Abstract

Despite the remarkable efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) immunotherapy in various types of human cancers, colon cancer, except for the approximately 4% microsatellite-instable (MSI) colon cancer, does not respond to ICI immunotherapy. ICI acts through activating cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) that use the Fas-FasL pathway as one of the two effector mechanisms to suppress tumor. Cancer stem cells are often associated with resistance to therapy including immunotherapy, but the functions of Fas in colon cancer apoptosis and colon cancer stem cells are currently conflicting and highly debated. We report here that decreased Fas expression is coupled with a subset of CD133+CD24lo colon cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Consistent of the lower Fas expression level, this subset of CD133+CD24loFaslo colon cancer cells exhibit decreased sensitivity to FasL-induced apoptosis. Furthermore, FasL selectively enriches CD133+CD24loFaslo colon cancer cells. CD133+CD24loFaslo colon cancer cells exhibit increased lung colonization potential in experimental metastatic mouse models, and decreased sensitivity to tumor-specific CTL adoptive transfer and ICI immunotherapies. Interesting, FasL challenge selectively enriched this subset of colon cancer cells in microsatellite-stable (MSS) but not in the MSI human colon cancer cell lines. Consistent with the down-regulation of Fas expression in CD133+CD24lo cells, lower Fas expression level is significantly correlated with decreased survival in human colon cancer patients.

Keywords: Fas, FasL, T cell immunotherapy, Colon cancer stem cell, MSI colon cancer, MSS colon cancer.

Introduction

CD8+ Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are the primary immune cells that kill target tumor cells in cancer immunosurveillance (1). CTLs use the Fas-FasL and perforin-granzyme pathways as major effector mechanisms of cytotoxicity (2–4) and for the execution of tumor rejection (5, 6). The perforin-granzyme pathway is essential for CTL suppression of established tumors (7). Compelling experimental data have shown that the Fas-FasL apoptosis pathway also plays an essential role in host cancer immunosurveillance (8–10) and in eradication of the established tumors (5, 11–14).

Fas (also termed CD95 or APO-1) is a cell surface receptor of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily and is expressed in hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells including tumor cells. Binding of Fas by its physiological ligand FasL induces Fas receptor trimerization, followed by formation of the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) at the cytoplasmic domain of the Fas receptor, and subsequent cleavage of procaspase-8 at the DISC, leading to the induction of Fas-mediated apoptosis (15–17). Fas receptor also mediates non-apoptotic signaling pathways, and paradoxically Fas has been shown to promote tumor growth and progression (18, 19) and protect colon cancer stem cells (CSC) in certain tumor models (20). FasL is a member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily and is selectively expressed in activated T cells and NK cells (21, 22). FasL can be either membrane-bound on the surface of activated T cells and NK cells (mFasL) (23), or cleaved by metalloproteinases to exist as soluble protein (sFasL) (24). The two different forms of FasL exhibit opposite functions. mFasL induces Fas-mediated apoptosis and is essential for its cytotoxicity in cancer surveillance, whereas excess sFasL appears to promote tumorigenesis through non-apoptotic activities (23). The mechanisms underlying the contrasting functions of the Fas-FasL pathway in apoptosis and colon CSC differentiation is currently unknown.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) cancer immunotherapy has produced durable efficacy in various human hematological malignancies and solid tumors. ICIs suppress the interaction of T cell inhibitory receptors with their cognate ligands on tumor or stromal cells to unleash CTL-mediated cytotoxicity to kill tumor cells (25). However, human colorectal cancer, except for the small subset of microsatellite instable (MSI) tumor, does not respond to ICI immunotherapy (26). The mechanism underlying colorectal cancer non-response to ICI immunotherapy is currently highly debated (27, 28). CSCs, including colon CSCs, are often the major cause of resistance to therapies (29, 30). Considering the essential role of the Fas-FasL in CTL-mediated anti-tumor cytotoxicity (1–5, 8–10, 12–14, 31), determining the functions of Fas in colon CSC-like cells is thus of significance for colorectal cancer immunotherapy (31). Here, we made use of a recombinant FasL trimer protein that mimics mFasL, and mice with only Fas or FasL deficiency to determine the relationship between the Fas-FasL pathway and colon CSC phenotypes. Using these defined and physiologically relevant systems, we determined that Fas is essential for tumor cells apoptosis and that mFasL selectively enriches CD133+CD24loFaslo subset of colon cancer cells that are potentially CSC-like cells. This subset of CD133+CD24loFaslo colon cancer cells exhibit decreased sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis, increased growth potential, and increased resistance to CTL adoptive transfer and ICI immunotherapies.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines:

The murine CT26, human HCT116, HT29, RKO, SW480, and SW620 colon carcinoma cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) in 2013 and stored in aliquots in liquid nitrogen. Cells were used within 30 passages. Murine colon carcinoma MC38, MC38.met, and MC32a cell lines were provided by Dr. Jeffrey Schlom (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD) and were characterized previously (32, 33). Sarcoma MC78 and MC693 cell lines were generated from tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mice, and sarcoma MC68 and MC69 cell lines were generated from tumor-bearing faslpr mice as previously described (34). All cell lines are tested for mycoplasma every 2 months and all cells used in this study were mycoplasma-negative.

Mouse tumor models:

BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Charles River Frederick Facility (Frederick, MD). Faslgld (B6Smn.C3-Faslgld/J) and faslpr (B6.MRL-Faslpr/J) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). To induce spontaneous sarcoma, C57BL/6, faslpr mice were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) with 3-methylcholanthrene (MCA, 100 μg/mouse) in peanut oil. Tumors were dissected from the mice and digested with collagenase solution (1 mg/ml collagenase, 0.1 mg/ml hyaluronidase, and 30 U/ml DNase I) to make single cell suspension. Cells were cultured to establish stable cell lines. The cultured cells were pelleted, fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, and analyzed histologically by a board certified Pathologist (N.M.S.). To establish s.c. tumors, BALB/c (for CT26 cells) and C57BL/6 (for MC32a and MC38 cells) were inoculated in the right unilateral flank with 2.5×105 tumor cells in Hanks’s Buffered Saline Solution. Tumor-bearing mice were sacrificed when the tumor reaches approximately 150 mm3 in size. Tumor tissues were excised and digested with collagenase solution. For the experimental lung metastasis model, sorted subsets of CT26 (1.5 ×105 cells/mouse) and MC38.met (3 ×105 cells/mouse) cells were injected i.v. into BALB/c (CT26 cells), and C57BL/6 and faslgld (MC38.met cells) mice, respectively. Fourteen days later, mice were sacrificed and injected with ink to inflate the tumor-bearing lungs as described (35). All animal studies were performed in compliance with a protocol (2008–0162) approved by Augusta University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

CTL adoptive transfer and anti-PD-1 mAb immunotherapy.

For adoptive transfer immunotherapy, tumor-bearing mice were injected i.v. with the tumor-specific perforin-deficient pk03 CTLs (14). For anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, tumor-bearing mice were treated with IgG (200 μg/mouse) or anti-PD-1 mAb (clone; 29F.1A12, 200 μg/mouse) every 2 days for 5 times.

