Abstract

Background:

Understanding important sources and pathways of exposure to common chemicals known or suspected to impact human health is critical to eliminate or reduce the exposure. This is particularly important in areas such as Puerto Rico, where residents have higher exposures to numerous chemicals, as well as higher rates of many adverse health outcomes, compared to the mainland US.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to assess distributions, time trends, and predictors of urinary triclocarban, phenol, and paraben biomarkers measured at multiple times during pregnancy among women living in Northern Puerto Rico.

Methods:

We recruited 1003 pregnant women between years 2010 and 2016 from prenatal clinics and collected urine samples and questionnaire data on personal care product use at up to three separate visits, between 16 to 28 weeks gestation. Urine samples were analyzed for triclocarban, seven phenols and four parabens: 2,4-dichlorophenol, 2,5-dichlorophenol, benzophenone-3, bisphenol A (BPA), bisphenol S (BPS), bisphenol F, triclosan, butylparaben, ethylparaben, methylparaben, and propylparaben.

Results:

Detectable phenol and paraben concentrations among pregnant women were prevalent and tended to be higher than levels measured in women of reproductive age from the general US population, especially triclocarban, which had a median concentration 30 times higher in Puerto Rico participants. A decreasing temporal trend was statistically significant for urine concentrations of BPA during the study period, while the BPA substitute BPS showed an increasing temporal trend. Significant and suggestively positive associations were found between biomarker concentrations with the products use in the past 48-h (soap, sunscreen, lotion, cosmetics). There was an increasing trend of triclocarban/triclosan concentrations with increased concentrations of triclocarban/triclosan listed as the active ingredient in the bar soap/liquid soap products reported being used.

Conclusion:

Our results suggest several potentially important exposure sources to triclocarban, phenols, and parabens in this population and can inform targeted approaches to reduce exposure.

Keywords: Human biomonitoring, Exposure assessment, Pregnancy, Endocrine disruptors, Antimicrobials, Personal care products

INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, a multitude of new synthetic chemicals such as environmental phenols, parabens, triclocarban and related compounds, some of which are known endocrine disrupting compounds, have been introduced by industrial progress. Chemicals such as bisphenol A (BPA), triclosan, benzophenone-3, and methylparaben can be found in a wide variety of commercial products including personal care products, plastics, packaged food and drinks, and pharmaceuticals (Calafat et al. 2015; Zoeller et al. 2012). Humans are ubiquitously exposed to these chemicals through the environment, food intake, and the use of products containing them, through inhalation, dermal contact and perinatal transmission (i.e., placenta, breast milk) (Heffernan et al. 2015; North and Halden 2013; Soni et al. 2001; vom Saal and Welshons 2014). In the United States, reports from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) showed that the majority of the U.S. population has detectable concentrations of a range of personal care product chemicals in their bodies (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2009).

Environmental phenols, parabens and triclocarban can disrupt endocrine function, induce oxidative stress, and cause other alterations that may result in reduced fetal or child growth, preterm birth, reproductive tract anomalies, neurodevelopmental delays, obesity, allergies/asthma, and other effects (Bukowska 2003; Diamanti-Kandarakis et al. 2009; Kang et al. 2013; Karpuzoglu et al. 2013; Kumar et al. 2009; Meeker 2012; Watkins et al. 2015).

There is growing evidence and concern that exposure to certain environmental chemicals may contribute to the recent rise in child developmental disorders (Braun et al. 2011b). There are particularly high rates for a number of developmental conditions in Puerto Rico, as well as elevated exposure to environmental contaminants. Previous research within the area suggests that pregnant women in Puerto Rico may have higher exposure to some phenols or their precursors, such as triclosan, benzophenone-3, and 2,5-dichlorophenol compared to women of reproductive age from the U.S. general population (Meeker et al. 2013). Compared to the U.S., Puerto Rico has higher rates of preterm birth, childhood obesity and asthma (Garza et al. 2011; Otero-Gonzalez and Garcia-Fragoso 2008; Rivera-Soto et al. 2010) as well as of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes in adults (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2012; Perez et al. 2008).

Bisphenol S (BPS) and bisphenol F (BPF) are common alternatives to BPA (Rochester and Bolden 2015). Their widespread use has resulted in detection in personal care products (Liao and Kannan 2014), food (Liao and Kannan 2013), indoor dust (Liao et al. 2012b), surface water and sediments (Fromme et al. 2002; Song et al. 2014; Yang et al. 2014). BPS and BPF have also been detected in human urine at concentrations and detection frequencies comparable to BPA (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2018; Liao et al. 2012a; Vela-Soria et al. 2014; Zhou et al. 2014). In vivo and in vitro studies have indicated that BPS and BPF have similar hormonal activity as BPA (Molina-Molina et al. 2013; Owens and Ashby 2002; Stroheker et al. 2003; Vinas and Watson 2013) and have endocrine-disrupting effects (Ji et al. 2013; Naderi et al. 2014), therefore, they may pose similar potential health hazards as BPA. Although not a phenol, triclocarban, like triclosan, is used as a preservative and antiseptic agent primarily added to pharmaceutical and personal care products and has been detected in a wide variety of matrices worldwide. Triclocarban and triclosan are environmentally persistent endocrine disruptors that bioaccumulate in the aquatic organisms (Coogan and La Point 2008; Meador et al. 2016) and are associated with reproductive and developmental impacts (Chen et al. 2008; Johnson et al. 2016; Kumar et al. 2009).

In light of potential impacts of phenol and parabens on human health, studies characterizing exposure trends and sources are needed to inform effective strategies to reduce exposure, especially among pregnant women and children. In a previous preliminary study, we reported the distribution, variability, and predictors (personal care product use) of urinary concentrations of select phenols and parabens among the first 105 participants in our study of pregnant women in Puerto Rico (Meeker et al. 2013). The detection of these biomarkers in urine samples from Puerto Rican pregnant women suggests that exposure to phenol and paraben is highly prevalent in this population. We also reported positive associations between biomarker concentrations with few self-reported use of personal care products, such as liquid soap (triclosan), sunscreen (benzophenone-3), lotion (benzophenone-3 and parabens), and cosmetics (parabens). The present analysis greatly expands the sample size, providing more statistical power to detect associations, includes additional chemicals of concern (BPS, BPF, and triclocarban), and spans several years which enables the exploration of time trends. The aims of the present expanded study were to conduct a much more robust follow-up to our previous analysis of distributions, variability, and predictors of urinary concentrations of biomarkers of triclocarban, environmental phenols and parabens measured at multiple times during pregnancy among women living in Northern Puerto Rico.

METHODS

2.1. Study population

This study used data collected from pregnant women participating in the “Puerto Rico Testsite for Exploring Contamination Threats (PROTECT)” project. This prospective birth cohort was started in 2010 in the Northern Karst Region of Puerto Rico. The mission of PROTECT is to evaluate the influence of the exposure to selected environmental toxicants on the risk of preterm delivery and other adverse birth outcomes.

Study participants were recruited at seven prenatal clinics and hospitals throughout Northern Puerto Rico during 2010–2016 at approximately 14 ± 2 weeks of gestation. The present analysis reflects the 1,003 women in the study to date, which is an expansion of a previous preliminary analysis that included first 105 participants recruited into the study who had urinary biomarker data as of June 2012 (Meeker et al. 2013). All women were between the ages of 18 to 40 years. Details on the recruitment and inclusion criteria have been described previously (Cantonwine et al. 2014; Meeker et al. 2013). Spot urine was collected from women at three separate study visits (18 ± 2 weeks, 22 ± 2 weeks, and 26 ± 2 weeks of gestation).

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics and Research Committees of the University of Puerto Rico and participating clinics, the University of Michigan School of Public Health, and Northeastern University. The involvement of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) laboratory was determined not to constitute engagement in human subject research. The study was described in detail to all participants, and informed consent was obtained prior to study enrollment.

2.2. Measurement of Phenols and Parabens in Urine.

Urine samples were collected in polypropylene containers, divided into aliquots, and frozen at − 80°C until shipped overnight to the CDC for analysis. All urine samples were analyzed for triclocarban, seven phenols: BPA, BPS, BPF, 2,4-dichlorophenol, 2,5-dichlorophenol, benzophenone-3, triclosan, and four parabens: butylparaben, ethylparaben, methylparaben, propylparaben by online solid-phase extraction-high-performance liquid chromatography-isotope dilution tandem mass spectrometry (Watkins et al. 2015; Ye et al. 2005; Ye et al. 2006).

Biomarker concentrations below the limit of detection (Marszalek and Lodish) were replaced by LOD/ √2 (Hornung and Reed 1990). For select analyses, biomarker concentration values were corrected for urinary SG using the following equation: Pc = P[(SGp − 1)/(SGi − 1)] where Pc is the SG corrected biomarker concentration (μg/L), P is the measured biomarker concentration, SGp is the median urinary specific gravity (1.019), and SGi is the individual’s urinary specific gravity.

2.3. Questionnaire

The product use questionnaire, which was adapted from questionnaires used in other studies of adults (Duty et al., 2005; Meeker et al., 2013), was developed to capture information on potential exposure sources to which the pregnant women may have been in contact. The questionnaire was administered by a study nurse to collect demographic information as well as data on self-reported product use. The personal care product use section contained yes/no questions about the use of different products in the 48-h preceding urine sample collection, in addition to questions on the usual frequency of using these personal care products (not at all, <once/month, 1–3 times/month, once/week, few times/week, every day). The questionnaire asked about the use of the following personal care products: bar soap, cologne/perfume, colored cosmetics, conditioner, deodorant, fingernail polish, hair cream, hairspray/ hair gel, laundry products, liquid soap, lotion, mouthwash, other hair products, shampoo, and shaving cream. Following each yes/no question regarding the use of personal care product, the participants were also asked to report the specific brand of the product.

