Abstract

ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters comprise a family of critical membrane bound proteins functioning in the translocation of molecules across cellular membranes. Substrates for transport include lipids, cholesterol and pharmacological agents. Mutations in ABC transporter genes cause a variety of human pathologies and elicit drug resistance phenotypes in cancer cells. ABCA2, the second member the A subfamily to be identified, was highly expressed in ovarian carcinoma cells resistant to the anti-cancer agent, estramustine, and more recently, in human vestibular schwannomas. Cells expressing elevated levels of ABCA2 show resistance to variety of compounds, including estradiol, mitoxantrone and a free radical initiator, 2,2’-azobis-(2-amidinopropane). ABCA2 is expressed in a variety of tissues, with greatest abundance in the central nervous system and macrophages. This transporter, along with other proteins that have a high degree of homology to ABCA2, including ABCA1 and ABCA7, are up-regulated in human macrophages during cholesterol import. Recent studies have shown ABCA2 also plays a role in the trafficking of low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-derived free cholesterol and to be coordinately expressed with sterol-responsive genes. A single nucleotide polymorphism in exon 14 of the ABCA2 gene was shown to be linked to early onset Alzheimer disease (AD) in humans, supporting an earlier study showing ABCA2 expression influences levels of APP and β-amyloid peptide, the primary component of senile plaques. Studies thus far implicate ABCA2 as a sterol transporter, the deregulation of which may affect a cellular phenotype conducive to the pathogenesis of a variety of human diseases including AD, atherosclerosis and cancer.

Keywords: ABC transporters, drug resistance, estramustine, cholesterol, Alzheimer disease

INTRODUCTION

ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters are multi-domain membrane proteins that use energy from ATP-hydrolysis to pump substrates directionally across cellular membranes [1]. The human ABC superfamily of proteins consists of at least seven sub-families: A (ABC1); B (MDR/TAP); C (CFTR/MRP); D (ALD); E (OABP); F (GCN20); G (WHITE). Members of these sub-families demonstrate great diversity in tissue expression and cellular functions. Expression patterns are also influenced by genetic polymorphisms, some of which have been associated with a variety of human disease pathologies. Reports have shown at least 605 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) among 13 ABC transporter genes [2].

ABC transporters have a generic structure that is minimally composed of four domains; two transmembrane domains and two ATP binding cassettes (ABC) [3]. The ABC consensus sequence, or nucleotide binding domain (NBD), is the hallmark of the ABC protein superfamily. This ABC is comprised of the highly conserved Walker A and B motifs separated by 90–120 amino acids and an intervening “signature” motif [4]. Both ABCs are capable of hydrolyzing ATP. Inhibition of hydrolysis of one can abrogate the activity of the other and thus, both domains function in an alternating fashion while recognizing diverse nucleotides as hydrolytic substrates. Membrane domain topology analysis has shown that between 6 and 11 transmembrane helices exist within these transporters [5] and the function of these domains may be in substrate recognition, binding, and channeling. ATP hydrolysis in the ABC domain provides the necessary energy for substrate transport. As evidenced by infrared and fluorescence spectroscopic data, substrate binding and ATP hydrolysis induce conformational changes in the transporter family [6]. Thus, the interactions between the ABC and membrane domains are integral in executing energy dependent transport.

Within the A sub-family of ABC transporters, 12 members have thus far been identified. Although the sequences of ABCA proteins share a great deal of homology, their in vivo functions and pathologies resulting from transporter mutations are diverse (Table 1). Although the focus of this review is the A2 transporter, general links with other ABC transporters are discussed. For a broader understanding of ABC transporters, we direct the reader to more comprehensive reviews [7–11].

Table 1.

Summary of Subfamily A of ABC Transport Proteins

| Protein | Chromosome | Expression | Function | Pathology/Disease Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | 9q31.1 | Ubiquitous | Cellular lipid efflux | Tangier disease |

| A2 | 9q34.3 | CNS, PNS, macrophages, reproductive tissues | Cholesterol homeostasis | Vestibular schwannomas, Alzheimer disease |

| A3 | 16pl3.3 | Lung alveolar type II cells | Lipid transport | Neonatal surfactant deficiency |

| A4 | Ip22.1 | Retina | Flippase of n-retinylidene-phosphatidylethanolamine | Stargardt disease; Retinitis pigmentosa 19; Age-related macular degeneration |

| A5 | 17q24.3 | Cardiomyocytes, follicular cells | Cholesterol homeostasis | Dilated cardiomyopathy |

| A6 | 17q24.2–3 | Ubiquitous | Cholesterol homeostasis | Unknown |

| A7 | 19pl3.3 | Myelolymphatic tissue, spleen | Cellular lipid efflux | Sjorgren syndrome |

| A8 | 17q24.2 | Heart, skeletal muscle, and liver | Xenobiotic transporter | Unknown |

| A9 | 17q24.2 | Macrophages heart, brain, and fetal tissues | Macrophage differentiation and lipid homeostasis | Unknown |

| A10 | 17q24.3 | Macrophages heart, brain, GI tract | Macrophage differentiation and lipid homeostasis | Unknown |

| A12 | 2q35 | Keratinocytes | Cellular lipid storage and secretion | Lamellar Type II & Harlequin ichthyosis |

| A13 | 7ql2.3 | Kidney, skeletal muscle | Unknown | Unknown |

ABCA2

ABCA2 (270 kD) is the largest of 48 identified members of the ATP-binding cassette transporter gene family (Fig. 1) [12]. This transporter was originally discovered along with ABCA1 in embryonic mouse brain [13, 14] and later studies showed that a partial-sequence human cDNA clone, highly similar to mouse ABCA2, was more prevalent in brain than in other tissues. The subsequent characterization of the full-length human ABCA2 cDNA and its detailed expression pattern showed the highest levels in fetal and adult brain, spinal cord, ovary, prostate and leukocytes [15, 16]. Expression of ABCA2 has been detected in other tissues, including lung, kidney, heart, liver, skeletal muscle, pancreas, testis, spleen, colon and fetal liver. Cellular immunolocalization of ABCA2 revealed a distinct, punctate staining corresponding to vesicles that were hypothesized to be peroxisomes. Further analysis using vesicle-specific antibodies revealed a colocalization of ABCA2 with late endolysomes and transgolgi organelles [15].

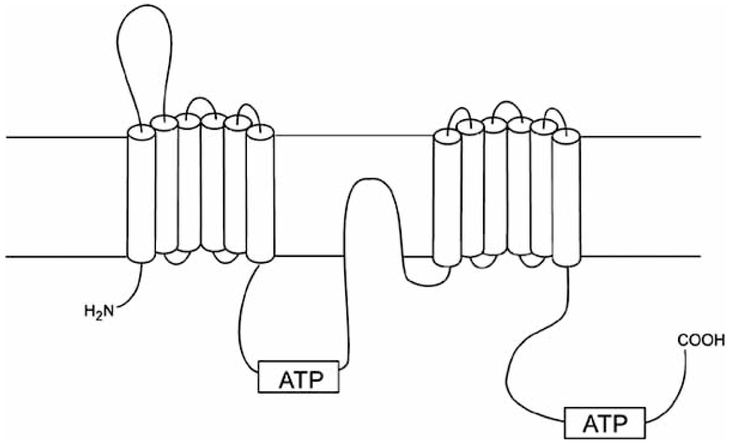

Fig. (1).

