Abstract

Introduction:

Genetic and environmental factors are involved in the incidence of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Many reports confirm that several common genes are connected with these two psychotic disorders. Several neurotransmitters may be involved in the molecular mechanisms of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. We aimed to estimate the role of two talent genes: DAOA in neurotransmission of glutamate and COMT in neurotransmission of dopamine to guide the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Methods:

Blood samples (n=100 for schizophrenia, n=100 for bipolar I disorder and n=127 for case control) were collected from individuals unrelated in the southwest of Iran. The SNPs (rs947267 and rs3918342 for DAOA gene/rs165599 and rs4680 for COMT gene) were genotyped using the PCR-RFLP method. Our finding was studied by logistic regression and Mantel-Haenszel Chi-square tests.

Results:

We observed an association in rs3918342, rs165599 and rs4680 single nucleotide polymorphisms and schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. In addition, our data demonstrated that the rs947267 was related to bipolar I disorder but there was no association between this SNP and schizophrenia.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, this result supports the hypothesis that variations in DAOA and COMT genes may play a role in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Keywords: Catechol-O-methyltransferase, D-amino acid oxidase activator, Genetics, Schizophrenic disorders, Bipolar disorder

Highlights

This is the first study that examines the association of the rs1656688 and rs4680 of COMT gene and rs947267 and rs3918342 of DAOA gene in Iranian population.

The present study aimed to extensively evaluate the contribution of DAOA and COMT genes in susceptibility to schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder.

Our data provided further evidence that the DAOA locus or COMT locus may contribute in the pathophysiology of psychotic disorders.

Plain Language Summary

Schizophrenia is a serious mental illness that interferes with the person’s ability to think clearly, manage emotions, make decisions and relate to others. Bipolar disorder is a brain disorder that causes unusual shifts in mood, energy, activity levels, and the ability to carry out day-to-day tasks. Studies have shown that these ailments are affected by genetic and environmental factors. DAOA and COMT genes are two potential candidates for involvement in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder molecular mechanisms. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the role of these genes in order to improve the present treatments for these illnesses. For this purpose, the association of four desired positions with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder was investigated. The results showed that three of these positions were associated with both diseases and one position was associated with bipolar I. Thus, there are possibilities for DAOA and COMT genes variations to be involved in schizophrenia and bipolar I disorders.

1. Introduction

Schizophrenia (SCZ) is a serious mental disorder that approximately 1% of the world’s population suffer from it (Yue et al., 2007). SCZ is characterized by delusions, hallucinations, thought disorders and cognitive deficits (Rees, O’Donovan, & Owen, 2015). Bipolar Disorder (BD) presents with diverse clinical manifestations. It is characterized by episodes of mania or hypomania. It usually categorized into Bipolar I Disorder (BID) and Bipolar II Disorder (BIID). BID is mainly characterized by depressive and manic symptoms. Moreover, patients may experience psychotic features like delusion and hallucination. These patients usually have the indication for residential treatment (Holtzman, Lolich, Ketter, & Vázquez, 2015).

Family, twin and adoption studies uniquely illustrate the role of genetic agents in transition of SCZ and BD (Boks et al., 2007). The heritability estimates of SCZ and BD are 80% (Aleman, Kahn, & Selten, 2003) and 80%–90%, respectively (Leahy, 2007). Several neurotransmitters such as glutamate (Nasirizade, Mostofi, & Shahbazi, 2016), dopamine, GABA (Rahmanzade et al., 2017) (Dehghani, & Shahbazi, 2016), and serotonin engage in the molecular mechanisms of SCZ and BD (Austin, 2005). Dopamine is an inhibitory neurotransmitter and glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter, involved in a variety of neural processes (Goff & Coyle, 2001). The dopamine and glutamate hypotheses are leading theories of the pathoaetiology of SCZ (Howes, McCutcheon, & Stone, 2015).

Neurobiological linkage and association studies suggest that the susceptibility genes in SCZ and BD can be divided into 2 main classes. The first class genes (DAOA, NRG1, DISC1, dysbindin and GRM3) affect the NMDA glutamate receptor. The second class genes which include COMT, DRD2 and PPP1R1B are involved in dopamine metabolism and signaling (Harrison & Weinberger, 2005). DAOA gene (13q34) and COMT gene (22q11) are not only associated with psychotic disorders, but also play a key role in glutamatergic and dopaminergic neurotransmissions (Ross, Margolis, Reading, Pletnikov, & Coyle, 2006).

Chumakov et al. (2002) identified DAOA gene (D-amino acid oxidase activator). The DAOA protein functions as an activator of DAAO (D-amino-acid oxidase). DAAO gene (12q24) oxidizes D-serine which is a potent activator of N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA). NMDA receptor is a postsynaptic Glutamate Receptor (GluRs) in the human brain (Maderia, Freitas, Vargas-Lopes, Wolosker, & Panizzutti, 2008). Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter, involved in a variety of neural activities including synaptic flexibility, neuronal development, and neuronal toxicity (Goff & Coyle, 2001). Normal glutamatergic neurotransmission involves enzymes, pre- and post-synaptic neurons, glial cells, glutamate receptors and transporters. Disruption in any of the items may interrupt normal glutamatergic neurotransmission (Meador-Woodruff & Healy, 2000).

