Abstract

Background Patients with non- or minimally displaced distal radial fractures, that do not need repositioning, are mostly treated by a short-arm cast for a period of 4 to 6 weeks. A shorter period of immobilization may lead to a better functional outcome.

Purpose We conducted a randomized controlled trial to evaluate whether the duration of cast immobilization for patients with non- or minimally displaced distal radial fractures can be safely shortened toward 3 weeks.

Materials and Methods The primary outcomes were patient-reported outcomes measured by the Patient-Related Wrist Evaluation (PRWE) and Quick Disability of Arm, Shoulder and Hand (QuickDASH) score after 1-year follow-up. Secondary outcome measures were: PRWE and QuickDASH earlier in follow-up, pain (Visual Analog Scale), and complications like secondary displacement.

Results Seventy-two patients (male/female, 23/49; median age, 55 years) were included and randomized. Sixty-five patients completed the 1-year follow-up. After 1-year follow up, patients in the 3 weeks immobilization group had significantly better PRWE (5.0 vs. 8.8 points, p = 0.045) and QuickDASH scores (0.0 vs. 12.5, p = 0.026). Secondary displacement occurred once in each group. Pain did not differ between groups ( p = 0.46).

Conclusion Shortening the period of immobilization in adult patients with a non- or minimally displaced distal radial fractures seems to lead to equal patient-reported outcomes for both the cast immobilization groups. Also, there are no negative side effects of a shorter period of cast immobilization. Therefore, we recommend a period of 3 weeks of immobilization in patients with distal radial fractures that do not need repositioning.

Keywords: conservative treatment, distal radial fractures, wrist fractures, immobilization period

Distal radial fractures (DRF) account for up to 20% of all extremity fractures. 1 Optimal treatment is important, as the injury-related loss of function in the wrist can lead to occupational disability, decreased school attendance, lost work hours, loss of independence, and lasting disability as well as significant medical costs. 2 3 Most patients with non- or minimally displaced DRF can be treated nonoperatively with short-arm cast immobilization alone, with excellent functional results. 4 5

Current practice is a short-arm cast for 4 to 6 weeks. 2 6 Previous results might suggest that a shorter period of immobilization could be safe, and may accelerate and enhance functional recovery. 7 8 9 10

Some authors believe that 3 weeks of cast immobilization could be sufficient. 7 8 It is even stated that nondisplaced DRF do not need stabilization by cast immobilization at all, perhaps only for pain relief. 9 11 Most DRF are at risk to displace within the first 2 weeks; only 7 to 8% displace after this time period. 11 12 13

To assess the clinical controversy of the duration of the immobilization period, we conducted a randomized controlled trial. Three weeks of short-arm cast immobilization was compared with the mean regular period of immobilization of 5 weeks in adult patients with non- or minimally displaced DRF. We hypothesize that 3 weeks of cast immobilization lead to better patient-reported outcomes after 1 year compared with 5 weeks of cast immobilization and that this treatment does not lead to more complications.

Materials and Methods

Three weeks of short-arm cast immobilization was compared with 5 weeks of short-arm cast immobilization in adult patients with non- or minimally displaced DRF. Only stable fractures were included in this study. Potential unstable fractures like Smith fractures and displaced fractures were excluded. In the DRF included in the study, no reduction, manipulation of the fracture, or molding of the cast was performed. Criteria for minimal displacement were based on the Lindstrom's criteria: dorsal angulation < 15°, volar tilt < 20°, radial inclination < 15°, ulnar variance < 5 mm, and an articular step-off < 2 mm. 14

Inclusion Criteria

Age > 18 years.

Non- or minimal displaced DRF.

Exclusion Criteria

Fracture of the contralateral arm.

Preexistent abnormalities of the fractured distal radius.

Open fractures.

Fractures with associated instability (e.g., displaced and reduced fractures and Smith fractures).

Randomization, Blinding, and Follow-Up

Patients were informed about this study at the emergency department, after checking the above-mentioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. After obtaining informed consent, patients were randomized into the intervention group (3 weeks short-arm cast immobilization) or in the control group (5 weeks short-arm cast immobilization). Permuted block randomization using a computer-generated randomization schedule was used. To prevent bias, stratification by age (< 60 or ≥ 60 years of age) and gender was performed.

