Abstract

Background:

There is growing interest in the role of childhood adversities, including parental death and separation, in the etiology of psychotic disorders. However, few studies have used prospectively-collected data to specifically investigate parental separation across development, or assessed the importance of duration of separation, and family characteristics.

Methods:

We measured three types of separation not due to death: maternal, paternal, and from both parents, across ages 1–15 among a cohort of 985,058 individuals born in Denmark 1971–1991 and followed through 2011. Associations with narrowly- and broadly- defined schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in the psychiatric register were assessed in terms of separation occurrence, age of separation, and number of years separated. Interactions with parental history of mental disorder were assessed.

Results:

Each type of separation was associated with all three outcomes, adjusting for age, sex, birth period, calendar year, family history of mental disorder, urbanicity at birth, and parental age. Number of years of paternal separation was positively associated with both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Associations between separation from both parents and schizophrenia were stronger when separation occurred at later ages, while those with bipolar disorder remained stable across development. The first occurrence of paternal separation appeared to increase risk more when it occurred earlier in childhood. Associations differed according to parental history of mental disorder, although in no situation was separation protective.

Conclusions:

Effects of parental separation may differ by type, developmental timing, and family characteristics. These findings highlight the importance of considering such factors in studies of childhood adversity.

Introduction

There has been a recent resurgence of interest in the role of childhood adversity in the etiology of psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Etain et al., 2008, Varese et al., 2012). Adverse experiences may interfere with the development of a number of processes, including formation of the stress-response system, attachment, and cognition (Bentall and Fernyhough, 2008, Phillips et al., 2006). One adverse experience that has received some attention in this regard is parental loss during childhood. Although parental loss has been widely studied as a risk factor for depression (e.g., Crook and Eliot, 1980, Harris et al., 1986, Kendler et al., 1992, Kendler et al., 2002), studies of its association with psychotic disorders are fewer. Parental loss has been defined in these studies as parental death (Clarke et al., 2013, Laursen et al., 2007, Mortensen et al., 2003, Tsuchiya et al., 2005), parent-child separation (Anglin et al., 2008, Räikkönen et al., 2011, Walker et al., 1981), or a combination thereof (Agid et al., 1999, Erlenmeyer-Kimling et al., 1991, Furukawa et al., 1998, Furukawa et al., 1999, Mallett et al., 2002, Morgan et al., 2009, Morgan et al., 2007, Pert et al., 2004, Pfohl et al., 1983, Rubino et al., 2009, Stilo et al., 2012). The distinction between parental death and separation is an important one, as the two exposures may reflect distinct experiences that have different implications for mental health. Some have suggested that parent-child separation may be more psychologically detrimental to adolescents than parental death (Canetti et al., 2000). There is also evidence that the two exposures are not associated with the same mental health outcomes in adulthood (Kendler et al., 1992, Kendler et al., 1996). Studies that have estimated associations specifically between separation and psychotic disorders have reported mixed results (Agid et al., 1999, Anglin et al., 2008, Furukawa et al., 1998, Furukawa et al., 1999, Horesh et al., 2011, Mallett et al., 2002, Morgan et al., 2009, Morgan et al., 2007, Räikkönen et al., 2011, Rubino et al., 2009, Stilo et al., 2012).

Little evidence exists regarding factors that might modify any effect of parental separation on psychosis risk. In animal studies, the developmental timing of separation, as well as its duration, are important determinants of the types of effects observed and whether they persist into adulthood (Marco et al., 2009, Nishi et al., 2012, Parker and Maestripieri, 2011). Research indicates that timing and duration of childhood adversity are also important in humans (Fisher et al., 2010, Kaplow and Widom, 2007, Pesonen et al., 2010), and that stressors occurring across childhood and adolescent development may influence risk for psychotic disorders (Laursen et al., 2007, Mortensen et al., 2003). However, the few epidemiologic studies that have investigated the influence of age and duration of parental separation in relation to psychosis have yielded mixed results (Agid et al., 1999, Anglin et al., 2008, Morgan et al., 2007, Räikkönen et al., 2011). Moreover, researchers have long recognized that family and parental characteristics shape the mental health effects of parental separation (Harris et al., 1986, Kendler et al., 1992, Tennant, 1988). One characteristic that may be particularly relevant for parent-child separation is the presence of mental disorder in family members (Tennant, 1988). However, few previous studies of the association between parental separation and psychotic disorders have included information on parental mental health (Agid et al., 1999, Anglin et al., 2008, Mallett et al., 2002, Morgan et al., 2007, Walker et al., 1981).

A further limitation of many epidemiologic studies of parental separation, and childhood adversity more broadly, is the need to measure adverse experiences via retrospective recall (Morgan and Fisher, 2007, Scott et al., 2010). Reliance upon recall may introduce bias if individuals with and without disorder recall childhood experiences differently (Susser and Widom, 2012). Few studies of parental separation and psychosis used a prospective, independent measure of exposure (Anglin et al., 2008, Räikkönen et al., 2011). To our knowledge, no population-based studies have used prospective data to estimate associations of maternal and paternal separation across the course of development with risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in adulthood.

The goal of this study was to characterize associations of parent-child separation with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder using prospectively-collected exposure measures. We investigated three types of separations occurring across development, paternal, maternal, and those from both parents, with respect to age and number of years separated. We included information regarding mental disorder in family members to assess both confounding and modification of associations between parental separation and psychotic disorder. We estimated associations with three outcomes, narrowly-defined schizophrenia, broadly-defined schizophrenia (including schizoaffective disorder), and bipolar disorder, to assess the degree of risk factor specificity or overlap. This study was conducted among a nation-wide, population-based cohort for which prospectively- and independently-collected exposure data were available from birth.

Method

Study population

We established a population-based cohort among those born in Denmark between January 1st, 1971, and June 30, 1991 using the Danish Civil Registration System (Pedersen et al., 2006). This registry contains continuously-updated information on all Danish residents, including date of birth, sex, identity of parents and siblings, place of birth and residence, and vital status. We included individuals if the identity of both legal parents was known and the individual was alive and residing in Denmark on his or her 15th birthday. Because immigrant status has been associated with both parental separation and psychosis (Cantor-Graae and Pedersen, 2013, Morgan et al., 2007), we excluded individuals with parents born outside Denmark. These requirements resulted in a cohort of 1,110,676 individuals. We conceptualized parent-child separation as a distinct exposure from both parental death and being born into a single parent household. We therefore further excluded 125,618 individuals who did not live with both parents at birth or who experienced a parental death before their 15th birthday. The final study cohort consisted of 985,058 individuals.

