Abstract

Observational learning occurs when an animal capitalizes on the experience of another to change its own behavior in a given context. This form of learning is an efficient strategy for adapting to changes in environmental conditions, but little is known about the underlying neural mechanisms. There is an abundance of literature supporting observational learning in humans and other primates, and more recent studies have begun documenting observational learning in other species such as birds and rodents. The neural mechanisms for observational learning depend on the species’ brain organization and on the specific behavior being acquired. However, as a general rule, it appears that social information impinges on neural circuits for direct learning, mimicking or enhancing neuronal activity patterns that function during pavlovian, spatial or instrumental learning. Understanding the biological mechanisms for social learning could boost translational studies into behavioral interventions for a wide range of learning disorders.

Introduction

Observational learning is the capacity to acquire or optimize behavior by witnessing a similar or relevant experience in another animal. Observational learning, and the more general concept of social learning, was proposed and demonstrated in humans by Albert Bandura, in an effort to bridge behaviorist and cognitive learning theories [1,2,3]. Bandura’s most famous and controversial result is the Bobo doll experiment on the social acquisition of aggressive behavior, in which children observed an adult that verbally and physically ‘attacked’ an inflatable Bobo doll. After this episode, children manifested increased aggressive behavior towards the doll, often imitating the manner in which the adult behaved [2,3,4]. Thus Bandura clearly enunciated that learning novel behaviors can rely purely on observation or direct instruction, even in the absence of classical reinforcement [1,2,3,4]. Bandura’s theory was particularly relevant to the acquisition of language, which could not be satisfactorily explained by previous behaviorist or cognitive theories [4,5].

