Abstract

Objective: To quantitatively and qualitatively describe some of the challenges faced by the Philippines' health insurance programme, PhilHealth, in the era of Universal Health Coverage.

Methods: A descriptive study using a mixture of quantitative and qualitative methods. Quantitative data were collected from various sources and semi-structured interviews were conducted among staff of relevant organisations. We focused particularly on the enrolment process among eligible individuals and the system of reimbursement in five local government units (LGUs).

Results: The proportion of individuals enrolled as ‘poor’ exceeded the number officially assessed as being poor by 1–11 times in almost all of the LGUs evaluated. Interviews revealed ‘politically indigent’ individuals, i.e., the enrolment of non-poor individuals as poor. Several health centres were not receiving reimbursements from PhilHealth, likely due to structural and political deficiencies in the process of claiming and receiving reimbursements.

Conclusion: The composition of the sponsored and indigent membership groups requires closer examination to determine whether people who are truly marginalised are left without health coverage. PhilHealth also needs to improve its reaccreditation and reimbursement systems and processes so that health centres can appreciate the benefits of becoming PhilHealth-accredited service providers.

Keywords: indigent, reimbursement, proxy means testing

Abstract

Objectif : Décrire quantitativement et qualitativement certains des défis auxquels est confronté le programme d'assurance sociale santé des Philippines à l'ère de la couverture santé universelle.

Méthodes : Etude descriptive recourant à un mélange de méthodes quantitatives et qualitatives. Les données quantitatives ont été recueillies grâce à des ressources variées et à des entretiens semi-structurés réalisés au sein du personnel des organisations concernées. Nous nous sommes particulièrement concentrés sur la procédure d'enrôlement des patients éligibles et sur le système de remboursement dans cinq unités gouvernementales locales (LGU) des Philippines.

Résultats : Le ratio d'enrôlement de ceux identifiés comme « pauvres » a été multiplié par 1 à 11 dans presque toutes les LGU interviewées. L'analyse des entretiens a révélé une indigence « politique », aboutissant à l'enrôlement de non pauvres comme pauvres. Plusieurs centres de santé n'ont pas reçu de remboursement de PhilHealth, très probablement en raison de déficiences structurelles et politiques du processus de demande et de réception des remboursements.

Conclusion : Un examen plus attentif du statut des personnes enrôlées pour être subventionnés et de l'affiliation en tant qu'indigent devrait être réalisé afin de déterminer si des personnes réellement marginalisées restent sans couverture. PhilHealth doit également améliorer les systèmes et processus de réaccréditation et de remboursement pour que les centres de santé apprécient le bénéfice de devenir prestataires de service accrédités de PhilHealth.

Abstract

Objetivo: Describir de manera cuantitativa y cualitativa algunas de las dificultades que afronta el programa social de seguro de salud de Filipinas en la era de la cobertura de salud para todos.

Métodos: Se realizó un estudio descriptivo con una combinación de métodos cuantitativos y cualitativos. Los datos cuantitativos se recogieron de varias fuentes y se llevaron a cabo entrevistas semiestructuradas a miembros del personal de organizaciones pertinentes. Se prestó una atención especial al procedimiento de inscripción de las personas aptas y al sistema de reembolso en cinco unidades gubernamentales locales (LGU) de Filipinas.

Resultados: La proporción de inscripciones de personas calificadas como ‘pobres’ fue de 1 a 11 veces superior en todas las LGU encuestadas. El análisis de las entrevistas reveló que la definición ‘política’ de indigente llevó a la inscripción como pobres de personas no lo eran. Varios centros de salud no recibían reembolsos de PhilHealth, muy probablemente debido a deficiencias estructurales y políticas en el proceso solicitud y de recepción de los reembolsos.

Conclusión: Es necesario practicar una investigación cuidadosa de la composición de los miembros inscritos en la categoría subvencionada o la categoría indigente, con el objeto de determinar si las personas realmente marginalizadas quedan sin cobertura. Asimismo, PhilHealth debe mejorar los sistemas y los procedimientos de reacreditación y de reembolso de los centros de salud, de manera que se puedan apreciar los beneficios que otorga a un prestador de atención de salud la acreditación por parte de este organismo.

