Abstract

Several studies have demonstrated the neuromodulating function of oxytocin (OT) in response to anxiogenic stimuli as well as its potential role in the pathogenesis of depression. Consequently, intranasal OT (IN-OT) has been proposed as a potential treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders. The present systematic review aimed to summarize the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the effect of IN-OT on anxiety and depressive symptoms. Overall, 15 studies were included, involving patients with social anxiety disorders (7 studies), arachnophobia (1), major depression (3) or post-natal depression (4), and mainly evaluating single-dose administrations of IN-OT. Results showed no significant effects on core symptomatology. Five crossover studies included functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation: one trial showed reduced amygdala hyper-reactivity after IN-OT in subjects with anxiety, while another one showed enhanced connectivity between amygdala and bilateral insula and middle cingulate gyrus after IN-OT in patients but not in healthy controls. More studies are needed to confirm these results. In conclusion, up to date, evidence regarding the potential utility of IN-OT in treating anxiety and depression is still inconclusive. Further RCTs with larger samples and long-term administration of IN-OT are needed to better elucidate its potential efficacy alone or in association with standard care.

Keywords: Oxytocin, Depression, Anxiety, Social behavior, Functional magnetic resonance imaging

INTRODUCTION

Oxytocin (OT) is a neuropeptide primarily synthesized in the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of hypothalamus. OT is released in the systemic circulation by the posterior pituitary gland, acting as a hormone and regulating a range of physiological functions. Moreover, through the release in the central nervous system, OT acts as a neuromodulator on multiple brain regions.1) Several studies have tried to explore and characterize the OT system and its implications in animal and human social behavior. OT, in fact, is mainly known for its role in facilitating trust and attachment between individuals. It has been shown to mediate several human social behaviors, such as mother-infant bonding,1–3) mind-reading,4,5) empathy,6) and gossiping.7) The administration of intranasal OT (IN-OT) in healthy and clinical populations seemed to improve aspects of social cognition, including emotion recognition8,9) and theory of mind.10–12) A large number of studies have also investigated the role of peripheral OT as a potential biomarker of psychiatric disorders, with highly heterogeneous findings.13)

In addition to the crucial role played in modulating human social behavior, OT seems to influence a more complex range of neurophysiological processes and behaviors.14) For instance, there is consensus that OT modulates anxiety, aggression, and the stress/fear response to social stimuli.15) In response to anxiogenic stimuli, OT is released in specific brain regions,16) mainly in the paraventricular nucleus and amygdala,16) which are involved in modulating the physiological stress response. Of note, anxiety-related behaviors and emotional responsiveness to stressful stimuli may be reduced during periods of high activity of the endogenous OT system, such as lactation17) and sexual activity.18,19) Moving to pathological anxiety conditions, researchers have suggested a possible relationship between peripheral OT levels, oxytocin-receptor gene polymorphisms, and generalized anxiety disorder. In particular, basal plasma OT concentrations were found to depend upon the mental health state and gender of the test person.20)

Analogously, OT produces antidepressant effects in animal models of depression21) and its deficit may be involved in the pathophysiology of depression in humans.22) The antidepressant-like effect of OT seems to be mediated by the activation of a mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade and the subsequent induction of brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression, with neurogenesis and neuroplasticity.21) It has also been hypothesized that OT itself might not diminish symptoms in clinically depressed individuals, but could plausibly work as an adjunct to antidepressant treatments, or in treating particular aspects of depressive disorders by reducing the salience of potentially ambiguous and threatening social stimuli.23,24) Additionally, OT has been identified as a potential mediator of postpartum depression.25) Genetic analyses indicate that postpartum depression may be mediated by epigenetic variation in OT receptor expression,26) and symptoms of depression are associated with lower OT activity.27)

Given the potential role of OT in the development of anxiety and depressive disorders, several studies evaluated the effect of synthetic IN-OT in psychiatric patients. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no up-to-date reviews summarizing the results so far obtained with a systematic approach. With the present work, we aimed at systematically reviewing all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the effect of IN-OT in individuals affected by anxiety or depressive disorders.

METHODS

The present systematic review followed the PRISMA Statement guidelines.28)

Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was performed in Web of Knowledge™ (including KCL Korean Journal Database, MEDLINE, Russian Science Citation Index, and SciELO Citation Index), PsycINFO, EMBASE, and CINAHL from inception to December 2017.

Two authors (FD and LF) conducted a computerized search using the following search terms: (oxytocin) AND (psychosis OR psychotic OR schizo* OR depression OR depressive OR mood OR bipolar OR anxi* OR phobi* OR obsessi* OR compulsive OR OCD OR “post-trauma*”; OR PTSD OR autis* OR asperger OR anorex* OR bulimi* OR “eating disorder”) AND (RCT OR random* OR trial OR experimental). Additionally, reference lists from all recovered systematic reviews and meta-analyses were hand-searched for further relevant references.

Eligibility Criteria

Final inclusion was based on the following criteria:

Participants: Individuals of any age diagnosed with anxiety disorders or depressive disorders (both in acute phase or in remission), according to international valid diagnostic criteria. Trials involving patients with post-traumatic stress disorder were excluded, since it is included in a separate category of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition29);

Intervention: IN-OT, single or multiple administration, at any dosage;

Comparison: any comparison treatment (i.e., placebo, no treatment, or other types of intervention);

Outcome: any outcome;

Study design: experimental design with randomization (including RCTs), both parallel group and crossover.

Data Extraction

Three independent researchers (FD, GG, and AM) examined all titles and abstracts and obtained full texts of potentially relevant papers. Working independently and in duplicate, the same authors read the papers and determined whether they met inclusion criteria. Two authors (FD and GG) assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias tool.30) Any discrepancy was solved by discussion with another reviewer (LF).