As there is no evidence that the type of cast or removal of the cast has any impact on redisplacement, we chose to treat all patients in a short-arm cast in neutral position. 15 16 After 3 or 5 weeks, according to the randomization, the cast was removed. After the cast immobilization period, all patients were treated according to the after-treatment protocol: Patients were motivated to start mobilization directly after removal of the cast. Physiotherapy was not generally advised. None of the patients received a resting splint after cast removal. Follow-up was performed at the outpatient clinic at 1 week, 3 or 5 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year after the initial trauma. At these points, an X-ray was performed to determine secondary displacement. The ethical committee approved the protocol.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome of this study was patient-reported outcome, measured by the Patient-Related Wrist Evaluation (PRWE) and Quick Disability of Arm, Shoulder and Hand (QuickDASH) score after 1-year follow-up. The PRWE is a questionnaire to evaluate the patient-reported outcome in patients with disorders of the wrist. The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of the PRWE is 11.5 points. Pain and function are scored on a 0 to 10 scale, summed to a score between 0 and 100, with 0 being the best possible outcome and 100 the worst. 17 18 The QuickDASH score is another questionnaire to evaluate patients with disorders involving the joints of the upper limb, with a MCID of 14 points between groups. Patients can score pain and functional outcome on a 1 to 5 scale, where 1 is the best possible outcome and 5 the worst. The total sum will be counted and converted by a formula resulting in a 0 to 100 score, where 0 is the best possible outcome and 100 the worst. 19 20

Secondary outcome measures were: PRWE and QuickDASH at 6 and 12 weeks and 6 months, pain (Visual Analog Scale [VAS]) measured by a pain diary, and complications such as complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), mal- or nonunion, and secondary displacement.

Power Analysis

The primary outcomes were PRWE and QuickDASH score after 1 year. The MCID of the QuickDASH score is 14 points. 19 Based on a difference of 14 points, a sample size of 30 patients per treatment group was calculated with a power (1– β ) of 80% and a type I error ( α ) of 5%, allowing a 10% drop-out. In total, 72 patients should be included in the study, 36 in each group.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive analysis was performed to compare baseline characteristics. For continuous data, the mean and standard deviation for parametric data or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for nonparametric data were calculated. To determine whether differences between the two groups were significant, we log transformed the outcomes if the data were not normally distributed and we used linear regression analyses. Adjustments were made for age and gender. A p -value of < 0.05 was taken as the threshold of statistical significance.

Results

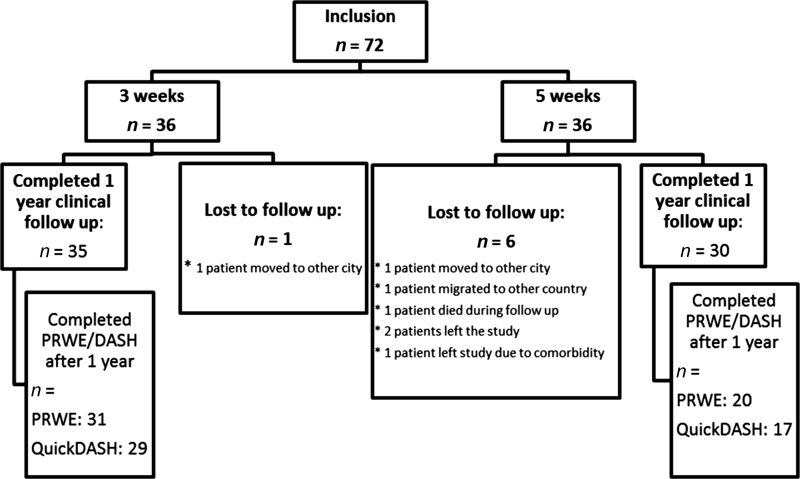

A total of 72 patients were included in this study, 36 in each group. Baseline characteristics of these patients are displayed in Table 1 . Seven patients were lost to follow-up and another 19 patients had incomplete QuickDASH or PRWE scores after 1 year. This is shown in Fig. 1 .

Table 1. Group characteristics.

| N | 3 weeks immobilization |

5 weeks immobilization |

Total | p- Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 10 | 13 | 23 | 0.61 |

| Female | 26 | 23 | 49 | |

| < 60 y | 21 | 18 | 39 | 0.64 |

| > 60 y | 15 | 18 | 33 | |

| Intra-articular | 19 | 19 | 38 | 0.61 |

| Extra-articular | 16 | 11 | 27 | |

| Total | 36 | 36 | 72 | |

| Median age | 52.6 IQR, 27.7–68.8 |

59.44 IQR, 48.4–66.5 |

55.29 IQR, 40.4–67.4 |

0.19 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; y, years of age.

