The crystal structure of a Y27W mutant of the Dishevelled2 DIX domain (DIX-Y27W) is reported at 1.64 Å resolution, which is the highest resolution to be reported for a DIX-domain structure. DIX-Y27W formed a helical polymer similar to other reported DIX domains.

Keywords: Wnt signalling pathway, Dishevelled, DIX domain, X-ray structure analysis, polymerizing domain

Abstract

Dishevelled (Dvl) is a positive regulator of the canonical Wnt pathway that downregulates the phosphorylation of β-catenin and its subsequent degradation. Dvl contains an N-terminal DIX domain, which is involved in its homooligomerization and interactions with regulators of the Wnt pathway. The crystal structure of a Y27W mutant of the Dishevelled2 DIX domain (DIX-Y27W) has been determined at 1.64 Å resolution. DIX-Y27W has a compact ubiquitin-like fold and self-associates with neighbouring molecules through β-bridges, resulting in a head-to-tail helical molecular arrangement similar to previously reported structures of DIX domains. Glu23 of DIX-Y27W forms a hydrogen bond to the side chain of Trp27, corresponding to the Glu762⋯Trp766 hydrogen bond of the rat Axin DIX domain, whereas Glu23 in the Y27D mutant of the Dishevelled2 DIX domain forms a salt bridge to Lys68 of the adjacent molecule. The high-resolution DIX-Y27W structure provides details of the head-to-tail interaction, including solvent molecules, and also the plausibly wild-type-like structure of the self-association surface compared with previously published Dvl DIX-domain mutants.

1. Introduction

The Wnt/β-catenin or canonical Wnt pathway, which is conserved from the most primitive animals to mammals, regulates diverse aspects of embryonic development and tissue homeostasis (Clevers & Nusse, 2012 ▸; Nusse & Clevers, 2017 ▸). β-Catenin acts as a central factor which promotes the transcription of the Wnt target genes in the intracellular signalling cascade of the pathway. In the absence of a Wnt signal, β-catenin undergoes phosphorylation mediated by the so-called ‘Axin degradasome’, which involves Axin, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and two serine-threonine protein kinases [glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) and casein kinase 1α (CK1α)], and subsequent ubiquitination followed by proteasomal degradation. The Axin degradasome is inhibited by the assembly of the Wnt signalosome, which is initiated by the binding of Wnt to its receptor Frizzled and its co-receptor LRP5/6. The Wnt signalosome recruits Dishevelled (Dvl), a positive factor of the pathway, to the plasma membrane (Bienz, 2014 ▸).

Dvl has three functional regions: the DIX (Dishevelled–Axin), PDZ (post-synaptic density protein-95, Drosophila disc large tumour suppressor and zonula occludens-1) and DEP (Dishevelled, Egl-10 and pleckstrin) domains, which are connected by long flexible linkers. The DIX domain is indispensable for the binding of Dvl to Axin (Fiedler et al., 2011 ▸). Both the PDZ (Wong et al., 2003 ▸) and DEP (Tauriello et al., 2012 ▸) domains were thought to bind to the Frizzled receptor, but recent studies have indicated that the PDZ domain is dispensable for the recruitment of Dvl to Frizzled (Gammons, Rutherford et al., 2016 ▸; Gammons, Renko et al., 2016 ▸). Human Dvl2 has a total of 736 amino-acid residues and a molecular weight of 79 kDa, and the three domains are composed of residues 12–93 for the DIX domain (Fig. 1 ▸ a), 264–354 for the PDZ domain and 422–505 for the DEP domain (Zhang et al., 2009 ▸; Madrzak et al., 2015 ▸; Gammons, Renko et al., 2016 ▸).

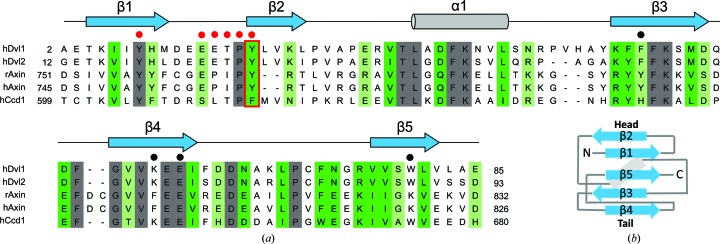

Figure 1.

