Abstract

TLC has traditionally been used to analyze lipids isolated from membrane complexes. Here, we describe a method based on the combination of TLC and SDS-PAGE to qualitatively analyze the protein/lipid profile of membrane complexes such as those of lung surfactant. For this purpose, native lung surfactant was applied onto a silica TLC plate in the form of an aqueous suspension, preserving not only hydrophilic proteins associated with lipids but also native protein-lipid interactions. Using native membrane complexes in TLC allows the differential migration of lipids and their separation from the protein components. As a result, (partly) delipidated protein-enriched bands can be visualized and analyzed by SDS-PAGE to identify proteins originally associated with lipids. Interestingly, the hydrophobic surfactant protein C, which interacts tightly with lipids in native membrane complexes, migrates through the TLC plate, configuring specific bands that differ from those corresponding to lipids or proteins. This method therefore allows the detection and analysis of strong native-like protein-lipid interactions.

Keywords: lung surfactant, phospholipids, proteomics, diagnostic tools, lipoprotein, thin-layer chromatography

TLC is a traditional technique typically used to separate and study lipid composition in many biological tissues (1–5) and membrane complexes. An example of this is lung surfactant (LS) (6–13), a protein/lipid complex lining the air-liquid interface in alveoli that allows breathing and facilitates gas exchange. LS composition is conserved in a fair number of mammalian species (14–16) and comprises 90 wt.% lipids and 8–10 wt.% proteins. From the lipid fraction, phospholipids are the most abundant components. Among them, phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylserine, and small amounts of sphingolipids such as sphingomyelin (SM) have been identified by TLC. Neutral lipids, especially cholesterol, are also present.

Proteins coisolated together with LS complexes are typically in close contact with lipids, such as in the case of surfactant protein (SP) A (17), whereas other soluble, nonlipid interacting proteins present in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) (18) are lost during LS purification (19).

The so-called surfactant-associated proteins SP-A, SP-B, SP-C, and SP-D have been traditionally studied after their separation from their native lipid context by means of electrophoresis and Western blot. However, due to the high lipid content in BAL or isolated surfactant, electrophoresis and blotting often result in deformed protein bands and poor detection. Moreover, small fractions of strongly interacting lipids are usually coisolated with the hydrophobic proteins SP-B and SP-C, making their study by Western blot a difficult task.

Here, we present a methodology that overcomes those difficulties by combining TLC and electrophoresis to qualitatively study the lipid and protein fingerprint of whole native surfactants (NSs) or other native membrane complexes. Lipid characterization by TLC typically includes the organic extraction of the lipid component from a given biological sample. Extracted samples solubilized in organic solvents are then directly applied on the TLC silica plates, avoiding water-soluble “contaminants” such as proteins. We propose an alternative method that preserves polar lipid-protein interactions and allows the simultaneous lipid/protein characterization of LS samples and other membrane complexes. An example application to the study of protein-lipid interactions of small-membrane proteins is also presented.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All phospholipid standards were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL), and HPLC-grade organic solvents were from LabScan (Gliwice, Poland). The N-terminal peptide from eNOS was provided by Ignacio Rodriguez-Crespo (Complutense University, Madrid, Spain), and bacteriorhodopsin was from Esteve Padros (Autonomous University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain). SP-C was isolated from porcine lungs as previously described (20). SP-C and SP-B analogues (KL4: KLLLLKLLLLKLLLLKLLLLK; KL2A2: KLAALKLAALKLAALKLAALK; KL4PQ: KLLLLKLLLLPQLLLLKLLLLK) were synthesized by F-moc matrix-assisted chemistry at Pompeu Fabra University (Barcelona, Spain). Protein stocks were prepared as follows: eNOS (1 mg/ml) in methanol and SP-C and SP-B analogs (1 mg/ml) in chloroform-methanol (2:1; v/v). Native SP-C and bacteriorhodopsin were preserved as isolated. Lipid stocks were prepared and stored at the desired concentrations in chloroform-methanol (2:1; v/v).