DAOA and DAAO genes interact in the NMDA receptor regulation pathway in SCZ and BD. “Glutamate hypothesis” derived from NMDA antagonists like Phencyclidine (PCP) and ketamine can cause psychotic and cognitive abnormalities in SCZ (Ross et al., 2006). Likewise, “dopamine hypothesis” originated from the identification of D2 receptor blockage. The mechanism of action is similar in D2 receptor blockage and antipsychotics (Dashti, Aboutaleb, & Shahbazi, 2013). Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) is a unique enzyme for decomposing a number of bioactive molecules like dopamine. This enzyme is encoded by the COMT gene (Lotta et al., 1995).

COMT gene is located in 22q11, a region that is a source of confusion in many linkage analysis (Lewis et al., 2003). Deletions in 22q11 can also lead to the velocardiofacial syndrome through an increased risk of psychopathy (Karayiorgou et al., 1995). Not all studies have supported the DAOA and COMT genes association with SCZ and BD (Liu et al. 2006; Shi, Badner, Gershon, & Liu, 2008; Tan et al., 2014; Jagannath et al. 2017); however, genome wide association studies of DAOA and COMT genes with SCZ and BD are available (Shifman et al., 2002; Glatt, Faraone, & Tsuang, 2003; Shifman et al., 2004; Sacchetti et al., 2013; Gatt, Burton, Williams, & Schofield, 2015); Chu et al., 2017; Jagannath, Gerstenberg Correll, Walitza, & Grünblatt, 2018). We postulated the genetic variation of DAOA gene in glutamate neurotransmission and COMT gene in dopamine neuro-transmission, to facilitate the treatment of SCZ and BD. We also assessed the impact of those on susceptibility for SCZ and BD.

2. Methods

2.1. Sampling

To collect the study samples, we used General Health Questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28) (Lobo, Perez-Echeverria, & Artal, 1986) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). The patients were attended by at least 2 psychiatrists since admission. All the patients were treated with mood stabilizers or antipsychotics, during the study period. The control group consisted of 127 non-relative individuals who were screened in 2 steps.

First, they were asked whether their first and second degree relatives have a history of at least one of the following problems: taking mental health medications, referral to a psychiatrist or psychologist, psychiatric hospitalization, substance abuse or dependence, and suicide attempts. Second, the screening was completed by General Health Questionnaire. There was no remarkable diversity in gender distribution among the cases and controls (55%, 67% and 47% of the controls, SCZ patients and BD patients were males, respectively). The controls, BD patients and SCZ patients had Mean±SD age of 37.6±9.6, 34.4±11.2 and 36.9±10.2 years, respectively.

2.2. DNA extraction

Blood samples (n=127 for the controls, n=100 for schizophrenia and n=100 for BID) were collected from non-relative individuals in the southwest of Iran. The total genomic DNA was extracted from the leukocytes using Diatom DNA Prep extraction kit (Gene Fanavaran, Iran), based on the structures. A spectrophotometer was applied to determine the density of genomic DNA.

2.3. SNP genotyping and statistical analysis

We selected Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) from the public SNP database, dbSNP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), as well as the published findings (Table 1). We chose the markers (rs947267, rs3918342) for DAOA gene and (rs165599, rs4680) for COMT gene, because these genes are associated with SCZ and BD. Many studies have recommended that gene polymorphisms are associated with gene expression. The rs4680 is located in exonic region. Exonic SNPs directly impact the characteristics of proteins, while SNPs within untranslated region and introns affect the expression and splicing of mRNA.

Table 1.

Description of genotyped markers

| Genes | SNPs | Chr Position (bp) | Alleles |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAOA (13q34) | rs947267 | 105487313 | A/C |

| rs3918342 | 105533400 | C/T | |

| COMT (22q11) | rs165599 | 19969258 | A/G |

| rs4680 | 19963748 | A/G |

The rs3918342 is located upstream of 5′UTR and the rs165599 is located on 3′UTR. The sequences of the UTRs (untranslated regions) of mRNAs play significant roles in post-transcriptional management. However, it is unclear whether change in UTR length can significantly affect the regulation of gene expression (Lin & Li, 2012). The rs947267 is located in the intronic region. Intronic region mutations induce abnormal splicing (e.g. cryptic splice sites or exon skipping) that is obviously different from normal alternative splicing (Cooper, 2010).

