Structured Abstract

Background:

Oil and natural gas (O&G) extraction emits pollutants that are associated with cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of mortality in the United States.

Objective:

We evaluated associations between intensity of O&G activity and cardiovascular disease indicators.

Methods:

Between October 2015 and May 2016, we conducted a cross-sectional study of 97 adults living in Northeastern Colorado. For each participant, we collected 1–3 measurements of augmentation index, systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP), and plasma concentrations of interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). We modelled the intensity of O&G activity by weighting O&G well counts within 16 km of a participant’s home by intensity and distance. We used linear models accounting for repeated measures within person to evaluate associations.

Results:

Adjusted mean augmentation index differed by 6.0% (95% CI: 0.6, 11.4%) and 5.1% (95%CI: −0.1, 10.4%) between high and medium, respectively, and low exposure tertiles. The greatest mean IL-1β, and α-TNF plasma concentrations were observed for participants in the highest exposure tertile.. IL-6 and IL-8 results were consistent with a null result. For participants not taking prescription medications, the adjusted mean SBP differed by 6 and 1 mm Hg (95% CIs: 0.1, 13 mm Hg and −6, 8 mm Hg) between the high and medium, respectively, and low exposure tertiles. DBP results were similar. For participants taking prescription medications, SBP and DBP results were consistent with a null result.

Conclusions:

Despite limitations, our results support associations between O&G activity and augmentation index, SBP, DBP, IL-1β, and TNF-α. Our study was not able to elucidate possible mechanisms or environmental stressors, such as air pollution and noise.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality in the United States (U.S.), accounting for more than 900,000 deaths and 3,000 per 100,000 persons agestandardized disability-adjusted life years (DALYS) in 2016 (Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases 2017; Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases 2018). While behavioral and genetic factors contribute to the burden of CVD, exposure to environmental stressors, such as air pollution, noise, and psychosocial stress, also contribute to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (Brook 2017; Cuffee et al. 2014).

One increasingly common source of these environmental stressors is the extraction of oil and natural gas (O&G) in residential areas (Adgate et al. 2014; Czolowski et al. 2017; McKenzie et al. 2016). In the early 21st century, advances in hydraulic fracturing (fracking), horizontal drilling, and micro-seismic imaging opened up previously inaccessible petroleum reserves that resulted in an extensive dispersion of O&G well sites across populated areas (Haynes et al. 2017). More than 17.4 million people in the U.S. now live within 1.6 kilometers (km) (1-mile) of an active O&G well (Czolowski et al. 2017). In Colorado, this population is growing at a faster rate and may be at an economic disadvantage compared to Colorado’s general population (McKenzie et al. 2016).

Populations living in areas with O&G development may be exposed to several environmental stressors that have been associated with CVD. The modern extraction of O&G is a complex industrial process that requires diesel-powered equipment, trucks, and generators that continuously emit noise and exhaust (King 2012; Blair et al. 2018; Brown et al. 2015; Hays et al. 2017; McCawley 2015; Radtke et al. 2017; Witter et al. 2013). Furthermore, normal operations, maintenance activities, and leaks at on-site storage tanks, valves, and pipes result in emissions of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) (Halliday et al. 2016; Helmig et al. 2014; Collett and Hecobian 2016; Collett et al. 2016).

Diesel exhaust from O&G operations contributes to increased levels of ambient particulate matter of < 2.5 mircrons (PM2.5) (Brown et al. 2015, McCawley 2015). Numerous studies have provided evidence that increased short-term and long-term exposure to PM2.5 is associated with increases in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (Brook et al. 2010; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 2009). Noise levels measured in communities near O&G development sites have exceeded levels that have been associated with increased risk of CVD and hypertension (Blair et al. 2018, McCawley 2015, Radtke et al. 2017, Eriksson et al. 2012, van Kempen et al. 2012). Additionally, co-exposures to noise and PM2.5 have been associated with indicators of CVD, including increases in systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP, DBP) (Brook and Rajagopalan 2009; Chang et al. 2009; Münzel et al. 2014; Urch et al. 2005; van Kempen and Babisch 2012; Zanobetti et al. 2004), vasoconstriction (Brook et al. 2002; Foraster et al. 2017; Laurent et al. 2001; Nurnberger et al. 2002; Dales et al. 2007; Rundell et al. 2007) and systemic inflammation (Delfino et al. 2008; Delfino et al. 2009; Nemmar et al. 2010), as well as morbidity and mortality (Brook et al. 2010).

The VOCs emitted from O&G activity are primarily aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarons (Collett and Hecobian 2016; Collett et al. 2016; McKenzie et al. 2012). Inhalation exposure to hydrocarbons has been associated with alterations in cardiovascular physiology (Shin et al. 2015), increases in cardiovascular emergency department visits (Ye et al. 2017), and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (Bard et al. 2014; Harrison et al. 2016; Villeneuve et al. 2013; Xu et al. 2009). Additionally, individuals living in communities where modern O&G wells sites are located may also experience increases in psychosocial stress (Malin 2014; Malin et al. 2018; Perry 2012; Powers et al. 2014; Sangaramoorthy et al. 2016; Shelley 2014; Wilber 2012, Casey et al. 2018a, Casey et al. 2018b, Fisher et. al. 2018) that could also adversely affect SBP, DBP, vascular function, and systemic inflammation (Lu et al. 2013; Hänsel et al. 2010; Ranjit et al. 2007; Sparrenberger et al. 2008; von Känel et al. 2008; Yasui et al. 2007).

Epidemiological studies using administrative health data sources and indirect measures of exposure have observed associations between density of O&G wells and prevalence rates of cardiology inpatient hospital admission and congenital heart defects (Jemielita et al. 2016; McKenzie et al. 2014), as well as childhood leukemia, low birthweight, preterm birth, asthma, fatigue, migraines, and chronic rhinosinusitis (Casey et al. 2016; McKenzie et al. 2017; Rasmussen et al. 2016; Stacy et al. 2015; Tustin et al. 2016; Whitworth et al. 2017; Whitworth et al. 2018, Willis et. al. 2018, Currie et al. 2017, Hill 2018, Koehler et al. 2018). While studies on the health impacts of O&G development have indicated increases in self-reported cardiovascular and other types of symptoms (Ferrar et al. 2013; Rabinowitz et al. 2015; Saberi et al. 2014; Weinberger et al. 2017) and cardiovascular related hospital admissions (Jemielita et al. 2016), we are not aware of any studies that have directly measured markers of cardiovascular morbidity in a population near active O&G development. The objective of this study was to evaluate the association between indicators of CVD and the intensity of O&G development and production activity in Northeastern Colorado.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional study to evaluate associations between indicators of CVD and the intensity of O&G development and production activity within 16 km (10 miles) of a participant’s home. The 16-km buffer was selected based on previous studies (McKenzie et al. 2014; McKenzie et al. 2017; Stacy et al. 2015).