Predicted membrane topology of the ABCA2 transporter. ABCA2 sequence data were applied to Kyle-Doolittle hydrophobicity analysis using Genetics Computer Group (version 9.1; Madison, WI) and McVector software (Oxford Molecular, Oxford, UK). Transmembrane domains were predicted using TopPred 2 analysis. Shown is a schematic of the predicted membrane topology of ABCA2 in the intraorganellar membrane. The extracellular and intracellular domains, respectively, are depicted above and below the horizontal lines representing a phospholipid bilayer. (Figure adapted from Vulevic et al. 2001[15]).

The ABCA2 gene is located at chromosome 9q34 within a genomic region of 21 kb [17]. The gene contains 48 exons with an open reading frame of 2436 amino acids [15, 18]. The minimal promoter region has been mapped to 321 bp upstream of the translation start site [19]. Alternative splicing of the first exon to the second in ABCA2 results in two variants, 1A and 1B [16]. The first exon of 1B contains the coding sequence for 52 amino acids and is located 699 bp upstream of 1A, which contains coding sequence for 22 amino acids. Both splice variants co-localize with lysosome-associated membrane proteins-1 and −2 (LAMP-1 and −2) and share similar expression profiles [16]. The novel N-terminus of ABCA2 splice variants, while functionally redundant, may provide subtle gene regulatory differences to allow tissue-specific or temporal-specific protein expression during differentiation and/or development.

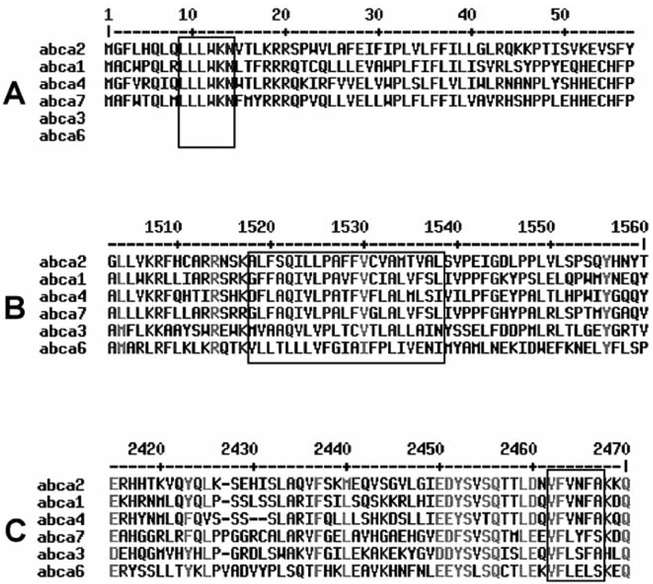

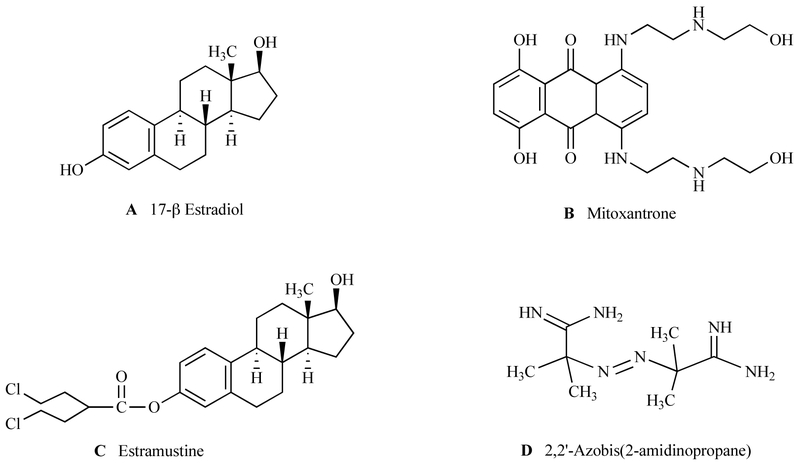

ABCA2 shares the most homology with other A subfamily proteins, including ABCA1 (50%) ABCA7 (44%), ABCA3 (43%), ABCA4 (40%) and ABCA6 (32%) [20] (Fig. 2). Induction and repression of ABCA1 has been extensively characterized. Promoter elements identified in ABCA1 include an E box, AP-1, liver X receptor (LXR) element and SP1 motifs [21]. The proximal promoter of ABCA2 contains two GC-boxes and overlapping sites for the early growth response-1 (EGR-1) and Sp1 transcription factors [19]. Identical regions contained in ABCA1 and ABCA2 include two cytoplasmic ATP binding cassettes, Walker domains, a conserved N-terminal sequence (LLLWKN) and a VFVNFA motif within the C-terminal domain [22] (Fig. 2). The VFVNFA motif in ABCA1 is critical for apolipoprotein A-I binding and HDL cholesterol efflux [22]. The ABCA2 sequence contains a lipocalin signature motif, which suggests a function in the transport of lipids, steroids and structurally similar molecules, such as estramustine and estradiol (Fig. 3). [23]. Additional studies, as discussed below, led to the conclusion that ABCA2 may play a functional role in cellular lipid homeostasis.

Fig. (2).

Alignment of ABCA transporters with high homology to ABCA2. The alignment is shown in descending order of homology with ABCA2 with (A) the conserved LLWKN motif at the N-terminus of unknown function, (B) a highly hydrophobic domain (residues 1457–1477 for ABCA2) and (C) highly conserved domain at the C-terminus. The sequence alignment was conducted using MultAlin software [119].

Fig. (3).

Putative substrates of ABCA2 transport.

CHOLESTEROL HOMEOSTASIS AND METABOLISM

Several of the ABC sub-family A members play a role in cholesterol homeostasis (Table 1). Specifically, ABCA1 and ABCA7, transporters that not only share the greatest homology with ABCA2 (Fig. 2), but are also sterol responsive genes that function in cholesterol metabolism [20]. Cholesterol homeostasis is maintained by a feedback mechanism of de novo synthesis using acetyl CoA and by uptake of low density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol by receptor-mediated endocytosis through the LDL receptor (LDLR) [24]. Functional studies using exogenous, labeled low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol provided evidence for ABCA2 function in sterol trafficking [25]. Forced ABCA2 overexpression was used as a model system in Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHOA2) to test the effect on transport of LDL-cholesterol. CHOA2 cells displayed a more intense staining of unesterified cholesterol using the fluorescent marker, filipin, in cytoplasmic and perinuclear vesicles, compared to the parental cell line (CHO). These vesicles were also positive for an endosome/lysosome acidic vesicle marker (Lysosensor green 189), with less intense filipin staining at the plasma membrane [25]. In addition to the sequestration of LDL-derived cholesterol into these vesicles, CHOA2 cells have also been shown to have elevated expression of the LDL receptor, sterol-response element binding protein-2 (SREBP2) and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA synthase (HMGCoA S) and demonstrate reduced trafficking of LDL-derived cholesterol to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) for esterification [25]. Since these cellular responses also occur when cells are grown under sterol-depleted conditions, these data suggest that ABCA2 up-regulation mimics sterol deprivation. LDLR (along with HMGCoA S and SREBP2) is regulated by the SREBP2 transcription factor [26]. The transcription of LDLR is reduced in CHOA2 cells with a mutant SREBP2 binding site within the LDLR promoter [19]. Taken together, these results show that ABCA2 over-expression causes a phenotype similar to cholesterol-depleted cells that sequester unesterified cholesterol into endolysosomal compartments.

