Abstract

Oxalate nephropathy is associated with hereditary hyperoxaluria, Crohn disease, and previous gastric or intestinal surgery, especially in the setting of increased oxalate intake or ethylene glycol ingestion. We present a patient whose intake of vitamin C supplements (2 g/day), exacerbated by predisposing factors of prior small bowel obstruction and resection, and benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH), resulted in acute kidney injury due to oxalate nephropathy. We review past reports of vitamin C-induced oxalate nephropathy and discuss the underlying precipitating factors.

Keywords: Acute renal failure, Dialysis, Vitamin C

Introduction

Oxalate nephropathy occurs when oxalate crystals deposit in the tubules and interstitium of the kidney, resulting in acute tubular necrosis and renal failure. It can be primary, as in hereditary hyperoxaluria, or acquired. The most common presentation of acquired oxalate nephropathy is ingestion of ethylene glycol, which causes increased endogenous production of oxalate [1].

Vitamin C, also known as l-ascorbic acid, is a water-soluble vitamin and essential nutrient. Ascorbic acid intake greater than 2 g/day can induce oxalate crystal nephropathy, although cases have been documented with intake as low as 480 mg/day PO and a single dose of 45 mg IV [2–6]. Enteric fat malabsorption, as seen in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery, [7] orlistat therapy, [8] and malabsorptive disorders can also cause hyperoxaluria, leading to oxalate nephropathy. We present a case of ascorbic acid-induced oxalate nephropathy in a patient with a history of small bowel resection and BPH who was taking ascorbic acid supplementation (2 g/day), leading to acute kidney injury with tubular atrophy.

Case presentation

A 69-year-old male with history of BPH and small bowel resection for strangulated Meckel diverticulum, presented with gradual onset of decreased urinary output, fatigue, anorexia, and confusion that had gradually progressed over the preceding 3 weeks.

On presentation, he was hemodynamically stable, lethargic but arousable, and had word-finding difficulty. Cardiopulmonary, abdominal, and neurologic exams were benign. Initial laboratory studies yielded a blood urea nitrogen (BUN) of 135 mg/dL and creatinine of 9.51 mg/dL (baseline 7 mg/dL and 0.95 mg/dL, respectively). After placement of a Foley catheter, 500 mL of urine was collected. Urinalysis showed 24 WBCs/hpf, 1264 RBCs/hpf, and muddy brown casts. Serum c-ANCA, p-ANCA, ANA, and complement C3 and C4 levels were within normal values. There was no serologic evidence of hepatitis B or C infection. Diagnostic imaging was obtained, which revealed normal size of kidneys without hydronephrosis and a 1.9 cm hypodense lesion arising from superior pole of left kidney suggestive of simple cyst.

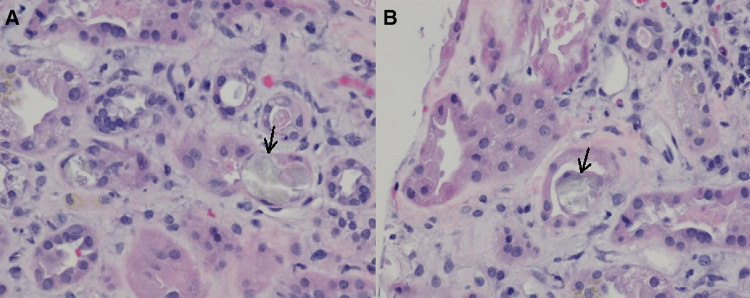

Due to persistently elevated creatinine and BUN, hemodialysis was initiated on the fifth day of admission, for a total of four sessions. As the etiology of the acute kidney injury remained unclear, a renal biopsy was performed, revealing interstitial edema, fibrosis and inflammation with lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and the presence of positively birefringent crystals consistent with calcium oxalate within the lumen and cytoplasm of 5% of the renal tubules. Renal tubules were dilated with vacuolated cytoplasm in the proximal tubular epithelium and loss of the brush border (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Left Renal Biopsy (H&E staining, × 400). There is focal loss of tubular epithelium and interstitial edema with lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates around the tubules (a) with calcium oxalate crystals (a, b; arrows), as well as interstitial fibrosis and inflammation and mild arterionephrosclerosis (a, b)

Further history revealed that the patient was taking 2 g/day of vitamin C over the past 2 years. It is likely that oxalate nephropathy developed due to excessive supplement use, exacerbated by BPH and past small bowel resection. Urinary obstruction was relieved with Foley catheter, vitamin C was discontinued, and he was started on low oxalate diet with significant improvement of renal function. By the day of discharge, renal function had recovered, and creatinine levels had trended downwards to 2.74 mg/dL, and to 1.75 mg/dL 4 months after discharge.

