Abstract

Various explanations have been proposed to explain the low levels of physical activity among Latinas. Included is the construct marianismo, which describes the influence of cultural beliefs on gender role identity, including prioritisation of familial responsibilities over self-care. The purpose of the study was to explore the influence of marianismo beliefs on participation in habitual and incidental physical activity among middle-aged immigrant Hispanic women, using a community- based participatory research approach and Photovoice methodology. Eight immigrant Hispanic women were given digital cameras and asked to photograph typical daily routines, including household activities, family/childcare and occupational responsibilities. Subjects then met to discuss their impressions. Data were analysed using Spradley’s Developmental Research Sequence. Results revealed that a combination of marianismo beliefs and socioeconomic pressures appeared to negatively influence women’s ability to participate in physical activity.

Keywords: Photovoice, physical activity, ethnography, culture circles, Latinas

Physical activity is widely recognised as an important health promotion behaviour for women. However, it is well documented that women of all ages report less physical activity than men and that married women with children are less likely to report participation in regular exercise (Verhoef and Love 1994). This lack of physical activity appears to be more profound among Hispanic women (Latinas), even when compared to other minority groups (Evenson et al. 2002, National Center for Health Statistics 2007) and exists regardless of socioeconomic status (Crespo et al. 2000). Furthermore, the levels of both habitual (planned) and incidental (accrued over the course of daily activities) physical activity among Hispanic immigrant women decrease dramatically following their arrival in the USA (Juniu 2000, Himmelgreen et al. 2003).

Sedentary habits among Hispanic women place them at significantly higher risk for the development of over 20 chronic illnesses, including hypertension, Type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease (Booth et al. 2002). This is of particular importance for mid-life women, since the rate of coronary artery disease is two to three times higher among postmenopausal women than among those who are premenopausal (American Heart Association 2008). Since rates of cardiovascular disease among Latinos have been found to increase with the length of time spent living in the USA (Koya and Egede 2007), it is imperative that the need for cardio-protective measures (e.g., regular physical activity) be emphasised among mid-life immigrant Hispanic women.

Various hypotheses have been advanced to explain the lack of physical activity among Hispanic women. Latinas are often socialised into placing family needs above their own throughout their lives. This construct, referred to as marianismo (Stevens 1973, Comas-Diaz 1988, Gil and Vasquez 1996), may contribute to the feelings of depression and low self-efficacy for physical activity among immigrant Latinas (Alvarez 1993). Few studies have examined the belief systems of Hispanic women with regard to exercise and physical activity. Furthermore, no reported studies have explored the relationship of cultural norms, gender-based role beliefs and socioeconomic pressures on immigrant Hispanic women to influence participation in incidental and habitual physical activity. Thus, little is known about how to encourage such health-promoting life-style behaviours among mid-life immigrant Latinas.

The purpose of the study was to explore the influence of marianismo beliefs on participation in habitual and incidental physical activity among middle-aged immigrant Hispanic women and to identify the participants’ common views of the place that physical activity has in a woman’s life. The study was an example of community-based participatory research (CBPR) using Photovoice methodology. Photovoice is a qualitative research method that utilises photography, reflection, writing and discussion to understand an essential phenomenon (Wang 2005). The specific aims of this Photovoice study were to: (1) explore, within the Latina community, the interplay of gender role identity and culture and how this affects participation in physical activity; (2) discover and legitimise the participant’s ‘popular knowledge’ as a source of expertise; (3) promote participants’ critical dialogue and knowledge about physical activity through group discussion of photographs; and (4) mobilise formal and informal community leaders to help implement changes recommended by the women.

Background

Physical activity among Latinas

Gender, ethnicity, culture and race are all determinants of physical activity (Sallis and Owen 1998). Physical activity can be broken down into two types: ‘incidental’ (life-style) and ‘habitual’ (planned) (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 1996). Compared to men, women typically spend a larger percentage of their time engaged in incidental forms of activity (e.g., household, family care and occupational pursuits) than in habitual, leisure-time or fitness activities (Ainsworth 2000). Participation in vigorous physical activity among females in the USA peaks around the ninth-grade and declines thereafter. This decline is steeper in Hispanic women as compared to Black and non-Hispanic White women (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2003). Such racial and ethnic differences in levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity are apparent between Hispanic and White non-Hispanic females as early as eight years of age (Grunbaum et al. 2004). These disparities suggest that culture-specific beliefs and ‘popular’ attitudes about exercise may influence participation in physical activity among Hispanic females. In an ethnographic study of Black and Latina college students, D’Alonzo and Fischetti (2008) reported that Hispanic women were: (1) less likely than Black women to have role models for healthy physical activity, (2) more likely to feel that familial responsibilities were a major barrier to participation in physical activity, and (3) more likely to believe that some types of vigorous physical activity were not suited for women. These beliefs were strongest among first generation Hispanic-American women. Since Latinas are often less likely to participate in habitual physical activity, it has been suggested that assessments of incidental physical activity acquired through informal, home-centred activities may provide important information, not found elsewhere, regarding Latina behavioural patterns (Floyd 1998).

Marianismo

The term marianismo was first coined by Stevens (1973) and has been identified as the female counterpart of machismo. The ideal Latina (marianista) places family needs above her own and adheres to traditional Hispanic values, including male supremacy, female self-sacrifice (sacrificio) (Cofresi 2002) and deferment of pleasure, in imitation of the Blessed Virgin (Comas-Diaz 1988, Gil and Vasquez 1996). In Hispanic culture, the family is conceptualised as the nuclear and extended families, as well as friends, neighbours and communities (Falicov 1996). Marianismo beliefs have been shown to negatively impact health promotion behaviours among Hispanic women (Cianelli et al. 2008). Latinas with strong marianismo beliefs are likely to perceive physical activity as a selfish indulgence rather than a health-promoting life-style behaviour for women. Attempts to maintain marianismo and other traditional values while acculturating into mainstream American society often result in cultural conflict, which in turn can lead to depression and low self-efficacy for exercise. Rather than mandate that these women follow American cultural norms and adopt a more autonomous, individualistic perspective to self-care, healthcare providers need to assist Latinas to problem-solve culturally appropriate ways to achieve a satisfying balance between responsibilities towards others (marianismo) and participation in healthy self-care activities such as physical activity.