Significant insight into the importance of cholesterol homeostasis has been gleaned from pre-clinical studies of ABCA1. For example, ABCA1 deficient mice have a ~70% decrease in serum cholesterol, phospholipids and lack HDL [27], while transgenic overexpressing mice show an increase in cholesterol efflux [28]. Cholesterol lowering agents, such as statins, repress ABCA1 expression, suggesting a beneficial effect on reversing the cholesterol transport pathway [29]. The significance of ABCA1 and dysregulation of cholesterol metabolism is noted in the mouse model for diabetes with associating cardiovascular disease. ABCA1 expression is decreased in diabetic mice with cardiovascular disease [30]. Although the generation of mouse models for other ABC A sub-family transporters began only recently [31–33], there will undoubtedly be increasing numbers of genetic models that should help to elucidate in vivo functions and genetic links with human disease.

TRANSPORTER MUTATIONS AND HUMAN DISEASE

Many ABC transporters play critical roles in the cellular efflux of endogenous or xenobiotic substrates, and the dysfunction of many of these proteins has been implicated in a number of clinical disorders. The first ABC protein to be cloned and identified, the multidrug transporter/P-glycoprotein (MDR1 or Pgp1, 7q21), a member of the B subfamily, is expressed in intestinal mucosa, liver, adrenal gland and kidney and at pharmacologic barriers including the blood-brain barrier and placenta [34, 35]. Increased MDR transporter activity can result in the efflux of a variety of agents, serving as a mechanism of drug resistance in tumor cells. In addition, deregulated MDR1 is associated with diseases such as Crohn’s, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s as well as HIV therapy drug resistance [36]. The MDR1 gene product, Pgp, limits the delivery of anti-viral drugs to the central nervous system (CNS) and lymphatic system, both of which provide shelter for viruses during treatment [36]. Several polymorphisms have been characterized, many of which result in the over-expression of Pgp [36]. The absence of functional transporter subunits associated with antigen processing (AbCb2 and ABCB3), has been linked with different forms of HLA class I deficiency syndrome [37].

Overexpression of an ABC transporter C sub-family member, human multidrug resistance associated protein, MRP1, was identified as a contributor in the majority of non-Pgp related resistance phenotypes, where hydrophobic anticancer and glutathione-conjugated agents were concerned [38, 39]. MRP1 expression occurs predominantly in lung, testes, erythrocytes, and basolateral membrane of epithelial cells. There are approximately 20 characterized polymorphisms of MRP1 [8], many associated with multidrug resistance in cancer. Impaired function of the cyclic AMP-activated ABCC7 (CFTR, 7q31.2) chloride channel, another member of the C-subfamily, appears to be the basic defect in epithelial and non-epithelial cells derived from cystic fibrosis (CF) patients [40]. A single amino acid deletion at F508 in CFTR is responsible for the majority (70%) of reported CF cases, although over 800 polymorphisms have been identified [7]. The CFTR gene product forms a cAMP-activated chloride channel and has also been shown to have activity as a Cl−/HCO3− exchanger [41]. Mutation in CFTR disrupts exocrine function in tissues including the intestine, bronchus, biliary tree, and sweat glands and causes infertility in both sexes [7].

Some mutations in the peroxisomal membrane halftransporter ABCD1 (ALDP), in the D subfamily of transporters, are associated with abnormal peroxisomal ß-oxidation of saturated, very long chain fatty acids, and can result in the neurodegenerative disorder X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) [42]. ALD is characterized by the accumulation of hexacosanoate (C26) and other saturated fatty acids with cholesterol esters in the white matter of the CNS [43]. ABC transporter mutations in the OABP gene (4q31), can impede the antiviral activity of RNAse L enzyme during HIV infection [44].

Many of the consequences of altered ABC transporter function also involve the deregulated flux of cholesterol and phospholipids. ABCG1, also called ABC8, localizes to perinuclear structures within macrophage foam cells of Tangier disease patients and also within foam cells associated with atherosclerotic plaques [45]. Within the A subfamily (and prior to this finding within the G subfamily), ABCA1 was shown to be mutant in Tangier disease and familial HDL deficiency [46, 47]. The hallmarks of these hereditary hyper-cholesteremias are a paucity of circulating HDL, accumulation of cholesterol in macrophages (in Tangier) and a predisposition to atherosclerosis [48–50]. Uehara et al. proposed that down-regulation of ABCA1 by unsaturated fatty acids and acetoacetate may lead to decreased high density lipoprotein (HDL) and therefore increase cardiovascular disease observed in diabetic patients [30]. ABCA3, also a cholesterol responsive transporter, plays an important role in pulmonary lipid (surfactant) production in type II alveolar cells [51]. Deficiency in this protein results in neonatal respiratory failure [52]. ABCA3 expression was elevated in bone marrow from acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients [53], suggesting the impact of ABCA3 deregulation may extend into cancer development.

Another cholesterol-responsive A subfamily transporter, ABCA7 was determined to be an autoantigen epitope of Sjogren’s syndrome [54]. Expression is most abundant in myelolymphatic tissue and spleen. Like its relative, ABCA1, this transporter also binds to apolipoproteins and promotes cholesterol and phospholipid efflux [55]. Data obtained from ABCA7-null mice show that this transporter is not required for normal cholesterol and phosphatidylcholine removal from macrophages, but that the deficiency of ABCA7 reduces HDL and total serum cholesterol levels [33]. ABCA7 overexpressing cells were used to uncover a role for ABCA7 in the reorganization of lipids during differentiation of keratinocytes [56].

Analysis of ABCA2 expression in various cell lines provides insight into the potential role in multiple disease states. ABCA2 was elevated in Niemann-Pick type C1 (NPC1) fibroblasts and in Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FHC) fibroblasts [25], as well as several cancer cell lines including an estramustine-resistant prostate cancer cell line, EM15 [50]; Table 2). High expression of this transporter was shown in human vestibular schwannomas [57], derived from PNS, a tissue that has a high basal expression of ABCA2. Although ABCA2 is expressed predominantly in normal and malignant CNS tissues and cell lines, it is also abundant in several other cancer cell lines derived from non-CNS tissues. Tumor cells that overexpress ABCA2 are highlighted in Table 2 and include lines from lung, breast, CNS, renal, melanoma, prostate, ovarian, leukemic, and colon. As illustrated, ABCA2 expression is variable across tissues in vivo and is highly expressed in a variety of tissue types among cancer cell lines suggesting a putative role for the deregulation of ABCA2 in tumorigenesis and/or cancer progression regardless of the expression pattern of non-cancerous tissue. The role of this transporter in cancer development and/or chemotherapy resistance remains a subject of future study.

