Abstract

The purpose of this review is to provide an overview of uranium speciation using vibrational spectroscopy methods including Raman and IR. Uranium is a naturally occurring, radioactive element that is utilized in the nuclear energy and national security sectors. Fundamental uranium chemistry is also an active area of investigation due to ongoing questions regarding the participation of 5f orbitals in bonding, variation in oxidation states and coordination environments, and unique chemical and physical properties. Importantly, uranium speciation affects fate and transportation in the environment, influences bioavailability and toxicity to human health, controls separation processes for nuclear waste, and impacts isotopic partitioning and geochronological dating. This review article provides a thorough discussion of the vibrational modes for U(IV), U(V), and U(VI) and applications of infrared absorption and Raman scattering spectroscopies in the identification and detection of both naturally occurring and synthetic uranium species in solid and solution states. The vibrational frequencies of the uranyl moiety, including both symmetric and asymmetric stretches are sensitive to the coordinating ligands and used to identify individual species in water, organic solvents, and ionic liquids or on the surface of materials. Additionally, vibrational spectroscopy allows for the in situ detection and real-time monitoring of chemical reactions involving uranium. Finally, techniques to enhance uranium species signals with vibrational modes are discussed to expand the application of vibrational spectroscopy to biological, environmental, inorganic, and materials scientists and engineers.

Keywords: Uranium, Vibrational spectroscopy, Infrared, Raman

1. Introduction to uranium chemistry

Uranium, element number 92, is one of the most abundant radioactive metals and possesses a troubled history with regard to both its use in the energy and defense sectors and its impact on public health and environmental systems. The most abundant (99.3%) uranium isotope, 238U, is a primordial radionuclide with a half-life of 4.7 × 109 years and is found in the earth crust at an average concentration of 2.7 ppm [1,2]. Other isotopes, such as 233U, 234U, 235U, and 236U, occur at concentrations below 1% of natural abundance although their specific activity is higher than that of 238U. Due to its fissile nature, enriched uranium (3–5% 235U) is widely used in nuclear reactors for power generation and higher levels (20–90% 235U) are used for the development of nuclear weapons [2]. The enrichment process combined with mining and milling of natural uranium ore bodies generates radioactive waste. Additional waste is added after use in a nuclear reactor, where the solid product still contains 95% U that is now mixed with fission products and transuranic materials [3]. Characterizing the chemical nature of waste forms is important for reprocessing and/or long-term storage in a geologic repository so that impacts on the biosphere are minimized [4]. In addition, there are many sites around the world where abandoned uranium mines, tailing piles, or legacy waste are currently in need of remediation to reduce the risk to environmental systems or the public [5].

The complex chemistry of uranium dictates how the element behaves in natural waters, which will in-turn, impact transport processes and bioavailability. While uranium can exist in oxidation states between +3 and +6, the most common states in natural systems are +4 and +6 [6]. U(IV) is the dominate state in slightly oxidizing to anoxic conditions and typically forms insoluble (0.01 μg/L) hydrolysis and microbial mediated oxide products in natural waters [7,8]. These solids contain the U(IV) cation coordinated to 6–10 O atoms and possess interesting catalytic, semiconducting, and magnetic properties [9–11]. U(VI) exists in aerobic conditions and is relatively soluble in natural waters [8]. Bonding is quite unusual in U(VI) as it possesses strong, covalent bonds to two axial O atoms, creating the uranyl cation, [U(VI)O2]2+ [12]. Additional bonding to the uranyl moiety by four, five, or six equatorial ligands forms an overall coordination geometry of square, pentagonal, or hexagonal bipyramidal about the metal center [12]. U(VI) is also considered a hard Lewis acid and prefers to bond to O and N functional groups thus forming a range of soluble complexes and mineral phases in natural waters [8]. Speciation influences the overall solubility of U, ranging from 1 μg U/L for groundwater in equilibrium with vanadates to 120 mg U/L in the presence of carbonates and silicates [13]. Due to the complex chemistry of U(VI), important species for environmental systems can exist as soluble coordination complexes [8,14] and nanoclusters [15,16], colloids [17,18], amorphous precipitates [19,20], or surface adsorbed phases [21]. Pentavalent U(V) is often not mentioned in the discussion of environmental uranium chemistry because it is considered extremely unstable and readily disproportionates to U(IV) and U(VI) [22]; however, it has been observed as a stable phase on mica surfaces [23] and more recently been detected in a catalytic transformations of iron oxyhydroxide mineral phases [24–26].

Given the complexity of uranium chemistry in natural waters, it is important to develop tools to assess speciation, characterize solid phases, understand surface processes, and probe chemical mechanisms. Radiometric techniques, such as alpha spectrometry, quantify U in natural systems down to 0.22 mBq/L and provide isotopic ratios of the materials [27]. These methods, however, do not reveal chemical information on speciation or bonding. Powder and single X-ray diffraction techniques can detect and identify solid-state phases, but require milligram quantities of the material [28,29]. Higher-energy X-ray sources, such as those found at synchrotron facilities, overcome this limitation but require specialized instrumentation and dedicated staff support [30]. Mass spectrometry is more widely used and provides quantitative analysis along with some speciation information [31,32]. Isotopic effects and complex matrices, however, lead to difficulties in data analysis. There are also a wide range of spectroscopic techniques that have been used to characterize uranium compounds and solutions, including fluorescence [33–35], X-ray photoelectron [36], X-ray absorption [18,37,38], and vibrational spectroscopy [39]. Each of these techniques provides different chemical information regarding the complexation, coordination environment, bonding, and photoelectric properties although some are limited to either solution or solid phase (Table 1).

Table 1.

Instrumentation to assess the chemistry of uranium in solution and solid-state samples.

| Phase | Chemical Speciation/Coordination | Isotopic Ratios | Detection Limit/Dynamic Range | Complex Matrix Compatibility | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha Spectrometry | Solution | Poor | Excellent | 0.05 pCi/- | Poor |

| Liquid Scintillation Counter | Solution | Poor | Poor/Good | 50 pCi/- | Poor |

| X-ray Diffraction | Solid | Excellent | Poor | 1%/- | Poor |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy | Solid | Good | Poor | 0.1–1%/- | Poor |

| X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy | Solution/solid | Excellent | Poor | 1 × 10−6M/- | Good |

| X-ray Scattering | Solution | Excellent | Poor | 1 × 10−3 M/- | Fair |

| Mass Spectrometry | Solution | Good | Excellent | 1 × 10−11 M/- | Poor |

| Fluorescence | Solution/solid | Excellent | Poor | 5 × 10−6 M/5+ | Good |

| Time-Resolved Fluorescence Spectroscopy | Solution | Excellent | Poor | 1 × 10−7 M/5+ | Good |

| UV-Vis Absorption | Solution/solid | Poor | Poor | 1 × 10−6M/3+ | Good |

| Infrared Absorption | Solution/solid | Good | Poor | 1 × 10−7 M/3+ | Good |

| Raman Scattering | Solution/solid | Excellent | Poor | 1 × 10−5 M/2+ | Excellent |

One of the most versatile and wide-spread spectroscopic methods is based on measuring vibrational energies and encompasses both infrared (IR) absorption and Raman scattering. These complementary spectroscopic methods reveal information regarding bonding and local environment for compounds and species, including those for uranyl. While both methods rely on excitation of quantized vibrational-rotational energy levels in these samples, observed spectral features depend on unique selection rules. For infrared spectroscopy, a change in dipole moment must arise upon vibrational motion for the mode to be IR-active while a change in polariz-ability (i.e., distortion of the electron cloud) must occur similarly for a mode to be Raman-active. The asymmetric (ν3) and symmetric (ν1) uranyl stretches are the most probable and intense modes in IR and Raman spectra, respectively, and both are sensitive to coordinating ligands, local environment, and molecular geometries. These modes occur at different frequencies, however, because they require different amounts of energy to excite vibrational motion. Because water vibrational modes are silent or weak in Raman spectra, Raman spectroscopy is widely utilized for characterizing environmental and aqueous-phase uranyl samples, but the signals for uranyl are weak because of the probability of exciting the Raman-active modes is low. In comparison, water exhibits strong IR bands that interfere with uranyl detection from these samples unless attenuated total reflectance (ATR) cells are used. This approach works best for solid samples that can adhere to the ATR crystal so that the spectroscopic signal from water can be minimized. The signals are more intense in comparison to Raman spectral features but often exhibit a large background and/or features that overlap with other chemical species in the samples. Advanced vibrational spectroscopic methods have been developed for solution phases, solid materials, and surfaces [40,41]. Traditionally, one of the limitations of these methods was poor detection limits; but in more recent years, new technologies have been employed to enhance detection and provide additional chemical information.

The purpose of this review is to provide an overview of how uranium can be characterized using vibrational spectroscopy, including IR absorption and Raman scattering. Previous literature examinations focused on the detection and identification of uranium speciation using X-ray spectroscopy [42,43], time-resolved laser-induced fluorescence spectroscopy [44–46], and computational modeling [47]. An excellent review of IR vibrational frequencies of uranyl (VI) mineral compounds was also provided by Cejka in 1999, but the reported uses of vibrational spectroscopy for uranium chemistry has grown in number and significant advances in sample preparation and data analysis have increased in both breadth and depth; therefore, there is a critical need to provide an update on this important chemical technique [39]. We have also published a study investigating the best practices for collecting and analyzing Raman spectra in aqueous solutions, but determined that additional information was lacking in regards to the analysis of solid state samples and surfaces [48]. Building on the previous work by Cejka [39], the current review focuses on how both IR and Raman spectroscopies are used to characterize solid state uranium compounds; identify U adsorbed on surfaces; and provide speciation information within aqueous solutions, organic solvents, and ionic liquids. In addition, we explore the latest advances in uranium detection and provide an analysis of future needs and unanswered questions.

2. Detection and identification of uranium using vibrational spectroscopy

Vibrational spectroscopy is used to elucidate uranium speciation because each species possesses a unique vibrational frequency, which is influenced by the valence number, bond length, coordination ligands, structure, and local environment. Correct analysis of these complex data is of utmost importance. Careful analysis requires an understanding of (1) appropriate spectral windows relevant for uranyl speciation determination, (2) implications of possible vibrational band overlap arising from multiple uranyl species, and (3) impacts of coordinating ligands and phase on vibrational band widths. In the following section, we provide an overview of the overall spectral characteristics of uranium in different valence states and summarize additional information on proper data analysis.

2.1. Vibrational spectroscopy of U(IV)

U(IV) solids have variable coordination numbers, and UAO bonds contain substantial ionic character, leading to smaller vibrational mode cross sections and less intense vibrational bands. UO2 solid crystallizes in the fluorite Fm3m space group, and group theory predicts one IR and one Raman active mode [49]. With hyper-stoichiometric U(V) oxides, the fluorite lattice often distorts, leading to relatively lower symmetry structures and activation of more vibrational modes [49,50]. For instance, β-U4O9 forms in the I-43d space group with 7 crystallographically unique U and 14 O atoms [50]. Modeling suggests that modes consistent with UO2 and phonon lattice vibrations could arise in Raman analysis thus increasing the number of possible vibrational modes observed in this structure type by a factor of four [49]. Vibrational band broadening may also occur with increasing disorder within the crystalline lattice [50]. Based upon solubility limitations and the weak vibrational bands, the use of vibrational spectra in U(IV) solutions is rather limited. Often the use of absorption spectroscopy is more conducive for confirming the presence of U(IV) whereas vibrational spectroscopy is appropriate for identifying other inorganic or organic anions with active bands [51].

2.2. Vibrational spectroscopy of U(VI)

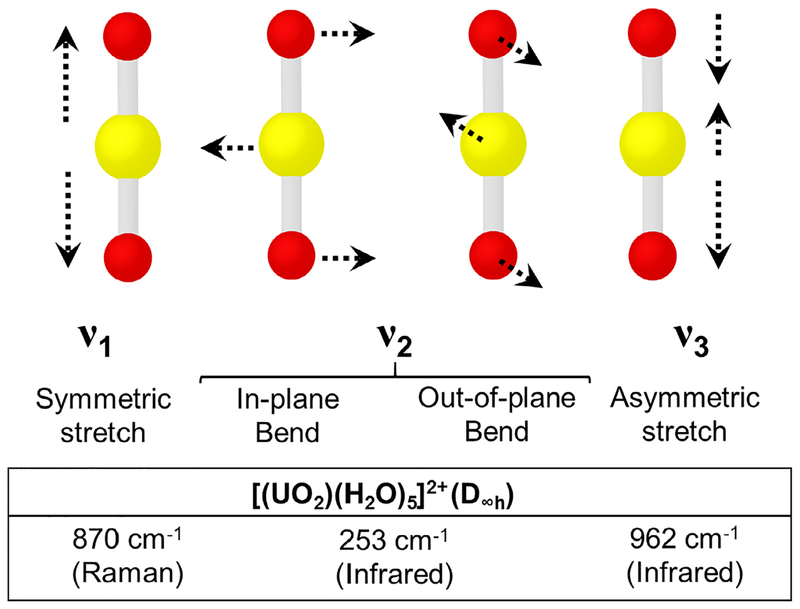

In contrast to the tetravalent state, U(VI) forms the uranyl cation, and displays strong active vibrational bands associated with the covalent axial bonds. There are three fundamental modes of vibration for the uranyl moiety (D∞h): the sym metric stretch (ν1), bend (ν2), and antisymmetric stretch (ν3) [39] (Fig. 1). The bending mode occurs in two mutually perpendicular planes making it degenerate. When the D∞h symmetry is maintained, the ν1 is Raman active, and ν2 and ν3 are IR active [39]. Symmetry lowering (D∞h → C∞v, C∞v, Cs) occurs when the two axial bonds within the uranyl moiety are not equal in length or through significant bending (>5°) of the linear dioxo bond [52,53]. Decreasing the symmetry of the uranyl moiety should result in the activation of all three fundamental modes in IR and Raman spectra.

Fig. 1.