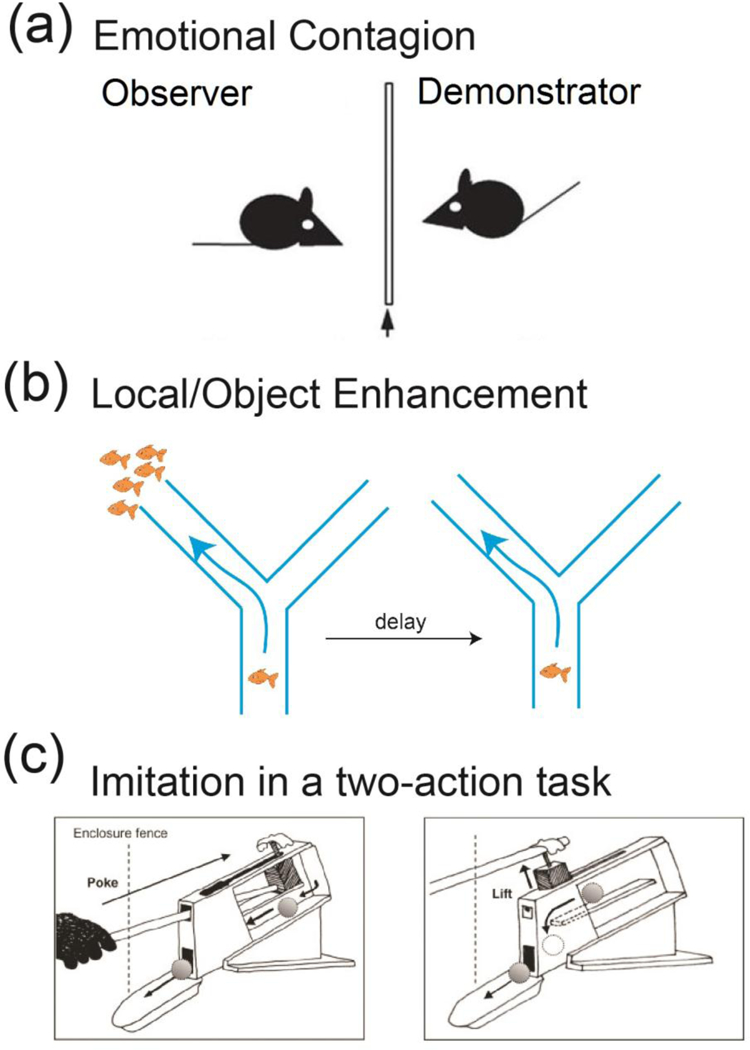

Over the last few decades, there have been an increasing number of studies documenting evidence for observational learning in non-human primates, birds, rodents, fishes and invertebrates [6,7,8,9]. The range of behaviors that can be acquired by observational learning appears to be extensive, from fear associations to vocal learning, tool use and prey catching behavior [9,10,11,12,13]. Observational learning paradigms usually consist of a model (i.e., a demonstrator or actor) that experiences an event or that executes a behavior, and an observer that voluntarily or involuntarily witnesses the behavior of the model or the consequences of the event experienced by the model. During social learning, new behaviors can be acquired by different mechanisms [14]. For certainbehaviors, like the social transmission of stress or maternal behavior in rodents, the mere social presence of a conspecific represents a sufficient trigger (Fig. 1a)[15**,16,17]. In other cases, the demonstrator simply draws the attention of the observer to a specific location (local enhancement) or a specific object (object enhancement) that will be relevant for producing the behavior (Fig. 1b) [6,18]. Imitation of actions is another variant of social learning, where the observer copies a movement or a sequence of movements, usually with the purpose of obtaining a reward or of averting punishment. Imitation has been demonstrated in a number of species by the two-action paradigm where the observer reproduces the movement of the demonstrator to obtain a reward that could have been reached by at least one other action (Fig. 1c)[12,19,20,21,22]. Finally, social learning can also refer to emulation, where the observer learns the goal of the behavior from the demonstrator but attains that goal by an action that is different from the one observed [23,24,25].

Figure 1:

Mechanisms of social learning

(a) Emotional contagion in rodents. The observer animal displays distress in response to a stimulus after detecting fear conditioning to that stimulus in another animal.

(b) Local enhancement in fish. One fish can direct the trajectory of others that observe its location during foraging.

(c) Two-action device for testing imitation in primates. The device has 2 or more ways of allowing access to reward. The observer picks the option successfully used by a demonstrator animal.

The different mechanisms of social learning likely rely on different cognitive processes: attention to the model, retention of the observed event or behavior, inferring the goal of the action, reproduction or implementation, motivation to reproduce the observed behavior, anticipation of consequences and response to feedback [2,3,14]. The detailed neural substrates for these complex processes seem to involve brain structures implicated in perception of social stimuli (e.g., sensory and insular cortex), executive control (e.g., the anterior cingulate cortex, ACC), memory formation (e.g., amygdala, hippocampus), and movement control (e.g., mirror neurons in the premotor cortex). Several recent studies suggest that social information might feed into circuits involved in more conventional direct learning or conditioning, and therefore might employ partially overlapping functional connectivity and/or synaptic plasticity mechanisms to adjust behaviors in an effective manner. We will review here some of the evidence supporting this hypothesis.

Imitation and emulation in humans and other primates

The highly evolved capacity for social learning in people is thought to contribute to the development of traditions and culture, and is at the core of several educational theories and successful pedagogical approaches [27,28]. In particular one form of observational learning, emulation, is highly developed and sophisticated in the human population. This is likely facilitated by the use of spoken and written language, a fast mean to communicate instructions [26]. However, even pre-lingual infants can acquire behaviors by emulation and by imitation [29]. The drive for this is possibly the evolutionarily selected advantage of bonding with the adult that can provide protection [30]. Adult humans and non-human primates can also form social attachments by non-verbal imitation [31,32], and this appears to be part of self-sustained behavioral loop: social interactions are generally rewarding for primates (as well as other mammals), and could play the role of a positive reinforcer in learning to imitate [31,32,33]; imitation then boost the rewarding nature of the specific interaction. Generally, in primates and other mammals, social information appears to modulate neuronal activity in structures of the classical reward pathway (ventral tegmental dopamine neurons, ventral striatum, medial prefrontal cortex), a major circuit for direct learning [34,35,36,37]. Social information is also encoded in the amygdala, a structure known to play an important role in aversion [38]. This evidence points to the neural mechanisms by which social information could substitute for reward and punishment during observational learning.

Many species of non-human primates use tools to obtain food in the wild. For example, chimpanzees manufacture appropriate sticks and use them to fish termites out of their mounds. This involves a complex sequence of actions that would be difficult to achieve by an individual through trial and error. It is more likely that chimpanzees and other primates acquire the knowledge of tool use as juveniles, by observing their parents or other adults perform the task, and then imitating the behavior [39]. This hypothesis has been tested by two-actions tasks designed for laboratory or field conditions. A common approach is using an ‘artificial fruit’, a device that has a reward at the center and one or several ‘protective’ layers that need to be removed by the animal. These layers can be removed by at least two different actions, only one of which is witnessed by the observing animal. Consistently, following observation, the method of opening the artificial fruit is the same as the one used by the demonstrator conspecific [12,19,40]. Some primates can acquire such imitative behavior from a human actor, showing that information can be transmitted not only within species but also across species [40].