2.4. Statistical Methods

Distribution of urinary biomarkers (geometric means and selected percentiles) were calculated and compared to the concentrations measured NHANES (2009–2010, 2011–2012, 2013–2014) among women aged between 18 and 40 years (n=1185). The relationships between the various biomarkers were assessed by calculating Spearman rank correlations. To test whether there were differences in geometric mean biomarker concentrations between study visits (i.e., time points in gestation), linear mixed effect models were used which account for repeated measurements from individuals. We assessed the proportion of variance attributed to between-person variability across the three-time points in pregnancy using intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) and their 95% confidence intervals (Hankinson et al. 1995). ICC, ranging between 0 (no reproducibility) and 1 (perfect reproducibility), is interpreted as reflecting a poor degree of reliability when below 0.40, a moderate to good reliability when ranging between 0.40 and 0.75, and an excellent reliability when above 0.75 (Rosner 2015).

Next, to examine the changes in urinary biomarker concentrations over time among the study population, tests of linear trend across increasing visit-years were conducted by modeling the geometric mean of each biomarker and visit-year as a continuous variable and assessing significance using the Wald test.

We examined the association between urinary biomarker concentrations and categories of demographic variables (maternal age, maternal education, marital status, household income, parity, and pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI)), as well as with 48-h recall of the use of different products (yes/no questions mentioned above). With compound symmetry covariance structure, we used linear mixed effects models to account for the intra-individual correlation and variation of repeated measures over time. SG-corrected urinary biomarker concentrations were log-transformed and modeled as the dependent variable, with separate models for each demographic and product use variable. Data were analyzed using R version 3.2.2 and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Finally, based on the associations between product use and urine biomarker concentrations, we examined frequencies of the active ingredient (percentage if available) in different brands of bar soap and liquid soap use reported in the 48-h recall questionnaire in relation to triclosan and triclocarban concentrations among soap users. We searched the active ingredient and ingredient content level of the most commonly reported soap brands by women in the study, using the Environmental Working Group (EWG) 5s Skin Deep Cosmetic Database which contains 72,454 products (Environmental Working Group), the U.S. National Library of Medicine Household Products Database (National Library Of Medicine 2010), and web-based search engines (i.e., Google). For brands containing triclocarban or triclosan, we presented triclosan and triclocarban distribution corresponding to the specific soap brand users in comparison to those who did not report any soap use in the recall.

RESULTS

Demographics

Analysis was conducted for both unadjusted and SG-corrected biomarker concentrations on a total of 2,166 urine samples from 1,003 women, and results were highly consistent between the two approaches. 152 samples had no data on SG. The uncorrected results also remained the same when we excluded the 152 samples without available SG data. Demographic characteristics of the women in our study are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 26.6 years and nearly all women were non-smokers during pregnancy. Most women in our study had an education above high school and were employed, married or in a domestic partnership.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of n = 1003 Pregnant Women from Puerto Rico (2010– 2016)

| variable | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| maternal age | 26.6(5.5) |

| # pregnancies | 1.9 (1.0) |

| parity (# live births) | 0.7 (0.8) |

| characteristic | category | count (percent) |

|---|---|---|

| maternal education | <high school | 80(8.3%) |

| high school/equivalent | 129(13.4%) | |

| college/technical school | 757(78.4%) | |

| household income | <$20,000 | 291(29%) |

| ≥$20,000 to <$40,000 | 189(18.8%) | |

| ≥$40,000 | 155(15.5%) | |

| marital status | single | 201(20.7%) |

| married or living together | 768(79.3%) | |

| prepregnancy BMI (kg m−2) | ≤25 | 351(53%) |

| >25 to ≤30 | 200(30.2%) | |

| >30 | 111(16.8%) | |

| smoke during pregnancy | yes | 9(0.9%) |

| no | 739(73.7%) | |

| employment | unemployed | 378(37.7%) |

| employed | 585(58.3%) |

GM and Percentiles

Distributions of urinary biomarker concentrations among women in our study and distributions among women 18 to 40 years old from the NHANES 2009–10, 2011–12 and 2013–14 are presented in Table 2. BPA, benzophenone-3, both dichlorophenols, methylparaben, and propylparaben were detected in between 95% and 100% of samples from the PROTECT cohort. Triclocarban and triclosan were detected in 93% and 87% of samples, respectively, while BPS was detected in 90%, butylparaben was detected in 55%, and BPF was in 41% of the samples. Women in our study had higher geometric mean concentrations of 2,4-dichlorophenol, 2,5-dichlorophenol, BPA, butylparaben, triclocarban, and triclosan, compared with NHANES women. PROTECT women had a median concentration of triclocarban that was 30 times greater than NHANES. Median concentrations of butylparaben, triclosan, and 2,5-dichlorophenol among Puerto Rico women were 2-,2- and 4-fold greater, respectively, compared to women in NHANES. For 2,4-dichlorophenol and BPA median concentrations were similar in the two cohorts, but geometric mean concentrations were higher among PROTECT women. Distribution of benzophenone-3 and BPS were similar between the two populations, while the remaining parabens (ethylparaben, methylparaben, propylparaben) and BPF were lower among women in this study compared to NHANES. There was a moderate to strong correlation between 2,4-dichlorophenol and 2,5-dichlorophenol (Spearman r=0.65), between 2,4-dichlorophenol and triclosan (Spearman r=0.46), and between the four parabens, particularly between methylparaben and propylparaben (r = 0.78). There were also weak to moderate (r = 0.25 to 0.4) but statistically significant correlations between benzophenone-3 and the parabens (SI Table S1).

Table 2.

Urinary Biomarker Concentrations (ng/mL) in n = 1005 Pregnant Women from Puerto Ricoa in 2010– 2016 and Comparison with U.S. Population-Based Samples of Women Ages 18– 40 from NHANES.b,c

| Cohort | LOD | % >LOD | GM | GSD | 25% | 50% | 75% | 95% | P valued | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,4-dichlorophenol | PROTECT | 0.1 | 97.2 | 1.1 | 3.2 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 10.6 | <0.01** |

| NHANES | 0.1 | 95.9 | 0.8 | 4.0 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 9.6 | ||

| 2,5-dichlorophenol | PROTECT | 0.1 | 99.9 | 13.5 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 9.6 | 28.9 | 387.2 | <0.01** |

| NHANES | 0.1 | 98.0 | 3.9 | 8.7 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 10.8 | 256.4 | ||

| Benzophenone-3 | PROTECT | 0.4 | 99.7 | 41.6 | 6.5 | 11.2 | 27.3 | 119.8 | 1585.9 | 0.08 |

| NHANES | 0.4 | 99.2 | 36.6 | 8.3 | 8.1 | 25.9 | 128.0 | 2337.8 | ||

| BPA | PROTECT | 0.2–0.4 | 98.7 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 8.8 | <0.01** |

| NHANES | 0.2–0.4 | 92.8 | 1.7 | 3.1 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 3.5 | 10.2 | ||

| BPF | PROTECT | 0.2 | 41.1 | 0.3 | 2.9 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 2.1 | <0.01** |

| NHANES | 0.2 | 67.2 | 0.5 | 4.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 8.8 | ||

| BPS | PROTECT | 0.1 | 89.8 | 0.5 | 3.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 3.5 | 0.58 |

| NHANES | 0.1 | 88.8 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 4.0 | ||

| Triclosan | PROTECT | 1.7–2.3 | 86.6 | 22.7 | 8.6 | 3.6 | 15.4 | 149.3 | 867.1 | <0.01** |

| NHANES | 1.7–2.3 | 78.1 | 12.4 | 6.6 | 2.7 | 8.4 | 40.0 | 485.0 | ||

| Triclocarban | PROTECT | 0.1 | 93.1 | 3.8 | 10.3 | 0.6 | 2.9 | 31.4 | 144.0 | <0.01** |

| NHANES | 0.1 | 43.0 | 0.2 | 4.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 4.1 | ||

| Methylparaben | PROTECT | 1.0 | 99.4 | 78.2 | 5.0 | 25.7 | 92.8 | 245.4 | 871.1 | <0.01** |

| NHANES | 1.0 | 99.7 | 108.3 | 5.4 | 34.0 | 121.5 | 380.2 | 1387.0 | ||

| Ethylparaben | PROTECT | 1.0 | 55.4 | 2.8 | 6.6 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 8.9 | 111.3 | <0.01** |

| NHANES | 1.0 | 63.2 | 4.1 | 6.5 | 0.7 | 2.5 | 15.7 | 159.9 | ||

| Propylparaben | PROTECT | 0.1 | 99.0 | 15.4 | 7.3 | 3.3 | 17.8 | 75.4 | 278.8 | <0.01** |

| NHANES | 0.2 | 98.7 | 19.3 | 8.0 | 4.7 | 24.1 | 94.7 | 402.7 | ||

| Butylparaben | PROTECT | 0.1 | 55.1 | 0.5 | 7.5 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1.8 | 27.1 | 0.05 |

| NHANES | 0.2 | 51.8 | 0.4 | 6.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 15.0 |

Includes biomarker concentrations for up to 3 repeated samples per woman (n = 2,166 samples).