Study Population

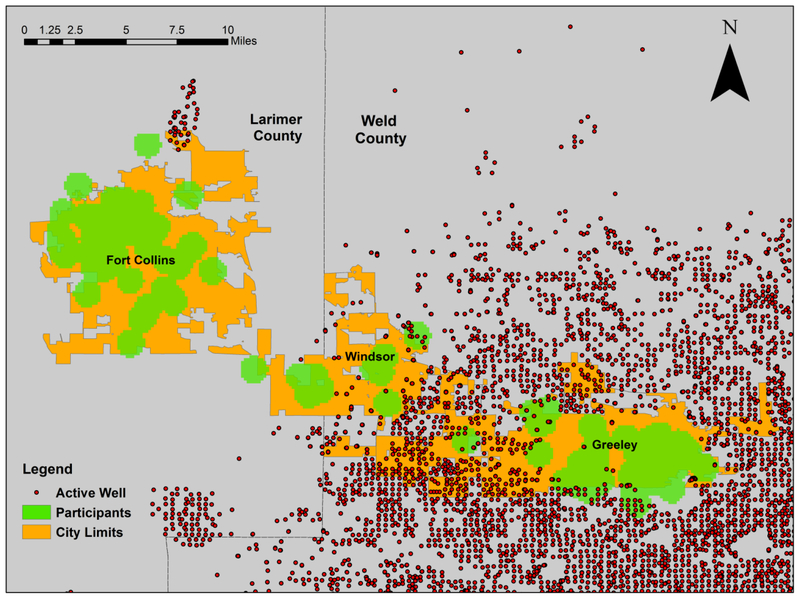

Between October 2015 and May 2016, we measured indicators of CVD in 97 men (n = 28) and non-pregnant women (n = 69) ≥ 18 years who did not smoke tobacco or marijuana, were not taking statins or other anti-inflammatory medication; were not occupationally exposed to dust, fumes, solvents, or O&G development activities; were not frequently exposed to environmental tobacco or marijuana smoke; and without a history of diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or chronic inflammatory diseases (such as asthma, arthritis, or severe allergies), and resided full-time in the city of Fort Collins, CO (n = 46), or in the cities of Windsor or Greeley, (n = 51) CO. As shown in Figure 1, most O&G wells were located in Greeley and Windsor; very few were located in Fort Collins. We obtained informed consent from all participants. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approved our study protocol (COMIRB protocol number 14–1880)

Figure 1.

Study area is located in Northeastern Colorado: 46 participants from Fort Collins with little oil and gas activity in 2016, 51 participants from Windsor and Greeley where active oil and gas development was ongoing as of June 2016.

Each participant completed up to three visits to our clinics between October 2015 and May 2016. At each visit, participants completed a questionnaire on their recent level of exercise, food, caffeine, medication, and alcohol intake; exposure to air pollutants and stress; and overall health (Supplemental Material). We measured the participant’s augmentation index, SBP, DBP, height, and weight and collected a blood sample for measures of systemic inflammation. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight (km)/[height (meters)]2.

Measures of Cardiovascular Health

We measured augmentation index and blood pressure with the SphygomoCor System (Atcor Medical Australia). To obtain these measures, the participant’s dominant arm was extended onto a flat surface, ensuring that the bend in the elbow was at heart level. For blood pressure, three measurements were collected and the reported SBP and DBP is the average of the 2nd and 3rd measurements. Augmentation index is a non-invasive method that reasonably approximates carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity, which is the gold standard for measuring arterial stiffness (Laurent et al. 2006; Yao et al. 2017). For the augmentation index, a micro-nanometer flattened the radial artery with gentle pressure and ten seconds of sequential pulse pressure waveforms were recorded and transformed into central aortic waveforms. The augmentation index was then calculated by dividing the augmented pressure by the pulse pressure and was expressed as a percentage. The reported augmentation index is the average of three measures that have an operator index >90% and are within 10 %of each other. Because augmentation index is inversely proportional to heart rate, augmentation indices were normalized to a standard heart rate of 75 bpm (Wilkenson 2000, Wilkenson 2002). Because heart rate may also mediate augmentation index, we also evaluated augmentation index without normalizing for heart rate (Stoner et al. 2014).

Measures of Systemic Inflammation

We measured a suite of inflammatory markers that have been associated with psychosocial stress and short-term air pollution exposure: Interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (Lu et al. 2013, Hänsel et al., 2010, Yasui et al. 2007, von Känel et al. 2008, Ranjit et al. 2007, Delfino et al. 2008, Delfino et al. 2009, Panasevich et al. 2009, Delfino et al. 2010). Venous blood was collected into EDTA tubes and centrifuged for 15 minutes at 2500 RPMs to separate the plasma, which was then stored at −80°C prior to analysis. An analyst blinded to the participant’s exposure measured IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α in duplicate using the commercially available R&D Biosystems (Minneapolis, Minnesota) Human Magnetic Luminex Performance Assay, High Sensitivity Cytokine kit, according to the manufacturer’s protocol ((Vasunilashorn et al. 2015). Plates were read using a Luminex MagPix System (Luminex Corporation, Austin Texas).

Exposure Assessment

We used the Google Maps Geocoding Application Programming Interface to geocode each participant’s street address with “Rooftop” accuracy. Google “Rooftop” accuracy indicates that the returned result is a precise geocode for which we have location information accurate down to street address precision (Google 2018). We obtained the latitude and longitude for all O&G wells within 16 km of each participant’s home (McKenzie et. al. 2012, Stacy et. al. 2015, McKenzie et al., 2017, Whitworth 2017) from the Colorado Oil and Gas Information System. The 16-km buffer allows us to incorporate the density of O&G operations into the exposure metric which can be relevant for additional stresses on a community with a high density of operations such as trucking traffic, population influx, and allocation of resources. The 16-km buffer also captures the geographical extent of Fort Collins, Windsor, and Greeley. Extending the buffer beyond 16 km would create overlap in community level stressors, such as increased traffic and community cohesion. Using the latitude and longitude coordinates of the O&G wells and each participant’s home, the distance between the participant’s home and each O&G well in the 16-km buffer was calculated with MATLAB 8.3 software. We then applied our intensity adjusted inverse distance weighted (IA-IDW) model, as described in Allshouse et al. (2017), to estimate the monthly relative intensity of O&G activity around the home of each participant from August 2015 through April 2016 (Allshouse et al. 2017) and used the mean of monthly intensities over the 9-month period to represent the estimated intensity. To evaluate CVD responses to chronic O&G related exposure, we began our exposure assessment two months prior to the first collection of biomarkers.

Because the wells included in our IA-IDW exposure metric for an individual are weighted by distance between the well and the residence, the wells that are closest to the individual will contribute the most to that individual’s metric. Our IA-IDW metric differs from methods that define an individual as exposed if they have a well within a given buffer without adjustment for distance or intensity of operations that occur at the well site (Currie et al. 2017 and Hill 2018). The final IA-IDW distribution was divided into tertiles (low, medium, and high) using cut points of 14.5 and 1242 well intensity per square km (km2) for subsequent statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis

For each biomarker, adherence to assumptions of the linear random intercept model was assessed visually using scatter plots, histograms, and QQ-plots of the standardized residuals. Cytokine levels were log-10 transformed to better align with the model’s assumption of Gaussian-distributed residuals (Diggle et. al. 2002). Because the systemic inflammation (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF –α) results did not meet assumptions for linear regression, we log-10-transformed the systemic inflammation concentrations prior to statistical analysis. The augmentation index, SBP, and DBP measurements met all assumptions for linear regression and were not transformed.

We used separate linear mixed models with random intercepts for each participant to evaluate the association between each health measurement (augmentation index, SBP, DBP, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF –α) and categorized intensity of O&G well activity (IAIDW) within 16 km of each participant’s home (low, medium, high). The medium and high tertiles were compared to the low tertile (the referent group). Linear mixed models allow for unbalanced data (i.e., unequal number of repeated measures assuming data points missing at random) (Fitzmaurice et al. 2004). All models were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity (white non-Hispanic vs. other/missing), BMI, education level (less than Bachelor’s degree vs. Bachelor’s degree or higher), income level (less than $50,000/year vs. $50,000/year or higher), and employment status (full-time employment vs. other). We evaluated our final models for residual spatial autocorrelation using semivariograms and found no evidence of residual spatial autocorrelation.

