Abstract

Melanoma differentiation-associated gene 9 (MDA-9)/Syntenin is a multidomain PDZ protein and identified as a key oncogene in melanoma initially. This protein contains a unique tandem PDZ domain architecture (PDZ1 and PDZ2 spaced by a 4-amino acid linker), an N-terminal domain (NTD) that is structurally uncharacterized and a short C-terminal domain (CTD). The PDZ1 domain is regarded as the PDZ signaling domain while PDZ2 served as the PDZ superfamily domain. It has various cellular roles by regulating many of major signaling pathways in numerous cancertypes. Through the use of novel drug design methods, such as dimerization and unnatural amino acid substitution of inhibitors in our group, the protein may provide a valuable therapeutic target. The objective of this review is to provide a current perspective on the cancer-specific role of MDA-9/Syntenin in order to explore its potential for cancer drug discovery and cancer therapy.

Keywords: MDA-9/Syntenin, PDZ domain, Drug target, Dimeric peptide, Cancer

1. Introduction

PDZ (an acronym representing three proteins, postsynaptic density protein PSD95/SAP90, drosophila large tumor suppressor DLGA, and zonula occludens 1 ZO-1) domain-containing molecules are conserved sequence elements and well-described regions of 80–100 residues organized into six β strands (βA-βF) and two α-helices (αA-αB) that form compact and globular domains of 25-30 Å [1,2]. Generally, PDZ proteins control cells' diverse and central physiologic processes [3,4]. The adapter protein, melanoma differentiation-associated gene-9 (MDA-9)/Syntenin is a distinguishing member of PDZ family. It has been linked to numerous cellular functions in cancers, especially during the invasion and metastasis stage of cancer progression [4,5]. The expression level of MDA-9/Syntenin was found to be much higher in metastatic cancer cells as compared with non-metastatic cancer cells or normal cells [5,6]. MDA-9/Syntenin plays its cellular roles though interaction with an expanding list of regulatory proteins via specific conserved domains, which is important for cancer drug discovery [[5], [6], [7], [8]]. Our group and other groups have developed specific inhibitors of MDA-9/Syntenin resulting in reducing the progression of cancer cells [[8], [9], [10]]. These several lines of evidence suggest that MDA-9/Syntenin may provide a valuable therapeutic target for cancer therapy.

2. Discovery, Structure, and Regulation of MDA-9/Syntenin

In general, the growth control and differentiation of cancer cells are reversible and by appropriate treatment(s) it may reprogram cells to irreversibly growth arrest and terminally differentiate [[11], [12], [13], [14]]. Then differentiation therapy by switching on appropriate gene programs in cancer cells was developing [5,15,16]. In the context of human melanoma, Lin and colleagues performed this therapy approach by treatment with a combination of fibroblast interferon (IFN-β) and antileukemic agent mezerein (MEZ) resulted in an irreversible loss of proliferative capacity, changes in biochemical programs, alterations in surface antigen expression, modifications in cellular morphology, profound changes in gene expression, and induction of terminal differentiation [[17], [18], [19]]. To define the molecular basis of these wide-ranging changes as a function of induction of terminal differentiation, they utilized a subtraction hybridization screen between temporal libraries of normal cells and human melanoma cells resulted in the identification of melanoma differentiation associated genes, such as MDA-5 [20], MDA-6 [21], MDA-7 [22], and MDA-9 [17,18]. Interestingly, MDA-9 mRNA expression displayed distinct biphasic kinetic, indicating that modulation of MDA-9 expression is disassociated from growth suppression [17,18]. This is the first time to identify the gene MDA-9. Subsequently, Grootjans et al., used the yeast two-hybrid assay with the cytoplasmic domain of the transmembrane proteoglycan syndecans as baits to clone this gene, which they called syntenin [23].

The ~2.1-kb gene MDA-9/Syntenin is located on 8q12 with an open reading frame of 894 bp, encoding a 298 amino acid (aa) residues with a predicted molecular mass of ~33-kDa [17,18,23,24]. Cloning of mouse, rat, zebrafish, and Xenopus MDA-9/syntenin revealed that the gene is highly conserved with homologous across species [[25], [26], [27]]. As a distinguishing family member of PDZ proteins, MDA-9/Syntenin is composed of four domains: an NH2-terminal domain (NTD; aa 1–109) that shows no striking homology to any structural motifs, the first PDZ domain (PDZ1; aa 110–193), the second PDZ domain (PDZ2; aa 194–274), and a COOH-terminal domain (CTD; aa 275–298) (Fig. 1). Generally, PDZ domains bind the C-terminal peptide of the targeted multiprotein complexes at the plasma membrane as well as intracellular membranes [[28], [29], [30]]. The terminate peptide usually is binding with hydrophobic amino acid, such as valine or isoleucine located at P0 position, and with either threonine, or tyrosine located two residues from the C-terminus (P-2 position). Typically, PDZ domains are divided into three groups depending on their target peptide sequence: class I (-S/T-X-Φ), class II (−Φ-X-Φ), and class III (−D/E-X-Φ), where Φ is a hydrophobic residue, of which MDA-9/Syntenin has been shown to bind the three groups with a low-to-moderate affinity [[31], [32], [33]].

Fig. 1.