Females 18–40 years of age; n = 1185 for biomarkers measured in 2009–2010, 2011–2012, and 2013–2014 NHANES

NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; LOD, limit of detection; GM, geometric mean, GSD, geometric standard deviation

P value for two sample t-test comparing geometric mean of chemical concentration in two cohorts

P <0.01

Between Visit Comparison

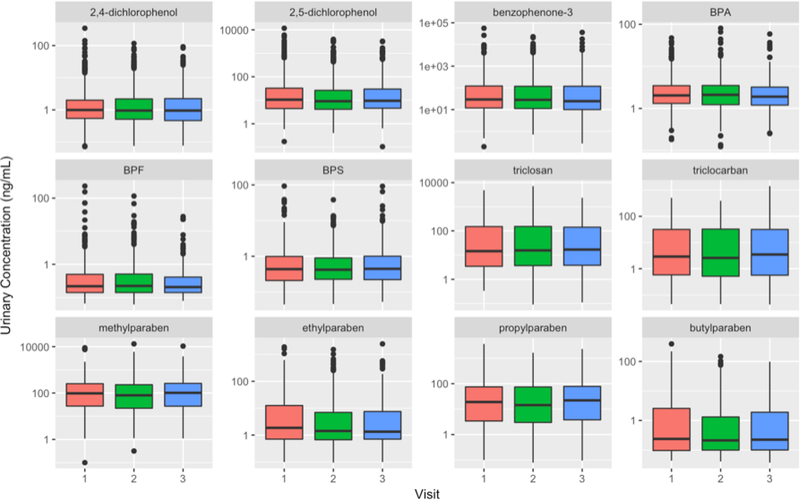

Box plot in Figure 1 shows the comparisons of the biomarker concentration distributions between study visits. Statistically significant differences were observed between SG- adjusted concentrations at the three visits for the biomarkers 2,5-dichlorophenol (p=0.02), BPA (p<0.01), butylparaben (p=0.02), and ethylparaben (p=0.01), where the concentration at first visit was higher than at later visits. For 2,4-dichlorophenol and benzophenone-3, geometric mean concentrations at the three visits were statistically different (p<0.05) before correcting for specific gravity (the first visit had the highest concentration), but after correcting for specific gravity there was no difference (SI Table S2). ICCs of unadjusted and SG-adjusted biomarker were presented in Table 3. Reproducibility varied widely between biomarkers and ranged from weak (BPS=0.02) to good. A moderate to good reproducibility was observed for all four parabens, triclocarban, triclosan, benzophenone-3, and butylparaben, with ICC ranging from 0.54 to 0.69, after correcting for specific gravity. On the other hand, 2,4-dichlorophenol, 2,5-dichlorophenol, BPA, BPS, and methylparaben presented a poor degree of reliability with low ICC (0.02–0.29), while ethylparaben was intermediate (0.40).

Figure 1.

Boxplots comparing SG-adjusted concentrations of urinary biomarkers across study visits. Visit 1 (18 ± 2 weeks gestation), Visit 2 (22 ± 2 weeks), Visit 3 (26 ± 2 weeks).

Table 3.

Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICCs) and 95% Confidence for ln-Transformed Urinary Concentrations of Biomarkers

| unadjusted | SG_adjusteda | |

|---|---|---|

| urinary biomarker | ICC (95% CI) | ICC (95% CI) |

| 2,4-dichlorophenol | 0.19(0.15,0.24) | 0.2 (0.21,0.3) |

| 2,5-dichlorophenol | 0.22(0.18,0.27) | 0.29(0.25,0.34) |

| Benzophenone-3 | 0.53(0.49,0.57) | 0.54(0.5,0.57) |

| BPA | 0.12(0.08,0.19) | 0.09(0.05,0.16) |

| BPS | 0.03(0.01,0.14) | 0.02(0,0.16) |

| Triclosan | 0.52(0.48,0.57) | 0.59(0.55,0.63) |

| Triclocarban | 0.72(0.68,0.76) | 0.69(0.64,0.73) |

| Methylparaben | 0.23(0.18,0.3) | 0.16(0.11,0.21) |

| Ethylparaben | 0.29(0.24,0.34) | 0.4(0.36,0.45) |

| Propylparaben | 0.43(0.38,0.49) | 0.35(0.3,0.41) |

| Butylparaben | 0.55(0.49,0.6) | 0.57(0.51,0.62) |

specific gravity adjusted concentration

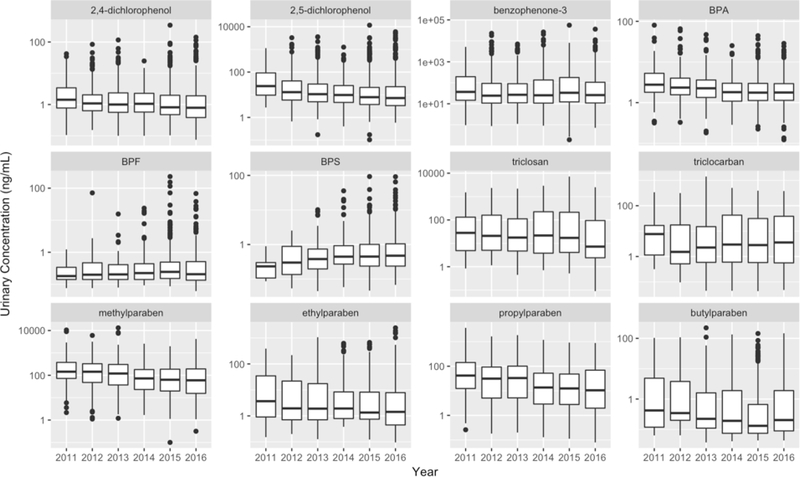

Distribution by Year

Figure 2 shows urinary biomarker concentration distributions in the study population stratified by year. For all biomarkers, urinary concentrations were lower in participants from the later year cycle compared to those from the earlier year cycle (P for trend<0.01), with the exception of BPS (P for trend<0.01) which has an increasing trend, and benzophenone-3 (P for trend=0.95), BPF (P for trend=0.54) and triclocarban (P for trend=0.15) which stayed constant.

Figure 2.

Distribution of urinary biomarker concentrations (ng/mL) among 1,003 pregnant women in Puerto Rico over study years (2010–2016)

Demographics and Biomarkers

Associations between urinary biomarker concentrations and demographic variable categories are reported in supplemental information (Table S3). There were trends for increasing concentration of benzophenone-3, triclosan and four parabens with increasing age categories, where BPA and triclocarban concentration had a decreasing trend with increasing age categories. Benzophenone-3, triclosan, and the four paraben concentrations were higher among women with >12 years of education. There were decreasing trends in triclocarban concentrations and education categories. 2,5-Dichlorophenol, methylparaben, and triclocarban concentrations were associated with marital status, where concentrations among women who were either married or in a domestic partnership were significantly lower (p = 0.04, 0.04 and p =0.05, respectively) compared to women who reported their marital status as single. There were trends for increasing concentrations of benzophenone-3, butylparaben, BPF, ethylparaben with increasing income categories, whereas 2,5-dichlorophenol and triclocarban concentrations had decreasing trends in relation to increasing income categories. There was an increasing trend between triclocarban concentration and pre-pregnancy BMI and a decreasing trend between butylparaben concentrations and increased parity. Finally, concentrations of benzophenone-3, triclosan and three parabens (butylparaben, methylparaben, propylparaben) were lower, and triclocarban concentrations higher, among women who were not currently employed.

Product Use and Biomarkers

Urinary biomarker concentrations in relation to self-reported product use are presented in Table 4. The geometric mean concentration of benzophenone-3, triclosan, and all parabens were 2- to 3-fold higher among women who reported recent use of hand or body lotion compared to women who did not. Similar associations (2 −3 fold difference) between benzophenone-3 and all paraben biomarker concentrations and self-reported cosmetic use were also observed. Use of sunscreen was associated with 5-fold higher geometric mean concentrations of benzophenone-3. Triclosan and triclocarban geometric mean concentrations were 2- and 4-fold higher among women reporting the use of liquid soap and bar soap, respectively, compared to those who did not. Use of perfume and nail polish were associated with significant increase in butylparaben. There were no associations between any of the questionnaire variables and 2,5-dichlorophenol, BPA, BPF or BPS concentrations. We also found an unexpected decrease in butylparaben concentration associated with the use of fabric softener, detergent and paint, and 2,4-dichlorophenol concentration was lower among women who reported recent use of pet grooming product compared to women who did not.

Table 4.

Frequencies of Product Use Reported in the 48-h Recall Questionnaire and Selecteda SG-Adjusted Geometric Mean Concentrations of Chemical Biomarkers (ng/mL) Associated with Self-Reported Use or Nonuse

| Use | n=1006b | N=2166c | 2,4-dichloro phenol | Benzop henone-3 | Triclo san | Tricloc arban | Methyl paraben | Ethyl paraben | Propyl paraben | Butyl paraben | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cleaning products | |||||||||||

| laundry detergent | yes | 539 | 1186 | 1.2 | 39.0 | 21.9 | 4.2 | 78.1 | 3.0 | 15.3 | 0.4 |

| no | 361 | 790 | 1.1 | 45.5 | 24.8 | 3.5 | 79.0 | 2.5 | 15.8 | 0.6 | |

| p-valued | 0.36 | 0.52 | 0.76 | 0.18 | 0.87 | 0.70 | 0.62 | 0.02* | |||

| general cleaner | yes | 505 | 1174 | 1.2 | 41.0 | 21.1 | 4.0 | 82.1 | 3.0 | 17.0 | 0.5 |

| no | 392 | 800 | 1.1 | 42.0 | 26.2 | 3.7 | 73.5 | 2.5 | 13.6 | 0.5 | |

| p-valued | 0.88 | 0.99 | 0.26 | 0.65 | 0.83 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.51 | |||

| fabric softener | yes | 453 | 985 | 1.2 | 37.8 | 22.1 | 4.0 | 77.7 | 2.9 | 15.8 | 0.4 |

| no | 447 | 992 | 1.1 | 45.5 | 23.9 | 3.8 | 79.3 | 2.7 | 15.3 | 0.5 | |

| p-valued | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.79 | 0.35 | 0.98 | 0.75 | 0.89 | 0.01* | |||