Isolation of porcine LS

Native porcine LS was purified from BAL by NaBr density gradient centrifugation as previously described (21). Briefly, BAL specimens were obtained by introducing and recovering 5 mM ice-cold Tris in 0.9% NaCl into the trachea of porcine lungs obtained from the slaughterhouse. BAL specimens were gauze-filtered and centrifuged to remove cells and debris. Supernatants containing cell-depleted BAL specimens were collected and stored at −20°C until use. To obtain the full membrane fraction, samples were thawed and centrifuged at 100,000 g for 1 h at 4°C (70 Ti fixed-angle rotor; Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Pellets were resuspended in 16% NaBr/0.9% NaCl and pooled. This fraction was placed at the bottom of a centrifuge tube, onto which two less-dense solutions, 13% NaBr/0.9% NaCl and 0.9% NaCl, were carefully deposited. Samples in this discontinuous density gradient were centrifuged at 120,000 g for 2 h at 4°C (SW40 Ti swinging-bucket rotor; Beckman Coulter). Surfactant complexes comprising phospholipids and associated proteins formed a compact layer on top of the 13% NaBr/0.9% NaCl solution. Samples were carefully recovered (avoiding the collection of the 13% NaBr/0.9% NaCl solution), further diluted in 0.9% NaCl, and flash-frozen in liquid N2. These samples are termed NSs.

Organic extraction of LS

For LS organic extraction, the protocol of Bligh and Dyer was followed (22). Briefly, samples were mixed with methanol and chloroform in a 1:2:1 volumetric ratio and vigorously mixed for 30 s. Soluble proteins were flocculated by 30 min incubation at 37°C. The addition of 1 vol chloroform and 1 vol water resulted in the formation of two phases that were fully separated by centrifugation (2,000 g for 5 min at 4°C). The organic (bottom) phase was collected, whereas the aqueous (top) phase was subjected to two consecutive extraction steps, yielding the maximum phospholipid extraction. Organic phases were then pooled and stored at −20°C in borosilicate tubes. These samples are termed organic extracts (OEs).

Lipid and lipid/protein sample preparation

To prepare liposome suspensions, lipids alone or a combination of lipid and hydrophobic proteins were mixed in chloroform-methanol (2:1; v/v) in the proportions indicated for each experiment. Samples were dried out under a nitrogen stream and subsequently under vacuum for 2 h in a SpeedVac Concentrator System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Multilamellar suspensions were prepared by rehydrating samples in Tris buffer (5 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7) at 50°C for 1 h with intermittent shacking. For samples containing bacteriorhodopsin, the protein was added during the rehydration step. For each sample, 100 μg phospholipid was used for a final concentration of 10 mg/ml.

TLC: plates and application of samples

Chromatoplates (20 × 20 cm) precoated with Silica gel 60 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) were used in this study. Both samples and standards were applied at a phospholipid concentration of 10 mg/ml as aqueous suspensions (10 µl) or OEs as indicated.

Samples and standards were applied subsequently in small volumes (3–5 µl steps) using a 10 µl Hamilton syringe or pipette forming a line at the bottom of the plate called the application point (AP). Samples were air-dried at room temperature before the next sample application. Once the solvent was evaporated, dried samples appeared indistinguishable from the background. Plates with the applied samples were placed in a fume hood and further dried out at room temperature for 15–20 min. The developing solvent system used in these TLC experiments was chloroform-methanol-water (65:25:4; v/v/v). The chromatographic chamber (Shandon Scientific Co. Ltd., London, UK) was lined on three sides with Whatman No. 1 filter paper wetted with the developing solvent system. The chamber was saturated with fresh solvent for 30 min before running the chromatography. Thereafter, the developed plate was removed and air-dried completely before staining.

For the detection of lipids, the plate was placed vertically in a second chamber saturated with iodine vapor (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Iodine binds to unsaturated carbon bonds of lipid molecules, resulting in dark bands along the TLC plate.

A solution of 0.5% fluorescamine (Sigma-Aldrich) in acetone was sprayed on the plate to detect primary free amine-containing molecules (23), such as amine-containing phospholipids or proteins in our case. The detection of fluorescence is possible under UV light. Images were recorded using a VersaDoc imaging system (Biorad, Hercules, CA) in the epifluorescence mode. For the visualization of both lipids and proteins in the sample plate, fluorescamine was applied, and the images were recorded before iodine staining to avoid fluorescence quenching by iodine vapor.