This study focused on middle-aged women for two reasons. First, peri-menopausal and menopausal women are at greater risk for the development of coronary heart disease than their younger counterparts (American Heart Association 2008) and being sedentary is an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic heart disease in women (Eaton et al. 1995). Second, since their children are likely to be older, mid-life women may be less affected by the impact of marianismo with regard to direct childcare responsibilities and thus may have more time available to engage in leisure-time physical activity.

Constraints on leisure-time activity

Leisure research, particularly leisure constraints research, offers one promising framework for examining the barriers to participation in physical activity by immigrant women. Leisure constraints are said to ‘limit the formation of leisure preferences and inhibit or prohibit participation and enjoyment in leisure’ (Jackson 1991, p. 279). In their Hierarchical Model of Leisure Constraints, Crawford et al. (1991) identified three major types of constraints to leisure activity, including intrapersonal, interpersonal and structural. Intrapersonal constraints are defined as psychological factors internal to the individual, interpersonal constraints arise from interaction with others, while structural constraints include factors relating to the external environment. Empirical data from studies using the constraints framework suggest that women do face more constraints on their leisure time than men (Jackson and Henderson 1995), largely because of paid and unpaid work, care- giving responsibilities and household duties. These activities may collectively contribute to a prioritisation of family needs and may cause women to suffer from a lack of a sense of entitlement to leisure activity (Bedini and Guinan 1996). Like-wise, Green and Hebron (1988) have reported that some women are less likely to participate in leisure activities which are deemed socially inappropriate, particularly by their husbands.

An emerging area of study is a consideration of the ways in which constraints to leisure may be similar or different across cultures. Several researchers (Stodolska 1998, Chick and Dong 2003, Walker et al. 2007) have observed that culture appears to be a type of constraint that is not easily subsumed by interpersonal, intrapersonal or structural categories and that these constraints may in fact be subordinate to culture. Immigrant groups in particular have numerous constraints to participation in leisure activity that are not generally found among majority populations, including inadequate language skills, social isolation/separation from family and friends and lack of familiarity with the environment (Stodolska 1998, Stodolska and Yi-Kook 2005). Many immigrants report little leisure time, as they are focused on attaining economic stability, creating a secure future for their children and sending remittances home to relatives. It is apparent that differences in leisure styles result from variations in norms and values among ethnic and racial groups, including those cultural beliefs relating to the role of immigrant women, such as marianismo. There-fore, a comprehensive understanding of the influence of cultural beliefs on Hispanic immigrant women’s participation in physical activity requires an examination of the context of cultural identity as it relates to leisure activity (Arab-Moghaddam et al. 2007). At present, there are no published studies which examine the interplay of cultural norms, gender-based role beliefs and socioeconomic pressures on immigrant Hispanic women to influence participation in incidental and habitual physical activity.

Research design and methods

Community-based participatory research (CBPR)

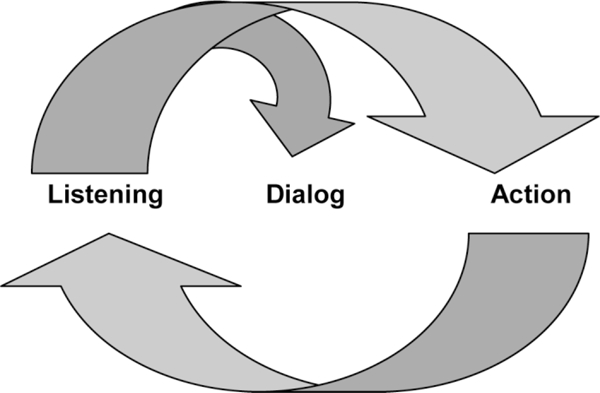

CBPR models call for a collaborative approach between the researcher and the community with the aim of combining knowledge and action for social change to improve community health and eliminate health disparities (Minkler and Wallerstein 2003). One such approach is Paulo Freire’s empowerment model, based upon his work in adult literacy in Brazil (Wallerstein and Bernstein 1988). Freire posited that the purpose of education is human liberation, where individuals become the subjects of their own learning. Freire referred to this as the ‘learner as subject’ approach (Freire 1973). The learning process (depicted in Figure 1) is characterised by structured dialogue, wherein everyone involved participates as a co-learner. Freire’s approach, sometimes referred to as ‘popular’ or ‘empowerment’ education, has become the basis for community-based health promotion programmes for oppressed populations throughout Latin America, Asia and Africa and, to a lesser extent, the USA. Freirian methods seek to optimise empowerment of individuals and communities to move beyond feelings of powerlessness, assume control of their lives and promulgate the formation of a partnership between the investigator and participants (Freire 1970). Freire’s empowerment framework appears to hold much promise to assist low-income individuals and communities to become empowered to adopt health promotion behaviours.

Figure 1.

Frierian structured dialog model. Adapted from Wallerstein and Sanchez-Merki (1994).

Photovoice

As a philosophical approach to research, CBPR does not dictate a specific data collection or analysis method. However, the use of a qualitative methodology, i.e., Photovoice (Wang and Redwood-Jones 2001, Wang 2005), can facilitate a better understanding of the cognitive elements surrounding the adoption of health promotion behaviours such as physical activity. This is particularly true with regard to complex cultural values such as marianismo. Photovoice emphasises the importance of participants speaking about their experiences and analysing the connections between situations and solutions using photography (Wang and Redwood-Jones 2001) Wang, who developed this method, outlined the process as follows: (1) conceptualise the problem, (2) define goals and objectives, (3) conduct Photovoice training, (4) take photographs, (5) facilitate group discussion, (6) encourage critical reflection and dialogue, and (7) document the stories.

Since Photovoice integrates Paulo Friere’s approach to critical education and CBPR, it is ideally suited to this type of investigation. The use of Photovoice in healthcare research can be viewed as an attempt to empower participants to help disrupt and ultimately reject unhealthy behaviours that are influenced by gender, class, ethnic and other types of oppression. In this respect, Photovoice can be seen as a type of empowerment intervention. Photovoice has been used successfully in several studies among Hispanic immigrant populations (Gallo 2002, Keller et al. 2007).