(a) Amino-acid sequence alignment of the DIX domains of Dvl, Axin and Ccd1 performed using Clustal Omega (Sievers et al., 2011 ▸) based on scoring by the Gonnet PAM 250 matrix. Secondary-structural elements of DIX-Y27W are shown at the top. Fully conserved residues (grey) and residue groups with strongly (green; scoring more than 0.5) or weakly (light green; scoring between 0.0 and 0.5 or equal to 0.5) similar properties are highlighted. Tyr27 of Dvl2-DIX and its corresponding residues in the other DIX domains are shown in a red box. Residues shown in Figs. 4 ▸(a) and 4 ▸(c) are indicated by red (head surface) or black (tail surface) circles. (b) The topology of five β-strands and an α-helix (grey box) in DIX-Y27W.

The DIX domain has a ubiquitin-fold structure that is responsible for the polymerization of Dvl, which increases its avidity for the weakly associating proteins of the signalosome, including Axin, by raising its local concentration (Bienz, 2014 ▸). Crystal structures of the DIX domains of Axin, Dvl and coiled-coil-DIX1 (Ccd1) have revealed that they polymerize in a ‘head-to-tail’ manner through β-strand 2 (β2) of a monomer and β-strand 4 (β4) of the adjacent molecule in the crystals (Fig. 1 ▸ b; Schwarz-Romond et al., 2007 ▸; Liu et al., 2011 ▸; Madrzak et al., 2015 ▸; Terawaki et al., 2017 ▸).

The crystal structures of DIX-domain mutants of mouse Dvl1 (Y17D mutant; Liu et al., 2011 ▸) and human Dvl2 (Y27D mutant; Madrzak et al., 2015 ▸) have been determined at 2.85 and 2.69 Å resolution, respectively. These mutations, called ‘M4’, on their β2 surfaces were designed based on the crystal structure of the rat Axin DIX domain (rAxin-DIX) to block polymerization (Schwarz-Romond et al., 2007 ▸); size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) analyses indicated that they are monomeric in solution (Liu et al., 2011 ▸), but both form polymers in the crystals.

Previous attempts to obtain diffracting crystals of the wild-type DIX domains of Dvl1 (Dvl1-DIX; Liu et al., 2011 ▸) and Dvl2 (Dvl2-DIX; Schwarz-Romond et al., 2007 ▸) were unsuccessful, probably owing to the formation of large, heterogeneous assemblies at high protein concentrations. The M4 mutation (Y17D and Y27D in Dvl1-DIX and Dvl2-DIX, respectively) blocks polymerization of the domain and significantly increases the solubility of Dvl1-DIX and Dvl2-DIX, probably by reducing the hydrophobicity of the β2 surface of the domain. However, this mutation seemed to dramatically alter the structure of the hydrophobic cluster formed at the DIX–DIX interface of the head-to-tail interaction because Tyr27 is a key residue in the interface. We therefore designed a new Dvl2-DIX mutant, Y27W (DIX-Y27W), which is likely to weaken the self-association of the domain by inducing a steric repulsion against the adjacent molecule with a bulkier side chain while still maintaining the hydrophobicity of the hydrophobic cluster.

We successfully obtained diffracting crystals of DIX-Y27W and determined its structure at 1.64 Å resolution. In this study, we provide a pseudo-wild-type structure of Dvl2-DIX, including a detailed solvent structure.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Macromolecule production

A synthetic DNA, codon-optimized for Escherichia coli expression by GeneArt GeneOptimizer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), producing the Dvl2-DIX C80S mutant (human Dvl2, residues 13–93) was amplified by PCR using forward and reverse primers containing a TEV protease recognition sequence and a stop codon, respectively (Table 1 ▸). The C80S mutation was introduced to avoid the formation of intermolecular disulfide bridges through Cys80. The reported structures of Dvl-DIX (Liu et al., 2011 ▸; Madrzak et al., 2015 ▸) suggest that this residue is not involved in the DIX–DIX interface and therefore this mutation is not likely to block its self-association. The amplified DNA fragment was subcloned into the pET-49b vector (Merck Millipore) using an In-Fusion HD cloning kit (Takara Bio, Japan). The Y27W point mutation on the self-association interface was carried out by the inverse PCR method (Ochman et al., 1988 ▸). The construct was transformed into E. coli Rosetta2 (DE3) cells and grown in 5 l Luria–Bertani broth containing 30 mg ml−1 kanamycin and 30 mg ml−1 chloramphenicol at 310 K until the OD600 reached 0.5. Expression of recombinant protein was then induced by incubation at 300 K for 3 h in the presence of 1.0 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside. Cultured cells were collected by centrifugation at 10 000g for 5 min at 277 K.