| creams and lotions | |||||||||||

| Hand/body lotion | yes | 687 | 1569 | 1.2 | 47.0 | 24.3 | 3.5 | 91.8 | 3.0 | 18.6 | 0.5 |

| no | 212 | 404 | 1.1 | 25.3 | 18.8 | 5.5 | 43.0 | 2.0 | 7.7 | 0.3 | |

| p-valued | 0.40 | <0.01** | 0.02* | 0.27 | <0.01** | <0.01** | <0.01** | 0.01* | |||

| shaving cream | yes | 73 | 152 | 1.1 | 64.0 | 26.5 | 3.9 | 74.8 | 4.6 | 16.2 | 0.5 |

| no | 827 | 1824 | 1.2 | 40.1 | 22.8 | 3.9 | 78.8 | 2.7 | 15.4 | 0.5 | |

| p-valued | 0.95 | 0.34 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.44 | 0.13 | 0.72 | 0.56 | |||

| sunscreen | yes | 30 | 64 | 1.3 | 187.2 | 19.4 | 1.8 | 130.0 | 4.7 | 24.9 | 0.7 |

| no | 869 | 1910 | 1.1 | 39.5 | 23.2 | 4.0 | 77.4 | 2.8 | 15.3 | 0.5 | |

| p-valued | 0.65 | <0.01 ** | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.42 | 0.29 | 0.73 | 0.72 | |||

| toiletries and cosmetics | |||||||||||

| perfume/cologne | yes | 743 | 1651 | 1.2 | 43.2 | 22.0 | 3.9 | 81.3 | 2.9 | 16.3 | 0.5 |

| no | 156 | 324 | 1.1 | 33.9 | 29.0 | 3.8 | 66.0 | 2.1 | 12.2 | 0.3 | |

| p-valued | 0.55 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.65 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.21 | 0.01** | |||

| cosmetic | yes | 680 | 1468 | 1.2 | 51.2 | 23.8 | 3.4 | 100.9 | 3.6 | 22.4 | 0.7 |

| no | 220 | 508 | 1.0 | 22.5 | 20.7 | 5.7 | 38.2 | 1.3 | 5.4 | 0.2 | |

| p-valued | 0.49 | <0.01** | 0.59 | 0.87 | <0.01** | <0.01** | <0.01** | <0.01** | |||

| liquid soap | yes | 779 | 1766 | 1.1 | 42.0 | 23.5 | 3.8 | 78.6 | 2.8 | 15.6 | 0.5 |

| no | 120 | 210 | 1.2 | 37.6 | 19.4 | 4.3 | 77.4 | 2.8 | 14.7 | 0.5 | |

| p-valued | 0.38 | 0.85 | 0.04* | 0.54 | 0.36 | 0.69 | 0.37 | 0.75 | |||

| bar soap | yes | 825 | 1808 | 1.2 | 39.7 | 22.4 | 4.4 | 76.8 | 2.8 | 15.3 | 0.5 |

| no | 74 | 167 | 1.1 | 67.7 | 31.0 | 1.0 | 97.4 | 2.9 | 18.1 | 0.6 | |

| p-valued | 0.83 | 0.09· | 0.14 | <0.01** | 0.25 | 0.88 | 0.76 | 0.08· | |||

| mouth wash | yes | 410 | 977 | 1.2 | 46.4 | 23.1 | 3.5 | 82.4 | 2.8 | 15.9 | 0.5 |

| no | 490 | 1000 | 1.1 | 37.2 | 22.9 | 4.3 | 74.9 | 2.8 | 15.2 | 0.5 | |

| p-valued | 0.63 | 0.21 | 0.54 | 0.43 | 0.74 | 0.92 | 0.65 | 0.86 | |||

| hair and nail products | |||||||||||

| hairspray | yes | 279 | 609 | 1.2 | 40.4 | 25.0 | 4.5 | 83.8 | 2.9 | 15.3 | 0.5 |

| no | 617 | 1363 | 1.1 | 42.0 | 22.1 | 3.7 | 76.5 | 2.7 | 15.6 | 0.5 | |

| p-valued | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.05· | 0.53 | 0.63 | 0.72 | 0.86 | |||

| shampoo | yes | 640 | 1398 | 1.2 | 41.3 | 23.5 | 3.6 | 82.4 | 3.0 | 16.4 | 0.5 |

| no | 260 | 578 | 1.1 | 42.1 | 21.9 | 4.7 | 70.1 | 2.4 | 13.5 | 0.5 | |

| p-valued | 0.22 | 0.54 | 0.45 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.23 | 0.53 | 0.37 | |||

| conditioner | yes | 625 | 1369 | 1.2 | 41.0 | 23.9 | 3.6 | 81.6 | 2.9 | 16.1 | 0.5 |

| no | 274 | 606 | 1.1 | 42.7 | 21.1 | 4.6 | 72.2 | 2.5 | 14.3 | 0.5 | |

| p-valued | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.25 | 0.55 | 0.90 | 0.62 | 0.88 | 0.26 | |||

| other hair product | yes | 130 | 136 | 1.3 | 49.3 | 24.3 | 3.2 | 110.0 | 5.1 | 26.1 | 0.7 |

| no | 586 | 605 | 1.2 | 41.6 | 22.5 | 3.9 | 74.7 | 3.0 | 15.0 | 0.5 | |

| p-valued | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.64 | 0.02* | 0.02* | 0.01* | 0.07 | |||

| nail polish | yes | 245 | 521 | 1.1 | 42.6 | 18.4 | 4.3 | 89.7 | 3.9 | 18.3 | 0.6 |

| no | 655 | 1454 | 1.2 | 41.2 | 24.9 | 3.8 | 75.0 | 2.5 | 14.6 | 0.5 | |

| p-valued | 0.07 | 0.52 | 0.12 | 0.46 | 0.29 | <0.01** | 0.21 | 0.01* | |||

| vinyl products | |||||||||||

| vinyl curtain | yes | 569 | 1260 | 1.2 | 42.0 | 22.1 | 4.1 | 81.6 | 2.8 | 15.7 | 0.5 |

| no | 331 | 717 | 1.1 | 40.7 | 24.8 | 3.5 | 73.4 | 2.7 | 15.2 | 0.5 | |

| p-valued | 0.47 | 0.93 | 0.11 | 0.76 | 0.61 | 0.71 | 0.86 | 0.35 | |||

| Vinyl gloves | yes | 88 | 172 | 1.2 | 54.5 | 31.8 | 3.2 | 82.7 | 3.0 | 16.9 | 0.5 |

| no | 812 | 1805 | 1.1 | 40.4 | 22.3 | 4.0 | 78.1 | 2.8 | 15.4 | 0.5 | |

| p-valued | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.46 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.38 | 0.29 | 0.86 | |||

| furniture and care, pet | |||||||||||

| paint | yes | 23 | 68 | 1.4 | 30.3 | 40.9 | 4.1 | 90.5 | 1.9 | 14.3 | 0.4 |

| no | 877 | 1909 | 1.1 | 42.0 | 22.6 | 3.9 | 78.1 | 2.8 | 15.6 | 0.5 | |

| p-valued | 0.71 | 0.51 | 0.06 | 0.59 | 0.97 | 0.08 | 0.48 | 0.03* | |||

| pesticide use | yes | 51 | 131 | 1.3 | 40.9 | 29.5 | 3.0 | 93.9 | 3.7 | 21.6 | 0.5 |

| no | 849 | 1846 | 1.1 | 41.5 | 22.6 | 3.9 | 77.5 | 2.7 | 15.1 | 0.5 | |

| p-valued | 0.24 | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.85 | 0.37 | 0.79 | 0.17 | 0.38 | |||

| pet grooming product | yes | 38 | 74 | 1.0 | 48.2 | 21.0 | 3.6 | 65.5 | 3.0 | 17.2 | 0.7 |

| no | 862 | 1903 | 1.2 | 41.3 | 23.1 | 3.9 | 79.0 | 2.8 | 15.4 | 0.5 | |

| p-valued | 0.04* | 0.51 | 0.33 | 0.92 | 0.06. | 0.68 | 0.90 | 0.43 | |||

results shown for associations with p-value ≤ 0.1.

n=1003 total number of participant.

