Abstract

Background/Summary

Acute colonic diverticular hemorrhage (CDH) represents a significant challenge for gastroenterologists. There are some clinical problems in the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of CDH. CDH is the most common cause of overt lower gastrointestinal bleeding in adults in Eastern and Western countries. Moreover, CDH imposes significant economic and clinical burdens on the health care system. Colonoscopy is recommended as a useful diagnostic tool for CDH after bowel preparation. Colonoscopy can be used to identify the culprit diverticulum and to provide endoscopic therapy. In most cases, however, the bleeding stops spontaneously. For this reason, it is still controversial whether urgent colonoscopy or elective colonoscopy is “preferable.”

Key Messages

This review aims to highlight the various clinical problems (purge, timing of colonoscopy, CT angiography, and endoscopy) encountered in the attempt to identify and treat the culprit diverticulum red-handed.

Keywords: Colonic diverticular hemorrhage, Bowel preparation, Colonoscopy, CT angiography

Introduction

Diverticulosis and colonic diverticular diseases (CDDs) are increasingly common clinical conditions that are more frequently encountered in elderly patients and industrialized countries [1]. One of the chief complications of CDDs is colonic diverticular hemorrhage (CDH), and the incidence rate has been increasing. CDH is the most common cause of severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) in adults, accounting for 30–50% of cases of massive rectal bleeding [2, 3, 4]. Among patients with CDDs, the risk of bleeding is approximately 0.5 per 1,000 person-years [5]. In a study of 1,514 asymptomatic patients with CDDs, the cumulative incidence of bleeding was 0.2% at 12 months, 2.2% at 60 months, and 9.5% at 120 months [5]. Risk factors for bleeding include an age > 70 years (adjusted hazard ratio 3.7) and bilateral diverticulosis (adjusted hazard ratio 2.4). Obesity also appears to increase the risk of diverticulitis and CDH [6].

As a diverticulum herniates, the penetrating vessel responsible for the wall weakness at that point becomes draped over the dome of the diverticulum and is separated from the bowel lumen only by mucosa. Over time, the vasa recta are exposed to injury along their luminal aspect, leading to eccentric intimal thickening and thinning of the media. These changes may result in segmental weakness of the artery, predisposing to rupture into the lumen [7]. Unlike diverticulitis, which occurs primarily in the left colon, the right colon is the source of colonic diverticular bleeding in 50–90% of patients [2, 7, 8, 9]. This reflects a marked increase in the propensity for right-sided diverticula to bleed, since, in Western countries, only 25% of diverticula are right-sided [10]. A possible explanation for this is that right-sided diverticula have wider necks and domes, exposing a greater length of the vasa recta to injury. Another contributing factor may be the thinner wall of the right colon [11].

In most cases of CDH, the bleeding will stop spontaneously (in 75% of patients overall), and 99% of the patients who are transfused require fewer than 4 units per day [12]. Thus, most endoscopists believe that urgent colonoscopy is not necessary to identify the stigma of bleeding from lower gastrointestinal lesions, such as diverticula, since the important clinical issue in CDH is that bleeding diverticula are difficult to identify.

Diagnosis

Exclusion of upper gastrointestinal bleeding by endoscopy is necessary because 10–15% of hematochezia cases have a cause lying in the upper gastrointestinal tract [13]. Particularly in patients with hemodynamic instability, a history of peptic ulcers, and portal hypertension, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy should be considered early. The diagnosis of CDH may be made by colonoscopy or radiographic imaging. Colonoscopy is a useful procedure for nearly all patients presenting with acute LGIB, because it serves as a diagnostic and potentially therapeutic tool [14, 15]. The advantage of colonoscopy over other diagnostic modalities is its ability to directly visualize lesions, allowing for the exclusion of other etiologies of LGIB, as well as for immediate therapy. Colonoscopy is safe and effective, with a diagnostic yield of 69–80% in acute LGIB [16, 17, 18, 19]. Aspiration (in upper endoscopy), oversedation, hypoventilation, and vasovagal events are the major problems of this modality. In a review of 4 studies with 549 urgent colonoscopies performed for LGIB, only one complication (diverticular perforation) was reported [16, 17, 18, 19].