Setting

Photovoice participants met in the Salvation Army centre of a suburban community in central New Jersey, USA, where almost 40% of the town’s inhabitants are first and second generation Hispanic-American. The Salvation Army provides numerous community services for the immigrant population from Central America, in this area and serves as a neighbourhood meeting centre for Latinos. Refreshments were served during the two sessions.

Sample

The purposive sample consisted of eight females, ages 35–55 years old, who self-identified as first-generation Hispanic or Latina. The subjects, who were members of a women’s ministry group, were invited to meet at the Salvation Army centre for a charla (informal social gathering) and Photovoice group orientation by a key informant at the Salvation Army. The subjects were purposefully selected (Creswell 2009) by the key informants because they were considered ‘typical’ of the immigrant women in the congregation and had voiced an interest in improving their health. Wang and Pies (2004) have noted that 8–12 subjects are the ideal size for a Photovoice project. Six of the eight subjects were from Costa Rica, one was from Puerto Rico and the other was born in El Salvador. Seven of the eight women spoke only Spanish, while one was bi-lingual. Length of residence in the USA for the women in the group ranged from 2 months to 35 years. Immigration status was not assessed. All of the women were employed outside the home as cleaners, housekeepers, factory or childcare workers, and most worked a number of part-time jobs for an hourly wage. Seven of the eight women were married and all had children or grandchildren living with them in the USA.

Data collection

The study was conducted based on the process identified by Wang and Pies (2004). A preliminary two-hour session was held in Spanish to introduce the research question (‘How do cultural beliefs influence participation in physical activity among Hispanic immigrant women?’) and to familiarise the women with the goals and methods of Photovoice. The investigator and research team described the method and use of the camera and its application to physical activity, using principles of popular education advocated by Freire (1973). Ethical issues associated with the use of Photovoice, including what and who to photograph and measures to minimise invasion of privacy, were also discussed. Following the presentation, the women were given the opportunity to ask questions and discuss the use of the camera. The subjects were required to complete three consent forms for the study. In addition to the conventional informed consent, subjects completed a consent form to have their photograph taken, and another to permit their photographs to be used only for research purposes. Subjects were given multiple copies of the last two forms, in the event they wished to photograph other women engaged in physical activity.

Following informed consent, the women were given a digital camera and asked to photograph: (1) a typical day’s activities, including household tasks, family/childcare and occupational responsibilities; (2) examples of both habitual and incidental physical activity accrued throughout the day, including walking to work, to a neighbour’s home or grocery store; and (3) examples of other Latinas participating in such activities. Participants had one week to take the pictures and then return the memory card to the investigator. Two sets of photographs were developed, enlarged and printed, one set for the investigator and one for the participants. Utilising what Freire referred to as ‘culture circles’ (Freire 1970), the women met for a second time and were asked to select one or two photos they felt were most significant in terms of describing a typical day and in illustrating physical activity.

A copy of the question guide for the study is included in Table 1. A few broad, open-ended questions were scripted to encourage participation from the women and focus on the emic perspective. Additional questions flowed from the responses of the informants, as noted in Table 2. Discussions were audio-taped and later transcribed by a bi-lingual transcriptionist. Two tape recorders were used in the event of equipment malfunction. The culture circle discussion session lasted approximately 2–2.5 hours. Each woman was given the camera to keep as compensation for her participation in the study.

Table 1.

Interview guide.

| 1. Which photographs have you selected? 2. What is it about these photographs that are important to you? 3. What do these photographs tell us about: yourself, your family, your everyday life? 4. What do these photographs tell us about the meaning of physical activity in your life? |

Table 2.

Spradley’s Developmental Research Sequence (DRS).

| Steps | Implementation |

|---|---|

| 1. Locating an informant | • Purposive sampling • Key informants • Good rapport with informants |

| 2. Interviewing an informant | • Naturalistic setting • ‘Culture circle’ format • Interviews tape-recorded, transcribed, translated and back- translated |

| 3. Making an ethnographic record | • Field notes, tape recordings, transcripts and photographs |

| 4. Asking descriptive questions | • Grand tour questions - Which photographs have you selected? What is it about these photographs that are important to you? • Mini-tour question - What do these photographs tell us about: yourself, your family, your everyday life? • Example question - What kinds of exercise did you used to do? • Experience question - How many houses do you typically clean in a day? • Native language question - What does the term marianismo mean to you? |

| 5. Analysing ethnographic interviews | • Cultural meaning created by the use of symbols, categories |

| 6. Making a domain analysis | • Overall term given to a symbolic category. Includes cover term, included terms and semantic relationships |

| 7. Asking structural questions | • Help to clarify terms already used or develop new categories - What kinds of work do you do in a normal day? |

| 8. Making a taxonomic analysis | • In depth study of the domain; includes cover term and included terms - ‘I am working all these jobs to put my children through college |

| 9. Asking contrast questions | • Distinguish between included terms and their subsets - How did you take care of yourself differently in your own country? |

| 10. Making a componential analysis | • Reduce each term to a plus or minus value |

| 11. Discovering cultural themes | • Focus on values inferred from data |

Data analysis

Spradley’s Developmental Research Sequence (DRS) was used to guide data collection and analysis of the Photovoice transcripts (Spradley 1979). The DRS is based upon ethnosemantic analysis; the researcher learns about the reality of an individual’s experience through a study of the meaning behind the spoken word (Frake 1962), informants share details of their experiences, while the researcher identifies common beliefs and values that emerge from the data. Spradley (1979) asserted that cultural knowledge can be elicited through a systematic process, which can be organised in a structured manner. Spradley’s DRS was selected for this study because of its systematic and rigorous approach to data collection and analysis, and strong emphasis on the emic perspective. Like Photovoice, this aspect was felt to be especially important when working with a population (immigrant Latinas) that is seldom heard from. The tandem use of two qualitative methods (Photovoice and the DRS) created an integrated package, upon which to build a framework to better understand the life experiences of immigrant Latinas. Triangulation of the findings was ensured by the use of multiple data collection strategies, including interview transcripts, participant photographs, field notes and participant demographic information. Because of the DRS’s emphasis on semantics and the fact that the discussions were conducted in Spanish, the Principal Investigator (PI) and transcriptionist paid particular attention to the translation/back translation process when transcribing and analysing the data.

