Abstract

Changes in locomotor activity of beef females during the 72 h prepartum were determined in 3 experiments: (i) a 2-yr study with spring-calving multiparous cows (Exp. 1; n = 34 and 27 for years 1 and 2, respectively); (ii) spring-calving primiparous (first pregnancy; n = 13) and multiparous (n = 21) dams (Exp. 2); and (iii) fall-calving multiparous cows (Exp. 3; n = 33). For all experiments, IceQube activity monitors (iceRobotics, Edinburgh, UK) were placed above the left hind fetlock of pregnant females ≥3 d prepartum. During the calving season, females were housed in 18 × 61 m drylots with ad libitum access to hay or haylage. Parturition was closely monitored, and time of birth was noted. Motion index, standing and lying time, step count, and the number of lying bouts for each dam (summed per hour) were determined for the 72 h preceding calving. Within experiment, data were analyzed by day (days −3 to −1 prepartum), by 6-h period during the final 24 h prepartum, and by hour during the final 6 h prepartum using a mixed model with time as a repeated effect. Year was also included as a fixed effect in Exp. 1. Fixed effects of parity and time prepartum × parity were included for Exp. 2. In all 3 experiments, motion index, standing time, step count, and the number of lying bouts were greater (P < 0.001) on day −1 compared with days −2 and −3 prepartum. In the 24 h prepartum, dams had greater (P < 0.01) motion index, standing time, step count, and the number of lying bouts during 6 h preceding parturition compared with −11 to −6 h in all experiments. Motion index, step count, and lying bouts changed (P ≤ 0.02) during the last 6 h in all experiments. Primiparous dams had more (P ≤ 0.01) lying bouts than multiparous dams during the last day and −11 to −6 prepartum. In all experiments, the number of lying bouts more than doubled (P < 0.001) from −2 to −1 prepartum, with no effect of year (P = 0.57) in Exp. 1 or parity (P ≥ 0.29) in Exp. 2. This suggests that lying bout changes may be the most reliable of parameters measured in detection of calving. Moreover, fall-calving cow behavioral patterns were similar to changes observed in spring-calving females, suggesting that calving season may have minimal effects on pre-calving behavior. Overall, electronic locomotor activity monitors can detect behavioral changes peripartum in beef heifers and cows. More research is necessary to determine if these can be used to remotely sense early signs of parturition in beef cattle.

Keywords: beef cattle, behavior, calving, parity, parturition, technology

INTRODUCTION

In 2010, 20.9% of reported nonpredator beef calf preweaning death loss was due to calving problems (USDA-APHIS, 2010). Individual monitoring of dams is required to identify calving difficulties as early as possible, allowing for human intervention to minimize the negative impacts of dystocia and prolonged calving on calf survival (Dargatz et al., 2004; Wehrend et al., 2006). Remote detection of calving in a herd setting through prediction technology could reduce calf mortality caused by dystocia or other calving-related health problems such as hypothermia (Saint-Dizier and Chastant-Maillard, 2015). Beef producers would benefit from this technology if it was economical, required minimal additional animal handling, was useful in large herd settings, and allowed for a diverse array of animal housing dependent upon operation type.

Behavioral monitoring using accelerometers and pedometers has been used in the dairy industry for health and estrus detection, allowing for behavioral observation of multiple cows without the need to physically observe each animal individually (Fogsgaard et al., 2015; Tsai, 2017; Finney et al., 2018). These devices can be left on for long periods of time, making timing of application and removal flexible, as well as decreasing the amount of handling required near calving. Commercially available accelerometer devices such as IceTag and IceQube products (iceRobotics, Ltd., Edinburgh, UK) have been well validated against visual behavioral monitoring in dairy cattle (Nielsen et al., 2010), where use of this technology for early recognition of parturition is being explored (Huzzey et al., 2005; Miedema et al., 2011b; Borchers et al., 2017). Use of accelerometers in beef cattle has been limited to research in the early detection of feedlot morbidity (Pillen et al., 2016; Richeson et al., 2018), but dairy data suggest that these may have utility in detection of calving in beef females as well.

Monitoring of calving in beef cattle is often concentrated in heifers due to increased dystocia associated with first parity females (Berger et al., 1992; Zaborski et al., 2009). Behavioral activity is likely influenced by many factors including housing, season, and environment (Brzozowska et al., 2014). Locomotor behavior of dairy dams peripartum has been reported to differ by parity (Miedema et al., 2011a; Titler et al., 2015). Because of this, behavioral differences associated with parity may also impact the use of electronic activity monitoring, but to our knowledge, peripartum locomotor activity and factors affecting it have not been studied in beef cattle.

We hypothesized that both multiparous and primiparous beef dams would have increased locomotor activity prior to calving, with primiparous dams being more active near parturition than multiparous dams. Our specific objectives were to determine peripartum changes in locomotion behavior in spring- and fall-calving cows, as well as differences between behavior of primiparous and multiparous dams in the final 3 d, 24 h, and 6 h prepartum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The University of Missouri Animal Care and Use Committee approved animal care and use in this study (Protocols 7936, 8952, and 9045).

Gestating Animal Management

All experiments.

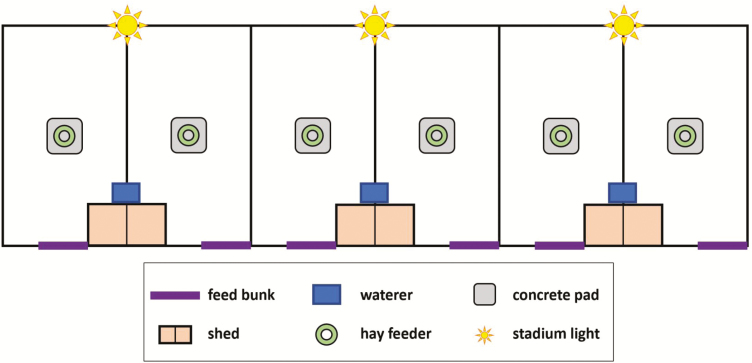

In 3 experiments, cows or heifers were housed in well-drained 18 × 61 m drylots with limestone-based surface (Figure 1, for all experiments) at the University of Missouri Beef Research and Teaching Farm and observed during the peripartum period. More females were observed in each experiment than were used in final data analysis to provide adequate numbers. Cows were fed ad libitum hay or haylage in round bale feeders located near the center of the pens on 9.1 × 9.1 m concrete pads to prevent mud accumulation around the feeders. Automatic waterers and feed bunks (9.8 m bunk length per pen) were located at the front of pens. Sheds were kept closed to animals unless individuals were moved under cover due to inclement weather during spring-calving (Exp. 1 and 2). For Exp. 1 and 2, ~20% of the pen area at the opposite end from the waterers and feed bunks were bedded with fescue straw to help mitigate calf cold stress. No bedding was used in Exp. 3, as it occurred during the fall season.