We extracted data using a standardized format including study characteristics, sample characteristics, intervention, control, outcome and main findings.

RESULTS

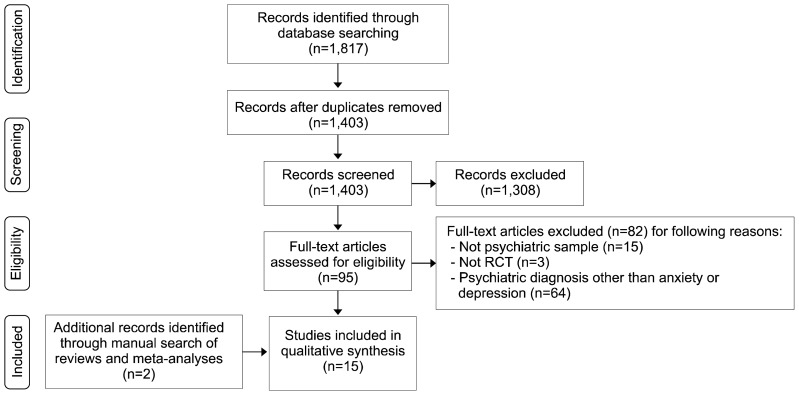

The search provided 1,817 citations (Web of Science, 829; PsycINFO, 399; Embase, 505; CINHAL, 84). After duplicate publications removal, 1,403 reports were screened by title and abstract. Ninety-five publications were obtained for detailed evaluation and reasons for exclusion were reported in PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1). Two additional studies were retrieved after a manual search of reviews and meta-analyses. Overall, 8 studies on anxiety and 7 on depression were found. The main characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1 (anxiety) and Table 2 (depression).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow-diagram of selection process.

RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Table 1.

Characteristics of randomized controlled trials evaluating the effect of intranasal oxytocin (OT) on patients with anxiety disorders

| First author, year | Study design | Randomized/OT, control | Sex, male | Age (yr) | Psychiatric diagnosis | OT dose/duration | Outcome (measures) | Time of outcome assessment | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acheson, 201538) | Parallel | 23/10, 13 | 5 (21.7) | 29.5 | Arachnophobia | 24 IU/SA | Self-report phobia (BAT, SPQ, FSQ). Clinical evaluation (CGI-I, CGI-S). Credibility/Working alliance (m-WAI). |

1 wk and 1 mo post-treatment | No significant differences for any outcome. |

| Dodhia, 201434) | Crossover | 18 | 18 (100) | 29.4 (19–55) | GSAD | 24 IU/SA | Resting-state fMRI. | 45 min post-treatment | OT enhanced rsFC of the left and right amygdala with rostral anterior cingulate cortex/mPFC. |

| Fang, 201431) | Parallel | 54/27, 27 | 54 (100) | 24.4 (18–45) | SAD | 24 IU/SA | Tasks (Cyberball, Modified Posner Task). Attachment style (IPSM, ECR). Mood and anxiety (SIAS, PANAS). | 45 min post-treatment | Among participants who received OT, only individuals with low attachment avoidance displayed more social affiliation and cooperation, and only those with high attachment avoidance showed faster detection of disgust and neutral faces. |

| Fang, 201732) | Parallel | 54/27, 27 | 54 (100) | 24.4 (18–45) | SAD | 24 IU/SA | Task (“Pay-it-forward” EEfRT). Attachment style (ECR). Mood and anxiety (SIAS). | 60 min post-treatment | Among participants who received OT, only individuals with low levels of social interaction anxiety showed an increased other-oriented reward motivation. No main effect of OT on social behavior. |

| Gorka, 201535) | Crossover | 18 | 18 (100) | 29.8 | GSAD | 24 IU/SA | fMRI while performing the EFMT. | 45 min post-treatment | Within individuals with GSAD, OT enhanced functional connectivity between the amygdala and the bilateral insula and middle cingulate/dorsal anterior cingulate gyrus during the processing of fearful faces. |

| Guastella, 200933) | Parallel | 25/12, 13 | 25 (100) | 42.3 (25–65) | SAD | 24 IU/once weekly for 4 wk plus exposure therapy (public speech) | Self-report anxiety (SPAI, LSAS, BFNE, LIS). Appraisals of speech appearance and performance (AS, SPQ-2, Likert scale). | Immediately after last administration; 1 mo post-treatment. Exposure therapy outcome: 45 min after each administration | Participants administered with OT showed improved positive evaluations of appearance and speech performance as exposure treatment sessions progressed. No differences in SAD symptoms from pre- to post-treatment. |

| Labuschagne, 201036) | Crossover | 18 | 18 (100) | 29.39 (18–55) | GSAD | 24 IU/SA | fMRI while performing the EFMT. Mood (VAMS). |

45 min post-treatment | OT attenuated the heightened amygdala reactivity to fearful faces in the GSAD group, such that the hyperactivity observed during the placebo session was no longer evident following OT. No effects of OT on the VAMS factors. |

| Labuschagne, 201237) | Crossover | 18 | 18 (100) | 29.39 (18–55) | GSAD | 24 IU/SA | fMRI while performing an emotion recognition task. Mood and anxiety (POMS, STAI). | 45 min post-treatment | In response to sad vs. neutral faces, OT attenuated regions hyperactive in the placebo condition including in several clusters in bilateral mPFC and ACC. OT reduced activity in bilateral premotor, right parietal and left visual cortices. No significant effects on mood and anxiety. |

Values are presented as number only, number (%), or mean age (range).

ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; AS, appearance scale; BAT, behavioral approach task; BFNE, Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale; CGI, clinical global impression; CGI-I, CGI-improvement; CGI-S, CGI-severity; ECR, Experience in Close Relationships Inventory; EEfRT, Effort Expenditure for Rewards Task; EFMT, Emotional Face Matching Task; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; FSQ, Fear of Spider Questionnaire; GSAD, generalized social anxiety disorder; IPSM, Interpersonal Sensitivity Measure; LIS, Life Interference Scale; LSAS, Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale; mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; m-WAI, Working Alliance Inventory-Client-Short Form; PANAS, Positive and Negative Affective Scales; POMS, Profiles of Mood Scale; SA, single administration; SAD, social anxiety disorder; SIAS, Social Interaction and Anxiety Scale; SPAI, Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory; SPQ, Spider Phobia Questionnaire; SPQ-2, Speech Performance Questionnaire 2; STAI, Spielberg Trait-State Anxiety Inventory; VAMS, Visual Analogue Mood Scale.

Table 2.

Characteristics of randomized controlled trials evaluating the effect of intranasal oxytocin (OT) on patients with depressive disorders

| First author, year | Study design | Randomized/OT, control | Sex, male | Age (yr) | Psychiatric diagnosis | OT posology/duration | Outcome (measures) | Time of outcome assessment | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clarici, 201560) | Parallel | 16/5, 11 | 0 | 36.5 (33–41) | PND | 16 IU plus psychodynamic psychotherapy/once daily for 12 wk | Depressive symptoms (EPDS, HDRS) Personality (ANPS, SWAP) |

End of treatment | No significant differences. |

| Domes, 201666) | Parallel | 43/22, 21 | 18 (42) | 46.9 | Depressive episode, recurrent depressive disorder, dysthymia | 24 IU/SA | Reaction time, attention (Dot-probe task) | 60 min post-treatment | OT reduced the initial allocation of attention towards angry faces and increased sustained attention towards happy faces |

| MacDonald, 201364) | Crossover | 18 | 18 (100) | 43.6 (20–64) | MDD | 40 IU/SA plus a psychotherapy session | Vital signs (HR, BP, salivary cortisol) Anxiety (STAI, PANAS) Emotion recognition (RMET) Behavioral signs (ECSI, eye contact) |

70–75 min post-OT treatment | OT increased subjective anxiety. No significant differences in behavioral and vital signs. |

| Mah, 201363) | Crossover | 25 | 0 | 28.2 (19–38) | PND | 24 IU/SA | Mood (SAM) Verbal fluency (COWAT) Expressed emotion (FMSS) |

45 min post-treatment | After OT mothers with PND commenced their description of their baby more negatively but rated the quality of their relationship with their babies as more positive. After OT mood was rated as poorer. No effect on verbal fluency. |

| Mah, 201567) | Crossover | 16 | 0 | 26.5 (19–33) | PND | 24 IU/SA | Enthusiastic Stranger Paradigm (protectiveness, gaze duration) | 45 min post-treatment | In OT condition mothers were more protective of their baby in the presence of a stranger, but their gaze duration was reduced. |

| Mah, 201768) | Crossover | 25 | 0 | 28.2 (19–38) | PND | 24 IU/SA | Maternal sensitivity (play video-recorded session) Cry paradigm |

45 min post-treatment | Mothers with PND rated a naturalistic newborn cry as more urgent after OT. In OT condition subjects were more likely to choose a harsh caregiving strategy in response to the cry sound. No effect of OT on observed maternal sensitivity. |

| Pincus, 201065) | Crossover | 10 | 10 (100) | 35.5 (26–60) | MDD | 20 IU/SA | fMRI while performing a paradigm (RMET, reaction time and motor-cued response) | 10 min post-treatment | During RMET, there was significant activation with OT compared to placebo in bilateral superior temporal gyrus, right insula, right precentral gyrus, bilateral cingulate gyri, left anterior cingulum, left supramarginal gyrus, right inferior frontal gyrus, right superior and middle frontal gyri. On motor cues, OT led to significant increases in bilateral superior and medial frontal gyri. No differences in gender identifications. |

Values are presented as number only, number (%), or mean age (range).

ANPS, Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales; BP, blood pressure; COWAT, Controlled Oral Word Association Test; ECSI, Ethological Coding System for Interviews; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; FMSS, Five Minute Speech Sample; HDRS, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; HR, heart rate; MDD, major depressive disorder; PANAS, Positive and Negative Affective Scales; PND, postnatal depression; RMET, Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test; SA, single administration; SAM, Self-Assessment Manikin; STAI, Spielberg Trait-State Anxiety Inventory; SWAP, Shedler-Westen Assessment Procedure.

Anxiety Disorders

Characteristics of the included studies

Eight studies regarding anxiety disorders were retrieved. Characteristics of the included trials are depicted in Table 1. Three studies recruited subjects with social anxiety disorder,31–33) four studies recruited subjects with generalized social anxiety disorder (GSAD)—a subtype of social anxiety disorder34–37)—and one study included subjects with arachnophobia.38) In total, 226 patients (120 patients if considering overlapping samples) with a mean age of 29.8 years (range, 18–65 years) were randomized to IN-OT treatment. Of note, Fang et al. (2014),31) Fang et al. (2017),32) Dodhia et al. (2014),34) Gorka et al. (2015),35) Labuschagne et al. (2010)36) and Labuschagne et al. (2012)37) reported results of trials with overlapping samples, but focusing on different outcomes and outcome measures. Samples were mostly composed by males (92.0%). In all studies, apart from one, treatment was a single dose administration of IN-OT. Guastella et al. (2009)33) tested a weekly administration of IN-OT for four weeks.