N=2166 total number of total responses

p-values from linear mixed effects models accounting for within-person correlations

P from 0.1 to 0.05

P from 0.05 to 0.01

P <0.01

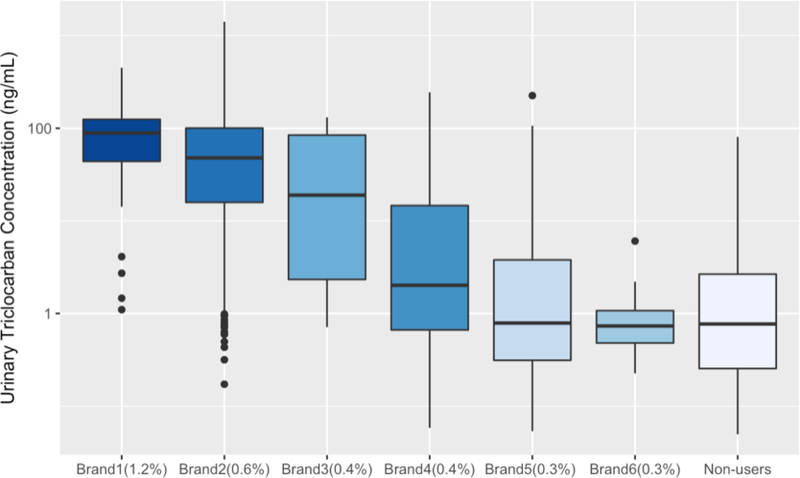

Soap Brands and triclocarban, triclosan

Self-reported use of several brands of bar soap and liquid soap in the 48h preceding urine sample collection and corresponding urinary triclocarban and triclosan concentrations are presented in Figure 3 and SI Figure 1, respectively. There is a decreasing trend of triclocarban concentration with decreasing active ingredient concentration (triclocarban) in the bar soaps. Geometric mean concentrations of triclocarban among women who reported recent use of triclocarban-containing brand 1 containing 1.2% triclocarban (from Figure 3 x-axes label) and brand 2 containing 0.6% triclocarban were 61.2 ng/mL and 34.3 ng/mL, and the concentrations were 64 and 36 times higher compared to women who did not report the use of bar soap, respectively. A similar but subtler trend was observed for triclosan concentration distribution among different brand liquid soap users and non-users (SI Figure S1). Geometric mean concentrations of triclosan among women who reported recent use of triclosan-containing brand 1 (triclosan 0.3%, urinary triclosan GM=66.7 ng/mL) and brand 2 (triclosan 0.15%, urinary triclosan GM=29.0 ng/mL) were 3.5 and 2 times higher compared to women who did not report the use of liquid soap, respectively.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Urinary Triclocarban Concentrations among Different Brands of Bar Soap User and Non-Users Self-reported in the 48-h Recall

DISCUSSION

GM and Percentiles

The main purpose of our study was to examine the distribution, variability, time trends, and predictors of urinary concentrations of triclocarban, and select phenols and parabens in repeated urine samples collected from pregnant women in Puerto Rico. We found that Puerto Rican pregnant women are widely exposed to these chemicals. Concentrations of a majority of biomarkers among this population were higher compared to women of similar age in the U.S. general population, especially triclocarban, which had a median concentration 30 times higher in PROTECT participants. Concentrations of benzophenone-3 and BPS were similar in the two populations. The biomarkers that were significantly lower in the PROTECT population when compared to the concentrations found in women of reproductive age from the 2009–2014 NHANES study were the remaining parabens (ethylparaben, methylparaben, propylparaben) and BPF.

As shown in Table 5, other pregnancy cohort studies from around the globe have also reported concentrations of these urinary biomarkers. Similar BPA concentrations have been reported among pregnant women in New York (Perera et al. 2012; Wolff et al. 2008), Ohio (Braun et al. 2011a), Mexico City (Cantonwine et al. 2010), Denmark (Tefre de Renzy-Martin et al. 2014), Germany (Kasper-Sonnenberg et al. 2012), Spain (Casas et al. 2011), France (Philippat et al. 2012; Vernet et al. 2017) and the Netherlands (Ye et al. 2008). Studies of BPF and BPS have been much more limited in number compared with BPA. The first study to report the occurrence of BPF and BPS in pregnant women urine was from the Netherlands, to which the median concentrations of BPF and BPS in our study were comparable (Philips et al. 2018).

Table 5.

Urinary triclocarban, phenol and paraben concentrations reported in the present study and previous studies among pregnant women.

| Reference | Country/Region | na | 2,4_diclorop henol | 2,5_diclorophe nol | Benzophenone-3 | BPA | BPF | BPS | Triclosan | Triclocarban | Methylparaben | Ethylparaben | Propylparaben | Butylparaben | Correctionb | GMc/Median | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present study | Puerto Rico | 2166 | 1.1 | 13.5 | 41.6 | 2.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 22.7 | 3.8 | 78.2 | 2.8 | 15.4 | 0.5 | SG | GM | ng/mL |

| Braun et al. 2011a | Ohio, US | 389 | 1.9 | Cr | GM | ug/g | |||||||||||

| Wolff et al. 2008 | New York, US | 367 | 2.1 | 53.0 | 7.5 | 1.3 | 11.0 | - | Median | ng/mL | |||||||

| Perera et al. 2012 | New York, US | 198 | 2.0 | SG | GM | ng/mL | |||||||||||

| Cantonwine et al. 2010 | Mexico City | 60 | 1.5 | SG | GM | ng/mL | |||||||||||

| Kasper-Sonnenberg et al. 2012 | Germany | 232 | 1.8 | Cr | GM | ug/g | |||||||||||

| Casas et al. 2011 | Spain | 120 | 1.1 | 16.5 | 3.4 | 2.2 | 6.1 | 191.0 | 8.8 | 29.8 | 2.4 | - | Median | ng/mL | |||

| Philippat et al. 2012 | France | 191 | 0.8 | 6.4 | 1.3 | 3.1 | 17.5 | 104.3 | 1.5 | 10.4 | 2.2 | - | Median | ng/mL | |||

| Vernet et al. 2017 | France | 587 | 1.0 | 9.8 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 29.3 | 118.0 | 4.5 | 16.1 | 1.9 | - | Median | ng/mL | |||

| Tefre de Renzy-Martin et al. 2014 | Denmark | 200 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 3.0 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 20.5 | 0.9 | Cr | Median | ug/g | ||||

| Frederiksen et al. 2014 | Denmark | 565 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 4.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 11.0 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 0.2 | - | GM | ng/mL | ||

| Myridakis et al. 2015 | Greece | 239 | 5.6 | 121.9 | 2.9 | Cr | Median | ug/g | |||||||||

| Ye et al. 2008 | Netherlands | 100 | 1.7 | Cr | GM | ug/g | |||||||||||

| Philips et al. 2018 | Netherlands | 1396 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 0.4 | - | Median | ng/mL | |||||||||

| Pycke et al. 2014 | New York | 181 | 7.2 | 0.2 | Cr | Median | ug/g | ||||||||||

| Kang et al. 2013 | Korea | 46 | 169.9 | 44.6 | 8.6 | <LOD | SG | Median | ng/mL | ||||||||

| Shirai et al. 2013 | Japan | 111 | 83.6 | 9.2 | 7.3 | 0.8 | SG | GM | ng/mL |

Sample Size

- no correction applied, SG corrected for specific gravity Cr corrected for creatinine

GM geometric mean

Geometric mean concentration of 2,4-Dichlorophenol (1.1 ng/mL) and 2,5-dichlorophenol (13.5 ng/mL)in our study were similar to recent findings in France (1.0 and 9.8 ng/mL, respectively) (Vernet et al. 2017), while the median concentrations of 2,5-dichlorophenol were higher in the Spain and New York (53 ng/mL) studies compared to this study. Median concentrations of triclosan and benzophenone-3 appeared to be higher in this Puerto Rico cohort compared to pregnant women in New York, Spain, and Denmark. Triclocarban concentration was much higher among pregnant women in our study (GM=3.8 ng/mL) compared to pregnant women in Denmark (Frederiksen et al. 2014; Tefre de Renzy-Martin et al. 2014) and New York (Pycke et al. 2014) where the geometric or median concentration in urine was 0.01, 0.02 and 0.17 ng/mL, respectively.

Urinary methylparaben concentrations in the present study were similar to pregnant women in France (Vernet et al. 2017) and Greece (Myridakis et al. 2015), but lower than those in Spain (Casas et al. 2011) and Korea (Kang et al. 2013), and higher than in Denmark (Tefre de Renzy-Martin et al. 2014), and Japan (Shirai et al. 2013). Urinary ethylparaben and proplyparaben concentrations in pregnant women in Puerto Rico, were comparable to those in Denmark, France, and Japan, whereas higher concentrations were reported among Korean and Spanish women. In contrast, urinary butylparaben concentrations were lower among women in Puerto Rico compared to those of other studies (Table 5).

Between Visit difference and ICCs

We found that the geometric mean concentration at first visit for 2,5-dichlorophenol, BPA, and butylparaben was statistically higher than later visits in our study. It is possible that these observations may be due to the differences in dilution caused by plasma volume expansion and metabolic changes in later visits, as maternal plasma volume expands 45% on average to provide for the greater circulatory needs of maternal organs during pregnancy (Gilbert 1990). However, if that were the primary explanation then we would expect to see similar trends for all exposure biomarkers measured in the study. This difference may also be attributable to changes in personal care product use. We conducted a trend test to determine whether self-reported product use changed over the three visits and did not observe a statistically significant declining trend in the use of any personal care product reported. Interestingly, there was an increasing trend in use of lotion and liquid soap during pregnancy among women in our cohort.

The knowledge about the degree to which biomarker concentrations from a single urine sample reflects an individual’s long-term exposure to these chemicals (or their precursors) is essential for conducting and interpreting epidemiologic studies of associations. The representability of a single sample is determined by the within-person variability of concentration over time. Increased measurement error of a single measurement can result from large within-person variability which can consequently lead to the attenuation of observed associations. When designing a new study (e.g., calculating effective sample size needed to be able to capture a certain difference and/or determining the measurement method), one should take into account within-person variability of concentrations of the biomarker of interest to avoid issues discussed above.

The half-lives of the biomarkers we measured are relatively short (e.g., cleared from the body within 24–48 hr). However, the ICCs for SG corrected biomarker concentrations in our study, based on three urine samples collected over several months, range from weak to good reproducibility, with the lowest ICC found for BPS (0.02) and the highest for triclocarban (0.69). Among studies that have reported individual variability in repeated measurements of urinary phenols concentrations, BPA has been investigated the most in different populations. The observed ICC for BPA measurements in our study (0.09) is in agreement with the studies which have reported similarly very low to moderate ICCs of around 0.04–0.43 (Braun et al. 2011a; Engel et al. 2014; Guidry et al. 2015; Lassen et al. 2013; Mahalingaiah et al. 2008; Nepomnaschy et al. 2009; Pollack et al. 2016; Reeves et al. 2014; Teitelbaum et al. 2008; Ye et al. 2011a), where higher ICCs correspond to studies with shorter time frame between repeated samples. Findings from many studies suggest that multiple measurements are needed to reflect long-term exposure to BPA rather than a single measurement. Only one study assessed between-week ICC for BPS measurements among pregnant women in France (ICC=0.33) which was higher than the estimate from our study (ICC=0.02) (Vernet et al. 2018). To our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify the reliability of BPF and triclocarban in urine samples from pregnant women.