Figure 1.

Calving pen layout (18 × 61 m) for Exps 1, 2, and 3; hay feeders were on 9.1 × 9.1 m concrete pads; feed bunks were 9.8 m/pen.

Experiment 1.

A 2-yr study was conducted in which multiparous, spring-calving, and Sim-Angus crossbred beef cows (year 1 n = 48, year 2 n = 56) were monitored during late gestation. The calving season was 79 d (beginning January 31, 2015) in year 1 and 44 d (beginning on February 2, 2016) in year 2. As part of a forage system study (Niederecker et al., 2018), cows were allocated to either strip-graze endophyte-infected stockpiled tall fescue or receive endophyte-infected tall fescue hay in drylots during late gestation. Drylots used for the hay forage system were the same as those used in calving (Figure 1). Cows were kept within the same forage system treatment groups, but those grazing stockpiled tall fescue were moved to additional drylots adjacent to cows receiving hay for observation 10.2 ± 8.6 (SD throughout) d (year 1) and 9.2 ± 4.3 d (year 2) pre-calving and fed harvested haylage. Dams were penned in groups of 8 to 10 animals based on previous treatments.

Experiment 2.

Primiparous (n = 23; dams pregnant with first calf) and multiparous (n = 65) spring-calving Sim-Angus crossbred beef females were moved to 6 drylots for observation 6.7 ± 3.0 d prior to calving. The period of calving monitoring was 15 d beginning on January 28, 2017. Dams were penned in groups of 12 to 15 animals by prior management group (parities 1 and 2 vs. parity ≥3). Animals were allowed ad libitum access to endophyte-infected tall fescue hay and supplemented with dried distillers grains with solubles at approximately 1700 hours daily.

Experiment 3.

Fall-calving Sim-Angus crossbred beef females (n = 45) were moved to 6 drylots for observation 17.5 ± 1.2 d prior to calving following individual feeding in smaller pens (4 cows per pen) for research using a Calan gate system. Dams were then assigned to calving pens in groups of 10 to 12 animals. The calving season was 36 d beginning on September 7, 2017. Animals were allowed ad libitum access to endophyte-infected tall fescue hay and supplemented with a soyhulls and dried distillers grains with solubles-based supplement at approximately 1700 hours daily.

Calving Management and Data Collection

One IceQube activity monitor (iceRobotics, Edinburgh, UK) was placed above the left hind fetlock of each pregnant female per manufacturer instructions. IceQube activity monitors were placed on dams 44.3 ± 21.7 d (year 1) and 41.0 ± 1.7 d (year 2) prior to calving in Exp. 1, 6.7 ± 0.3 d prior to calving in Exp. 2, and 34.4 ± 0.9 d prior to calving in Exp. 3. These accelerometers allow for tri-axial movement detection, continuous data logging, and data summary into specific increments of time (Richeson et al., 2018). These locomotion devices have been validated for accuracy against video monitoring in late gestation dairy cows by other groups (Mattachini et al., 2013; Borchers et al., 2016).

Calving pens were well-lit, and lights were kept on during all or most of the night (depending on night calving density and experiment) to allow for observation of calving. Personnel monitored cows and heifers for physical signs of labor by walking through pens at least once per hour from 0600 to 2400 hours in each study, with additional monitoring between 0000 and 0600 hours during heavy calving periods. Females were monitored continuously by on-site personnel from the time of visible evidence of stage II parturition (presence of amniotic membranes or calf feet), and actual time of birth was recorded for each calf (expulsion of entire calf, including all 4 legs). Minimal human interference occurred during parturition except to assess progress or assist as needed if there were concerns of dystocia. No animals with dystocia requiring assistance were included in the dataset.

Data were excluded from cows that calved prior to IceQube placement, with unknown calving times, that calved outside of the observation period, or with IceQube malfunction, resulting in the numbers and animals described in Table 1. Data from an individual day were removed for females moved outside of their normal patterns during the final 72 h prepartum. Movement outside normal patterns constituted cows that left pens due to movement to a working facility for other data collection, rearranging animals among pens, or relocation to a covered area if calving during inclement weather (Exp. 1 or 2). Descriptive data are provided for animals included in analysis for Exp. 1, 2, and 3 in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of beef females included in analysis for locomotor activity during the 72 h prior to calving in 3 experiments1

| Exp. 1 | Exp. 2 | Exp. 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Year 1 | Year 2 | Primiparous | Multiparous | |

| n | 34 | 27 | 13 | 21 | 33 |

| Parity | 4.5 ± 2.5 | 4.8 ± 2.3 | 1 ± 0 | 4.7 ± 3.1 | 3.4 ± 1.2 |

| Prepartum body weight, kg | 682 ± 74 | 671 ± 75 | 552 ± 44 | 670 ± 63 | 708 ± 89 |

| Prepartum body condition score2 | 5.3 ± 0.5 | 5.3 ± 0.5 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 5.5 ± 0.7 |

| Gestation length3, d | 284 ± 2.7 | 279 ± 2.7 | 277 ± 2.0 | 276 ± 2.5 | 284 ± 3.1 |

| Average calving date | February 21, 2015 | February 16, 2016 | February 5, 2017 | February 5, 2017 | September 19, 2017 |

1Least square means ± SD are presented for each variable.

2BCS evaluated on 1 to 9 scale (1 = emaciated, 9 = obese).

3Calculated only for cows that conceived from artificial insemination.