Effect of IN-OT on mood and anxiety

Overall, no significant differences were found in mood and anxiety after the administration of IN-OT in patients affected by anxiety disorders. Anxiety symptoms were evaluated in three studies. Only self-report measures were used. Acheson et al.38) evaluated arachnophobia symptoms through the Spider Phobia Questionnaire (SPQ) 39) and the Fear of Spider Questionnaire (FSQ) 40) in a double-blind RCT. A clinical evaluation made through the Clinical Global Impression (CGI)41) scales confirmed the lack of improvement after the treatment compared to placebo group. Guastella et al.33) administered four different self-report scales for anxiety in a parallel group RCT: the Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory (SPAI),42) the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS),43) the Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale (BFNE)44) and the Life Interference Scale (LIS).45) The authors did not find any anxiolytic effect of IN-OT compared to placebo. Finally, Labuschagne et al.37) tested the effect of IN-OT in a crossover trial, using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI).46) Study results were negative, with no positive effect of IN-OT compared to placebo. Mood was evaluated in three studies. In particular, a parallel RCT from Fang et al. (2014)31) used the Positive and Negative Affective Scale (PANAS),47) finding that OT did not significantly reduce negative or positive mood compared to placebo. Moreover, in the two crossover trials designed by Labus-chagne et al.,36,37) mood was evaluated by means of the Visual Analogue Mood Scale (VAMS)48) in the paper published in 2010, and by means of the Profiles of Mood Scale (POMS) in the work published in 201249): both studies did not find positive effects of OT (compared to placebo) on mood symptoms.

Effects of IN-OT on behavioral tasks

Three double-blind RCTs analyzed the effect of IN-OT on behavioral tasks. In the study published in 2014, Fang et al.31) used the Cyberball task,50,51) a computerized ball-tossing game designed to simulate and manipulate rejection, and the Posner task52,53) in order to measure attentional engagement toward and disengagement from social threat cues. In the trial published in 2017, Fang et al.32) used a modified version of the effort expenditure for rewards task to assess self- vs. other-directed reward motivation (Effort Expenditure for Rewards Task, EEfRT).54) Guastella et al.33) used two self-report measures of speech performance after each participant of the study gave a speech in front of group members about increasingly difficult topics. The first was the Appearance Scale,45) the second was the Speech Performance Questionnaire-2 (SPQ-2).55) Overall, no main effect of OT on social behavior was found compared to placebo. Nevertheless participants administered with OT showed an increased other-oriented reward motivation,31) more social affiliation and cooperation,32) and improved positive evaluations of appearance and speech performance.33) More details are described in Table 1.

Changes induced by IN-OT in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)

Individuals affected by GSAD show anomalies in functional connectivity between different brain regions such as amygdala, prefrontal cortex (PFC) and anterior cingulated.56) These regions are respectively involved in fear response, self-reference, and a wide spectrum of emotional and attentional processes.57) The fMRI changes after IN-OT were evaluated in four studies, which share the same sample of 18 subjects with GSAD and 18 healthy controls.34–37) Both groups underwent a cross trial with a single intranasal administration of 24 IU of OT and placebo, being scanned after each treatment at rest and during the administration of the Emotional Face Matching Task (EFMT). The well-known left amygdala hyper-reactivity to fearful faces58) was reduced after IN-OT in GSAD group compared to placebo, while improving the subjects’ calmness score.36) Accordingly, increased reactivity to sad faces in medial PFC and anterior cingulated, observed at the baseline/placebo condition in these patients, was reduced after a single dose of OT. This effect was not concomitant with an improvement in mood or state of anxiety.37)

The strong connectivity at rest between amygdala and medial PFC was observed for the first time in healthy subjects.59) Dodhia et al.34) observed a reduced resting state functional connectivity between left and right amygdala with the anterior cingulate/medial PFC in the GSAD group, that enhanced after IN-OT. Connectivity between the amygdala and the bilateral insula and middle cingulate gyrus during the processing of fearful faces of the EFMT was enhanced after IN-OT administration in patients but not in healthy controls in Gorka et al.35) These findings should be interpreted with caution due to the absence of replication studies, the small sample size and the modest correlation between clinical scales and fMRI results.

Side effects

Two of the included studies analyzed adverse events.31,33) According to Fang et al.,31) 37% of all participants reported adverse events, of which the most common were: jitteriness/restlessness (17%), anxiety/nervousness (11%), dry mouth (7%), and sedation/drowsiness (7%); there was no difference between IN-OT and placebo groups in the frequency and nature of reported adverse events.31) Guastella et al.33) showed that four OT and three placebo participants reported side effects at each treatment session. The most common side effects, over the four weeks, were: feeling relaxed, light headed, anxious and fuzzy sensations.