The DNA samples were used to genotyping by PCRRFLP methods. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a technique used in molecular biology to amplify a single copy or a few copies of a segment of DNA for producing thousands to millions copies of a special DNA sequence. As demonstrated in Table 2, the samples were amplified by 2 primer pairs. Primers were designed using the Primer3 software or NCBI Primer-Blast (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast), with the parameters to create a product set.

Table 2.

Primer sequences of the rs947267, rs3918342, rs165599 and rs4680 SNPs

| Genes | SNPs | Alleles | Primers |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAOA | rs947267 | A/C | Forward: 5′-GGGAAAAGGTATCAGGGAGAG-3′ Reverse: 5′-TTGCACACGAACCAAATCAG-3′ |

| rs3918342 | C/T | Forward: 5′-GGAAACCAGAAGGTGAAA-3′ Reverse: 5′-GAATCAGAAAGGAAAAGTGT-3′ |

|

| COMT | rs165599 | A/G | Forward: 5′-CACAGTGGTGCAGAGGTCAG-3′ Reverse: 5′-CTGGCTGACTCCTCTTCGTTT-3′ |

| rs4680 | A/G | Forward: 5′-TCATCACCATCGAGATCAACC-3′ Reverse: 5′-CCCTTTTTCCAGGTCTGACA-3′ |

In Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) analysis, the DNA sample is broken into pieces (and digested) by restriction enzymes and the resulting restriction fragments are separated according to their lengths by gel electrophoresis. RFLP analysis can be used as a form of genetic testing to observe whether an individual carries a mutant gene for a disease that runs in his or her family.

