Abstract

High levels of proinflammatory cytokines have been associated with a loss of tissue function in ocular autoimmune diseases, but the basis for this relationship remains poorly understood. Here we investigate a new role for tumor necrosis factor α in promoting N-glycan–processing deficiency at the surface of the eye through inhibition of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase expression in the Golgi. Using mass spectrometry, complex-type biantennary oligosaccharides were identified as major N-glycan structures in differentiated human corneal epithelial cells. Remarkably, significant differences were detected between the efficacies of cytokines in regulating the expression of glycogenes involved in the biosynthesis of N-glycans. Tumor necrosis factor α but not IL-1β had a profound effect in suppressing the expression of enzymes involved in the Golgi branching pathway, including N-acetylglucosaminyltransferases 1 and 2, which are required for the formation of biantennary structures. This decrease in gene expression was correlated with a reduction in enzymatic activity and impaired N-glycan branching. Moreover, patients with ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid were characterized by marginal N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase expression and decreased N-glycan branching in the conjunctiva. Together, these data indicate that proinflammatory cytokines differentially influence the expression of N-glycan–processing enzymes in the Golgi and set the stage for future studies to explore the pathophysiology of ocular autoimmune diseases.

Glycosylation is one of the most frequent and ubiquitous post-translational modifications in living organisms, taking place in more than half of all proteins.1 It is orchestrated by the action of multiple genes encoding for glycosyltransferases and enzymes involved in the processing and turnover of glycans, such as glycosidases and sulfotransferases. Monosaccharides are the basic structural units of glycans and are unique in that they can be attached to each other in many more ways than amino acids or nucleotides, leading to enormous structural diversity. Recent estimates have indicated that there are possibly over 7000 glycan determinants in the human glycome, with a myriad of biological functions relevant to the development and physiology of different organs and tissues.2

N-glycosylation constitutes a major form of glycosylation in eukaryotic cells. It starts with the transfer of a lipid-linked oligosaccharide to asparagine residues on nascent polypeptides during their translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum.3 Subsequent processing of this precursor ensures the efficient folding of newly synthesized glycoproteins before reaching the Golgi apparatus, where much of the diversity of glycosylation originates.4 Localization studies have shown that glycan-processing enzymes in the Golgi have a nonuniform distribution along the cis–trans axis.5 The trimming and maturation of N-glycans start in the cis-Golgi by catalytic removal of terminal mannose residues. Then, a family of mannoside N-acetylglucosaminyltransferases (MGATs) in the medial Golgi sequentially catalyzes the conversion of oligomannose structures into hybrid- and complex-type N-glycans by adding N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) residues. This process appears to be essential for survival, since defects in the MGAT1 gene, which encodes for N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 1, result in embryonic lethality.6, 7 Further processing of branched structures in the trans-Golgi is crucial for the extracellular functions of N-glycans and for the formation of galectin–glycoprotein lattices, which affect a multitude of cell-adhesion and -signaling processes.8, 9

Maintenance of normal immune system homeostasis is indispensable in the prevention of dysfunction in biological systems. Autoimmune diseases are relatively frequent events that occur when the immune system turns its antimicrobial defenses against normal components of the body.10 A diverse spectrum of autoimmune disorders has been described at the surface of eye. These can be ocular specific (eg, Mooren ulcerative keratitis), systemic (eg, Sjögren syndrome, mucous membrane pemphigoid), or secondary to other autoimmune diseases (eg, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus).11 The breakdown of self-tolerance under these conditions leads to the excessive production of cytokines that initiate and perpetuate the inflammatory cascade. Among the different cytokines found to be aberrantly expressed in autoimmune diseases, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α has been long recognized to be of particular importance in promoting tissue destruction.12 In the eye, and under disease conditions, TNFα is produced by a large number of stromal infiltrating cells.13 The underlying pathologic mechanisms of TNFα are varied and multiple, and include the ability to impair the differentiation, proliferation, and viability of specific cellular targets.14 How TNFα affects the actual biology of the affected tissues remains nonetheless largely unknown. Here, we identify a novel function of TNFα in promoting N-glycan–processing deficiency at the surface of the eye through the inhibition of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase expression in the Golgi. Moreover, we report on the finding that the alteration of N-glycan biosynthetic pathways during inflammatory stress is cytokine dependent, supporting a specific role for individual proinflammatory cytokines in the pathophysiology of tissue damage in ocular autoimmune disease.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Multilayered cultures of telomerase-immortalized human corneal epithelial cells were grown as previously reported.15 Briefly, cells were plated at a seeding density of 5 × 104 cells/cm2 and maintained in keratinocyte serum–free medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockville, MD) until confluence. Thereafter, cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F12 supplemented with 10% calf serum and 10 ng/mL epidermal growth factor for 7 days to promote stratification and differentiation. Where indicated, cells were serum-starved for 1 hour and incubated with 10 or 40 ng/mL TNFα (PeproTech, Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ) or 10 ng/mL IL-1β (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in serum-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F12. Media along with fresh cytokines were replaced every 24 hours.

Human Specimens

Conjunctival epithelium was collected by impression cytology from 17 eyes of 10 patients with ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid stage II at Fondazione GB Bietti (Rome, Italy). The mean age of the patients was 64.9 ± 9.3 years (range, 44 to 79 years). Ten specimens from 10 age-matched healthy subjects were used as a control group. The mean age of the control group was 60.3 ± 2.6 years (range, 58 to 64 years). Exclusion criteria for the control group included a history of ocular disease or eye surgery and contact lens wear. Informed consent was obtained from each recruited patient. The study protocol conformed to the ethics guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the IRB of Campus Bio Medico University of Rome (Rome, Italy; IRB number 07/06.PARComEtCBM). Human conjunctival biopsy samples, stored in paraffin, from three healthy subjects were obtained as archived material from a previously published study.16 Conjunctival tissue sections from three patients with ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid were obtained from Campus Bio Medico University of Rome.

Enzymatic Deglycosylation

For structural analyses, protein isolates (120 μg) were lyophilized, reduced in 500 μL of a 2 mg/mL dithiothreitol solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 50°C for 90 minutes, and then alkylated with 500 μL of a 12 mg/mL iodoacetamide solution for 90 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Samples were dialyzed against 50 mmol/L ammonium bicarbonate for 24 hours at 4°C, lyophilized, and incubated with 1 mL of 50 μg/mL l-1-tosylamide-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone–treated trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C overnight. The digested peptides were then purified using a Sep-Pak C18 (200-mg) cartridge (Waters Corp., Milford, MA), lyophilized, and incubated with 2 μL (500 units/μL) of peptide:N-glycosidase F from Flavobacterium meningosepticum (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) in 200 μL of 50 mmol/L ammonium bicarbonate at 37°C for 4 hours. The mixture was further incubated with 3 μL of peptide:N-glycosidase F at 37°C overnight. The released N-glycans were purified over a Sep-Pak C18 (200-mg) cartridge. The flow-through and wash fraction containing the released N-glycans were collected, pooled, and lyophilized.

