Abstract

Although numerous studies have established a link between IPV victimization and maternal mental health, extant research examining this association has not considered heterogeneity in the forms of IPV that women experience. This is an important gap given that typological perspectives suggest that mental health consequences of IPV victimization may depend on the particular pattern of IPV that is experienced. The current study used latent class analysis to: (1) identify and characterize distinct patterns of physical, psychological, and sexual IPV and male controlling behavior in a sample of pregnant South African women (n=1480) and (2) examine associations between IPV patterns and emotional distress during pregnancy (baseline) and nine months postpartum (follow-up). Latent class analysis identified a three-class solution wherein the largest class demonstrated a low probability of IPV victimization across all indicators (non-victims; 72% of the sample) and the smallest class demonstrated high probabilities of having experienced moderate and severe forms of IPV victimization as well as male controlling behavior (multiform severe controlling IPV; 4% of the sample). A third class (moderate IPV) was identified for which there was a high probability of experiencing moderate, but not severe, physical and psychological IPV (24% of the sample). Age, education, cohabitation status, experience of childhood abuse, and forced first sex were associated with class membership. Multiform severe controlling IPV victims reported significantly greater emotional distress than moderate IPV victims and non-victims at baseline and follow-up. The results contribute to understanding heterogeneity in the patterns of IPV that women experience that may reflect distinct etiological processes and warrant distinct prevention and treatment approaches.

Introduction

Poor mental health during pregnancy and postpartum (the perinatal period) is a prevalent global public health problem that disproportionately affects women in low- and lower middle-income countries (LLMIC). In a systematic review, Fischer et al. (2012) found that pregnant women and women who have recently given birth in LLMIC experience mental health conditions during pregnancy and post-partum at substantially higher rates than those reported in high-income countries (HIC). These perinatal mental health problems can result in devastating consequences for women and children in LLMIC including: adverse pregnancy outcomes; low birth weight; difficulties in the mother-infant relationship; and disturbances in child development (Fisher et al., 2012; Parsons, Young, Rochat, Kringlebach, & Stein, 2012; Rochat, Bland, Tomlinsen, & Stein, 2013; Stein et al., 2014). These adverse consequences may be more likely for women and children living in LLMIC than for those in HIC due to increased vulnerability stemming from socioeconomic disadvantage (Parsons et al., 2012; Stein et al., 2014).

One key risk factor that has been linked to maternal perinatal mental health problems, and thus represents a potentially important target for prevention efforts, is intimate partner violence (IPV) victimization. Women’s experiences of IPV prior to and/or during pregnancy may lead to overwhelming feelings of fear, anger, shame, and loss of control that, in turn, contribute to poor mental health during the transition to motherhood. Indeed, a growing body of research in HIC and, to a lesser extent, in LLMIC, has established a link between IPV victimization and a range of maternal mental disorders (for reviews, see Halim et al., 2017; Howard, Oram, Galley, Trevillion, & Feder, 2013).

While research clearly suggests a link between IPV and maternal mental health, a number of methodological problems with extant studies constrain interpretation and generalizability of findings (Devries et al., 2013; Howard et al., 2013; Halim et al., 2017). In particular, the majority of extant studies have been cross-sectional, precluding the ability to establish temporality. This is an important issue given that both theory and empirical research suggest the possibility for reverse causality (i.e., emotional distress may increase risk for experiencing IPV). Further, few studies have accounted for potential confounders, such as adverse childhood experiences, that predict both emotional distress and IPV victimization risk and may thus produce a spurious association between the two variables. Finally, most studies have narrowly assessed whether women have or have not experienced one particular form (e.g., physical) of IPV, thus failing to account for severity of violence and/or overlap across different forms of IPV. Studies that have assessed multiple forms of IPV (e.g., physical, sexual and/or psychological) typically either combine these measures into a composite scale that denotes whether the woman has or has not experienced any form of IPV (e.g., Fisher et al., 2013) or focus on identifying the unique effects of each form of IPV controlling for the others (e.g., Manongi et al., 2017). Yet, these approaches may fail to capture the particular configurations of IPV experiences that work synergistically to predict negative outcomes. In particular, typological theoretical perspectives on violence suggest that subgroups of women may experience unique patterns of IPV that have distinct consequences. For example, drawing from Johnson’s (1995) control-based typology of IPV, Johnson and Leone (2005) suggest that women who experience multiple forms of severe IPV embedded in a pattern of controlling behaviors, a type of IPV referred to as intimate terrorism, may be at greater risk for traumatic stress and related negative mental health outcomes than women who experience situational-couple violence, a pattern of IPV that is relatively less frequent and severe and is not rooted in a general pattern of controlling behaviors.