Table 2.

ABCA2 Expression in Various Cancer and Normal Cell Lines

The abundant expression of ABCA2 in oligodendrocytes is purported to be required for the generation of copious layers of phospholipid- and cholesterol-rich myelin sheath of white matter in the brain [58, 59]. The association of ABCA1 and ABCA2 expression, polymorphisms and/or mutations with AD may implicate these transporters as a target for future therapeutic strategies for this neurodegenerative disease. Although several recent lines of evidence implicate a role of ABCA2 in disease pathology, to date, no functional link between the transporter and AD or cancer has been delineated.

THE ALZHEIMER DISEASE LINK TO ABCA1 AND ABCA2

Alzheimer disease, the most common neurological pathology associated with dementia, affects approximately 15 million people across the globe [60]. AD manifests itself by the accumulation of extracellular senile plaques in neurofibrillary tangles of the brain and also in cerebral blood vessels. These plaques are composed of both fibrillar and non-fibrillar forms of β-amyloid peptide (Aβ) and result in the loss of neuronal function in limbic and association cortices of the brain [61]. The Aβ peptide is derived from sequential cleavage reactions of amyloid precursor protein (APP) by a β-secretase, followed by cleavage by a γ-secretase within the transmembrane domain of APP. Normal function of APP remains to be determined, however some evidence points towards a role in the blood coagulation pathway [62] and the cytoplasmic domain of APP may act in signaling via interactions with cytoplasmic adaptor proteins [63, 64].

Approximately 40% of early-onset AD cases (in individuals younger than 60 years) are linked to mutation in the β-amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin1 (PSEN1), or presenilin2 (PSEN2) [65]. Late-onset AD occurs in patients older than 60 and accounts for nearly 95% of all AD cases. Several genes have shown a slight, but inconsistent association with this disease [66], but the most common of these is the ε4 isoform of APOE [61, 67]. APOE is the most abundant apolipoprotein in the brain and the main protein constituent of very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL). Another genetic polymorphism associated with AD is a chief factor in cholesterol catabolism in the brain, CYP46A1 [68]. Consistent with these finding is the mounting epidemiological and genetic research that has drawn a close link between AD pathology and cholesterol [60, 69–71]. Mid-life individuals with elevated serum cholesterol have an increased risk of developing AD [72] and treatment with statins, cholesterol lowering agents, is associated with a decreased risk of AD development [73, 74] and a decrease in Aβ levels [71, 75, 76].

ABCA1 is a key transporter in the cellular efflux of high density lipoprotein (HDL) and influences the age of AD onset and cholesterol levels within cerebrospinal fluid [77]. Tangier disease patients, harboring mutations in ABCA1, are typically shown to have reduced plasma HDL levels and a concomitant increase in the risk for AD development [77, 78]. The literature provides an abundance of studies showing the connection between the dysregulation of cholesterol metabolism and AD [73].

As a cholesterol-responsive gene expressed predominantly in the brain, ABCA2 became an excellent candidate for an association with AD when it was recently shown to impact the production of Aβ [15, 18, 20, 25, 79]. Not only did ABCA2 co-localize with Aβ and APP [79], its overexpression also caused an up-regulation of a number of genes associated with resistance to oxidative stress. Using amplified differential gene expression (ADGE) microarray, several clusters of genes were shown to be differentially regulated upon ABCA2 over-expression in HEK293 cells, including 22 genes related to transport, membrane homeostasis, cell metabolism and substrate binding. Six of the genes from this study, APP, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein, calcineurin, seladin-1, vimentin and Slc23a1, are commonly associated with AD and response to oxidative stress. Overexpression was also shown to confer a slight resistance to oxidative stress rendered by the free radical initiator, AAPH (2, 2′-azobis-(2-amidinopropane). ABCA2 levels were shown to be elevated in the temporal and frontal regions of the brain, areas frequently associated with AD pathology. Recently, a synonymous SNP in exon 14 of ABCA2 (rs908832) was determined to have a significant linkage with early-onset AD [80, 81] and an impact on cholesterol in cerebrospinal fluid [81]. This transporter was also shown to localize in specific areas of the brain associated with adult neurogenesis and AD pathology (subventricular zone lining of the lateral ventricles and the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus) and in GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons [82]. The authors proposed a potential role of ABCA2 in regulating levels of membrane cholesterol for cell proliferation, differentiation and synaptogenesis and potentially, extracellular release of endolysosomal Aβ [82]. Interestingly dysregulation of cellular cholesterol metabolism [73] and endolysosomal function [83, 84] are both well-established indicators of early AD pathology; however, their causal relationship is still unclear. Taken together, these studies reflect the importance of determining a mechanistic role for ABCA2 in AD pathogenesis and/or progression. However, because membrane cholesterol homeostasis and lipid raft maintenance is critical to proliferating cell populations, the ABCA2 protein may impact the development and/or progression of human cancers.

POTENTIAL LINK OF ABCA2 WITH CANCER

Defects in cholesterol metabolism and LDL regulation have been associated with many forms of cancer including prostate [85], breast [86], pancreatic [87], squamus cell and small cell lung cancer [88]. Abnormal feedback regulation of LDL receptor expression by exogenous LDL is observed in several prostate tumor cell lines [89, 90]. Similarly, decreased feedback of regulation of LDL-receptor activity by sterols is observed in leukemia cells from patients with acute myelogenous leukemia [91] and in human colorectal cells and colorectal adenocarcinoma biopsies [92]. LDL is the primary carrier of essential PUFAs, [e.g. linoleic acid (LA) and arachidonic acid (AA)] [93]. The AA released from LDL is converted to the eicosanoid prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) through the action of cyclooxygenase-2 [94]. PGE2 released from cells can act in an autocrine and paracrine manner through the EP4 receptor to induce the expression of immediate early genes, among them c-fos, the transcriptional activity of which supports cell proliferation [95].

Hormone therapy of cancer patients has been shown to influence cholesterol metabolism [96, 97]. Cholesterol also has critical functions in cell signaling, survival and differentiation [98] and may provide a novel target for cancer therapeutic agents [99] since cholesterol levels may be a limiting factor in membrane maintenance in rapidly dividing cancer cells. In vivo expression of ABCA2 has been illustrated in tissues requiring high levels of sterols and hormones, specifically the central and peripheral nervous system, and reproductive tissues such as prostate, ovary and uterus.

The only evidence, thus far, of ABCA2 over-expression in human cancer is from vestibular schwannoma biopsies (tumors derived from the vestibular branch of the acoustic nerve) [57]. Recently, ABCA2 protein was shown to localize in areas of the brain associated with adult neurogenesis and to co-localize at “microtubule organizing centers” during mitosis [82]. The potential role of ABCA2 has been proposed in regulating availability of cholesterol for cell growth, differentiation and synaptogenesis [82]. As such, this transporter may function to regulate the availability of cholesterol as a critical metabolite in both normal and malignant cellular proliferation.