Permethylation of N-Glycans

The permethylation of N-glycans was performed using the NaOH:dimethyl sulfoxide slurry method. Here, lyophilized N-glycans were incubated with 1 mL of a NaOH:dimethyl sulfoxide slurry solution and 500 μL of methyl iodide (Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 to 30 minutes under vigorous shaking at room temperature. One milliliter of chloroform and 3 mL of Milli-Q water were then added, and the mixture was briefly vortexed to wash the chloroform fraction. The wash step was repeated three times. The chloroform fraction was dried, dissolved in 200 mL of 50% methanol, and loaded into a Sep-Pak C18 (200-mg) cartridge. The eluted fraction was lyophilized and dissolved in 10 μL of 75% methanol from which 1 μL was mixed with 1 μL 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (Sigma-Aldrich; 5 mg/mL in 50% acetonitrile with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) and spotted on a matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization polished steel target plate (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany).

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization–Time-of-Flight Mass Spectroscopy

The profiling of permethylated N-glycans was performed at Glycomics Core, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (Boston, MA). Mass spectrometry data were acquired on an UltraFlex II matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics). Reflective positive mode was used and data recorded between m/z 500 and 6000. The mass spectrometry N-glycan profiles were acquired by the aggregation of at least 20,000 laser shots. Mass spectrometry spectra were processed using mMass software version 5.5.0 (http://www.mmass.org).17 Mass peaks were manually annotated and assigned to a particular N-glycan composition when a match was found.

RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from cell cultures and impression cytology samples using an extraction reagent (TRIzol; Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Residual genomic DNA in the RNA preparation was eliminated by digestion with amplification-grade DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Five micrograms (for PCR array) or 1 μg [for real-time quantitative (qPCR)] total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis (iScript cDNA Synthesis; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Human Glycosylation PCR Array

The analysis of 84 genes encoding for glycosylation enzymes was performed using a human glycosylation PCR array (RT2 Profiler PCR array; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The array was repeated twice with independently isolated RNA. Expression values were corrected for the housekeeping genes HPRT1 and RPLP0. The 2−ΔCT and 2−ΔΔCT methods were used for relative quantitation of the number of transcripts.

qPCR

Gene expression levels were detected by qPCR using the SYBR Fast qPCR kit (Kapa Biosystems, Wilmington, MA) in a Mastercycler ep realplex thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY). Primer sequences for MGAT1 (forward, 5′-GGTGGAGTTGGTGGGTCATC-3′; reverse, 5′-GAGGAGAGGTCTTGCTTGCC-3′), MGAT2 (forward, 5′-CTGCTGCTGGACTCACTTC-3′; reverse, 5′-AATGCTGAAAGGAAAGAACACC-3′), and MGAT4B (forward, 5′-ACTTCATCCGCTTCCGCTTC-3′; reverse, 5′-TCCTTGTCTGACTGAGGGTTGT-3′) mRNA have been previously published.18, 19, 20 Primers for GAPDH were obtained from Bio-Rad (catalog number qHsaCED0038674). The following parameters were used: 2 minutes at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 5 seconds at 95°C and 30 seconds at 60°C. All samples were normalized using GAPDH housekeeping gene expression. The comparative 2−ΔΔCτ method was used for relative quantitation of the number of transcripts. No template controls were run in each assay to confirm lack of DNA contamination in the reagents used for amplification.

Enzymatic Assay

N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase activity was measured in a plate reader using a Glycosyltransferase Activity Kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cell lysates in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer were cleared of insoluble material by centrifugation at 17,115 × g and filtered through 10 kDa–cutoff centrifugal filters to remove cellular phosphate. The filters were washed with diH2O and the protein concentration of the supernatants determined using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Thereafter, 25 μL (10 μg) of protein was mixed with 25 μL of a working solution of donor and acceptor substrates to give a final concentration of 0.2 mmol/L uridine diphosphate–GlcNAc and 1 mmol/L mannotriose [Manα1-3(Manα1-6)Man]. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 1 hour at 37°C. The solution was then incubated with 50 μL of 0.2 μg/mL coupling phosphatase 1 for 10 minutes at room temperature. The released phosphate was visualized with malachite green by absorbance at 620 nm and converted to specific activity (expressed as pmol/minute per microgram) using a phosphate standard curve. To control for the presence of endogenous acceptor substrates in the cell lysates, the specific activity observed in parallel reactions lacking the mannotriose acceptor was subtracted from the total values.

MTT Assay

Cell viability was assessed by means of the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay following the manufacturer's instructions (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Briefly, cultures were incubated with a 1.2 mmol/L MTT solution at 37°C for 4 hours. The absorbance values of blue formazan were determined at 540 nm. Cell viability was expressed as MTT uptake in treated cells normalized to untreated cells.

Lectin Blot Analysis

Cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer supplemented with complete EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). After homogenization with a pellet pestle, the cell extracts were centrifuged at 17,115 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C, and the protein concentration of the supernatants were determined using the Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Proteins were separated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes, and blocked with 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone in Tris-buffered saline–Tween overnight at 4°C. Membranes were then incubated with biotin-labeled Datura stramonium lectin (DSL; 20 μg/mL; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) or Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin (PHA-L, 5 μg/mL; Vector Laboratories) for 1.5 hours at room temperature. Membranes were developed with the Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories), and glycoproteins were visualized using chemiluminescence. Densitometry was performed using ImageJ software version 1.46r (NIH, Bethesda, MD; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij).