We performed sensitivity analysis on subsets of participants living only in Greeley or Windsor (no participants in the low IA-IDW tertile), reporting no illness in the past 24 hours, no alcohol use in the past 10 hours, no relocation of home in the past 3 months, or participants without an outlier result (defined as more than 1.5 times the IQR below and above the lower and upper bounds of the IQR, respectively). Based on participant questionnaire responses on their recent level of exercise, food, caffeine, medication, and alcohol intake, exposure to air pollutants and stress, and overall health, we evaluated interactions by the following categorical variables: the participant’s sex, age (18–27, 28–52, 53–80 years), unusual stress (yes, no), vigorous physical activity in the past 7-days (none, 75 or more minutes), moderate physical activity in the past 7-days (none, at least 150 minutes), use of prescription medications (none, 1 or more), exposure to other sources of VOCs (yes, no), and ingestion of food or drink 60 minutes prior to health measurement (yes, no) to evaluate for effect modification. Unusual stress was determined to be yes if the participant indicated in the past 7-days that they had experienced unusual stress or in the past 3-months they had relocated their home, changed jobs, had someone close to them die, or experienced a major change in their family. Sources of VOCs included paint or cleaning fumes, fires, burning fireplaces, candles or incense.

Data analysis was conducted using R v3.4.3(R core Team 2017). The mixed effect models were fitted using the nlme v3.1–131 package (Pinheiro et al. 2017).

Results

Characteristics of our study population are presented in Table 1. Participants were approximately evenly divided between residing in Fort Collins (47%), with limited O&G activity, or in Greeley or Windsor (53%), which are areas of active O&G development. The participants in the low exposure tertile resided exclusively in Fort Collins, while those in the high exposure tertile resided in Greeley or Windsor. Participants in the high exposure tertile were older and less educated than participants in the other tertiles. Participants in the low exposure tertile had lower incomes and were more likely to be working part-time than participants in the other tertiles.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics categorized by tertiles of intensity adjusted inverse distance weighted (IA-IDW) oil and gas well count within 16.1 kilometers of residence of each participant in 2016.

| Characteristic | IA-IDW | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (0 −14.5 well intensity/kilometer2) |

Medium (14.6–1242 well intensity/kilometer2) |

High (High > 1242 well intensity/kilometer2) |

|

| Number of Participants (N) | 32 | 33 | 32 |

| Community (N, percent) | |||

| Ft. Collins | 32 (100) | 14 (42) | 0 |

| Greeley & Windsor | 0 | 19 (58) | 32 (100) |

| Female (N, percent) | 23 (72) | 21 (64) | 25 (78) |

| Age (mean ± SD years) | 39 ± 19 | 37 ± 18 | 50 ± 17 |

| Race/Ethnicity (N, percent) | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 24 (75) | 26 (79) | 27 (84) |

| Other | 8 (25) | 6 (18) | 5 (16) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 |

| Body Mass Index (mean ± SD kg/m2) | 24 ± 4 | 25 ± 4 | 26 ± 6 |

| Annual Income (N, percent) | |||

| Less than $50,000 | 25 (78) | 11 (33) | 16 (50) |

| $50,000 or greater | 7 (22) | 21 (63) | 16 (50) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 |

| Education bachelor’s degree or higher (N, percent) | 30 (94) | 26 (79) | 21 (66) |

| Employment (N, percent) | |||

| Full-Time | 11 (34) | 11 (33) | 11 (34) |

| Part-Time | 17 (53) | 8 (24) | 8 (25) |

| Not Working | 4 (13) | 14 (42) | 13 (41) |

| Participants completing each visit (N, percent) | |||

| 1 | 32 (100) | 33 (100) | 32 (100) |

| 2 | 30 (94) | 27 (82) | 25 (78) |

| 3 | 28 (88) | 25 (76) | 28 (88) |

IA-IDW = intensity adjusted inverse distance weighted count of oil and gas wells within 16.1 kilometers of residence N = number, SD = standard deviation

Both crude and adjusted estimates indicate that augmentation index is associated with greater O&G activity around a participant’s residence, as represented by IA-IDW (Table 2). Mean augmentation index, adjusted for only sex and age differed by 8.7% (95% CI: 4.1, 13.4%) and 6.9% (95%CI: 2.1, 11.7%) between the high and medium, respectively, and low IA-IDW tertiles. Further adjustment for race/ethnicity, BMI, education, income and employment status attenuated the results. Fully adjusted mean augmentation index differed by 6.0% (95% CI: 0.6, 11.4%) and 5.1% (95%CI: −0.1, 10.4%) between the high and medium, respectively, and low IA-IDW tertiles. We observed similar results for the mean augmentation index not normalized for heart rate, although the difference between tertiles was attenuated (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 2.

Biomarker means and differences for each tertile of intensity adjusted inverse distance weighted oil and gas well count (IA-IDW) within 16.1 kilometers of residence of each participant in 2016. Differences between means compared to low IA-IDW tertile for each measure of cardiovascular health, i.e., augmentation index, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure.

| Biomarker (N) | Mean (95% Confidence Interval) | Difference between means (95% Confidence Interval) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low1 N = 92 | Medium1 N = 81 | High1 N = 81 | Low1 N =92 | Medium1 N = 81 | High1 N = 81 | |

| Augmentation Index (percent at HR 75) | ||||||

| Crude | 5.0 (0.7, 9.3) |

16.8 (12.5,21.0) |

14.7 (10.4, 19.0) |

Referent | 11.8 (5.7, 17.9) |

9.7 (3.5, 15.9) |

| Adjusted2 | 9.1 (5.6, 12,6) |

15.9 (12.4, 19.5) |

17.8 (14.4, 21.0) |

6.9 (2.1, 11.7) |

8.7 (4.1, 13.4) |

|

| Adjusted3 | 10.9 (5.3, 16.5) |

16.0 (11.0, 21.1) |

16.9 (11.8, 22.0) |

5.1 (−0.1, 10.4) |

6.0 (0.6, 11.4) |

|

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | ||||||

| Crude | 119 (115, 122) |

120 (116, 124) |

123 (119, 127) |

Referent | 1 (−4, 7) |

5 (−1, 10) |

| Adjusted2 | 117 (113, 121) |

116 (112, 120) |

122 (118, 126) |

−1 (−6, 4) |

5 (0, 10) |

|

| Adjusted3 | 117 (112, 123) | 116 (112, 121) | 120 (115, 125) | −1 (−6, 4) | 3 (−3, 8) | |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | ||||||

| Crude | 73 (70, 75) |

73 (70, 75) |

77 (74, 79) |

Referent | 0 (−4, 3) |

4 (0,7) |

| Adjusted2 | 72 (70, 74) |

71 (68, 74) |

76 (73, 78) |

−1 (−4, 3) |

4 (0,7) |

|

| Adjusted3 | 74 (70, 78) |

73 (70, 77) |

76 (73, 80) |

−1 (−4, 3) |

2 (−1, 6) |

|

Tertile of IA-IDW = intensity adjusted inverse distance weighted count of oil and gas wells within 16.1 kilometers of residence: Low = 0 – 14.5 well intensity/kilometer2, Medium 14.6 – 1242 well intensity/kilometer2, High > 1242 well intensity/kilometer2.

Adjusted for age and sex

Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, BMI, education, income, and employment.

HR= heart rate, mm Hg = millimeters of mercury, N = number

Systolic blood pressure, adjusted for only sex and age differed by 5 mm Hg (95%CI: 0, 10 mm Hg) and −1 mm Hg (95% CI: −6, 4 mm Hg) between the high and medium, respectively, and low IA-IDW tertiles. Further adjustment slightly attenuated the results. Fully adjusted mean SBP differed by 3 mm Hg (95% CI: −3, 8 mm Hg) and −1 mm Hg (95% CI: −6, 4 mm Hg) between the high and medium, respectively, and low IA-IDW tertiles.