The domain organization of MDA-9/Syntenin. MDA-9/Syntenin is a 298 amino acid (aa) protein and composed of four domains. The PDZ1 domain is known as the signaling domain and PDZ2 as the superfamily domain, which are surrounded NH2-terminal and COOH-terminal domains. NTD (N-terminal domain), CTD (C-terminal domain).

In comparison to the majority of activity played by the two PDZ domains, the role of N- and C-terminal domains has been implicated only influencing the structure and stability of the full length protein [34,35]. Further study of the NTD region suggests that MDA-9/Syntenin exists in equilibrium between a closed and open state, possibly regulated by the phosphorylation of an auto-inhibitory domain in the NTD [36]. The NMR studies implicate that the CTD includes structural segments interact in tandem with PDZ domains.

Although PDZ1 and PDZ2 domains of MDA-9/Syntenin have only 26% amino acid identity, the crystal structure elucidated the two domains are structurally similar and arranged in a head-to-tail fashion [32]. During proto-oncogene protein c-Src binding, MDA-9/Syntenin's PDZ2 domain as a major or high-affinity c-Src binding domain and PDZ1 serves as a complementary or low affinity c-Src binding domain, whereby neither of the two PDZ domains is sufficient by itself [37]. This pattern is also observed in the binding process of MDA-9/Syntenin to a cytoplasmic domain syndecan [38,39]. In the two PDZ domains of MDA-9/Syntenin, the fragment equivalent to the signature GLGF loop, involved in the terminal carboxylate binding deviates from the paradigm by an insertion of a basic residue (Arg in PDZ1 and His in PDZ2) after the initial Gly [32]. Although rare, these insertions do not seem to perturb the binding between the target PDZ domains and the incoming peptides. A Lys or Arg located 4 or 5 residues typically prior to this loop assists in peptide binding. Except the similarities, there are some differences between the two domains. The notable difference is that the length of the PDZ2 βB-βC loop is much shorter than PDZ1, while PDZ1 contains an insertion of 4 residues. Furthermore, the peptide binding groove of PDZ1 is narrower as compared to PDZ2 or other PDZ domains. This is best illustrated the weak binding property of PDZ1 to the target protein or peptide. S0, S-1, and S-2 are three distinct binding pockets of PDZ2 domain and the interaction of the P-1 residue at the S-1 site is as necessary as the canonical interactions at the S0 and S-2 sites [32,40,41].

3. Expression and Molecular Mechanisms in Human Malignancies

Tumor cell invasion and metastasis are the major reasons of morbidity associated with human malignancies [[42], [43], [44]]. Since the firstly discovery of MDA-9/Syntenin in 1996, the role of this PDZ protein has been investigated in tumorigenesis by researchers. Compared with less invasive, less aggressive cancer cells, MDA-9/Syntenin has been found to be expressed at higher levels in more invasive and metastatic cell lines [10,45]. For example, it is identified MDA-9/Syntenin to be overexpressed in the invasive/metastatic breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-435 cells compared to the poorly invasive/non metastatic breast cancer cell line MCF-7 [46]. Researchers also found forced expression of MDA-9/Syntenin in nonmetastatic cancer cells resulted in cells migrating, and correlated with a more polarized distribution of F-actin and increased pseudopodia formation [23,47]. Furthermore, MDA-9/Syntenin gene silenced cancer cells will be accumulated in G1 phase along with enhance p21 and p27 expression [48]. These findings suggest MDA-9/Syntenin seem to be one of the important molecules mediating metastasis in cancers.

In melanomas, MDA-9/Syntenin was discovered first time, and the analysis of this protein was much more comprehensive than that in other epithelial cell carcinomas [8]. The expression of MDA-9/Syntenin was not shown in melanocytes of normal epidermis. However, distinct cytoplasmic and membrane MDA-9/Syntenin positive staining was observed in metastatic melanoma cells. Boukerche et al., demonstrated that the function of MDA/Syntenin is played by regulating FAK, p38-MAPK, c-Src, and NF-κB activity in melanoma progression [7,37]. The same research group also found MDA-9/Syntenin could promote melanoma cell migration and metastasis by mediating TF-FVIIa-Xa [49]. In recent studies, Dasgupta et al., demonstrated that both membranous and cytoplasmic co-localization of EGFR and MDA-9/Syntenin were detected in the urothelial cells. Moreover, knockdown of MDA-9/Syntenin inhibited cellular growth and invasion by inhibiting EGFR-signaling and key epithelial mesenchymal transition EMT-associated molecules [50]. The raf kinase inhibitor (RKIP) could reduce the ability of MDA-9/Syntenin by mediating FAK and c-Src activity [9]. In further study, they also demonstrated MDA-9/Syntenin could promote the melanoma cells migration and invasion by mediating with IGFBP2, HIF-1a, VEGF-A, and VEGFR [51]. In uveal melanoma, another group reported knockdown of the gene MDA-9/Syntenin resulted in diminishing angiogenesis along with reduced expression of FAK, AKT, and c-Src [52].