Lectin Histochemistry

Paraffin-embedded sections (6 μm) of conjunctival tissue were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and blocked for 1 hour with 3% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline. Biotin-labeled DSL or PHA-L preparations (20 μg/mL) were applied in the presence of 1.5% bovine serum albumin for 30 minutes at room temperature. Consecutive tissue sections incubated in parallel with 1.5% bovine serum albumin alone were used as negative controls. Endogenous peroxidase activity was subsequently blocked with 1% H2O2. Staining was performed using a horseradish peroxidase–streptavidin complex (Vectastain Elite ABC horseradish peroxidase kit; Vector Laboratories) for 30 minutes. The substrate for the peroxidase was diaminobenzidine with H2O2 (SigmaFast 3,3-diaminobenzidine with metal enhancer; Sigma-Aldrich), which yields a brown deposit. Nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin QS (Vector Laboratories). Areas of positive staining were quantified using ImageJ software. The epithelial areas were hand-outlined and the intensity of brown pixels in the selected regions was measured using color deconvolution with the H DAB vector. Mean staining-intensity scores were normalized to area, and the intensity values from the corresponding negative controls were subtracted as background. In independent experiments, sections were stained with periodic acid-Schiff reagent for morphologic assessment.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism software version 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

Human Corneal Epithelial Cells Are Rich in Complex-Type Biantennary N-Glycans

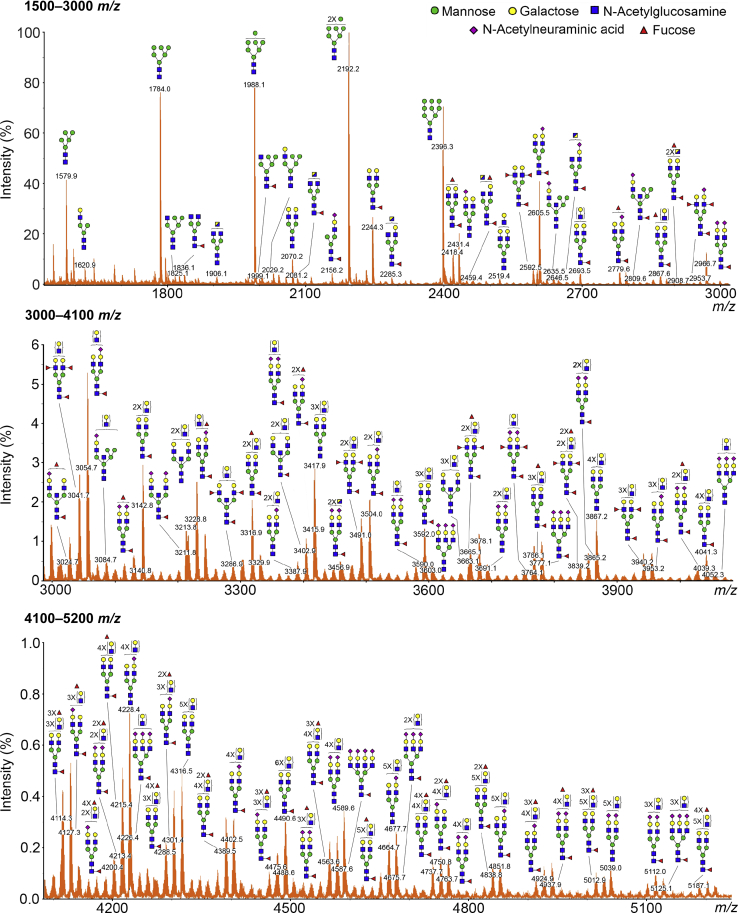

The collection of N-glycan structures expressed by any given cell or organism defines key biological process ranging from cell migration and tissue patterning to disease progression and cell death. An important prerequisite to understanding the regulation of N-glycosylation at the transcriptional level is the identification of the repertoire of oligosaccharides present on individual cell types. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight mass spectrometry was used to examine the different classes of N-glycans present in differentiated human corneal epithelial cells. The most notable features of the data included the presence of complex-type biantennary (Hex3-6HexNAc4-5Fuc0-3NeuAc0-2) and high-mannose (Hex5-9HexNAc2) N-glycans (Table 1). The spectrum profile in the middle and high m/z regions revealed the presence of numerous putative N-acetyllactosamine repeats on the biantennary structures (Figure 1). Oligosaccharides with up to five or six repeating units of N-acetyllactosamine were detected, as indicated by signals at m/z 4316, 4491, 4665, 4678, 4839, 4852, 5013, 5039, and 5187. The majority of the biantennary N-glycans were fucosylated in the core (as Fuc-HexNAc at the reducing terminal) and often capped with N-acetylneuraminic acid residues on their antennae. By comparison, fewer signals consistent with tri-antennary and tetra-antennary glycans were detected in the spectrum profile. Similarly, hybrid-type N-glycans and bisecting GlcNAc structures represented a minor portion of the total N-glycan profile.

Table 1.

Compositions and Relative Intensities of the Major Peaks in the Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization–Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrum of N-Glycans from Human Corneal Epithelial Cells

|

m/z∗ |

Composition | Relative intensity, % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Theoretical | ||

| 1579.9 | 1579.9 | Hex5HexNAc2 | 49.2 |

| 1620.9 | 1620.9 | Hex4HexNAc3 | 7.5 |

| 1784.0 | 1784.0 | Hex6HexNAc2 | 90.2 |

| 1836.0 | 1836.1 | Hex3HexNAc4Fuc1 | 6.3 |

| 1988.1 | 1988.1 | Hex7HexNAc2 | 92.3 |

| 2029.1 | 2029.2 | Hex6HexNAc3 | 4.8 |

| 2040.2 | 2040.2 | Hex4HexNAc4Fuc1 | 4.3 |

| 2070.2 | 2070.2 | Hex5HexNAc4 | 11.3 |

| 2156.2 | 2156.2 | Hex4HexNAc3Fuc1NeuAc1 | 4.8 |

| 2192.2 | 2192.2 | Hex8HexNAc2 | 100.0 |

| 2244.3 | 2244.3 | Hex5HexNAc4Fuc1 | 25.4 |

| 2396.3 | 2396.3 | Hex9HexNAc2 | 63.2 |

| 2418.4 | 2418.4 | Hex5HexNAc4Fuc2 | 13.5 |

| 2431.4 | 2431.4 | Hex5HexNAc4NeuAc1 | 17.2 |

| 2592.5 | 2592.5 | Hex5HexNAc4Fuc3 | 6.1 |

| 2600.5 | 2600.5 | Hex10HexNAc2 | 4.8 |

| 2605.5 | 2605.5 | Hex5HexNAc4Fuc1NeuAc1 | 32.2 |

| 2693.5 | 2693.5 | Hex6HexNAc5Fuc1 | 4.4 |

| 2779.6 | 2779.6 | Hex5HexNAc4Fuc2NeuAc1 | 5.2 |

| 2966.7 | 2966.7 | Hex5HexNAc4Fuc1NeuAc2 | 8.1 |

All peaks were observed as [M + Na]+ ions.