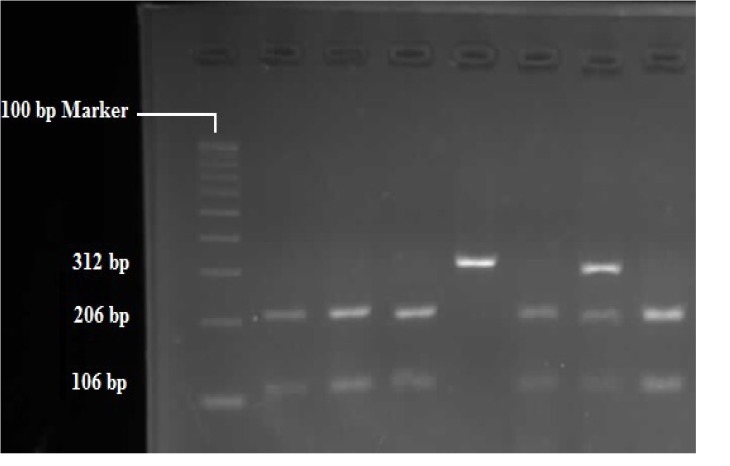

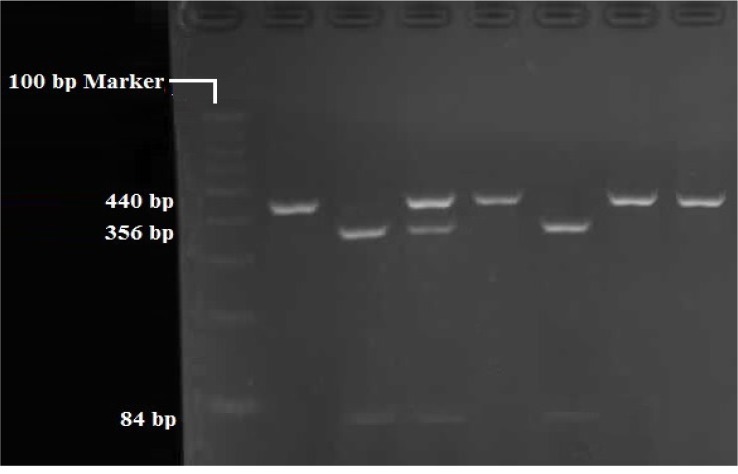

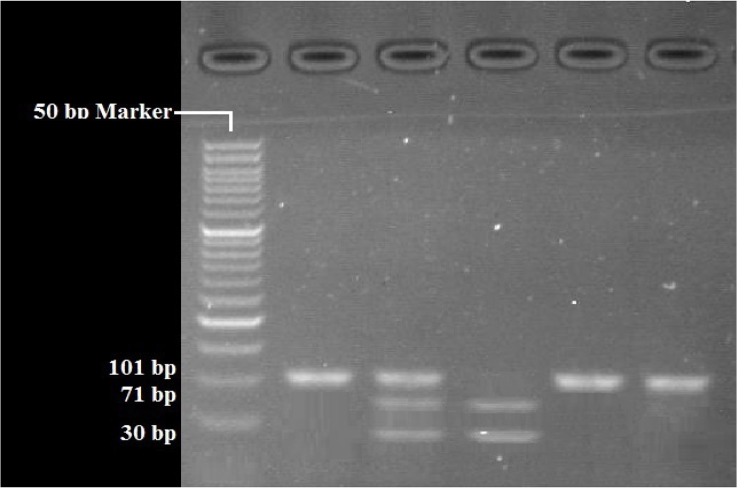

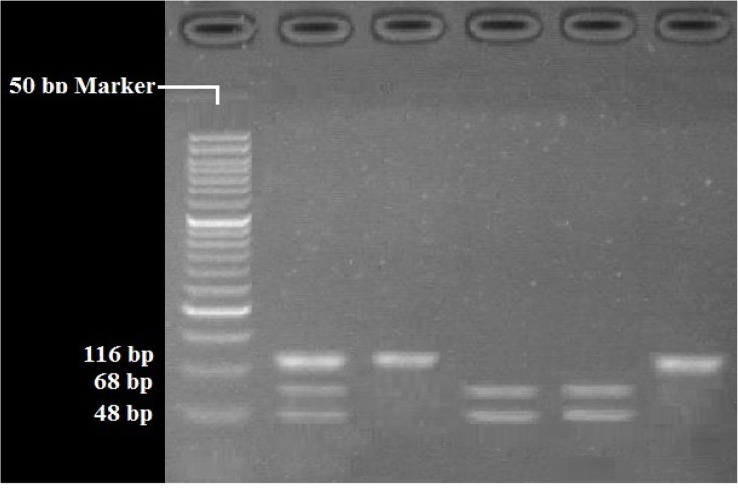

RFLP analysis was performed to determine genotypes of 4 polymorphisms; rs947267 by HaeIII restriction enzyme (Figure 1), rs3918342 by BsaAI restriction enzyme (Figure 2), rs165599 by MspI restriction enzyme (Figure 3), and rs4680 by Hin1II restriction enzyme (Figure 4). In addition, the data were confirmed by sequencing assay. DNA sequencing is the process of determining the http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/ precise order of nucleotides within a DNA molecule. Information were studied by logistic regression and Mantel-Haenszel Chi-square tests. “Hardy Weinberg equilibrium” was estimated using Chi-square test.

Figure 1.

RFLP of rs947267 by HaeIII restriction enzyme: AA (312 bp), CC (206 bp/106 bp), AC (312 bp/206 bp/106 bp)

Figure 2.

RFLP of rs3918342 by BsaAI restriction enzyme: TT (440 bp), CC (356 bp/84 bp), TC (440bp/356bp/84 bp)

Figure 3.

RFLP of rs165599 by MspI restriction enzyme: AA (101 bp), GG (71 bp/30 bp), AG (101bp/71bp/30 bp)

Figure 4.

RFLP of rs4680 by Hin1II restriction enzyme: GG (116 bp), AA (68 bp/48 bp), AG (116bp/686bp/48 bp)

3. Results

The present study aimed to extensively evaluate the contribution of DAOA and COMT genes in susceptibility to SCZ and BID. Genotypic distribution of the SNPs in the case and control groups are listed in Table 3. Moreover, the allele frequency of these SNPs in the case and control groups are listed in Table 4. The obtained data were found in Hardy Weinberg equilibrium. The allele frequency of SNPs was studied by logistic regression and Mantel-Haenszel Chi-square tests. The significance level was set at P<0.05. As per Table 4, the results of P values revealed a statistically significant association between SNPs rs3918342 (P=0.001), rs165599 (P<0.001) and rs4680 (P<0.001), with SCZ. In addition, there was a significant association between SNPs rs3918342 (P<0.001), rs165599 (P<0.001) and rs4680 (P=0.02) with BID.

Table 3.

Genotypic distribution of the SNPs in the case and control groups

| SNPs | Genotypic Distribution | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | Bipolar I Disorder | Controls | ||

| rs947267 | AA | 39 | 41 | 30.7 |

| CC | 12 | 2 | 22.85 | |

| AC | 49 | 57 | 46.45 | |

| rs3918342 | TT | 46 | 23 | 52.755 |

| CC | 17 | 22 | 4.725 | |

| TC | 37 | 55 | 42.52 | |

| rs165599 | AA | 41 | 60 | 16.5 |

| GG | 8 | 3 | 44.9 | |

| AG | 51 | 37 | 38.6 | |

| rs4680 | AA | 94 | 67 | 74 |

| GG | 0 | 10 | 1 | |

| AG | 6 | 23 | 25 | |

Table 4.