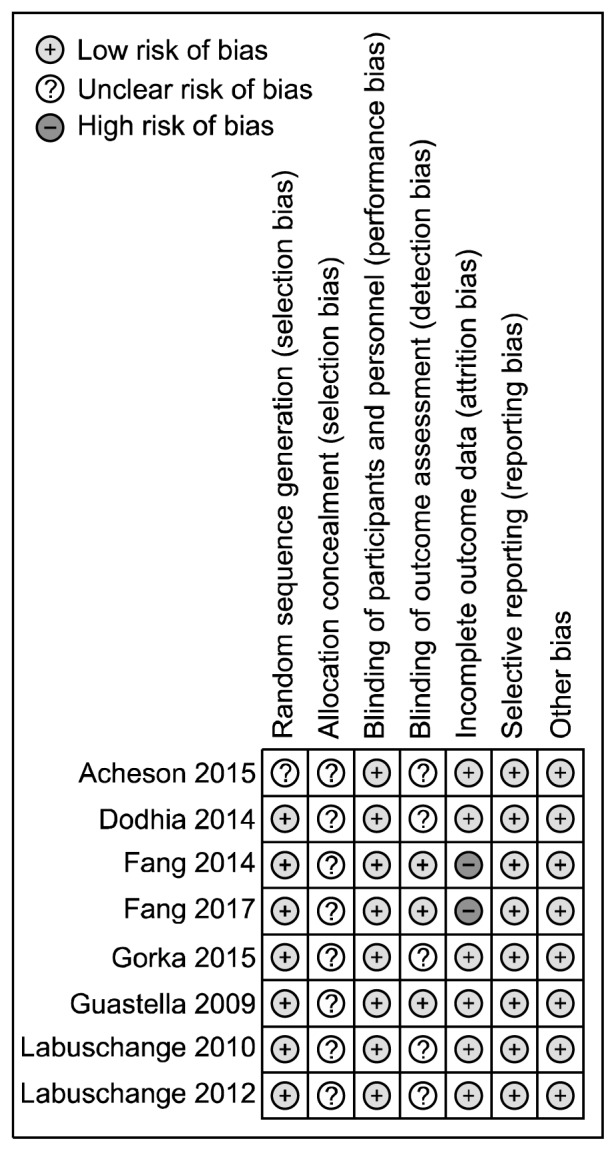

Risk of bias assessment of the included studies

A summary report of the risk of bias is presented in Figure 2. Seven studies had adequate random sequence generation,31–37) while the other one did not provide sufficient information, and so it was rated as unclear.38) All trials had uncertain allocation concealment. All studies had blinding of participants and personnel. Three studies described all measures used to blind outcome assessors31–33); the other five studies didn’t described in sufficient details blinding of outcome assessment.34–38) Two studies had incomplete outcome data31,32); the other ones had a low risk of attrition bias.33–38) Risks of selective reporting were low in all trials. According to the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool, all the included studies should be considered at ‘uncertain risk of bias’.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias assessment of included studies evaluating intra-nasal oxytocin in anxiety disorders.

Depressive Disorders

Characteristics of the included studies

Seven studies evaluating the effects of IN-OT in patients with depressive disorders were included. Trials characteristics are reported in Table 2. Four of seven studies recruited subjects with postnatal depression (PND), while the remaining three studies recruited subjects with major depressive disorder (MDD). In total, 153 patients (112 patients if considering overlapping samples) with depressive disorders were included in the selected studies. In particular, 71 patients (78.87% males) were diagnosed with MDD and 41 women diagnosed with PND. Mean age was 33.65 years (range, 19–60 years). All included studies evaluated the effects of a single-dose administration of IN-OT at different dosages, a part from Clarici et al. (2015)60) that considered a daily administration of IN-OT for 12 weeks.

Effect of IN-OT on mood and anxiety

Clarici et al.60) evaluated specifically depressive symptoms after a daily administration of OT for 12 weeks, associated with psychodynamic psychotherapy. Outcome measures of the parallel RCT were the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)61) and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HDRS).62) Overall, no significant differences in depressive symptoms were found between OT and placebo. Mah et al.63) used the Self-Assessment Manikin to rate the emotional reactions of mother with PND after the administration of a single-dose of IN-OT. Surprisingly, after OT, the mood was globally rated as poorer, but the author found no significant different effects of OT in respect of placebo. Subjective anxiety was also evaluated in a crossover study,64) using STAI as outcome measure. Anxiety scores increased during a psychotherapy session under OT while remained stable under placebo.63)

Effects of IN-OT on social cognition

Two of the selected studies examined whether IN-OT improved performance at the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET). One crossover trial found that OT significantly improved the score at the RMET in a population of outpatients with MDD64) compared to placebo. Another crossover study confirmed that OT improved RMET in healthy individuals while depressed patients showed slower reaction times after controlling for placebo and pre-drug performance.65) In their parallel group RCT, Domes et al.66) reported an increased adherence to positive social signals and decreased allocation of attention to aversive social signals after OT treatment in chronic depression.

Two crossover studies63,67) explored the effects of IN-OT administration on cognition, expressed emotion and caregiving in mothers with diagnosis of PND. In the paper published in 2013, the authors showed an improvement of mother’s perception of the relationship with their baby, although initially they described their babies as difficult (Five Minute Speech Sample, Controlled Oral Word Association Test, Self-Assessment Manikin).63) Furthermore, mothers with PND were more protective in their response to an intrusive stranger (Enthusiastic Stranger Paradigm).67) OT conditioned the perception of the infant cry as more rgent, determining a harsh caregiving strategy in response; however, it had no effect on maternal sensitive interaction with babies (Conflict Tactics Scale for Parent and Child version, Maternal Sensitivity and Non-Intrusiveness Scales, Cry Paradigm).68)

Changes induced by IN-OT at fMRI

Pincus et al.65) used the RMET task and IN-OT administration to investigate mentalization in unmedicated depressed patients in a crossover RCT. RMET engaged the medial and lateral PFC, amygdala, insula and associative areas in both groups (IN-OT and placebo). However, after OT administration, depressed subjects showed increased activity in the superior middle frontal gyrus and insula, while controls exhibited more activity in ventral regions.

Vital sign, laboratory tests, and side effects

Only one crossover trial investigated salivary cortisol, heart rate and blood pressure, without finding any significant change after OT administration in MDD compared to placebo.64) None of included studies reported adverse events.