SDS-PAGE

TLC bands were scratched out and boiled at 99°C for 10 min in a Thermomixer (Eppendorf, Hamburg, DE) after the addition of electrophoresis Laemmli buffer (2% SDS; 62.5 mM Tris, pH 6.8; 10% glycerol; 0.03% bromophenol blue) containing 4% β-mercaptoethanol. Before application into the electrophoresis gels, samples were spun down, pelleting most of the silica gel. Samples were applied either into 13% or Mini-PROTEAN precast gradient polyacrylamide gels (4–16%; BioRad), and electrophoresis was performed in a Mini-PROTEAN system. Visualization of the bands was achieved by silver staining.

Identification of proteins: Western blot and MS

Protein content was analyzed by Western blot. Proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes with a semidry system (BioRad) for 1 h at 2.3 mA/cm2 per membrane and blocked in PBS with Tween 20 (PBS-T; 100 mM Na2HPO4/KH2PO4/1% Tween 20) with 5% skimmed milk at room temperature for 2 h. Membranes were then incubated overnight with the primary antibody in PBS-T with 5% milk at 4°C, washed thoroughly in PBS-T, and incubated with the secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature. Membranes were further washed and then developed using a commercial ECL system (Millipore, Burlington, MA). The primary antibodies used were anti-SP-A (1:2000; provided by Joe Wright), anti-SP-B (1:2000; Seven Hills Bioreagents, Cincinnati, OH), and anti-SP-C (1:2500; Seven Hills Bioreagents). The secondary antibody (1:5000) used in all cases was anti-rabbit (Dako, Santa Clara, CA). Bands from silver-stained gels were analyzed using peptide mass fingerprinting MS/MS by MALDI TOF/TOF.

RESULTS

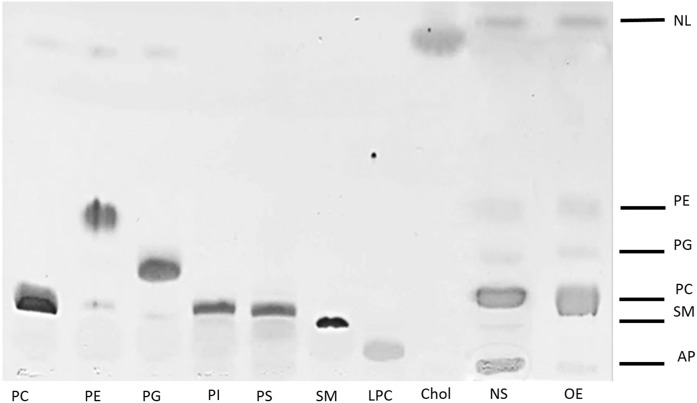

The lipid bands resolved in a TLC of an NS sample applied as an aqueous suspension or as an organic extracted surfactant in organic solvent did not substantially differ and comprised mainly PC, PG, PE, SM, and neutral lipids (Fig. 1). Interestingly, the main difference in the band pattern when comparing surfactant in aqueous and organic solvent solution lied in the AP. Phospholipids were not detected at the AP after organic phosphorous detection (data not shown). However, hydrophilic components of surfactant, such as soluble proteins, were expected to stay at the AP. To analyze the protein content, AP bands were scratched out and subjected to SDS-PAGE and silver staining (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

TLC of surfactant in aqueous solution (NS) and organic solvent (OE). Samples applied include aqueous suspensions of NS purified from porcine bronchoalveolar lavage and its OE applied as a chloroform/methanol solution. Applied lipid standards include PC, PE, PG, PI, PS, SM, LPC, and Chol. Bands stained with iodine revealed SM, PC, PG, PE, NLs (including Chol), and the AP band where water-soluble proteins remain. Chol, cholesterol; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; NL, neutral lipid; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PS, phosphatidylserine.

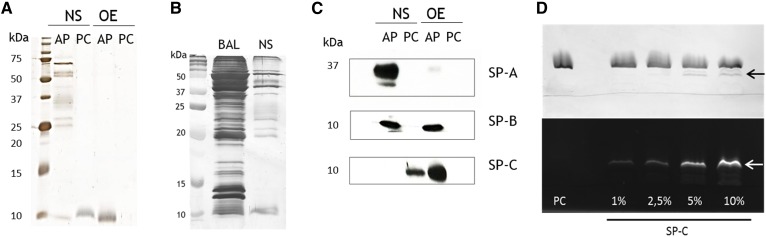

Fig. 2.

