Abstract

Background

Recognition is growing that social anxiety disorder (SAnD) is a chronic and disabling disorder, and data from early trials demonstrate that medication may be effective in its treatment. This systematic review is an update of an earlier review of pharmacotherapy of SAnD.

Objectives

To assess the effects of pharmacotherapy for social anxiety disorder in adults and identify which factors (methodological or clinical) predict response to treatment.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (CCMDCTR‐Studies and CCMDCTR‐References) to 17 August 2015. The CCMDCTR contains reports of relevant RCTs from MEDLINE (1950‐), Embase (1974‐), PsycINFO (1967‐) and CENTRAL (all years). We scanned the reference lists of articles for additional studies. We updated the search in August 2017 and placed additional studies in Awaiting Classification, these will be incorporated in the next version of the review, as appropriate.

Selection criteria

We restricted studies to randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of pharmacotherapy versus placebo in the treatment of SAnD in adults.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors (TW and JI) assessed trials for eligibility and inclusion for this review update. We extracted descriptive, methodological and outcome information from each trial, contacting investigators for missing information where necessary. We calculated summary statistics for continuous and dichotomous variables (if provided) and undertook subgroup and sensitivity analyses.

Main results

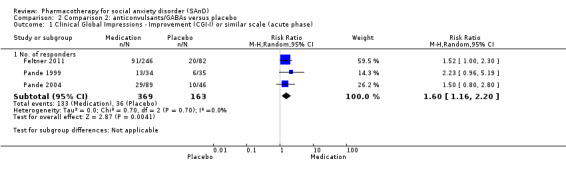

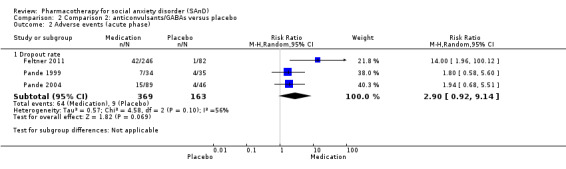

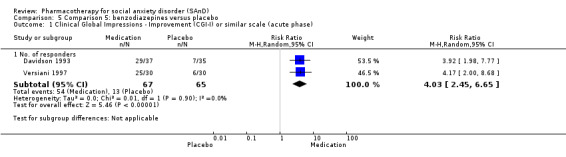

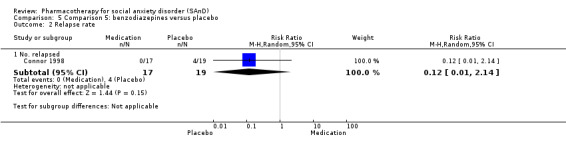

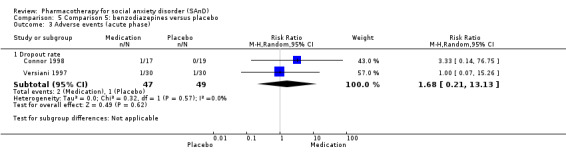

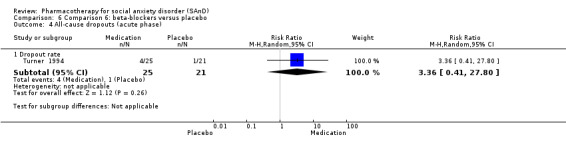

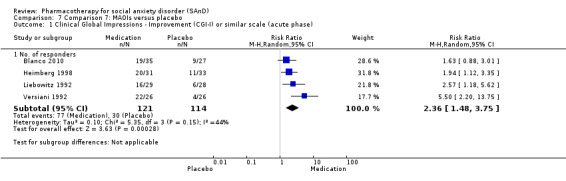

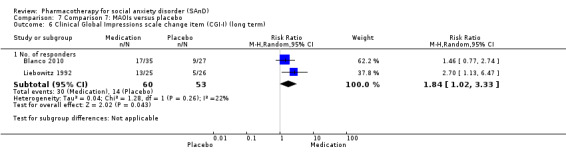

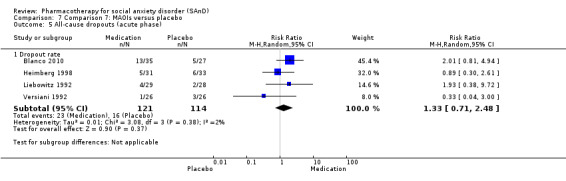

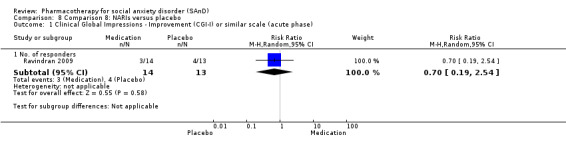

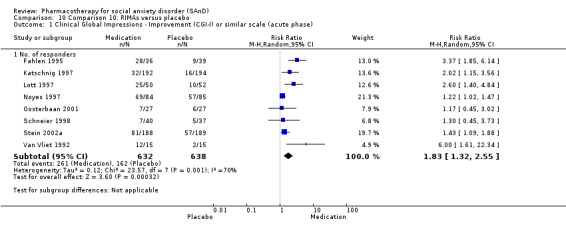

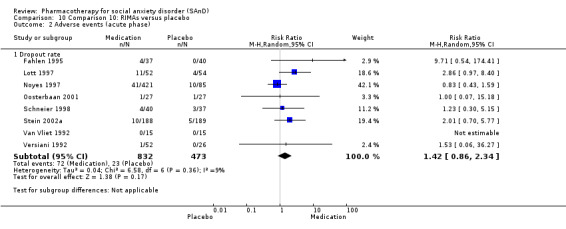

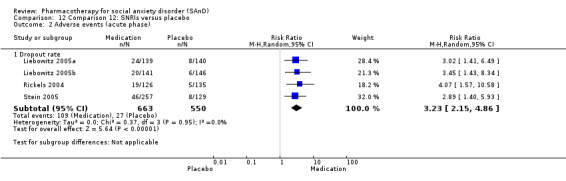

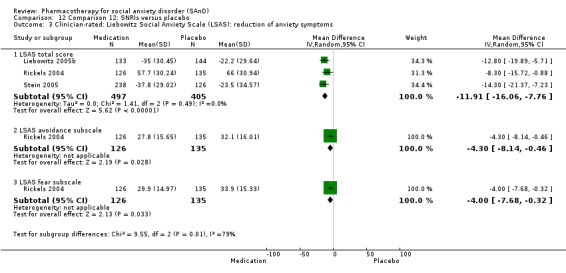

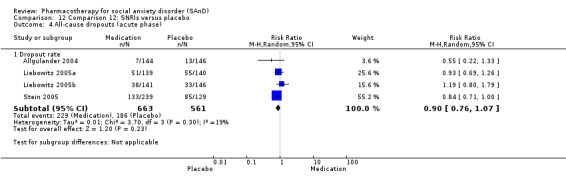

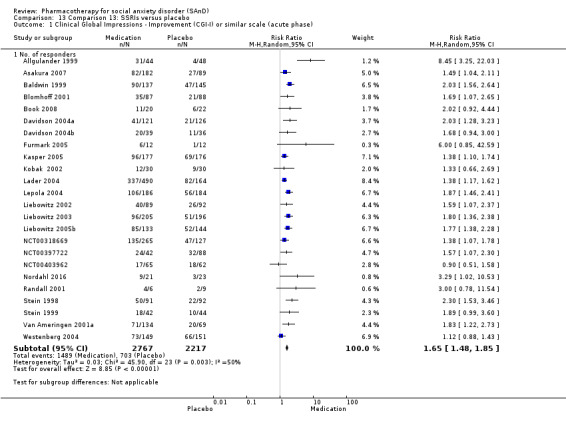

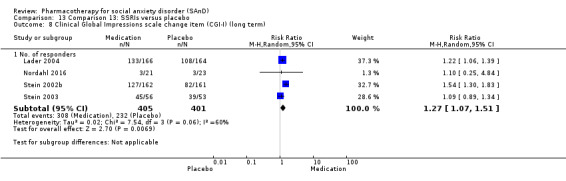

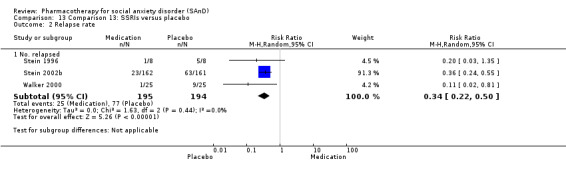