Cell sorting:

Cell sorting was performed as previously described (36). Briefly, cells were stained with CD133-, CD24-, and Fas-specific mAbs (BioLegend). Stained cells were sorted using a BD FACSAria II SORP or a Beckman Coulter MoFlo XDP cell sorter to isolate cell subsets.

Recombinant FasL protein.

Mega-Fas Ligand (kindly provided by Dr. Peter Buhl Jensen at Oncology Venture A/S, Denmark) is a recombinant fusion protein that consists of three human FasL extracellular domains linked to a protein backbone comprising the dimer-forming collagen domain of human adiponectin. The Mega-Fas Ligand was produced as a glycoprotein in mammalian cells using Good Manufacturing Practice compliant process in Topotarget A/S (Copenhagen, Denmark).

Selection of Fas-resistant cell line:

Tumor cells were cultured in the presence of increasing concentrations of FasL (5, 10, 25, 50, and 200 ng/ml). Cells that survived 200 ng/ml FasL are maintained as FasL-resistant cell lines.

Fas overexpression.

SW480-FasL-R cells were transfected with pLNCX2 or Fas-coding sequence-containing pLNCX2 (provided by Dr. Richard Siegel, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), and selected for stable cell lines SW480-FasLR-Vector SW480-FasLR-Fas.

Tumor cell apoptosis assay:

Cells (1×105 cells/well) were seed in 24-well plates in complete RPMI-1640 media with 10% fetal bovine serum. Recombinant FasL was added into cell culture and incubated for 24 to 72 hours. Both attached and non-attached cells were harvested, washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), suspended in Annexin V binding buffer (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2) and incubated with APC-conjugated Annexin V for 30 min. Propidium iodide (PI) was then added and incubated for another 5 min. Stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Apoptosis is expressed as % Annexin V+ PI- cells, and apoptotic cell death is expressed as %Annexin V+ PI+ cells. Genomic DNA was isolated from cells and analyzed in 1.5% agarose gels.

3H-Thymidine incorporation assay:

Cells were cultured in 96-well plates in the absence or presence of recombinant FasL for 72 hours. 3H- thymidine (1 μCi/well, Amersham Corporation, USA) was then added to the culture and cultured for another 5 hours. Cells were detached with 10 mM EDTA and then were transferred onto the nitrocellulose membrane. 3H incorporation was quantified in a Microplate Scintillation and Luminescence Counter (PerKinElmer 1450 LSC).

Analysis of subsets of cells by flow cytometry:

Cell surface marker staining was performed as previously described (36). Briefly, cells were incubated with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies diluted in FACS buffer (2% BSA in PBS buffer) on ice for 15 min. After washing, cells were acquired using BD LSR II or BD Accri™ C6 Flow Cytometers (BD Biosciences). Monoclonal antibodies used for cell surface staining were: PE-anti-human CD133 (293C3), PECy7-anti-human CD24 (ML5), APC-anti-human Fas (DX2), and PE-mouse IgG2b (27–35) and PE/Cy7-Mouse IgG2a (MOPC-173) isotype controls, which were purchased from Miltenyi Biotec or BioLegend. Data files were analyzed using FlowJo.V10 software. Dead cells were excluded by 7AAD or DAPI staining. All flow cytometric analyses are done on live singlets cells only.

Tumor cell sphere formation assay.

Sphere formation assay was performed as previously described (37). Briefly, cells were cultured in serum-free DMEM medium plus 20 ng/ml EGF and 10 ng/ml basic FGF (Pepro Tech) in ultra-low attachment surface 96-well tissue culture flat bottom plates (Cat# 3474, Costar, Kennebunk, ME).

Transwell and scratch wound healing assay.

Cell Migration was assessed using a 24 well plate with transwell insert (Falcon, Corning, NY). The insert and the plate surface were coated with 0.1% gelatin. Cells were suspended in 200 μl 1% FBS-containing medium and then added to the upper chamber at a density of 6×104 cells/insert and 700 μl 1% FBS-medium was added to the lower chamber. Cells were cultured for 16 h, fixed in 4% PFA and the number of migrant cells to the lower side of the insert was counted under a microscope after staining with crystal violet. For scratch wound healing assay, cells were cultured in 6-well plate to 90–100% confluence. Cell monolayer was scratched with a pipet tip, washed with PBS and supplied with new medium. Scratched areas were measured at 0 and 24 h. Scratch closure rate was calculated with the formula: scratch closure rate (μm/h) = initial scratch width-final scratch width/time.

Statistical analysis:

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA and paired Student’s t-test.

Results

Fas expression level is decreased in CD133+CD24lo subset of colon cancer cells.

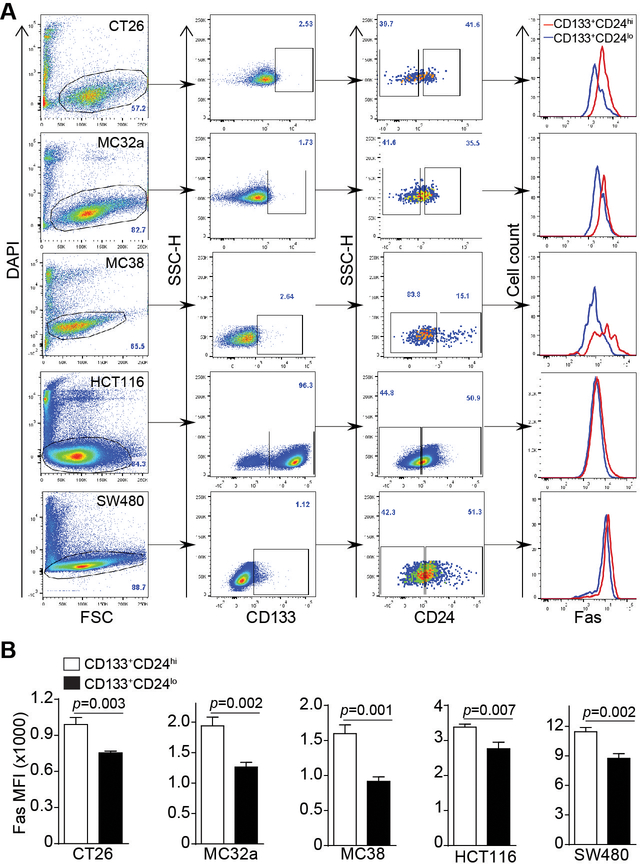

Fas expression level in subsets of colon cancers was compared in murine colon carcinoma CT26, MC32a and MC38 cell lines and human colon carcinoma HCT116 and SW480 cell lines. CD133+ and CD24lo were used to define the phenotype of colon CSC-like cells (20, 37, 38). Fas protein level, as measured by cell surface Fas protein staining mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), is significantly lower in the CD133+CD24lo subset of colon cancer cells as compared to the CD133+CD24hi cells in all three murine colon carcinoma cell lines in vitro (Fig. 1A and B). Similarly, Fas protein level is also significantly lower in the CD133+CD24lo subset of colon cancer cells as compared to the CD133+CD24hi cells in both human colon carcinoma cell lines in vitro (Fig. 1A & B).