Table 1. Macromolecule-production information.

| Source organism | Homo sapiens |

| DNA source | Dishevelled2, residues 13–93; optimized for E. coli expression |

| Forward primer† | GAGAACCTCTACTTCCAG GGCGAAACCAAAGTGATTTATCATCTGGAT |

| Reverse primer‡ | TTAATCGCTGCTCACCAGCCAGC |

| Expression vector | pET-49b |

| Expression host | E. coli Rosetta2 (DE3) |

| Complete amino-acid sequence of the construct produced§ | GETKVIYHLDEEETPYWLVKIPVPAERITLGDFKSVLQRPAGAKYFFKSMDQDFGVVKEEISDDNARLPSFNGRVVSWLVSSD |

The underlined sequence corresponds to the TEV protease recognition site.

The underlined sequence corresponds to the stop codon.

The Y27W mutation is underlined.

The cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and then disrupted by sonication. The cell lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 23 000g and then applied onto a column containing 10 ml Glutathione Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare). The column was washed with TEV protease buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM dithiothreitol. The protein of interest was then cleaved off from the 6×His-GST tag bound to the resin by adding TEV protease and incubating overnight at 277 K. The recovered protein solution was concentrated using Amicon stirred cells (Merck Millipore) and applied onto a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg column (GE Healthcare) with a buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 0.2 M NaCl. The eluted fractions containing DIX-Y27W were collected and concentrated to 3.3 mg ml−1.

2.2. Crystallization

Crystallization was performed by the sitting-drop vapour-diffusion method at 277 K using 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One) with the crystallization screening kits Wizard I, II, III and IV and Precipitant Synergy from Rigaku Reagents and PEGRx 1, PEGRx 2, PEG/Ion and PEG/Ion 2 from Hampton Research. Diffracting crystals were obtained using Wizard IV condition No. 36 (Table 2 ▸).

Table 2. Crystallization.

| Method | Sitting-drop vapour diffusion |

| Plate type | Greiner CrystalQuick 96-well plate, round bottom |

| Temperature (K) | 277 |

| Protein concentration (mg ml−1) | 3.3 |

| Buffer composition of protein solution | 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 0.2 M NaCl |

| Composition of reservoir solution | 20%(w/v) PEG 6000, 100 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 200 mM LiCl |

| Volume and ratio of drop | 1.0 µl:1.0 µl |

| Volume of reservoir (µl) | 100 |

2.3. Data collection and processing

The X-ray diffraction data set was collected on the BL44XU beamline at SPring-8, Japan using a Rayonix MX225HE detector system. The crystals were cryoprotected by flash-soaking in the mother liquor (Wizard IV condition No. 36) supplemented with 10%(v/v) glycerol immediately before cooling to 100 K in a nitrogen-gas stream on the beamline. Diffraction data were indexed, integrated and scaled with XDS (Kabsch, 2010 ▸). Data-collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 3 ▸.

Table 3. Data collection and processing.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| Diffraction source | BL44XU, SPring-8 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9000 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 |

| Detector | Rayonix MX225HE |

| Crystal-to-detector distance (mm) | 300 |

| Rotation range per image (°) | 1.0 |

| Total rotation range (°) | 360 |

| Exposure time per image (s) | 1.0 |

| Space group | P61 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 44.47, 44.47, 87.65 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 120 |

| Mosaicity (°) | 0.266 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50–1.64 (1.68–1.64) |

| Total No. of reflections | 279441 (14163) |

| No. of unique reflections | 12127 (873) |

| Completeness (%) | 100.0 (100.0) |

| Multiplicity | 19.7 (13.9) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 20.3 (1.73)† |

| R meas | 0.136 (2.37) |

| CC1/2 | 0.999 (0.511) |

| Overall B factor from Wilson plot (Å2) | 36.0 |

Diffraction images were processed to 1.64 Å resolution, where CC1/2 reaches 0.511. The resolution at which I/σ(I) falls below 2.0 is 1.65 Å.

