Abstract

Setting: Myanmar's National Tuberculosis Programme (NTP) uses the Xpert® MTB/RIF assay to diagnose rifampicin (RMP) resistance in sputum smear-positive (Sm+) pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) patients. The Xpert test may occasionally yield negative results (Xpert–) for Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, indicating a false-positive sputum smear result, false-negative Xpert result or infection with non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM). Patients with NTM may respond poorly to first-line anti-tuberculosis treatment.

Objective: To assess the burden of Sm+, Xpert– results at the national level and treatment outcomes of Sm+, Xpert– patients in Yangon Region.

Design: A cohort study involving a retrospective record review of routinely collected NTP data.

Result: In 2015 and 2016, 4% of the 25 359 Sm+ patients who underwent Xpert testing nationally were Sm+, Xpert–. Similarly, in the Yangon Region, 5% of the 5301 Sm+ patients were also Xpert– and were treated with first-line anti-tuberculosis regimens. Smear grade (scanty/1+) and age ⩾65 years were associated with Sm+, Xpert– results. The 88% treatment success rate for this group was similar to that of Sm+, Xpert+ patients without RMP resistance.

Conclusion: Approximately 4–5% of Sm+ TB patients were Xpert–. There is an urgent need to formulate guidelines on how to reassess and manage these patients.

Keywords: tuberculosis, treatment outcomes, non-tuberculosis mycobacteria, NTP, operational research

Abstract

Contexte : Le programme national tuberculose du Myanmar (PNT) recourt au test Xpert® MTB/RIF pour diagnostiquer la résistance à la rifampicine (RMP) chez les patients atteints de tuberculose (TB) pulmonaire à frottis de crachats positif (Sm+). Les résultats du test Xpert peuvent parfois être négatifs (Xpert–) pour le complexe Mycobacterium tuberculosis indiquant soit un résultat de frottis de crachats faussement positif, soit un résultat de test Xpert faussement négatif ou une infection à mycobactéries non-tuberculeuse (NTM). Les patients atteints de NTM peuvent répondre de façon médiocre au traitement anti-tuberculose de première ligne.

Objectif : Evaluer la proportion de patients Sm+/Xpert– au niveau national et les résultats du traitement dans la région de Yangon.

Schéma : Etude de cohorte impliquant une revue rétrospective des dossiers de données recueillies en routine par le PNT.

Résultats: Au niveau national, en 2015 et 2016, 4% des 25 359 patients Sm+ qui ont eu un test Xpert ont été Xpert–. De même, dans la région de Yangon, 5% des 5301 patients Sm+ ont été Xpert– et ils ont été traités avec des protocoles anti-tuberculose de première ligne. Le grade du frottis (rare/1+) et l'âge ⩾ 65 ans ont été associés aux résultats Sm+/Xpert–. Le taux de succès du traitement a été de 88% ce qui a été similaire aux résultats des patients Sm+/Xpert+ sans résistance à la RMP.

Conclusion : La proportion de patients TB Sm+/Xpert– a été d'environ 4–5%. Il y a un besoin urgent de formuler des directives sur la manière de réévaluer et de prendre en charge de façon optimale ces patients.

Abstract

Marco de referencia: En el Programa Nacional contra la Tuberculosis (PNT) de Birmania se utiliza la prueba Xpert® MTB/RIF con el fin de diagnosticar la resistencia a rifampicina (RMP) en los pacientes con diagnóstico de tuberculosis (TB) pulmonar y baciloscopia positiva (Sm+). El resultado de la prueba Xpert en ocasiones puede ser negativa para el complejo Mycobacterium tuberculosis, lo cual puede corresponder ya sea a un resultado positivo falso de la baciloscopia del esputo, un resultado negativo falso de la prueba Xpert o a la infección por una micobacteria atípica. Los pacientes infectados por micobacterias atípicas pueden tener una respuesta deficiente al tratamiento antituberculoso de primera línea.

Objetivo: Evaluar la proporción de casos SM+, Xpert– a escala nacional y los desenlaces terapéuticos de estos pacientes en la región de Yangon.

Método: Se realizó un estudio de cohortes retrospectivo a partir del análisis de los datos corrientes recogidos en las historias clínicas en el PNT.