Overall, accumulating evidence has indicated that ABCA2 expression and subsequent endolysosomal compartmentalization of sterols is directly linked to cancer drug resistance [15, 16, 100] and may be an important regulator to maintain homeostatic levels of cholesterol for cellular function, growth and membrane integrity [15, 101]. In addition, ABCA2 has been shown to be a sterol responsive gene in macrophages. Recently, a group proposed that specific properties of lysosomes within cancer cells could provide a novel target for cancer chemotherapeutic agents [102]. Perhaps a plausible role for ABC transporters as functional members of dynamic protein complexes (rather than simple substrate transporters) in the processes of cell growth, differentiation and death has, thus far, been overlooked.

ABCA2 EXPRESSION AND CELLULAR DRUG RESISTANCE

Adaptation of cancer cells to a single chemotherapeutic agent can render pleiotropic cellular effects and result in resistance to a specific drug or to a larger class of chemical compounds. This second form of resistance is appropriately termed multidrug resistance (MDR). The current strategy for cancer chemotherapy involves cocktails of pharmacological agents and MDR may be a cause of treatment failure. ABC transporters have been implicated in cellular drug resistance [7], which is an especially disadvantageous phenotype when tumor cells are capable of survival [103]. In particular, members of the MDR and MRP subfamilies have been linked to simultaneous resistance to multiple cytotoxic drugs in cancer cells. MDR1 confers resistance to a variety of hydrophobic, amphipathic natural product drugs [104] whereas members of the MRP-subfamily are associated with resistance to anionic and neutral drugs frequently conjugated to acidic ligands [23]. Although several mechanisms can contribute to MDR, altered drug accumulation appears to be common both in cell culture and in model organisms [105]. The initial discovery linking membrane transporters with drug resistance came from an observation that MDR1 decreased the accumulation and toxic effects of various and structurally unrelated anti-neoplastic drugs in CHO cells [106, 107]. Although the crystal structure of a human ABC transporter has yet to be resolved, the insights into putative structure and function of ABC transporters has been deduced from similarity with E. coli homologs, MsbA and BtuCD [108, 109]. The function of MDR1 in drug efflux is generally ATP-dependent, similar to homologous bacterial ABC transporters. However, the mechanism(s) of ATP hydrolysis-coupled substrate transport remains theoretical [110].

Extending the drug-resistance paradigm to the A subfamily, results from Laing et al. and subsequent studies showed that an ovarian carcinoma cell line (SKEM) with acquired resistance to the estradiol-based agent, estramustine (EM), has a gene amplification at 9q34 and contains an ABCA2 amplicon [101]. EM is a synthetic conjugate of nitrogen mustard and estradiol with an anti-mitotic activity (Fig. 3). A homogenously staining region, typical for gene amplification, was found in chromosome 9q34, and in situ hybridization with a specific probe indicated a ~6 fold amplification of the ABCA2 gene. The approximately 5-fold increase in gene expression in SKEM cells was accompanied by an increased rate of dansylated EM efflux and, hence, drug resistance. Cells were sensitized to EM upon treatment with antisense ABCA2 RNA [101]. Similarly, ABCA2 overexpressing HEK293 cells (HEK293-ABCA2) were also shown to be EM-resistant [15]. Somewhat lower levels of resistance (~3 fold) were observed for the same cells upon exposure to a structurally similar compound, estradiol. Supporting the observation that ABCA2 contributes to EM and estradiol resistance was that cells transfected with a putative dominant-negative mutant of ABCA2 have virtually no differences in toxicity compared to mock-transfected cells [16]. This study also showed that HEK293-ABCA2 cells were not resistant to agents that are structurally dissimilar to EM (melphalan, mitoxantrone, cisplatinum, taxol, and vinblastine) with the exception of a slight doxorubicin resistance. Further studies showed that HEK293-ABCA2 cells are also resistant to a free radical initiator, 2,2′-Azobis-(2-amidinopropane) (AAPH) [79]. Although AAPH is unrelated to other sterol-related substrates (Fig. 3), free radical or ROS induced damage may damage sterols, lipids and lipoproteins where cell survival may be facilitated by sequestration into the endolysosomal compartment. Even though ABCA2 overexpression did not confer mitoxantrone resistance in HEK293 cells, this transporter was shown to be up-regulated in a mitoxantrone-resistant small cell lung cancer cell line, GLC4-MITO [100]. The same cell line was ~2 fold more resistant to estramustine compared to parental GLC4 cells. Exposure of GLC4-MITO cells to both estramustine and mitoxantrone increased cellular accumulation of the latter, indicating an ability of estramustine to block efflux of mitoxantrone. Taken together, these results indicate that molecules with steroid-like structures are putative substrates for transport by ABCA2 and may cause induced expression. It is not known, however, whether such compounds interact directly with ABCA2 for transport across intracellular membranes, or if they serve a signaling molecule to initiate some form of transport cascade. To date, there is no clinical correlate for ABCA2 expression and cancer. More investigation into the in vivo functional role of the ABCA2 transporter is required to justify its use in the clinic for anti-cancer therapeutic strategies.

PHARMACOLOGICAL MODULATION OF ABC TRANSPORTERS

Given the roles of ABC transporters in cholesterol homeostasis, they represent potentially attractive targets for pharmacological intervention as reviewed in detail by Schmitz and Langmann [111]. Increased expression of ABCA1 has been shown to be anti-atherogenic [28, 112]. Although no agents have been shown to specifically target either ABCA1 or ABCA2, a variety of statins, or cholesterol lowering drugs, do influence ABCA1 mRNA and protein expression and impact HDL and apolipoprotein homeostasis [113]. For example, statins and fibrates are known to have the variety of anti-atherogenic effects. Exposing macrophages in vitro to any of four statins (fluvastatin, atorvastatin, simvastatin, or lovastatin) lowered levels of ABCA1 mRNA in macrophage cell lines [29]. Fibrates lower plasma triglyceride and increase HDL. Treatment of macrophage cells and fibroblasts with fenofibric acid led to enhanced transcription of ABCA1, elevated ABCA1 protein and increased apolipoprotein A-I-mediated cellular lipid release in a dose-dependent manner [114]. To date, the effects of statins on the expression and function of ABCA2 has not been established. However, due to the role of this protein in sterol transport, one might predict a similar response to statin treatment as with ABCA1. The mounting evidence for the utility of ABCA1, and other related transporters, as an antiatherogenic drug target is promising; however, additional pre-clinical studies are needed to warrant the pharmacological modulation of ABCA2 in patients.

CONCLUSIONS

ABC transporters have been shown to function in the cellular efflux of endogenous or xenobiotic substrates, for cellular and tissue homeostasis as well as adaptive mechanisms for drug resistance. So far, the dysfunction of several of these proteins has been linked to a number of clinical pathologies, with many other members still having unknown or putative disease associations, including ABCA2.

Several factors serve to limit progress in elucidating protein function for membrane-bound ABC transporters. These include structural biology studies that use traditional crystallization methods. Determination of protein-protein interactions of full-length, native proteins is hampered by their multiple domain structures and high molecular weight. Also, because of possible functional redundancy the high degree of homology among ABC transporters makes loss-of function studies difficult to interpret.

