Abstract

Formaldehyde (FA) is a human leukemogen and is hematotoxic in human and mouse. The biological plausibility of FA-induced leukemia is controversial because few studies have reported FA-induced bone marrow (BM) toxicity, and none have reported BM stem/progenitor cell toxicity. We sought to comprehensively examine FA hematoxicity in vivo in mouse peripheral blood, BM, spleen and myeloid progenitors. We included the leukemogen and BM toxicant, benzene (BZ), as a positive control, separately and together with FA as co-exposure occurs frequently. We exposed BALB/c mice to 3mg/m3 FA in air for 2 weeks, mimicking occupational exposure, then measured complete blood counts, nucleated BM cell count, and myeloid progenitor colony formation. We also investigated potential mechanisms of FA toxicity, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, apoptosis, and hematopoietic growth factor and receptor levels. FA exposure significantly reduced nucleated BM cells and BM-derived colony-forming unit-granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM) and burst-forming unit-erythroid (BFU-E); down-regulated GM-CSFRα and EPOR expression; increased ROS in nucleated BM, spleen and CFU-GM cells; and apoptosis in nucleated spleen and CFU-GM cells. FA and BZ each similarly altered BM mature cells and stem/progenitor counts, BM and CFU-GM ROS, and apoptosis in spleen and CFU-GM but had differential effects on other endpoints. Co-exposure was more potent for several endpoints. Thus, FA is toxic to the mouse hematopoietic system, including BM stem/progenitor cells, and it enhances BZ-induced toxic effects. Our findings suggest that FA may induce BM toxicity by affecting myeloid progenitor growth and survival through oxidative damage and reduced expression levels of GM-CSFRα and EPOR.

Keywords: formaldehyde, benzene, hematotoxicity, bone marrow, myeloid progenitor

Introduction

Formaldehyde (FA) is an important chemical in the global economy and many workers are occupationally exposed to it. Substantially more people are exposed to FA environmentally, as it exists in tobacco smoke, automobile exhaust, household products and newly renovated buildings. FA is also a naturally occurring compound that is present at low levels in all living organisms (Zhang et al. 2010c). FA has been classified as a human leukemogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC 2012) and the US National Toxicology Program (NTP 2011) based on epidemiological studies. However, the biological plausibility of FA-induced leukemia is controversial, probably due to inconsistencies in human and animal studies and the lack of a known mechanism for leukemia induction.

In exposed workers, we reported that FA reduced counts of, and induced leukemia-specific chromosome damage in, circulating myeloid progenitor cells in blood, suggesting that FA induces bone marrow (BM) toxicity in humans (Lan et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2010b). Although FA did not induce leukemia in mice or rats exposed to life-long high levels of FA in a much earlier study (Kerns et al. 1983), we have recently shown that relatively low levels of FA induces toxic effects in BM of mice exposed by short-term nose-only inhalation (Ye et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2013). However, toxicity to hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) or progenitor cells (HPC) in BM, the targets for leukemogenesis, has not been demonstrated previously. In the current study, we comprehensively analyze toxicity and potential underlying mechanisms of toxicity in BM, HSC and myeloid progenitor cells, spleen and peripheral blood of mice exposed to FA in air for two weeks similar to an occupational exposure scenario.

Oxidative stress has been shown to occur in multiple tissues in FA-exposed rats and mice (Gulec et al. 2006; Lino-dos-Santos-Franco et al. 2011; Matsuoka et al. 2010; NTP 2010; Wang et al. 2013) and it is a proposed mechanism of leukemogenesis induced by the leukemogen benzene (McHale et al. 2012). Various pathologies can result from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis (Circu and Aw 2010) and apoptosis has been proposed as a possible mechanism underlying hematopoietic system diseases such as aplastic anemia and myelodysplastic syndromes (Callera and Falcão 1997; Raza et al. 1995). Here, we examine these endpoints in nucleated BM, spleen and myeloid progenitor cells. We also examine levels of the colony-stimulating factors (CSF), including interleukin-3 (IL-3), granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), erythropoietin (EPO), and their receptors IL-3Rα, GM-CSFRα and EPOR, all of which are key regulators of the development of mature blood cells from HSC (Shieh and Moore 1989). We also analyzed the effects of benzene (BZ), a known leukemogen that is toxic to BM (McHale et al. 2012; Snyder 2012), on the same endpoints in parallel as a positive control. Further, as BZ and FA usually coexist in newly remodeled buildings, common household products, cigarette smoke and automobile exhaust, we also examined the combined effects of FA and BZ.

Materials and methods

Animal care

Specific-pathogen-free male BALB/c mice (6 weeks old, 20±2 g weight) were purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Hubei Province (Wuhan, China), and housed under standard laboratory conditions (temperature, 20–25°C; humidity, 50–70%; and 12-hr day/night cycles). The mice were fed standard chow diet and water ad libitum except during exposure periods. All mice were quarantined for one week before study initiation. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the Office of Scientific Research Management of Central China Normal University (CCNU-SKY-2011–008).

Experimental design

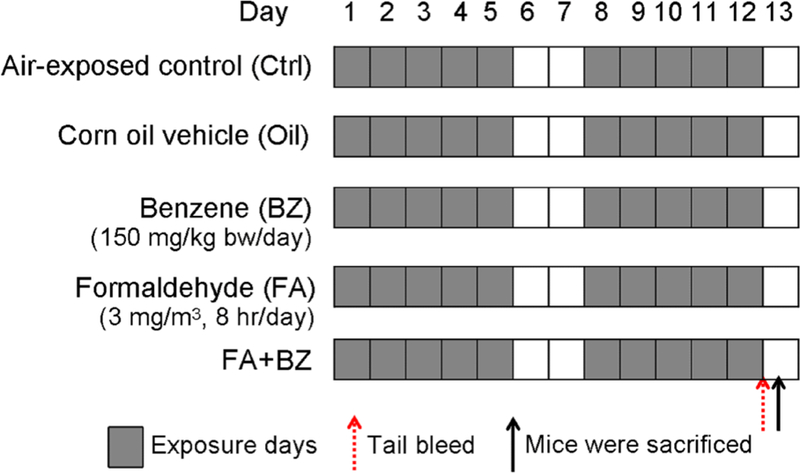

BALB/c mice were randomly divided into five groups, comprising air-exposed control (Ctrl) group, corn oil vehicle (Oil) group, BZ group, FA group, and FA-combined with BZ (FA+BZ) group with 5 mice per group. The exposure scheme of this study is shown in Figure 1. The number of independent experiments conducted and the numbers of mice analyzed per group for each endpoint are detailed in Supplemental Material, Table S1. To ensure our data quality, we performed five independent experiments exposing mice to FA, BZ, and FA+BZ. We tested CBC from all 5 experiments (a total of 25 mice) and ROS in nucleated BM and spleen cells from 3 experiments (a total of 15 mice). Spleen index (ratio of spleen weight to mouse body weight), CSF levels and myeloid progenitor colony-formation were investigated in 2 independent experiments (a total of 10 mice). Due to a limited amount of BM tissue and limited number of BM myeloid progenitor colonies obtained from each mouse, we only measured ROS, CSFR and caspsase-3 in BM myeloid progenitor cells in 1 experiment (Table S1). Expression levels of activated caspsase-3 and CSFR were determined by western blot in three of five mice from 1 experiment.

Figure 1.

Experimental groups and exposure scheme.

Chemical exposure

BZ (Sinopharm, Shanghai, China) was diluted in corn oil and administered via gavage in a single dose of 150 mg/kg body weight (bw) in a volume of 5 mL/kg bw once daily at 8:30 a.m., 5 days/week, for 2 weeks. The Oil group was administrated corn oil alone during the same period. This dose of 150 mg/kg bw per day of BZ by gavage was reported to induce hematopoietic neoplasms over a lifetime (Inoue and Hirabayashi 2010; Yi and Yoon 2008).