Psychiatric diagnoses and family history

The study population and their parents and siblings were linked to the Danish Psychiatric Central Register using a unique personal identifier (Mors et al., 2011). This registry contains information on all admissions to inpatient psychiatric facilities since 1969, and outpatient and emergency room visits since 1995. Diagnoses were made by treating clinicians and assigned according to the International Classification of Diseases, 8th revision (ICD-8; World Health Organization, 1967) prior to 1994 and the ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1992) from 1994 onwards. We used two classifications of schizophrenia: narrow schizophrenia was identified by ICD-8 code 295 (excluding 295.79) or ICD-10 code F20 and broad schizophrenia was identified by ICD-8 codes 295, 297, and 298.39, or ICD-10 codes F20–F29. Bipolar disorder was identified by ICD-8 codes 296.19 and 296.39, or ICD-10 codes F30 and F31. Date of onset was defined as the first day of the first visit during which the diagnosis was assigned. Recent validity studies have found good agreement between registry diagnoses of schizophrenia and those generated from case note review (Jakobsen et al., 2005, Uggerby et al., 2013).

Parental and sibling psychiatric diagnoses were measured over the course of follow-up. For schizophrenia outcomes, family members were classified with the following order of precedence: narrow schizophrenia, broad schizophrenia, any other mental disorder, or none. For bipolar disorder, family members were classified with the following order of precedence: bipolar disorder, another affective disorder (ICD-8 296 (excluding 296.19 and 296.39), 298.09, 298.19, 300.49 and 301.19 or ICD-10 F32–F39), any other mental disorder, or none. For interaction tests, a binary parental history variable indicated whether either parent had any psychiatric diagnosis.

Parental separation

Residential addresses have been continually recorded in the CRS since 1971. One permanent address is recorded per person for a given time period, and addresses are updated without deleting the prior information. Danish residents are required by law to inform the authorities of permanent address changes within 5 days; failure to do so jeopardizes access to schools, healthcare, and other government services such as unemployment and sickness benefits. In addition, residential information in the CRS is used daily by the Danish administrative system and errors are corrected whenever they are encountered (Pedersen et al., 2006). Municipality and street codes were used to determine whether each individual lived with his/her parents on each birthday from birth through age 15. Separation status at each age was classified as: no separation (living with both parents), paternal separation (living with mother but not father), maternal separation (living with father but not mother) separation from both parents (living with neither parent), or missing (unknown or residing abroad). Less than 1% of separation statuses were missing for any given age.

Binary measures indicated whether each separation type was observed at any point during the exposure period. Cumulative exposure to each separation type measured the number of years during which that status was observed (consecutive or non-consecutive), categorized as 0, 1–5, 6–10, or 11–15 years. The age of first separation was calculated for each separation type using the earliest age at which it was observed, ignoring missing statuses.

Other measures

Age, birth period, sex, parental age, and urbanicity at birth were obtained from the registry. Categorical age bands spanned one to five years. Birth period was categorized as 1971–1980, 1981–1985, and 1985–1991. Maternal and paternal age at birth were categorized as <22, 22–25, 26–29, 30–34, and 35 or older. Urbanicity at birth was classified according to previous studies (Mortensen et al., 1999).

Study design and analysis

Data were analyzed prospectively. Follow-up began on the 15th birthday and ended at disorder onset, death, emigration from Denmark, or December 31, 2011, whichever came first. Age, calendar year, and family history of mental disorder were measured over follow-up and were time-varying, while birth period, sex, parental age at birth, urbanicity at birth, and parental separation were treated independently of time. Log-linear Poisson regression, implemented in the GENMOD procedure of SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, 2008), was used to estimate relative risks (RRs) with likelihood ratio-based 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and to conduct likelihood ratio tests, approximating Cox regression (Laird and Olivier, 1981). Score tests were used to check for overdispersion (Breslow, 1996). All relative risks were controlled for birth period, age, sex, their interaction, calendar year, urbanicity at birth, parental age, and family history of mental disorder.

This study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency.

Results

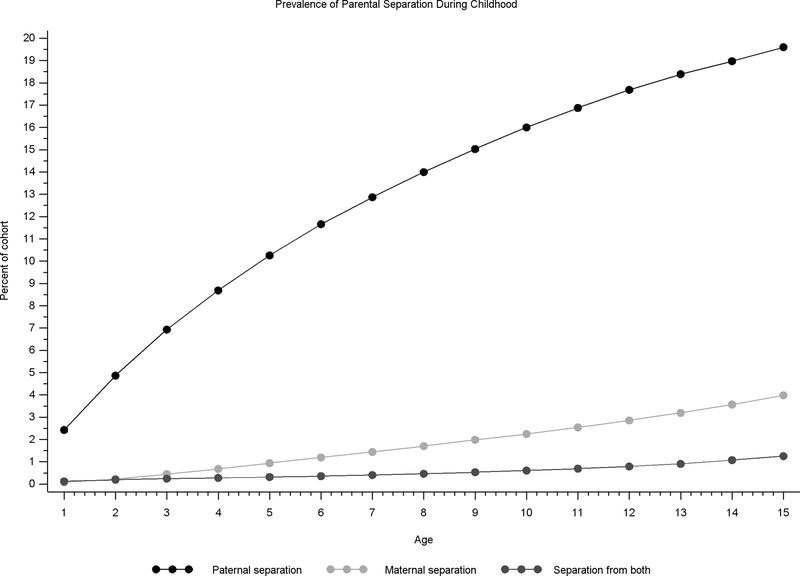

Among 985,058 individuals born 1971–1991 and followed through 2011, there were 6,469 cases of narrow schizophrenia, 11,464 cases of broad schizophrenia, and 2,821 cases of bipolar disorder over ≈15.8 million person-years of follow-up. Figure 1 depicts the proportion of cohort members living apart from their fathers, mothers, and both parents, by age. Paternal separation was the most common separation type at all ages, with 19.6% of cohort members living apart from their fathers by age 15. By design, all cohort members lived with both parents at birth.