Electrophoretic analysis of proteins associated with surfactant samples as extracted from TLC plates. A: Silver staining of an SDS-PAGE performed with the material scrapped from the AP and the PC TLC bands from NS or OE. B: Silver-stained gel of the AP of BAL and NS after TLC. Equivalent amounts of phospholipid were applied (100 µg). C: Immunodetection of surfactant-associated proteins in the AP and PC lanes by Western blot. D: Iodine-stained (top) and fluorescamine-stained (bottom) TLC of lipid/protein samples incorporating different amounts of SP-C expressed in percentage by weight and applied as aqueous suspensions onto the TLC plate. Arrows indicate the position of the band corresponding to SP-C.

Several protein bands were visible at the AP of NS samples (Fig. 2A). As anticipated, those proteins were also detectable in BAL fluid in larger amounts, whereas many other proteins observed in BAL were absent in NS samples (Fig. 2B). Therefore, only proteins with a significant interaction with LS are coisolated with it; hence, the protein bands identified in the AP NS represented specific surfactant-associated proteins. Among them, SP-A, SP-B, and SP-C could be identified by Western blot (Fig. 2C). MS analysis revealed that proteins appearing at the AP in NS were not classical surfactant-associated proteins but involved in the immune response (IgM, IgA), characteristic of blood (albumin, hemoglobin, serotransferrin) or tissue (β-actin) (supplemental Fig. S1).

SP-A, the main hydrophilic SP, was only found in NS and not in OE as expected, whereas SP-B was present at both AP of NS and OE. SP-C, however, did not appear at the AP when samples were applied as aqueous solution but rather run together with PC. To confirm this special behavior, PC liposomes containing increasing amounts of SP-C were also applied as aqueous solutions and analyzed by this method. As observed in Fig. 2D, SP-C configured a different band below that of PC. Higher SP-C content resulted in an increase in the fluorescamine stain intensity, confirming the presence of the protein in those particular bands. These findings suggest that some native SP-C-lipid interactions might still be preserved even under the presence of organic solvents in the developing phase of the TLC. Upon organic extraction this interaction no longer remained, as deduced from the presence of lipid-free SP-C at the AP when organic extracted surfactant was analyzed.

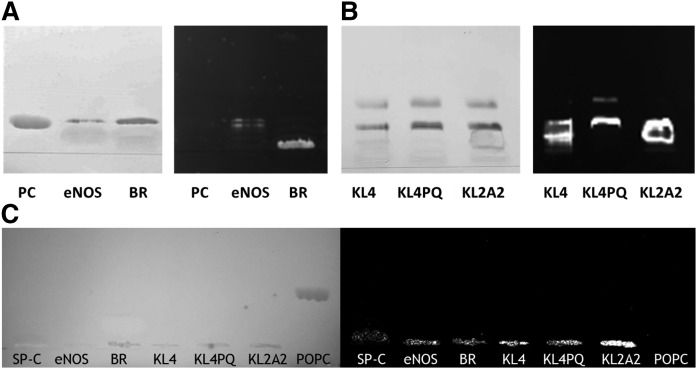

To further analyze whether SP-C behavior was shared by any other small-membrane proteins, different proteins and peptides were reconstituted into PC membranes and tested (Fig. 3). The palmitoylated N-terminal fragment of the enzyme eNOS behaved similarly to SP-C (Fig. 3A), revealing that protein-lipid interactions nonspecific to SP-C might be responsible for this migration pattern. However, a membrane protein of a larger size, such as bacteriorhodopsin, does not migrate out of the AP of the TLC under these conditions despite its sequence being little more than seven transmembrane helices. Small synthetic peptides used as potential surrogates of SPs in the design of synthetic surfactant clinical preparations, such as KL4 or KL2A2, were also able to run along the TLC plate (Fig. 3B) not only associated to PC species but also to PG (such as KL4PQ). Again, this behavior was only detectable when samples were applied as aqueous suspensions, as none of the proteins analyzed migrated through the plate when they were applied in organic solvent (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

TLC analysis of different lipid/protein complexes applied as aqueous suspensions. A: Iodine-developed TLC plate (left) of lipid or lipid/protein membrane complexes applied as aqueous suspensions of PC, PC/eNOS N-terminal segment, and PC/BR and fluorescamine-developed TLC plate (right) revealing the corresponding protein bands. B: Iodine-developed TLC plate (left) of lipid/protein membrane complexes applied as aqueous suspensions of DPPC:POPC:POPG membranes bearing the peptides KL4, KL4PQ, or KL2A2 and fluorescamine-developed TLC plate (right) revealing the corresponding peptide bands. C: Iodine-developed TLC plate (left) of different proteins and peptides (SP-C, eNOS, BR, KL4, KL4PQ, KL2A2) or lipids (POPC) applied in organic solvent and fluorescamine-developed TLC plate (right) revealing the corresponding protein bands at the AP. BR, bacteriorhodopsin; DPPC, dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine; POPC, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; POPG, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol.

