Abstract

Background

Tripartite motif containing 55 (TRIM55) plays a regulatory role in assembly of sarcomeres, but few studies have assessed its function in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Matreial/Methods

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was used to detect expression of TRIM55 in tissues samples of HCC patients. Transwell assay was used to study migration and invasion ability of HCC cells. Western blot and immunofluorescence (IF) were used to analyze mechanism of TRIM55 in cell migration and invasion.

Results

We found TRIM55 was downregulated in HCC tissues and was associated with prognosis of HCC patients. Cox regression analysis showed that TRIM55 was an independent risk factor of prognosis of HCC patients. Overexpression of TRIM55 was associated with lower cell migration and invasion ability, and it led to high expression of E-cadherin and low expression of Vimentin and MMP2.

Conclusions

Our study found TRIM55 is an independent factor affecting the prognosis of HCC patients, and overexpression of TRIM55 inhibits migration and invasion of HCC cells through epithelial-mesenchymal transition and MMP2.

MeSH Keywords: Carcinoma, Hepatocellular; Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition; Matrix Metalloproteinase 2; Protein Multimerization

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a common digestive system tumor which has high morbidity and mortality rates [1]. Current treatments, including surgical resection, liver transplantation, and local ablation, are effective for early-stage HCC patients. However, patients with advanced HCC have early occurrence and poor prognosis, even when receiving the above treatments [2]. Thus, more predictive biomarkers are needed to improve postoperative outcomes in liver cancer patients.

TRIM55, also known as muscle-specific RING finger 2 (Murf 2), has been demonstrated to have an important role in muscle development and cardiac function. Perera et al. found that TRIM55 plays a crucial role in the earliest stages of skeletal muscle differentiation and myofibrillogenesis [3,4]. Another study showed that the alternative splicing of TRIM55 was regulated by miR-30-5p during muscle differentiation [5]. In addition, a recent study demonstrated that TRIM55 regulates the inflammatory response in SARS-CoV infection [6].

However, the function of TRIM55 in progression of solid cancers is unclear. In this study, we investigated the relationship between expression of TRIM55 and prognosis of HCC patients and the function of TRIM55 on migration and invasion of HCC cells.

Material and Methods

Patients, tissue samples, and follow-up

All the tissue samples (including HCC tissues and adjacent non-tumor tissues) in this study were selected from 100 HCC patients who underwent surgery at Peking University People’s Hospital. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Peking University People’s Hospital, and all the selected patients gave written informed consent. Clinicopathologic data, including age, sex, size of tumor, number of tumors, vessel invasion, TNM stage, and tumor grade, were collected. The follow-up was started i months after the operation, and continued until the termination date (May 31, 2017) or death.

Cell culture

HCC cell lines HCC-LM3 and Huh7 were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Cell Bank (Shanghai, China). All these cells were maintained in MEM medium, supplemented with 10% FBS at 37ºC in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Construction of TRIM55 overexpression in HCC cell line

The cDNA clone of TRIM55 was obtained from Origene (Cat. No. RG214960), then we constructed the transient overexpression of TRIM55 in Huh7 and HCC-LM3 cell lines according to the product manual. The efficiency of transfection was verified by Western blot and RT-PCR.

Immunohistochemistry

The 100 paired paraffin-embedded caner tissues and neighboring tissues of HCC patients were cut into 3-um slices, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated in a series of graded alcohol dilutions. Then, we used heat epitope retrieval for 20 min in a citrate salt solution. After exposure to 5% BSA for 30 min, all tissues were incubated with rabbit antibody to human TRIM55 antibody (Novus, NBP2-33691, dilution 1/200) overnight at 4°C. Slides were then incubated with HRP at room temperature for 30 min and visualized using DAB as chromogen for 5–10 min. The immunohistochemistry scores were given by 2 independent pathologists.