IceQube activity monitors were removed ≥2 d postpartum. IceManager 2012 software (iceRobotics, Edinburgh, UK) was used to obtain and sum each cow and heifer’s motion index, standing time, lying time, step count, and number of lying bouts per hour, then exported to an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA). Step count indicates the number of steps taken by the leg on which the IceQube is attached. Standing and lying time within an hour sum up to 60 min and therefore have an inverse relationship. Lying bouts are any periods in which an animal laid down and stood back up, and vary in duration length. Motion index was provided by the IceManager software using a proprietary algorithm. Hour 0 was defined as the hour increment nearest to parturition in which the majority of time represented prepartum behavior. For example, if a cow calved at 1250 hours, 1200 to 1300 hours was set as 0 h; whereas if a cow calved at 1210 hours, 1100 to 1200 hours was set as 0 h. This was done to prevent postpartum behavior from being most of the time occurring during 0 h (calving), which would likely influence results. All other time periods prepartum were based on this point.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA [MIXED procedure of SAS 9.4 (SAS Inst. Inc., Cary, NC)] in 3 separate analyses for each experiment: by day during the final 72 h prepartum (days −3, −2, and −1), by 6-h period during the final 24 h prepartum (hours −23 to −18, −17 to −12, −11 to −6, and −5 to 0), and by hour during the final 6 h prepartum (hours −5, −4, −3, −2, −1, and 0). For Exp. 1, the fixed effects of time prepartum and year were included in the model. The fixed effects of time prepartum, parity, and their interaction were included in the model for Exp. 2. For Exp. 3, only the fixed effect of time prepartum was included in the model. Animal was the experimental unit for all experiments. Time prepartum was considered a repeated effect for all models, and the best-fit covariance structure (chosen from compound symmetry, heterogeneous compound symmetry, autoregressive, heterogeneous autoregressive, and unstructured) was used for all analyses. Least squares means were separated using least significant difference and considered significant when P ≤ 0.05. Main effects and interactions were reported when P ≤ 0.05 with tendencies considered when P ≤ 0.10 and P > 0.05. In the absence of interactions, main effects of time and parity are reported for Exp. 2.

RESULTS

Final 72 h Prepartum

Day affected (P < 0.001) motion index, standing time, lying time, step count, and number of lying bouts for spring-calving multiparous dams in Exp. 1 (Table 2). Motion index was greater (P < 0.001) on day −1 than days −2 and −3. Cows spent greater (P ≤ 0.001) time standing on day −1 than day −2 or −3. Because standing and lying are inversely related, dams spent less (P ≤ 0.001) time lying on day −1 than day −2 or −3. Step count was also greater (P ≤ 0.001) on day −1 when compared with day −2 or −3. Additionally, cows had a greater (P < 0.001) number of lying bouts on day −1 than on days −2 and −3. There were no differences (P ≥ 0.1) between days −3 and −2 for any measures of activity. There was an effect of year (P = 0.03) for step count, but year did not affect any other parameters measured (P ≥ 0.39).

Table 2.

Locomotor activity during the 72 h prior to calving in multiparous spring-calving (Exp. 1) and fall-calving (Exp. 3) beef cows

| Day1 | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | −3 | −2 | −1 | SEM | Day | Year2 |

| Spring-calving (Exp. 1)3 | ||||||

| Motion index4 | 4,040b | 3,871b | 7,049a | 417 | <0.001 | 0.39 |

| Standing time, min | 736.5b | 752.5b | 910.6a | 16.8 | <0.001 | 0.83 |

| Lying time, min | 703.5a | 687.5a | 529.4b | 16.8 | <0.001 | 0.83 |

| Step count | 980b | 949b | 1,725a | 71.1 | <0.001 | 0.03 |

| Lying bouts5 | 10.4b | 10.3b | 22.0a | 0.70 | <0.001 | 0.82 |

| Fall-calving (Exp. 3)6 | ||||||

| Motion index | 6,478b | 6,521b | 9,740a | 536 | <0.001 | — |

| Standing time, min | 707.1b | 721.9b | 907.3a | 31.3 | <0.001 | — |

| Lying time, min | 732.9a | 718.1a | 532.7b | 31.3 | <0.001 | — |

| Step count | 1,496b | 1,499b | 2,408a | 145 | <0.001 | — |

| Lying bouts | 10.9b | 10.7b | 17.4a | 0.89 | <0.001 | — |

a,bWithin an item, main effect means differ (P ≤ 0.05).

1Hour 0 was defined as the hour increment nearest to parturition in which the majority of time represented prepartum behavior.

2Because data were collected over the course of 2 calving seasons (2015 and 2016), year was included in the statistical model for that experiment only.

3 n = 34 and 27 in years 1 and 2, respectively.

4Proprietary index in which the value is arbitrary.

5Any length of time in which dam laid down and then returned to standing.

6 n = 33.

Motion index, standing time, lying time, step count, and number of lying bouts were also affected (P < 0.001) by day in fall-calving multiparous dams in Exp. 3 (Table 2). These cows had the same changes in activity as Exp. 1 for all parameters (P < 0.001), with the day prior to calving being different than days −2 and −3.

In Exp. 2, the interaction of day × parity affected (P = 0.002) number of lying bouts in spring-calving females (Table 3). Both primiparous and multiparous dams had a greater (P ≤ 0.001) number of lying bouts on day −1 compared with days −2 and −-3, but primiparous dams had more (P = 0.02) lying bouts than multiparous dams on day −1. Despite this, parity and the parity × day interaction did not affect (P > 0.17) all other parameters. There was an effect of day (P <0.001) for motion index, standing and lying time, and step count. Motion index, standing time, and step count were greater (P < 0.001), and lying time less (P < 0.001), on day −1 than days −2 and −3, as observed in Exp. 1 and 3.

Table 3.

Locomotor activity during the 72 h prior to calving in primiparous and multiparous spring-calving beef cows (Exp. 2)

| Day1 | Parity | P-value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | −3 | −2 | −1 | SEM | 12 | ≥23 | SEM | Day | Parity | Day × parity |

| Motion index4 | 5,842b | 5,727b | 8,344a | 664 | 6,949 | 6,326 | 742 | <0.001 | 0.52 | 0.23 |

| Standing time, min | 784.1b | 780.7b | 908.5a | 18.4 | 843.1 | 805.8 | 20.9 | <0.001 | 0.17 | 0.81 |

| Lying time, min | 655.9a | 659.3a | 531.5b | 18.4 | 596.9 | 634.2 | 20.9 | <0.001 | 0.17 | 0.81 |

| Step count | 1,458b | 1,434b | 2,093a | 151 | 1,720 | 1,603 | 171 | <0.001 | 0.60 | 0.22 |

| Lying bouts5 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.002 |

| Primiparous | 10.94y | 9.54yz | 24.62w | 1.76 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Multiparous | 8.49z | 9.33yz | 19.10x | 1.38 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

a,bWithin an item, main effect means differ (P ≤ 0.05).

x–zWithin an item, interactive means differ (P ≤ 0.05).