Thus far, functional studies of the ABCA2 transporter have implicated a role in transport/resistance to estramustine, estradiol (two structurally similar molecules), a free radical initiator, AAPH, and mitoxantrone (both structurally dissimilar). In addition, ABCA2 is involved in the trafficking of LDL-derived cholesterol, from the cytosol to the endolysosomal compartment. The high expression of ABCA2 in estramustine-resistant cancer cell lines and the elevated levels in neuronal and reproductive tissues may indicate a common role for this transporter in the trafficking of sterols and sterol-related compounds. However, ABCA2 expression is also high in a variety of cancer cell lines derived from non-CNS tissues (Table 2), in human vestibular schwannomas [57] and in peripheral blood monocytes and macrophages [18].

Although the structural and functional characterization of the ABCA2 transporter is in its infancy, there are several promising indications for future studies. The consequence of deregulated trafficking of cholesterol and sterol related compounds at the cell and organism level, impacts the risk for AD and carcinogenesis. Links with reactive oxygen species (ROS) and elevated LDL cholesterol [115–118] make the fact that ABCA2 is abundantly expressed in macrophages [18], more pertinent to these pathologies. These connections and the identification of other cholesterol-responsive transporters from the same family (ABCA1 and ABCA7) may provide the platform for small molecule screening strategies for these novel targets. Impending studies could provide a wealth of information for the possibility of intercession in transport function as a conduit to pharmacological intervention in these widespread diseases.

NOTE ADDED IN PROOFS

ABCA2 and ABCA3 were recently shown to be up-regulated in clinical samples of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) and in human T-ALL cell lines upon treatment with methotrexate, vinblastine or doxorubicin (Efferth, T., Gillet, J.P., Sauerbrey, A., Zintl, F., Bertholet, V., de Longueville, F., Remacle, J. and Steinbach, D. (2006) Mol. Cancer Ther. 5(8), 1986–1994).

ABBREVIATIONS

- AAPH

2,2’-azobis-(2-amidinopropane)