Total RNA extraction and RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted by Trizol reagent and reverse transcription was conducted by using Superscript III RT (Invitrogen) and random primers. Real-time PCR was performed with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied TaKaRa, Otsu, Shiga, Japan). The nucleotide sequences of the primers were as follows: GAPDH, 5′-ATGGGGAAGGTGAAGGTCG-3′ and 5′-GGGGTCATTGATGGCAACAATA-3′; TRIM55, 5′-GGTTTT GGATAGACATGGGGT-3′, and 5′-TTCTCCTCTTGGGTTCGGGT-3′. The results were analyzed by 2−ΔΔCT method with GAPDH as the internal control. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

Western blot analysis

Total proteins in HCC cells were extracted by lysis buffer, and the protein concentration was measured by Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. The SDS-PAGE was conducted according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After transfer to a PVDF membrane, membranes were incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight in a buffer containing 5% skim milk. The primary antibodies were as follows: TRIM55 (Novus, NBP2-33691, dilution 1/1000), E-cadherin and Vimentin (Cell Signaling Technology, (EMT) Antibody Sampler Kit #9782, dilution 1/1000), and MMP2 (Proteintech, 10373-2-AP, dilution 1/1000), and the internal control was GAPDH (Abcam Biotechnology, Cambridge, UK, dilution 1/1000). Then incubated secondary antibody at 37°C for 30 min. The proteins were detected by an Odyssey fluorescence scanner (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE).

Cell migration and invasion assay

Basement membrane invasion and migration assays were conducted using Transwell plates (Corning, NY). Huh7 and HCC-LM3 cells transfected with TRIM55 ORF or control vectors were trypsinized and collected. Cells were cultured with serum-free MEM with matrigel (invasion assay) or without matrigel (migration assay) for 48 h (invasion) or 24 h (migration). In the lower compartment, medium was changed with MEM complete medium. After fixation and staining, cells that invaded across the membranes on the bottom surface were counted and photographed. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ±standard deviation (SD). For comparisons, the t test, paired-samples t test, and Fisher’s exact test were performed, as appropriate. Cumulative recurrence and survival probabilities were evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method and Cox regression analysis, and differences were assessed using the log-rank test. P<0.05 was set as the level of significance.

Results

TRIM55 was downregulated in HCC tissues and is associated with clinicopathologic features of HCC patients

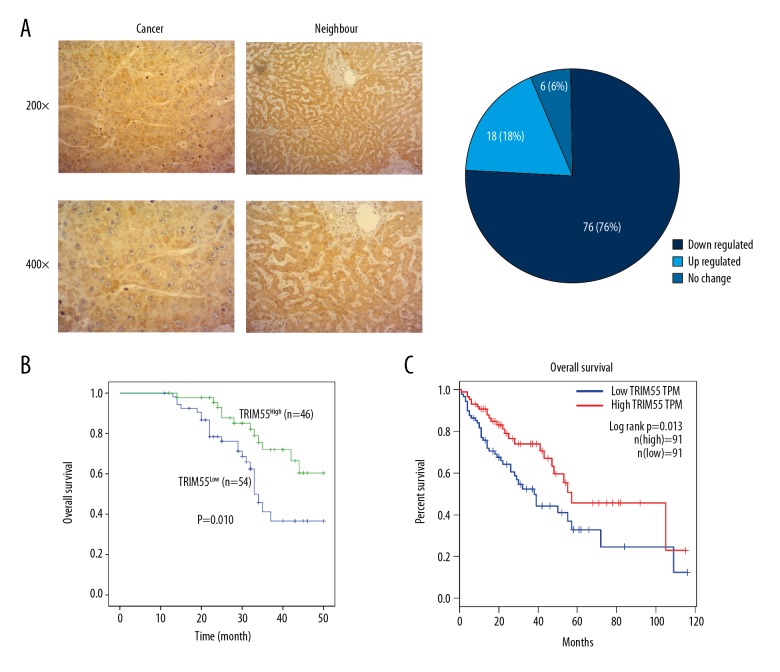

To investigate whether expression of TRIM55 was significantly changed during progression of HCC, we detected TRIM55 expression in 100 pairs of HCC tissues and neighboring tissues by immunohistochemistry. By using the 13-point score analysis of IHC, we found that the expression of TRIM55 in HCC tissues (76%, 76/100) was frequently lower than in neighboring tissues (Figure 1A). Then, we used single-factor analysis to investigate the relationship between TRIM55 expression and clinicopathologic features of HCC patients. The results showed that expression of TRIM55 was significantly associated with vessel invasion, tumor grade, and TNM stage (Table 1). Thus, we proved that TRIM55 was reduced in HCC tissues, and lower expression of TRIM55 was associated with vessel invasion, tumor stage, and tumor grade.