Figure 1:

Prevalence of paternal separation (black line; blue online), maternal separation (light gray line; green online), and separation from both parents (dark gray line; red online), between ages 1 and 15, among a cohort of 985,058 individuals born in Denmark 1971–1991 who lived with both parents at birth.

Occurrence and number of years of separation

Table 1 displays RRs of each disorder for those with any separation between birth and age 15 compared to those with none. Each separation type was associated with increased risk of all three outcomes, controlling for one another. Associations of paternal and maternal separation with disorder were similar in magnitude across outcomes, with RRs ranging from 1.28 to 1.52. Separation from both parents, however, was more strongly associated with narrow and broad schizophrenia (RRs= 2.23 and 2.30, respectively) than with bipolar disorder (RR=1.39).

Table 1:

Relative risk of narrow schizophrenia, broad schizophrenia and bipolar disorder by the occurrence of any parental separation between ages 1 and 15

| Narrow Schizophrenia |

Broad Schizophrenia |

Bipolar Disorder |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Separation Type | Person-years | Cases | RR | 95% CI | Person-years | Cases | RR | 95% CI | Person-years | Cases | RR | 95% CI | |

| Paternal | No (ref) | 1180 | 3773 | 1.00 | 1177 | 6757 | 1.00 | 1181 | 1777 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 2454 | 354 | 1.52 | (1.44, 1.61) | 352 | 4255 | 1.49 | (1.42, 1.55) | 355 | 949 | 1.34 | (1.23, 1.45) | |

| Maternal | No (ref) | 1451 | 5586 | 1.00 | 1447 | 9898 | 1.00 | 1454 | 2451 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 82 | 641 | 1.28 | (1.17, 1.39) | 82 | 1114 | 1.28 | (1.20, 1.36) | 83 | 275 | 1.46 | (1.29, 1.67) | |

| Both Parents | No (ref) | 1503 | 5738 | 1.00 | 1500 | 10175 | 1.00 | 1506 | 2608 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 30 | 489 | 2.23 | (2.02, 2.47) | 30 | 837 | 2.30 | (2.13, 2.48) | 30 | 118 | 1.39 | (1.15, 1.68) | |

Note: CI = confidence interval; RR = relative risk. Person-years are per 10,000. RRs are adjusted for age, sex, birth period, calendar year, urbanicity at birth, parental age, mental disorders in parents and siblings, and other separation types. Analysis conducted among those with fully-observed separation status and includes 6,227 cases of narrow schizophrenia, 11,012 cases of broad schizophrenia, and 2,726 cases of bipolar disorder over ≈15.3 million person-years.

Relative Risks according to the total number of years separated are displayed in Table 2. Likelihood ratio tests revealed that number of years of separation was important above and beyond any separation for paternal separation only (Table 2, footnote). Risk of narrow and broad schizophrenia increased with the number of years of paternal separation, while risk of bipolar disorder was higher for those with 11–15 years of paternal separation compared to 1–5 or 6–10 years. RRs were similar across outcomes for those with 11–15 years of paternal separation (range: 1.61–1.77).

Table 2:

Relative risk of narrow schizophrenia, broad schizophrenia and bipolar disorder by cumulative duration of parental separation between ages 1 and 15

| Narrow Schizophreniaa |

Broad Schizophreniab |

Bipolar Disorderc |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Separation Type | Years separated | Person-years | Cases | RR | 95% CI | Person-years | Cases | RR | 95% CI | Person-years | Cases | RR | 95% CI |

| Paternal | 0 (ref) | 1180 | 3773 | 1.00 | 1177 | 6757 | 1.00 | 1181 | 1777 | 1.00 | |||

| 1–5 | 130 | 808 | 1.36 | (1.25, 1.47) | 129 | 1413 | 1.34 | (1.26, 1.42) | 130 | 327 | 1.24 | (1.09, 1.40) | |

| 6–10 | 104 | 689 | 1.44 | (1.32, 1.56) | 103 | 1202 | 1.42 | (1.33, 1.51) | 104 | 247 | 1.18 | (1.03, 1.36) | |

| 11–15 | 120 | 957 | 1.77 | (1.64, 1.91) | 120 | 1640 | 1.71 | (1.61, 1.81) | 121 | 375 | 1.61 | (1.43, 1.81) | |

| Maternal | 0 (ref) | 1451 | 5586 | 1.00 | 1447 | 9898 | 1.00 | 1454 | 2451 | 1.00 | |||

| 1–5 | 52 | 413 | 1.33 | (1.20, 1.47) | 52 | 698 | 1.28 | (1.19, 1.39) | 53 | 177 | 1.53 | (1.30, 1.78) | |

| 6–10 | 21 | 164 | 1.38 | (1.17, 1.61) | 21 | 298 | 1.45 | (1.28, 1.63) | 21 | 63 | 1.44 | (1.11, 1.84) | |

| 11–15 | 9 | 64 | 1.29 | (1.00, 1.64) | 9 | 118 | 1.37 | (1.14, 1.64) | 9 | 35 | 1.85 | (1.30, 2.56) | |

| Both Parents | 0 (ref) | 1503 | 5738 | 1.00 | 1500 | 10175 | 1.00 | 1506 | 2608 | 1.00 | |||

| 1–5 | 22 | 371 | 2.31 | (2.07, 2.58) | 21 | 642 | 2.38 | (2.19, 2.59) | 22 | 82 | 1.31 | (1.03, 1.63) | |

| 6–10 | 4 | 74 | 2.12 | (1.66, 2.66) | 4 | 125 | 2.20 | (1.82, 2.62) | 4 | 18 | 1.45 | (0.87, 2.24) | |

| 11–15 | 4 | 44 | 2.31 | (1.68, 3.08) | 4 | 70 | 2.19 | (1.71, 2.76) | 4 | 18 | 2.27 | (1.37, 3.50) | |

Note: CI = confidence interval; RR = relative risk. Person-years are per 10,000. RRs are adjusted for age, sex, birth period, calendar year, urbanicity at birth, parental age, mental disorders in parents and siblings, and other separation types. Analysis conducted among those with fully-observed separation status and includes 6,227 cases of narrow schizophrenia, 11,012 cases of broad schizophrenia, and 2,726 cases of bipolar disorder over ≈15.3 million person-years.