Indeed, consistent with typological perspectives on IPV, an emerging body of research conducted in HIC suggests that there is substantial heterogeneity in the patterns of IPV victimization that women experience and this heterogeneity may explain differential risk for negative outcomes (Ansara & Hindin, 2010; Carbone-Lopez, Kruttschnitt, & Macmillan, 2006; Cale, Tzoumakis, Leclerc, & Breckenridge, 2017; Dutton, Kaltman, Goodman, Weinfurt, & Vankos, 2005; Gupta et al., 2018; Sipsma et al., 2015). For example, in a sample of female university students in Australia and New Zealand, Cale et al. (2017) identified three salient patterns of IPV (labeled low, moderate, and high) that differed according to the variety, degree, and severity of IPV; depression symptoms were significantly higher for women in the high IPV class compared to women in the other IPV profiles. Little research, however, has been conducted to examine IPV victimization patterns and their consequences in LLMIC and, to our knowledge, no studies in HIC or LLMIC have examined patterns of IPV victimization among pregnant women and/or their relation to mental health outcomes during the perinatal period.

The Current Study

The primary aims of the current study were to: (1) identify and characterize prototypical patterns of IPV experienced by pregnant South African women and (2) determine whether and how IPV patterns are associated with emotional distress at baseline and follow-up. We used a person-centered analytic approach (Latent Class Analysis) to identify subgroups of women who are similar to each other within a group, but differ from members of other groups, in terms of their patterns of endorsement across an entire set of IPV indicators, which included measures of different forms (physical, psychological, and sexual) of IPV victimization as well as male controlling behavior.

Drawing from Johnson’s control-based typology of IPV, we expected to identify at least three latent classes with the following IPV patterns: a non-victim subgroup; a subgroup who report having experienced only moderate forms of IPV (M-IPV); and a subgroup who have experienced multiform severe controlling IPV (MSC-IPV), characterized by experiencing multiple forms of severe abuse and high levels of controlling behavior by their partner. Further, we posited that women in the MSC-IPV subgroup would report greater levels of emotional distress during pregnancy and postpartum compared to women in the M-IPV and non-victim subgroups.

Method

Design and procedure

Secondary analyses were conducted using extant data from a randomized controlled trial that examined the efficacy of enhanced HIV counseling for risk reduction during pregnancy and postpartum. Women seeking antenatal care from a health clinic in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa were recruited into the study. Eligible participants had to have had an intimate partner for at least six months and be unaware of their HIV status (never tested for HIV or tested negative at least 3 months prior to enrollment). Women who consented to participate completed a computer-assisted personal interview (CAPI) and were then randomized to receive either enhanced counseling (treatment group) or standard of care (control group) and tested for HIV and other STIs. All women in the study were provided with HIV counseling, with enhanced antenatal and postpartum counseling provided to those assigned to the treatment group. Follow-up interviews were conducted at nine months postpartum using the same interview procedures (CAPI). Women were reimbursed 70 South African Rand, equivalent to $8 USD at each assessment visit. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina and the University of KwaZulu-Natal. For additional details on recruitment, randomization, intervention, data collection, and supporting CONSORT checklist, see Maman et al. (2014).

Sample Characteristics

At baseline, 1480 women completed a baseline interview, were assigned to a treatment condition, and completed HIV-testing. On average, women were approximately 25 weeks pregnant at baseline and were 26 years old (range=18 to 45 years); 49% reported their highest education as grade 7 or lower; and over a third (39%) of women tested positive for HIV. Follow-up data were collected approximately nine-months postpartum from 75% (n=1104) of baseline participants.

Measures

Latent class (IPV) indicators.

Six indicators were created for use in defining the latent IPV classes: (1) moderate physical IPV, (2) severe physical IPV, (3) moderate psychological IPV, (4) severe psychological IPV, (5) sexual IPV, and (6) male controlling behavior. A modified version of the Violence Against Women Instrument (VAWI), which was developed by the World Health Organization, was used to measure IPV (Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2006). Women were asked how many times their current partner had perpetrated each of a series of psychological, physical, and sexual acts of IPV against them prior to or during pregnancy. Items assessing psychological and physical acts were further divided into indicators of “moderate” and “severe” psychological and physical IPV. In particular, two items assessed acts of moderate psychological IPV (insulted you or made you feel bad about yourself; belittled you or humiliated you in front of others) and two items assessed acts of severe psychological IPV (scared or intimidated you on purpose; threatened to hurt you or someone you care about). Similarly, two items assessed acts of moderate physical IPV (slapped or thrown something at you that could hurt; pushed or shoved you) and four items assessed acts of severe physical IPV (hit you with his fist or something else that could hurt; kicked you, dragged you, or beat you up; choked or burnt you on purpose; threatened to use or actually used a gun, knife or other weapon that could hurt you). Three items assessed sexual IPV (physically forced you to have sex when you did not want to; used threats to make you have sex; forced you to do something sexual you found degrading or humiliating). Response options ranged from “never” to “ten or more times.” Because item distributions were highly skewed and zero-inflated, scores on items for each form of IPV were summed and dichotomized to create binary indicators that denoted whether the woman had or had not experienced each form of IPV (e.g., 1=experienced at least one act of moderate physical IPV by current partner before or during pregnancy; 0=no experience of moderate physical IPV by current partner before or during pregnancy). Male controlling behavior was measured using 13 items from the relationship control subscale of the Sexual Relationship Power Scale (Pulerwitz, Amaro, De Jong, Gortmaker, & Rudd, 2002; α=.82), which assesses partner control over the respondent’s actions (e.g., what she can wear, who she spends time with). Response options ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Each item was dichotomously coded as “1” if the respondent strongly agreed that their partner engaged in the behavior and “0” otherwise. Scores across all items were then summed and dichotomized so that those whose scores fell into the upper quartile for the sample (>3) were coded as “1” to denote high male controlling behavior and “0” otherwise. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the indicators used to define the IPV classes (described below).