Diastolic blood pressure, adjusted for only sex and age differed by 4 mm Hg (95%CI: 0, 7 mm Hg) and −1 mm Hg (95% CI: −−4, 3 mm Hg) and between the high and medium, respectively, and low IA-IDW tertiles. Further adjustment slightly attenuated the results. Fully adjusted mean DBP differed by 2 mm Hg (95% CI: −1, 6 mm Hg) and −1 mm Hg (95%CI: −4, 3 mm Hg) (Table 2).

The greatest crude and adjusted mean IL-1β, and α-TNF measurements were observed for participants in the highest exposure tertile (Table 3). We did not observe an association between IL-6 and IL-8 plasma concentrations and IA-IDW.

Table 3.

Biomarker means and differences for each tertile of intensity adjusted inverse distance weighted oil and gas well count (IA-IDW) within 16.1 kilometers of residence of each participant in 2016. Difference between means compared to low IA-IDW tertile, and each individual marker of inflammation, i.e., interleukins −1β, −6, −8, and TNF –α.

| Biomarker | Mean (95% Confidence Interval) |

Difference between means (95% Confidence Interval) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low2 | Medium2 | High2 | Low2 | Medium2 | High2 | |

| Observations (N) | 92 | 81 | 81 | 92 | 81 | 81 |

| Interleukin-1β (pg/ml) | ||||||

| Crude | 0.552 (0.504, 0.604) | 0.560 (0.510, 0.614) | 0.623 (0.567, 0.684) | Referent | 0.008 (−0.063, 0.080) | 0.071 (−0.005,0.149) |

| Adjusted1 | 0.546 (0.465, 0.637) | 0.557 (0.481, 0.642) | 0.610 (0.527, 0.701) | 0.012 (−0.070, 0.091) | 0.064 (−0.022, 0.149) | |

| Interleukin-6 (pg/ml) | ||||||

| Crude | 0.815 (0.695, 0.950) | 0.889 (0.757, 1.04) | 0.934 (0.794, 1.09) | Referent | 0.075 (−0.114, 0.266) | 0.119 (−0.076,0.318) |

| Adjusted1 | 0.964 (0.774, 1.19) | 0.842 (0.689, 1.02) | 0.902 (0.740, 1.09) | −0.122 (−0.311, 0.056) | −0.062 (−0.256, 0.125) | |

| Interleukin-8 (pg/ml) | ||||||

| Crude | 5.03 (4.42, 5.71) | 4.95 (4.34, 5.61) | 5.41 (4.74, 6.16) | Referent | −0.082 (−0.991, 0.826) | 0.384 (−0.570, 1.35) |

| Adjusted1 | 5.67 (4.54, 6.99) | 4.71 (3.85, 5.69) | 5.59 (4.58, 6.76) | −0.963 (−2.08, 0.070) | −0.079 (−1.25, 1.05) | |

| Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (pg/ml) | ||||||

| Crude | 4.57 (4.02, 5.17) | 5.13 (4.53, 5.81) | 5.19 (4.56, 5.88) | Referent | 0.568 (−0.289, 1.44) | 0.622 (−0.245, 1.50) |

| Adjusted1 | 4.70 (3.79, 5.75) | 4.82 (3.99, 5.78) | 5.03 (4.15, 6.04) | 0.124 (−0.799, 1.02) | 0.329 (−0.632, 1.27) | |

Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, BMI, education, income, and employment.

IA-IDW = intensity adjusted inverse distance weighted count of oil and gas wells within 16.1 kilometers of residence: Low = 0 – 14.5 well intensity/kilometer2, Medium 14.6 – 1242 well intensity/kilometer2, High > 1242 well intensity/kilometer2.

% = percent, pg/ml = picograms per milliliter, TNF = tumor necrosis factor

In a sensitivity analysis for participants living in Greeley or Windsor, reporting no illness in the past 24 hours, no alcohol use in the past 10 hours, no relocation of home in the past 3 months, or with participants with outliers removed, we observed results similar to the results for the whole population (Supplemental Tables 2–6), with one exception. With the exclusion of participants with outliers, the highest adjusted mean TNF-α plasma concentration was still observed in the high exposure tertile; however, the adjusted mean in the medium exposure tertile was lower than in the low exposure tertile.

We did not observe interactions between IA-IDW and the participant’s sex, age, level of stress, level of physical activity, use of prescription medications, exposure to other sources of VOCs, and ingestion of food or drink 60 minutes prior to measurement of cardiovascular indicators with one exception. We found that use of prescription medications attenuated the difference in SBP (p-value for interaction = 0.113) and DPB (p-value for interaction = 0.564) between exposure tertiles (Table 4). For participants not taking any type of prescription medication, the adjusted mean SBP differed by 6 mm Hg (95% CI: 0.1, 13 mm Hg) and 1 mm Hg (95% CI: −6, 8 mm Hg) between the high and medium, respectively, and low exposure tertiles. The adjusted mean DBP differed by 4 mm Hg (95%CI: −1, 8 mm Hg) and 0.4 mm Hg (95%CI: −5, 6 mm Hg) between the high and medium, respectively, and low exposure tertiles. For participants taking prescription medications, the differences between the exposure tertiles were smaller and consistent with a null result. While we did not observe interactions between IA-IDW and the participant’s sex, we did observe larger differences between high, medium, and low IA-IDW tertiles for augmentation index, SBP, and DBP in men than women (Supplemental Table 7).

Table 4.

Biomarker means and differences for each tertile of intensity adjusted inverse distance weighted oil and gas well count (IA-IDW) within 16.1 kilometers of residence of each participant in 2016. Difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP, respectively) means compared to low IA-IDW tertile, and SBP and DBP results stratified by prescription medication use1.

| Mean (95% Confidence Interval) |

Difference between means (95% Confidence Interval) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomarker | Low2 | Medium2 | High2 | Low2 | Medium2 | High2 |

| Observations (N) | 87 | 81 | 81 | 87 | 81 | 81 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) p= 0.1133 | ||||||

| No prescription medications (N=108) | 115 (109, 120) | 115 (109, 122) | 121 (116, 126) | Referent | 1 (−6, 8) | 6 (0.1, 13) |

| One or more prescription medications (N=141 | 119 (113, 124) | 117 (112, 122) | 119 (114, 125) | −2 (−8, 3) | −0.6 (−7, 5) | |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) p = 0.5643 | ||||||

| No prescription medications (N=108) | 72 (68, 77) | 73 (68, 77) | 76 (72, 80) | Referent | 0.4 (−5, 6) | 4 (−1, 8) |

| One or more prescription medications (N=141) | 75 (71, 79) | 73 (70, 77) | 76 (72, 80) | −2 (−6, 3) | 1 (−3, 6) | |

All results adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, BMI, education, income, and employment.

IA-IDW = intensity adjusted inverse distance weighted count of oil and gas wells within 16.1 kilometers of residence: Low = 0 – 14.5 well intensity/kilometer2, Medium 14.6 – 1242 well intensity/kilometer2, High > 1242 well intensity/kilometer2.

p-value for interaction between prescription medication use and IA-IDW tertile.

mm Hg = millimeters of mercury, N = number of observations

Discussion

In this population, we observed positive associations between the intensity of O&G activity within 16 km of a participant’s homes and some indicators of cardiovascular disease. Augmentation index was highest in participants living in areas with the greatest O&G activity. Similarly, both SBP and DBP were highest in the subset of participants experiencing the greatest levels of O&G activity and who were not taking prescription medications. While IL-1β and TNF-α plasma concentrations also were highest in participants living in areas with the greatest O&G activity, wide confidence intervals that include zero warrant caution in interpretation. In this population, we did not observe an association between IL-6 and IL-8 plasma concentrations and intensity of O&G activity.