Note: Baseline characteristics of the 72 randomized patients.

Fig. 1.

Number of inclusion, follow-up.

Primary Outcome

After completing the follow-up at 1 year, the intervention group (3 weeks cast immobilization) had statistically better functional outcome, as shown in Table 2 . The median PRWE after 1 year was better in the 3-week group, 5.0 (IQR: 0–12.5) versus 8.8 (IQR: 1.7–23.5) in the 5-week group ( p = 0.045). The median QuickDASH score after 1 year was 0 (IQR: 0–6.8) in the 3-week group compared with 12.5 (IQR: 2.8–27.0) in the 5-week group ( p = 0.026). Nevertheless, both the PRWE and the QuickDASH did not reach the MCIDs of 11.5 and 14 points.

Table 2. Results, primary, and secondary outcomes.

| Variables | Value | 3 weeks | IQR | 5 weeks | IQR | Difference | p -Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||||||

| Function 1 year | |||||||

| PRWE, n = 51 | 0–100 | 5.0, n = 31 | 0–12.5 | 8.8, n = 20 | 1.7–23.5 | 3.8 | 0.045 |

| QuickDASH, n = 46 | 0–100 | 0.0, n = 29 | 0–6.8 | 12.5, n = 17 | 2.8–27.0 | 12.5 | 0.026 |

| Secondary outcome | |||||||

| Function, 6 weeks | |||||||

| PRWE, n = 54 | 0–100 | 20.0, n = 32 | 8.4–50.3 | 30.7, n = 22 | 17.4–57.6 | 10.7 | 0.32 |

| QuickDASH, n = 48 | 0–100 | 13.6, n = 27 | 0–45.4 | 22.4, n = 21 | 0–39.5 | 8.8 | 0.74 |

| Function, 12 weeks | |||||||

| PRWE, n = 42 | 0–100 | 10.0, n = 22 | 0.7–42.9 | 24.3, n = 20 | 12.9–34.5 | 14.3 | 0.054 |

| QuickDASH, n = 39 | 0–100 | 14.7, n = 20 | 0.6–27.4 | 20.5, n = 19 | 6.8–29.5 | 5.8 | 0.34 |

| Function, 6 months | |||||||

| PRWE, n = 26 | 0–100 | 9.5, n = 14 | 1.5–24.7 | 8.3, n = 12 | 0.9–22.9 | –1.2 | 0.33 |

| QuickDASH, n = 23 | 0–100 | 4.5, n = 14 | 0–24.3 | 4.5, n = 9 | 1.1–23.9 | 0 | 0.95 |

| Median VAS | 0–10 | 3.1, n = 25 | 1–4.8 | 2.6, n = 21 | 0.5–4.2 | –0.5 | 0.46 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; PRWE, Patient-Related Wrist Evaluation; QuickDASH, Quick Disability of Arm, Shoulder and Hand; VAS, Visual Analog Scale.

Note: Primary outcome: QuickDASH and PRWE score after 1 year. Secondary outcome: QuickDASH and PRWE score after 6 and 12 weeks and 6 months and median VAS after removal of the cast.

Secondary Outcome

In Table 2 , the results of functional outcome after 6 and 12 weeks and 6 months for both groups are listed. Although patients who were treated with 3 weeks of cast immobilization showed better results (except for PRWE score at 6 months), the difference between the groups was not statistically significant.

After cast removal, patients in the 3-week cast immobilization group did not mention to suffer more pain compared with the control group. Median VAS in the 3-week cast group was 3.1 (IQR: 1.0–4.8) and 2.6 in the 5-week group (IQR: 0.5–4.2), respectively ( p = 0.46).

During the study period, there were no complications in fracture healing. In both groups, no cases of nonunion or CRPS were noted. In both groups, one patient showed minimal secondary displacement of the DRF according to the Lindstrom's criteria. 14 However, both patients did not need surgical treatment or reduction of the fracture because of good patient-reported outcome.

Discussion

In this randomized controlled trial, we evaluated whether the duration of immobilization period in patient with non- or minimally displaced DRFs could be safely reduced to 3 weeks. This study showed that shortening the period of cast immobilization is safe in these patients. A higher rate of possible complications that might occur after earlier cast removal, such as an increased number of secondary displacements of the fractures or increased pain sensation, was not found in this study.