The Philippines has chosen to rely on a social health insurance system, Philippine Health Insurance (PhilHealth), as the route to achieving Universal Health Coverage. Established in 1995 as a single national health insurance programme,1 PhilHealth is a tax-exempt, government-owned, government-controlled corporation attached to the Department of Health (DOH), funded primarily through premiums from members and general taxation. PhilHealth holds sole responsibility for collecting premiums, accrediting service providers, establishing benefit packages, processing claims and reimbursing health care service providers for their services.

Although the level of financial protection provided remains limited,2 PhilHealth has claimed success in terms of population coverage: estimated at 83% in 2004, coverage increased to 86% in 2010, and to almost ‘universal’ coverage, at 92%, in 2016.3 It has also been claimed that PhilHealth has successfully increased access to primary health care services through various packages and ensured quality of services through its accreditation system.

The success of PhilHealth has been applauded both locally and internationally, with studies such as that by Obermann et al. concluding that ‘social health insurance in the Philippines in 2006 has been a success story so far and provides lessons for countries in similar situations’.4 Nevertheless, a study by the World Health Organization (WHO) has reported unreliable population coverage data and substantial transactional requirements being demanded from its members to make claims.2

The present study thus aimed to conduct a detailed descriptive evaluation of the PhilHealth programme and identify possible challenges, focusing on the enrolment process for economically disadvantaged individuals and the process of reimbursement for health care providers.

DESIGN AND METHODS

This descriptive study examined the implementation of the PhilHealth programme in five local government units (LGUs): three in Metro Manila, one in Region 4A and one in Region 3 (both are located in Luzon), focusing specifically on the enrolment process of economically disadvantaged individuals, and the process of reimbursement for health care providers.

Definitions

Enrolment process for economically disadvantaged individuals

PhilHealth beneficiaries are grouped into six main categories: 1) members of the formal economy; 2) members of the informal economy; 3) ‘indigent members’, who are considered as not having any means of income or sufficient income; 4) ‘sponsored members’, who are primarily from the lower income segment of the informal economy; 5) ‘life-time members’, who are retirees (aged ≥60 years), and have already paid at least 120 monthly premium contributions; and 6) ‘senior citizens’, who are aged ≥60 years and are not currently covered by any PhilHealth membership. The premium for indigent and senior citizen membership is subsidised by the national government, and for sponsored membership by their respective LGU and/or legislative sponsors, or private entities.5

For the purposes of the study, we focused on indigent and sponsored members as representing economically disadvantaged individuals, and reviewed the enrolment process using data obtained from PhilHealth and the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), which is responsible for identifying poor and near-poor individuals eligible for the two membership categories. The enrolment ratio was defined as the ratio of the number of enrolled poor to the number of assessed poor.

Accreditation and reimbursement processes for health care providers

Several comprehensive packages of health services are available for PhilHealth beneficiaries.2–4 These services are provided through both private and public providers certified by the DOH and accredited by PhilHealth. The health care service providers are required to meet certain DOH criteria and to be certified per benefit package to be accredited by PhilHealth; they are requested to renew their reaccreditation annually. Upon provision of services, the providers file a claim for each patient to PhilHealth for reimbursement. The reimbursement may then be used to cover operational expenses, facility improvement and rewards for health care workers, including community volunteers, in accordance with PhilHealth guidelines.6,7

We focused on two packages: the tuberculosis (TB) DOTS package, which includes medicines and diagnostic examinations for drug-susceptible TB and is available for all membership types, and the primary care benefit (PCB) package, which includes primary preventive services, diagnostic examinations and provision of medicines for common diseases, and is available for indigent, sponsored and, to some extent, formal members.6,7