Table 1.

Baseline sample characteristics (n=1480)

| % or Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| IPV indicators | |

| Psychological victimization | |

| Moderate | 32.4 |

| Severe | 8.85 |

| Physical victimization | |

| Moderate | 27.1 |

| Severe | 13.5 |

| Sexual victimization | 7.4 |

| Male controlling behavior | 24.3 |

| Covariates | |

| Age (years) | 25.5 (5.36) |

| Education (ref=high school or more) | |

| Grade 7 or less | 6.6 |

| Grade 8–11 | 42.1 |

| Relationship length (years) | 4.47 (4.08) |

| Lives with current partner | 26.0 |

| Experienced childhood abuse | 5.0 |

| Experienced forced first sex | 16.4 |

Emotional distress.

Emotional distress was measured at baseline and follow-up using the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (HSCL-25; Hesbacher, Rickels, Morris, Newman, & Rosenfeld, 1980), which has been found to be a reliable and valid measure of mental health in studies in sub-Saharan Africa (Ashaba et al., 2018; Kaaya et al., 2002; Kagee, Saal, & Bantjes, 2017). The measure comprises 25 items assessing symptoms of emotional distress; respondents were asked how much discomfort each symptom (e.g., feeling lonely) had caused in the past week with response options ranging from “not distressed at all” (1) to “extremely distressed” (4). Scores were averaged across items to create a composite emotional distress score at baseline (α=.90) and follow-up (α=.93).

Covariates.

Descriptive statistics for covariates, which were assessed at baseline, are presented in Table 1. Age was coded as number of years. Education was coded as “0” for those who reported that the highest standard passed was 5 or less (grade 7 or lower); those who reported reaching standards 6–9 (grades 8–11) were coded as “1”; and those who reported matriculation from high school or higher were coded as “2”. Relationship length was coded as number of years in current relationship (M=4.47, SD=4.08). Lives with current partner was coded as “1” for those who reported currently living with their partner (regardless of marital status) and as “0” otherwise. Experience of childhood abuse was coded as “1” if the participant reported having had any “unwanted sexual experiences” (defined as inappropriate touching or unwanted sexual intercourse) or experienced any “serious physical violence” (defined as being hit, punched, kicked, or beaten up in a way that resulted in serious harm) prior to age 12 and as “0” otherwise; approximately 5% of women reported having experienced childhood abuse. Forced first sex was determined by asking participants “which of the following statements most closely describes your experience the very first time you had sex?” Six response options were listed: “I was willing”; “I was persuaded”; “I was tricked”; “I was physically forced by a partner”; “I was raped by a stranger”; “I was forced because of economic reasons.” Women whose experience did not fall into these categories gave open-ended responses. Women who reported (either via close-ended or open-ended response) that the first time they had sex they had been tricked, physically forced, raped by a stranger or family member, or forced due to economic reasons were coded as “1,” otherwise they were coded as “0.” Approximately 17% of women in the sample reported forced first sex.

Analytic Strategy

We conducted a series of latent class analyses (LCA) in Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2015) to identify respondents with similar patterns of responses on the six IPV indicators. We first identified the optimal number of classes for the sample by comparing models with increasing number of classes across different statistical fit indices including: the Akaike information criterion (AIC), the sample size adjusted Bayesian information criterion (ssBIC), and the Lo-Mendel-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test (LMR-LRT). The best-fitting most parsimonious models are those that minimize the AIC and ssBIC and for which adding an additional class results in a significant decrease in model fit as indicated by a p-value of less than .05 for the LMR LRT. We also evaluated classification quality, as indicated by entropy scores, and considered the substantive interpretation of the class profiles (Collins & Lanza, 2010). Full information maximum likelihood procedures were used to deal with missing data on the latent class indicators, which was minimal (maximum % missing on any one indicator was 1.69%; no women were missing data on all LCA indicators). A small number of cases (n=11, <1%) were missing data on covariates and were thus dropped from covariate adjusted analysis (described below).