The steps in Spradley’s DRS as well as how they were utilised in the study are summarised in Table 2. In this study, words that related to daily activities, including household tasks, family/childcare, occupational responsibilities, and forms of habitual and incidental physical activity suggested by the informants formed the basic semantic relationship used for domain analysis. A taxonomic analysis refined the meaning of each term included within a domain by determining a set of categories that described the attitudes associated with each category. Cultural themes that reflected the participants’ views of the place physical activity has in a woman’s life were then determined (Spradley 1979)

The moderator, co-moderator and recorders met immediately after the culture circle discussion session to debrief and then engage in member checking with study participants. The audio-taped recordings were later transcribed into English and back- translated into Spanish by a paid transcriptionist and the results were reviewed by the research team and informants. Transcripts were checked for accuracy against original tapes and field notes to verify consistency. To ensure adequate reliability and identify errors and incomplete data, the authors replayed the audiotapes while reviewing a copy of the transcript. Responses were first hand-coded and then domain, taxonomic, compo- nential and cultural theme analyses were performed. Included terms and themes were developed following member checks with study participants (Creswell 2009). The research team then recoded the transcripts using computer software (Ethnograph, Version 5.7, Qualis Research). Inter-coder reliability (Weber 1990) was satisfactory and minor coding, category and theme discrepancies between the two versions were discussed and resolved among the members of the research team and study participants. Triangulation of data sources and member checking were used to assure the validity of the findings. In addition, a peer debriefer (Creswell 2009) who was not involved in the study assisted in reviewing the study transcripts and data analysis methods.

Human subjects

Approval from the University Institutional Review Board was obtained before the study was initiated. The study was described and explained to the participants, both in English and in Spanish. Each participant received a copy of the consent form (in English or Spanish, as preferred), which included information regarding confidentiality and the right to refuse to participate or to terminate participation at any time.

Results

All of the eight women who participated in the Photovoice project indicated that their primary motive for residence in the USA was ‘to make money for my family’. For all but one of these women, this phrase meant working to save money to help with their children’s college education. Six of the women related they had previously not worked outside the home in their native countries. The women indicated that their work was overwhelmingly seen as the biggest obstacle to leisure-time physical activity. Indeed, most of the photographs were taken of the women at work. The domain term, which represents the main idea addressed within the study, was ‘Trabajando todo el tiempo’ - ‘Working all the time’. This term was best represented by a Costa Rican woman in her photo and caption (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

‘I have been in this country for six months and I haven’t rested a single day. There is too much stress. God willing, I am leaving on Saturday.’

Although all of the women were familiar with the term ‘marianismo’, they initially saw marianismo beliefs and work as two separate issues. With discussion, one of the informants pointed out that their need to work could be driven by an overriding desire to improve the life of their children. At this point, the other subjects acknowledged the likelihood of a connection between this behaviour and marianismo.

Four included terms and three cultural themes were identified from the transcripts. In this section, the terms and themes are described in detail, along with descriptions of the photographs and the participants’ quotations.

Included terms

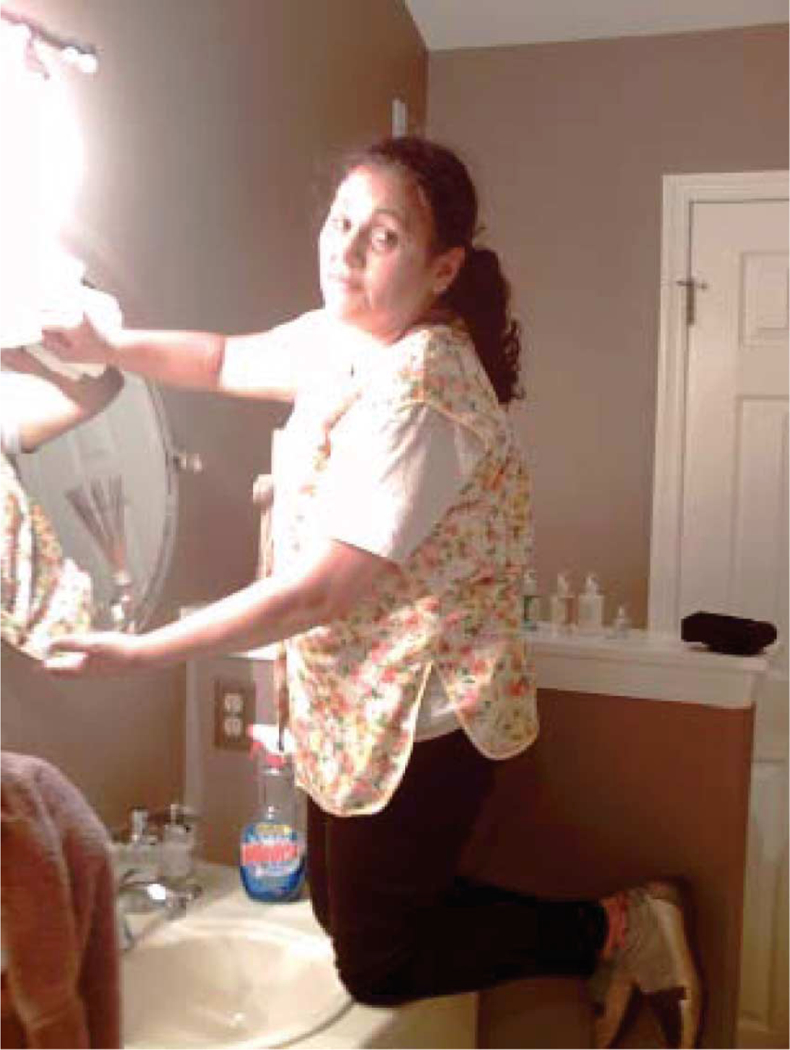

No time for myself

All of the women noted they typically took on as many jobs as they could fit into a day and scheduled the rest of their daily activities around work. Most of the jobs entailed heavy physical work, e.g. scrubbing floors, hanging mirrors and moving furniture. One informant described this as ‘the work that no one else wants to do’. The women reported being ‘exhausted’ by the end of her shift in a factory, which was her ‘day job’ (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

‘This is my friend. She and I are co-workers and this is our work. In this picture, I was taking a break from so much work and work and barely had time for anything else.’