The source of bleeding in patients presenting with CDH is diagnosed when the stigma of recent hemorrhage (SRH) is defined as active bleeding from a diverticulum, a nonbleeding visible vessel, or an adherent clot. Also, CT enterography is another management option in patients without any identifiable source of LGIB. The second aim of colonoscopy in acute LGIB should be to identify patients with a risk of rebleeding. Jensen et al. [20] and Mizuki et al. [21] showed that SRH is associated with a severe course or high rate of rebleeding. In the retrospective study of 88 patients with CDH by Mizuki et al. [21], 24 (38.7%) of 62 conservatively treated patients and 16 (61.5%) of 26 endoscopically treated patients experienced recurrences of CDH during the follow-up period (the median follow-up period [interquartile range] was 42.7 [61.8] months).

Barium impaction could be a possible management option for patients with recurrent hemorrhage in whom a dynamic CT and purge colonoscopy failed to identify the culprit lesion. In a prospective study by Nagata et al. [22], after spontaneous cessation of bleeding, conservative treatment (n = 27) and high-dose barium impaction therapy (n = 27) were tracked. In the median follow-up period of 584.5 days, the probability of rebleeding at 1 year was 42.5% in the conservative group and 14.8% in the barium group (log-rank test, p = 0.04).

Bowel Preparation

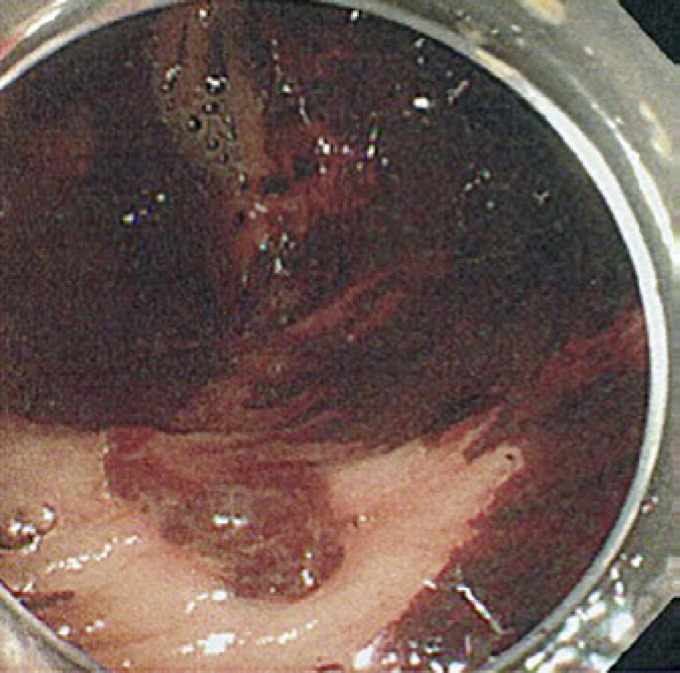

The necessity of colonic purging prior to colonoscopy is unclear. However, adequate preparation of the colon seems important for endoscopic visualization and diagnosis. This procedure improves the evaluation of the mucosa, which in turn enhances the recognition of smaller lesions and minimizes the risk of complications resulting from poor vision. Even after adequate bowel preparation, urgent colonoscopy could result in an incomplete examination in 0–45% of cases, but the risk of complications due to colonoscopy does not exceed 11%. The method allows a positive diagnosis in approximately two-thirds of cases and achieving hemostasis in one-third, resulting in a shortened duration of hospitalization [16, 23, 24, 25]. However, no randomized controlled trial has determined whether the 4-L or the 2-L preparation produces a better outcome [20]. Jensen et al. [20] and Mizuki et al. [21] reported the necessity of colon preparation. Jensen et al. [20] performed an urgent colonoscopy after colon preparation using a 5- to 6-L sulfate purge and reported that the diagnosis by colonoscopy was determined in 70.1% of the cases. In the retrospective study of 110 patients with colonic CDH by Mizuki et al. [21], colon preparation with a polyethylene glycol purge as compared to no preparation allowed for a higher rate of identification of bleeding diverticula (28.2 vs. 12.0%; p = 0.11), although the difference was statistically nonsignificant. In addition, 12.0% (3/25) of the “no preparation” group demonstrated no stool in the colon, except for focal streaming of blood [21] (Fig. 1). The additional use of a waterjet scope to remove debris has been described to increase SRH detection by colonoscopy, although this warrants further evaluation [24].