After selecting the optimal unconditional latent class model, we reran the model including covariates as auxiliary variables in order to further characterize the classes by identifying whether and how covariates distinguished class membership. A three-step approach was used to model associations between covariates and class membership while accounting for measurement error due to uncertainty of class classification (for details see, Asporouhov & Muthén, 2014). In particular, relations between study covariates and latent class membership were examined within a multinomial logistic regression model in addition to the original measurement latent class model.

Finally, we examined associations between latent class membership and emotional distress at baseline (Model 1) and follow-up (Model 2) using the BCH method developed by Bakk and Vermunt (2016). The BCH method is measurement-error weighted and is the recommended approach for analyzing the effects of latent class membership on continuous distal outcomes because it avoids shifts in class membership and performs well even when the outcome is not normally distributed and/or has unequal variance across classes (Asporouhov & Muthén, 2015). To constrain type one error we first conducted an omnibus multiparameter Wald test to determine whether constraining the adjusted mean of emotional distress to be equal across classes, as compared to allowing the adjusted mean to vary across classes, produced a significant decrement in model fit. If the omnibus test was statistically significant, indicating class differences in emotional distress, we examined pairwise comparisons between classes on the outcome using Wald tests. Our hypothesis was that average distress would be higher in the MSC-IPV class, compared to the other classes; thus, the pairwise comparisons involving the MSC-IPV class were of a priori interest. Covariates were included in both models to adjust for potential confounding. The model assessing effects on postpartum emotional distress was further adjusted for baseline distress, treatment group, and HIV status.

Results

Identification and Characterization of Latent Classes of IPV Victimization

A series of latent class models with one to five classes were estimated and compared. The AIC was lowest for the four-class solution; however, both the BIC and the LMR-LRT suggested that the three-class model provided the best fit to the data (see Table 2). Further, the three-class model provided a clearly interpretable solution with good classification accuracy. We thus selected the three-class solution based on a combination of model fit, parsimony, and interpretability.

Table 2.

Fit Indices for Unconditional Latent Class Analysis of IPV Victimization Indicators

| Unconditional Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 class | 2 classes | 3 classes | 4 classes | 5 classes | |

| AIC | 8041.95 | 7212.04 | 7181.61 | 7176.67 | 7177.23 |

| ssBIC | 8054.69 | 7239.64 | 7224.07 | 7233.99 | 7249.42 |

| LMR p-value | NA | <.001 | .009 | .22 | .19 |

| Entropy | NA | .80 | .76 | .65 | .64 |

Note. AIC=Akaike information criteria; ssBIC=sample size adjusted Bayesian information criteria; LMR=Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test

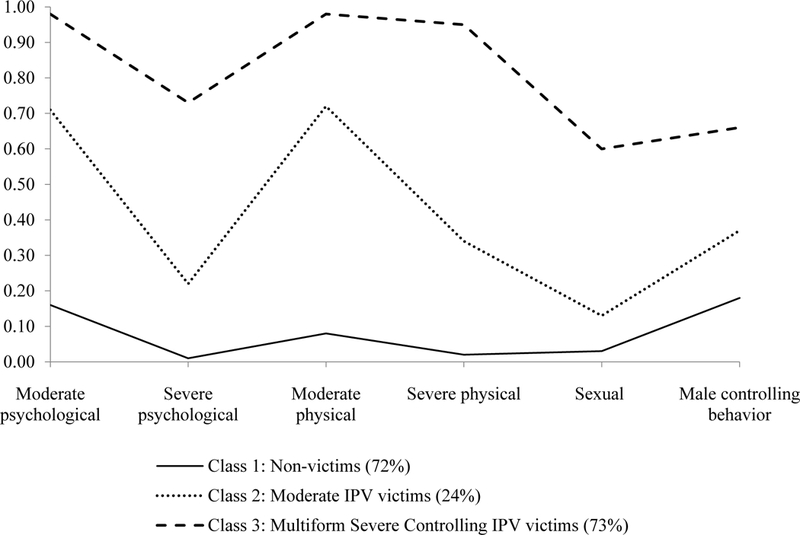

The parameter estimates for the 3-class model are shown in Table 3 and graphically depicted in Figure 1. Patterns for the three classes were consistent with study expectations. In particular, the first class was labeled non-victims (NV; prevalence=72%) because members had low probabilities of endorsing any of the IPV indicators. The second class was labeled moderate IPV (M-IPV; prevalence=24%) because members had high probabilities (>.50) of endorsing moderate psychological and physical violence and low probabilities of endorsing any other IPV indicator. The third class was labeled multiform severe controlling IPV (MSC-IPV; prevalence=4%), based on high probabilities of endorsing all of the IPV indicators, including male controlling behavior.

Table 3.