An important step towards understanding the physiological substrate for action imitation was the discovery of mirror neurons in the premotor area, inferior frontal gyrus and inferior parietal lobule of macaque monkeys by Giacomo Rizzolatti and colleagues [41]. These neurons fired robustly when the monkey made a certain hand movement and also when it observed the human researcher produce the same hand movement. Similar neurons were later found to mirror mouth and facial movements [42]. It appears that mirror neurons integrate sensory and motor information, therefore it is believed that they could play an important role in understanding the action of another animal, and perhaps in the implicit learning of an action in order to reproduce it later [43]. Both of these roles would be important steps in imitative learning, however there is no clear evidence to date that mirror neurons might be implicated in observational learning or in direct motor learning [30].

Since this discovery, the existence of mirror-like neurons has been reported in birds and humans [44]. In humans, functional imaging studies described a mirror system, localized in similar brain areas as originally described in the macaque [45]. The existence of mirror systems for facial gestures in particular, generated much speculation on their possible role in the social transmission of emotional states. Humans and other primates that are capable of complex facial expressions are also experts in quickly detecting and recognizing the emotional state of another individual [9]. Often, this results in emotional contagion, where the observer assimilates the emotion perceived in another [9,16]. The neural substrate seems to involve the amygdala, a structure that is important for processing certain emotions such as fear or avoidance [9,46]. For example, if humans either observe another person experiencing negative consequences or are simply told about negative consequences, similar levels of amygdala activation occur as would be expected from directly experiencing the negative outcomes themselves [9]. If mirror neurons were important for emotional recognition and contagion, they would be expected to be functionally connected to the amygdalar complex or to subcortical structures including brainstem nuclei, the hypothalamus and the dopaminergic ventral tegmental area, important in encoding punishments or rewards. There is much to be learned about the development and plasticity of mirror neuron circuitry, an endeavor that could be helped in the future by new developments in using optogenetic and transgenic approaches in primates that show robust imitative behaviors, such as marmosets [47], or by identification of clear behavioral analogs in rodent models.

Social transmission of song production and tool use in birds

In birds, vocal imitation is the best documented form of social learning [48,49]. Juvenile songbirds such as zebra finches sequentially acquire their father’s song by listening and then reproducing it, progressing from an unstructured vocal output to a precisely structured mature song. Songbirds seem to have an internal drive for copying the song of their father (or another tutor), and they can do this when the song is played back in isolation or produced by a robot [50**].