Allelic frequency and P values of the SNPs in the case and control groups

| SNPs | Case and Control | Allelic Frequency | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs947267 | Schizophrenia | C | 0.365 | 0.09 |

| A | 0.635 | |||

| BID | C | 0.305 | <0.001 | |

| A | 0.695 | |||

| Controls | C | 0.54 | ||

| A | 0.46 | |||

| rs3918342 | Schizophrenia | C | 0.355 | 0.001 |

| T | 0.645 | |||

| BID | C | 0.495 | <0.001 | |

| T | 0.505 | |||

| Controls | C | 0.26 | ||

| T | 0.74 | |||

| rs165599 | Schizophrenia | A | 0.665 | <0.001 |

| G | 0.335 | |||

| BID | A | 0.785 | <0.001 | |

| G | 0.215 | |||

| Controls | A | 0.358 | ||

| G | 0.642 | |||

| rs4680 | Schizophrenia | A | 0.97 | <0.001 |

| G | 0.03 | |||

| BID | A | 0.785 | 0.02 | |

| G | 0.215 | |||

| Controls | A | 0.865 | ||

| G | 0.135 | |||

Our data demonstrated that rs947267 (P<0.001) was significantly related with BID; however, there was not any association between this SNP (P=0.09) and SCZ. Our data provided further evidence that the DAOA locus or COMT locus may play roles in the pathophysiology of psychotic disorders. Although no direct link has been revealed between genetic polymorphism in these genes and NMDA receptor function, the present results support previous reports implicating the DAOA as susceptible genes for psychotic disorders. Further investigation is warranted to determine the functional variation underlying these results and relate this to the pathophysiology of psychotic disorders.

4. Discussion

The genetics of SCZ and BD seem complicated and without a specific heritability. A multi-locus model has been suggested to clarify the pattern of heritability in this complex disorder. This model indicates that a composition of various genetic agents evolve in these disorders (Risch, 1990). Hence, more than one locus affects the development of SCZ and BD. According to the studies on glutamatergic pathway in Iran, PRODH gene (Rahman zadeh, Mohammadi, karimipour, Heidari keshel, & Omidinia, 2012), DTNBP1 gene (Galehdari, Ajam, & Pooryasin, 2010), GRIN1 gene (Galehdari, 2009), dysbindin gene (Alizadeh, et al., 2012), and NRG1 gene (Shariati, Behmanesh, & Galehdari, 2011) are associated with SCZ.

Dopaminergic pathway research studies in Iran reported that DISC1 gene, is not associated with schizophrenia (Foroughmand, et al., 2010). However, MAOA gene is correlated with BD (Amirabadi, et al., 2015). In this study, the key role of 2 candidate genes; DAOA gene (13q34) and COMT gene (22q11) were significant.

Our findings were compared with other studies. In a meta-analysis, 13 genetic variants revealed genetic overlap between 2 or more affective disorders. DAOA (rs3918342), COMT (Val158Met), DRD4 48-bp, DAT1 40-bp, SLC6A4 5-HTTLPR, APOE e4, ACE Ins/Del, BDNF (Val66Met), HTR1A C1019G, MTHR C677T, MTHR A1298C, TPH1 218A/C and SLC6A4 (VNTR) are demonstrating evidence for pleiotropy in affective disorders (Gatt et al., 2015). Hukic proposed an interaction between DAOA and COMT genes. In addition, SNPs in this genes were associated with cognitive dys-function in bipolar patients (Hukic, 2016).

A study on an Italian population presented some evidence for the association between NMDA-receptor-mediated signaling genes, DAO, PPP3CC, DAOA and DTNBP1 with SCZ (Sacchetti et al., 2013). Deficiency in the glutamatergic system is involved in the pathophysiology of both SCZ and BD (Tsai & Coyle, 2002). The A allele of rs947267 was associated with BID in our study. A follow-up subgroup analysis suggested the genetic polymorphisms of rs947267 in the DAOA gene were not a statistically significant increased risk for SCZ and BD, among the Asian and Caucasian population (Tan et al., 2014).

A meta-analysis composed of 18 correlational articles suggested no correlation between rs947267 and BD, while a remarkable association between rs947267 and BD has been reported in Iran (Shi et al., 2008). Moreover, the association between rs947267 and both SCZ and BD is quite different in the Southwest of Iran, compared to the Asian population. This meta-analysis suggested a correlation between rs947267 and SCZ. Such association has not been observed in Iran. In addition, the T allele of rs3918342 was associated with schizophrenia and BID, in our study. This is the same allele associated with the above-mentioned disorders, in the study of Chumakov et al. (2002).

The meta-analysis on DAOA studies reported no association between rs3918342 and SCZ (Shi et al., 2008). Moreover, the genetic polymorphisms of rs3918342 in the DAOA gene revealed no statistically significant increased risk of SCZ and BD, in a follow-up subgroup analysis on Caucasian and Asian population (Tan et al., 2014). However, the SNP rs3918342 of the DAOA gene showed significant association with SCZ in the Taiwanese population (Chu et al., 2017). Likewise, a remarkable association has been observed between rs3918342 and SCZ and BD in the United Kingdom (Bass et al., 2009).

With regards to the COMT gene, the A allele of rs165599 and rs4680 single nucleotide polymorphisms were associated with SCZ and BID, in our study. A study on Ashkenazi Jewish patients highlighted the significance of association between COMT gene and SCZ (Shifman et al., 2002). Shifman et al. (2004) also reported a positive correlation between rs165599 and BD. Many researchers have studied the rs4680 polymorphism of COMT gene. The association of this variant with SCZ is complex and might be influenced by genetic substructure of human populations (Glatt et al., 2003).