Resultados: A escala nacional, en el 2015 y el 2016, el 4% de los 25 359 pacientes Sm+ que realizaron la prueba Xpert obtuvo un resultado negativo. Asimismo, en la región de Yangon, el 5% de los 5301 pacientes con Sm+ tuvo un resultado negativo de la prueba Xpert y recibió tratamiento con esquemas antituberculosos de primera línea. Los factores que se asociaron con Sm+ y una prueba Xpert– fueron el grado de la baciloscopia (bacilos escasos o 1+) y la edad a ⩾ 65 años. La tasa de éxito terapéutico en estos casos fue 88%, una proporción equivalente a los desenlaces de los pacientes Sm+ y Xpert+, sin resistencia a RMP.

Conclusión: La proporción de pacientes con Sm+ y Xpert– fue del 4% al 5%. Existe una necesidad urgente de formular directrices sobre la forma reevaluar estos pacientes y tratarlos de manera óptima.

The Xpert® MTB/RIF assay (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) is the single most important development in tuberculosis (TB) diagnosis in the last 10 years. Xpert has higher sensitivity (84–92%) and specificity (98–99%) in detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis than sputum smear microscopy, and it can also detect rifampicin (RMP) resistance, with very short processing turnaround times (~2 h).1,2 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends Xpert as one of the first tests to be used in the diagnosis of TB and/or RMP resistance.3

When national TB control programmes (NTPs) use Xpert along with sputum smear microscopy in the diagnosis of pulmonary TB (PTB) and/or RMP resistance, the results of these tests (when performed simultaneously) can be concordant or discordant. Concordant results confirm the diagnosis of TB. Discordant results, where Xpert is positive (for M. tuberculosis) and sputum smear is negative, reflect additional TB cases detected due to the higher sensitivity of the Xpert over sputum smear microscopy.2,4 However, the converse, that is, when Xpert results are negative for M. tuberculosis and sputum smear is positive for acid-fast bacilli, poses a diagnostic dilemma. TB control programmes in many high-burden countries recommend reassessment of such patients for TB.5

While the clinical presentation of non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) infection is similar to that of TB, patients infected with NTM require a different group of antibiotics and longer treatment, and they may respond poorly to treatment, with cure rates ranging from 30% to 70% depending upon the NTM species.6–9 Several studies have indicated a global rise in NTM infections.10,11 If the number and proportion of Xpert-negative, sputum smear-positive results are high, this should be a cause for concern.

Myanmar is one of the 30 countries worldwide with a high burden of TB, multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) and TB-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection. Since 2011, the NTP has used both sputum smear microscopy and Xpert testing for the diagnosis of PTB and RMP resistance in certain high-risk subgroups of patients.12 Anecdotal evidence indicates several instances of sputum smear-positive, Xpert-negative results in the country.

We conducted an operational research study with two objectives. First, to describe the magnitude of smear-positive, Xpert-negative results (Sm+, Xpert–) in patients who underwent Xpert testing under the NTP in Myanmar in 2015 and 2016. Second, in a cohort of sputum smear-positive PTB patients who underwent Xpert testing between 2015 and 2016 in the Yangon Region: 1) to describe the number and proportion of patients with Xpert results positive and negative for M. tuberculosis; and 2) to compare the demographic and clinical characteristics and TB treatment outcomes among Sm+, Xpert– patients and smear-positive, Xpert-positive patients with no RMP resistance (Sm+, Xpert+, RR–) initiated on first-line anti-tuberculosis treatment.

METHODS

Study design and data sources

For the first objective, we used a cross-sectional design to describe routinely collected programmatic data extracted from the national electronic Xpert register. For the second objective, we carried out a cohort study involving secondary analysis of routinely programmatic data extracted from TB registers and Xpert registers in the Yangon Region.