Previously, we examined bone marrow toxicity in mice exposed to FA by nose-only inhalation (Ye et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2013) to avoid minor confounding from skin absorption (NTP 2011). However, the nose-only apparatus is inhumane in that it immobilizes the animals, causing restraint stress that can impact immune function (Irwin et al. 1990; Thomson et al. 2009). Further, whole body exposure more realistically reflects human exposure scenarios. In the present study, the mice were exposed to FA in air in an environmentally controlled 8.4 L-glass chamber in which animal movement was unrestricted. Ten mice were treated per chamber: 5 mice each from the blank control group and carrier control oil group were housed together and received ambient air while 5 mice from the FA group and 5 mice from the FA+BZ group were housed together and received 3.0 mg/m3 FA. FA was prepared from 10% formalin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and the solution was administered through the environmental chamber, at a controlled concentration of 3.0 mg/m3, derived from the former Chinese occupational exposure limits (maximum allowable concentration) (Tang et al. 2009). During the experiment, environmental parameters were controlled automatically. Air temperature, humidity and ventilation rate were maintained at 23±0.5°C, 45±5.0% and 1.5 L/min, respectively. Mice were exposed from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., 8 hr/day, 5 days/week, for 2 weeks. During exposure, air FA concentration in the chamber was monitored every 2 hr using a Gaseous FA Analyzer (Interscan4160–2, Simi Valley, CA, USA); data are presented in Supplemental Material, Table S2. Body weights of each mouse were recorded every morning before exposure.

Biological sample preparation

Blood was collected from the caudal vein 1 hr after the last treatment and transferred to Eppendorf tubes containing ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA). At 9 a.m. on the 13th day, mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodiumat 100 mg/kg bw and then sacrificed by cervical dislocation. BM was flushed from femurs with a known volume of ice-cold Improved Minimum Essential Medium (IMEM) containing 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin and 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Spleens were placed in sterile Petri dishes within IMEM containing 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin and 2% FBS, and minced with scissors. The spleen cells were released into medium by syringe plunger after gentle mixing. Cell suspensions were filtered through a 50-μm nylon mesh and a single cell suspension was produced by gently and repeatedly drawing the BM and spleen cells through a syringe fitted with a 23-gauge needle. Nucleated BM and spleen cell counts were determined using a blood cell analyzer (Motenu MTN-21, Changchun, China) after removal of erythrocytes with ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) lysing reagent (150 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM potassium bicarbonate, 1mM EDTA).

Complete blood count (CBC)

Peripheral blood leukocyte (WBC), lymphocytes (LYM), neutrophilic granulocytes (GRA), monocytes (MON), red blood cells (RBC), platelet (PLT), hemoglobin (HGB)and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) were measured by a blood cell analyzer according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Histological assay

Mouse femurs were harvested and fixed in 4% buffered paraformaldehyde phosphate. After fixation for 24 h, femurs underwent decalcification in 10% EDTA for 2 weeks before further processing. Samples were embedded in paraffin, and at least three sections of 5 μm per tissue were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Qualitative examinations of prepared sections and capturing of images were carried out using a microscope (Leica DM 4000B, Berlin, Germany).

Myeloid progenitor colony-formation assay

Mature myeloid cells are derived from pluripotent HSC, via the multipotent myeloid progenitor cell known as colony-forming unit-granulocyte, erythrocyte, monocyte, macrophage (CFU-GEMM), and more committed myeloid progenitor cells. We assayed the colony forming capacity of these HSC/myeloid progenitor cells from mouse BM. Colonies derived from HSC/myeloid progenitors that give rise to granulocytes and macrophages are called colony-forming unit-granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM), whereas those that give rise to reticulocytes and erythrocytes are called burst-forming unit-erythroid (BFU-E). Nucleated BM cells were cultured in mouse methylcellulose complete media without EPO (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) to generate CFU-GM, and in mouse methylcellulose base media (R&D systems) with 3 U/mL EPO (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA) and 10 ng/mL IL-3 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) to generate BFU-E, according to protocols provided by R&D systems (https://www.rndsystems.com/resources/protocols/mouse-colony-forming-cell-cfc-assay-using-methylcellulose-based-media). Each 35 mm dish used for CFU-GM and BFU-E cultivation was plated with 1×105 and 2×105 nucleated BM cells, respectively. The number of CFU-GM and BFU-E colonies was scored in gridded dishes and harvested after 10 days and 12 days, respectively.

ROS assay

ROS levels in mouse nucleated BM, spleen, CFU-GM and BFU-E cells were determined by dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) fluorescent assay using a previously described procedure (Ye et al. 2013) with minor modifications. Briefly, 1×106 cells were suspended in 300 μL of 10 μM DCFH-DA (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Then cells were washed twice with 0.01 M PBS (pH7.4) and resuspended in 300 μL PBS. A 200-μL aliquot of the cell suspension was transferred into a 96-well microplate and the fluorescence intensity was measured at 488 nm (excitation) and 525 nm (emission) using a Microplate reader (BioTek Instruments FLx 800, VT, USA).

Western blot

Cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate and 0.1% SDS) with protease inhibitors (5mM EDTA, 2mM PMSF, 10 ng/mL leupeptin and 10 μg/mL aprotinin). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 12,000g for 10 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatants containing equal amounts of proteins (40 μg) were separated on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond, Escondido, CA, USA). Membranes were blocked, washed, and were incubated with mouse monoclonal antibodies against caspase-3 (AC031, 1:250) (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and β-actin (TDY041F, 1:5000) (Bioprimacy, Wuhan, China), goat polyclonal anti-IL-3Rα (also known as anti-CD123) antibodies (AF983, 0.2 μg/mL) (R&D systems), and rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA) against GM-CSFRα (sc-691, 1:800) and EPOR (sc-697, 1:800). Detection was performed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse, rabbit anti-goat or goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:5000) (Biosharp, Hefei, China). The signal was visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Bioprimacy) and X-ray film.

IL-3 and GM-CSF ELISA

Nucleated spleen cells were dispensed at 4×105/well in duplicate wells of a 96-well plate and stimulated using 10 μg/mL concanavalin A for 48 h in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS at 37°C. After incubation, 100 μL of the supernatant was collected, and the concentrations of IL-3 and GM-CSF were determined by ELISA kit (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA, and eBioscience, respectively) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance at 450 nm was recorded using a Microplate Reader (Bio-Tek Instruments PowerWave XS, VT, USA) with a reference wavelength of 630 nm.

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

RT-qPCR was performed to determine the relative Epo gene expression levels. Total RNA was isolated from mouse kidneys with RNAiso Plus reagent (Takara, Otsu, Shiga-ken, Japan). DNA contamination was removed with RNase-free DNase. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA using reverse transcriptase and oligo dT16 primer. Primers were designed for Epo (forward: 5’-GAATGGAGGTGGAAGAACAGG-3’, reverse: 5’-ACCCGAAGCAGTGAAGTGAG-3’) and the reference gene β-Actin (forward: 5’-GCATTGTTACCAACTGGGACG-3’, reverse: 5’-TGGCTGGGGTGTTGAAGG-3’). PCR amplification was performed using a SYBR Green Premix (Takara) with a CFX96 Real Time PCR Detection System (BioRad, CA, USA). The relative expression ratio of Epo gene for the treated group to the control group was calibrated against β-Actin gene using the calculation method:

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (San Diego, CA, USA). One-way ANOVA combined with Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used to determine the significance of differences between groups. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics 19.0 (Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

General systemic toxicity

Body weights were significantly reduced relative to the control group in the FA+BZ exposed group only, from days 3 to 13, with the exception of day 7 (Supplemental material, Figure S1). Although neither FA nor BZ alone significantly changed the body weight in comparison with the untreated control group (ctrl), treatment with both FA and BZ together (FA+BZ) did lower the body weight compared with BZ alone on Days 9–13, and FA alone on Days 4–6 and 8–12, in a statistically significant manner (Figure S1). FA did not significantly alter spleen index (ratio of spleen weight to mouse body weight) relative to controls but BZ and FA+BZ significantly reduced it (p<0.01, Supplemental Material, Figure S2).