Figure 1.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) profile of N-glycans on glycoproteins isolated from human corneal epithelial cells. The N-linked glycans were released enzymatically by peptide:N-glycosidase F, permethylated, and profiled by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Magnified portions at m/z = 1500 → 3000 (top panel), 3000 → 4100 (middle panel), and 4100 → 5200 (bottom panel) are shown. Putative structures are assigned based on compositional information and known biosynthetic pathways. Most of the N-glycans have compositions consistent with bi-antennary complex-type glycans, carrying N-acetyllactosamine residues, and high-mannose structures. All molecular ions detected are present in the form of [M + Na]+.

Effect of Inflammatory Stress on Corneal Epithelial N-Glycosylation Is Cytokine Dependent

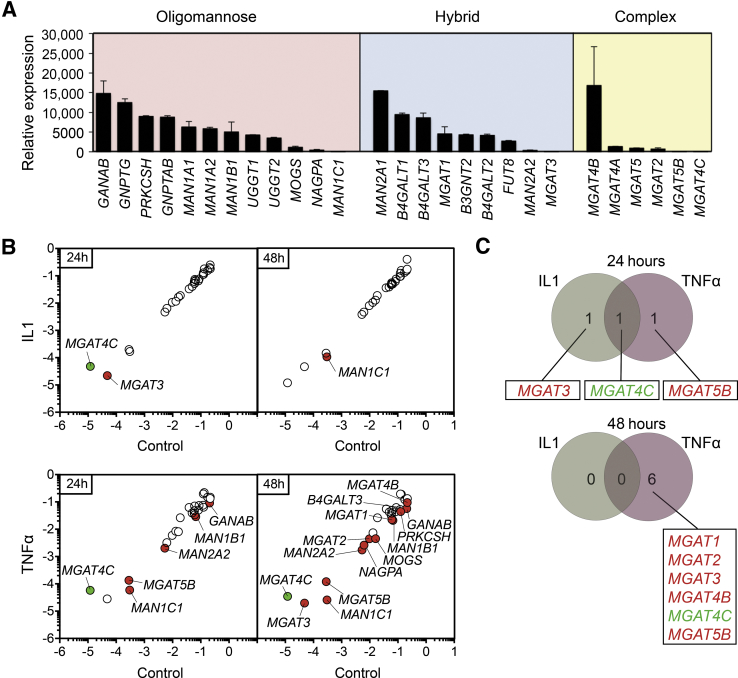

The results mentioned in the previous paragraph prompted us to examine the transcriptional levels of known N-glycosylation enzymes in human corneal epithelial cells using a pathway-focused PCR array. Enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of all three major types of N-glycans, which comprise high-mannose, hybrid, and complex-type, were identified (Figure 2A). A direct comparison of the relative levels of expression revealed the presence of enzymes involved in the trimming of glucose (GANAB, PRKCSH) and mannose (MAN1A1, MAN1A2, MAN1B1), which are required for the conversion of oligomannose structures into branched N-glycans. The expression of MGAT1, involved in initiating the synthesis of hybrid and complex-type N-glycans; MAN2A1, required for the synthesis of complex-type N-glycans; as well as transferases carrying out core fucosylation (FUT8) and the poly-N-acetyllactosamine extension (B3GN2, B4GALT1, B4GALT2, B4GALT3), was also observed. The relatively low levels of MGAT3 were consistent with the low amount of bisecting GlcNAc structures found in human corneal epithelial cells. Although some discrepancies were identified between gene expression and glycan content, such as the relative high levels of MGAT4B involved in the synthesis of tri-antennary structures, the transcriptional data on the major part echoed the N-glycosylation profile obtained by mass spectrometry.

Figure 2.

IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α differentially affect the expression of genes involved in the processing of N-glycans. A: Relative transcript abundance of genes encoding enzymes involved in trimming and branching oligomannose, hybrid, and complex-type N-glycans in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus of human corneal epithelial cells. The expression of N-glycan–processing genes was assessed by real-time quantitative PCR using a human glycosylation PCR array and normalized using the 2−ΔΔCτ method with MGAT4C as calibrator. B: Scatterplot comparing the expression of N-glycan–processing genes in untreated control cells and cells treated with 10 ng/mL IL-1β or 40 ng/mL TNFα for 24 and 48 hours. The green and red dots indicate at least twofold up- or down-regulation, respectively, compared with control. Values were determined using the 2−ΔCτ method. C: Venn diagrams depicting the distribution of Golgi N-acetylglucosaminyltransferases associated with IL-1β, TNFα, or both components, at 24 and 48 hours post-treatment. Up-regulated genes are indicated in green, and down-regulated genes are indicated in red. The array data shown in these experiments were repeated twice, with independently isolated RNA pooled from three tissue culture plates. Data are expressed as means ± SD.

To assess the effects of proinflammatory conditions on the N-glycosylation pathway, cultures of human corneal epithelial cells were treated with IL-1β and TNFα, two key mediators of the inflammatory response known to exacerbate damage during chronic disease. Figure 2B depicts the changes in the relative expression of genes involved in N-glycan processing as scatterplots using a twofold cutoff (Supplemental Table S1). The effect of IL-1β was limited to the down-regulation of MGAT3 and MAN1C1 at 24 and 48 hours, respectively. MGAT4C, a putative and poorly characterized N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase, was the only up-regulated gene in these experiments. The effect of TNFα, on the other hand, was much greater than that of IL-1β. At 24 hours, TNFα promoted down-regulation of four genes involved in the trimming of glucose and mannose (GANAB, MAN1B1, MAN2A2, MAN1C1), whereas 13 genes were down-regulated at 48 hours and included those necessary for the trimming (GANAB, PRKCHS, MOGS, MAN1B1, MAN2A2, MAN1C1) and elongation (MGAT1, MGAT2, MGAT3, MGAT4B, MGAT5B, B4GALT3) of the N-glycan chains. Observation of the response to IL-1β and TNFα evidenced major differences between the efficacies of both cytokines in regulating the transcription of MGAT genes that create complex-type N-glycan structures (Figure 2C).