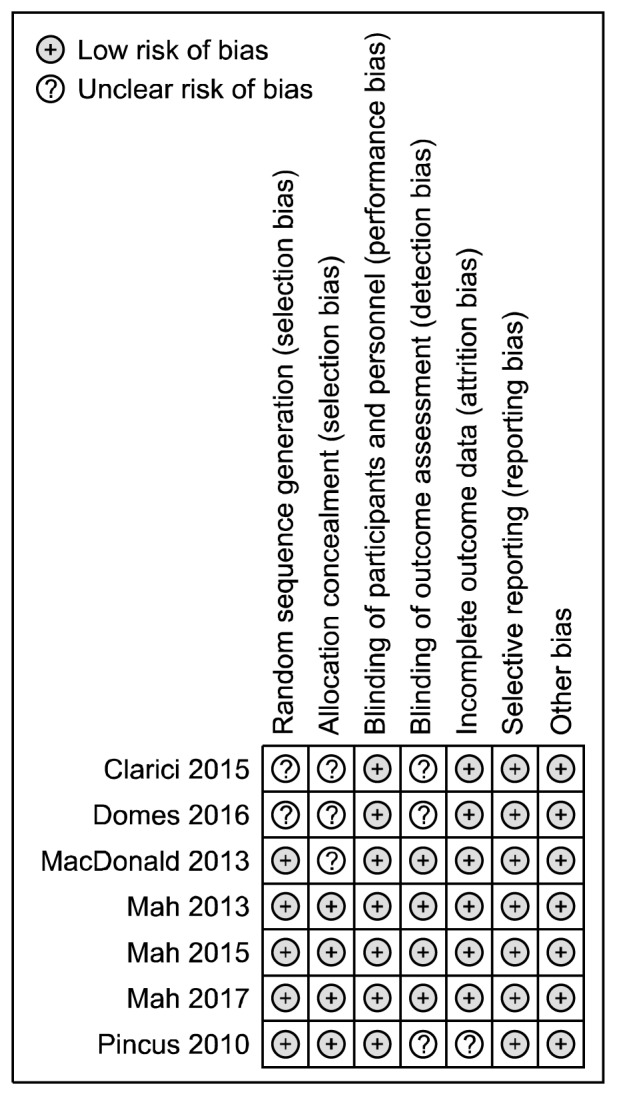

Risk of bias assessment of the included studies

A summary report of the risk of bias is presented in Figure 3. Five studies had adequate random sequence generation,63–65,67,68) while the other two did not provide sufficient information, and so they were rated as unclear.60,66) Four trials described the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail63,65,67,68); three studies had uncertain allocation concealment.60,64,66) All studies had blinding of participants and personnel. Blinding of outcome assessors was reported in four studies.63,64,67,68) Risk of attrition bias was low in six of the included studies.60,63,64,66–68) Selective reporting was low in all trials.

Fig. 3.

Risk of bias assessment of included studies in depressive disorders.

DISCUSSION

The present review systematically summarized all RCTs evaluating the effects of IN-OT in people affected by anxiety or depressive disorders.

Overall, our results confirm that the usefulness of OT in anxiety and depressive has been barely explored in literature. Specifically, the psychopathological complexity of two diagnostic categories such as anxiety and depression has not yet been carefully taken into consideration in the published literature. For instance, anxiety disorders are a complex and wide group of different psychiatric conditions,29) but, currently, IN-OT effect has been studied only in patients with social anxiety or a specific phobia (arachnophobia). The administration of IN-OT in both groups of patients provided inconsistent findings. However, it is important to underline that only a small part of the included studies evaluated core symptomatology (i.e., anxiety symptoms) by means of self-report questionnaire and only one study (Acheson et al.,38) 2015) used a clinician-rated measure of efficacy (CGI-improvement). Additionally, it is improbable that a single dose of IN-OT could modify core symptomatology rapidly (i.e., in a few hours), as the effect of OT on anxiety seemed mediated by the de-activation of the hypothalamus-hypophysis-adrenal axis and mean follow-up time of the included studies was too short. Thus, it is mandatory to extend the duration of OT administration in future trials in order to provide more reliable evidence for the use of IN-OT in anxiety.

The aforementioned considerations are valid also for the studies investigating the effect of IN-OT in depressive disorders: four papers focused on the effect of OT on post-partum depression while only three papers evaluating other depressive conditions. In the majority of cases, researchers have experimented only single administrations of IN-OT, thus evaluating its acute effect. Additionally, in contrast with anxiety studies, only one trial used a specific self-report assessment for depression (EPDS, HDRS) while all the others involved more generic measures of affect or social cognition. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that the inconsistent findings may be due to a lack of power of the included trials.

Several limitations should be taken into account while discussing the findings of the present systematic review. As demonstrated by the exiguous number of studies included in our review, research has not been sufficiently focused on the potential positive effects of IN-OT in psychiatric diseases. It has to be noted that some studies34–37,63,67,68) reported results from overlapping samples. As outcomes measures evaluated very different aspects of social cognition, attachment and psychopathology, it was hence not possible to homogeneously synthesize results from different studies, neither to meta-analyzed the data. It is important to stress that 13 out of 15 studies included in the present review investigated only single-dose administrations of IN-OT. Since the administration of IN-OT lacks of significant side effects,69) in contrast with those caused by common antidepressant medications,70) extending the duration of the trials could be safe and mandatory.

In conclusion, despite the large amount of data derived from preclinical studies and animal models, it is striking the lack of trials investigating the efficacy of IN-OT on core symptoms of anxiety and depression. The large majority of findings have focused on emotion recognition, showing positive results and confirming the prominent role of OT in modulating and promoting social behavior.71) Additionally, the absence of data on long-term use of IN-OT in these conditions needs to be filled. Future trials should include more specific measures of anxiety and depression, possibly clinician-rated (such as Hamilton Anxiety and Hamilton Depression) in order to explore the effect of IN-OT on these symptom clusters and to elucidate the role of IN-OT either as a stand-alone or as an adjunctive therapy for anxiety and depressive disorders.