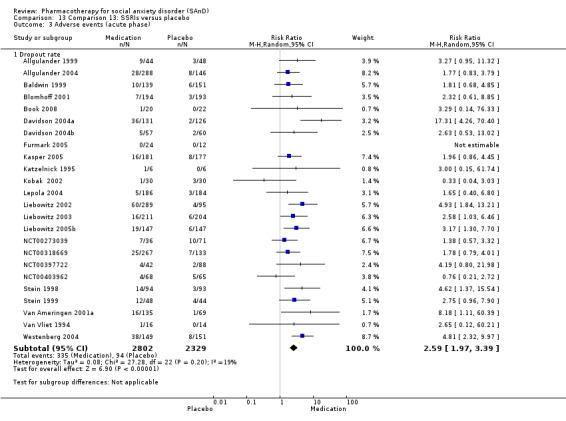

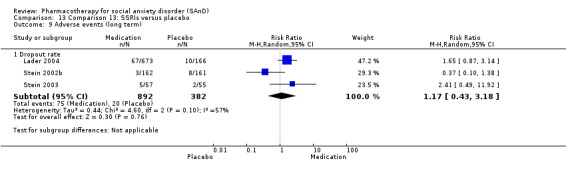

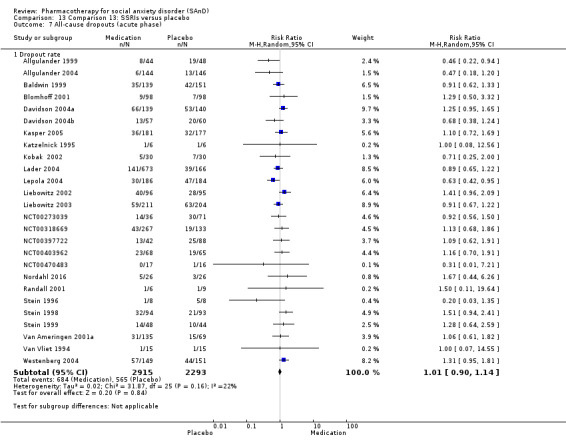

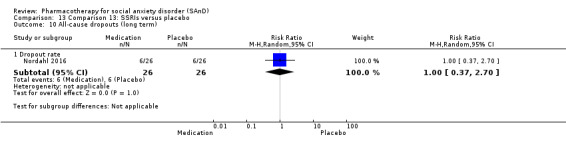

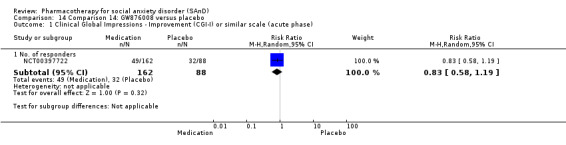

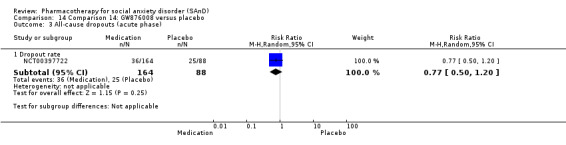

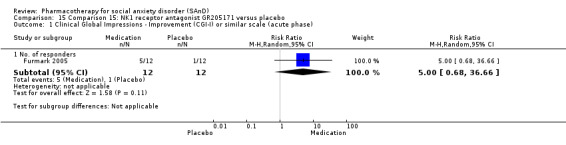

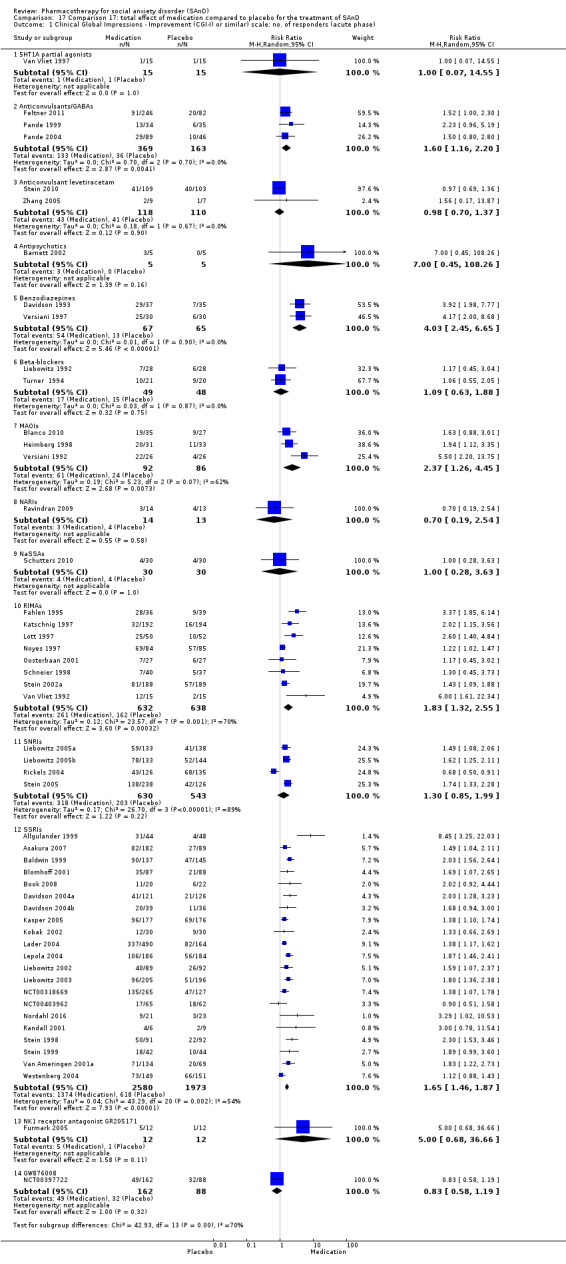

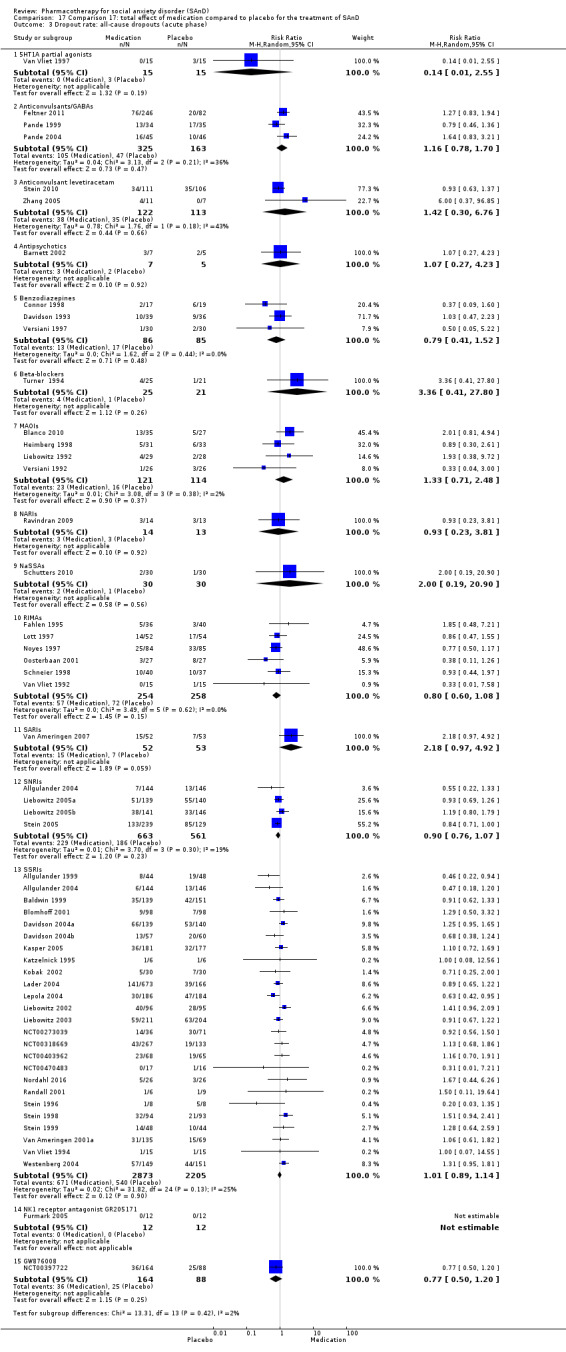

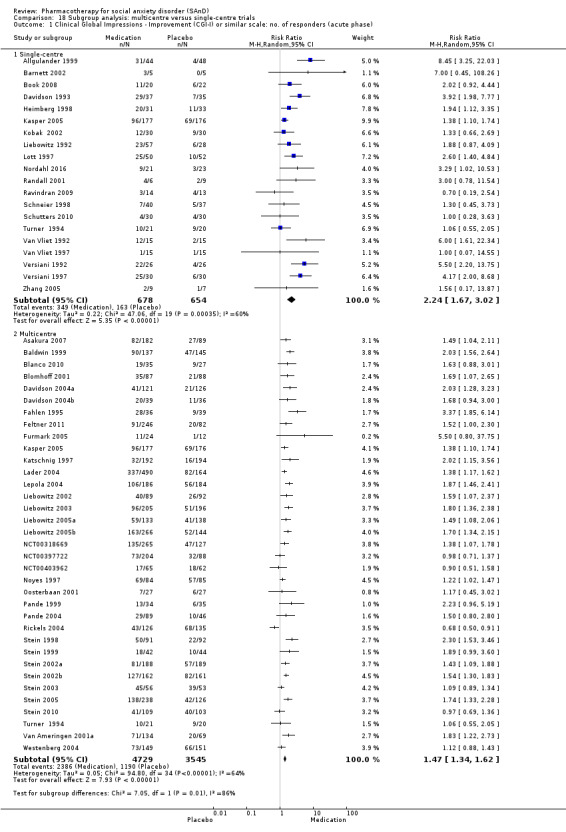

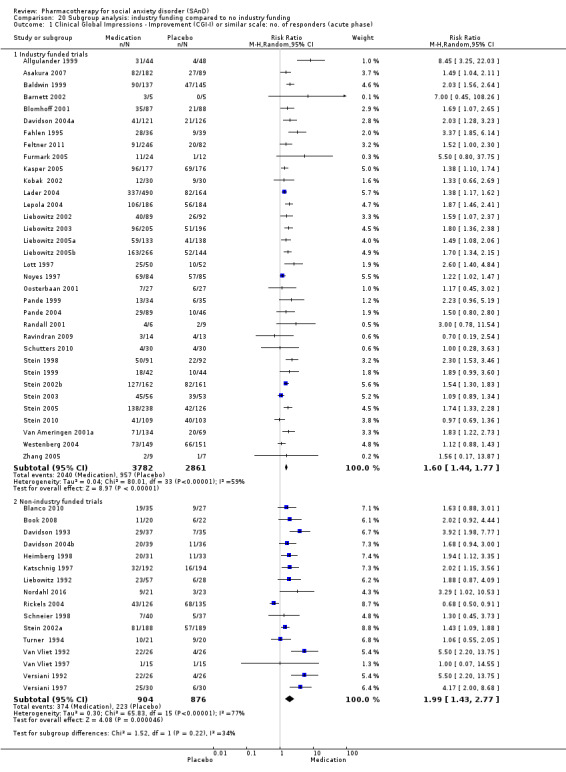

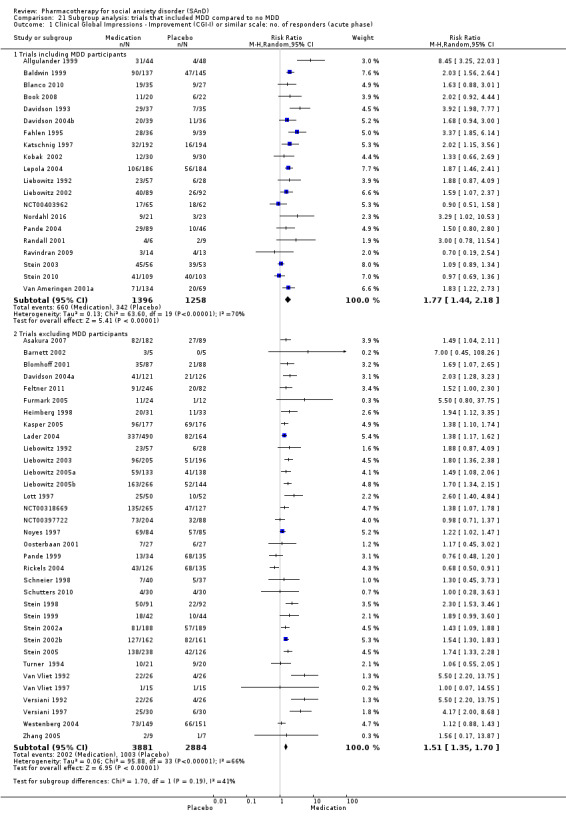

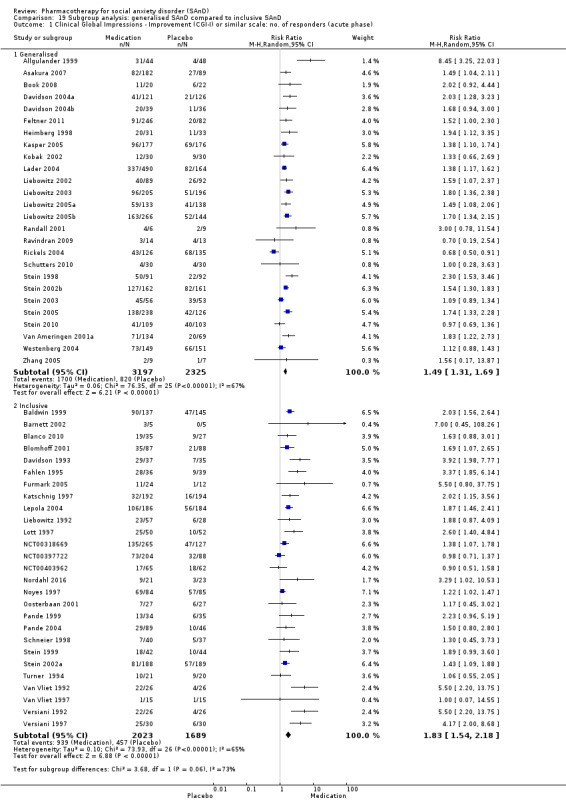

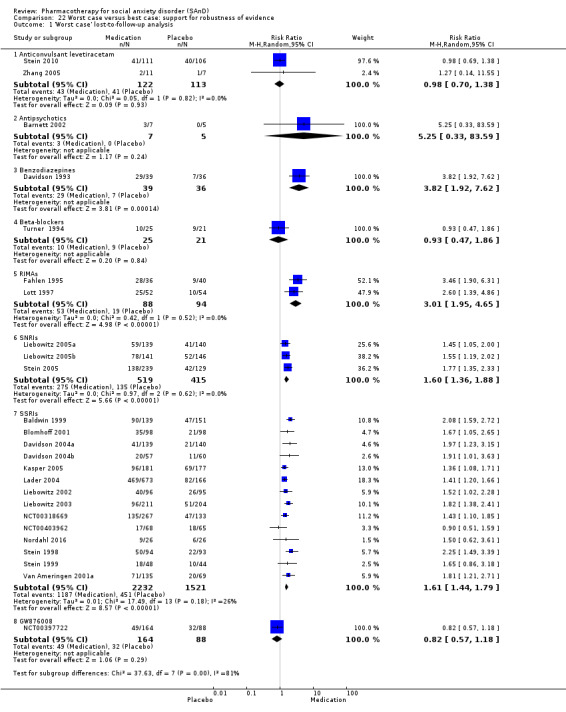

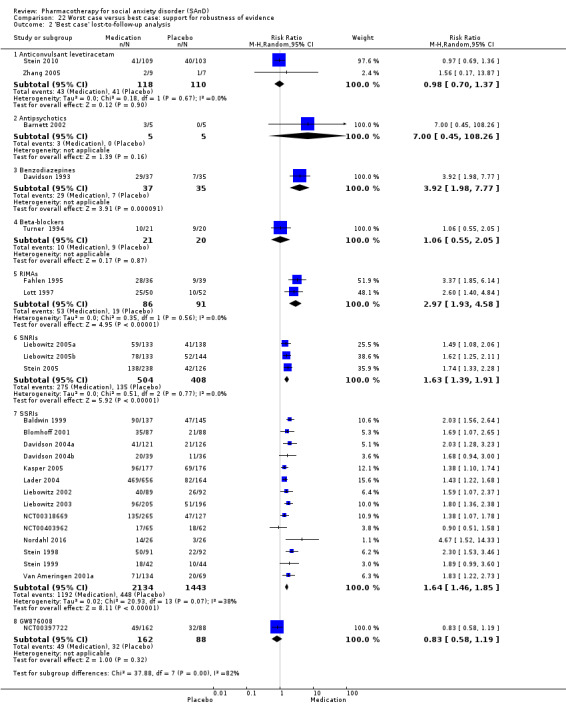

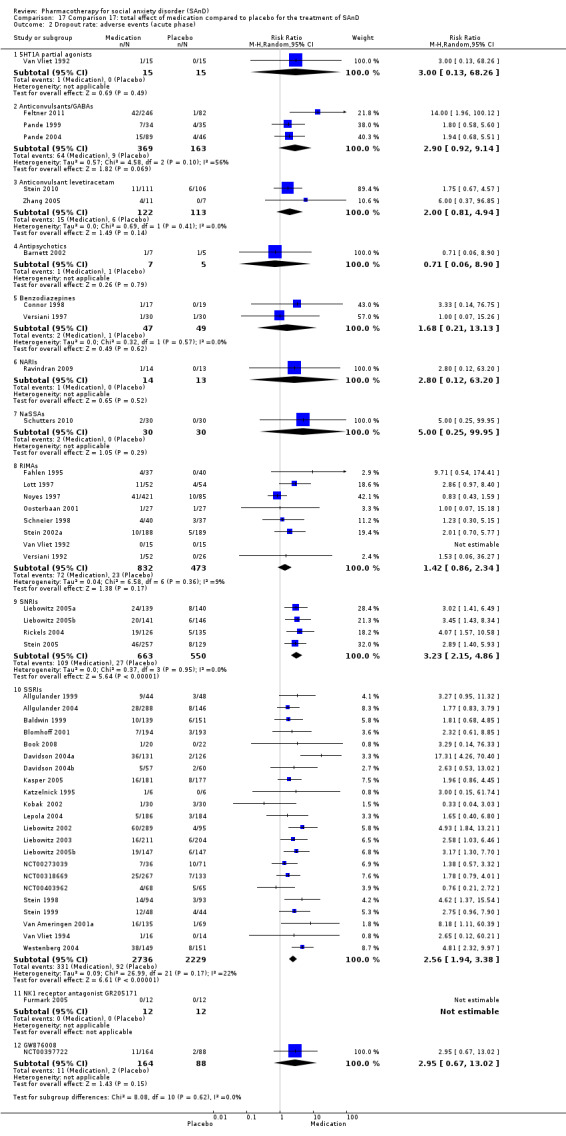

We included 66 RCTs in the review (> 24 weeks; 11,597 participants; age range 18 to 70 years) and 63 in the meta‐analysis. For the primary outcome of treatment response, we found very low‐quality evidence of treatment response for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) compared with placebo (number of studies (k) = 24, risk ratio (RR) 1.65; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.48 to 1.85, N = 4984). On this outcome there was also evidence of benefit for monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) (k = 4, RR 2.36; 95% CI 1.48 to 3.75, N = 235), reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase A (RIMAs) (k = 8, RR 1.83; 95% CI 1.32 to 2.55, N = 1270), and the benzodiazepines (k = 2, RR 4.03; 95% CI 2.45 to 6.65, N = 132), although the evidence was low quality. We also found clinical response for the anticonvulsants with gamma‐amino butyric acid (GABA) analogues (k = 3, RR 1.60; 95% CI 1.16 to 2.20, N = 532; moderate‐quality evidence). The SSRIs were the only medication proving effective in reducing relapse based on moderate‐quality evidence. We assessed the SSRIs and the serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine on the basis of treatment withdrawal; this was higher for medication than placebo (SSRIs: k = 24, RR 2.59; 95% CI 1.97 to 3.39, N = 5131, low‐quality evidence; venlafaxine: k = 4, RR 3.23; 95% CI 2.15 to 4.86, N = 1213, moderate‐quality evidence), but there were low absolute rates of withdrawal for both these medications classes compared to placebo. We did not find evidence of a benefit for the rest of the medications compared to placebo.