1Hour 0 was defined as the hour increment nearest to parturition in which the majority of time represented prepartum behavior.

2Primiparous n = 13.

3Multiparous n = 21.

4Proprietary index in which the value is arbitrary.

5Any length of time in which dam laid down and then returned to standing.

Final 24 h Prepartum

In spring-calving multiparous dams (Exp. 1), 6-h time period within the last 24 h prepartum affected all parameters (P ≤ 0.01; Table 4). Motion index and step count were greater (P < 0.001) during the last 6 h prepartum than all other periods (Table 4). Standing time was greater (P ≤ 0.01) during the −5 to 0 h and −23 to −18 h periods than during the −11 to −6 h period, with lying time being the inverse. Lying bout number during the final 24 h increased (P < 0.001) during the −17 to −12 h period and again during the final 6-h period. There was an effect of year (P ≤ 0.02) for all parameters except step count (P = 0.22) in this experiment.

Table 4.

Locomotor activity by 6-h period during the 24 h prior to calving in multiparous spring-calving (Exp. 1) and fall-calving (Exp. 3) beef cows

| Time period1, h | P-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | −23 to −18 | −17 to −12 | −11 to −6 | −5 to 0 | SEM | Period | Year2 |

| Spring-calving (Exp. 1)3 | |||||||

| Motion index4 | 1,359b | 1,292b | 1,460b | 3,053a | 179 | <0.001 | 0.02 |

| Standing time, min | 239.1a | 224.5ab | 211.5b | 240.7a | 9.7 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Lying time, min | 120.9b | 135.5ab | 148.5a | 119.4b | 9.7 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Step count | 326.5b | 312.5b | 357.2b | 725.3a | 69.5 | <0.001 | 0.22 |

| Lying bouts5 | 2.06c | 3.39b | 3.88b | 12.42a | 0.69 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Fall-calving (Exp. 3)6 | |||||||

| Motion index | 2,083b | 2,122b | 1,946b | 3,477a | 268 | <0.001 | — |

| Standing time, min | 222.3ab | 231.6a | 198.6b | 250.9a | 14.7 | <0.001 | — |

| Lying time, min | 137.7ab | 128.4b | 161.4a | 109.1b | 14.7 | <0.001 | — |

| Step count | 493.8b | 512.3b | 488.0b | 890.2a | 72.4 | <0.001 | — |

| Lying bouts | 2.39c | 2.56bc | 3.17b | 9.39a | 0.65 | <0.001 | — |

a–cWithin an item, main effect means differ (P ≤ 0.05).

1Hour 0 was defined as the hour increment nearest to parturition in which the majority of time represented prepartum behavior.

2Because data were collected over the course of 2 calving seasons (2015 and 2016), year was included in the statistical model for that experiment only.

3 n = 34 and 27 in years 1 and 2, respectively.

4Proprietary index in which the value is arbitrary.

5Any length of time in which dam laid down and then returned to standing.

6 n = 33.

In fall-calving multiparous dams (Exp. 3), period within the final 24 h prepartum also affected (P ≤ 0.001) all parameters (Table 4). Again both motion index and step count were greater (P < 0.001) during the last 6 h prepartum compared with all other periods. Standing time was greater (P < 0.001) from −5 to 0 h than −11 to −6 h time period, but −5 to 0 h was not different (P ≥ 0.09) from −23 to −18 and −17 to −12 h periods. The same was true for lying time, with cows lying less (P < 0.001) from −5 to 0 h than −11 to −6 h. Lying bout number was greatest (P < 0.001) during the −5 to 0 h time period. Additionally, lying bout number was greater (P = 0.02) during −11 to −6 h compared with −23 to −18 h; however, −17 to −12 h was not different (P ≤ 0.06) from −11 to −6 h or −23 to −18 h periods.

Parity and the interaction of period x parity did not affect (P ≥ 0.19) motion index, standing time, lying time, or step count when analyzed by 6-h periods during the final 24 h of Exp. 2 (Table 5). There was an interaction of period × parity for lying bouts (P = 0.03), where primiparous females had a greater (P < 0.001) number of lying bouts than multiparous females during the −11 to −6 h period. Lying bouts increased (P < 0.001) during the last 6-h period when compared with the previous 18 h for both primiparous and multiparous dams. Additionally, multiparous dams had more (P = 0.03) lying bouts from −17 to −12 h than −23 to −18 h and primiparous dams had more (P = 0.002) lying bouts from −11 to −6 h than −17 to −12 h. There was an effect of period (P ≤ 0.01) on all other parameters. Motion index and step count were greater (P ≤ 0.001) during the final 6 h prepartum than all previous 6-h periods. Females spent more (P ≤ 0.02) time standing from −5 to 0 h prepartum than the 2 preceding 6-h periods. Time spent standing was also decreased (P = 0.04) during the −11 to −6 h period when compared with −23 to −18 h.

Table 5.

Locomotor activity by 6-h period during the 24 h prior to calving in primiparous and multiparous spring-calving beef cows (Exp. 2)

| Time period1, h | Parity | P-value | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | −23 to −18 | −17 to −12 | −11 to −6 | −5 to 0 | SEM | 12 | ≥23 | SEM | Period | Parity | Period × parity |

| Motion index4 | 1,699b | 1,493b | 1,368b | 3,783a | 368 | 2,187 | 1,985 | 194 | <0.001 | 0.42 | 0.37 |

| Standing time, min | 239.4ab | 211.8bc | 202.7c | 254.6a | 11.8 | 231.5 | 222.8 | 7.3 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 0.19 |

| Lying time, min | 120.6bc | 148.2ab | 157.3a | 105.4c | 11.8 | 128.5 | 137.2 | 7.3 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 0.19 |

| Step count | 432.2b | 375.8b | 354.3b | 930.4a | 90.7 | 540.4 | 505.9 | 45.5 | <0.001 | 0.56 | 0.26 |

| Lying bouts5 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Primiparous | 2.31yz | 2.77y | 4.46x | 15.08w | 1.51 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Multiparous | 1.86z | 2.57y | 2.33yz | 12.33w | 1.18 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

a–cWithin an item, main effect means differ (P ≤ 0.05).

w–zWithin an item, interactive means differ (P ≤ 0.05).