Shifman et al. (2004) observed the association between schizophrenia and rs4680. However, Lajin, Alachkar, Hamzeh, Michati and Alhaj (2011) did not find any association between rs4680 and SCZ. In addition, Shifman et al. (2004) reported no association between rs4680 and BD. However, Mynett-Johnson demonstrated an association between rs4680 and BD (Mynett-Johnson Murphy, Claffey, Shields, & McKeon, 1998).

Obviously, our study fails to prove or reject the complexity of glutamate and dopamine neurotransmission. However, it presents confirmation for the association between such neurotransmissions and SCZ and BD in the patients living in the Southwest Iran. Available treatments for psychotic disorders have had partial success, because most of the work on psychotic disorders was only focused on dopamine for approximately 40 years. While glutamate is the most abundant excitatory neurotransmitter in the nervous system and plays a key role in most aspects of normal brain functions, including cognition, memory and learning. Moreover, revealing the association between SCZ and BD with DAOA and COMT genes recreate the glutamate and dopamine hypothesis.

Genetic linkage analysis has identified numerous overlapping regions in these disorders, including chromosome 6p, 13q, 18q and 22q (Badner & Gershon, 2002). In addition, based on many genetic observations, first or second degree relatives of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder patients are at high risk for these 2 disorders (Arajärvi et al., 2006). SCZ and BD present overlapping symptoms, despite separate and exclusive diagnostic criteria, defined for each. Hence, the etiologic segregation of these disorders into homogenous subtypes is currently under debate.

Our findings suggest a positive correlation between DAOA and COMT genes with SCZ and BD. Our results may provide more validation for the existence of genetic overlap in the common genes of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All procedures performed in studies were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and comparable ethical standards.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Ahvaz Blood Transfusion Organization and all of the DNA sample donors for their precious collaboration.

Footnotes

Funding: See Page 436

Funding

This research was supported by Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Iran.

Authors contributions

The authors contributions is as follows: Leila Ahmadi and Parisima Behbahani equally collaborated in sample collection, experimental studies, design, work, statistical analysis and manuscript writing; Seyed Reza Kazemi Nezhad was the supervisor and edited the manuscript. Nilofar Khajeddin collected samples; Mehdi Pormehdi Borojeni executed the statistical analysis; and All authors read and approved the final version of manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aleman A., Kahn R. S., Selten J. P. (2003). Sex differences in the risk of schizophrenia: Evidence from meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(6), 565–71. [DOI: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.6.565] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh F., Tabatabaiefar M. A., Ghadiri M., Yekaninejad M. S., Jalilian N., Noori-Daloii M. R. (2012). Association of P1635 and P1655 Polymorphisms in Dysbindin (DTNBP1) gene with schizophrenia. Acta Neuropsychiatrica, 24(3), 155–9. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1601-5215.2011.00598.x] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amirabadi M. R. E., Esfahani S. R., Davari-Ashtiani R., Khademi M., Emamalizadeh B., Movafagh A., et al. (2015). Monoamine oxidase a gene polymorphisms and bipolar disorder in Iranian population. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 17(2), 23095. [DOI: 10.5812/ircmj.23095] [PMID ] [PMCID ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arajärvi R., Ukkola J., Haukka J., Suvisaari J., Hintikka J., Partonen T., et al. (2006). Psychosis among” healthy” siblings of schizophrenia patients. BMC Psychiatry, 6, 6. [DOI: 10.1186/1471-244X-6-6] [PMID ] [PMCID ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin J. (2005). Schizophrenia: An update and review. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 14(5), 329–40. [DOI: 10.1007/s10897-005-1622-4] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badner J. A., Gershon E. S. (2002). Meta-analysis of whole-genome linkage scans of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Molecular Psychiatry, 7(4), 405–11. [DOI: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001012] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass N. J., Datta S. R., McQuillin A., Puri V., Choudhury K., Thirumalai S., et al. (2009). Evidence for the association of the DAOA (G72) gene with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder but not for the association of the DAO gene with schizophrenia. Behavioral and Brain Functions, 5(1), 28. [DOI: 10.1186/1744-9081-5-28] [PMID ] [PMCID ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boks M. P., Rietkerk T., van de Beek M.H., Sommer I. E., de Koning T. J., Kahn R. S. (2007). Reviewing the role of the genes G72 and DAAO in glutamate neurotransmission in schizophrenia. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 17(9), 567–72. [DOI: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.12.003] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C. S., Chow P. C. K., Cohen Woods S., Gaysina D., Tang K. Y., McGuffin P. (2017). The DAOA gene is associated with schizophrenia in the Taiwanese population. Psychiatry Research, 252, 201–7. [DOI: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.03.013] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumakov I., Blumenfeld M., Guerassimenko O., Cavarec L., Palicio M., Abderrahim H., et al. (2002). Genetic and physiological data implicating the new human gene G72 and the gene for D-amino acid oxidase in schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(21), 13675–80. [DOI: 10.1073/pnas.182412499] [PMID ] [PMCID ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper N. D. (2010). Functional intronic polymorphisms: Buried treasure awaiting discovery within our genes. Human Genomics, 4(5), 284–8. [DOI: 10.1186/1479-7364-4-5-284] [PMID ] [PMCID ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashti S., Aboutaleb N., Shahbazi A. (2013). The effect of leptin on prepulse inhibition in a developmental modelof schizophrenia. Neuroscience Letters, 555, 57–61. [DOI: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.09.027] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani R., Shahbazi A. (2016). A hypothetical animal model for psychosis based on the silencing of GABAergic system. Journal of Advanced Medical Sciences and Applied Technologies, 2(4), 321–2. [Google Scholar]