Likelihood ratio tests (LRTs) for number of years of separation vs. ever/never (df=2): paternal: χ2=32.69, p>.001; maternal: χ2=0.10, p=.950; both: χ2=1.53, p=.464.

LRTs for number of years of separation vs. ever/never (df=2): paternal: χ2=47.55, p<.001; maternal: χ2=2.49, p=.277; both: χ2=3.14, p=.208.

LRTs for number of years of separation vs. ever/never (df=2): paternal: χ2=17.28, p<.001; maternal: χ2=1.61, p=.447; both: χ2=3.61, p=.164.

Separation status by age

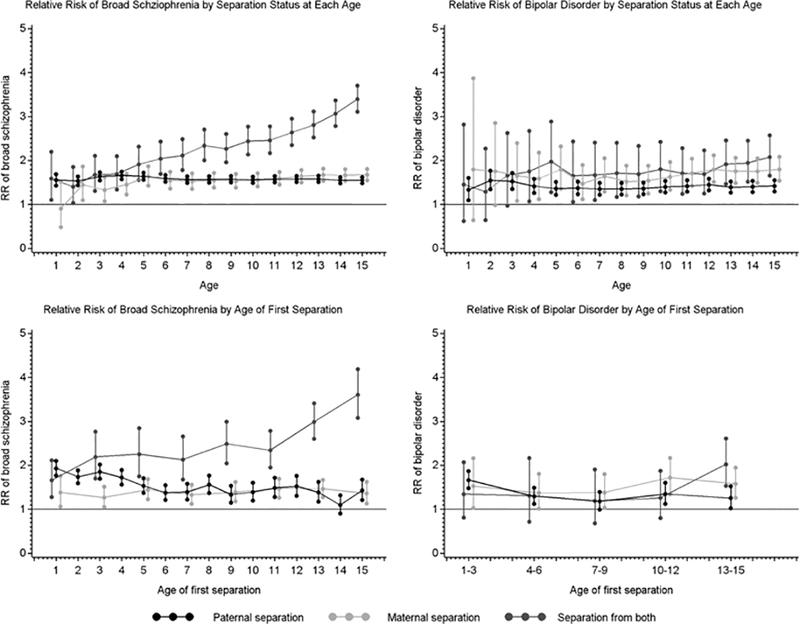

We first estimated associations with separation status by age to assess whether risk associated with living apart from parents changed with age. The top panel of Figure 2 depicts RRs associated with separation status for each age 1–15, compared to those living with both parents at that age, disregarding separation status at other ages. Because results for narrow and broad schizophrenia were similar, only those for broad schizophrenia are displayed (narrow schizophrenia results available in supplement). Each type of separation was associated with increased risk of broad schizophrenia at all ages, with the exception of maternal separation at age 1. RRs of broad schizophrenia appeared stable across age for maternal and paternal separation, while RRs for separation from both parents increased with age. Each separation type was also associated with bipolar disorder across the range of ages, with minor exceptions related to early separation. RRs of bipolar disorder for all three separation types appeared relatively stable across age.

Figure 2:

Relative risk of broad schizophrenia (left) and bipolar disorder (right) associated with separation status (top) and age of first separation (bottom) for paternal separation (black line; blue online), maternal separation (light gray line; green online) and separation from both parents (dark gray line; red online) during each year of age. Estimated among 11,463 cases of broad schizophrenia and 2,821 cases of bipolar disorder over ≈15.7 million person-years and adjusted for age, sex, birth period, calendar year of follow-up, history of mental disorders in mothers, fathers and siblings, urbanicity at birth and parental age.

Age of first separation

We next estimated associations with age of first separation to assess whether risk associated with the event of separation changed with age. The bottom panel of Figure 2 depicts adjusted RRs according to age of first separation, compared to those with no separations between birth and age 15. For broad schizophrenia, ages of first maternal separation and separation from both parents were grouped into 2-year bands for ages 1–14; for bipolar disorder all ages are in 3-year bands. Each separation type was entered into its own model with full adjustment. For first paternal separation, the largest RRs were observed earlier in childhood. Only for maternal separation was risk of both disorders significantly increased at all ages; RRs fluctuated slightly across childhood without displaying a clear trend. Relative Risks of broad schizophrenia associated with first separation from both parents showed a marked increase with age, while for the corresponding RRs for bipolar disorder this pattern was much less pronounced.