Data sources and analysis

Quantitative data on the PhilHealth enrolment and reimbursement processes in the five sampled LGUs in urban and rural areas were obtained from published and unpublished academic papers, newspaper articles and official records related to PhilHealth insurance coverage, schemes and its performance. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with members of relevant organisations, including the City/Municipality Health Offices, local health centres, LGUs, the DSWD and PhilHealth. An interview guide was established with the aim of identifying possible reasons for answers given to the two questions from quantitative data (see Appendix). Interviews were conducted by AQ, MR and LK between February and October 2017. All interviews took place after obtaining informed consent from the participants, recorded using a digital voice recorder, and then transcribed verbatim.

The data from the semi-structured interviews were analysed by performing qualitative content analysis, which involved familiarisation of text through multiple readings of transcripts. A thematic framework was then designed through an iterative process, and segments describing the enrolment process, reaccreditation and problems in obtaining payment of reimbursement funds from Philhealth were identified for further analysis. Themes and emerging key points were developed into a thematic framework table where each main point was divided into subpoints and coded into transcripts by AQ. Coded transcripts were reviewed by LK, then by AO, to discuss discrepancies in coding.

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the DOH Jose R Reyes Memorial Medical Center Metro Manila, the Philippines (IRB no 2016-100), and the Institutional Review Board of the Research Institute of Tuberculosis Tokyo, Japan (RIT/IRB 28-15).

RESULTS

Enrolment process among economically disadvantaged individuals

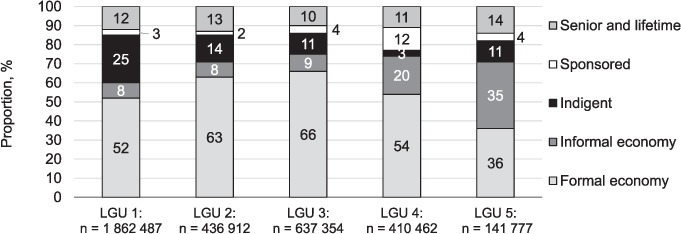

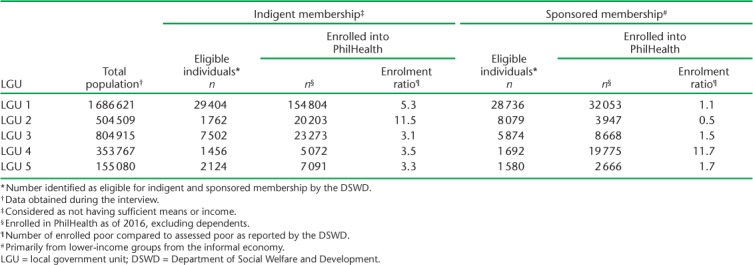

The estimated total population of the five LGUs targeted by the study was 3 504 892 in 2016. According to interviewees from Phil-Health, about 99.5% (n = 3 489 172) of these were PhilHealth members. PhilHealth membership in each LGU is shown by category in the Figure. The proportions of indigent and sponsored members varied significantly, with the proportion of indigent members ranging from 3% in LGU 4 to 25% in LGU 1. The proportion of sponsored members was similar in four LGUs, ranging from 2% to 4%, while in one LGU (LGU 4) it was 12%. The enrolment ratios for indigent and sponsored membership were calculated for each LGU (Table 1). The enrolment rate exceeded the assessment rate by 3.1–11.5 times for indigent membership in all LGUs, and for sponsored membership in all but one LGU. In other words, the number of individuals enrolled as indigent and sponsored members for PhilHealth was higher than those identified as eligible by the DSWD.

FIGURE.

Distribution of PhilHealth membership categories per LGU as of December 2016. Source: personal information obtained during interviews with PhilHealth staff. LGU = local government unit.

TABLE 1.