Figure 1. Decreased Fas expression is linked to a CD133+CD24lo colon CSC-like cell phenotype in vitro.

A. Murine (CT26, MC32a, and MC38) and human (HCT116 and SW480) colon carcinoma cells were stained with DAPI, and with CD133-, CD24- and Fas-specific mAbs, respectively. The DAPI- live cells were gated and analyzed for CD133+CD24lo and CD133+CD24hi subsets of cells. Fas expression levels (MFI) of CD133+CD24lo and CD133+CD24hi cells were then determined and shown as overlays at the right panel. Shown are gating strategy and representative plots of one of three experiments. B. Fas MFI of CD133+CD24lo and CD133+CD24hi cells as shown in A were quantified and presented. Column: mean; Bar: SD. Statistical differences were determined by student t test.

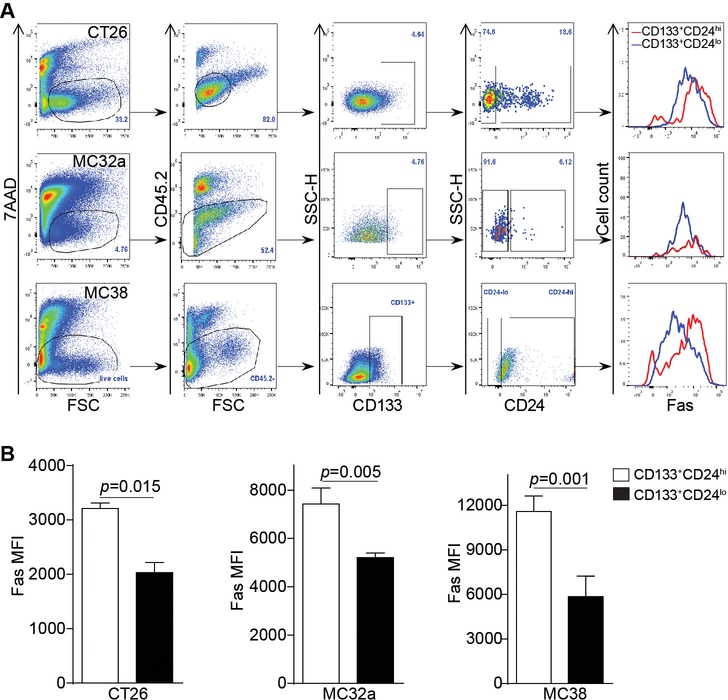

To determine whether the above observations can be extended to colon cancer in vivo, CT26 cells were injected to BALB/c mice, and MC32a and MC38 cells were injected to C57BL/6 mice, respectively. Tumor tissues were dissected from the tumor-bearing mice and analyzed for Fas expression in subsets of colon cancer cells. The level of CD133+CD24lo subset of tumor cell population in vivo is similar to that in vitro in all three cell lines (Fig. 2A). As in the in vitro cultured cells, Fas expression level in CD133+CD24lo subset of cells is significantly lower as compared to the CD133+CD24hi subset of cells in the colon tumor tissues in vivo (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Decreased Fas expression level is correlated with the CD133+CD24lo colon CSC-like cell phenotype in vivo.

A. Murine (CT26, MC32a, and MC38) colon carcinoma cells were injected subcutaneously to BALB/c (CT26) and C57BL/6 (MC32a and MC38) mice, respectively. Tumors were dissected from the tumor-bearing mice and digested with collagenase solution to prepare single cell mixtures. The cell mixtures were stained with 7AAD, and with CD45.2-, CD133-, CD24-, and Fas-specific mAbs, respectively. The 7AAD- live cells and CD45.2- tumor cells were then gated out and analyzed for CD133+CD24lo and CD133+CD24hi subsets of cells. Fas expression levels (MFI) of CD133+CD24lo and CD133+CD24hi cells were then determined and shown as overlays at the right panel. Shown are gating strategy and representative plots of one of three experiments. B. Fas MFI of CD133+CD24lo and CD133+CD24hi cells as shown in A were quantified and presented. Column: mean; Bar: SD. Statistical differences were determined by student t test.

Fas receptor has been shown to mediate both apoptosis and survival signaling pathways (39, 40). We next made use of a physiologically relevant FasL, the MegaFasL, to determine whether Fas mediates apoptosis in colon carcinoma cells. CT26 cells are resistant to FasL (Fig. S1A & B). However, MC32a, MC38, HCT116 and SW480 cells are all sensitive to FasL and exhibited a dose-dependent response in terms of apoptosis (Fig. S1A & B).

To validate the specificity of FasL-induced apoptosis, we next used WT and Fas-deficient tumor cell lines. These cells are high grade sarcoma cells with active mitotic activity (Fig. S2A). As expected, the WT tumor cell lines MC78 and MC693 are sensitive to FasL-induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, Fas-deficient MC68 and MC69 cell lines are resistant to FasL-induced apoptosis (Fig. S2B & C). FasL also suppressed proliferation in MC78 and MC693 cell lines but not in MC68 and MC69 cell lines (Fig. S2D). Taken together, these observations indicate that FasL induce tumor cell apoptosis through the Fas-mediate apoptosis pathway and Fas expression is down-regulated in the CD133+CD24lo colon CSC-like cells.

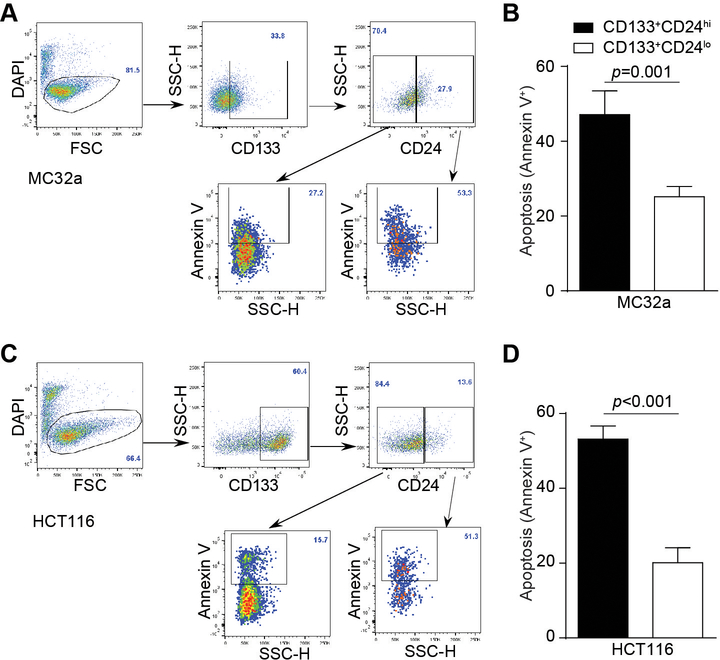

Colon CSC-like cells exhibit reduced sensitivity to FasL-induced apoptosis in vitro.