Fig. 1.

A 75-year-old woman with active colonic diverticular hemorrhage on endoscopy. The image from unprepped colonoscopy shows active bleeding from the colonic diverticulum and the presence of clots, blood, and stools.

On the other hand, Chaudhry et al. [23] performed urgent colonoscopy for LGIB without colonic preparation. They suggested that the information gained from the amount and distribution of blood in the colon may support obtaining the diagnosis. In a prospective study by Repaka et al. [26], 13 procedures were performed on 12 patients with severe LGIB using unprepped hydroflush colonoscopy (a colonoscopy technique using a combination of the standard colonoscope, waterjet pump irrigation, and a mechanical endoscopic suction device); complete colonoscopy of the cecum was performed only in 69.2% (9/13) of the patients. However, in 13 cases, endoscopic visualization was adequate for definitively or presumptively identifying the source of bleeding in all procedures, without repeat colonoscopic examination due to inadequate preparation. A definite source of bleeding was identified in 5 of the 13 procedures (38.5%) [26]. With the polyethylene glycol purge, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, etc., were minor problems.

Timing of Colonoscopy

It is commonly accepted that early colonoscopy within 48 h may improve both the diagnosis and management of the bleeding. Urgent colonoscopy improves the diagnostic yield [13, 20, 25], reduces the length of hospital stay [27], and possibly decreases the cost of care [28]. However, the optimal time for performing urgent bowel preparation and colonoscopy is controversial.

In their prospective study, Jensen et al. [20] identified a stigma of hemorrhage in approximately 20% of the patients with CDH undergoing urgent colonoscopy who underwent 5- to 6-L sulfate purging within 6–12 h of admission. In a trial by Green et al. [13] that compared colonoscopy following bowel preparation within 12 h versus elective colonoscopy (within 74 h), a definitive source of bleeding was identified in 42 and 22% of the patients that received urgent and elective colonoscopy, respectively. In a review of 78 colonoscopies from the Mayo Clinic [29], patients with CDH underwent colonoscopy an average of 18 ± 11 h (range 0–59) after presentation to the hospital. No significant relationship between diagnostic yield and timing of index colonoscopy was discovered. However, in the retrospective study of 110 patients with colonic CDH by Mizuki et al. [21], the detection rate was significantly higher when colonoscopic examination was performed within 18 h of the final hematochezia than when it was performed after 18 h (40.5 vs. 10.5%; p < 0.01). In a retrospective study by Strate and Syngal [30], initial colonoscopy within 24 h of admission offered a diagnostic yield of 85 versus 45% for initial scintigraphy versus angiography. Within 36–60 h, Laine and Shah [31] found no difference in outcomes including the number of diagnoses. However, 78% of the colonoscopies were diagnostic in the urgent group as compared to 67% in the elective group, and the only two stigmata of hemorrhage were both identified in patients with diverticulosis who underwent colonoscopy. A recent, large study using the 2010 Nationwide Inpatient Sample data set of 58,296 discharged LGIB patients (9,156 of whom had CDH) found that early colonoscopy (performed within 24 h) was associated with statistically significant outcomes with respect to the length of hospital stay and hospitalization costs; however, no diagnoses were mentioned.