Breast cancer is an aggressive malignancy that frequently occurs among women worldwide [53]. A couple of recent works in breast cancer showed that MDA-9/Syntenin overexpression correlated positively with tumor size, lymph node metastasis, and tumor recurrence [54]. In one study, Yang et al., demonstrated MDA-9/Syntenin activates the Integrin β1 and ERK1/2 signaling leading to the breast cancer cells proliferation [55]. In addition to being a marker of metastasis breast cancer, MDA-9/Syntenin overexpression was also evident particularly in estrogen receptor (ER) negative breast tumor tissues. It was further shown MDA-9/Syntenin promoted progression of the ER negative breast cancer cells through the regulation of p21 and p27 expression [54]. Menezes et al., demonstrated that MDA-9/Syntenin modulated small GTPases RhoA and Cdc42 via transforming growth factor β1 to enhance epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) in breast cancer [56]. Moreover, MDA-9/Syntenin interacting with its partner eIF5A might regulate p53 by balancing the regulation of eIF5A signaling for p53 induced apoptosis [57].

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common primary central nervous system tumor defined as a grade IV astrocytoma by WHO in adults [58]. Recent studies showed MDA-9/Syntenin enhanced the proliferation of the human glioma cells through regulating FAK-JNK and FAK-AKT signaling [59]. Overexpression of MDA-9/Syntenin promoted migration and invasion of human glioma cells by activating c-Src, p38-MAPK, NF-kB, SPRR1B, and MMP2 signaling pathway [6,60]. MDA-9/Syntenin also promoted glioma stem cells (GSCs) phenotypes and survival through regulation of NOTCH1, C-Myc, STAT3, and Nanog in GSCs [61]. MDA-9/Syntenin silencing induces autophagic death in GSCs. This process is mediated through phosphorylation of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 accompanied with suppression of high levels of autophagic proteins (ATG5, LAMP1, and LC3B) through EGFR signaling [62,63]. Moreover, MDA-9/Syntenin regulates protective autophagy in glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs) through two cascades: first, the complex composed of MDA-9/Syntenin and focal adhesion kinase (FAK) promotes phosphorylated Bcl-2 via PKCα, and second, the complex of MDA-9/Syntenin and FAK activates EGFR induces autophagy-related molecules such as Atg5, LC-3, and Lamp1 [62].

Similar to other studies, MDA-9/Syntenin also promotes invasion and migration of small cell lung cancer (SCLC). SCLC is another particularly aggressive cancer, in which high expression of MDA-9/Syntenin is associated with more advanced and extensive disease at diagnosis [64]. Kim et al., have shown that an invasion promoting role of MDA-9/Syntenin through upregulation of MT1-MMP and MMP2 in human SCLC cells [64,65]. In another study, MDA-9/Syntenin was shown to regulate cellular differentiation, and angiogenesis in SCLC via the activation of ras, rho and PI3K/MAPK signaling [66]. Yang et al., provided evidence that MDA-9/Syntenin acts as a pivotal adaptor of Slug (a member of the Snail family) and it transcriptionally enhances Slug-mediated EMT to promote cancer invasion and metastasis in non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLCs) [67].

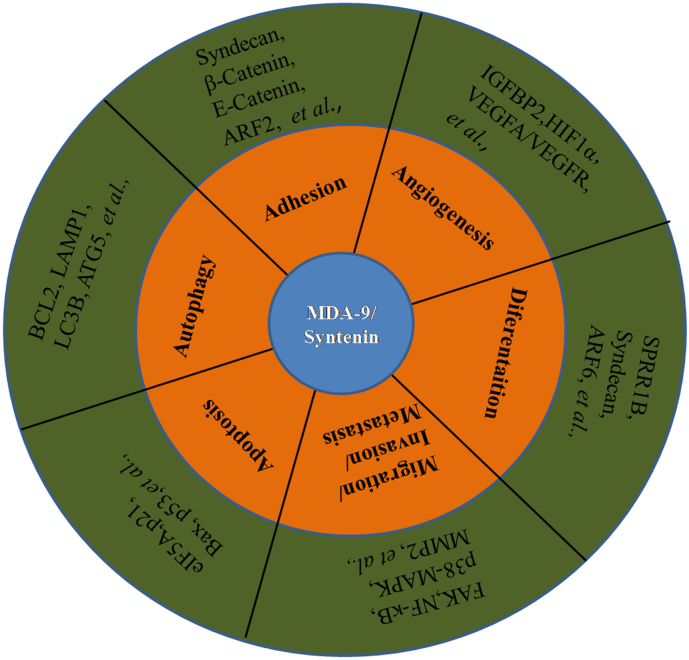

Furthermore, MDA-9/Syntenin upregulats TGFβ signaling by regulating caveolin-1-mediated internalization of TβRI in cancer cells. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that MDA-9/Syntenin acts as an important positive regulator of cancer progression by numerous signaling molecules (Fig. 2 and Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram for MDA-9/Syntenin influenced cancer progression and mediated key molecular partners.

Table 1.