Our estimates of temporal variability in 2,4-dichlorophenol (ICC=0.25), 2,5-dichlorophenol (ICC=0.29) were comparable to other studies (Engel et al. 2014; Pollack et al. 2016; Teitelbaum et al. 2008), except one study found high reproducibility for 2,4-dichlorophenol (ICC=0.6) and 2,5-dichlorophenol (ICC=0.61) among pregnant women in New York (Philippat et al. 2013). We reported moderate reproducibility for benzophenone-3 (ICC=0.54), similar to studies among pregnant women and children in the United States, Norway and Belgium (Dewalque et al. 2015; Guidry et al. 2015; Philippat et al. 2013; Teitelbaum et al. 2008), although two recent studies observed somewhat higher ICC for benzophenone-3 (ICC=0.67 and ICC=0.71 respectively) among U.S. and Danish adults (Lassen et al. 2013; Pollack et al. 2016). Children and pregnant women may, however, have different patterns of exposure and metabolism from those of non-pregnant adults, and the results may therefore not be directly comparable.

The ICC of 0.59 for triclosan indicated moderate reproducibility among urine samples collected across pregnancy. This result was comparable to that of recent studies among pregnant women in Norway (Bertelsen et al. 2014), Canada (Weiss et al. 2015), and New York (Philippat et al. 2013) who reported adjusted ICCs for triclosan of 0.49, 0.50 and 0.58 respectively. For parabens, low to moderate reproducibility over time was found in our study. Our results were comparable to previous estimates for ethylparaben, but lower than prior reports methylparaben and propylparaben, and higher than prior reports for butylparaben when compared to studies conducted on pregnant women in Boston, New York and Norway (Guidry et al. 2015; Philippat et al. 2013; Smith et al. 2012).

Temporal Trend in Biomarker Concentrations

We explored temporal patterns of biomarkers of exposure to triclocarban, phenols, and parabens in the study population from 2011 to 2016. Concerning adverse health effects of those chemicals, monitoring long-term trend could be a valuable approach for identifying factors associated with human exposure, identifying susceptible populations, and directing future research and/or legislative actions. A decreasing temporal trend was statistically significant for urine concentrations of BPA during the study period, while the BPA substitute BPS showed an increasing temporal trend. A similar declining trend for BPA has also been seen in the U.S. NHANES between 2003 and 2012 (LaKind and Naiman 2015) and among mothers in Sweden between 2009 and 2014 (Gyllenhammar et al. 2017). No statistically significant trends were seen for BPF, however, 59% of the samples had concentrations below LOD and the estimation of the temporal trend is therefore highly uncertain. Industries have begun to remove BPA from commercial products as a result of consumer concern, and since then chemicals such as BPS and BPF have been used as substitutes (Rochester and Bolden 2015). Our results showed that efforts to phase out production of BPA and the use of substitute chemicals may have resulted in a decreased exposure to BPA among our study population but increased the exposure to BPS at the same time. Studies have indicated that BPS and BPF have hormonal activity (Molina-Molina et al. 2013; Owens and Ashby 2002; Stroheker et al. 2003; Vinas and Watson 2013) and endocrine-disrupting effects (Ji et al. 2013; Naderi et al. 2014) similar to BPA, therefore, they could potentially pose similar health hazards as BPA.

Decreasing temporal trends were observed for both dichlorophenols, all parabens, and triclosan. A similar trend for triclosan was observed in the general U.S. population from 2003 to 2012 (Han et al. 2016) and in pregnant women from 2005 to 2010 (Mortensen et al. 2014). The declining trend is probably because of decreasing use of products containing triclosan due to increasing public awareness concerning the possible health impacts prior to recent FDA action on use of triclosan.

Product Use

Our findings on the positive associations between urinary biomarker concentrations and self-reported product use were overall consistent with the findings from previous studies. Use of sunscreen, hand/body lotion and cosmetics were associated with higher benzophenone-3 concentrations. Benzophenone-3 is a UV filter found mainly in sunscreens and cosmetics offering sun protection (Dodson et al. 2012; Gonzalez et al. 2006), which is consistent with our finding that self-reported sunscreen use was associated with the greatest increase for benzophenone-3 biomarker concentration in our study (difference=148 ng/mL). Many cosmetics and lotions may contain benzophenone-3 as they are claimed to have sun protecting properties. Parabens are commonly used preservatives and antibacterial agents in cosmetics and other personal care products (Guo and Kannan 2013; Shen et al. 2007; Soni et al. 2005). Higher paraben concentrations were found among women who reported using cosmetics and lotion which is in line with other recent studies (Braun et al. 2014; Fisher et al. 2017; Nassan et al. 2017; Philippat et al. 2015). Consistent with our findings, parabens were detected in a study that measured parabens in some of the same cosmetics and other personal care products (Dodson et al. 2012; Guo and Kannan 2013). We also found higher urinary concentrations of butylparaben in relation to self-reported perfume and nail polish use. Braun et al reported similar findings among pregnant women from a fertility clinic. However, studies that quantified chemicals in various personal care products reported that parabens are seldom found in perfume and nail polish (Dodson et al. 2012; Guo and Kannan 2013). It may be possible that these associations were due to confounding in that people who use perfume and nail polish more likely to use other products that do contain parabens.

Triclosan and Triclocarban

Higher triclosan and triclocarban concentrations were found among women who reported using liquid soap and bar soap use in the 48h preceding urine sample collection, respectively. This was as hypothesized because triclosan and triclocarban have been used as active ingredients in many antibacterial liquid hand/dish soap and bar hand soap, respectively, and have been also detected in conventional soap at slightly lower concentrations (Dodson et al. 2012; Perencevich et al. 2001). Women reporting the use of lotion also had a higher concentration of triclosan than among women who did not, and lotion is one of the primary exposure sources of triclosan along with soaps, toothpaste, and mouthwashes (Bhargava and Leonard 1996; Moss et al. 2000). One previous study in Sweden also showed that the triclosan concentrations in both plasma and milk were significantly higher in pregnant women who used triclosan-containing personal care products (Allmyr et al. 2006).

Dermal exposure from personal care products is believed to be the main route of human exposure to triclosan and triclocarban (Bhargava and Leonard 1996; Moss et al. 2000; Ye et al. 2011b), which suggests that the presence of triclosan and triclocarban in soap can lead to exposure in humans. According to U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), there is no evidence that the use of triclosan and triclocarban in antibacterial soaps improves consumer or patient health or prevents disease (Food and Drug Administration 2016). FDA issued a final rule in September 2016 which regulates the use of both chemicals in consumer antiseptic wash products due to insufficient data regarding their safety and effectiveness, and the potential for bacterial resistance or hormonal effects (Food and Drug Administration 2016). FDA first proposed the rule back in 2013, and since then manufacturers have started phasing out the use of triclosan and triclocarban in antibacterial washes. Based on our observation of significant relationships between soap use and biomarker concentrations of these chemicals, this suggests that the policies to remove these chemicals from soap could effectively reduce human exposure moving forward.

Considering the timeline of our study (2010〜2016), it is possible that at least some of the soap products used by women in Puerto Rico contained triclosan and triclocarban to some degree. Urinary concentrations of triclosan and triclocarban among pregnant women in our study were much higher than women enrolled in NHANES (triclocarban median concentration among PROTECT participants in 2011 and 2016 were 130- and 51-fold greater compared to NHANES cycle 2011–2012 and 2013–2014, respectively). We also found that there was an increasing trend of urinary triclocarban concentrations with increased concentrations of triclocarban listed as the active ingredient in the brands of bar soap products that were reported being used by study participants. A similar trend was also observed for triclosan urinary concentration across different liquid soap products in which triclosan listed as the active ingredient. These findings further reinforce that the use of products containing triclosan and triclocarban likely contributed to human exposure, and suggest that increased public awareness regarding the use of products containing chemicals like triclosan and triclocarban may be effective in reducing the magnitude of these exposures.

Strengths and Limitations

Utilizing a longitudinal repeated measures design, we described a detailed human study investigating exposures to environmental phenols and parabens, and trends and predictors of these exposures among pregnant women. A major advantage of this analysis is that the large sample size provided robust statistical power to assess the association between urinary biomarker concentrations and produce use in our cohort. Collection of multiple biomarker measurements in pregnant women also allowed women to in part serve as their own comparison for time-varying predictors of exposure biomarker concentrations. This study also had several limitations. We did not collect detailed information regarding the frequency of personal product use, amount of product used, and triclocarban, phenols, and parabens content from the products themselves. However, we analyzed the influence of variable levels of triclosan and triclocarban in products using publicly available brand information on the urinary biomarker concentrations. The lack of information on frequency and amount of product use may have attenuated our results toward the null due to non-differential measurement error. Lastly, our findings may not be generalizable to other populations, especially men or children since their personal care product use may be quite different compared to pregnant women.