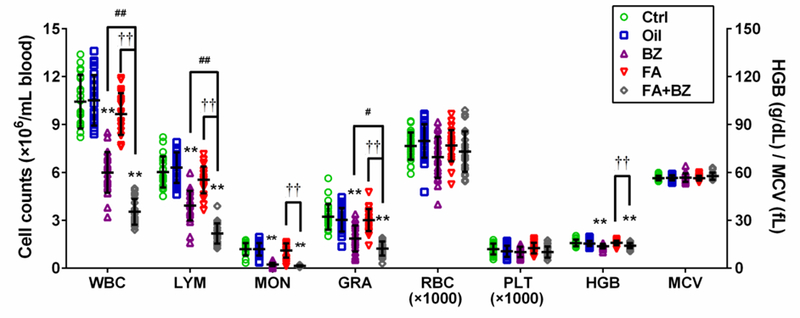

Blood cell counts

Exposure to FA led to reduced WBC, LYM and GRA counts by 7.4%, 8.2% and 6.2%, respectively, compared with the control group but the results were not statistically significant when data were merged from 25 mice in 5 independent experiments (Figure 2). In contrast, BZ exposure led to significant reductions in WBC, LYM, MON and GRA (p<0.01) as did co-exposure to FA and BZ (FA+BZ). In comparison with the BZ group, FA+BZ decreased WBC, LYM and GRA to 59% (p<0.01), 56% (p<0.01) and 66% (p<0.05), respectively. The decreases in WBC, LYM, MON, GRA and HGB were also statistically significant for the FA+BZ group compared to the FA group (p<0.01). RBC, PLT, and MCV were not significantly altered by any exposure. Data from each independent experiment are presented in Supplemental Material, Table S3.

Figure 2. Complete blood counts (CBC).

Data are merged from 25 mice in 5 independent experiments and presented as Mean±SD. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 compared with the corresponding control group; #p<0.05, ##p<0.01 compared with the corresponding BZ group; ††p<0.01 compared with the corresponding FA group. Data from each independent experiment were presented in Supplemental Material, Table S3.

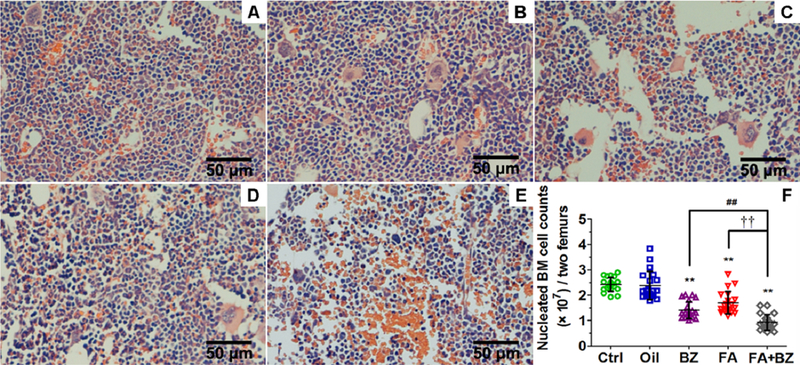

BM cellularity

Visual inspection of BM histological preparations indicated reduced cellularity of nucleated cells in femurs from mice exposed to FA, BZ and FA+BZ compared with controls (Figure 3A-E). No other lesions were noted in any histological sections and we did not observe a FA-induced increase in BM megakaryocytes as we found previously (Zhang et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2016). Quantification of nucleated BM cells using a blood cell analyzer revealed significant reductions in nucleated cells in mice exposed to FA (30%, p<0.01), BZ (42%, p<0.01), and FA+BZ (62%, p<0.01) compared with controls (Figure 3F). The effect of FA+BZ was significantly greater than treatment with FA and BZ alone (p<0.01). Data from each independent experiment are presented in Supplemental Material, Table S4.

Figure 3. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of nucleated BM cells.

Qualitative assessment by histopathology in (A) Control, (B) Oil, (C) BZ, (D) FA, and (E) FA+BZ. A representative image of H&E stained BM section is shown for each condition. (F) Quantitative assessment of cell counts. Data are merged from 20 mice in 4 independent experiments and presented as Mean±SD. **p<0.01 compared with the Control group; ##p<0.01 compared with the BZ group; ††p<0.01 compared with the FA group. Data from each independent experiment were presented in Supplemental Material, Table S4.

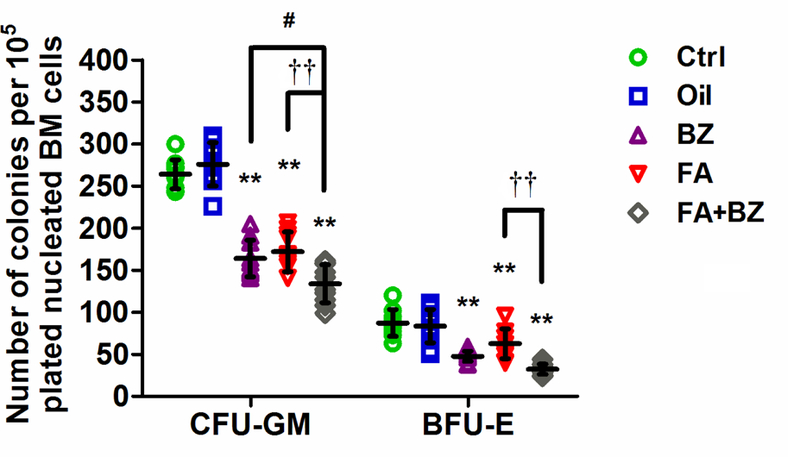

Myeloid progenitor colony formation

Exposure to FA induced a statistically significant decrease (p<0.01) in the number of CFU-GM colonies (by 35%) and BFU-E colonies (by 16%) compared with their respective control groups (Figure 4). FA+BZ also significantly reduced the number of CFU-GM and BFU-E (p<0.01) compared with the controls, and the decrease was significantly more than FA alone (p<0.01 for both CFU-GM and BFU-E) or BZ alone (p<0.05 for CFU-GM). Data from each independent experiment are presented in Supplemental Material, Table S5.

Figure 4. CFU-GM and BFU-E colony formation from nucleated BM cells.

Data are merged from 10 mice in 2 independent experiments and presented as mean±SD. **p<0.01 compared with the corresponding Ctrl group; #p<0.05 compared with the corresponding BZ group; ††p<0.01 compared with the corresponding FA group. Data from each independent experiment were presented in Supplemental Material, Table S5.