DISCUSSION

In this work we have shown a new application for a rather classical technique, TLC. The main novelty relies on the application of native-like lipid/protein samples in aqueous suspension instead of in organic solvents. Thus, sample composition is fully retained as well as many of the molecular polar and hydrophobic interactions especially relevant in the context of membranes.

The added value provided by sample analysis using this methodology is illustrated by the behavior of SP-C, which showed a differential TLC migration pattern compared with other proteins and lipids. SP-C is dually palmitoylated (24), and because of its extremely hydrophobic character, its migration pattern through the TLC plate could be interpreted as SP-C adopting a lipid-like configuration. However, given that SP-C only migrated when the protein was applied as part of lipid/protein complexes in aqueous solutions, SP-C hydrophobicity is not sufficient to explain this behavior. Strong SP-C-phospholipid interactions might then be likely preserved, possibly involving some solvation water molecules. The confirmation of similar behavior for other small-membrane-associated proteins such as the eNOS N-terminal sequence or the surfactant peptide analogues KL4, KL4PQ, and KL2A2 further supports the idea that this migration pattern is due to the preservation of native protein-lipid interactions. Interactions with different (phospho)lipids and the protein-lipid ratio are relevant factors to consider when analyzing specific protein-lipid interactions. In the case of SP-C, its migrating behavior was observed from small to large amounts until 10 wt.%, suggesting that up to 10 wt.% SP-C-lipid interactions are not saturated. However, this cannot be extrapolated to other membrane proteins, for which the role of different protein-lipid ratios and particular lipid species remain to be investigated.

Depending on their polarity, sample components partition between the hydrophobic (solvent) mobile and polar (silica) phases. For this reason, lipids are carried by the developing phase, whereas most proteins remain delipidized at the AP. Upon application as aqueous solutions, tight protein/lipid/water complexes withstanding organic solvent solubilization could allow their migration as a unit along the TLC plate, thus opening the possibility for studying functional lipid-lipid and lipid-protein interactions in native cell membranes.

The behavior of the protein examples analyzed here suggests that for a protein to migrate with lipids in a “native” TLC it needs to have a dominant hydrophobic character, so that an important fraction of its structure could be mobilized while exposed to the organic mobile phase. In the case of SP-C, its α-helix as well as its palmitoylated cysteines are likely fully exposed to the organic solvent, whereas the charged N-terminal segment of the protein could preserve the interaction with some phospholipid head groups thanks to remaining solvation water molecules. Other small amphipathic proteins and peptides could adopt a similar configuration. However, for a protein such as bacteriorhodopsin, with polar groups at the two sides of the membranes, such an orientation toward the organic solvent would be incompatible, hindering its development through the plate. Whether a few specific lipid molecules are retained by these AP-immobilized proteins warrants further investigation.

The methodology presented here also allows studying the hydrophilic component of a sample such as surfactant considering these soluble proteins are strongly associated with membrane/surfactant complexes. This protein fingerprinting could be useful not only for assessing the purity and quality of clinical surfactant preparations but also for understanding and diagnosing lung diseases. For instance, the identification of albumin in surfactant samples might be indicative of edema and fluid leaking into the alveolar spaces, indicating acute respiratory distress syndrome risk or different stages of the disease (25, 26). Other potential molecular markers identified in this work are hemoglobin, which is overexpressed in the lung under hypoxic conditions (19, 27), and IgM and IgA, whose increase is linked to different interstitial lung diseases such as sarcoidosis (28), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, or chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (29). β-Actin might also be considered as a marker of cell damage related to lung disease, whereas serotransferrin levels could be a good indicator of redox activity as detected under the exposure to cigarette smoke (30, 31), NO2 (32), O3 (33, 34), hyperoxia (35, 36), or hypoxia (19, 37).