Vibrational modes for the [UO2]2+ cation and frequencies for the [UO2(H2O)5]2+ species. The uranyl pentaqua species in the D∞h point group typically serves as a benchmark for determining a red of blue shift of these uranyl vibrational modes.

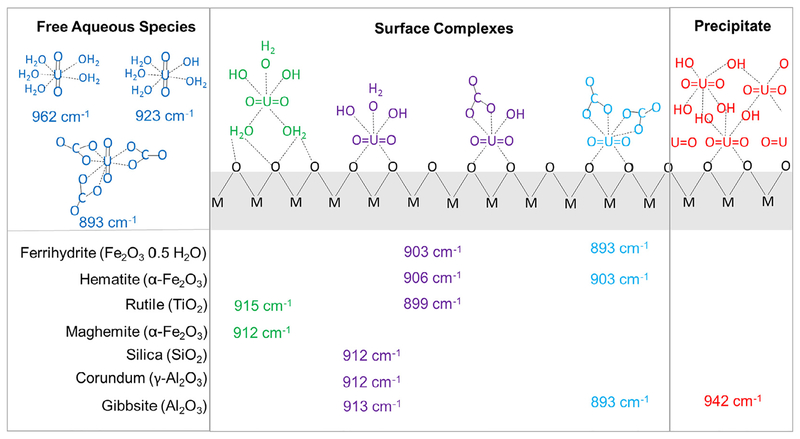

The symmetric and asymmetric stretching modes are both informative and sensitive to coordinating ligands and structure (e.g., mono-, bi-, or tridentate chelation). This occurs because the uranyl bond is weakened by additional coordination in the equatorial plane [54]. Perturbation of the uranyl bond can be explained by either the presence of strong electron donating ligands occupying the equatorial coordination sites or destabilization from purely electrostatic interactions [55]. Weakening of the uranyl bond results in bond elongation, causing the uranyl vibrational frequency to red-shift from the widely-used comparative standard, the pentahydrate species . The symmetric and asymmetric stretching bands for is commonly observed at 870 and 962 cm−1, respectively [48]. This leads to a typical spectral window for U(VI) compounds ranging from 900 to 750 cm−1 for Raman and 980–830 cm−1 for IR spectroscopy.

The Raman-active bands can be fit to a Gaussian function, and the full width at half-maximum (Γ) of these bands is typically between 13 and 15 cm−1 [48]. Vibrational band frequencies are observed for monomeric, dimeric, and trimeric hydrolysis products. For instance, a ~20–30 cm−1 shift in vibrational frequency of the symmetric stretch has been reported as oligomeric species are generated by hydrolysis [56]. This shift is also accompanied by slight broadening of the bands (ΔΓ = 5 cm−1) due to the formation of these larger soluble clusters [48].

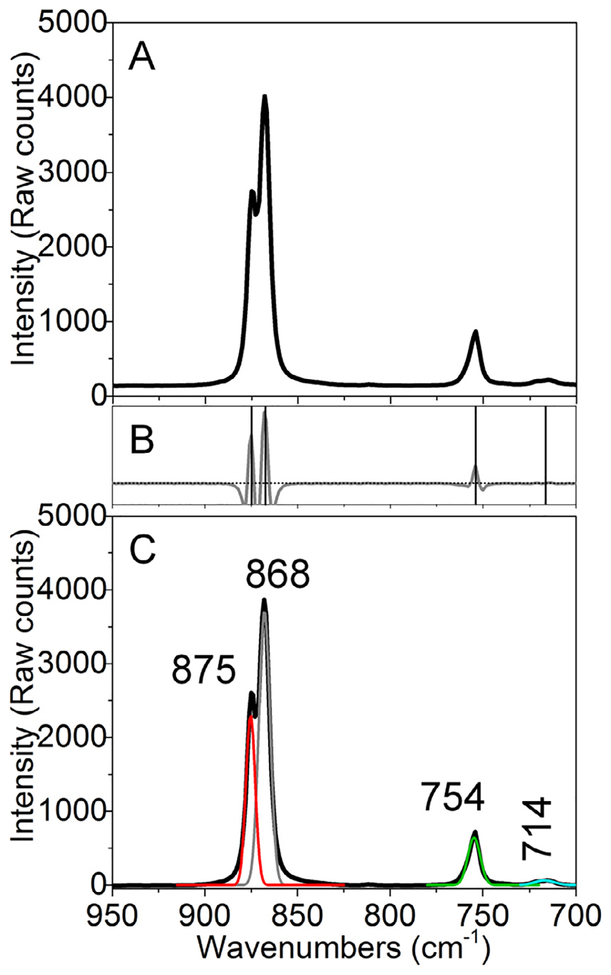

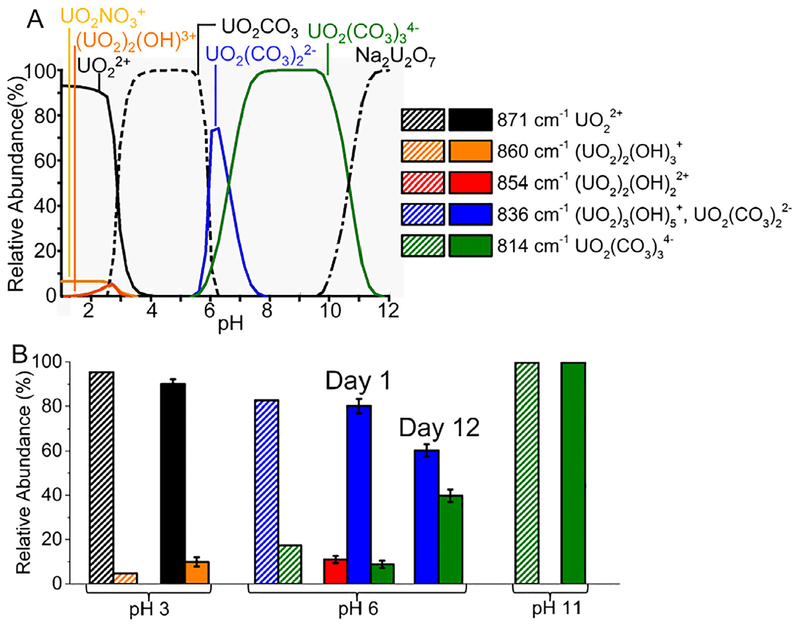

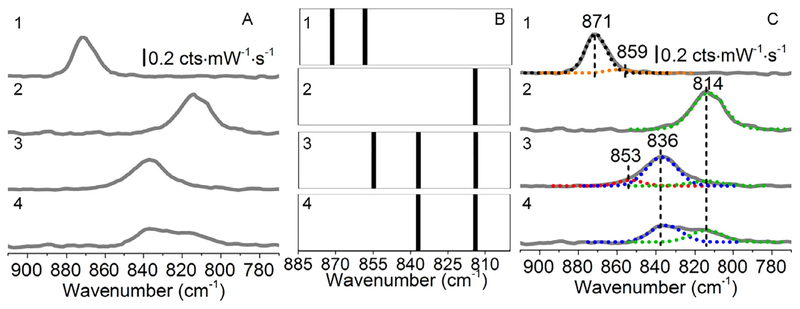

An example of Raman data analysis for speciation determination is demonstrated in Fig. 2. Here, Raman spectra of uranyl nitrate crystals (used as received from International Bio-Analytical Industries, Inc. Lot #55971) were collected using a 785 nm laser to reduce the effects of elastic scattering and fluorescence interference on the background in the uranyl window (950–700 cm−1). Raw spectral data are shown in panel B. Next, inverse second derivative spectra are generated and plotted so that approximate vibrational band centers can be noted. Bands were considered significant if band widths were greater than 15 cm−1 and larger than 5% of the noise. As shown, four significant features were noted and were centered at 874, 865, 754, and 715 cm−1. These vibrational band centers with ±3 cm−1 windows and 15–45 cm−1 widths were used for subsequent fitting using Lorentzian functions. In so doing, four bands were identified at 875 (v1 U=O; uranyl nitrate dihydrate) [57], 868 (ν1 U=O; uranyl nitrate hexahydrate) [58], 754 (ν3 (A1), NO), and 714 (ν5 (B1), NO) cm−1 [59]. Note that the m1 band for the dehydrate material is slightly blue-shifted compared to the original pentaqua uranyl species whereas the hexahydrate compound exhibits a 2 cm−1 red-shift compared to the same benchmark complex. The splitting of the band associated with the uranyl symmetric stretch, also allowed us to determine that the compound was composed of a biphasic mixture with differences in hydration state.

Fig. 2.

Raman analysis of the uranyl window for uranyl nitrate (solid) including (A) raw, (B) -second derivative and barcode, and (C) analyzed Raman data.

2.3. Vibrational spectroscopy of U(V)

While U(V) complexes are quite unstable, the presence of this moiety in solution or solid state can be detected using vibrational spectroscopy. Pentavalent uranium also forms the uranyl cation, but the charge is reduced to [U(V)O2]+. Additional coordination about the equatorial plane leads to a similar coordination environment as with U(VI) species. The major difference with the two valence states is the elongation of the U(V)=O bond to 1.808–1.916 Å and a red shift in the vibrational modes [60]. The oxo groups of the species are more reactive than the hexavalent moiety and interact with other cations or actinyl groups [61]. This interaction should promote elongation of one of the uranyl bonds, resulting in lower molecular symmetry. The consequence of asymmetric uranyl bonds within the vibrational spectra is similar to what is reported for U(VI) species, where all three fundamental modes can be activated in both the IR and Raman spectra [39].

3. Chemical and structural elucidation of uranium solid-state compounds

Vibrational spectroscopy has been used for over 80 years to identify and understand the structural features of simple inorganic U salts and mineral phases [62]. This is particularly true for mineral phases, and we would be remiss if we did not acknowledge the amazing body of literature provided by Ray L. Frost, Jiri Cejka, and their research groups/colleagues. In the last 10 years, spectroscopic analysis of uranyl hybrid materials significantly expanded due to an interest in understanding the uranyl moiety bond strength and providing additional characterization to enhance the structural description of novel compounds. In the next section, we analyze the spectral signals for uranium compounds with extended topologies and mineral phases before exploring uranium coordination compounds and hybrid materials. In addition, we use a subset of well-characterized compounds to provide updated metrics for the analysis of bond lengths and predicted spectroscopic signals.

3.1. Mineral phases and inorganic uranium compounds with extended topologies

Some natural mineral specimens contain chemical and structural variations based upon the specific geologic conditions that influence vibrational band intensities and frequencies. To simplify the discussion of these compounds, we focus on the major bands associated with the uranyl cation, and the reader should refer to the primary literature to evaluate subtle spectral differences in these data. Relationships between vibrational band frequencies and bond lengths, which are based upon the empirical formula derived from Bartlett and Cooney [63] are discussed herein. We summarize the major vibrational modes within the text and provide detailed in Table 2. We would like to note that the values included in the tables are those directly reported in the literature and not our own interpretation. In addition, the Raman bands are emphasized in this section because of difficulties in identifying the ν3 mode in IR spectra due to significant band overlap from interfering species. When possible, we obtained information on the asymmetric stretch and included those values in the tables.

Table 2.

Vibrational modes for solid state inorganic compounds and mineral phases for hexavalent uranium compounds.

| Compound (Mineral Name) | ν1 (cm−1) | ν3 (cm−1) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxides, Oxyhydroxides, Peroxides, Halides | |||

| (Ca,U(VI))O4 (Vorlanite) | 683 | [84] | |

| [(UO2)8O2(OH)12]·12H2O (schoepite) | 838 | [86] | |

| K2[(UO2)3O2(OH)3]2·7H2O (compreignacite) | 848, 824 | [273] | |

| 831 | [87] | ||

| Ca[(UO2)6O4(OH)6]·8H2O (becquerelite) | 838, 813 | [86] | |

| 829, 796 | 948, 872 | [87] | |

| Ba[(UO2)6O4(OH)6](billietite) | 830 | [86] | |

| Pb[(UO2)10O6(OH)11](vandendriesscheite)) | 852, 840 | [86] | |

| Pb3+x(H2O)[(UO2)4O4+x(OH)3x]2 (curite) | 803, 791 | 912, 876 | [86,88] |

| Cu[UO2(OH)4] (vandenbrandeite) | 805 | 897 | [89] |

| K2Ca[(UO2)6O6(OH)4]·6H2O (rameauite) | 813 | [274] | |

| KPb[(UO2)7O5(OH)7]·8H2O (gauthierite) | 833 | 915 | [275] |

| [N(C2H5)4]2[(UO2)4(OH2)3F10] | 845 | 927 | [276] |

| [(UO2)(O2)(H2O)2]·2H2O (studtite) | 831 | [95] | |

| UO2F2 | 867 | 915 | [100] |

| UO2Cl2 | 871 | 960 | [101] |

| Carbonates | |||

| Ca2[UO2(CO3)3]·11H2O (liebigite) | 822 | [277] | |

| Ca2[UO2(CO3)3]·11H2O (liebigite) | 829 | 906 | [87] |

| Ca2 [UO2(CO3)3]·10H2O (synthetic) | 826 | [278] | |

| Mg2 [UO2(CO3)3]·18H2O (bayleyite) | 822 | [278] | |

| Na4[(UO2(CO3)3] (cejkaite) | 805 | [279] | |

| Na4[(UO2(CO3)3] (synthetic) | 810, 816 | [279] | |

| Na2Ca(UO2)(CO3)3·6H2O (andersonite) | 806, 832 | 899, 913 | [87] |

| 832 | 898 | [253] | |

| K3Na(UO2)(CO3)3·H2O (grimselite) | 815 | 876 | [87] |

| Sr2[UO2(CO3)3]·8H2O | 812 | [278] | |

| Ba2[UO2(CO3)3]·6H2O | 818 | [278] | |

| K4UO2(CO3)3 | 806 | [280] | |

| Pb2(UO2)(CO3)3 (Widenmannite) | 849 | 926 | [281] |

| (UO2CO3) (Rutherfordine) | 886 | 956 | [282,283] |

| 886 | 932 | [284] | |

| NaCa3(UO2)(CO3)3(SO4)F·10H2O (schrockingerite) | 817 | 898 | [285] |

| Ca[(UO2)(CO3)2(H2O)2]·3H2O (zellerite) | 834 | 899 | [286] |

| Ca2Cu[(UO2)(CO3)3](CO3)·6H2O (voglite) | 836 | 898 | [287] |

| Y2(UO2)4(CO3)3(OH)8·10–11H2O (kamotoite-Y) | 814.7 | 911 | [288] |

| CaU5+(UO2)2(CO3)O4(OH)(H2O)7 (Wyarite) | 853, 837 | [124] | |

| Sulfate and Selenate | |||

| UO2SO4 2.5H2O | 863,853 | 952, 938 | [289] |

| UO2SO4 3.5H2O | 865 | [290] | |

| (H3O)2[(UO2)2(SO4)3(H2O)]·7H2O | 930 | [291] | |

| (H3O)2[(UO2)2(SO4)3(H2O)]·4H2O | 918, 928, 935 | [291] | |

| [(UO2)6(SO4)O2(OH)6(H2O)6](H2O)8 (uranopilite) | 843, 835, 819 | 941, 929, 910 | [292,293] |