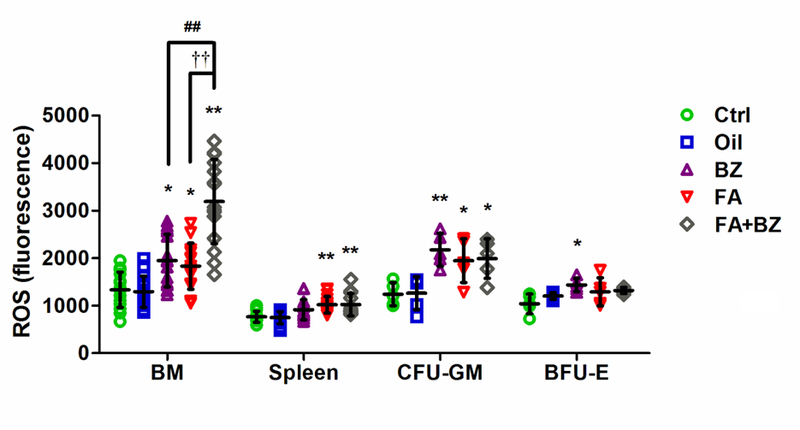

Reactive oxygen species

FA increased ROS levels significantly in nucleated BM cells by 37% (p<0.05), in nucleated spleen cells by 33% (p<0.01) and in CFU-GM cells by 57% (p<0.05), compared to their control groups (Figure 5). BZ significantly induced ROS in BM (p<0.05) and CFU-GM (p<0.01) but not in spleen cells. FA+BZ significantly (p<0.01) induced ROS levels in nucleated BM cells compared to the control and compared to FA (39%) and BZ (43%) alone. BZ was the only exposure that increased the level of ROS in BFU-E. Data from each independent experiment are presented in Supplemental Material, Table S6.

Figure 5. ROS levels in nucleated BM, spleen, CFU-GM and BFU-E cells.

Data are merged from 15 mice in 3 independent experiments for nucleated BM and spleen cells and 5 mice in one experiment for CFU-GM and BFU-E cells. Data are presented as mean±SD. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 compared with the corresponding Ctrl group; ##p<0.01 compared with the corresponding BZ group; ††p<0.01 compared with the corresponding FA group. Data from each independent experiment were presented in Supplemental Material, Table S6.

Apoptosis by caspase-3

Levels of activated caspase-3 (17 kD, 12 kD) were significantly increased by FA+BZ in nucleated BM cells (p<0.05); by FA, BZ and FA+BZ in spleen cells (p<0.05); and by FA, BZ and FA+BZ in CFU-GM cells (p<0.01, p<0.01 and p<0.05, respectively), indicating the induction of apoptosis (Figure 6). Caspase-3 was not significantly altered in BFU-E by any exposure condition.

Figure 6. Protein levels of cleaved-caspase-3 in mouse nucleated BM and spleen cells, CFU-GM and BFU-E cells.

(A) A representative Western blot image is shown; (B) Relative optical density (% of control). Data are presented as Mean±SD of data from three mice in a single experiment. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 compared with the corresponding Control group.

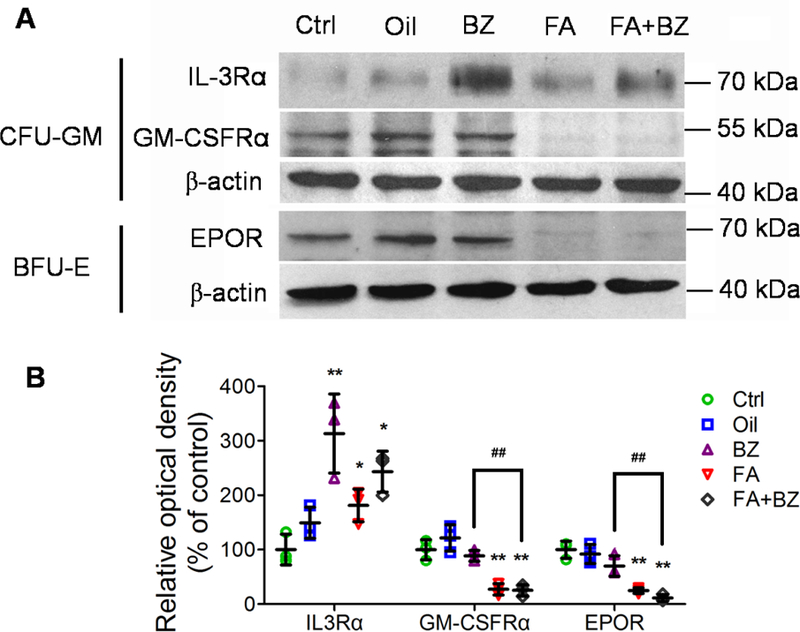

Hematopoietic growth factors and receptors

We measured protein levels of IL-3Rα and GM-CSFRα in CFU-GM and of EPOR in BFU-E. FA exposure significantly increased IL-3Rα levels (p<0.05) but decreased GM-CSFRα and EPOR levels (p<0.01) relative to the control (Figure 7). BZ significantly increased IL-3Rα levels relative to the control (p<0.01) but did not affect GM-CSFRα and EPOR levels. Compared to the control group, FA+BZ increased IL-3Rα levels (p<0.05) to a level intermediate to that induced by FA or BZ alone, and decreased GM-CSFRα and EPOR levels (p<0.01) to a similar level as FA alone. The decreases in GM-CSFRα and EPOR were also statistically significant for the FA+BZ group compared to the BZ group but not for the FA+BZ compared with the FA group.

Figure 7. Protein levels of IL-3Rα, GM-CSFRα and EPOR in myeloid progenitor cells.

(A) A representative Western blot image is shown; (B) Relative optical density (% of control). Data are presented as Mean±SD of data from three mice in a single experiment. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 compared with the corresponding Control group; ##p<0.01 compared with the corresponding BZ group.

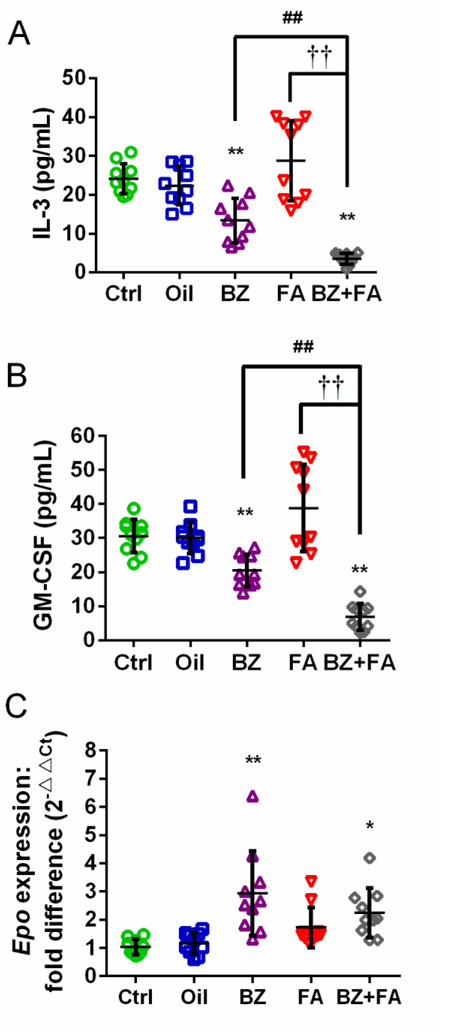

We measured IL-3 and GM-CSF in the supernatant of stimulated nucleated spleen cells and EPO mRNA expression in mouse kidney. FA exposure led to increased levels of IL-3 and GM-CSF by 20% and 26%, respectively (Figure 8A, B), but the increases were not statistically significant and findings were not consistent across experiments, with IL-3 and GM-CSF levels decreased in Experiment 1 (red triangles below median line) and increased in Experiment 2 (red triangles above median line). BZ and FA+BZ exposures each led to significantly decreased levels of IL-3 and GM-CSF compared with their controls (p<0.01, Figure 8A, B). Additionally, in comparison with BZ, FA+BZ significantly decreased the levels of IL-3 and GM-CSF to 26% and 34%, respectively (p<0.01, Figure 8A, B). The decreases in the levels of IL-3 and GM-CSF were also statistically significant for the FA+BZ group compared to the FA group (p<0.01). Data were consistent between experiments for BZ and FA+BZ exposure. Data from each independent experiment are presented in Supplemental Material, Table S7. Exposure to BZ and FA+BZ, but not to FA alone, significantly increased kidney Epo mRNA expression (p<0.01 and 0.05, respectively) (Figure 8C).