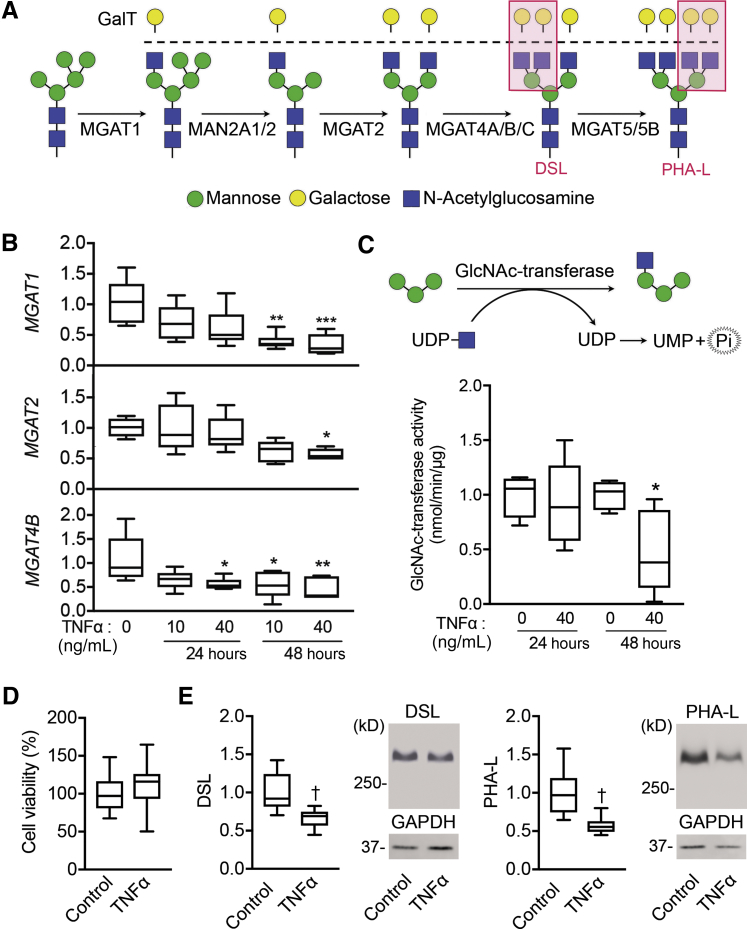

TNFα Reduces N-Acetylglucosaminyltransferase Activity and N-Glycan Branching

The MGAT family of genes is involved in encoding enzymes that transfer GlcNAc to glycoproteins transiting the medial Golgi, forming mono-, bi-, tri-, and tetra-antennary branched N-glycans (Figure 3A). In an effort to validate the data obtained by PCR array showing reduced MGAT gene expression after TNFα treatment, qPCR experiments were performed using primers against three of the most highly expressed branching enzymes in corneal epithelial cells, MGAT1, MGAT2, and MGAT4B, which contribute to the formation of mono-, bi-, and tri-antennary structures. The measured levels of expression in these experiments confirmed that TNFα had a significant effect in lowering the number of MGAT transcripts at 48 hours, with little or no effect at 24 hours (Figure 3B). Since TNFα can directly activate a spectrum of genomic targets within the first few hours of treatment,21 our results suggest an indirect mechanism of control by which the gene network downstream of TNF signaling regulates MGAT expression.

Figure 3.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α reduces Golgi N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase activity and promotes loss of N-glycan branching. A: Branches in complex-type N-glycans are processed through a series of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferases and mannosidases located in the medial Golgi compartment. Red boxes indicate the GlcNAc-branched N-glycans recognized by Datura stramonium lectin (DSL) or Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin (PHA-L). B: Quantitative RT-PCR validation analysis showing reduced expression of genes involved in the formation of mono-, bi-, and tri-antennary complex-type glycans (MGAT1, MGAT2, and MGAT4B) after TNFα treatment. C:N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase activity in human corneal epithelial cells was assessed by measurement of released phosphate after the transfer of uridine diphosphate (UDP)–N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) to a mannotriose acceptor substrate. D: Cell viability in stratified cell cultures treated with 40 ng/mL TNFα for 48 hours was assayed based on 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide dye uptake (absorbance at 570 nm). E: Cell lysates from control cells and cells treated with TNFα for 72 hours were run on 1% agarose gels and then blotted to nitrocellulose membranes. Blotted proteins were probed with biotinylated lectins specific for GlcNAc-branched N-glycans (DSL and PHA-L). Representative images of the membranes are presented. Results in B–E represent at least two independent experiments performed in triplicate. The box-and-whisker plots show the 25 and 75 percentiles (boxes) and the median and the minimum and maximum data values (whiskers). Significance was determined using one-way analysis of variance with the Tukey post hoc test (B) and the t-test (C–E). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 versus 0 ng/mL TNFα; †P < 0.01 versus control. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; MAN, α-mannosidase; MGAT, mannoside acetylglucosaminyltransferase; UMP, uridine monophosphate.

To further determine whether a reduction in the number of MGAT transcripts is correlated with impaired enzymatic activity, a glycosyltransferase-activity assay was performed in whole-cell lysates isolated from human corneal epithelial cells. Here, the ability of endogenous N-acetylglucosaminyltransferases to transfer uridine diphosphate–GlcNAc to mannotriose was determined by measuring free phosphate released from uridine diphosphate. As expected, the differences in N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase activity were evident after 48 hours of TNFα stimulation (Figure 3C), when the levels of MGAT transcripts were significantly reduced. In control experiments, treatment with TNFα did not have a significant effect on cell viability (Figure 3D). Next, lectins were used to measure the levels of branched oligosaccharides in cell cultures treated with TNFα for 72 hours. Complex N-glycans containing branched GlcNAc were measured using DSL and PHA-L.22 Incubation with TNFα resulted in a diminution of the levels of DSL and PHA-L staining, supporting a role for TNFα in the suppression of N-glycan processing in corneal epithelial cells (Figure 3E).