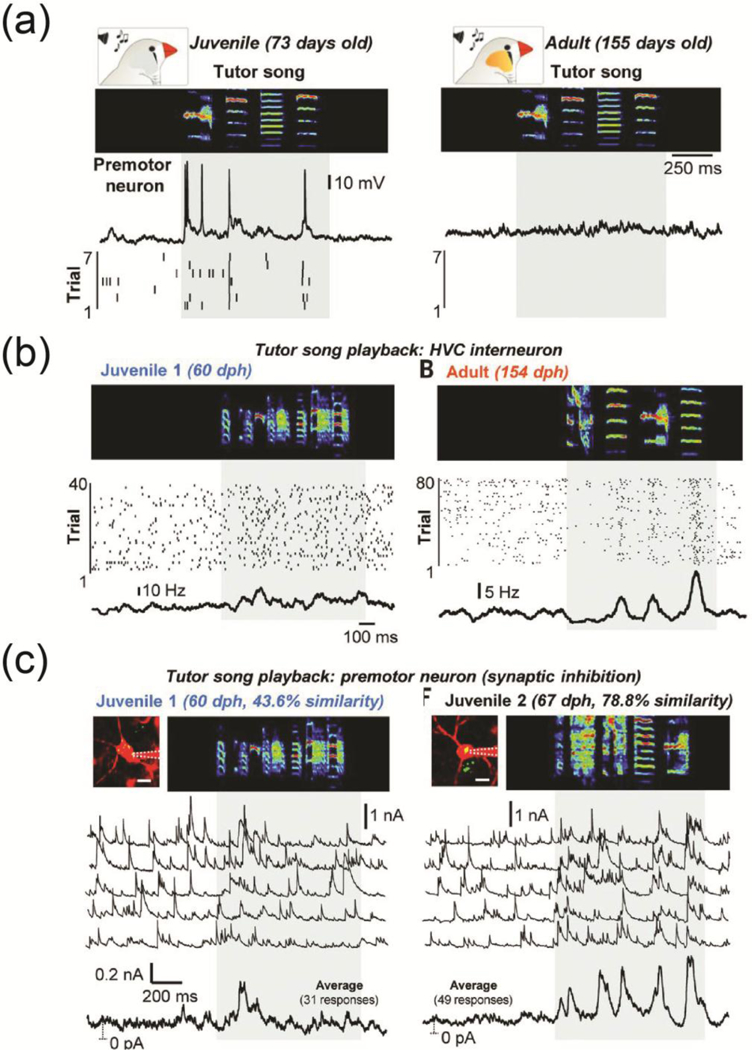

Much has been discovered about the neural and synaptic mechanisms for vocal learning in zebra finch. The HVC forebrain nucleus is important for song imitation, and acts as an interface between the sensory information received from higher order auditory areas and the motor commands generated internally [50**]. A recent study by Vallentin et al. showed that inhibitory synaptic inputs to HVC projection neurons are involved in vocal imitation [50**]. Intracellular recordings in awake birds showed that auditory cues from the tutor song evoked robust and temporally precise firing in about half of the HVC projection neurons in juvenile but not adult birds (Fig. 2a). Vallentin et al. used two-photon guided in vivo voltage-clamp recordings to reveal sensory-evoked excitatory events in projection neurons and then show that in adult birds, the played-back song recruits robust local inhibition in HVC that suppresses spiking of motor neurons. Played-back tutor song drives inhibitory cells spiking in both adult and juvenile birds, as revealed by directly recording interneuron activity (Fig. 2b). This produced temporally-precise inhibitory currents in HVC projection neurons for the parts of the song that had already been learned but not for the rest of the song that had yet to be correctly imitated (Fig. 2c). Thus, activity of inhibitory neurons was driven by social auditory cues to induce structured firing of HVC projection neurons, and appeared to orchestrate the development of social learning for song production.

Figure 2:

Vocal learning in song birds

(a) Juvenile birds have an underdeveloped song and tutor song-evoked spiking responses in HVC projection neurons. Adult birds have a mature song and HVC projection neurons are silent during played back song.

(b) Inhibitory interneurons in HVC have song-evoked spiking activity.

(c) Inhibitory currents in HVC projection neurons are temporally precise for the parts of the song that have been learned.

Birds can also learn other behaviors by observation. Chicks, for example, can learn the association between an object and an aversive taste after witnessing a single event in which a demonstrator bird pecks a bead covered in an aversive substance [51]. Budgerigars and other birds can learn to use tools in order to acquire food by observing other birds and even humans using that tool [23,52,53]. Zebra finches can acquire nest building behavior by watching streamlined videos of conspecifics building their nest [54]. The neural mechanisms for these other forms of observational learning are less well understood.

Social transmission of threat avoidance in rodents

In laboratory rodents, the best documented form of observational learning is the ability to associate a context or a stimulus with fear, after being exposed to a conspecific that experiences classical fear conditioning [9,55,56**]. To learn this behavior, the animals have to recognize fear responses in conspecifics. In mice and rats, this recognition is probably done via multiple modalities: visual (the freezing or escaping behavior of the demonstrator), auditory (distress calls produced in response to pain), and/or olfactory (pheromones that can be discharged during painful and dangerous conditions) [15**,57*]. Sterley et al. found that a mouse experiencing foot shocks secrets an anogenital pheromone that can be investigated by conspecifics [15**]. Exposure to this pheromone is sufficient to induce in the receiver mouse increased levels of circulating cortisol, and metaplasticity of excitatory synapses on corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the hypothalamus. Similarly, monogamous prairie voles can detect the emotional state of the partner after the later experienced fear conditioning to a tone [58**]. When the stressed vole freezes in response to the conditioned stimulus, its partner also freezes and experiences a surge in cortisol levels. In rats, the ultrasonic distress calls (in the 22 kHz band) seem to be capable of transmitting information about the emotional state of a conspecific that received foot shocks [57*]. It is therefore likely that witnessing the stress of a conspecific represents an aversive stimulus in rodents, similar to the unconditioned stimulus during classical fear learning. The speed with which the observer rodent acquires the novel fear association depends on how much access it has to these fear-related behavioral outcomes, and in some cases on the relationship with the demonstrator [55*,58**].