Figure 8. Protein levels of IL-3 (A) and GM-CSF (B) in the supernatants of stimulated nucleated spleen cells, and EPO mRNA levels in kidney cells (C).

Data are merged from 10 mice in 2 independent experiments and presented as Mean±SD. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 compared with the corresponding Ctrl group; ##p<0.01 compared with the corresponding BZ group; ††p<0.01 compared with the corresponding FA group. Data from each independent experiment were presented in Supplemental Material, Table S7.

Discussion

Our previous studies showed that FA reduced blood cell counts and circulating myeloid progenitors in exposed workers (Zhang et al. 2010b), suggestive of BM toxicity in humans. Further, we reported that FA reduced blood cell counts and induced genotoxicity, oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis in mouse BM in vivo (Ye et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2013). In the present study, we performed a comprehensive analysis of hematopoietic toxicity, including toxicity to stem/progenitor cells in BM, in FA-exposed mice. We compared FA-induced toxicity to that induced by BZ, a leukemogen and BM toxicant included as a positive control, and to that induced by co-exposure to FA and BZ. We showed, for the first time, that FA inhalation was associated with a strong suppressive effect on nucleated BM and stem/progenitor cell numbers similar to that of BZ. FA had a weaker effect on CBC than that of BZ and it synergized with BZ to induce stronger effects on several of these endpoints. Regarding mechanisms of toxicity, FA and BZ had similar effects on ROS in BM and CFU-GM cells and on apoptosis in BM, spleen, CFU-GM and BFU-E cells, but differential effects on ROS in spleen and BFU-E cells and on levels of hematopoietic stem cell growth factors, GM-CSFRα and EPOR. Our findings suggest that FA may induce BM toxicity by affecting myeloid progenitor growth and survival through oxidative stress and altered CSF receptor levels.

FA-induced BM and stem cell toxicity

Leukemia and other hematopoietic malignant diseases originate from damaged HSC or HPC that are mainly located in the BM (Passegue et al. 2003). Our previous study found a decrease in colony formation from circulating CFU-GM progenitor cells in the peripheral blood of workers occupationally exposed to FA, suggestive of BM toxicity. In the present study, we found that FA exposure, at levels and durations mimicking human occupational exposure, causes BM toxicity in exposed mice, manifests as a decrease in nucleated BM cells and in colony formation from BM, myeloid CFU-GM and BFU-E cells of mice after exposure to 3 mg/m3 FA. Thus, we have provided the first direct evidence of FA-induced toxicity to BM and BM hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in a mammalian model in vivo. A FA-induced decrease in nucleated BM cells and in colony formation from BM stem/progenitor cells, if it also occurs in humans, may increase the risk of hematopoietic malignant diseases.

Unlike BZ, whose metabolites are known to directly induce multiple toxic effects in BM (McHale et al. 2012), FA may not directly induce BM toxicity as evidenced by a lack of specific adducts, N6-formyllysine and N-2-hydroxymethyl-dG (N2-HOMe-dG), arising from isotope labeled exogenous FA in rats and primates (Edrissi et al. 2013; Kleinnijenhuis et al. 2013; Lu et al. 2011; Moeller et al. 2011). However, a mouse model lacking alcohol dehydrogenase 5 (Adh5, an FA metabolizing enzyme) was recently reported to have increased levels of baseline N2-HOMe-dG BM adducts compared to wild-type mice, and even greater levels following exposure to FA as methanol (Pontel et al. 2015). Adh2+/− Fancd2−/− mice exposed to methanol, which is quickly metabolized to FA, also had 15.5-fold reductions in HSC. We found that FA exposure decreased CFU-GM and BFU-E colonies cultured from nucleated BM cells of exposed wild-type mice. Thus, the role of FA exposure in inducing HSC toxicity, possible via the formation of specific adducts, in different species requires further investigation.

Previously, we detected increased DNA protein crosslinks (DPC), a hallmark of FA toxicity, in the BM of exposed mice (Ye et al 2013), though they were not detected earlier by others in the BM of normal and glutathione-depleted rats (Casanova-Schmitz et al. 1984; Casanova and Heck Hd 1987; Heck Hd and Casanova 1987). These differences may be due to the species difference or different exposure concentrations of FA. Previously, we proposed that glutathione or protein adducts (Ye et al. 2013) or inflammatory mediators induced by FA (Lino dos Santos Franco et al. 2006) may be produced in the nasal passages and transported to BM. These indirect mechanisms are speculative and require experimental validation.

Effect of FA on blood cell counts

As all blood cells are derived from HSC, toxicity to or suppression of HSC numbers is expected to manifest as reduced CBC. Previously, we reported that counts for WBC, major myeloid cell types, lymphocytes, red blood cells and platelets were significantly lower in workers exposed to FA compared to controls (Zhang et al. 2010b). In our previous mouse study, WBC and LYM were significantly decreased by 52% and 43%, respectively at 3 mg/m3 FA, and MON and GRA counts were not significantly altered. RBC count was also significantly reduced at 3 mg/m3 FA while platelet count was significantly increased (Zhang et al. 2013). In the present study, we also found that FA exposure decreased WBC and LYM, but the results were not statistically significant. In contrast, BZ exposure significantly decreased WBC, LYM, MON and GRA and FA+BZ decreased the counts of each cell type by more than each exposure alone in the present study.

The fact that formaldehyde exposure was performed in different ways between the present and previous mouse studies could have contributed to the different CBC findings. Compared with the whole-body route used in the present study, nose-only inhalation immobilizes the animals, causing restraint stress that affect immune response, apoptosis, and signaling pathways (Irwin et al. 1990; Thomson et al. 2009); thus the nose-only exposed mice may be more susceptible to external toxicants. Other endpoints such as ROS, apoptosis and megakaryocytes in BM were also increased more significantly in nose-only FA-exposed mice than in whole-body FA-exposed mice (Ye et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2016). For these reasons, the true effect of FA on CBC and underlying mechanisms of toxicity require further investigation.

Comparing changes in peripheral CBC, nucleated BM cell count and colony formation from myeloid progenitors, we found HSC/myeloid progenitor cells and nucleated BM cells were more sensitive to FA than peripheral blood cells. It is unclear why the significant and pronounced suppressive effect of FA on HSC/myeloid progenitor cells in BM is not manifest as significantly reduced CBC in circulating blood as is the case with BZ. Further studies are required to delineate BZ- and FA-specific effects on blood cell production.

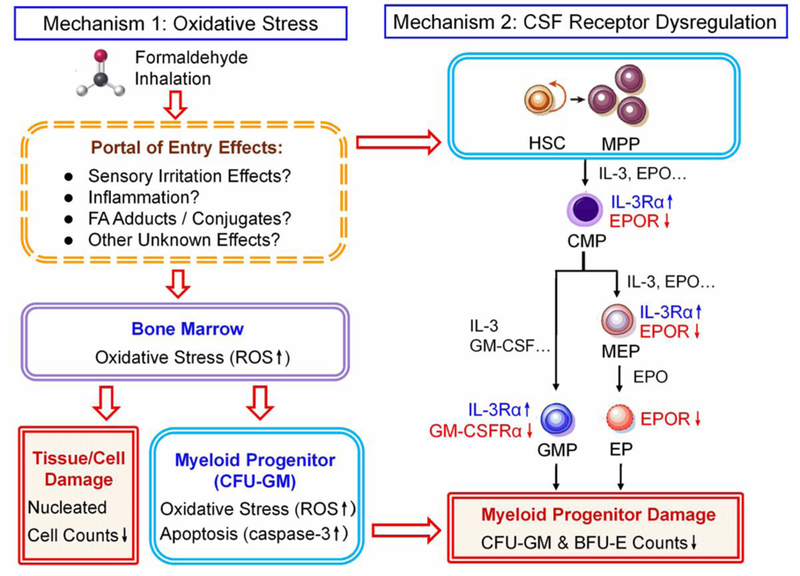

Potential mechanisms of bone marrow toxicity induced by FA

Although the underlying mechanisms of BM and stem/progenitor cell toxicity induced by FA are not clear, here we propose two potential mechanistic pathways involving oxidative stress and apoptosis (Mechanism 1), and CSF receptor dysregulation (Mechanism 2), as illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Potential mechanisms of toxicity induced by FA in mouse BM:

1. Oxidative stress, and 2. CSF receptor dysregulation. CMP, common myeloid progenitor; CSF, colony stimulating factor; EP, erythroid progenitor; EPO, erythropoietin; EPOR, EPO receptor; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor; GM-CSFRα, GM-CSF receptor α; GMP, granulocyte-monocyte progenitor; HSC, hematopoietic stem cells; IL-3, interleukin-3; IL-3Rα, IL-3 receptor α; MEP, megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor; MPP, multi-potent progenitor;

Mechanism 1 - Oxidative stress and apoptosis.