1Hour 0 was defined as the hour increment nearest to parturition in which the majority of time represented prepartum behavior.

2Primiparous, n = 13.

3Multiparous, n = 21.

4Proprietary index in which the value is arbitrary.

5Any length of time in which dam laid down and then returned to standing.

Final 6 h Prepartum

In spring-calving multiparous dams (Exp. 1), there was an effect of hour (P ≤ 0.001) for motion index, step count, and lying bouts during the final 6 h prepartum (Table 6). Motion index increased (P = 0.002) at −3 h and again at −1 h prior to calving. Step count was greater (P = 0.001) during the last 4 h, with −1 h having a greater (P ≤ 0.05) number of steps taken than −3 and 0 h relative to calving. Lying bouts increased (P ≤ 0.001) from −5 h to −3 h relative to calving. The number of lying bouts more than doubled (P < 0.001) from −2 to −1 h and increased (P = 0.001) during the hour in which calving occurred. There tended to be an effect of hour (P = 0.09) for standing and lying time, where cows spent greater (P = 0.02) time standing at −2 h compared with −5, −4, −3, and 0 h relative to calving. There was an effect of year (P ≤ 0.009) for all parameters except lying bouts (P = 0.57).

Table 6.

Locomotor activity by hour during the 6 h prior to calving in multiparous spring-calving (Exp. 1) and fall-calving (Exp. 3) beef cows

| Hour1 | P-value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | −5 | −4 | −3 | −2 | −1 | 0 | SEM | Hour | Year2 |

| Spring-calving (Exp. 1)3 | |||||||||

| Motion index4 | 304.8c | 356.1c | 485.3b | 561.3b | 730.8a | 637.6ab | 96.5 | <0.001 | 0.02 |

| Standing time, min | 36.38b | 37.73b | 40.78b | 44.72a | 42.67ab | 39.06b | 2.76 | 0.09 | 0.009 |

| Lying time, min | 23.62a | 22.27a | 19.22a | 15.28b | 17.33ab | 20.94a | 2.76 | 0.09 | 0.009 |

| Step count | 77.2c | 90.0c | 121.1b | 139.6ab | 173.5a | 138.3b | 23.3 | 0.001 | 0.004 |

| Lying bouts5 | 0.77d | 1.09cd | 1.29c | 1.42c | 3.06b | 4.81a | 0.50 | <0.001 | 0.57 |

| Fall-calving (Exp. 3)6 | |||||||||

| Motion index | 356.4c | 500.9b | 567.4ab | 649.9ab | 686.8a | 715.8a | 66.2 | 0.006 | — |

| Standing time, min | 39.53 | 43.39 | 41.46 | 42.99 | 42.11 | 41.41 | 3.45 | 0.92 | — |

| Lying time, min | 20.47 | 16.61 | 18.54 | 17.01 | 17.89 | 18.59 | 3.45 | 0.92 | — |

| Step count | 93.0c | 127.6bc | 145.2ab | 170.0ab | 182.0a | 172.5ab | 17.8 | 0.02 | — |

| Lying bouts | 0.48c | 0.64c | 0.76c | 1.18b | 2.73a | 3.61a | 0.49 | <0.001 | — |

a–dWithin an item, main effect means differ (P ≤ 0.05).

1Hour 0 was defined as the hour increment nearest to parturition in which the majority of time represented prepartum behavior.

2Because data were collected over the course of 2 calving seasons (2015 and 2016), year was included in the statistical model for that experiment only.

3 n = 34 and 27 in years 1 and 2, respectively.

4Proprietary index in which the value is arbitrary.

5Any length of time in which dam laid down and then returned to standing.

6 n = 33.

In fall-calving multiparous dams (Exp. 3), hour affected (P ≤ 0.02) motion index, step count, and lying bouts (Table 6). Motion index increased (P = 0.001) from −5 to −4 h, and cows had greater (P ≤ 0.03) motion index during 0 and −1 h than −4 and −5 h. Step count was greater (P = 0.02) from −3 to 0 h than at −5 h relative to calving, with no difference (P ≥ 0.06) among the last 4 h pre-calving. Lying bout number for fall-calving dams was greater (P < 0.001) at −1 and 0 h relative to calving than other hours, and more than doubled (P < 0.001) from −2 to −1 h prior to calving. Lying bout number also increased (P < 0.001) from −3 to −2 h. Unlike the spring-calving cows in Exp. 1, there was no effect of hour (P = 0.92) for standing and lying time in the fall-calving herd.

There was no interaction of day × parity (P ≥ 0.61) or main effect of parity (P ≥ 0.29) for any variable during the final 6 h prior to parturition in Exp. 2 (Table 7). There was an effect of hour (P < 0.001) on motion index, step count, and lying bouts. Motion index was greater (P ≤ 0.001) during −2, −1, and 0 h prepartum compared with −5, −4, and −3 h, with no difference (P ≥ 0.33) among the last 3 h prior to calving. Step count was greater (P ≤ 0.001) during −1 and −2 h than −3, −4, and −5 h, with no difference (P ≥ 0.06) among the last 3 h prior to calving. Lying bouts increased (P ≤ 0.001) from −4 to −3 h, −3 to −2 h, and more than doubled from −2 to −1 h. Lying bout number during −1 h was not different (P = 0.50) from 0 h relative to calving. There tended to be an effect of hour (P = 0.08) for standing and lying time, where greater (P = 0.02) time was spent lying at 0 h prior to calving when compared with −2 and −4 h. There were no differences (P ≥ 0.06) among −5, −4, −3, and −2 h or between −1 and 0 h relative to calving for standing or lying time.

Table 7.