Parameter Estimates for Model of Three IPV Victimization Latent Classes

| Non-victims | Moderate IPV |

Multiform Severe Controlling IPV |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Latent Class Membership Probabilities | .72 | .24 | .04 |

| IPV Indicator | Item Response Probabilities | ||

| Psychological victimization | |||

| Moderate | .16 | 0.71 | 0.98 |

| Severe | .01 | 0.22 | 0.73 |

| Physical victimization | |||

| Moderate | .09 | 0.72 | 0.99 |

| Severe | .02 | 0.34 | 0.95 |

| Sexual victimization | .03 | 0.13 | 0.60 |

| Male controlling behavior | .18 | 0.37 | 0.66 |

Note. Item response probabilities greater than .50 bolded to facilitate interpretation.

Figure 1.

Latent class prevalences and item-response probabilities for the three-class model

Associations between Covariates and IPV Class Membership

Table 4 presents the findings of adjusted multinomial models examining associations between covariates and each of the IPV classes.

Table 4.

Effects of Risk Covariates on IPV Latent Class Membership

| IPV Class | Effect | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-victims as comparison class | |||

|

Multiform

Severe Controlling IPV |

Age | 0.90 (0.83, 0.97)** | |

| Education | 1.47 (0.60, 3.56) | ||

| Relationship length | 1.08 (0.99, 1.18) | ||

| Lives with current partner | 3.90 (1.35, 11.32)* | ||

| Childhood abuse | 3.39 (1.29, 9.02)* | ||

| Forced first sex | 3.85 (1.84, 8.08)*** | ||

|

Moderate IPV |

Age | 0.91 (0.87, 0.95)*** | |

| Education | 0.54 (0.39, 0.73)*** | ||

| Relationship length | 1.05 (1.00, 1.11)^ | ||

| Lives with current partner | 1.60 (0.98, 2.62)^ | ||

| Childhood abuse | 1.13 (0.50, 2.56) | ||

| Forced first sex | 1.15 (0.68, 1.96) | ||

| Moderate IPV as Comparison Class | |||

|

Multiform Severe Controlling IPV |

Age | 0.99 (0.90, 1.08) | |

| Education | 2.72 (0.99, 7.54)^ | ||

| Relationship length | 1.03 (0.92, 1.15) | ||

| Lives with current partner | 2.43 (0.66, 8.94) | ||

| Childhood abuse | 3.01 (0.84, 10.79)^ | ||

| Forced first sex | 3.35 (1.26, 8.87)* | ||

Note. AOR=Adjusted odds ratio. Parameter estimates are from a three-step LCA model that adjusted for classification error.

p<.10,

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Distinguishing the multiform severe controlling IPV victims from non-victims class

Older age was associated with decreased odds of being in the MSC-IPV compared to the NV class (AOR=.90, p=.005). Women who reported living with their current partner had nearly four times the odds of belonging to the MSC-IPV compared to the NV class (AOR=3.90, p=.01). In addition, both having experienced childhood abuse (AOR=3.39, p=.01) and forced first sex (AOR=3.85, p<.001) were each associated with over three times higher adjusted odds of being in the MSC-IPV victims class compared to the NV class.

Distinguishing the moderate IPV victims from non-victims class

Older age (AOR=0.91, p<.001) and higher levels of education (AOR=0.54, p<.001) were each associated with significantly decreased odds of being in the M-IPV versus the NV class. None of the other covariates, however, distinguished the M-IPV from the NV class.

Distinguishing the multiform severe controlling victims from the moderate IPV victims class

The only risk covariate that distinguished women in the MSC-IPV from the M-IPV class was forced first sex. In particular, women who reported having experienced forced first sex had over three times higher adjusted odds of being in the MSC-IPV versus the M-IPV class (AOR=3.35, p=.02).

Associations between Class Membership and Emotional Distress

Table 5 presents findings from analyses of the effects of IPV latent class membership on emotional distress during pregnancy (baseline) and at nine-months postpartum (follow-up). Consistent with expectations, at baseline, women in the MSC-IPV subgroup reported significantly higher levels of emotional distress than those in both the M-IPV (p<.001) and NV (p<.001) subgroups. Those in the M-IPV subgroup also reported significantly higher levels of baseline emotional distress than those in the NV subgroup (p<.001).

Table 5.

Adjusted mean emotional distress at baseline (pregnancy) and postpartum follow-up by IPV class membership

| Latent Class | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | Omnibus Wald 2 |

Post-hoc comparisons | |

| Outcome | Multiform Severe Controlling IPV |

Moderate IPV |

Non- victims |

||

| Baseline emotional distress | 2.25 (.12) | 1.82 (.05) | 1.52 (.04) | 89.91*** | 1>2**, 1>3***, 2>3*** |

| Postpartum emotional distress | 1.37 (.18) | 0.94 (.09) | 0.85 (.07) | 14.67*** | 1>2*, 1>3** |

Note. Standard errors appear in parentheses. Covariates included in models for baseline and follow-up emotional distress were age, education, relationship length, cohabitation status, childhood abuse, and forced first sex. The model for follow-up emotional distress further included baseline emotional distress, HIV-status, and treatment condition. All analyses were measurement-error weighted using the BCH method. The omnibus Wald test assessed the null hypothesis that the latent class means were equal across groups. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons between classes significant at p<.05 are shown in the last column of the table.