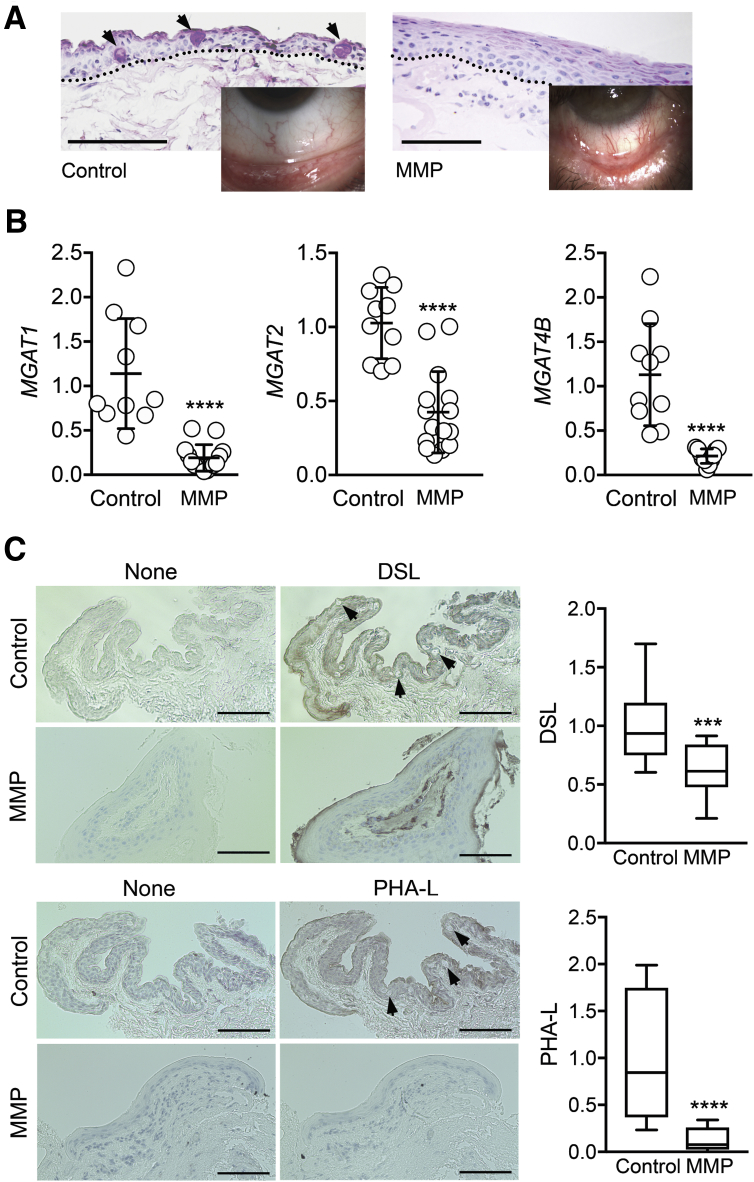

N-Glycan Branching Is Impaired in Ocular Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid

Mucous membrane pemphigoid is an inflammatory autoimmune disorder that affects several mucosal surfaces in the body, particularly the oral cavity and the eyes.23 At the ocular surface it can lead to scarring, loss of goblet cells, and progressive metaplasia that changes the normal mucosal epithelium into a squamous keratinized epithelium (Figure 4A). Through the use of an impression cytology approach, epithelial cells were collected from the conjunctiva of patients with ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid and control subjects. Analysis of gene expression in these samples demonstrated a robust reduction in the amount of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase transcripts. The levels of MGAT1 mRNA in pemphigoid were 83% lower as compared to control, whereas those of MGAT2 and MGAT4B were decreased by 59% and 81%, respectively (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Golgi N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase levels are substantially decreased in ocular autoimmune disease. A: Conjunctival tissue sections from control subjects and patients with ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) were stained with periodic acid-Schiff. The arrows indicate goblet cells, whereas the dotted lines outline the basement membrane zone. The inset shows the morphologic appearance of the conjunctiva. B: Human conjunctival epithelial cells were collected in vivo via impression cytology. After total RNA extraction and reverse transcription, real-time quantitative PCR was performed using primers for MGAT1, MGAT2, and MGAT4B. C: Conjunctival tissue sections from control subjects and patients with ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid were incubated with biotin-labeled Datura stramonium lectin (DSL) or Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin (PHA-L). Consecutive sections incubated with bovine serum albumin alone were used as negative controls. The arrows indicate goblet cells. Each dot in B represents an individual biological sample, whereas quantification in C was performed by analyzing at least 10 histologic areas from three individuals in each group. The box-and-whisker plots show the 25 and 75 percentiles (boxes) and the median and the minimum and maximum data values (whiskers). Significance was determined using the t-test. Data are expressed as means ± SD. ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 versus control. Scale bars: 50 μm (A); 100 μm (C).

The glycosylation status of the conjunctival epithelium was determined in patients with ocular pemphigoid using lectin histochemical staining. Similar to the in vitro studies, the presence of branched GlcNAc oligosaccharides in tissue sections was evaluated with DSL and PHA-L. Positive DSL staining was detected throughout the entire stratified epithelium in normal conjunctiva (Figure 4C). On the other hand, binding of the lectin to pemphigoid tissue was reduced in the basal and suprabasal epithelial cell layers but not the apical ones. In the case of PHA-L, positive reactivity was again observed throughout the entire normal stratified epithelium; however, the signal was barely visible in diseased tissue. Quantification of the lectin signal within the epithelial regions of the conjunctiva confirmed that pemphigoid had significantly weaker reactivity as compared to control tissue (Figure 4C).

Discussion

Estimates indicate that at least 1% of the genes in the mammalian genome are involved in the production of glycan determinants.24 Expression of those genes leads to complex biosynthetic pathways and generates a vast structural heterogeneity in oligosaccharides that has been historically overlooked. Research performed over the past decade, however, points to important contributions of the N-glycome in the survival of multicellular organisms, in part, by regulating molecular and cellular interactions. In this regard, N-glycan multiplicity and branching have been implicated in the regulation of processes crucial to cell growth and differentiation.8 Whether the N-glycome experiences regulatory control and changes in disease states has been the subject of intense study in recent years. Here, we have described a series of experiments demonstrating alterations in the N-glycosylation machinery in patients with mucous membrane pemphigoid and identified the proinflammatory cytokine TNFα as a novel regulatory component of the Golgi N-glycan–branching pathway at the ocular surface.