Locomotor activity by hour during the 6 h prior to calving in primiparous and multiparous spring-calving beef cows (Exp. 2)

| Hour1 | Parity | P-value | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | −5 | −4 | −3 | −2 | −1 | 0 | SEM | 12 | ≥23 | SEM | Hour | Parity | Hour x Parity |

| Motion index4 | 408.4b | 400.4b | 521.6b | 799.6a | 864.8a | 788.4a | 116.1 | 623.8 | 637.3 | 96.4 | <0.001 | 0.91 | 0.67 |

| Standing time, min | 44.38abc | 45.78ab | 42.60abc | 46.06a | 38.56bc | 37.19c | 2.77 | 41.99 | 42.87 | 2.42 | 0.08 | 0.78 | 0.61 |

| Lying time, min | 15.62abc | 14.22bc | 17.40abc | 13.94c | 21.44ab | 22.81a | 2.77 | 18.01 | 17.13 | 2.42 | 0.08 | 0.78 | 0.61 |

| Step count | 108.5c | 103.8c | 135.7bc | 205.6a | 206.1a | 170.8ab | 21.1 | 150.3 | 159.9 | 22.8 | <0.001 | 0.74 | 0.94 |

| Lying bouts5 | 0.49d | 0.72d | 1.24c | 2.17b | 4.75a | 4.34a | 0.59 | 2.51 | 2.06 | 0.33 | <0.001 | 0.29 | 0.67 |

a–dWithin an item, main effect means differ (P ≤ 0.05).

1Hour 0 was defined as the hour increment nearest to parturition in which the majority of time represented prepartum behavior.

2Primiparous, n = 13.

3Multiparous, n = 21.

4Proprietary index in which the value is arbitrary.

5Any length of time in which dam laid down and then returned to standing.

DISCUSSION

An understanding of maternal locomotor activity changes as beef females near parturition may enable the use of quantitative behavioral data to predict time of calving, rather than qualitative behavioral monitoring alone. Remote detection of calving in a herd setting through prediction technology could reduce calf mortality caused by dystocia or other calving-related problems (Saint-Dizier and Chastant-Maillard, 2015). While previous research has indicated that locomotion behavioral changes are useful for calving prediction in dairy cattle, this is the first study to examine this in beef cattle to our knowledge. Overall, the results of this study suggest that accelerometers could be used to recognize early signs of parturition in beef cattle because changes in activity can be observed during the last 6 h prepartum in both multiparous and primiparous beef dams, as well as both spring-calving and fall-calving herds. The results of these studies indicate that future research using locomotion behavior in beef dams could be explored for the creation of calving prediction technologies, although other parameters that may influence maternal behavior detection such as enclosure size and calving environments should also be investigated.

Locomotion Changes at Calving

Standing and lying time.

In all 3 experiments, females had greater standing time and less lying time on the day of calving compared with 2 and 3 d prior to calving. In dairy cattle, an 80% increase in standing activity during the 24 h prior to calving occurred during the peripartum period (defined as 24 h pre- and post-calving) compared with the preceding days, indicating that animals spent less time recumbent (Huzzey et al., 2005). This increase in standing time was also reported on the last day, during the 24 h prior and 12 h prior to calving (Huzzey et al., 2005; Titler et al., 2015; Borchers et al., 2017). Across our 3 experiments, more time was spent recumbent at −11 to −6 h period compared with the last 6-h period prepartum, regardless of parity or calving season. This agrees with previous data from dairy cows where less time was spent lying during the last 6- and 2-h periods (Miedema et al., 2011b; Borchers et al., 2017).

When comparing the last 6 h pre-calving, there was no effect of hour for standing and lying time during the last 6 h in Exp. 3, but there tended to be a difference in Exp. 1 and 2 with an effect of year in Exp. 1. Both Exp. 1 and 2 utilized spring-calving females, suggesting that standing and lying time during the last 6 h may be sensitive to differences in ambient temperature, individual herd dynamics (as spring- and fall-calving herds are maintained separately on this operation), or dam temperament specific to each herd. These parameters may still be helpful in determining when cows are near calving, but additional research is necessary to investigate factors that affect them.

Step count.

Recent research with dairy cattle has shown that electronic data loggers did not detect a change in step count during the 2 wk prior to calving (Borchers et al., 2017); however, an earlier dairy study reported an increase in number of steps within the 12 h immediately prior to calving (Titler et al., 2015). Our data demonstrate an increase in number of steps taken during the final day when compared with days −3 and −2 prior to calving, with an increase in step number most specifically occurring during the last 3 h prepartum. This increase in steps could be due to females walking in search for a safe place to calve, seeking isolation from the herd, or pacing due to discomfort (Wehrend et al., 2006; Proudfoot et al., 2014). This increase may occur in small enough increments that previous research comparing individual days did not detect a difference; however, it may be useful in determining behavioral differences within a few hours of calving. Step count differences may also be detected in beef cattle more readily than in dairy cattle because of differences in temperament or housing. In the current study, beef dams were housed outdoors and in larger pens as opposed to indoor barns often used in the dairy industry.

Lying bout number.

In agreement with the current study, an increase in number of lying bouts within the final 24 h prepartum has been shown in dairy cattle (Miedema et al., 2011b; Titler et al., 2015; Ouellet et al., 2016; Borchers et al., 2017). Our study examined smaller units of time pre-calving than previous studies, allowing for the observation of a significant increase in lying bouts during the last 6 h. In all 3 experiments, average lying bout number more than doubled from −2 to −1 h prepartum. In spring-calving cows (Exp. 1), lying bouts continued to increase, and females had the greatest number of lying bouts during the hour of calving (0 h). Despite this, an increase in lying bouts between −1 and 0 h did not occur in Exp. 2 and 3. This difference between calving seasons may again be due to differences in dam temperament between herds or because fall-calving dams were mildly heat stressed and therefore less active after finding a comfortable place to calve. Although data were not compared statistically among current experiments, cows in Exp. 3 had the numerically fewest lying bouts during the hour of calving.

In Exp. 1, the number of lying bouts did not have an effect of year, unlike other parameters measured during the last 6 h prior to calving. Because the lying bout increase −1 h prepartum in all 3 experiments was consistently around twice that of −2 h, this parameter appears to be the most reliable indicator of behavioral changes relative to calving in the current study. This increase in frequency of standing and lying back down is another example of restlessness associated with earlier signs of labor (Owens et al., 1985; Wehrend et al., 2006). Furthermore, this time period precalving would be a useful time for notification of impending calving to monitor for dystocia.