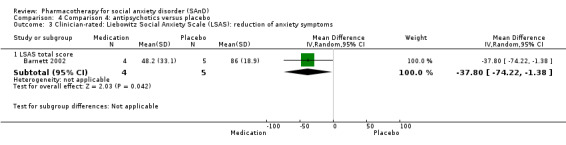

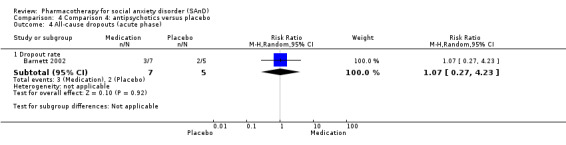

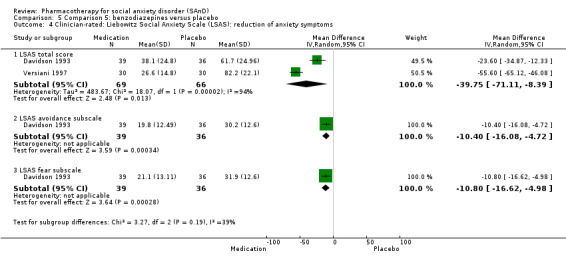

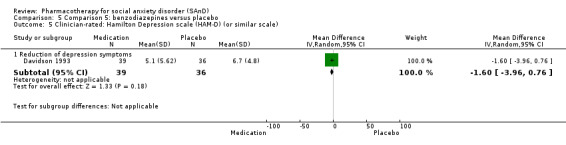

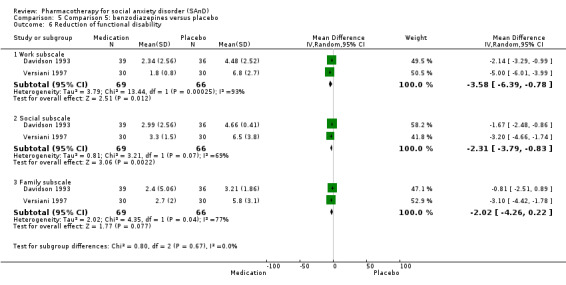

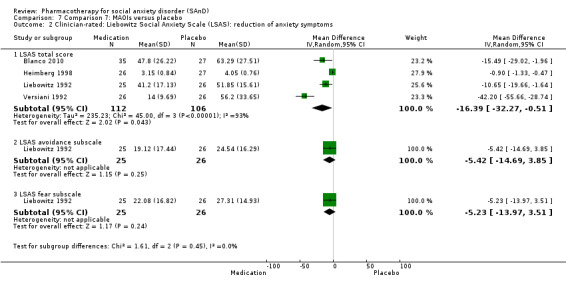

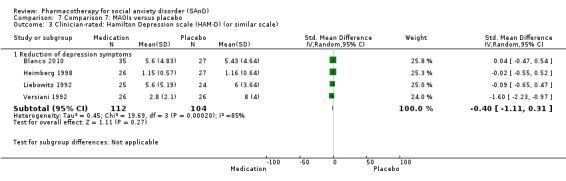

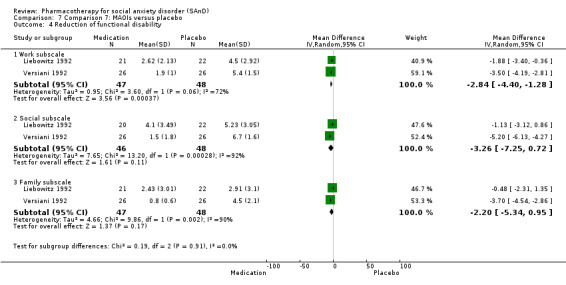

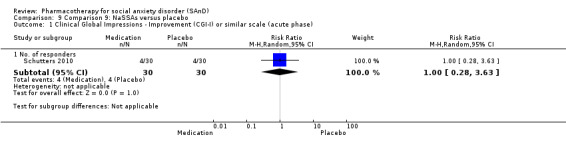

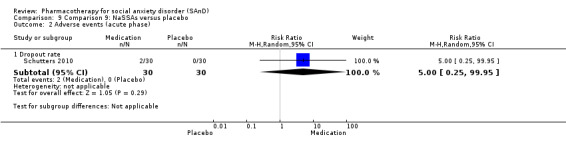

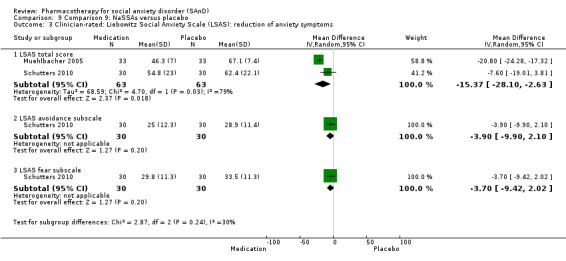

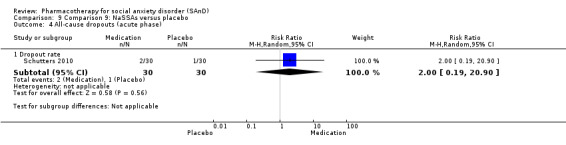

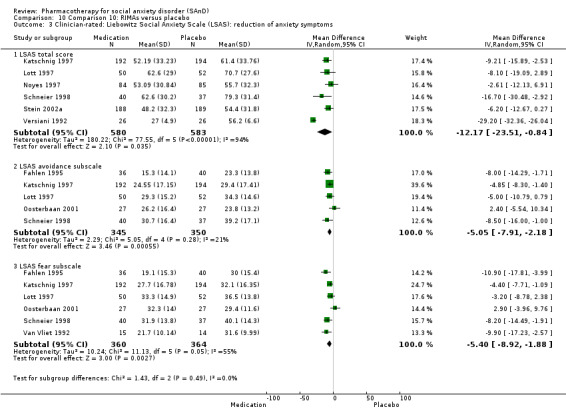

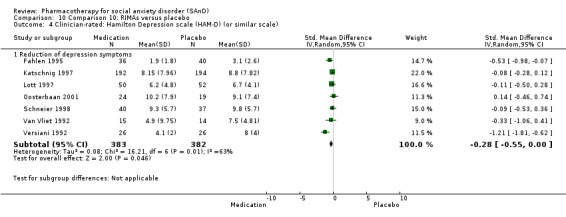

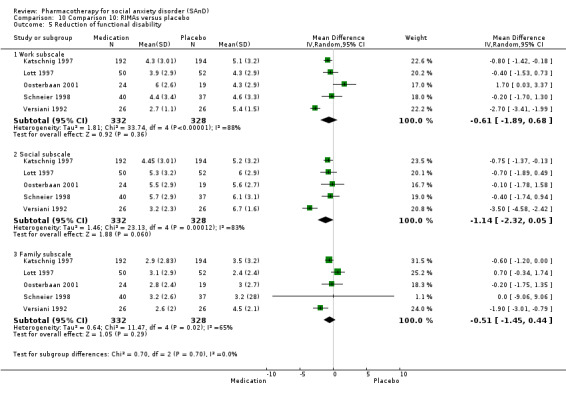

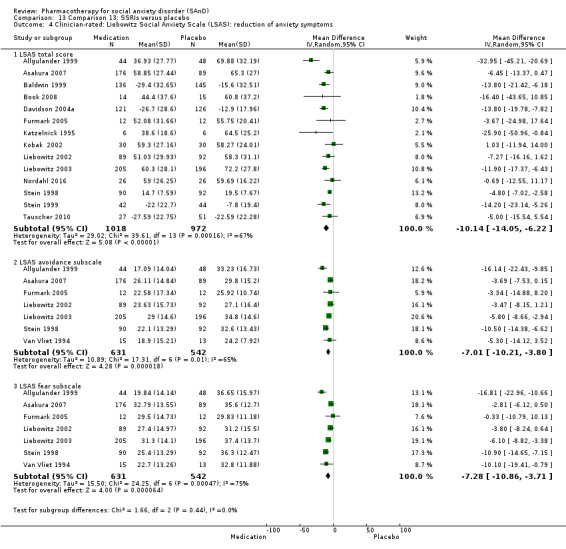

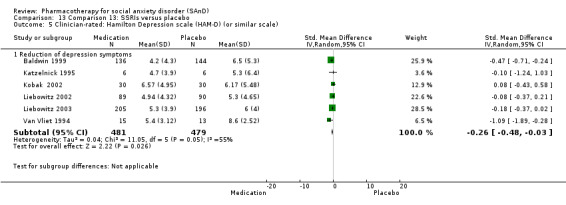

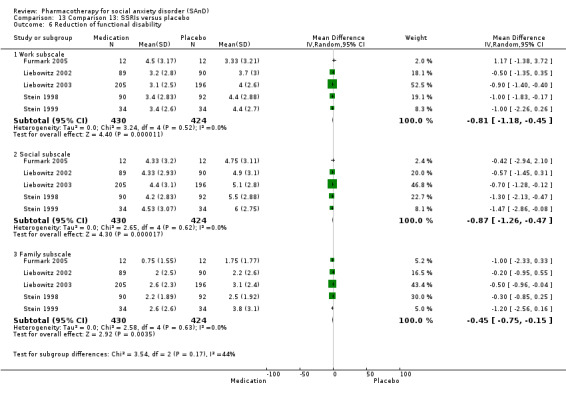

For the secondary outcome of SAnD symptom severity, there was benefit for the SSRIs, the SNRI venlafaxine, MAOIs, RIMAs, benzodiazepines, the antipsychotic olanzapine, and the noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA) atomoxetine in the reduction of SAnD symptoms, but most of the evidence was of very low quality. Treatment with SSRIs and RIMAs was also associated with a reduction in depression symptoms. The SSRIs were the only medication class that demonstrated evidence of reduction in disability across a number of domains.

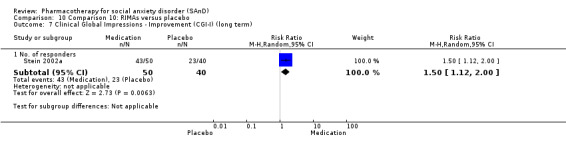

We observed a response to long‐term treatment with medication for the SSRIs (low‐quality evidence), for the MAOIs (very low‐quality evidence) and for the RIMAs (moderate‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

We found evidence of treatment efficacy for the SSRIs, but it is based on very low‐ to moderate‐quality evidence. Tolerability of SSRIs was lower than placebo, but absolute withdrawal rates were low.

While a small number of trials did report treatment efficacy for benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, MAOIs, and RIMAs, readers should consider this finding in the context of potential for abuse or unfavourable side effects.

Plain language summary

Medication for social anxiety disorder (SAnD): a review of the evidence

Why is this review important?

Individuals with SAnD often experience intense fear, avoidance, and distress in unfamiliar social situations. There is evidence that medications are useful in minimising these symptoms.

Who will be interested in this review?

‐ People with SAnD.

‐ Families and friends of people who suffer from anxiety disorders.

‐ General practitioners, psychiatrists, psychologists, and pharmacists.

What questions does this review aim to answer?

‐ Is pharmacotherapy an effective form of treatment for SAnD in adults?

‐ Is medication effective and tolerable for people in terms of side effects?

‐ Which factors (methodological or clinical) predict response to pharmacotherapy?

Which studies were included in the review?

We included studies comparing medication with placebo for the treatment of SAnD in adults.

We included 66 trials in the review, with a total of 11,597 participants.

What does the evidence from the review tell us?

There was evidence of benefit that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were more effective than placebo, although the evidence was of very low quality. There was also evidence of benefit for monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase A (RIMAs), and benzodiazepines, even though the evidence was low in quality. The anticonvulsants gabapentin and pregabalin also showed moderate‐quality evidence of a clinical response. We did not observe this effect for the remaining medication classes. The SSRIs were the only medication proving effective in reducing relapse based on moderate‐quality evidence. There was low‐quality evidence that more people taking SSRIs and SNRIs dropped out due to side effects than those taking placebo, but absolute withdrawal rates were low.

For the outcome of SAnD symptom severity, there was evidence of benefit for SSRIs, the serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine, MAOIs, RIMAs, benzodiazepines, the antipsychotic olanzapine, and the noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA) atomoxetine, but most of the evidence was of very low quality. SSRIs and RIMAs reduced depression symptoms, and SSRIs reduced functional disability across all domains.

We also observed response to long‐term treatment with SSRIs (based on low‐quality evidence), MAOIs (based on very low‐quality evidence), and RIMAs (based on moderate‐quality evidence).

What should happen next?

Most evidence for treatment efficacy is related to SSRIs. Nevertheless, SSRI trials were associated with very low‐quality evidence and high risk of publication bias. It would be useful for future studies to evaluate the treatment of SAnD in people with comorbid disorders, including substance use disorders. Trials that provide adequate information on randomisation and allocation concealment are needed.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Although the symptoms of social anxiety disorder (SAnD) have long been recognised (Marks 1966), the disorder only appeared within the official psychiatric nomenclature relatively recently (DSM‐III 1980). Diagnostic criteria for SAnD in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐III) encouraged research on its epidemiology, psychobiology, and treatment. Subsequent epidemiological research determined that the disorder is highly prevalent in a wide range of settings, that it is characterised by significant chronicity and comorbidity, and that it is associated with marked functional impairment, including academic, occupational, marital, and social dysfunction (Stein 2008). Such data allay skepticism about whether SAnD is really a medical disorder and support the importance of pharmacotherapy for its treatment.

SAnD usually begins in childhood or adolescence, with studies reporting lifetime prevalence rates of between 3% and 16% (Kessler 1994; Kessler 2005). Some European studies describe a one‐year prevalence of 2% to 5% (Wancata 2009). Typically, individuals with SAnD experience severe, intense fear of drawing attention to themselves in unfamiliar social situations or negative evaluation in situations that are potentially embarrassing or humiliating. This in turn results in avoiding the phobic situation or tolerating it with extreme distress. The affected individual recognises this fear as unreasonable, excessive, and more than mere shyness. These symptoms may take the form of a situationally predisposed panic attack and always impair functioning on a number of levels (DSM‐IV 2004).

There is a growing body of work demonstrating that SAnD is mediated by specific neurocircuitry, with serotonergic and dopaminergic systems particularly relevant (Stein 2002d), providing a rationale for the use of pharmacotherapy. The glutamatergic and noradrenergic systems, as well as substance P, may also be implicated in the neurological basis of SAnD, suggesting a role for agents such as gabapentin, pregabalin, and neurokinin‐1 receptor antagonists (Pande 1999; Pande 2004, Tauscher 2010). Indeed there is accumulating evidence that particular medications are effective in the management of SAnD (Stein 2004).