Setting

National TB Control Programme

Myanmar's NTP consists of a central level office in Nay Pyi Taw and TB teams in all states, regions, districts and townships. The primary diagnostic method for drug-susceptible PTB is sputum smear microscopy (Zie-hl-Neelsen [ZN] staining, light-emitting diode-fluorescent microscopy [LED-FM]) and chest radiography. Microscopy centres (MCs) undergo external quality assessment (EQA) of sputum smear microscopy at the National TB Reference Laboratory, Yangon, Myanmar, by blinded rechecking of a sample of slides using a lot quality assurance sampling system. The number of sputum smears re-examined each month from each MC depends on the annual volume of slides and the slide positivity rate.13,14 Of the 516 MCs, 482 laboratories (93%) participated in EQA in 2015 (ZN, n = 324 sites; LED-FM, n = 158 sites); among those that participated, about 33% reported high false-positive and -negative errors during the study period.

In 2011, Xpert was introduced as the primary tool for diagnosing RMP-resistant TB. Respectively 48 and 65 Xpert sites were co-located in MCs centres in 2015 and 2016. A system of weekly sputum collection and transportation between non-Xpert MCs and Xpert sites was available. In Yangon Region, Xpert testing is recommended for all TB patients, whereas in other states and regions TB patients who fulfil any one of the following criteria undergo Xpert testing: sputum smear-positive, those with a history of previous anti-tuberculosis treatment, contacts of patients with MDR-TB, patients with diabetes mellitus, patients with HIV co-infection, and patients who are sputum smear-positive at the end of the intensive phase of treatment (i.e., non-converters). In the Yangon Region, there were 77 MCs (52 ZN and 25 LED-FM) and 12 Xpert sites. More than 95% of the MCs participated in EQA, and about 18% reported high false-positive and -negative errors.

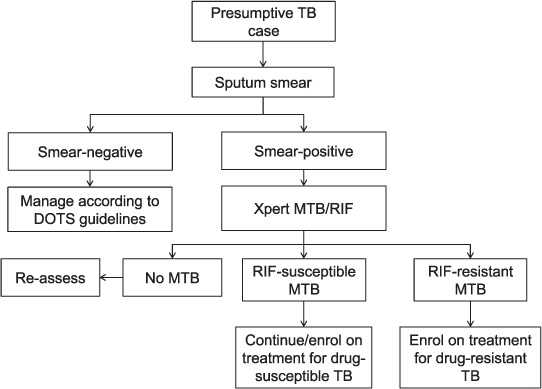

In accordance with existing national guidelines, patients who are sputum smear-positive and Xpert-positive (Sm+, Xpert+) should be initiated on first- or second-line anti-tuberculosis treatment, depending on the absence or presence of RMP resistance (Figure 1). For patients who are Sm+, Xpert–, the guidelines specify that these patients should be reassessed for TB; however, there is no further guidance on how to perform this reassessment. Under routine programmatic conditions, most of these patients are managed in the same way as Sm+, Xpert+, RR– TB patients, and are initiated on first-line anti-tuberculosis treatment. All TB patients who initiate first-line anti-tuberculosis treatment are recorded in the drug-susceptible TB registers at each township. All case definitions and treatment outcome definitions are in accordance with standard WHO TB treatment guidelines.15,16

FIGURE 1.

Algorithm for Xpert® MTB/RIF testing in Myanmar, 2016–2017. TB = tuberculosis; MTB = Mycobacterium tuberculosis; RIF = rifampicin.

Study population, study variables, data collection

For our first study objective, we included all sputum smear-positive TB patients who underwent Xpert under the NTP in Myanmar in 2015 and 2016 and were recorded in the national electronic Xpert register. For the second objective, we restricted our study to three townships in 2015 and 25 townships in 2016 in Yangon Region that reported Sm+, Xpert– patients in the national Xpert register. In this region, we selected all sputum smear-positive PTB patients who underwent Xpert during the defined period. Yangon Region was chosen for this study because it is the most populous region of the country and has the highest number of Xpert machines and sites, and we assumed that the results from this region could be generalised to other parts of the country.

Variables extracted from the electronic Xpert registers and TB registers included individual patient data on Xpert registration number, Xpert results, TB registration number, age, sex, type of TB, sputum smear grade, HIV status, year, first-line anti-tuberculosis treatment regimen and TB treatment outcomes. Unfortunately, the name of the MC where the patient underwent sputum smear and the type of sputum smear microscopy was not available in either the national electronic Xpert register or the township TB registers.