Taken together, our findings support this novel application of TLC as a promising tool for analyzing and identifying native protein-lipid interactions not only restricted to surfactant samples. In addition, protein/lipid fingerprinting of surfactant samples from patients, animal models, or surfactant clinical preparations may contribute to the understanding and diagnosis of lung diseases.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- AP

- application point

- BAL

- bronchoalveolar lavage

- LS

- lung surfactant

- NS

- native surfactant

- OE

- organic extract

- PBS-T

- PBS with Tween 20

- PC

- phosphatidylcholine

- PE

- phosphatidylethanolamine

- PG

- phosphatidylglycerol

- SM

- sphingomyelin

- SP

- surfactant protein

This work was supported by Spanish Ministry of Economy Grant BIO2015-67930-R, Regional Government of Madrid Grant S2013/MlT-2807, and a Training of University Professors fellowship from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Research (N.R.).

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains a supplement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Skipski V. P., Barclay M., Reichman E. S., and Good J. J.. 1967. Separation of acidic phospholipids by one-dimensional thin-layer chromatography. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 137: 80–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skipski V. P., Peterson R. F., and Barclay M.. 1964. Quantitative analysis of phospholipids by thin-layer chromatography. Biochem. J. 90: 374–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skipski V. P., Peterson R. F., Sanders J., and Barclay M.. 1963. Thin-layer chromatography of phospholipids using silica gel without calcium sulfate binder. J. Lipid Res. 4: 227–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allan D., and Cockcroft S.. 1982. A modified procedure for thin-layer chromatography of phospholipids. J. Lipid Res. 23: 1373–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weerheim A. M., Kolb A. M., Sturk A., and Nieuwland R.. 2002. Phospholipid composition of cell-derived microparticles determined by one-dimensional high-performance thin-layer chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 302: 191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilfillan A. M., Chu A. J., Smart D. A., and Rooney S. A.. 1983. Single plate separation of lung phospholipids including disaturated phosphatidylcholine. J. Lipid Res. 24: 1651–1656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scarim J., Ghanbari H., Taylor V., and Menon G.. 1989. Determination of phosphatidylcholine and disaturated phosphatidylcholine content in lung surfactant by high performance liquid chromatography. J. Lipid Res. 30: 607–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cernansky G., Liau D. F., Hashim S. A., and Ryan S. F.. 1980. Estimation of phosphatidylglycerol in fluids containing pulmonary surfactant. J. Lipid Res. 21: 1128–1131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwamori M., Hirota K., Utsuki T., Momoeda K., Ono K., Tsuchida Y., Okumura K., and Hanaoka K.. 1996. Sensitive method for the determination of pulmonary surfactant phospholipid/sphingomyelin ratio in human amniotic fluids for the diagnosis of respiratory distress syndrome by thin-layer chromatography-immunostaining. Anal. Biochem. 238: 29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall S. B., Wang Z., and Notter R. H.. 1994. Separation of subfractions of the hydrophobic components of calf lung surfactant. J. Lipid Res. 35: 1386–1394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai M. Y., and Marshall J. G.. 1979. Phosphatidylglycerol in 261 samples of amniotic fluid from normal and diabetic pregnancies, as measured by one-dimensional thin-layer chromatography. Clin. Chem. 25: 682–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spillman T., Cotton D. B., and Golunski E.. 1988. Detection frequency by thin-layer chromatography of phosphatidylglycerol in amniotic fluid with clinically functional pulmonary surfactant. Clin. Chem. 34: 1976–1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitnick M., DeMarco B., and Gibbons J. M.. 1980. Amniotic fluid phosphatidylglycerol and phosphatidylinositol separated by stepwise-development thin-layer chromatography. Clin. Chem. 26: 277–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Possmayer F., Yu S. H., Weber J. M., and Harding P. G.. 1984. Pulmonary surfactant. Can. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 62: 1121–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klaus M. H., Clements J. A., and Havel R. J.. 1961. Composition of surface-active material isolated from beef lung. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 47: 1858–1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creuwels L. A., van Golde L. M., and Haagsman H. P.. 1997. The pulmonary surfactant system: biochemical and clinical aspects. Lung. 175: 1–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuroki Y., and Akino T.. 1991. Pulmonary surfactant protein A (SP-A) specifically binds dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine. J. Biol. Chem. 266: 3068–3073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wattiez R., Hermans C., Bernard A., Lesur O., and Falmagne P.. 1999. Human bronchoalveolar lavage fluid: two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, amino acid microsequencing and identification of major proteins. Electrophoresis. 