The effectiveness of cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT) in managing SAnD is also receiving increasing empirical support (Dorrepaal 2014; Fedoroff 2001; Gould 1997), and current expert consensus is that both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy have a role in the management of this disorder (Ballenger 1998; Bandelow 2002; Bandelow 2012; Bandelow 2015). Interestingly, both CBT and pharmacotherapy are able to normalise functional neuroanatomical abnormalities in SAnD (Furmark 2002). Nevertheless, this review focuses exclusively on pharmacotherapy interventions.

Description of the intervention

Research has evaluated a range of medications for SAnD. Early reports noted the potential value of irreversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) (Fahlen 1995; Van Vliet 1992), beta‐blockers (Gorman 1987; Turner 1994), reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase A (RIMAs) (Tyrer 1973; Versiani 1992), and high potency benzodiazepines (Davidson 1991). More recent studies have focused on the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (Van der Linden 2000), plus other newer agents such as GW876008 (NCT00397722). Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have also assessed buspirone (Davidson 1993), the noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA) mirtazepine (Muehlbacher 2005), the new generation antipsychotic olanzapine (Barnett 2002), the highly selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (NARI) atomoxetine (Ravindran 2009), the serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor (SARI) nefazodone (Van Ameringen 2007), the serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine (Rickels 2004), and certain anticonvulsants/gamma‐amino butyric acids (GABAs) (Pande 1999; Pande 2004).

How the intervention might work

Although the pathophysiology of SAnD is incompletely understood, various mono‐aminergic systems, such as the serotonergic, dopaminergic, and noradrenergic systems, may play a role in mediating SAnD symptoms. Strongly serotonergic drugs such as SSRIs have specific activity in the inhibition of serotonin reuptake, with minimal direct effects on norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake. This inhibition of reuptake increases the bio‐available concentration of serotonin, which then binds to and activates various receptors. Clinical efficacy is observed with 70% to 80% occupancy of serotonin transporters (Stahl 2008). SNRIs are potent inhibitors of the reuptake of catecholamines but weak inhibitors of dopamine reuptake (Rickels 2004; Stahl 2008). The putative effects of the selective NARI atomoxetine on the noradrenergic neurotransmitter system in adults and children with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), reported by Chamberlain 2007 and Michelson 2001, suggest potential use for anxiety and mood disorders (Ravindran 2009). There is evidence to suggest that some serotonin‐dopamine antagonists (SDAs) such as quetiapine and olanzapine may possess anxiolytic properties, and they may potentially have a role in treatment‐resistant SAnD (Barnett 2002; Vaishnavi 2007). Nefazodone is an agent with both pre‐ and postsynaptic serotonin reuptake inhibition, but concerns about hepatotoxicity limit its use in clinical practice (Van Ameringen 2007).

MAOIs increase biogenic amine neurotransmitter levels by inhibiting their degradation, facilitating presynaptic reuptake of these chemicals through specific transporter molecules and inhibiting their de‐amination in mitochondria by the enzyme MAO. This inhibition may be either reversible or irreversible (Stahl 2008). RIMAs are generally safer and better tolerated than MAOIs and have shown efficacy in treating SAnD (Versiani 1992). The drug functions by selectively binding to a specific isoenzyme of monoamine oxidase (Davidson 2006).

Beta‐adrenoreceptor antagonists block catecholamines released in the stress response, thus potentially reducing the physiological symptoms associated with SAnD. This may then enable the individual to function with fewer objective signs of anxiety (Liebowitz 1992; Stahl 2008; Turner 1994). The NaSSA mirtazepine has potent action on central adrenergic receptors, leading to a net increase in noradrenaline and serotonin, without the unwanted activation of cholinergic receptors (Muehlbacher 2005).

The efficacy of benzodiazepines in the treatment of many anxiety disorders is consistent with the hypothesized role of GABA in these conditions. In low doses, benzodiazepines act as anxiolytic agents and may be especially useful in providing rapid control of anxiety symptoms (Gorman 2003; Pecknold 1997; Stahl 2008). Repeated buspirone treatment may desensitise inhibitory 5‐HT1A receptors and this, together with its modest postsynaptic 5‐HT1A receptor agonist actions, could lead to an overall increase in 5‐HT neurotransmission as well (Cowen 1997).

The anticonvulsant pregabalin reduces the release of norepinephrine, glutamate, and substance P from the brain and spinal cord and may have a benefit in anxiety reduction (Pande 2004). Gabapentin may be similarly effective for these conditions (Stephen 2013).

Newer medications such as GW876008 have corticotropin‐releasing factors (CRFs) that target behavioural, autonomic, and neurochemical responses linked to a variety of anxiety and stress‐related disorders (Hubbard 2011). GW876008 also plays a role in the activation of the hypothalamus in patients with anxiety (Hubbard 2011).

Why it is important to do this review

A systematic review of pharmacotherapy studies may be useful in tackling several questions for the field. First, is pharmacotherapy in fact an effective form of treatment in SAnD? Given scepticism about SAnD diagnosis and the importance of psychological models and psychotherapy studies for the disorder, the role of pharmacotherapy remains moot for some. For those who accept the role of pharmacotherapy, questions remain about the appropriate dose and duration of treatments. Although in the late 1990s expert consensus suggested continuing pharmacotherapy for at least a year, there was arguably relatively little data to support this conclusion at the time (Ballenger 1998).

Second, are particular medication classes more effective in treating symptoms, more tolerable to the patient in terms of adverse events, or both? The use of recently introduced antidepressants (e.g. SSRIs) for SAnD has raised the question of how these agents compare with older medications (e.g. MAOIs). Current expert consensus has suggested that in view of their efficacy and tolerability, SSRIs should be considered as first‐line medications for the treatment of SAnD, while beta‐blockers have a role in the management of performance anxiety (Ballenger 1998; Bandelow 2002; Bandelow 2012; Bandelow 2015); it is important to determine whether such recommendations are supported by evidence from RCTs.

Third, can a systematic review of RCTs provide information about the most important variables affecting pharmacotherapy response? Methodological factors such as the number of participating centres or the duration of the trial may affect treatment outcomes (Stein 2002c). Some authors have also suggested that clinical factors such as the nature of the SAnD sub‐type present (e.g. generalised versus non‐generalised), and the severity of baseline symptoms, may play a role (Stein 2002c). The body of evidence from RCTs may provide more conclusive information about the predictors of pharmacotherapy response in this disorder.

Indeed, a series of reviews of the pharmacotherapy of SAnD has been published (Blanco 2002; Blanco 2013; Curtiss 2017; De Menezes 2011). These reviews have been useful in summarising the existing research, pointing to methodological flaws, and outlining areas for future research. A number of systematic reviews also exist (Blanco 2003; Davis 2014; Fedoroff 2001; Gould 1997; Van der Linden 2000), and these have provided useful lessons for both clinicians and researchers. Further reviews in this area, from Cochrane or elsewhere, need to adhere to guidelines for the systematic identification of trials, investigation of sources of heterogeneity, measurement of methodological quality, and estimation of the effects of intervention (Moher 1999; Mulrow 1997).

The authors updated the systematic review of RCTs of the pharmacotherapy of SAnD, following Cochrane guidelines and software (Higgins 2011; RevMan 2014).

Objectives

To assess the effects of pharmacotherapy for social anxiety disorder in adults and identify which factors (methodological or clinical) predict response to treatment.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered all RCTs, irrespective of publication status, methodological differences, or language. We only included trials comparing multiple forms of medication if one of the comparison groups was a placebo group. Because publication is not necessarily related to study quality and indeed may imply certain biases (Dickersin 1992; Easterbrook 1991; Scherer 1994), we also considered unpublished reports, abstracts, and brief and preliminary reports. We also included cluster‐randomised controlled trials, cross‐over trials and multiple treatment trials in the analysis.

Types of participants

Participant characteristics

We included adult participants diagnosed with SAnD irrespective of diagnostic criteria and measure, duration and severity of SAnD symptoms, age, and sex. We did, however, tabulate these descriptors in order to address the question of their possible impact on the effects of medication.

Comorbidities

We placed no restrictions on comorbid psychopathological disorders secondary to SAnD.

Setting

We placed no restrictions on setting.

Subsets of participants

We did not include trials that only included a subset of participants that met the review inclusion criteria in the analysis. None of the trials provided such information, so randomisation was preserved.

Types of interventions

We considered any medication administered to treat SAnD versus an active or non‐active placebo. We also included trials with multiple treatment arms if the comparator was a placebo, as well as placebo‐controlled trials studying multimodal treatments (cognitive behavioural therapy), if an active drug was a comparator.

Experimental interventions

We grouped specific pharmacological interventions according to medication class. We added anticonvulsants/GABAs, the anticonvulsant levetiracetam, NARIs, NaSSAs, and SARIs post hoc (see Differences between protocol and review). The medication classes are listed below.

5HT1A partial agonists (e.g. buspirone).

Anticonvulsants/gamma‐amino butyric acids (GABAs, e.g. gabapentin and pregabalin).

The anticonvulsant levetiracetam.

Antipsychotics (e.g. olanzapine).

Benzodiazepines (e.g. clonazepam and bromazepam).

Beta‐blockers (e.g. atenolol).

Mono‐amine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs, e.g. brofaromine and moclobemide).

Noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (NARIs, e.g. atomoxetine and mirtazepine).

Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSAs, e.g. mirtazepine).

Reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase A (RIMAs, e.g. phenelzine).

Serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors (SARIs, e.g. nefazodone).

Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs, e.g. venlafaxine).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs, e.g. paroxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, fluoxetine and citalopram).

Other medications (e.g. GW876008, GR205171 and LY686017).

Comparator interventions

Placebo (active or non‐active).

We placed no restrictions on timing, dose, duration, or co‐interventions.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Treatment efficacy:

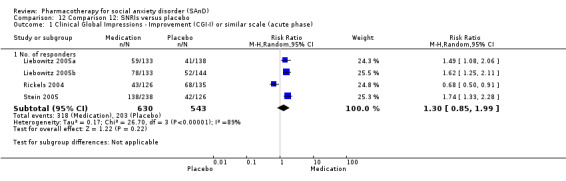

Clinical Global Impressions Improvement scale or similar: we determined treatment efficacy from the number of participants with SAnD who responded to treatment, as assessed by the Clinical Global Impressions Improvement scale (CGI‐I) or a closely related measure or definition (Guy 1976). The CGI ranges from 1 (normal, not at all ill) to 7 (among the most extremely ill patients). We defined responders as having a change item score of 1 ('very much') improved and 2 ('much') improved. Given its wide use and its reliability as a robust measure of the clinical value of treatment in SAnD, the CGI‐I served as a primary outcome measure for comparisons of both short‐ and long‐term trials in this review.

Relapse rate: The number of treatment responders who subsequently relapsed, according to investigator‐defined criteria, was compared between the medication and control groups.

2.Treatment tolerability: we included the total proportion of participants who withdrew from the RCTs due to treatment‐emergent side effects in the analysis as a surrogate measure of treatment tolerability, in the absence of other more direct indicators.

Secondary outcomes

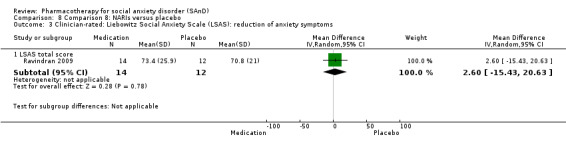

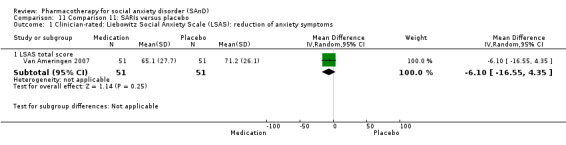

Reduction in SAnD symptoms: we assessed symptom severity and, where available, symptom cluster response, using the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS), a validated, commonly used, and psychometrically sound instrument (Liebowitz 1987). The LSAS is a 24‐item scale that provides separate scores for fear and avoidance in social and performance situations, with higher scores representing increased social anxiety. The LSAS contains three total scores: total fear score (0 to 72), total avoidance score (0 to 72), and total overall score (0 to 144). Suggested interpretations are that total scores of 55 to 65 indicate moderate social phobia; 65 to 80, marked social phobia; 80 to 95, severe social phobia; and greater than 95, very severe social phobia.

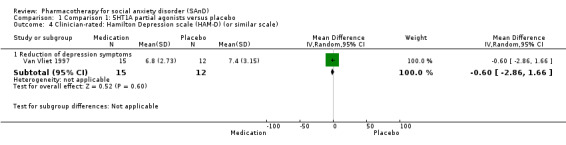

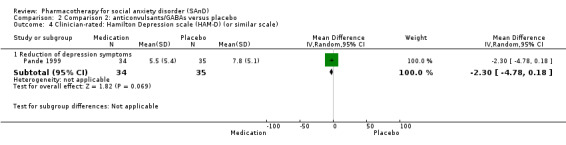

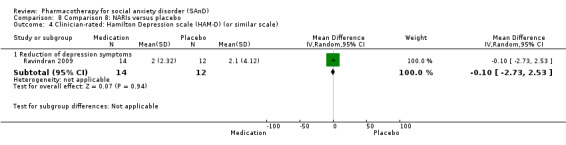

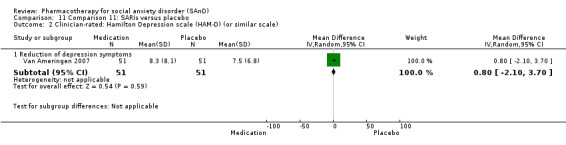

Reduction in depressive symptoms: we determined comorbid depressive symptoms using standardised scales such as the Hamilton Depression scale (HAM‐D) (Hamilton 1959) or Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HDRS), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck 1961), the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) or similar. The Hamilton Depression scale (HAM‐D) is a multiple item questionnaire with 17 to 29 items (depending on the version). Patients are rated on a 3 or 5 point scale. A score of 0‐7 is considered to be normal and a score of 20 or higher moderate, severe, or very severe. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a 21‐question multiple‐choice self‐report, one of the most widely used psychometric tests for measuring the severity of depression. A score of 0–9 indicates minimal depression, 10–18 mild depression, 19–29 moderate depression and 30–63 severe depression. The MADRS is a ten‐item diagnostic questionnaire which psychiatrists use to measure the severity of depressive episodes in patients with mood disorders. A higher MADRS score indicates more severe depression, and each item yields a score of 0 to 6. The overall score ranges from 0 to 60. Usual cutoff points are 0 to 6 – normal/symptom absent; 7 to 19 – mild depression; 20 to 34 – moderate depression; and > 34 – severe depression.