CONCLUSION

Concentrations of triclocarban, phenols, and parabens among pregnant women living in Puerto Rico tended to be higher than or similar to those in women of reproductive age from the general U.S. population. This study also suggests that the pregnant women’s exposures to select chemicals or their precursors are decreasing with time, while the substitute chemical BPS showed an increasing trend. Our results suggest potentially important exposure sources in this population and can inform targeted approaches to reduce exposure to these chemicals or their precursors. We found that there was an increasing trend of urinary triclocarban/triclosan concentrations with increased concentrations of triclocarban/triclosan listed as the active ingredient in the bar soap/liquid soap products that were reported being used by study participants. Our findings support that the use of products containing triclosan and triclocarban during pregnancy can significantly elevate exposure to these chemicals.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Urinary triclocarban levels of pregnant women were 37-fold higher than women of same age in NHANES

First study to quantify the reliability of BPF and triclocarban in pregnant women urine samples

Decreased exposure to BPA but increased exposure to BPS were observed during study period

Elevated triclocarban/triclosan levels were associated with the use of products containing them

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grants P42ES017198, P50ES026049, and UG3OD023251]. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the CDC, the Public Health Service, or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allmyr M, Adolfsson-Erici M, McLachlan MS, Sandborgh-Englund G. 2006. Triclosan in plasma and milk from Swedish nursing mothers and their exposure via personal care products. Sci Total Environ 372:87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertelsen RJ, Engel SM, Jusko TA, Calafat AM, Hoppin JA, London SJ, et al. 2014. Reliability of triclosan measures in repeated urine samples from norwegian pregnant women. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 24:517–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava HN, Leonard PA. 1996. Triclosan: Applications and safety. Am J Infect Control 24:209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JM, Kalkbrenner AE, Calafat AM, Bernert JT, Ye X, Silva MJ, et al. 2011a. Variability and predictors of urinary bisphenol a concentrations during pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect 119:131–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JM, Kalkbrenner AE, Calafat AM, Yolton K, Ye X, Dietrich KN, et al. 2011b. Impact of early-life bisphenol a exposure on behavior and executive function in children. Pediatrics 128:873–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JM, Just AC, Williams PL, Smith KW, Calafat AM, Hauser R. 2014. Personal care product use and urinary phthalate metabolite and paraben concentrations during pregnancy among women from a fertility clinic. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 24:459–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowska B 2003. Effects of 2,4-d and its metabolite 2,4-dichlorophenol on antioxidant enzymes and level of glutathione in human erythrocytes. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 135:435–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calafat AM, Valentin-Blasini L, Ye X. 2015. Trends in exposure to chemicals in personal care and consumer products. Curr Environ Health Rep 2:348–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantonwine D, Meeker JD, Hu H, Sanchez BN, Lamadrid-Figueroa H, Mercado-Garcia A, et al. 2010. Bisphenol a exposure in mexico city and risk of prematurity: A pilot nested case control study. Environ Health 9:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantonwine DE, Cordero JF, Rivera-Gonzalez LO, Anzalota Del Toro LV, Ferguson KK, Mukherjee B, et al. 2014. Urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations among pregnant women in northern puerto rico: Distribution, temporal variability, and predictors. Environ Int 62:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas L, Fernandez MF, Llop S, Guxens M, Ballester F, Olea N, et al. 2011. Urinary concentrations of phthalates and phenols in a population of spanish pregnant women and children. Environ Int 37:858–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009. Fourth report on human exposure to environmental chemicals. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2012. Increasing prevalence of diagnosed diabetes--united states and puerto rico, 1995–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 61:918–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018. Fourth report on human exposure to environmental chemicals. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport/pdf/FourthReport_UpdatedTables_Volume1_Mar2018.pdf [accessed 04/04/2018.

- Chen J, Ahn KC, Gee NA, Ahmed MI, Duleba AJ, Zhao L, et al. 2008. Triclocarban enhances testosterone action: A new type of endocrine disruptor? Endocrinology 149:1173–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coogan MA, La Point TW. 2008. Snail bioaccumulation of triclocarban, triclosan, and methyltriclosan in a north texas, USA, stream affected by wastewater treatment plant runoff. Environ Toxicol Chem 27:1788–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewalque L, Pirard C, Vandepaer S, Charlier C. 2015. Temporal variability of urinary concentrations of phthalate metabolites, parabens and benzophenone-3 in a belgian adult population. Environ Res 142:414–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon JP, Giudice LC, Hauser R, Prins GS, Soto AM, et al. 2009. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: An endocrine society scientific statement. Endocr Rev 30:293–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson RE, Nishioka M, Standley LJ, Perovich LJ, Brody JG, Rudel RA. 2012. Endocrine disruptors and asthma-associated chemicals in consumer products. Environ Health Perspect 120:935–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel LS, Buckley JP, Yang G, Liao LM, Satagopan J, Calafat AM, et al. 2014. Predictors and variability of repeat measurements of urinary phenols and parabens in a cohort of shanghai women and men. Environ Health Perspect 122:733–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Working Group. Skin deep cosmetic database Available: https://www.ewg.org/skindeep-.WoX_EZM-e1s [accessed Oct 28 2017].

- Fisher M, MacPherson S, Braun JM, Hauser R, Walker M, Feeley M, et al. 2017. Paraben concentrations in maternal urine and breast milk and its association with personal care product use. Environ Sci Technol 51:4009–4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration. 2016. Safety and effectiveness of consumer antiseptics: Topical antimicrobial drug products for over-the-counter human use. Fed Regist 81:61106–61130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen H, Jensen TK, Jorgensen N, Kyhl HB, Husby S, Skakkebaek NE, et al. 2014Human urinary excretion of non-persistent environmental chemicals: An overview of danish data collected between 2006 and 2012. Reproduction 147:555–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme H, Kuchler T, Otto T, Pilz K, Muller J, Wenzel A. 2002. Occurrence of phthalates and bisphenol a and f in the environment. Water Res 36:1429–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garza JR, Perez EA, Prelip M, McCarthy WJ, Feldman JM, Canino G, et al. 2011. Occurrence and correlates of overweight and obesity among island puerto rican youth. Ethn Dis 21:163–169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert WM. 1990. Maternal, fetal, and neonatal physiology in pregnancy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2:4–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez H, Farbrot A, Larko O, Wennberg AM. 2006. Percutaneous absorption of the sunscreen benzophenone-3 after repeated whole-body applications, with and without ultraviolet irradiation. Br J Dermatol 154:337–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidry VT, Longnecker MP, Aase H, Eggesbo M, Zeiner P, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, et al. 2015. Measurement of total and free urinary phenol and paraben concentrations over the course of pregnancy: Assessing reliability and contamination of specimens in the norwegian mother and child cohort study. Environ Health Perspect 123:705–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Kannan K. 2013. A survey of phthalates and parabens in personal care products from the united states and its implications for human exposure. Environ Sci Technol 47:14442–14449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyllenhammar I, Glynn A, Jonsson BA, Lindh CH, Darnerud PO, Svensson K, et al. 2017. Diverging temporal trends of human exposure to bisphenols and plastizisers, such as phthalates, caused by substitution of legacy edcs? Environ Res 153:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C, Lim YH, Hong YC. 2016. Ten-year trends in urinary concentrations of triclosan and benzophenone-3 in the general u.S. Population from 2003 to 2012. Environ Pollut 208:803–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankinson SE, Manson JE, Spiegelman D, Willett WC, Longcope C, Speizer FE. 1995. Reproducibility of plasma hormone levels in postmenopausal women over a 2–3-year period. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 4:649–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan AL, Baduel C, Toms LM, Calafat AM, Ye X, Hobson P, et al. 2015. Use of pooled samples to assess human exposure to parabens, benzophenone-3 and triclosan in queensland, australia. Environ Int 85:77–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung RW, Reed LD. 1990. Estimation of average concentration in the presence of nondetectable values. Applied occupational and environmental hygiene 5:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ji K, Hong S, Kho Y, Choi K. 2013. Effects of bisphenol s exposure on endocrine functions and reproduction of zebrafish. Environ Sci Technol 47:8793–8800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PI, Koustas E, Vesterinen HM, Sutton P, Atchley DS, Kim AN, et al. 2016. Application of the navigation guide systematic review methodology to the evidence for developmental and reproductive toxicity of triclosan. Environ Int 92-93:716–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Kim S, Park J, Kim HJ, Lee J, Choi G, et al. 2013. Urinary paraben concentrations among pregnant women and their matching newborn infants of korea, and the association with oxidative stress biomarkers. Sci Total Environ 461–462:214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpuzoglu E, Holladay SD, Gogal RM, Jr. 2013. Parabens: Potential impact of low-affinity estrogen receptor binding chemicals on human health. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev 16:321–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper-Sonnenberg M, Wittsiepe J, Koch HM, Fromme H, Wilhelm M. 2012. Determination of bisphenol a in urine from mother-child pairs-results from the duisburg birth cohort study, germany. J Toxicol Environ Health A 75:429–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Chakraborty A, Kural MR, Roy P. 2009. Alteration of testicular steroidogenesis and histopathology of reproductive system in male rats treated with triclosan. Reprod Toxicol 27:177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaKind JS, Naiman DQ. 2015. Temporal trends in bisphenol a exposure in the united states from 2003–2012 and factors associated with bpa exposure: Spot samples and urine dilution complicate data interpretation. Environ Res 142:84–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassen TH, Frederiksen H, Jensen TK, Petersen JH, Main KM, Skakkebaek NE, et al. 2013. Temporal variability in urinary excretion of bisphenol a and seven other phenols in spot, morning, and 24-h urine samples. Environ Res 126:164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao C, Liu F, Alomirah H, Loi VD, Mohd MA, Moon HB, et al. 2012a. Bisphenol s in urine from the united states and seven asian countries: Occurrence and human exposures. Environ Sci Technol 46:6860–6866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao C, Liu F, Guo Y, Moon HB, Nakata H, Wu Q, et al. 2012b. Occurrence of eight bisphenol analogues in indoor dust from the united states and several asian countries: Implications for human exposure. Environ Sci Technol 46:9138–9145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao C, Kannan K. 2013. Concentrations and profiles of bisphenol a and other bisphenol analogues in foodstuffs from the united states and their implications for human exposure. J Agric Food Chem 61:4655–4662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao C, Kannan K. 2014. A survey of alkylphenols, bisphenols, and triclosan in personal care products from china and the united states. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 67:50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalingaiah S, Meeker JD, Pearson KR, Calafat AM, Ye X, Petrozza J, et al. 2008. Temporal variability and predictors of urinary bisphenol a concentrations in men and women. Environ Health Perspect 116:173–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marszalek JR, Lodish HF. 2005. Docosahexaenoic acid, fatty acid-interacting proteins, and neuronal function: Breastmilk and fish are good for you. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 21:633–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meador JP, Yeh A, Young G, Gallagher EP. 2016. Contaminants of emerging concern in a large temperate estuary. Environ Pollut 213:254–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeker JD. 2012. Exposure to environmental endocrine disruptors and child development. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 166:952–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeker JD, Cantonwine DE, Rivera-Gonzalez LO, Ferguson KK, Mukherjee B, Calafat AM, et al. 2013. Distribution, variability, and predictors of urinary concentrations of phenols and parabens among pregnant women in puerto rico. Environ Sci Technol 47:3439–3447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Molina JM, Amaya E, Grimaldi M, Saenz JM, Real M, Fernandez MF, et al. 2013. In vitro study on the agonistic and antagonistic activities of bisphenol-s and other bisphenol-a congeners and derivatives via nuclear receptors. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 272:127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen ME, Calafat AM, Ye X, Wong LY, Wright DJ, Pirkle JL, et al. 2014. Urinary concentrations of environmental phenols in pregnant women in a pilot study of the national children’s study. Environ Res 129:32–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss T, Howes D, Williams FM. 2000. Percutaneous penetration and dermal metabolism of triclosan (2,4, 4’-trichloro-2’-hydroxydiphenyl ether). Food Chem Toxicol 38:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myridakis A, Fthenou E, Balaska E, Vakinti M, Kogevinas M, Stephanou EG. 2015. Phthalate esters, parabens and bisphenol-a exposure among mothers and their children in greece (rhea cohort). Environ Int 83:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naderi M, Wong MY, Gholami F. 2014. Developmental exposure of zebrafish (danio rerio) to bisphenol-s impairs subsequent reproduction potential and hormonal balance in adults. Aquat Toxicol 148:195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassan FL, Coull BA, Gaskins AJ, Williams MA, Skakkebaek NE, Ford JB, et al. 2017Personal care product use in men and urinary concentrations of select phthalate metabolites and parabens: Results from the environment and reproductive health (earth) study. Environ Health Perspect 125:087012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Library Of Medicine US. 2010. Household products database: Health and safety information on household products. Archived web site. Retrieved from the library of congress. Available: https://www.loc.gov/item/lcwa00095498/ [accessed Feb 15 2018].