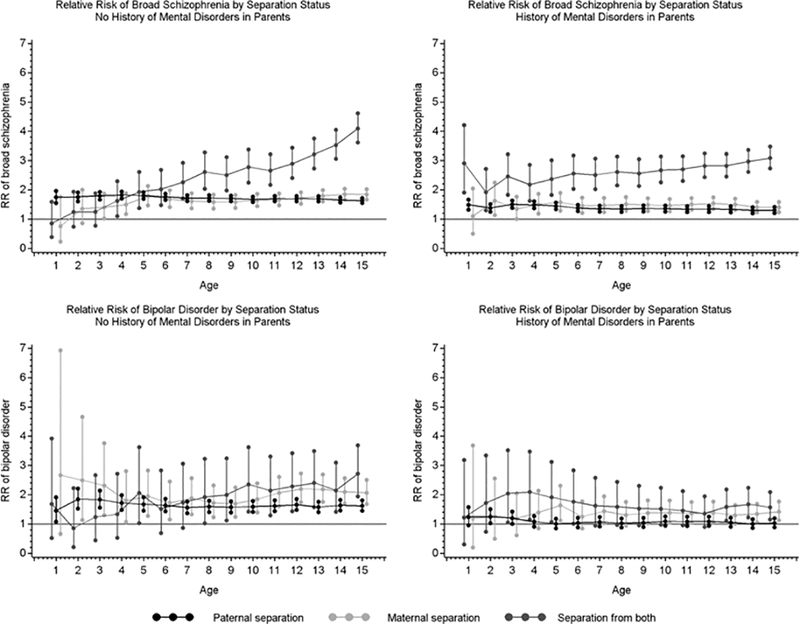

Interaction with parental history of mental disorder

Figure 3 displays adjusted associations of separation status with broad schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, by parental history of psychiatric diagnosis (note the difference in scale relative to Figure 2). Significant interactions were detected for all ages for schizophrenia and ages 2–15 for bipolar disorder (likelihood ratio tests not shown). For maternal and paternal separation, all significant differences indicated that the increase in risk associated with separation was less when parental history was present compared to when it was absent. However, these reductions were small and no associations were reduced far enough to indicate a protective effect of separation when parental history was present. For separation from both parents, the trend of increasing RR of broad schizophrenia with age was apparent only under the absence of parental history. When parental history was present, relative risks appeared higher in early childhood and more stable across development. Associations for first separation, by parental history of psychiatric diagnosis, are available in the supplement.

Figure 3:

Relative risk of broad schizophrenia (top) and bipolar disorder (bottom) associated with paternal separation status (black line; blue online), maternal separation status (light gray line; green online) and separation from both parents (dark gray line; red online) during each year of age, under the absence (left) and presence (right) of parental history of mental disorder. Estimated among 11,463 cases of broad schizophrenia and 2,821 cases of bipolar disorder over ≈15.7 million person-years and adjusted for age, sex, birth period, calendar year of follow-up, history of mental disorders in siblings, urbanicity at birth and parental age.

Discussion

In a nation-wide cohort for whom prospectively- and independently-collected information on parent-child separation was available from birth, we found that separation from parents during childhood was associated with increased risk of psychotic disorders. Maternal separation, paternal separation, and separation from both parents were each associated with elevated risk of narrowly-defined schizophrenia, broadly-defined schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Associations were present after adjustment for other separation types, family history of mental disorders, parental age, and urbanicity at birth. These results are consistent with previous studies documenting associations between parental separation and psychotic disorders (Anglin et al., 2008, Mallett et al., 2002, Morgan et al., 2009, Morgan et al., 2007, Räikkönen et al., 2011, Rubino et al., 2009) and indicate that these associations are not entirely attributable to recall bias. Our associations were somewhat smaller than some reported previously (Morgan et al., 2007, Räikkönen et al., 2011), which may be due to methodological differences. Morgan et al. (2007) reported stronger associations for maternal and paternal separation when separations were restricted to those resulting from family breakdown that lasted at least one year. Räikkönen et al. (2011) reported slightly stronger associations for separation from both parents when restricting to those from an upper socioeconomic background. Overall, our findings corroborate the results of other studies using prospective data that indicate an etiologic role of childhood adversity in psychosis (Laursen et al., 2007, Mortensen et al., 2003, Räikkönen et al., 2011, Scott et al., 2010).

Greater total years of paternal separation was associated with slightly greater risk of both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Previous studies of psychosis have not reported on the importance of duration for paternal separation specifically. However, Anglin et al. (2008) found that duration of maternal separation before age 2 was positively associated with the trajectory of schizotypal symptoms from age 9 to 39. To confirm that total years of separation in our study was not simply a proxy for earlier first paternal separation, we repeated the likelihood ratio test comparing only those who were first separated from their fathers at a young age to those who were never separated. The association between number of years separated and each outcome persisted in these analyses (not shown). Greater total years of paternal separation in our study could also indicate prolonged exposure to other early childhood stressors such as economic hardship (Werner et al., 2007, Wicks et al., 2005).

We considered two possible forms of developmental sensitivity to parental separation: sensitivity to the state of being separated (separation status), and sensitivity to the event of separation (age of first separation). We generally found that associations for first separation displayed more change across development than did associations for separation status, which could imply a greater degree developmental sensitivity to the stress associated with the event of separation. This was most evident for paternal separation; there appeared to be greater sensitivity earlier in childhood when considering first separations (Figure 2, bottom panel), while there was little developmental change when considering separation status (Figure 2, top panel). This may be because as the cohort ages, separation status associations become diluted by the addition of separations that confer less risk because they occur later and are therefore necessarily shorter in duration. In addition, the reference group for each separation status association includes those with prior and subsequent separations. Overall, we interpret our results to indicate that paternal separations may be associated with greater risk when they occur early.

Maternal separation and separation from both parents each showed different age-related patterns of risk than that of paternal separation. Risk ratios associated with maternal separation were relatively stable across age for both outcomes, possibly indicating a wide developmental window of vulnerability that is general rather than specific. In contrast, risk ratios associated with separation from both parents tended to increase with age, implying greater vulnerability during late childhood and adolescence. However, the magnitude of this increase was greater for schizophrenia than for bipolar disorder, suggesting some specificity of effect. This mirrors the stronger association with schizophrenia compared to bipolar disorder presented in Table 1.

Our results indicate risk factor overlap between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder with respect to maternal and paternal separation, implying mechanisms that are relevant to both disorders. Stressful experiences in early childhood hold theoretical importance for the development of psychological processes such as attachment and emotion regulation (Anglin et al., 2008, Morris et al., 2007, Woodward et al., 2000). Early stressors can also affect programming of the HPA axis (Tottenham and Sheridan, 2009), and a number of studies have demonstrated differences in HPA axis function in adults who experienced childhood parental loss (Bloch et al., 2007, Kumari et al., 2012, Nicolson, 2004, Pesonen et al., 2010, Tyrka et al., 2008). HPA function, in turn, is linked to dopamine function (Walker et al., 2008) and implicated in the pathogenesis of bipolar disorder (Daban et al., 2005). In contrast to maternal and paternal separation, separation from both parents appeared more strongly associated with schizophrenia compared to bipolar disorder and during adolescence compared to early childhood. Adolescence is a period of rapid brain development that has long held importance in neurodevelopmental models of schizophrenia (Andersen, 2003, Feinberg, 1983). The frontal cortex continues to develop during adolescence and may be especially sensitive to stressors experienced during this time (Lupien et al., 2009). Abilities that are impaired in schizophrenia, such as executive function and social cognition (Freedman and Brown, 2011, Penn et al., 2008), also continue to develop during adolescence, and are placed under increasing demand as adolescents face the challenges of emerging adulthood (Blakemore and Choudhury, 2006, Paus, 2005). The potential for different developmental pathways to disorder is consistent with prior research indicating that the association of abuse with psychosis differs according to the perpetrator and timing during childhood (Fisher et al., 2010) and highlights the potential importance of considering the developmental timing of adversity in relation to adult mental health.