Although a statistically significant difference in patient-reported outcome after 1 year in favor of the 3-week immobilization group was found, the MCID for both PRWE and QuickDASH was not reached. There was no significant difference during the follow-up at 6 and 12 weeks and 6 months. We do not have a clear explanation for the statistical differences between the patient-reported outcomes after 1 year, but this study has some limitations. Sixty-five patients completed 1 year of clinical follow-up, and only 7 patients were lost to follow-up. However, only 46 patients (64%) completed all the PRWE and QuickDASH scores ( Fig. 1 ). Some patients were lost to follow-up and others were not motivated to participate anymore. As shown in Fig. 1 , more patients were lost to follow-up in the 5-week immobilization group. Furthermore, in this group less patients completed the questionnaires after 1 year. However, it is not totally clear why this was the case. One might assume that the patients in the 5-week immobilization group were less motivated to participate in this study and complete the questionnaires, because they received the regular period of immobilization. It is also possible that patients did not return to follow-up after 1 year, because they were free of complaints and recovered uneventful. Though, it is to be expected that patients who were not fully recovered would visit the clinic on their scheduled appointments. Therefore, one can assume that the functional outcome of the patients lost to follow-up was at least equal to the patients who were not lost to follow-up. Although only a drop-out of 10% was anticipated in the power analyses, 33% of initially randomized patients did not complete the PRWE and QuickDASH score after 1 year. The data of patients who did not complete the study of 1-year follow-up were considered as random missing data and therefore only the available data were analyzed and the number of available questionnaires is shown in Table 3 .

Table 3. Follow-up: Number of patients.

| Total | 3 weeks cast immobilization | 5 weeks cast immobilization | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % start | N | % start | |

| Randomization | 72 | 100 | 36 | 100 | 36 | 100 |

| Lost to follow-up | 6 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 14 |

| Completed 1 year clinical follow-up | 65 | 90 | 35 | 97 | 30 | 83 |

| Completed 1 year follow-up: | ||||||

| PRWE | 51 | 71 | 31 | 86 | 20 | 56 |

| QuickDASH | 46 | 64 | 29 | 81 | 17 | 47 |

| Completed follow-up with PRWE/QuickDASH scores | ||||||

| 6 weeks | ||||||

| PRWE | 54 | 75 | 32 | 89 | 22 | 61 |

| QuickDASH | 48 | 67 | 27 | 75 | 21 | 58 |

| 12 weeks | ||||||

| PRWE | 42 | 58 | 22 | 61 | 20 | 56 |

| QuickDASH | 39 | 54 | 20 | 56 | 19 | 53 |

| 6 months | ||||||

| PRWE | 26 | 36 | 14 | 39 | 12 | 33 |

| QuickDASH | 23 | 32 | 14 | 39 | 9 | 25 |

| 1 year | ||||||

| PRWE | 51 | 71 | 31 | 86 | 20 | 56 |

| QuickDASH | 46 | 64 | 29 | 81 | 17 | 47 |

Abbreviations: PRWE, Patient-Related Wrist Evaluation; QuickDASH, Quick Disability of Arm, Shoulder and Hand.

Note: Total patients included in study = 72. Lost to follow-up = 6, completed PRWE/QuickDASH after 1 year = 51/46.

The difference in functional outcome was measured using PRWE and QuickDASH; both are scores specific for functional outcome of the upper extremities. PRWE is the most responsive instrument for evaluating patient-reported outcome of DRF. 17 The QuickDASH is considered to be the most appropriate instrument for evaluating patients with disorders involving the joints of the upper limb. 19

In this study, the PRWE and QuickDASH score were used to analyze a homogenous group of patients, with nondisplaced DRF.

At present, the majority of DRF are treated nonoperatively. Also, there has been a dramatic rise in open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF). 16 21 Nevertheless, whether long-term outcomes after ORIF are superior to nonoperative treatment is still a matter of debate. 3 15 The complication rate of nonoperative treatment of DRF is 0 to 13.5%. 22 23 24 The overall complication rate after ORIF is 16.5%, with 7.7% major complications being hardware failure, tendon rupture, or carpal tunnel syndrome. 25 According to the literature, the complication rate of Kirschner wiring is even higher: 26 to 28%. 26 27

As surgical treatment is associated with considerable risks, it should only be recommended to those patients for whom there is a risk that nonoperative treatment could lead to unsatisfactory functional result, for example, in case of secondary displacement. 28

In this study, we examined only patients with non- or minimally displaced (stable) DRF. As these patients do not suffer significant displacement, there is no need for ORIF. Besides, it is thought that ORIF in these patients will not speed up the recovering process compared with an immobilization period of 3 weeks. Instable fractures as displaced and reduced DRF and Smith fractures were excluded from this study.