Figure 1.

TRIM55 is downregulated in HCC tissues and is associated with prognosis of HCC patients. (A) IHC detected expression of TRIM55 in HCC tissues and neighboring tissues. Representative photos at 200× and 400×. The level of TRIM55 expression between HCC tissues and neighbor tissues was analyzed and shown as a pie chart. (B, C) the relationship between overall survival and TRIM55 expression was analyzed by Kaplan-Meier analysis, and the follow-up data were collected by ourselves (B) or TCGA database (C).

Table 1.

Relationship between TRIM55 expression and clinicopathologic features.

| Variables | All patients (N=100) | TRIM55 expression | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low* | High* | |||

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤55 | 47 | 25 | 22 | 0.879 |

| >55 | 53 | 29 | 24 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 61 | 34 | 27 | 0.663 |

| Female | 39 | 20 | 19 | |

| Size of tumor (cm) | ||||

| ≤5 | 59 | 28 | 31 | 0.115 |

| >5 | 41 | 26 | 15 | |

| Number of tumor | ||||

| Single | 47 | 23 | 24 | 0.339 |

| Multiple | 53 | 31 | 22 | |

| Vessel invasion | ||||

| Negative | 56 | 24 | 32 | 0.012 |

| Positive | 44 | 30 | 14 | |

| Grade | ||||

| Well + moderate | 45 | 19 | 26 | 0.033 |

| Poor | 55 | 35 | 20 | |

| TNM stage | ||||

| I–II | 54 | 20 | 34 | 0.009 |

| III–IV | 46 | 30 | 16 | |

High*means IHC score ≥6 Low* means IHC score <6. For analysis of correlation between TRIM55 expression and clinical features, chi-square tests were used. Results were considered statistically significant at P<0.05.

TRIM55 was an independent risk factor of HCC patients

To investigate the relationship between TRIM55 expression and prognosis of HCC patients, we divided these 100 cases into a TRIM55high group and a TRIM55low group. Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that patients with low expression of TRIM55 always had a worse prognosis than those with high expression of TRIM55 (p=0.010) (Figure 1B). Cox regression analysis showed that TRIM55 was an independent risk factor of HCC patients (HR=0.425, 95%CI=(0.193–0.934), p=0.033) (Table 2). To further verify our findings, we analyzed the relationship between TRIM55 expression and prognosis of HCC patients by TCGA database, and the result was consistent with our previous results (Figure 1C). We found that TRIM55 expression is an independent risk factor of HCC patients, and TRIM55 can act as a tumor-suppressor gene during progression of HCC.

Table 2.

TRIM55 expression is an independent predictive factor for overall survival time in HCC patients.

| P value | HR* | 95.0% CI for HR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| TRIM55 (high vs. low) | .033 | .425 | .193 | .934 |

| Age (≤55 vs. >55) | .068 | .469 | .208 | 1.057 |

| Gender (Male vs. Female) | .016 | 3.266 | 1.246 | 8.560 |

| Tumor number (single vs. multiple) | .033 | .344 | .128 | .919 |

| Tumor size (≤5 cm vs. >5 cm) | .725 | .814 | .258 | 2.567 |

| Vessel invasion (negative vs. positive) | .363 | .659 | .269 | 1.616 |

| TNM stage (I–II vs. III–IV) | .285 | 2.101 | .539 | 8.187 |

| Grade (well + moderate vs. poor) | .621 | .831 | .399 | 1.731 |

HR – hazard ratio; 95% CI – 95% confidence interval.