- Nepomnaschy PA, Baird DD, Weinberg CR, Hoppin JA, Longnecker MP, Wilcox AJ. 2009. Within-person variability in urinary bisphenol a concentrations: Measurements from specimens after long-term frozen storage. Environ Res 109:734–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North EJ, Halden RU. 2013. Plastics and environmental health: The road ahead. Rev Environ Health 28:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otero-Gonzalez M, Garcia-Fragoso L. 2008. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in a group of children between the ages of 2 to 12 years old in puerto rico. P R Health Sci J 27:159–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JW, Ashby J. 2002. Critical review and evaluation of the uterotrophic bioassay for the identification of possible estrogen agonists and antagonists: In support of the validation of the oecd uterotrophic protocols for the laboratory rodent. Organisation for economic co-operation and development. Crit Rev Toxicol 32:445–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perencevich EN, Wong MT, Harris AD. 2001. National and regional assessment of the antibacterial soap market: A step toward determining the impact of prevalent antibacterial soaps. Am J Infect Control 29:281–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera F, Vishnevetsky J, Herbstman JB, Calafat AM, Xiong W, Rauh V, et al. 2012. Prenatal bisphenol a exposure and child behavior in an inner-city cohort. Environ Health Perspect 120:1190–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez CM, Guzman M, Ortiz AP, Estrella M, Valle Y, Perez N, et al. 2008. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in san juan, puerto rico. Ethn Dis 18:434–441. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippat C, Mortamais M, Chevrier C, Petit C, Calafat AM, Ye X, et al. 2012. Exposure to phthalates and phenols during pregnancy and offspring size at birth. Environ Health Perspect 120:464–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippat C, Wolff MS, Calafat AM, Ye X, Bausell R, Meadows M, et al. 2013. Prenatal exposure to environmental phenols: Concentrations in amniotic fluid and variability in urinary concentrations during pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect 121:1225–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippat C, Bennett D, Calafat AM, Picciotto IH. 2015. Exposure to select phthalates and phenols through use of personal care products among californian adults and their children. Environ Res 140:369–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philips EM, Jaddoe VWV, Asimakopoulos AG, Kannan K, Steegers EAP, Santos S, et al. 2018. Bisphenol and phthalate concentrations and its determinants among pregnant women in a population-based cohort in the netherlands, 2004–5. Environ Res 161:562–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack AZ, Perkins NJ, Sjaarda L, Mumford SL, Kannan K, Philippat C, et al. 2016. Variability and exposure classification of urinary phenol and paraben metabolite concentrations in reproductive-aged women. Environ Res 151:513–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pycke BF, Geer LA, Dalloul M, Abulafia O, Jenck AM, Halden RU. 2014. Human fetal exposure to triclosan and triclocarban in an urban population from brooklyn, new york. Environ Sci Technol 48:8831–8838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves KW, Luo J, Hankinson SE, Hendryx M, Margolis KL, Manson JE, et al. 2014. Within-person variability of urinary bisphenol-a in postmenopausal women. Environ Res 135:285–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Soto WT, Rodriguez-Figueroa L, Calderon G. 2010. Prevalence of childhood obesity in a representative sample of elementary school children in puerto rico by socio-demographic characteristics, 2008. P R Health Sci J 29:357–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochester JR, Bolden AL. 2015. Bisphenol s and f: A systematic review and comparison of the hormonal activity of bisphenol a substitutes. Environ Health Perspect 123:643–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner B 2015. Fundamentals of biostatistics:Nelson Education.

- Shen HY, Jiang HL, Mao HL, Pan G, Zhou L, Cao YF. 2007. Simultaneous determination of seven phthalates and four parabens in cosmetic products using hplc-dad and gc-ms methods. J Sep Sci 30:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirai S, Suzuki Y, Yoshinaga J, Shiraishi H, Mizumoto Y. 2013. Urinary excretion of parabens in pregnant japanese women. Reprod Toxicol 35:96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KW, Braun JM, Williams PL, Ehrlich S, Correia KF, Calafat AM, et al. 2012. Predictors and variability of urinary paraben concentrations in men and women, including before and during pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect 120:1538–1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S, Song M, Zeng L, Wang T, Liu R, Ruan T, et al. 2014. Occurrence and profiles of bisphenol analogues in municipal sewage sludge in china. Environ Pollut 186:14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soni MG, Burdock GA, Taylor SL, Greenberg NA. 2001. Safety assessment of propyl paraben: A review of the published literature. Food Chem Toxicol 39:513–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soni MG, Carabin IG, Burdock GA. 2005. Safety assessment of esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid (parabens). Food Chem Toxicol 43:985–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroheker T, Chagnon MC, Pinnert MF, Berges R, Canivenc-Lavier MC. 2003. Estrogenic effects of food wrap packaging xenoestrogens and flavonoids in female wistar rats: A comparative study. Reprod Toxicol 17:421–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefre de Renzy-Martin K, Frederiksen H, Christensen JS, Boye Kyhl H, Andersson AM, Husby S, et al. 2014. Current exposure of 200 pregnant danish women to phthalates, parabens and phenols. Reproduction 147:443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelbaum SL, Britton JA, Calafat AM, Ye X, Silva MJ, Reidy JA, et al. 2008. Temporal variability in urinary concentrations of phthalate metabolites, phytoestrogens and phenols among minority children in the united states. Environ Res 106:257–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vela-Soria F, Ballesteros O, Zafra-Gomez A, Ballesteros L, Navalon A. 2014. Uhplc-ms/ms method for the determination of bisphenol a and its chlorinated derivatives, bisphenol s, parabens, and benzophenones in human urine samples. Anal Bioanal Chem 406:3773–3785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernet C, Pin I, Giorgis-Allemand L, Philippat C, Benmerad M, Quentin J, et al. 2017. In utero exposure to select phenols and phthalates and respiratory health in five-year-old boys: A prospective study. Environ Health Perspect 125:097006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernet C, Philippat C, Calafat AM, Ye X, Lyon-Caen S, Siroux V, et al. 2018. Within-day, between-day, and between-week variability of urinary concentrations of phenol biomarkers in pregnant women. Environ Health Perspect 126:037005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinas R, Watson CS. 2013. Bisphenol s disrupts estradiol-induced nongenomic signaling in a rat pituitary cell line: Effects on cell functions. Environ Health Perspect 121:352–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vom Saal FS, Welshons WV. 2014. Evidence that bisphenol a (bpa) can be accurately measured without contamination in human serum and urine, and that bpa causes numerous hazards from multiple routes of exposure. Mol Cell Endocrinol 398:101–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DJ, Ferguson KK, Anzalota Del Toro LV, Alshawabkeh AN, Cordero JF, Meeker JD. 2015. Associations between urinary phenol and paraben concentrations and markers of oxidative stress and inflammation among pregnant women in puerto rico. Int J Hyg Environ Health 218:212–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]