IPV class membership also longitudinally predicted postpartum emotional distress. As expected, those in the MSC-IPV subgroup reported significantly greater postpartum emotional distress than those in the M-IPV (adjusted p=.01) and NV (adjusted p=.001) subgroups. Levels of postpartum emotional distress did not differ significantly between the M-IPV and NV classes (p=.15). Notably, all significant findings for pair-wise comparisons remained significant when applying the False Discovery Rate (FDR) for multiple comparisons (Thissen, Steinberg, & Kuang, 2002).

Discussion

The present study demonstrates how adopting a person-centered approach to assessing IPV offers a powerful and more nuanced assessment of the nature of the association between IPV and maternal mental health. We identified three subgroups of pregnant women characterized by distinct patterns of IPV victimization in their current relationship: non-victims, moderate IPV victims (M-IPV), and multiform severe controlling IPV victims (MSC-IPV). The MSC-IPV subgroup was distinguished from the M-IPV subgroup in terms of high probabilities of endorsing severe forms of IPV victimization as well as male controlling behavior. Consistent with expectations, IPV profile membership was differentially associated with levels of emotional distress; women in the MSC-IPV subgroup reported higher levels of emotional distress during pregnancy and postpartum compared to women in the other subgroups.

That we were able to detect distinct substantively interpretable patterns of IPV is consistent with research that has found heterogeneous patterns of IPV victimization experiences in samples of non-pregnant women in HIC (e.g. Cale et al., 2017) and LLMIC (Gupta et al., 2018; Sipsma et al., 2015). Further, the two IPV profiles that emerged (MSC- and M-IPV), which were distinguished along dimensions of severity and experience of male controlling behavior, are consistent with Johnson’s (1995) control-based typology of IPV. In particular, Johnson’s (1995) typology suggests there may be a small subgroup of IPV victims who experience intimate terrorism, a pattern of violence characterized by male partners’ use of severe forms of IPV embedded in a dynamic of coercive control, and a larger subgroup of victims who experience situational couple violence which is characterized by being situationally provoked and “more likely than intimate terrorism to involve only isolated low-level violence” (Johnson & Leone, 2005, p. 326). These two types of violence perpetration are thought to be driven by different etiological factors and thus potentially merit different prevention and treatment approaches. In particular, intimate terrorism is posited to be rooted in an attempt to exert control that is driven by patriarchal traditions of male dominance, whereas situational couple violence is posited to arise from everyday stressors that produce relationship conflict (Johnson, 1995). While more research is needed, services to prevent revictimization among pregnant women who are IPV victims may need to be tailored to address the particular pattern of IPV that she is experiencing. For example, scholars have noted that approaches such as couples counseling to increase conflict management skills that may be appropriate for women who are experiencing situational couple violence, may be inappropriate or even harmful for women experiencing intimate terrorism (Johnson & Leone, 2005).

Consistent with study hypotheses, women in the MSC-IPV subgroup reported greater emotional distress during pregnancy and postpartum than those in the M-IPV and NV subgroups. These findings align with previous research in high income settings that suggests that women who experience severe IPV that is embedded in a pattern of control experience worse mental health outcomes than women who experience other IPV patterns (Ansara & Hindin, 2010; Dutton et al., 2005; Temple, Weston, & Marshall, 2010). The accumulation of multiple traumas in the context of coercive control may lead to increased likelihood of developing posttraumatic stress symptomatology and adoption of maladaptive coping strategies that increase emotional distress (Dutton et al., 2005); the pathway from multiform severe controlling IPV to emotional distress may be particularly salient during the transition to motherhood when demands and changes may already be producing high levels of stress that tax the coping resources of expectant mothers. We note that those in the M-IPV subgroup also reported higher levels of distress than non-victims during pregnancy, but these differences became non-significant at postpartum; it may be that moderate IPV produces immediate effects on emotional distress that diminish over time.

Although not a central purpose of the paper we found that a number of different covariates distinguished women in the MSC-IPV class from women in the other classes. In particular, women who reported living with their current partner and younger women were at increased risk of being in the MSC-IPV victims class compared to the non-victims class. The finding that age was associated with risk for MSC-IPV is consistent with research in the US and other countries that has found that younger age is associated with increased risk of experiencing coercive control, perhaps because the need to exert sexual control is more salient for men with younger as compared to older female partners (Policastro & Finn, 2017; Aizpura, Copp, Ricarte, & Vazquez, 2017).