REFERENCES

- 1.Feldman R, Weller A, Zagoory-Sharon O, Levine A. Evidence for a neuroendocrinological foundation of human affiliation: plasma oxytocin levels across pregnancy and the postpartum period predict mother-infant bonding. Psychol Sci. 2007;18:965–970. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine A, Zagoory-Sharon O, Feldman R, Weller A. Oxytocin during pregnancy and early postpartum: individual patterns and maternal-fetal attachment. Peptides. 2007;28:1162–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rocchetti M, Radua J, Paloyelis Y, Xenaki LA, Frascarelli M, Caverzasi E, et al. Neurofunctional maps of the ‘maternal brain’ and the effects of oxytocin: a multimodal voxel-based meta-analysis. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;68:733–751. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feeser M, Fan Y, Weigand A, Hahn A, Gärtner M, Böker H, et al. Oxytocin improves mentalizing-pronounced effects for individuals with attenuated ability to empathize. Psychoneuro-endocrinology. 2015;53:223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radke S, de Bruijn ERA. Does oxytocin affect mind-reading? A replication study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;60:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartz JA, Zaki J, Bolger N, Hollander E, Ludwig NN, Kolevzon A, et al. Oxytocin selectively improves empathic accuracy. Psychol Sci. 2010;21:1426–1428. doi: 10.1177/0956797610383439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brondino N, Fusar-Poli L, Politi P. Something to talk about: gossip increases oxytocin levels in a near real-life situation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;77:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guastella AJ, Einfeld SL, Gray KM, Rinehart NJ, Tonge BJ, Lambert TJ, et al. Intranasal oxytocin improves emotion recognition for youth with autism spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:692–694. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lischke A, Berger C, Prehn K, Heinrichs M, Herpertz SC, Domes G. Intranasal oxytocin enhances emotion recognition from dynamic facial expressions and leaves eye-gaze unaffected. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:475–481. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Domes G, Heinrichs M, Michel A, Berger C, Herpertz SC. Oxytocin improves “mind-reading” in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:731–733. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pedersen CA, Gibson CM, Rau SW, Salimi K, Smedley KL, Casey RL, et al. Intranasal oxytocin reduces psychotic symptoms and improves Theory of Mind and social perception in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2011;132:50–53. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams DR, Bürkner PC. Effects of intranasal oxytocin on symptoms of schizophrenia: A multivariate Bayesian meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;75:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutigliano G, Rocchetti M, Paloyelis Y, Gilleen J, Sardella A, Cappucciati M, et al. Peripheral oxytocin and vasopressin: Biomarkers of psychiatric disorders? A comprehensive systematic review and preliminary meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2016;241:207–220. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoop R. Neuromodulation by oxytocin and vasopressin. Neuron. 2012;76:142–159. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hashimoto H, Uezono Y, Ueta Y. Pathophysiological function of oxytocin secreted by neuropeptides: a mini review. Pathophysiology. 2012;19:283–298. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neumann ID, Landgraf R. Balance of brain oxytocin and vasopressin: implications for anxiety, depression, and social behaviors. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:649–659. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slattery DA, Neumann ID. No stress please! Mechanisms of stress hyporesponsiveness of the maternal brain. J Physiol. 2008;586:377–385. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.145896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waldherr M, Neumann ID. Centrally released oxytocin mediates mating-induced anxiolysis in male rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16681–16684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705860104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nyuyki KD, Waldherr M, Baeuml S, Neumann ID. Yes, I am ready now: differential effects of paced versus unpaced mating on anxiety and central oxytocin release in female rats. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23599. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neumann ID, Slattery DA. Oxytocin in general anxiety and social fear: a translational approach. Biol psychiatry. 2016;79:213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuzaki M, Matsushita H, Tomizawa K, Matsui H. Oxytocin: a therapeutic target for mental disorders. J Physiol Sci. 2012;62:441–444. doi: 10.1007/s12576-012-0232-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McQuaid RJ, McInnis OA, Abizaid A, Anisman H. Making room for oxytocin in understanding depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;45:305–322. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Simplicio M, Massey-Chase R, Cowen PJ, Harmer CJ. Oxytocin enhances processing of positive versus negative emotional information in healthy male volunteers. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23:241–248. doi: 10.1177/0269881108095705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baskerville TA, Douglas AJ. Dopamine and oxytocin interactions underlying behaviors: potential contributions to behavioral disorders. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010;16:e92–e123. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kroll-Desrosiers AR, Nephew BC, Babb JA, Guilarte-Walker Y, Moore Simas TA, Deligiannidis KM. Association of peri-partum synthetic oxytocin administration and depressive and anxiety disorders within the first postpartum year. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34:137–146. doi: 10.1002/da.22599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bell AF, Carter CS, Steer CD, Golding J, Davis JM, Steffen AD, et al. Interaction between oxytocin receptor DNA methylation and genotype is associated with risk of postpartum depression in women without depression in pregnancy. Fron Genet. 2015;6:243. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stuebe AM, Grewen K, Meltzer-Brody S. Association between maternal mood and oxytocin response to breastfeeding. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013;22:352–361. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009;3:e123–e130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: APA Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fang A, Hoge EA, Heinrichs M, Hofmann SG. Attachment style moderates the effects of oxytocin on social behaviors and cognitions during social rejection: applying an RDoC framework to social anxiety. Clin Psychol Sci. 2014;2:740–747. doi: 10.1177/2167702614527948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang A, Treadway MT, Hofmann SG. Working hard for oneself or others: Effects of oxytocin on reward motivation in social anxiety disorder. Biol Psychol. 2017;127:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guastella AJ, Howard AL, Dadds MR, Mitchell P, Carson DS. A randomized controlled trial of intranasal oxytocin as an adjunct to exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:917–923. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dodhia S, Hosanagar A, Fitzgerald DA, Labuschagne I, Wood AG, Nathan PJ, et al. Modulation of resting-state amygdala-frontal functional connectivity by oxytocin in generalized social anxiety disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:2061–2069. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gorka SM, Fitzgerald DA, Labuschagne I, Hosanagar A, Wood AG, Nathan PJ, et al. Oxytocin modulation of amygdala functional connectivity to fearful faces in generalized social anxiety disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:278–286. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Labuschagne I, Phan KL, Wood A, Angstadt M, Chua P, Heinrichs M, et al. Oxytocin attenuates amygdala reactivity to fear in generalized social anxiety disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:2403–2413. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Labuschagne I, Phan KL, Wood A, Angstadt M, Chua P, Heinrichs M, et al. Medial frontal hyperactivity to sad faces in generalized social anxiety disorder and modulation by oxytocin. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15:883–896. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711001489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Acheson DT, Feifel D, Kamenski M, McKinney R, Risbrough VB. Intranasal oxytocin administration prior to exposure therapy for arachnophobia impedes treatment response. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32:400–407. doi: 10.1002/da.22362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klorman R, Weerts TC, Hastings JE, Melamed BG, Lang PJ. Psychometric description of some specific-fear questionnaires. Behav Ther. 1974;5:401–409. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(74)80008-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szymanski J, O’Donohue W. Fear of Spiders Questionnaire. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1995;26:31–34. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(94)00072-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guy W US National Institute of Mental Health, Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. Rockvile, MD: US Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turner SM, Beidel DC, Dancu CV. SPAI Manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141–173. doi: 10.1159/000414022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mark RL. A brief version of the fear of negative evaluation scale. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 1983;9:371–375. doi: 10.1177/0146167283093007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rapee RM, Abbott MJ. Mental representation of observable attributes in people with social phobia. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2006;37:113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spielberg CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. STAI manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bond A, Lader M. The use of analogue scales in rating subjective feelings. Br J Med Psychol. 1974;47:211–218. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1974.tb02285.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF. Manual for the profile of mood states. San Diego: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams KD, Cheung CK, Choi W. Cyberostracism: effects of being ignored over the Internet. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79:748–762. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams KD, Jarvis B. Cyberball: a program for use in research on interpersonal ostracism and acceptance. Behav Res Methods. 2006;38:174–180. doi: 10.3758/BF03192765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Posner MI. Orienting of attention. Q J Exp Psychol. 1980;32:3–25. doi: 10.1080/00335558008248231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Posner MI, Snyder CR, Davidson BJ. Attention and the detection of signals. J Exp Psychol. 1980;109:160–174. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.109.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Treadway MT, Buckholtz JW, Schwartzman AN, Lambert WE, Zald DH. Worth the ‘EEfRT’? The effort expenditure for rewards task as an objective measure of motivation and anhedonia. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rapee RM, Lim L. Discrepancy between self- and observer ratings of performance in social phobics. J Abnorm Psychol. 1992;101:728–731. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.101.4.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mochcovitch MD, da Rocha Freire RC, Garcia RF, Nardi AE. A systematic review of fMRI studies in generalized anxiety disorder: Evaluating its neural and cognitive basis. J Affect Disord. 2014;167:336–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stein MB, Simmons AN, Feinstein JS, Paulus MP. Increased amygdala and insula activation during emotion processing in anxiety-prone subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:318–327. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shin LM, Liberzon I. The neurocircuitry of fear, stress, and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:169–191. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sripada CS, Phan KL, Labuschagne I, Welsh R, Nathan PJ, Wood AG. Oxytocin enhances resting-state connectivity between amygdala and medial frontal cortex. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:255–260. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712000533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clarici A, Pellizzoni S, Guaschino S, Alberico S, Bembich S, Giuliani R, et al. Intranasal adminsitration of oxytocin in postnatal depression: implications for psychodynamic psychotherapy from a randomized double-blind pilot study. Front Psychol. 2015;6:426. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6:278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mah BL, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Smith R, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. Oxytocin in postnatally depressed mothers: its influence on mood and expressed emotion. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;40:267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.MacDonald K, MacDonald TM, Brüne M, Lamb K, Wilson MP, Golshan S, et al. Oxytocin and psychotherapy: a pilot study of its physiological, behavioral and subjective effects in males with depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:2831–2843. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pincus D, Kose S, Arana A, Johnson K, Morgan PS, Borckardt J, et al. Inverse effects of oxytocin on attributing mental activity to others in depressed and healthy subjects: a double-blind placebo controlled FMRI study. Front Psychiatry. 2010;1:134. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2010.00134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Domes G, Normann C, Heinrichs M. The effect of oxytocin on attention to angry and happy faces in chronic depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:92. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0794-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mah BL, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IMH, Smith R. Oxytocin promotes protective behavior in depressed mothers: a pilot study with the enthusiastic stranger paradigm. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32:76–81. doi: 10.1002/da.22245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mah BL, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Out D, Smith R, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. The effects of intranasal oxytocin administration on sensitive caregiving in mothers with postnatal depression. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2017;48:308–315. doi: 10.1007/s10578-016-0642-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.MacDonald E, Dadds MR, Brennan JL, Williams K, Levy F, Cauchi AJ. A review of safety, side-effects and subjective reactions to intranasal oxytocin in human research. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:1114–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Serretti A. The present and future of precision medicine in psychiatry: focus on clinical psychopharmacology of antidepressants. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2018;16:1–6. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2018.16.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Churchland PS, Winkielman P. Modulating social behavior with oxytocin: how does it work? What does it mean? Horm Behav. 2012;61:392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]