2.4. Structure solution and refinement

The structure of DIX-Y27W was solved by the molecular-replacement method using the reported structure of the Dvl2-DIX Y27D mutant (DIX-Y27D; PDB entry 4wip; Madrzak et al., 2015 ▸) as a template. The individual atomic coordinates, temperature factors and TLS parameters were refined by PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010 ▸) and model building was performed with Coot (Emsley et al., 2010 ▸). In the structures, water molecules were added automatically in Coot before being checked manually and refined. The resulting structure-refinement data are provided in Table 4 ▸. The atomic coordinates and structure factors were deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession code 6iw3. Figs. 2, 3 and 4 were prepared using PyMOL (Schrödinger).

Table 4. Structure refinement.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| Resolution range (Å) | 38.512–1.636 (1.702–1.636) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.88 (99.67) |

| σ Cutoff | 0.0 |

| No. of reflections, working set | 12118 (1204) |

| No. of reflections, test set | 1216 (135) |

| Final R cryst | 0.2026 (0.3174) |

| Final R free | 0.2292 (0.3308) |

| Cruickshank DPI | 0.116 |

| No. of non-H atoms | |

| Protein | 661 |

| Water | 59 |

| Total | 720 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bonds (Å) | 0.006 |

| Angles (°) | 1.11 |

| Average B factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 36.26 |

| Water | 43.99 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Favoured regions (%) | 98.73 |

| Additionally allowed (%) | 1.27 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.00 |

3. Results and discussion

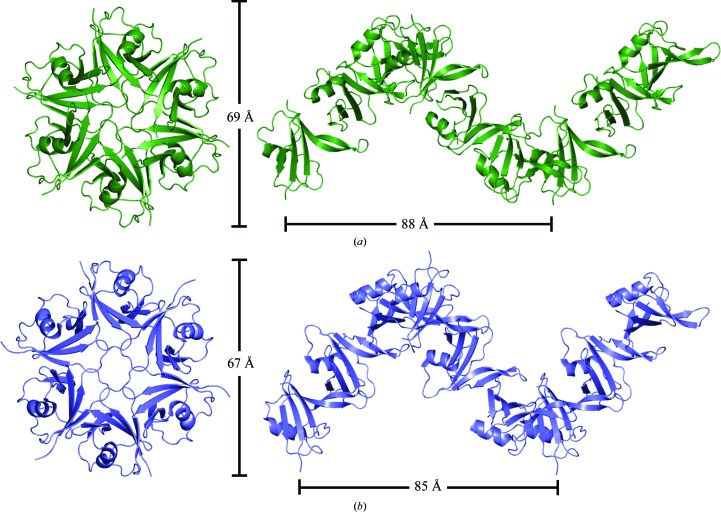

The structure of DIX-Y27W was determined and refined at a resolution of 1.64 Å, with an R work of 20.0% and an R free of 22.9% (Table 4 ▸). One molecule in an asymmetric unit (hexagonal space group P61) formed a helical polymer in a head-to-tail manner with six molecules per turn, each monomer of which was related by the crystallographic 61 axis (Fig. 2 ▸ a). This helical arrangement with a pitch of 87.7 Å and a width of ∼69 Å is consistent with the reported structure of DIX-Y27D (Fig. 2 ▸ b; 85.2 Å in pitch and ∼67 Å in width; Madrzak et al., 2015 ▸).

Figure 2.

Helical arrangement of DIX-Y27W (this work; deep green) (a) and DIX-Y27D (PDB entry 4wip; slate blue) (b). Six and nine consecutive molecules are shown from the top (left) and side (right) views for each polymer, respectively.