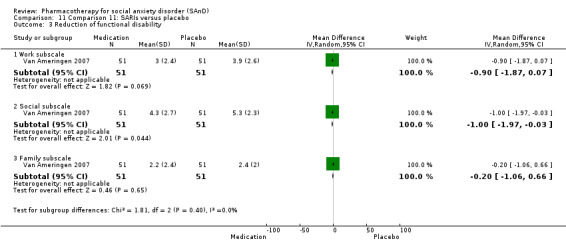

Functional disability: we considered measures such as the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) (Sheehan 1996). The Sheehan Disability Scale is a composite of three self‐rated items designed to measure the extent to which three major sectors in the patient’s life are impaired by panic, anxiety, phobic, or depressive symptoms. The patient rates the extent to which his or her 1) work, 2) social life or leisure activities, and 3) home life or family responsibilities are impaired by his or her symptoms on a 10‐point visual analogue scale. The numerical ratings of 0‐10 can be translated into a percentage if desired. The three items may be summed into a single dimensional measure of global functional impairment that ranges from 0 (unimpaired) to 30 (highly impaired).

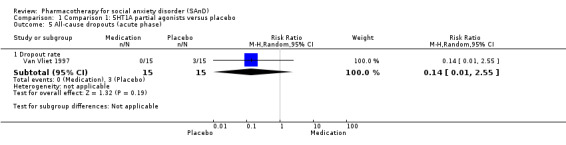

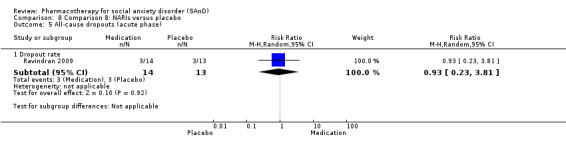

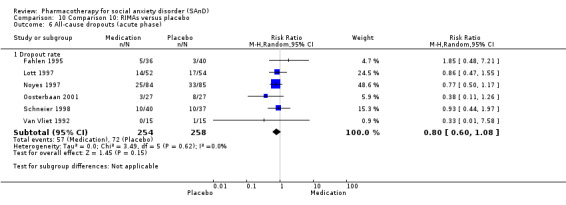

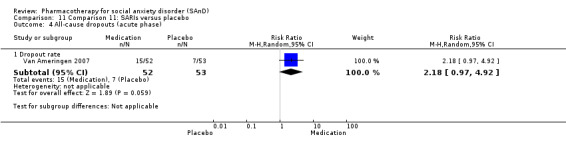

Dropout rates: we compared all‐cause dropout rates for both short‐ and long‐term trials in order to provide some indication of treatment effectiveness.

Timing of outcome assessment

For studies that assessed outcomes at multiple time points (e.g. Baldwin 1999; Blomhoff 2001; Feltner 2011), we synthesised data from the last assessment within a 16‐week, postbaseline period to estimate the acute effects of medication, with the final assessment in longer trials providing data for the assessment of maintenance effects (20 to 24 weeks).

Hierarchy of outcome measures

If several measures for one outcome were reported, we selected the measures or scales laid out in the Methods. We used both clinician‐rated scales and self‐reported scales.

Search methods for identification of studies

Cochrane Specialised Register (CCMDCTR)

The Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group maintained a comprehensive, specialised register of randomized controlled trials, the CCMDCTR (to June 2016). The register contains over 39,000 reference records (reports of RCTs) for anxiety disorders, depression, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, self‐harm and other mental disorders within the scope of this Group. The CCMDCTR is a partially studies based register with >50% of reference records tagged to c12,500 individually PICO coded study records. Reports of trials for inclusion in the register were collated from (weekly) generic searches of Medline (1950‐), Embase (1974‐) and PsycINFO (1967‐), quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and review specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials were also sourced from international trial registries, drug companies, the hand‐searching of key journals, conference proceedings and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Details of CCMD's core search strategies (used to identify RCTs) can be found on the Group's website with an example of the core Medline search displayed in Appendix 1.

Electronic searches

The CCMD Group's information specialist searched the CCMDCTR (studies and references) registers on condition alone, due to concerns regarding multiple searches, change of authorship, and broad scope of this review. The latest version of the review incorporates results of searches to 17 August 2015 (Appendix 2). The information specialist ran a pre‐publication search (2 August 2017) (Appendix 3) and we have placed two additional studies in Awaiting Classification. These will be incorporated in the next version of the review, as appropriate.

The review author team also conducted earlier searches on PubMed, PsycINFO and clinicaltrials.gov (1966 to 2011), using terms 'social phobia OR social anxiety disorder' and 'medication OR pharmacotherapy OR treatment'. We undertook an initial broad search to find RCTs and open‐label trials, as well as journal and chapter reviews of the pharmacotherapy of SAnD.

The review authors also searched the ICTRP (apps.who.int/trialsearch) using the terms 'social phobia' or 'social anxiety' as search queries for this database (August 2012). We repeated this search on 4 November 2015 and 15 March 2017.

A 2016 Google Scholar search also yielded an additional included study by Nordahl 2016. We repeated this search on 15 March 2017.

Searching other resources

Reference lists

We scanned the bibliographies of all identified trials for additional studies.

Personal communication

We obtained published and unpublished trials from key researchers, who we identified by the frequency with which they were cited in the bibliographies of RCTs and open‐label studies.

Data collection and analysis

With the exception of the Egger test of funnel plot asymmetry, and generation of the contour enhanced funnel plots (created using the metafor package of the R statistical computing platform (Viechtbauer 2010), we used Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) to perform all analyses reported in this review (RevMan 2014).

Selection of studies

Two authors (TW and JI) independently assessed the title and abstract of RCTs identified from the search. We subsequently scanned full‐text articles agreed upon as potentially eligible. The authors independently collated the data listed under Data extraction and management that satisfied the inclusion criteria specified in the Criteria for considering studies for this review section. We listed studies for which we need additional information to determine eligibility in the Studies awaiting classification table, pending the availability of this information. We resolved any disagreements in the trial assessment and data collation procedures by discussion with a third review author (DS).

Data extraction and management

We obtained the following information from each trial.

Description of the trials, including the year of publication, diagnostic instrument used (e.g. the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV (SCID)), use of placebo run‐in, use of a minimal severity criterion, number of participating centres, presence of support from the pharmaceutical industry, and methodological quality.

Characteristics of participants, including the diagnostic criteria met (e.g. DSM‐IV), subtype of SAnD (e.g. generalised SAnD), duration of symptoms, presence of comorbid depression, mean age, age range, and sex distribution.

Characteristics of the intervention, including its duration, the class of medication used, and the doses employed.

Outcome measures employed (primary and secondary), and summary continuous (means and standard deviations) and dichotomous (number of responders) data. We included additional information, such as the number of dropouts per group as well as the number that dropped out due to treatment‐emergent side effects.

Main comparisons

We planned to compare the following medications (grouped according to medication class) against placebo for treating SAnD.

5HT1A partial agonists.

Anticonvulsants/GABAs.

The anticonvulsant levetiracetam.

Antipsychotics.

Benzodiazepines.

Beta‐blockers.

MAOIs.

NARIs.

NaSSAs.

RIMAs.

SARIs.

SNRIs.

SSRIs.

Other medications.

Subgroup analyses included the following comparisons.

Multicentre compared to single‐centre trials.

Generalised SAnD compared to inclusive SAnD.

Industry funding compared to no industry funding.

Inclusion versus exclusion of participants diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias of each included study using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011). We considered the following six domains.

Random sequence generation: did investigators use a random number table or a computerised random number generator?

Allocation concealment: was the medication sequentially numbered, sealed, and placed in opaque envelopes?

Blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors for each main outcome or class of outcomes: was knowledge of the allocated treatment or assessment adequately prevented during the study?

Incomplete outcome data for each main outcome or class of outcomes: were missing or excluded outcome data adequately addressed?

Selective outcome reporting: were the reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting? We could only make such a judgement based on the availability of the protocol.

Other sources of bias: was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias?

We extracted relevant information from each study report, where provided. We made a judgement on the risk of bias for each domain within and across studies, based on the following three categories: 'low' risk of bias, 'unclear' risk of bias, and 'high' risk of bias. Two independent review authors (TW and JI) assessed the risk of bias for the included studies. We discussed any disagreements with a third review author (DS). Where necessary, we contacted the authors of the studies for further information. We present all risk of bias data graphically and describe them in the text.

Measures of treatment effect

Categorical data

We calculated the risk ratio (RR) of response to treatment for the dichotomous outcomes of interest. We used RR instead of odds ratio (OR), as ORs are more difficult to interpret. ORs also tend to overestimate the size of the treatment effect relative to RRs, especially when the occurrence of the outcome of interest is common (as anticipated in this review, with an expected response greater than 20%) (Deeks 2011).

Continuous data

In cases in which studies used a range of scales for each outcome, such as the assessment of comorbid depressive symptoms on the Hamilton Depression scale (HAM‐D) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), we calculated treatment outcome using the standardised mean difference (SMD). The SMD standardises the differences between the means of the treatment and control groups in terms of the variability observed across all participants in the trial.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

In cluster‐randomised trials, groups of individuals are randomised to different interventions rather than individuals themselves. Analysing treatment response in cluster‐randomised trials without taking these groupings into account is potentially problematic, as participants within any one cluster often tend to respond in a similar manner, and thus analyses cannot assume that participants' data are independent of the rest of the cluster. Cluster‐randomised trials also face additional risk of bias issues including recruitment bias, baseline imbalance, loss of clusters, and non‐comparability with trials randomising individuals (Higgins 2011). No cluster‐randomised trials were eligible for inclusion in this review. To prevent unit of analysis errors in future updates of this review, we plan to divide the effective sample size of each comparison group in trials that do not adjust for clustering by the design effect metric (Higgins 2011). For these analyses the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) that is incorporated within the design effect will be set equivalent to the median ICC from published cluster‐randomised pharmacotherapy RCTs for anxiety disorders.

Cross‐over trials

We only included cross‐over trials in the calculation of summary statistics when it was possible to extract medication and placebo/comparator data from the first treatment period or when the inclusion of these data from both treatment periods was justified by a washout period of sufficient duration that minimised the risk of carry‐over effects. In the latter case, we included data from both periods only when it was possible to determine the correlation between participants' responses to the interventions in the different phases (Elbourne 2002). A washout period of at least two weeks was necessary in the case of trials assessing the efficacy of agents with extended half‐lives, such as the SSRI fluoxetine (Gury 1999).

Multiple treatment groups

A number of the trials included in this review compared more than two intervention groups or multiple doses of the same medication against placebo. Including data from the same placebo group for these studies repeatedly in the same comparison would result in a unit of analysis error (Higgins 2011). To prevent these errors for trials comparing multiple dosages of the same agent to placebo, we averaged the mean and standard deviation of the outcome of interest across dosage groups. We included outcome data from multiple treatment arms in the same comparison if the agents tested were from different medication classes. We turned off the subtotals of the outcome if the placebo group appeared twice in the analysis to accommodate for the second medication. In the case of trials testing multiple agents from the same classes, and in calculating the total effect across all medication classes, we restricted data from multi‐arm RCTs to the agent that was least represented in the database.

We will circumvent unit‐of‐analysis bias resulting from the simultaneous comparison of multiple arms from the same trial in future updates of this review by means of a multiple‐treatments meta‐analysis (MTM) (Lumley 2002). An MTM allows the assessment of treatment efficacy through the combination of both direct and indirect comparisons of all interventions on a specific outcome. We can subsequently assess potential unit‐of‐analysis bias in a sensitivity analysis in which we compare the results obtained with those from a meta‐analysis restricted to data from direct comparisons of interventions.

Dealing with missing data

All analyses of dichotomous data were intention‐to‐treat (ITT). We only included data from trials providing information on the original group size (prior to dropouts) in the analyses of treatment efficacy. We gave preference within studies to the inclusion of summary statistics for continuous outcome measures derived from mixed‐effects models, followed by last observation carried forward (LOCF) and observed cases (OC) summary statistics (in that order). This is in line with evidence that mixed‐effects methods are more robust to bias than LOCF analyses (Verbeke 2000).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity by means of the Chi2 test for heterogeneity to assess whether observed differences in results were compatible with chance alone. A low P value (or a large Chi2 test relative to its degree of freedom (df)) provides evidence of heterogeneity of intervention effects (variation in effect estimates beyond chance). If the Chi2 test had a P value of less than 0.10, we interpreted it as evidence of heterogeneity, given the low power of the Chi2 test when the number of trials is small (Deeks 2011). We also used the Deeks' stratified test of heterogeneity (Deeks 200), as implemented in RevMan 5, to assess differences by means of the Qb metric in treatment response between subgroups, by subtracting the sum of the Chi2 statistic for the subgroups from the total Chi2 statistic for those subgroups.

In addition, we used the I2 statistic reported by RevMan 5 to quantify the inconsistency of the trial results within each analysis (Higgins 2003). Thresholds for the interpretation of I2 can be misleading, since the importance of inconsistency depends on several factors. We followed a rough guide for interpretation.

0% to 40%: might not be important.

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity.

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity.