Number of eligible * and of actual indigent and sponsored members enrolled into PhilHealth as of 2016 in five LGUs, the Philippines

Several potential reasons for the excessive enrolment in indigent and sponsored membership were identified from interviews. Although the DSWD identifies ‘poor’ and the ‘near-poor’ individuals based on proxy means testing, where information on household or individual characteristics correlated with welfare levels is used in a formal algorithm to proxy household income,8 the LGUs can apparently also issue their own ‘certificate of indigency’ to residents who claim poverty. The local DSWD then uses the certificate to determine eligibility for sponsored membership of Phil-Health. There is, however, no standardised procedure to determine who is and who is not eligible for the certificate of indigency, nor to validate these claims. These were common themes, i.e., several interviewees mentioned inappropriate issuance of the certificate:

…it is the LGU and local DSWD which identifies the poor but we cannot prevent the politicians from enrolling other beneficiaries, they have their own fund so it depends on them. (Staff, City Health Office)

(Asked whether the interviewee has ever seen a well-off patient enrolled as a sponsored member) …Yes, because in reality the key persons here who will select the poor or beneficiaries of PhilHealth are the head of the smallest political unit. (Nurse, Health Centre)

On the other hand, although not the primary focus of our study, several interviewees mentioned difficulties in encouraging low-income earners in the informal sector to enrol themselves in PhilHealth:

(Asked why patients in the informal sector were reluctant to enrol in PhilHealth) …maybe because of poverty…because enrolling in PhilHealth is not their priority. Even if they have money, they will use that to buy food instead of paying for PhilHealth. (Staff, Municipal Health Office)

(Asked whether the interviewee would encourage tricycle drivers to enrol in PhilHealth) …yes, but usually they do not follow our suggestion. Tricycle drivers would think of the food on their table rather than consider long-term concerns for health. (Nurse, Health Centre)

Accreditation and reimbursement processes for health care providers

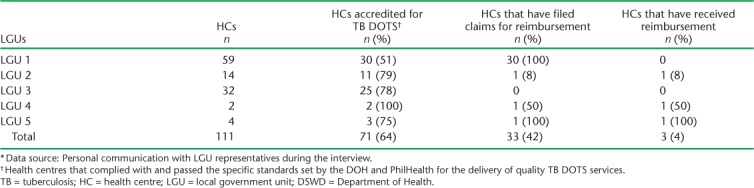

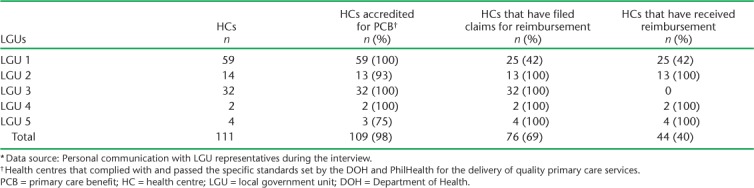

There were a total of 111 health centres in the five LGUs, of which respectively 64% (71/111) and 98% (109/111) were accredited by PhilHealth and were providing services for the TB DOTS and PCB packages as of May 2018. Some health centres were not accredited as they did not yet meet the necessary criteria, such as infection control. However, several health centres had intentionally chosen not to renew their accreditation. The status of accreditation and reimbursements is shown in Tables 2 and 3.

TABLE 2.

TB DOTS PhilHealth accreditation among HCs in the five LGUs, The Philippines, 2018 *

TABLE 3.

PCB PhilHealth accreditation among HCs in the five LGUs, The Philippines, 2018 *

Analysis of interviews revealed several reasons for choosing not to renew accreditation. One interviewee complained of a cumbersome and sometimes slow process of assessment for DOH certification (this was a typical theme):

We actually applied for DOH recertification in 2014 but no DOH representative came. I think they lack manpower because of the rationalisation plan in the government, where several employees availed of early retirement, which resulted in delays in recertification of our facilities. (Staff, Municipal Health Office)

Others chose not to renew because they saw no advantage, as they did not receive reimbursements even when they were accredited. The reimbursement is initially paid to the respective LGU. PhilHealth ‘encourages’ LGUs to establish a trust fund specifically to distribute the reimbursement. However, interviews have revealed that in fact the decision to release payment to the health centres was at the complete discretion of each of the LGUs. This has resulted in some health centres receiving reimbursement, and others in a different LGU receiving no reimbursement whatsoever.