We found evidence for effect modification of parental separation according to history of mental disorder in parents. To our knowledge, this is the first study of parental separation and psychotic disorder to test for interaction with parental mental disorder. While our results require replication, they underscore the potential importance of family characteristics and context in shaping the effects of family-based exposures (e.g., Tyrka et al., 2008). For example, in a 20-year follow-up study of offspring of depressed and non-depressed parents, family discord was more strongly associated with mental disorder among offspring of non-depressed parents (Nomura et al., 2002, Pilowsky et al., 2006). In this study we are unable to differentiate between the genetic liability associated with family history of disorder and the experience of living with a parent with a mental disorder. It is also important to keep in mind that our estimates are generated from a multiplicative model, and the direction of interaction estimates depends on the type of model used (Zammit et al., 2010). Nevertheless, the higher risk associated with separation from both parents early in childhood when parental mental disorder is present is striking. It raises questions about the implications of separation from both parents under each circumstance. One possibility is that when parental mental disorder is present, separations from both parents are more likely to result in the child being placed in institutional or foster care. A recent study found that Danish children have about a 6-fold risk of entering the out-of-home care system before age 3 if their mother has a psychiatric history, and about a 3-fold risk if their father has a psychiatric history (Ubbesen et al., 2013). Although we cannot verify this possibility in the current study, it is consistent with previous work emphasizing the importance of parental care after separation (Harris et al., 1986). Overall, the higher relative risks of schizophrenia observed in this study for children separated from both parents speaks to their status as a potentially vulnerable subgroup.

Strengths and limitations

This study carries some limitations that should be kept in mind when interpreting the results. As mentioned above, separation may be a proxy for other childhood experiences such as parental discord or family breakdown, poor caretaking, economic disadvantage, or childhood trauma (Harris et al., 1986, Kendler et al., 1992, Morgan et al., 2009, Read et al., 2005, Rutter, 1971). Isolating effects of specific forms of adversity, which often cluster together (Kessler et al., 2010), requires detailed information on family characteristics that were unfortunately not available in the current study. However, to the extent that such exposures are associated with psychiatric diagnoses in parents, they do not appear to fully explain the associations documented here. We lacked information on socioeconomic status, which could possibly confound or modify separation associations (Räikkönen et al., 2011). Outcome measurement relied on clinician diagnosis, and we lacked symptom-level or clinical information that would allow us to eliminate any effect of protopathic bias (i.e., reverse causation; Salas et al., 1999). We lacked information on reasons for parent-child separation, which would have enabled more refined exposure measurement. Some age-specific associations with bipolar disorder may have had limited power due to the low prevalence of maternal separation and separation from both parents. Additional limitations include lack of information on the whereabouts of children separated from both parents, possible missed short periods of separation due to measurement on each birthday, and possible limited generalizability of our findings.

A major strength of this study is the method of exposure measurement. Separation data was collected prospectively, independently of the outcome, and without relying on participant or parent recall. This is advantageous because of potential validity problems associated with measuring childhood experiences via retrospective report (Susser and Widom, 2012). It also allowed us to consider separations occurring across development, highlighting the importance of developmental timing. Another strength of this study is the use of a nation-wide psychiatric registry, which permitted assessment of the confounding and modifying roles of family and parental history of mental disorder. Family history is perhaps the most important confounder of environmental risk factors for psychosis, and in this study it was measured prospectively and independently of the exposure.

Conclusion

We found that parental separation during childhood is a risk factor for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder among a cohort with prospectively- and independently-collected exposure information and adjustment for family history of psychiatric disorder. We found differences in risk according to type of separation and developmental timing, highlighting the importance of considering these factors in studies of the long-term mental health effects of childhood adversity. We also found differences in age-related patterns of risk under the presence or absence of parental history of mental disorder, underscoring the importance of taking family characteristics into account. Characterizing adversity with respect to developmental timing and other characteristics may ultimately help elucidate pathways to adult mental disorder.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH grant 5T32MH014592); the Intramural Research Program of the NIMH; the National Institute on Drug Abuse (W.E., grant R01 026652); the Stanley Medical Research Institute (P.M. and C.P.); and The Lundbeck Foundation (P.M. and C.P).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None.

Disclaimer

This study was conducted when Diana Paksarian was with the Department of Mental Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland. She is now with the National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Maryland. The views and opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations or agencies or the U.S. government.

Results from this study were presented as a poster at the meeting of the American Psychopathological Association on March 6, 2014 in New York, NY.

Contributor Information

Diana Paksarian, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (affiliation when work was conducted), National Institute of Mental Health (current affiliation)

William W. Eaton, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public health

Preben Bo Mortensen, National Center for Register-Based Research, Center for Integrated Register-Based Research (CIRRAU), The Lundbeck Foundation Initiative for Integrative Psychiatric Research, iPSYCH.

Kathleen Ries Merikangas, National Institute of Mental Health

Carsten Bøcker Pedersen, National Center for Register-Based Research, Center for Integrated Register-Based Research (CIRRAU), The Lundbeck Foundation Initiative for Integrative Psychiatric Research, iPSYCH.