- Aβ

β–amyloid peptide

- ABC

ATP binding cassette

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- ADGE

Amplified differential gene expression

- ALD

X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy

- APP

β-amyloid precursor protein

- CF

Cystic fibrosis

- CNS

Central nervous system

- EGR-1

Early growth response-1

- EM

Estramustine

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- FHC

Familial Hypercholesterolemia

- HDL

High density lipoproteins

- HMGCoA S

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA synthase

- LA

Linoleic acid

- LAMP

Lysosome-associated membrane proteins

- LDL

Low-density lipoprotein

- LDLR

LDL receptor

- LXR

Liver X receptor

- MDR1/Pgp1

Multidrug transporter/P-glycoprotein

- MRP1

Multidrug resistance associated protein

- NPC1

Niemann-Pick type C1

- PGE2

Prostaglandin E2

- PUFAs

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SNP

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms

- SREBP2

Sterol-response element binding protein-2

- VLDL

Very low-density lipoproteins

REFERENCES

- [1].Higgins c.f. (1992) Annu. Rev. cell Biol, 8, 67–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Iida A; Saito S; Sekine A; Mishima C; Kitamura Y; Kondo K; Harigae S; Osawa S; Nakamura Y (2002) J. Hum. Genet, 47(6), 285–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Holland IB; Blight MA (1999) J. Mol. Biol, 293(2), 381–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Croop JM (1998) Methods Enzymol, 292, 101–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tusnady GE; Bakos E; Varadi A; Sarkadi B (1997) FEBS Lett, 402(1), 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sharom FJ; Liu R; Romsicki Y; Lu P (1999) Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1461(2), 327–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Klein I; Sarkadi B; Varadi A (1999) Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1461(2), 237–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lockhart AC; Tirona RG; Kim RB (2003)Mol. Cancer Ther, 2(7), 685–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sparreboom A; Danesi R; Ando Y; Chan J; Figg WD (2003) Drug Resist. Updat, 6(2), 71–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Broccardo C; Luciani M; Chimini G (1999) Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1461(2), 395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Efferth T (2003) Ageing Res. Rev, 2(1), 11–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dean M (2005) Methods Enzymol, 400(409–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Luciani MF; Denizot F; Savary S; Mattei MG; Chimini G (1994) Genomics, 21(1), 150–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kikuno R; Nagase T; Ishikawa K; Hirosawa M; Miyajima N; Tanaka A; Kotani H; Nomura N; Ohara O (1999) DNA Res, 6(3), 197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Vulevic B; Chen Z; Boyd JT; Davis W Jr.; Walsh ES; Belinsky MG; Tew KD (2001) Cancer Res, 61(8), 3339–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ile KE; Davis W Jr.; Boyd JT; Soulika AM; Tew KD (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1678(1), 22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhao LX; Zhou CJ; Tanaka A; Nakata M; Hirabayashi T; Amachi T; Shioda S; Ueda K; Inagaki N (2000) Biochem. J, 350(Pt 3), 865–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kaminski WE; Piehler A; Pullmann K; Porsch-Ozcurumez M; Duong C; Bared GM; Buchler C; Schmitz G (2001) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun, 281(1), 249–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Davis W Jr.; Chen ZJ; Ile KE; Tew KD (2003) Nucleic Acids Res, 31(3), 1097–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Schmitz G; Kaminski WE (2002) Cell Mol. Life Sci, 59(8), 1285–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Langmann T; Porsch-Ozcurumez M; Heimerl S; Probst M; Moehle C; Taher M; Borsukova H; Kielar D; Kaminski WE; Dittrich-Wengenroth E; Schmitz G (2002) J. Biol. Chem, 277(17), 14443–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Fitzgerald ML; Okuhira KI; Short GF 3rd; Manning JJ; Bell SA; Freeman MW (2004) J. Biol. Chem, 279(46), 48477–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Borst P; Evers R; Kool M; Wijnholds J (2000) J. Natl. Cancer Inst, 92(16), 1295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Brown MS; Goldstein JL (1986) Science, 232(4746), 34–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Davis W Jr.; Boyd JT; Ile KE; Tew KD (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1683(1–3), 89–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Smith JR; Osborne TF; Goldstein JL; Brown MS (1990) J. Biol. Chem, 265(4), 2306–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].McNeish J; Aiello RJ; Guyot D; Turi T; Gabel C; Aldinger C; Hoppe KL; Roach ML; Royer LJ; de Wet J; Broccardo C; Chimini G; Francone OL (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 97(8), 4245–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Singaraja RR; Bocher V; James ER; Clee SM; Zhang LH Leavitt BR; Tan B; Brooks-Wilson A; Kwok A; Bissada N Yang YZ; Liu G; Tafuri SR; Fievet C; Wellington CL Staels B; Hayden MR (2001) J. Biol. Chem, 276(36), 33969–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sone H; Shimano H; Shu M; Nakakuki M; Takahashi A Sakai M; Sakamoto Y; Yokoo T; Matsuzaka K; Okazaki H Nakagawa Y; Iida KT; Suzuki H; Toyoshima H; Horiuchi S Yamada N (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun, 316(3), 790–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Uehara Y; Engel T; Li Z; Goepfert C; Rust S; Zhou X; Langer C; Schachtrup C; Wiekowski J; Lorkowski S; Ass-mann G; von Eckardstein A (2002) Diabetes, 51(10), 2922–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Radu RA; Mata NL; Bagla A; Travis GH (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 101(16), 5928–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kubo Y; Sekiya S; Ohigashi M; Takenaka C; Tamura K; Nada S; Nishi T; Yamamoto A; Yamaguchi A (2005) Mol. Cell Biol, 25(10), 4138–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kim WS; Fitzgerald ML; Kang K; Okuhira K; Bell SA; Manning JJ; Koehn SL; Lu N; Moore KJ; Freeman MW (2005) J. Biol. Chem, 280(5), 3989–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Schinkel AH (1997) Semin. Cancer Biol, 8(3), 161–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Rao VV; Dahlheimer JL; Bardgett ME; Snyder AZ; Finch RA; Sartorelli AC; Piwnica-Worms D (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 96(7), 3900–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Woodahl EL; Ho RJ (2004) Curr. DrugMetab, 5(1), 11–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].de la Salle H; Zimmer J; Fricker D; Angenieux C; Cazenave JP; Okubo M; Maeda H; Plebani A; Tongio MM; Dormoy A; Hanau D (1999) J. Clin. Invest, 103(5), R9–R13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zaman GJ; Flens MJ; van Leusden MR; de Haas M; Mulder HS; Lankelma J; Pinedo HM; Scheper RJ; Baas F; Brox-terman HJ; Borst P (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 91(19), 8822–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zaman GJ; Lankelma J; van Tellingen O; Beijnen J; Dekker H; Paulusma C; Oude Elferink RP; Baas F; Borst P (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 92(17), 7690–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kunzelmann K (1999) Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol, 137, 1–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Choi JY; Lee MG; Ko S; Muallem S (2001) JOP, 2(4 Suppl), 243–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Smith KD; Kemp S; Braiterman LT; Lu JF; Wei HM; Geraghty M; Stetten G; Bergin JS; Pevsner J; Watkins PA (1999) Neurochem. Res, 24(4), 521–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Dodd A; Rowland SA; Hawkes SL; Kennedy MA; Love DR (1997) Hum. Mutat, 9(6), 500–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kerr ID (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun, 315(1), 166–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lorkowski S; Kratz M; Wenner C; Schmidt R; Weitkamp B; Fobker M; Reinhardt J; Rauterberg J; Galinski EA; Cullen P (2001) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun, 283(4), 821–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Bodzioch M; Orso E; Klucken J; Langmann T; Bottcher A; Diederich W; Drobnik W; Barlage S; Buchler C; Porsch-Ozcurumez M; Kaminski WE; Hahmann HW; Oette K; Rothe G; Aslanidis C; Lackner KJ; Schmitz G (1999) Nat. Genet, 22(4), 347–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Marcil M; Brooks-Wilson A; Clee SM; Roomp K; Zhang LH; Yu L; Collins JA; van Dam M; Molhuizen HO; Loubster O; Ouellette BF; Sensen CW; Fichter K; Mott S; Denis M; Boucher B; Pimstone S; Genest J Jr.; Kastelein JJ; Hayden MR (1999) Lancet, 354(9187), 1341–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Brooks-Wilson A; Marcil M; Clee SM; Zhang LH; Roomp K; van Dam M; Yu L; Brewer C; Collins JA; Molhuizen HO; Loubser O; Ouelette BF; Fichter K; Ashbourne-Excoffon KJ; Sensen CW; Scherer S; Mott S; Denis M; Martindale D; Frohlich J; Morgan K; Koop B; Pimstone S; Kastelein JJ; Hayden MR (1999) Nat. Genet, 22(4), 336–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Rust S; Rosier M; Funke H; Real J; Amoura Z; Piette JC; Deleuze JF; Brewer HB; Duverger N; Denefle P; Assmann G (1999) Nat. Genet, 22(4), 352–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Orso E; Broccardo C; Kaminski WE; Bottcher A; Liebisch G; Drobnik W; Gotz A; Chambenoit O; Diederich W; Lang-mann T; Spruss T; Luciani MF; Rothe G; Lackner KJ; Chimini G; Schmitz G (2000) Nat. Genet, 24(2), 192–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Yamano G; Funahashi H; Kawanami O; Zhao LX; Ban N; Uchida Y; Morohoshi T; Ogawa J; Shioda S; Inagaki N (2001) FEBS Lett, 508(2), 221–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Nogee LM (2004) Biol. Neonate, 85(4), 314–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Wulf GG; Modlich S; Inagaki N; Reinhardt D; Schroers R; Griesinger