Because this is the first study to evaluate the association between indicators of CVD and intensity of O&G activities, there are no previous results available for a direct comparison. However, our results are consistent with the observed increase in prevalence rates of cardiology inpatient hospital admission in areas of O&G activity (Jemielita et al. 2016). Additionally, because O&G activities are associated with increases in noise (Blair et al. 2018; Hays et al. 2017; Radtke et al. 2017; Witter et al. 2013), air pollution (Brown et al. 2015; Helmig et al. 2014; Collett and Hecobian 2016; Collett et al. 2016; McCawley 2015) and psychosocial stress (Hirsch et al. 2018; Malin et al. 2018; Mayer 2017; Fisher et al. 2018, Casey et al. 2018a, Casey et al. 2018b), we can compare our results to previous studies on exposure to these environmental stressors.

Our augmentation index results are similar to the 5.1–7.8% increases that have been reported following exposure of welders to an 8-hour time-weighted average PM2.5 concentration of 390 μg/m3 or exposure of volunteers to diesel exhaust concentrations in an exposure chamber of 350 μg/m3 (Fang et al. 2008; Lundback et al. 2009). The one study that evaluated the association between augmentation index and noise did not find evidence for an association (Khoshdel et al. 2016). Studies evaluating the cumulative impact of noise, stress, and PM2.5 experienced by our participants are lacking.

For participants not taking a prescription medication, our blood pressure results are similar to what has been reported for exposure to PM2.5, noise, and psychosocial stress. Following 5 −10 μg/m3 increases in modelled or direct measures of personal ambient PM2.5 exposures in non-occupational adult populations, studies have reported increases in SBP ranging from 0.2 to 1.42 mm Hg and DBP ranging from 0 to 0.44 mm Hg (Auchincloss et al. 2008; Brook et al. 2010; Chan et al. 2015; Honda et al. 2018). In one study that considered the modifying effect of taking blood pressure medication, SBP and DBP increased by 6.01 and 3.42 mm Hg four days following a 10 μg/m3 increase PM2.5 exposure measured at central locations (Dvonch et al. 2009). Further study of this population found that self-reported levels of stress modified the association between exposure to PM2.5 and blood pressure (Hicken et al. 2014). For each 10 μg/m3 increase in 2-day prior PM2.5 exposure, participants reporting low stress showed a 2.94 mm Hg increase in SBP and those reporting high stress showed a 9.05 mm Hg increase in SBP (Hicken et al. 2014). Studies of adult volunteers exposed to noise have observed 1.43 and 1.40 mm Hg increases SBP and DBP, respectively, per 5-dBA increase in 24-hour noise exposure (Chang et al. 2009), and a 4.1 to 6.2 mm Hg and 7.4 mm Hg increases in SBP and DBP, respectively, following exposure to nighttime noise (Haralabidis et al. 2008; Schmidt et al. 2015). Studies on the effect of exposure to job strain and psychosocial stress have observed increases in SBP and DBP ranging from 1.2 to 7.7 mm Hg and 0.8 to 7 mm Hg, respectively (Ford et al. 2016; GilbertOuimet et al. 2014).

The increases in TNF-α plasma concentrations in participants in the highest exposure tertile are in the range of what has been reported following exposure to PM2.5.and other air pollutants and stress (Delfino et al. 2008; Delfino et al. 2009; Grossi et al. 2003; Panasevich et al. 2009; Steptoe et al. 2002; Yasui et al. 2007). Studies have observed increases in TNF-α ranging from 0.36 to 1.06 pg/mL following exposure to several components of diesel air pollution (particles, EC, Organic Carbon, CO, and NOx) for participants in the upper 25th percentile of TNF-α levels (Delfino et al. 2008; Delfino et al. 2009). Additionally, 1.8 to 15.7% increases in TNF-α levels have been observed to follow exposure to NO2 and PM10 (Panasevich et al. 2009). Increases in TNF-α levels ranging from 5.4 to 6.5% have been observed following acute stress and burnout (Grossi et al. 2003; Steptoe et al. 2002). The differences we observed in plasma concentrations of IL-1β between exposure tertiles are less than an 88% increase observed in women with psychological symptoms (Yasui et al. 2007). We did not observe the elevations in IL-6, that have been observed in previous studies on air pollutants and psychosocial stress (Delfino et al. 2008; Delfino et al. 2009; Delfino et al. 2010; Panasevich et al. 2009).

Biological Plausibility and Clinical Implications

Acute exposure to PM2.5, noise, and psychosocial stress all can promote activation of the sympathetic nervous system, systemic inflammation, and oxidative stress, which, in turn, can result in autonomic nervous imbalance and enhance thrombotic and blood coagulation. This can result in acute (short-term) to chronic (longer term) elevation of blood pressure (Brook 2009, Brook 2017, Cuffee et al. 2014).

While the clinical implications of our results are uncertain, the CVD indicators explored in our study are important markers of cardiovascular health and the observed responses in our population are in the range that have been associated with increased risk of CVD. Augmentation index is a measure of atrial stiffness and is predictive of all cause and overall cardiovascular mortality as well as CVD (Laurent et al. 2006). Differences in augmentation index of 4.3% have been associated with a 20% increase in cardiovascular events in hypertensive diabetics (Yang et al. 2017). Cardiovascular mortality doubles for each 20 mm Hg and 10 mm Hg increase in SBP and DBP, respectively (Whelton et al. 2017) and each 10 mm Hg increase in DBP and SBP increases the risk of CVD and stroke (Franklin et al. 2001; McCarron et al. 2000) Because associations between blood pressure and risk of CVD are on a continuous gradient (Whelton et al. 2017) and because millions of people may be affected given the growing intesection of O&G development and residential areas (Czolowski et al. 2017; McKenzie et al. 2016), the relatively small increases in SBP and DBP observed in this study could indicate substantial adverse impacts on overall cardiovascular risk at the national and possibly global public health level (Brook 2017).

Strengths and Limitations

Because our participants provided information on co-exposures and potential confounders each time they provided samples for biomarker measurements, we were able to assess the impact of many potential confounders and effect modifiers on these results, although residual confounding may remain. We were able to estimate the level of intensity of O&G activities within 16 km of each participant’s home by applying a spatiotemporal industrial model developed to address this issue and that incorporates region-specific, data-driven activity and production information to estimate the relative intensity of air pollution emissions across four distinct phases of O&G activity (i.e., construction, drilling, completions, and production) (Allshouse et al. 2017). This model’s O&G intensity estimates are strongly correlated with measured VOCs over all phases of well development and yields a 19-times greater dynamic range in exposure intensity estimates than other proximity-based methods (Allshouse et al. 2017). Therefore, we have confidence that this model is able to better categorize exposure among individuals, and therefore reduce exposure misclassification. However, the model has not been validated with noise or psychosocial stressor measures.

Our cross sectional study design, small sample size, the potential for residual confounding, and lack of direct measures of noise and air pollution are important limitations of this analysis. Because of the small sample size, and potential for residual confounding and exposure misclassification, our results for IL-6 and IL-8 may be biased towards the null. The participants who volunteered for our study may be different from nonparticipants in many ways, so our results may not be applicable to the general population. Our study population of mostly female, healthy, adult, English-speakers in Northeast Colorado may further limit the generalizability of our results. There is limited evidence that blood pressure and inflammatory responses to chronic stress, noise, and PM2.5 may be more pronounced in men than women (Gilbert-Ouimet et al. 2014, Hicken et al 2014, Hajat 2015, van Kempen and Babisch 2012) and our results stratified by sex support this observation (Supplemental table 7). Therefore, the over representation of women in our study may have attenuated the results towards the null. Because we did not directly measure exposure to noise and air pollution, our study was not able to elucidate possible mechanisms or environmental stressors that might be involved. Additionally, limitations in our exposure estimate and sample size prevent us from evaluating dose-response effects. Lastly, because we conducted numerous statistical tests, we recognize that we could observe statistically significant associations by chance. These limitations can be addressed in the future by using more robust study designs in larger, population-based studies of residents exposed to oil and gas development.