MDA-9/Syntenin mediated signaling pathways in different cancers.

| Cancer name | Signaling pathway |

|---|---|

| Melanomas | NF-κB, c-Src/FAK, p38-MAPK, TF-FVIIa, EGFR, VEGF-A/VEGFR-2, and IGFBP2-HIF1a, et al., |

| Breast cancer | EGFR, Integrin β1, ERK1/2, estrogen receptor(ER), and CDC42/Rho GTPases, et al., |

| Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) | FAK-JNK, FAK-AKT, c-Src, p38-MAPK, NF-κB, SPRR1B, MMP2, NOTCH1, C-Myc, STAT3, and Nanog, et al., |

| Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) | MT1-MMP, MMP2, ras, rho, and PI3K/MAPK, et al., |

| Others | TGFβ, FAK, AKT, and c-Src, et al., |

4. Pharmacological Inhibitors of MDA-9/Syntenin

Multiple studies demonstrate the key role of MDA-9/Syntenin in metastasis of various cancer cells. The expression level of MDA-9/Syntenin was found to be much higher in metastatic cell lines as compared with non-metastatic cancer-cell lines [46]. Also, upregulation of MDA-9/Syntenin was correlated with migration of nonmetastatic cancer cells [68], and genetic knockdown of MDA-9/Syntenin inhibited cell migration and invasion [6,66]. There is no doubt that MDA-9/Syntenin is a valuable target for cancer therapy. It was therefore postulated that inhibiting the function of MDA-9/Syntenin, in particular the ligand-binding property of the tandem PDZ domain, may be an effective way of preventing metastatic cancer spreading [69].

Targeting of pharmaceuticals to MDA-9/Syntenin PDZ domains, however, has not been widely successfully developed. Because natural PDZ peptides binding interactions are often weak and promiscuous, so it is very challenging to develop pharmaceutical MDA-9/Syntenin PDZ inhibitors. In recent years, approaches that enable probing of large libraries of potential molecules are developed, such as mRNA display [70] and fragment-based drug discovery coupled with NMR analysis [71,72]. These approaches may aid in finding a way to inhibit difficult structures like the PDZ domains. Kegelman and co-workers developed small-molecule inhibitors of MDA-9/Syntenin by using innovative fragment-based drug design and NMR approaches. They found that the inhibitors reduced invasion gains in glioblastoma multiforme cells following radiation [73]. Therefore, MDA-9/Syntenin-targeted inhibition produced a similar effect as genetic knockdown. Fisher and co-workers demonstrated the efficacy of supplementing radiotherapy by targeting, either genetically (small hairpin RNA for MDA-9/Syntenin) or pharmacologically (PDZ1i), MDA-9/Syntenin in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). Importantly, they used the useful strategies of fragment-based lead design, or fragment based drug design (FBDD) for developing small-molecule inhibitor of MDA-9/Syntenin PDZ1 domain. Briefly, NMR-based screening of an in-house assembled fragment library of about 5000 compounds using [15N, 1H] heteronuclear single-quantum coherence spectroscopy (HSQC) spectra with a 15N-labeled PDZ1/2 tandem domain from MDA-9/Syntenin identified two hit compounds. Chemical shift mapping studies demonstrated that these two compounds interacted mainly with the PDZ1 domain, whereas no viable fragment hits were found binding to the PDZ2 domain. And then, they synthesized a bidentate molecule 113B7 (termed PDZ1i) by combining molecular docking studies with structure–activity relationship studies. The data shows the molecule PDZ1i selectively binds to the PDZ1 domain, but not the PDZ2 domain. These initial studies reveal that PDZ1i effectively inhibits invasion in GBM cells and MDA-9/Syntenin–induced invasion following MDA-9/Syntenin overexpression in HEK-293 cells. By counteracting gains in Src, FAK, EPH receptor A2 (EphA2), and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling, MDA-9/Syntenin inhibition can reduce radiation-induced invasion as well as radiosensitize GBM cells, ideal properties to complement radiation treatment [8]. This study highlights the distinctive effect of MDA-9/Syntenin PDZ1 inhibitor in aggressive GBM cells in vitro, including profound anti-invasive effects, good stability without over toxicity in vivo, a potential ability to pass the blood–brain barrier, and the capacity to both radiosensitize and block invasion gains of radiation.

Previously, we utilized proximal reactivity to develop reactive peptides against a PDZ protein PDZ-RGS3 inside cells leading to inhibit human neuroblastoma cells migrating [74,75]. Despite its success, this strategy can not be applied to MDA-9/Syntenin as it does not have a reactive residue (for example cysteine) at the peptide-binding site. On the other hand, Strømgaard and coworkers have developed a dimeric peptide inhibitor that binds to the tandem PDZ domain of PSD >1000 fold tighter than the natural PDZ epitope [76]. Therefore, we reason that a peptide dimer containing two binding epitopes appropriately spaced by a linker will bind the MDA-9/Syntenin tandem PDZ domain (through simultaneous binding to both PDZ domains) with much higher affinity.

In a recent work, we developed the first dimeic peptide inhibitor of MDA-9/Syntenin PDZ domain based on natural epitopes. Two strategies are employed to derive high-affinity blockers from the low-affinity natural binding peptides: first, dimerization of the C termini of natural MDA-9/Syntenin-binding peptides confers dimer peptides with much higher affinity than the monomers; second, unnatural amino acid substitution at P-1 and P-2 positions of the PDZ-binding sequence increases the binding affinity [10]. Briefly, first, four peptides derived from the natural binding proteins of MDA-9/Syntenin were chosen as the parental MDA-9/Syntenin blockers: RVAFFEEL (an epitope from Merlin, named p1) [32], TNEFYA (an epitope from syndecan, named p2) [32], DKEYYV (an epitope from neurexin, named p3) [76], and LEDSVF (an epitopefrom interleukin-5 receptor a, named p4) [32]. We next synthesized dimeric peptides by crosslinking peptide N termini through a linker PEG3 by cysteine maleimide bioconjugation reaction. The PEG3 linker will allow the dimeric peptide to bind to both the PDZ1 and PDZ2 domains.