To date, all crystal structures of DIX domains have displayed similar right-handed helical polymers in their crystals: those from Axin (rat/wild type, PDB entry 1wsp; rat/R767E mutant, PDB entry 2d5g; Schwarz-Romond et al., 2007 ▸), Dvl1 (mouse/Y17D mutant, PDB entry 3pz8; Liu et al., 2011 ▸), Dvl2 (human/Y27D mutant, PDB entry 4wip; Madrzak et al., 2015 ▸) and Ccd1 (human/wild type, PDB entry 3pz7; mouse/wild type, PDB entry 5y3b; zebrafish/wild type, PDB entry 5y3c; Liu et al., 2011 ▸; Terawaki et al., 2017 ▸). Also, dynamic and reversible polymerization of DIX domains has been observed by SEC analysis, analytical centrifugation and multi-angle light scattering (Schwarz-Romond et al., 2007 ▸; Fiedler et al., 2011 ▸; Liu et al., 2011 ▸). These lines of evidence suggest that their polymerization in a helical arrangement is an inherent characteristic.

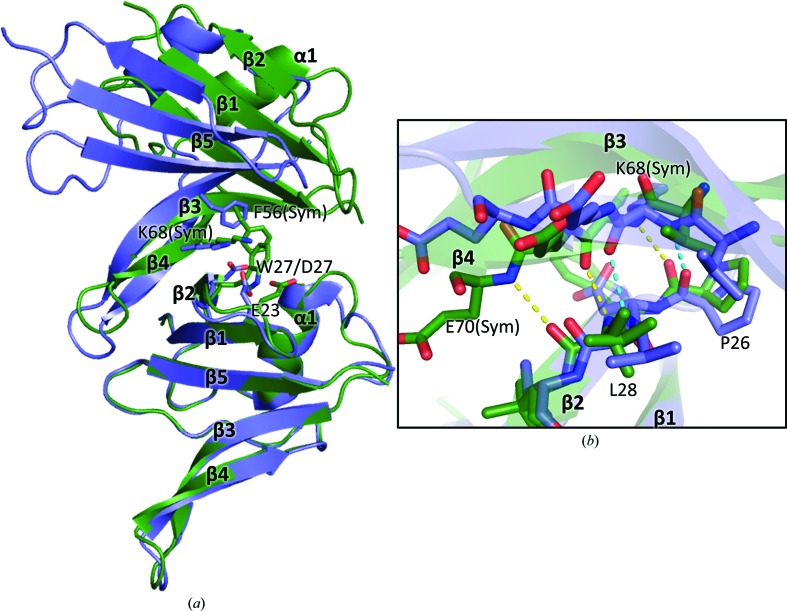

The overall structure of DIX-Y27W exhibits a ubiquitin fold with five β-strands (β1–β5) and one α-helix (Fig. 1 ▸), essentially similar to that of DIX-Y27D (chains A–C), with an overall r.m.s.d. of 0.467–0.639 Å for Cα atoms (Fig. 3 ▸ a). β2 of the DIX-Y27W head surface forms a parallel intermolecular β-bridge with β4 of the adjacent molecule, similar to the other reported structures of DIX domains, including DIX-Y27D (Schwarz-Romond et al., 2007 ▸; Liu et al., 2011 ▸; Madrzak et al., 2015 ▸; Terawaki et al., 2017 ▸). Pro26 and Leu28 on the head surface form an intermolecular β-bridge with Lys68 and Glu70 of the tail surface of the neighbouring molecule (Fig. 3 ▸ b).

Figure 3.

Comparison of DIX-Y27W and DIX-Y27D. (a) Superposition of two adjacent molecules of DIX-Y27W (related by crystallographic symmetry; deep green) and DIX-Y27D [chains B (upper model) and C (lower model); slate blue] in their helical polymers. The lower molecule of DIX-Y27W is superimposed onto chain C (lower model) of DIX-Y27D. The residues involved in important interactions through their side chains are shown. The residues of the upper monomers are labelled with ‘(Sym)’. (b) Close-up view of the intermolecular β-bridge. Pro26–Val29 of the lower monomer and Val67–Glu70 of the upper monomer are displayed as stick models. The hydrogen bonds in DIX-Y27W and DIX-Y27D are shown as yellow and cyan dotted lines, respectively. The side chain of Leu28 in DIX-Y27W has a double conformation, judged from its electron density (not shown).