Acquired and inherited perturbations in N-glycan biosynthesis have been observed in a number of pathologies. Inherited glycosylation diseases are rare and were initially identified in the early 1980s based on clinical symptoms and the presence of glycoproteins with truncated N-glycans in serum.25 The clinical presentations are highly variable and include mental retardation, cerebellar dysfunction, endocrine abnormalities, and retinitis pigmentosa. By comparison, acquired perturbations of N-glycosylation are much more prevalent and have been found in multiple disorders ranging from inflammation to infection and malignancy. Much work in autoimmune disease has focused on understanding the basic mechanisms by which N-glycans determine the pathogenicity of autoantibodies and the immunogenicity of autoantigens.26, 27 Research in relation to the latter has demonstrated that structural variation in cell-surface N-glycans contributes to immune self-recognition. In mice, mutation of Golgi mannosidase II, encoded by the Man2a1 gene, has been shown to reduce complex-type N-glycan branching and to lead to a systemic autoimmune disease similar to lupus in humans.28 Mechanistically, the formation of defective N-glycans caused by mannosidase II deficiency results in the generation of mannose ligands for lectin receptors that trigger chronic activation of the innate immune system.29 Additional studies in mice have also evidenced that Mgat5-modified glycans induce the formation of galectin–glycoprotein lattices that restrict the recruitment of T-cell receptors to the site of antigen presentation, suggesting that dysregulation of the Golgi N-glycosylation pathway in humans may increase the susceptibility to autoimmune diseases.30 The findings that N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase expression changes in ocular pemphigoid epithelium add to previous reports demonstrating alteration of N-glycosylation, such as galactosylation of IgG, in human autoimmune disease.31 Although it is attractive to speculate that altered N-glycosylation could contribute to the development of the disease, care should be taken when inferring an association between N-glycosylation and autoimmune susceptibility. Current research looking at pleiotropy to support a connection between N-glycosylation of IgG and autoimmune disease at the genetic level has produced controversial results.32, 33

Our results support a model by which inflammatory stress itself can prompt changes in the N-glycan branching pathway at the ocular surface. Clinical observations and research conducted with experimental autoimmune models indicate that the initiation and propagation of autoimmune inflammation is largely driven by the presence of proinflammatory cytokines.34 TNFα is a cytokine produced primarily by macrophages abundantly expressed in mucous membrane pemphigoid.35 Binding of TNFα to its receptors triggers a plethora of signaling cascades that lead to a myriad of cellular responses, including cell death, survival, differentiation, proliferation, and migration.36 TNFα also affects the expression and activities of glycosyltransferases. For instance, TNFα increases the galactosyltransferase activity of synoviocytes, whereas in bronchial mucosa it increases the activities of fucosyltransferase and sialyltransferase enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of LewisX epitopes.37, 38 Interestingly, in a previous study, treatment of primary human chondrocytes with TNFα induces a considerable shift from oligomannose glycans toward complex-type N-glycans.39 In that study, the authors also found a similar response when evaluating the effects of IL-1β. Those results contrast with the findings showing decreased N-glycan branching and differential responses to IL-1β and TNFα in corneal epithelial cells. It has long been recognized that the effect of proinflammatory cytokines on biological processes such as protein glycosylation are cell-type specific.40 The finding that TNFα exhibits little functional redundancy with IL-1β and impairs N-glycan branching in corneal epithelial cells suggests a specific role for this cytokine in modulating the ocular surface epithelial phenotype during inflammatory conditions.

The implications of altered N-glycan branching at the ocular surface remain elusive. The data indicate that the vast majority of N-glycans in corneal epithelial cells are composed of complex-type biantennary N-glycans with multiple N-acetyllactosamine residues. It is seemingly possible that this composition will be crucial to the interactions of the surface glycocalyx with galectins. Galectin-3 is one of the most highly expressed glycogenes in the human ocular surface and is known to bind both nonreducing terminal and terminal N-acetyllactosamine.41 On the other hand, galectins 1 and 7, also expressed at the ocular surface but at lower levels, possess either a weaker affinity for N-acetyllactosamine or have a preference for nonreducing terminal N-acetyllactosamine. It is likely that changes in the branching of N-glycans will affect the dynamics of galectins at the cell surface, leading to distinctive signaling responses. The synthesis of branched N-glycans contributes to the stability and barrier function of the ocular surface epithelial glycocalyx.42 In these experiments, abrogation of MGAT1 expression significantly reduced the amount of cell surface galectin-3 and led to the transcriptional activation of the molecular chaperone binding immunoglobulin protein and the transcription factor CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein, suggesting a model by which N-glycan–branching impairment causes endoplasmic reticulum stress. Deciphering the molecular mechanisms by which N-glycan branching regulates the proper differentiation of mucosal surfaces should be an important goal of future research and will contribute to the understanding of how tissue dysfunction is regulated in ocular autoimmune disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ilene Gipson for providing the human corneal epithelial cell line and Bianai Fan for performing the periodic acid-Schiff staining.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH NEI grant R01EY026147 (P.A.), NIH NEI Core grant P30EY003790 (P.A.), and National Center for Functional Glycomics grant P41GM103694 (S.L.).

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.10.012.