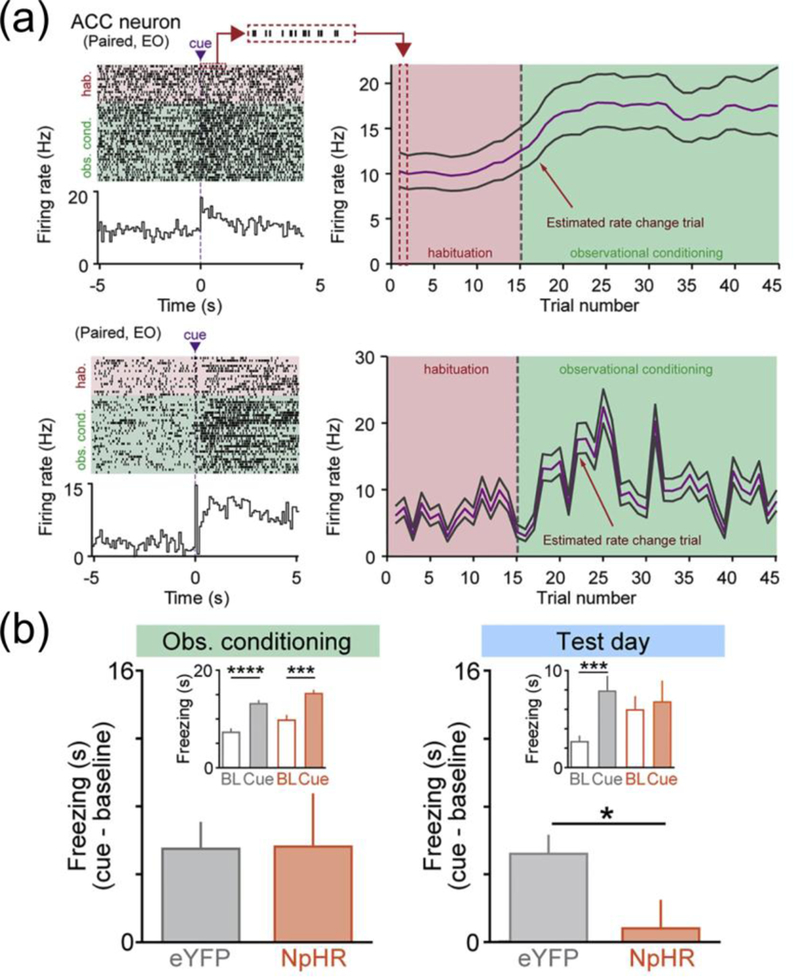

The multiple processes implicated in observational learning require complex interactions between key brain structures. In particular, in the case of observational fear learning in rodents, interactions between limbic structures seem to play an important role [55,56,58]. In the observer mouse, ACC activity is necessary for expressing freezing behavior after witnessing a conspecific that undergoes contextual or cued fear learning, and for retaining the memory of the aversive stimulus 24 hours later [55*,56**]. Immediate/early gene expression, a marker for neuronal activity, was also demonstrated in the ACC in voles during exposure to a stressed partner [58**]. This indicates that the ACC might be an important brain structure responsible for processing social stimuli. Information from ACC appears to be transmitted to the basolateral amygdala (BLA), a brain structure known to encode fear learning during classical conditioning [46]. During observational learning, the activity in ACC and BLA is synchronized in the theta range [55*]. Significantly, ACC neurons fire in response to both the cue and the shock delivered to the demonstrator mouse [56**]. Following conditioning by proxy, BLA neurons also start responding to the paired cue (Fig. 3a). This BLA plasticity during observational learning depends on direct projections received from ACC. During observational learning, BLA- projecting ACC neurons have increased firing compared to non-BLA projecting neurons, and their suppression decreases cue-evoked responses in the BLA during observational learning. When ACC to BLA projection neurons are silenced, observational learning in impaired (Fig. 3b). However, if the behavior has already been acquired by observation, inhibiting the cingulate neurons projecting to the amygdala does not impair the production of learned behavior. These experiments indicate an important role for functional connectivity between the cingulate cortex and the amygdala during observational learning of threat avoidance in rodents. It remains to be determined if ACC plays and important role in other forms of socially transmitted behavior in rodents.

Figure 3:

Social transmission of stress in rodents

(a) ACC activity induces plasticity in BLA neurons

(b) Activity of ACC→ BLA projection neurons is necessary for observational learning of fear responses.

Social-guided spatial navigation in rodents

Spatial navigation and spatial learning use place cells in the hippocampal CA1 region, and grid cells in the enthorinal cortex in rodents and in humans [59,60]. Place cells develop in response to allocentric and vestibular cues, and fire to indicate where the animal is located in space. During many types of observational learning, it is essential that the observer correctly locates the position of the demonstrator in space. How is this achieved Two recent papers identified social place cells in rats and bats, in the same part of the hippocampus where the classical place cells are located [61*,62*]. These cells fired to indicate the spatial position of a demonstrator conspecific. Remarkably, up to 13–15% of all place cells were also social place cells; conversely, about half of all social place cells could also be characterized as classical place cells. These findings indicate that there is partial overlap in neural circuitry encoding the position of self and the position of a behaviorally relevant other. Future studies should investigate if grid cells and other neurons important for spatial navigation are also capable of encoding trajectories of others, in both rodent models and humans.