Discussion

Ascorbic acid is a water-soluble antioxidant that is important in hydroxylation and amidation reactions. The mechanisms involving the breakdown of ascorbic acid in tissues are still unclear, but it is known to be oxidized to dehydroascorbic acid, then to diketogulonic acid, and ultimately catabolized to oxalate, which is excreted in urine in amounts proportional to intake of ascorbic acid [9–11]. Supersaturated calcium oxalate in the tubules preferentially deposit as crystals in damaged tubular epithelium, where they are thought to cause both obstruction and apoptosis of tubular epithelial cells [12].

Oxalate nephropathy results when deposition of oxalate crystals causes tubular injury, interstitial fibrosis and inflammation. Previous case reports of acute ascorbic acid-induced oxalate nephropathy describe similar biopsy findings and noted delayed recovery of acute kidney injury [2–6]. In several reported cases, vitamin C intake was linked temporally to acute renal failure ranging from weeks to months prior to presentation (Table 1) [2–6, 13–18]. Our patient had been taking vitamin C supplements for the past 2 years. He also had post-renal obstruction due to BPH, which likely led to increased crystal deposition in the renal tubules from chronic urinary retention [12]. Additionally, history of small bowel resection increased oxalate absorption via enteric fatty acid malabsorption. It is believed that decreased fat absorption causes calcium to bind the free fatty acids that are not absorbed, reducing calcium oxalate precipitation in the feces and increasing absorption of soluble oxalate, which is excreted in the urine [8]. In normal subjects, oxalate absorption in the intestines is less than 20%, but it increases to 35–50% in subjects with small bowel resection [19].

Table 1.

Oxalate-induced case reports

| Refs. # | Age | Sex | Ascorbic acid dose | Precipitating comorbidities | Highest Cr level | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 69 | M | 2 g daily for years | BPH, Crohn’s-like inflammation, small bowel resection | 9.51 mg/dL | Recovery (Cr 1.75 mg/dL) |

| [2] | 58 | F | 3–6.5 g daily for 1 month | Celiac disease | 9.1 mg/dL | HD-dependent, awaiting transplant |

| [3] | 72 | M | 480–960 mg daily for 3–4 months | Increased oxalate-rich “leafy vegetables” intake | 10.6 mg/dL | Recovery (Cr 1.9 mg/dL) |

| [4] | 59 | F | 4 g daily for 30 days | Uterine leiomyosarcoma treated with hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | 1.88 mg/ddL | ESRD, palliative care |

| [5] | 51 | F | 2 IV doses (unspecified) | SLE, anemia of chronic disease, pleural/pericardial effusions | 7.2 mg/dL | Recovery (Cr 1.1 mg/dL) |

| [6] | 61 | M | 60 g IV over 2 days | Metastatic prostate carcinoma causing bilateral ureteral obstruction and renal insufficiency | 13.4 mg/dL | Renal impairment (Cr 2.94 mg/dL) |

| [13] | 58 | F | 45 g IV once | Amyloidosis causing nephrotic syndrome | 3.5 mg/dL | Death |

| [14] | 72 | M | Unspecified | Putative pernicious anemia, hemicolectomy | 15.3 mg/dL | Death |

| [15] | 71 | F | 500 mg daily for 6 months | Piridoxilate ingestion | 12.1 mg/dL | ESRD |

| [16] | 73 | M | 680 mg daily for 4 months | Oxalate-rich diet, chronic diarrhea, chronic alcoholism, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, heart failure, and hypothyroidism | 8.4 mg/dL | Recovery (Cr 1.8 mg/dL) |

| [17] | 49 | F | 4 g daily for several months | Migraine headaches treated with a large amount of ibuprofen (2000 mg/d) | 4.5 mg/dL | Recovery (Cr 1.1 mg/dL) |

| [18] | 58 | M | 1.6 g daily for 50 days | Third-degree burn injury | 1.4 mg/dL (at the time of ATN) | Recovery (Cr 1.4 mg/dL) |

Brief description of previous and current cases of acute ascorbic acid-induced oxalate nephropathy