…I found out that the reason why our health centres are not receiving reimbursement for TB DOTS package was because we do not have a local ordinance or policy to support access to the reimbursement and how it can be distributed among staff and treatment partners. (Staff, City Health Office)

…we received (the reimbursement) once in 2014 for the PCB. After that we did not receive anything. What we received was a copy of the cheque. The cheque was addressed to XXXX LGU. Since it was addressed to the XXXX LGU, (our) health centre cannot withdraw it from the bank and use it for the health facilities. (Staff, health centre)

…In 2012, the XXXX Health Department showed us the amount of money that each facility can get from the PCB, but it was so frustrating that it didn't reach us. The money is only written on that paper…. (Staff, health centre)

Unsurprisingly, only 42% (33/78) and 69% (76/110), respectively, of PhilHealth-accredited facilities for the TB DOTS and PCB packages had in fact filed claims for reimbursement in 2016. Some interviewees also commented that they were demotivated to file claims due to the tedious, complicated processes which often changed without warning, or changes were made that were simply beyond their capacity to accommodate (typical of some). One interviewee mentioned,

…we filed claims for 2014 to 2015 but these were not accepted by PhilHealth because we used the old form and (we were) recommended to use the revised form...but we were not given orientation on how to use the new form. (Staff, Municipal Health Office)

…we stopped filing claims because we were told by PhilHealth that now we should be filing claims electronically. But we don't have the programme for processing claims electronically (not installed yet). (Staff, Municipal Health Office)

DISCUSSION

Previous reports have been published on PhilHealth coverage in terms of numbers of enrolled members, but none so far on the enrolment process. Our study is the first to attempt to estimate the enrolment ratio of PhilHealth members officially identified as ‘poor’ or ‘near-poor’. However, the estimated ratio of enrolled poor (as reported by the DSWD) to assessed poor was more than 1–11 times for both indigent and sponsored membership in almost all LGUs under study. It is noteworthy that the DSWD list is based on the number of households, while PhilHealth enrolment is per family, and one household may be composed of several families. In addition, the interview analysis revealed the possible existence of ‘political’ indigents. Several studies in the past have also observed the political nature of the selection process for ‘indigents’. For example, the number of sponsored members increased drastically in 2004, when the then incumbent president ran for re-election together with other national and local politicians. Capuno et al. suggested that at the time health insurance membership was distributed by the incumbent officials to pursue re-election objectives.9

The identification of the poor by the DSWD using proxy means testing was an attempt at overcoming the issue of the ‘political’ indigent; however, studies have also highlighted similar deficiencies with this system, namely overcounting the poor.10 One study suggested that only 73% of the beneficiaries should be classified as ‘poor’—in other words, for every 100 beneficiaries, 27 are in fact not poor.11 Our study results suggest a similar tendency, implying that despite claims of ‘near’ universal coverage, the actual coverage of PhilHealth may not necessarily be equitable in nature, and that those truly in need are most likely left without health coverage, including economically disadvantaged individuals in the informal sector. Even with the use of proxy means testing, political interference might nevertheless exist, as in the case in Colombia, where Castañeda et al. reported that politics influenced programme area selection for identification of the poor, and some areas were not visited because the enumerators had their own political agenda.12 It was recommended that the inclusion of appropriate safeguards, such as community verification, would reduce errors related to this kind of influence.12,13

As regards the reimbursement process, our results indicate that, at least for some health centres, reimbursements were not being paid despite claims being filed, while other health centres have simply given up claiming for reimbursements despite provision of services. Not being reimbursed has direct consequences on the quality of the services, including ensuring continuous supplies of medications and equipment. It has been pointed out that this in turn promotes irrational use of health services, whereby patients bypass the primary health care services and directly access secondary or tertiary facilities for primary care, resulting in inefficient service delivery.2 Our study suggests that amendments to the legislation in the provision and use of reimbursements should be considered at LGU level. The computerisation of claims filing is progressing, but slowly and unevenly, as with other health information systems in the Philippines. Lessons from the implementation of Manila's Community Health Information Tracking System, a medical record system for rural health units, which is currently being piloted in several health centres, have indicated the importance of preparing and training health workers at the primary level to become familiar with electronic systems.14 The same could be done for PhilHealth, so that health centres are not discouraged from filing claims for reimbursements.