Conclusions

The ability to learn from the experience of a conspecific likely provides selective advantage during evolution, and therefore should be present in many species. Indeed, in addition to the mammalian examples discussed here, there is evidence for social learning in invertebrates, whether these are highly social (eusocial insects like bees and ants) or minimally social (asocial octopuses) [63,64].

In most species studied, the neural substrate for social learning seems to at least partially overlap with neural circuits for learning from direct experience. Social information could feed into these circuits at several different ‘entry points’. For example, during fear learning, social information appears to be processed in the cortex, particularly the ACC and the insula, and from there transmitted to the amygdala where it substitutes for the representation of the unconditioned stimulus or of a secondary reinforcer. In the case of action learning such as vocal and tool use learning, social information seems to control the activity of motor neurons or of action-planning neurons. In the case of spatial navigation, social inputs can modulate the activity of place cells in the hippocampus. Future studies are required to determine how much neural circuit mechanisms for direct and observational learning resemble each other and how much they differ, and to what extent the overlap might explain efficacy of observational learning. Finally, understanding the mechanisms for observational learning could eventually refine social behavioral interventions that are currently used only minimally and empirically.

Highlights.

Many animal species can learn by observing the behavior of a conspecific

Recent studies are investigating the neural circuits for observational learning

Observational learning uses similar circuits as for other forms of learning

Social information can substitute for reward, punishment, or motor plan

Plasticity of excitatory and inhibitory synapses is likely involved

Acknowledgements

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number HD088411 and MH106744]; a Pew Scholarship, a McKnight Scholarship, and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Faculty Scholarship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Bandura A Social Learning Theory General Learning Corporation; (1971) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandura A, Ross D, Ross SA Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models. J Abnorm Psychol, 63 (1961), pp 575–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandura A, Ross D, Ross SA Vicarious reinforcement and imitative learning J Abnorm Psychol, 67 (1963), pp 527–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skinner BF Verbal Behavior Copley Publishing Group; (1947) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chomsky N A review of B. F. Skinner’s Verbal Behavior Language 35 (1959), pp 26–58 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thorpe WH Learning and Instinct in Animals Harvard Univ Press; (1963) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsson A, Ebert JP, Banaji R, Phelps EA The role of social groups in the persistence of learned fear Science, 309 (2005), pp 785–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zajonc RB Social facilitation Science, 149 (1965), pp 269–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsson A and Phelps EA Social learning of fear Nat Neurosci 10 (2007), pp 1095–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curio E Cultural transmission of enemy recognition Social learning: psychological and biological perspectives, 1988

- 11.Kavaliers M, Choleris E, Colwell DD Learning from others to cope with biting flies: social learning of fear-induced conditioned analgesia and active avoidance Behav Neurosci 115 (2001), pp. 661–674 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whiten A, Horner V, de Waal FB Conformity to cultural norms of tool use in chimpanzees Nature 437 (2005), pp. 737–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.John ER, Chesler P, Bartlett F, Victor I Observational learning in cats Science 59 (1968), pp 1489–1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galef BG and Laland KN Social learning in animals: empirical studies and theoretical models Biosci 55 (2005), pp 489–99 [Google Scholar]

- 15.**.Sterley TLTL, Baimoukhametova D D, Füzesi T T, Zurek AA, Daviu N, Rasiah NP, Rosenegger D, Bains JS Social transmission and buffering of synaptic changes after stress Nat Neurosci 21 (2018), pp 393–403In this study the authors show that an anogenital pheromone released by stressed mice is investigated by conspecific, and can induce behavioral, hormonal and electrophysiological markers for stress in the receiver mouse. Furthermore, the study demonstrates a ‘collective’ propagation of stress in mice.