Conclusion

In this cross-sectional study of 97 participants living in Northeast Colorado in 2016, we observed evidence supporting an association between the intensity of O&G activity and several indicators of cardiovascular disease.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Augmentation index increased as O&G activity intensity increased.

SBP increased with O&G activity intensity in participants not taking medication.

DBP increased with O&G activity intensity in participants not taking medication.

IL-1β plasma concentrations peaked in the highest O&G activity intensity area.

TNF-α plasma concentrations peaked in the highest O&G activity intensity area.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by support from the National Institutes for Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) (R21-ES025140–01). It was also supported by data and resources from the AirWaterGas Sustainability Research Network funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under Grant No. CBET-1240584. Any opinions, findings conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NIEHS, the National Institutes of Health, or the NSF.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of competing financial interests: The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

References

- Adgate JL, Goldstein BD, McKenzie LM. 2014. Potential public health hazards, exposures and health effects from unconventional natural gas development. Environ. Sci. Technol 48:8307–8320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allshouse WB, Adgate JL, Blair BD, McKenzie LM. 2017. Spatiotemporal industrial activity model for estimating the intensity of oil and gas operations in Colorado. Environ. Sci. Technol 51:10243–10250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchincloss AH, Diez Roux AV, Dvonch JT, Brown PL, Barr RG, Daviglus ML, et al. 2008. Associations between recent exposure to ambient fine particulate matter and blood pressure in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Environ. Health Perspect. 116:486–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bard D, Kihal W, Schillinger C, Fermanian C, Ségala C, Glorion S, et al. 2014. Trafficrelated air pollution and the onset of myocardial infarction: Disclosing benzene as a trigger? A small-area case-crossover study. PloS one 9:e100307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair B, Brindley S, Dinkeloo E, Mckenzie L, Adgate J. 2018. Residential noise from oil and gas well construction and drilling. J. Exposure Sci. Environ. Epidemiol 10.1038/s41370-018-0039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD, Brook JR, Urch B, Vincent R, Rajagopalan S, Silverman F. 2002. Inhalation of fine particulate air pollution and ozone causes acute arterial vasoconstriction in healthy adults. Circulation 105:1534–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD, Rajagopalan S. 2009. Particulate matter, air pollution, and blood pressure. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens 3:332–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD, Bard RL, Burnett RT, Shin HH, Vette A, Croghan C, et al. 2010. Differences in blood pressure and vascular responses associated with ambient fine particulate matter exposures measured at the personal versus community level. Occup. Environ. Med 68:224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD. 2017. The environment and blood pressure. Cardiology Clinics 35:213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DR, Lewis C, Weinberger BI. 2015. Human exposure to unconventional natural gas development: A public health demonstration of periodic high exposure to chemical mixtures in ambient air. J. Environ. Sci. Health, Part A 50:460–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey JA, Wilcox HC, Hirsch AG, Pollak J, and Schwartz BS 2018. Associations of unconventional natural gas development with depression symptoms and disordered sleep in Pennsylvania. Scientific Reports 8 (1): 11375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey JA, Goldman-Mellor S, and Catalano R 2018. Association between Oklahoma earthquakes and anxiety-related Google search epidsodes. Environmental Epidemiology 2 (2): e016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey JA, Savitz DA, Rasmussen SG, Ogburn EL, Pollak J, Mercer DG, et al. 2016. Unconventional natural gas development and birth outcomes in Pennsylvania, USA. Epidemiology 27:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesari M, Penninx BWJH, Newman AB, Kritchevsky SB, Nicklas BJ, Sutton-Tyrrell K, et al. 2003. Inflammatory markers and cardiovascular disease (the health, aging and body composition [Health ABC] study). Am. J. Cardiol 92:522–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SH, Van Hee VC, Bergen S, Szpiro AA, DeRoo LA, London SJ, et al. 2015. Longterm air pollution exposure and blood pressure in the sister study. Environ. Health Perspect.123:951–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang T, Wang V, Hwang B, Yen H, Lai J, Liu C, et al. 2009. Effects of co-exposure to noise and mixture of organic solvents on blood pressure. J. Occup. Health 51:332–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collett JH, Ham J, Hecobian A 2016. North front range oil and gas air pollutant emission and dispersion study. Available at: https://www.colorado.gov/airquality/tech_doc_repository.aspx?action=open&file=CSU_NFR_Report_Final_20160908.pdf.

- Collett JH, Ham J, Pierce J, Hecobian A, Clements A, Shonkwiler K, Zhou Y, Desyaterik Y, MacDonald L, Wells B, Hilliard N, Tigges M, Bibeau B, Kirk C. 2016. Characterizing emissions from natural gas drilling and well completion operations in Garfield County, Co. Available at: https://www.garfield-county.com/airquality/documents/CSU-GarCo-Report-Final.pdf

- Cuffee Y, Ogedegbe C, Williams N, Ogedegbe G, Schoenthaler A 2014. Psychosocial Risk Factors for Hypertension: an Update of the Literature. Curr. Hypertens. Rep 16:483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie J, Greenstone M, and Meckel K 2017. Hydraulic fracturing and infant health: New evidence from Pennsylvania. Sci. Adv 3 (12):e1603021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czolowski ED, Santoro RL, Srebotnjak T, Shonkoff SB. 2017. Toward consistent methodology to quantify populations in proximity to oil and gas development: A national spatial analysis and review. Environ. Health Perspect.125:086004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dales R, Liu L, Szyszkowicz M, Dalipaj M, Willey J, Kulka R, et al. 2007. Particulate air pollution and vascular reactivity: The bus stop study. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 81:159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfino RJ, Staimer N, Tjoa T, Polidori A, Arhami M, Gillen DL, et al. 2008. Circulating biomarkers of inflammation, antioxidant activity, and platelet activation are associated with primary combustion aerosols in subjects with coronary artery disease. Environ. Health Perspect. 116:898–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfino RJ, Staimer N, Tjoa T, Gillen DL, Polidori A, Arhami M, et al. 2009. Air pollution exposures and circulating biomarkers of effect in a susceptible population: Clues to potential causal component mixtures and mechanisms. Environ. Health Perspect. 117:1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfino RJ, Staimer N, Tjoa T, Arhami M, Polidori A, Gillen DL, et al. 2010. Associations of primary and secondary organic aerosols with airway and systemic inflammation in an elderly panel cohort. Epidemiology 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang KY, Zeger SL: Analysis of Longitudinal Data Oxford, Clarendon Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dvonch JT, Kannan S, Schulz AJ, Keeler GJ, Mentz G, House J, et al. 2009. Acute effects of ambient particulate matter on blood pressure. Differential Effects Across Urban Communities. Hypertension 53:853–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang SC, Eisen EA, Cavallari JM, Mittleman MA, Christiani DC. 2008. Acute changes in vascular function among welders exposed to metal-rich particulate matter. Epidemiology 19:217–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrar KJ, Kriesky J, Christen CL, Marshall LP, Malone SL, Sharma RK, et al. 2013. Assessment and longitudinal analysis of health impacts and stressors perceived to result from unconventional shale gas development in the Marcellus Shale region. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 19:104–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. 2004. Applied longitudinal analysis:John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher MP, Mayer A, Vollet K, Hill EL, Haynes EN. 2018. Psychosocial implications of unconventiona natural gas development: Quality of life in Ohio’s Guernsey and Noble Counties. Journal of Environmental Psychology 55: 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- Foraster M, Eze IC, Schaffner E, Vienneau D, Héritier H, Endes S, et al. 2017. Exposure to road, railway, and aircraft noise and arterial stiffness in the SAPALDIA study: Annual average noise levels and temporal noise characteristics. Environ. Health Perspect. 126: 097004-1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CD, Sims M, Higginbotham JC, Crowther MR, Wyatt SB, Musani SK, et al. 2016. Psychosocial factors are associated with blood pressure progression among African Americans in the Jackson Heart Study. Am. J. Hypertens 29:913–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin SS, Larson MG, Khan SA, Wong ND, Leip EP, Kannel WB, et al. 2001. Does the relation of blood pressure to coronary heart disease risk change with aging? The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 103:1245–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert-Ouimet M xe, Trudel X, Brisson C, Milot A xe, et al. 2014. Adverse effects of psychosocial work factors on blood pressure: Systematic review of studies on demandcontrol-support and effort-reward imbalance models. Scand. J. Work, Environ. Health 40:109–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases C. 2018. 2017. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet 390:1151–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases C. 2018. The burden of cardiovascular diseases among US states, 1990–2016. JAMA cardiology 3:375–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Google. 2018. Google geocoding api developer guide. Available: https://developers.google.com/maps/documentation/geocoding/intro [accessed 07/16/2018 2018].