Since they were still responsible for domestic duties at home, many of the women reported sleeping only three to four hours at night and eating meals on the run at fast-food restaurants and convenience stores. This schedule left little if any time for healthy self-care practices such as leisure-time physical activity. One respondent, faced with acknowledging her hectic lifestyle for the first time after viewing her photograph, verbalised her frustration with this arrangement (see Figure 4):

Figure 4.

‘I saw that all those pictures were taken of me working. I realised that I don’t have time for myself. I only have time to work.’

Living the life

The participants admitted that they envied other women who were able to arrange their time to engage in health-related behaviours, e.g. exercise. Free from work responsibilities outside the home and surrounded by the support of extended family members, several of the women reported having been more physically active in their home country. Only one woman, who worked as a caregiver for small children, currently had a schedule that allowed her to exercise in the morning before work and she walked frequently with the baby in a stroller. She was also the oldest member of the group and no longer had her own children living with her at home. She referred to her relative independence as ‘living the life’.

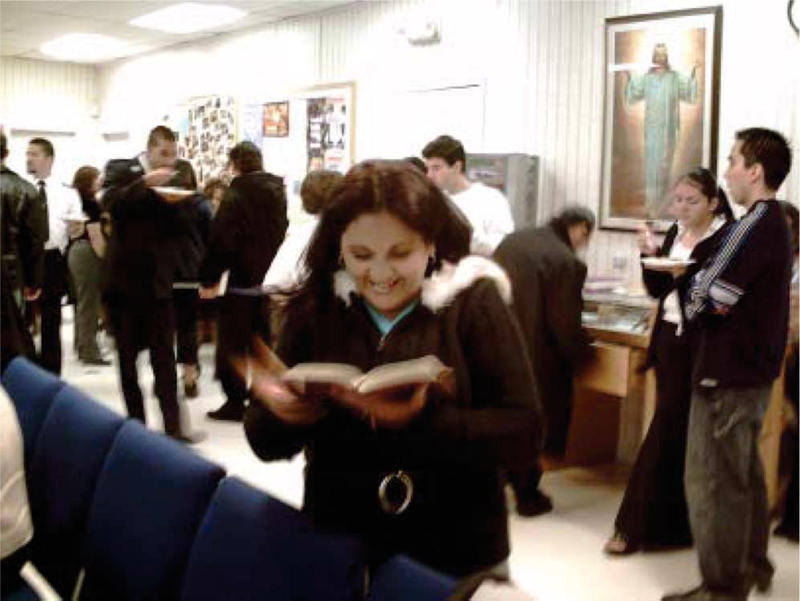

Work comes first

All of the subjects noted the economic necessity to put work ahead of everything else. Two of the women recalled going to work while ill because ‘they had no choice but to keep the job’. Most worked six days/week, taking only Sunday off to attend church services. One of the women selected a photograph in which she was smiling, the only such photograph taken of any of the women. When questioned about it, she explained her Pastor took the photograph of her as she was reading the Bible, which was her only form of relaxation (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

‘My pastor took this photograph of me while I was reading the Bible. Sunday is my only day off and reading the Bible is my only form of relaxation.’

Staying healthy

All eight of the women acknowledged that their lifestyles were unhealthy. Two of the photographs were taken while the women were preparing dinner, late at night. All were aware of the need to eat healthier foods, get sufficient rest and engage in some type of aerobic activity. Several were concerned that as they became older, they would not be able to maintain their health with this type of schedule. Three of the women related stories about female friends who were now suffering from severe health problems that should have been addressed in the earlier stages. One woman reflected:

This is why we need to go to the doctor when we don’t feel well. We should not say, ‘I need to go and clean a house.’

One woman acknowledged the influence of marianismo beliefs in the manner in which she handled illness in the family, both here and in her native country:

This issue we are discussing, ‘marianismo’, is seen in our countries a lot. If a child gets sick, then we run to the hospital with him … but if I get sick, I just deal with it.

Another woman admitted she rarely eats on a regular basis, saying (see Figure 6): Eventually, one woman summed up the feelings of the group when she said:

Figure 6.

‘We are in such a hurry to clean the houses that we don’t feel hunger, we don’t even feel the time. When you look at the clock, it’s already getting dark.’

We know this is no good for us. We are killing ourselves.

Cultural themes

Leisure time?

It became apparent through the photographs and discussion that the women in the group had little or no leisure time in which to engage in physical activity. Leisure time was seen as a luxury they could not afford. Many lost track of the hours in the day, going to work and coming home in the dark. Two of the women who still had high school aged children commented that after they returned from work, they still had to make dinner for their families and help with homework late into the night. One of these women commented that her only ‘free time’ was 2 a.m. in the morning. She selected a photograph that her husband took while she was watching television late at night (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

‘Even though I knew I need to sleep, I stayed up watching television because this is “my time.” The only time I have to myself is from about 11:30 p.m. to about 2 a.m. After that, I go to bed and then I get up around 5:45 a.m.’

Living in America

For the most part, the women believed that working long hours to save money and ‘get ahead’ was part of the American lifestyle. They commented that the owners of the homes where they worked also had long workdays and that ‘everyone here seems to be on the run all the time’. One of the women in the group was returning to her home in El Salvador that weekend, as her visa was expiring. In discussing her photograph, where she was scrubbing the floors of a large home, she exclaimed:

There is too much stress in this country. God willing, I am leaving on Saturday.

Feeling trapped

All of the women in the study acknowledged high levels of stress and unhappiness with their present lifestyle. This was obvious in their discussions as well as the photographs. However, giving up this existence meant depriving their families of needed funds, particularly money for college tuition for their children. These women described ‘feeling trapped’. What began as a short-term adaptation to contribute to the family income had grown into a long-term strategy that was draining them physically and emotionally.