- 16.Singer T, Seymour B, O’Doherty J, Kaube H, Dolan RJ, Frith CD Empathy for pain involves the affective but not sensory components of pain Science, 303 (2004), pp. 1157–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okabe S, Tsuneoka Y, Takahashi A, Ooyama R, Watarai A, Maeda S, Honda Y, Nagasawa M, Mogi K, Nishimori K, Kuroda M, Koide T, Kikusui T . Pup exposure facilitates retrieving behavior via the oxytocin neural system in female mice Psychoendocrinology, 79 (2017), pp. 20–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webster MM, Laland KN The learning mechanism underlying public information use in ninespine sticklebacks (Pungitius pungitius) J Comp Psychol, 127 (2013), pp. 154–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van de Waal E, Claidière N, Whiten A Wild vervet monkeys copy alternative methods for opening an artificial fruit Anim Cogn 18 (2015), pp 617–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vale GL, Davis SJ, Lambeth SP, Schapiro SJ, Whiten A.Galef BG and Laland KN Acquisition of a socially learned tool use sequence in chimpanzees: Implications for cumulative culture Evol Hum Behav 38(2017), pp. 635–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamon N, Neumann C, Gruber T, Zuberbühler K Kin-based cultural transmission of tool use in wild chimpanzees Sci Adv 3 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunhold T, Whiten A, Bugnyar T Video demonstrations seed alternative problem-solving techniques in wild Biol Lett, 10 (2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Auersperg AM, von Bayern AM, Weber S, Szabadvari A, Bugnyar T, Kacelnik A Social transmission of tool use and tool manufacture in Goffin cockatoos (Cacatua goffini). Proc Biol Sci, 281 (2014), pp 1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hopper LM, Lambeth SP, Schapiro SJ, Whiten A. Observational learning in chimpanzees and children studied through ‘ghost’ conditions Proc Biol Sci, 7 (2008), pp. 835–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tennie C, Call J, Tomasello M. Evidence for emulation in chimpanzees in social settings using the floating peanut task PloS One 12 (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whiten A, van de Waal E Social learning, culture and the ‘socio-cultural brain’ of human and non-human primates Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 82 (2017), pp. 58–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montessori M The human tendencies and Montessori education American Montessori Society, 1966 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kozulin A Vygotsky in Context MIT Press; (1986) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kupán K, Király I, Kupán K, Krekó K, Miklósi Á, Topál J Interacting effect of two social factors on 18-month-old infants’ imitative behavior: Communicative cues and demonstrator presence J Exp Child Psychol,161 (2017), pp. 186–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simpson EA, Murray L, Paukner A, Ferrari PF The mirror neuron system as revealed through neonatal imitation: presence from birth, predictive power and evidence of plasticity Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 369 (2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paukner A, Suomi SJ, Visalberghi E, Ferrari PFPF. Capuchin monkeys display affiliation toward humans who imitate them Science 325 (2009), pp. 880–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chartrand TL and Bargh JA The chameleon effect: the perception-behavior link and social interaction J Pers Soc Psychol 76 (1999), pp. 893–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trezza V, Campolongo P, Vanderschuren LJ Evaluating the rewarding nature of social interactions in laboratory animals Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Noritake A, Ninomiya T, Isoda M Social reward monitoring and valuation in the macaque brain Nat Neurosci, 10 (2018), pp. 1452–1462 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Klein JT, Platt ML Social information signaling by neurons in primate striatum Curr Biol 23(2013), pp. 691–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dölen G, Darvishzadeh A, Huang KW, Malenka RC Social reward requires coordinated activity of nucleus accumbens oxytocin and serotonin nature 501 (2013), pp. 179–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hung LW, Neuner S, Polepalli JS, Beier KT, Wright M, Walsh JJ, Lewis EM, Luo L, Deisseroth K, Dölen G, Malenka RC. Gating of social reward by oxytocin in the ventral tegmental area Science 357 (2017), pp.1406–1411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosher CP, Zimmerman PE, Gothard KM Neurons in the monkey amygdala detect eye contact during naturalistic social interactions Curr Biol 24 (2014), pp. 2459–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomassello M Cultural transmission in the tool use and communicatory signaling of chimpanzees Parker ST & Gibson (1990), pp. 274–311

- 40.Isbaine F, Demolliens M, Belmalih A, Brovelli A, Boussaoud D Learning by observation in the macaque monkey under high experimental constraints Behav Brain Res, 289 (2015), pp. 141–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rizzolatti G,, Fadiga L, Gallese V, Fogassi L, Premotor cortex and the recognition of motor actions Cognitive Brain Research 3 (1996), pp. 131–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferrari PF, Gallese V, Rizzolatti G, Fogassi L Mirror neurons responding to the observation of ingestive and communicative mouth actions in the monkey ventral premotor cortex Eur J Neurosci, 17 (2003), pp. 1703–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferrari PF, Visalberghi E, Paukner A, Fogassi L, Ruggiero A, Suomi SJ. Neonatal imitation in rhesus macaques Plos Biol, 4 (2006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mukamel R, Ekstrom AD, Kaplan J, Iacoboni M, Fried I Single-neuron responses in humans during execution and observation of actions Curr Biol, 27 (2010), pp. 750–756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iacoboni M, Woods RP, Brass M, Bekkering H, Mazziotta JC, Rizzolatti G Cortical mechanisms of human imitation Science, 24 (1999), pp. 2526–2528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.LeDoux J The amygdala Curr Biol 17 (2007), pp. 868–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller CT, Freiwald WA, Leopold DA, Mitchell JF, Silva AC, Wang X Marmosets: A Neuroscientific Model of Human Social Behavior Neuron, 20 (2016), pp. 219–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mooney R Auditory-vocal mirroring in songbirds Philos. Trans, 369 (2014), pp. 1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Konichi M The role of auditory feedback in the control of vocalization in the white-crowned sparrow Z. Tierpsychol, 22 (1965) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.**.Vallentin D, Kosche G, Lipkind D, Long MA Neural circuits. Inhibition protects acquired song segments during vocal learning in zebra finches Science, 351 (2016), pp. 267–271The authors use two-photon microscopy guided intracellular recordings in HVC of awake, singing birds to show that structure inhibition contributes to song learning in zebra finches. The recordings were done in both juvenile birds that did not develop a mature song, and in adult birds that are capable of correctly singing.