The decreased Fas expression level in the subset of CD133+CD24lo cells suggests a decreased sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis in the colon CSC-like cells. To test this hypothesis, the murine MC32a and human HCT116 cells were treated with FasL and analyzed for apoptosis. CD133+ cells were gated into CD24hi and CD24lo populations and analyzed apoptotic cells (Fig. 3A and C). Apoptosis is significantly lower in the CD133+CD24lo subset of cells than in the CD133+CD24hi subset of cells in both MC32a and HCT116 cell lines (Fig. 3B & D). These observations indicate that colon CSC-like cells have reduced sensitivity to apoptosis induction by FasL.

Figure 3. Colon CSC-like cells exhibit decreased sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis.

Murine MC32a (A) and human HCT116 (C) colon carcinoma cells were treated with Fas ligand (50 ng/ml) for 24 hours. Shown are representative flow cytometric dot-plots of the gating strategy. Apoptosis (Annexin V+DAPI-) of CD133+CD24lo and CD133+CD24hi cells were determined by flow cytometry. Apoptosis (Annexin V+DAPI-) of the two subsets of cells in MC32a (B) and HCT116 (D) cells were then quantified. Data are representatives of three independent experiments. Column: mean; Bar: SD. Statistical differences were determined by student t test.

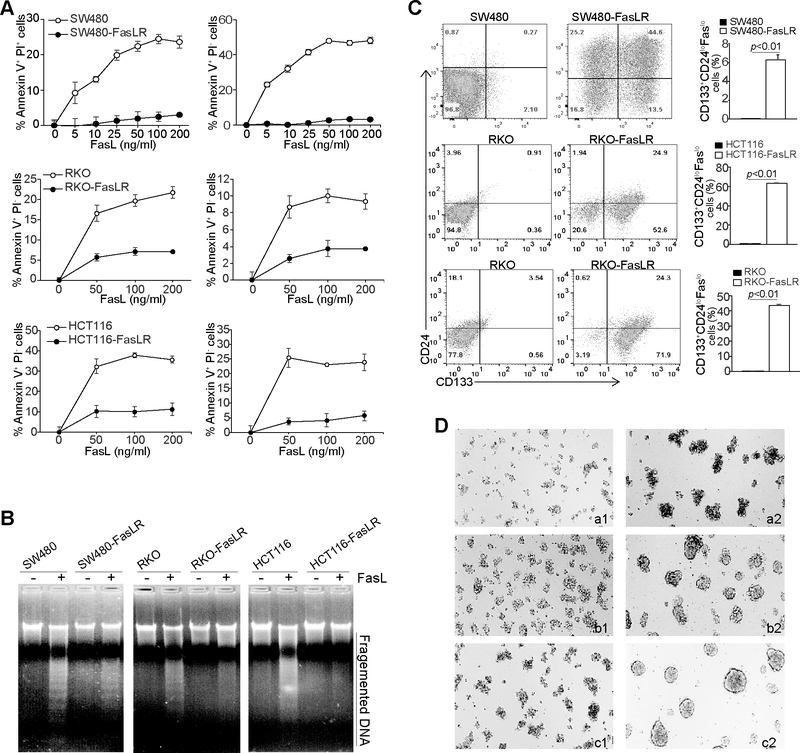

FasL selectively enriches colon CSC-like cells

The above observation suggests that the CD133+CD24loFaslo subset of colon cancer cell might be a consequence of immune selection of FasL+ CTLs during tumorigenesis (41). To test this hypothesis, we used a defined in vitro culture system to culture SW480, RKO and HCT116 cells with increasing concentrations of FasL and generated a FasL-resistant tumor cell sublines. All three FasL-selected cell lines exhibited decreased sensitivity to FasL-induced apoptosis as determined by analyzing early apoptosis (Annexin V+ PI-) and apoptotic cell death (Annexin V+ PI+) (Fig. 4A), as well as genomic DNA fragmentation (Fig. 4B). Flow cytometry analysis revealed that FasL selection significantly enriches CD133+CD24loFaslo cells (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, all three FasL-selected tumor cell lines exhibited acquired sphere formation capability (Fig. 4D). These data thus determine that FasL selectively enriches colon CSC-like cells with a CD133+CD24loFaslo phenotype.

Figure 4. FasL selection enriches colon CSC-like cells.

A. SW480, RKO, HCT116, and the respective FasL-resistant cell lines as indicated were cultured in the presence of FasL at the indicated concentrations for 24h. Cells were stained with PI and annexin V. Early apoptosis (Annexin V+PI-) and apoptotic cell death (Annexin V+PI+) were quantified. B. The three pairs of parent and FasL-resistant cell lines were either untreated or treated with FasL (200 ng/ml) for 24h. Genomic DNA was isolated from the cells and analyzed by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. C. The three pairs of parent and FasL-resistant cell lines were stained with CD133-, CD24-, and Fas specific mAbs and analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown are representative plots of CD133 and CD24 phenotypes (left two panels). CD133+CD24loFaslo cell subsets were then quantified and presented at the right panel. D. The parent and FasL-resistant cell lines were cultured in ultra-low attachment tissue culture plates with serum-free DMEM medium supplemented with EGF (20 ng/ml) and basic FGF (10 ng/ml), respectively, for 10 days. Shown are representative images of cell morphology of three independent experiments. a1 SW480, a2: SW480-FasLR, b1: RKO, b2: RKO-FasLR, c1: HCT116, C2: HCT116-FasLR.