Discussion

All of the women in the study verbalised that working long hours outside the home was the major obstacle to regular exercise. These findings are consistent with published studies that emphasise the impact of work on the lifestyles of immigrant Hispanic women (Juniu 2000, Easter et al. 2007). Ironically, the women in this study were working to contribute to their children’s college education, yet neglecting their own physical and emotional needs, which is consistent with the self-sacrificing nature of marianismo. In this example, marianismo both explains reality and becomes a strategy which women use to deal with reality (Ehlers 1991). The women believe that to be ‘good mothers’, they must work this hard to meet the needs of their families. At the same time, the reality of economic pressures forces them to make money the only way they know how, by putting together work from a series of low-paying, unskilled jobs. In this environment, the women are often more marketable than their husbands.

Even though the women were clearly prioritising family responsibilities above their own, perhaps the participants did not initially see this as typical marianista behaviour because the majority of the women had not been employed outside the home prior to immigrating to the USA. This may represent the ‘Nuevo marianismo’, an ‘Anglo twist’ on the traditional Latino/gender roles, coupled with the influence of socioeconomic pressures, to negatively influence women’s ability to engage in self-care activities such as physical activity. Alternatively, it may be argued that terms such as ‘machismo’ and ‘marianismo’ may have different meanings to immigrant Hispanic men and women because the expressions have been created by ‘outside’ researchers and are not part of everyday speech. Kinzer (1973) has noted the tendency for some researchers to cling to the machismo/marianismo model when interpreting data even when there is compelling evidence not to do so. Further research is needed to examine how various groups of immigrant Latinas accommodate work outside the home and balance family responsibilities with their own physical and emotional needs. Margarida Julia (1989) noted Puerto Rican women who seek to challenge and renegotiate their family’s expectations while maintaining strong connections within their families are often successful in balancing needs and expectations for self within their relationships with others.

Perhaps an even greater irony in this study is that all of the women were engaged in a series of part-time jobs, which often involved heavy physical labour. This finding is consistent with the previous published research (Ransdell and Wells 1998, Brownson et al. 2000), which suggests that Hispanic men and women accrue more physical activity through work and domestic chores than through leisure-time physical activity. Given the fact that work is seen as a survival strategy among immigrant populations, and that jobs requiring hard, physical labour are most often held by poor and minority populations (Ehrenreich 2001), the phrase ‘leisure-time physical activity’ can be seen to reflect an elitist mindset. Since the majority of public health recommendations for physical activity are based upon the notion of leisure-time physical activity (CDC 2008, American College of Sports Medicine [ACSM] 2009), total physical activity levels of Hispanic women may be substantially higher if work-related physical activity (WRPA) is included in the calculation. Future studies should assess the contribution of WRPA and household activities among low-income Latinas using more global measures of physical activity (Wareham et al. 2002).

An original assumption of the researchers was that middle-aged women, freed from the responsibilities of raising young children, might likely have more free time to engage in physical activity. This assumption was not supported in this study. First, three of the women in their mid-fifties still had teenagers at home, indicating that they bore their last child at age 40 or later. Although data from Latin America are scarce, the childbearing period for women from developing countries appears to be much longer than for those from industrialised nations (Lloyd 1986). Such women tend to have their first child at an early age and their last child at a relatively late age, thereby increasing the period of time they are engaged in childcare activities. Second, as the children became older, the informants in this study were freed up to work more hours outside the home to support the family. Therefore, these middle-aged women had no more leisure time available to them to engage in physical activity than younger women.

The combination of long work hours, poor eating habits, lack of sleep, chronic socioeconomic stress, lack of social support and little, if any, leisure time substantially increases the risk for cardiovascular events in these middle-aged women. Morbidity and mortality rates for cardiovascular disease are generally lower among Hispanic immigrants than among US-born non-Hispanics regardless of socioeconomic status, a phenomenon that has been dubbed ‘The Hispanic Paradox’ (Markides and Coreil 1986). However, cardiovascular mortality increases rapidly with acculturation. Given the increased prevalence of cardiovascular disease among successive generations of Hispanic immigrants, empowering interventions are sorely needed to address these issues among new immigrants (Sharma 2008).

Data from this study supported many of the findings of studies among immigrant groups in leisure constraints research. Although the socialisation of many Hispanic women to place family needs above their own is closely related to women’s feelings of lack of entitlement to leisure (Henderson 1990), it is necessary to examine this behaviour from the perspective of both gender and culture. As Gil and Vasquez (1996) has noted, women who espouse marianismo values are highly revered within traditional Latino cultures. There may be great pressure from within the family and community but also from the woman herself to maintain such behaviours upon immigration. Conflicts may occur when a woman attempts to reconcile marianismo beliefs with Anglo values such as independence and autonomy. Working too long and hard to find time for leisure activity has been reported in studies among Latin American immigrants (Juniu 2000) as well as other immigrant groups (Tsai and Coleman 1999, Stod- olska and Yi-Kook 2005). It has been suggested that immigrants with lesser degrees of assimilation/acculturation may be particularly prone to experience more work- related constraints (Stodolska 1998). Similarly, Comas-Diaz (1988) has observed that marianismo beliefs are often strongest in low-acculturated women. The subjects in this study differed greatly in the amount of time they had resided in the USA. Although some studies have reported that levels of leisure-time physical activity among Hispan- ics appear to increase with acculturation (Crespo et al. 2000), this may be less likely if socioeconomic status does not improve. Given the existence of the ‘Hispanic paradox’ longitudinal studies are needed to explore the long-term effects of acculturation on physical activity and weight gain, particularly among low-income Latinas. A potentially useful framework for encouraging salutogenic behaviours among immigrant Latinas is what Portes and Rumbaut (2006) refer to as selective acculturation. In this form of biculturalism, families selectively choose what to accept and reject from their home culture as well as from the host culture as needed. Lagana (2003) has observed that this approach can help women to reduce the stress associated with acculturation as well as to foster culturally appropriate health-promoting practices.