The results of this study are in accordance with the existing literature on this topic. The big difference is that in this study a homogenous group of patients with stable non- or minimally displaced DRF were included. A prospective study for conservative treatment of DRF with non- or minimal displacement concluded that 3- and 5-week cast immobilization leads to equally good results. The functional outcome was measured by the Gartland and Werley functional score. 7

A study in patients who underwent reduction of their displaced DRF followed by cast immobilization showed comparable range of motion 1 year after initial 3 or 5 weeks' cast immobilization. Patients who received 3 weeks immobilization after reduction experienced less pain and had improved grip strength compared with the 5 weeks immobilization group. 10 In this study, the Gartland and Werley functional score was used to assess functional outcome. This score provides an assessment of the functional outcome, amount of pain, strength, and time to union. We did not use the Gartland and Werley functional test as its use has not been validated.

Others assessed outcome following cast immobilization of both nondisplaced as well as severely displaced DRF. 29 30 Functional outcome seems to be good in both studies. Although patients were not randomized, different periods of cast immobilization for nondisplaced and displaced DRF were used, as well as different types of casts. Therefore, we were not able to extrapolate these results to the results of our study.

The most important conclusion to be drawn from our study is that earlier cast removal will not lead to more complications like secondary displacement or more pain. Besides, patient-reported outcomes seem to be at least equal in both the 3 and 5 weeks cast immobilization groups. Therefore, we recommend that cast immobilization for non- or minimally displaced DRF can be safely discontinued after 3 weeks.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Karlijn van Stralen for the statistical support.

Funding Statement

Funding None.

Conflict of Interest None.

Trial Registration

METC- registratie: M011–059

CCMO-registratie: NL38449 09 11.

Ethical Approval

The article has been written in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. The Medical Ethical Committee of Noord-Holland has approved the study protocol and informed consent of all patients has been obtained. The confirmation letter of the ethical committee will be submitted as well.

Note

This study was conducted at the Department of Trauma Surgery, Spaarne Gasthuis, Spaarnepoort 1, 2143 TM, Hoofddorp, The Netherlands.

A. Bentohami and E. A. K. van Delft contributed equally to the research project and manuscript and therefore share the first authorship .