References

- Agid O, Shapira B, Zislin J, Ritsner M, Hanin B, Murad H, Troudart T, Bloch M, Heresco-Levy U & Lerer B (1999). Environment and vulnerability to major psychiatric illness: a case control study of early parental loss in major depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Molecular psychiatry 4, 163–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL (2003). Trajectories of brain development: point of vulnerability or window of opportunity? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 27, 3–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglin DM, Cohen PR & Chen H (2008). Duration of early maternal separation and prediction of schizotypal symptoms from early adolescence to midlife. Schizophrenia research 103, 143–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentall RP & Fernyhough C (2008). Social predictors of psychotic experiences: specificity and psychological mechanisms. Schizophrenia Bulletin 34, 1012–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ & Choudhury S (2006). Development of the adolescent brain: implications for executive function and social cognition. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 47, 296–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch M, Peleg I, Koren D, Aner H & Klein E (2007). Long-term effects of early parental loss due to divorce on the HPA axis. Hormones and behavior 51, 516–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow NE (1996). Generalized linear models: checking assumptions and strengthening conclusions. Statistica Applicata 8, 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Canetti L, Bachar E, Bonne O, Agid O, Lerer B, De-Nour AK & Shalev AY (2000). The impact of parental death versus separation from parents on the mental health of Israeli adolescents. Comprehensive psychiatry 41, 360–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor-Graae E & Pedersen CB (2013). Full spectrum of psychiatric disorders related to foreign migration: a Danish population-based cohort study. JAMA psychiatry 70, 427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke MC, Tanskanen A, Huttunen MO & Cannon M (2013). Sudden death of father or sibling in early childhood increases risk for psychotic disorder. Schizophrenia Research 143, 363–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook T & Eliot J (1980). Parental death during childhood and adult depression: A critical review of the literature. Psychological Bulletin; Psychological Bulletin 87, 252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daban C, Vieta E, Mackin P & Young A (2005). Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 28, 469–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlenmeyer-Kimling L, Rock D, Squires-Wheeler E, Roberts S & Yang J (1991). Early life precursors of psychiatric outcomes in adulthood in subjects at risk for schizophrenia or affective disorders. Psychiatry Research 39, 239–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etain B, Henry C, Bellivier F, Mathieu F & Leboyer M (2008). Beyond genetics: childhood affective trauma in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders 10, 867–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg I (1983). Schizophrenia: caused by a fault in programmed synaptic elimination during adolescence? Journal of Psychiatric Research 17, 319–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher HL, Jones PB, Fearon P, Craig TK, Dazzan P, Morgan K, Hutchinson G, Doody GA, McGuffin P & Leff J (2010). The varying impact of type, timing and frequency of exposure to childhood adversity on its association with adult psychotic disorder. Psychological Medicine 40, 1967–1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman D & Brown AS (2011). The developmental course of executive functioning in schizophrenia. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience 29, 237–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T, Mizukawa R, Hirai T, Fujihara S, Kitamura T & Takahashi K (1998). Childhood parental loss and schizophrenia: evidence against pathogenic but for some pathoplastic effects. Psychiatry Research 81, 353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa TA, Ogura A, Hirai T, Fujihara S, Kitamura T & Takahashi K (1999). Early parental separation experiences among patients with bipolar disorder and major depression: a case–control study. Journal of Affective Disorders 52, 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris T, Brown GW & Bifulco A (1986). Loss of parent in childhood and adult psychiatric disorder: the role of lack of adequate parental care. Psychological Medicine 16, 641–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horesh N, Apter A & Zalsman G (2011). Timing, quantity and quality of stressful life events in childhood and preceding the first episode of bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders 134, 434–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen KD, Frederiksen JN, Hansen T, Jansson LB, Parnas J & Werge T (2005). Reliability of clinical ICD-10 schizophrenia diagnoses. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 59, 209–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow JB & Widom CS (2007). Age of onset of child maltreatment predicts long-term mental health outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 116, 176–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC & Eaves LJ (1992). Childhood parental loss and adult psychopathology in women: a twin study perspective. Archives of General Psychiatry 49, 109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Neale MC, Prescott CA, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Corey LA & Eaves LJ (1996). Childhood parental loss and alcoholism in women: a causal analysis using a twin-family design. Psychological Medicine 26, 79–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Sheth K, Gardner CO & Prescott CA (2002). Childhood parental loss and risk for first-onset of major depression and alcohol dependence: the time-decay of risk and sex differences. Psychological Medicine 32, 1187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alhamzawi AO, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Benjet C, Bromet E, Chatterji S, de Girolamo G, Demyttenaere K, Fayyad J, Florescu S, Gal G, Gureje O, Haro JM, Hu CY, Karam EG, Kawakami N, Lee S, Lepine JP, Ormel J, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Tsang A, Ustun TB, Vassilev S, Viana MC & Williams DR (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. British Journal of Psychiatry 197, 378–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari M, Head J, Bartley M, Stansfeld S & Kivimaki M (2012). Maternal separation in childhood and diurnal cortisol patterns in mid-life: findings from the Whitehall II study. Psychological Medicine 1, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird N & Olivier D (1981). Covariance analysis of censored survival data using log-linear analysis techniques. Journal of the American Statistical Association 76, 231–240. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Nordentoft M & Mortensen PB (2007). A comparison of selected risk factors for unipolar depressive disorder, bipolar affective disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia from a danish population-based cohort. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 68, 1673–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR & Heim C (2009). Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 10, 434–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett R, Leff J, Bhugra D, Pang D & Zhao JH (2002). Social environment, ethnicity and schizophrenia. A case-control study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 37, 329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco EM, Adriani W, Llorente R, Laviola G & Viveros M (2009). Detrimental psychophysiological effects of early maternal deprivation in adolescent and adult rodents: altered responses to cannabinoid exposure. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 33, 498–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan C & Fisher H (2007). Environment and schizophrenia: environmental factors in schizophrenia: childhood trauma—a critical review. Schizophrenia Bulletin 33, 3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan C, Fisher H, Hutchinson G, Kirkbride J, Craig TK, Morgan K, Dazzan P, Boydell J, Doody GA, Jones PB, Murray RM, Leff J & Fearon P (2009). Ethnicity, social disadvantage and psychotic-like experiences in a healthy population based sample. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 119, 226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan C, Kirkbridge J, Leff J, Craig T, Hutchinson G, McKenzie K, Morgan K, Dazzan P, Doody GA, Jones P, Murray R & Fearon P (2007). Parental separation, loss and psychosis in different ethnic groups: A case-control study. Psychological Medicine 37, 495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS & Robinson LR (2007). The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development 16, 361–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mors O, Perto GP & Mortensen PB (2011). The danish psychiatric central research register. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 39, 54–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB, Melbye M, Mors O & Ewald H (2003). Individual and familial risk factors for bipolar affective disorders in Denmark. Archives of General Psychiatry 60, 1209–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB, Westergaard T, Wohlfahrt J, Ewald H, Mors O, Andersen PK & Melbye M (1999). Effects of family history and place and season of birth on the risk of schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 340, 603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolson NA (2004). Childhood parental loss and cortisol levels in adult men. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29, 1012–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi M, Noriko H, Sasagawa T & Matsunaga W (2012). Effects of early life stress on brain activity: implications from maternal separation model in rodents. General and Comparative Endocrinology 181, 306–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura Y, Wickramaratne PJ, Warner V, Mufson L & Weissman MM (2002). Family discord, parental depression, and psychopathology in offspring: ten-year follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 41, 402–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker KJ & Maestripieri D (2011). Identifying key features of early stressful experiences that produce stress vulnerability and resilience in primates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 35, 1466–1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T (2005). Mapping brain maturation and cognitive development during adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 9, 60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CB, Gøtzsche H, Møller JØ & Mortensen PB (2006). The Danish civil registration system. Danish Medical Bulletin 53, 441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn DL, Sanna LJ & Roberts DL (2008). Social cognition in schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophrenia Bulletin 34, 408–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pert L, Ferriter M & Saul C (2004). Parental loss before the age of 16 years: A comparative study of patients with personality disorder and patients with schizophrenia in a high secure hospital’s population. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 77, 403–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesonen AK, Räikkönen K, Feldt K, Heinonen K, Osmond C, Phillips DI, Barker DJ, Eriksson JG & Kajantie E (2010). Childhood separation experience predicts HPA axis hormonal responses in late adulthood: a natural experiment of World War II. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35, 758–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl B, Stangl D & Tsuang MT (1983). The association between early parental loss and diagnosis in the Iowa 500. Archives of General Psychiatry 40, 965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LJ, McGorry PD, Garner B, Thompson KN, Pantelis C, Wood SJ & Berger G (2006). Stress, the hippocampus and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: implications for the development of psychotic disorders. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 40, 725–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y & Weissman MM (2006). Family discord, parental depression, and psychopathology in offspring: 20-year follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 45, 452–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Räikkönen K, Lahti M, Heinonen K, Pesonen A-K, Wahlbeck K, Kajantie E, Osmond C, Barker DJP & Eriksson JG (2011). Risk of severe mental disorders in adults separated temporarily from their parents in childhood: The Helsinki birth cohort study. Journal of Psychiatric Research 45, 332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read J, Os J, Morrison AP & Ross CA (2005). Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: a literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 112, 330–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino IA, Nanni RC, Pozzi DM & Siracusano A (2009). Early adverse experiences in schizophrenia and unipolar depression. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 197, 65–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M (1971). Parent‐child separation: Psychological effects on the children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 12, 233–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas M, Hotman A & Stricker BH (1999). Confounding by indication: an example of variation in the use of epidemiologic terminology. American Journal of Epidemiology 149, 981–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute, I. (2008). SAS Statistical Software; Cary, NC. [Google Scholar]