The mechanism behind colonic diverticular bleeding is not completely understood. CDH usually stops spontaneously in up to 90% of cases [32]. However, emergent colonoscopy should be considered within 24 h after admission in cases of CDH in order to identify the culprit diverticulum.

CT Angiography

There is another potential management option: CT. CT scanning - and, more specifically, CT angiography (CTA) - is commonly used in patients with LGIB [33]. Contraindications to CTA include acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease [34]. Although acute kidney injury is reversible in most cases, its development may be associated with adverse outcomes.

A typical CTA finding in CDH is a colonic diverticulum with extravasation of contrast material [35, 36], and patients with this finding could be prepared for emergency colonoscopy. However, a CT scan finding such as colonic wall thickening may indicate diseases including inflammatory disease, ischemic colitis, and colorectal carcinoma [37, 38]. CTA is useful for detecting CDH [39]. CTA may identify the area of the bleeding, but it does not inform on its pathologic cause. Only colonoscopy can confirm the exact source of bleeding (diverticulosis, arteriovenous malformation, Dieulafoy's lesion, etc.). Extravasation of contrast medium was observed in 30% of all patients with LGIB and in 68% of the patients with CDH. In patients with CDH, CTA is mandatory before colonoscopy, because identifying the source of bleeding prior to surgery may result in less invasive urgent colonoscopy and more effective hemostasis [40]. For CTA, a total of 90 mL of iopamidol was power-injected intravenously at a rate of 1.5 mL/s. The patients were scanned using 16- or 64-slice detector CT. The presence of diverticular bleeding on CTA was defined as follows: the visualization of colonic diverticula and extravasation of contrast material into the bowel lumen on arterial-phase images and/or abdominal colonic wall enhancement (Fig. 2) [40]. This CT-based test has largely replaced red blood cell-labeled scintigraphy at many centers as the first radiologic investigation and is sensitive for bleeding rates as low as 0.2 mL/min [41]. Since CTA is rapid, noninvasive, and highly reproducible, it is commonly used in LGIB emergencies, although the optimal timing and patient characteristics for the diagnosis of colonic diverticular bleeding have not been established.

Fig. 2.

An 89-year-old man with active colonic diverticular hemorrhage on endoscopy and CT. a The image from colonoscopy after bowel preparation shows active bleeding from the colonic diverticulum. b The CT angiograms show extravasation of contrast agent (arrows) from the colonic diverticulum into the colonic lumen.

Nakatsu et al. [40] stressed that CTA is a useful initial radiological test for determining the optimal timing for colonoscopy in patients with acute LGIB. Emergency colonoscopy should be considered in cases of acute LGIB associated with extravasation of contrast material into the bowel lumen from colonic diverticula, as the rate of detection of the source of bleeding on urgent colonoscopy was very high in such cases in their study. In contrast, elective colonoscopy should be considered in patients with acute LGIB and presenting with colonic wall thickening suggestive of colonic inflammation or neoplasms [42]. In a prospective study of 52 patients with CDH by Obana et al. [36], 8 positive CTAs before colonoscopy compared to 44 negative CTAs allowed for a higher rate of identified bleeding diverticula (50 vs. 36.3%; p = 0.6379), although the difference was not significant. Moreover, they analyzed the interval from the latest episode of LGIB to the time of CTA. The interval was 1.6 ± 4.6 h (mean ± SD) in patients that underwent CTA, and 3.4 ± 3.2 h in those without CTA [36]. In a retrospective study of 95 patients with CDH by Kominami et al. [35], 60 CTAs before colonoscopy compared to 35 assessments by colonoscopy alone allowed for a higher rate of identified bleeding diverticula (73.3 vs. 51.4%; p = 0.026), with the difference being statistically significant. Moreover, the interval between the bleeding being recognized and CTA (median 1.0 h) in patients in whom extravasation was detected by CTA was shorter than in those patients in whom extravasation was not detected (median 5.0 h) [36].