This study is not without limitations: first, the performance of PhilHealth was evaluated in a limited number of LGUs, and even among our study sites, we identified variations; our results should thus be interpreted as not presenting a general picture but more as highlighting inconsistencies that need to be addressed. Second, we focused mainly on sponsored and indigent members as representing the most economically disadvantaged due to difficulties in identifying individuals in low-income groups in the informal sector. A further study may be necessary to evaluate the performance of PhilHealth from the perspective of Universal Health Coverage. Further insights from PhilHealth, its members and other stakeholders should be sought to obtain a wider perspective of its implementation. A patient cost survey has just been concluded in the Philippines,15 and our results should be read together with the evaluation of PhilHealth's role in protecting its beneficiaries from catastrophic health spending.

CONCLUSION

A closer examination of the composition of sponsored and indigent memberships should be conducted to determine whether truly marginalised individuals are left without health coverage. PhilHealth also needs to streamline its various procedures to improve the reaccreditation and reimbursement systems and processes so that health centres may appreciate the benefits of becoming a PhilHealth accredited service provider.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all five local government units for their commitment and support. This work was financially supported by a Health, Labour and Welfare Sciences Research Grants of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Tokyo, Japan (Grant no 28040101) and by the double-barred, cross-seal donation fund of the Japan Anti-Tuberculosis Association, Tokyo, Japan.

APPENDIX

Interview guide for LGU personnel

Does XXXX LGU currently sponsor membership to Phil-Health? If so, who are they? What are the criteria? What is the process? What is the source of the premiums?

Are there other mechanisms to support health needs? (e.g., financial assistance, in kind, others)

How is PhilHealth reimbursement provided? Is it kept under a common fund or a trust fund? How does the LGU utilise the payments? How does the LGU distribute it to health workers?

What health investments are made for the LGUs' constituents?

Does the LGU have a separate trust fund for PhilHealth reimbursements?

Are several PhilHealth benefits kept in one trust fund? If so, is there a separate ledger for TB DOTS package payments and Primary Care Benefit package payments?

What actions are taken by the LCE or the LGU to facilitate the release of TB DOTS Package reimbursements to health centres? If health facilities do not receive reimbursements, what are the obstacles to providing reimbursement?

Is there any current mechanism from the LGU side to support the living allowance of TB patients (transportation costs, nutritional supplements)?

If there is no such mechanism, what would you propose to the LCE to support the living allowance of TB patients?

Do you have any suggestions on how to improve the service or services of PhilHealth?

Interview guide for the local DSWD office

How does your LGU identify poor individuals under the sponsored programme?

Does the local DSWD conduct house visits of persons classified by the barangay (local officials) as poor?

What do applicants need to submit as supporting documents under the sponsored programme?

What is the process and what documents are needed for renewal under the sponsored programme? How would you know if members are still ‘poor’?

Who pays for the PhilHealth membership of those enrolled under the sponsored programme?

Do you have any suggestions on how to improve the service or services of PhilHealth?

Interview guide for a barangay official

What is the estimated population?

Other data required: number of estimated households, number of target beneficiaries under the sponsored programme, number enrolled under the sponsored programme

In our interview with the local DSWD, we learned that one of the supporting documents required to be qualified under the sponsored programme is the ‘certificate of indigency’ from the barangay…. What are the qualifying factors for the issuance of a certificate of indigency?

Is medical assistance available at the barangay level?

Do you have suggestions on how to improve the service or services of PhilHealth?

