(8):594–603. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quinn VP, Hollis JF, Smith KS, et al. Effectiveness of the 5-As tobacco cessation treatments in nine HMOs. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(2):149–154. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0865-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stead LF, Bergson G, Lancaster T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quitting smoking among adults–United States, 2001-2010. MMWR. 2011;60(44):1513–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thorndike AN, Rigotti NA, Stafford RS, Singer DE. National patterns in the treatment of smokers by physicians. JAMA. 1998;279(8):604–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.8.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simmons VN, Litvin EB, Unrod M, Brandon TH. Oncology healthcare providers’ implementation of the 5 A’s model of brief intervention for smoking cessation: patients’ perceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;86(3):414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Committee for Quality Assurance. The State of Health Care Quality 2007. Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens VJ, Solberg LI, Quinn VP, et al. Relationship between tobacco control policies and the delivery of smoking cessation services in nonprofit HMOs. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;35:75–80. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jamal A, Dube SR, Malarcher AM, Shaw L, Engstrom MC. Tobacco use screening and counseling during physician office visits among adults – National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2005-2009. MMWR. 2012;61(suppl):38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hazlehurst B, Frost HR, Sittig DF, Stevens VJ. MediClass: a system for detecting and classifying encounter-based clinical events in any electronic medical record. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12(5):517–529. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dolin RH, Alschuler L, Beebe C, et al. The HL7 Clinical Document Architecture. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2001;8(6):552–569. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2001.0080552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dolin RH, Alschuler L, Boyer S, et al. HL7 Clinical Document Architecture, Release 2. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13(1):30–39. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glasgow RE, Emont S, Miller DC. Assessing delivery of the five ‘As’ for patient-centered counseling. Health Promot Int. 2006;21(3):245–255. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dal017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manfredi C, LeHew CW. Why implementation processes vary across the 5 A’s of the Smoking Cessation Guideline: administrators’ perspectives. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(11):1597–1607. doi: 10.1080/14622200802410006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCullough A, Fisher M, Goldstein AO, Kramer KD, Ripley-Moffitt C. Smoking as a vital sign: prompts to ask and assess increase cessation counseling. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(6):625–632. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.06.080211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Solberg LI, Quinn VP, Stevens VJ, et al. Tobacco control efforts in managed care: what do the doctors think? Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(3):193–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Department of Health and Human Services. Sustaining State Programs for Tobacco Control: Data Highlights 2006. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farmer MM, Rose DE, Riopelle D, Lanto AB, Yano EM. Gender differences in smoking and smoking cessation treatment: an examination of the organizational features related to care. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21(4 suppl):S182–S189. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Croghan IT, Ebbert JO, Hurt RD, et al. Gender differences among smokers receiving interventions for tobacco dependence in a medical setting. Addict Behav. 2009;34(1):61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu S, Melcer T, Sun J, Rosbrook B, Pierce JP. Smoking cessation with and without assistance: a population-based analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(4):305–311. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hughes J, Marcy TW, Naud S. Interest in treatments to stop smoking. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36(1):18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Institutes of Health State of the Science Panel. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science conference statement: tobacco use: prevention, cessation, and control. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(11):839–844. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-11-200612050-00141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]