| (UO2)8(SO4)(OH)14·13H2O (jachymovite) | 839, 828, 807, 800 | 902, 923 | [294] |

| K0.6(H3O)0.4[(UO2)6(SO4)3(OH)7]·8H2O (zippeite) | 849, 838, 826, 814 | 911, 873 | [295] |

| Na4[(UO2)6(SO4)3(OH)10]·4H2O (Na zippeite) | 840, 841, 833, 823 | 880, 912 | [296] |

| Na5(UO2)8(SO4)4O5(OH)3·8H2O (natrozippeite) | 840 | [109] | |

| Cu(UO2)2(OH)2(SO4)2·8H2O(johannite) | 811 | [297] | |

| 836 | [109] | ||

| Cu6.5[(UO2)4O4(SO4)2]2(OH)5·25H2O (pseudojohannite) | 810,805 | [298] | |

| Fe(UO2)(SO4)2(H2O)11 (leydetite) | 858, 851, 846, 843, 836, 828 | 937, 930 | [299] |

| Fe[(UO2)2(SO4)2(OH)2](H2O)7 (deliensite) | 838 | 933 | [300] |

| (UO2)8(SO4)(OH)14·13H2O (jachymovite) | 839, 828, 807, 800 | 902, 923 | [294] |

| Na5(UO2)(SO4)3(SO3OH)(H2O)(meisserite) | 847 | [301] | |

| Na7(UO2)(SO4)4Cl(H2O)2 (bluelizardite) | 854,848 | [302] | |

| K(UO2)(SO4)(OH)(H2O) (adolfpateraite) | 843 | 890 | [303] |

| Na6[(UO2)(SO4)4](H2O)4 | 860, 845, 830, 805 | [304] | |

| Fe(UO2)(SO4)2·5H2O (rietveldite) | 862 | 924 | [305] |

| [(UO2)(SO4)(H2O)2]2·H2O (shumwayite) | 865,850 | 951, 927 | [306] |

| (UO2)3(SeO3)2(OH)2·5H2O(haynesite) | 811, 800 | 905, 862 | [307,308] |

| Cu[(UO2)3(SeO3)2O2]·8H2O (marthozite) | 812 | 863 | [309] |

| Cu4UO2(SeO3)2(OH)6·H2O(derriksite) | 788 | 859 | [310] |

| Pb2Cu5(UO2)2(SeO3)6(OH)6·2H2O (demesmaekerite) | 822 | 878 | [311] |

| Ba[(UO2)3O2(SeO3)2](H2O)3 (guilleminite) | 831 | 912 | [312] |

| (Y1.98Dy0.24)2.22H0.34[(UO2)8O88O7OH(SO4)4](OH)(H2O)26 (sejkoraite-Y) | 829 | 911 | [313] |

| Phosphate and Arsenate | |||

| UO2(H2PO2)2·H2O | 830 | 909 | [314] |

| UO2(H2PO2)2·H3PO2 | 830 | 912 | [314] |

| (H3O)(UO2)PO4·4.5H2O | 842 | [315] | |

| K0.9(H3O)0.1(UO2)PO4·2.5H2O | 826 | [315] | |

| K0.4(H3O)0.6(UO2)PO4·3H2O | 840 | [315] | |

| Cs3(UO2)2(PO4)O2 | 885, 855, 838, 805 | [316] | |

| Ca(UO2)2(PO4)2·11H2O (autinite) | 830 | [108] | |

| KCa(H3O)3(UO2)7(PO4)4O4·8H2O] (phosphuranylite) | 827 | [108] | |

| 832 | 894 | [115] | |

| Ca(UO2)3(PO4)2(OH)2·6H2O (phosphuranylite) | 801 | [109] | |

| Ca2(UO2)3O2(PO4)2·7H2O (phurcalite) | 810 | 874 | [317] |

| [Mg(UO2PO4)2·10H2O] (saleeite) | 837 | 901 | [108] |

| [CaCu(UO2)(PO4)2·4H2O] (ulrichite) | 812 | 880 | [108] |

| [Cu(UO2PO4)2·8H2O] (metatorbernite) | 826 | 906 | [108] |

| 813 | 876–902 | ||

| 840 | |||

| (H3O)0.4Cu0.8(UO2)2(PO4)2·7.6H2O (metatorbernite) | 822 | 895 | [318] |

| Cu(UO2)2(PO4)2·12H2O (torbernite) | 825 | [109] | |

| [(Ba)2(UO2)3(PO4)2(OH)4·8H2O] (bergenite) | 810,798 | [319] | |

| (H3O)Al(UO2)4(PO4)4·15H2O (sabugalite) | 850, 836, 826, 810 | [110] | |

| Al[(UO2)2(PO4)2](OH)·8H2O (threadgoldite) | 827 | [320] | |

| Pb2(UO2)(PO4)2·n H2O (parsonsite) | 807, 796 | [321] | |

| Pb3[H(UO2)3O2(PO4)2]2·12H2O(dewindtite) | 831, 823, 818, 808, 795 | [322] | |

| Pb2[(UO2)3O2(PO4)2]·5H2O(dumontite) | 815,800, 780 | [323] | |

| (UO2)Bi4O4(PO4)2·2H2O (phosphowalpurgite) | 885 | [324] | |

| Nd[(UO2)3O(OH)(PO4)2]·6H2O (francoisite-Nd) | 830 | 934 | [325] |

| U(OH)4[(UO2)3(PO4)2(OH)2]·4H2O (vanmeersscheite) | 860 | 884 | [326] |

| (Na2,Ca)[(UO2)(AsO4)]2·5H2O (natrouranospinite) | 816, 810 | 917 | [327] |

| Ca[(UO2)(AsO4)]2·8H2O (metauranospinite) | 815, 806 | 904, 893 | [328] |

| Ca(UO2)[(UO2)3(AsO4)2(OH)2]·(OH)2·6H2O (arsenouranylite) | 795, 787 | [326] | |

| Mg(UO2)2(AsO4)2·10H2O (novacekite) | 817 | [109] | |

| Cu(UO2)2(AsO4)2·12H2O (zeunerite) | 821 | [109] | |

| Cs2[(UO2)(As2O7)] | 832 | [329] | |

| α-Cs[(UO2)(HAs2O7)] | 834 | [329] | |

| β-Cs[(UO2)(HAs2O7)] | 820 | [329] | |

| Cs[(UO2)(HAs2O7)]·0.17H2O | 809 | 896 | [329] |

| Ni(UO2)2(AsO4)2·8H2O (metarauchite) | 817 | 947 | [330] |

| (UO2)Bi4O4(AsO4)2·2H2O (walpurgite) | 790, 770 | 888 | [331] |

| (zn0.72Fe0.10Mg0.06Al0.05)(UO2)2[(AsO4)1.5(PO4)0.5]2·8.43H2O (metalodevite) | 819 | 891 | [331] |

| Silicates | |||

| (UO2)2SiO4·2H2O (soddyite) | 832, 828 | [233] | |

| 830 | 897 | [332] | |

| 828, 809, 802 | 904, 910, 900 | [333,334] | |

| Na[UO2SiO3(OH)]·0.5H2O (sodium boltwoodite) | 848 | [335] | |

| K[UO2SiO3(OH)]·H2O (boltwoodite) | 841 | [335] | |

| (K,Na)[(UO2)(SiO3OH)]·1.5H2O (boltwoodite) | 799, 796, 786 | 853 | [336] |

| K2[(UO2)2(Si5O13)]·H2O (weeksite) | 814, 810, 800 | 916, 903 | [333,334] |

| Ca(UO2)2(SiO3OH)2·5H2O (uranophane) | 799, 796, 799 | 856, 878, 852 | [337] |

| 855 | [335] | ||

| 800 | [338] | ||

| 800 | [109] | ||

| 798 | [233] | ||

| Mg(UO2)2(SiO3OH)2·5H2O (sklodowskite) | 827, 801, 777 | 854, 821 | [336] |

| Cu(UO2)2(SiO3OH)2·6H2O (cuprosklodowskite) | 787 | 871 | [336] |

| 792 | [109] | ||

| PbUO2SiO4·H2O (kasolite) | 759 | 904 | [336] |

| 768 | [109] | ||

| Ca[(UO2)2(Si5O12(OH)2](H2O)3 (haiweeite) | 808, 800 | 909, 877 | [333,334] |

| Iodates and Tellurates | |||

| UO2(IO3)2(H2O)·2HIO3 | 902 | [339] | |

| Na2[UO2(IO3)4(H2O)] | 903 | [340] | |

| K2[(UO2)2(VO)2(IO6)2O]·H2O | 862 | 982 | [341] |

| K2[UO2(MoO4)(IO3)2] | 909 | [342] | |

| K[UO2Te2O5(OH)] | 860 | [343] | |

| Tl3(UO2)2[Te2O5(OH)](Ie2O6)·2H2O | 863 | [343] | |

| α-Tl2[UO2(TeO3)2] | 843 | [343] | |

| Sr3[UO2(TeO3)2](TeO3)2 | 847 | [343] | |

| [UO2TeO3] (schmitterite) | 823 | 937, 882 | [344] |

| PbUO2(TeO3)2 (moctezumite) | 826 | 837 | [345] |

| Tungstates, Vanadates, and Chromates | |||

| Cs4[(UO2)4(WO5)(W2O8)O2] | 765, 782 | [118] | |

| Cs4[(UO2)7(WO5)3O3] | 871, 828, 786, 766 | [118] | |

| Na8[TeW9O33]·19·.5H2O | 796 | [346] | |

| (NH4)14[(UO2)2(H2O)2(SbW9O33)2]·24H2O | 804 | [346] | |

| Pb2(UO2)(V2O8)·5H2O (carnotite) | 837, 826 | 900, 860 | [347] |

| K2(UO2)(V2O8)·3H2O (curienite) | 825 | [347] | |

| Ba,Pb(UO2)(V2O8)·5H2O (francevillite) | 828 | [347] | |

| Ca(UO2)(V2Os)·9H2O (Tyuyamunite) | 829 | [347] | |

| Ca(UO2)(V2O8)·3H2O (metatyuyamunite) | 824, 793 | [347] | |

| K5(UO2)4(SO4)4(VO5)·4H2O (mathesiusite) | 830 | 888, 896 | [348] |

| Rb[UO2(CrO4)(IO3)(H2O)] | 914 | [342] | |

| K2[UO2(CrO4)(IO3)2] | 902 | [342] | |

| Rb2[UO2(CrO4)(IO3)2] | 903 | [342] | |

| Cs2[UO2(CrO4)(IO3)2] | 880 | [342] |

3.1.1. Uranium oxide, peroxides, hydroxides, and halides

The most abundant and economically important uranium mineral is uraninite (UO2). This phase is always partially oxidized in environmental systems, which leads to the formation of varying stoichiometries (UO2+x, U4O9, U3O7, and U3O8) that occur independently or as a corrosion rind on solid materials [64]. For stoichiometric UO2 with the defect-free fluorite structure, group theory predicts one strong Raman (T2g) and one weak IR active band (340 cm−1, T1u). A narrow Raman band is located at 445 cm−1, whereas a broad IR mode is centered at ~340 cm−1 and overlaps with another band at ~470 cm−1 [65–68]. A second weak band at 1150 cm−1 also appears in Raman spectra and was previously assigned by Livneh and Sterer as a second-order longitudinal optical (LO) phonon mode [69]. Hyperstoichiometric amounts of oxygen in uranium dioxide (UO2.03) leads to the appearance of a broad asymmetric feature with a maximum centered at 560 cm−1 and shoulder at 630 cm−1, corresponding to defect induced degenerate LO modes and anion sublattice distortions, respectively [49,70]. Increasing the O content leads to further broadening and a blue-shift of the T2g band, a decrease in the LO band intensity, an increased in the intensity of the peak at 630 cm−1, and changes in the relative intensity at 560 cm−1 [49].

Elorrieta et al. [49] utilized Raman spectroscopy to quantitatively characterize the hyperstochiometric material by closely investigating the anion sublattice distortion at 630 cm−1. The value for x within UO2+x can be quantified using one of the following two equations using the intensities of the modes at 630 and 445 cm−1 (I630 and I445, respectively):

It is important to note that these equations are valid for the 632.8 nm excitation wavelength because other excitation wavelengths may lead to selective resonant enhancements or high fluorescent backgrounds both of which prohibit quantitative analysis [49].

Partial oxidation to U(IV,V)3O7 (also reported as UO2.3 or tetrag onal UO2+x) and U(V,VI)3O8 results in the appearance of new Raman bands that have been previously used to characterize corrosion of UO2 fuel pellets [71]. Group theory for D4h point symmetry predicts 18 phonon branches for the tetragonal U3O7 phase, with nine Raman active and five infrared active modes.[72] Only six of those modes (A1g + 2 B1g + 3 Eg) were observed experimentally for U3O7 and centered at 630, 155, and ~470 cm−1, respectively [72]. The ingrowth of the B1g and Eg bands, therefore, are used to determine structural transformations from the cubic to tetragonal phase of UO2+x. Formation of orthorhombic U3O8 results in the characteristic A2u combination band at 750 cm−1 [73,74]. Other bands associated with U3O8 include the A1g (335 cm−1), A1g (410 cm−1), and the A1g (475 cm−1) stretching bands. Precise analysis of these bands during aging of fuel pellets provided growth rates of secondary alteration phases, formation of lattice defects, and inhomogeneities to due irradiation of the material [67,68,72,75–77].