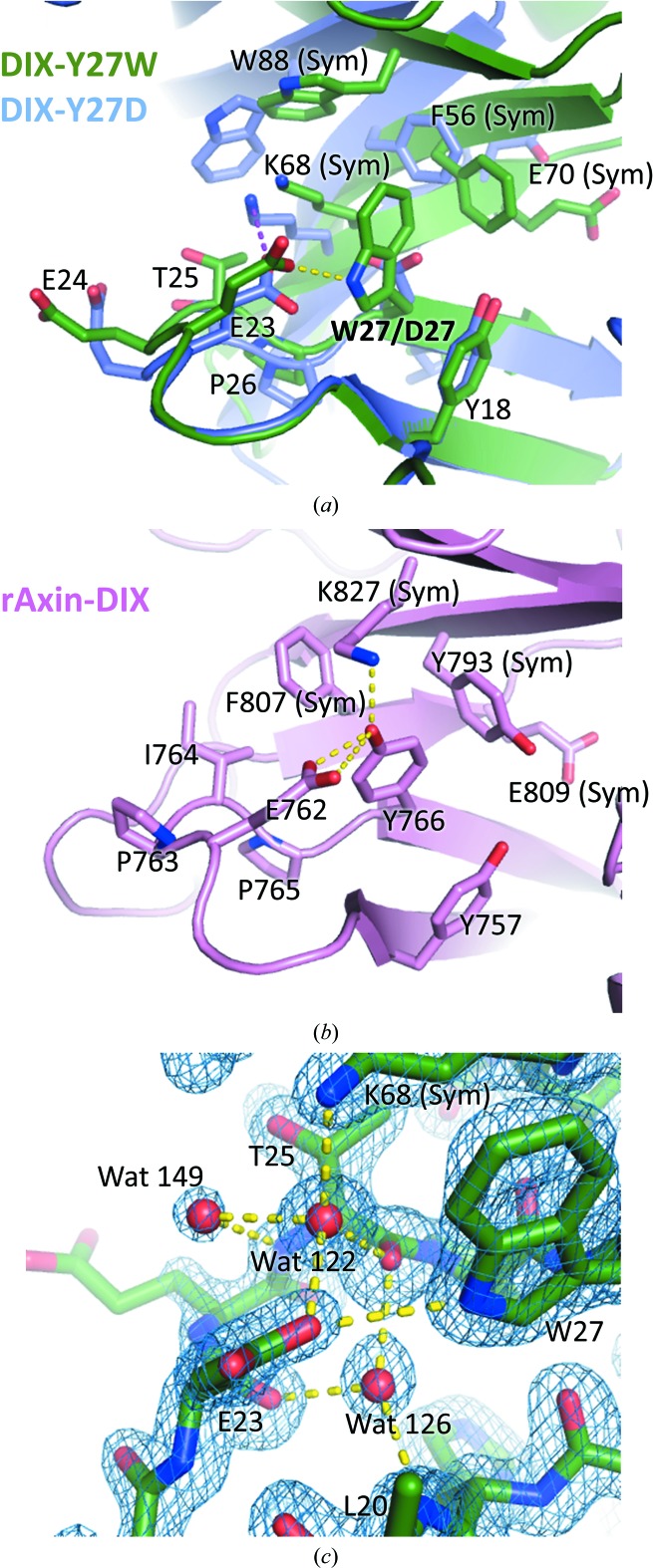

Trp27 on the head surface is the central residue of the hydrophobic cluster and is almost surrounded by Tyr18 and Glu23 of the same molecule and Phe56, Lys68 and Trp88 on the tail surface of the adjacent molecule (Figs. 3 ▸ a and 4 ▸ a). Lysine is a polar hydrophilic amino acid, but it can form cation–π interactions (Ma & Dougherty, 1997 ▸) using its amino group as well as hydrophobic interactions with aromatic amino-acid residues through its methylene chain. Indeed, Lys68 of the neighbouring molecule contacts Trp27, forming both cation–π and hydrophobic interactions. The hydrophobic character of the DIX–DIX interface indicates that head-to-tail DIX–DIX self-association is basically driven by hydrophobic interactions. This is consistent with the fact that polymerization-blocking mutations (Y27D and V67A/K68A) of Dvl2-DIX (Schwarz-Romond et al., 2007 ▸) tend to reduce the hydrophobicity of the residue or induce a loss of hydrophobic and cation–π interactions.