As oxidative stress is involved in the pathophysiology of some hematopoietic system diseases (Battisti et al. 2008; Zhou et al. 2010) and, in the HSC/HPC niche, is one of the proposed mechanisms of leukemogenesis induced by BZ (McHale et al. 2012; Snyder 2012), we hypothesized that ROS would play a role in FA-induced hematoxicity. Our previous mouse studies both found that ROS levels were increased in BM and spleens of FA-exposed mice (Ye et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2013). The present study confirmed these findings at 3 mg/m3 FA. FA and BZ each induced ROS to a similar degree in nucleated BM cells and to a greater degree in combination. If ROS were similarly elevated in human BM, it could cause oxidative stress and inflammation (Mantovani et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2013), and increase the risk of hematopoietic diseases. The background ROS level was higher in nucleated BM cells than in nucleated spleen cells, possibly due to the abundant myeloperoxidase in monocytes and granulocytes (Bos et al. 1978; Schultz and Kaminker 1962). This is in contrast to our previous study, in which background levels of ROS in spleen were higher, probably because oxygen-rich RBCs were not sufficiently removed from BM and spleen prior to measurement of ROS, as in the current study (Ye et al. 2013).

Intracellular ROS modulate self-renewal, proliferation and differentiation of HSC (Pervaiz et al. 2009). Hypoxic conditions promote “stemness”, prolong the life-span of the stem cells, improve their proliferative capacity, and reduce differentiation in vitro (Jang and Sharkis 2007). Excess ROS in HSC cause oxidative stress, leading to DNA damage, premature senescence, and loss of stem cell function (Ito et al. 2006; Yahata et al. 2011). In the present study, we found that FA and BZ each increased ROS levels in BM-derived CFU-GM cells from exposed mice, suggesting that the decrease in the colony number of CFU-GM may occur via induction of oxidative stress in HSC/HPC.

Accumulation of ROS induces mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening, cytochrome c release, activation of apoptosis signal-regulated kinase 1, subsequent activation of caspase-3, and ultimately cell apoptosis (Circu and Aw 2010; Shin et al. 2009). Caspase-3 is considered to be the most critical of the executioner caspases in the process of apoptosis and its activation is often used as an important indicator of apoptosis. When caspase-3 is activated, cleaved forms of 17 kDa and 12 kDa fragments can be detected by Western blot. We observed significant caspase-3 activation in spleen and CFU-GM of FA-exposed mice and BZ-exposed mice, indicative of apoptosis in HSC/HPC. Apoptosis is a physiological response to damage that prevents damaged cells, especially stem or progenitor cells, from transforming to cancer stem cells. Excessive apoptosis of HSC and BM cells may lead to disorders of self-renewal and differentiation, uncontrolled proliferation in HSC, and increased risk of cancer (Reya et al. 2001). The increased level of apoptosis in CFU-GM was consistent with the decreased number of CFU-GM colonies from the BM of FA-exposed mice. BFU-E colony formation was significantly reduced in FA-exposed mice but neither ROS nor apoptosis were significantly altered suggesting that other mechanisms may underlie the FA-induced BM and HSC/HPC toxicity.

Mechanism 2 – CSF receptor dysregulation

IL-3, GM-CSF and EPO positively regulate the development of myeloid progenitors, and play a crucial role in the formation, proliferation and differentiation of CFU-GM and BFU-E (Shieh and Moore, 1989). We hypothesized that changes in these CSF levels and the expression of their receptors could underlie the reduced CFU-GM and BFU-E colony formation induced by FA and BZ. Though the effect of FA on IL-3 or GM-CSF levels was inconclusive due to a lack of consistent results in independent experiments, FA enhanced the decreases in IL-3 and GM-CSF induced by BZ alone. IL-3Rα was increased slightly in CFU-GM by FA, and to a greater degree by BZ perhaps as a compensatory response to reduced IL-3 levels. Elevated expression of IL-3Rα was observed in patients with leukemia mainly acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (Testa et al. 2004). GM-CSFRα and EPOR were reduced significantly by FA and FA+BZ but not by BZ alone, suggestive of the different mechanisms of BM and HSC/HPC toxicity induced by FA and BZ.

In the present study, BFU-E colony numbers were significantly reduced in FA and BZ exposed mice but RBC was not decreased significantly in peripheral blood. Increased EPO production is a compensatory response to anemia (Walkley 2011), particularly anemia associated with BM failure (Fried 2009). In our study, BZ and BZ together with FA, but not FA alone, significantly increased EPO mRNA levels. FA and FA+BZ, but not BZ alone, significantly reduced EPOR levels in BFU-E. Increased EPO mRNA could reflect a compensatory mechanism to maintain RBC homeostasis in the presence of BZ, but reduced EPOR does not explain why RBC counts are unaffected by FA. Thus, the differential responses of the CSFs and their receptors to FA and BZ should be further investigated as potential contributors to differences in CBC counts following exposure to these chemicals despite similar myeloid progenitor toxicity.

FA and BZ co-exposure

It is important to study the joint effects of FA and BZ as co-exposure to them occurs widely in cigarette smoke, automobile exhaust, and newly renovated offices and houses. Increased exposure to BZ and FA, as well as other chemicals, through these sources may be associated with childhood leukemia risk (Ghosh et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2011; Metayer et al. 2013; Milne et al. 2012; Reid et al. 2011).

A major strength of our study is the inclusion of BZ as a positive control separately and together with FA, allowing us to compare effects and mechanisms. Our findings suggest that hematotoxicity may be greater from co-exposure to FA and BZ than from exposure to either chemical alone, and are supported by a few other studies in mice published only in Chinese language journals (Tang et al. 2004; Wan and Xiaokaiti 2009; Zhang et al. 2010a; Zhang et al. 2010d). These studies reported joint effects of FA and BZ on genotoxicity shown as increased micronuclei and/or COMET tail in the BM of Kunming mice (Tang et al. 2004; Wan and Xiaokaiti 2009; Zhang et al. 2010d) and BALB/c mice (Zhang et al. 2010a), compared with mice exposed to either chemical alone. To the best of our knowledge, our current study is the first study to examine hematopoietic toxicities and potential mechanisms in BM stem/progenitor cells of mice exposed to FA and BZ separately and in combination. Exposure to FA and BZ separately had similar suppressive effects on nucleated BM and progenitor cell numbers and together they exhibited stronger effects.

FA and BZ together exerted stronger suppressive effects on blood WBC, LYM and GRA, BM mature and progenitor cell numbers, BM ROS, IL-3 and GM-CSF levels, than either chemical alone. Differential effects of FA and BZ exposure were observed in the present study on CBC, spleen index, ROS levels in different tissues, and CSF and CSF receptor levels. BZ significantly decreased IL-3 and GM-CSF and FA decreased receptor levels of GM-CSF and EPO. Together, these effects may explain the interaction of BZ and FA in inducing toxic effects to BM and HSC/HPC greater than those induced by either chemical alone. Further studies are needed to understand mechanisms of FA and BZ co-exposure effects.