As previously described, several factors influence the ability to visualize active bleeding on CTA, including the nature of the bleeding lesion (bleeding rate and intermittence) and patient factors (hemodynamic status and body mass index), as well as the CTA technique (rate of injection, concentration of iodine in contrast material, number of phase, type of scanner, and postprocessing) and the experience of the radiologist [42, 43].

Endoscopic Therapy

Immediate fluid and blood product resuscitation is necessary for patients with suspected CDH. Packed red blood cells should be transfused to maintain hemoglobin > 7 g/dL. A threshold of 9 g/dL should be considered for patients with massive bleeding, significant comorbid illness (especially cardiovascular disease), or a possible delay in receiving therapeutic interventions [44, 45]. A restrictive transfusion strategy with a transfusion threshold for hemoglobin > 7 g/dL improved survival and decreased rebleeding when compared with a threshold of 9 g/dL [46]. Endoscopic hemostasis may be considered for inpatients with an international normalization ratio of 1.5–2.5 before or concomitant with the administration of reversal agents. The presence of a coagulopathy-prothrombin time/international normalization ratio > 2.5 should be corrected using fresh frozen plasma or prothrombin complex concentrate and vitamin K before endoscopy [47, 48]. In patients with significant thrombocytopenia (< 50,000/μL), platelet transfusion can be considered [49, 50]. For patients who have been treated with anticoagulant agents, a multidisciplinary approach (e.g., hematology, cardiology, neurology, and gastroenterology) should be performed when physicians decide whether or not to discontinue medication or use reversal agents to make a balance between the risk of active bleeding and the risk of thromboembolic events [49, 51]. In some cases (e.g., a patient should be off aspirin solely for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease), the decision to stop the agent may be straightforward. However, in more complicated cases, consultation with the physician who prescribed the medication may be needed. In general, aspirin should be continued for secondary prophylaxis in patients with high-risk cardiovascular disease. Dual antiplatelet therapy should not be discontinued in patients with an acute coronary syndrome within the past 90 days or with bare-metal stents placed within the preceding 6 weeks or drug-eluting stents within the preceding 6 months [52].

Endoscopic hemostasis should be provided to patients with high-risk signs of bleeding such as active bleeding, a nonbleeding visible vessel, or an adherent clot [15, 20]. In addition to urgent colonoscopy, Niikura et al. [52] found that a clear cap attachment and an endoscope with a water pump could be useful to identify SRH. The clear cap attachment and endoscope with a waterjet can solve problems concerning irrigation of the diverticula as well as suctioning and dislodgment of fibrin clots. It is useful to examine diverticula that are located behind folds, and to inspect the neck carefully and evert and evaluate the mucosal lining of a diverticular dome [53].

Epinephrine injection therapy can be used for the initial control of an active bleeding lesion and for improving visualization of the lesion [13, 20, 25]. This treatment, however, often provides only temporary cessation of the hemorrhage, with a significant risk of early rebleeding within 30 days [54]. Therefore, injection therapy should be used with a second hemostasis modality including mechanical or contact thermal therapy [13, 20, 25]. Hemostatic clips following injection therapy could achieve sustained hemostasis [21]. Through-the-scope endoscopic clips may be safer than contact thermal therapy in the colon [15, 53]. Direct clipping of an exposed vessel or erosion is superior to clipping of the entire diverticular orifice [55].

Endoscopic band ligation may be safe, effective, and superior to endoscopic clipping for the treatment of CDH, resulting in resolution of the diverticulum itself. It is argued that endoscopic band ligation should be attempted as the initial therapy especially for hemostasis of a diverticulum in the right-sided colon [56, 57]. Urgent colonoscopy should be performed using a waterjet scope. When sources of bleeding are identified, marking with hemoclips is recommended to identify diverticula with SRH. Tattooing for marking should not be performed. Subsequently, the endoscope is removed and reinserted after a band ligator device is attached to the tip of endoscope. The colonic diverticulum will be suctioned into the suction cup of the endoscopic ligator, and the elastic O ring is released in cases not successfully treated with endoscopic band ligation [56, 57].