ATN acute tubular necrosis, BPH benign prostatic hyperplasia, Cr creatinine, ESRD end-stage renal disease, HD hemodialysis, IV intravenous, SLE systemic lupus erythematous

aCase described in this report

The duration and dose of vitamin C intake that have been associated with oxalate nephropathy vary widely between published reports, and it is likely that underlying disease processes influence the development of acute kidney injury. Ascorbic acid-induced oxalate nephropathy can lead to severe outcomes including chronic renal disease requiring long-term dialysis, transplantation, or death [2, 12]. In the case of our patient, we speculate that the combination of BPH causing urinary obstruction and oxalate nephropathy led the acute kidney injury. Our patient’s renal function improved and remained stable after resolution of urinary obstruction and discontinuation of vitamin C supplementation. Given the potential severity of this disease, it is important for the clinician to consider excessive ascorbic acid intake in setting of co-morbidities such as BPH and small bowel resection when evaluating a patient for acute renal failure in the absence of a clear etiology.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Bhuvaneswari Krishnan MD for pathology interpretation and Divya Janardhanan MD and Saed Shawar MD for their assistance in the medical care of this patient.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflicts of interest exists.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

The subject’s identity has been masked. No identifying details are included in this manuscript to ensure complete anonymity.

References

- 1.Stokes MB. Acute oxalate nephropathy due to ethylene glycol ingestion. Kidney Int. 2006;69:203. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurm H, Sheta MA, Nivera N, et al. Vitamin C-induced oxalate nephropathy: a case report. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2012 doi: 10.3402/jchimp.v2i2.17718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamarche J, Nair R, Peguero A, et al. Vitamin C-induced oxalate nephropathy. Int J Nephrol. 2011;2011:146927. doi: 10.4061/2011/146927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poulin LD, Riopel J, Castonguay V, et al. Acute oxalate nephropathy induced by oral high-dose vitamin C alternative treatment. Clin Kidney J. 2014;7:218. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfu013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cossey LN, Rahim F, Larsen CP. Oxalate nephropathy and intravenous vitamin C. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61:1032–1035. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong K, Thomson C, Bailey RR, et al. Acute oxalate nephropathy after a massive intravenous dose of vitamin C. Aust N Z J Med. 1994;24:410–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1994.tb01477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duffey BG, Alanee S, Pedro RN, et al. Hyperoxaluria is a long-term consequence of Roux-en-Y Gastric bypass: a 2-year prospective longitudinal study. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaudhari D, Crisostomo C, Ganote C, et al. Acute oxalate nephropathy associated with orlistat: a case report with a review of the literature. Case Rep Nephrol. 2013;2013:124604. doi: 10.1155/2013/124604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hellman L, Burns JJ. Metabolism of l-ascorbic acid-1-C14 in man. J Biol Chem. 1958;230:923–930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levine M, Conry-Cantilena C, Wang Y, et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: evidence for a recommended dietary allowance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3704–3709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knight J, Madduma-Liyanage K, Mobley JA, et al. Ascorbic acid intake and oxalate synthesis. Urolithiasis. 2016;44:289–297. doi: 10.1007/s00240-016-0868-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verkoelen CF, Verhulst A. Proposed mechanisms in renal tubular crystal retention. Kidney Int. 2007;72:13–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawton JM, Conway LT, Crosson JT, et al. Acute oxalate nephropathy after massive ascorbic acid administration. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:950–951. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1985.00360050220044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McHugh GJ, Graber ML, Freebairn RC. Fatal vitamin C-associated acute renal failure. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2008;36:585–588. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0803600413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mousson C, Justrabo E, Rifle G, et al. Piridoxilate-induced oxalate nephropathy can lead to end-stage renal failure. Nephron. 1993;63:104–106. doi: 10.1159/000187151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rathi S, Kern W, Lau K. Vitamin C-induced hyperoxaluria causing reversible tubulointerstitial nephritis and chronic renal failure: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2007;1:155. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-1-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nasr SH, Kashtanova Y, Levchuk V, et al. Secondary oxalosis due to excess vitamin C intake. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1672. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alkhunaizi AM, Chan L. Secondary oxalosis: a cause of delayed recovery of renal function in the setting of acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7:2320–2326. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V7112320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Worcester EM. Stones from bowel disease. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2002;31(4):979–999. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8529(02)00035-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]