- 51.Crowe SF, Hamalainen M.Comparability of a single-trial passive avoidance learning task in the young chick across different laboratories Neurobiol Lern Mem, 75 (2001), pp. 140–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dawson BV, Foss BM.Observational learning in budgerigars Anim Behav 13 (1965), pp. 470–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zentall TR Action Imitation in Birds Learn Behav, 32 (2004), pp. 15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guillette LM, Healy Social learning in nest building birds watching live-streaming video demonstrators Integr Zool, 13 (2018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.*.Jeon D, Kim S, Chetana M, Jo D, Ruley HE, Lin SY, Rabah D, Kinet JP, Shin HS. Observational fear learning involves affective pain system and Cav1.2 Ca2+ channels in ACC Nat Neurosci, 13 (2010), pp. 482–488This paper elegantly showed a role for the ACC in the observational learning of contextual fear conditioning in mice.

- 56.**.SA Allsop, Wichmann R, Mills F, Burgos-Robles A, Chang CJ, Felix-Ortiz AC, Vienne A, Beyeler A, Izadmehr EM, Glober G, Cum MI, Stergiadou J, Anandalingam KK, Farris K, Namburi P, Leppla CA, Weddington JC, Nieh EH, Smith AC, Ba D, Brown EN, Tye KM Corticoamygdala Transfer of Socially Derived Information Gates Observational Learning Cell, 173 (2018), pp. 1329– 1342The authors found that projections from the ACC to the BLA support observational learning of cue fear conditioning in mice. They used optical tagged recording in vivo to show that ACC neurons projecting to BLA preferentially represent the stimulus that has been conditioned by observation.

- 57.*.Rogers-Carter MM, Varela JA, Gribbons KB, Pierce AF, McGoey MT, Ritchey M, Christianson JP Insular cortex mediates approach and avoidance responses to social affective stimuli Nat Neurosci, 21 (2018), pp. 404–414The authors show that rats can detect and recognize the distress state of a conspecific. The insular cortex might play an important role in the detection and the behavioral response to the perceived stress.

- 58.**.Burkett JP, Andari E, Johnson ZV, Curry DC, de Waal FB, Young LJ Oxytocin-dependent consolation behavior in rodents Science, 22 92016), pp. 375–378The authors show that monogamous voles can detect and recognize the stressed state of the partner. In response, they begin to allogroom, an activity that decreases stress levels in the partner. If allogrooming is prevented, both partners exhibit high stress levels, indicating that the emotional state was socially transmitted. The behavioral response to the stress of the partner is mediated by oxytocin receptor neurons in ACC.

- 59.O’Keefe J A computational theory of the hippocampal cognitive map Prog Brain Res 83 (1990), pp. 301–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Doeller CF, Barry C, Burgess N Evidence for grid cells in a human memory network Nature 463 (2010), pp. 657–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.*.Teruko D, Taro T, Fujisawa S Spatial representations of self and other in the hippocampus Science 359 (2018), pp. 213–8The authors show the existence of social place cells in the rat CA1 hippocampal region. These cells respond to the position of another rat on a T-maze.

- 62.*.Omer DB, Maimon SR, Las L, Ulanovsky N Social place-cells in the bat hippocampus Science 359 (2018), pp. 218–24The manuscript demonstrates the existence of social place cells in the bat CA1 hippocampal region. These cells respond to the position of another bat during flight.

- 63.Chittka L, Leadbeater E Social learning: public information in insects Curr Biol 15 (2005), pp. 869–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fiorito G, Scotto P. Observational Learning in Octopus vulgaris Science, 24 (1992), pp. 545–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]