Full oxidation to U(VI) leads to the formation of the uranyl moiety and related spectroscopic signals for the oxide phases. The simplest U(VI) oxide is UO3, which can form at least seven different crystalline forms depending on the identity of the starting material [78,79]. Of the seven polymorphs, γ-UO3 is the most studied, with major Raman modes located at 767, 484, and 399 cm−1 [79]. DFT calculations combined with experimental results provide structural details of the gamma phase and indicate that there are two crystallographically unique U atoms [78,80]. U1 is observed in a square bipyramidal coordination geometry with a uranyl bond length of 1.87 Å. The coordination geometry of the U2 site is an unusual dodecahedron with axial bond lengths of 1.78 Å and an O=U=O bond angle of 174.6°. Using the relationship established by Barlett and Cooney [63], the calculated bond length associated with the Raman mode at 767 cm−1 is 1.85 Å, which agrees well with the reported values [80]. Other vibrational modes have not been specifically assigned, but likely arise from uranyl stretching modes. Diuranate compounds (X2U2O7), particularly sodium and ammonium forms, are also important U(VI) oxides because they are precipitated as an intermediate product during the production of yellowcake and nuclear fuel pellets [81]. The main spectroscopic band associated with uranyl in Na2U2O7 is located between 789 and 778 cm−1, whereas the NH4 form ((UO2(OH)2−x(O)(NH4)x)·yH2O) exhibits bands within a larger spectral window (841–804 cm−1) due to hydrolysis and variability in hydration that occurs between synthetic batches [82,83]. Only one other U(VI) oxide phase, the rare mineral Vorlanite (Ca,U(VI)O4), has been reported in the literature. The major band associated with the uranium cation is observed at 683 cm−1, which corresponds to octahedrally coordinated U(VI) with a bond length of 2.33 Å [84].

Hydrolysis of uranium oxide materials occurs in the presence of water and leads to a range of uranyl oxyhydroxide phases in a complex matrix such as groundwater. Schoepite [(UO2)8O2(OH)12]-·12 H2O occurs in solutions at near neutral pH and low ionic strength values [85]. The ν1 mode for this phase occurs at 839 cm−1 with a distinct shoulder at 855 cm−1 and a weak band at 802 cm−1 [86]. With increasing ionic strength, other common uranyl oxyhydroxide minerals form, with the overall general formula of Mn[(UO2)xOy(OH)z](H2O)m, where M = K+, Ca2+, Pb2+, Ba2+, and Sr2+ [85]. The spectroscopic envelope for most of the oxyhydroxide minerals are observed from 855 to 830 cm−1, with a handful of weak modes appearing at lower wavenumbers [86,87]. Curite (Pb3+x(H2O)[(UO2)4O4+x(OH)3x]2) and vandenbrandeite (Cu[UO2 (OH)4]) are notable exceptions because the uranyl bands are significantly red shifted to ~800–770 cm−1 [86,88,89]. This difference in vibrational frequency arises from structural variations within the mineral sheet topologies. The curite sheet topology is quite different than that of the other uranyl oxyhydroxides, such that it contains U1 in a distorted square bipyramid [90]. Vandenbrandeite is also unique as it contains Cu2+ cations bonded to oxo atoms of the neighboring uranyl pentagonal bipyramids [90,91]. In the case of curite, this leads to an elongation of the uranyl bonds (1.79(2)–1.89(2) Å), which induces a significant red-shift in the vibrational band compared to the other oxyhydroxide phase [86,90]. For vandenbrandeite, the uranyl bond distances are closer to the average value (1.77 Å), thus additional investigations are needed to clarify the perturbation of the uranyl bond [91].

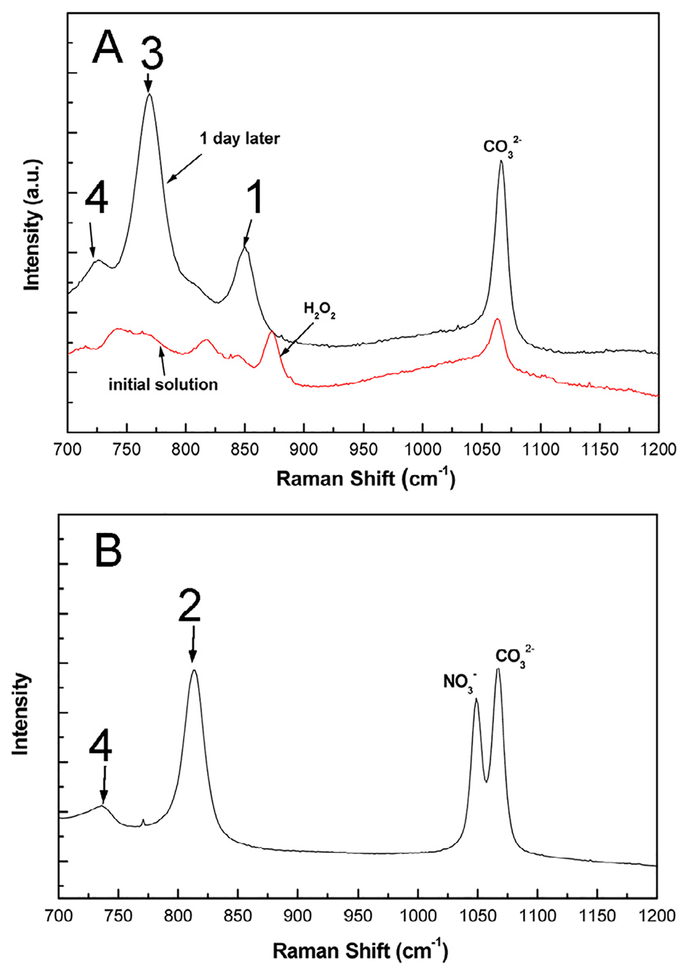

The uranyl mineral, studtite, is the only naturally occurring peroxide-bearing phase and widely occurs as a secondary corrosion product of urananite ores and nuclear fuel rods [92,93]. The material contains a chain topology that propagates through edge sharing peroxide bridges [94]. The Raman spectra contains a v1 uranyl band located at 831 cm−1 and a secondary v1 (O=O) stretching mode at 870 cm−1 [95]. Both studtite and the dehydrated form (metastudtite [UO2(O2)(H2O)2]) have been identified as a secondary alteration phase formed due to the alpha radiolysis of water using Raman spectroscopy as the main surface characterization technique [76,77,96,97].

While there are several uranyl halide phases reported in the literature, significant spectral data are only available for UO2F2 and UO2Cl2. Structural features of the fluoride compound was first established by Zachariasen [98] and then refined with neutron diffraction by Atoji and McDermott [99]. The structure contains sheets of uranyl hexagonal bipyramids, with six edge sharing F atoms located in the equatorial plane and an experimental UAO bond length of 1.74(2) Å. Theoretical studies predict a Raman band at 915 cm−1 and a calculated bond length of 1.71 Å. Hydration of the uranyl fluoride compound induces a red shift in the m1 mode to 867 cm−1, which agrees well with the calculated bond length of 1.75 Å [100]. Bullock spectroscopically characterized UO2Cl2, denoting the ν1 at 871 cm−1 and ν3 at 960 cm−1 [101]. The uranyl bond distance reported for the chloride compound is 1.70 Å, which is lower than expected based upon the spectroscopic signal (1.74 Å) [102].

3.1.2. Uranium compounds and minerals containing oxyanions

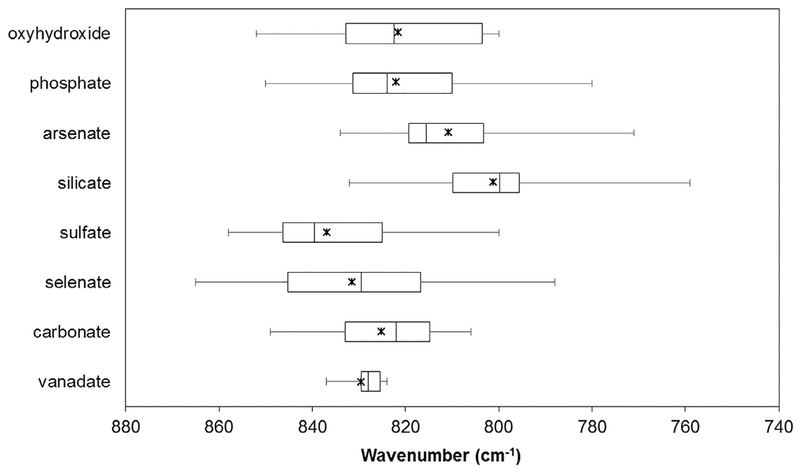

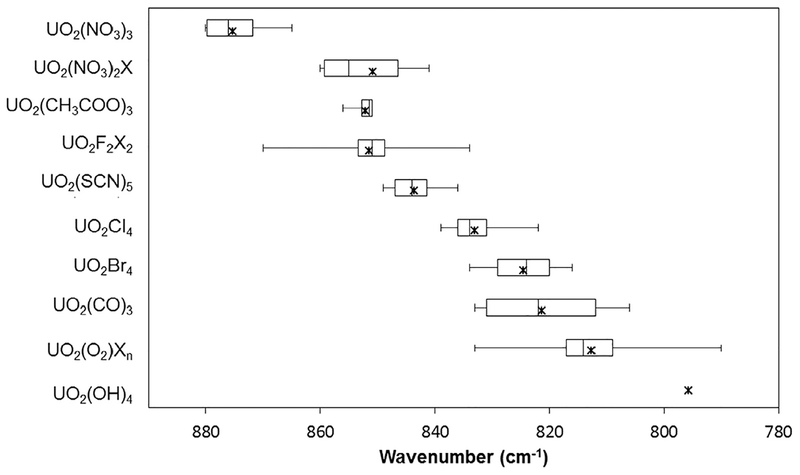

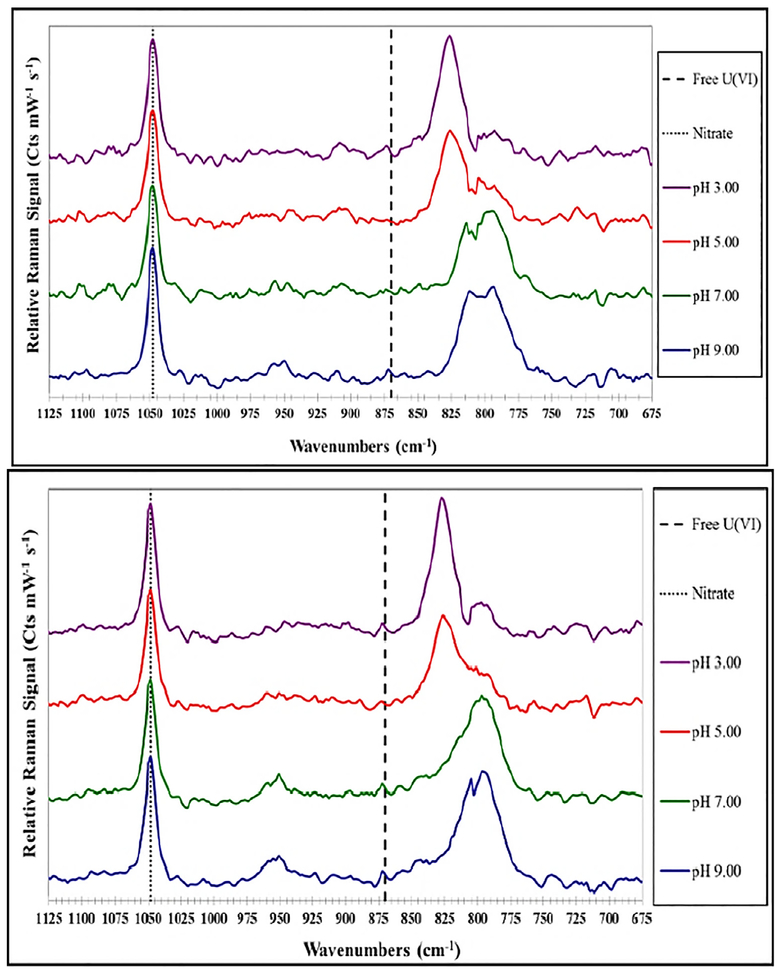

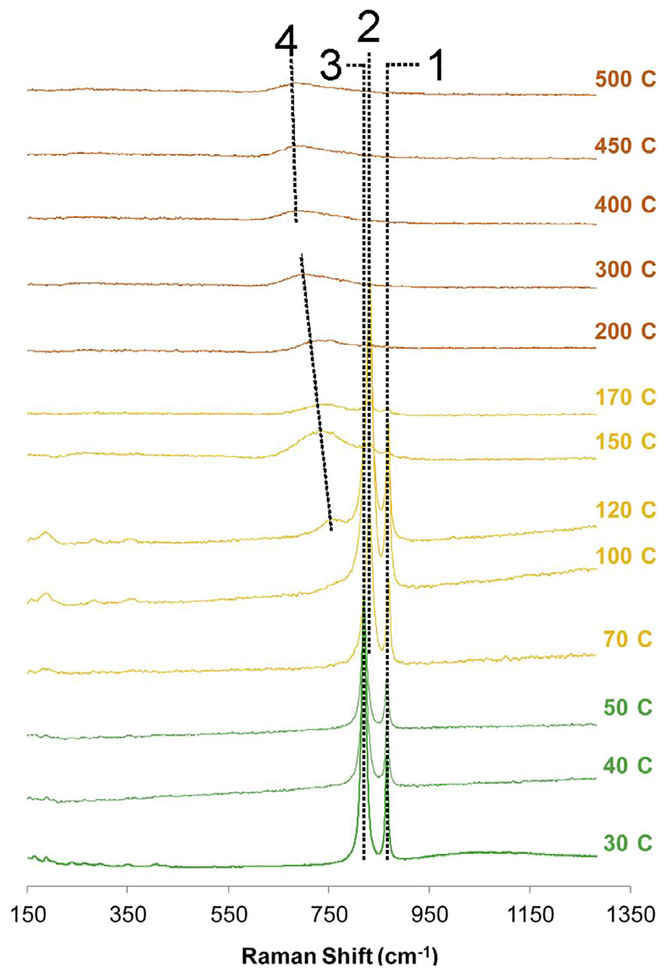

The chemical complexity of oxyanion-containing U(VI) compounds and mineral phases leads to a wide spectral envelope for the vibrational bands associated with the uranyl moiety. Fig. 3 provides the averaged ν1 vibrational band frequencies (stars) as well as the range of values for the various oxyanion species. We have chosen to present these published results as box and whisker plots to emphasize the variation in values reported. In particular, these plots visually depict the distribution of results including the mean (x), median (middle vertical line), 25th and 75th quartiles (3rd and 1st vertical lines, respectively), as well as the minimum and maximum values (ends of error bars). Average values are observed between 840 and 800 cm−1 with ranges extending from 870 to 760 cm−1. This large range likely arises because of the complex nature of the extended structural topologies and subtle variations in the coordination environment about the uranyl cation within different compounds and mineral phases. Complexity is enhanced from symmetry lowering within the solid state compounds upon activating the vibrational and splitting degenerate modes. Despite this, there are subtle trends that can be observed. For instance, sul-fate tends to red shift the vibrational bands less significantly than other oxyanions, and selenate exhibits the largest range of vibrational frequencies (865–788 cm−1).