TRIM55 overexpression HCC cell lines were constructed

To investigate the function of TRIM55 in progression of HCC cells, we used the ORF transfect system to overexpress TRIM55 in Huh7 and HCC-LM3 cell lines. Then, we used Western blot and RT-PCR to verify the transfection efficiency in Huh7 and HCC-LM3 cell lines. The results showed that both protein and mRNA levels of TRIM55 were overexpressed by the TRIM55 ORF transfection system (Figure 2A, 2B).

Figure 2.

TRIM55 overexpression in HCC cell lines was constructed. (A) Western blot was used to verify transfection efficiency at the protein level. GAPDH was used as internal control. (B) RT-PCR was used to verify transfection efficiency at the mRNA level, *** p<0.0001.

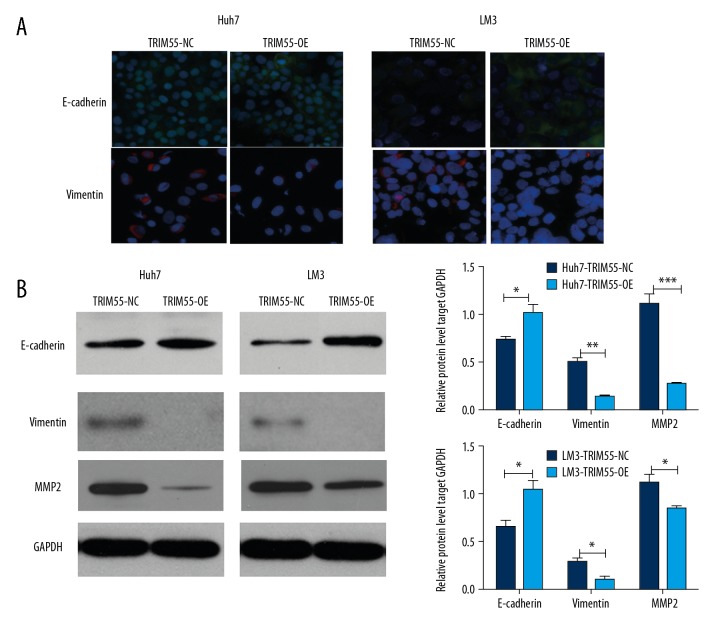

Overexpression of TRIM55 decreases migration and invasion of HCC cells via EMT and MMP2

Because expression of TRIM55 was associated with vessel invasion in HCC patients, we hypothesized that TRIM55 plays vital role in cell migration and invasion. The results of Transwell assay showed that the cell migration and invasion ability of HCC cell lines were significantly decreased after overexpression of TRIM55 (Figure 3A, 3B). Because the EMT process and matrix metalloproteinase family proteins were found to be important for cell migration and invasion, we assessed the expression of related proteins by IF and Western blot, and the results showed that expression of E-cadherin was increased while expressions of Vimentin and MMP2 were decreased under the condition of TRIM55 overexpression (Figure 4A, 4B).

Figure 3.

Overexpression of TRIM55 inhibits migration and invasion of HCC cells. (A, B) Cell migration and invasion ability were detected by Transwell assay in HCC cells with TRIM55 overexpression and negative control. All experiments were repeated 3 times. *** p<0.0001

Figure 4.

Overexpression of TRIM55 inhibits migration and invasion of HCC cells through EMT and MMP2. (A) IF was used to detect expression of E-cadherin and Vimentin in HCC cells with TRIM55 overexpression and negative control. (B) Western blot was used to detect expression of E-cadherin, Vimentin, and MMP2 in HCC cells with TRIM55 overexpression and negative control. GAPDH was used as internal control.

Discussion

Currently, the main treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are surgical removal of tumors and liver transplantation. However, postoperative recurrence and metastasis are common complications and there is no effective method to solve this problem [7,8]. Thus, more studies are needed to investigate predictive biomarkers to prevent HCC recurrence and metastasis.