Figure 4.

Close-up view of head-to-tail DIX–DIX interactions. (a) DIX-Y27W (two crystallographic symmetry-related molecules; deep green) superimposed on DIX-Y27D [chains B (upper model) and C (lower model); slate blue]. The Glu23–Trp27 hydrogen bond in DIX-Y27W and the Glu23 (chain C)–Lys68 (chain B) salt bridge in DIX-Y27D are shown as yellow and magenta dotted lines, respectively. (b) rAxin-DIX (PDB entry 1wsp; two crystallographic symmetry-related molecules of chain A). (c) 2F o − F c electron-density map and stick models of DIX-Y27W around Glu23 and Trp27 contoured at 1.5σ. Water molecules involved in the hydrogen-bond network of the DIX–DIX interface are shown.

Trp27 also displayed a hydrophilic interaction with a neighbouring residue. The NE1 atom of Trp27 forms a hydrogen bond to the side chain of Glu23 in the same molecule (Fig. 4 ▸ a). In the case of DIX-Y27D, Glu23 is ∼4.5 Å away from Asp27 and therefore does not form a hydrogen bond to it. Glu23 of DIX-Y27W has a rotamer close to mt-10° (Lovell et al., 2000 ▸) to form a hydrogen bond with Trp27 while avoiding steric hindrance against its neighbouring residues, whereas that of DIX-Y27D showed a rotamer close to tt0° in chains A and C (pt-20° in chain B) to form a salt bridge with Lys68 of the adjacent molecule (Fig. 4 ▸ a). The rat Axin DIX domain (rAxin-DIX) conserves a similar hydrogen bond, Glu762–Tyr766, corresponding to the Glu23–Trp27 interaction of DIX-Y27W. The rotamer of Glu762 is close to mt-10°, similar to that of Glu23 in DIX-Y27W. Tyr766 of rAxin-DIX, which corresponds to Tyr27 of Dvl2 (Fig. 1 ▸ a), forms a hydrogen bond to Lys827 of the adjacent molecule (Fig. 4 ▸ b). Lys827 of rAxin is not conserved in Dvl2 (corresponding to Trp88), but Lys68 of DIX-Y27W is close to Trp27 and is likely to play a similar role in Dvl2-DIX.

The solvent structures in the self-association interface were unclear in the reported structures of Dvl-DIX owing to the relatively low resolution [2.85 and 2.69 Å for Dvl1-DIX (Y17D) and DIX-Y27D, respectively; Liu et al., 2011 ▸; Madrzak et al., 2015 ▸]: only 1–9 water molecules per chain in Dvl1-DIX (Y17D) and three or five water molecules per chain in DIX-Y27D. The present high-resolution structure of DIX-Y27W provides a detailed water structure, especially in the DIX–DIX interface (Fig. 4 ▸ c). We could assign 59 water molecules per chain, including 14 molecules within the DIX–DIX interface, in DIX-Y27W (Table 4 ▸). Only one water molecule (Wat122) is clearly involved in the DIX–DIX interface (Fig. 4 ▸ c). Wat122 bridges the following atoms: Glu23 OE1 (2.71 Å), Thr25 O (2.82 Å) and Lys68 NZ (adjacent molecule; 2.80 Å). Two other water molecules (Wat126 and Wat 149) were observed close to Wat122, but they do not bridge the two adjacent DIX-Y27W molecules. Wat126 bridges between the Leu20 N (2.93 Å), Glu23 O (2.82 Å) and Thr25 O (2.78 Å) atoms, and Wat149 forms hydrogen bonds to Wat122 (2.91 Å) and the Thr25 N (3.17 Å) atom. These water molecules were unobserved in DIX-Y27D, probably owing to the different conformation of Glu23, which is likely to cause steric repulsion or loss of the hydrogen bonds involving this residue, or owing to the relatively low resolution (2.69 Å).