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

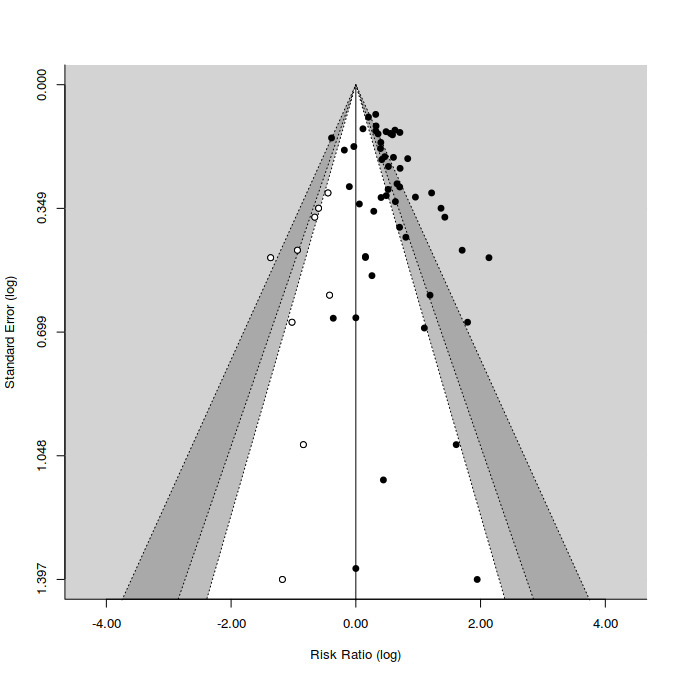

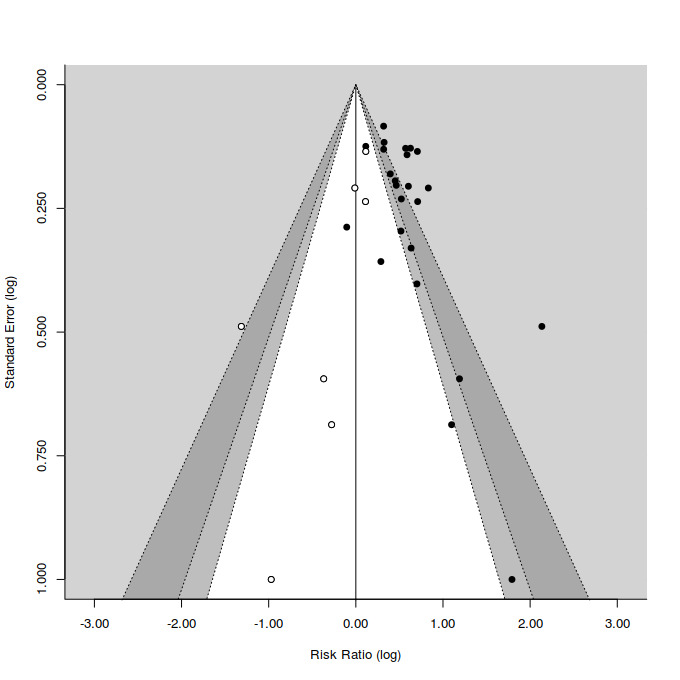

Assessment of reporting biases

Funnel plots provide a graphic illustration of the effect estimates of an intervention from individual studies against some measure of the precision of that estimate. We visually inspected publication bias from the funnel plot for treatment efficacy, with the consideration of confounding selection bias, poor methodological quality, true heterogeneity, artefact, and chance. We also calculated Eggers' regression tests as a more objective quantitative measure of funnel plot asymmetry using the Dersimonian and Laird estimator of heterogeneity (Egger 1997). Given that both tests are dependent on having 10 trials per outcome, we could only calculate this for SSRIs. Irwig 1998 and others have voiced concerns that the statistical phenomenon increasing the likelihood of falsely detecting publication bias when applying the Egger test to odds ratio effect estimates may extend to risk ratio effect estimates (Sterne 2011). Accordingly, we generated contour enhanced funnel plots, which explicitly illustrate the relationship between missing studies and the statistical significance of study findings at various statistical thresholds (e.g. alpha = 0.1, 0.05, and 0.01) (Peters 2008). We estimated the position of missing studies in these plots using the trim and fill method.

Data synthesis

We obtained binary and continuous treatment effects from a random‐effects model. Random‐effects analytic models include both within‐study sampling error and between‐study variation in determining the precision of the confidence interval around the overall effect size, whereas fixed‐effect modelling approaches take only within‐study variation into account. In recognition of the possibility of differential effects for different types of medication, such as the SSRIs and the MAOIs, we stratified all of the comparisons by medication class. We expressed the outcomes of these comparisons in terms of an average effect and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each subgroup.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted the following subgroup analyses to assess the degree to which methodological differences between trials might have systematically influenced differences observed in the primary treatment outcomes (Thompson 1994).

We compared multicentre versus single‐centre trials. The latter are more likely to be associated with lower sample size but will tend to have less variability in clinician ratings.

We compared trials including only participants diagnosed with the generalised form of SAnD versus those including both the generalised and specific subtypes of SAnD. Specialists recognise generalised SAnD as often representing a more severe form of the disorder.

In addition, we assessed the following.

Whether or not trials were industry funded. In general, published trials sponsored by pharmaceutical companies appear more likely to report positive findings than trials that are not supported by profit companies (Als‐Nielsen 2003; Baker 2003).

Whether or not the sample included patients diagnosed with major depression. Such an analysis might assist in determining the extent to which the efficacy of a medication agent in treating SAnD is independent of its ability to reduce symptoms of depression, an important consideration given the classification of many of these medications as anti‐depressants.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses determine the robustness of the review authors' conclusion to methodological assumptions made in conducting the meta‐analysis. We planned to compare the effect of assessing interventions in terms of clinical treatment response versus non‐response in light of evidence that treatment response may result in less consistent outcome statistics than non‐response (Deeks 2002). However, reports on this potential difference in outcome consistency have arisen only when the control group event rate was above 50%, far higher than the baseline proportion of response observed across trials in this review (30%). Accordingly, we did not conduct this analysis.

In addition, we performed a 'worst case/best case' analysis to determine whether the the coding of participants who were lost to follow‐up influenced the findings of treatment efficacy (Deeks 2011). In this analysis, we recorded all the missing data for the treatment group as responders in the worst case scenario, whereas in the best case, we coded all missing data for the control group as responders. If the conclusions regarding treatment efficacy did not differ between these two comparisons, we assumed that missing data in trial reports did not have a significant influence on this outcome.

Summary of findings tables

We compiled 'Summary of findings' tables to summarise the best evidence for all relevant outcomes (i.e. experimental versus comparator interventions), reporting the following six elements according to a fixed format (Higgins 2011).

A list of all important outcomes, both desirable and undesirable.

A measure of the typical burden of these outcomes (e.g. illustrative risk, or illustrative mean, on control intervention).

Absolute and relative magnitude of effect (if both are appropriate).

Numbers of participants and studies addressing these outcomes.

A grade of the overall quality of the body of evidence for each outcome.

Space for comments.

We based downgrading of the evidence rating for outcomes on five factors. We classified reasons for downgrading the evidence as 'serious' (downgrading the quality rating by one level) or 'very serious' (downgrading the quality grade by two levels).

Limitations in the design and implementation of the trial.

Indirectness of evidence.

Unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results.

Imprecision of results.

High probability of publication bias.

We classified the quality of evidence for each outcome according to the following categories.

High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate.

Main comparisons

We planned the following outcomes and grouped specific pharmacological interventions according to medication class.

5HT1A partial agonists versus placebo.

Anticonvulsants/GABAs versus placebo.

The anticonvulsant levetiracetam versus placebo.

Antipsychotics versus placebo.

Benzodiazepines versus placebo.

Beta‐blockers versus placebo.

MAOIs versus placebo.

NARIs versus placebo.

NaSSAs versus placebo.

RIMAs versus placebo.

SARIs versus placebo.

SNRIs versus placebo.

SSRIs versus placebo.

Other medication versus placebo.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

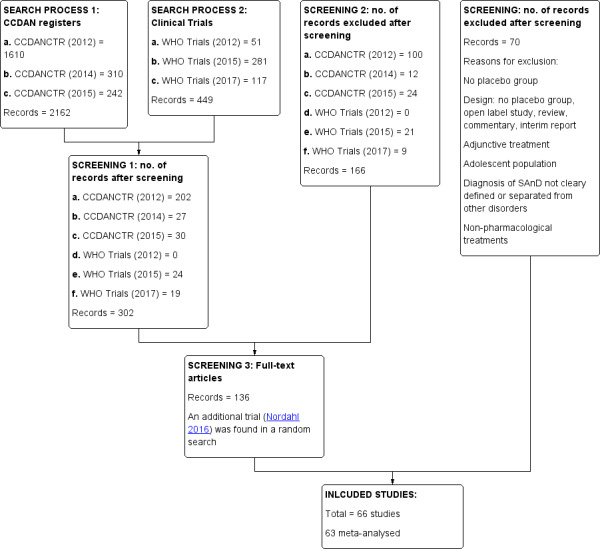

We found a total of 2611 study reports through the search process (CCMDCTR 2162; ICTRP 449). We scanned each title and abstract (if provided) for eligibility. Three hundred and two studies initially seemed relevant, but after further inspection we excluded 166 of these, leaving 136 studies that potentially met the inclusion criteria (we found the additional study by Nordahl 2016 from a search conducted in 2016). After independent review of the full‐text studies, we found that 70 failed to meet inclusion criteria, leaving 66 RCTs eligible for inclusion in the review (see Characteristics of included studies and Figure 1). Of the 66 trials, we included 63 RCTs in the meta‐analysis. Eleven studies are awaiting classification, and five studies are ongoing (see Studies awaiting classification and Ongoing studies).

1.

Study flow diagram.

The update search performed by CCMD's information specialist retrieved 754 records (de‐duplicated), and after screening the abstracts, we identified an addition two studies which we have added to awaiting classification. We will incorporate these into the next version of the review as appropriate.

Included studies

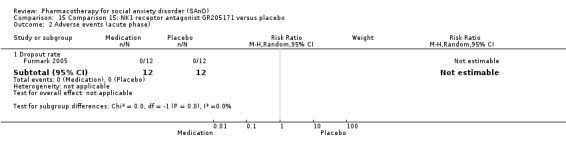

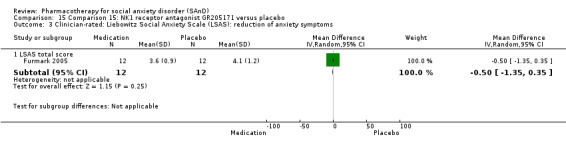

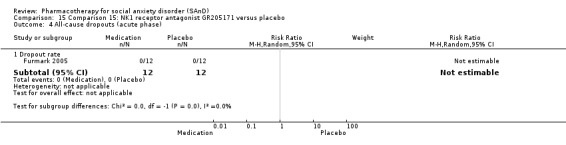

Design

The review includes 66 RCTs treating participants for SAnD from 1 to 24 weeks. Of these, 56 of the trials were short term (14 weeks or less), while 7 trials included a maintenance component, and 4 trials a relapse component (14 to 24 weeks or less). This update includes 29 new studies. All trials included a placebo comparison group, with eight studies having two medication arms (i.e. two trials assessing paroxetine and venlafaxine, and one trial each assessing citalopram and NK1 antagonist GR205171, paroxetine and escitalopram, phenelzine and atenolol, paroxetine and neurokinin‐1 (NK‐1) antagonist LY686017, phenelzine and moclobemide, and GW876008 and paroxetine) (Allgulander 2004; Furmark 2005; Lader 2004; Liebowitz 1992; Liebowitz 2005b; NCT00397722; Tauscher 2010; Versiani 1992). Katzelnick 1995 employed a a cross‐over design in testing the efficacy of sertraline. All trials were published in English, and pharmaceutical companies contributed funding for 41.

Participants

The 66 eligible trials included 11,597 participants aged 18 to 70, most of whom were outpatients. The average sample size was 176 and ranged from 12 in Barnett 2002 and Katzelnick 1995 to 839 in Lader 2004. Sixty trials involved both men and women, while Muehlbacher 2005 included only women and Moghadam 2015 only men. Adult participants were diagnosed with SAnD according to DSM criteria (DSM‐IV‐TR, DSM‐IV, DSM‐III‐R), assessed by means of a variety of instruments, including the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID/SCID‐I) (e.g. Moghadam 2015; NCT00470483), the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (e.g. Furmark 2005; Lepola 2004; NCT00403962; Stein 2002b; Zhang 2005), and the Initial Evaluation Form and the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule‐Revised (ADIS‐R) (e.g. Turner 1994).

Twenty‐one studies included individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD), while MDD was an exclusion criterion for 41. Four studies did not specify, so we were unable to determine whether or not individuals with MDD could take part (Moghadam 2015; NCT00470483; Nordahl 2016; Tauscher 2010). We also reported other comorbidities related to functional disability and avoidant personality where provided.

Setting

Most eligible RCTs took place in the USA (number of studies (k) = 58), while others were in Europe (k = 10), Japan (k = 2), South Africa (k = 6), and Iran (k = 1). Of the trials included in the analysis, 24 studies were single‐centre trials, and 42 studies took place in multiple centres. Participants were recruited via telephone, newspaper, radio, or clinical referral. Recruitment settings included university‐based hospitals and centres, medical centres, and research and private clinics.

Interventions

Approximately half of the included RCTs tested the efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; k = 34), including 19 studies of paroxetine, of which two studies had a third arm investigating venlafaxine, one study had a third arm investigating escitalopram, one had a third arm investigating LY686017 and another a third arm investigating GW876008 (Allgulander 1999; Allgulander 2004;Baldwin 1999; Book 2008; Lader 2004; Lepola 2004; Liebowitz 2002; Liebowitz 2005b; NCT00273039; NCT00318669; NCT00403962; NCT00397722; NCT00470483; Nordahl 2016; Randall 2001; Stein 1996; Stein 1998; Stein 2003; Tauscher 2010). In addition, the SSRI RCTs included five trials of fluvoxamine (Asakura 2007; Davidson 2004a; Stein 1999; Van Vliet 1994; Westenberg 2004), six trials of sertraline (Blomhoff 2001; Katzelnick 1995; Liebowitz 2003; Moghadam 2015; Van Ameringen 2001a; Walker 2000), two trials of fluoxetine (Davidson 2004b; Kobak 2002), and single RCTs of citalopram (Furmark 2005, with a third arm investigating NK1 antagonist GR205171) and escitalopram (Kasper 2005). The lowest and highest dosage for paroxetine ranged from 7.5 mg/d (NCT00403962) to 60 mg/d (Book 2008; NCT00397722; Nordahl 2016); for sertraline from 50 mg/d (Blomhoff 2001; Katzelnick 1995) to 200 mg/d (Katzelnick 1995; Liebowitz 2003; Van Ameringen 2001a; Walker 2000); for fluoxetine from 20 mg/d to 60 mg/d (Davidson 2004b); for fluvoxamine from 50 mg/d (Asakura 2007; Stein 1999; van Vliet 1997) to 300 mg/d (Asakura 2007; Davidson 2004a; Stein 1999; Stein 2003; Westenberg 2004); for citalopram from 20 mg/d to 40 mg/d (Furmark 2005); and for escitalopram from 10 mg/d to 20 mg/d (Kasper 2005).

Eight trials studied reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase A (RIMAs), including three RCTs of brofaromine (Fahlen 1995; Lott 1997; Van Vliet 1992), plus five of moclobemide (Katschnig 1997; Noyes 1997; Oosterbaan 2001; Schneier 1998; Stein 2002a). For brofaromine, the daily dosage ranged from 50 mg/d to 150 mg/d in both Lott 1997 and Van Vliet 1992, and for moclobemide, it ranged from 75 mg/d in Noyes 1997 to 750 mg/d in Stein 2002a.

Four trials evaluated the mono‐amine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) phenelzine, one of which had a third arm investigating atenolol and another investigating moclobemide (Blanco 2010; Heimberg 1998; Liebowitz 1992; Versiani 1992). Dosage for the phenelzine ranged from 15 mg/d in Blanco 2010 and Heimberg 1998 to 100 mg/d in Liebowitz 1992.