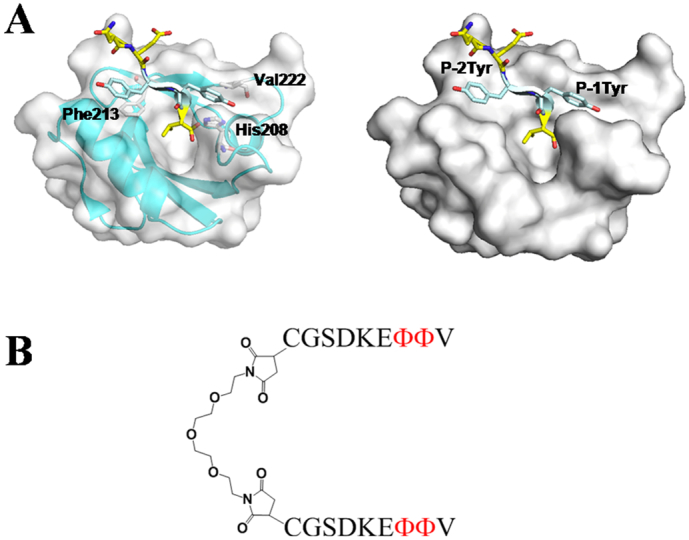

According to the crystal structure of the protein complexes between MDA-9/Syntenin tandem PDZ domain and its natural binding epitopes, MDA-9/Syntenin mainly recognizes the three C-terminal amino acids in the target ligand (P0, P-1, and P-2, P0 refers to the C-terminal residue of the peptide and P-n refers to the nth amino acid upstream of peptide) and the residues upstream are not involved in the binding (Fig. 3A) [77]. Residue at the P0 position (Val) dominates the recognition of PDZ and ligand, and hydrophobic interaction between the side chain of tyrosine and the domain pocket is the main contributor to the binding interaction (Fig. 3A). We substituted the tyrosine at P-1 and P-2 positions of peptide p3 (DKEYYV) by tryptophan, phenylalanine, and an unnatural amino acid naphthylalanine (Φ) to increase the hydrophobicity at this position. The optimized dimeric peptide 13–13 (Fig. 3B) showed the strongest binding affinity with a KD value of 0.21 μM to syntenin tandem PDZ domain and 160 times higher than the original peptide p3 (the KD value of p3 for PDZ1 81 ± 7 μM, PDZ2 33 ± 2 μM). Individual PDZ domains alone however showed significantly lower affinity (1.2 μM for PDZ1 and 0.52 μM for PDZ2) compared to the tandem domain (0.21 μM). This suggests that both PDZ1 and PDZ2 in the tandem domain protein are involved in the binding to the 13–13 peptidedimer [77]. The following studies demonstrated MDA-9/Syntenin-targeted dimeric inhibitor selectively inhibits cell migration in MDA-9/Syntenin overexpressing cells but not in a control cell line with lower expression. Our work show cases an effective strategy to derive high-affinity blocker of multidomain adaptor proteins, which resulted in a MDA-9/Syntenin-targeted antagonist with potential pharmaceutical values for the treatment of MDA-9/Syntenin overexpressing cancers.

Fig. 3.

Syntenin and its peptide binding properties. (A) The structure of syntenin PDZ2 bound with the peptide NEYYV (PDB ID: 1w9o). Both tyrosine residues at P-1 and P-2 reside at hydrophobic clefts of the binding site, and interact with His 208, Val 222, and Phe 213, respectively [10]. (B) The structure of dimeric peptides based on peptide p3(DKEYYV). Substituted the tyrosine at P-1 and P-2 positions of peptide p3 (DKEYYV) by tryptophan, phenylalanine and an unnatural amino acid naphthylalanine (Φ) to increase the hydrophobicity at this position.

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

In conclusion, since MDA-9/Syntenin's discovery in a subtraction hybridization screen for genes involved in human melanoma differentiation, it displays an impressive diversity of interacting partners, indicating it serves as a significant role in human tumorigenesis. Multiple studies demonstrated MDA-9/Syntenin's activity in driving metastatic progression of various human malignancies via FAK, c-Src, p38-MAPK, AKT, NF-κB, IGFBP2, SPRR1B, and EGFR signaling (Table 1). Overall, MDA-9/Syntenin provides a direct target for therapy of aggressive cancers, and defined small-molecule inhibitors such as dimeric peptide hold promise to advance cancer targeted therapy. The further investigations would help identify novel functions and partners of MDA-9/Syntenin, thereby providing a better perspective in developing of therapeutic interventions based on targeted disruption of MDA-9/Syntenin. As we all know that there is unlikely to be a single protein target that can completely eliminate aggressive tumors. Although inhibiting MDA-9/Syntenin could reduce the proliferation rate of some cancer types, the level to which it slows growth is not nearly as dramatic as true cytotoxic therapies. Therefore, selectively inhibition of MDA-9/Syntenin could serve as an ideal complement to many conventional therapy strategies such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy. In these contexts, inhibitors of MDA-9/Syntenin, both direct and those that block its interaction with partner proteins, combined with conventional therapies may provide a novel approach for effectively treating and potentially preventing both primary tumors and metastases.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Sponsored by Shanghai Pujiang Program (China, 18PJ1409400), Scientific Research Foundation of Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (China, 20174Y0218), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (China, 22120170210 and 1515219050), Program for Young Excellent Talents in Tongji University (China, 1515219033), Shanghai Municipal Medical and Health Discipline Construction Projects (China, 2017ZZ02015), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81703394).