Fig. 3.

Box and whisker plot that describes the median (solid vertical line within box), range (whiskers), and mean (x) values of symmetric stretching frequencies for uranyl mineral phases and inorganic compounds with extended topologies. Values are from the literature as summarized in Table 2.

Similarities within structural topology can also be used to understand trends in uranyl vibrational frequencies. Uranyl phosphates, which are a well-studied group of compounds due to their relative abundance as a secondary mineral phase in geologic systems and waste products [103,104], contain the two major 2-D structural topologies autunite or phosphoruranylite sheets [12]. The autunite sheet contains uranyl square bipyramids that share vertices to phosphate tetrahedral and account for 17+ different compounds. Within these compounds, the autunite sheet is retained while the identity of the charge balancing cations varies [105,106]. Phosphoruranylite sheets, which are slightly more complex, contain U(VI) with different coordination environments (square, pentagonal, and hexagonal bipyramids) leading to chain structures linked into 2-D sheets through phosphate tetrahedral [107]. This topology accounts for 11 different compounds with variability in the interstitial charge balancing cations and phosphate tetrahedra orientation. While these two classes of uranyl phosphates contain similar chemical components, both their structural complexity and vibrational spectra are unique.

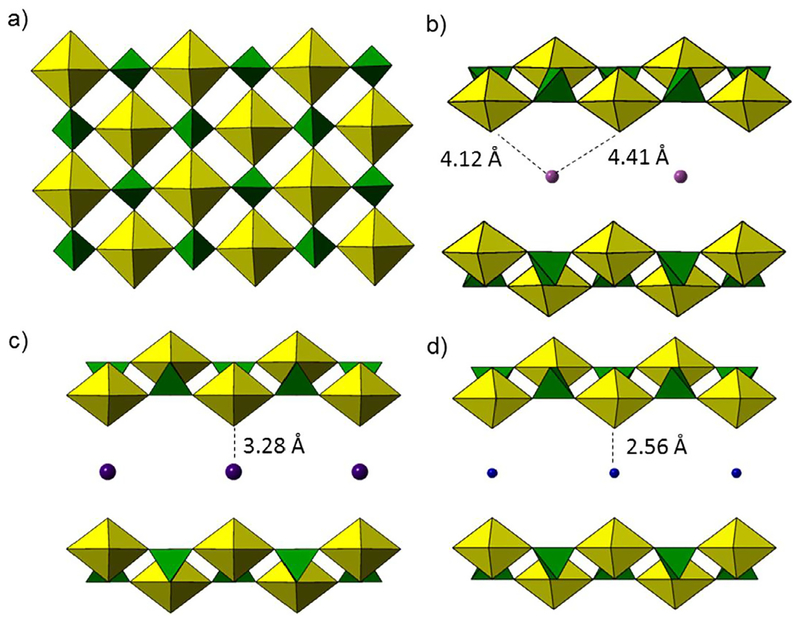

A first look at the Raman spectra for the autunite family of minerals reveals a major band between 837 and 825 cm−1 that was previously identified as the uranyl moiety [108–110]. Ranking the vibrational band centroid (cm−1) by cation identity from largest to smallest reveals the trend Mg(II) > Ca(II) > Al(III) > Cu(II). Further investigation of the interactions between these interstitial cations and the uranyl oxo atoms can provide additional insight in the relative shift in the ν1 band (Fig. 4). For instance, Mg(II) cations interact more with interstitial water molecules present in the interlayer region of saleeite than with uranyl unit because the distances between the uranyl oxo and the Mg cation is 4.12 and 4.14 Å (Fig. 4b) [111]. The large interatomic distance suggests no signifi-cant interaction with the uranyl bond. Replacing Mg(II) with a larger cation (Ca(II) in autunite) leads to a shorter interatomic distance (3.28 Å) between divalent cations and the uranyl oxo atoms. The uranyl symmetric stretch for autunite (830 cm−1) is red-shifted from that observed in saleeite (837 cm−1), suggesting a longer, weaker uranyl bond (Fig. 4c). As the sheet topology is identical between autunite and saleeite, the additional interaction between the interstitial cation likely influences the uranyl bond. Structural characterization of sabugalite has not been reported, but the spectral data suggests that Al(III) exhibits increased electrostatic interactions with the uranyl oxo atoms and a longer uranyl bond length. Inclusion of Cu(II) cations (torbernite) is unique because the d10 transition metal can form 4+2 Jahn-Teller distortions that often involve uranyl oxo groups. Thus, the distance between the uranyl oxo and Cu(II) is shorter (2.55 Å) than with other cations, and the ν1 vibration mode red-shifts (825 cm−1) accordingly (Fig. 4d) [112].

Fig. 4.

a) The autunite sheet topology contains uranyl square bipyramids (yellow polyhedra) connected to phosphate tetrahedra (green polyhedra) through shared vertices. The cation to uranyl oxo atom distance associated with (b) saleeite (Mg(II)), (c) autunite (Ca(II)), and (d) torbernite (Cu(II)) are related to the trends in the uranyl symmetric stretching mode within the Raman spectra.

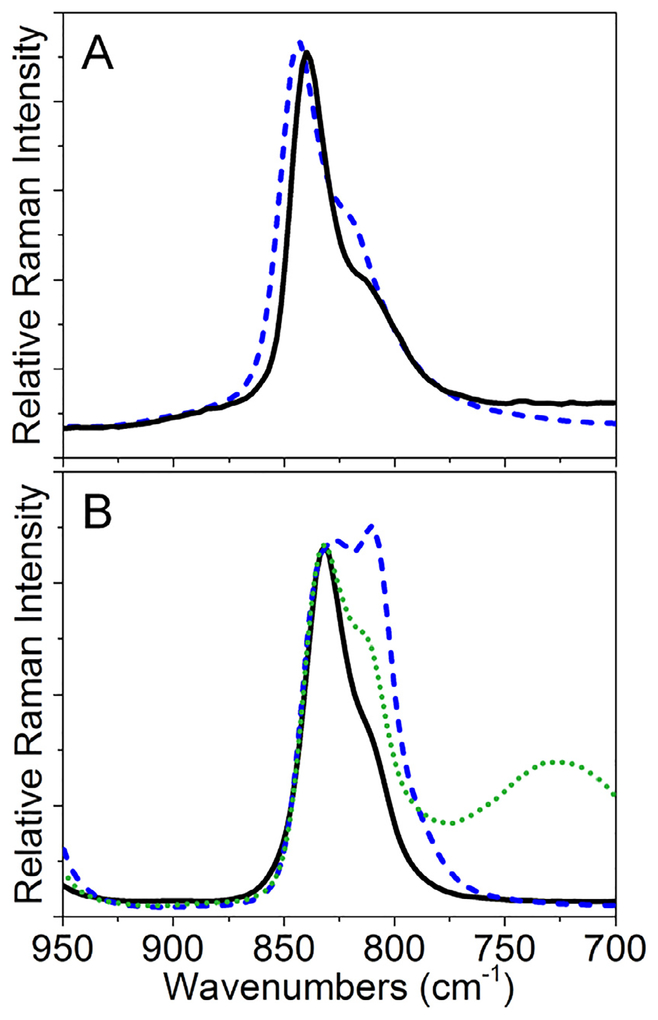

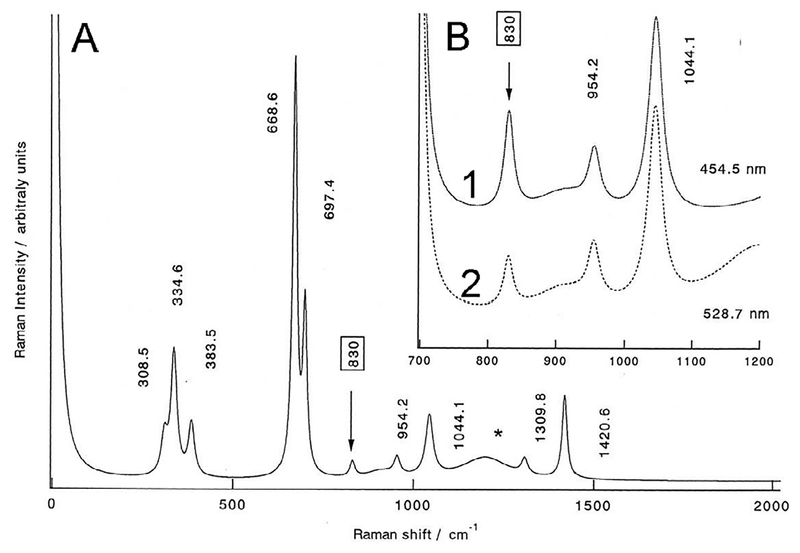

A closer evaluation of the vibrational features and employment of fitting techniques reveals multiple bands in uranyl phosphate minerals that cannot be linked to crystallographically unique U atoms within the lattice. Furthermore, spectral lineshapes varied significantly when evaluating the Raman spectra. To highlight these differences, we obtained raw spectral data for meta-autunite and phosphoruranylite from the RRUFF project [113] and utilized Origin software to fit the ν1 spectral bands. Two and three independently collected spectra were collected for phosphuranylite and autunite, respectively (Fig. 5). Striking similarities and differences are noted for each compound upon normalizing these spectra to the band at ~840 cm−1 to correct for differences in detector efficiency, laser powers, and excitation geometries. First, meta-autunite contains one crystallographically unique U atom, but spectral analysis identifies at least two bands within the uranyl spectral envelope [105,114]. In addition, significant spectral variation is observed in three spectra evaluated from the database.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of solid-state Raman spectra for (A) phosphuranylite (solid black – R130108, dashed blue – R110155) and (B) autunite (solid black – R050612, dashed blue – R060434, dotted green – R060476). Spectral intensities were normalized to the highest energy bands near 840 cm−1.

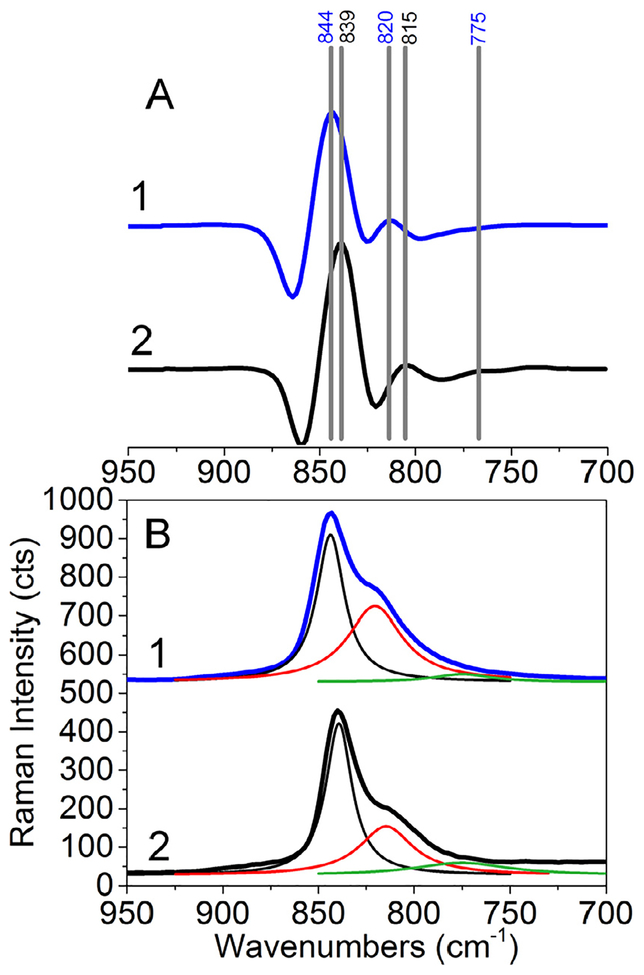

By comparison, phosphuranylite spectra are much more similar. First, the spectra for phosphuranylite possess at least two unique vibrational features – a primary mode centered at ~840 cm−1 and a shoulder at ~820 cm−1. Slight differences are noticed when making spectrum to spectrum comparison. These are highlighted in Fig. 6 where previously discussed second derivative spectral analysis was performed. In both spectra, three significant vibrational features are identified and are centered at 844/839, 820/815, and 775 cm−1. This compound possesses three crystallo-graphically unique U atoms with distinct coordination geometries, and the spectral fitting also finds three bands within the complexes [107]. While clear sample to sample variations are evident, difficulties also arise from lack of spectral analysis so the ν1 uranyl symmetric stretch for uranyl solid-state materials can be identified. This is highlighted again by the phosphuranylite system, where Driscoll et al. [109] found the major vibrational band associated with the v1 stretching vibration to be centered at 801 cm−1, whereas Frost et al. [115] and Faulques et al. [108] reported bands from 845 to 768 or at 827 cm−1, respectively. Driscoll et al. [109] and Faulques et al. [108] did not attempt to fit the bands associated with the uranyl symmetric stretch, but Frost [115] identified four bands within the spectral envelop of interest and the bands exhibited variable peak widths (6–49 cm−1). Moving forward, additional investigations are necessary to identify the nature and variability of the bands that arise from solid-state uranyl compounds.