Analysis and statistics

For the first objective, we summarised the data using numbers and proportions of Sm+ Xpert–, Sm+ Xpert+ RR–, Sm+ Xpert+ RR+ patients, disaggregated by standard WHO age group, sex, HIV status, type of TB (new/retreatment TB) and year. For the second objective, we used prevalence ratios to describe and compare the demographic and clinical characteristics of Sm+ Xpert– patients and Sm+ Xpert+ RR– TB patients. We used multivariable log binomial models (Poisson models with robust standard error estimates if the log binomial models failed to achieve convergence) to derive prevalence ratios. We also used these models to assess the relative differences in treatment outcomes in the two groups of patients (Sm+ Xpert– and Sm+ Xpert+ RR–) after adjusting for age, sex, type of TB, HIV status and sputum smear grade and after accounting for clustering of data at the township levels. Significance levels were set at 5%. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata statistical software v 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics

Permission for the study protocol was obtained from the Myanmar NTP. We obtained ethics approval from the Myanmar Department of Medical Research (DMR), Ministry of Health and Sports Nay Pyi Taw, Yangon, and the Ethics Advisory Group of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (Paris, France).

RESULTS

Magnitude of Sm+, Xpert– patients in Myanmar

In 2015 and 2016, of 25 359 Sm+ patients nationally who underwent Xpert testing and had valid results, 918 (4%) were Xpert-negative for M. tuberculosis. The proportion of Sm+, Xpert– patients ranged from 3% to 17% across the 15 states/regions of the country. The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with Xpert– and Xpert+ results, disaggregated by RMP resistance status, is shown in Table 1. Patients aged <15 years or ⩾45 years (compared to patients aged 15–44 years), females (compared to males), previously treated TB patients (compared to new cases) and HIV-positive patients (compared to HIV-negative patients) were more likely to have Xpert– results in both unadjusted and adjusted analysis.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Sm+ TB patients who underwent Xpert testing, disaggregated by Xpert result, Myanmar, January 2015–December 2016

Sm+, Xpert– patients in Yangon Region

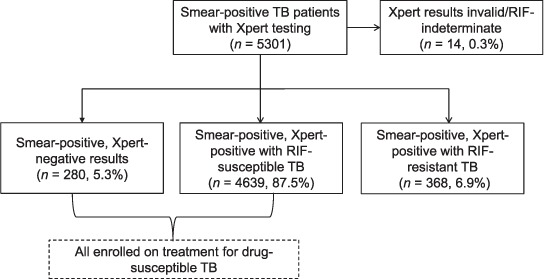

In 2015 and 2016, 5301 sputum smear-positive TB patients in the Yangon Region underwent Xpert testing. Of these, 280 (5%) had an Xpert– result for M. tuberculosis (Figure 2). All of these patients were on first-line anti-tuberculosis treatment. The characteristics of Sm+, Xpert– patients compared to Sm+, Xpert+, RR– patients are shown in Table 2. Patients aged ⩾65 years were 1.9 times more likely to have a Xpert– result than patients aged 15–64 years; patients with scanty and 1+ sputum smear grade were respectively 5.6 times and 3.9 times more likely to have an Xpert– result compared to those with sputum smear grade 3+. In absolute proportions, ⩾10% of the patients with scanty or 1+ grade were Xpert–.

FIGURE 2.

Status of sputum smear-positive TB patients who underwent Xpert® MTB/RIF testing in 25 townships in the Yangon Region, Myanmar, January 2015–December 2016. TB = tuberculosis; RIF = rifampicin.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of smear-positive TB patients who underwent Xpert testing in 25 townships in the Yangon Region, Myanmar, January 2015–December 2016

Comparison of treatment outcomes in Sm+, Xpert– vs. Sm+, Xpert+, RR– patients

Treatment outcomes disaggregated by Xpert result are shown in Table 3. Overall, 87% of the patients had a successful treatment outcome (cured or treatment completed): 88% among Sm+ Xpert– patients and 87% among Sm+ Xpert+ RR– patients. After adjusting for age group, sex, type of TB, HIV status and smear grade, the probabilities of an unsuccessful outcome were similar in both groups (adjusted risk ratio 1.1, 95% confidence intervals 0.8–1.6).