LGU = local government unit; TB = tuberculosis; LCE = Local Chief Executive; DSWD = Department of Social Welfare and Development.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: MAR has been receiving a salary from PhilHealth as a medical specialist. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Republic of the Philippines Republic Act No. 10606. National Health Insurance Act. Manila, The Philippines: Government of the Philippines; 2013. http://www.gov.ph/downloads/2013/06jun/20130619-RA-10606-BSA.pdf Accessed November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romualdez A, Jr, dela Rosa J, Flavier J The Philippines health system review. Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. New Delhi, India: World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth) PhilHealth annual report 2015. Pasig City, The Philippines: Philippine Health Insurance Corporation; 2013. https://www.philhealth.gov.ph Accessed November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obermann K, Jowett M, Alcantara M, Banzon E, Bodart C. Social insurance in a developing country: the case of the Philippines. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:3177–3185. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Philippine Health Insurance Corporation Types of PhilHealth members. Pasig City, The Philippines: Philippine Health Insurance Corporation; 2014. https://www.philhealth.gov.ph/members/ Accessed November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth) PhilHealth Circular No 014 S-2014. Revised guidelines for the PhilHealth outpatient anti-tuberculosis directly observed treatment short-course (DOTS) benefit package. Pasig City, The Philippines: Philippine Health Insurance Corporation; 2014. https://www.philhealth.gov.ph/circulars/circ14_2014.pdf Accessed October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth) PhilHealth Circular no 015 S-2014-. Primary Benefit 1 (PCB) 1 now called ‘Tsekap’ package guideline for CY 2014. Pasig City, The Philippines: Philippine Health Insurance Corporation; 2014. https://www.philhealth.gov.ph/circulars/2014/circ15_2014.pdf Accessed November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez L. Design and implementation features of the national household targeting system in the Philippines (English). Philippine social protection note no. 5. Washington, DC, USA: World Bank; 2012. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/687351468093838577/Design-and-implementation-features-of-the-national-household-targeting-system-in-the-Philippines Accessed November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capuno J, Quimbo S, Kraft A, Tan C, Jr, Fabella V. The effects of term limits and yardstick competition on local government provision of health insurance and other public services: the Philippines case. Quezon City, The Philippines: University of the Philippines School of Economics; 2012. Discussion Paper No. 2012-01. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paterno R A. The future of universal health coverage: a Filipino perspective. Global Health Governance. 2013;VI:1–21. http://blogs.shu.edu/ghg/files/2014/02/GHGJ_62_32-52_PATERNO.pdf Accessed November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez L, Olfindo R. Overview of the Philippines conditional cash transfer program: the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (Pantawid Pamilya) Washington DC, USA: World Bank; 2011. Philippine Social Protection Note No 2. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/313851468092968987/Overview-of-the-Philippines-Conditional-Cash-Transfer-Program-the-Pantawid-Pamilyang-Pilipino-Program-Pantawid-Pamilya Accessed November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castañeda T, Lindert K, de la Brière B Designing and implementing household targeting systems: lessons from Latin America and the United States. Washington, DC, USA: the World Bank; 2005. Social Protection Discussion Paper 32756. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/566041468770480720/Designing-and-implementing-household-targeting-systems-lessons-from-Latin-American-and-The-United-States Accessed November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Australian Government Targeting the poorest: an assessment of the proxy means test methodology. Canberrra ACT, Australia: Australian Government; 2011. https://www.unicef.org/socialpolicy/files/targeting-poorest.pdf Accessed November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tolentino H, Marcelo A, Marcelo P, Maramba I. Linking primary care information systems and public health information networks: lessons from the Philippines. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2005;116:955–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garfin A M C. Survey to estimate the proportion of households experiencing catastrophic costs due to tuberculosis. Manila, The Philippines: Philippine Health Insurance Corporation; 2017. http://www.philcat.org/PDFFiles/TB-catastrophicpresentation.pdf Accessed November 2018. [Google Scholar]