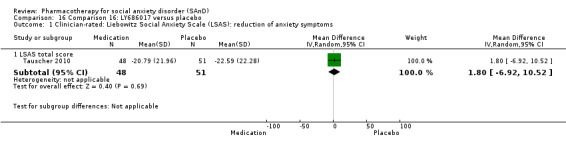

There were four trials of the serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine (Liebowitz 2005a; Liebowitz 2005b; Stein 2005; Rickels 2004). Dosage ranged from 75 mg/d to 225 mg/d in all of these trials.

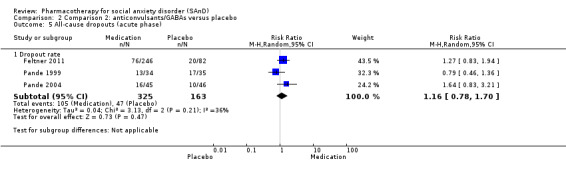

Three trials focused on anticonvulsants comprising gamma‐amino butyric acid (GABA) analogues (including two studies of pregabalin, Feltner 2011 and Pande 2004, and one of gabapentin, Pande 1999). Two trials investigated levetiracetam, another anticonvulsant (Stein 2010; Zhang 2005).

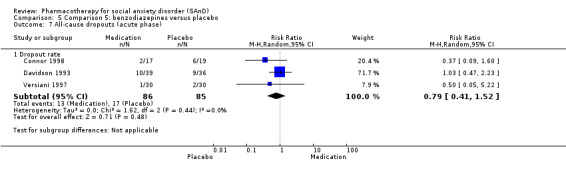

Three trials studied benzodiazepines, including two studies of clonazepam in doses ranging from 0.25 mg/d in both Connor 1998 and Davidson 1993 to 2.5 mg/d in Connor 1998, and one of bromazepam (Versiani 1997), administered in doses of 3 mg/d to 9 mg/d.

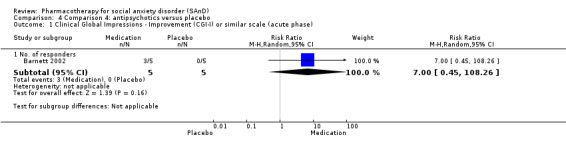

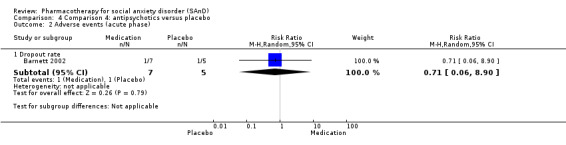

There were two trials on antipsychotics, including one study of olanzapine, with dosage ranging from 5 mg/d to 20 mg/d (Barnett 2002), and another study on quetiapine, with dosage of 25 mg/d to 300 mg/d (Vaishnavi 2007).

Two trials evaluated the noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA) mirtazepine, in doses ranging from 30 mg/d in Muehlbacher 2005 and Schutters 2010 to 45 mg/d in Schutters 2010.

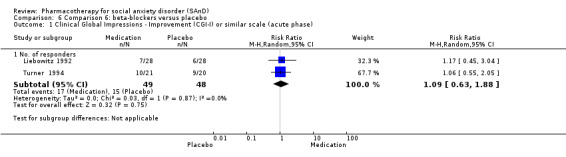

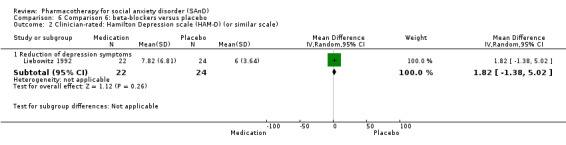

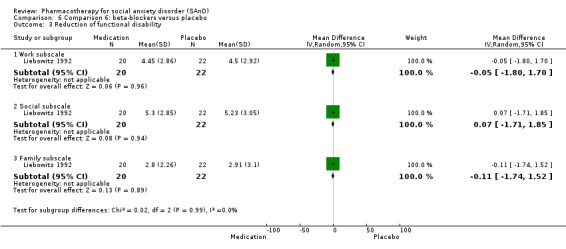

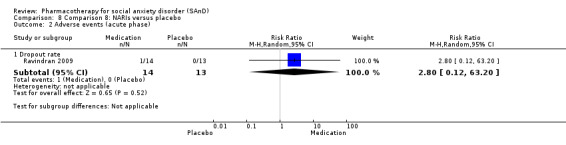

Turner 1994 assessed the beta‐blocker atenolol, administered in doses of 25 mg/d to 100 mg/d; Ravindran 2009 assessed the noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (NARI) atomoxetine, administered in doses of 20 mg/d to 100 mg/d; Van Ameringen 2007 looked at the serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor (SARI) nefazodone, with dosage of 100 mg/d to 600 mg/d; NCT00397722 studied GW876008, at doses of 25 mg/d to 50 mg/d; Tauscher 2010 studied LY686017 at 50 mg/d; Furmark 2005 investigated the NK1 antagonist GR205171, at 4 mL to 100 mL; and Van Vliet 1997 the 5HT1A partial agonist buspirone, at doses of 15 mg/d to 30 mg/d.

Psychiatrists, pharmacists, mental health professionals, and multi‐disciplinary teams of investigators administered the interventions.

Outcomes

Twenty‐three trials assessed the primary efficacy outcome – number of participants with SAnD who responded to treatment – using the Clinical Global Impression – Global Improvement (CGI–I) Scale, whilst 27 other trials assessed this outcome as a secondary measure using the same scale. Forty‐two trials used the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) to assess the reduction of SAnD symptoms, while eight used the Clinical Global Impression ‐ Severity scale (CGI‐S). The most common measures used to assess depression were the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; k = 2), the the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM‐D; k = 12), and the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (k = 10). Thirty trials assessed functional disability using the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS). Post‐treatment follow‐up assessments ranged from two weeks in Tauscher 2010 to 15 months in Oosterbaan 2001. See Characteristics of included studies for more details.

Excluded studies

We excluded 70 studies from the review (see Characteristics of excluded studies). The most common reason we considered trials ineligible was the absence of a placebo comparator (Allsopp 1984; ACTRN12608000363381; Atmaca 2002; Blank 2006; Bystritsky 2005; Clark 2003; Dunlop 2007; Falloon 1981; Gelernter 1991; EUCTR2004‐001894‐24‐DE; Guastella 2009; Hofmann 2006; Krishman 1976; Liappas 2003; Liebowitz 1999; Oosterbaan 1997; Otto 2000; Pecknold 1982; Rickels 2004; Seedat 2003; Simon 2010; Tubaki 2012; ACTRN12609000091202). We also excluded studies with participants under the age of 18 and those with combined populations and certain comorbidities (Dempsey 2009; Grosser 2012; Ionescu 2013). We excluded Dempsey 2009, Gale 2007, and Mangano 2003 because these trials were secondary analyses of previous studies. We also excluded open‐label studies that did not employ a randomised double‐blind placebo‐control study design (Angelini 1989). Twelve early trials with anxiety disorders did not report data separately for patients with SAnD, so we could not include them (Angelini 1989; Coupland 2000; NCT00248612; Greenhill 1999; Heun 2013; Malcolm 1992; Mountjoy 1977; Pine 2001; Schuurmans 2004; Solyom 1973; Solyom 1981; Tyrer 1973). One study focused on neuroendocrine and behavioural responses of SAnD (Shlik 2002). Four studies on brain functioning, with specific reference to the modulation of amygdala‐frontal reactivity and connectivity, were ineligible for inclusion (Dodhia 2014; Gorka 2015; NCT00332046; Phan 2015). A number of trials assessed the effect of medication on individuals with performance anxiety who were not diagnosed with SAnD (Brantigan 1982; Clark‐Elford 2015; Fang 2014; Gates 1985; Gorka 2015; Hartley 1983; James 1977; James 1984; James 1983; Liebowitz 2014; Liden 1974; NCT00308724; NCT00343707; Neftel 1982; Siitonen 1976; Wardle 2012). One excluded study only measured treatment‐emergent side effects (Rynn 2008). Finally, we excluded studies that combined pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy (Donahue 2009; Feifel 2011; Haug 2003; Mortberg 2007; NCT00308724; Prasko 2004; Ravindran 2014; Silverstone 1973; Wardle 2012), as well as studies using herbal treatments (NCT00118833). See Characteristics of excluded studies for more details.

Studies awaiting classification

Thirteen trials are awaiting classification (Asakura 2016; Careri 2015; De la Barquera 2008; Frick 2015; Krylov 1996; NCT00114127; NCT00208741; NCT00215254; NCT00246441; NCT00294346; NCT00485888; NCT00612859; NCT01316302). NCT00294346 conducted a study on the effectiveness of an investigational drug AV608 in subjects with social anxiety disorder (SAnD), using the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) to assess reductions of anxiety symptoms. De la Barquera 2008 assessed clonazepam compared to placebo in patients with social phobia, and Frick 2015 citalopram, GR205171, or placebo. Frick 2015 involved 18 SAnD patients and used the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) to assess symptom severity and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging to assess brain function. Krylov 1996 assessed alprazolam, buspirone, or placebo in 66 patients with social phobia. NCT00485888 investigated the effects of cipralex on the reduction of social phobia, as measured by the LSAS and various other secondary scales, in 71 outpatients aged 18 to 75 years and diagnosed with social phobia. NCT01316302 studied desvenlafaxine (Pristiq) compared to matching placebo over 12 weeks. Sixty‐three patients enrolled, and the primary outcome of symptom severity was measured with the LSAS. Similarly, NCT00208741 investigated Gabitril compared to placebo over 24 weeks with 50 patients using the LSAS and CGI‐C scales as primary outcome measures; NCT00246441 compared paroxetine to placebo over 16 weeks with 42 patients; and NCT00114127 compared duloxetine to placebo for 18 weeks with 28 patients whose symptoms were assessed with the LSAS. The additional trial by NCT00612859 assessed the efficacy and safety of levetiracetam versus placebo for the treatment of generalised SAnD measured by the LSAS. See Characteristics of studies awaiting classification and Figure 1 for more details.

We identified two studies from the update search performed by CCMD's information specialist (Asakura 2016; Careri 2015). We will incorporate these into the next version of the review as appropriate.

Ongoing studies

Five studies are ongoing (NCT00182533; NCT01712321; NCT02083926; NCT02294305; NCT02432703). NCT02083926 will compare ketamine compared placebo (saline) using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), the CGI scale, and the LSAS to determine levels of anxiety severity in SAnD patients, whereas NCT02432703 will compare JNJ‐42165279 to placebo for 12 weeks on the LSAS. NCT00182533 will assess the efficacy of sertraline, and NCT01712321 and NCT02294305 will compare vortioxetine to placebo for treating generalised social anxiety disorder in outpatients. The most common secondary outcome measures include the assessment of depression (NCT00182533; NCT01712321; NCT02294305), anxiety (NCT01712321; NCT02294305), functional disability, and quality of life (NCT00182533). See Characteristics of ongoing studies and Figure 1 for more details.

Risk of bias in included studies

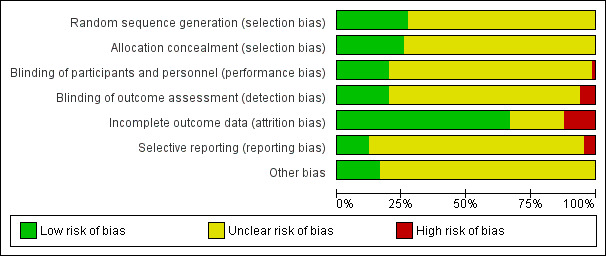

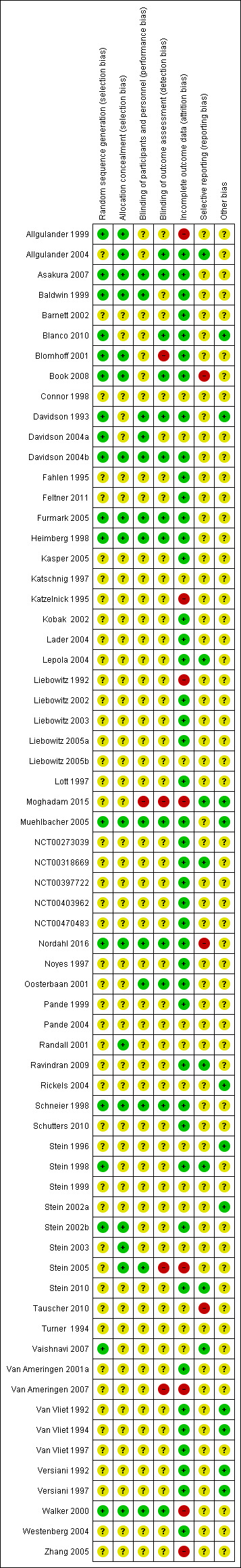

We assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool for allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other potential sources of bias. We classified twelve of the included studies as being at high risk for at least one type of bias (see Figure 2 and Figure 3).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Randomisation

Seventeen of the included studies described the sequence generation as randomised. Allgulander 1999, Blanco 2010, Heimberg 1998, Muehlbacher 2005, and Walker 2000 used tabulated random numbers to randomly assign participants to two groups. In other studies, group assignment was via a computer‐generated urn program (Book 2008; Vaishnavi 2007), block program or randomisation (Baldwin 1999; Davidson 2004b; Furmark 2005; Nordahl 2016; Stein 1998), or a computer‐generated randomisation list (Blomhoff 2001; Davidson 1993; Stein 2002b). Asakura 2007 used a randomisation scheme by double‐dummy method, whereas Davidson 2004a and Schneier 1998 determined randomisation through the sponsor of the central source (e.g. pharmacy) or through a data manager with no patient contact. We classified all these studies as being at low risk for selection bias, while we designated the risk of bias as unclear in the remaining studies.

Allocation concealment

We could only classify 17 of the 66 trials included in the review as being at low risk for allocation concealment from their description of the method of allocation. A pharmacist or sponsor who prepared and supplied the study medication maintained allocation concealment in nine trials (Allgulander 1999; Allgulander 2004; Asakura 2007; Baldwin 1999; Blomhoff 2001; Book 2008; Nordahl 2016; Randall 2001; Walker 2000). Other studies maintained concealment with the use of sealed envelopes (Blomhoff 2001; Furmark 2005; Schneier 1998), double‐blind packaging (Asakura 2007; Davidson 2004b; Stein 2002b; Stein 2003; Walker 2000), label coding for each participant or numbered box (Davidson 2004b; Muehlbacher 2005; Schneier 1998; Stein 2005; Stein 2003), and cohorts of patients randomly intermixed (Heimberg 1998).