Limitations of the present study

In the present study, we proposed that FA alters myeloid progenitor growth and survival through oxidative stress and reduced expression levels of GM-CSFRα and EPOR. Future studies are needed to discern how FA (especially at low levels) increases oxidative stress in BM and reduces levels of GM-CSFRα and EPOR without reaching BM directly, or through the formation of toxic intermediates such as reactive glutathione or protein adducts or inflammatory molecules in the lung as discussed above. Inflammation at distal sites can alter hematopoiesis in BM releasing immature cells into the circulation in order to effect repair (Denburg and van Eeden 2006; Schuettpelz and Link 2013) and chronic pro-inflammatory signaling can lead to HSC exhaustion (Schuettpelz and Link 2013). Altered expression of miRNAs and mRNAs related to immune system/ inflammation signaling was reported in both the nose and WBC of FA-exposed rats suggesting that miRNAs may, in part, regulate immune/inflammatory responses (Rager et al. 2013).

Another limitation of our FA inhalation studies in mice is that mice may substantially reduce their respiratory minute volume in the presence of FA (a sensory irritant) (ASTM 1984), potentially leading to hypoxia (Pialoux and Mounier 2012). Thus, it is important to examine these proposed mechanisms in monkeys or rats exposed to FA and FA/BZ mixtures, or in in vitro models of BM toxicity. Further, future studies should assess the role of hypoxia in FA-induced toxicity in exposed mice, particularly as the hypoxia-induced factor (HIF) regulates whether HSCs remain quiescent or differentiate, through a comprehensive transcription network (Zhang and Sadek 2014).

Although we showed FA and BZ co-exposure had more potent toxic effects than either chemical alone for several endpoints such as nucleated BM cell counts and colony formation from BM myeloid progenitors, the exact mechanisms are not clear. Further studies are necessary to tease apart the mechanistic effects underlying hematotoxicity associated with FA and BZ exposure and co-exposure.

A final limitation of our study is that we have examined effects at a single dose of 3 mg/m3. Future studies should examine dose-response of these effects at a range of exposure levels.

Conclusion

We report for the first time that inhaled FA is toxic to hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in BM in vivo, in an exposure scenario comparable to human occupational exposure. Our study shows that FA and BZ are similarly toxic to mature and stem/progenitor cells in BM but that FA has a weaker effect on CBC in the blood. Oxidative stress, apoptosis and dysregulation of CSF receptors are potential underlying mechanisms of FA-induced hematopoietic stem/progenitor toxicity (Figure 9). Separately, FA and BZ have differential effects on cellular toxicity and co-exposure to them has more potent effects than either chemical alone for several endpoints.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China-Key Program (51136002) to XY, National Institute of Health (R01ES017452) to LZ, and Excellent Doctoral Dissertation Cultivation Grant from Central China Normal University (2013YBYB67) to CW.

Abbreviations:

- BZ

benzene

- BM

bone marrow

- BFU-E

burst-forming unit-erythroid

- bw

body weight

- CBC

complete blood counts

- CMP

common myeloid progenitor

- CSF

colony stimulating factor

- EP

erythroid progenitor

- EPO

erythropoietin

- EPOR

EPO receptor

- FA

formaldehyde

- GRA

granulocytes

- GM-CSF

granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor

- GM-CSFRα

GM-CSF receptor α

- GMP

granulocyte-monocyte progenitor

- HSC

hematopoietic stem cells

- HPC

hematopoietic progenitor cells

- HGB

hemoglobin

- IL-3

interleukin-3

- IL-3Rα

IL-3 receptor α

- LYM

lymphocytes

- MCV

mean corpuscular volume

- MEP

megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor

- MON

monocytes

- MPP

multipotent progenitor

- PLT

platelets

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RBC

red blood cells

- WBC

white blood cells

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution or practice at which the studies were conducted. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. The manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- ASTM (1984) Standard Test Method for Estimating Sensory Irritancy of Airborne Chemicals, Designation E981–84 American Society for Testing and Materials, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- Battisti V, Maders LD, Bagatini MD, et al. (2008) Measurement of oxidative stress and antioxidant status in acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients. Clin Biochem 41(7):511–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos A, Wever R, Roos D (1978) Characterization and quantification of the peroxidase in human monocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 525(1):37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callera F, Falcão RP (1997) Increased apoptotic cells in bone marrow biopsies from patients with aplastic anaemia. Br J Haematol 98(1):18–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova-Schmitz M, Starr TB, Heck HD (1984) Differentiation between metabolic incorporation and covalent binding in the labeling of macromolecules in the rat nasal mucosa and bone marrow by inhaled [14C]- and [3H]formaldehyde. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 76(1):26–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova M, Heck Hd A (1987) Further studies of the metabolic incorporation and covalent binding of inhaled [3H]- and [14C]formaldehyde in Fischer-344 rats: effects of glutathione depletion. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 89(1):105–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Circu ML, Aw TY (2010) Reactive oxygen species, cellular redox systems, and apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med 48(6):749–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denburg JA, van Eeden SF (2006) Bone marrow progenitors in inflammation and repair: new vistas in respiratory biology and pathophysiology. The European respiratory journal 27(3):441–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edrissi B, Taghizadeh K, Moeller BC, et al. (2013) Dosimetry of N(6)-formyllysine adducts following [(1)(3)C(2)H(2)]-formaldehyde exposures in rats. Chemical research in toxicology 26(10):1421–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried W (2009) Erythropoietin and erythropoiesis. Exp Hematol 37(9):1007–1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh JK, Heck JE, Cockburn M, Su J, Jerrett M, Ritz B (2013) Prenatal exposure to traffic-related air pollution and risk of early childhood cancers. Am J Epidemiol 178(8):1233–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulec M, Songur A, Sahin S, Ozen OA, Sarsilmaz M, Akyol O (2006) Antioxidant enzyme activities and lipid peroxidation products in heart tissue of subacute and subchronic formaldehyde-exposed rats: a preliminary study. Toxicol Ind Health 22(3):117–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck Hd A, Casanova M (1987) Isotope effects and their implications for the covalent binding of inhaled [3H]- and [14C]formaldehyde in the rat nasal mucosa. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 89(1):122–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC (2012) Monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans-formaldehyde World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer; 100(Part F):401–436 [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Hirabayashi Y (2010) Hematopoietic neoplastic diseases develop in C3H/He and C57BL/6 mice after benzene exposure: Strain differences in bone marrow tissue responses observed using microarrays. Chem Biol Interact 184(1–2):240–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin M, Patterson T, Smith TL, et al. (1990) Reduction of immune function in life stress and depression. Biol Psychiatry 27(1):22–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Hirao A, Arai F, et al. (2006) Reactive oxygen species act through p38 MAPK to limit the lifespan of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med 12(4):446–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y-Y, Sharkis SJ (2007) A low level of reactive oxygen species selects for primitive hematopoietic stem cells that may reside in the low-oxygenic niche. Blood 110(8):3056–3063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns WD, Pavkov KL, Donofrio DJ, Gralla EJ, Swenberg JA (1983) Carcinogenicity of formaldehyde in rats and mice after long-term inhalation exposure. Cancer research 43(9):4382–92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinnijenhuis AJ, Staal YC, Duistermaat E, Engel R, Woutersen RA (2013) The determination of exogenous formaldehyde in blood of rats during and after inhalation exposure. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association 52:105–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan Q, Smith MT, Tang X, et al. (2015) Chromosome-wide aneuploidy study of cultured circulating myeloid progenitor cells from workers occupationally exposed to formaldehyde. Carcinogenesis 36(1):160–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lino-dos-Santos-Franco A, Correa-Costa M, Durao A, et al. (2011) Formaldehyde induces lung inflammation by an oxidant and antioxidant enzymes mediated mechanism in the lung tissue. Toxicol Lett 207(3):278–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lino dos Santos Franco A, Damazo AS, Beraldo de Souza HR, et al. (2006) Pulmonary neutrophil recruitment and bronchial reactivity in formaldehyde-exposed rats are modulated by mast cells and differentially by neuropeptides and nitric oxide. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 214(1):35–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Zhang L, McHale CM, Hammond SK (2011) Paternal smoking and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oncol 2011:854584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K, Moeller B, Doyle-Eisele M, McDonald J, Swenberg JA (2011) Molecular dosimetry of N2-hydroxymethyl-dG DNA adducts in rats exposed to formaldehyde. Chemical research in toxicology 24(2):159–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F (2008) Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 454(7203):436–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka T, Takaki A, Ohtaki H, Shioda S (2010) Early changes to oxidative stress levels following exposure to formaldehyde in ICR mice. J Toxicol Sci 35(5):721–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale CM, Zhang L, Smith MT (2012) Current understanding of the mechanism of benzene-induced leukemia in humans: implications for risk assessment. Carcinogenesis 33(2):240–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metayer C, Zhang L, Wiemels JL, et al. (2013) Tobacco smoke exposure and the risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic and myeloid leukemias by cytogenetic subtype. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 22(9):1600–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne E, Greenop KR, Scott RJ, et al. (2012) Parental prenatal smoking and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am J Epidemiol 175(1):43–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller BC, Lu K, Doyle-Eisele M, McDonald J, Gigliotti A, Swenberg JA (2011) Determination of N2-hydroxymethyl-dG adducts in the nasal epithelium and bone marrow of nonhuman primates following 13CD2-formaldehyde inhalation exposure. Chemical research in toxicology 24(2):162–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NTP (2010) Final report on carcinogens background document for formaldehyde. Rep Carcinog Backgr Doc(10–5981):i–512 [PubMed]