Contributor Information

Kai Wang, Email: kaiwangcn@yahoo.com.

Xiaoping Wan, Email: wanxiaoping@tongji.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Elkins J.M., Papagrigoriou E., Berridge G., Yang X., Phillips C., Gileadi C. Structure of PICK1 and other PDZ domains obtained with the help of self-binding C-terminal extensions. Protein Sci. 2007;16:683–694. doi: 10.1110/ps.062657507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarkar D., Boukerche H., Su Z.Z., Fisher P.B. Mda-9/Syntenin: more than just a simple adapter protein when it comes to cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3087–3093. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friand V., David G., Zimmermann P. Syntenin and syndecan in the biogenesis of exosomes. Biol Cell. 2015;107:331–341. doi: 10.1111/boc.201500010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang Y., Hong Q., Shi P., Liu Z., Luo J., Shao Z. Elevated expression of syntenin in breast cancer is correlated with lymph node metastasis and poor patient survival. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:R50. doi: 10.1186/bcr3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarkar D., Boukerche H., Su Z.Z., Fisher P.B. Mda-9/syntenin: recent insights into a novel cell signaling and metastasis-associated gene. Pharmacol Ther. 2004;104:101–115. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kegelman T.P., Das S.K., Hu B., Bacolod M.D., Fuller C.E., Menezes M.E. MDA-9/syntenin is a key regulator of glioma pathogenesis. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16:50–61. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boukerche H., Su Z., Prvot C. Mda-9/syntenin promotes metastasis in human melanoma cells by activating c-src. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15914–15919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808171105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kegelman T.P., Wu B., Das S.K. Inhibition of radiation-induced glioblastoma invasion by genetic and pharmacological targeting of MDA-9/Syntenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:370–375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616100114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Das S.K., Bhutia S.K., Sochi U.K., Ahab B., Su Z.Z., Boukerche H. Raf kinase inhibitor RKIP inhibits MDA-9/syntenin-mediated metastasis in melanoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:6217–6226. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J., Qu J., Zhou W., Huang Y., Jia L., Huang X. Syntenin-targeted peptide blocker inhibits progression of cancer cells. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;154:354–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emon B., Bauer J., Jain Y., Jung B., Saif T. Biophysics of tumor microenvironment and cancer metastasis. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2018;16:279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y., Liu X., Li Y., Quan C., Zheng L., Huang K. Lung cancer therapy targeting histone methylation: opportunities and challenges. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2018;16:211–223. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernhardt M., Novak D., Assenov Y., Orouji E., Knappe N., Weina K. Melanoma-derived iPCCs show differential tumorigenicity and therapy response. Stem Cell Rep. 2017;8:1379–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanjee U., Grüring C., Chaand M., Lin K.M., Egan E., Manzo J. CRISPR/Cas9 knockouts reveal genetic interaction between strain-transcendent erythrocyte determinants of Plasmodium falciparum invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E9356–E9365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1711310114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott R.E. Differentiation, differentiation/gene therapy and cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 1997;73:51–65. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(96)00120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waxman S. Differentiation therapy in acute myelogenous leukemia (non-APL) Leukemia. 2000;14:491–496. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin J.J., Jiang H., Fisher P.B. Characterization of a novel melanoma differentiation-associated gene, mda-9, that is down-regulated during terminal cell differentiation. Mol Cell Differ. 1996;4:317–333. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin J.J., Jiang H., Fisher P.B. Melanoma differentiation associated gene-9, mda-9, is a human gamma interferon responsive gene. Gene. 1998;207:105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00562-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pestka S., Krause C.D., Sarkar D., Walter M.R., Shi Y., Fisher P.B. Interleukin-10 and related cytokines and receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:929–979. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang D.C., Gopalkrishnan R.V., Lin L., Randolph A., Valerie K., Pestka S. Expression analysis and genomic characterization of human melanoma differentiation associated gene-5, mda-5: a novel type I interferon-responsive apoptosis-inducing gene. Oncogene. 2004;23:1789–1800. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang H., Lin J., Su Z.Z., Herlyn M., Kerbel R.S., Weissman B.E. The melanoma differentiation-associated gene mda-6, which encodes the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21, is differentially expressed during growth, differentiation and progression in human melanoma cells. Oncogene. 1995;10:1855–1864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang H., Lin J.J., Su Z.Z., Goldstein N.I., Fisher P.B. Subtraction hybridization identifies a novel melanoma differentiation associated gene, mda-7, modulated during human melanoma differentiation, growth and progression. Oncogene. 1995;11:247786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grootjans J.J., Zimmermann P., Reekmans G., Smets A., Degeest G., Dürr J. Syntenin, a PDZ protein that binds syndecan cytoplasmic domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13683–13688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Das S.K., Pradhan A.K., Bhoopathi P., Talukdar S., Shen X.N., Sarkar D. The MDA-9/Syntenin/IGF1R/STAT3 axis directs prostate cancer invasion. Cancer Res. 2018;78:2852–2863. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zimmermann P., Tomatis D., Rosas M. Characterization of syntenin, a syndecan-binding PDZ protein, as a component of cell adhesion sites and microfilaments. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:339–350. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.2.