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel

We classified 13 studies included in the review as being at low risk of performance bias, as participants and personnel were explicitly described as blinded in the study report (Asakura 2007; Baldwin 1999; Davidson 1993; Davidson 2004a; Davidson 2004b; Furmark 2005; Heimberg 1998; Muehlbacher 2005; Nordahl 2016; Oosterbaan 2001; Schneier 1998; Stein 2005; Walker 2000). In Oosterbaan 2001 and Schneier 1998, participants and therapists or independent evaluators guessed post‐test whether medication or placebo had been administered. Correct classifications did not differ from chance. We classified one trial as being at high risk because it provided no information on blinding participants or personnel, nor did investigators describe the study as double‐blind (Moghadam 2015). We classified risk of bias for the remaining trials as unclear, despite investigators describing them in the study reports as double‐blinded, as they did not specify the actual parties blinded.

Blinding of outcome assessors

We classified 13 of the studies included in the review as being at low risk of detection bias, as the study reports explicitly described outcome assessors as blinded in the study report (Allgulander 2004; Asakura 2007; Blanco 2010; Book 2008; Davidson 1993; Davidson 2004b; Furmark 2005; Heimberg 1998; Muehlbacher 2005; Nordahl 2016; Oosterbaan 2001; Schneier 1998; Walker 2000). We classified Blomhoff 2001, Stein 2005, and Van Ameringen 2007 as being at high risk, as these studies reported that outcome assessors were not blinded to treatment, and Moghadam 2015 because authors provided no information to determine if outcome assessors were blinded, nor if the study was double blind. We classified the remaining studies as being at unclear risk.

Incomplete outcome data

Fourteen studies failed to provide sufficient information to determine whether the medication and placebo groups were comparable with respect to dropout proportions, or in terms of the demographic and clinical characteristics of those who withdrew (Connor 1998; Davidson 2004a; Katschnig 1997; Liebowitz 2005b; Pande 2004; Randall 2001; Rickels 2004; Stein 1996; Stein 1999; Stein 2002a; Stein 2003; Tauscher 2010; Turner 1994; Vaishnavi 2007). We rated the risk of attrition bias as unclear for these trials. We observed substantial differences in the proportion of study dropouts between the medication and placebo groups in Allgulander 1999, Katzelnick 1995, Liebowitz 1992, Moghadam 2015; Stein 2005, Van Ameringen 2007, and in the maintenance treatment design that Walker 2000 and Zhang 2005 employed, justifying a rating of high risk. We rated the remaining 44 studies as being at low risk for this domain, on the basis of comparable dropout rates in each comparison group and no difference in the demographic characteristics. Overall, the total dropout rate was 25% across all medications compared to placebo (with the exclusion of one trial of paroxetine, to give preference to the experimental drug that is least represented in the data set). We assessed intention‐to‐treat data for all outcomes in 11 studies and used LOCF (k = 46), observed cases (k = 9) and mixed‐effect models (k = 3) to account for missing data in the rest of the trials. Thirteen studies did not specify how they addressed the issue of missing data.

Selective reporting

It was unclear whether selective reporting took place in 55 trials because the study protocols were not available for the study. We rated eight studies as being at low risk for selective reporting because authors reported on all outcomes as specified in their respective trial protocols (Allgulander 2004; Lepola 2004; Moghadam 2015; NCT00318669; Ravindran 2009; Stein 1998; Stein 2010; Vaishnavi 2007). In Book 2008, Nordahl 2016, and Tauscher 2010, the pre‐specified secondary outcomes in the protocol did not appear in the study report, meriting a classification of high risk.

Other potential sources of bias

We classified 11 studies as being at low risk for other potential sources of bias (Blanco 2010; Davidson 1993; Moghadam 2015; Muehlbacher 2005; Rickels 2004; Stein 1996; Stein 2002a; Van Vliet 1992; Van Vliet 1994; Versiani 1992; Versiani 1997). We rated the risk of other bias for the remaining studies as unclear due to industry involvement, whether through funding or provision of study medication.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8; Table 9; Table 10; Table 11; Table 12; Table 13; Table 14; Table 15; Table 16

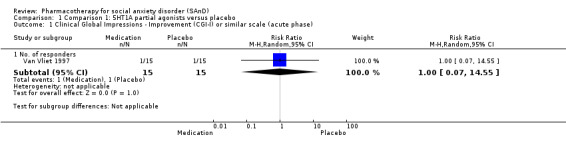

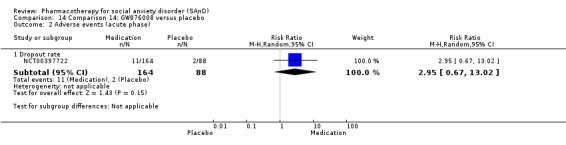

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Comparison 1: 5HT1A partial agonists versus placebo for social anxiety disorder (SAnD).

| Comparison 1: 5HT1A partial agonists versus placebo for social anxiety disorder (SAnD) | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with SAnD Settings: outpatient settings Intervention: 5HT1A partial agonists Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| With placebo | With 5HT1A partial agonists | |||||

| Global Impressions scale change item (CGI‐I or similar): no. of responders (acute phase) | Study population | RR 1.00 (0.07 to 14.55) | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | There was no evidence of an effect on the number of participants in the 5HT1A partial agonist group compared to the placebo group who responded 'Very Much Improved' or 'Much Improved' on the CGI‐I scale (P = 1.00). | |

| 67 per 1000 | 67 per 1000 (5 to 970) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 67 per 1000 | 67 per 1000 (5 to 975) | |||||

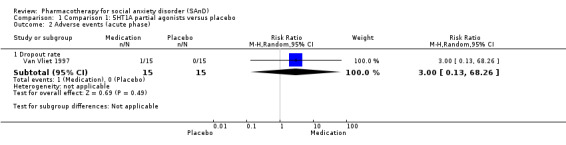

| Dropouts due to adverse events (acute phase) | Study population | RR 3.00 (0.13 to 68.26) | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | Dropout rates due to adverse events were low in the 5HT1A partial agonist group (1/30, 3%). No participants withdrew from the placebo group. | |

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

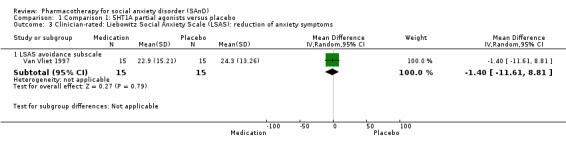

| Reduction of of anxiety symptoms ‐ Clinician‐rated: LSAS avoidance subscale | The mean anxiety score for the control group was 24.3 | The mean reduction of anxiety symptoms (clinician‐rated: LSAS avoidance) in the intervention groups was 1.4 points lower (11.61 lower to 8.81 higher) | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c | The mean LSAS avoidance anxiety score for the 5HT1A partial agonist intervention group was 22.9 which suggests 'low' social phobia. | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CGI‐I: Clinical Global Impressions Improvement scale; LSAS: Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale;RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to serious risk of bias (concerns with randomisation procedures). bDowngraded two levels due to very serious imprecision (small sample size, few events and wide confidence interval). cDowngraded two levels due to very serious imprecision (small sample size and wide confidence interval). dResponse is defined as the number of participants with SAnD who responded to treatment, as assessed by the CGI‐I or similar.

Summary of findings 2. Comparison 2: anticonvulsants/GABAs versus placebo for social anxiety disorder (SAnD).

| Comparison 2: anticonvulsants/GABAs versus placebo for social anxiety disorder (SAnD) | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with SAnD Settings: outpatient settings Intervention: anticonvulsants/GABAs Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| With placebo | With anticonvulsants/GABAs | |||||

| Global Impressions scale change item (CGI‐I or similar): no. of responders (acute phase) | Study population | RR 1.60 (1.16 to 2.20) | 532 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | There was evidence of benefit on the number of participants with SAnD who responded to treatment (P = 0.004). A RR score greater than 1 and 95% CI that does not overlap with 1 indicates that there were a statistically significantly greater number of people in the anticonvulsant/GABA groups compared to the placebo groups who responded 'Very Much Improved' or 'Much Improved' on the CGI‐I scale. | |

| 221 per 1000 | 353 per 1000 (256 to 486) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 217 per 1000 | 347 per 1000 (252 to 477) | |||||

| Dropouts due to adverse events (acute phase) | Study population | RR 2.90 (0.92 to 9.14) | 532 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | Dropout rates due to adverse events were high in the anticonvulsant/GABA groups (64/369, 17%) relative to placebo (9/163, 6%). | |

| 55 per 1000 | 160 per 1000 (51 to 505) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 87 per 1000 | 252 per 1000 (80 to 795) | |||||

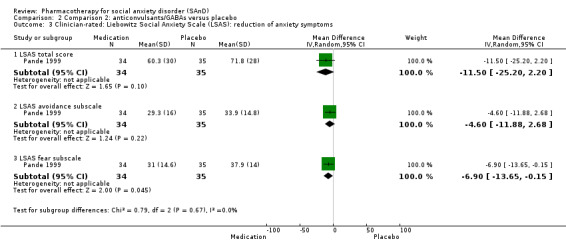

| Reduction of of anxiety symptoms ‐ Clinician‐rated: LSAS total score | The mean anxiety score for the control group was 71.8 | The mean reduction of anxiety symptoms (clinician‐rated: LSAS total score) in the intervention groups was 11.50 lower (25.20 lower to 2.20 higher) | 69 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,d | The mean LSAS total anxiety score for the anticonvulsant/GABA intervention group was 60.3 which suggests 'moderate' social phobia. | |

| Reduction of of anxiety symptoms ‐ Clinician‐rated: LSAS avoidance subscale | The mean anxiety score for the control group was 33.9 | The mean reduction of anxiety symptoms (clinician‐rated: LSAS avoidance) in the intervention groups was 4.60 points lower (11.88 lower to 2.68 higher) | 69 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,d | The mean LSAS avoidance anxiety score for the anticonvulsant/GABA intervention group was 29.3 which suggests 'low' social phobia. | |

| Reduction of of anxiety symptoms ‐ Clinician‐rated: LSAS fear subscale | The mean anxiety score for the control group was 37.9 | The mean reduction of anxiety symptoms (clinician‐rated: LSAS fear) in the intervention groups was 6.90 points lower (13.65 lower to 0.15 lower) | 69 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,d | The mean LSAS fear anxiety score for the anticonvulsant/GABA intervention group was 31.0 which suggests 'low' social phobia. | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CGI‐I: Clinical Global Impressions Improvement scale; LSAS: Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale;RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to serious risk of bias (concerns with randomisation procedures). bDowngraded two levels due to moderate heterogeneity (I2 of 56%). cDowngraded two levels due to very serious imprecision (few events and wide confidence interval). dDowngraded two levels due to very serious imprecision (wide confidence interval). eResponse is defined as the number of participants with SAnD who responded to treatment, as assessed by the CGI‐I or similar.

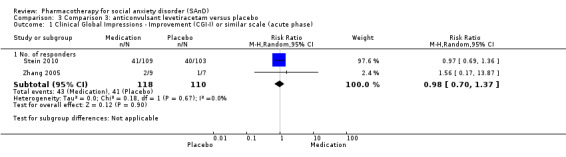

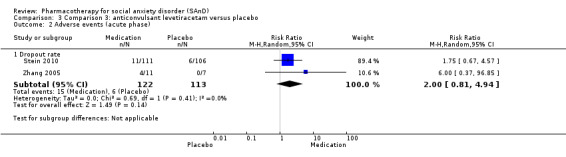

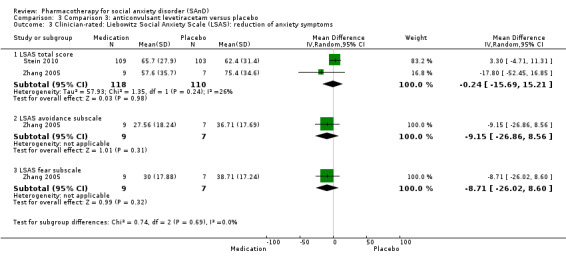

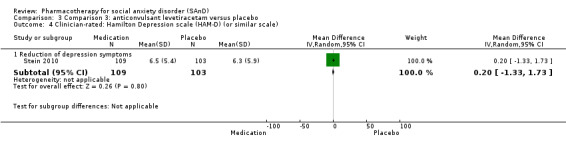

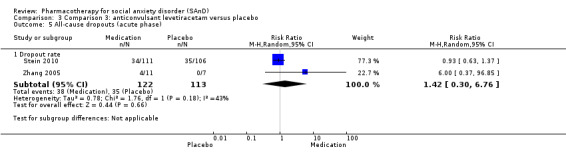

Summary of findings 3. Comparison 3: anticonvulsant levetiracetam versus placebo for social anxiety disorder (SAnD).

| Comparison 3: levetiracetam versus placebo for social anxiety disorder (SAnD) | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with SAnD Settings: outpatient settings Intervention: other anticonvulsants Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| With placebo | Wtih levetiracetam | |||||

| Global Impressions scale change item (CGI‐I or similar): no. of responders (acute phase) | Study population | RR 0.98 (0.70 to 1.37) | 228 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | There was no evidence of an effect on the number of participants in the anticonvulsant levetiracetam groups compared to the placebo groups who responded 'Very Much Improved' or 'Much Improved' on the CGI‐I scale (P = 0.90). | |

| 373 per 1000 | 365 per 1000 (261 to 511) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 266 per 1000 | 261 per 1000 (186 to 364) | |||||

| Dropouts due to adverse events (acute phase) | Study population | RR 2.00 (0.81 to 4.94) | 235 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | The proportion of dropouts due to adverse events was high in participants receiving the anticonvulsant levetiracetam (15/122, 12%) relative to placebo (6/113, 5%). There was no evidence of a difference between the number of participants that dropped out due to adverse events (P = 0.14). | |

| 53 per 1000 | 106 per 1000 (43 to 262) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 28 per 1000 | 56 per 1000 (23 to 138) | |||||

| Reduction of of anxiety symptoms ‐ Clinician‐rated: LSAS total score | The mean anxiety score ranged across control groups from 62.4 to 75.4 | The mean reduction of anxiety symptoms (clinician‐rated: LSAS total score) in the intervention groups was 0.24 points lower (15.69 lower to 15.21 higher) | 228 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c | The mean LSAS total anxiety score for the anticonvulsant levetiracetam intervention groups ranged from 55 to 65 which suggests 'moderate' social phobia. | |