TRIM55 is known as an important protein in regulating muscle differentiation and myofibrillogenesis, but its function in tumor migration and invasion is unclear. Since the migration of solid tumor cells is based on the synthesis of cytoskeleton and trans-shipment [9], and TRIM55 has an important role in regulating function of skeletal muscle, we hypothesized that TRIM55 plays an important role in metastasis of HCC.

We first detected expression of TRIM55 in 100 paired HCC tissues and adjacent-normal tissues and found TRIM55 was underexpressed in HCC tissues. Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that low expression of TRIM55 was always associated with poor overall survival time, and Cox regression analysis also verified that TRIM55 was an independent predictive factor in HCC patients. To investigate the function of TRIM55 in HCC cells, we analyzed the relationship between expression of TRIM55 and clinicopathologic features, and found that TRIM55 was correlated with tumor vessel invasion. Then, we used Transwell assay to verify this, and the results showed that overexpression of TRIM55 leads to lower migration and invasion ability of HCC cells. Thus, we preliminary demonstrated that TRIM55 is involved in metastasis of HCC cells.

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process reported to be important in cancer metastasis, enhances cancer motility and dissemination through the disruption of intercellular junctions [10]. Thus, to further investigate the molecular mechanism by which TRIM55 regulates migration of HCC cells, we used immunofluorescence and Western blot assay to detect expression change of E-cadherin and Vimentin under the condition of TRIM55 overexpression. As expected, we found the expression of E-cadherin was increased and expression of Vimentin was decreased in HCC cells when TRIM55 was overexpressed. Similarly, as MMP2 was reported to be important for cell invasion through regulating cell matrix degradation [11], and then we found that the expression of MMP2 was significantly decreased after TRIM55 was overexpressed in HCC cells. Therefore, our study found that TRIM55 can regulate migration and invasion of HCC cells through EMT and MMP2 pathway.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that TRIM55 was underexpressed in HCC tissues and was an independent predictive factor in HCC patients. TRIM55 can regulate migration and invasion of HCC cells via EMT and MMP2 pathway. However, our study did not define the molecular mechanism of TRIM55 in EMT and MMP2 regulation, and more studies are needed to investigate the function of TRIM55 on HCC.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients, their families, the investigators, medical staff, and all others who participated in the present study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Finn RS. Current and future treatment strategies for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: Role of mTOR inhibition. Liver Cancer. 2012;1(3–4):247–56. doi: 10.1159/000343839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forner A, Gilabert M, Bruix J, Raoul J-L. Treatment of intermediate – stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(9):525–35. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perera S, Holt MR, Mankoo BS, Gautel M. Developmental regulation of MURF ubiquitin ligases and autophagy proteins nbr1, p62/SQSTM1 and LC3 during cardiac myofibril assembly and turnover. Dev Biol. 2011;351(1):46–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perera S, Mankoo B, Gautel M. Developmental regulation of MURF E3 ubiquitin ligases in skeletal muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2012;33(2):107–22. doi: 10.1007/s10974-012-9288-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang B-W, Cai H-F, Wei X-F, et al. miR-30-5p regulates muscle differentiation and alternative splicing of muscle-related genes by targeting MBNL. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(2) doi: 10.3390/ijms17020182. pii: E182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gralinski LE, Ferris MT, Aylor DL, et al. Genome wide identification of SARS-CoV susceptibility loci using the collaborative cross. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(10):e1005504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahbari NN, Mollberg NM, Müller SA, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Current management and perspectives for the future. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;(253):453–69. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31820d944f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan ST, Poon RT, Yeung C, et al. Continuous improvement of survival outcomes of resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: A 20-year experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;(253):745–58. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182111195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chakrabarti KR, Hessler L, Bhandary L, Martin SS. Molecular pathways: New signaling considerations when targeting cytoskeletal balance to reduce tumor growth. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(23):5209–14. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nieto MA, Huang Ruby Y-J, Jackson RA, Thiery JP. EMT: 2016. Cell. 2016;166(1):21–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stamenkovic I. Extracellular matrix remodelling: The role of matrix metalloproteinases. J Pathol. 2003;200(4):448–64. doi: 10.1002/path.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]