- Grossi G, Perski A, Evengård B, Blomkvist V, Orth-Gomér K. 2003. Physiological correlates of burnout among women. J. Psychosom. Res 55:309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday HS, Thompson AM, Wisthaler A, Blake D, Hornbrook RS, Mikoviny T, et al. 2016. Atmospheric benzene observations from oil and gas production in the Denver Julesburg Basin in July and August 2014. J. Geophys. Res., C: Oceans Atmos. 121:11055–11074. [Google Scholar]

- Hänsel A, Hong S, Cámara RJA, von Känel R. 2010. Inflammation as a psychophysiological biomarker in chronic psychosocial stress. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 35:115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haralabidis AS, Dimakopoulou K, Vigna-Taglianti F, Giampaolo M, Borgini A, Dudley ML, et al. 2008. Acute effects of night-time noise exposure on blood pressure in populations living near airports. Eur. Heart J. 29:658–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison R, Retzer K, Kosnett MJ, et al. 2016. Sudden deaths among oil and gas extraction workers resulting from oxygen deficiency and inhalation of hydrocarbon gases and vapors — United States, january 2010–march 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65:6–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes EN, McKenzie LM, Malin SA, Cherrie JW. 2017. A historical perspective of unconventional oil and gas extraction and public health In: Oxford Encyclopedia of Environmental Science:Oxford: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hays J, McCawley M, Shonkoff SB. 2017. Public health implications of environmental noise associated with unconventional oil and gas development. Sci. Total Environ. 580:448–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmig D, Thompson C, Evans J, Park J-H. 2014. Highly elevated atmospheric levels of volatile organic compounds in the Uintah Basin, Utah. Environ. Sci. Technol 48:47074715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicken MT, Dvonch JT, Schulz AJ, Mentz G, Max P. 2014. Fine particulate matter air pollution and blood pressure: The modifying role of psychosocial stress. Environ. Res 133:195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill EL. 2018. Shale gas development and infant health: evidence from Pennsylvania. Journal of health economics 61: 134–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JK, Bryant Smalley K, Selby-Nelson EM, Hamel-Lambert JM, Rosmann MR, Barnes TA, et al. 2018. Psychosocial impact of fracking: A review of the literature on the mental health consequences of hydraulic fracturing. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 16:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Honda T, Pun VC, Manjourides J, Suh H. 2018. Associations of long-term fine particulate matter exposure with prevalent hypertension and increased blood pressure in older americans. Environ. Res 164:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemielita T, Gerton GL, Neidell M, Chillrud S, Yan B, Stute M, et al. 2016. Unconventional gas and oil drilling is associated with increased hospital utilization rates. PloS one 10:e0131093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshdel AR, Mousavi-Asl B, Shekarchi B, Amini K, Mirzaii-Dizgah I. 2016. Arterial indices and serum cystatin c level in individuals with occupational wide band noise exposure. Noise Health 18:362–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King GE. Hydraulic fracturing 101: What every representative, environmentalist, regulator, reporter, investor, university researcher, neighbor and engineer should know about estimating frac risk and improving frac performance in unconventional gas and oil wells. 2012. Woodlands, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Koehler K, Ellis JH, Casey JA, Manthos D, Bandeen-Roche K, Platt R, and Schwartz BS. 2018. Exposure assessment using secondary data sources in unconventional natural gas development and health studies. Environ. Sci. Technol 52 (10): 6061–6069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent S, Boutouyrie P, Asmar R, Gautier I, Laloux B, Guize L, et al. 2001. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hypertensive patients. Hypertension 37:1236–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent S, Cockcroft J, Van Bortel L, Boutouyrie P, Giannattasio C, Hayoz D, et al. 2006. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: Methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur. Heart J. 27:2588–2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X-T, Zhao Y-X, Zhang Y, Jiang F. 2013. Psychological stress, vascular inflammation, and atherogenesis: Potential roles of circulating cytokines. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol 62:6–12 10.1097/FJC.1090b1013e3182858fac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundback M, Mills NL, Lucking A, Barath S, Donaldson K, Newby DE, et al. 2009. Experimental exposure to diesel exhaust increases arterial stiffness in man. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 6:928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malin S 2014. There’s no real choice but to sign: Neoliberalization and normalization of hydraulic fracturing on Pennsylvania farmland. J. Environ. Stud. Sci 4:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Malin SA, Ryder S, Hall P. 2018. Contested Colorado: A multi-level analysis of community responses to niobrara shale oil production In: Fractured Communities: Risks, Impacts, and Mobilization of Protest Against Hydraulic Fracking in US Shale Regions, (Ladd A, ed). New Brunswick, NJ:Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer A 2017. Quality of life and unconventional oil and gas development: Towards a comprehensive impact model for host communities. The Extractive Industries and Society 4:923–930. [Google Scholar]

- McCarron P, Smith GD, Okasha M, McEwen J. 2000. Blood pressure in young adulthood and mortality from cardiovascular disease. Lancet 355:1430–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCawley M 2015. Air contaminants associated with potential respiratory effects from unconventional resource development activities. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 36:379387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie LM, Witter RZ, Newman LS, Adgate JL. 2012. Human health risk assessment of air emissions from development of unconventional natural gas resources. Sci. Total Environ. 424:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie LM, Guo R, Witter RZ, Satvitz DA, Newman LS, Adgate JL. 2014. Birth outcomes and maternal residential proximity to natural gas development in rural Colorado. Environ. Health Perspect. 122:412–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie LM, Allshouse WB, Burke T, Blair BD, Adgate JL. 2016. Population size, growth, and environmental justice near oil and gas wells in Colorado Environ. Sci. Technol 50:11471–11480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie LM, Allshouse WB, Byers TE, Bedrick EJ, Serdar B, Adgate JL. 2017. Childhood hematologic cancer and residential proximity to oil and gas development. PloS one 12:e0170423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münzel T, Gori T, Babisch W, Basner M. 2014. Cardiovascular effects of environmental noise exposure. Eur. Heart J. 35:829–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemmar A, Al-Salam S, Zia S, Dhanasekaran S, Shudadevi M, Ali BH. 2010. Timecourse effects of systemically administered diesel exhaust particles in rats. Toxicol. Lett 194:58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurnberger J, Keflioglu-Scheiber A, Opazo Saez AM, Wenzel RR, Philipp T, Schafers RF. 2002. Augmentation index is associated with cardiovascular risk. J. Hypertens 20:2407–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panasevich S, Leander K, Rosenlund M, Ljungman P, Bellander T, de Faire U, et al. 2009. Associations of long- and short-term air pollution exposure with markers of inflammation and coagulation in a population sample. Occup. Environ. Med 66:747753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry SL. 2012. Development, land use, and collective trauma: The Marcellus Shale gas boom in rural Pennsylvania. Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment 34:81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, Team Rc. 2017. _nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models_. Part R package version 31–131. [Google Scholar]