The results of this study demonstrate that Photovoice can be an effective strategy to empower individuals to identify the need to change unhealthy lifestyles and make the connection between situations and solutions. The visual impact of the photographs led several of the women to recognise the social influences that affected their lives and to acknowledge the need to make significant personal lifestyle changes. These steps towards individual and group empowerment were most evident in the comment:

We know this is no good for us. We are killing ourselves.

Empowerment education, as developed from the writings of Paulo Freire (Wallerstein and Bernstein 1988), emphasises that the process should not stop here. The final step in Friere’s problem-posing process focuses on the need for participants to take action at the community level. Empowerment strategies identified during the session included: (1) taking higher paying jobs with fewer working hours, (2) support groups for both immigrant men and women, and (3) assistance with childcare and domestic responsibilities, particularly from husbands. Because Hispanic women often seek employment in the domestic sphere, their work is largely ‘invisible’ to much of the outside world. Although the pay is generally poor, it is usually not difficult for these women to find work. This is in contrast to many of their husbands, who had all experienced periods of unemployment in the USA. Interestingly, although the women discussed the need to improve their work situations, none of them considered returning to school for additional education/training or English language skills, in order to secure a higher paying job, which may have afforded them more leisure time. In their study of leisure-time, household and work-related physical activity among White, Black and Hispanic women, He and Baker (2005) determined that differences in educational attainment accounted for virtually all of the racial and ethnic differences in leisure-time physical activity.

The difficulty of maintaining such chaotic lifestyles in mid-life became obvious when, a month after the study was completed, four of the eight women returned home to their native countries. This finding was unexpected, as the women’s ministry group had been rather stable during the previous two years that the PI had contact with the organisation. Although the precise reasons are not known, it is likely that a combination of socioeconomic pressures and escalating anti-immigrant sentiment within the community caused some of the women to return home. Current immigration patterns are clearly different than those of previous generations (Portes and Rumbaut 2006). Perhaps the women were able to endure much of the stress of immigration because they only saw it as a temporary lifestyle. As one subject reported:

You can come here, work as many jobs as possible for six months, then go home and have enough money for you and your family for the next five years.

Given the fact that empowerment is a long-term process (Wallerstein and Bernstein 1988), the relatively brief period of engagement was a major limitation of the study. Ideally the study should have continued after the Photovoice dialogue, but lack of resources to follow the women once they had left the USA led to closure of the study. Future studies should follow up with participants for at least six months after the Photovoice session. Another limitation of the study was that no quantitative method was used to triangulate the findings. A mixed method model would have added greater confidence in the results.

Qualitative methods, such as Photovoice, show great promise to assist researchers to build culturally appropriate practice theory and to design intervention strategies to ameliorate sedentarism and hypokinetic diseases among immigrant Hispanic women. Such approaches must integrate knowledge and action to improve the long-term health of community members.

Acknowledgements

This study was partially funded by a Faculty Research Grant from the College of Nursing, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. The authors would also like to thank the Salvation Army Bound Brook Corps for their assistance with this study.

References

- ACSM, 2009. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 8th ed Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth BE, 2000. Issues in the assessment of physical activity in women. Research quarterly for exercise and sport, 71 (Suppl. 2), S37–S42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez RR, 1993. The family In: Kanellos N, ed. The Hispanic American Almanac: a reference work on Hispanics in the United States. Detroit, MI: Gale Research, 151–173. [Google Scholar]

- American Heart Association, 2008. The heart truth for women. Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/hearttruth/press/nhlbi_04_age_fact.htm [Accessed 30 May 2008].

- Arab-Moghaddam N, Henderson KA, and Sheikholeslami R, 2007. Women’s leisure and constraints to participation: Iranian perspectives. Journal of leisure research, 39, 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Bedini LA and Guinan DM, 1996. If I could just be selfish: caregivers’ perceptions of their entitlement to leisure. Leisure sciences, 18, 227–240. [Google Scholar]

- Booth FW, et al. , 2002. Waging war on physical inactivity: using modern molecular ammunition against an ancient enemy. Journal of applied physiology, 93, 3–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, et al. , 2000. Patterns and correlates of physical activity among US women 40 years and older. American journal of public health, 90, 264–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC, 2003. Youth risk behavior surveillance (YRBS). Atlanta, GA. U.S: Department of Health and Human Services, CDC. [Google Scholar]

- CDC, 2008. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system (BRFSS). Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/ [Accessed 10 June 2008].

- Chick G and Dong E, 2003. Possibility of refining the hierarchical model of leisure constraints through cross-cultural research. Proceedings of the 2003 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium (Gen Tech Rep NE-317) Newtown Square, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station. [Google Scholar]

- Cianelli R, Ferrer L, and McElmurry BJ, 2008. HIV prevention and low-income Chilean women: machismo, marianismo and HIV misconceptions. Culture, health & sexuality, 10 (3), 297–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cofresi NI, 2002. The influence of Marianismo on psychoanalytic work with Latinas: transference and countertransference implications. Psychoanalytic study of the child, 57, 435–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Diaz L, 1988. Feminist therapy with Hispanic/Latina women: myth or reality? Binghampton, NY: Hayworth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford DW, Jackson EL, and Godbey GC, 1991. A hierarchical model of leisure constraints. Leisure Sciences, 13, 309–320. [Google Scholar]