Fig. 6.

Analysis of phosphuranylite spectral data in the form of Raman (A) – second derivative spectra with barcodes and (B) spectra (+ fitting) for (1) R110155 (blue) and (2) R130108 (black). Data are offset for clarity.

Vibrational analysis provides additional information regarding the unusual coordination environment of uranium within inorganic or mineral phases. In rare cases, a uranyl oxo atom can bond to a neighboring uranyl through the equatorial plane [116]. Historically, this is described as a cation-cation interaction and was previously shown to perturb the uranyl bond [116,117]. Cation-cation interactions cause the uranyl bond engaged in this interaction to weaken and the ν1 band to red shift. Xiao et al. [118] reported Raman spectra of the two uranyl tungstate compounds, Cs4[(UO2)4(WO5)W2O8)O2] and Cs4[(UO2)7(WO5)3O3]. These compounds contain cation-cation interactions in four of the seven crystallographically unique U(VI) polyhedra. Substantial elongation of the uranyl bonds (1.805–1.821 Å) is observed with Cs4[(UO2)4(WO5)W2O8)O2] while there is more variability (1.76–1.99 Å) for Cs4[(UO2)7(WO5)3O3]. Concurrently, the Raman spectra reveal two uranyl vibrational modes [118]. The first is located at 828 cm−1 for unperturbed uranyl bonds and a red shifted mode between ~780 and 760 cm−1 for the uranyl oxo bonds engaged in cation-cation interactions. In addition, the ν3 mode is activated because cation-cation interactions break the D∞h symmetry. Features are weak, but can be observed between 832 and 815 cm−1.

The oxidation state of the inorganic uranium compounds and minerals can be confirmed using Raman spectroscopy. While pentavalent uranium is quite rare in natural settings, hydrothermal reactions conditions in geologic or synthetic systems can result in the formation of mixed valence compounds [119–123]. X-ray diffraction data provides information on elongated bond lengths and reduced bond valence sums that would be indicative of . This oxidation state change is confirmed using Raman spectroscopy via a reduced ν1 vibrational mode energy. The presence of U(V) within inorganic compounds and mineral phases has been suggested twice and in both instances, inconclusively. Wyartite (CaU(V)(U(VI)O2)2(CO3)O4(OH)(H2O)7) was characterized using Raman spectroscopy by Frost [124]. Vibrational features were observed between 850 and 830 cm−1, which are consistent with U(VI), while no bands were observed in the U(V) region (800–750 cm−1). In a second case, K3(U3O6)(Si2O7) and Rb3(U3O6) (Ge2O7) phases were synthesized under hydrothermal conditions [122]. The presence of U(V) was confirmed using XPS, XAS, and magnetic susceptibility; however, the U(V) spectral window was silent upon Raman spectroscopy analysis. These initially conflicting results can be understood by considering the covalency and Raman cross section of the uranyl moiety. Specifically, the U—O bonds within this compound give rise to a distorted octahedron, which potentially limits the covalency of the uranyl moiety thus decreasing the probability of observing this mode.

3.2. U(VI) coordination compounds and hybrid materials

Vibrational spectroscopy has been an important characterization tool for uranyl coordination compounds since the earliest reported spectra of uranyl salts by Conn in 1938 [62]. The evaluation of these simple uranyl coordination compounds using vibrational spectroscopy gave rise to our initial understanding of the uranyl cation and the covalent nature of these bonds. Over the last 10 years, instrument availability and improvements led to widespread use of these methods as characterization tools for more complex uranyl hybrid materials. With increasing use, large data sets for both coordination compounds and uranyl organic materials are available, which provides additional insights into the uranyl bond. In this section, we again focus on the use of Raman spectroscopy because of the difficult interpretation of the IR-active asymmetric stretching mode given the overlap with the fingerprint region of most organic molecules. Additional details can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Vibrational modes for uranyl coordination compounds and metal organic materials.

| Compound | ν1 (cm−1) | ν3 (cm−1) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peroxides | |||