Notably, findings further suggest that having experienced childhood abuse and having experienced forced sex distinguished women experiencing MSC-IPV from women in the other classes. This finding is consistent with empirical research and theoretical models of coercive control that suggest that women with pre-existing psychological vulnerabilities (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder, insecure attachment style) that result from earlier experiences of victimization may be particularly at risk for experiencing severe controlling patterns of IPV (Dutton & Goodman, 2005; Widom, Czaja, & Dutton, 2014). The prevention implications of these findings are twofold. First, preventing victimization early in the life-course among girls may be an effective primary prevention approach for reducing women’s risk of experiencing MSC-IPV in adulthood. Second, girls and women who experience early victimization should be identified and provided trauma-informed services in order to interrupt continuity of victimization.

Our research has limitations to consider in interpreting results and future research. First, all data were self-report and thus subject to social desirability and single-reporter bias. Second, women were eligible for the study only if they had been in a relationship with their current partner for at least six months; more research is needed to determine whether the patterns identified generalize to short-term relationships. Third, IPV perpetration and victimization are often linked, and ideally our analysis would examine both; perpetration, however, was not assessed, thus our analysis is limited to victimization patterns. Fourth, our measures of IPV risk factors were limited in scope and comprehensiveness. Further, our choice to code women as having experienced male controlling behavior if they were in the top quartile on this measure may have resulted in misclassification bias. Fifth, we only assessed one broad mental health outcome, emotional distress; future research should replicate and build on our findings to examine associations between IPV profile membership and other predictors and health outcomes. Finally, some research suggests that the mental health impacts of IPV may be exacerbated for women who concurrently experience other mental health stressors, such as a positive HIV-diagnosis (Illangasekare, Burke, Chandler, & Gielen, 2013); future research should thus examine whether and how the relationship between IPV profile membership and mental health varies depending on the presence of other stressors as well as resiliency factors (e.g., social support).

Notwithstanding these limitations, the current study had several notable strengths. The study focused on pregnant women in South Africa, a relatively understudied population at high risk for IPV and its adverse consequences. We assessed multiple forms of moderate and severe IPV as well as male partner controlling behavior, thus enabling a more comprehensive assessment of patterns of IPV than has been undertaken in prior research. Analyses of associations between latent class membership and covariates and distress outcomes were adjusted for measurement error. Further, we established temporality of associations and adjusted for confounding in our assessment of relations between IPV patterns and emotional distress.

Conclusion

The present study is the first to identify and characterize heterogeneous patterns of IPV victimization among pregnant women and examine associations between these patterns and emotional distress during the perinatal period. A latent class analysis provided support for three distinct classes of IPV victimization representing non-victims, moderate physical and psychological IPV, and multiform severe controlling IPV. Women who experienced multiform severe controlling IPV reported greater emotional distress than women in the other classes at both pregnancy and postpartum, suggesting this pattern of victimization has particularly deleterious effects on mental health during the perinatal period. Screening protocols for pregnant women may need to be refined to identify women experiencing different patterns of IPV so as to provide them with appropriately tailored trauma-informed care. Childhood abuse and forced first sex were associated with increased risk of multiform severe controlling IPV, underscoring the importance of prevention programs to disrupt the cycle of violence early in the life-course. Etiological research is needed that builds on the current study to replicate findings and further explain heterogeneity in the causes, experiences of, and consequences of IPV victimization among pregnant and non-pregnant women and girls. In addition, prevention research is needed to determine whether and how IPV prevention and treatment strategies during the perinatal period should be tailored for women experiencing different patterns of IPV.

Acknowledgments

Grant Funding. This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Development (Grant # 1-R03-HD089140–01) to the corresponding author.