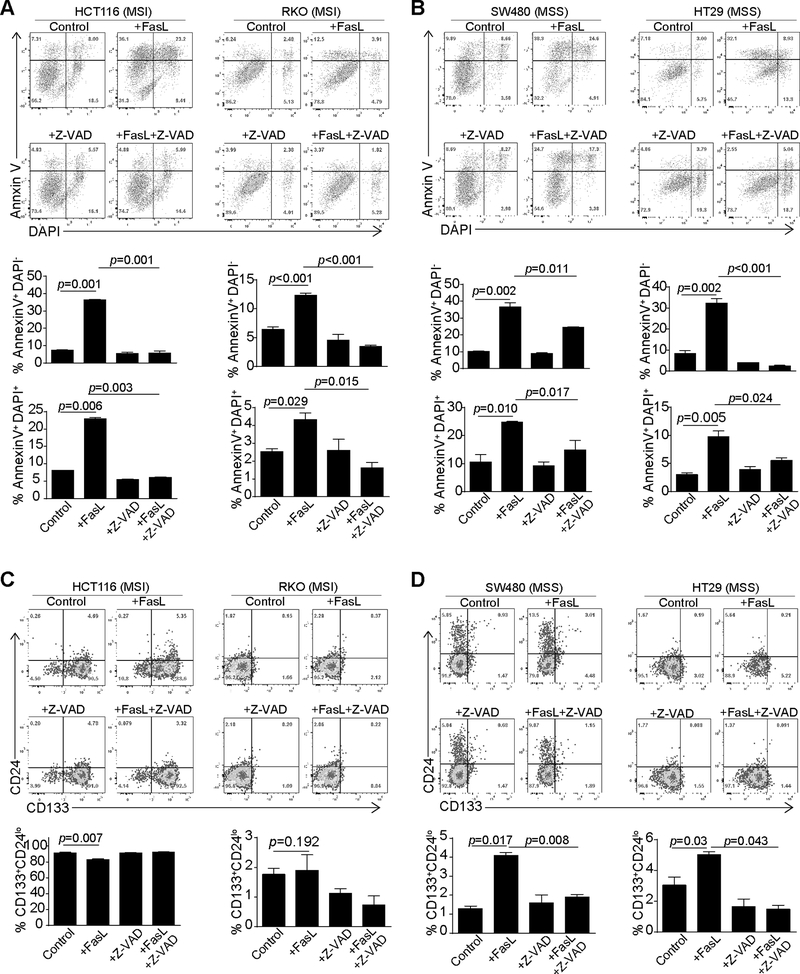

MSS colon carcinoma cells respond to FasL to differentiate to CSC-like cells

MSI but not MSS colon carcinoma cells respond to ICI immunotherapy (26). FasL-mediated cytotoxicity is a major effector mechanism of ICI-activated CTL anti-tumor cytotoxicity. Our above data indicate that decreased Fas expression level and sensitivity to FasL-induced apoptosis is potentially a phenotype of colon CSC-like cells. We therefore reasoned that the CSC-like cell population may contribute to different MSI and MSS response to FasL. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed responses of MSI (HCT116 and RKO) and MSS (SW480 and HT29) human colon carcinoma cell lines (42) to FasL. FasL induced apoptosis in all four cell lines regardless of MSI and MSS phenotypes (Fig. 5A and B). The pan-caspase activation blocker Z-VAD inhibited FasL-induced apoptosis, suggesting a caspase-dependent apoptosis induction by FasL (Fig. 5A & B). Analysis of CD133+CD24lo cell population revealed that FasL treatment did not significantly enrich the CSC-like cell level in the two MSI cell lines. However, FasL treatment significantly increased the CD133+CD24lo subset of cells in the two MSS colon carcinoma cell lines (Fig. 5C & D). Furthermore, inhibition of caspase activation blocked both apoptosis and FasL-induced enrichment of CD133+CD24lo colon CSC-like cells (Fig. 5B and5D). Our data thus suggest that FasL enriches CD133+CD24lo colon CSC-like cells and doing so in a caspase-dependent manner.

Figure 5. FasL treatment increases CSC-like cells in MSS colon cancer cells.

A & B. MSI (A. HCT116 and RKO) and MSS (B. SW480 and HT29) human colon carcinoma cell lines were cultured in the presence of FasL (50 ng/ml), Z-VAD (20 μM) or both FasL and Z-VAD for 24h. Cells were then stained with with PI and annexin V. Top panel shows representative flow cytometry dot plots. Apoptosis (Annexin V+PI-) and apoptotic cell death (Annexin+PI+) were quantified and presented at the bottom panel. Column: mean; Bar: SD. Data are representative result of one of two independent experiments. C & D. The MSI and MSS human colon carcinoma cell lines were treated as in A and B and then stained with CD133- and CD24-specific mAbs and analyzed by flow cytometry. CD133+CD24lo cells were quantified. Top panel shows representative flow cytometric dot plots. CD133+CD24lo cells were quantified and presented at the bottom panel.

IFNγ and TNFα both regulate Fas expression and enhance tumor cell response to Fas-mediated apoptosis. To determine whether IFNγ and TNFα regulates FasL selection and enrichment of colon CSC-like cells, HCT116 and SW480 cells were pre-treated with IFNγ and TNFα, followed by FasL treatment. As observed above, FasL increased the level of CD133+CD24lo cell population in the MSS SW480 but not in the MSI HCT116 cells (Fig. S3A). IFNγ and TNFα treatment did not significantly change FasL-induced enrichment of CD133+CD24lo in both HCT116 and SW480 cells (Fig. S3).

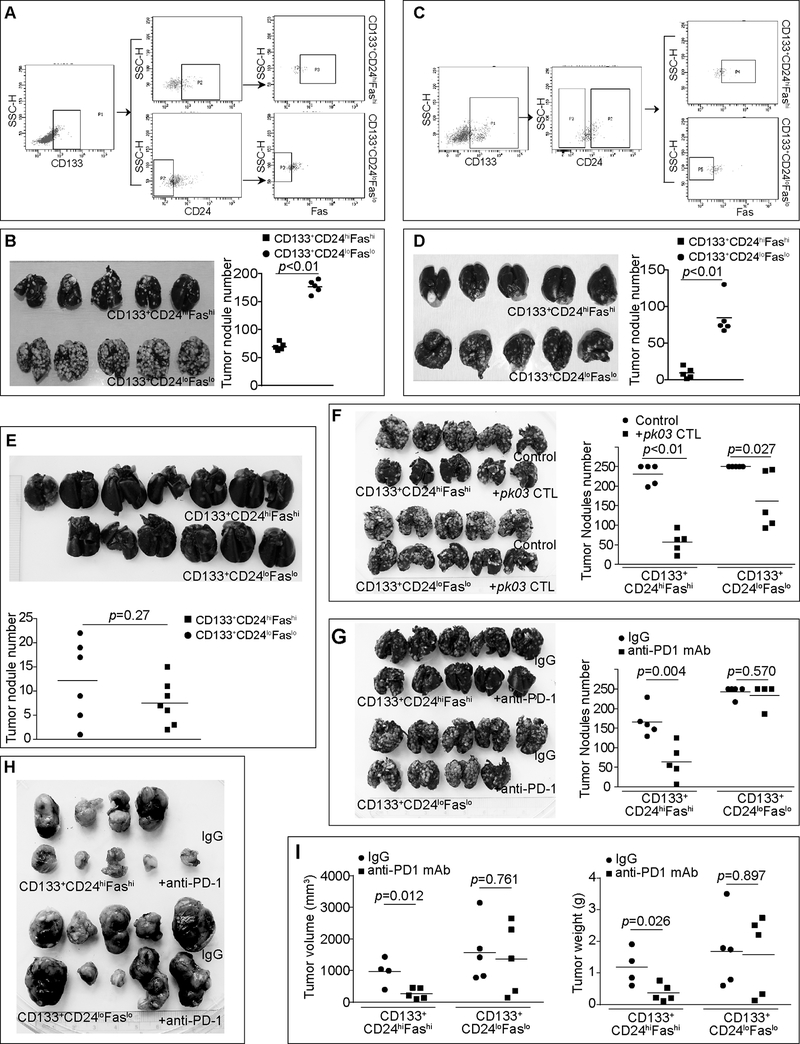

CD133+CD24loFaslo colon cancer cells exhibit increased resistance to T cell immunotherapy.