References

- 1.Meena S, Sharma P, Sambharia A K, Dawar A. Fractures of distal radius: an overview. J Family Med Prim Care. 2014;3(04):325–332. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.148101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Einsiedel T, Becker C, Stengel D et al. Fracturen der oberen Extremität beim geriatrischen Patienten, Harmlose Monoverletzung oder Ende der Selbständigkeit? Z Gerontol Geriat. 2006;39:451–461. doi: 10.1007/s00391-006-0378-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nellans K W, Kowalski E, Chung K C. The epidemiology of distal radius fractures. Hand Clin. 2012;28(02):113–125. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beumer A, McQueen M M. Fractures of the distal radius in low-demand elderly patients: closed reduction of no value in 53 of 60 wrists. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003;74(01):98–100. doi: 10.1080/00016470310013743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anzarut A, Johnson J A, Rowe B H, Lambert R G, Blitz S, Majumdar S R. Radiologic and patient-reported functional outcomes in an elderly cohort with conservatively treated distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29(06):1121–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldfarb C A, Yin Y, Gilula L A, Fisher A J, Boyer M I. Wrist fractures: what the clinician wants to know. Radiology. 2001;219(01):11–28. doi: 10.1148/radiology.219.1.r01ap1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christensen O M, Christiansen T G, Krasheninnikoff M, Hansen F F. Length of immobilisation after fractures of the distal radius. Int Orthop. 1995;19(01):26–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00184910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vang Hansen F, Staunstrup H, Mikkelsen S. A comparison of 3 and 5 weeks immobilization for older type 1 and 2 Colles' fractures. J Hand Surg [Br] 1998;23(03):400–401. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(98)80067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen M R, Andersen K H, Jensen C H. Management of undisplaced or minimally displaced Colles' fracture: one or three weeks of immobilization. Orthop Sci. 1997;2(06):424–427. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McAuliffe T B, Hilliar K M, Coates C J, Grange W J. Early mobilisation of Colles' fractures. A prospective trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69(05):727–729. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.69B5.3316238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbaszadegan H, von Sivers K, Jonsson U. Late displacement of Colles' fractures. Int Orthop. 1988;12(03):197–199. doi: 10.1007/BF00547163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solgaard S. Early displacement of distal radius fracture. Acta Orthop Scand. 1986;57(03):229–231. doi: 10.3109/17453678608994383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solgaard S. Function after distal radius fracture. Acta Orthop Scand. 1988;59(01):39–42. doi: 10.3109/17453678809149341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lidström A. Fractures of the distal end of the radius. A clinical and statistical study of end results. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1959;41:1–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diaz-Garcia R J, Chung K C. Common myths and evidence in the management of distal radius fractures. Hand Clin. 2012;28(02):127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster B D, Sivasundaram L, Heckmann N, Pannell W C, Alluri R K, Ghiassi A. Distal Radial fractures do not displace following splint or cast removal in the acute, postreduction period: a prospective observational study. J Wrist Surg. 2017;6(01):54–59. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1588006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacDermid J C, Turgeon T, Richards R S, Beadle M, Roth J H. Patient rating of wrist pain and disability: a reliable and valid measurement tool. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12(08):577–586. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199811000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walenkamp M M, de Muinck Keizer R J, Goslings J C, Vos L M, Rosenwasser M P, Schep N W. The minimum clinically important difference of the Patient-rated Wrist Evaluation Score for patients with distal radius fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(10):3235–3241. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4376-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gummesson C, Ward M M, Atroshi I. The shortened disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire (QuickDASH): validity and reliability based on responses within the full-length DASH. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-7-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sorensen A A, Howard D, Tan W H, Ketchersid J, Calfee R P. Minimal clinically important differences of 3 patient-rated outcomes instruments. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(04):641–649. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mann F A, Wilson A J, Gilula L A. Radiographic evaluation of the wrist: what does the hand surgeon want to know? Radiology. 1992;184(01):15–24. doi: 10.1148/radiology.184.1.1609073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arora R, Lutz M, Deml C, Krappinger D, Haug L, Gabl M. A prospective randomized trial comparing nonoperative treatment with volar locking plate fixation for displaced and unstable distal radial fractures in patients sixty-five years of age and older. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(23):2146–2153. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gong H S, Lee J O, Huh J K, Oh J H, Kim S H, Baek G H. Comparison of depressive symptoms during the early recovery period in patients with a distal radius fracture treated by volar plating and cast immobilisation. Injury. 2011;42(11):1266–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ward C M, Kuhl T L, Adams B D. Early complications of volar plating of distal radius fractures and their relationship to surgeon experience. Hand (NY) 2011;6(02):185–189. doi: 10.1007/s11552-010-9313-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bentohami A, de Burlet K, de Korte N, van den Bekerom M PJ, Goslings J C, Schep N W. Complications following volar locking plate fixation for distal radial fractures: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2014;39(07):745–754. doi: 10.1177/1753193413511936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McFadyen I, Field J, McCann P, Ward J, Nicol S, Curwen C. Should unstable extra-articular distal radial fractures be treated with fixed-angle volar-locked plates or percutaneous Kirschner wires? A prospective randomised controlled trial. Injury. 2011;42(02):162–166. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.07.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rozental T D, Blazar P E, Franko O I, Chacko A T, Earp B E, Day C S. Functional outcomes for unstable distal radial fractures treated with open reduction and internal fixation or closed reduction and percutaneous fixation. A prospective randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(08):1837–1846. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Einsiedel T, Freund W, Sander S, Trnavac S, Gebhard F, Kramer M. Can the displacement of a conservatively treated distal radius fracture be predicted at the beginning of treatment? Int Orthop. 2009;33(03):795–800. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0568-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dias J J, Wray C C, Jones J M, Gregg P J. The value of early mobilisation in the treatment of Colles' fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69(03):463–467. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.69B3.3584203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Millett P J, Rushton N. Early mobilization in the treatment of Colles' fracture: a 3 year prospective study. Injury. 1995;26(10):671–675. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(95)00146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]