Conclusion

In many cases, CDH occurs intermittently or ceases spontaneously, presenting a major diagnostic dilemma. CTA is proposed as the first-line diagnostic modality for the evaluation of patients with CDH. CTA should be performed as soon as possible after the clinical detection of active bleeding in order to maximize potential detection, associated with extravasation of contrast material into the bowel lumen from colonic diverticula. Moreover, CTA should be followed by emergency colonoscopy after bowel preparation within 24 h of admission in cases of CDH.

Disclosure Statement

All authors declare no financial or other relationships.

References

- 1.Fong SS, Tan EY, Foo A, Sim R, Cheong DM. The changing trend of diverticular disease in a developing nation. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:312–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gostout CJ, Wang KK, Ahlquist DA, Clain JE, Hughes RW, Larson MV, Petersen BT, Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Viggiano TR, et al. Acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Experience of a specialized management team. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;14:260–267. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199204000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Browder W, Cerise EJ, Litwin MS. Impact of emergency angiography in massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Surg. 1986;204:530–536. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198611000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gayer C, Chino A, Lucas C, Tokioka S, Yamasaki T, Edelman DA, Sugawa C. Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding in 1,112 patients admitted to an urban emergency medical center. Surgery. 2009;146:600–606. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niikura R, Nagata N, Shimbo T, Aoki T, Yamada A, Hirata Y, Sekine K, Okubo H, Watanabe K, Sakurai T, Yokoi C, Mizokami M, Yanase M, Akiyama J, Koike K, Uemura N. Natural history of bleeding risk in colonic diverticulosis patients: a long-term colonoscopy-based cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:888–894. doi: 10.1111/apt.13148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strate LL, Liu YL, Aldoori WH, Syngal S, Giovannucci EL. Obesity increases the risks of diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:115–122. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.025. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyers MA, Alonso DR, Gray GF, Baer JW. Pathogenesis of bleeding colonic diverticulosis. Gastroenterology. 1976;71:577–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casarella WJ, Kanter IE, Seaman WB. Right-sided colonic diverticula as a cause of acute rectal hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 1972;286:450–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197203022860902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong SK, Ho YH, Leong AP, Seow-Choen F. Clinical behavior of complicated right-sided and left-sided diverticulosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:344–348. doi: 10.1007/BF02050427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rege RV, Nahrwold DL. Diverticular disease. Curr Probl Surg. 1989;26:133–189. doi: 10.1016/0011-3840(89)90031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imbembo AL, Baily RW, Diverticular disease of the colon . Textbook of Surgery. In: Sabiston DC Jr, editor. ed 14. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 1992. p. p 910. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGuire HH., Jr Bleeding colonic diverticula. A reappraisal of natural history and management. Ann Surg. 1994;220:653–656. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199411000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green BT, Rockey DC, Portwood G, Tarnasky PR, Guarisco S, Branch MS, Leung J, Jowell P. Urgent colonoscopy for evaluation and management of acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2395–2402. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Pasha SF, Shergill A, Acosta RD, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Early D, Evans JA, Fisher D, Fonkalsrud L, Hwang JH, Khashab MA, Lightdale JR, Muthusamy VR, Saltzman JR, Cash BD. The role of endoscopy in the patient with lower GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:875–885. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strate LL, Gralnek IM. ACG clinical guideline: management of patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:755. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen DM, Machicado GA. Diagnosis and treatment of severe hematochezia. The role of urgent colonoscopy after purge. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:1569–1574. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(88)80079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossini FP, Ferrari A, Spandre M, Cavallero M, Gemme C, Loverci C, Bertone A, Pinna Pintor M. Emergency colonoscopy. World J Surg. 1989;13:190–192. doi: 10.1007/BF01658398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caos A, Benner KG, Manier J, McCarthy DM, Blessing LD, Katon RM, Gogel HK. Colonoscopy after Golytely preparation in acute rectal bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8:46–49. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198602000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forde KA. Colonoscopy in acute rectal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981;27:219–220. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(81)73225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen DM, Machicado GA, Jutabha R, Kovacs TO. Urgent colonoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of severe diverticular hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:78–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001133420202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mizuki A, Tatemichi M, Hatogai K, Iwasaki H, Izumiya M, Maeda N, Nakazawa A, et al. Timely colonoscopy leads to faster identification of bleeding diverticulum (in Japanese) Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2013;110:1927–1933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagata N, Niikura R, Shimbo T, Ishizuka N, Yamano K, Mizuguchi K, Akiyama J, Yanase M, Mizokami M, Uemura N. High-dose barium impaction therapy for the recurrence of colonic diverticular bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2015;261:269–275. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaudhry V, Hyser MJ, Gracias VH, Gau FC. Colonoscopy: the initial test for acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Am Surg. 1998;64:723–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmulewitz N, Fisher DA, Rockey DC. Early colonoscopy for acute lower GI bleeding predicts shorter hospital stay: a retrospective study of experience in a single center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:841–846. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strate LL, Syngal S. Timing of colonoscopy: impact on length of hospital stay in patients with acute lower intestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:317–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Repaka A, Atkinson MR, Faulx AL, Isenberg GA, Cooper GS, Chak A, Wong RC. Immediate unprepared hydroflush colonoscopy for severe lower GI bleeding: a feasibility study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.03.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strate LL, Naumann CR. The role of colonoscopy and radiological procedures in the management of acute lower intestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen DM, Machicado GA. Colonoscopy for diagnosis and treatment of severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Routine outcomes and cost analysis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1997;7:477–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smoot RL, Gostout CJ, Rajan E, Pardi DS, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Nolte T, Melton LJ. Is early colonoscopy after admission for acute diverticular bleeding needed? Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1996–1999. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strate LL, Syngal S. Predictors of utilization of early colonoscopy vs radiography for severe lower intestinal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:46–52. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laine L, Shah A. Randomized trial of urgent vs elective colonoscopy in patients hospitalized with lower GI bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2636–2641. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis M. Bleeding colonic diverticula. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:1156–1158. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181862ad1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwab SJ, Hlatky MA, Pieper KS, Davidson CJ, Morris KG, Skelton TN, Bashore TM. Contrast nephrotoxicity: a randomized controlled trial of a nonionic and an ionic radiographic contrast agent. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:149. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198901193200304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laing CJ, Tobias T, Rosenblum DI, Banker WL, Tseng L, Tamarkin SW. Acute gastrointestinal bleeding: emerging role of multidetector CT angiography and review of current imaging techniques. Radiographics. 2007;27:1055–1070. doi: 10.1148/rg.274065095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kominami Y, Ohe H, Kobayashi S, Uchida D, Numata N, Matsushita H, Morimoto Y, Nakarai A, Nanba S, Ohta S, Ogawa T, Kurome M, Ueki T, Nakagawa M, Araki Y, Mizuno M. Dynamic computed tomography is useful for the diagnosis and colonoscopic treatment of colonic diverticular bleeding (in Japanese) Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2011;108:223–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Obana T, Fujita N, Sugita R, Hirasawa D, Sugawara T, Harada Y, Oohira T, Maeda Y, Koike Y, Suzuki K, Yamagata T, Kusaka J, Masu K. Prospective evaluation of contrast-enhanced computed tomography for the detection of colonic diverticular bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1985–1990. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2629-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thoeni RF, Cello JP. CT imaging of colitis. Radiology. 2006;240:623–638. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2403050818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolff JH, Rubin A, Potter JD, Lattimore W, Resnick MB, Murphy BL, Moss SF. Clinical significance of colonoscopic findings associated with colonic thickening on computed tomography: is colonoscopy warranted when thickening is detected? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:472–475. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31804c7065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoon W, Jeong YY, Shin SS, Lim HS, Song SG, Jang NG, et al. Acute massive gastrointestinal bleeding: detection and localization with arterial phase multi-detector row helical CT. Radiology. 2006;239:160–167. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2383050175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakatsu S, Yasuda H, Maehata T, Nomoto M, Ohinata N, Hosoya K, Ishigooka S, Ozawa S, Ikeda Y, Sato Y, Suzuki M, Kiyokawa H, Yamamoto H, Itoh F. Urgent computed tomography for determining the optimal timing of colonoscopy in patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Intern Med. 2015;54:553–558. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hjern F, Jonas E, Holmström B, Josephson T, Mellgren A, Johansson C. CT colonography versus colonoscopy in the follow-up of patients after diverticulitis - a prospective, comparative study. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:645–650. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheffel H, Pfammatter T, Wildi S, Bauerfeind P, Marincek B, Alkadhi H. Acute gastrointestinal bleeding: detection of source and etiology with multi-detector-row CT. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:1555–1565. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0514-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loffroy R, Cercueil JP, Guiu B, Krausé D. Detection and localization of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding prior to therapeutic endovascular embolization: a challenge! Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:3108–3109. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.513. author reply 3109–3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jairath V, Hearnshaw S, Brunskill SJ, Doree C, Hopewell S, Hyde C, Travis S, Murphy MF. Red cell transfusion for the management of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;9:CD006613. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006613.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Villanueva C, Colomo A, Bosch A. Transfusion for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1362–1363. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1301256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jairath V, Kahan BC, Stanworth SJ, Logan RF, Hearnshaw SA, Travis SP, Palmer KR, Murphy MF. Prevalence, management, and outcomes of patients with coagulopathy after acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the United Kingdom. Transfusion. 2013;53:1069–1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolf AT, Wasan SK, Saltzman JR. Impact of anticoagulation on rebleeding following endoscopic therapy for nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:290–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siegal DM. Managing target-specific oral anticoagulant associated bleeding including an update on pharmacological reversal agents. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015;39:395–402. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holcomb JB, Tilley BC, Baraniuk S, Fox EE, Wade CE, Podbielski JM, et al. PROPPR Study Group Transfusion of plasma, platelets, and red blood cells in a 1: 1: 1 versus a 1: 1: 2 ratio and mortality in patients with severe trauma: the PROPPR randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:471–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baron TH, Kamath PS, McBane RD. New anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents: a primer for the gastroenterologist. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Acosta RD, Abraham NS, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Early DS, Eloubeidi MA, et al. The management of antithrombotic agents for patients undergoing GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Niikura R, Nagata N, Aoki T, et al. Predictors for identification of stigmata of recent hemorrhage on colonic diverticula in lower gastrointestinal bleeding. J Clin Gastroentrol. 2015;49:e24–e30. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaltenbach T, Watson R, Shah J, Friedland S, Sato T, Shergill A, McQuaid K, Soetikno R. Colonoscopy with clipping is useful in the diagnosis and treatment of diverticular bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bloomfeld RS, Rockey DC, Shetzline MA. Endoscopic therapy of acute diverticular hemorrhage. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2367–2372. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kominami Y, Ohe H, Kobayashi S, Higashi R, Uchida D, Morimoto Y, Nakarai A, Numata N, Hirao K, Ogawa T, Ueki T, Nakagawa M, Araki Y, Mizuno M, Chayama K. Classification of the bleeding pattern in colonic diverticulum is useful to predict the risk of bleeding or re-bleeding after endoscopic treatment (in Japanese) Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2012;109:393–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Setoyama T, Ishii N, Fujita Y. Endoscopic band ligation (EBL) is superior to endoscopic clipping for the treatment of colonic diverticular hemorrhage. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3574–3578. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1760-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ishii N, Setoyama T, Deshpande GA, Omata F, Matsuda M, Suzuki S, Uemura M, Iizuka Y, Fukuda K, Suzuki K, Fujita Y. Endoscopic band ligation for colonic diverticular hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]