With our method of analysis, time of beginning stage II parturition and time of fetal membrane rupture are included some time prior to the time of calf delivery, which may be within 0 h or earlier, depending on the duration of labor. Initial parturition-related recumbent behavior in cattle often begins as the calf enters the birth canal (Schuenemann et al., 2011). From an observational standpoint, many dams continue to be restless and frequently get up and down after stage II parturition begins, including after fetal membrane rupture. This discomfort may be expressed as the behavioral changes detected immediately prior to calving. Future studies where labor duration or specific events of parturition (stages, membrane rupture, presence of calf feet, head, etc.) are observed may be useful in further determining the utility of lying bouts in calving detection.

Motion index.

The motion index algorithm was developed by iceRobotics to indicate the total activity using a combination of all locomotor variables measured, where a greater numerical motion index indicates that cattle are more active. In the current study, the predominant increase in motion index occurred during the last few hours prior to calving, with this increase likely attributed to the activity of changing standing and lying status frequently as observed with the increase in number of lying bouts in addition to the number of steps taken. Motion index was summed by day in a dairy study with no difference during the last 4 d of gestation; however, overall activity was increased on the day prior to calving when compared with a week prior (Borchers et al., 2017). This indicates that motion indexing may be capable of predicting changes in behavior by combining multiple motion variables that are necessary in the establishment of calving prediction and detection technologies as used with research in dairy cattle (Titler et al., 2015; Borchers et al., 2017).

Parity Effects

In dairy cattle, primiparous females spent less time standing during the final 24 h pre-calving compared with multiparous cows (Titler et al., 2015). Additionally, primiparous dairy heifers spent more of the final 2 h prepartum recumbent compared with multiparous cows in another study (Miedema et al., 2011a). This was attributed to primiparous females spending more time in labor and having more contractions during parturition (Miedema et al., 2011a; Schuenemann et al., 2011). Other studies in dairy cattle reported differences between parities with increased restlessness a week prior to calving in primiparous dams, demonstrated by increased neck movement activity, pawing, and tail swishing (Wehrend et al., 2006; Borchers et al., 2017). While an effect of parity has been observed for multiple measurements of restlessness in dairy dams, few differences were noted for primiparous versus multiparous dams in Exp. 2.

The restlessness attributed to primiparous dams may be evidenced in other variables for beef dams such as number of lying bouts, as parity affected this parameter in a time-dependent manner in the current study. On the day prior to calving and during the final 6-h period prior to calving, primiparous dams had an increased number of lying bouts when compared with multiparous dams. This suggests that primiparous dams are more restless and change their activity from lying to standing more frequently resulting in shorter, more frequent lying bouts. Parity did not affect lying bout number within the final 6 h precalving, indicating that this increase in restlessness of heifers occurs earlier during or prior to stage I of parturition.

When analyzing the last 6 h prior to calving, lying bouts increased for both primiparous and multiparous dams, as the mean number of lying bouts more than doubled from hours −2 to −1 relative to calving. This suggests that lying bouts may be a good tool for prediction of calving in beef females regardless of parity. Results of the current study are similar to others in dairy cattle where the number of lying bouts increased on the day prior to calving with no effect of parity (Jensen, 2012; Borchers et al., 2017). Because these studies did not compare time periods within the 24 h prior to calving, it is important to note that the algorithm created for calving detection in dairy dams may not be applicable to beef cattle where parity had an effect on lying bouts when comparing by day.

There was no difference in motion index between multiparous and primiparous dams, suggesting that the increase in activity occurs independent of parity. Previously an effect of parity was detected 4 h prior to calving in dairy cattle which was attributed to discomfort at calving (Borchers et al., 2017). Drivers of the difference in motion index between parities during these last 4 h cannot be interpreted due to the proprietary nature of the motion index algorithm. Alternate index development may be useful as further research is conducted and accounts for factors such as difference in beef and dairy cattle, environment, and parity.

Other Factors That May Impact Calving Behavior

While season effects were not statistically tested in the current study, similar trends were observed in behavior of both spring- and fall-calving multiparous dams (Exp. 1 and 2 vs. Exp. 3). There were numerical differences for most parameters between the 2 seasons which were likely due to differences in animal temperament, herd dynamics, weather, and feeding behavior. Despite this, data interpretations are largely similar between calving seasons. Because increases in locomotion behavior were observed at similar time points, we believe that prepartum behavioral changes in beef females can be detected by accelerometers regardless of calving season.

The same spring cow herd was used in both years of Exp. 1, with some animal additions (3-yr olds entering the mature herd) and culling. Thus, year effects (means not shown) could be due to acclimation to increased human interaction, differences in neonatal sampling, weather differences between years, or other unknown factors.

In all 3 experiments, dams were housed in the same calving pens. Future research is necessary to determine if behavior varies among calving environments, as a change in pen size, footing, and forage delivery may lead to a difference in herd dynamics and overall activity. There may also be behavioral differences based on location of shelters and with animals on pasture. This is supported by research in dairy cattle where conflicting behavioral changes were reported between studies where females were moved to maternity pens at the appearance of calf’s feet outside the vulva in one study and moved to maternity pens at least a day prior to calving in another study (Huzzey et al., 2005; Titler et al., 2015). In dairy cattle, the movement of animals at various stages of parturition has shown to have an effect on behavior of dams (Proudfoot et al., 2013). Because of this, animals that moved outside of normal patterns for the current study were not included to prevent any influence on overall calving behavioral data interpretation.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the current study demonstrates that locomotion behavior of beef cows and heifers increases during the 24 h prior to calving. This increased activity was most notable during the final 6 h prepartum, with many additional differences observed within the last 2 to 4 h before calving. In this study, the number of lying bouts had the most consistent change during this time period and was unaffected by parity. Lying bout changes occurred in both spring- and fall-calving seasons. This behavior may be a key tool in predicting nearness of calving in beef dams. More research in this area may allow for development of methods for detecting calving via machine learning combined with accelerometers with remote sensing capability. This technology likely presents an opportunity to optimize precision calving management, decreasing calf mortality or neonatal morbidity due to dystocia and other challenges associated with parturition. Additionally, this technology could allow for improved calving detection without human interference in research settings where the physiological or behavioral data or samples are collected in the peripartum period.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Brian Vander Ley (Great Plains Veterinary Education Center, Clay Center, NE); graduate students Katlyn Niederecker, Jill Larson, and Emma Stephenson; undergraduate assistants from the Meyer lab; and the University of Missouri Beef Research and Teaching Farm for assistance with this project.