- Scott KM, Smith DR & Ellis PM (2010). Prospectively ascertained child maltreatment and its association with DSM-IV mental disorders in young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry 67, 712–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stilo SA, Di Forti M, Mondelli V, Falcone AM, Russo M, O’Connor J, Palmer E, Paparelli A, Kolliakou A & Sirianni M (2012). Social Disadvantage: Cause or Consequence of Impending Psychosis? Schizophrenia Bulletin, 1288–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susser E & Widom CS (2012). Still searching for lost truths about the bitter sorrows of childhood. Schizophrenia Bulletin 38, 672–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennant C (1988). Parental loss in childhood: its effect in adult life. Archives of General Psychiatry 45, 1045–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottenham N & Sheridan MA (2009). A review of adversity, the amygdala and the hippocampus: a consideration of developmental timing. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 3, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya KJ, Agerbo E & Mortensen PB (2005). Parental death and bipolar disorder: a robust association was found in early maternal suicide. Journal of Affective Disorders 86, 151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Wier L, Price LH, Ross N, Anderson GM, Wilkinson CW & Carpenter LL (2008). Childhood parental loss and adult hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function. Biological Psychiatry 63, 1147–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubbesen MB, Petersen L, Mortensen PB & Kristensen OS (2013). Temporal stability of entries and predictors for entry into out-of-home care before the third birthday: A Danish population-based study of entries from 1981 to 2008. Children and Youth Services Review 35, 1526–1535. [Google Scholar]

- Uggerby P, Østergaard SD, Røge R, Correll CU & Nielsen J (2013). The validity of the schizophrenia diagnosis in the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register is good. Danish Medical Journal 60, A4578–A4578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varese F, Smeets F, Drukker M, Lieverse R, Lataster T, Viechtbauer W, Read J, van Os J & Bentall RP (2012). Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: a meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective-and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin 38, 661–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker E, Mittal V & Tessner K (2008). Stress and the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis in the developmental course of schizophrenia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 4, 189–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EF, Cudeck R, Mednick SA & Schulsinger F (1981). Effects of parental absence and institutionalization on the development of clinical symptoms in high‐risk children. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 63, 95–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner S, Malaspina D & Rabinowitz J (2007). Socioeconomic status at birth is associated with risk of schizophrenia: population-based multilevel study. Schizophrenia Bulletin 33, 1373–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicks S, Hjern A, Gunnell D, Lewis G & Dalman C (2005). Social adversity in childhood and the risk of developing psychosis: a national cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry 162, 1652–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward L, Fergusson DM & Belsky J (2000). Timing of parental separation and attachment to parents in adolescence: Results of a prospective study from birth to age 16. Journal of Marriage and Family 62, 162–174. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (1967). International Classification of Diseases, Eighth Revision (ICD-8). World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (1992). The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders. Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Zammit S, Owen MJ & Lewis G (2010). Misconceptions about gene-environment interactions in psychiatry. Evidence-Based Mental Health 13, 65–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.