- Foroughmand A. M., Haidari M., Galehdari H., Pooryasin A., Kazeminejad S. R., Hosseini S., et al. (2010). Association study between schizophrenia and the DISC1 gene polymorphism. The Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 24(1), 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Galehdari H. (2009). Association between the G1001C polymorphism in the GRIN1 gene promoter and schizophrenia in the Iranian population. Molecular Neuroscience, 38(2), 178–81. [DOI: 10.1007/s12031-008-9148-5] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galehdari H., Ajam T., Pooryasin A. (2010). Combined effect of polymorphic sites in the DTNBP1 and GRIN1 genes on schizophrenia. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 24(1), 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Glatt S., Faraone S., Tsuang MT. (2003). Association between a functional catechol O-methyltransferase gene polymorphism and schizophrenia: Meta-analysis of case-control and family-based studies. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(3), 469–476. [DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.469] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatt J. M., Burton K. L., Williams L. M., Schofield P. R. (2015). Specific and common genes implicated across major mental disorders: A review of meta-analysis studies. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 60, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff D. C., Coyle J. T. (2001). The emerging role of glutamate in the pathophysiology and treatment of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(9), 1367–77. [DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1367] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison P. J., Weinberger D. R. (2005). Schizophrenia genes, gene expression, and neuropathology: On the matter of their convergence. Molecular Psychiatry, 10(1), 40–68. [DOI: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001686] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman J. N., Lolich M., Ketter T. A., Vázquez G. H. (2015). Clinical characteristics of bipolar disorder: A comparative study between Argentina and the United States. International Journal of Bipolar Disorders, 3, 8. [DOI: 10.1186/s40345-015-0027-z] [PMID ] [PMCID ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes O., McCutcheon R., Stone J. (2015). Glutamate and dopamine in schizophrenia: An update for the 21st century. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 29(2), 97–115. [DOI: 10.1177/0269881114563634] [PMID ] [PMCID ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hukic D. S. (2016). Genetic association studies of symptoms, comorbidity and outcome in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Solna, Stockholm: Karolinska Institutet; [PMCID ] [Google Scholar]