- Crespo CJ, et al. , 2000. Race/ethnicity, social class and their relation to physical inactivity during leisure time: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. American journal of preventive medicine, 18, 46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, 2009. Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods approaches. 3rd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alonzo KT and Fischetti N, 2008. Cultural beliefs and attitudes of Black and Hispanic college-age women toward exercise. Journal of transcultural nursing, 19 (2), 175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easter M, et al. , 2007. Una mujer trabaja doble aqui: vignette-based focus groups on stress and work for Latina blue-collar women in Eastern North Carolina. Health promotion practice, 8 (1), 48–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton CB, et al. , 1995. Physical activity, physical fitness, and coronary heart disease risk factors. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 27 (3), 340–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers TB, 1991. Debunking marianismo: economic vulnerability and survival strategies among Guatemalan wives. Ethnology, 30 (1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich B, 2001. Nickle and dimed: on (not) getting by in America. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Evenson KR, et al. , 2002. Environmental, policy and cultural factors related to physical activity among Latina immigrants. Women and Health, 36 (2), 43–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falicov CJ, 1996. Mexican families In: McGoldrick M, Giordano J, and K Pearce J, eds. Ethnicity and family therapy. New York: Guilford Press, 169–182. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd MF, 1998. Getting beyond marginality and ethnicity: the challenge for race and ethnic studies in leisure research. Journal of leisure research, 30 (1), 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Frake CO, 1962. The ethnographic study of cognitive systems In: Gladwin LT and Sturtevant WC, eds. Anthropology and human behavior. Washington, DC: Anthropological Society of Washington, 72–93. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P, 1970. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Seabury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P, 1973. Education for critical consciousness. New York: Seabury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo ML, 2002. Picture this: immigrant workers use photography for communication and change. Journal of workplace learning, 14 (2), 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gil RM and Vasquez CI, 1996. The Maria paradox. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Green E and Hebron S, 1988. Leisure and male partners In: Wimbush E and Talbot M, eds. Relative freedoms: women and leisure. Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Grunbaum J, et al. , 2004. Youth risk surveillance - United States. Surveillance summaries: morbidity and mortality weekly report, 53, 1–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He XZ and Baker DW, 2005. Differences in leisure-time, household, and work-related physical activity by race, ethnicity, and education. Journal of general internal medicine, 20 (3), 259–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson KA, 1990. The meaning of leisure for women: an integrative review of the research. Journal of leisure research, 22, 228–243. [Google Scholar]

- Himmelgreen DA, et al. , 2003. The longer you stay, the bigger you get: length of time and language use in the U.S. are associated with obesity in Puerto Rican women. American journal of physical anthropology, 125 (1), 90–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson EL, 1991. Special issue introduction: leisure constraints/constrained leisure. Leisure sciences, 13, 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson EL and Henderson KA, 1995. Gender-based analysis of leisure constraints. Leisure sciences, 17, 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Juniu S, 2000. The impact of immigration: leisure experiences in the lives of South American immigrants. Journal of leisure research, 32, 358–381. [Google Scholar]

- Keller C, Fleury J, and Rivera A, 2007. Visual methods in the assessment of diet intake in Mexican American women. Western journal of nursing research, 29 (6), 758–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzer NS, 1973. Priests, machos, and babies: or, Latin American women and the Manichaen heresy. Journal of marriage and the family, 35 (2), 300–312. [Google Scholar]

- Koya DL and Egede LE, 2007. Association between length of residence and cardiovascular disease risk factors among an ethnically diverse group of United States immigrants. Journal of general internal medicine, 22 (6), 841–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagana K, 2003. Come bien, camina y no se preocupe - eat right, walk, and do not worry: selective biculturism during pregnancy in a Mexican American community. Journal of transcultural nursing, 14 (2), 117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd CB, 1986, July Women’s work and fertility, research findings and policy implications from recent United Nations research. Unpublished paper presented at the Rockefeller Foundation’s Workshop on Women’s Status and Fertility, Mt. Kisco, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Margarida Julia MT, 1989. Developmental issues during adulthood: redefining notions of self, care and responsibility among a group of professional Puerto Rican women In: T Garcia Coll C and de Lourdes Mattei M, eds. The psychosocial development of Puerto Rican women. New York: Praeger, 115–140. [Google Scholar]

- Markides K and Coreil J, 1986. The health of Hispanics in the southwestern United States: an epidemiologic paradox. Public health reports, 101 (3), 253–265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M and Wallerstein N, 2003. Introduction to community-based participatory research In: Minkler M and Wallerstein N, eds. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics, 2007. Health, United States, 2007 with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes A and Rumbaut RG, 2006. Immigrant America: a portrait. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ransdell LB and Wells CL, 1998. Physical activity in urban white, African-American, and Mexican-American women. Medicine science in sports and exercise, 30 (11), 1608–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF and Owen N, 1998. Physical activity and behavioral medicine. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, 2008. Physical activity interventions in Hispanic American girls and women. Obesity reviews, 9 (6), 560–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradley JP, 1979. The ethnographic interview. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens ED, 1973. Marianismo: the other face of machismo in Latin America In: Decastello A, ed. Female and male in Latin America. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Stodolska M, 1998. Assimilation and leisure constraints: dynamics of constraints on leisure in immigrant populations. Journal of leisure research, 30 (4), 521–551. [Google Scholar]

- Stodolska M and Yi-Kook J, 2005. Ethnicity, immigration and constraints In: Jackson EL, ed. Constraints to leisure. State College, PA: Venture Publishing, 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai EH and Coleman DJ, 1999. Leisure constraints of Chinese immigrants: an exploratory study. Loisir et Sociele/Society and leisure, 22, 243–264. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1996. Physical activity and health: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef MJ and Love EJ, 1994. Women and exercise participation: the mixed blessing of motherhood. Health care women international, 7, 10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker GJ, Jackson EL, and Deng J, 2007. Culture and leisure constraints: a comparison of Canadian and mainland Chinese university students. Journal of leisure research, 39 (4), 567–590. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N and Bernstein E, 1988. Empowerment education: Freire’s ideas adapted to health education. Health education and behavior, 15 (4), 379–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N and Sanchez-Merki V, 1994. Freirian praxis in health education: research results from an adolescent prevention program. Health education research, 9, 105–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, 2005. Photovoice: social change through photography. Available from: http://www.photovoice.com/index.html [Accessed 16 June 2008].

- Wang CC and Pies CA, 2004. Family, maternal and child health through Photovoice. Maternal and child health journal, 8 (2), 95.–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC and Redwood-Jones YA, 2001. Photovoice ethics: perspectives from Flint Photovoice. Health education and behavior, 28 (5), 560–572, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wareham NJ, et al. , 2002. Validity and repeatability of the EPIC-Norfolk physical activity questionnaire. International journal of epidemiology, 31, 168–174 Weber, R. P., 1990. Basic content analysis. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]