- Powers M, Saberi P, Pepino R, Strupp E, Bugos E, Cannuscio CC. 2014. Popular epidemiology and “fracking”: Citizens’ concerns regarding the economic, environmental, health and social impacts of unconventional natural gas drilling operations. J Community Health 40:535–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R core Team. 2017. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria:R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz P, Slizovskiy I, Lamers V, Trufan S, Theodore H, Dziura J, et al. 2015. Proximity to natural gas wells and reported health status: Results of a household survey in Washington County, Pennylvania. Environ. Health Perspect. 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radtke C, Autenrieth DA, Lipsey T, Brazile WJ. 2017. Noise characterization of oil and gas operations. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg 14:659–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjit N, Diez-Roux AV, Shea S, et al. 2007. Psychosocial factors and inflammation in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arch. Intern. Med 167:174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen SG, Ogburn EL, McCormack M, et al. 2016. Association between unconventional natural gas development in the Marcellus Shale and asthma exacerbations. JAMA Intern. Med 176: 1334–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rundell KW, Hoffman JR, Caviston R, Bulbulian R, Hollenbach AM. 2007. Inhalation of ultrafine and fine particulate matter disrupts systemic vascular function. Inhalation Toxicol. 19:133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saberi P, Propert KJ, Powers M, Emmett E, Green-McKenzie J. 2014. Field survey of health perception and complaints of Pennsylvania residents in the Marcellus Shale region. Int J Environ Res Public Health 11:6517–6527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangaramoorthy T, Jamison AM, Boyle MD, Payne-Sturges DC, Sapkota A, Milton DK, et al. 2016. Place-based perceptions of the impacts of fracking along the Marcellus Shale. Social Science & Medicine 151:27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt F, Kolle K, Kreuder K, Schnorbus B, Wild P, Hechtner M, et al. 2015. Nighttime aircraft noise impairs endothelial function and increases blood pressure in patients with or at high risk for coronary artery disease. Clin. Res. Cardiol 104:23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opsal T and O’Connor S 2014. Energy crime, harm, and problematic state response in colorado: A case of the fox guarding the hen house? Crit Crim 22:561–577. [Google Scholar]

- Shin HH, Jones P, Brook R, Bard R, Oliver K, Williams R. 2015. Associations between personal exposures to VOCs and alterations in cardiovascular physiology: Detroit Exposure and Aerosol Research Study (DEARS). Atmos. Environ 104:246–255. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrenberger F, Cichelero F, Ascoli A, Fonseca F, Weiss G, Berwanger O, et al. 2008. Does psychosocial stress cause hypertension? A systematic review of observational studies. J. Hum. Hypertens 23:12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy S, Brink L, Larkin J, Sadovsky Y, Goldstein B, Pitt B, et al. 2015. Perinatal outcomes and unconventional natural gas operations in southwest Pennsylvania. PloS one 10:e0126425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Owen N, Kunz-Ebrecht S, Mohamed-Ali V. 2002. Inflammatory cytokines, socioeconomic status, and acute stress responsivity. Brain, Behav., Immun. 16:774784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoner L, Faulkner J, Lowe A, M. Lambrick D, M. Young J, Love R, et al. 2014. Should the augmentation index be normalized to heart rate? J. Atheroscler. Thromb 21:11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tustin AW, Hirsch AG, Rasmussen SG, Casey JA, Bandeen-Roche K, Schwartz BS. 2016. Associations between unconventional natural gas development and nasal and sinus, migraine headache, and fatigue symptoms in Pennsylvania. Environ. Health Perspect. 125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2009. Integrated science assessment (ISA) for particulate matter (final report, dec 2009). Washington, DC:U.S. Envirionmental Protection Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Urch B, Silverman F, Corey P, Brook JR, Lukic KZ, Rajagopalan S, et al. 2005. Acute blood pressure responses in healthy adults during controlled air pollution exposures. Environ. Health Perspect. 113:1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kempen E, Babisch W. 2012. The quantitative relationship between road traffic noise and hypertension: A meta-analysis. J. Hypertens 30:1075–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasunilashorn SM, Ngo L, Inouye SK, Libermann TA, Jones RN, Alsop DC, et al. 2015. Cytokines and postoperative delirium in older patients undergoing major elective surgery. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 70:1289–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve PJ, Jerrett M, Su J, Burnett RT, Chen H, Brook J, et al. 2013. A cohort study of intra-urban variations in volatile organic compounds and mortality, Toronto, Canada. Environ. Pollut 183:30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Känel R, Bellingrath S, Kudielka BM. 2008. Association between burnout and circulating levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in schoolteachers. J. Psychosom. Res 65:51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger B, Greiner LH, Walleigh L, Brown D. 2017. Health symptoms in residents living near shale gas activity: A retrospective record review from the Environmental Health Project. Preventive Medicine Reports 8:112–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017. ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APHA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 71: e13–e115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth KW, Marshall AK, Symanski E. 2017. Maternal residential proximity to unconventional gas development and perinatal outcomes among a diverse urban population in Texas. PloS one 12:e0180966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth KW, Marshall AK, Symanski E. 2018. Drilling and production activity related to unconventional gas development and severity of preterm birth. Environ. Health Perspect.126: 037001–037008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilber T 2012. Under the surface: Fracking, fortunes, and the fate of the marcellus shale:Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Willis MD, Juske AT, Halterman JS, and Hill EL. 2018. Unconventional natural gas development and pediartric asthma hospitalizations in Pennsylvania. Environ. Res 166: 402–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witter RZ, McKenzie L, Stinson KE, Scott K, Newman LS, Adgate J. 2013. The use of health impact assessment for a community undergoing natural gas development. Am J Public Health 103:1002–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Freeman NC, Dailey AB, Ilacqua VA, Kearney GD, Talbott EO. 2009. Association between exposure to alkylbenzenes and cardiovascular disease among National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) participants. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 15:385–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Qin B, Zhang X, Chen Y, Hou J. 2017. Association of central blood pressure and cardiovascular diseases in diabetic patients with hypertension. Medicine 96:e8286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Hao L, Xu L, Zhang Y, Qi L, Sun Y, et al. 2017. Diastolic augmentation index improves radial augmentation index in assessing arterial stiffness. Scientific Reports 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui T, Maegawa M, Tomita J, Miyatani Y, Yamada M, Uemura H, et al. 2007. Association of serum cytokine concentrations with psychological symptoms in midlife women. J. Reprod. Immunol 75:56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye D, Klein M, Chang HH, Sarnat JA, Mulholland JA, Edgerton ES, et al. 2017. Estimating acute cardiorespiratory effects of ambient volatile organic compounds. Epidemiology 28:197–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanobetti A, Canner MJ, Stone PH, Schwartz J, Sher D, Eagan-Bengston E, et al. 2004. Ambient pollution and blood pressure in cardiac rehabilitation patients. Circulation 110:2184–2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.