To determine tumor invasiveness in vivo, we sorted CD133+CD24loFaslo and CD133+CD24hiFashi from both CT26 (Fig. 6A) and MC38.met (Fig. 6C) cells and injected these cells to mice and compared their colonization efficacy in lungs in an experimental metastasis system. CD133+CD24loFaslo cells exhibited significantly higher lung colonization potential in both the CT26 (Fig. 6B) and MC38.met (Fig. 6D) mouse models. This increased invasiveness is validated by in vitro tumor cell migration and scratch wound healing assays. CD133+CD24loFaslo CT26 cells exhibited significantly higher migration and scratch wound healing capability than the CD133+CD24hiFashi CT26 cells (Fig. S4).

Figure 6. Faslo colon CSC-like cells exhibit a higher lung colonization potential and resistance to T cell immunotherapy.

A. CT26 cells were stained with CD133-, CD24- and Fas-specific mAbs and sorted into CD133+CD24loFaslo and CD133+CD24hiFashi cells. Showing is the gating strategy for sorting. B. The sorted CD133+CD24loFaslo and CD133+CD24hiFashi cells were injected i.v. into BALB/c mice (1.5×105 cells/mouse, n=5). Fourteen days later, mice were sacrificed and india ink was perfused into the lung. The ink-inflated lungs were fixed. Shown are tumor-bearing lungs. The tumor nodule number was counted and presented at the right. Statistical significance was determined by student t test. C. MC38.met cells were stained with CD133-, CD24- and Fas-specific mAbs and sorted into CD133+CD24loFaslo and CD133+CD24hiFashi cells. Showing is the gating strategy for sorting. D. The sorted CD133+CD24loFaslo and CD133+CD24hiFashi cells were injected i.v. into C57BL/6 mice (3×105 cells/mouse, n=5). Fourteen days later, mice were sacrificed and india ink was perfused into the lung. The ink-inflated lungs were fixed. Shown are tumor-bearing lungs. The tumor nodule number was counted and presented at the right. E. Sorted CD133+CD24loFaslo (n=6) and CD133+CD24hiFashi (n=7) MC38.met cells were injected into FasL-deficient faslgld mice (3×105 cells/mouse) i.v. Fourteen days later, mice were sacrificed and india ink was perfused into the lung. The ink-inflated lungs were fixed. Shown are tumor-bearing lungs. The tumor nodule number was counted and presented at the bottom. F. CD133+CD24loFaslo and CD133+CD24hiFashi CT26 cells were injected i.v. into BALB/c mice (2×105 cells/mouse, n=5). Four days later, mice with treated with saline control or perforin-deficient pk03 CTLs (3×105 cells/mouse). Mice were sacrificed on day 14 and analyzed as in B. G. CD133+CD24loFaslo and CD133+CD24hiFashi CT26 cells were injected i.v. into BALB/c mice (2×105 cells/mouse, n=5). Four days later, mice were treated with IgG (200 mg/mouse) or anti-PD-1 mAb (200 mg/mouse) every 2 days for 5 times. Lung tumors were analyzed as in B. H. CD133+CD24loFaslo and CD133+CD24hiFashi CT26 cells were injected s.c. into BALB/c mice (2×105 cells/mouse, n=5). Ten days later, CD133+CD24loFaslo and CD133+CD24hiFashi CT26 tumor-bearing mice were randomly grouped into two groups, respectively, and treated with IgG or anti-PD-1 mAb as in G every 2 days for 5 times. Mice were sacrificed two days after the last treatment. Shown are tumor images. I. The sizes and weights of tumors as shown in H were measured and analyzed by student t test.

To determine the contribution of the Faslo phenotype in the colonization potential, CD133+CD24loFaslo and CD133+CD24hiFashi MC38.met cells were injected to FasL-deficient mice. The rationale is that if Fas-FasL interaction mediates tumor cell colonization potential, then these two subsets of tumor cells should colonize in lungs of FasL-deficient mice at similar rate. Indeed, no significant difference was observed in the tumor nodule numbers between the two groups of mice that received CD133+CD24loFaslo and CD133+CD24hiFashi cells (Fig. 6E). To determine the response of CD133+CD24loFaslo and CD133+CD24hiFashi tumor cells to immunotherapy, we treated tumor-bearing mice with a tumor-specific and perforin-deficient CTL line. The rationale is that the CD133+CD24loFaslo tumor cells are relatively more resistant to FasL, this subset of cells should be less susceptible to perforin-deficient CTLs. Indeed, the CD133+CD24loFaslo CT26 tumor exhibited significantly less response to the perforin-deficient CTLs as compared to CD133+CD24hiFashi CT26 tumor (Fig. 6F). We then sought to determine the response of these two subsets of cells to ICI immunotherapy. It is clear that CD133+CD24loFaslo tumor is significantly less responsive to anti-PD-1 mAb immunotherapy than the CD133+CD24hiFashi CT26 tumor in both the experimental lung metastasis model and the s.c. tumor model (Fig. 6G-I). These observations indicate that a CD133+CD24loFaslo subset of colon cancer cells is at least partially responsible for colon cancer resistance to ICI immunotherapy.

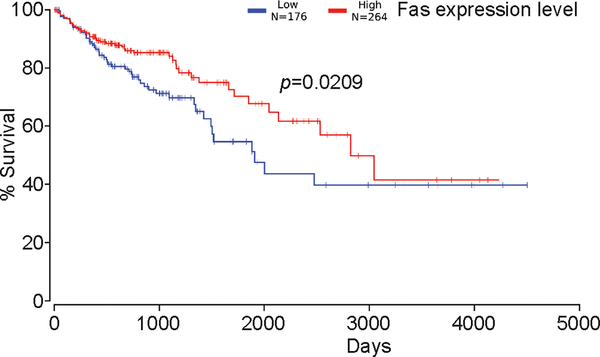

Lower Fas expression level is correlated with decreased survival in human colorectal cancer patients

The Fas-FasL pathway plays an essential role in host cancer immunosurveillance. Our above observations suggest that decreased Fas expression may be a key phenotype of colon CSC-like cells and may contribute to patient disease outcome. To test this hypothesis, we examined Fas expression levels in human colorectal carcinoma. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for Fas mRNA level revealed that Fas expression level is positively correlated with increased survival in human colorectal cancer patients (Fig. 7). Therefore, it is clear that colon CSCs may use down-regulation of Fas expression to increase resistance to FasL-induced apoptosis to evade host cancer immunosurveillance in human colon cancer patients.

Figure 7. Decreased Fas expression is correlated with decreased survival in human colorectal cancer patients.

Fas mRNA levels were extracted from the TCGA database and plotted against survival in human colorectal patients.