LITERATURE CITED

- Berger P. J., Cubas A. C., Koehler K. J., and Healey M. H.. 1992. Factors affecting dystocia and early calf mortality in Angus cows and heifers. J. Anim. Sci. 70:1775–1786. doi:10.2527/1992.7061775x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchers M. R., Chang Y. M., Proudfoot K. L., Wadsworth B. A., Stone A. E., and Bewley J. M.. 2017. Machine-learning-based calving prediction from activity, lying, and ruminating behaviors in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 100:5664–5674. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-11526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchers M. R., Chang Y. M., Tsai I. C., Wadsworth B. A., and Bewley J. M.. 2016. A validation of technologies monitoring dairy cow feeding, ruminating, and lying behaviors. J. Dairy Sci. 99:7458–7466. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-10843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzozowska A., Łukaszewicz M., Sender G., Kolasińska D., and Oprządek J.. 2014. Locomotor activity of dairy cows in relation to season and lactation. Appl. Anim. Beh. Sci. 156:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2014.04.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dargatz D. A., Dewell G. A., and Mortimer R. G.. 2004. Calving and calving management of beef cows and heifers on cow-calf operations in the United States. Theriogenology 61:997–1007. doi: 10.1016/S0093-691X(03)00145-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney G., Gordon A., Scoley G., and Morrison S. J.. 2018. Validating the IceRobotics IceQube tri-axial accelerometer for measuring daily lying duration in dairy calves. Livest. Sci. 214:83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2018.05.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fogsgaard K. K., Bennedsgaard T. W., and Herskin M. S.. 2015. Behavioral changes in freestall-housed dairy cows with naturally occurring clinical mastitis. J. Dairy Sci. 98:1730–1738. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-8347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huzzey J. M., von Keyserlingk M. A., and Weary D. M.. 2005. Changes in feeding, drinking, and standing behavior of dairy cows during the transition period. J. Dairy Sci. 88:2454–2461. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72923-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M. B. 2012. Behaviour around the time of calving in dairy cows. Appl. Anim. Beh. Sci. 139:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2012.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mattachini G., Riva E., Bisaglia C., Pompe J. C., and Provolo G.. 2013. Methodology for quantifying the behavioral activity of dairy cows in freestall barns. J. Anim. Sci. 91:4899–4907. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miedema H. M., Cockram M. S., Dwyer C. M., and Macrae A. I.. 2011a. Behavioural predictors of the start of normal and dystocic calving in dairy cows and heifers. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 132:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2011.03.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miedema H. M., Cockram M. S., Dwyer C. M., and Macrae A. I.. 2011b. Changes in the behaviour of dairy cows during the 24 h before normal calving compared with behaviour during late pregnancy. Appl. Anim. Beh. Sci. 131:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2011.01.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niederecker K. N., Larson J. M., Kallenbach R. L., and Meyer A. M.. 2018. Effects of feeding stockpiled tall fescue versus tall fescue hay to late gestation beef cows: I. Cow performance, maternal metabolic status, and fetal growth. J. Anim. Sci. doi: 10.1093/jas/sky341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen L. R., Pedersen A. R., Herskin M. S., and Munksgaard L.. 2010. Quantifying walking and standing behaviour of dairy cows using a moving average based on output from an accelerometer. Appl. Anim. Beh. Sci. 127:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2010.08.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellet V., Vasseur E., Heuwieser W., Burfeind O., Maldague X., and Charbonneau É.. 2016. Evaluation of calving indicators measured by automated monitoring devices to predict the onset of calving in Holstein dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 99:1539–1548. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-10057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens J. L., Edey T. N., Bindon B. M., and Piper L. R.. 1985. Parturient behaviour and calf survival in a herd selected for twinning. Appl. Anim. Beh. Sci. 13:321–333. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(85)90012-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pillen J. L., Pinedo P. J., Ives S. E., Covey T. L., Naikare H. K., and Richeson J. T.. 2016. Alteration of activity variables relative to clinical diagnosis of bovine respiratory disease in newly received feedlot cattle. Bov. Pract. 50:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot K. L., Jensen M. B., Heegaard P. M., and von Keyserlingk M. A.. 2013. Effect of moving dairy cows at different stages of labor on behavior during parturition. J. Dairy Sci. 96:1638–1646. doi: 10.3168/jds.2012-6000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot K. L., Jensen M. B., Weary D. M., and von Keyserlingk M. A.. 2014. Dairy cows seek isolation at calving and when ill. J. Dairy Sci. 97:2731–2739. doi: 10.3168/jds.2013-7274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richeson J., Lawrence T., and White B.. 2018. Using advanced technologies to quantify beef cattle behavior. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2:223–229. doi: 10.1093/tas/txy004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Dizier M., and Chastant-Maillard S.. 2015. Methods and on-farm devices to predict calving time in cattle. Vet. J. 205:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2015.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuenemann G. M., Nieto I., Bas S., Galvão K. N., and Workman J.. 2011. Assessment of calving progress and reference times for obstetric intervention during dystocia in Holstein dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 94:5494–5501. doi: 10.3168/jds.2011-4436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titler M., Maquivar M. G., Bas S., Rajala-Schultz P. J., Gordon E., McCullough K., Federico P., and Schuenemann G. M.. 2015. Prediction of parturition in Holstein dairy cattle using electronic data loggers. J. Dairy Sci. 98:5304–5312. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-9223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai I. C. 2017. Differences in behavioral and physiological variables measured with precision dairy monitoring technologies associated with postpartum diseases. MS Thesis. University of Kentucky, Lexington. [Google Scholar]

- Wehrend A., Hofmann E., Failing K., and Bostedt H.. 2006. Behaviour during the first stage of labour in cattle: influence of parity and dystocia. Appl. Anim. Beh. Sci. 100:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2005.11.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zaborski D., Grzesiak W., Szatkowska I., Dybus A., Muszynska M., and Jedrzejczak M.. 2009. Factors affecting dystocia in cattle. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 44:540–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2008.01123.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]