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Apweiler R., Hermjakob H., Sharon N. On the frequency of protein glycosylation, as deduced from analysis of the SWISS-PROT database. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1473:4–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cummings R.D. The repertoire of glycan determinants in the human glycome. Mol Biosyst. 2009;5:1087–1104. doi: 10.1039/b907931a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moremen K.W., Tiemeyer M., Nairn A.V. Vertebrate protein glycosylation: diversity, synthesis and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:448–462. doi: 10.1038/nrm3383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varki A. Evolutionary forces shaping the Golgi glycosylation machinery: why cell surface glycans are universal to living cells. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a005462. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanley P. Golgi glycosylation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a005199. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ioffe E., Stanley P. Mice lacking N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I activity die at mid-gestation, revealing an essential role for complex or hybrid N-linked carbohydrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:728–732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metzler M., Gertz A., Sarkar M., Schachter H., Schrader J.W., Marth J.D. Complex asparagine-linked oligosaccharides are required for morphogenic events during post-implantation development. EMBO J. 1994;13:2056–2065. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06480.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau K.S., Partridge E.A., Grigorian A., Silvescu C.I., Reinhold V.N., Demetriou M., Dennis J.W. Complex N-glycan number and degree of branching cooperate to regulate cell proliferation and differentiation. Cell. 2007;129:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Partridge E.A., Le Roy C., Di Guglielmo G.M., Pawling J., Cheung P., Granovsky M., Nabi I.R., Wrana J.L., Dennis J.W. Regulation of cytokine receptors by Golgi N-glycan processing and endocytosis. Science. 2004;306:120–124. doi: 10.1126/science.1102109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodnow C.C. Multistep pathogenesis of autoimmune disease. Cell. 2007;130:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stern M.E., Schaumburg C.S., Dana R., Calonge M., Niederkorn J.Y., Pflugfelder S.C. Autoimmunity at the ocular surface: pathogenesis and regulation. Mucosal Immunol. 2010;3:425–442. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldmann M., Brennan F.M., Williams R.O., Cope A.P., Gibbons D.L., Katsikis P.D., Maini R.N. Evaluation of the role of cytokines in autoimmune disease: the importance of TNF alpha in rheumatoid arthritis. Prog Growth Factor Res. 1992;4:247–255. doi: 10.1016/0955-2235(92)90022-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saw V.P., Dart R.J., Galatowicz G., Daniels J.T., Dart J.K., Calder V.L. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid and its effect on conjunctival fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:5310–5317. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kollias G., Douni E., Kassiotis G., Kontoyiannis D. On the role of tumor necrosis factor and receptors in models of multiorgan failure, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and inflammatory bowel disease. Immunol Rev. 1999;169:175–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Argueso P., Gipson I.K. Assessing mucin expression and function in human ocular surface epithelia in vivo and in vitro. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;842:313–325. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-513-8_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Argueso P., Tisdale A., Mandel U., Letko E., Foster C.S., Gipson I.K. The cell-layer- and cell-type-specific distribution of GalNAc-transferases in the ocular surface epithelia is altered during keratinization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:86–92. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strohalm M., Kavan D., Novak P., Volny M., Havlicek V. mMass 3: a cross-platform software environment for precise analysis of mass spectrometric data. Anal Chem. 2010;82:4648–4651. doi: 10.1021/ac100818g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beheshti Zavareh R., Sukhai M.A., Hurren R., Gronda M., Wang X., Simpson C.D., Maclean N., Zih F., Ketela T., Swallow C.J., Moffat J., Rose D.R., Schachter H., Schimmer A.D., Dennis J.W. Suppression of cancer progression by MGAT1 shRNA knockdown. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lappas M. Effect of pre-existing maternal obesity, gestational diabetes and adipokines on the expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism in adipose tissue. Metabolism. 2014;63:250–262. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ide Y., Miyoshi E., Nakagawa T., Gu J., Tanemura M., Nishida T., Ito T., Yamamoto H., Kozutsumi Y., Taniguchi N. Aberrant expression of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase-IVa and IVb (GnT-IVa and b) in pancreatic cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;341:478–482. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian B., Nowak D.E., Jamaluddin M., Wang S., Brasier A.R. Identification of direct genomic targets downstream of the nuclear factor-kappaB transcription factor mediating tumor necrosis factor signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17435–17448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500437200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cummings R.D., Darvill A.G., Etzler M.E., Hahn M.G. Glycan-recognizing probes as tools. In: Varki A., Cummings R.D., Esko J.D., Stanley P., Hart G.W., Aebi M., Darvill A.G., Kinoshita T., Packer N.H., Prestegard J.H., Schnaar R.L., Seeberger P.H., editors. Essentials of Glycobiology. Cold Spring Harbor; 2015. pp. 611–625. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neff A.G., Turner M., Mutasim D.F. Treatment strategies in mucous membrane pemphigoid. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:617–626. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowe J.B., Marth J.D. A genetic approach to Mammalian glycan function. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:643–691. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeze H.H., Schachter H. Genetic disorders of glycosylation. In: Varki A., Cummings R.D., Esko J.D., Freeze H.H., Stanley P., Bertozzi C.R., Hart G.W., Etzler M.E., editors. Essentials of Glycobiology. Cold Spring Harbor; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alavi A., Axford J.S. Sweet and sour: the impact of sugars on disease. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:760–770. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chien M.W., Fu S.H., Hsu C.Y., Liu Y.W., Sytwu H.K. The modulatory roles of N-glycans in T-cell-mediated autoimmune diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:E780. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chui D., Sellakumar G., Green R., Sutton-Smith M., McQuistan T., Marek K., Morris H., Dell A., Marth J. Genetic remodeling of protein glycosylation in vivo induces autoimmune disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1142–1147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green R.S., Stone E.L., Tenno M., Lehtonen E., Farquhar M.G., Marth J.D. Mammalian N-glycan branching protects against innate immune self-recognition and inflammation in autoimmune disease pathogenesis. Immunity. 2007;27:308–320. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Demetriou M., Granovsky M., Quaggin S., Dennis J.W. Negative regulation of T-cell activation and autoimmunity by Mgat5 N-glycosylation. Nature. 2001;409:733–739. doi: 10.1038/35055582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Axford J.S. Glycosylation and rheumatic disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1455:219–229. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(99)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lauc G., Huffman J.E., Pucic M., Zgaga L., Adamczyk B., Muzinic A. Loci associated with N-glycosylation of human immunoglobulin G show pleiotropy with autoimmune diseases and haematological cancers. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yarwood A., Viatte S., Okada Y., Plenge R., Yamamoto K., Braggss R., Barton A., Symmons D., Raychaudhuri S., Klareskog L., Gregersen P., Worthington J., Eyre S. Loci associated with N-glycosylation of human IgG are not associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a Mendelian randomisation study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:317–320. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-207210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moudgil K.D., Choubey D. Cytokines in autoimmunity: role in induction, regulation, and treatment. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011;31:695–703. doi: 10.1089/jir.2011.0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cordero Coma M., Yilmaz T., Foster C.S. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha in conjunctivae affected by ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007;85:753–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradley J.R. TNF-mediated inflammatory disease. J Pathol. 2008;214:149–160. doi: 10.1002/path.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang X., Lehotay M., Anastassiades T., Harrison M., Brockhausen I. The effect of TNF-alpha on glycosylation pathways in bovine synoviocytes. Biochem Cel Biol. 2004;82:559–568. doi: 10.1139/o04-058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delmotte P., Degroote S., Lafitte J.J., Lamblin G., Perini J.M., Roussel P. Tumor necrosis factor alpha increases the expression of glycosyltransferases and sulfotransferases responsible for the biosynthesis of sialylated and/or sulfated Lewis x epitopes in the human bronchial mucosa. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:424–431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109958200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pabst M., Wu S.Q., Grass J., Kolb A., Chiari C., Viernstein H., Unger F.M., Altmann F., Toegel S. IL-1beta and TNF-alpha alter the glycophenotype of primary human chondrocytes in vitro. Carbohydr Res. 2010;345:1389–1393. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang X., Yip J., Anastassiades T., Harrison M., Brockhausen I. The action of TNFalpha and TGFbeta include specific alterations of the glycosylation of bovine and human chondrocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brewer C.F. Thermodynamic binding studies of galectin-1, -3 and -7. Glycoconj J. 2002;19:459–465. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000014075.62724.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taniguchi T., Woodward A.M., Magnelli P., McColgan N.M., Lehoux S., Jacobo S.M.P., Mauris J., Argueso P. N-Glycosylation affects the stability and barrier function of the MUC16 mucin. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:11079–11090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.770123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.