F; Trumper L (2004) Haematologica, 89(11), 1395–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Tanaka AR; Ikeda Y; Abe-Dohmae S; Arakawa R; Sadanami K; Kidera A; Nakagawa S; Nagase T; Aoki R; Kioka N; Amachi T; Yokoyama S; Ueda K (2001) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun, 283(5), 1019–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Wang N; Lan D; Gerbod-Giannone M; Linsel-Nitschke P; Jehle AW; Chen W; Martinez LO; Tall AR (2003) J. Biol. Chem, 278(44), 42906–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kielar D; Kaminski WE; Liebisch G; Piehler A; Wenzel JJ; Mohle C; Heimerl S; Langmann T; Friedrich SO; Bottcher A; Barlage S; Drobnik W; Schmitz G (2003) J. Invest. Dermatol, 121(3), 465–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Wang Y; Yamada K; Tanaka Y; Ishikawa K; Inagaki N (2005) J. Neurol. Sci, 232(1–2), 59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kim WS; Guillemin GJ; Glaros EN; Lim CK; Garner B (2006) Neuroreport, 17(9), 891–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Zhou CJ; Inagaki N; Pleasure SJ; Zhao LX; Kikuyama S; Shioda S (2002) J. Comp. Neurol, 451(4), 334–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Puglielli L; Tanzi RE; Kovacs DM (2003) Nat. Neurosci, 6(4), 345–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Tanzi RE; Bertram L (2001) Neuron, 32(2), 181–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Price DL; Tanzi RE; Borchelt DR; Sisodia SS (1998) Annu. Rev. Genet, 32(461–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Cao X; Sudhof TC (2001) Science, 293(5527), 115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kimberly WT; Zheng JB; Guenette SY; Selkoe DJ (2001) J. Biol. Chem, 276(43), 40288–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Thinakaran G (1999) J. Clin. Invest, 104(10), 1321–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Bertram L; Tanzi RE (2004) Hum. Mol. Genet, 13(Spec No 1), R135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Roses AD; Saunders AM (1994) Curr. Opin. Biotechnol, 5(6), 663–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Papassotiropoulos A; Streffer JR; Tsolaki M; Schmid S; Thal D; Nicosia F; Iakovidou V; Maddalena A; Lutjohann D; Ghe-bremedhin E; Hegi T; Pasch T; Traxler M; Bruhl A; Benussi L; Binetti G; Braak H; Nitsch RM; Hock C (2003) Arch. Neurol, 60(1), 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Casserly I; Topol E (2004) Lancet, 363(9415), 1139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Hartmann T (2001) Trends Neurosci, 24(11 Suppl), S45–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Simons M; Keller P; Dichgans J; Schulz JB (2001) Neurology, 57(6), 1089–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Kivipelto M; Helkala EL; Laakso MP; Hanninen T; Hallikainen M; Alhainen K; Soininen H; Tuomilehto J; Nissinen A (2001) BMJ, 322(7300), 1447–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Wolozin B; Brown J 3rd; Theisler C; Silberman S (2004) CNS Drug Rev, 10(2), 127–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Jick H; Zornberg GL; Jick SS; Seshadri S; Drachman DA (2000) Lancet, 356(9242), 1627–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Fassbender K; Masters C; BeyreuTher. K(2001) Naturwissenschaften, 88(6), 261–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Refolo LM; Pappolla MA; LaFrancois J; Malester B; Schmidt SD; Thomas-Bryant T; Tint GS; Wang R; Mercken M; Petanceska SS; Duff KE (2001) Neurobiol. Dis, 8(5), 890–09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Wollmer MA; Streffer JR; Lutjohann D; Tsolaki M; Iakovidou V; Hegi T; Pasch T; Jung HH; Bergmann K; Nitsch RM; Hock C; Papassotiropoulos A (2003) Neurobiol. Aging, 24(3), 421–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Katzov H; Chalmers K; Palmgren J; Andreasen N; Johansson B; Cairns NJ; Gatz M; Wilcock GK; Love S; Pedersen NL; Brookes AJ; Blennow K; Kehoe PG; Prince JA (2004) Hum. Mutat, 23(4), 358–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Chen ZJ; Vulevic B; Ile KE; Soulika A; Davis W Jr.; Reiner PB; Connop BP; Nathwani P; Trojanowski JQ; Tew KD (2004) FASEB J, 18(10), 1129–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Mace S; Cousin E; Ricard S; Genin E; Spanakis E; Lafargue-Soubigou C; Genin B; Fournel R; Roche S; Haussy G; Massey F; Soubigou S; Brefort G; Benoit P; Brice A; Campion D; Hollis M; Pradier L; Benavides J; Deleuze JF (2005) Neurobiol. Dis, 18(1), 119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Wollmer MA; Kapaki E; Hersberger M; Muntwyler J; Brunner F; Tsolaki M; Akatsu H; Kosaka K; Michikawa M; Molyva D; Paraskevas GP; Lutjohann D; Eckardstein A; Hock C; Nitsch RM; Papassotiropoulos A (2006) Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet, 141(5), 534–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Broccardo C; Nieoullon V; Amin R; Masmejean F; Carta S; Tassi S; Pophillat M; Rubartelli A; PierRes., M.; Rougon, G.; Nieoullon, A.; Chazal, G.; Chimini, G. (2006) J. Neurochem, 97(2), 345–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Pasternak SH; Bagshaw RD; Guiral M; Zhang S; Ackerley CA; Pak BJ; Callahan JW; Mahuran DJ (2003) J. Biol. Chem, 278(29), 26687–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Nixon RA; Cataldo AM; Mathews PM (2000) Neurochem.Res, 25(9–10), 1161–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Freeman MR; Solomon KR (2004) J.Cell Biochem, 91(1), 54–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Molony T (2003) J. Dent. Hyg, 77(4), 214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Michaud DS; Giovannucci E; Willett WC; Colditz GA; Fuchs CS (2003) Am. J. Epidemiol, 157(12), 1115–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Siemianowicz K; Gminski J; Stajszczyk M; Wojakowski W; Goss M; Machalski M; Telega A; Brulinski K; Magiera-Molendowska H (2000) Int. J. Mol. Med, 6(3), 307–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Hughes-Fulford M; Chen Y; Tjandrawinata RR (2001) Carcinogenesis, 22(5), 701–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Chen Y; Hughes-Fulford M (2001) Int. J. Cancer, 91(1), 41–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].TatiDis L; Gruber A; Vitols S (1997) J. Lipid. Res, 38(12), 2436–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Lum DF; McQuaid KR; Gilbertson VL; Hughes-Fulford M (1999) Int. J. Cancer, 83(2), 162–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Habenicht AJ; Salbach P; Janssen-Timmen U (1992) Eicosanoids, 5(Suppl), S29–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Needleman P; Turk J; Jakschik BA; Morrison AR; Lefkowith JB (1986) Annu. Rev. Biochem, 55(69–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Chen Y; Hughes-Fulford M (2000) Br. J. Cancer, 82(12), 2000–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Gylling H; Pyrhonen S; Mantyla E; Maenpaa H; Kangas L; Miettinen TA (1995) J. Clin. Oncol, 13(12), 2900–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Mastroianni A; Bellati C; Facchetti G; Oldani S; Franzini C; Berrino F (2000) Clin. BioChem, 33(6), 513–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Kim J; Adam RM; Solomon KR; Freeman MR (2004) Endocrinology, 145(2), 613–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Brower V (2003) J. Natl. Cancer Inst, 95(12), 844–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Boonstra R; Timmer-Bosscha H; van Echten-Arends J; van der Kolk DM; van den Berg A; de Jong B; Tew KD; Poppema S; de Vries EG (2004) Br. J. Cancer, 90(12), 2411–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Laing NM; Belinsky MG; Kruh GD; Bell DW; Boyd JT; Barone L; Testa JR; Tew KD (1998) Cancer Res, 58(7), 1332–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Fehrenbacher N; Jaattela M (2005) Cancer Res, 65(8), 2993–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Dean M; Fojo T; Bates S (2005) Nat. Rev. Cancer, 5(4), 27584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Ambudkar SV; Dey S; Hrycyna CA; Ramachandra M; Pas-tan I; Gottesman MM (1999) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol, 39, 361–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Ambudkar SV; Kimchi-Sarfaty C; Sauna ZE; Gottesman MM (2003) Oncogene, 22(47), 7468–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Juliano RL; Ling V (1976) Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 455(1), 152–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Riordan JR; Ling V (1979) J. Biol. Chem, 254(24), 12701–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Chang G; Roth CB (2001) Science, 293(5536), 1793–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Locher KP; Lee AT; Rees DC (2002) Science, 296(5570), 1091–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Liao JL; Beratan DN (2004) Biophys. J, 87(2), 1369–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Schmitz G; Langmann T (2005) Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs, 6(9), 907–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Singaraja RR; Fievet C; Castro G; James ER; Hennuyer N; Clee SM; Bissada N; Choy JC; Fruchart JC; McManus BM; Staels B; Hayden MR (2002) J. Clin. Invest, 110(1), 35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Oram JF; Heinecke JW (2005) Physiol. Rev, 85(4), 1343–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Arakawa R; Tamehiro N; Nishimaki-Mogami T; Ueda K; Yokoyama S (2005) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol, 25(6), 1193–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Witztum JL (1994) Lancet, 344(8925), 793–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Griendling KK; FitzGerald GA (2003) Circulation, 108(16), 1912–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Barnham KJ; Masters CL; Bush AI (2004) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov, 3(3), 205–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Ames BN; Gold LS; Willett WC (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 92(12), 5258–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Corpet F (1988) Nucl. Acids Res, 16(22), 10881–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]