- NTP (2011) 12th Report on Carcinogens. http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/?objectid=03C9AF75-E1BF-FF40-DBA9EC0928DF8B15 National Toxicology Program, Research Triangle Park, NC [Google Scholar]

- Passegue E, Jamieson CHM, Ailles LE, Weissman IL (2003) Normal and leukemic hematopoiesis: Are leukemias a stem cell disorder or a reacquisition of stem cell characteristics? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100(Supplement 1):11842–11849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pervaiz S, Taneja R, Ghaffari S (2009) Oxidative stress regulation of stem and progenitor cells. Antioxidants & redox signaling 11(11):2777–2789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pialoux V, Mounier R (2012) Hypoxia-induced oxidative stress in health disorders. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2012:940121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontel LB, Rosado IV, Burgos-Barragan G, et al. (2015) Endogenous Formaldehyde Is a Hematopoietic Stem Cell Genotoxin and Metabolic Carcinogen. Molecular cell 60(1):177–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rager JE, Moeller BC, Doyle-Eisele M, Kracko D, Swenberg JA, Fry RC (2013) Formaldehyde and epigenetic alterations: microRNA changes in the nasal epithelium of nonhuman primates. Environ Health Perspect 121(3):339–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza A, Gezer S, Mundle S, et al. (1995) Apoptosis in bone marrow biopsy samples involving stromal and hematopoietic cells in 50 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 86(1):268–276 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid A, Glass DC, Bailey HD, et al. (2011) Parental occupational exposure to exhausts, solvents, glues and paints, and risk of childhood leukemia. Cancer causes & control : CCC 22(11):1575–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL (2001) Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature 414(6859):105–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuettpelz LG, Link DC (2013) Regulation of hematopoietic stem cell activity by inflammation. Frontiers in immunology 4:204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J, Kaminker K (1962) Myeloperoxidase of the leucocyte of normal human blood. I. Content and localization. Arch Biochem Biophys 96:465–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh JH, Moore MA (1989) Hematopoietic growth factor receptors. Cytotechnology 2(4):269–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin DY, Kim GY, Li W, et al. (2009) Implication of intracellular ROS formation, caspase-3 activation and Egr-1 induction in platycodon D-induced apoptosis of U937 human leukemia cells. Biomed Pharmacother 63(2):86–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder R (2012) Leukemia and benzene. Int J Environ Res Public Health 9(8):2875–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q, Hao J, Yang L, Wang X, Gu L, Yu Y (2004) Mutagenicity of joint exposure to formaldehyde and benzene in mice. J Environ Health 21(5):323–324 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang XJ, Bai Y, Duong A, Smith MT, Li LY, Zhang LP (2009) Formaldehyde in China: Production, consumption, exposure levels, and health effects. Environ Int 35(8):1210–1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa U, Riccioni R, Diverio D, Rossini A, Lo Coco F, Peschle C (2004) Interleukin-3 receptor in acute leukemia. Leukemia 18(2):219–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson EM, Williams A, Yauk CL, Vincent R (2009) Impact of nose-only exposure system on pulmonary gene expression. Inhal Toxicol 21 Suppl 1:74–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkley CR (2011) Erythropoiesis, anemia and the bone marrow microenvironment. Int J Hematol 93(1):10–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y, Xiaokaiti Y (2009) Study of combined toxicity of formaldehyde and benzene on DNA damage of bone marrow cells of female mice. Journal of Xinjiang Medical University 32(7):856–860 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang HX, Wang XY, Zhou DX, et al. (2013) Effects of low-dose, long-term formaldehyde exposure on the structure and functions of the ovary in rats. Toxicol Ind Health 29(7):609–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yahata T, Takanashi T, Muguruma Y, et al. (2011) Accumulation of oxidative DNA damage restricts the self-renewal capacity of human hematopoietic stem cells. Blood 118(11):2941–2950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X, Ji ZY, Wei CX, et al. (2013) Inhaled formaldehyde induces DNA-protein crosslinks and oxidative stress in bone marrow and other distant organs of exposed mice. Environ Mol Mutagen 54(9):705–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi J-Y, Yoon B-I (2008) Benzene-induced hematotoxicity and myelotoxicity by short-term repeated oral administration in mice. Lab Anim Res 24:99–103 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang CC, Sadek HA (2014) Hypoxia and metabolic properties of hematopoietic stem cells. Antioxidants & redox signaling 20(12):1891–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zhu F, Yin L, Pu Y (2010a) Combined genotoxicity of benzene and formaldehyde co-exposure in BALB/c mice. Carcinogenesis, Teratogenesis, and Mutagenesis 22(4):308–311 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Tang X, Rothman N, et al. (2010b) Occupational exposure to formaldehyde, hematotoxicity, and leukemia-specific chromosome changes in cultured myeloid progenitor cells. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 19(1):80–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LP, Freeman LEB, Nakamura J, et al. (2010c) Formaldehyde and leukemia: epidemiology, potential mechanisms, and implications for risk assessment. Environ Mol Mutagen 51(3):181–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Yuan F, Liu X, et al. (2010d) Genotoxicity of formaldehyde and benzene joint inhalation on bone-marrow cells of male mice. J Environ Occup Med 27(5):295–296 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liu X, McHale C, et al. (2013) Bone marrow injury induced via oxidative stress in mice by inhalation exposure to formaldehyde. PLoS One 8(9):e74974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, McHale CM, Liu X, Yang X, Ding S, Zhang L (2016) Data on megakaryocytes in the bone marrow of mice exposed to formaldehyde. Data in brief 6:948–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F-L, Zhang W-G, Wei Y-C, et al. (2010) Involvement of oxidative stress in the relapse of acute myeloid leukemia. J Biol Chem 285(20):15010–15015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.