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luyten A., Mortier E., Van Campenhout C. The postsynaptic density 95/disc-large/zona occludens protein syntenin directly interacts with frizzled 7 and supports noncanonical wnt signaling. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:1594–1604. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambaerts K., Van Dyck S., Mortier E. Syntenin, a syndecan adaptor and an Arf6 phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate effector, is essential for epiboly and gastrulation cell movements in zebrafish. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1129–1140. doi: 10.1242/jcs.089987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koroll M., Rathjen F.G., Volkmer H. The neural cell recognition molecule neurofascin interacts with syntenin-1 but not with syntenin-2, both of which reveal self-associating activity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10646–10654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010647200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Das S., Bhutia S., Kegelman T. MDA-9/syntenin: a positive gatekeeper of melanoma metastasis. Front Biosci. 2012;17:1–15. doi: 10.2741/3911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baietti M., Zhang Z., Mortier E. Syndecan-syntenin-ALIX regulates the biogenesis of exosomes. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:677–685. doi: 10.1038/ncb2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hung A.Y., Sheng M. PDZ domains: structural modules for protein complex assembly. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5699–5702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang B., Cooper D., Jelen F. PDZ tandem of human syntenin: crystal structure and functional properties. Structure. 2003;11:459–468. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grembecka J., Cierpicki T., Devedjiev Y. The binding of the PDZ tandem of syntenin to target proteins. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3674–3682. doi: 10.1021/bi052225y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Juan-Sanz J., Zafra F., Lopez-Corcuera B. Endocytosis of the neuronal glycine transporter GLYT2: role of membrane rafts and protein kinase C-dependent ubiquitination. Traffic. 2011;12:1850–1867. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez-Moczygemba M., Huston D.P., Lei J.T. JAK kinases control IL-5 receptor ubiquitination, degradation, and internalization. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:1137–1148. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0706465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wawrzyniak A.M., Vermeiren E., Zimmermann P. Extensions of PSD-95/discs large/ZO-1 (PDZ) domains influence lipid binding and membrane targeting of syntenin-1. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:1445–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boukerche H., Aissaoui H., Prvost C. Src kinase activation is mandatory for MDA-9/syntenin-mediated activation of nuclear factor-kappaB. Oncogene. 2010;29:3054–3066. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grootjans J.J., Reekmans G., Ceulemans H. Syntenin-syndecan binding requires syndecan-synteny and the co-operation of both PDZ domains of syntenin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19933–19941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002459200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hwangbo C., Kim J., Lee J. Activation of the integrin effector kinase focal adhesion kinase in cancer cells is regulated by crosstalk between protein kinase calpha and the PDZ adapter protein mda-9/syntenin. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1645–1655. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morais Cabral J.H., Petosa C., Sutcliffe M.J., Raza S., Byron O., Poy F. Crystal structure of a PDZ domain. Nature. 1996;382:649–652. doi: 10.1038/382649a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hung A.Y., Sheng M. PDZ domains: structural modules for protein complex assembly. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5699–5702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma X., Huang J., Tian Y., Chen Y., Yang Y., Zhang X. Myc suppresses tumor invasion and cell migration by inhibiting JNK signaling. Oncogene. 2017;36:3159–3167. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koshiba H. Spontaneous ovarian heterotopic pregnancy mimicking ovarian malignant tumor: case report. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2017;44:946–948. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu Y., Nie Y., Feng Q., Qu J., Wang R., Bian L. Targeted covalent inhibition of Grb2-Sos1 interaction through proximity-induced conjugation in breast cancer cells. Mol Pharm. 2017;14:1548–1557. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boukerche H. mda-9/Syntenin: a positive regulator of melanoma metastasis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10901–10911. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koo T.H., Lee J.J., Kim E.M., Kim K.W., Kim H.D., Lee J.H. Syntenin is overexpressed and promotes cell migration in metastatic human breast and gastric cancer cell lines. Oncogene. 2002;21:4080–4088. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hirbec H., Martin S., Henley J.M. Syntenin is involved in the developmental regulation of neuronal membrane architecture. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:737–746. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qian X.L., Li Y.Q., Yu B., Gu F., Liu F.F., Li W.D. Syndecan binding protein (SDCBP) is overexpressed in estrogen receptor negative breast cancers, and is a potential promoter for tumor proliferation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aissaoui H., Prevost C., Boucharaba A., Sanhadji K., Bordet J.C., Negrier C. MDA-9/syntenin is essential for factor VIIa-induced signaling, migration, metastasis in melanoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:3333–3348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.606913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 50.Dasgupta S., Menezes M.E., Das S.K., Emdad L., Janjic A., Bhatia S. Novel role of MDA-9/syntenin in regulating urothelial cell proliferation by modulating EGFR signaling. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:4621–4633. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Das S.K., Bhutia S.K., Azab B., Kegelman T.P., Peachy L., Santhekadur P.K. MDA-9/syntenin and IGFBP-2 promote angiogenesis in human melanoma. Cancer Res. 2013;73:844–854. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gangemi R., Mirisola V., Barisione G., Fabbi M., Brizzolara A., Lanza F. MDA-9/syntenin is expressed in uveal melanoma and correlates with metastatic progression. PLoS One. 2012;7:29989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eccles S.A., Aboagye E.O., Ali S. Critical research gaps and translational priorities for the successful prevention and treatment of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:R92. doi: 10.1186/bcr3493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qian X., Li Y., Yu B. Syndecan binding protein (SDCBP) is overexpressed in estrogen receptor negative breast cancers, and is a potential promoter for tumor proliferation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang Y., Hong Q., Shi P., Liu Z., Luo J., Shao Z. Elevated expression of syntenin in breast cancer is correlated with lymph node metastasis and poor patient survival. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:R50. doi: 10.1186/bcr3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Menezes M.E., Shen X.N., Das S.K., Emdad L., Sarkar D., Fisher P.B. MDA-9/Syntenin (SDCBP) modulates small GTPases RhoA and Cdc42 via transforming growth factor β1 to enhance epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:80175–80189. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li A.L., Li H.Y., Jin B.F., Ye Q.N., Zhou T., Yu X.D. A novel eIF5A complex functions as a regulator of p53 and p53-dependent apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49251–49258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Michael J.S., Lee B.S., Zhang M., Yu J.S. Nanotechnology for treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. J Transl Int Med. 2018;6:128–133. doi: 10.2478/jtim-2018-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhong D., Ran J.H., Tang W.Y., Zhang X.D., Tan Y., Chen G.J. MDA-9/syntenin promotes human brain glioma migration through focal adhesion kinase (FAK)-JNK and FAK-AKT signaling. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:2897–2901. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.6.2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oyesanya R.A., Bhatia S., Menezes M.E., Dumur C.I., Singh K.P., Bae S. MDA-9/Syntenin regulates differentiation and angiogenesis programs in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncoscience. 2014;1:725–737. doi: 10.18632/oncoscience.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Talukdar S., Das S.K., Pradhan A.K., Emdad L., Shen X.N., Windle J.J. Novel function of MDA-9/Syntenin (SDCBP) as a regulator of survival and stemness in glioma stem cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:54102–54119. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Talukdar S., Pradhan A.K., Bhoopathi P., Shen X.N., August L.A., Windle J.J. Regulation of protective autophagy in anoikis-resistant glioma stem cells by SDCBP/MDA-9/Syntenin. Autophagy. 2018;14:1845–1846. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2018.1502564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Talukdar S., Pradhan A.K., Bhoopathi P., Shen X.N., August L.A., Windle J.J. MDA-9/Syntenin regulates protective autophagy in anoikis-resistant glioma stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:5768–5773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1721650115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim W.Y., Jang J.Y., Jeon Y.K. Syntenin increases the invasiveness of small cell lung cancer cells by activating p38, AKT, focal adhesion kinase and SP1. Exp Mol Med. 2014;46:e90. doi: 10.1038/emm.2014.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim J.H., Lee H.K., Takamiya K., Huganir R.L. The role of synaptic GTPase-activating protein in neuronal development and synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1119–1124. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01119.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meerschaert K., Bruyneel E., De Wever O., Vanloo B., Boucherie C., Bracke M. The tandem PDZ domains of syntenin promote cell invasion. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:1790–1804. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang L.K., Pan S.H., Chang Y.L., Hung P.F., Kao S.H., Wang W.L. MDA-9/Syntenin-Slug transcriptional complex promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition and invasion/metastasis in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:386–401. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hirbec H., Martin S., Henley J.M. Syntenin is involved in the developmental regulation of neuronal membrane architecture. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:737–746. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Beekman J.M., Coffer P.J. The ins and outs of syntenin, a multifunctional intracellular adaptor protein. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:1349–1355. doi: 10.1242/jcs.026401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ma Z., Hartman M.C. In vitro selection of unnatural cyclic peptide libraries via mRNA display. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;805:367–390. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-379-0_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rega M.F., Wu B., Wei J. SAR by interligand nuclear overhauser effects (ILOEs) based discovery of acylsulfonamide compounds active against bcl-x(L) and mcl-1. J Med Chem. 2011;54:6000–6013. doi: 10.1021/jm200826s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hedvat M., Emdad L., Das S.K. Selected approaches for rational drug design and high throughput screening to identify anti-cancer molecules. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2012;12:1143–1155. doi: 10.2174/187152012803529709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kegelman T.P. In vivo modeling of malignant glioma: the road to effective therapy. Adv Cancer Res. 2014;121:261–330. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800249-0.00007-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yu Y., Liu M., Ng T.T., Huang F., Nie Y., Wang R. PDZ-reactive peptide activates Ephrin-B reverse signaling and inhibits neuronal chemotaxis. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:149–158. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yu Y., Xia J. Affinity-guided protein conjugation: the trilogy of covalent protein labeling, assembly and inhibition. Sci Chi Chem. 2016;59:853–861. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Eildal J.N., Bach A., Dogan J., Ye F., Zhang M., Jemth P. Rigidified clicked dimeric ligands for studying the dynamics of the PDZ1-2 supramodule of PSD-95. Chembiochem. 2015;16:64–69. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Grembecka J., Cierpicki T., Devedjiev Y., Derewenda U., Kang B.S., Bushweller J.H. The binding of the PDZ tandem of syntenin to target proteins. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3674–3683. doi: 10.1021/bi052225y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]