- Jagannath V., Gerstenberg M., Correll CU., Walitza S., Grünblatt E. (2018). A systematic meta-analysis of the association of Neuregulin 1 (NRG1), D-amino acid Oxidase (DAO), and DAO Activator (DAOA)/G72 polymorphisms with schizophrenia. Journal of Neural Transmission, 125(1), 89–102. [DOI: 10.1007/s00702-017-1782-z] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagannath V., Theodoridou A., Gerstenberg M., Franscini M., Heekeren K., Correll C. U., et al. (2017). Prediction analysis for transition to schizophrenia in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis: The relationship of DAO, DAOA, and NRG1 variants with negative symptoms and cognitive deficits. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, 292. [DOI: 10.3389/fppsyt.2017.00292] [PMID ] [PMCID ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karayiorgou M., Morris M. A., Morrow B., Shprintzen R. J., Goldberg R., Borrow J., et al. (1995). Schizophrenia susceptibility associated with interstitial deletions of chromosome 22q11. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 92(17), 7612–6. [PMID ] [PMCID ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lajin B., Alachkar A., Hamzeh A. R., Michati R., Alhaj H. (2011). No association between Val158Met of the COMT gene and susceptibility to schizophrenia in the Syrian population. North American Journal of Medicine Science, 3(4), 176–8. [DOI: 10.4297/najms.2011.3176] [PMID ] [PMCID ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leahy R. L. (2007). Bipolar disorder: Causes, contexts, and treatments. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63(5), 417–24. [DOI: 10.1002/jclp.20360] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C. M., Levinson D. F., Wise L. H., DeLisi L. E., Straub R. E., Hovatta I., et al. (2003). Genome scan meta-analysis of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, part II: Schizophrenia. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 73(1), 34–48. [DOI: 10.1086/376549] [PMID ] [PMCID ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z., Li W. H. (2012). Evolution of 5′ untranslated region length and gene expression reprogramming in yeasts. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 29(1), 81–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. L., Fann C. S. J., Liu C. M., Chang C. C., Wu J. Y., Hung S. I., et al. (2006). No association of G72 and D-amino acid oxidase genes with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 87(1–3), 15–20. [DOI: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.020] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo A., Pérez Echeverría M. J., Artal J. (1986). Validity of the scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) in a Spanish population. Psychological Medicine, 16(1), 135–40. [DOI: 10.1017/S0033291700002579] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotta T., Vidgren J., Tilgmann C., Ulmanen I., Melen K., Julkunen I., et al. (1995). Kinetics of human soluble and membrane-bound catechol O-methyltransferase: A revised mechanism and description of the thermolabile variant of the enzyme. Biochemistry, 34(13), 4202–10. [DOI: 10.1021/bi00013a008] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maderia C., Freitas M. E., Vargas-Lopes C., Wolosker H., Panizzutti R. (2008). Increased brain D-Amino Acid Oxidase (DAAO) activity in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 101(1–3), 76–83. [DOI: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.02.002] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meador Woodruff J., Healy D. (2000). Glutamate receptor expression in schizophrenic brain. Brain Research Reviews, 31(2–3), 288–94. [DOI: 10.1016/S0165-0173(99)00044-2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mynett Johnson L. A., Murphy V. E., Claffey E., Shields D. C., McKeon P. (1998). Preliminary evidence of an association between bipolar disorder in females and the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene. Psychiatric Genetics, 8(4), 221–5. [DOI: 10.1097/00041444-199808040-00004] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasirizade F., Mostofi M., Shahbazi A. (2016). Sensorimotor gating deficit in a developmental model of schizophrenia in male Wistar rats. Journal of Medical Physiology, 2(1), 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman zadeh S., Mohammadi H. S, karimipour M., Heidari keshel S., Omidinia E. (2012). Investigation of genetic association between PRODH gene and schizophrenia in Iranian population. Journal of Paramedic Practice, 3(1), 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmanzadeh R., Shahbazi A., Ardakani M. R. K., Mehrabi S., Rahmanzade R., Joghataei M. T. (2017). Lack of the effect of bumetanide, a selective NKCC1 inhibitor, in patients with schizophrenia: A double-blind randomized trial. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 71(1), 72–3. [DOI: 10.1111/pcn.12475] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees E., O’Donovan M. C., Owen M. J. (2015). Genetics of schizophrenia. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 2, 8–14. [DOI: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2014.07.001] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Risch N. (1990). Linkage strategies for genetically complex traits. I. multilocus models. American-Journal of Human Genetics, 46(2), 222–8. [PMID ] [PMCID ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. A., Margolis R. L., Reading S. A., Pletnikov M., Coyle J. T. (2006). Neurobiology of schizophrenia. Neuron, 52(1), 139–53. [DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.015] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacchetti E., Scassellati C., Minelli A., Valsecchi P., Bonvicini C., Pasqualetti P., et al. (2013). Schizophrenia susceptibility and NMDA-receptor mediated signalling: An association study involving 32 tagSNPs of DAO, DAOA, PPP3CC, and DTNBP1 genes. BMC Medical Genetics, 14, 33. [DOI: 10.1186/1471-2350-14-33] [PMID ] [PMCID ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shariati SAM., Behmanesh M., Galehdari H. (2011). A study of the association between SNP8NRG241930 in the 5’ End of Neuroglin 1 gene with schizophrenia in a group of Iranian patients. Cell Journal, 13(2), 91–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Badner J. A., Gershon E. S., Liu C. (2008). Allelic association of G72/G30 with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research, 98(1–3), 89–97. [DOI: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.10.004] [PMID ] [PMCID ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shifman S., Bronstein M., Sternfeld M., Pisanté Shalom A., Lev Lehman E., Weizman A., et al. (2002). A highly significant association between a COMT haplotype and schizophrenia. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 71(6), 1296–1302. [DOI: 10.1086/344514] [PMID ] [PMCID ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shifman S., Bronstein M., Sternfeld M., Pisanté A., Weizman A., Reznik I., et al. (2004). COMT: A common susceptibility gene in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 128(1), 61–4. [DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30032] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J., Lin Y., Su L., Yan Y., Chen Q., Jiang H., et al. (2014). Association between DAOA gene polymorphisms and the risk of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depressive disorder. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 51, 89–98. [DOI: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.01.007] [PMID ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai G., Coyle J. T. (2002). Glutamatergic mechanisms in schizophrenia. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 42(1), 165–79. [DOI: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.082701.160735] [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue W., Kang G., Zhang Y., Qu M., Tang F., Han Y., et al. (2007). Association of DAOA polymorphisms with schizophrenia and clinical symptoms or therapeutic effects. Neuroscience Letters, 416(1), 96–100. [DOI: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.01.056] [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]