TABLE 3.

Treatment outcomes of smear-positive TB patients who underwent Xpert testing in 25 townships of the Yangon Region, Myanmar, January 2015–December 2016

DISCUSSION

This is one of the first studies from an NTP in a high TB burden country to describe the magnitude and treatment outcomes of sputum smear-positive, Xpert-negative patients. There are three important findings from this study. First, 4–5% of the sputum smear-positive patients tested using Xpert were negative. Second, sputum smear grade scanty and 1+ and age ⩾65 years were the two most important characteristics independently associated with Xpert– results. Third, the treatment outcomes of Sm+ Xpert– patients on first-line anti-tuberculosis treatment are similar to those of Sm+ Xpert+ RR– patients.

The main strength of the study is the use of routine NTP data covering 2 years without excluding any patient subgroups. As we used individual patient data at national level and from one of the most populous regions of the country, we feel the study findings represent TB patients with Sm+ Xpert– results in Myanmar; this needs to be confirmed or refuted in future studies.

There were two major limitations: first, as we used data from routine programme records and reports, our analysis and interpretation are limited to those variables that are routinely recorded. Some key variables, such as the name of the MC or whether the initial sputum smear examination was performed using ZN or LED-FM was not recorded in either the TB or the Xpert registers. We are therefore unable to assess whether the discordance was higher with ZN or LED-FM, and how this might influence the estimates of the magnitude and other associations observed in this study. Similarly, we did not have information on whether or not Sm+, Xpert– patients were reassessed for TB, and if so, how they were reassessed; we could therefore not use this information in our analysis and interpretation of the results. Second, there may be errors in the recording and reporting system that we are not aware of. However, as all supervision and monitoring are done by the NTP, we feel that errors in recording and reporting are likely to be minimal and random.

The study findings have the following implications for policy and practice: first, the proportion of sputum smear-positive patients who had Xpert-negative results was around 4–5% at both national level and Yangon regional level. Sputum smear grade scanty or 1+ and age ⩾65 years were strongly associated with Xpert-negative results. Based on these findings, we feel that the magnitude of Sm+ Xpert– cases at any given place or year will depend on the proportion of patients with these characteristics. The higher the proportion of sputum Sm+ patients with scanty and 1+ grade or patients aged ⩾65 years, the greater the number of Sm+ Xpert– results to be expected.

Second, we found that sex, type of TB and HIV status were associated with Sm+ Xpert– results in the data from the national electronic Xpert register (Table 1), but not in the data from Yangon Region (Table 2) which also contained information on sputum smear grade. This indicates that the magnitude and direction of associations seen in Table 1 is likely to be biased due to unmeasured confounding and that sputum smear grade is the unmeasured confounder. We have not elaborated on these associations in this article. Whether sex, type of TB and HIV status are truly associated/not associated with Sm+ Xpert– results needs to be confirmed in future studies.

Third, previous studies have shown that advanced age is an independent predictor of NTM infection17,18 and that lower sputum smear grade (scanty and 1+) is associated with false-positive sputum smears.19,20 Sputum smear microscopy EQA data extracted from the Myanmar NTP reports indicate that approximately 0.3% of sputum specimens received at EQA centres were false-positive in 2015.21 Given these known associations and our study observations, and as sputum culture was not performed in our study, we are unable to confirm which of these predictors—false-positive sputum smears, false-negative Xpert results or NTM—was responsible for the Sm+, Xpert– results in our setting.

Fourth, around 88% of the Sm+ Xpert– patients had a successful treatment outcome, similar to that in Sm+ Xpert+ RR– patients. This finding is reassuring. However, the question as to whether it is correct to treat these patients with anti-tuberculosis treatment remains unanswered in our study. To address this issue, we recommend two immediate actions by the NTP: 1) formulate guidelines for the reassessment of these cases and provide guidance on how they should be managed; and 2) conduct further research to assess the reasons for Sm+ Xpert– results.

Finally, the NTPs of several high TB burden countries are currently scaling up Xpert testing.22 They are all likely to encounter Sm+, Xpert– results, and need to develop specific plans to explore and address this issue; international technical agencies such as the WHO can help NTPs in this regard by formulating appropriate guidelines.