References

- Aizpura E, Copp J, Ricarte JJ, & Vazquez D Controlling behaviors and intimate partner violence among women in Spain: An examination of individual, partner, and relationship risk factors for physical and psychological abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Advanced online publication. 10.1177/0886260517723744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashaba S, Kakuhikire B, Vorechovska D, Perkins JM, Cooper-Vince CE, Maling S,…Tsai AC 2018. Reliability, validity, and factor structure of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25: Population-based study of persons living with HIV in rural Uganda. AIDS and Behavior, 22(5), 1467–1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansara DL, & Hindin MJ (2010). Exploring gender differences in the patterns of intimate partner violence in Canada: a latent class approach. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 64(10), 849–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, & Muthén B (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(3), 329–341. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, & Muthén B (2015). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Using the BCH method in Mplus to estimate a distal outcome model and an arbitrary second model. Mplus Web Notes, 21(2), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bakk Z, & Vermunt JK (2016). Robustness of stepwise latent class modeling with continuous distal outcomes. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 23(1), 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cale J, Tzoumakis S, Leclerc B, & Breckenridge J (2016). Patterns of Intimate Partner Violence victimization among Australia and New Zealand female university students: An initial examination of child maltreatment and self-reported depressive symptoms across profiles. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 50, 582–601. [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, & Lanza ST (2010). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Devries KM, Mak JY, Bacchus LJ, Child JC, Falder G, Petzold M, ... & Watts CH (2013). Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Med, 10(5), e1001439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA & Goodman LA (2005). Coercion in intimate partner violence: Toward a new conceptualization. Sex Roles, 52(11–12), 743–756. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA, Kaltman S, Goodman LA, Weinfurt K, & Vankos N (2005). Patterns of intimate partner violence: Correlates and outcomes. Violence and Victims, 20(5), 483–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J, Mello MCD, Patel V, Rahman A, Tran T, Holton S, & Holmes W (2012). Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low-and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 90(2), 139–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J, Tran TD, Biggs B, Dang TH, Nguyen TT, & Tran T (2013). Intimate partner violence and perinatal common mental disorders among women in rural Vietnam. International Health, 5, 29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Watts CH (2006). Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet, 368(9543), 1260–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta J, Willie TC, Harriss C, Campos PA, Falb KL, Moreno CG,…Okechukwu CA (2018). Intimate partner violence against low-income women in Mexico City and associations with work-related disruptions: a latent class analysis using cross-sectional data. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1136/jech-2017-209681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halim N, Beard J, Mesic A, Patel A, Henderson D, & Hibberd P (2017). Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and perinatal mental disorders in low and lower middle income countries: A systematic review of the literature 1990–2017. Clinical Psychology Review. Advance online publication. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesbacher PT, Rickels K, Morris RJ, Newman H, & Rosenfeld H (1980). Psychiatric illness in family practice. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 41, 6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard LM, Oram S, Galley H, Trevillion K, & Feder G (2013). Domestic violence and perinatal mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med, 10(5), e1001452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illangasekare S, Burke J, Chander G, & Gielen A (2013). The syndemic effects of intimate partner violence, HIV/AIDS, and substance abuse on depression among low-income urban women. Journal of Urban Health, 90(5), 934–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP (1995). Patriarchal terrorism and common couple violence: Two forms of violence against women. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 57(2) 283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, & Leone JM (2005). The differential effects of intimate terrorism and situational couple violence findings from the national violence against women survey. Journal of Family Issues, 26(3), 322–349. [Google Scholar]

- Kaaya SF, Fawzi MC, Mbwambo JK, Lee B, Msamanga GI, & Fawzi W (2002). Validity of the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist-25 amongst HIV-positive pregnancy women in Tanzania. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 106(1), 9–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagee A, Saal W, & Bantjes J (2018). Distress, depression, and anxiety among persons seeking HIV testing. AIDS Care, 29(3), 280–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouyoumdjian FG, Calzavara LM, Bondy SJ, O’Campo P, Serwadda D, Nalugoda F, ... & Gray R (2013). Risk factors for intimate partner violence in women in the Rakai Community Cohort Study, Uganda, from 2000 to 2009. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 566–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahenge B, Likindikoki S, Stockl H, & Mbwambo J (2013). Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and associated mental health symptoms among pregnant women in Tanzania: A cross-sectional study. BJOG, 120, 940–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, Moodley D, McNaughton-Reyes HL, Groves AK, Kagee A, & Moodley P (2014). Efficacy of enhanced HIV counseling for risk reduction during pregnancy and in the postpartum period: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One, 9(5), e97092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, & Muthén B (2015). Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons CE, Young KS, Rochat TJ, Kringelbach M, & Stein A (2012). Postnatal depression and its effects on child development: a review of evidence from low-and middle-income countries. British Medical Bulletin, 101, 57–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Policastro C & Finn MA (2017). Coercive control in intimate relationships: Differences across age and sex. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Advanced online publication. 10.1177/0886260517743548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Amaro H, Jong WD, Gortmaker SL, & Rudd R (2002). Relationship power, condom use and HIV risk among women in the USA. AIDS Care, 14(6), 789–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochat T, Bland R, Tomlinson M and Stein A (2013). Suicide ideation, depression and HIV among pregnant women in rural South Africa. Health, 5, 650–661. [Google Scholar]

- Sipsma HL, Falb KL, Willie T, Bradley EH, Bienkowski L, Meerdink N, & Gupta J (2015). Violence against Congolese refugee women in Rwanda and mental health: a cross-sectional data using latent class analysis. BMJ Open, 5, e006299. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein A, Pearson RM, Goodman SH, Rapa E, Rahman A, McCallum M, … & Pariante CM. (2014). Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. The Lancet, 384, 1800–1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartout KM, Cook SL, & White JW (2012). Trajectories of intimate partner violence victimization. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13(3), 272–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple JR, Weston R, & Marshall LL (2010). Long-term mental health effects of partner violence patterns and relationship termination on low-income and ethnically diverse community women. Partner Abuse, 1(4), 379–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D, Steinberg L, & Kuang D (2002). Quick and easy implementation of the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for controlling the false positive rate in multiple comparisons. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 27, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK (2010). Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Political Analysis, 18(4), 450–469. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Czaja S, & Dutton MA (2014). Child abuse and neglect and intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration: A prospective investigation. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(4), 650–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]