20: 1634–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olmeda B., Umstead T. M., Silveyra P., Pascual A., Lopez-Barneo J., Phelps D. S., Floros J., and Perez-Gil J.. 2014. Effect of hypoxia on lung gene expression and proteomic profile: insights into the pulmonary surfactant response. J. Proteomics. 101: 179–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pérez-Gil J., Cruz A., and Casals C.. 1993. Solubility of hydrophobic surfactant proteins in organic solvent/water mixtures. Structural studies on SP-B and SP-C in aqueous organic solvents and lipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1168: 261–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taeusch H. W., Bernardino de la Serna J., Perez-Gil J., Alonso C., and Zasadzinski J. A.. 2005. Inactivation of pulmonary surfactant due to serum-inhibited adsorption and reversal by hydrophilic polymers: experimental. Biophys. J. 89: 1769–1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bligh E. G., and Dyer W. J.. 1959. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37: 911–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Udenfriend S., Stein S., Bohlen P., Dairman W., Leimgruber W., and Weigele M.. 1972. Fluorescamine: a reagent for assay of amino acids, peptides, proteins, and primary amines in the picomole range. Science. 178: 871–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curstedt T., Johansson J., Persson P., Eklund A., Robertson B., Lowenadler B., and Jornvall H.. 1990. Hydrophobic surfactant-associated polypeptides: SP-C is a lipopeptide with two palmitoylated cysteine residues, whereas SP-B lacks covalently linked fatty acyl groups. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 87: 2985–2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roch A., Guervilly C., and Papazian L.. 2011. Fluid management in acute lung injury and ards. Ann. Intensive Care. 1: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matthay M. A., and Zemans R. L.. 2011. The acute respiratory distress syndrome: pathogenesis and treatment. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 6: 147–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grek C. L., Newton D. A., Spyropoulos D. D., and Baatz J. E.. 2011. Hypoxia up-regulates expression of hemoglobin in alveolar epithelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 44: 439–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rankin J. A., Naegel G. P., Schrader C. E., Matthay R. A., and Reynolds H. Y.. 1983. Air-space immunoglobulin production and levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of normal subjects and patients with sarcoidosis. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 127: 442–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reynolds H. Y., Fulmer J. D., Kazmierowski J. A., Roberts W. C., Frank M. M., and Crystal R. G.. 1977. Analysis of cellular and protein content of broncho-alveolar lavage fluid from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. J. Clin. Invest. 59: 165–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindahl M., Ekstrom T., Sorensen J., and Tagesson C.. 1996. Two dimensional protein patterns of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from non-smokers, smokers, and subjects exposed to asbestos. Thorax. 51: 1028–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson M. E., O’Brien-Ladner A. R., and Wesselius L. J.. 1996. Regional variation in iron and iron-binding proteins within the lungs of smokers. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 153: 1353–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas H. V., Mueller P. K., and Lyman R. L.. 1968. Lipoperoxidation of lung lipids in rats exposed to nitrogen dioxide. Science. 159: 532–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghio A. J., Turi J. L., Madden M. C., Dailey L. A., Richards J. D., Stonehuerner J. G., Morgan D. L., Singleton S., Garrick L. M., and Garrick M. D.. 2007. Lung injury after ozone exposure is iron dependent. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 292: L134–L143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roehm J. N., Hadley J. G., and Menzel D. B.. 1971. Antioxidants vs lung disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 128: 88–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holm B. A., Notter R. H., Siegle J., and Matalon S.. 1985. Pulmonary physiological and surfactant changes during injury and recovery from hyperoxia. J. Appl. Physiol. 59: 1402–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robbins C. G., Davis J. M., Merritt T. A., Amirkhanian J. D., Sahgal N., Morin F. C. 3rd, and Horowitz S.. 1995. Combined effects of nitric oxide and hyperoxia on surfactant function and pulmonary inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. 269: L545–L550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naito Y., Hosokawa M., Sawada H., Oboshi M., Hirotani S., Iwasaku T., Okuhara Y., Morisawa D., Eguchi A., Nishimura K., et al. 2016. Transferrin receptor 1 in chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling. Am. J. Hypertens. 29: 713–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.