Discussion

The major and best known function of Fas is apoptotic cell death (39). However, Fas also mediates non-apoptotic signaling pathways and has been shown to promote tumor growth in certain tumor models (18, 19, 43). Under physiological conditions, Fas is expressed virtually in all types of cells, whereas FasL is selectively expressed on the surface of activated T cells and NK cells (4, 21). Under pathological conditions such as cancer, FasL is also abundantly expressed in tumor cells in the cytoplasm (20) and are often secreted as sFasL by tumor cells (21, 44), but not on tumor cell surface as membrane-bound form. It has been well demonstrated that membrane-bound FasL induces apoptosis whereas excess sFasL induce non-apoptotic activities and promote cellular proliferation (23). Therefore, it is not surprising that Fas may promote tumor growth and progression under certain pathological conditions (18, 19). Using a recombinant FasL protein that structurally mimics the mFasL trimer, we observed that two of the three murine and three of the three human colon cancer cell lines are sensitive to FasL-induced apoptosis. Fas is weakly expressed on CT26 cells. CT26 cells, as expected, do not respond to FasL to undergo apoptosis. This phenomenon is validated in the Faslpr tumor cell lines. Although the Faslpr mice lack an increase in spontaneous tumor development (45), Faslpr mice are more susceptible to carcinogen induction of spontaneous tumorigenesis (34). We demonstrated here that loss of Fas function in the Faslpr tumor cell line abolishes tumor cell sensitivity to FasL-induced apoptosis. In contrast to promotion of cellular proliferation by sFasL, we also observed that FasL suppresses tumor cell proliferation through a Fas-dependent mechanism. These data thereby validate the role of Fas in apoptotic cell death of tumor cells.

In this study, we also observed that a decreased Fas expression level is linked to the CD133+CD24lo colon CSC-like cell phenotype in mouse and human colon carcinoma cell lines in vitro and in mouse colon carcinoma in vivo. We observed that CD133+CD24lo colon CSC-like cells are less sensitive to FasL-induced apoptosis as compared to the CD133+CD24hi cells. This observation is consistent with the report that CSC have decreased sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis (20). However, it is unlikely that Fas plays a direct role in colon CSC-like maintenance since overexpression of Fas in FasL-resistant tumor cells did not alter colon tumor cell sphere formation (Fig. S5). It has been shown that Fas and FasL, especially tumor cell produced FasL, promote and protect CSCs (20, 46). Interestingly, we observed that although FasL induces apoptosis in both MSI and MSS colon carcinoma cells, FasL increases colon CSC-like cells only in MSS human colon carcinoma cell lines but not in the MSI human colon carcinoma cell lines. Furthermore, we observed that FasL also selectively enrich the Fas resistant cell subsets that have a colon CSC-like phenotype. Therefore, it appears that FasL may promote colon CSC both through inducing colon CSC-like cell differentiation and through eliminating the Fas-sensitive cells to selectively enrich the Fas-resistant cells with a colon CSC-like phenotype. The expression of FasL, the physiological ligand for Fas, is primarily restricted to activated T cells (2, 4, 8, 23). We observed that the CD133+CD24loFaslo and CD133+CD24loFashi colon cancer cells exhibit significant difference in lung colonization efficiency in the immune competent mice (Fig. 6D) but not in the FasL-deficient mice (Fig. 6E)., which suggest that host immune cells modulate these two subsets of colon CSC-like cells. One limitation of this study is thus that the stemness of the CD133+CD24loFaslo colon cancer cells and the function of Fas in stemness cannot be determined by the conventional limited dilution assay in immune-deficient mice. Therefore, whether Faslo phenotype is a colon cancer stem cell marker remains to be determined. Nevertheless, the CD133+CD24loFaslo subset of cells may represent colon CSC-like cells.

MSI human colorectal cancer but not MSS human colorectal cancer responds to ICI immunotherapy (26). It is known that CSCs are often the source of resistance to therapy including chemotherapy and radiotherapy (29, 47). We determined here that the CD133+CD24loFaslo colon CSC-like cells are more resistant to CTL adoptive transfer immunotherapy and to ICI immunotherapy. The link between colon CSCs and MSS colon cancer is not clear. FasL is one of the two lytic mechanisms that CTLs use to induce tumor cell apoptosis to suppress tumor growth and progression (1–5, 8–10, 12–14, 31). Our observation that FasL treatment induces colon CSC-like cells in human colon cancer cell lines suggests that MSS human colon carcinoma cells might use an increase in CSCs to respond to FasL to acquire a Fas-resistant phenotype. Therefore, in addition to its potent tumor suppression activity, tumor-reactive CTL FasL may also induce colon CSC differentiation and selectively enrich Faslo colon CSCs through eliminating Fas-sensitive non-stem cells, resulting in immunoselection (41) and accumulation of Faslo colon CSCs which underlies MSS colon cancer resistance to ICI immunotherapy. Considering the significance of MSS/MSI phenotype in ICI immunotherapy and colon cancer stem cell in resistance to therapies, further studies are warranted to further determine the role of Fas in colon cancer stem cell pathogenesis and resistance to ICI immunotherapy in human colorectal cancer patients (31).

Supplementary Material

Implications.

Our data determine that CD133+CD24loFaslo colon cancer cells are capable to evade Fas-FasL cytotoxicity of tumor-reactive CTLs and targeting this subset of colon cancer cells is potentially an effective approach to suppress colon cancer immune evasion.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Jeanene Pihkala at the Medical College of Georgia Flow Cytometry Core Facility and Dr. Ningchun Xu at Georgia Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Core Facility for assistance in cell sorting.

Grant support: NIH/NCI CA182518 and CA133085 (K.L.)