In summary, we have determined the X-ray structure of DIX-Y27W at 1.64 Å resolution. The present structure illustrates a wild-type-like DIX–DIX self-associating interface, including the hydrogen-bond, hydrophobic and cation–π interactions, and a detailed water structure, which are likely to be conserved in wild-type Dvl2, although it carries a mutation on the head surface of the molecule.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: Dishevelled2 DIX domain, Y27W mutant, 6iw3

Acknowledgments

The synchrotron-radiation experiments were performed at SPring-8 with the approval of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (Proposal Nos. 2014A1035 and 2017A2538) and under the Cooperative Research Program of the Institute for Protein Research, Osaka University (2017A6723 and 2017B6723) and at Photon Factory (2015R-66 and 2017G012) under the Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Platform for Drug Discovery, Informatics and Structural Life Science) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) and Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED).

Funding Statement

This work was funded by Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology grants 23121526, 25121731, 23121527, and 25121705. Hyogo Science and Technology Association grant .

References

- Adams, P. D., Afonine, P. V., Bunkóczi, G., Chen, V. B., Davis, I. W., Echols, N., Headd, J. J., Hung, L.-W., Kapral, G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., McCoy, A. J., Moriarty, N. W., Oeffner, R., Read, R. J., Richardson, D. C., Richardson, J. S., Terwilliger, T. C. & Zwart, P. H. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bienz, M. (2014). Trends Biochem. Sci. 39, 487–495. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Clevers, H. & Nusse, R. (2012). Cell, 149, 1192–1205. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fiedler, M., Mendoza-Topaz, C., Rutherford, T. J., Mieszczanek, J. & Bienz, M. (2011). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 1937–1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gammons, M. V., Renko, M., Johnson, C. M., Rutherford, T. J. & Bienz, M. (2016). Mol. Cell, 64, 92–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gammons, M. V., Rutherford, T. J., Steinhart, Z., Angers, S. & Bienz, M. (2016). J. Cell Sci. 129, 3892–3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kabsch, W. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-T., Dan, Q.-J., Wang, J., Feng, Y., Chen, L., Liang, J., Li, Q., Lin, S.-C., Wang, Z.-X. & Wu, J.-W. (2011). J. Biol. Chem. 286, 8597–8608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lovell, S. C., Word, J. M., Richardson, J. S. & Richardson, D. C. (2000). Proteins, 40, 389–408. [PubMed]

- Ma, J. C. & Dougherty, D. A. (1997). Chem. Rev. 97, 1303–1324. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Madrzak, J., Fiedler, M., Johnson, C. M., Ewan, R., Knebel, A., Bienz, M. & Chin, J. W. (2015). Nature Commun. 6, 6718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nusse, R. & Clevers, H. (2017). Cell, 169, 985–999. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ochman, H., Gerber, A. S. & Hartl, D. L. (1988). Genetics, 120, 621–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schwarz-Romond, T., Fiedler, M., Shibata, N., Butler, P. J., Kikuchi, A., Higuchi, Y. & Bienz, M. (2007). Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 484–492. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sievers, F., Wilm, A., Dineen, D., Gibson, T. J., Karplus, K., Li, W., Lopez, R., McWilliam, H., Remmert, M., Söding, J., Thompson, J. D. & Higgins, D. G. (2011). Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tauriello, D. V., Jordens, I., Kirchner, K., Slootstra, J. W., Kruitwagen, T., Bouwman, B. A., Noutsou, M., Rudiger, S. G., Schwamborn, K., Schambony, A. & Maurice, M. M. (2012). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 109, E812–E820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Terawaki, S., Fujita, S., Katsutani, T., Shiomi, K., Keino-Masu, K., Masu, M., Wakamatsu, K., Shibata, N. & Higuchi, Y. (2017). Sci. Rep. 7, 7739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wong, H.-C., Bourdelas, A., Krauss, A., Lee, H.-J., Shao, Y., Wu, D., Mlodzik, M., Shi, D.-L. & Zheng, J. (2003). Mol. Cell, 12, 1251–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y., Appleton, B. A., Wiesmann, C., Lau, T., Costa, M., Hannoush, R. N. & Sidhu, S. S. (2009). Nature Chem. Biol. 5, 217–219. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: Dishevelled2 DIX domain, Y27W mutant, 6iw3