| [Na4K2(UO2)2(O2)(C2O4)4]·6H2O | 822 | [349] | |

| (NH4)3[(UO2)2(O2)3His(H2O)2] | 890 | [350] | |

| (NH4)3[(UO2)2(O2)3salcy(H2O)2] | 895 | [350] | |

| K4[(UO2)4(O2)2(C10H13O8N2)2(IO3)2]·16H2O | 790 | 890 | [351] |

| LiK3[(UO2)4(O2)2(C10H12O8N2)2(H2O)2]·18H2O | 833 | 890 | [351] |

| Na10[(UO2)O2(C3H2O4)]5·20H2O | 806 | [349] | |

| NaK15[(UO2)8(O2)8(C10H12O10N2)2(C2O4)4]·14H2O | 819 | 871 | [351] |

| Li4K6[(UO2)8(O2)6(C10H12O10N2)2(NO3)6]·26H2O | 817 | 890 | [351] |

| LiU24 | 813 | [352] | |

| BiU24 | 814 | [352] | |

| PbU24 | 814 | [352] | |

| LiU24 | 814 | [140] | |

| LiU28 | 809 | [140] | |

| U24Fe24P | 803 | 873 | [176] |

| Na4[(UO2)(S2)3](CH3OH)8 | [353] | ||

| Halides and Hydroxides | |||

| CS2UO2Br4 | 836 | 920 | [101] |

| [Li(12-crown-4)]2[UO2Br4] | 822 | 913 | [354] |

| [Na(15-crown-5)]2[UO2Br4] | 824 | 904 | [354] |

| [K(18-crown-6)]2[UO2Br4] | 816 | 916 | [354] |

| Rb2[UO2Cl4]·2H2O | 839 | 907 | [146] |

| CS2[UO2Cl4] | 832 | 922 | [125] |

| 834 | 922 | [101] | |

| [Me4N]2[UO2Cl4] | 831 | 909 | [125] |

| [Bmim]2[UO2Cl4] | 839 | 920 | [126] |

| [Bmim]2[UO2Cl4] | 835 | 918 | [126] |

| [Emim]2[UO2Cl4] | 827 | 908 | [126] |

| [Emmim]2[UO2Cl4] | 835 | 916 | [126] |

| [Bmmim]2[UO2Cl4] | 831 | 908 | [126] |

| [PPh4]2UO2Cl4 (P1−) | 838 | 919 | [125] |

| [PPh4]2UO2Cl4 (P21/c) | 823 | 904 | [125] |

| [PPh4]2UO2Cl4·2CH2Cl2 | 833 | 912 | [125] |

| [PPh4]2UO2Cl4·2MeCN | 832 | 911 | [125] |

| [PPh4]2UO2Cl4·MeOH | 836 | 914 | [125] |

| [AsPh4]2UO2Cl4·2CH2Cl2 | 834 | 912 | [125] |

| [K(18-crown-6)]2[UO2Cl4]2[UO2Cl4] | 826 | 923 | [354] |

| [Na(15-crown-5)]2[UO2Cl4]2[UO2Cl4] | 838, 843 | 910 | [354] |

| [Li(12-crown- 4)]2[UO2Cl4]2[UO2Cl4] | 822 | 913 | [354] |

| UO2Cl2((N(CH3)2)3PO)2 | 831 | 920 | [355] |

| UO2F2(CH3NH2CO) | 854 | 955 | [356] |

| UO2F2DMA | 852 | 941 | [356] |

| UO2F2DMF | 857 | 930 | [356] |

| UO2F2DMSO | 851 | 938 | [356] |

| UO2F2((H2N)2CO) | 834 | 915 | [356] |

| UO2F2(H2O)2 | 870 | 940 | [356] |

| UO2F2(C11H12N2O) | 848 | 935 | [356] |

| UO2F2)(CH3NH)2CO | 851 | 940 | [356] |

| UO2F2((CH3)2N)2CO | 848 | 930 | [356] |

| UO2F2((N(CH3)2)3PO)2 | 831 | 933 | [355] |

| [Co(NH3)6]2[UO2(OH)4]3·H2O | 796 | [357] | |

| Nitrates | |||

| UO2(NO3)2·6H2O | 871 | 939 | [101] |

| 865 | [58] | ||

| UO2(NO3)2·2H2O | 876 | [57] | |

| UO2(NO3)2·2H2O | 876 | [57] | |

| KUO2(NO3)3 | 870 | 950 | [101] |

| 874 | [127] | ||

| CsUO2(NO3)3 | 874 | [127] | |

| 879 | 956 | [101] | |

| RbUO2(NO3)3 | 880 | [127] | |

| 879 | 956 | [101] | |

| NH4UO2(NO3)3 | 880 | [127] | |

| 880 | [128] | ||

| 880 | 952 | [101] | |

| Et4N(UO2)(NO3)3 | 871 | 936 | [101] |

| (C3H5N2)2[(UO2)2 (μ-OH)2(NO3)4] | 853 | [58] | |

| [Bmim]2[(UO2)2(μ-OH)2(NO3)4] | 839 | 922 | [126] |

| (CH3NH2CO)2UO2(NO3)2 | 860 | 938 | [101] |

| (phen)(UO2)(NO3)2 | 862 | 942 | [101] |

| (NO)UO2(NO3)3 | 869 | 949 | [358] |

| (Ph3PO)2UO2 (NO3)2 | 848 | 920, 932 | [101] |

| (Ph3AsO)2UO2(NO3)2 | 818 | 920, 930 | [101] |

| ((EtO)3PO)2UO2(NO3)2 | 860 | 935 | [101] |

| [UO2(NO3)2(TEMA)2][OTf]2 | 841 | 919 | [130] |

| [UO2(NO3)2(TEGA)2][OTf]2 | 860 | 932 | [130] |

| [UO2(NO3)2(TEAA)2][OTf]2 | 857 | 929 | [130] |

| [UO2(NO3)2(TEPA)2][OTf]2 | 854 | 929 | [130] |

| [UO2(NO3)2(TESUA)2][OTf]2 | 846 | 923 | [130] |

| UO2(NO3)2(NBP)2 | 856 | 934 | [359] |

| UO2(NO3)2(NCMeP)2 | 856 | 933 | [359] |

| UO2(NO3)2(DMI)2 | 850 | 931 | [359] |

| UO2(NO3)2(N(CH3)2)3PO)2 | 845 | 932 | [355] |

| Isothiocyanate | |||

| (C10H10N)3[UO2(NCS)5]·3H2O | 849 | 906 | [360] |

| (C10H10N)3[UO2(NCS)5] | 849.5 | 908 | [360] |

| (C10H9N2)3[UO2(NCS)5] | 836 | 897 | [360] |

| (C10H10N2)1.5[UO2(NCS)5]·2H2O | 837.5 | 908 | [360] |

| (C10H10N2)2[UO2(NCS)5]·NO3 | 844 | 901,914 | [360] |

| [Bmim]3[UO2(NCS)5] | 847 | 920 | [126] |

| [(CH3)4N]3UO2(NCS)5 | 841 | [361] | |

| [(C2H5)4N]3UO2(NCS)5 | 847 | [361] | |

| [(C3H7)4N]3UO2(NCS)5 | 846 | [361] | |

| (C10H10N2)2[UO2(NCS)4(NCS)0.75(Cl)0.25]·(SCN) | 842 | 901 | [360] |

| (C10H10N2)2[UO2(NCS)4Cl]·Cl·2H2O | 842 | 908 | [360] |

| UO2(NCS)2((CH3NH2CO))3 | 854 | 939 | [356] |

| UO2(NCS)2((H2N)2CO)3 | 837 | 910 | [356] |

| UO2(NCS)2((N(CH3)2)3PO)2 | 840 | 928 | [355] |

| [nBu4N]3[UO2(NCS)5] | 850 | 919 | [362] |

| [Me3NBz]3[UO2(NCS)5] | 845 | 916 | [362] |

| [Et3NBz]3[UO2(NCS)5] | 842 | 910 | [362] |

| [Ph4P]2[UO2(NCS)3(NO3)] | 860 | 928 | [362] |

| [Me4N]3[UO2(NCSe)5]·H2O | 848 | 920 | [362] |

| [n Pr4N]3[UO2(NCSe)5] | 852 | 926 | [362] |

| [Et3NBz]3[UO2(NCSe)5] | 842 | 920 | [362] |

| Oxygen Donors (Carboxylates, Oxalate, Ketones) | |||

| Coordination Complexes | |||

| [HNEt3]2[UO2PDC2]·2H2O | 825 | [363,364] | |

| [C4H12N2][(UO2)2(C6H5O7)2](H2O)6 | 825 | 917 | [16] |

| [Na4(C4H12N2)6][(UO2)6O2(C6H4O7)6](H2O)38 | 800 | 890 | [16] |

| [Na9(Mg(H2O)4)3][(UO2)9(OH)3O3(C6H4O7)6](H2O)13 | 790 | 880 | [16] |

| (Na3[(UO2)3(OH)3(ida)3]·8H2O | 816 | 890 | [133] |

| (pip)2[(UO2)3O(mal)3]·6H2O | 816 | 890 | [133] |

| (pip)6[(UO2)11(O)4(OH)4(mal)6(CO3)2]·23H2O | 816 | 890 | [133] |

| Na[Mg(H2O)6)][UO2(CH3COO)3]2 | 852 | 929 | [365] |

| Na[Co(H2O)6)][UO2(CH3COO)3]2 | 851 | 927 | [365] |

| Na[Ni(H2O)6)][UO2(CH3COO)3]2 | 851 | 928 | [365] |

| Na[zn(H2O)6)][UO2(CH3COO)3]2 | 851 | 928 | [365] |

| [UO2(C10H8N2)(C7H3Cl2O2)2] | 850 | 928 | [366] |

| [UO2(OH)(C15H11N3)(C7H3Cl2O2)3] | 836 | 930 | [366] |

| [UO2(OH)(C15H10N3Cl)(C7H3Cl2O2)3] | 841 | 926 | [366] |

| [(UO2)(NO3)2(HINT)2] | 828 | [367] | |

| [C4H12N2]2[(UO2)(C5O5)3(H2O)]·3H2O | 848 | [368] | |

| [C4H12N2]2[(UO2)(C5O5)3(H2O)]·3H2O | 833 | [368] | |

| [dabcoH2][UO2(C2O4)2(H2O)]·2H2O | 834 | 912 | [369] |

| [dabcoH2][(UO2)2(C2O4)3(H2O)2]·2H2O | 848 | 928 | [369] |

| [pipH2] [UO2(C2O4)2(H2O)]·4H2O | 839 | 924 | [369] |

| [pipH2][(UO2)2(C2O4)3(H2O)2]·2H2O | 852 | 939 | [369] |

| (UO2)4(pdzdc)3(OH)2(H2O)5·11H2O | 830, 845, 854, 865 | 928 | [370] |

| [UO2(C7H3BrIO2)2]n | 854 | 946 | [371] |

| [UO2(C12H8N2)(C7H4ClO2)2]2 | 839 | 912 | [371] |

| [UO2(C12H8N2)(C7H4BrO2)2] | 834.5 | 908 | [371] |

| [UO2(C12H8N2)(C7H4IO2)2] | 840 | 912 | [371] |

| [UO2(C12H8N2)(C7H4ClO2)2] | 841 | 922 | [371] |

| [UO2(C12H8N2)(C7H4BrO2)2] | 839.5 | 922 | [371] |

| [UO2(C12H8N2)(C7H4IO2)2 | 838 | 920 | [371] |

| [UO2(C15H11N3)(C7H4ClO2)2] | 826 | 916 | [371] |

| [UO2(C15H11N3)(C7H4BrO2)2] | 826 | 916 | [371] |

| [UO2(C15H11N3)(C7H4IO2)2] | 821.5 | 910 | [371] |

| [UO2(C12H8N2)2(C7H2F3O2)2]·(C12H8N2) | 816 | 900 | [372] |

| [UO2(OH)(C12H8N2)(C7H2F3O2)]2 | 843.5 | 918.5 | [372] |

| [UO2(C12H8N2)2(C7H2Cl3O2)2]·2H2O | 844 | 888.5 | [372] |

| [UO2(C12H8N2)(C7H2Cl3O2)2] | 847 | 924 | [372] |

| [UO2(C12H8N2)2(C7H2Br3O2)2] | 839 | 886.5 | [372] |

| [UO2(OH)(C12H8N2)(C7H2Br3O2)]2 | 841 | 909 | [372] |

| [UO2(C12H8N2)(C7H2Br3O2)2]2 | 874.5 | 937 | [372] |

| [UO2(C12H8N2)(C7H5O2)2] | 833 | 913 | [372] |

| [UO2(C15H11N3)(C7H3Cl2O2)2] | 833 | 919 | [373] |

| [UO2(C15H11N3)(C7H3Br2O2)2] | 834 | 920 | [373] |

| [UO2(C15H10ClN3)(C7H3Cl2O2)2] | 836 | 921 | [373] |

| [UO2(C15H10ClN3)(C7H3Br2O2)2] | 826 | 910 | [373] |

| UO2(ba)2 TPPO | 830 | 938 | [374] |

| UO2(ba)2 ADA | 816 | 941 | [374] |

| UO2(ba)2 AzA | 814 | 941 | [374] |

| UO2(sal)2 | 834 | 924 | [375] |

| UO2(2H1N)2 | 841 | 920 | [376] |

| UO2(HBDM)2 | 836 | [377] | |

| UO2(HBTF)2 | 830 | [377] | |

| UO2(acac)2 | 836 | 921 | [378,379] |

| K2(UO2)(H2O)(C5O5)2 | 831 | 895 | [380] |

| UO2(SO4)(HMPA)2 | 834 | 927 | [355] |

| α-UO2SO4(CO(NH2)2)2 | 845 | [290] | |

| β-UO2SO4(CO(NH2)2)2 | 859 | [290] | |

| UO2Cl2(THF)2]2 | 835 | [381] | |

| UO2(Otf)2(THF)3 | 842 | [381] | |

| Coordination Polymers | |||

| Ni(UO2)(PDC)2(H2O)4]·4(H2O) | 859 | [364] | |

| Co(UO2)(PDC)2(H2O)4]·4(H2O) | 864 | [364] | |

| Fe(UO2)(PDC)2(H2O)4]·4(H2O) | 857 | [364] | |

| Zn(UO2)(PDC)2(H2O)4]·4(H2O) | 858 | [364] | |

| Co(UO2)(PDC)2(H2O)4]·4(H2O) | 860 | [364] | |

| [C4H12N2][(UO2)(C4O4)2(H2O)]·H2O | 829 | [368] | |

| [C5H6N][(UO2)(C4O4)(OH)]·(H2O)2 | 834 | [368] | |

| [C2H10N2]2[(UO2)6(C4O4)3(O)2(OH)6] | 847 | [368] | |

| [C2H10N2]5[(UO2)6(C5O5)6(O)2(OH)6(H2O)4] | 829 | [368] | |

| (UO2)3(C2H5NO2)2(O)2(OH)2](H2O)6 | 819 | 904 | [147] |

| [(UO2)3(C2H5NO2)2(O)2(OH)2](H2O)1.5 | 809 | 903 | [147] |

| [(UO2)3(C3H6NO2)2O(OH)3](NO3)(H2O)3 | 840 | 930 | [147] |

| [C6H13N2][(UO2)3(HCOO)2O(OH)3]4H2O | 844 | 925 | [147] |

| (C4H12N2)[(UO2)2(C4H3O5)2]·4H2O | 826 | [257] | |

| [(UO2)(C4H3O5)Cu(C10H8N2)Cl(H2O)]·2H2O | 841 | [257] | |

| [(UO2)2(C4H3O5)2Cu(C5H5N)2(H2O)2]·2H2O | 833 | [257] | |

| [(UO2)2(C7O3H6)2(C7O3H5)(DMF)(H2O)3]·4H2O | 854 | [136] | |

| [(UO2)(C8O4H6)(DMF)] | 841 | [136] | |

| [(UO2)(OH)(INT)] | 833 | [367] | |

| [(UO2)3CuO2(C6NO2)5] | 809, 839 | 909 | [382] |

| [(UO2)Cu(C6NO2)3] | 840, 865 | 909 | [382] |

| (UO2)(C14O4H8) | 848 | 932 | [383] |

| [(UO2)2(C14O4H8)2(OH)]·(NH4)(H2O) | 873? | [383] | |

| (UO2)2(C14O4H8)(OH)2 | 829, 855 | [383] | |

| (UO2)2[UO4(trz)2](OH)2 | 837 | 904 | [384] |

| 769 | 880 | ||

| (UO2)8O2(OH)4(H2O)4(1,3-bdc)4 3 4H2O | 810 | 880 | [385] |

| 834 | 901 | ||

| 846 | 923 | ||

| 852 | 942 | ||

| (UO2)(OH)(Pic) (HPic = picolinic acid) | 845 | [255] | |

| (NH4)[(UO2)3(O)2(OH)(Pic)2] | 820 | [255] | |

| Sr1.5[(UO2)12(O)3(OH)13(bdc)4]·6H2O | 851, 837, 816? | [135] | |

| K3[(UO2)12(O)3(OH)13(bdc)4]·8H2O | 855, 836, 818? | [136] | |

| (ED)[(UO2)(btca)]·(DMSO)·3H2O | 838, 818 | 945, 868 | [134] |

| (NH4)2[(UO2)6O2(OH)6(btca)]·~6H2O | 851 | [134] | |

| [(UO2)2(H2O)(btca)]·4H2O | 946–920, 871 | [134] | |

| Nitrogen Donor Ligands | |||

| [UO2(dapdoH2)Cl]2 2,6-diacetylpyridine dioxime (dapdoH2) | 850 | 901 | [386] |

| (1,8-napththalimide dioxime)(UO)2(NO3)(CH3OH) | 867 | 935 | [387] |

| (UO2(ZT)·5H2O | 859 | 945, 821 | [388] |

| Non-Aqueous Systems | |||

| UO2Cl2(C14N4H16) | 813 | [381] | |

| UO2Cl2(C16N4H21) | 815 | [381] | |

| UO2(Otf)THF(C16N4H21)[OTf] | 833 | [381] | |

| UO2(Otf)2(C14N4H16) | 831 | [381] | |

| [UO2(salmnt(Et2N)2)(H2O)] | 826 | 898 | [389] |

| [UO2(salmnt(Et2N)2)(pyd)] | 823 | 893 | [389] |

| [UO2(salmnt(Et2N)2)(DMSO)] | 828 | 885 | [389] |

| [UO2(salmnt(Et2N)2)(DMF)] | 819 | 899 | [389] |

| [UO2(salmnt(Et2N)2)(TPPO)] | 820 | 888 | [389] |

| UO2(sal-p-phdn)) | 842, 829 | 930,915 | [390] |

| [UO2Cl(η3-CH(Ph2PNSiMe3)2)(THF)] | 825 | 908 | [391] |

| [UO2Cl(η3-N(Ph2PNSiMe3)2)(THF)] | 829 | 909 | [391] |

| [UO2Cl(η3-N(Ph2PNSiMe3)2)]2 | 846 | 924 | [391] |

| [UO2(N(SiMe3)2)(η3-CH(Ph2PNSiMe3)2)] | 823 | 918 | [391] |

| [Na(THF)2][UO2(N(SiMe3)2)3] | 805 | 928 | [392] |

| Phosphorus Containing Ligands | |||

| AgUO2[CH2(PO3)(PO3H)] | 816, 829 | [393] | |

| [Ag2(H2O)1.5][(UO2)2[CH2(PO3)2]F2]·(H2O)0.5 | 822 | [393] | |

| Ag2UO2[CH2(PO3)2] | 802 | [393] | |

| K5(UO2)2[B2P3O12(OH)]2(OH)(H2O)2 | 822 | [394] | |

| K2(UO2)12B(H2PO4)4](PO4)8(OH)(H2O)6 | 808, 839, 868 | [394] | |

| [EMim][UO2(pmbH2)0.5(pmbH2)0.5(ox)0.5] | 831 | 918 | [395] |

| [BMMim]2[(UO2)2(pmbH2)(pmb)] | 824 | 910 | [395] |

| [C4mim][(UO2)2(1,3-pbpH)(1,3-pbpH)·Hmim] | 820 | 909 | [396] |

| [UO2(1,3-pbPh2)H2O·mpr] | 847 | 918 | [396] |

| [Etpy][UO2(1,3-pbPh2)F] | 824 | 908 | [396] |

| [H2bipy]2[(UO2)6Zn2(PO3OH)4(PO4)4]·H2O | 833 | [397] | |

| trans-UO2(N(NO2)2)2(OP(NMe2)3)2 | 833 | 888 | [398] |

| [UO2(OP(NMe2)3)4][N(NO2)2]2 | 833 | 918 | [398] |

| [UO2(N(CN)2)2(OP(NMe2)3)2]2 | 849 | 928 | [398] |

| UO2((NC)2C2N3)2(OPPh3)3 | 854 | 933 | [398] |

| [UO2(ReO4)2(TPPO)3] | 823 | 933 | [399] |

| [((UO2)(TPPO)3)2(μ2-O2)][ReO4]2 | 826 | 931 | [399] |

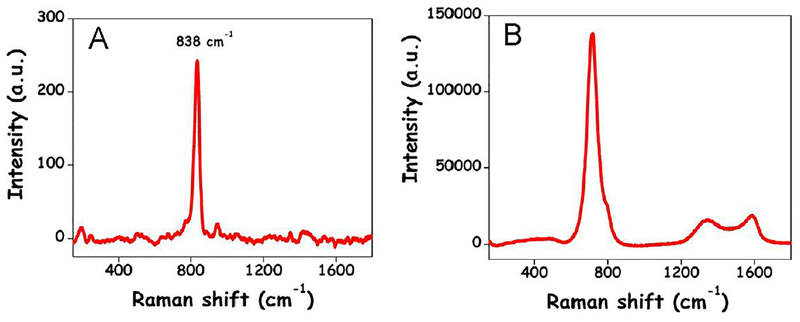

Average symmetric stretching mode and vibrational frequency ranges for simple coordination complexes and more complex uranyl organic compounds are provided in Fig. 7. Uranyl coordination complexes exhibit more discrete vibrational frequencies compared to the larger spectral ranges observed for complex species containing peroxides and phosphonates. This is understandable as the coordination spheres within these two types of ligands are chemically complex and change dramatically by forming diverse extended lattices. O-donating ligands such as ketones, carboxylates, and alcohols are also diverse as multiple coordination geometries and topologies can form (see Table 2).

Fig. 7.

Box and whisker plot for well-defined uranyl coordination complexes that describes the median (solid vertical line within box, range (whiskers), and mean (x) values for the uranyl symmetric stretching mode (ν1). The X in UO2(NO3)2X2, UO2F2X2 and UO2(O2)Xn represents substitution by a range of O- and N-donor ligands. Uranyl phosphonates and O donors (both isolated molecular species and coordination polymers with ligands containing carboxylate, oxalate, or ketones) were not included in this plot due to the diversity of coordination modes and ligands within these groups of compounds. Frequencies for all uranyl coordination complexes and polymers can be found in Table 2.

Several additional trends are noted within uranyl coordination compounds and hybrid materials. First, the coordination compounds (UO2)Lx (X = 3, 4, or 5) show that the symmetric mode increases as follows: NO3 < CH3COO < SCN < Cl, Br < CO3 < O2 < OH. Nguyen Trung et al. [14] reported a similar trend for solution phase species. A notable exception is that solution phase UO2(CH3COO)3 exhibits a band at 843 cm−1, which is lower in energy than the soluble tetrahalides (UO2Cl4 (854 cm−1) [14]. The opposite is true for solid phases.