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists

References

- 1.Hanson HL, Donermeyer DL, Ikeda H, White JM, Shankaran V, Old LJ, et al. Eradication of established tumors by CD8+ T cell adoptive immunotherapy. Immunity. 2000;13:265–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kagi D, Vignaux F, Ledermann B, Burki K, Depraetere V, Nagata S, et al. Fas and perforin pathways as major mechanisms of T cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Science. 1994;265:528–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maeda Y, Levy RB, Reddy P, Liu C, Clouthier SG, Teshima T, et al. Both perforin and Fas ligand are required for the regulation of alloreactive CD8+ T cells during acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2005;105:2023–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golstein P, Griffiths GM. An early history of T cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seki N, Brooks AD, Carter CR, Back TC, Parsoneault EM, Smyth MJ, et al. Tumor-specific CTL kill murine renal cancer cells using both perforin and Fas ligand-mediated lysis in vitro, but cause tumor regression in vivo in the absence of perforin. J Immunol. 2002;168:3484–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morales-Kastresana A, Catalan E, Hervas-Stubbs S, Palazon A, Azpilikueta A, Bolanos E, et al. Essential complicity of perforin-granzyme and FAS-L mechanisms to achieve tumor rejection following treatment with anti-CD137 mAb. J Immunother Cancer. 2013;1:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van den Broek ME, Kagi D, Ossendorp F, Toes R, Vamvakas S, Lutz WK, et al. Decreased tumor surveillance in perforin-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1781–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Afshar-Sterle S, Zotos D, Bernard NJ, Scherger AK, Rodling L, Alsop AE, et al. Fas ligand-mediated immune surveillance by T cells is essential for the control of spontaneous B cell lymphomas. Nat Med. 2014;20:283–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strater J, Hinz U, Hasel C, Bhanot U, Mechtersheimer G, Lehnert T, et al. Impaired CD95 expression predisposes for recurrence in curatively resected colon carcinoma: clinical evidence for immunoselection and CD95L mediated control of minimal residual disease. Gut. 2005;54:661–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peyvandi S, Buart S, Samah B, Vetizou M, Zhang Y, Durrieu L, et al. Fas Ligand Deficiency Impairs Tumor Immunity by Promoting an Accumulation of Monocytic Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Cancer Res. 2015;75:4292–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Owen-Schaub LB, van Golen KL, Hill LL, Price JE. Fas and Fas ligand interactions suppress melanoma lung metastasis. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1717–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobrzanski MJ, Reome JB, Hollenbaugh JA, Hylind JC, Dutton RW. Effector cell-derived lymphotoxin alpha and Fas ligand, but not perforin, promote Tc1 and Tc2 effector cell-mediated tumor therapy in established pulmonary metastases. Cancer Res. 2004;64:406–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergmann-Leitner ES, Abrams SI. Differential role of Fas/Fas ligand interactions in cytolysis of primary and metastatic colon carcinoma cell lines by human antigen-specific CD8+ CTL. J Immunol. 2000;164:4941–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caldwell SA, Ryan MH, McDuffie E, Abrams SI. The Fas/Fas ligand pathway is important for optimal tumor regression in a mouse model of CTL adoptive immunotherapy of experimental CMS4 lung metastases. J Immunol. 2003;171:2402–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavrik IN, Krammer PH. Regulation of CD95/Fas signaling at the DISC. Cell Death Differ. 2011;19:36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaufmann T, Strasser A, Jost PJ. Fas death receptor signalling: roles of Bid and XIAP. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Modiano JF, Bellgrau D. Fas ligand based immunotherapy: A potent and effective neoadjuvant with checkpoint inhibitor properties, or a systemically toxic promoter of tumor growth? Discov Med. 2016;21:109–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleber S, Sancho-Martinez I, Wiestler B, Beisel A, Gieffers C, Hill O, et al. Yes and PI3K bind CD95 to signal invasion of glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:235–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen L, Park SM, Tumanov AV, Hau A, Sawada K, Feig C, et al. CD95 promotes tumour growth. Nature. 2010;465:492–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ceppi P, Hadji A, Kohlhapp FJ, Pattanayak A, Hau A, Liu X, et al. CD95 and CD95L promote and protect cancer stem cells. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bossi G, Griffiths GM. Degranulation plays an essential part in regulating cell surface expression of Fas ligand in T cells and natural killer cells. Nat Med. 1999;5:90–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dupaul-Chicoine J, Arabzadeh A, Dagenais M, Douglas T, Champagne C, Morizot A, et al. The Nlrp3 Inflammasome Suppresses Colorectal Cancer Metastatic Growth in the Liver by Promoting Natural Killer Cell Tumoricidal Activity. Immunity. 2015;43:751–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LA O, Tai L, Lee L, Kruse EA, Grabow S, Fairlie WD, et al. Membrane-bound Fas ligand only is essential for Fas-induced apoptosis. Nature. 2009;461:659–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider P, Bodmer JL, Holler N, Mattmann C, Scuderi P, Terskikh A, et al. Characterization of Fas (Apo-1, CD95)-Fas ligand interaction. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18827–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boussiotis VA. Molecular and Biochemical Aspects of the PD-1 Checkpoint Pathway. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1767–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, et al. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Llosa NJ, Cruise M, Tam A, Wicks EC, Hechenbleikner EM, Taube JM, et al. The vigorous immune microenvironment of microsatellite instable colon cancer is balanced by multiple counter-inhibitory checkpoints. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Velez-Delgado A, Mathew E, Li D, Mendez FM, Flannagan K, et al. Myeloid cells are required for PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint activation and the establishment of an immunosuppressive environment in pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2017;66:124–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeuner A, Todaro M, Stassi G, De Maria R. Colorectal cancer stem cells: from the crypt to the clinic. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:692–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paschall A, Liu K. Epigenetic and Immune Regulation of Colorectal Cancer Stem Cells. Current Colorectal Cancer Reports. 2015;11 414–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iovino F, Meraviglia S, Spina M, Orlando V, Saladino V, Dieli F, et al. Immunotherapy targeting colon cancer stem cells. Immunotherapy. 2011;3:97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takai S, Sabzevari H, Farsaci B, Schlom J, Greiner JW. Distinct effects of saracatinib on memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2012;188:4323–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith JJ, Deane NG, Wu F, Merchant NB, Zhang B, Jiang A, et al. Experimentally derived metastasis gene expression profile predicts recurrence and death in patients with colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:958–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu F, Bardhan K, Yang D, Thangaraju M, Ganapathy V, Waller JL, et al. NF-kappaB Directly Regulates Fas Transcription to Modulate Fas-mediated Apoptosis and Tumor Suppression. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:25530–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paschall AV, Liu K. An Orthotopic Mouse Model of Spontaneous Breast Cancer Metastasis. J Vis Exp. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Redd PS, Ibrahim ML, Klement JD, Sharman SK, Paschall AV, Yang D, et al. SETD1B Activates iNOS Expression in Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77:2834–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paschall AV, Yang D, Lu C, Redd PS, Choi JH, Heaton CM, et al. CD133+CD24lo defines a 5-Fluorouracil-resistant colon cancer stem cell-like phenotype. Oncotarget. 2016;7:78698–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, Dick JE. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2007;445:106–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Villa-Morales M, Fernandez-Piqueras J. Targeting the Fas/FasL signaling pathway in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16:85–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Villa-Morales M, Gonzalez-Gugel E, Shahbazi MN, Santos J, Fernandez-Piqueras J. Modulation of the Fas-apoptosis-signalling pathway by functional polymorphisms at Fas, FasL and Fadd and their implication in T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma susceptibility. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:2165–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu K, Caldwell SA, Greeneltch KM, Yang D, Abrams SI. CTL adoptive immunotherapy concurrently mediates tumor regression and tumor escape. J Immunol. 2006;176:3374–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahmed D, Eide PW, Eilertsen IA, Danielsen SA, Eknaes M, Hektoen M, et al. Epigenetic and genetic features of 24 colon cancer cell lines. Oncogenesis. 2013;2:e71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ehrenschwender M, Wajant H. The role of FasL and Fas in health and disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;647:64–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nadal C, Maurel J, Gallego R, Castells A, Longaron R, Marmol M, et al. FAS/FAS ligand ratio: a marker of oxaliplatin-based intrinsic and acquired resistance in advanced colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4770–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wajant H CD95L/FasL and TRAIL in tumour surveillance and cancer therapy. Cancer Treat Res. 2006;130:141–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Drachsler M, Kleber S, Mateos A, Volk K, Mohr N, Chen S, et al. CD95 maintains stem cell-like and non-classical EMT programs in primary human glioblastoma cells. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Venugopal A, Subramaniam D, Balmaceda J, Roy B, Dixon DA, Umar S, et al. RNA binding protein RBM3 increases beta-catenin signaling to increase stem cell characteristics in colorectal cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2016;55:1503–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.