In conclusion, about one in 20 smear-positive patients in Myanmar had an Xpert result negative for M. tuberculosis. Patients with low sputum smear grade (scanty/1+) and those aged ⩾65 were more likely to have a negative Xpert result. The TB treatment outcomes of these patients were good. There is an urgent need to formulate guidelines on how to manage these patients and to conduct microbiological research studies to identify the real reasons for Sm+, Xpert– results in this setting.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted through the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT), a global partnership led by the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases at the World Health Organization (WHO/TDR). The model is based on a course developed jointly by the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union; Paris, France) and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF/Doctors Without Borders; Paris, France). The specific SORT IT programme which resulted in this publication was jointly organised and implemented by The Centre for Operational Research, The Union; Department of Medical Research, Ministry of Health and Sports, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar; the Department of Public Health, Ministry of Health and Sports, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar; The Union Country Office, Mandalay, Myanmar; The Union SouthEast Asia Office, New Delhi, India; and Burnet Institute, Melbourne, VIC, Australia. The training programme in which this paper was developed was funded by the Department for International Development (DFID), London, UK; the United States Agency for International Development (USAID; Washington DC, USA) through Challenge TB and FHI 360. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Marlowe E M, Novak-Weekley S M, Cumpio J et al. Evaluation of the Cepheid Xpert MTB/RIF assay for direct detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in respiratory specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:1621–1623. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02214-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steingart K R, Schiller I, Horne D J, Pai M, Boehme C C, Dendukuri N. Xpert® MTB/RIF assay for pulmonary tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(1):CD009593. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009593.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Automated real-time nucleic acid amplification technology for rapid and simultaneous detection of tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance: Xpert MTB/RIF system. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vadwai V, Boehme C, Nabeta P, Shetty A, Alland D, Rodrigues C. Xpert MTB/RIF: a new pillar in diagnosis of extra-pulmonary tuberculosis? J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2540–2545. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02319-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization Xpert MTB/RIF implementation manual. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffith D E, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott B A et al. An Official ATS/IDSA Statement: diagnosis, treatment and prevention of non-tuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diel R, Lipman M, Hoefsloot W. High mortality in patients with Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:206. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3113-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsson L-O, Polverino E, Hoefsloot W et al. Pulmonary disease by non-tuberculous mycobacteria—clinical management, unmet needs and future perspectives. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2017;11:1–13. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2017.1386563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.López-Varela E, García-Basteiro A L, Santiago B, Wagner D, van Ingen J, Kampmann B. Non-tuberculous mycobacteria in children: muddying the waters of tuberculosis diagnosis. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:244–256. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stout J E, Koh W J, Yew W W. Update on pulmonary disease due to non-tuberculous mycobacteria. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;45:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brode S K, Daley C L, Marras T K. The epidemiologic relationship between tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial disease: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18:1370–1377. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Tuberculosis Programme National strategic plan for tuberculosis (2016–2020) Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar: NTP; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratory National guidelines on external quality assessment. LQAS for sputum AFB microscopy. Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar: NTRL; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Tuberculosis Programme Standard operating procedure for fluorescence microscopy with auramine staining. Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar: NTP; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization Treatment of tuberculosis guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2010. WHO/HTM/TB/2009.420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization Guidelines for treatment of drug-susceptible tuberculosis and patient care. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2017. pp. 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menzies D, Nahid P. Update in tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial disease, 2012. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:923–927. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201304-0687UP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koh W J, Yu C M, Suh G Y et al. Pulmonary TB and NTM lung disease: comparison of characteristics in patients with AFB smear-positive sputum. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:1001–1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frieden T R, editor. Toman's tuberculosis: case detection, treatment, and monitoring : questions and answers. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. WHO/HTM/TB/2004.334. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chao W, Huang Y, Yu M et al. Outcome correlation of smear positivity but culture negativity during standard anti-tuberculosis treatment in Taiwan. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:67. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0795-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Tuberculosis Programme Annual Report 2016. Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar: NTP; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cazabon D, Suresh A, Oghor C et al. Implementation of Xpert MTB/RIF in 22 high tuberculosis burden countries: are we making progress? Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1700918. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00918-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]