Differences between the solution and solid-state spectra are likely related to crystallization effects as well as intermolecular interactions between neighboring cations with the uranyl oxo atoms. Careful evaluation of the uranyl tetrachloro system, which has been thoroughly characterized in solution and in 18 solid-state coordination compounds, provides us with an excellent platform to understand these effects. Schnaars and Wilson [125] systematically studied [UO2Cl4]2− complex crystallized with the tetraphenylphosphonium/tetraphenylarsonium cation and various solvent molecules. The ν1 mode was shown to be independent of solvent composition and tetraphenylarsonium cation presence. Crystal packing of the [PPh4]2UO2Cl4 compound induced the largest impact on this vibrational frequency. Two polymorphs formed with either a triclinic (P-1) cell (838 cm−1) or a monoclinic form (823 cm−1). Schnaars and Wilson [125] hypothesized that the 15 cm−1 difference in the symmetric stretching band arose from either 1) additional hydrogen bonding to the uranyl oxo in the monoclinic form or 2) subtle differences in the UACl bond lengths that would lead to an increased electrostatic effect and uranyl bond destabilization. Qu et al. demonstrated similar effects by crystallizing the uranyl tetrachloro species with imidazolium cations [126]. An 8 cm−1 difference was observed between [Emim]2UO2Cl4 (Emim = 1-ethyl-3-methyl-imidazolium; 827 cm−1) and [Emmim]2UO2Cl4 (Emmim = 1-ethyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium; 835 cm−1). Hydrogen bonding interactions between uranyl oxo atoms and the charged imidazolium group were used to describe these vibrational frequency variations. Hydrogen bonding interactions were disrupted upon methyl group substitution at the N1 position for Emmim+. Consistent with Raman spectral features in general, this suggests that hydrogen bonding interactions and other intermolecular forces can influence the ν1 frequency from solid-state samples.

Equatorial ligand composition also influences the ν1 frequency because of variations in the electron-donating capabilities of the ligand and the coordination environment. The uranyl nitrate system, which has several different substitutions, provides an excellent system to discuss these differences. The ν1 mode for X[(UO2) (NO3)3] X = K, Cs, Rb, NH4, Et4N ranges from 880 to 870 cm−1 with an average value of 875 cm−1 [101,127,128]. Substitution of a nitrate group for two water molecules in the trans position occurs in case of uranyl nitrate hexahydrate [(UO2)(NO3)2(H2O)2]·6 H2O and the dihydrate form, resulting in a slight decrease in the symmetric stretching vibrational frequency (876–865 cm−1) [57,58,129]. Ligands that provide sigma donation (PPh3O or diamide ligands-Et2N(C=O)(CH2)n(C=O)NEt2, cyclic amides) form [(UO2)(NO3)2(L)2] species, which also cause the vibrational frequency to decrease in energy [130]. Ligand position likely influences the extent of vibrational energy change. For instance, when the nitrate groups of diamide ligands are in the trans position, the ν1 frequency is observed between 860 and 854 cm−1 [130]. Complexes that contain the nitrate ligands in the cis-conformation exhibit modes centered at 846 and 841 cm−1. Similar trends are observed for cyclic amides where all three compounds contain nitrate ligands in the trans position and ν1 bands for uranyl between 856 and 850 cm−1 [130].

Hydrolysis of the U(VI) cation leads to the formation of larger oligomers and variations in the symmetric stretching mode. When hydrolysis occurs, olation or oxolation reactions result in the formation of bridged hydroxo or oxo groups [131]. These bridging groups provide additional electron donation to the metal centers, which further lowers the vibrational mode energy and causes the vibrational feature to broaden 20–30 cm−1 [14,132]. The uranyl nitrate and citrate systems provide excellent platforms for demonstrating this. The [(UO2)(NO3)2(H2O)2] complex exhibits a vibrational frequency between 876 and 865 cm−1 and hydrolysis to the dimeric form [(UO2)2(OH)2(NO3)4]2− causing this mode to red shift to 853 cm−1 in solid state spectra [58]. Similar trends in m1 are observed for the uranyl citrate system. The 2:2 U:citrate dimer occurs at 825 cm−1 in the solid state while the trimeric 3:2 and 3:3 U:citrate species are observed at 800 and 790 cm−1, respectively[16].

Overlapping vibrational modes increase the difficulty of spectral interpretation for coordination compounds and hybrid materials, particularly in the presence of some organic ligands or peroxide molecules. Spectral features from chelating ligands were specifically noted for the citrate [16], malate [133], pyromellitate [134], benzenedicarboxylate [135], and hydrobenzoate [136] systems. Similarly, uranyl peroxide spectra contain overlapping modes from uranyl and peroxide stretches. The peroxide mode frequency depends on the coordination to uranyl polyhedra and ranges from 904 to 822 cm−1 [137,138]. In the case of LiK3[(UO2)4(O2)2(C10H12O8N2)2(H2O)2]·18 H2O, two partially resolved vibrational features are located near 830 cm−1 [139]. Speciation assignment of these bands was achieved using both isotopic labeling and DFT calculations. These techniques were highlighted in the case of uranyl triperoxide (UO2(O2)3)4− complexes where the ν1 mode was observed between 738 and 677 cm−1 [140]. Empirical band predictions based upon bond distances do not accurately predict vibrational frequency, indicating a need for additional computational approaches. Quantum considerations that were developed by Vallet et al. [141] and utilized by Dembowski [138] for the peroxide system provided better agreement between the predicted (717 cm−1) and experimental (710 cm−1) values.

3.3. Spectroscopy as predictive tools for solid state bonds

Many spectroscopic investigations of solid-state materials focus on vibrational mode frequencies, but additional information is available from established semi-empirical relationships. The vibrational frequency can be calculated using Hooke’s law, and as a result, depends on bond lengths and force constants. Force constants provide an initial estimation of bond strength to understand the influence of the equatorial ligands on the uranyl bond [39]. Accumulated empirical vibrational spectra also allow for the estimation of vibrational frequency based on bond lengths and coordinating ligands. This section provides both the background for these relationships and an updated analysis based upon the larger data-set provided in Tables 2 and 3.

Empirical equations can be derived from experimentally observed vibrational frequencies, which are then used to calculate force constants [142,143]. For example, the vibrational frequency for a chemical bond can be modeled using Hooke’s law, and the relationship between vibrational frequency and force constant (kF) can be derived as follows:

| (1) |

where , kF, μ and c are the vibrational frequency (cm−1), force constant (N/m), reduced mass (kg), and speed of light in a vacuum, respectively. The force constant can be represented using the following equations [101,144]:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where is the symmetric stretching frequency, is the asymmetric stretching frequency, is the bending frequency, mO is the atomic weight of oxygen, mU is the atomic weight of uranium, k12 is the stretching interaction constant (dynes/cm), kδ is the bending force constant, and r is the uranyl bond length.

Force constants for uranyl compounds have been reported since the early 1960s and are now again gaining traction to quickly assess relative bond strength. McGlynn et al. [145] and Bartlett and Cooney [63] first reported a range of force constants for uranyl compounds and more recently, Schnaars and Wilson [125,146] utilized force constants within uranyl tetrachloride complexes to understand slight differences in bond strength. Force constants have also been used to evaluate subtle differences in intermolecular interactions within carboxylate complexes and to assess the impact of charge-assisted hydrogen bonding within uranyl glycine compounds [147]. Previously, the lowest kf value for isolated uranyl complexes was reported for K3UO2F5 at 6.03 mdyn/Å [63], although a majority of the values were observed between 6.4 and 7.5 mdyn/Å. Lower values were observed for extended compounds with the U(VI) cation in octahedral coordination. Expanding this to our current work reveals similar trends with a majority of compounds exhibiting force constants in the same region, even within non-aqueous compounds. One benefit in utilizing force constants is that these can provide relative bond strengths for a particular set of ligands. If we order the [(UO2)Lx] X = 3, 4, 5 complex from largest to smallest force constants, which are NO3 > CH3COO > Cl, SCN > Br > CO3 > OH, then trends in Raman vibrational frequencies are understood as these are directly related. A decrease in kf by 0.18 is observed when [(UO2)(NO3)2L] forms upon ligand substitution. It is important to note that the k12 is always a small (−0.1 to −0.25) negative value that does not change significantly upon ligand substitution.

When k12 is small with respect to kF, the relationship between the symmetric stretching and asymmetric stretching modes is ν1 = 0.939·ν3 [101]. As a first approximation for predicting the symmetric mode frequency, this works reasonably well. The k12 is always non-zero so additional formulas have been postulated for both solid state and solution samples. The empirical results for solid state species are ν1 = 0.89· ν3 + 30.8 (cm−1) [148], 0.89· ν3 + 21 (cm−1) [145], or 0.912 ν3 − 1.04 (cm−1) while the empirical result in aqueous solution is ν1 = 0.795· ν3 + 107 (cm−1) [149]. Cejka previously noted that these relationships are likely influenced by structural details (hydrogen bonding, crystalline packing) and character of the ligands on the equatorial plane thereby warranting further study on these relationships [39].

By focusing on the well-characterized [UO2Cl4]2− system, a comparison among the three empirical results for symmetric stretching feature predictions can be made. Using the equation from Bartlett and Cooney [63] (ν1 = 0.89· ν3 + 30.8 (cm−1)) results in an average difference of 11.2 cm−1 between the predicted and experimentally determined v1 frequencies. In comparison, the predicted and experimental values differ by ~3.2 and ~3.1 cm−1 when utilizing the McGlynn et al. [145] (ν1 = 0.89·ν3 + 21 (cm−1)) or Bagnall and Wakerley [150] (ν1 = 0.912·ν3 − 1.04 (cm−1)) relation ships, respectively. The largest differences were observed with the densely packed solids, Rb2UO2Cl4·2H2O and Cs2UO2Cl4 using the Bagnall and Wakerley [150] and McGlynn et al. [145] equations where average differences were 11.8 and 8.7 cm−1, respectively.

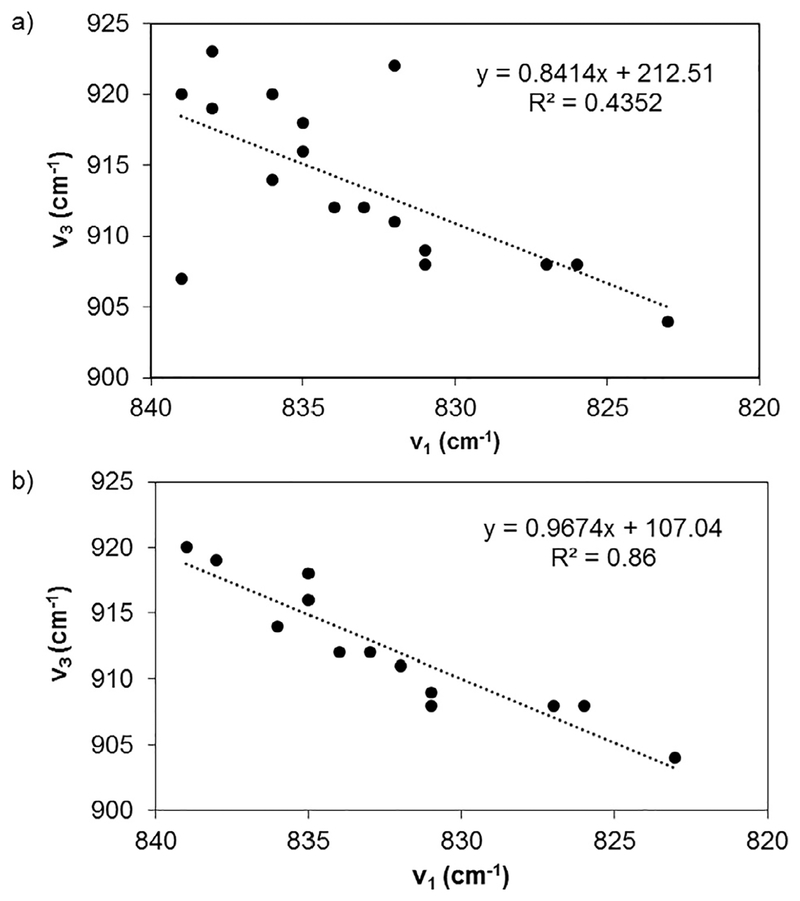

To investigate if more specialized empirical relationships improve predictions of the vibrational modes that are observed experimentally, least squares regression and well characterized compounds are used. First, ν1 and ν3 frequencies are plotted for uranyl tetrachloride compounds (Fig. 8). Data from densely pack solids and less resolved compounds with crown ether molecules are excluded from the analysis. Least-squares regression produced an identical relationship reported by McGlynn et al. [145] demonstrating that data segregation of specialized compounds does not lead to predictive improvements.

Fig. 8.

The least squares regression for (a) all uranyl tetrachloro compounds and (b) excluding densely packed solids and less resolved crown-ether compounds.

Similar analysis was performed by plotting all spectral data observed for uranyl carbonate and nitrate coordination complexes and hybrid materials. The empirical relationship established by McGlynn et al. [145] provided the most accurate predictions for the ν1 mode with an average difference from experimental values of 7.8 cm−1. Additional data analysis for the uranyl peroxide system and compounds synthesized in non-aqueous conditions reveals differences between predicted and experimentally observed values. Smaller differences could arise from crystallization effects as well as hydrogen bonding and cation-oxo interactions that perturb the uranyl bond within the solid-state compound.

If the force constant is known, then the bond length of uranyl bond (Å) can be estimated. The relationship between the bond length (r) obtained from crystallographic measurements and the force constant (mdyn/Å) is as follows: [143]. This relationship has been utilized extensively for mineralogical samples with variable degrees of success. For coordination compounds, the relationship tends to underestimate the bond distance by an average of 0.07 Å, which is significant for the relatively inflexible uranyl bond.